CD86

CD86분화의 클러스터 86(CD86 및 B7-2라고도 함)은 덴드리트 세포, 랑게르한스 세포, 대식세포, B세포(기억 B세포 포함) 및 기타 항원발현 세포에서 구성적으로 발현되는 단백질이다.[5]CD80과 함께 CD86은 T세포 활성화와 생존에 필요한 비용조절 신호를 제공한다.리간드 바운드에 따라 CD86은 자율규제 및 셀-셀 연관성 또는 규제와 셀-셀 연관성의 감쇠 신호를 보낼 수 있다.[6]

CD86 유전자는 면역글로불린 슈퍼패밀리의 일원인 1형 막단백질을 암호화하고 있다.[7]대체 스플라이싱은 서로 다른 ISO 양식을 인코딩하는 두 개의 대본 변형 결과를 낳는다.추가 대본 변형이 설명되었지만, 이들의 전체 길이 순서는 결정되지 않았다.[8]

구조

CD86은 면역글로불린 슈퍼패밀리의 B7 계열에 속한다.[9]그것은 329개의 아미노산으로 구성된 70 kDa 당단백질이다.CD80과 CD86 모두 리간드 결합 영역을 형성하는 보존된 아미노산 모티브를 공유한다.[10]CD86은 Ig와 같은 세포외 영역(변수와 상수 1개), 투과영역, CD80보다 긴 짧은 세포질 영역으로 구성되어 있다.[11][12] 비용조절 리간즈 CD80과 CD86은 단세포, 덴드리트리틱세포, 심지어 활성화된 B세포와 같은 전문 항원 제시에서 찾을 수 있다.그것들은 또한 T세포와 같은 다른 세포 유형에서도 유도될 수 있다.[13]CD86 표현은 CD80에 비해 풍부하며, 활성화 시 CD86은 CD80보다 빠르게 증가하였다.[14]

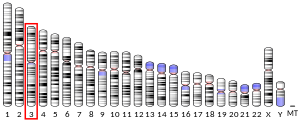

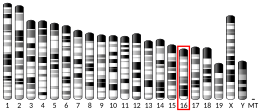

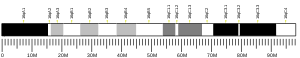

단백질 수준에서 CD86은 CD80과[15] 25%의 정체성을 공유하며, 둘 다 인간 염색체 3q13.33q21에서 코딩된다.[16]

공동 자극, T-세포 활성화 및 억제에서의 역할

CD86과 CD80은 모든 순한 T세포의 표면에서 비용조절 분자 CD28과 [17]억제수용체 CTLA-4(세포독성 T-림프세포 항원-4, CD152로도 알려져 있음)[18][19]에 리간드로 결합한다.CD28과 CTLA-4는 T세포의 자극에 있어 중요한 역할을 하지만 반대 역할을 한다.CD28에 바인딩하면 T세포 반응이 촉진되고 CTLA-4에 바인딩하면 억제된다.[20]

성숙하고 순진한 T세포의 표면에 CD28과 항원발현세포의 표면에 표현된 CD86(CD80)의 상호작용이 T세포 활성화를 위해 필요하다.[21]림프구가 활성화되려면 같은 항원-현상세포에 항원과 비용조절 리간드를 모두 결합해야 한다.T세포 수용체(TCR)는 주요 조직적합성 복합체(MHC) 등급 II 분자와 상호작용하며,[13] 이 신호화는 비용측정이 가능한 리간드가 제공하는 비용측정 신호를 동반해야 한다.이러한 비용측정 신호는 아너지를 예방하기 위해 필요하며 CD80/CD86과 CD28 비용측정 분자의 상호작용에 의해 제공된다.[22][23]

이 단백질 상호작용은 T 림프구가 완전한 활성화 신호를 수신하기 위해서도 필수적이며, 이는 결국 T세포 분화와 분열, 인터루킨 2의 생산과 클론 팽창으로 이어진다.[9][22]CD86과 CD28 사이의 상호작용은 T세포에서 미토겐 활성 단백질 키나아제와 전사 계수 nf-κB를 활성화시킨다.이 단백질들은 CD40L (B-세포 활성화에 사용), IL-21과 IL-21R (분할/확산에 사용),[21] 그리고 IL-2의 생산을 조절한다.이 상호작용은 또한 Tregs라고도 알려진 CD4+CD25+ Tregulator 셀의 동질성을 지원함으로써 자기강도를 조절한다.[9]

CTLA-4는 활성 T세포에서 유도되는 동전 억제 분자다.CTLA-4와 CD80/CD86 사이의 상호작용은 T세포로 음의 신호를 전달하고 세포 표면의 비용조절 분자의 수를 감소시킨다.또한 효소 IODO(indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase)의 발현을 담당하는 신호 경로를 유발할 수 있다.이 효소는 T 림프구의 성공적인 증식과 분화를 위한 중요한 성분인 아미노산 트립토판을 대사시킬 수 있다.IDO는 환경 내 트립토판 농도를 감소시켜 기존 T세포의 활성화를 억제하는 한편 규제 T세포의 기능도 촉진한다.[24][25]

CD80과 CD86 모두 CD28보다 높은 친화력으로 CTLA-4를 바인딩한다.이를 통해 CTLA-4는 CD80/CD86 바인딩에서 CD28을 능가할 수 있다.[23][26]CD80과 CD86 사이에서는 CD80이 CD86보다 CTLA-4와 CD28 모두에 대해 친화력이 높은 것으로 보인다.이는 CD80이 CD86보다 더 강력한 리간드라는 것을 암시하지만,[15] CD80과 CD86 녹아웃 마우스를 사용한 연구는 CD80보다 T세포 활성화에 CD86이 더 중요하다는 것을 보여주었다.[27]

트레그 중재

B7의 경로:CD28 계열은 T세포 활성화와 내성 규제에 핵심적인 역할을 한다.그들의 부정적인 두 번째 신호는 세포 반응의 하향 조절에 책임이 있다.이러한 모든 이유 때문에 이러한 경로가 치료 대상으로 간주된다.[9]

규제 T세포는 CTLA-4를 생성한다.CD80/CD86과의 상호작용 때문에, Tregs는 기존의 T세포와 경쟁할 수 있고 비용절감 신호를 차단할 수 있다.CTLA-4의 트레그 표현은 APC에서 CD80과 CD86을 효과적으로 하향 조절하고 [28]면역 반응을 억제하며 아너지를 증가시킬 수 있다.[6]CTLA-4는 CD28보다 친화력이 높은 CD86에 바인딩되기 때문에, 적절한 T세포 활성화에 필요한 응고율도 영향을 받는다.[29]Treg cells가 CD80과 CD86을 다운규제할 수 있었지만, DC에서는 CD40이나 MHC 클래스 II를 다운규제할 수 없다는 것이 사구라치 그룹의 연구에서 나타났다.다운규제는 항CTLA-4 항체에 의해 차단되었고 Treg 세포가 CTLA-4가 부족하면 취소되었다.[30]

CTLA-4에 바인딩되었을 때 CD86은 트로고사이토시스라고 불리는 과정에서 APC의 표면과 Treg 세포로 제거될 수 있다.[6]항CTLA-4 항체로 이 과정을 차단하는 것은 '부정 면역 조절 억제에 의한 항암 치료'라는 특정 유형의 암 면역요법에 유용하다.[31]일본의 면역학자 혼조 타수쿠와 미국의 면역학자 제임스 P. 앨리슨은 이 주제에 대한 연구로 2018년 노벨 생리의학상을 받았다.

병리학에서의 역할

CD80과 CD86의 역할은 많은 병리학의 맥락에서 연구된다.알레르기성 폐염 및 기도 과응답(AHR) 모델에서 비용 유발 억제제의 선택적 억제를 검사했다.[32]스타필로코쿠스 아우레우스, 특히 T세포에 기초한 면역반응에 대한 초기 숙주반응이 급성폐렴의 병원생성에 기여하는 요소인 만큼, 병원생성에서 CD80/CD86 경로의 역할을 연구했다.[33]비용 측정 분자도 기관지 아스트마,[34] 암의 트레그,[35] 면역 요법 등의 맥락에서 조사되었다.[36]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ a b c GRCh38: 앙상블 릴리스 89: ENSG00000114013 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ a b c GRCm38: 앙상블 릴리스 89: ENSMUSG000022901 - 앙상블, 2017년 5월

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Lenschow DJ, Su GH, Zuckerman LA, Nabavi N, Jellis CL, Gray GS, et al. (December 1993). "Expression and functional significance of an additional ligand for CTLA-4". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (23): 11054–8. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9011054L. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.23.11054. PMC 47920. PMID 7504292.

- ^ a b c Ohue Y, Nishikawa H (July 2019). "Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: Can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target?". Cancer Science. 110 (7): 2080–2089. doi:10.1111/cas.14069. PMC 6609813. PMID 31102428.

- ^ Chen C, Gault A, Shen L, Nabavi N (May 1994). "Molecular cloning and expression of early T cell costimulatory molecule-1 and its characterization as B7-2 molecule". Journal of Immunology. 152 (10): 4929–36. PMID 7513726.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: CD86 CD86 molecule".

- ^ a b c d Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH (2005). "The B7 family revisited". Annual Review of Immunology. 23: 515–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. PMID 15771580.

- ^ Yu C, Sonnen AF, George R, Dessailly BH, Stagg LJ, Evans EJ, et al. (February 2011). "Rigid-body ligand recognition drives cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) receptor triggering". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (8): 6685–96. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.182394. PMC 3057841. PMID 21156796.

- ^ Freeman GJ, Borriello F, Hodes RJ, Reiser H, Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, et al. (November 1993). "Uncovering of functional alternative CTLA-4 counter-receptor in B7-deficient mice". Science. 262 (5135): 907–9. Bibcode:1993Sci...262..907F. doi:10.1126/science.7694362. PMID 7694362.

- ^ Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ (February 2002). "The B7-CD28 superfamily". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 2 (2): 116–26. doi:10.1038/nri727. PMID 11910893. S2CID 205492817.

- ^ a b Murphy K, Weaver C, Janeway C (2017). Janeway's immunobiology (9th ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-8153-4505-3. OCLC 933586700.

- ^ Sansom DM (October 2000). "CD28, CTLA-4 and their ligands: who does what and to whom?". Immunology. 101 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00121.x. PMC 2327073. PMID 11012769.

- ^ a b Collins AV, Brodie DW, Gilbert RJ, Iaboni A, Manso-Sancho R, Walse B, et al. (August 2002). "The interaction properties of costimulatory molecules revisited". Immunity. 17 (2): 201–10. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00362-x. PMID 12196291.

- ^ Mir MA (25 May 2015). Developing costimulatory molecules for immunotherapy of diseases. London. ISBN 978-0-12-802675-5. OCLC 910324332.

- ^ Linsley PS, Brady W, Grosmaire L, Aruffo A, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA (March 1991). "Binding of the B cell activation antigen B7 to CD28 costimulates T cell proliferation and interleukin 2 mRNA accumulation". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 173 (3): 721–30. doi:10.1084/jem.173.3.721. PMC 2118836. PMID 1847722.

- ^ Lim TS, Goh JK, Mortellaro A, Lim CT, Hämmerling GJ, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P (2012). "CD80 and CD86 differentially regulate mechanical interactions of T-cells with antigen-presenting dendritic cells and B-cells". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45185. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745185L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045185. PMC 3443229. PMID 23024807.

- ^ Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire LS, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA (September 1991). "CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 174 (3): 561–9. doi:10.1084/jem.174.3.561. PMC 2118936. PMID 1714933.

- ^ Sansom DM, Manzotti CN, Zheng Y (June 2003). "What's the difference between CD80 and CD86?". Trends in Immunology. 24 (6): 314–9. doi:10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00111-x. PMID 12810107.

- ^ a b Dyck L, Mills KH (May 2017). "Immune checkpoints and their inhibition in cancer and infectious diseases". European Journal of Immunology. 47 (5): 765–779. doi:10.1002/eji.201646875. PMID 28393361.

- ^ a b Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC (March 2001). "The expanding B7 superfamily: increasing complexity in costimulatory signals regulating T cell function". Nature Immunology. 2 (3): 203–9. doi:10.1038/85251. PMID 11224518. S2CID 20542148.

- ^ a b Gause WC, Urban JF, Linsley P, Lu P (1995). "Role of B7 signaling in the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells to effector interleukin-4-producing T helper cells". Immunologic Research. 14 (3): 176–88. doi:10.1007/BF02918215. PMID 8778208. S2CID 20098311.

- ^ Chen L, Flies DB (April 2013). "Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 13 (4): 227–42. doi:10.1038/nri3405. PMC 3786574. PMID 23470321.

- ^ Munn DH, Sharma MD, Mellor AL (April 2004). "Ligation of B7-1/B7-2 by human CD4+ T cells triggers indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in dendritic cells". Journal of Immunology. 172 (7): 4100–10. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4100. PMID 15034022.

- ^ Walker LS, Sansom DM (November 2011). "The emerging role of CTLA4 as a cell-extrinsic regulator of T cell responses". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 11 (12): 852–63. doi:10.1038/nri3108. PMID 22116087. S2CID 9617595.

- ^ Borriello F, Sethna MP, Boyd SD, Schweitzer AN, Tivol EA, Jacoby D, et al. (March 1997). "B7-1 and B7-2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation". Immunity. 6 (3): 303–13. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80333-7. PMID 9075931.

- ^ Walker LS, Sansom DM (February 2015). "Confusing signals: recent progress in CTLA-4 biology". Trends in Immunology. 36 (2): 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.it.2014.12.001. PMC 4323153. PMID 25582039.

- ^ Lightman SM, Utley A, Lee KP (2019-05-03). "Survival of Long-Lived Plasma Cells (LLPC): Piecing Together the Puzzle". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00965. PMC 6510054. PMID 31130955.

- ^ Onishi Y, Fehervari Z, Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S (July 2008). "Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells preferentially form aggregates on dendritic cells in vitro and actively inhibit their maturation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (29): 10113–8. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510113O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711106105. PMC 2481354. PMID 18635688.

- ^ Chen R, Ganesan A, Okoye I, Arutyunova E, Elahi S, Lemieux MJ, Barakat K (March 2020). "Targeting B7-1 in immunotherapy". Medicinal Research Reviews. 40 (2): 654–682. doi:10.1002/med.21632. PMID 31448437. S2CID 201748060.

- ^ Mark DA, Donovan CE, De Sanctis GT, Krinzman SJ, Kobzik L, Linsley PS, et al. (November 1998). "Both CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules regulate allergic pulmonary inflammation". International Immunology. 10 (11): 1647–55. doi:10.1093/intimm/10.11.1647. PMID 9846693.

- ^ Parker D (July 2018). "CD80/CD86 signaling contributes to the proinflammatory response of Staphylococcus aureus in the airway". Cytokine. 107: 130–136. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2018.01.016. PMC 5916031. PMID 29402722.

- ^ Chen YQ, Shi HZ (January 2006). "CD28/CTLA-4--CD80/CD86 and ICOS--B7RP-1 costimulatory pathway in bronchial asthma". Allergy. 61 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01008.x. PMID 16364152. S2CID 23564785.

- ^ Ohue Y, Nishikawa H (July 2019). "Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: Can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target?". Cancer Science. 110 (7): 2080–2089. doi:10.1111/cas.14069. PMC 6609813. PMID 31102428.

- ^ Bourque J, Hawiger D (2018). "Immunomodulatory Bonds of the Partnership between Dendritic Cells and T Cells". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 38 (5): 379–401. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2018026790. PMC 6380512. PMID 30792568.

외부 링크

- UCSC 게놈 브라우저의 인간 CD86 게놈 위치 및 CD86 유전자 세부 정보 페이지.

추가 읽기

- Davila S, Froeling FE, Tan A, Bonnard C, Boland GJ, Snippe H, et al. (April 2010). "New genetic associations detected in a host response study to hepatitis B vaccine". Genes and Immunity. 11 (3): 232–8. doi:10.1038/gene.2010.1. PMID 20237496.

- Csillag A, Boldogh I, Pazmandi K, Magyarics Z, Gogolak P, Sur S, et al. (March 2010). "Pollen-induced oxidative stress influences both innate and adaptive immune responses via altering dendritic cell functions". Journal of Immunology. 184 (5): 2377–85. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0803938. PMC 3028537. PMID 20118277.

- Bossé Y, Lemire M, Poon AH, Daley D, He JQ, Sandford A, et al. (October 2009). "Asthma and genes encoding components of the vitamin D pathway". Respiratory Research. 10: 98. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-10-98. PMC 2779188. PMID 19852851.

- Mosbruger TL, Duggal P, Goedert JJ, Kirk GD, Hoots WK, Tobler LH, et al. (May 2010). "Large-scale candidate gene analysis of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 201 (9): 1371–80. doi:10.1086/651606. PMC 2853721. PMID 20331378.

- Bugeon L, Dallman MJ (October 2000). "Costimulation of T cells". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 162 (4 Pt 2): S164-8. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.162.supplement_3.15tac5. PMID 11029388.

- Pan XM, Gao LB, Liang WB, Liu Y, Zhu Y, Tang M, et al. (July 2010). "CD86 +1057 G/A polymorphism and the risk of colorectal cancer". DNA and Cell Biology. 29 (7): 381–6. doi:10.1089/dna.2009.1003. PMID 20380573.

- Dalla-Costa R, Pincerati MR, Beltrame MH, Malheiros D, Petzl-Erler ML (August 2010). "Polymorphisms in the 2q33 and 3q21 chromosome regions including T-cell coreceptor and ligand genes may influence susceptibility to pemphigus foliaceus". Human Immunology. 71 (8): 809–17. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2010.04.001. PMID 20433886.

- Talmud PJ, Drenos F, Shah S, Shah T, Palmen J, Verzilli C, et al. (November 2009). "Gene-centric association signals for lipids and apolipoproteins identified via the HumanCVD BeadChip". American Journal of Human Genetics. 85 (5): 628–42. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.014. PMC 2775832. PMID 19913121.

- Carreño LJ, Pacheco R, Gutierrez MA, Jacobelli S, Kalergis AM (November 2009). "Disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with an altered expression of low-affinity Fc gamma receptors and costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells". Immunology. 128 (3): 334–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03138.x. PMC 2770681. PMID 20067533.

- Koyasu S (April 2003). "The role of PI3K in immune cells". Nature Immunology. 4 (4): 313–9. doi:10.1038/ni0403-313. PMID 12660731. S2CID 9951653.

- Kim SH, Lee JE, Kim SH, Jee YK, Kim YK, Park HS, et al. (December 2009). "Allelic variants of CD40 and CD40L genes interact to promote antibiotic-induced cutaneous allergic reactions". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 39 (12): 1852–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03336.x. PMID 19735272. S2CID 26024387.

- Liu Y, Liang WB, Gao LB, Pan XM, Chen TY, Wang YY, et al. (November 2010). "CTLA4 and CD86 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Human Immunology. 71 (11): 1141–6. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2010.08.007. PMID 20732370.

- Ma XN, Wang X, Yan YY, Yang L, Zhang DL, Sheng X, et al. (June 2010). "Absence of association between CD86 +1057G/A polymorphism and coronary artery disease". DNA and Cell Biology. 29 (6): 325–8. doi:10.1089/dna.2009.0987. PMID 20230296.

- Ishizaki Y, Yukaya N, Kusuhara K, Kira R, Torisu H, Ihara K, et al. (April 2010). "PD1 as a common candidate susceptibility gene of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis". Human Genetics. 127 (4): 411–9. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0781-z. PMID 20066438. S2CID 12633836.

- Chang TT, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH (2002). "Role of the B7-CD28/CTLA-4 pathway in autoimmune disease". Current Directions in Autoimmunity. 5: 113–30. doi:10.1159/000060550. ISBN 3-8055-7308-1. PMID 11826754.

- Grujic M, Bartholdy C, Remy M, Pinschewer DD, Christensen JP, Thomsen AR (August 2010). "The role of CD80/CD86 in generation and maintenance of functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus". Journal of Immunology. 185 (3): 1730–43. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903894. PMID 20601595.

- Quaranta MG, Mattioli B, Giordani L, Viora M (November 2006). "The immunoregulatory effects of HIV-1 Nef on dendritic cells and the pathogenesis of AIDS". FASEB Journal. 20 (13): 2198–208. doi:10.1096/fj.06-6260rev. PMID 17077296. S2CID 3111709.

- Schuurhof A, Bont L, Siezen CL, Hodemaekers H, van Houwelingen HC, Kimman TG, et al. (June 2010). "Interleukin-9 polymorphism in infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection: an opposite effect in boys and girls". Pediatric Pulmonology. 45 (6): 608–13. doi:10.1002/ppul.21229. PMID 20503287. S2CID 24678182.

- Bailey SD, Xie C, Do R, Montpetit A, Diaz R, Mohan V, et al. (October 2010). "Variation at the NFATC2 locus increases the risk of thiazolidinedione-induced edema in the Diabetes REduction Assessment with ramipril and rosiglitazone Medication (DREAM) study". Diabetes Care. 33 (10): 2250–3. doi:10.2337/dc10-0452. PMC 2945168. PMID 20628086.

- Radziewicz H, Ibegbu CC, Hon H, Bédard N, Bruneau J, Workowski KA, et al. (March 2010). "Transient CD86 expression on hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells in acute infection is linked to sufficient IL-2 signaling". Journal of Immunology. 184 (5): 2410–22. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902994. PMC 2924663. PMID 20100932.

이 기사는 공공영역에 있는 미국 국립 의학 도서관의 텍스트를 통합하고 있다.