전기차

Electric car| 시리즈의 일부(on) |

| 지속가능에너지 |

|---|

|

전기 자동차 또는 전기 자동차(electric vehicle, EV)는 하나 이상의 전기 트랙션 모터에 의해 구동되는 승용차이다, 단지 온보드 배터리에 저장된 에너지만을 사용합니다.전기차는 기존 내연기관(ICE) 차량에 비해 소음이 적고, 반응성이 높으며, 에너지 변환 효율이 우수하며, 배기가스 배출이 없으며, 전체 차량[1] 배출이 적습니다(다만 전기를 공급하는 발전소에서 자체 배출이 발생할 수 있음)."전기 자동차"는 일반적으로 배터리 전기 자동차(BEV)를 지칭하지만, 넓은 범위에서 플러그-인 하이브리드 전기 자동차(PHEV), 범위-확장 전기 자동차(REEV) 및 연료 전지 전기 자동차(FCEV)를 포함할 수도 있습니다.

일반적으로 전기차 배터리는 충전을 위해 주전원 전원 공급 장치에 전원을 연결해야 순항 범위를 최대화할 수 있습니다.전기 자동차를 충전하는 것은 다양한 충전소에서 할 수 있습니다. 이러한 충전소는 개인 주택, 주차장 및 공공 [2]장소에 설치할 수 있습니다.배터리 교환 및 유도 충전과 같은 다른 기술에 대한 연구 개발도 있습니다.충전 인프라(특히 급속 충전기를 사용하는 인프라)가 아직 상대적으로 초기 단계이기 때문에 소비자의 구매 결정 시 범위 불안과 시간 비용이 전기차에 대한 빈번한 심리적 장애 요인이 됩니다.

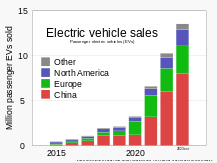

전 세계적으로 2022년 플러그인 전기차는 1000만대가 판매돼 [3]신차 판매의 14%를 차지했습니다.2021년의 9%보다 증가했습니다.많은 국가들이 플러그인 전기 자동차, 세액 공제, 보조금 및 기타 비금전적 인센티브에 대한 정부 인센티브를 제정했으며, 여러 국가들은 대기 오염을 줄이고 기후 [6][7]변화를 제한하기 위해 화석 연료 [4][5]자동차의 판매를 단계적으로 중단하는 법안을 제정했습니다.국제에너지기구(IEA)[8]에 따르면 2023년에는 EV가 전 세계 자동차 판매의 거의 5분의 1을 차지할 것으로 예상됩니다.

중국은 현재 2020년 [9]12월까지 누적 판매량 550만대로 세계에서 가장 많은 전기차 재고를 보유하고 있지만, 이 수치에는 버스, 쓰레기 트럭, 위생 차량 등 중과 상용차도 포함되며 중국에서 [10][11][12][13][14][15]생산된 차량만 포함됩니다.미국과 유럽연합은 2020년 현재 연료비와 유지비가 [16][17]낮아져 최근 전기차의 총소유비용이 동급 ICE차에 비해 저렴합니다.

2023년 테슬라 모델 Y는 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 [18]차가 되었습니다.테슬라 모델3는 2020년 [19]초에 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 전기차가 되었고, 2021년 6월에는 전기차 최초로 [20]세계 판매량 100만대를 돌파했습니다.전기 자동차는 자율 주행, 커넥티드 차량 및 공유 모빌리티와 같은 새로운 자동차 기술과 함께 자율, 커넥티드, 전기 및 공유([21]ACES) 모빌리티라는 미래 모빌리티 비전을 형성합니다.

용어.

"전기자동차"란 일반적으로 배터리 전기 자동차(BEV) 또는 전지 전기 자동차를 의미하며, 전기 그리드에서 플러그를 꽂고 충전할 수 있는 온보드 충전식 배터리 팩을 구비하는 전기 자동차(EV)의 일종,그리고 차량에 저장된 전기는 바퀴에 추진력을 제공하는 유일한 에너지원입니다.이 용어는 일반적으로 고속도로가 가능한 자동차를 가리키지만, 공공도로를 주행할 수 있는 무게, 동력, 최고속도 등의 측면에서 한계가 있는 저속 전기자동차도 있습니다.후자는 [22]미국에서는 NEV(Neighborhood Electric Vehicle)로, [23]유럽에서는 전기 모터 구동 4륜차로 분류됩니다.

역사

초기개발

Robert Anderson은 1832년에서 [24]1839년 사이에 최초의 전기 자동차를 발명한 것으로 종종 인정받고 있습니다.

1880년대에는 다음과 같은 실험용 전기 자동차가 등장했습니다.

- 1881년 [25]구스타브 트루베는 개선된 지멘스 모터로 구동되는 전기 자동차를 파리 국제 전기 박람회에서 선보였습니다.

- 1884년, 포드 모델 T가 나오기 20년 이상 전에 토마스 파커는 울버햄튼에서 [26][27][28]1895년에 찍은 사진이 유일한 문서임에도 불구하고 특별히 설계된 고용량 충전식 배터리를 사용하여 전기 자동차를 만들었습니다.

- 1888년 독일의 안드레아스 플로켄(Andreas Flocken)은 일부 사람들에 의해 "진짜" 전기 자동차로 [29][30][31]간주되는 플로켄 일렉트로겐(Flocken Electroagen)을 디자인했습니다.

전기는 19세기 후반과 20세기 초반에 자동차 추진에 선호된 방법 중 하나였으며,[32] 당시의 휘발유로 구동되는 자동차로는 달성할 수 없었던 수준의 편안함과 조작의 용이성을 제공했습니다.전기차는 20세기 [33]초에 약 3만 대로 정점을 찍었습니다.

1897년, 전기 자동차는 영국과 미국에서 처음으로 택시로서의 상업적 용도를 발견했습니다.런던에서, Walter Bersey의 전기 택시는 택시가 말을 끄는 [34]시기에 처음으로 사용되는 자주식 차량이었습니다.뉴욕시에서는 일렉트로배트 II의 설계를 바탕으로 12대의 핸섬 택시와 1대의 브로엄으로 이루어진 함대가 필라델피아의 전기 [35]저장 배터리 회사에 의해 부분적으로 자금을 지원받는 프로젝트의 일부를 구성했습니다.20세기 동안, 미국의 주요 전기 자동차 제조업체는 앤서니 일렉트릭, 베이커, 컬럼비아, 앤더슨, 에디슨, 라이커, 밀번, 베일리 일렉트릭, 디트로이트 일렉트릭 등을 포함했습니다.그들의 전기차는 가솔린 차보다 더 조용했고,[36][37] 기어를 바꿀 필요도 없었습니다.

19세기에는 [38]여섯 대의 전기 자동차가 육상 속도 기록을 보유하고 있었습니다.그 중 마지막은 카밀 제나치(Camille Jenatzy)가 운전하는 로켓 모양의 라 자미스 콘테(La Jamais Contente)였는데, 1899년 최고 속도가 시속 105.88km(65.79mph)에 도달하여 시속 100km(62mph)의 속도 장벽을 깼습니다.

내연기관 자동차의 발전과 더 저렴한 가솔린 및 디젤 차량의 대량 생산이 감소하기 전까지 전기 자동차는 여전히 인기가 있었습니다.ICE 자동차는 연료 주입 시간이 훨씬 빠르고 생산 비용이 저렴하기 때문에 더욱 인기가 있습니다.그러나 1912년 전기 스타터[39] 모터가 도입되면서 결정적인 계기가 마련되었는데, 이 모터는 손으로 하는 크랭킹과 같이 종종 힘든 다른 시동 방법을 대체하기도 했습니다.

-

Tesla Roadster는 현대 세대의 전기 자동차에 영감을 주는 것을 도왔습니다.

현대의 전기자동차

1990년대 초, 캘리포니아 항공 자원 위원회(CARB)는 전기 [42][43]자동차와 같은 제로 배기 가스 차량으로의 이동을 궁극적인 목표로 하여 보다 연료 효율적이고 낮은 배기 가스 차량에 대한 추진을 시작했습니다.이에 부응하여 자동차 회사들은 전기 모델을 개발했습니다.이 초기의 자동차들은 [44]결국 미국 시장에서 철수되었는데, 이는 미국 자동차 회사들이 전기 자동차에 대한 신뢰를 떨어뜨리려는 대대적인 캠페인 때문이었습니다.

캘리포니아 전기 자동차 제조업체인 Tesla Motors는 2008년에 처음으로 고객에게 공급된 Tesla Roadster의 개발을 2004년에 시작했습니다.로드스터는 리튬 이온 배터리 셀을 사용한 최초의 고속도로 합법 전기 자동차이며, 최초의 생산용 전기 자동차로 충전 [45]시 320km(200마일) 이상 주행했습니다.

캘리포니아주 팔로알토에 본사를 두고 있지만 이스라엘에서 운영하는 벤처 지원 회사인 Better Place는 전기 자동차의 배터리 충전 및 배터리 교환 서비스를 개발 및 판매했습니다.이 회사는 2007년 10월 29일에 공식 출범했으며 2008년과 2009년에 이스라엘, 덴마크, 하와이에 전기차 네트워크를 배치했다고 발표했습니다.회사는 국가별로 인프라를 구축할 계획이었습니다.2008년 1월, Better Place는 Renault-Nissan과 이스라엘을 위한 세계 최초의 EGR(Electric Recharge Grid Operator) 모델 구축을 위한 양해각서를 발표했습니다.협약에 따라, Better Place는 전기 충전망을 구축하고 르노-닛산은 전기 자동차를 제공할 것입니다.Better Place는 2013년 5월 이스라엘에 파산을 신청했습니다.회사의 재정적 어려움은 잘못된 경영, 너무 많은 국가에서 조종사를 설립하고 운영하려는 낭비적인 노력, 충전 및 교환 인프라 개발에 필요한 높은 투자, 그리고 당초 [46]예측했던 것보다 훨씬 낮은 시장 보급률로 인해 발생했습니다.

2009년 일본에서 출시된 미쓰비시 i-MiEV는 고속도로에서 합법적으로 생산되는 전기차 [47]최초이자, 10,000대 이상을 판매한 최초의 전기차였습니다.몇 달 후인 2010년에 출시된 닛산 리프는 i MiEV를 제치고 당시 [48]가장 많이 팔린 전기차가 되었습니다.

2008년을 기점으로 배터리의 발전과 온실가스 감축 및 도시 대기질 [49]개선에 따른 전기차 제조업의 르네상스가 이루어졌습니다.2010년대 중국의 전기차 산업은 정부의 [50]지원으로 크게 성장했습니다.다만 중국 정부가 도입하는 보조금은 20~30% 인하하고 2023년 이전에 단계적으로 완전히 폐지하기로 했습니다.테슬라, 폴크스바겐, 광저우에 본사를 둔 GAC 그룹은 [51]피아트, 혼다, 이스즈, 미쓰비시, 도요타 등 여러 자동차 회사들이 보조금 조정을 예상하고 전기차 가격을 인상했습니다.

2019년 7월, 미국의 모터트렌드지는 테슬라 모델 S에 "올해의 [52]궁극의 자동차"라는 칭호를 수여했습니다.2020년 3월, 테슬라 모델 3는 닛산 리프를 통과하여 50만 대 이상의 [19]판매고를 올리며 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 전기차가 되었고, 2021년 [20]6월에는 전 세계에서 100만 대의 판매고를 달성했습니다.

2021년 3분기 자동차 혁신 연합(Alliance for Automotive Innovation)은 전기차 판매량이 미국 전체 경차 판매량의 6%를 기록했으며, 이는 187,000대로 사상 최대치를 기록했다고 발표했습니다.이는 휘발유와 경유차 판매가 1.3% 증가한 것에 비해 11% 증가한 것입니다.보고서에 따르면 캘리포니아가 미국 구매의 40%에 육박하는 전기차 부문에서 미국 선두를 차지했으며 플로리다 – 6%, 텍사스 – 5%, 뉴욕 4.[55]4% 순으로 나타났습니다.

중동의 전기 회사들은 전기 자동차를 디자인해왔습니다.오만의 메이스 모터스는 2023년에 생산을 시작할 것으로 예상되는 메이스 E1을 개발했습니다.탄소 섬유로 제작된 이 엔진은 약 560km(350마일)의 범위를 가지며 0~130km/h(0~80mph)에서 약 4초 [56]만에 가속할 수 있습니다.터키에서는 전기차 업체인 토글이 전기차 생산을 시작하고 있습니다.배터리는 중국 회사 파라시스 [57]에너지와 합작으로 만들어 질 것입니다.

경제학

제조원가

전기차에서 가장 비싼 부분은 배터리입니다.가격은 2010년 kWh당 605유로에서 2017년 170유로로,[58][59] 2019년에는 100유로로 하락했습니다.전기 자동차를 설계할 때, 제조업체들은 생산성이 낮으면 개발 비용이 낮을수록 기존 플랫폼을 전환하는 것이 더 저렴할 수도 있지만, 생산성이 높으면 설계와 비용을 [60]최적화하기 위해 전용 플랫폼을 선호할 수도 있습니다.

총소유비용

아직 중국은 아니지만 EU와 미국에서는 연료비와 유지비가 [16][17][61]낮아져 최근 전기차의 총소유비용이 동급 가솔린차보다 저렴합니다.

연간 주행 거리가 클수록 전기차의 총 소유 비용은 동급 ICE [62]차량보다 적을 가능성이 높습니다.손익분기점 거리는 세금, 보조금, 에너지 비용 등에 따라 국가별로 다릅니다.예를 들어, 영국에서는 런던이 [63]버밍엄보다 ICE 자동차에 더 많은 요금을 부과하기 때문에 일부 국가에서는 도시에 따라 비교가 달라질 수 있습니다.

구매비용

몇몇 국가 및 지방 정부는 전기차 및 기타 [64][65][66][67]플러그인의 구매 가격을 낮추기 위해 전기차 인센티브를 제정했습니다.

2020년 기준[update] 전기차 배터리는 자동차 [68]총 비용의 4분의 1 이상입니다.배터리 비용이 2020년대 [69][70]중반으로 전망되는 kWh당 미화 100달러 이하로 떨어지면 구매 가격은 ICE 신차 가격 이하로 떨어질 것으로 예상됩니다.

일부 [71][72]국가에서는 [73]국세와 보조금에 다소 의존해 리스나 청약이 인기를 끌고 있고, 리스차 끝단은 중고 시장을 [74]확대하고 있습니다.

Alix Partners의 2022년 6월 보고서에 따르면 평균 EV의 원재료 비용은 2020년 3월 3,381달러에서 2022년 5월 8,255달러로 상승했습니다.원가 상승의 목소리는 주로 리튬, 니켈,[75] 코발트 때문입니다.

운영비

전기는 거의 항상 주행한 1킬로미터 당 휘발유보다 적게 들지만, 전기의 가격은 자동차가 [76][77]충전되는 장소와 시간에 따라 종종 다릅니다.비용 절감은 [78]지역에 따라 달라질 수 있는 휘발유 가격에도 영향을 받습니다.

환경적 측면

전기자동차는 휘발성 유기화합물, 탄화수소, 일산화탄소, 오존, 납, 각종 [81]질소산화물 등 배기오염물질을 배출하지 않아 지역 대기오염을 크게 줄이는 등 ICE 자동차를 대체할 때 여러 장점이 있습니다.ICE 차량과 유사하게 전기차는 타이어 및 브레이크[82] 마모로 인한 미립자를 배출하여 [83]건강을 해칠 수 있지만, 전기차의 회생 제동은 브레이크 [84]먼지가 적음을 의미합니다.배기가스가 아닌 [85]입자에 대해서는 더 많은 연구가 필요합니다.화석 연료(휘발유 탱크에 유정)의 소싱은 추출 및 정제 과정에서 자원 사용뿐만 아니라 추가적인 손상을 초래합니다.

생산 과정과 차량에 충전할 전기의 공급원에 따라 배출 가스가 도시에서 전기를 생산하고 자동차를 생산하는 공장으로, 그리고 [42]재료의 운송으로 일부 이동할 수 있습니다.배출되는 이산화탄소의 양은 전기원의 배출과 차량의 효율에 따라 달라집니다.그리드에서 나오는 전기의 경우, 수명 주기 배출량은 석탄 화력의 비율에 따라 다르지만 ICE [86]자동차보다 항상 적습니다.

충전 인프라 설치 비용은 3년 [87]이내에 건강 비용 절감으로 상환될 것으로 추정됩니다.2020년 연구에 따르면 남은 세기 동안 리튬 공급과 수요의 균형을 맞추기 위해서는 우수한 재활용 시스템, 차량과 그리드 간의 통합 및 낮은 리튬 [88]운송 강도가 필요합니다.

일부 활동가들과 언론인들은 기후 변화[89] 위기를 해결하는 데 있어 전기 자동차의 영향력이 다른 덜 대중화된 [90]방법들에 비해 부족하다는 인식에 대해 우려를 제기했습니다.이러한 우려는 주로 액티브 모빌리티,[91] 대중 교통 및 e-스쿠터와 같은 덜 탄소 집약적이고 보다 효율적인 형태의 운송 수단의 존재와 자동차를 위해 [92]먼저 설계된 시스템의 지속에 중점을 두고 있습니다.

여론

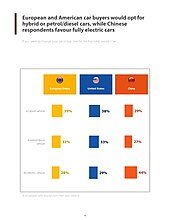

2022년 조사에 따르면 유럽 자동차 구매자의 33%가 새 차량을 구입할 때 가솔린 또는 디젤 자동차를 선택할 것으로 나타났습니다.응답자의 67%가 하이브리드 또는 전기 [94][95]버전을 선택한다고 언급했습니다.보다 구체적으로 살펴보면, 전기차는 유럽인의 28%만이 선호하는 것으로 나타나 가장 선호하지 않는 차종으로 나타났습니다.유럽인의 39%는 하이브리드 차량을 선호하는 반면 33%는 가솔린 또는 디젤 [96][97]차량을 선호합니다.

반면 중국 자동차 구매자의 44%는 전기차를 구매할 가능성이 가장 높은 반면, 미국인의 38%는 하이브리드 자동차를 선택할 것이고, 33%는 가솔린이나 디젤을 선호할 것이며, 29%[96][98]만이 전기차를 구매할 것입니다.

특히 EU의 경우, 65세 이상 차량 구매자의 47%가 하이브리드 차량을 구매할 가능성이 있는 반면, 젊은 응답자의 31%는 하이브리드 차량을 좋은 옵션으로 생각하지 않습니다.35%는 가솔린 또는 디젤 차량을, 24%는 [96][99]하이브리드 대신 전기차를 선택했습니다.

EU에서는 전체 인구의 13%만이 차량을 [96]전혀 소유할 계획이 없습니다.

성능

가속 및 드라이브 트레인 설계

전기 모터는 높은 출력 대 무게 비율을 제공할 수 있습니다.배터리는 이러한 모터를 지지하는 데 필요한 전류를 공급하도록 설계될 수 있습니다.전기 모터는 토크 곡선이 0 속도까지 평평합니다.단순성과 신뢰성을 위해 대부분의 전기차는 고정비 기어박스를 사용하고 클러치가 없습니다.

대부분의 전기 자동차는 일반 ICE 자동차보다 가속력이 빠릅니다. 이는 주로 구동력 마찰 손실이 감소하고 전기 [100]모터의 토크가 빠르게 공급되기 때문입니다.그러나 NEV는 상대적으로 모터가 약하기 때문에 가속력이 낮을 수 있습니다.

또한 전기 자동차는 각 휠 허브 또는 휠 옆에 모터를 사용할 수 있습니다. 이 모터는 드물지만 더 [101]안전하다고 주장됩니다.액슬, 디퍼렌셜 또는 변속기가 없는 전기 차량은 드라이브트레인 관성이 적을 수 있습니다.일부 직류 모터가 장착된 드래그 레이서 EV는 최고 [102]속도를 향상시키기 위해 간단한 2단 수동 변속기를 갖추고 있습니다.컨셉 전기 슈퍼카 Rimac Concept One은 0~97km/h(0~60mph)에서 2.5초 만에 주행할 수 있다고 주장합니다.Tesla는 곧 출시될 Tesla Roadster가 1.[103]9초 안에 0~60mph(0~97km/h)로 달릴 것이라고 주장합니다.

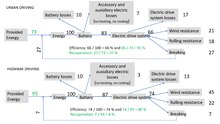

에너지효율

내연 기관은 연료를 연소할 때 생성되는 에너지와 비교하여 차량을 추진하는 데 사용되는 에너지의 비율로 표시되는 효율에 대한 열역학적 한계를 가지고 있습니다.가솔린 엔진은 연료 에너지 함량의 15%만 효율적으로 사용하여 차량을 이동시키거나 액세서리를 동력으로 사용합니다. 디젤 엔진은 20%의 온보드 효율에 도달할 수 있습니다. 전기 자동차는 저장된 화학 에너지를 기준으로 계산할 때 69~72%의 효율을 [104][105]갖거나 충전에 필요한 에너지를 기준으로 계산할 때 약 59~62%의 효율을 갖습니다.

전기 모터는 저장된 에너지를 차량 구동으로 변환하는 데 내연 기관보다 더 효율적입니다.그러나 모든 속도에서 동일하게 효율적이지는 않습니다.이를 위해 이중 전기 모터를 장착한 일부 자동차에는 도시 속도에 최적화된 기어를 장착한 전기 모터가 하나 있고 고속도로 속도에 최적화된 기어를 장착한 두 번째 전기 모터가 있습니다.전자제품은 현재의 속도와 [106]가속도에 가장 효율이 좋은 모터를 선택합니다.전기차에서 가장 흔히 볼 수 있는 회생제동은 [42][104]제동 중 손실되는 에너지의 5분의 1만큼 복구할 수 있습니다.

객실 냉난방

연소 동력 자동차는 엔진에서 나오는 열을 이용하여 실내 난방을 제공하지만 전기 자동차에서는 이 옵션을 사용할 수 없습니다.난방에는 전기 저항 히터를 사용할 수 있지만, [107]Nissan Leaf와 같은 가역적 히트 펌프를 사용하면 보다 높은 효율과 일체형 냉각 효과를 얻을 수 있습니다.PTC 접합[108] 냉각은 2008 Tesla Roadster와 같이 단순성에도 매력적입니다.

일부 모델은 배터리 에너지의 일부를 난방에 사용하여 범위를 줄이는 것을 방지하기 위해 차량이 플러그를 꽂은 상태에서 실내 난방을 할 수 있습니다.예를 들어, Nissan Leaf, Mitsubishi i-MiEV, Renault Zoe 및 Tesla 자동차는 차량이 플러그를 [109][110][111]꽂은 상태에서 예열될 수 있습니다.

일부 전기 자동차(예: 시트로엥 베를링고 일렉트릭)는 보조 난방 시스템(예: Webasto 또는 Eberspächer에서 제조한 가솔린 연료 장치)을 사용하지만 "친환경" 및 "배출가스 제로" 인증을 희생합니다.실내 냉방은 태양광 발전 외장 배터리와 USB 팬 또는 쿨러를 통해 강화할 수 있으며, 주차 시 외부 공기가 자동으로 차를 통과하도록 하여 강화할 수 있습니다. 2010 Toyota Prius의 두 모델에는 이 기능이 [112]옵션으로 포함되어 있습니다.

안전.

BEV의 안전 문제는 크게 국제 표준 ISO 6469에서 다루고 있습니다.이 문서는 특정 문제를 다루는 세 부분으로 나뉩니다.

묵직함

배터리 자체의 무게는 보통 동급 가솔린 차량보다 전기차를 더 무겁게 만듭니다.충돌 시, 무거운 차량의 탑승자는 평균적으로 가벼운 차량의 탑승자보다 더 적은 부상을 입습니다. 따라서,[116] 추가적인 무게는 탑승자에게 안전상의 이점을 가져다 줍니다.평균적으로 사고가 발생하면 2,000파운드(900kg) 차량 탑승자가 3,000파운드([117]1,400kg) 차량 탑승자보다 약 50% 더 많은 부상을 입을 수 있습니다.무거운 차는 보행자나 [118]다른 차량을 들이받으면 차 밖에 있는 사람들에게 더 위험합니다.

안정성.

스케이트보드 구성의 배터리는 무게중심을 낮춰 주행 안정성을 높여 [119]제어력 상실을 통한 사고 위험을 낮춥니다.각 휠 근처 또는 각 휠에 별도의 모터가 있는 경우 핸들링이 [120]개선되어 안전하다고 합니다.

화재위험

ICE의 배터리와 마찬가지로 전기 자동차 배터리도 충돌이나 기계적 고장 [121]후에 불이 붙을 수 있습니다.ICE [122]차량에 비해 거리당 운행 횟수는 적지만 플러그인 전기차 화재 사고가 발생했습니다.일부 자동차의 고전압 시스템은 에어백 [123][124]전개 시 자동으로 차단되도록 설계되어 있으며 고장 시 소방관이 수동 고전압 시스템 [125][126]차단을 위한 교육을 받을 수도 있습니다.ICE 자동차 화재보다 훨씬 더 많은 물이 필요할 수 있으며 배터리 [127][128]화재의 재점화 가능성을 경고하기 위해 열화상 카메라가 권장됩니다.

컨트롤

2018년 현재[update] 대부분의 전기차는 기존의 자동변속기가 장착된 자동차와 유사한 주행제어장치를 갖추고 있습니다.모터가 고정 비율 기어를 통해 휠에 영구적으로 연결될 수 있고, 주차 폴이 존재하지 않을 수 있지만, 모드 "P" 및 "N"이 셀렉터에 제공되는 경우가 많습니다.이 경우 모터는 "N"에서 비활성화되며, 전기적으로 작동되는 핸드 브레이크는 "P" 모드를 제공합니다.

일부 자동차에서는 모터가 천천히 회전하여 기존의 자동 변속기 [129]자동차와 유사하게 "D"에서 약간의 크리프(creep)를 제공합니다.

내연 차량의 가속기가 해제되면 변속기의 종류와 모드에 따라 엔진 제동에 의해 감속될 수 있습니다.EV에는 일반적으로 차량 속도를 늦추고 배터리를 [130]다소 충전하는 회생 제동 기능이 탑재됩니다.회생 제동 시스템은 기존 브레이크(ICE 차량의 엔진 제동과 유사)의 사용을 줄여 브레이크 마모 및 유지 관리 비용을 절감합니다.

건전지

리튬 이온 기반 배터리는 높은 출력과 에너지 [131]밀도를 위해 종종 사용됩니다.니켈과 코발트에 의존하지 않는 리튬철인산화물과 같이 다양한 화학적 조성을 가진 배터리가 점점 더 널리 사용되고 있기 때문에 더 저렴한 배터리와 [132]더 저렴한 자동차를 만드는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.

범위

전기 자동차의 범위는 사용되는 배터리의 수와 유형, 공기 역학, 무게와 차량의 유형, 성능 요구 사항, [134]날씨 등에 따라 달라집니다.주로 도시용으로 판매되는 자동차는 작고 가벼운 [135]상태를 유지하기 위해 단거리 배터리로 제조되는 경우가 많습니다.

대부분의 전기 자동차에는 예상 범위의 디스플레이가 장착되어 있습니다.이는 차량이 어떻게 사용되고 있는지, 배터리가 어떤 전력을 공급하고 있는지를 고려한 것일 수 있습니다.그러나 요인은 경로에 따라 다를 수 있으므로 추정치는 실제 범위와 다를 수 있습니다.이 디스플레이를 통해 운전자는 주행 속도 및 도중 충전 지점에서의 정지 여부에 대한 정보에 입각한 선택을 할 수 있습니다.일부 도로변 지원 기관에서는 [136]전기차 충전을 위해 충전 트럭을 제공하기도 합니다.

충전하는

커넥터

대부분의 전기차는 충전을 위해 전기를 공급하기 위해 유선 연결을 사용합니다.전기차 충전 플러그는 전 세계적으로 보편적이지 않습니다.그러나 한 유형의 플러그를 사용하는 차량은 일반적으로 플러그 [137]어댑터를 사용하여 다른 유형의 충전소에서 충전할 수 있습니다.

Type 2 커넥터는 가장 일반적인 플러그 유형이지만 중국과 [138][139]유럽에서는 다른 버전이 사용됩니다.

Type 1(SAE J1772라고도 함) 커넥터는 북미에서는[140][141] 흔하지만 3상 [142]충전을 지원하지 않기 때문에 다른 지역에서는 흔하지 않습니다.

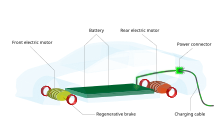

정지해 있는 자동차나 전기 도로의 [143]무선 충전은 2021년 현재는[update] 덜 일반적이지만 일부 도시에서는 [144][145]택시를 위해 사용됩니다.

홈충전

전기 자동차는 보통 가정용 충전소에서 하룻밤 사이에 충전합니다. 충전소, 월박스 충전기 또는 간단히 충전기로 알려져 있습니다. 차고나 [146][147]집 밖에서 충전합니다.2021년 현재[update] 일반 가정용 충전기는 7kW이지만 모두 스마트 충전을 [146]포함하는 것은 아닙니다.화석 연료 차량에 비해 가정용 충전의 기회가 있기 때문에 공공 인프라를 이용한 충전의 필요성이 줄어듭니다. 차량을 연결하고 매일 [148]충전을 시작할 수 있습니다.표준 콘센트에서 충전하는 것도 가능하지만 매우 느립니다.

공용충전

공공 충전소는 가정용 [149]충전기보다 거의 항상 빠르며, 2021년 기준으로[update] 자동차의 AC-DC [150]컨버터를 통과하는 병목 현상을 피하기 위해 직류를 공급하는 곳이 많은데, 가장 빠른 곳은 350kW입니다.[151]

중국에서는 GB/T 27930 규격이, 일본에서는 CCS(Combined Charging System)가 가장 널리 사용되고 있는 충전 [139]표준입니다.미국은 CCS, 테슬라 슈퍼차저, CHAdeMO 충전소가 혼재된 사실상의 표준이 없습니다.

공용 충전소를 이용하여 전기 자동차를 충전하는 것은 화석 연료 자동차에 연료를 넣는 것보다 더 오래 걸립니다.차량이 충전할 수 있는 속도는 충전소의 충전 속도와 충전을 받을 수 있는 차량의 자체 용량에 따라 달라집니다.2021년 현재[update] 일부 자동차는 400V이고 약 800V입니다.[152]매우 빠른 충전이 가능한 차량을 충전소에 연결하면 [153]15분 만에 차량의 배터리를 80%까지 충전할 수 있습니다.충전 속도가 느린 차량과 충전소에서는 배터리를 80%까지 충전하는 데 2시간이나 걸릴 수 있습니다.휴대전화와 마찬가지로 시스템 속도가 느려져 배터리가 안전하게 충전되지 않고 손상되지 않기 때문에 최종 20%가 더 오래 걸립니다.

일부 회사는 배터리 교환 스테이션을 구축하여 [154][155]효과적인 충전 시간을 크게 단축하고 있습니다.일부 전기 자동차(예: BMW i3)에는 옵션인 가솔린 레인지 익스텐더가 있습니다.이 시스템은 장거리 [156]이동을 위한 것이 아니라 다음 충전 위치까지 범위를 확장하기 위한 비상 백업용으로 사용됩니다.

전기도로

스웨덴은 [157]: 12 2013년부터 주행 중 전기자동차에 전력을 공급하고 충전하는 전기도로 기술을 평가하였습니다.평가는 [158]2022년에 끝날 예정이었습니다.철도 전기 도로 시스템(ERS)으로 구동되는 차량에 탑재된 전기 장비에 대한 첫 번째 표준인 CENELEC 기술 표준 50717이 2022년 [159]말에 승인되었습니다."완전한 상호운용성"과 지상 전력 공급을 위한 "통합 및 상호운용 가능한 솔루션"을 포함하는 표준에 따라 2024년 말까지 발표될 예정이며,[160][161] "도로에 내장된 전도성 레일을 통한 통신 및 전력 공급을 위한 사양"을 상세히 설명합니다.스웨덴 최초의 영구 전기도로는 홀스베르크와[162] 외레브로 사이의 E20 노선 구간에 2026년까지 완공된 후, 2045년까지 [163]3000km의 전기도로를 추가로 확장할 계획입니다.프랑스 생태부 실무그룹은 지상급 전력공급 기술을 전기도로의 [164]가장 유력한 후보로 보고 스웨덴, 독일, 이탈리아, 네덜란드, 스페인, 폴란드 [165]등과 함께 유럽 전기도로 표준을 채택할 것을 권고했습니다.프랑스는 2035년까지 300억에서 400억 유로를 전기차, 버스, 트럭을 충전하는 8,800킬로미터에 이르는 전기 도로 시스템에 투자할 계획입니다.2023년까지 [164]전기 도로 기술 평가를 위한 2건의 입찰이 발표될 예정입니다.

차량 대 그리드: 업로드 및 그리드 버퍼링

발전 비용이 매우 높을 수 있는 최대 부하 기간 동안, 차량과 그리드 간 기능을 갖춘 전기 자동차는 그리드에 에너지를 제공할 수 있습니다.따라서 이러한 차량은 피크 시간이 아닌 시간에 더 저렴한 요금으로 충전할 수 있으며, 과도한 야간 시간 발생을 흡수하는 데 도움이 됩니다.차량 내 배터리는 [166]전력을 완충하는 분산 저장 시스템의 역할을 합니다.

수명

모든 리튬 이온 배터리와 마찬가지로 전기 자동차 배터리도 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 특히 100%로 자주 충전되는 경우 성능이 저하될 수 있습니다. 그러나 이는 [167]눈에 띄게 되기까지 최소 몇 년이 걸릴 수 있습니다.일반적인 보증 기간은 8년 또는 100,000마일(160,000km)[168]이지만, 일반적으로 차량에서는 15년에서 20년까지, 다른 용도에서는 [169]더 오래 사용할 수 있습니다.

현재 사용 가능한 전기 자동차

전기차판매

테슬라는 2019년 [170][171]12월 세계 최고의 전기차 제조업체가 되었습니다.모델S는 2015년과 [172][173]2016년 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 전기차, 모델3는 2018년부터 2021년까지 4년 연속 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 전기차, 모델Y는 2022년 [174][175][176][177][178]세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 전기차였습니다.테슬라 모델3는 2020년 초 리프를 제치고 세계 누적 베스트셀링 전기차 [19]1위에 올랐습니다.테슬라는 2020년 3월 100만 번째 전기차를 생산해 자동차 제조사로는 최초로 [179]100만 대 판매를 돌파했고, 2021년 6월에는 모델 3가 전기차로는 최초로 100만 [20]대 판매를 돌파했습니다.Tesla는 [175][180][181][182][176]2018년부터 2021년까지 4년 연속 브랜드 및 자동차 그룹별로 세계 최고의 판매 플러그인 전기차 제조업체로 이름을 올렸습니다.2021년 말 테슬라의 2012년 이후 글로벌 누적 판매량은 총 230만 [183]대이며,[184] 이 중 936,222대가 2021년에 인도되었습니다.

2021년 12월[update] 기준 르노-닛산-미쓰비시 얼라이언스는 2009년 [185][186]이후 미쓰비시 자동차가 생산한 경형 전기차를 포함하여 전 세계에서 100만 대 이상의 전기차 판매량을 기록하며 세계 최고의 전기차 제조업체 중 하나로 선정되었습니다.닛산은 2023년 [187]7월까지 100만 대의 자동차와 밴이 판매되며 얼라이언스 내 글로벌 판매를 주도하고 있으며, 그루페 르노는 트위지 헤비 [188]쿼드리사이클을 포함해 2020년 12월까지 전 세계에서 397,000대 이상의 전기차가 판매되었습니다.미쓰비시의 유일한 전기차는 i-MiEV로, 2015년 3월까지 전 세계에서 50,000대 이상의 판매량을 기록하고 있으며,[189] 일본에서 판매되고 있는 두 개의 미니캡 버전을 포함하여 모든 i-MiEV 모델을 차지하고 있습니다.얼라이언스에서 가장 많이 팔린 닛산 리프는 2013년과 [172]2014년에 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 전기차였습니다.닛산 리프는 2020년 초까지 세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 고속도로 합법 [19]전기차였으며,[187] 2023년 7월 기준 전 세계 판매량은 65만[update] 대를 넘었습니다.

그 외 전기차 제조업체로는 BAIC 자동차가 48만대, SAIC 자동차가 31만4천대, 지리가 22만8천700대로 2019년[update] 12월 기준 중국 내 누적 판매고를 기록하고 있으며,[190] 폭스바겐 [191]등이 있습니다.

다음 표는 전 세계 누적 판매량 250,000대 이상을 기록한 역대 최고의 고속도로 지원 전기차 목록입니다.

| 회사 | 모델 | 시장출시 | 이미지 | 연간글로벌매출액 | 글로벌 총매출액 | 다음을 통한 총 매출액 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

테슬라 주식회사 | 테슬라 모델 3 | 2017-07 |  | 476,336 (2022) | ~206만 | 2023-06 | [174][175][192][193] |

테슬라 주식회사 | 테슬라 모델 Y | 2020-03 |  | 771,300 (2022) | ~184만 | 2023-06 | [174][175][193][194] |

| SAIC-GM-울링 | 우링 홍광 미니 EV | 2020-07 |  | 424,031 (2022) | ~110만(2) | 2023-06 | [174][175][193][195] |

닛산 | 닛산 리프 | 2010-12 |  | 64,201 (2021) | ~650,000 | 2023-07 | [175][187] |

르노 | 르노 조에 | 2012-12 |  | 40,544 (2022) | 413,975 | 2023-06 | [188][196][197] |

BYD | BYD위안플러스/ 아또3(4) | 2022-02 |  | 201,744 (2022) | 403,249 | 2023-06 | [174][193] |

BYD | 비와이디 돌핀 | 2021-08 |  | 205,238 (2022) | 393,348 | 2023-06 | [174][193][198] |

폭스바겐 | 폭스바겐 ID.4 | 2020-09 |  | 174,092 (2022) | 387,014 | 2023-06 | [174][175][193][199] |

GAC 그룹 | 아이온 S | 2019-05 |  | 115,663 (2022) | 380,213 | 2023-06 | [174][175][193][200] |

테슬라 주식회사 | 테슬라 모델 S | 2012-06 |  | ~35,000 (2022) | ~363,900 | 2022-12 | [201] |

BMW | BMW i3 | 2013-11 |  | 28,216 (2021) | 250,000(3) | 2022-12 | [202][203] |

테슬라 주식회사 | 테슬라 모델 X | 2015-09 |  | 37,449 (2022) | ~248,800 | 2023-03 | [204] |

| 폭스바겐 | 폭스바겐 ID.3 | 2020-08 | 236,552 | 2023-06 | [205][206][207][208] | ||

체리 | 체리큐 | 2014-11 |  | 68,821 (2021) | ~243,000(2) | 2021-12 | [175][209][210] |

| GAC 그룹 | 아이온와이 | 2021-04 | 211,721 | 2023-06 | [208][211] | ||

| 주의: (1) 차량은 100km/h(62mph) 이상의 최고 속도를 낼 수 있는 경우 고속도로를 이용할 수 있는 것으로 간주됩니다. (2) 중국 본토에서만 판매 (3) BMW i3 판매는 REX 변종 포함 (분할 불가)2022년 7월 생산 종료 (4) BYD Yuan Plus, 중국 외 일부 시장에서 Atto 3로 불렸습니다. | |||||||

국가별 전기차

2021년 세계 도로의 총 전기 자동차 수는 약 1,650만 대에 달했습니다.2022년 1분기 전기차 판매량이 200만 [212]대까지 늘었습니다.중국은 2019년 말 전 세계 전기차 보유량의 절반(53.9%)이 넘는 258만대를 보유하고 있어 전 세계 전기차 보유량이 가장 많습니다.

모든 전기차는 2012년부터 [213][177][178]플러그인 하이브리드 자동차를 과잉 판매해 왔습니다.

정부 정책 및 인센티브

세계 여러 국가, 지방 및 지방 정부는 플러그인 전기차의 대중 시장 채택을 지원하기 위한 정책을 도입했습니다.소비자와 제조업체에 대한 재정적 지원, 비금전적 인센티브, 충전 인프라 구축을 위한 보조금, 건물 내 전기차 충전소, 그리고 특정 [214][224][225]대상에 대한 장기적 규제 등 다양한 정책이 마련되어 있습니다.

| 선택된 국가 | 연도 |

|---|---|

| 노르웨이(ZEV 100% 판매) | 2025 |

| 덴마크 | 2030 |

| 아이슬란드 | |

| 아일랜드 | |

| 네덜란드 (ZEV 100% 판매) | |

| 스웨덴 | |

| 영국 (ZEV 100% 판매) | 2035 |

| 프랑스. | 2040 |

| 캐나다 (ZEV 100% 판매) | |

| 싱가포르 | |

| 독일(ZEV 100% 판매) | 2050 |

| 미국 (ZEV 10개 주) | |

| 일본(HEV/PHEV/ZEV 100% 판매) |

소비자들을 위한 재정적 인센티브는 전기차의 더 높은 초기 비용으로 인해 전기차 구매 가격을 기존의 자동차와 경쟁력 있게 만드는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다.배터리 크기에 따라 보조금, 세액공제 등 일회성 구매 인센티브, 수입 관세 면제, 도로 통행료 및 혼잡통행료 면제, 등록비 및 연회비 면제 등의 혜택이 있습니다.

비금전적 인센티브 중에는 플러그인 차량의 버스전용차로 및 고점유 차량전용차로 접근 허용, 무료주차 및 [224]무료충전 등 여러 혜택이 있습니다.자가용 소유를 제한하는 일부 국가 또는 도시(예: 신차 구입 할당제) 또는 영구적인 주행 제한(예: 무주행일)을 시행한 일부 국가 또는 도시는 [227][228][229][230][231][232]채택을 촉진하기 위해 전기 자동차를 제외하도록 합니다.영국, 인도 등 여러 나라에서 특정 [225][233][234]건물에 전기차 충전소를 의무화하는 규제를 도입하고 있습니다.

일부 정부에서는 제로 배기가스 차량(ZEV) 의무화, 국가 또는 지역의2 CO 배출 규제, 엄격한 연비 기준, 내연기관 차량 [214][224]판매의 단계적 폐지 등과 같은 특정 대상을 두고 장기적인 규제 신호를 마련하기도 했습니다.예를 들어, 노르웨이는 2025년까지 모든 신차 판매가 ZEV(배터리 전기 또는 수소)[235][236]가 되어야 한다는 국가 목표를 세웠습니다.이러한 인센티브는 내연 자동차로부터 더 빠른 전환을 촉진하는 것을 목표로 하지만, 일부 경제학자들은 전기 자동차 시장에서 과도한 중량 손실을 초래하고, 이는 환경적 [237][238][239]이익에 부분적으로 반작용할 수 있다고 비판합니다.

주요 제조업체의 EV 계획

이 섹션의 예와 관점은 주로 중국 밖에서 다루며 주제에 대한 전 세계적인 관점을 나타내지 않습니다.(2021년 8월 (이메시지를 및 ) |

전기 자동차(EV)는 최근 몇 년간 전 세계 자동차 환경의 필수 요소로서 상당한 주목을 받고 있습니다.전 세계 주요 자동차 회사들은 EV를 전략 계획의 중요한 구성 요소로 채택하여 지속 가능한 운송으로 패러다임이 전환되고 있음을 보여주고 있습니다.

| 현재 | 제조자 | 투자. | 투자. 기간 | # 전기차 | 연도 골 | 메모들 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-11 | 폭스바겐 | 860억 달러 | 2025 | 27 | 2022 | "Modular Electric Toolkit"라는 전용 EV 플랫폼에서 2022년까지 27대의 전기차를 계획하고 MEB로 [240]시작합니다.2020년 11월 전기차 개발 및 전기차 시장 점유율 확대를 목표로 향후 5년간 860억 달러를 투자할 계획임을 발표했습니다.총 자본 지출에는 "디지털 공장", 자동차 소프트웨어 및 자율 주행 [241]자동차가 포함됩니다. |

| 2020-11 | 지엠 | 270억 달러 | 30 | 2035 | EV 및 자율 주행 투자를 200억 달러에서 270억 달러로 늘리고 있으며, 현재 2025년 말까지 30대의 EV(Hummer EV, 캐딜락 라이릭 SUV, Buick, GMC 및 Chevy 소형 크로스오버 [243]EV 포함)를 시장에 출시할 계획이라고 발표했습니다.바라 CEO는 GM이 2025년 [244]말까지 미국에서 제공할 차량의 40%가 배터리 전기차가 될 것이라고 말했습니다.GM의 "BEV3" 차세대 전기차 플랫폼은 프론트, 리어 및 사륜구동 [245]구성과 같은 다양한 차량 유형에서 사용할 수 있도록 유연하게 설계되었습니다. | |

| 2019-01 | 메르세데스 | 230억 달러 | 2030 | 10 | 2022 | 2030년까지 글로벌 매출 50%까지 전기차 생산 확대 계획또한 대부분의 처리 요구 [246]사항을 닛산 리프에 의존하고 있습니다. |

| 2019-07 | 포드 | 290억 달러 | 2025 | 폭스바겐의 [248]모듈형 전기 툴킷("MEB")을 사용하여 2023년부터 자체적으로 완전 전기차를 설계 및 제작할 예정입니다.포드 머스탱 마하-E는 최대 480km(300마일)[249]에 달하는 전기 크로스오버입니다.포드는 2021년에 [250][251]전기 F-150을 출시할 예정입니다. | ||

| 2019-03 | BMW | 12 | 2025 | 무게와 비용을 절감하고 [252]용량을 늘릴 수 있는 5세대 전기 파워트레인 아키텍처를 사용하여 2025년까지 12대의 모든 전기차를 계획합니다.BMW는 2021년부터 [253][254][255]2030년까지 100억 유로 규모의 배터리 셀을 주문했습니다. | ||

| 2020-01 | 현대 | 23 | 2025 | 2025년까지 [256]순수 전기차 23대 계획 발표현대는 2021년 [257]차세대 전기차 플랫폼인 e-GMP를 발표할 예정입니다. | ||

| 2019-06 | 토요타 | 3열 SUV, 스포티 세단, 소형 크로스오버 또는 [258]박시 컴팩트를 수용할 수 있는 e-TNGA라는 글로벌 EV 플랫폼을 개발했습니다.토요타와 스바루는 [259]공유 플랫폼에서 새로운 EV를 출시할 예정입니다. 그것은 토요타 RAV4나 스바루 포레스터 정도의 크기가 될 것입니다. | ||||

| 2019-04 | 자동차 회사 29개 | 3천억 달러 | 2029 | 로이터 통신이 29개 글로벌 자동차 업체를 대상으로 분석한 결과, 자동차 업체들은 향후 5년에서 10년간 3천억 달러를 전기차에 투자할 계획이며, 투자의 45%는 [260]중국에서 이루어질 것으로 예상됩니다. | ||

| 2020-10 | 피아트 | 2021년 [261][262]초부터 유럽 판매를 시작하는 뉴 500의 새로운 전기 버전 출시 | ||||

| 2020-11 | 닛산 | 2025년부터 중국서 전기차·하이브리드차만 판매하겠다는 계획 발표, 9종 신모델 선보임닛산의 다른 계획에는 2035년까지 배출가스 제로 차량의 절반과 가솔린 [263]전기 하이브리드 차량의 절반이 포함됩니다.2018년 닛산의 럭셔리 브랜드인 인피니티는 2021년까지 새롭게 선보이는 모든 차량이 전기 또는 하이브리드 [264]차량이 될 것이라고 발표했습니다. | ||||

| 2020-12 | 아우디 | 350억 유로 | 2021–2025 | 20 | 2025 | 2025년까지 30대의 신형 전동화 모델, 그 중 20대의 PEV.[265]아우디는 2030~2035년까지 전기차만 [266]판매할 계획입니다. |

예보

딜로이트는 [267]2030년 전 세계 전기차 판매량이 3110만대에 이를 것으로 전망했습니다.국제에너지기구는 현재 정책에 따라 2030년까지 전 세계 전기차 재고가 거의 1억4천500만대에 이를 것으로 예상했으며, 지속가능개발 정책이 채택될 경우 [268]2억3천만대에 이를 것으로 예상했습니다.

참고 항목

- 전기차

- 솔라카

- 전기차 에너지 효율

- 전기이륜차와 스쿠터

- 전기 자동차 경고음 - 보행자 안전을 위한 차량음

- 전동모터스포츠

- 에코 그랑프리

- 포뮬러 E

- 현재 사용 가능한 전기차 목록

- V2X(Vehicle-to-Everything

- 화석 연료 차량의 단계적 폐기

참고문헌

- ^ "Reducing Pollution with Electric Vehicles". www.energy.gov. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "How to charge an electric car". Carbuyer. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Executive summary – Global EV Outlook 2023 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Governor Newsom Announces California Will Phase Out Gasoline-Powered Cars & Drastically Reduce Demand for Fossil Fuel in California's Fight Against Climate Change". California Governor. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Groom, David Shepardson, Nichola (29 September 2020). "U.S. EPA chief challenges California effort to mandate zero emission vehicles in 2035". Reuters. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 유지 : 여러 이름 : 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ Thunberg, Greta; Anable, Jillian; Brand, Christian (2022). "Is the Future Electric?". The Climate Book. Penguin. pp. 271–275. ISBN 978-0593492307.

- ^ "EU proposes effective ban for new fossil-fuel cars from 2035". Reuters. 14 July 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "IEA: EVs Will Account For 20% Of All Car Sales This Year". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "How China put nearly 5 million new energy vehicles on the road in one decade International Council on Clean Transportation". theicct.org. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Liu Wanxiang (12 January 2017). "中汽协:2016年新能源汽车产销量均超50万辆,同比增速约50%" [China Auto Association: 2016 new energy vehicle production and sales were over 500,000, an increase of about 50%] (in Chinese). D1EV.com. Retrieved 12 January 2017. 2016년 중국의 신에너지 자동차 판매량은 총 50만 7천 대로, 전체 전기차 40만 9천 대와 플러그인 하이브리드 9만 8천 대로 구성되어 있습니다.

- ^ Automotive News China (16 January 2018). "Electrified vehicle sales surge 53% in 2017". Automotive News China. Retrieved 22 May 2020. 2017년 국내에서 생산된 신에너지 차량의 중국 판매량은 총 77만 7천 대로, 전체 전기차 65만 2천 대와 플러그인 하이브리드 12만 5천 대로 구성되어 있습니다.국내 생산 신에너지 승용차 판매량은 총 57만 9천 대로, 전기차 46만 8천 대, 플러그인 하이브리드 11만 1천 대 등입니다.중국에서는 국산 전기차, 플러그인 하이브리드, 연료전지차만 정부 보조금을 받을 수 있습니다.

- ^ "中汽协:2018年新能源汽车产销均超125万辆,同比增长60%" [China Automobile Association: In 2018, the production and sales of new energy vehicles exceeded 1.25 million units, a year-on-year increase of 60%] (in Chinese). D1EV.com. 14 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019. 2018년 중국의 신에너지차 판매량은 총 125만 6천 대로, 전체 전기차 98만 4천 대, 플러그인 하이브리드차 27만 1천 대로 구성되어 있습니다.

- ^ Kane, Mark (4 February 2020). "Chinese NEVs Market Slightly Declined In 2019: Full Report". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020. 2019년 신에너지차 판매량은 총 120만 6천 대로 2018년 대비 4.0% 감소했으며 연료전지차는 2,737대가 포함되어 있습니다. 배터리 전기차 판매량은 97만2000대(1.2% 감소), 플러그인 하이브리드 판매량은 23만2000대(14.5% 감소)로 집계됐습니다. 판매 수치에는 승용차, 버스, 상용차 등이 포함됩니다.

- ^ China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) (14 January 2021). "Sales of New Energy Vehicles in December 2020". CAAM. Retrieved 8 February 2021. 2020년 중국 내 NEV 판매량은 총 163만 7천 대로 승용차 124만 6천 대, 상용차 12만 1천 대입니다.

- ^ China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) (12 January 2022). "Sales of New Energy Vehicles in December 2021". CAAM. Retrieved 13 January 2022. 2021년 중국 내 NEV 판매량은 총 352만1000대(전 클래스)로 승용차 333만4000대, 상용차 18만6000대로 구성되어 있습니다.

- ^ a b Preston, Benjamin (8 October 2020). "EVs Offer Big Savings Over Traditional Gas-Powered Cars". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Electric Cars: Calculating the Total Cost of Ownership for Consumers" (PDF). BEUC (The European Consumer Organisation). 25 April 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2021.

- ^ "The Tesla Model Y Is The Best-Selling Car In The World GreenCars". www.greencars.com. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d Holland, Maximilian (10 February 2020). "Tesla Passes 1 Million EV Milestone & Model 3 Becomes All Time Best Seller". CleanTechnica. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Shahan, Zachary (26 August 2021). "Tesla Model 3 Has Passed 1 Million Sales". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Hamid, Umar Zakir Abdul (2022). "Autonomous, Connected, Electric and Shared Vehicles: Disrupting the Automotive and Mobility Sectors". US: SAE. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

{{cite journal}}:저널 요구사항 인용journal=(도움말) - ^ "US Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 49 CFR Part 571 Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards". Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ "Citizens' summary EU proposal for a Regulation on L-category vehicles (two- or three-wheel vehicles and quadricycles)". European Commission. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Roth, Hans (March 2011). Das erste vierrädrige Elektroauto der Welt [The first four-wheeled electric car in the world] (in German). pp. 2–3.

- ^ Wakefield, Ernest H (1994). History of the Electric Automobile. Society of Automotive Engineers. pp. 2–3. ISBN 1-5609-1299-5.

- ^ Guarnieri, M. (2012). Looking back to electric cars. Proc. HISTELCON 2012 – 3rd Region-8 IEEE HISTory of Electro – Technology Conference: The Origins of Electrotechnologies. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/HISTELCON.2012.6487583. ISBN 978-1-4673-3078-7.

- ^ "Electric Car History". Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "World's first electric car built by Victorian inventor in 1884". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Boyle, David (2018). 30-Second Great Inventions. Ivy Press. p. 62. ISBN 9781782406846.

- ^ Denton, Tom (2016). Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9781317552512.

- ^ "Elektroauto in Coburg erfunden" [Electric car invented in Coburg]. Neue Presse Coburg (in German). Germany. 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "Electric automobile". Encyclopædia Britannica (online). Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Gerdes, Justin (11 May 2012). "The Global Electric Vehicle Movement: Best Practices From 16 Cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ Says, Alan Brown (9 July 2012). "The Surprisingly Old Story of London's First Ever Electric Taxi". Science Museum Blog. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Handy, Galen (2014). "History of Electric Cars". The Edison Tech Center. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Some Facts about Electric Vehicles". Automobilesreview. 25 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ Gertz, Marisa; Grenier, Melinda (5 January 2019). "171 Years Before Tesla: The Evolution of Electric Vehicles". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Cub Scout Car Show (PDF), January 2008, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 12 April 2009

- ^ Laukkonen, J.D. (1 October 2013). "History of the Starter Motor". Crank Shift. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

This starter motor first showed up on the 1912 Cadillac, which also had the first complete electrical system, since the starter doubled as a generator once the engine was running. Other automakers were slow to adopt the new technology, but electric starter motors would be ubiquitous within the next decade.

- ^ http://www.np-coburg.de/lokal/coburg/coburg/Elektroauto-in-Coburg-erfunden;art83423,1491254 np-coburg.de

- ^ "Elwell-Parker, Limited". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Sperling, Daniel; Gordon, Deborah (2009). Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability. Oxford University Press. pp. 22–26. ISBN 978-0-19-537664-7.

- ^ Boschert, Sherry (2006). Plug-in Hybrids: The Cars that will Recharge America. New Society Publishers. pp. 15–28. ISBN 978-0-86571-571-4.

- ^ 누가 전기차를 죽였는지 보세요?(2006)

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (26 April 2015). "Electric Car Evolution". Clean Technica. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016. 2008: Tesla Roadster는 리튬 이온 배터리 셀을 사용하는 최초의 생산용 전기 자동차가 될 뿐만 아니라 한 번 충전으로 200마일 이상의 범위를 가진 최초의 생산용 전기 자동차가 되었습니다.

- ^ Blum, Brian. Totaled : the billion-dollar crash of the startup that took on big auto, big oil and the world. ISBN 978-0-9830428-2-2. OCLC 990318853.

- ^ Kim, Chang-Ran (30 March 2010). "Mitsubishi Motors lowers price of electric i-MiEV". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Best-selling electric car". Guinness World Records. 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ David B. Sandalow, ed. (2009). Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington? (1st. ed.). The Brookings Institution. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-8157-0305-1. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2011.소개 참조

- ^ "DRIVING A GREEN FUTURE: A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CHINA'S ELECTRIC VEHICLE DEVELOPMENT AND OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Automakers raise prices for NEVs in China ahead of subsidy cuts". KrASIA. 3 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Evans, Scott (10 July 2019). "2013 Tesla Model S Beats Chevy, Toyota, and Cadillac for Ultimate Car of the Year Honors". MotorTrend. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

We are confident that, were we to summon all the judges and staff of the past 70 years, we would come to a rapid consensus: No vehicle we've awarded, be it Car of the Year, Import Car of the Year, SUV of the Year, or Truck of the Year, can equal the impact, performance, and engineering excellence that is our Ultimate Car of the Year winner, the 2013 Tesla Model S.

- ^ "Global EV Outlook 2023 / Trends in electric light-duty vehicles". International Energy Agency. April 2023. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023.

- ^ 자료출처

- ^ Ali, Shirin (23 March 2022). "More Americans are buying electric vehicles, as gas car sales fall, report says". The Hill.

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (23 March 2022). "Oman makes first electric car in the Middle East". Green Prophet. Canada. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (22 May 2022). "Turkey's all electric Togg EV". Green Prophet. Canada. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Trotz fallender Batteriekosten bleiben E-Mobile teuer" [Despite falling battery costs electric cars remain expensive]. Umwelt Dialog (in German). Germany. 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Hauri, Stephan (8 March 2019). "Wir arbeiten mit Hochdruck an der Brennstoffzelle" [We are working hard on the fuel cell]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Switzerland. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Ward, Jonathan (28 April 2017). "EV supply chains: Shifting currents". Automotive Logistics. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Ouyang, Danhua; Zhou, Shen; Ou, Xunmin (1 February 2021). "The total cost of electric vehicle ownership: A consumer-oriented study of China's post-subsidy era". Energy Policy. 149: 112023. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112023. ISSN 0301-4215. S2CID 228862530.

- ^ "Large Auto Leasing Company: Electric Cars Have Mostly Lower Total Cost in Europe". CleanTechnica. 9 May 2020. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Birmingham clean air charge: What you need to know". BBC. 13 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – Japanese Government Incentives for the Purchase of Environmentally Friendly Vehicles" (PDF). Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ Motavalli, Jim (2 June 2010). "China to Start Pilot Program, Providing Subsidies for Electric Cars and Hybrids". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "Growing Number of EU Countries Levying CO2 Taxes on Cars and Incentivizing Plug-ins". Green Car Congress. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Notice 2009–89: New Qualified Plug-in Electric Drive Motor Vehicle Credit". Internal Revenue Service. 30 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "Batteries For Electric Cars Speed Toward a Tipping Point". Bloomberg.com. 16 December 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "EV-internal combustion price parity forecast for 2023 – report". MINING.COM. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Why are electric cars expensive? The cost of making and buying an EV explained". Hindustan Times. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Stock, Kyle (3 January 2018). "Why early EV adopters prefer leasing – by far". Automotive News. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ Ben (14 December 2019). "Should I Lease An Electric Car? What To Know Before You Do". Steer. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Subsidies slash EV lease costs in Germany, France". Automotive News Europe. 15 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "To Save the Planet, Get More EVs Into Used Car Lots". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Wayland, Michael (22 June 2022). "Raw material costs for electric vehicles have doubled during the pandemic". CNBC. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ McMahon, Jeff. "Electric Vehicles Cost Less Than Half As Much To Drive". Forbes. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "How much does it cost to charge an electric car?". Autocar. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Kaminski, Joe (17 August 2021). "The U.S. States Where You'll Save the Most Switching from Gas to Electric Vehicles". www.mroelectric.com. MRO Electric. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Romero, Simon (2 February 2009). "In Bolivia, Untapped Bounty Meets Nationalism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ "Página sobre el Salar (Spanish)". Evaporiticosbolivia.org. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Vehicle exhaust emissions What comes out of a car exhaust? RAC Drive". www.rac.co.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Tyre pollution 1000 times worse than tailpipe emissions". www.fleetnews.co.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Baensch-Baltruschat, Beate; Kocher, Birgit; Stock, Friederike; Reifferscheid, Georg (1 September 2020). "Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP) - A review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment". Science of the Total Environment. 733: 137823. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.733m7823B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137823. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 32422457.

- ^ "EVs: Clean Air and Dirty Brakes". The BRAKE Report. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the evidence for health effects associated with exposure to non-exhaust particulate matter from road transport" (PDF). UK Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020.

- ^ "A global comparison of the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of combustion engine and electric passenger cars International Council on Clean Transportation". theicct.org. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Electric car switch on for health benefits". UK: Inderscience Publishers. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Greim, Peter; Solomon, A. A.; Breyer, Christian (11 September 2020). "Assessment of lithium criticality in the global energy transition and addressing policy gaps in transportation". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4570. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4570G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18402-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7486911. PMID 32917866.

- ^ Casson, Richard. "We don't just need electric cars, we need fewer cars". Greenpeace International. Greenpeace. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "Let's Count the Ways E-Scooters Could Save the City". Wired. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Brand, Christian (29 March 2021). "Cycling is ten times more important than electric cars for reaching net-zero cities". The Conversation. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Laughlin, Jason (29 January 2018). "Why is Philly Stuck in Traffic?". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (20 April 2022). The EIB Climate Survey 2021-2022 - Citizens call for green recovery. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5223-8.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric". EIB.org. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ fm (2 February 2022). "Cypriots prefer hybrid or electric cars". Financial Mirror. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric". EIB.org. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "Germans less enthusiastic about electric cars than other Europeans - survey". Clean Energy Wire. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Rahmani, Djamel; Loureiro, Maria L. (21 March 2018). "Why is the market for hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) moving slowly?". PLOS ONE. 13 (3): e0193777. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1393777R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193777. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5862411. PMID 29561860.

- ^ "67% of Europeans will opt for a hybrid or electric vehicle as their next purchase, says EIB survey". Mayors of Europe. 2 February 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Threewitt, Cherise (15 January 2019). "Gas-powered vs. Electric Cars: Which Is Faster?". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "In-wheel motors: The benefits of independent wheel torque control". E-Mobility Technology. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Hedlund, R. (November 2008). "The Roger Hedlund 100 MPH Club". National Electric Drag Racing Association. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ DeBord, Matthew (17 November 2017). "The new Tesla Roadster can do 0–60 mph in less than 2 seconds – and that's just the base version". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ a b Shah, Saurin D. (2009). "2". Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington? (1st ed.). The Brookings Institution. pp. 29, 37 and 43. ISBN 978-0-8157-0305-1.

- ^ "Electric Car Myth Buster – Efficiency". CleanTechnica. 10 March 2018. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Sensiba, Jennifer (23 July 2019). "EV Transmissions Are Coming, And It's A Good Thing". CleanTechnica. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Can heat pumps solve cold-weather range loss for EVs?". Green Car Reports. 8 August 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ US 5889260, Golan, Gad & Galperin, Yuly, "전기 PTC 가열 장치", 1999-03-30 공개

- ^ NativeEnergy (7 September 2012). "3 Electric Car Myths That Will Leave You Out in the Cold". Recyclebank. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Piotrowski, Ed (3 January 2013). "How i Survived the Cold Weather". The Daily Drive – Consumer Guide Automotive. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "Effects of Winter on Tesla Battery Range and Regen". teslarati.com. 24 November 2014. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "2010 Options and Packages". Toyota Prius. Toyota. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "ISO 6469-1:2019 Electrically propelled road vehicles — Safety specifications — Part 1: Rechargeable energy storage system (RESS)". ISO. April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "ISO 6469-2:2018 Electrically propelled road vehicles — Safety specifications — Part 2: Vehicle operational safety". ISO. February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "ISO 6469-3:2018 Electrically propelled road vehicles — Safety specifications — Part 3: Electrical safety". ISO. October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ National Research Council; Transportation Research Board; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Board on Energy and Environmental Systems; Committee on the Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards (2002). Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards. National Academies Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-309-07601-2. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Vehicle Weight, Fatality Risk and Crash Compatibility of Model Year 1991–99 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks" (PDF). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. October 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Valdes-Dapena, Peter (7 June 2021). "Why electric cars are so much heavier than regular cars". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Wang, Peiling (2020). "Effect of electric battery mass distribution on electric vehicle movement safety". Vibroengineering PROCEDIA. 33: 78–83. doi:10.21595/vp.2020.21569. S2CID 225065995. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Protean Electric's In-Wheel Motors Could Make EVs More Efficient". IEEE Spectrum. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Spotnitz, R.; Franklin, J. (2003). "Abuse behavior of high-power, lithium-ion cells". Journal of Power Sources. 113 (1): 81–100. Bibcode:2003JPS...113...81S. doi:10.1016/S0378-7753(02)00488-3. ISSN 0378-7753.

- ^ "Roadshow: Electric cars not as likely to catch fire as gasoline powered vehicles". The Mercury News. 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "Detroit First Responders Get Electric Vehicle Safety Training". General Motors News (Press release). 19 January 2011. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "General Motors Kicks Off National Electric Vehicle Training Tour For First Responders". Green Car Congress. 27 August 2010. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ AOL Autos (16 December 2011). "Chevy Volt Unplugged: When To Depower Your EV After a Crash". Translogic. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "2011 LEAF First Responder's Guide" (PDF). Nissan North America. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "What firefighters need to know about electric car batteries". FireRescue1. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "04.8 EV fire reignition". EV Fire Safe. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "Ford Focus BEV – Road test". Autocar.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Lampton, Christopher (23 January 2009). "How Regenerative Braking Works". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "What happens to old electric vehicle batteries?". WhichCar. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "What Tesla's bet on iron-based batteries means for manufacturers". TechCrunch. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Fuel Economy Guide, Model Year 2020 (PDF) (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Liasi, Sahand Ghaseminejad; Golkar, Masoud Aliakbar (2 May 2017). Electric vehicles connection to microgrid effects on peak demand with and without demand response. 2017 Iranian Conference. IEEE. pp. 1272–1277. doi:10.1109/IranianCEE.2017.7985237.

- ^ "Best small electric cars 2021". Auto Express. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Lambert, Fred (6 September 2016). "AAA says that its emergency electric vehicle charging trucks served "thousands" of EVs without power". Electrek. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "Diginow Super Charger V2 opens up Tesla destination chargers to other EVs". Autoblog. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "ELECTRIC VEHICLE CHARGING IN CHINA AND THE UNITED STATES" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2019.

- ^ a b "CCS Combo Charging Standard Map: See Where CCS1 And CCS2 Are Used". InsideEVs. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Rulemaking: 2001-06-26 Updated and Informative Digest ZEV Infrastructure and Standardization" (PDF). title 13, California Code of Regulations. California Air Resources Board. 13 May 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

Standardization of Charging Systems

- ^ "ARB Amends ZEV Rule: Standardizes Chargers & Addresses Automaker Mergers" (Press release). California Air Resources Board. 28 June 2001. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

the ARB approved the staff proposal to select the conductive charging system used by Ford, Honda and several other manufacturers

- ^ "ACEA position and recommendations for the standardization of the charging of electrically chargeable vehicles" (PDF). ACEA Brussels. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011.

- ^ "Magnetised concrete that charges electric vehicles on the move tested in America". Driving.co.uk from The Sunday Times. 29 July 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Nottingham hosts wireless charging trial". www.fleetnews.co.uk. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Peter (9 September 2020). "Electric vehicles to cut the cord with wireless charging". www.ft.com. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ a b "How to charge your electric car at home". Autocar. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "The Best Home EV Charger Buying Guide For 2020". InsideEVs. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Electric Vehicle Charging: Types, Time, Cost and Savings". Union of Concerned Scientists. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Thinking of buying an electric vehicle? Here's what you need to know about charging". USA Today. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "DC Fast Charging Explained". EV Safe Charge. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "How electric vehicle (EV) charging works". Electrify America. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "New, 800V, electric cars, will recharge in half the time". The Economist. 19 August 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Electric Cars - everything you need to know". EFTM. 2 April 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "EV maker Nio to have 4,000 battery swapping stations globally in 2025". Reuters. 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "EV battery swapping startup Ample charges up operations in Japan, NYC". TechCrunch. 16 June 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Voelcker, John (12 March 2013). "BMW i3 Electric Car: ReX Range Extender Not For Daily Use?". Green Car Reports. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Swedish Transport Administration (29 November 2017), National roadmap for electric road systems (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2020

- ^ Regler för statliga elvägar SOU 2021:73 (PDF), Regeringskansliet (Government Offices of Sweden), 1 September 2021, pp. 291–297, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2021

- ^ "PD CLC/TS 50717 Technical Requirements for Current Collectors for ground-level feeding system on road vehicles in operation", The British Standards Institution, 2022, archived from the original on 2 January 2023, retrieved 2 January 2023

- ^ Final draft: Standardization request to CEN-CENELEC on 'Alternative fuels infrastructure' (AFI II) (PDF), European Commission, 2 February 2022

- ^ Matts Andersson (4 July 2022), Regulating Electric Road Systems in Europe - How can a deployment of ERS be facilitated? (PDF), CollERS2 - Swedish German research collaboration on Electric Road Systems

- ^ "Rebecka Johansson, Ministry of Infrastructure - ERS Regulations, policies and strategies in Sweden", Electric Road Systems - PIARC Online Discussion, 4 November 2021, 14 minutes 25 seconds into the video

- ^ Jonas Grönvik (1 September 2021), "Sverige på väg att bli först med elvägar – Rullar ut ganska snabbt", Ny Teknik

- ^ a b Laurent Miguet (28 April 2022), "Sur les routes de la mobilité électrique", Le Moniteur

- ^ Patrick Pélata; et al. (July 2021), Système de route électrique. Groupe de travail n°1 (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2021

- ^ "Groupe Renault begins large-scale vehicle-to-grid charging pilot". Renewable Energy Magazine. 22 March 2019. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Understanding the life of lithium ion batteries in electric vehicles". Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "What happens to old electric car batteries? National Grid Group". www.nationalgrid.com. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Elektroauto: Elektronik-Geeks sind die Oldtimer-Schrauber von morgen" [Elektroauto: Electronics geeks are the classic car screwdrivers of tomorrow]. Zeit Online (in German). Germany. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Randall, Chris (4 February 2020). "Newest CAM study shows Tesla as EV sales leader". electricdrive.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Kane, Mark (4 January 2020). "Within Weeks, Tesla Model 3 Will Be World's Top-Selling EV of All Time". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.테슬라는 2008년 이후 누적으로 약 90만대의 전기차를 판매했습니다.

- ^ a b Cobb, Jeff (26 January 2017). "Tesla Model S Is World's Best-Selling Plug-in Car For Second Year in a Row". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017. 2016년 매출과 글로벌 누적 매출에 대한 자세한 내용은 두 그래프를 참조하십시오.

- ^ Cobb, Jeff (12 January 2016). "Tesla Model S Was World's Best-Selling Plug-in Car in 2015". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pontes, José (7 February 2023). "World EV Sales Report — Tesla Model Y Wins 1st Best Seller Title In Record Year". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 10 February 2023. "2022년 글로벌 베스트셀링 플러그인 전기차 상위 5대는 테슬라 모델Y(771,300대), BYD 송(BEV + PHEV) 477,094대, 테슬라 모델3(476,336대), 우링홍광미니EV(424,031대), BYD 친플러스(BEV + PHEV) 315,236대였습니다. BYD 한(BEV + PHEV) 판매량은 총 273,323대, BYD 위안플러스 201,744대, VW ID.4 174,092대."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jose, Pontes (30 January 2022). "World EV Sales — Tesla Model 3 Wins 4th Consecutive Best Seller Title In Record Year". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 5 February 2022. "2021년 글로벌 베스트셀링 플러그인 전기차 톱3는 테슬라 모델3(50만713대), 우링훙광 미니EV(42만4138대), 테슬라 모델Y(41만517대) 순이었습니다.닛산 리프 판매량은 6만4201대, 체리Q는 6만8821대로 집계됐습니다.

- ^ a b Jose, Pontes (2 February 2021). "Global Top 20 - December 2020". EVSales.com. Retrieved 3 February 2021. "2020년 전 세계 플러그인 승용차 판매량은 총 3,124,793대이며, BEV 대 PHEV 비율은 69:31, 세계 시장 점유율은 4%입니다.세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 자동차는 테슬라 모델3로 36만5240대가 납품됐고, 2019년 플러그인 승용차 판매 1위 업체는 테슬라로 49만9535대였고, VW가 22만220대로 뒤를 이었습니다.

- ^ a b c Jose, Pontes (31 January 2020). "Global Top 20 - December 2019". EVSales.com. Retrieved 10 May 2020. "2019년 전 세계 플러그인 승용차 판매량은 총 220만 9,831대이며, BEV 대 PHEV 비율은 74:26, 세계 시장 점유율은 2.5%입니다.세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 자동차는 테슬라 모델3로 30만75대가 납품됐고, 2019년 플러그인 승용차 판매 1위 업체는 테슬라로 36만7820대였고, BYD가 22만9506대로 뒤를 이었습니다.

- ^ a b c Jose, Pontes (31 January 2019). "Global Top 20 - December 2018". EVSales.com. Retrieved 31 January 2019. "2018년 전 세계 플러그인 승용차 판매량은 총 2,018,247대이며, BEV는 다음과 같습니다.PHEV 비율 69:31, 시장 점유율 2.1%.세계에서 가장 많이 팔린 플러그인 자동차는 테슬라 모델3였고, 2018년 플러그인 승용차 제조사는 테슬라였고, BYD가 그 뒤를 이었습니다."

- ^ Lambert, Fred (10 March 2020). "Tesla produces its 1 millionth electric car". Electrek. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Jose, Pontes (4 February 2020). "2019 Global Sales by OEM". EVSales.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020. "2019년 자동차 그룹 중에서는 테슬라가 36만7,849대를 납품하며 플러그인 자동차 판매를 이끌었고, BYD가 22만5,757대, 르노-닛산 얼라이언스가 18만3,299대로 뒤를 이었습니다.전체 전기차 부문(2019년 전기차 160만대 판매)에서 테슬라가 다시 1위를 차지했고 BAIC(16만3838대), BYD(153만3085대), 르노닛산 얼라이언스(13만2762대), SAIC(10만5573대) 등이 뒤를 이었습니다.

- ^ Jose, Pontes (3 February 2019). "2018 Global Sales by OEM". EVSales.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019. 2018년 자동차 그룹 중에서는 테슬라가 24만5240대를 납품하며 플러그인 자동차 판매를 주도했고 BYD가 22만9338대, 르노닛산 얼라이언스가 19만2711대로 뒤를 이었습니다.

- ^ Kane, Mark (27 January 2022). "Tesla Q4 2021 Final EV Delivery Numbers And Outlook". InsideEVs. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

Cumulatively, Tesla sold over 2.3 million electric cars.

- ^ "Tesla Fourth Quarter & Full Year 2021 Update" (PDF). Palo Alto: Tesla. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022. 수정 및 최종 생산 및 판매 번호는 표 "운영 요약" 페이지 7 및 8을 참조하십시오.

- ^ "RENAULT, NISSAN & MITSUBISHI MOTORS ANNOUNCE COMMON ROADMAP ALLIANCE 2030: BEST OF 3 WORLDS FOR A NEW FUTURE" (Press release). Paris, Tokyo, Yokohama: Media Alliance Website. 27 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

In the main markets (Europe, Japan, the US, China) 15 Alliance plants already produce parts, motors, batteries for 10 EV models on the streets, with more than 1 million EV cars sold so far and 30 billion e-kilometers driven.

- ^ "2019 Universal Registration Document" (PDF). 19 March 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

Since 2010, the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance has sold over 800,000 100%-electric vehicles

24쪽과 39쪽 참조.르노 전기 프로그램이 시작된 이후, 그룹은 유럽에서 252,000대 이상의 전기차를 판매했고, 전 세계에서 273,550대 이상의 전기차를 판매했습니다.시작 이후 조에는 총 18만1893대, 캉구Z는 4만8821대.E. 2019년 12월까지 전 세계적으로 전기 밴과 트위지 쿼드리사이클 29,118대가 판매되었습니다.조에의 2019년 글로벌 판매량은 48,269대, 강우제는 10,349대입니다. - ^ a b c Kane, Mark (25 July 2023). "Nissan Global BEV Sales Surpassed One Million". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ a b "2020 Universal Registration Document" (PDF). 15 March 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

Since it launched its electric program, Renault has sold more than 370,000 electric vehicles in Europe and more than 397,000 worldwide: 284,800 ZOE, 59,150 KANGOO Z.E., 11,400 FLUENCE Z.E./SM3 Z.E., 4,600 K-Z.E., 31,100 TWIZY, 770 MASTER Z.E. and 5,100 TWINGO Electric in 2020.

28쪽 참조. - ^ Moore, Bill (19 March 2015). "Mitsubishi Firsts". EV World. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Zentrum für Sonnenenergieund Wasserstoff-Forschung Baden-Württemberg (ZSW) (26 February 2020). "ZSW analysis shows global number of EVs at 7.9 million". electrive.com. Retrieved 17 May 2020. 표 참조:글로벌 누적 EV 등록(모델별)

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (15 May 2021). "10 European Countries: Volkswagen ID.4 & ID.3 Top EV Sales List In April, Tesla Model 3 & VW ID.4 In January–April". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Morris, James (29 May 2021). "Tesla Model 3 Is Now 16th Bestselling Car In The World". Forbes. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

(The Model 3) ... is now the bestselling EV of all time as well, with over 800,000 units sold overall.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pontes, José (2 August 2023). "World EV Sales Now 19% Of World Auto Sales!". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 6 August 2023. 2023년 상반기 글로벌 베스트셀링 플러그인 전기차 톱5는 테슬라 모델Y(57만9552대), 테슬라 모델3(27만9320대), BYD 송(BEV + PHEV) 25만9723대, BYD 진플러스(BEV + PHEV) 20만4529대, BYD 위안플러스/아토3(20만1505대) 순이었습니다.우링홍광미니EV는 122,052대, BYD한(BEV+PHEV) 9만6,437대, VWID.486,481대가 판매됐습니다.

- ^ Jose, Pontes (4 February 2021). "Global Electric Vehicle Top 20 — EV Sales Report". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 5 February 2022. 2020년 테슬라 모델 Y의 전 세계 판매량은 총 79,734대입니다.

- ^ Winton, Neil (4 March 2021). "Europe's Electric Car Sales Will Beat 1 Million In 2021, But Growth Will Slow Later; Report". Forbes. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

Globally, according to Inovev, the biggest selling car in 2020 was the Tesla Model 3 – 365,240 with a 17% market share - followed by the Wuling Hong Guang Mini EV (127,651)

- ^ Groupe Renault (January 2022). "Ventes Mensuelles - Statistiques commerciales mensuelles du groupe Renault" [Monthly Sales -Renault Group monthly sales statistics] (in French). Renault.com. Retrieved 10 August 2023. 판매 수치에는 승객용 및 경형 유틸리티 모델이 포함됩니다.해당 링크를 클릭하시면 "MONTHLY-SALES-12-2022" 파일을 다운로드 하실 수 있습니다.XLSX - 588 Ko", "모델별 판매(2)" 탭을 열어 누적 판매 CYTD 2022 및 개정 CYTD 2021의 판매 수치를 확인할 수 있습니다.글로벌 조에 판매량은 승용 및 LCV 모델을 모두 포함하여 2022년 40,544대, 2021년 77,500대를 기록했습니다.

- ^ Groupe Renault (July 2023). "Ventes Mensuelles - Statistiques commerciales mensuelles du groupe Renault" [Monthly Sales -Renault Group monthly sales statistics] (in French). Renault.com. Retrieved 10 August 2023. 판매 수치에는 승객용 및 경형 유틸리티 모델이 포함됩니다.해당 링크를 클릭하시면 "MONTHLY-SALES-06-2023" 파일을 다운로드 하실 수 있습니다.XLSX - 69 Ko", 탭 "모델"을 열어 2023년 6월까지의 누적 매출액 CYTD에 대한 매출액을 확인할 수 있습니다.글로벌 조에의 2023년 상반기 판매량은 승용과 LCV 모두 포함하여 총 11,131대입니다.

- ^ Demandt, Bart. "BYD Dolphin EV". Carsalesbase.com. Retrieved 8 August 2023. "2021년 BYD 돌고래 중국 판매량 총 29,598대"

- ^ Demandt, Bart. "Volkwagen ID.4 Europe Auto Sales Figures". Carsalesbase.com. Retrieved 8 August 2023. 2020년 유럽에서 VWID.4의 판매량은 총 4,810대입니다.

- ^ Demandt, Bart. "GAC Aion S China Auto Sales Figures". Carsalesbase.com. Retrieved 7 August 2023. "아이온S 중국 판매량 2019년 32,125대, 2020년 45,626대"

- ^ Zentrum für Sonnenenergieund Wasserstoff-Forschung Baden-Württemberg (ZSW) (2 August 2023). "Sustained boom in market for electric vehicles: worldwide total 10.8 million - ZSW Data service". ZSW. Retrieved 8 August 2023. "표 참조:테슬라 모델S '글로벌 누적 EV 등록' 2022년 363,900대로 2021년 대비 35,000대 증가

- ^ "Electro-offensive and number one in premium segment: BMW Group posts strong sales for 2021" (Press release). Munich: BMW Group Press Club Global. 12 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

With 28,216 vehicles sold, 5.4 percent more BMW i3 vehicles were sold than in the previous year.

- ^ Kane, Mark (10 July 2022). "BMW i3 Production Comes To An End: 250,000 Were Made". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (22 April 2023). "Tesla Just Passed 4 Million Cumulative Sales (Charts)". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 9 August 2023. "Tesla Vehicle Sales(분기별 제공) 그래프에서 나온 모델별 분기별 데이터.2022년 37,499대, 2023년 3월까지 누적 248,748대 예상 배송Troy Teslike & Clean Technica의 Zach Shahan의 가정에 근거한 추정치"

- ^ "Global Plug-In Car Sales: 900k In December, 6.5 Million In 2021". InsideEVs. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Pontes, José (3 February 2023). "Open the Gates! 25% BEV Share in Europe!". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ "Global Plug-In Electric Car Sales December 2020: Over 570,000 Sold". InsideEVs. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ a b Pontes, José (2 August 2023). "World EV Sales Now 19% Of World Auto Sales!". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Jose, Pontes (21 January 2021). "China December 2020". EVSales.com. Retrieved 7 February 2022. 체리Q의 2020년 판매량은 총 38,214대, BAIC EU 시리즈 판매량은 23,365대입니다.

- ^ Demandt, Bart (2020). "Chery eQ China Sales Figures". Car Sales Base. Retrieved 7 February 2022. 2014년부터 2019년까지 누적 판매량은 총 135,973대입니다.중국으로부터의 자동차 판매 통계는 국내 생산만 포함하고 수입 모델은 제외합니다.

- ^ Pontes, José (7 February 2023). "World EV Sales Report — Tesla Model Y Wins 1st Best Seller Title In Record Year". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ IEA(1983), 글로벌 EV 전망 2022, IEA, 파리 https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2022

- ^ a b Hertzke, Patrick; Müller, Nicolai; Schenk, Stephanie; Wu, Ting (May 2018). "The global electric-vehicle market is amped up and on the rise". McKinsey. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019. 전시 1: 세계 전기 자동차 판매, 2010-17 참조.

- ^ a b c d International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI) (June 2020). "Global EV Outlook 2020: Enterign the decade of electric drive?". IEA Publications. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지 : 여러 이름 : 저자 목록 (링크) 통계부록, 페이지 247-252 참조 (표 A.1 및 A.12 참조).2019년 말 플러그인 전기승용차의 전 세계 재고는 총 720만 대이며, 이 중 47%가 중국에서 운행 중입니다.플러그인 자동차 재고는 배터리 전기차 480만대(66.6%)와 플러그인 하이브리드 240만대(33.3%)로 구성돼 있습니다.또한, 2019년 경상용 플러그인 전기차 재고는 총 37만 8천 대이며, 전기버스는 약 50만 대가 보급되어 있으며, 대부분이 중국에 있습니다. - ^ International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI) (May 2019). "Global EV Outlook 2019: Scaling-up the transition to electric mobility" (PDF). IEA Publications. Retrieved 23 May 2020.International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI) (May 2019). "Global EV Outlook 2019: Scaling-up the transition to electric mobility" (PDF). IEA Publications. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

{{cite web}}CS1 maint: 복수의 이름: 저자 목록(link) 통계부록, pp. 210–213 참조 2018년 말 플러그인 전기승용차의 세계 재고는 총 512만2460대이며, 이 중 배터리 전기차는 329만800대(64.2%)로 집계되었습니다(표 A.1, A.2 참조). - ^ Argonne National Laboratory, United States Department of Energy (28 March 2016). "Fact #918: March 28, 2016 – Global Plug-in Light Vehicles Sales Increased By About 80% in 2015". Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI) (May 2018). "Global EV Outlook 2017: 3 million and counting" (PDF). IEA Publications. Retrieved 23 October 2018.International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI) (May 2018). "Global EV Outlook 2017: 3 million and counting" (PDF). IEA Publications. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

{{cite web}}CS1 메인 : 복수의 명칭 : 저자 목록 (링크) pp. 9–10, 19–23, 29–28, 통계부속서, pp. 107–113 참조. 플러그인 전기승용차의 글로벌 재고는 총 3,109,050대이며, 이 중 배터리 전기차는 192만 8,360대였습니다. - ^ European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) (1 February 2017). "New Passenger Car Registrations By Alternative Fuel Type In The European Union: Quarter 4 2016" (PDF). ACEA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2018. 표 EU + EFTA - 총 전기 충전식 차량 시장별 신차 등록:2015년 1분기 EU + EFTA 총합.

- ^ European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) (1 February 2018). "New Passenger Car Registrations By Alternative Fuel Type In The European Union: Quarter 4 2017" (PDF). ACEA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018. 표 EU + EFTA - 총 전기 충전식 차량 시장별 신차 등록:2017년 1~4분기 및 2016년 1~4분기의 총 EU + EFTA.

- ^ European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) (6 February 2020). "New Passenger Car Registrations By Alternative Fuel Type In The European Union: Quarter 4 2019" (PDF). ACEA. Retrieved 11 May 2020. 표 EU + EFTA - 총 전기 충전식 차량 시장별 신차 등록:2018년 1분기와 2019년 4분기의 총 EU + EFTA.

- ^ Irle, Roland (19 January 2021). "Global Plug-in Vehicle Sales Reached over 3,2 Million in 2020". EV-volumes.com. Retrieved 20 January 2021. 플러그인 매출은 2019년 226만개에서 2020년 324만개로 증가했습니다.유럽은 140만대에 육박하며 2015년 이후 처음으로 중국을 제치고 최대 전기차 시장으로 올라섰습니다.

- ^ "Data Center Service News". EV-Volumes. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Irle, Roland. "Global EV Sales for 2022". EV-Volumes. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Wappelhorst, Sandra; Hall, Dale; Nicholas, Mike; Lutsey, Nic (February 2020). "Analyzing Policies to Grow the Electric Vehicle Market in European Cities" (PDF). International Council on Clean Transportation. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Building Envelopes – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ Tan, Christopher (18 February 2020). "Singapore Budget 2020: Push to promote electric vehicles in move to phase out petrol and diesel vehicles". The Straits Times. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Zhuge, Chengxiang; Wei, Binru; Shao, Chunfu; Shan, Yuli; Dong, Chunjiao (April 2020). "The role of the license plate lottery policy in the adoption of Electric Vehicles: A case study of Beijing". Energy Policy. 139: 111328. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111328.

- ^ "The great crawl". The Economist. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Salazar, Camila (6 July 2013). "Carros híbridos y eléctricos se abren paso en Costa Rica" [Hybrid and electric cars make their way in Costa Rica]. La Nación (San José) (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Decreto 575 de 2013 Alcalde Mayor" [Major's Decree 575 of 2013] (in Spanish). Alcaldía de Bogotá. 18 December 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Vallejo Uribe, Felipe (13 July 2019). "Sancionada ley que da beneficios a propietarios de vehículos eléctricos en Colombia" [Went into effec law that gives benefits to owners of electric vehicles in Colombia] (in Spanish). Revista Movilidad Eléctrica Sostenible. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Elétricos e híbridos: São Paulo aprova lei de incentivo" [All-electric and hybrids: São Paulo approves incentives law]. Automotive Business (in Portuguese). 28 May 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ "Approved Document S: Infrastructure for the charging of electric vehicles" (PDF). GOV.UK.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지 : url-status (링크) - ^ "Charging Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles (EV)" (PDF). Government of India Ministry of Power.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지 : url-status (링크) - ^ "Norwegian EV policy". Norsk Elbilforening (Norwegian Electric Vehicle Association). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Cobb, Jeff (8 March 2016). "Norway Aiming For 100-Percent Zero Emission Vehicle Sales By 2025". HybridCars.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Holland, Stephen; Mansur, Erin; Muller, Nicholas; Yates, Andrew (June 2015). "Environmental Benefits from Driving Electric Vehicles?" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA: w21291. doi:10.3386/w21291. S2CID 108921625.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Christopher (27 April 2022). "Learning From Diesel's Failure: Government and Producer Policy Surrounding Hybrid and Electric Vehicles". doi:10.5281/ZENODO.6496339.

{{cite journal}}:저널 요구사항 인용journal=(도움말) - ^ IRVINE, IAN (2017). "Electric Vehicle Subsidies in the Era of Attribute-Based Regulations". Canadian Public Policy. 43 (1): 50–60. doi:10.3138/cpp.2016-010. ISSN 0317-0861. JSTOR 90001503. S2CID 157078916.

- ^ "VW plans 27 electric cars by 2022 on new platform". Green Car Reports. 19 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Volkswagen Accelerates Investment in Electric Cars as It Races to Overtake Tesla". Bangkok Post.

- ^ "GM plans to exclusively sell electric vehicles by 2035".

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J. (19 November 2020). "General Motors' electric vehicle plan just got bigger, bolder, and more expensive". The Verge.

- ^ LaReau, Jamie L. "GM to bring 30 new electric vehicles to market in next 5 years". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ "GM aims to make Cadillac lead EV brand". electrive.com. 13 January 2019. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Bartlett, Jeff. "Automakers Are Adding Electric Vehicles to Their Lineups. Here's What's Coming". Consumer Reports. © 2023 Consumer Reports, Inc. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ "Ford commits $29 billion to electric and autonomous vehicle development".

- ^ Volkswagen, Ford. "Ford-VW Partnership Expands, Blue Oval Getting MEB Platform For EVs". Motor1.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Hoffman, Conor (18 November 2019). "2021 Ford Mustang Mach-E Will Please EV Fans, Perplex Mustang Loyalists". Car and Driver. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "The era of electrification". Automotive News. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Capparella, Joey (17 January 2019). "An All-Electric Ford F-150 Pickup Truck Is Happening". Car and Driver. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "BMW plans 12 all-electric models by 2025". Green Car Reports. 21 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "BMW boosts CATL battery order to €7.3B, signs €2.9B battery order with Samsung SDI". Green Car Congress. Archived from the original on 22 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "BMW places battery cell orders worth more than $11 billion". Automotive News. 21 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "BMW orders more than 10 billion euros' worth of battery cells". Reuters. 21 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Genesis, Hyundai Kia. "Hyundai Motor Group To Launch 23 Pure Electric Cars By 2025". InsideEVs. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Hyundai and Kia Expand Presence in Global EV Market". Businesskorea (in Korean). 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "What Toyota's next EVs will look like -- and why". Automotive News. 16 June 2019. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "2 EVs on 1 platform: How to tell them apart?". Automotive News. 2 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Charged". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Winton, Neil (26 October 2020). "Fiat Launches New 500 Electric Minicar, Unlikely To Lose $14,000 With Every Sale". Forbes. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Tisshaw, Mark (22 October 2020). "New electric Fiat 500: reborn city car gains £19,995 entry model". Autocar (UK). Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "Nissan to sell only electric and hybrid cars in China by 2025". Nikkei Asia.

- ^ Frost, Laurence; Tajisu, Naomi (16 January 2018). Maler, Sandra; O'Brein, Rosalba (eds.). "Nissan's Infiniti vehicles to go electric". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

All new Infiniti models launched from 2021 will be either electric or so-called "e-Power" hybrids, Saikawa told the Automotive News World Congress in Detroit.

- ^ "Audi increases e-mobility budget to €35 billion". 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Audi-Chef Duesmann: "Tempolimit wird kommen"". 8 January 2021.

- ^ Walton, Bryn; Hamilton, Jamie; Alberts, Geneviève (28 July 2020). "Electric vehicles: Setting a course for 2030". Deloitte.com. Deloitte. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

Our global EV forecast is for a compound annual growth rate of 29 per cent achieved over the next ten years: Total EV sales growing from 2.5 million in 2020 to 11.2 million in 2025, then reaching 31.1 million by 2030.

- ^ "Prospects for electric vehicle deployment". IEA.org. International Energy Agency. April 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

![The Flocken Elektrowagen (1888) was the first four-wheeled electric car in the world[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/1888_Flocken_Elektrowagen.jpg/320px-1888_Flocken_Elektrowagen.jpg)

![Early electric car built by Thomas Parker - photo from 1895[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Thomas_Parker_Electric_car.jpg/349px-Thomas_Parker_Electric_car.jpg)