시진핑

Xi Jinping시진핑 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

习近平 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2023년 시진핑 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 중국 공산당 총서기 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 가임직 2012년 11월 15일 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 앞에 | 후진타오 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 중화인민공화국 제7대 총통 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 가임직 2013년 3월 14일 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 프리미어 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 부통령 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 앞에 | 후진타오 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 중앙군사위원회 위원장 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

가임직

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 부관 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 앞에 | 후진타오 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 중국 공산당 서기국 제1서기 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 재직중 2007년 10월 22일 ~ 2012년 11월 15일 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 총무원장 | 후진타오 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 앞에 | 쩡칭훙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 성공자 | 류윈산 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 중화인민공화국 제8부주석 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 재직중 2008년 3월 15일 ~ 2013년 3월 14일 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 대통령 | 후진타오 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 앞에 | 쩡칭훙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 성공자 | 리위안차오 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 인적사항 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 태어난 | 1953년 6월 15일 중국 베이징 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 정당 | 중국 공산당 (1974년 이후) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 배우자 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 아이들. | 시밍제 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 부모님 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 친척들. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 사는곳 | 중난하이 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 모교 | 칭화대학 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 서명 |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 웹사이트 | www.gov.cn (중국어로) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 한자이름 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 중국어 간체 | 习近平 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 번체 중국어 | 習近平 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

중앙기관회원권 선도 그룹 및 위원회

기타 사무실 개최

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

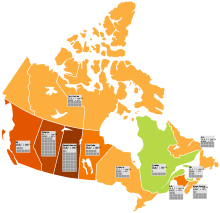

시진핑 (중국어: 习近平어; pinyin), ɕǐ어: ì어.p ʰǐŋ](, 1953년 6월 15일 ~ )는 중화인민공화국의 정치인으로, 2012년부터 중국 공산당 총서기 겸 중앙군사위원회 주석을 역임하고 있다.시 주석은 또한 2013년부터 중화인민공화국 주석을 역임하고 있습니다.그는 중국 지도층 5세대에 속합니다.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| 정책과 이론

주요사건 외교활동

| ||

| ||

중국 공산당의 노장 시진핑의 아들인 시진핑은 문화대혁명 때 아버지의 숙청으로 10대 때 옌촨 현 시골로 망명했습니다.산시성 량자허(梁家河) 마을의 야오동( ya洞)에서 살다가 몇 번의 실패 끝에 중국 공산당에 입당해 지방 당서기로 일했습니다.칭화대에서 노동자-농민-군인으로 화학공학을 공부한 후, 시진핑은 중국의 해안 지방에서 정치적으로 계급을 뛰어넘었습니다.시 주석은 1999년부터 2002년까지 푸젠성의 주지사를 지냈고, 2002년부터 2007년까지 저장성의 주지사와 당서기를 지냈습니다.상하이시 당서기 천량위가 해임된 후 시 주석은 2007년 잠시 그의 후임으로 자리를 옮겼습니다.이후 같은 해 중국공산당 정치국 상무위원회(PSC)에 입당해 2007년 10월 중앙서기처 제1서기를 역임했습니다.2008년, 그는 후진타오의 후계자로 가장 중요한 지도자로 지명되었고, 이를 위해 시 주석은 중국공산당의 부주석과 중국공산당의 부주석으로 임명되었습니다.그는 2016년 중국 공산당으로부터 공식적으로 리더십 핵심 칭호를 받았습니다.

시 주석은 중국 공산당 창당 후 처음 태어난 중국 공산당 총서기입니다.권력을 잡은 이후, 시 주석은 당의 기강을 강화하고 내부 통합을 위한 광범위한 조치들을 내놓았습니다.그의 반부패 운동은 전 PSC 위원인 저우융캉을 포함한 현직 및 은퇴한 중국 공산당 간부들의 몰락으로 이어졌습니다.그는 또한 특히 중국의 대미 관계, 남중국해 9단선, 중-인도 국경 분쟁, 대만의 정치적 지위와 관련하여 보다 적극적인 외교 정책을 제정하거나 추진해 왔습니다.그는 일대일로를 통해 중국의 아프리카와 유라시아 영향력을 확대하려고 노력했습니다.시 주석은 국영기업(SOE)에 대한 지원을 확대하고, 첨단 군-민 융합, 표적 빈곤 완화 프로그램을 감독하며, 부동산 부문의 개혁을 시도했습니다.그는 또한 평등을 높이기 위해 명시된 목표로 설계된 일련의 정책인 "공동 번영"을 추진했으며 2021년 기술 및 과외 부문에 대한 광범위한 단속 및 주요 규제를 정당화하기 위해 이 용어를 사용했습니다.시 주석은 2015년 마잉주(馬英九) 대만 총통을 만난 적이 있는데, 이는 2016년 민진당(民進黨)의 차이잉원( ts英文) 후보가 대선에서 승리한 뒤 관계가 악화된 것입니다.그는 2020년 1월부터 2022년 12월까지 중국 본토의 코로나19 범유행에 제로 코로나 접근법으로 대응했고, 이후 완화 전략으로 전환했습니다.시 주석은 또한 홍콩의 국가보안법 통과를 감독하여 홍콩의 정치적 반대, 특히 민주화 운동가들을 탄압했습니다.

정치 및 학계 관측통들에 의해 자주 권위주의적인 지도자로 묘사되는 시 주석의 재임 기간에는 검열과 대량 감시의 증가, 신장 위구르인 백만 명의 구금(일부 관측통들은 이를 집단 학살의 일부로 묘사함), 시 주석을 중심으로 전개되는 인격 숭배,그리고 2018년 대통령 임기 제한을 없앴습니다.시진핑 사상으로 알려진 시 주석의 정치 사상과 원칙은 당과 국가 헌법에 편입됐고, 국가 안보의 중요성과 국가에 대한 중국 공산당 지도력의 필요성을 강조했습니다.시 주석은 중국 공산당 5세대 지도부의 중심 인물로 국가안전위원회 위원장과 경제·사회 개혁, 군사 구조조정과 현대화, 인터넷 등 여러 직책을 맡으며 기관 권력을 중앙집권화했습니다.그와 중국 공산당 중앙위원회는 2021년 11월 마오쩌둥, 덩샤오핑에 이어 세 번째로 '역사적 결의'를 통과시켰습니다.2022년 10월, 시 주석은 마오쩌둥에 이어 두 번째로 중국 공산당 총서기로 세 번째 임기를 확보했고, 2023년 3월에는 국가주석으로 세 번째 임기를 위해 재선되었습니다.

초기의 삶과 교육

시진핑은 1953년 6월 15일 베이징에서 시진핑과 그의 두 번째 부인 치신의 [2]셋째 아이로 태어났습니다.1949년 중국 공산당 창당 이후 시 주석의 아버지는 당 선전부장, 부총리, 전국인민대표대회 부위원장 등 일련의 직책을 맡았습니다.[3]시 주석에게는 1949년생인 차오차오와 1952년생인 안난(안난, 安安)이라는 두 명의 누나가 있었습니다.시 주석의 아버지는 산시성 푸핑현 출신으로, 시 주석은 허난성 덩저우에 있는 시잉에서 온 그의 부계 혈통을 더 추적할 수 있습니다.[6][unreliable source?]

시진핑은 1960년대에 베이징 베이이 학교를 다녔고,[7][8] 그 후 베이징 25호 학교를 다녔습니다.[9]그는 같은 구에 있는 베이징 101호 학교를 다녔던 류허와 친구가 되었고, 류허는 후에 중국의 부총리가 되었고, 시 주석이 중국의 가장 중요한 지도자가 된 후 그의 측근이 되었습니다.[10][11]그가 10살이 되던 1963년, 그의 아버지는 중국공산당에서 숙청되어 허난성 뤄양시의 공장으로 보내졌습니다.[12]1966년 5월, 문화대혁명은 학생들이 선생님들을 비난하고 싸우도록 모든 중등 수업이 중단되었을 때 시 주석의 중등 교육을 중단시켰습니다.학생 무장세력이 시 주석 가족의 집을 수색했고 시 주석의 여동생 중 한 명인 시허핑은 압력에 자살했습니다.[13]

나중에, 그의 어머니는 그의 아버지가 혁명의 적으로 군중 앞에서 퍼레이드를 했기 때문에 공개적으로 그를 비난할 수 밖에 없었습니다.그의 아버지는 후에 시진핑이 15살이었던 1968년에 투옥되었습니다.그의 아버지의 보호 없이, 시진핑은 1969년에 산시성 옌안시 옌안현 원안이시 량자허 마을에서 마오쩌둥의 시골로의 압송 운동으로 일하도록 보내졌습니다.[14]그는 양자허의 당서기로 일했고, 그곳에서 동굴집에 살았습니다.[15]그를 알고 있던 사람들에 의하면, 이 경험이 그로 하여금 시골의 가난한 사람들과 친밀감을 느끼게 했다고 합니다.[16]시골 생활을 견디지 못하고 몇 달 후, 그는 베이징으로 도망쳤습니다.시골에서 탈영병 단속을 하던 중 체포되어 도랑을 파는 작업 캠프로 보내졌지만, 이후 마을로 돌아갔습니다.그리고 나서 그는 그곳에서 총 7년을 보냈습니다.[17][18]

그의 초기 가족의 불행과 고통은 시진핑의 정치관을 굳혔습니다.2000년 인터뷰에서 그는 "권력과 거의 접촉하지 않는 사람들, 권력과는 거리가 먼 사람들은 항상 이런 것들을 신비롭고 참신하게 봅니다.하지만 제가 보는 것은 단지 표면적인 것들만이 아닙니다. 힘, 꽃, 영광, 박수.황소 우리와 사람들이 어떻게 뜨겁고 차갑게 불 수 있는지 봅니다.저는 정치를 더 깊이 이해합니다.""황소"(황소)는 문화 혁명 당시 [16]홍위병의 수용소를 지칭하는 말이었습니다.

7번의 거절 끝에, 시진핑은 1971년 지방 관리와 친구가 된 후 8번째 시도로 중국 공산당 청년 연맹에 가입했습니다.[8]그는 1972년 저우언라이 총리가 지시한 가족 상봉 때문에 아버지와 재회했습니다.[13]1973년부터 그는 중국 공산당에 10번이나 가입을 신청했고 1974년 열 번째 시도에서 마침내 받아들여졌습니다.[19][20][21]1975년부터 1979년까지 시 주석은 베이징에서 노동자-농민-군인 학생으로 칭화대학교에서 화학공학을 공부했습니다.그곳의 공학 전공자들은 그들의 시간의 약 15%를 마르크스주의를 공부하는데 보냈습니다.–레닌주의–마오주의와 그들의 5%의 시간은 농장 일을 하고 "인민해방군으로부터 배우는 것"입니다.[22]

초기 정치인 경력

1979년부터 1982년까지 시진핑은 그의 아버지의 전 부하인 겅뱌오의 비서로 일했고, 당시 부총리이자 중국 공산당 서기장이었습니다.[8] 1982년 그는 허베이성 정딩현에 정딩현의 당 부비서로 파견되었습니다.그는 1983년에 비서로 승진하여 군의 최고 관리가 되었습니다.[23]시 주석은 이후 지역 정치 경력 동안 4개 성(省)에서 근무했습니다.허베이(1982~1985), 푸젠(1985~2002), 저장(2002~2007), 상하이([24]2007).시 주석은 푸저우시 당위원회에서 직책을 맡았고 1990년 푸저우시 당학교의 주석이 되었습니다.1997년, 그는 중국 공산당 제15기 중앙위원회의 대체 위원으로 임명되었습니다.그러나 15차 당 대회에서 선출된 151명의 중앙위원회 대체 위원 중 시진핑은 가장 낮은 찬성표를 받아, 표면적으로는 왕자의 지위 때문에 위원 순위에서 꼴찌를 기록했습니다.[b][25]

1998년부터 2002년까지 시 주석은 칭화대에서 마르크스주의 이론과 사상교육을 [26]공부했고 2002년 법학과 사상학 박사 학위를 받고 졸업했습니다.[27]1999년에 푸젠성 부성장으로 승진했고, 1년 후에 총독이 되었습니다.푸젠에서 시 주석은 대만으로부터 투자를 유치하고 지방 경제의 민간 부문을 강화하기 위해 노력했습니다.[28]2000년 2월, 그와 천밍이 당시 성 당서기는 장쩌민 총서기, 주룽지 총리, 후진타오 부주석, 웨이젠싱 기율검사 서기 등 PSC의 최고위급 인사들 앞에 불려가 원화 스캔들의 양상을 설명했습니다.[29]

2002년에 시 주석은 푸젠성을 떠나 인접한 저장성에서 주요 정치적 위치를 차지했습니다.도지사 권한대행을 맡은 지 몇 달 만에 도당위원회 간사를 맡게 된 그는 생애 처음으로 도당 최고위직을 차지했습니다.2002년, 그는 제16기 중앙위원회의 정위원으로 선출되어 국가 무대에 오른 것을 알렸습니다.저장성에 있는 동안 시 주석은 연평균 14%의 성장률을 보고했습니다.[30]그의 저장에서의 경력은 부패한 관리들에 대한 강경하고 직설적인 태도로 특징지어졌습니다.이것은 그에게 국가 언론에서 이름을 날렸고 중국의 최고 지도자들의 관심을 끌었습니다.[31]2004년부터 2007년 사이에 리창은 저장성 당위원회 서기장을 통해 시 주석의 비서실장을 맡았고, 두 사람은 긴밀한 관계를 구축했습니다.[32]

2006년 9월 사회보장기금 스캔들로 천량위 상하이 당서기가 해임된 후, 시 주석은 2007년 3월 상하이로 전보되었고, 그곳에서 7개월 동안 당서기를 지냈습니다.[33][34]상하이에서 시 주석은 논란을 피하고 당의 기강을 엄격하게 지키는 것으로 유명했습니다.예를 들어, 상하이 행정가들은 그가 그의 후계자인 저장성 당서기 자오훙주에게 그의 일을 물려주기 위해 상하이와 항저우를 왕복하는 특별 열차를 마련하여 그의 환심을 사려 했습니다.그러나 시 주석은 특별열차는 '국가 지도자'에게만 예약할 수 있도록 규정한 느슨하게 시행된 당규를 이유로 열차 탑승을 거부한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[35]상하이에 있는 동안 그는 지역 당 조직의 통일성을 유지하기 위해 노력했습니다.그는 많은 지방 관리들이 천량위 부패 사건에 연루되었을 것으로 생각됨에도 불구하고, 그의 정부 기간 동안 '숙청'은 없을 것이라고 약속했습니다.[36]대부분의 문제에 있어서 시 주석은 중앙 지도부의 노선을 대체로 그대로 답습했습니다.[37]

권좌에 오르다

시 주석은 2007년 10월 제17차 당 대회에서 9인 체제로 선출되었습니다.그는 리커창보다 서열이 높았는데, 이것은 그가 후진타오의 뒤를 이어 중국의 차기 지도자가 될 것이라는 암시입니다.이와 함께 시 주석은 중국 공산당 중앙서기처 제1서기도 맡았습니다.이 평가는 2008년 3월 제11차 전국인민대표대회(전인대)에서 시 주석이 중국공산당 부주석으로 선출되면서 더욱 뒷받침됐습니다.[38]그의 부상 이후, 시진핑은 다양한 포트폴리오를 보유했습니다.그는 2008년 베이징 하계 올림픽의 종합적인 준비를 담당하고 홍콩과 마카오 문제에 있어서 중앙 정부의 주요 인물이었습니다.또한, 그는 중국공산당 중앙당의 간부 양성 및 사상 교육 부서인 중앙당 학교의 신임 총장이 되었습니다.시 주석은 2008년 쓰촨성 대지진이 발생하자 산시성과 간쑤성의 재난지역을 방문했습니다.그는 2008년 6월 17일부터 25일까지 북한, 몽골, 사우디아라비아, 카타르, 예멘을 방문하며 부통령으로서 첫 해외 순방을 가졌습니다.[39]올림픽이 끝난 후, 시 주석은 중화인민공화국 건국 60주년 기념행사 준비를 위한 위원장직을 맡았습니다.보도에 따르면 그는 또한 2009년 일련의 정치적으로 민감한 기념일 동안 사회 안정을 보장하는 임무를 맡은 6521 프로젝트라고 불리는 최고위급 중국 공산당 위원회의 지휘봉을 잡았습니다.[40]

가장 중요한 지도자가 될 것으로 보이는 시 주석의 후계자 자리는 당시 충칭시 당서기였던 보시라이의 급부상으로 위협을 받았습니다.보 서기는 18차 당 대회에서 PSC에 합류할 것으로 예상되었으며, 대부분의 사람들은 그가 결국 시 주석을 교체하는 데 자신을 조종하려고 노력할 것이라고 예상했습니다.[41]보의 충칭 정책은 중국 전역에서 모방에 영감을 주었고 2010년 시 주석의 충칭 방문 동안 시 주석 자신으로부터 찬사를 받았습니다.시진핑이 가장 중요한 지도자가 된 후에 시 주석의 칭찬에 대한 기록은 지워졌습니다.보시라이의 몰락은 왕리쥔 사건과 함께 올 것이고, 이것은 시 주석이 도전자 없이 권력을 잡을 수 있는 문을 열었습니다.[42]

시 주석은 초기 중국 공산당 혁명가들의 후손인 준 정치인 집단인 프린스링스의 가장 성공적인 구성원 중 한 명으로 여겨집니다.리콴유 전 싱가포르 총리는 시 주석에 대한 질문에 "많은 시련과 고난을 겪은 사려 깊은 사람"이라고 느꼈다고 말했습니다.[43]리는 또한 다음과 같이 말했습니다: "나는 그를 넬슨 만델라의 부류에 넣을 것입니다.자신의 개인적인 불행이나 고통을 허락하지 않는 엄청난 정서적 안정감을 가진 사람이 판단력에 영향을 미칩니다.다시 말해서, 그는 인상적입니다."[44]헨리 폴슨 전 미국 재무장관은 시진핑을 "목표선을 넘는 방법을 아는 사람"이라고 묘사했습니다.[45]케빈 러드 호주 총리는 시 주석이 "그의 사람이 되기에 충분한 개혁주의자, 정당, 군사적 배경을 가지고 있다"고 말했습니다.[46]

부총재로서의 출장

2009년 2월 시진핑은 부통령 자격으로 멕시코,[47] 자메이카,[48] 콜롬비아,[49] 베네수엘라,[50] 브라질,[51] 몰타를 방문하는 중남미 순방에 나섰고 이후 중국으로 돌아왔습니다.[52]2009년 2월 11일 멕시코를 방문한 시 주석은 화교 단체 앞에서 연설을 하고 국제 금융 위기 동안 중국이 기여한 바를 설명하면서 "13억 인구가 굶주리는 것을 방지하기 위해 중국이 만든 인류 전체에 대한 가장 큰 기여"라고 말했습니다.[c]그는 계속해서 이렇게 말했습니다: "배가 꽉 찬 지루한 외국인들이 있는데, 그들은 우리를 손가락질하는 것보다 더 할 일이 없는 사람들입니다.첫째, 중국은 혁명을 수출하지 않습니다. 둘째, 중국은 기아와 빈곤을 수출하지 않습니다. 셋째, 중국은 와서 여러분을 두통하게 하지 않습니다.할 말이 더 있습니까?"[d][53]이 이야기는 일부 지역 방송국에서 보도되었습니다.이 소식이 전해지면서 중국 인터넷 포럼에서는 토론이 쇄도했고, 시 주석의 발언에 중국 외교부가 허를 찔린 것으로 알려졌는데, 실제 영상은 일부 동행한 홍콩 기자들이 촬영해 홍콩 TV를 통해 방영됐고, 이후 각종 인터넷 동영상 사이트에 등장했습니다.[54]

유럽연합에서 시 주석은 2009년 10월 7일부터 21일까지 벨기에, 독일, 불가리아, 헝가리, 루마니아를 방문했습니다.[55]그는 2009년 12월 14일부터 22일까지 아시아 여행으로 일본, 한국, 캄보디아, 미얀마를 방문했습니다.[56]그는 이후 2012년 2월 미국, 아일랜드, 터키를 방문했습니다.이번 방문에는 버락[57] 오바마 당시 미국 대통령과 백악관에서 조 바이든 부통령을 만나는 것이 포함되었고, 캘리포니아와 아이오와에 들렀는데, 그는 1985년 허베이성 관리로서 그를 방문했을 때 이전에 그를 초청했던 가족들을 만났습니다.[58]

최고위직 입직

당 지도부에 오르기 몇 달 전, 시 주석은 공식 언론 보도에서 사라졌고 2012년 9월 1일부터 몇 주 동안 외국 관리들과의 회담을 취소하여 소문이 났습니다.[8]그 후 그는 9월 15일에 다시 나타났습니다.[59]2012년 11월 15일, 시 주석은 제18기 중앙위원회에서 중국 공산당 총서기와 중국 공산당 주석직에 선출되었습니다.이것은 그를 비공식적으로 가장 중요한 지도자이자 중국공산당 창립 후 태어난 첫 번째 지도자로 만들었습니다.다음날 시 주석은 첫 공식 석상에서 PSC의 새로운 라인업을 무대 위로 이끌었습니다.[60]PSC는 9명에서 7명으로 줄었고, 시 주석과 리커창만 자리를 지켰고, 나머지 5명은 새로 왔습니다.[61][62][63]중국 지도자들의 일반적인 관행에서 확연히 벗어난 시 주석의 첫 총서기 연설은 명확하게 표현되었고 정치적 구호나 전임자들에 대한 언급은 없었습니다.[64]시 주석은 평범한 사람들의 열망을 언급하며 "우리 국민은...더 나은 교육, 더 안정적인 직업, 더 나은 수입, 더 신뢰할 수 있는 사회 보장, 더 높은 수준의 의료, 더 나은 생활 조건, 더 아름다운 환경을 기대합니다." 시진핑은 또한 최고 수준의 부패와 씨름하겠다고 맹세했습니다.그것이 중국 공산당의 생존을 위협할 것임을 암시했습니다. 그는 광범위한 경제 개혁에 관해 말을 아꼈습니다.[65]

2012년 12월, 시 주석은 당 지도부에 오른 이후 베이징을 벗어난 첫 번째 여행으로 광둥성을 방문했습니다.이번 순방의 가장 큰 주제는 추가적인 경제 개혁과 강화된 군대를 요구하는 것이었습니다.시 주석은 덩샤오핑의 동상을 방문했고 그의 여행은 1989년 천안문 시위와 대학살의 여파로 보수 정당 지도자들이 덩샤오핑의 많은 개혁을 중단시킨 후 중국에서 추가적인 경제 개혁의 원동력을 제공한 1992년 덩샤오핑 자신의 남쪽 여행의 발자취를 따르는 것으로 묘사되었습니다.그의 여행에서, 시진핑은 그의 대표적인 슬로건인 "중국의 꿈"을 지속적으로 언급했습니다."이 꿈은 강한 나라의 꿈이라고 할 수 있습니다.그리고 군대에게 그것은 강한 군대의 꿈입니다"라고 시 주석은 선원들에게 말했습니다.[66]시 주석의 이번 순방은 다방면으로 중국 지도자들의 기행 관행에서 벗어났다는 점에서 의미가 컸습니다.시 주석과 수행원들은 외식 대신 일반 호텔 뷔페를 먹었습니다.그는 리무진 차량이 아니라 동료들과 함께 대형 승합차를 타고 이동했으며, 자신이 이동한 고속도로 일부의 통행을 제한하지 않았습니다.[67]

시 주석은 2013년 3월 14일 베이징에서 열린 제12차 전국인민대표대회 인준 투표에서 주석으로 선출되었습니다.그는 찬성 2,952표, 반대 1표, 기권 3표를 받았습니다.[60]그는 두 번의 임기를 마치고 은퇴한 후진타오를 대신했습니다.[68]2013년 3월 16일, 시 주석은 스리랑카 내전 당시 정부의 학대 행위를 규탄하는 유엔 안전보장이사회의 투표에서 중국-스리랑카 관계에 대한 불간섭을 지지했습니다.[69]3월 17일, 시 주석과 그의 새 장관들은 렁 주석에 대한 지지를 확인하면서 홍콩 행정장관인 렁 주석과 회담을 마련했습니다.[70]당선 몇 시간 만에 시 주석은 버락 오바마 미국 대통령과 전화 통화를 통해 사이버 안보와 북한 문제를 논의했습니다.오바마 대통령은 재무장관과 국무장관인 제이콥 르와 존 F의 방문을 발표했습니다. 케리는 그 다음주에 중국에 갑니다.[71]

리더십

반부패운동

"진실을 말하는 것"은 사물의 본질에 집중하고, 솔직하게 말하고, 진실을 따르는 것을 의미합니다.이것은 진실 추구, 정의 구현, 공익에 대한 헌신, 그리고 정직함이라는 선도적인 관리의 특성을 보여주는 중요한 구현입니다.게다가 진실을 말하는 전제는 진실을 듣는 것이라고 강조했습니다.

시 주석은 18차 당대회에서 권력에 오른 뒤 거의 즉시 부패를 단속하겠다고 공언했습니다.시 주석은 총서기 취임 연설에서 부패 척결이 당에 가장 어려운 도전 중 하나라고 언급했습니다.[74]임기 몇 달 만에 시 주석은 공식적인 당 업무 중 부패와 낭비를 억제하기 위한 규칙을 나열하는 8개 조항의 개요를 설명했습니다. 그것은 당 관리들의 행동에 대한 더 엄격한 규율을 목표로 했습니다.시 주석은 또 "호랑이와 파리", 즉 고위층과 일반 당 지도부를 뿌리 뽑겠다고 공언했습니다.[75]

시 주석은 쉬차이허우 전 CMC 부위원장과 궈복시옹, 저우융캉 전 PSC 위원 겸 안보실장, 링지화 전 후진타오 수석 등을 상대로 소송을 제기했습니다.[76]왕치산 신임 훈육부장과 함께 시 주석 정부는 '중앙파견 감찰반'(中央巡视组)을 구성하는 데 앞장섰습니다.이들은 본질적으로 지방 당 조직의 운영을 보다 깊이 이해하는 것이 주요 임무였으며, 그 과정에서 베이징이 지시하는 당 규율을 집행하는 것도 주요 임무였습니다.업무팀 중 상당수는 고위층을 파악하고 조사를 시작하는 효과도 있었습니다.전국적으로 대대적인 반부패 캠페인이 진행되는 동안 100명이 넘는 도-부 장관급 공무원들이 연루되었습니다.여기에는 전·현직 지방 관리(쑤룽, 바이엔페이, 완칭량), 국영 기업 및 중앙 정부 기관의 주요 인사(송린, 류톈안), 군부의 고위 장성(구준산) 등이 포함되었습니다.2014년 6월, 산시성 정치 조직은 1주일 만에 4명의 관리가 지방 당 조직의 최고위직에서 해임되는 등 파괴되었습니다.캠페인의 첫 2년 동안에만 20만 명이 넘는 하위직 공무원들이 경고, 벌금 및 강등을 받았습니다.[77]

이 캠페인은 PSC 구성원을 포함하여 현직 및 은퇴한 중국 공산당 간부들의 몰락으로 이어졌습니다.[78] 시진핑의 반부패 캠페인은 이코노미스트와 같은 비평가들에 의해 잠재적인 반대자들을 제거하고 권력을 공고히 하기 위한 정치적 도구로 여겨집니다.[79][80]시 주석이 신설한 반부패기구 국가감독위원회는 대법원보다 순위가 높았습니다.국제앰네스티 동아시아 국장은 "수천만 명의 사람들을 법 위에 있는 비밀스럽고 사실상 설명할 수 없는 시스템의 지배하에 두는" 인권에 대한 체계적인 위협"이라고 설명했습니다.[81][82]

시 주석은 중국 공산당의 최고 내부통제기관인 중앙기율검사위원회(CCDI)의 대대적인 개혁을 감독해 왔습니다.[83]그와 왕치산 CCDI 사무총장은 CCP의 일상적인 운영으로부터 CCDI의 독립성을 더욱 제도화하여, 진정한 통제기구로서의 기능을 향상시켰습니다.[83]월스트리트저널(WSJ)에 따르면, 차관급 이상 관리들에게 반부패 처벌을 내리는 것은 시 주석의 승인이 필요합니다.[84]월스트리트저널의 또 다른 기사는 그가 정치적 경쟁자를 무력화하고 싶을 때, 그는 감찰관들에게 수백 페이지의 증거를 준비하도록 요구한다고 말했습니다.기사는 또한 그가 때때로 고위 정치인의 측근들에 대한 조사를 승인하여 그들을 자신의 피보호자로 대체하고 정치적 경쟁자들을 정치적 기반으로부터 분리하기 위해 덜 중요한 위치에 놓이게 한다고 말했습니다.보도에 따르면, 이러한 전술들은 시 주석의 가까운 친구인 왕치산에 대해서도 사용되었습니다.[85]

역사학자이자 죄학자인 왕궁우에 따르면, 시진핑은 만연한 부패에 직면한 정당을 물려받았다고 합니다.[86][87]시 주석은 중국 공산당 고위층의 부패 규모가 당과 국가 모두를 붕괴의 위험에 빠뜨렸다고 믿었습니다.[86]왕 부장은 시 주석은 중국 공산당만이 중국을 통치할 수 있으며, 당의 붕괴는 중국 국민들에게 재앙이 될 것이라는 믿음을 가지고 있다고 덧붙였습니다.시 주석과 새로운 세대 지도자들은 정부 고위층의 부패를 없애기 위한 반부패 캠페인을 시작함으로써 대응했습니다.[86]

검열

시 주석이 중국 공산당 총서기에 오른 이후 인터넷 검열 등 검열이 대폭 강화됐습니다.[88][89]시 주석은 2018년 4월 20일과 21일에 열린 2018 중국 사이버 공간 거버넌스 회의에서 "해킹, 통신 사기, 시민 사생활 침해를 포함한 형사 범죄를 엄중히 단속하겠다"고 약속했습니다.[90]시 주석은 중국 관영 매체를 방문한 자리에서 "당과 관영 매체는 반드시 당의 성씨를 지녀야 한다"(党和政府主办的媒体必须姓党)며 관영 매체는 "당의 뜻을 구체화해 당의 권위를 지켜야 한다"고 말했습니다.

그의 행정부는 중국에서 부과된 더 많은 인터넷 규제를 감독했으며, 이전 행정부보다 연설에 대해 "전반적으로 더 엄격하다"고 묘사됩니다.[92]시 주석은 구글과 페이스북 등 중국 내부의 인터넷 사용을 통제하기 위해 인터넷 주권 개념으로 [93]자국 내 인터넷 검열을 주장하며 매우 강력한 입장을 취해왔습니다.[94][95]위키백과에 대한 검열 또한 엄격해졌으며, 2019년 4월 중국에서 모든 버전의 위키백과가 차단되었습니다.[96]마찬가지로 웨이보 사용자들의 상황은 개인 게시물이 삭제되거나 최악의 경우 계정이 삭제될 것이라는 두려움에서 체포될 것이라는 두려움으로의 변화로 설명되었습니다.[97]

2013년 9월에 제정된 법률은 "명예훼손"으로 간주되는 콘텐츠를 500배 이상 공유한 블로거에게 징역 3년을 선고했습니다.[98]주 인터넷 정보부는 한 세미나에 영향력 있는 블로거들을 불러 정치, 중국 공산당에 대해 글을 쓰거나 공식적인 이야기와 모순되는 발언을 하지 말라고 지시했습니다.많은 블로거들이 논쟁적인 주제에 대한 글을 쓰지 않았고, 웨이보는 쇠퇴했고, 독자층의 대부분이 위챗 사용자들에게 매우 제한된 소셜 서클에 말을 거는 쪽으로 이동했습니다.[98]2017년 중국의 통신사들은 정부로부터 2018년 2월까지 개인의 가상 사설망(VPN) 사용을 차단하라는 지시를 받았습니다.[99]

시진핑은 중국 공산당의 공식 노선에 도전하는 역사적 관점을 의미하는 "역사적 허무주의"에 반대하는 목소리를 냈습니다.[100]시 주석은 소련 붕괴의 원인 중 하나가 역사적 허무주의라고 말했습니다.[101]중국 사이버 공간 관리국(CAC)은 사람들이 역사적 허무주의 행위를 보고하도록 전화 핫라인을 구축했고, Toutiao와 Douyin은 사용자에게 역사적 허무주의 사례를 보고하도록 촉구했습니다.[102]2021년 5월, CAC는 역사적 허무주의를 위해 2백만 개의 온라인 게시물을 삭제했다고 보고했습니다.[103]

권력의 공고화

정치 관측통들은 시진핑을 마오쩌둥 이후 가장 강력한 중국 지도자, 특히 2018년 대통령 연임 제한이 종료된 이후로 칭했습니다.[104][105][106][107]시 주석은 마오 이후 전임자들의 집단적인 리더십 관행에서 눈에 띄게 벗어났습니다.그는 권력을 중앙집권화하고 정부 관료주의를 전복시키기 위해 자신을 중심으로 실무그룹을 만들어 새 정부의 확실한 중심 인물이 되었습니다.[108]2013년부터 시 주석이 이끄는 중국공산당은 일련의 중앙선도그룹, 즉 초부처 운영위원회를 만들었고, 결정을 내릴 때 기존 기관을 우회하고 표면적으로 정책 결정을 더 효율적인 과정으로 만들기 위해 고안되었습니다.가장 눈에 띄는 새 기구는 '종합심화개혁 중앙선도그룹'입니다.경제 구조조정과 사회개혁을 광범위하게 관할하고 있으며, 국무원과 국무원 총리가 이전에 가지고 있던 권력의 일부를 대체했다는 평가를 받고 있습니다.[109]

시 주석은 또한 사이버 보안과 인터넷 정책을 담당하는 인터넷 보안과 정보화를 위한 중앙 주도 그룹의 지도자가 되었습니다.2013년에 열린 제3차 국민투표에서도 시 주석이 위원장을 맡고 있는 또 다른 기관인 중국공산당 국가안전위원회가 창설되었는데, 이 위원회는 시 주석이 국가 안보 문제를 통합하는 데 도움이 될 것이라고 논평가들은 말했습니다.[110][111]적어도 한 명의 정치학자의 견해로는, 시 주석은 "해안, 푸젠성과 상하이 그리고 저장성에 주둔하면서 만났던 간부들로 자신을 포위했습니다."[112]베이징에 대한 통제는 중국 지도자들에게 매우 중요한 것으로 여겨집니다; 시진핑은 수도를 관리하기 위해 위에서 언급한 간부들 중 한 명인 차이치를 선택했습니다.[113]시 주석은 또한 리커창 총리의 권한을 희석시켜 일반적으로 총리의 영역으로 여겨져 온 경제에 대한 권한을 장악한 것으로 여겨졌습니다.[114][115]

집권 이후 시 주석은 당의 공산당 청년동맹(CYLC)을 통해 부상한 중국 공산당 간부들로 한때 지배적이었던 '투안파이', 일명 청년동맹파의 영향력을 심각하게 희석시켰다는 다양한 관측이 나오고 있습니다.[116]그는 CYLC의 간부들이 과학, 문학, 예술, 일, 삶에 대해 이야기할 수 없다고 비판했습니다.그들이 할 수 있는 것은 그저 낡은 관료적이고 틀에 박힌 이야기를 반복하는 것뿐입니다."[117]예산도 삭감되어 2012년 약 7억 위안(9600만 달러)에서 2021년 2억 6천만 위안(4000만 달러)으로 감소한 반면, 같은 기간 회원 수는 9천만 명에서 7400만 명으로 감소했습니다.[116]그는 또 중국공산주의청년동맹 중앙학교를 폐쇄해 중국사회과학원과 합병했고, 2017년 중국공산주의청년동맹 제1서기 진이즈를 사실상 좌천시켰습니다.[118]

2018년 3월, 전국인민대표대회(NPC)는 대통령과 부통령의 임기 제한 철폐, 국가감독위원회 창설, 중국 공산당의 중심 역할 강화 등을 포함한 일련의 헌법 개정안을 통과시켰습니다.[119][120]2018년 3월 17일, 중국 입법부는 임기 제한 없이 시 주석을 재임명했고, 왕치산은 부주석으로 임명되었습니다.[121][122]다음 날, 리커창은 총리로 재임명되었고, 시진핑의 오랜 동맹국인 쉬치량과 장유샤는 중앙군사위원회의 부위원장으로 선출되었습니다.[123] 외무장관 왕이는 국무위원으로 승진되었고, 장군 웨이펑허는 국방부 장관으로 임명되었습니다.[124]파이낸셜 타임즈에 따르면, 시 주석은 중국 관리들과 외국 고위 관리들과의 회담에서 개헌에 대한 자신의 견해를 밝혔습니다.시 주석은 이번 결정에 대해 임기 제한이 없는 중국 공산당 총서기와 중국 공산당 위원장이라는 두 자리를 더 강력하게 정렬할 필요가 있다고 설명했습니다.다만 시 주석은 3선 이상 당 총서기와 CMC 위원장, 국가주석 등을 맡을 의향이 있는지는 밝히지 않았습니다.[125]

중국 공산당은 2021년 11월 제6차 전체회의에서 당의 역사를 평가하는 일종의 문서인 역사 결의안을 채택했습니다.이것은 마오쩌둥과 덩샤오핑이 채택한 것에 이어 세 번째이며, [126][127]이 문서는 처음으로 시 주석을 시진핑[128] 사상의 "주요 혁신가"로 인정하고 시 주석의 지도력을 "중국 국가의 위대한 부흥의 열쇠"로 선언했습니다.[129]다른 역사적 결의안들과 비교해 볼 때, 시진핑의 결의안은 중국 공산당이 역사를 평가하는 방식에 큰 변화를 예고하지 않았습니다.[130]역사적 결의에 수반하기 위해, 중국 공산당은 "두 개의 설립과 두 개의 안전장치"라는 용어를 홍보했고, 중국 공산당은 시 주석의 핵심적인 지위를 보호하고 단결할 것을 요구했습니다.[131]2022년, 시진핑은 그의 가까운 동맹인 왕샤오훙을 공안부 장관으로 임명했고, 그에게 보안 기관에 대한 더 많은 통제권을 주었습니다.[132]

2022년 10월 16일에서 22일 사이에 열린 제20차 중국 공산당 전국대표대회는 중국 공산당 헌법 개정과 시 주석의 3선 총서기 및 CMC 위원장 재선을 감독해 왔으며, 전체적인 결과는 시 주석의 권력을 더욱 강화하는 것입니다.[133]새로 개정된 중국 공산당 헌법에는 두 가지 안전장치라는 용어가 포함되어 시 주석의 권력을 강화했습니다.[134]공동번영, '중국식 근대화', '전과정 인민민주주의' 등 시 주석이 추진한 개념도 포함됐습니다.[135]비록 덩샤오핑이 비공식적으로 더 오랜 기간 동안 나라를 통치했지만, 시진핑의 재선으로 그는 마오쩌둥 이후 3선에 선출된 첫 번째 당 지도자가 되었습니다.[136]시 주석은 제14차 전국인민대표대회 개막 기간인 2023년 3월 10일 중국 중앙군사위원회 주석과 위원장에 재선되었습니다.[137]

중국 공산당 대회 직후 선출된 새 정치국 상무위원회는 리커창(李 wang强) 총리와 왕양(王陽) 중국 공산당 중앙위원회 위원장 등 7명 중 4명이 물러나는 등 시 주석 측근 인사들로 거의 채워졌습니다.시진핑의 측근인 리창은 PSC의 2인자가 되었고, 2023년에 총리로 더 승진했습니다.[133][139]차이치, 딩쉐샹, 리시 등 시 주석의 다른 우방들도 PSC에 가입했으며, 각각 중국 공산당 서기국 제1서기, 제1부부장, 중앙기율검사위원회 서기가 되었습니다.[140]시 주석을 제외한 나머지 국가인민위원회 위원은 자오레지와 왕후닝뿐이었지만,[140] 2023년 3월 10일 전국인민대표대회 상무위원회와 중국인민대표대회 상무위원장이 되었습니다.[141][142]로이터통신은 왕양과 리커창이 물러나고 후춘화 부총리가 정치국에서 강등된 것은 툰파이의 전멸을 의미한다고 지적했고,[116] 윌리워랩람은 툰파이나 상하이 파벌의 대표자가 없어 시 주석 자신의 파벌이 완전히 장악했다고 전했습니다.[143]

인격숭배

시[144][145] 주석은 집권 이후 책, 만화, 팝송, 댄스 등으로 자신을 중심으로 인격 형성에 대한 숭배를 해왔습니다.[146]시 주석이 중국 공산당의 지도력 핵심으로 부상한 후, 그는 시 다다(习大大, 삼촌 또는 파파 시)라고 불렸지만, 2016년 4월에 중단되었습니다.시 주석이 출근한 량자허 마을은 중국 공산당 선전과 그의 생애 형성기를 찬양하는 벽화로 꾸며진 '현대판 신사'가 됐습니다.[149]중국 공산당 정치국은 시진핑 링슈(领袖)를 "지도자"를 경건하게 부르는 말로, 이전에는 마오쩌둥과 그의 후계자 화궈펑에게만 주어진 칭호였습니다.그는 때때로 "조종사" (조종사)라고 불리기도 합니다. (조종사) 领航掌舵.2019년 12월 25일, 정치국은 시 주석을 마오쩌둥(毛澤東)만이 가지고 있던 "인민지도자"(人民领袖: ǐ, ù)로 공식 지명했습니다.

경제와 기술

시 주석은 처음에는 시장 개혁주의자로 여겨졌고,[155] 그가 이끄는 18기 중앙위원회 제3차 전원회의는 "시장 세력"이 자원 배분에 "결정적인" 역할을 하기 시작할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[156]이는 국가가 자본 분배에 대한 참여를 점차 줄이고, 잠재적으로 이전에 규제가 심했던 산업의 외국 및 민간 부문 참여자를 유치함으로써 중국의 국유 기업(SOE)을 구조조정하여 더 많은 경쟁을 허용할 것임을 의미했습니다.이 정책은 더 이상 생산적으로 사용되지 않는 자산인 자산을 시장 가격 이하로 구입함으로써 이전의 재구조화로 인해 과도하게 이익을 얻었던 비대해진 주 부문을 해결하는 것을 목표로 했습니다.시 [157]주석은 또한 2013년 8월 경제 개혁의 일환으로 간주된 상하이 자유무역지대를 출범시켰습니다.그러나 2017년까지 시 주석의 경제 개혁 약속은 전문가들에 의해 지연되고 있다고 합니다.[158][155]2015년 중국 주식시장 거품이 터졌고, 이로 인해 시 주석은 이 문제를 해결하기 위해 국가군을 사용하게 되었습니다.[159]2012년부터 2022년까지 중국 상위 상장 기업에서 민간 부문 기업의 시장 가치가 차지하는 비중은 약 10%에서 40%[160] 이상으로 증가했습니다.그는 또한 외국인 직접 투자(FDI) 제한 완화와 주식 및 채권의 국경 간 보유 증가를 감독했습니다.[160]

시 주석은 중국 경제에 대한 국가의 통제를 강화하고, 공기업에 대한 지지의 목소리를 높이는 한편,[161][155] 중국의 민간 부문에 대한 지지의 목소리도 높였습니다.[162]시진핑 체제에서 SOE에 대한 CCP 통제가 증가하는 한편 SOE의 혼합 소유를 늘리는 등 시장 자유화를 위한 일부 제한적인 조치도 취해졌습니다.[163]시 주석 체제에서 정부 기관이 설립하거나 정부 기관을 위해 설립한 민관 투자 펀드인 '정부 지도 펀드'는 정부가 전략적이라고 판단하는 분야에서 일하는 기업에 대한 조기 자금 지원을 위해 9천억 달러 이상을 조달했습니다.[164]시 주석은 국무원을 희생시키면서 중앙 금융 경제 위원회의 역할을 늘렸습니다.[165]그의 행정부는 은행들이 모기지를 쉽게 발행할 수 있도록 했고, 채권 시장에 대한 외국인들의 참여를 늘렸으며, 국가 통화인 위안화의 세계적인 역할을 증대시켜 IMF의 특별인출권 바스켓에 동참할 수 있도록 도왔습니다.[166]2018년 중국 경제 개혁 출범 40주년을 맞아 그는 개혁을 계속하겠다고 약속하면서도 아무도 "중국 국민에게 지시할 수 없다"고 경고했습니다.[167]

시 주석은 또한 개인적으로 "표적 빈곤 완화"를 통해 극빈을 근절하는 것을 핵심 목표로 삼았습니다.[168]2021년 시 주석은 재임 기간 동안 거의 1억 명이 빈곤에서 벗어났다며 극빈에 대한 "완전한 승리"를 선언했지만, 일부 전문가들은 중국의 빈곤 문턱이 세계은행이 설정한 빈곤 문턱보다 상대적으로 낮다고 말했습니다.[169]2020년 리커창 총리는 국가통계국(NBS)을 인용하여 중국은 여전히 월 1000위안(140달러) 미만으로 6억 명이 살고 있다고 말했지만, 이코노미스트지의 기사는 NBS가 사용한 방법론에 결함이 있다며 수치가 합산 소득을 가져갔고, 이를 균등하게 나누었다고 말했습니다.[170]

시진핑 체제에서 중국 경제는 명목 GDP가 2012년 8조 5,300억 달러에서 2021년 17조 7,300억 달러로 두 배 이상 증가한 반면,[171] 중국의 명목 1인당 GDP는 2012년 7.9%[172]에서 2019년 6%로 성장률이 둔화되었지만 2021년 세계 평균을 넘어섰습니다.[173]시 주석은 '팽창성장'보다는 '고품질 성장'의 중요성을 강조해왔습니다.[174]그는 중국이 경제 성장의 질에 초점을 맞출 것이며 시 주석이 "GDP 영웅주의"라고 말하는 모든 비용을 들이는 성장 전략을 포기했다고도 말했습니다.[175]: 22 대신, 시 주석은 환경 보호와 같은 다른 사회적 문제들이 중요하다고 말했습니다.[175]: 22 그의 행정부는 중국이 경제 성장을 하는 동안 발생한 지속 불가능한 부채의 규모를 늦추고 줄이기 위해 부채 탕감 운동을 추구했습니다.[176]중국의 GDP 대비 총 비금융 부문 부채 비율은 코로나19 위기 기간인 2020년까지 사상 최대인 270.9%를 기록했지만, 2021년까지 약 262.5%로 떨어졌다가 2022년 273.2%로 다시 상승했는데, 이는 주로 제로 코로나 정책이 지방 재정에 가하는 압박 때문입니다.[177]

시 주석은 "이중 순환"이라고 불리는 정책을 발표했는데, 이는 대외 무역과 투자에 개방된 상태를 유지하면서 경제를 내수 쪽으로 방향을 바꾸는 것을 의미합니다.[178]시 주석은 또한 경제의 생산성 향상을 최우선 과제로 삼았습니다.[179]시 주석은 부동산 가격의 가파른 상승에 맞서고 중국 경제의 부동산 부문 의존도를 줄이기 위해 부동산 부문 개혁을 시도했습니다.[180]19차 중국 공산당 전국대표대회에서 시 주석은 "주택은 투기 목적이 아니라 사람이 살기 위해 지어진다"고 선언했습니다.[181]2020년에 시진핑 정부는 부채가 많은 부동산 부문을 완화하는 것을 목표로 하는 "세 개의 레드 라인" 정책을 공식화했습니다.[182]시 주석은 또한 중국 공산당 의원들의 저항에 직면한 재산세를 지지했습니다.[183]

시 주석 정부는 미국과의 무역전쟁 발발로 공개적으로 중국이 이 계획을 강조하지 않았지만 핵심 기술에 대한 중국의 자립을 목표로 하는 "메이드 인 차이나 2025" 계획을 추진했습니다.[184] 2018년 무역전쟁 발발 이후 시 주석은 특히 기술 문제에 대한 "자립" 요구를 부활시켰습니다.시 주석 집권기에 국내 연구개발 지출이 크게 늘어 유럽연합(EU) 총액을 넘어섰고 2020년에는 사상 최대인 5640억 달러를 기록했습니다.[185]2022년 8월, 시진핑 정부는 반도체 독립을 위한 중국의 노력을 지원하기 위해 1,000억 달러 이상을 배정했습니다.[186]중국 정부는 또한 화웨이와 같은 기술 회사들을 보조금, 세금 감면, 신용 시설 및 기타 지원을 통해 지원함으로써 그들의 성장을 가능하게 할 뿐만 아니라 미국의 대응 조치로 이어졌습니다.[187] 시 주석은 또한 2017년에 발표된 새로운 지역인 시안의 개발에 개인적으로 참여했습니다.베이징과 허베이성의 톈진 근처의 주요 대도시가 될 계획입니다. 2050년까지 "현대 사회주의 도시"로 발전할 계획인 반면, 이전 측면은 2035년까지 지속될 것으로 예상됩니다.[188]

공동 번영은 사회주의의 필수 요건이며 중국식 근대화의 핵심 특징입니다.우리가 추구하는 공동의 번영은 물질적, 정신적 삶 모두를 위한 풍요이지만, 적은 부분을 위한 것도 아니고 획일적인 평등주의를 위한 것도 아닙니다.

— Xi Jinping during a speech in 2021[189]

2020년 11월 월스트리트저널은 창업자인 마윈이 금융에 대한 정부 규제를 비판한 데 대해 시 주석이 직접 앤트그룹의 기업공개(IPO) 중단을 지시했다고 보도했습니다.[190]시진핑 정부는 또한 중국 기업의 역외 IPO 감소를 감독했으며, 대부분의 중국 IPO는 2022년[update] 현재 상하이나 선전에서 진행되고 있으며, 전기차, 생명공학, 신재생 에너지 등 전략적이라고 판단되는 분야에서 일하는 기업의 IPO에 대한 자금 지원을 점점 더 지시하고 있습니다.인공 지능, 반도체 및 기타 높은 techn 기술 제조.

2021년부터 시 주석은 "공동 번영"이라는 용어를 홍보해 왔으며, 이 용어를 "사회주의의 필수 요건"이라고 정의하고 모든 사람을 위한 풍요라고 설명하고 초과 소득에 대한 합리적인 조정을 수반한다고 말했습니다.[189][191]공동 번영은 여러 부문, 특히 기술 및 과외 산업의 "과잉"으로 인식되는 대규모 단속 및 규제의 정당성으로 사용되었습니다.[192]기술 기업에 대한 조치의 예로는 대형 기술 기업에[193] 벌금을 부과하고 데이터 보안법과 같은 법을 통과시키는 것이 있습니다.중국은 또 주말과 공휴일에 사교육 업체들이 수익을 내고 학교 강의 계획서를 가르치는 것을 금지해 사실상 산업 전체를 파괴했습니다.[194]시 주석은 또한 베이징에 중소기업을 위한 새로운 증권 거래소를 열었는데, 이것은 그의 공동 번영 캠페인의 또 다른 부분이었습니다.[195]미성년자의 비디오게임 이용시간을 주중 90분, 주말 3시간으로 제한하고,[196] 암호화폐 전면 금지,[197] 아이돌 숭배, 팬덤, 연예인 문화[198] 단속, '씨시남' 단속 등 수많은 문화 규제도 이어졌습니다.[199]월스트리트저널(WSJ)도 2021년 10월 시 주석이 국영은행, 투자펀드, 금융감독당국 등 국내 금융기관들을 상대로 민간기업과의 유대관계가 지나치게 가까워졌는지 점검에 착수했다고 보도한 바 있습니다.조사는 중앙기율검사위원회가 주도하고 있습니다.[200]

개혁

2013년 11월 제18기 중앙위원회 제3차 전원회의에서 공산당은 경제 정책과 사회 정책의 변화를 암시하는 광범위한 개혁 의제를 발표했습니다.시 주석은 이 자리에서 과거 저우융캉의 영역이었던 거대한 내부 보안 조직에 대한 통제를 강화하고 있다는 신호를 보냈습니다.[156]시 주석을 중심으로 새로운 국가안전위원회가 구성되었습니다.2018년 시 주석이 위원회로 격상한 또 다른 임시 정책 조정 기구인 종합 심화 개혁 중앙 선도 그룹도 개혁 의제의 이행을 감독하기 위해 구성되었습니다.[201]"포괄적 심화 개혁"(全面深化改革: quánmián sh ēnhuah g ǎigé)이라고 불리는 이 개혁들은 덩샤오핑의 1992년 남방 순회 이후 가장 중요한 것으로 알려졌습니다.국민회의는 또한 경제 개혁을 발표하고 "노동을 통한 재교육"이라는 라오가이 제도의 폐지를 결의하였는데, 이는 중국의 인권 기록에 대한 오점으로 크게 여겨졌습니다.이 시스템은 수년간 국내 비평가들과 외국 관찰자들로부터 상당한 비판에 직면해 왔습니다.[156]2016년 1월에는 2자녀 정책으로 1자녀 정책이 대체되었고,[202] 2021년 5월에는 3자녀 정책으로 대체되었습니다.[203]2021년 7월 가족 규모 제한과 초과 시 벌칙이 모두 해제되었습니다.[204]

정치개혁

시진핑 정부는 특히 2018년 대규모 개편에서 중국 공산당과 국가 기구의 구조에 많은 변화를 가져왔습니다.2014년 3월, 중국 공산당 중앙위원회는 대외적으로 국무원 정보국(SCIO)으로 알려진 대외선전국(OEP)을 중국 공산당 중앙선전부로 통합했습니다.중앙선전부는 현재 "두 개의 이름을 가진 하나의 기관"이라는 협정 하에 외부 명칭으로 사용하고 있습니다.[205]그해 2월 초 사이버 보안 및 정보화를 위한 중앙 주도 그룹의 창설을 감독했습니다.이전에 OEP와 SCIO 산하에 있던 국가 인터넷 정보국(SIIO)은 중앙 주도 그룹으로 옮겨졌고 영어로 중국 사이버 공간 관리국으로 이름이 바뀌었습니다.[206]금융시스템 관리의 일환으로 2017년 국무원 기구인 금융안정발전위원회가 설립되었습니다.류허 부총리가 위원장을 맡고 있던 이 위원회는 2023년 당과 국가 개혁 과정에서 신설된 중앙금융위원회에 의해 해체되었습니다.[207]

2018년에는 관료제에 대한 더 큰 개혁이 있었습니다.그 해에 개혁, 사이버 공간 문제, 금융, 경제를 포함한 여러 중앙 주도 그룹이 있었습니다.그리고 외교 업무가 커미션으로 업그레이드되었습니다.[208][209]언론 분야에서, 언론, 출판, 라디오, 영화, 텔레비전의 국가 관리국(SAPPRFT)은 영화, 언론, 출판물이 중앙 선전부로 이관되면서 국가 라디오, 텔레비전 관리국(NRTA)으로 이름이 바뀌었습니다.[209]또한 중국중앙TV(국제판을 포함한 CCTV), 중국국가라디오(CNR), 중국국제라디오(CRI)의 관할권이 중앙선전부의 통제 하에 신설된 중국미디어그룹(CMG)으로 넘어갔습니다.[209][210]국무원 2개 부서.화교를 다루는 위원회와 종교 문제를 다루는 위원회는 UFWD의 공식적인 지도하에 있는 한편, 화교를 다루는 위원회는 통일전선공작부로 통합되었습니다.[209]

2023년에는 중국 공산당과 국가 관료 체제에 대한 추가적인 개혁, 특히 금융 및 기술 영역에 대한 당 통제의 강화가 있었습니다.[211]여기에는 중앙금융위원회(CFC), 2002년에 해체된 중앙금융업무위원회(CFWC)의 부활 등 금융 감독을 위한 두 개의 CCP 기구가 포함되었습니다.[211]CFC는 금융 시스템을 광범위하게 관리할 것이고 CFWC는 CCP의 이념적, 정치적 역할을 강화하는 데 초점을 맞출 것입니다.[207]또한 CCP 중앙과학기술위원회를 신설하여 기술 분야를 총괄하고, 새로 설립된 사회사업부는 시민단체, 상공회의소, 산업단체 등 여러 부문과 CCP 교류를 담당하게 됩니다.또한 공공 청원 및 고충 처리 업무를 처리합니다.[211]중앙홍콩·마카오 업무국도 신설돼 국무원 홍콩·마카오 업무국이 새 기구의 대외 명칭으로 바뀌게 됩니다.[211]

국무원에서 중국은행보험감독관리위원회가 국가금융감독관리국(NAFR)으로 교체되면서 증권업을 제외한 모든 금융활동을 사실상 감독하고 있습니다.중국 증권감독관리위원회의 규제를 계속 받아오다 지금은 정부기구로 승격됐습니다.[212]또한 몇 가지 규제 책임이 인민은행(PBoC)에서 SAFS로 이관되었으며, PBoC는 이전 조직에서 폐쇄되었던 전국 각지의 사무실도 다시 열 예정입니다.[213]

법률개혁

모든 사법사건에 정의가 봉사된다는 것을 국민들이 볼 수 있도록 노력해야 합니다.

— Xi Jinping during a speech in November 2020[214]

시 주석 집권당은 2014년 가을 열린 제4차 인민대회에서 법 개혁의 뗏목을 발표했고, 그는 곧바로 "중국 사회주의 법치"를 요구했습니다.정당은 정의를 전달하는 데 비효율적이고 부패, 지방 정부의 간섭, 헌법 감독의 부재로 영향을 받아온 법 제도를 개혁하는 것을 목표로 했습니다.본회의는 또 당의 절대적인 지도력을 강조하면서도 국정에서 헌법의 역할을 확대하고 헌법 해석에서 전국인민대표대회 상무위원회의 역할을 강화할 것을 주문했습니다.[215]또한 법률 절차의 투명성을 높이고, 입법 과정에 일반 시민이 더 많이 참여하며, 법률 인력의 전반적인 '전문화'를 요구했습니다.당은 또한 지방 정부가 법적 절차에 참여하는 것을 줄이기 위한 의도로 하위 수준의 법률 자원에 대해 지방 정부가 통합된 행정 감독을 할 뿐만 아니라 교차 관할 순회 법적 재판소를 설립할 계획이었습니다.[216]

군사개혁

시 주석은 2012년 집권 이후 정치 개혁과 현대화를 포함한 인민해방군의 전면 개편을 단행했습니다.[217]시 주석 치하에서 군-민 융합이 진전되었습니다.[218][219]시 주석은 군 개혁에 직접적으로 나서는 등 군사 문제에 적극적으로 참여하고 있습니다.포괄적인 군사 개혁을 감독하기 위해 2014년에 설립된 군사 개혁 중앙 지도 그룹의 지도자이자 CMC의 의장인 것 외에도, 시 주석은 군의 불법 행위와 무사안일을 청산할 것을 약속하는 많은 유명한 선언을 했습니다.시 주석은 중국 공산당에서 인민해방군을 탈정치화하면 소련과 유사한 붕괴를 초래할 것이라고 거듭 경고했습니다.[220]시 주석은 지난 2014년 신구톈대회를 열어 중국 최고의 군 간부들을 모아 1929년 구톈대회에서 마오쩌둥이 처음 수립한 '당이 군대를 절대적으로 통제한다'는 원칙을 다시 강조했습니다.[221]

군이 탈정치화되고 당에서 분리되고 국유화된 소련에서 당은 무장해제되었습니다.소련이 위기에 처했을 때, 큰 정당이 바로 그 모습으로 사라졌습니다.그에 비례하여 소련 공산당은 우리보다 더 많은 당원들이 있었지만, 아무도 일어서서 저항할 만큼 남자다운 사람이 없었습니다.

— Xi Jinping during a speech[222]

시 주석보다 앞서도 그의 행정부는 해양 문제에 대해 더 적극적인 입장을 취했고, 중국 공산당의 해양 보안군에 대한 통제력을 강화했습니다.[223]2013년, 이전에 중국의 경쟁국이었던 해양 법 집행 기관이 중국 해안 경비대에 합병되었습니다.처음에는 국가해양국과 공안부의 공동 관리 하에 있었지만, 2018년 인민무력경찰(PAP)의 관리 하에 정방형으로 배치되었습니다.[223]

시 주석은 2015년 인민해방군에서 30만 명의 병력을 감축한다고 발표해 규모가 200만 명에 달했습니다.시 주석은 이것을 평화의 제스처라고 설명한 반면 로리 메디칼프와 같은 분석가들은 이번 인하가 PLA 현대화의 일부이자 비용 절감을 위해 이루어졌다고 말했습니다.[224]2016년, 그는 PLA의 극장 지휘부 수를 7개에서 5개로 줄였습니다.[225]그는 또한 PLA의 4개의 자치 일반 부서를 폐지하고 15개 기관이 CMC에 직접 보고하는 것으로 대체했습니다.[217]그의 개혁 아래 PLA의 두 개의 새로운 분파, 즉 전략지원군과[226] 공동물류지원군이 탄생했습니다.[227]2018년에 PAP는 CMC의 단독 통제 하에 놓였고, PAP는 이전에 공안부를 통해 CMC와 국무원의 공동 지휘 하에 있었습니다.[228]: 15

2016년 4월 21일, 시 주석은 신화통신과 중국중앙TV에 의해 새로운 인민해방군 합동작전사령부의 총사령관으로 임명되었습니다.[229][230]일부 분석가들은 이러한 움직임을 힘과 강력한 리더십을 보여주기 위한 시도로 해석하고 "군사적이라기보다는 정치적"이라고 해석했습니다.[231]군사 전문가인 니 렉시옹에 따르면, 시 주석은 "군을 통제할 뿐만 아니라 절대적인 방식으로 수행하며, 전시에는 개인적으로 지휘할 준비가 되어 있습니다."[232]샌디에이고 캘리포니아 대학의 중국군 전문가에 따르면, 시 주석은 "마오와 덩이 한 일을 능가하는 범위 내에서 군을 정치적으로 통제할 수 있었다"[233]고 합니다.

시 주석 시절 중국의 공식 군사 예산은 [185]두 배 이상 늘어 2023년 사상 최대인 2,240억 달러를 기록했습니다.[234]PLA 해군은 2014~2018년 중국이 영국 해군의 전체 함정 수보다 군함, 잠수함, 지원함, 주요 수륙양용함 등을 추가하는 등 시 주석 치하에서 급성장했습니다.[235]중국은 2017년 지부티에 해군 최초의 해외 기지를 설립했습니다.[236]시 주석은 또한 중국의 핵무기 확장에 착수했으며, 그는 중국을 "강력한 전략적 억제 체계를 수립하라"고 촉구했습니다.미국 과학자 연맹(FAS)은 2023년 중국의 총 핵무기 보유량을 410개로 추정했으며, 미국 국방부는 2030년까지 중국의 핵무기 보유량이 1,000개에 이를 수 있다고 추정했습니다.[237]

대외정책

시 주석은 외교 문제뿐만 아니라 안보 문제에 대해서도 강경한 입장을 취하며 세계 무대에서 보다 민족주의적이고 적극적인 중국을 보여주고 있습니다.[238]그의 정치 프로그램은 중국이 더 단결하고 자신의 가치 체계와 정치 구조에 대해 자신감을 가질 것을 요구합니다.[239]외국 분석가들과 관측통들은 시 주석의 주요 외교 정책 목표가 강대국으로서 세계 무대에서 중국의 입지를 회복하는 것이라고 자주 말해왔습니다.[240][222][241]시 주석은 중국의 대외 정책에서 다른 나라들이 넘지 말아야 할 명시적인 레드 라인을 설정하는 "기본 사고"를 지지합니다.[242]중국 입장에서는 이러한 기준선 문제에 대한 강경한 태도가 전략적 불확실성을 감소시켜 다른 국가들이 중국의 입장을 잘못 판단하거나 중국이 국익에 부합한다고 인식하는 것을 주장하는 데 있어 중국의 결심을 과소평가하지 못하도록 합니다.[242]시 주석은 제20차 중국 공산당 전국대표대회에서 2049년까지 중국이 "복합적인 국력과 국제적 영향력 면에서 세계를 선도하는 것"을 보장하고 싶다고 말했습니다.[243]

시 주석은 중국이 이미 '강대국'이라며 신중한 외교를 펼쳤던 역대 중국 지도자들과 결별하면서 '주요국 외교'(大国外交)를 추진했습니다.그는 "늑대 전사 외교"라고 불리는 매파 외교 정책 자세를 취했고,[245] 그의 외교 정책 사상은 "시진핑의 외교 사상"이라고 통칭됩니다.[246]그는 2021년 3월 서구 세계의 힘이 쇠퇴하고 그들의 코로나19 대응이 이를 보여주는 사례라며 "동양이 상승하고 서양이 쇠퇴하고 있다"(东升西降)고 말했고, 이 때문에 중국이 기회의 시기에 접어들고 있다고 말했습니다.시 주석은 "인류를 위한 공동의 미래를 가진 공동체"를 자주 언급해왔는데, 중국 외교관들은 중국이 국제 질서를 바꾸려는 의도는 아니라고 말했지만,[248] 외국 관측통들은 중국이 국제 질서를 더 중심에 두는 새로운 질서를 원한다고 말했습니다.[249]시 주석 집권기 중국은 러시아와 함께 서방의 제재 효과를 무디게 하기 위해 남방과의 관계도 강화하는 데 주력했습니다.[250]

시 주석은 세계에서 중국에 대한 보다 우호적인 세계 여론을 조성하기 위해 중국의 '국제 담론력'(国际话语权)을 높이는 데 역점을 두었습니다.이 과정에서 시 주석은 중국의 대외 선전(外宣)과 소통 확대를 의미하는 "중국의 이야기를 잘 들려줘야 한다"(讲好中国故事)는 필요성을 강조했습니다.시 주석은 중국 내외의 비(非)중국 공산당 요소에 대한 지지를 공고히 하는 것을 목표로 하는 통일전선의 초점과 범위를 확대했고, 이에 따라 통일전선공작부를 확대했습니다.[253]시 주석은 국제질서에서 중국의 영향력을 높이는 것을 목표로 2021년, 2022년, 2023년에 각각 글로벌 개발구상(GDI),[254] 글로벌 안보구상([255]GSI), 글로벌 문명구상(GCI)을 발표했습니다.[256]

보안.

시 주석 체제에서 중국은 국제 체제의 개혁을 추진했고, 시 주석은 "글로벌 거버넌스에서 패권적 권력 구조의 거부"를 요구했습니다.[257]2014년 5월 21일 상하이에서 열린 지역 회의에서 그는 아시아 국가들에게 미국을 지칭하는 것으로 간주되는 제3국에 관여하지 말고 함께 단결하고 길을 개척할 것을 촉구했습니다."아시아의 문제는 궁극적으로 아시아인들이 처리해야 합니다.아시아의 문제는 궁극적으로 아시아인들에 의해 해결되어야 하며 아시아의 안보는 궁극적으로 아시아인들에 의해 보호되어야 합니다"라고 그는 컨퍼런스에서 말했습니다.[258]그가 제안한 글로벌 보안 이니셔티브는 러시아도 지지하는 개념인 "불가분의 보안"이라는 용어를 통합하여 새로운 글로벌 보안 아키텍처를 구축하는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다.[255]그는 또한 국제 안보 협력을 주장해 왔으며, 2021년 9월 상하이 협력 기구(SCO) 회의에서 "다른 나라의 내정 간섭"에 반대하는 목소리를 냈고, "색깔 혁명"에 대항하기 위해 공동 협력할 것을 촉구했습니다.[259]

아프리카

시진핑 체제에서 중국은 아프리카 국가들이 중국에 진 빚을 갚지 못할 것이라는 우려에 아프리카에 대한 대출을 줄였습니다.[260]시 주석은 또한 중국이 일부 아프리카 국가들의 부채를 탕감하겠다고 약속했습니다.[261]시 주석은 2021년 11월 아프리카 국가들에 중국의 코로나19 백신 10억 회분을 약속했는데, 이는 이전에 이미 공급된 2억 회분 외에 추가된 것입니다.이는 중국의 백신 외교의 일환으로 전해졌습니다.[262]

유럽 연합

시 주석 시절 중국의 노력은 유럽연합(EU)이 미국과의 경쟁에서 중립적인 위치를 유지하기 위한 것이었습니다.[263] 중국과 EU는 2020년에 포괄적 투자 협정(CAI)을 발표했지만, 이후 신장에 대한 상호 제재로 인해 협정이 동결되었습니다.[264]시 주석은 EU가 "전략적 자치"를 달성해야 한다는 요구를 지지했으며,[265] EU에 중국을 "독립적으로" 바라볼 것을 요구하기도 했습니다.[266]

인디아

중국과 인도의 관계는 시진핑 체제에서 부침을 겪었고, 이후 여러 가지 요인으로 인해 악화되었습니다.2013년, 두 나라는 데상에서 3주 동안 대치를 벌였는데, 국경 변경 없이 끝났습니다.[267]2017년, 두 나라는 인도의 동맹국인 부탄과 중국이 모두 주장하는 영토인 도클람에 대한 중국의 도로 건설에 대해 다시 [268]대립했지만, 8월 28일까지 두 나라는 상호 단절되었습니다.[269]양국 관계에서 가장 심각한 위기는 2020년 실제 통제선에서 양국이 치명적인 충돌을 일으켜 일부 군인이 사망했을 때 발생했습니다.[270][271]그 충돌은 인도가 지배하고 있던 영토의 작은 부분을 중국이 점령하는 등 심각한 관계 악화를 초래했습니다.[272]

일본

중국과 일본의 관계는 시 주석 정부 하에서 처음으로 악화되었습니다. 양국 사이에 가장 골치 아픈 문제는 중국이 댜오위다오라고 부르는 센카쿠 열도를 둘러싼 분쟁입니다.이 문제에 대한 일본의 강경한 입장이 계속되자 중국은 2013년 11월 방공식별구역을 선포했습니다.[273]그러나 이후 코로나19 범유행으로 인해 여행이 지연되었지만 시 주석이 2020년에 방문하도록 초청되는 등 관계가 개선되기 시작했습니다.[274][275]2022년 8월 교도통신은 시 주석이 직접 대만 주변에서 진행된 군사훈련에서 탄도미사일을 일본 배타적경제수역(EEZ) 내에 착륙시켜 일본에 경고를 보내기로 했다고 보도했습니다.[276]

중동

중국은 역사적으로 중동 국가들과 가까워지는 것을 경계해 왔지만, 시 주석은 이러한 접근 방식을 바꿨습니다.[277]중국은 시 주석 집권기에 이란과 사우디아라비아 모두와 더 가까워졌습니다.[277]2016년 이란을 방문한 시진핑은 이란과의 대규모 협력 프로그램을 제안했고,[278] 이후 2021년에 서명했습니다.[279]중국은 또한 사우디아라비아에 탄도 미사일을 팔았고 이라크에 7,000개의 학교를 짓는 것을 돕고 있습니다.[277]2013년, 시 주석은 이스라엘과 팔레스타인 사이에 1967년 국경에 근거한 두 국가의 해결책을 수반하는 평화 협정을 제안했습니다.[280]위구르족 문제로 오랫동안 관계가 경색됐던 터키도 중국과 가까워졌습니다.[281]2023년 3월 10일, 사우디아라비아와 이란은 2016년 베이징에서 비밀 회담을 가진 후 중국에 의해 양국 간의 협상이 중재되자 외교 관계를 복원하기로 합의했습니다.[282]

2023년 9월, 바샤르 알 아사드 시리아 대통령은 항저우에서 열린 제19회 아시안 게임 개막식에 참석해 시진핑을 만났습니다.[283]그들은 중국-시리아 전략적 동반자 관계의 수립을 발표했습니다.[284]2023년 10월 19일, 시 주석은 이스라엘-하마스 전쟁에서 휴전을 요구했습니다.[285]

북한

시진핑 체제에서 중국은 처음에 북한의 핵실험 때문에 북한에 대해 더 비판적인 입장을 취했습니다.[286]그러나 2018년부터 시 주석과 북한 지도자 김정은의 만남으로 관계가 개선되기 시작했습니다.[287]시 주석은 또한 북한의 비핵화를 지지하고,[288] 북한의 경제 개혁을 지지하는 목소리를 냈습니다.[289]일본에서 열린 G20 회의에서 시 주석은 북한에 부과된 제재를 "시의적절한 완화"를 요구했습니다.[290]2022년 제20차 중국 공산당 전국대표대회가 끝난 뒤 노동당 기관지 노동신문은 시 주석을 찬양하는 장문의 사설을 쓰며 역사적으로 김일성 주석의 이름으로 김 위원장과 시수룡(수령)을 나란히 달았습니다.

러시아

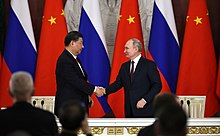

시 주석은 특히 2014년 우크라이나 사태를 계기로 러시아와 더욱 돈독한 관계를 구축했습니다.그는 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령과 돈독한 개인적 관계를 형성한 것으로 보입니다.두 사람 모두 서구의 이익에 맞서 자신을 주장하는 것을 두려워하지 않는 민족주의적 성향을 가진 강력한 지도자로 여겨집니다.[292]시진핑은 2014년 소치 동계 올림픽 개막식에 참석했습니다.시 주석 시절 중국은 러시아와 4,000억 달러 규모의 가스 거래를 체결했고, 중국은 러시아의 최대 교역국이 되었습니다.[292]

시 주석과 푸틴 대통령은 2022년 베이징 올림픽을 앞두고 2022년 2월 4일 우크라이나 국경에서 러시아의 대규모 무력 증강 과정에서 만났으며, 양국은 반미 동맹에 거의 일치하고 있으며 양국이 약속에 "제한이 없다"고 표현했습니다.[293][294]미국 관리들은 중국이 20일 베이징 올림픽이 끝난 뒤까지 러시아에 우크라이나 침공을 기다려달라고 요청했다고 전했습니다.[294]2022년 4월 시진핑은 대러 제재에 반대 의사를 밝혔습니다.[295]2022년 6월 15일, 시진핑은 주권과 안보 문제에 대한 중국의 러시아에 대한 지지를 재확인했습니다.[296]그러나 시 주석은 중국이 "모든 국가의 영토 보전"을 존중하는 데 전념하고 있다며,[297] 중국이 "유럽에서 전쟁의 불길이 다시 점화되는 것을 보고 고통을 받았다"고 말했습니다.[298]중국도 러시아의 행동에 거리를 두면서 중립국으로 자리매김했습니다.[294]2023년 2월, 중국은 "우크라이나의 극심한 위기를 해결하기 위한" 12개 항의 평화 계획을 발표했습니다. 이 계획은 푸틴 대통령에 의해 찬사를 받았지만 미국과 유럽 국가들에 의해 비판을 받았습니다.[299]

전쟁 기간 동안 볼로디미르 젤렌스키 우크라이나 대통령은 [300]중국이 푸틴의 전쟁 종식을 압박할 수 있는 경제적 지렛대를 가지고 있다며 "러시아 연방에 대한 중국 시장이 없다면 러시아는 완전한 경제적 고립을 느낄 것이라고 확신합니다.전쟁이 끝날 때까지 [러시아와의] 무역을 제한하는 것은 중국이 할 수 있는 일입니다."2022년 8월 젤렌스키는 우크라이나 전쟁이 시작된 이후 시진핑이 자신과의 직접 대화 요청에 응답하지 않았다고 말했습니다.[301]그는 또 중국이 우크라이나 전쟁에 대해 다른 접근법을 취하기를 바라면서도 매년 관계가 개선되기를 바란다면서 중국과 우크라이나가 비슷한 가치를 공유하고 있다고 말했습니다.[302]2023년 4월 26일 젤렌스키와 시 주석은 전쟁 발발 이후 첫 전화 통화를 가졌습니다.[303]

대한민국.

시 주석은 초기에 한국과의 관계를 개선했고,[286] 양국은 2015년 12월에 자유무역협정에 서명했습니다.[304]2017년부터 한국과 중국의 관계는 미사일 방어 시스템인 사드(THAAD·고고도미사일방어체계)의 구매를 둘러싸고 악화됐습니다.중국은 위협으로 보고 있지만 한국은 북한에 대한 방어 조치라고 말합니다.[305]결국 중국이 비공식 제재를 가하자 한국은 사드 구매를 중단했습니다.[306]문재인 대통령 시절 중국과 한국의 관계가 다시 좋아졌습니다.[307]

동남아

시 주석 집권 이후 중국은 남중국해에 섬을 빠르게 건설하고 군사화하고 있다고 중앙당교 결정연구시보는 시 주석이 직접 취했다고 전했습니다.[308]2015년 4월, 새로운 위성 사진은 중국이 남중국해의 스프래틀리 군도에 있는 파이어 크로스 리프에 비행장을 빠르게 건설하고 있다는 것을 밝혔습니다.[309]2014년 11월 주요 정책 연설에서 시 주석은 중국과 동남아시아 이웃 국가들 간의 관계를 악화시키는 현안을 해결하기 위해 대화와 협의를 선호하며 무력 사용의 감소를 요구했습니다.[310]

타이완

2015년 시 주석은 마잉주 대만 총통을 만났고, 이는 1950년 중국 본토에서 중국 내전이 끝난 이후 대만해협 양측 정치 지도자들이 처음으로 만난 것입니다.[311]시 주석은 중국과 대만은 떼어낼 수 없는 '한 가족'이라고 말했습니다.[312]그러나 2016년 민주진보당의 차이잉원이 대선에서 승리한 이후 관계가 악화되기 시작했습니다.[313]

시 주석은 2017년 열린 19차 당대회에서 2002년 16차 당대회 이후 지속적으로 긍정돼온 9대 원칙 중 '통일을 이끌어내는 힘으로 대만 인민에게 희망을 둔다'는 점을 제외한 6대 원칙을 재확인했습니다.[314]브루킹스 연구소에 따르면, 시진핑은 대만의 이전 민진당 정부들에 대한 전임자들보다 잠재적인 대만 독립에 대해 더 강한 언어를 사용했습니다.[314]그는 "우리는 어떤 사람, 어떤 조직, 어떤 정당도 어떤 형태로든 중국 영토의 어떤 부분도 분할하는 것을 결코 허용하지 않을 것입니다"라고 말했습니다.[314]2018년 3월, 시 주석은 대만이 분리주의 시도에 대해 "역사의 처벌"에 직면할 것이라고 말했습니다.[315]

2019년 1월, 시진핑은 "우리는 무력 사용을 포기하고 모든 필요한 수단을 취할 수 있는 선택권을 유보할 약속을 하지 않습니다"라고 말하며 대만에게 중국으로부터의 공식적인 독립을 거부할 것을 요구했습니다.그는 이러한 옵션이 "외부 간섭"에 대항하여 사용될 수 있다고 말했습니다.시 주석은 또한 "평화통일을 위한 넓은 공간을 만들 용의가 있지만, 어떤 형태의 분리주의 활동도 할 여지를 남기지 않을 것"이라고 말했습니다.[316][317]차이 총통은 연설에 응하면서 대만은 본토와의 일국양제 합의를 받아들이지 않을 것이라고 말하고, 양안 협상은 모두 정부 대 정부 차원에서 이뤄져야 한다고 강조했습니다.[318]

중국이 대만 주변에서 군사훈련을 한 뒤인 2022년 중국은 '대만 문제와 신시대 중국의 통일'이라는 백서를 발간했는데, 이 백서는 2000년 이후 처음입니다.[319]이 신문은 대만이 일국양제 공식에 따라 중화인민공화국의 특별행정구역이 될 것을 촉구하면서 [319]"소수의 국가들, 그 중에서도 미국이 가장 우선적으로 대만을 이용해 중국을 봉쇄하고 있다"고 전했습니다.[320]특히 새 백서에서는 통일 이후 중국이 대만에 군대나 관리를 파견하지 않겠다고 밝힌 부분은 제외됐습니다.[320]

미국

시 주석은 현대 세계에서 중국과 미국의 관계를 "새로운 유형의 강대국 관계"라고 불렀는데, 이는 오바마 행정부가 이를 수용하기를 꺼려온 표현입니다.[321]그의 통치하에 미국.– 후진타오 체제에서 시작된 중국 전략 및 경제 대화는 도널드 트럼프 행정부에 의해 중단되기 전까지 계속되었습니다.[322]시 주석은 중국과 미국의 관계에 대해 "만약 중국과 미국이 대립하고 있다면, 그것은 양국에 반드시 재앙을 초래할 것입니다"라고 말했습니다.[323]미국은 남중국해에서 중국의 행동에 대해 비판적인 입장을 취해왔습니다.[321]2014년에 중국 해커들이 미국 인사관리국의 컴퓨터 시스템을 손상시켜 [324]이 사무실에서 처리하는 약 2,200만 건의 인사 기록을 도난당했습니다.[325]시 주석은 또한 간접적으로 미국의 아시아에 대한 "전략적 선회"에 대해 비판적인 목소리를 내왔습니다.[326]

2017년 도널드 트럼프가 대통령이 된 후 미국과의 관계는 악화되었습니다.[327]2018년부터 미국과 중국은 고조되는 무역전쟁을 벌이고 있습니다.[328]2020년에는 코로나19 범유행으로 관계가 더욱 악화되었습니다.[329]2021년 시 주석은 미국을 중국 발전의 가장 큰 위협으로 규정하면서 "현 세계의 가장 큰 혼란의 근원은 미국"이라고 말했습니다.[247]시 주석은 또한 대부분의 경우 중국이 미국에 도전하지 않았던 이전 정책을 폐기했고, 중국 관리들은 이제 중국을 미국과 "평등한" 국가로 보고 있다고 말했습니다.[330] 2023년 3월 6일 중국인민정치협상회의(CPPCCC) 연설에서 시 주석은 "미국이 이끄는 서방 국가들.중국에 대해 전방위적인 봉쇄, 포위, 진압을 실시해 왔으며, 이는 "우리나라의 발전에 전례 없이 심각한 도전"을 가져왔다고 그는 말했습니다.[331]

2023년 11월 초, 내부자들은 파리 협정의 길을 터주고 시 주석과 버락 오바마의 회담이 선행된 2014년의 합의와 유사한 2023 유엔 기후 변화 회의를 앞두고 중국과 미국 간의 기후 협정에 대한 희망을 조심스럽게 표명했습니다.[332]재닛 옐런과 허리펑의 회담은 기후, 부채 탕감 등 여러 분야에서 중국과 미국의 협력을 강화하는 결정을 내렸지만, 예상되는 시 주석과 조 바이든의 회담에서 더 많은 것이 기대됩니다.아시아 사회 정책 연구소의 케이트 로건(Kate Logan)에 따르면, 양국 간의 협력은 "COP28에서 성공적인 결과를 위한 발판을 마련할 수 있다"고 합니다.[333]

가장 중요한 리더로서 해외여행

시 주석은 주석직을 맡은 지 약 일주일 후인 2013년 3월 22일, 중국의 가장 중요한 지도자로서 첫 번째 러시아 방문을 했습니다.그는 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령을 만났고 두 지도자는 무역과 에너지 문제에 대해 논의했습니다.이어 탄자니아, 남아프리카공화국(더반에서 열린 브릭스 정상회의에 참석), 콩고공화국 등을 방문했습니다.[334]시 주석은 2013년 6월 버락 오바마 미국 대통령과의 '셔츠 소매 정상회담'으로 캘리포니아 서니랜즈 에스테이트에 있는 미국을 방문했지만, 이것은 공식적인 국빈 방문으로 여겨지지는 않았습니다.[335]2013년 10월, 시 주석은 인도네시아 발리에서 열린 APEC 정상회의에 참석했습니다.

시 주석은 2014년 3월 네덜란드를 방문해 서유럽을 방문했고, 헤이그 핵안보정상회의에 참석한 데 [336]이어 프랑스, 독일, 벨기에를 차례로 방문했습니다.[337]그는 2014년 7월 4일 한국을 국빈 방문하여 한국의 박근혜 대통령을 만났습니다.[338]7월 14일에서 23일 사이에, 시 주석은 브라질에서 열린 브릭스 정상회담에 참석했고 아르헨티나, 베네수엘라, 쿠바를 방문했습니다.[339]

시 주석은 2014년 9월 인도를 공식 국빈 방문해 나렌드라 모디 인도 총리를 만났고, 뉴델리를 방문했고, 구자라트 주에 있는 모디 총리의 고향도 방문했습니다.[340]그는 호주를 국빈 방문하여 2014년 11월 토니 애벗 총리를 만났고,[341] 이어서 섬나라 피지를 방문했습니다.[342]시 주석은 2015년 4월 파키스탄을 방문해 중국-파키스탄 경제회랑과 관련한 450억 달러 규모의 인프라 계약을 잇따라 체결했습니다.그의 방문 동안, 파키스탄의 가장 높은 민간인 상인 니산-에-파키스탄이 그에게 수여되었습니다.[343]그리고 나서 그는 아프리카-아시아 정상회담과 반둥회의 60주년 행사에 참석하기 위해 자카르타와 인도네시아 반둥으로 향했습니다.[344]시 주석은 러시아를 방문했고 유럽에서 동맹국들의 승리 70주년을 기념하기 위한 2015 모스크바 승리의 날 퍼레이드에서 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령의 영접객이었습니다.퍼레이드에서 시 주석과 그의 부인 펑리위안은 푸틴 대통령 옆에 앉았습니다.같은 여행에서 시 주석은 카자흐스탄을 방문하여 누르술탄 나자르바예프 대통령을 만났고, 벨라루스에서 알렉산더 루카셴코도 만났습니다.[345]

2015년 9월, 시진핑은 처음으로 미국을 국빈 방문했습니다.[346][347][348]2015년 10월, 그는 중국 지도자로서는 10년 만에 처음으로 영국을 국빈 방문했습니다.[349]이는 2015년 3월 캠브리지 공작의 중국 방문에 이은 것입니다.국빈 방문 동안, 시 주석은 엘리자베스 2세 여왕, 영국 총리 데이비드 카메론과 다른 고위 인사들을 만났습니다.중국과 영국 사이의 증가된 관습, 무역, 그리고 연구 협력이 논의되었지만, 맨체스터 시티의 축구 아카데미 방문을 포함한 더 많은 비공식적인 행사들도 열렸습니다.[350]

2016년 3월, 시 주석은 미국으로 가는 도중에 체코를 방문했습니다.프라하에서 그는 체코 대통령, 총리 및 기타 대표들을 만나 체코와 중화인민공화국 간의 관계와 경제 협력을 증진시켰습니다.[351]그의 방문은 체코인들의 상당한 숫자의 항의를 받았습니다.[352]

2017년 1월, 시 주석은 다보스에서 열리는 세계 경제 포럼에 참석할 계획을 세운 첫 번째 중국 최고 지도자가 되었습니다.[353]1월 17일, 시진핑은 세계화, 세계 무역 어젠다, 그리고 세계 경제와 국제 지배에서 중국의 부상하는 위치에 대해 연설하며, 그는 "경제 세계화"와 기후 변화 협약에 대한 중국의 방어에 대한 일련의 공약을 발표했습니다.[353][354][355]리커창 총리는 2015년에, 리위안차오 부주석은 2016년에 이 포럼에 참석했습니다.2017년 3일간의 국빈 방문 동안 시 주석은 또한 세계 보건 기구, 유엔 그리고 국제 올림픽 위원회를 방문했습니다.[355]

2019년 6월 20일, 시 주석은 평양을 방문하여, 2004년 전임 후진타오 주석의 방북 이후 최초로 북한을 방문한 중국 지도자가 되었습니다.[356]6월 27일, 그는 오사카에서 열린 G20 정상회의에 참석했습니다.[357]2020년 1월 17일, 시 주석은 미얀마를 방문하여 네피도에서 윈민트 대통령, 아웅산 수치 국무위원, 민아웅 흘라잉 군 총사령관을 만났습니다.[358]

2020년에서 2022년 사이에 시 주석은 COVID-19 팬데믹으로 인한 것으로 추정되는 해외 여행을 중단했습니다.[359]2022년 2월 14일, 시 주석은 카자흐스탄 아스타나를 방문하여 카심 조마르트 토카예프 대통령을 만났습니다.[360]하루 뒤에는 2022 상하이협력기구 정상회의 참석차 우즈베키스탄을 방문했습니다.그곳에서 그는 2022년 2월 24일 러시아가 우크라이나를 침공한 이후 처음으로 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령과 중앙아시아 지도자들을 만났습니다.[361][362]

2022년 11월 15일과 16일 사이에 시 주석은 발리에서 열린 G20 정상회의에 참석하여 미국 대통령 조 바이든, 호주 총리 앤서니 알바니즈, 프랑스 대통령 엠마누엘 마크롱[363], 한국 대통령 윤석열을 포함한 수많은 세계 지도자들을 만났습니다.[364][365]11월 16일과 19일 사이에 태국에서 열린 APEC 정상회의에 참석하여 일본의 기시다 후미오 총리,[366] 뉴질랜드의 저신다 아던 총리,[367] 태국의 쁘라윳 찬오차[368] 총리, 미국의 카말라 해리스 부통령 등의 정상들을 만났습니다.[369]12월 7일과 10일 사이에 그는 사우디 아라비아의 리야드를 방문하여 살만 왕과 모하메드 빈 살만 왕세자와 총리를 만났습니다.그는 또한 걸프협력회의 회원국들을 포함한 수많은 아랍 지도자들을 만났습니다.[370]회의 기간 동안, 그는 사우디아라비아와 수많은 상업적 거래를 체결하고 중국의 공식적인 다른 국가들과의 관계 순위에서 가장 높은 수준인 포괄적인 전략적 동반자 관계로 공식적으로 격상시켰습니다.[371]

2023년 3월 20일부터 22일까지 시 주석은 2023년 전국인민대표대회 이후 첫 해외 순방지로 러시아 모스크바를 방문했습니다.이번 방문은 러시아의 우크라이나 침공과 국제형사재판소가 발부한 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령의 체포영장을 배경으로 이뤄졌습니다.[372]방문 기간 동안, 시 주석은 미하일 미슈스틴 총리뿐만 아니라 푸틴 대통령을 만났습니다.[373]푸틴 대통령과 시 주석은 관계 확대를 다짐하는 공동성명에 서명하고, 새로운 '다극 세계'를 공식적으로 추진했습니다.[372]8월 22일과 24일 사이에 시 주석은 제15차 브릭스 정상회의에 참석하기 위해 남아프리카 공화국 요하네스버그를 방문하여 아프리카 대륙의 다양한 지도자들뿐만 아니라 다양한 브릭스 지도자들을 만났습니다.[374]

경제관계

일대일로 구상(BRI)은 2013년 9월과 10월 시 주석이 카자흐스탄과 인도네시아를 방문하는 과정에서 공개했으며,[375] 이후 아시아와 유럽을 국빈 방문하는 과정에서 리커창 총리가 추진했습니다.시 주석은 카자흐스탄 아스타나에 있는 동안 이 계획을 발표하고 그것을 "황금의 기회"라고 불렀습니다.[376]BRI는 아시아, 유럽, 아프리카 및 아메리카 전역에 걸쳐 수많은 인프라 개발 및 투자 프로젝트가 참여하는 Xi의 "시그니처 프로젝트"로 불립니다.[377]BRI는 2017년 10월 24일 19차 당 대회 폐막 세션에서 중국 공산당 헌법에 추가되어 [378]그 중요성을 더욱 높였습니다.[379]BRI가 출범한 이후, 중국은 거의 150개국에 10년 만에 약 1조 달러를 대출하면서 세계 최대의 대출 기관이 되었습니다.그러나 2022년까지 많은 BRI 프로젝트가 지연되고 중국의 부채 대부분이 재정적 어려움에 처한 국가들에 의해 보유됨에 따라 중국 지도자들은 "일대일로 이니셔티브 2.0"이라고 불리는 BRI에 대해 보다 보수적인 접근 방식을 채택하게 되었습니다.[380]

시 주석은 2016년 1월 공식 출범한 인도네시아 방문에서 2013년 10월 아시아인프라투자은행(AIIB)을 공식 제안했습니다.[381][382]AIIB 가입국은 미국의 반대에도 불구하고 동맹국인 미국과 서방국가들을 포함해 수많은 국가들이 가입했습니다.[382]AIIB는 출시 이후 2022년까지 190개 프로젝트에 364억 3천만 달러를 투자했습니다.[383]시진핑의 재임 기간에는 2014년 호주,[384] 2015년 한국,[304] 2020년 더 큰 역내포괄적경제동반자협정(RCEP) 등 여러 자유무역협정(FTA) 체결이 있었습니다.[385]시 주석은 또한 중국이 2021년 9월 정식으로 가입을 신청한 가운데 중국이 환태평양경제동반자협정(CPTPP)에 가입하는 것에 관심을 표명했습니다.[386]

국가안보

시 주석은 "당과 국가의 모든 일"을 포괄하는 "전체적인 국가 안보 구조"를 요구하며 국가 안보에 많은 일을 바쳤습니다.[387]오바마 미국 대통령과 바이든 부통령과의 비공개 회담에서 중국은 '색깔 혁명'의 표적이 돼왔다며 국가 안보에 집중할 것을 예고했습니다.[388]국가안전위원회는 시 주석이 창설한 이후 반대 의견을 중심으로 지역 안보위원회를 설치했습니다.[388]시 주석 정부는 국가안보라는 명목으로 2014년 방첩법,[389] 2015년 국가안보[390] 및 테러방지법,[391] 2016년 사이버보안법[392] 및 외국 NGO 제한법,[393] 2017년 국가정보법,[394] 2021년 데이터보안법 등 수많은 법률을 통과시켰습니다.[395]시진핑 체제 하에서 중국의 대중 감시 네트워크는 극적으로 성장하여 각 국민에 대한 포괄적인 프로필이 구축되었습니다.[396]

홍콩

그의 지도 기간 동안, 시진핑은 홍콩-주하이-마카오 다리와 같은 프로젝트를 포함하여 홍콩의 중국 본토에 대한 정치적, 경제적 통합을 지지하고 추구해왔습니다.[397]그는 홍콩, 마카오 및 광둥성의 9개 도시를 통합하는 것을 목표로 하는 대만 지역 프로젝트를 추진했습니다.[397]시 주석의 더 큰 통합 추진은 홍콩의 자유 감소에 대한 두려움을 만들었습니다.[398]중앙정부가 보유하고 있고 결국 홍콩에서 시행되고 있는 많은 견해들은 2014년 국무원이 발간한 '홍콩특별행정구의 일국양제' 정책의 실천이라는 백서를 통해 개괄적으로 제시되었습니다.이 보고서는 중국 중앙정부가 홍콩에 대해 "포괄적인 관할권"을 가지고 있다는 것을 설명했습니다.[399]시 주석 집권 당시 중국 정부는 중영 공동선언도 법적으로 무효라고 선언했습니다.[399]

2014년 8월, 전국인민대표대회 상무위원회는 2017년 홍콩 행정장관 선거에 대한 일반 선거권을 허용하되, 후보자들에게 "나라를 사랑하고, 홍콩을 사랑하라"는 결정을 내렸습니다.중국 지도부가 최종적인 결정권자가 될 것을 보장하는 다른 조치들뿐만 아니라, 시위로 이어지고,[400] 친중 진영이 투표를 지연시키는 바람에 결국 입법회에서 개혁안이 부결되게 됩니다.[401]2017년 최고 경영자 선거에서 캐리 람은 중국 공산당 정치국의 지지를 받아 승리한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[402]

시 주석은 중국으로의 범죄인 인도를 허용하는 법안이 발의된 후 시작된 2019-2020 홍콩 시위에서 시위대에 맞서 홍콩 정부와 캐리 람을 지지했습니다.[403]그는 "홍콩 경찰이 법을 집행하는 데 있어 강제적인 조치를 취하고, 홍콩 사법부가 폭력 범죄를 저지른 사람들을 법에 따라 처벌할 수 있도록 강력히 지지한다"며 홍콩 경찰의 무력 행사를 옹호해왔습니다.[404]시 주석은 2019년 12월 20일 중국 반환 20주년 행사의 일환으로 마카오를 방문하면서 홍콩과 마카오에 외국군이 개입하는 것을 경고하는 [405]한편 마카오가 홍콩이 따라야 할 모델이 될 수 있음을 시사했습니다.[406]

2020년 NPCSC는 홍콩에서 정부가 도시의 반대 세력을 단속하는 것을 극적으로 확대하는 국가 보안법을 통과시켰는데, 그 조치 중에는 정치적 반대 세력에 대한 극적인 제한과 법 집행을 감독할 홍콩 관할권 밖에 중앙 정부 사무소를 만드는 것이 포함되었습니다.[399]이것은 홍콩과 본토를 더욱 긴밀하게 통합하기 위한 시 주석의 장기 프로젝트의 정점으로 보였습니다.[399]시 주석은 홍콩 반환 20주년과 25주년인 2017년과 2022년 주석 자격으로 홍콩을 방문했습니다.[407]그의 2022년 방문에서, 그는 도시에 대한 통제를 확대하기 위해 중국 정부의 지원을 받은 전직 경찰관인 존 리를 최고 책임자로 맹세했습니다.[408][409]그는 홍콩에 있는 동안 홍콩이 "혼란"에서 "안정"으로 옮겨갔다고 말했습니다.[410]존 리(John Lee)가 최고 통치권자가 된 이후, 리(Lee)를 포함한 홍콩 정부 관리들은 시 주석에 대해 중국과 유사하지만 이전에 이 도시에서 전례가 없는 공개적인 충성심을 보여주었습니다.[411]

인권

인권감시기구(Human Rights Watch)에 따르면, 시진핑은 2012년 지도자가 된 이후 "인권에 대한 광범위하고 지속적인 공격을 시작했다"고 합니다.[412]인권위는 또 중국 내 탄압이 "톈안먼 사태 이후 최악의 수준"이라고 밝혔습니다.[413]집권 이후 수백 명이 구금되는 등 시 주석은 풀뿌리 행동주의를 강력히 단속해 왔습니다.[414]그는 2015년 7월 9일, 200명 이상의 변호사, 법률 보조원, 인권 운동가들이 구금된 709건의 단속을 주재했습니다.[415]그의 임기는 쉬즈융과 같은 활동가들뿐만 아니라 새로운 시민 운동과 동일시되는 수많은 사람들의 체포와 투옥을 목격했습니다.웨이취안 운동의 저명한 법률가 푸즈창도 체포되어 구금되었습니다.[416]

2017년, 장시성의 지방 정부는 기독교인들에게 그 나라의 비공식 교회에 대한 일반적인 캠페인의 일환으로 예수님의 사진을 시진핑으로 교체하라고 말했습니다.[417][418][419]현지 소셜 미디어에 따르면 관리들은 "그들을 종교를 믿는 것에서 당을 믿는 것으로 변화시켰습니다."[417]활동가들에 따르면, "시 주석은 1982년 중국 헌법에 종교의 자유가 명시된 이후 중국에서 가장 극심한 기독교의 조직적 탄압을 벌이고 있다"고 하며, 중국의 종교를 감시하는 목사들과 단체들에 따르면, "십자가를 파괴하고 성경을 불태우고,"교회를 폐쇄하고 신도들에게 그들의 믿음을 포기하는 문서에 서명하도록 명령합니다."[420]

시 주석 체제에서 중국 공산당은 소수 민족에 대한 동화주의 정책을 수용하여 2019년까지 자국 내 긍정적인 행동을 [421]축소하고 2021년 10월 소수 민족 어린이가 모국어로 교육받을 권리를 보장하는 문구를 폐지하여 국가 언어 교육을 강조하는 문구로 대체했습니다.[422]2020년, 천샤오장은 1954년 이래 최초의 한족 단체장인 국가민족문제위원회 위원장으로 임명되었습니다.[423]2022년 6월 24일, 또 다른 한족인 판위에( became y)가 위원장이 되었고, 그는 소수 민족에 대한 동화주의 정책을 가지고 있는 것으로 알려졌습니다.시 주석은 "한족 우월주의나 지역 민족 우월주의는 중국 국가의 공동체 발전에 도움이 된다"고 말함으로써 다수 민족인 한족과 소수 민족 사이의 공식적인 견해를 정리했습니다.[425]

신장

2013년과 2014년 신장에서 여러 차례의 테러 공격이 있은 후, 중국 공산당 지도자들은 공격의 해결책을 찾기 위해 비밀 회의를 열었고,[426] 이로 인해 시 주석은 2014년에 대규모 구금과 그곳의 민족 위구르인들에 대한 감시와 관련된 폭력 테러에 반대하는 강경한 캠페인을 시작하게 되었습니다.[427][428]시 주석은 2014년 4월 27일에서 30일 사이에 신장 시찰을 했습니다.[429]이 프로그램은 천광궈(o光國)가 신장 중국 공산당 서기장으로 임명된 후인 2016년에 대대적으로 확대되었습니다.이 캠페인에는 2020년까지 대부분 위구르인이지만 다른 인종 [426]및 종교 소수자를 포함한 180만 명을 수용하는 수용소와 2019년까지 위구르인의 출산율이 크게 감소하는 출산 억제 캠페인이 포함되었습니다.[430]다양한 인권 단체와 전직 수감자들은 이 수용소를 위구르족과 다른 소수 민족들이 중국의 다수 민족인 한족 사회에 강제로 동화된 "집중 수용소"라고 묘사했습니다.[431]이 프로그램은 일부 관찰자들에 의해 대량학살이라고 불렸고, 유엔 인권 사무소의 보고서는 그것들이 반인도적인 범죄에 해당할 수 있다고 말했습니다.[432][433]

2019년 11월 언론에 유출된 중국 정부 내부 문건에는 시 주석이 직접 신장에서 보안 단속을 지시한 것으로 나타나 당은 "절대 자비를 베풀지 말라"며 관리들은 "극단주의 바이러스에 감염된 사람들을 진압하기 위해 인민민주독재의 모든 무기"를 사용한다고 밝혔습니다.[428][434]신문들은 또 시 주석이 연설에서 이슬람 극단주의에 대해 "고통스럽고 개입적인 치료의 기간"으로만 다룰 수 있는 "바이러스"나 "약물"에 비유하며 거듭 논의한 것으로 나타났습니다.[428]그러나 그는 또한 위구르인에 대한 차별에 대해 경고하고 중국의 이슬람교를 근절하기 위한 제안을 거부하면서 그러한 종류의 관점을 "편향적이고 심지어 잘못된 것"이라고 말했습니다.[428]국제 수용소 건설에 있어서 시 주석의 정확한 역할은 공개적으로 보도되지 않았지만, 그가 배후에 있는 것으로 널리 알려져 있고, 그의 말이 신장 자치구 진압의 주요 명분이 되었습니다.[435][436]2022년 유출된 신장 경찰 파일에서 자오커지 공안부 장관의 말을 인용한 문서는 시 주석이 수용소를 알고 있었음을 시사했습니다.[437]

코로나19 범유행

2020년 1월 20일, 시 주석은 우한에서 발생한 신종 코로나바이러스 감염증에 대해 처음으로 언급하고 바이러스의 확산을 억제하기 위한 노력을 지시했습니다.[438]그는 리커창 총리에게 코로나19 대응에 대한 일부 책임을 부여했는데, 월스트리트저널은 대응이 실패할 경우 비판으로부터 자신을 잠재적으로 고립시키려는 시도라고 제안했습니다.[439]정부는 초기에 봉쇄와 검열로 팬데믹에 대응했고, 초기 대응은 중국 내에서 광범위한 반발을 일으켰습니다.[440]그는 1월 28일 세계보건기구(WHO)의 테워드로스 아드하놈 거브러여수스 사무총장을 만났습니다.[441]슈피겔은 2020년 1월 시 주석이 테워드로스 아드하놈에게 코로나19의 발병에 대한 전 세계적인 경고 발표를 보류하고 바이러스의 인간 대 인간 전염에 대한 정보를 보류하도록 압력을 가했다고 보도했습니다.[442]2월 5일, 시 주석은 베이징에서 캄보디아 훈센 총리와 회담을 가졌는데, 이는 발병 이후 중국에 들어오는 첫 번째 외국 지도자였습니다.[441]우한에서 코로나19 발병이 통제된 후 시 주석은 3월 10일 도시를 방문했습니다.[443]

우한에서의 발병을 통제한 후, 시 주석은 국가의 국경 내에서 바이러스를 최대한 통제하고 억제하는 것을 목표로 하는 공식적으로 "역동적 제로 코로나 정책"[444]이라고 불리는 것을 선호했습니다.이것은 지역 봉쇄와 대량 검사를 포함했습니다.[445]처음에는 중국이 코로나19 사태를 진압한 것으로 인정받았지만, 이 정책은 이후 외국 및 일부 국내 관측통들로부터 전 세계와 접촉하지 않고 경제에 큰 타격을 입혔다는 비판을 받았습니다.[445]이 접근 방식은 특히 2022년 상하이 봉쇄 기간 동안 비판을 받았는데, 이는 수백만 명의 사람들을 집으로 내몰고 도시 경제를 손상시켜 [446]가까운 시진핑 국가주석이자 도시의 당서기인 리창의 이미지를 손상시켰습니다.[447]반대로, 시진핑은 이 정책이 사람들의 생명 안전을 보호하기 위해 고안되었다고 말했습니다.[448]2022년 7월 23일 국가보건위원회는 시 주석과 다른 최고 지도자들이 현지 코로나19 백신을 복용했다고 보고했습니다.[449]

제20차 중국 공산당 대회에서 시 주석은 "역동적인 제로 코로나"를 "확고하게" 수행할 것이며 "전투에서 반드시 승리할 것"[450]이라고 약속하면서 제로 코로나 정책의 지속을 확인했지만,[451] 중국은 그 이후 몇 주 동안 정책의 제한적 완화를 시작했습니다.[452]2022년 11월에는 중국의 코로나19 정책에 항의하는 시위가 벌어졌는데, 움치의 한 고층 아파트에서 발생한 화재가 계기가 되었습니다.[453]시위는 여러 주요 도시에서 열렸으며, 일부 시위대는 시 주석과 중국 공산당의 통치 종식을 요구했습니다.[453]시위는 12월까지 대부분 진압되었지만,[453] 정부는 그 이후로 코로나19 규제를 더 완화했습니다.[454]2022년 12월 7일, 중국은 경미한 감염에 대해 자택 격리 허용, PCR 검사 감소, 지역 공무원의 봉쇄 시행 권한 감소 등 코로나19 정책에 대한 대규모 변경을 발표했습니다.[455]

환경정책

2020년 9월, 시 주석은 중국이 "2030년 기후 목표(NDC)를 강화하고, 2030년 이전에 배출량을 정점으로 하며, 2060년 이전에 탄소 중립을 달성하는 것을 목표로 할 것"이라고 발표했습니다.[456]이를 달성할 경우 지구 기온의 예상 상승폭이 0.2~0.3℃ 낮아질 것으로 예상됩니다. 이는 "기후행동 추적기가 추정한 단일 감소폭 중 가장 큰 것"입니다.[456]시 주석은 "인류는 더 이상 자연의 경고를 무시할 여유가 없다"며 코로나19 대유행과 자연파괴의 연관성을 결정 이유 중 하나로 언급했습니다.[457]9월 27일, 중국 과학자들은 목표를 어떻게 달성할지에 대한 구체적인 계획을 발표했습니다.[458]2021년 9월, 시 주석은 중국이 배출 감소에 잠재적으로 "매우 중요한" 것으로 알려진 "석탄 화력 발전 프로젝트"를 해외에 건설하지 않을 것이라고 발표했습니다.일대일로 이니셔티브에는 이미 2021년 상반기에 그러한 프로젝트에 대한 자금 조달이 포함되지 않았습니다.[459]

시진핑은 COP26에 개인적으로 참석하지 않았습니다.그러나 셰전화 기후변화 특사가 이끄는 중국 대표단이 참석했습니다.[460][461]회의에서 미국과 중국은 서로 다른 조치에 대해 협력함으로써 온실가스 배출을 줄이기 위한 틀에 합의했습니다.[462]

거버넌스 스타일

매우 비밀스러운 지도자로 알려진, 시진핑이 어떻게 정치적인 결정을 내리는지 혹은 그가 어떻게 권력을 잡게 되었는지에 대해서는 공개적으로 알려진 바가 거의 없습니다.[463][464]시 주석의 연설은 일반적으로 만들어진 지 몇 달 또는 몇 년 후에 공개됩니다.[463]시 주석은 또 가장 중요한 지도자가 된 이후 외국 정상들과의 드문 공동 기자회견을 제외하고는 한 번도 기자회견을 하지 않았습니다.[463][465]월스트리트저널은 후진타오 같은 역대 지도자들이 주요 정책의 세부 사항을 하급 관리들에게 맡긴 것과 대조적으로 시 주석은 통치에 있어 마이크로 관리를 선호한다고 보도했습니다.[84]보도에 따르면, 장관 관리들은 슬라이드 쇼와 오디오 보고서를 만드는 등 다양한 방법으로 시 주석의 관심을 끌려고 노력합니다.월스트리트저널도 시 주석이 2018년 성과 검토 시스템을 만들어 충성도 등 다양한 조치에 대해 관리들에게 평가를 내렸다고 보도했습니다.[84]이코노미스트에 따르면 시 주석의 명령은 일반적으로 모호하여 하급 관리들이 그의 말을 해석하도록 남겼습니다.[435]중국 관영 매체 신화통신은 시 주석이 "주요 정책 문서 초안을 모두 개인적으로 검토한다"며 "아무리 저녁 늦게라도 그에게 제출된 모든 보고서는 다음날 아침 지시와 함께 반송됐다"[466]고 전했습니다.공산당 당원들의 행동과 관련하여, 시 주석은 "두 가지 의무" (당원들은 오만하거나 경솔해서는 안되며 열심히 일하는 정신을 지켜야 한다)와 "6가지 의무" (당원들은 형식주의, 관료주의, 선물 주기, 호화로운 생일 축하 행사, 쾌락주의, 사치스러운 행위에 대해 반대한다고 말해야 합니다)를 강조합니다.[175]: 52 시 주석은 관료들에게 자기 비판을 실천할 것을 요구했는데, 이는 관측통들에 따르면 국민들 사이에서 덜 부패하고 더 인기 있는 것처럼 보이기 위해서입니다.[467][468][469]

정치적 입장

중국몽

시진핑과 중국 공산당 이념가들은 중국의 지도자로서 중국에 대한 그의 포괄적인 계획을 묘사하기 위해 "Chinese Dream"이라는 문구를 만들었습니다.시 주석은 2012년 11월 29일 중국 국가박물관을 고위급으로 방문한 자리에서 이 문구를 처음 사용했는데, 그곳에서 그는 상무위원 동료들과 함께 "국가 부흥" 전시회에 참석하고 있었습니다.이후 이 문구는 시 주석 시대의 대표적인 정치 슬로건이 되었습니다.[470][471]"Chinese Dream"이라는 용어의 기원은 불분명합니다.이 문구는 이전에 언론인들과 학자들에 의해 사용된 적이 있지만,[472][473] 일부 출판물들은 이 용어가 아메리칸 드림의 개념에서 영감을 얻은 것 같다고 주장했습니다.이코노미스트는 구체적인 포괄적인 정책 규정이 없는 추상적이고 접근 가능해 보이는 이 개념의 성격은 전임자들의 전문용어에 치우친 이념에서 의도적으로 벗어난 것일 수 있다고 지적했습니다.[474]시 주석은 "중국의 꿈"을 "중국 국가의 위대한 부흥"이라는 문구와 연결시켰습니다.[475][e]

최근 몇 년 동안 시 주석과 같은 중국 공산당의 최고 정치 지도자들은 한페이와 같은 고대 중국 철학자들을 유교와 더불어 중국 사상의 주류로 복원하는 것을 감독했습니다.2013년 다른 관리들과의 회의에서 그는 공자의 말을 인용하여 "덕으로 다스리는 자는 북극성과 같고, 그 자리를 지키고, 많은 별들이 경의를 표한다"고 말했습니다.그는 지난 11월 공자의 출생지인 산둥을 방문하면서 학자들에게 서구 세계가 "자신감의 위기를 겪고 있다"며 중국공산당이 "중국의 뛰어난 전통문화의 충실한 계승자이자 발기인"이라고 말했습니다.[476]

몇몇 분석가들에 따르면, 시진핑의 지도력은 고대 정치 철학인 법치주의의 부활로 특징지어졌습니다.[477][478][479]한페이는 호의적인 인용으로 새로운 명성을 얻었는데, 시 주석이 인용한 한페이의 한 문장은 중국의 지방, 지방 및 국가 수준의 공식 매체에 수천 번 등장했습니다.[479]시 주석은 또한 성리학 철학자 왕양밍을 지지하며 지역 지도자들에게 그를 홍보하라고 말했습니다.[480]

시 주석은 또 중국 전통문화를 자주 공격하던 중국 공산당의 이전 경로에서 벗어나 중국 전통문화의 부활을 감독했습니다.[481]그는 전통 문화를 민족의 "영혼"이자 중국 공산당 문화의 "기반"이라고 불렀습니다.[482]시 주석은 또한 마르크스주의의 기본 원칙과 중국의 전통 문화를 통합해야 한다고 주장했습니다.[256]한족의 전통 의상인 한푸는 그의 치하에서 전통 문화의 부활과 관련하여 부활했습니다.[483]그는 이후 중국 공산당 헌법에 추가된 "자신감의 4대 사항"을 제정하여 중국 공산당 위원들과 정부 관리들, 중국 인민들에게 "우리가 선택한 길에 자신감을 갖고, 우리의 지도 이론에 자신감을 갖고, 우리의 정치 체제에 자신감을 갖고, 우리의 문화에 자신감을 가질 것"을 요구하고 있습니다.그는 2023년에 "문명의 다양성을 존중하고 인류의 공동 가치를 옹호하며 문명의 계승과 혁신을 중시하며 국제적인 인적 교류와 협력을 강화할 것"[256]을 촉구하는 글로벌 문명 이니셔티브를 발표했습니다.

이념

시 주석은 "사회주의만이 중국을 구할 수 있다"고 말했습니다.[484]시 주석은 또 중국 특색의 사회주의를 "민족 회춘을 실현하는 유일한 올바른 길"이라고 선언했습니다.[485]BBC 뉴스에 따르면, 중국 공산당이 1970년대 경제 개혁을 시작한 이후 공산주의 이념을 포기한 것으로 인식되었지만, 일부 관측통들은 시진핑이 전 호주 총리 케빈 러드에 의해 마르크스-레닌주의자로 묘사되는 [486]"공산주의 프로젝트의 아이디어"를 더 믿고 있다고 믿습니다.[487]시 주석이 이념을 우선시하는 것을 강조한 것은 결국 공산주의를 실현하겠다는 당의 목표를 재확인하고 공산주의를 비실용적이거나 무관한 것으로 치부하는 사람들을 질책하는 것입니다.[163]시 주석은 공산당의 이상을 당원의 등골에 있는 '칼슘'이라고 표현했는데, 그렇지 않으면 당원은 정치적 부패의 '골다공증'을 겪고 똑바로 설 수 없게 됩니다.[163]

시 주석은 사회주의가 결국 자본주의에 승리할 것이라는 견해에 동조하면서 "자본주의 사회의 기본 모순에 대한 마르크스와 엥겔스의 분석은 시대에 뒤떨어진 것도 아니며 자본주의는 소멸하고 사회주의는 승리할 수밖에 없다는 역사적 유물론적 견해도 아니다"[488]라고 말했습니다.시 주석은 서구의 영향을 받는 경제학의 영향력을 줄이는 것을 목표로 "중국 특색의 사회주의 정치경제"의 증가를 중국 학계의 주요 연구 주제로 감독했습니다.[488]그는 "자본의 무질서한 확장"이라고 생각하는 것에 대해 중단을 요구했지만, "비공영자본을 포함한 모든 유형의 자본의 활력을 자극하고 그 긍정적인 역할에 전폭적인 역할을 할 필요가 있다"고 말하기도 했습니다.[488]

중국의 성공은 사회주의가 죽지 않았다는 것을 증명합니다.번창하고 있습니다.중국에서 사회주의가 실패하고 우리 공산당이 소련의 당처럼 무너지면 세계 사회주의는 긴 암흑기로 사라지게 될 것이라고 상상해 보세요.그리고 공산주의는 칼 마르크스가 말한 것처럼 흐지부지한 채 잊혀지지 않는 유령이 될 것입니다.

— Xi Jinping during a speech in 2018[489]

시 주석은 "정부, 군대, 사회, 학교, 북쪽, 남쪽, 동쪽, 서쪽, 당이 그들을 모두 이끈다"며 중국 공산당에 대한 더 큰 통제를 지지했습니다.[490]그는 2021년 중국공산당 100주년 행사에서 "중국공산당이 없으면 새로운 중국도, 국가부흥도 없을 것"이라며 "당의 지도력은 중국 특색의 사회주의를 규정하는 특징이며 이 체제의 가장 큰 강점을 구성한다"고 말했습니다.[491]그는 "중국 특색의 사회주의가 21세기 사회주의 발전의 기수가 됐다"며 중국은 많은 좌절에도 불구하고 중국 공산당 체제에서 큰 진전을 이뤘다고 말했습니다.[489]그러나 그는 중국 공산당 체제의 중국이 부흥을 완수하는 데는 오랜 시간이 걸릴 것이며, 이 기간 동안 당원들은 중국 공산당의 통치가 무너지지 않도록 경계해야 한다고 경고했습니다.[489]

시 주석은 "입헌군주제, 황실복고, 의회주의, 다당제와 대통령제, 우리가 고려했고 시도했지만 아무 효과가 없었다"며 중국에 대한 다당제를 배제했습니다.[492]하지만 시 주석은 "중국의 사회주의 민주주의는 가장 포괄적이고 진실하며 효과적인 민주주의"라며 중국을 민주주의 국가로 생각하고 있습니다.[493]중국의 민주주의에 대한 정의는 자유민주주의와 다르고 마르크스주의에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다.–레닌주의는 "인민의 민주독재"와 "민주중앙주의"라는 문구에 기반을 두고 있습니다.[493]시 주석은 또한 "전 과정 인민 민주주의"라는 용어를 만들었는데, 이 용어는 그가 "인민을 주인으로 삼는 것"이라고 말했습니다.[494]외국 분석가들과 관측통들은 중국이 일당 독재 국가이고 시 주석은 권위주의 지도자라며 중국이 민주주의 국가라는 점에 대해 광범위하게 이의를 제기해 왔습니다.[501]안날레나 베어복 독일 외무장관을 비롯한 일부 [502]관측통들은 전임자들에 비해 보이지 않는 시 주석 주변 권력의 거대한 중앙집권화를 거론하며 시 주석을 독재자로 규정했습니다.[503][504]시 주석은 또한 현대화의 유일한 방법으로 서구화를 거부하고 대신 "중국식 현대화"라고 말하는 것을 홍보했습니다.[505]그는 중국식 현대화의 일환으로 거대한 인구의 현대화, 공동 번영, 물질적 및 문화적 윤리적 발전, 인류와 자연의 조화, 평화로운 발전 등 다섯 가지 개념을 제시했습니다.[506]

시진핑 사상

2017년 9월, 중국 공산당 중앙위원회는 일반적으로 "시진핑의 신시대 중국 특색 사회주의 사상"이라고 불리는 시 주석의 정치 철학이 당헌의 일부가 될 것이라고 결정했습니다.[507][508]시 주석은 2017년 10월 19차 당 대회 개막일 연설에서 "새로운 시대를 위한 중국 특색의 사회주의 사상"을 처음 언급했습니다.그의 정치국 상무위원회 동료들은 시 주석의 대회 기조연설에 대한 자체 검토에서 "사상" 앞에 "시진핑"이라는 이름을 붙였습니다.[509]2017년 10월 24일, 제19차 당 대회는 폐회에서 시진핑 사상을 중국 공산당 헌법에 편입시키는 것을 승인했고,[104] 2018년 3월 전국인민대표대회는 시진핑 사상을 포함하는 것으로 국가 헌법을 변경했습니다.[510]

시 주석 자신은 사상을 중국 특색의 사회주의를 중심으로 만들어진 광범위한 틀의 일부라고 설명했는데, 이는 덩샤오핑이 만든 용어로 중국을 사회주의의 주요 단계에 올려놓았습니다.시진핑의 동료들에 의한 공식적인 당 문서와 선언에서 사상은 마르크스주의의 연속이라고 합니다.–레닌주의, 마오쩌둥 사상, 덩샤오핑 이론, 3대 대표론, 발전에 대한 과학적 전망은 "중국 조건에 채택된 마르크스주의"와 현대적 고려를 구현하는 일련의 지도 이념의 일부입니다.[509]중국공산당 중앙당 학파의 두 교수는 이를 "21세기 마르크스주의"라고 표현하기도 했습니다.[16]시진핑 주석의 최고 정치 고문이자 가까운 동맹인 왕후닝은 시진핑 사상을 발전시키는 데 중추적인 인물로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[16]시진핑 사상 뒤에 숨겨진 개념과 맥락은 외국어 출판사가 국제 청중을 위해 출판한 시진핑의 중국 통치 책 시리즈에 자세히 설명되어 있습니다.1권은 2014년 9월에, 2권은 2017년 11월에 출판되었습니다.[511]

시진핑 사상을 가르치는 앱은 중국의 집권 중국 공산당이 매일 간부들에게 정치 교리에 몰입할 것을 요구하는 새로운 캠페인을 시작하면서 2019년 중국에서 가장 인기 있는 스마트폰 앱이 되었습니다.쉬에시 치앙궈는 현재 애플 국내 앱스토어에서 가장 많이 다운로드된 아이템으로 위챗, 틱톡 등 수요가 많은 소셜미디어 앱을 능가하고 있습니다.[512]2021년 정부는 시진핑 사상을 초등학교부터 대학교까지 포함한 교육과정에 포함시켜 학부모들의 반발을 불러일으켰습니다.지난 30년 동안 대부분의 기간 동안, 정치 이념과 공산주의 교리는 중학교 때까지 중국 학교에서 가르치는 표준이 아니었고, 교과서에는 시 주석과 같은 단일 지도자에 대한 강조가 덜한 더 넓은 중국 지도자들이 등장했습니다.[513]

개인생활

가족

시 주석의 첫 번째 결혼은 1980년대 초 영국 주재 중국 대사인 커화의 딸인 커링링과의 결혼이었습니다.그들은 몇 년 안에 이혼했습니다.[514]두 사람은 "거의 매일" 싸웠다고 전해졌고, 이혼 후 케는 영국으로 이주했습니다.[8]1987년, 시진핑은 중국의 유명한 포크 가수 펑리위안과 결혼했습니다.[515]시진핑과 펑은 1980년대에 많은 중국 커플들이 그랬던 것처럼 친구들에 의해 소개되었습니다.시 주석은 그들의 구애 기간 동안 노래 기술에 대해 문의하면서 학자로 유명합니다.[516]중국의 호인 펑리위안은 그의 정치적인 진보가 있기 전까지 시진핑보다 대중에게 더 잘 알려져 있었습니다.부부는 주로 각자의 직업 생활로 인해 떨어져 사는 경우가 많았습니다.펭은 중국의 "퍼스트 레이디"로서 그녀의 전임자들과 비교했을 때 훨씬 더 눈에 띄는 역할을 해왔습니다. 예를 들어, 펭은 2014년 3월 세간의 이목을 끄는 중국 방문에서 미국의 영부인 미셸 오바마를 주최했습니다.[517]

시 주석과 펑 여사 사이에는 2015년 봄에 하버드 대학교를 졸업한 시밍제(Xi Mingze)라는 딸이 있습니다.하버드에 있는 동안, 그녀는 가명을 사용했고 심리학과 영어를 공부했습니다.[518]시 주석의 가족은 CMC가 운영하는 베이징 북서부의 정원과 주택가인 제이드 스프링 힐에 집을 갖고 있습니다.[519]

2012년 6월, 블룸버그 통신은 시 주석의 대가족 구성원들이 상당한 사업적 이익을 가지고 있다고 보도했지만, 그가 그들을 돕기 위해 개입했다는 증거는 없었습니다.[520]이 기사에 대해 중국 본토에서는 블룸버그 웹사이트가 차단됐습니다.[521]시 주석이 반부패 운동을 시작한 이후, 뉴욕 타임즈는 그의 가족들이 2012년부터 기업과 부동산 투자를 매각하고 있다고 보도했습니다.[522]시 주석의 처남 [523]덩자구이를 포함해 중국 공산당 정치국 전현직 고위 지도자 7명을 포함해 고위 관리들의 친인척이 파나마 페이퍼에 이름을 올렸습니다.시 주석이 정치국 상무위원으로 있을 때 덩샤오핑은 영국령 버진아일랜드에 두 개의 포탄 회사를 두고 있었지만, 시 주석이 2012년 11월 중국 공산당 총서기에 취임할 때쯤에는 휴면 상태였습니다.[524]

성격

펑 여사는 시진핑이 열심히 일하고 현실적이라고 묘사했습니다: "그가 집에 왔을 때, 저는 집에 어떤 지도자가 있는 것처럼 느껴본 적이 없습니다.제 눈에는 그가 제 남편일 뿐입니다."[525]1992년 워싱턴포스트(WP) 저널리스트 레나 선(Lena H. Sun)은 당시 푸저우(福州) 중국 공산당 서기장이었던 시 주석과 인터뷰를 가졌고, 선은 시 주석을 또래의 많은 관리들보다 훨씬 편안하고 자신감이 넘쳤다며 주석을 달지 않고 이야기했다고 말했습니다.[526]그를 아는 사람들에 의해 그는 2011년 워싱턴 포스트 기사에서 "실용적이고, 진지하고, 신중하고, 열심히 일하고, 현실에 충실하고, 저자세"라고 묘사되었습니다.그는 문제 해결에 능숙하고 "고위직의 특권에는 관심이 없어 보인다"고 묘사되었습니다.[527]

공공생활

시 주석에 대한 중국 국민들의 의견은 중국 내에서 독립적인 설문조사가 존재하지 않고 소셜미디어에 대한 검열이 심하기 때문에 가늠하기 어렵습니다.[528]하지만, 그는 이 나라에서 널리 인기가 있는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[529][530]하버드 케네디 스쿨의 애쉬 센터(Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation)가 공동 후원한 2014년 여론조사에 따르면, 시 주석은 국내 지지율 10점 중 9점을 차지했습니다.[531]2019년 7월에 발표된 유고브 여론조사에 따르면 중국 본토 사람들의 약 22%가 시 주석을 가장 존경하는 인물로 꼽고 있는데, 이 수치는 홍콩 주민들의 경우 5% 미만이었습니다.[532]2019년 봄, 퓨 리서치 센터는 호주, 인도, 인도네시아, 일본, 필리핀 및 한국을 기반으로 하는 6개국 미디어 중 시진핑에 대한 신뢰도를 조사했는데, 이는 중위 29%가 세계 문제와 관련하여 올바른 일을 할 수 있는 시진핑에 대한 신뢰도를 가지고 있음을 나타냅니다.중간값 45%는 자신감이 없는 것으로 북한 김정은(23% 신뢰, 53% 신뢰 없음)보다 약간 높은 수치입니다.[533]2021년 폴리티코와 모닝컨설트의 여론조사에 따르면 미국인의 5%는 시 주석에 대해 우호적인 의견을, 38%는 비호의적인 의견을, 17%는 무의견을, 40%는 복수로 시 주석에 대해 들어본 적이 없는 것으로 나타났습니다.[534]

2017년 이코노미스트는 그를 세계에서 가장 영향력 있는 인물로 선정했습니다.[535]2018년 포브스는 5년 연속 순위에 올랐던 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령을 대신해 그를 세계에서 가장 강력하고 영향력 있는 인물로 선정했습니다.[536]2013년 이래로, 정보의 자유에 대한 권리를 보호하는 것을 목표로 하는 국제 비영리 및 비정부 기구인 국경 없는 기자회는 언론 자유 약탈자 명단에 시 주석을 포함시켰습니다.[537]

역대 중국 지도자들과 달리 중국 관영 매체들은 여전히 엄격하게 통제되고 있지만 시 주석의 사생활에 대해 더 포괄적인 시각을 내놨습니다.신화통신에 따르면 시 주석은 매일 1㎞씩 수영과 산책을 하며 시간이 나는 대로 걸으며 외국 작가, 특히 러시아 작가에 관심이 많습니다.[466]그는 라이언 일병 구하기, 디파티드, 대부와 왕좌의 게임과 같은 영화와 TV 프로그램을 [538][539][540]사랑하는 것으로 알려져 있으며 독립 영화 제작자 지아장케를 칭찬하기도 합니다.[541]중국 관영 매체들은 또한 그를 중국의 이익을 위해 일어설 결심을 한 아버지 같은 인물이자 인민의 한 사람으로 묘사했습니다.[464]

명예

| 데코레이션 | 국가/조직 | 날짜. | 메모 | 심판. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 황금 올림픽 기사단 | 2013년 11월 19일 | 올림픽 운동의 최고상 | [542] | ||

| 레오폴트 훈장 그랜드 코돈 | 2014년 3월 30일 | 벨기에 최고위급 | [543] | ||

| 해방자 훈장 그랜드 코돈 | 2014년 7월 20일 | 베네수엘라 최고위급 | [544] | ||

| 호세 마르티 훈장 | 2014년 7월 22일 | 쿠바 훈장 | [545] | ||

| 니산에파키스탄 | 2015년 4월 21일 | 파키스탄 최고 민간인상 | [546] | ||

| 압둘아지즈 알 사우드 훈장 | 2016년 1월 19일 | 사우디아라비아 훈장 | [547] | ||

| 세르비아 공화국 훈장 칼라 | 2016년 6월 18일 | 세르비아의 최고 국가 훈장 | [548] | ||

| 평화와 우정 증진을 위한 훈장 | 2016년 9월 29일 | 벨라루스 훈장 | [549] | ||

| 그랜드 크로스 명예 훈장 | 2016년 11월 21일 | 페루 훈장 | [550] | ||

| 성 안드레 훈장 | 2017년7월3일 | 러시아의 최고령 | [551] | ||

| 팔레스타인 대공국 | 2017년 7월 18일 | 팔레스타인의 최고 민간 질서 | [552] | ||

| 자이드 훈장 | 2018년 7월 20일 | 아랍 에미리트 연합국의 최고 민간인 훈장 | [553] | ||

| 사자자리 대십자가 | 2018년 7월 29일 | 세네갈 훈장 | [554] | ||

| 해방군 대장 산 마르틴의 훈장 칼라 | 2018년 12월 2일 | 아르헨티나 훈장 | [555] | ||

| 마나스 훈장 | 2019년 6월 13일 | 키르기스스탄의 최상위 국가 | [556] | ||

| 관훈장 | 2019년 6월 15일 | 타지키스탄의 훈장 | [557] | ||

| 금독수리 훈장 | 2022년 9월 14일 | 카자흐스탄 최고위급 | [558] | ||

| 우정의 훈장 | 2022년 9월 15일 | 우즈베키스탄의 국가상 | [559] | ||

| 남아프리카 공화국 훈장 | 2023년 8월 22일 | 남아프리카 공화국의 행정 구역 | [560] | ||

도시의 열쇠

시 주석은 참석한 손님들에게 그들의 중요성을 상징하기 위해 수여되는 명예인 "도시로 가는 열쇠"를 가지고 있습니다.

미국 아이오와주 머스캐틴(Muscatine) (1985년 4월 26일)[561][562]

미국 아이오와주 머스캐틴(Muscatine) (1985년 4월 26일)[561][562] 자메이카 몬테고 만 (2009년 2월 13일)[48]

자메이카 몬테고 만 (2009년 2월 13일)[48]

미국 아이오와주 머스캐틴 (2012년 2월 14일)[561]

미국 아이오와주 머스캐틴 (2012년 2월 14일)[561]

산호세, 코스타리카 (2013년 6월 3일)[563]

산호세, 코스타리카 (2013년 6월 3일)[563]

멕시코시티 (2013년 6월 5일)[564]

멕시코시티 (2013년 6월 5일)[564]

아르헨티나 부에노스아이레스 (2014년 7월 19일)[565]

아르헨티나 부에노스아이레스 (2014년 7월 19일)[565]

체코 프라하 (2016년 3월 29일)[566]

체코 프라하 (2016년 3월 29일)[566]

스페인 마드리드 (2018년 11월 28일)[567]

스페인 마드리드 (2018년 11월 28일)[567]

명예박사학위 소지자

나자르바예프 대학교 (2013년 9월 7일)[568]

나자르바예프 대학교 (2013년 9월 7일)[568] 요하네스버그 대학교 (2019년 4월 11일)[569]

요하네스버그 대학교 (2019년 4월 11일)[569] 상트페테르부르크 주립 대학교 (2019년 6월 6일)[570]

상트페테르부르크 주립 대학교 (2019년 6월 6일)[570] 킹 사우드 대학교 (2022년 12월 8일)[571]

킹 사우드 대학교 (2022년 12월 8일)[571]

작동하다

- Xi, Jinping (1999). Theory and Practice on Modern Agriculture. Fuzhou: Fujian Education Press.

- Xi, Jinping (2001). A Tentative Study on China's Rural Marketization (PDF). Beijing: Tsinghua University (Doctoral Dissertation). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2013.

- Xi, Jinping (2007). Zhijiang Xinyu. Hangzhou: Zhengjiang People's Publishing House. ISBN 9787213035081.

- Xi, Jinping (2014). The Governance of China. Vol. I. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 9787119090573.

- Xi, Jinping (2014). General Secretary Xi Jinping important speech series. Vol. I. Beijing: People's Publishing House & Study Publishing House. ISBN 9787119090573.

- Xi, Jinping (2016). General Secretary Xi Jinping important speech series. Vol. II. Beijing: People's Publishing House & Study Publishing House. ISBN 9787514706284.

- Xi, Jinping (2017). The Governance of China. Vol. II. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 9787119111643.

- Xi, Jinping (2018). Quotations from Chairman Xi Jinping. Some units of the PLA.

- Xi, Jinping (2019). The Belt And Road Initiative. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 978-7119119960.

- Xi, Jinping (2020). The Governance of China. Vol. III. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 9787119124117.

- Xi, Jinping (2020). On Propaganda and Ideological Work of Communist Party. Beijing: Central Party Literature Press. ISBN 9787507347791.

- Xi, Jinping (2021). On History of the Communist Party of China. Beijing: Central Party Literature Press. ISBN 9787507348033.

- Xi, Jinping (2022). The Governance of China. Vol. IV. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 9787119130941.

메모들

- ^ 구어 영어에서 일반적인 소리만을 사용하는 가장 가까운 발음은 (영어: /ˈʃ ː t ʃɪ ˈp ɪŋ / SHEE chin-PING)입니다.

- ^ 류옌둥(劉延東), 왕치산(王oping山), 덩푸팡(덩샤오핑의 아들) 등이 대체 멤버 명단에서 하위권에 이름을 올렸습니다.시 주석처럼 세 사람 모두 '왕자'로 여겨졌습니다.보시라이는 중앙위원에 전혀 선출되지 않았습니다. 즉, 보시라이는 시 주석보다 낮은 득표율을 기록했습니다.

- ^ Original simplified Chinese: 在国际金融风暴中,中国能基本解决13亿人口吃饭的问题,已经是对全人类最伟大的贡献; traditional Chinese: 在國際金融風暴中,中國能基本解決13億人口吃飯的問題,已經是對全人類最偉大的貢獻

- ^ Original: simplified Chinese: 有些吃饱没事干的外国人,对我们的事情指手画脚。中国一不输出革命,二不输出饥饿和贫困,三不折腾你们,还有什么好说的?; traditional Chinese: 有些吃飽沒事干的外國人,對我們的事情指手畫腳。中國一不輸出革命,二不輸出飢餓和貧困,三不折騰你們,還有什麽好說的?

- ^ 중국어: "중국 민족의 대부흥" 또는 "중국 민족의 대부흥"으로 번역될 수 있는 中华民族伟大复兴.

참고문헌

인용

- ^ "Association for Conversation of Hong Kong Indigenous Languages Online Dictionary". hkilang.org. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han (23 May 2023). Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower Future. Simon and Schuster. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-9821-8575-6. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Profile: Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ 與丈夫習仲勛相伴58年 齊心:這輩子無比幸福 [With her husband Xi Zhongxun for 58 years: very happy in this life] (in Traditional Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Xu, Xinyi (27 May 2013). 習近平"家風"揭秘 齊心自述與習仲勛婚姻往事 [Xi Jinping's "family traditions" are unmasked: Qi Xin's autobiographical account of her marriage to Xi Zhongxun]. People's Daily (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Fangqin, Sun (16 November 2012). 本報獨家探訪河南鄧州習營村 [This Newspaper's Exclusive Visit To Xiying Village, Dengzhou County, Henan]. Wen Wei Po (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Takahashi, Tetsushi (1 June 2002). "Connecting the dots of the Hong Kong law and veneration of Xi". Nikkei Shimbun. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Osnos, Evan (30 March 2015). "Born Red". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Li, Cheng. "Xi Jinping's Inner Circle (Part 2: Friends from Xi's Formative Years)" (PDF). Hoover Institution. pp. 6–22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (29 December 2019). "The power behind the thrones: 10 political movers and shakers who will shape 2020". The Guardian. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Wei, Lingling (27 February 2018). "Who Is 'Uncle He?' The Man in Charge of China's Economy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ 부에 2010, 93쪽.

- ^ a b Buckley, Chris; Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (24 September 2015). "Cultural Revolution Shaped Xi Jinping, From Schoolboy to Survivor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ 不忘初心:是什么造就了今天的习主席? [What Were His Original Intentions? The President Xi of Today]. Youku (in Simplified Chinese). 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Lim, Louisa (9 November 2012). "For China's Rising Leader, A Cave Was Once Home". NPR. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Page, Jeremy (23 December 2020). "How the U.S. Misread China's Xi: Hoping for a Globalist, It Got an Autocrat". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Demick, Barbara; Pierson, David (14 February 2012). "China's political star Xi Jinping is a study in contrasts". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ Matt Rivers (19 March 2018). "This entire Chinese village is a shrine to Xi Jinping". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Xi Jinping 习近平" (PDF). Brookings Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ ""The Current" – Wednesday February 28, 2018 Full Text Transcript". CBC Radio. 28 February 2018. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Ranade, Jayadva (25 October 2010). "China's Next Chairman – Xi Jinping". Centre for Air Power Studies. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ 사이먼 & 콩 2009, 28-29쪽.

- ^ Johnson, Ian (30 September 2012). "Elite and Deft, Xi Aimed High Early in China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Xi Jinping: From graft-fighting governor to China's most powerful leader since Mao Zedong". The Straits Times. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "中共十五大习近平位列候补委员最后一名为何" 中共十五大习近平位列候补委员最后一名为何 [Why Is Xi Jinping, At the 15th CCP National Congress, Being Waited On To Fill The Last Committee Member Position?]. Canyu.org (in Simplified Chinese). 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ "Xi Jinping – Politburo Standing Committee member of CPC Central Committee". People's Daily. 22 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (26 October 2007). "Most corrupt officials are from poor families but Chinese royals have a spirit that is not dominated by money". The Guardian. London, England. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (4 November 2014). "From Fujian, China's Xi Offers Economic Olive Branch to Taiwan". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Yu, Xiao (18 February 2000). "Fujian leaders face Beijing top brass". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Ho, Louise (25 October 2012). "Xi Jinping's time in Zhejiang: doing the business". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Wang, Lei (25 December 2014). 习近平为官之道 拎着乌纱帽干事 [Xi Jinping's Governmental Path – Carries Official Administrative Posts]. Duowei News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Tian, Yew Lun; Chen, Laurie; Cash, Joe (11 March 2023). "Li Qiang, Xi confidant, takes reins as China's premier". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ 习近平任上海市委书记 韩正不再代理市委书记 [Xi Jinping is Secretary of Shanghai Municipal Party Committee – Han Zheng is No Longer Acting Party Secretary]. Sohu (in Simplified Chinese). 24 March 2007. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "China new leaders: Xi Jinping heads line-up for politburo". BBC News. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ 从上海到北京 习近平贴身秘书只有钟绍军 [From Shanghai to Beijing, Zhong Shaojun Has Been Xi Jinping's Only Personal Secretary]. Mingjing News (in Simplified Chinese). 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Lam 2015, 56쪽.

- ^ 新晋政治局常委:习近平 [Newly Appointed Member of Politburo Standing Committee: Xi Jinping]. Caijing (in Simplified Chinese). 22 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "Wen Jiabao re-elected China PM". Al Jazeera. 16 March 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Vice-President Xi Jinping to Visit DPRK, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Yemen". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Wines, Michael (9 March 2009). "China's Leaders See a Calendar Full of Anniversaries, and Trouble". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Anderlini, Jamil (20 July 2012). "Bo Xilai: power, death and politics". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Palmer, James (19 October 2017). "The Resistible Rise of Xi Jinping". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Ansfield, Jonathan (22 December 2007). "Xi Jinping: China's New Boss And The 'L' Word". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Elegant, Simon (19 November 2007). "China's Nelson Mandela". Time. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Elegant, Simon (15 March 2008). "China Appoints Xi Vice President, Heir Apparent to Hu". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Uren, David (5 October 2012). "Rudd seeks to pre-empt PM's China white paper with his own version". The Australian. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ "Chinese vice president arrives in Mexico for official visit". People's Daily. 10 February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Chinese VP Receives Key to the City of Montego Bay". Jamaica Information Service. 15 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Chinese vice president continues visit in Colombia". People's Daily. 17 February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Chinese VP praises friendly cooperation with Venezuela, Latin America". CCTV. Xinhua. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ "Xi Jinping proposes efforts to boost cooperation with Brazil". China Daily. 20 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Chinese vice president begins official visit". Times of Malta. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Sim, Chi Yin (14 February 2009). "Chinese VP blasts meddlesome foreigners". AsiaOne. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Lai, Jinhong (18 February 2009). 習近平出訪罵老外 外交部捏冷汗 [Xi Jinping Goes and Scolds at Foreigners, Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Cold Sweat]. United Daily News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ "A Journey of Friendship, Cooperation and Culture – Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Zhijun Sums Up Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping's Trip to 5 European Countries". Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations. 21 October 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Raman, B. (25 December 2009). "China's Cousin-Cousin Relations with Myanmar". South Asia Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Bull, Alister; Buckley, Chris (24 January 2012). "China leader-in-waiting Xi to visit White House next month". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (15 February 2012). "Xi Jinping of China Makes a Return Trip to Iowa". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Beech, Hannah (15 September 2012). "China's Heir Apparent Xi Jinping Reappears in Public After a Two-Week Absence". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ a b "China Confirms Leadership Change". BBC News. 17 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Xi Jinping: China's 'princeling' new leader". Hindustan Times. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Wong, Edward (14 November 2012). "Ending Congress, China Presents New Leadership Headed by Xi Jinping". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ FlorCruz, Jaime A; Mullen, Jethro (16 November 2012). "After months of mystery, China unveils new top leaders". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Ian (15 November 2012). "A Promise to Tackle China's Problems, but Few Hints of a Shift in Path". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Full text: China's new party chief Xi Jinping's speech". BBC News. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Page, Jeremy (13 March 2013). "New Beijing Leader's 'China Dream'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Chen, Zhuang (10 December 2012). "The symbolism of Xi Jinping's trip south". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (3 March 2013). "China's Xi Jinping formally assumes title of president". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "China's Xi Jinping hints at backing Sri Lanka against UN resolution". NDTV. Press Trust of India. 16 March 2013. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Cheung, Tony; Ho, Jolie (17 March 2013). "CY Leung to meet Xi Jinping in Beijing and explain cross-border policies". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "China names Xi Jinping as new president". Inquirer.net. Agence France-Presse. 15 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ People’s Daily, Department of Commentary (20 November 2019). "Stories of Incorrupt Government: "The Corruption and Unjustness of Officials Give Birth to the Decline of Governance"". Narrating China's Governance. Singapore: Springer Singapore. pp. 3–39. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9178-2_1. ISBN 978-981-329-177-5.

- ^ "習近平:不提不切實際的口號 - 快訊-文匯網". 香港文匯網. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Xi Jinping's inaugural Speech". BBC News. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (27 March 2013). "Elite in China Face Austerity Under Xi's Rule". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Oster, Shai (4 March 2014). "President Xi's Anti-Corruption Campaign Biggest Since Mao". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Heilmann 2017, 62–75쪽.

- ^ "China's Soft-Power Deficit Widens as Xi Tightens Screws Over Ideology". Brookings Institution. 5 December 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Charting China's 'great purge' under Xi". BBC News. 22 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Tiger in the net". The Economist. 11 December 2014. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "China's former military chief of staff jailed for life for corruption". The Guardian. 20 February 2019. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "China's anti-corruption campaign expands with new agency". BBC News. 20 March 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ a b "31个省级纪委改革方案获批复 12省已完成纪委"重建"" [31 Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection Reform Plans Approved 12 Provinces Have Completed "Reconstruction"]. Xinhua News Agency. 13 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Chin, Josh (15 December 2021). "Xi Jinping's Leadership Style: Micromanagement That Leaves Underlings Scrambling". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han (16 October 2022). "Xi Jinping's Quest for Control Over China Targets Even Old Friends". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "China re-connects: joining a deep-rooted past to a new world order". Jesus College, Cambridge. 19 March 2021. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Wang, Gungwu (7 September 2019). "Ancient past, modern ambitions: historian Wang Gungwu's new book on China's delicate balance". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (25 October 2017). "China's Xi Jinping unveils his top party leaders, with no successor in sight". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

Censorship has been significantly stepped up in China since Xi took power.

- ^ Economy, Elizabeth (29 June 2018). "The great firewall of China: Xi Jinping's internet shutdown". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

Before Xi Jinping, the internet was becoming a more vibrant political space for Chinese citizens. But today the country has the largest and most sophisticated online censorship operation in the world.

- ^ "Xi outlines blueprint to develop China's strength in cyberspace". Xinhua News Agency. 21 April 2018. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Zhuang, Pinghui (19 February 2016). "China's top party mouthpieces pledge 'absolute loyalty' as president makes rare visits to newsrooms". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2022.