저신다 아던

Jacinda Ardern데임 저신다 아던 | |

|---|---|

2018년 아던 | |

| 제40대 뉴질랜드 총리 | |

| 재직중 2017년 10월 26일 ~ 2023년 1월 25일 | |

| 모나크스 | |

| 총독부 | |

| 대리 | |

| 선행후 | 빌 잉글리시 |

| 성공한 사람 | 크리스 힙킨스 |

| 노동당 제17대 당수 | |

| 재직중 2017년 8월 1일 ~ 2023년 1월 22일 | |

| 대리 | 켈빈 데이비스 |

| 선행후 | 앤드류 리틀 |

| 성공한 사람 | 크리스 힙킨스 |

| 제36대 야당 지도자 | |

| 재직중 2017년 8월 1일 ~ 2017년 10월 26일 | |

| 대리 | 켈빈 데이비스 |

| 선행후 | 앤드류 리틀 |

| 성공한 사람 | 빌 잉글리시 |

| 노동당 제17기 부대표 | |

| 재직중 2017년 3월 7일 ~ 2017년 8월 1일 | |

| 지도자 | 앤드류 리틀 |

| 선행후 | 아네트 킹 |

| 성공한 사람 | 켈빈 데이비스 |

| 뉴질랜드 국회의원 알버트 산을 위하여 | |

| 재직중 2017년 3월 8일 ~ 2023년 4월 15일 | |

| 선행후 | 데이비드 시어러 |

| 성공한 사람 | 헬렌 화이트 |

| 다수 | 21,246 |

| 뉴질랜드 국회의원 노동당의 후보로 | |

| 재직중 2008년 11월 8일 ~ 2017년 3월 8일 | |

| 성공한 사람 | 레이먼드 후오 |

| 개인내역 | |

| 태어난 | 저신다 케이트 로렐 아던 1980년 7월 26일 해밀턴, 뉴질랜드 |

| 정당 | 노동 |

| 배우자. | (m. 2024) |

| 아이들. | 1 |

| 부모 |

|

| 모교 | 와이카토 대학교 |

| ||

|---|---|---|

총선 | ||

저신다 케이트 라우렐 [2]아던[1] GNZM(, 1980년 7월 26일 ~ )은 뉴질랜드의 전 정치인으로, 2017년부터 2023년까지 뉴질랜드의 제40대 총리와 노동당 대표를 역임했습니다. 그녀는 2008년부터 2017년까지 목록 의원으로, 2017년부터 2023년까지 앨버트 산의 의원으로 노동당 의원이었습니다.[3][4]

해밀턴에서 태어난 아던은 모린스빌과 무루파라에서 자랐습니다. 그녀는 17살에 노동당에 입당했습니다. 2001년 와이카토 대학을 졸업한 후, 아던 총리 헬렌 클라크의 사무실에서 연구원으로 일했습니다. 그녀는 나중에 토니 블레어의 총리 재임 기간 동안 내각부의 고문으로 런던에서 일했습니다. 2008년 아던은 국제사회주의청년연합의 회장으로 선출되었습니다. 아던 의원은 노동당이 9년 만에 정권을 잃었던 2008년 총선에서 처음으로 하원의원으로 선출되었습니다. 그녀는 이후 2017년 2월 25일 보궐선거에서 앨버트 산 유권자 대표로 선출되었습니다.

아던은 아네트 킹의 사임 이후 2017년 3월 1일 노동당의 부대표로 만장일치로 선출되었습니다. 정확히 5개월 후, 선거를 앞두고 노동당의 지도자인 앤드류 리틀은 당에 대한 역사적으로 낮은 여론 조사 결과 이후 사임했고, 아던은 그의 자리에서 반대 없이 지도자로 선출되었습니다.[5] 노동당의 지지는 아던이 지도자가 된 후 급격히 증가했으며, 그녀는 2017년 9월 23일 총선에서 46석을 얻어 국민당 56석을 차지하며 14석을 차지했습니다.[6] 협상 끝에 뉴질랜드 퍼스트는 녹색당의 지원을 받는 노동당과 함께 아던 총리를 총리로 하는 소수 연립정부에 들어가기로 결정했습니다. 그녀는 2017년 10월 26일에 총독에 의해 취임했습니다.[7] 그녀는 37세에 세계 최연소 여성 정부 수반이 되었습니다.[8] 아던은 2018년 6월 21일 딸을 출산하여 베나지르 부토에 이어 세계에서 두 번째로 당선된 정부 수반이 되었습니다.[9]

아던은 자신을 사회 민주주의자이자 진보주의자라고 표현합니다.[10][11] 제6차 노동당 정부는 뉴질랜드의 주택 위기, 아동 빈곤, 그리고 사회적 불평등으로부터 도전에 직면했습니다. 2019년 3월, 크라이스트처치 모스크 총격 사건의 여파로 아던은 엄격한 총기법을 빠르게 도입하여 폭넓은 인지도를 얻었습니다.[12] 2020년 한 해 동안 그녀는 COVID-19 팬데믹에 대한 뉴질랜드의 대응을 이끌었고, 뉴질랜드가 성공적으로 바이러스를 억제한 몇 안 되는 서구 국가 중 하나라는 찬사를 받았습니다.[13] 그녀의 정부의 행동이 무려 8만명의 목숨을 구한 것으로 추정됩니다.[14] 아던은 2020년 10월 총선을 앞두고 노동당을 중앙으로 더 나아가 코로나19 경기 침체의 남은 기간 동안 지출을 줄이겠다고 약속했습니다.[15] 그녀는 노동당을 압도적인 승리로 이끌었고, 의회에서 65석의 전체 과반을 차지했는데, 이는 1996년 비례대표제 도입 이후 처음으로 다수당 정부가 구성된 것입니다.[16][17][18]

2023년 1월 19일, 아던은 노동당 지도자직을 사임할 것이라고 발표했고, 그녀의 리더십 스타일과 정책 결정에 대해 대부분 긍정적인 세계적인 반응을 불러일으켰습니다.[19][20][21] 크리스 힙킨스를 그녀의 후임자로 반대 없이 선출한 후, 그녀는 1월 22일 노동당 당수직을 사임하고 1월 25일 총리직을 총독에게 제출했습니다.[22]

초기 생활과 교육

아던은 1980년 7월 26일 뉴질랜드 해밀턴에서 태어났습니다.[23] 그녀는 아버지 로스 아던(Ross Ardern)이 경찰관으로,[24] 어머니 라우렐 아던(Laurell Ardern, 성 바텀리)이 학교 급식 보조원으로 일했던 모린스빌(Morrinsville)과 무루파라(Murupara)에서 자랐습니다.[25][26] 그녀에게는 루이즈라는 이름의 언니가 있습니다.[27] 아던은 예수 그리스도 후기성도교회(LDS Church of Jesus Christ of Lattern-day Saints)에서 자랐고, 그녀의 삼촌인 이안 S. 아던은 교회의 일반적인 권위자입니다.[28][29] 그녀는 Morrinsville College에서 공부했고,[30] 그곳에서 그녀는 학교 이사회의 학생 대표였습니다.[31] 아직 학교에 있을 때 그녀는 첫 직장을 구했고, 지역의 피쉬 앤 칩 가게에서 일했습니다.[32]

그녀는 17살에 노동당에 입당했습니다.[33] 그녀의 숙모인 노동당의 오랜 당원인 마리 아던은 1999년 총선에서 뉴플리머스 하원의원 해리 듀이호벤의 재선 운동을 돕기 위해 10대 아던을 영입했습니다.[34]

아던은 와이카토 대학교에 입학하여 2001년에 정치 및 홍보 분야의 커뮤니케이션 학사로 졸업했으며, 3년제 전문 학위를 받았습니다.[35][36] 그녀는 2001년에 애리조나 주립 대학교에서 한 학기를 해외에서 공부했습니다.[37][38] 대학을 졸업한 후, 그녀는 연구원으로서 필 고프와 헬렌 클라크의 사무실에서 일하며 시간을 보냈습니다. 그녀는 수프 주방에서[39] 봉사활동을 하고 노동자 권리 운동을 하던 미국 뉴욕에서 잠시 지낸 후,[40] 2006년에 영국 런던으로 옮겨 [41]토니 블레어 총리 아래 영국 내각부의 80명 정책 부서에서 정책 고문이 되었습니다.[42] (그녀는 런던에 있는 동안 블레어를 직접 만나지는 않았지만, 2011년 뉴질랜드의 한 행사에서 2003년 이라크 침공에 대해 질문했습니다.)[41] 아던은 또한 영국 내무부에 차출되어 잉글랜드와 웨일즈의 치안 검토를 도왔습니다.[35][43]

초기 정치경력

국제사회주의청년연합회장

2008년 1월 30일, 27세의 나이로 도미니카 공화국에서 열린 세계 청소년 대회에서 국제사회주의청년연합(IUSY)의 회장으로 선출되었습니다.[44][45] 이 역할은 그녀가 헝가리, 요르단, 이스라엘, 알제리, 중국을 포함한 여러 나라에서 시간을 보내는 것을 보았습니다.[35] 아던 의원이 노동당의 후보가 된 것은 그녀의 대통령 임기 중반이었습니다. 그리고 나서 그녀는 그 후 15개월 동안 두 가지 역할을 모두 계속 관리했습니다.

국회의원

| 몇 해 | 용어 | 선거인단 | 목록. | 파티 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2011 | 제49회 | 목록. | 20 | 노동 | |

| 2011–2014 | 50번째 | 목록. | 13 | 노동 | |

| 2014–2017 | 51회 | 목록. | 5 | 노동 | |

| 2017 | 51회 | 앨버트 산 | 노동 | ||

| 2017–2020 | 제52회 | 앨버트 산 | 1 | 노동 | |

| 2020–2023 | 제53회 | 앨버트 산 | 1 | 노동 | |

2008년 선거를 앞두고 아던은 노동당 당적에서 20위에 올랐습니다. 이것은 이미 현직 의원이 아닌 사람에게는 매우 높은 자리였고, 사실상 그녀에게 의회 의석을 보장했습니다. 이에 따라 아던은 런던에서 돌아와 풀타임 캠페인을 벌였습니다.[46] 그녀는 또한 안전한 와이카토의 국민 선거를 위해 노동당의 후보가 되었습니다. 아던은 유권자 투표에서 실패했지만, 노동당 목록에서 그녀의 높은 위치는 그녀가 의회의 목록 의원으로 들어갈 수 있도록 해주었습니다.[47] 당선되자마자, 그녀는 동료 노동당 의원 대런 휴즈의 뒤를 이어 최연소 현직 의원이 되었고, 2010년 2월 11일 가레스 휴즈가 선출될 때까지 최연소 의원으로 남아있었습니다.[48]

야당 지도자 필 고프는 아던을 앞 벤치로 승진시켰고, 그녀의 노동당 청년 담당 대변인과 정의 담당 부대변인으로 임명했습니다.[49]

그녀는 TVNZ의 아침 식사 프로그램에 정기적으로 출연했는데, 그녀는 국회의원(그리고 미래의 국가 지도자) 사이먼 브리지스와 함께 출연했습니다.[50]

아던은 2011년 총선에서 현직 국민당 의원 니키 케이와 녹색당 후보 데니스 로슈에 맞서 오클랜드 노동당 중앙당 의원직에 도전했습니다. 그녀는 케이에게 717표 차이로 졌습니다. 그러나 그녀는 13위에 오른 당 명단을 통해 의회에 복귀했습니다.[51] 아던은 오클랜드 센트럴에 기반을 둔 하원의원으로 활동하는 동안 유권자 내에서 사무실을 유지했습니다.[52]

2011년 선거에서 패배한 고프가 당 지도부에서 물러난 후, 아던은 데이비드 시어러를 데이비드 컨리프보다 지지했습니다. 그녀는 2011년 12월 19일 그림자 내각에서 4위로 승진하여 새 지도자 밑에서 사회 발전 대변인이 되었습니다.[49]

아던은 2014년 총선에서 오클랜드 센트럴에 다시 섰습니다. 그녀는 자신의 표를 늘리고 케이의 과반수를 717표에서 600표로 줄였지만 다시 2위를 차지했습니다.[53] 노동당의 목록에서 5위를 차지한 아던은 여전히 의회에 복귀하여 새로운 지도자 앤드류 리틀 아래에서 정의, 아동, 소기업 및 예술 & 문화의 그림자 대변인이 되었습니다.[54]

2014년 아던은 스위스에서 열리는 클라우스 슈밥([55]Klaus Schwab)이 설립한 세계경제포럼(WEF)의 젊은 글로벌 리더 포럼(Forum of Young Global Leaders)에 선발되어 참석하고 졸업했습니다. 그녀는 젊은 글로벌 리더 동문 커뮤니티의 일원으로 여전히 공개적으로 참여하고 있으며,[56] WEF 행사에서 연설하고 있습니다.

앨버트 산 보궐선거

아던은 2016년 12월 8일 데이비드 시어러가 사임한 후 2017년[57] 2월에 실시될 마운트 앨버트 보궐 선거를 위한 노동당 지명에 자신의 이름을 올렸습니다. 2017년 1월 12일 노동당 후보 지명이 마감되었을 때 아던은 유일한 후보였으며 반대 없이 선택되었습니다. 1월 21일, 아던은 미국의 새로 취임한 대통령인 도널드 트럼프에 반대하는 세계적인 시위인 2017 여성 행진에 참여했습니다.[58] 그녀는 1월 22일 회의에서 노동당 후보로 확정되었습니다.[59][60] 아던 후보는 결선 투표에서 77%의 득표율을 기록하며 압승을 거뒀습니다.[61][62]

노동당 부대표

보궐선거에서 승리한 아던은 다음 선거에서 은퇴할 예정이었던 아네트 킹의 사임에 따라 2017년 3월 7일 노동당의 부대표로 만장일치로 선출되었습니다.[63] 아던의 빈자리는 레이먼드 후가 차지했습니다.[64]

야당 지도자

2017년 8월 1일, 2017년 총선을 불과 7주 앞두고, 아던은 노동당 당수직을 맡았고, 앤드루 리틀의 사임에 따라, 결과적으로 야당 당수가 되었습니다. 역사적으로 낮은 투표율로 인해 거의 물러나지 않았습니다.[65] 아던은 같은 날 열린 코커스 회의에서 새 지도자를 뽑는 선거에서 만장일치로 당선이 확정됐습니다.[66] 37세의 나이로 아던은 노동당 역사상 최연소 지도자가 되었습니다.[67] 그녀는 헬렌 클라크에 이어 두 번째 여성 당수이기도 합니다.[68] 아던에 따르면 리틀은 이전에 7월 26일에 그녀에게 접근하여 그녀가 노동당 대표를 맡아야 한다고 생각했다고 말했습니다. 아던이 거절하고 "그걸 고수하라"고 말했지만, 그는 당을 위해 상황을 되돌릴 수 없다고 생각했기 때문입니다.[69]

그녀는 지도자로 선출된 후 첫 기자 회견에서 다가오는 선거 운동은 "끊임없는 긍정" 중 하나가 될 것이라고 말했습니다.[33] 그녀가 임명된 직후, 파티는 대중의 기부로 넘쳐났고, 분당 700 뉴질랜드 달러에 달했습니다.[70] 아던이 지도부에 오른 후, 노동당은 여론조사에서 극적으로 상승했습니다. 8월 말까지 콜마 브런턴 여론조사에서 43%를 기록했고(리틀의 지도력 아래 24%), 여론조사에서 10여 년 만에 처음으로 전국을 앞질렀습니다.[69] 반대론자들은 그녀의 입장이 앤드류 리틀의 입장과 상당히 비슷하다는 것을 관찰했고, 노동당의 인기가 갑자기 높아진 것은 그녀의 젊고 잘생긴 외모 때문이라고 제안했습니다.[67]

8월 중순, 아던은 노동당 정부가 양도소득세 도입 가능성을 모색하기 위해 세금 워킹 그룹을 설립할 것이라고 말했지만, 가족 주택에 세금을 부과하는 것은 배제했습니다.[71][72] 부정적인 홍보에 대응하기 위해, 아던은 노동당 정부의 첫 번째 임기 동안 양도소득세 도입 계획을 포기했습니다.[73][74] 그랜트 로버트슨 재무 대변인은 이후 노동당이 2020년 선거 이후까지 새로운 세금을 도입하지 않을 것임을 분명히 했습니다. 이번 정책 전환은 노동당이 조세 정책에 117억 달러의 '구멍'을 가지고 있다는 스티븐 조이스 재무장관의 강력한 주장을 수반했습니다.[75][76]

노동당과 녹색당이 제안한 수도세와 오염세도 농민들의 비판을 불러일으켰습니다. 2017년 9월 18일, 농업 로비 단체인 Federated Farmers는 아던의 고향인 Morrinsville에서 세금에 반대하는 시위를 벌였습니다. 뉴질랜드의 초대 지도자 윈스턴 피터스는 캠페인을 하기 위해 시위에 참석했지만 그가 세금에도 찬성한다고 의심했기 때문에 농부들로부터 야유를 받았습니다. 시위가 진행되는 동안 한 농부는 아던을 "예쁜 공산주의자"라고 부르는 표지판을 보여주었습니다. 이는 헬렌 클라크 전 총리에 의해 여성 혐오라고 비판받았습니다.[77][78]

총선 막바지에는 전국이 근소한 차이로 앞서며 여론조사가 좁혀졌습니다.[79]

2017년 총선

2017년 9월 23일 치러진 총선에서 아던은 15,264표 차이로 앨버트 산 선거인단의 자리를 지켰습니다.[80][81][82] 노동당은 득표율을 36.89%로 높였고, 전국은 44.45%로 다시 하락했습니다. 노동당은 14석을 얻어 의회 대표성을 46석으로 늘렸으며, 이는 2008년 정권을 잃은 이후 당에 가장 좋은 결과입니다.[83]

경쟁 정당인 노동당과 국민당은 단독으로 집권하기에 충분한 의석을 확보하지 못했고, 녹색당과 뉴질랜드 제1당과 연정 구성을 위한 회담을 가졌습니다. 뉴질랜드의 혼합 구성원 비례 (MMP) 투표 제도 하에서 뉴질랜드 퍼스트는 권력의 균형을 유지하고 노동당과 연립 정부의 일부가 되기로 선택했습니다.[84][85]

국무총리 (2017년 ~ 2023년)

| |

| 저신다 아던 총리 2017년 10월 26일 ~ 2023년 1월 25일 | |

| 모나크스 | 엘리자베스 2세 샤를 3세 |

|---|---|

| 내각 | 뉴질랜드 제6노동당 정부 |

| 파티 | 뉴질랜드 노동당 |

| 선거 | 2017, 2020 |

| 임명자 | 팻시 레디 |

| | |

1기(2017년~2020년)

2017년 10월 19일, 뉴질랜드 제1 지도자 윈스턴 피터스는 노동당과 연립정부를 구성하기로 합의하여 [7]아던을 차기 총리로 임명했습니다.[86][87] 이 연합은 녹색당으로부터 신뢰와 공급을 받았습니다.[88] 아던은 피터스를 부총리 겸 외교부 장관으로 임명했습니다. 그녀는 또한 뉴질랜드에 그녀의 정부에서 피터스와 다른 세 명의 장관들이 내각에서 일하는 가운데 처음 다섯 자리를 맡았습니다.[89][90] 다음 날, 아던 총리는 야당 지도자로서 자신이 맡았던 그림자 직책을 반영하여 국가 안보 및 정보, 예술, 문화 및 유산, 취약계층 아동의 장관직을 맡을 것이라고 확정했습니다.[91] 그녀의 취약계층 아동부 장관직은 후에 아동 빈곤 감소부 장관직으로 대체되었고, 뉴질랜드의 First MP Tracey Martin은 아동부 장관직을 맡았습니다.[92] 그녀는 10월 26일에 그녀의 부처와 함께 Dame Patsy Reddy 총독에 의해 공식적으로 취임했습니다.[93] 취임하자마자 아던 총리는 자신의 정부가 "집중하고, 공감하며, 강력할 것"이라고 말했습니다.[94]

아던 총리는 제니 쉬플리 (1997–1999), 헬렌 클라크 (1999–2008)에 이어 뉴질랜드의 세 번째 여성 총리입니다.[95][96] 그녀는 여성 세계 지도자 위원회의 회원입니다.[97] 37세에 취임한 아던은 1856년 에드워드 스태퍼드(Edward Stafford)[98] 이후 최연소로 뉴질랜드 정부 수반이 된 인물이기도 합니다. 2018년 1월 19일, 아던은 그녀가 임신했고, 윈스턴 피터스가 출산 후 6주 동안 총리 대행을 맡을 것이라고 발표했습니다.[99] 딸을 출산한 후 2018년 6월 21일부터 8월 2일까지 출산휴가를 받았습니다.[100][101][102]

가사

아던은 10년 안에 뉴질랜드의 아동 빈곤을 절반으로 줄이겠다고 약속했습니다.[103] 2018년 7월, 아던은 그녀의 정부의 대표적인 가족 패키지의 시작을 발표했습니다.[104] 이 패키지는 그 조항 중 유급 육아휴직을 26주로 점차 늘리고, 어린 자녀를 둔 저소득층과 중산층 가정을 위해 주당 60달러의 보편적인 Best Start Payment를 도입했습니다. 가족세액공제, 고아급여, 숙박보조금, 위탁양육수당 등도 대폭 늘렸습니다.[105] 2019년, 정부는 아동 빈곤 감소를 지원하기 위해 학교 급식 시범 프로그램을 시작했습니다. 그리고 나서 이 프로그램은 낮은 10분위 학교의 200,000명(학업 등록의 약 25%)의 아동을 지원하기 위해 확장되었습니다.[106] 빈곤을 줄이기 위한 다른 노력에는 주요 복지 혜택의 증가,[107] 무료 의사 방문 확대, 학교에서[108] 생리 위생 용품을 무료로 제공하고 주 주택 재고를 추가하는 것이 포함되었습니다.[109]

그러나 2022년 현재 비판론자들은 주거 비용 상승이 가족을 계속 취약하게 만들고 있으며 이익이 지속되도록 하기 위해 시스템 변화가 필요하다고 말합니다.[110]

경제적으로 아던 정부는 최저임금을[111] 꾸준히 인상하고 지방성장기금을 도입해 농촌 인프라 사업에 투자하고 있습니다.[112] 한나라당이 계획했던 감세안은 취소되었고 대신 의료와 교육에 대한 지출을 우선하겠다고 밝혔습니다.[113] 고등교육 1년차는 2018년 1월 1일부터 무상으로 실시되었으며, 쟁의행위 이후 정부는 2021년까지 초등교사 급여를 12.8%(초임교사), 18.5%(다른 책임이 없는 수석교사) 인상하기로 합의했습니다.[114]

노동당이 지난 세 번의 선거를 위해 양도소득세 캠페인을 벌였음에도 불구하고, 아던은 2019년 4월 정부가 그녀의 지도 아래 양도소득세를 시행하지 않을 것이라고 약속했습니다.[115][116] 그러나 그 이후로 판매된 임대 부동산에 대한 양도 소득이 과세되는 기간은 구매 후 5년에서 10년으로 증가했습니다.[117]

아던은 2018년 매년 열리는 와이탕기의 날 기념 행사를 위해 와이탕기로 여행을 갔습니다. 이는 전례 없는 길이인 5일 동안 와이탕기에 머물렀습니다.[118] 아던 총리는 최고 지도자로부터 연설한 최초의 여성 총리가 되었습니다. 그녀의 방문은 마오리족 지도자들에 의해 대체로 호평을 받았으며, 논평가들은 그녀의 전임자들 중 몇몇이 받았던 신랄한 반응과 극명한 대조를 보였다고 언급했습니다.[118][119]

2018년 8월 24일, 아던 방송부 장관 클레어 커런이 의회 업무 외 방송사와의 만남을 공개하지 않아 이해충돌로 판단되자 내각에서 해임되었습니다. 쿠란은 내각 밖의 장관으로 남아 있었고, 아던은 쿠란을 그녀의 포트폴리오에서 해임하지 않은 것에 대해 야당으로부터 비판을 받았습니다. 아던은 이후 커란의 사표를 수리했습니다.[120][121] 2019년, 그녀는 노동당 직원에 대한 성폭행 혐의를 처리하여 비판을 받았습니다. 아던은 사건에 대한 보고서가 스핀오프에 실리기 전에 성폭행이나 폭력이 관련되지 않았다는 말을 들었다고 말했습니다.[122] 언론은 그녀의 계정에 의문을 제기했고, 한 기자는 아던의 주장이 "삼키기 어렵다"고 말했습니다.[123][124]

아던은 뉴질랜드에서 대마초를 사용하는 사람들을 범죄화하는 것에 반대하며, 이 문제에 대한 국민투표를 실시하겠다고 약속했습니다.[125] 2020년 10월 17일 2020년 총선과 함께 대마초 합법화를 위한 구속력 없는 국민투표가 실시되었습니다. 아던은 선거 전 TV 토론에서 과거 대마초 사용 사실을 인정했습니다.[126] 국민투표에서 유권자들은 대마초 합법화 및 통제 법안을 51.17% 부결시켰습니다.[127] 의학 저널에 게재된 회고적 기사는 아던이 공개적으로 '예스' 캠페인을 지지하지 않은 것이 "좁은 패배에 결정적인 요인이 되었을 수 있다"고 제안했습니다.[128]

2020년 9월, 아던은 그녀의 정부가 고등 교육을 등록금 없이 만들려는 계획을 포기했다고 발표했습니다.[129]

외사

2017년 11월 5일, 아던은 호주로 첫 공식 해외 여행을 떠났고, 그곳에서 호주 총리 말콤 턴불(Malcolm Turnbull)을 처음으로 만났습니다. 호주가 자국에 거주하는 뉴질랜드인들에 대한 대우 때문에 양국 간의 관계는 이전 몇 달 동안 경색되어 왔으며, 취임 직전 아던은 이 상황을 시정하고 호주 정부와 더 나은 협력 관계를 발전시킬 필요성을 언급했습니다.[130] 턴불은 그 만남을 우호적인 말로 표현했습니다: "우리는 서로를 신뢰합니다...우리가 서로 다른 정치적 전통 출신이라는 사실은 무관합니다."[131] 2020년, 아던은 호주의 뉴질랜드인 추방 정책을 비판했습니다. 그들 중 많은 사람들이 호주에 살았지만 호주 시민권을 취득하지 못한 뉴질랜드인들은 "부식적"이고 호주에 피해를 입혔습니다.뉴질랜드 관계.[132][133][134]

아던은 베트남에서 열린 2017년 APEC 정상회의,[135] 런던에서 열린 영연방 정부 수반 회의(Elizabeth II Queen과 함께 비공개로 참석),[136] 뉴욕에서 열린 유엔 정상회의에 참석했습니다. 도널드 트럼프와의 첫 공식 회담 후 그녀는 미국 대통령이 뉴질랜드의 총기 구매 프로그램에 "관심"을 보였다고 보고했습니다.[137][138] 2018년 아던은 중국의 위구르 무슬림 소수민족에 대한 신장 수용소와 인권 유린 문제를 제기했습니다.[139][140] 아던은 미얀마에서 로힝야족 이슬람교도들에 대한 박해에 대한 우려도 제기했습니다.[141]

아던은 2018 태평양 섬 포럼에 참석한 나우루로 여행을 갔습니다. 언론과 정치적 반대자들은 그녀가 딸과 더 많은 시간을 보낼 수 있도록 그녀의 나머지 파견대와 별도로 여행하기로 한 결정을 비난했습니다.[142] 2018년 유엔 총회에서 아던은 갓난아기를 배석시킨 채 참석한 최초의 여성 정부 수반이 되었습니다.[143][144] 총회 연설에서 그녀는 유엔의 다자주의를 칭찬하고, 세계의 젊은이들에 대한 지지를 표명하고, 기후 변화의 영향과 원인에 대한 즉각적인 관심을 촉구하고, 여성의 평등과 행동의 기초로서의 친절을 촉구했습니다.[145]

데이비드 파커 무역수출성장부 장관과 아던 장관은 녹색당의 반대에도 불구하고 환태평양경제동반자협정 협상에 정부가 계속 참여할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[146] 뉴질랜드는 수정된 협정인 환태평양경제동반자협정을 비준했는데,[147] 그녀는 이 협정이 원래의 TPP 협정보다 더 낫다고 묘사했습니다.[148]

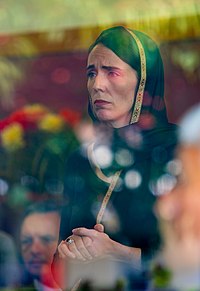

크라이스트처치 이슬람 사원 총격 사건

2019년 3월 15일 크라이스트처치의 이슬람 사원 2곳에서 51명이 총에 맞고 49명이 다쳤습니다. 텔레비전으로 방송된 성명에서 아던은 애도를 표하며 뉴질랜드나 세계 어디에도 갈 곳이 없는 "극단적인 견해"를 가진 용의자들이 총격을 가했다고 말했습니다.[151] 그녀는 또한 그것을 잘 계획된 테러 공격이라고 설명했습니다.[152]

국가 애도 기간을 발표하면서 아던은 수도 웰링턴에서 연 국가 애도 책의 첫 서명자였습니다.[153] 그녀는 또한 응급 구조대원과 희생자 가족들을 만나기 위해 크라이스트처치로 이동했습니다.[154] 의회 연설에서 그녀는 절대 공격자의 이름을 말하지 않겠다고 선언했습니다: "그들을 빼앗은 사람의 이름보다 잃어버린 사람의 이름을 말하라... 내가 말할 때, 그는 이름을 밝히지 않을 것입니다."[155] 아던은 총격 사건에 대한 대응으로 국제적인 찬사를 받았고,[156][157][158][159] 그녀가 세계 최고층 빌딩인 부르즈 할리파에 영어와 아랍어로 "평화"라는 단어와 함께 크라이스트처치 무슬림 공동체의 한 구성원을 껴안고 있는 사진이 투영되었습니다.[160] 이 사진의 25미터(82피트) 벽화는 2019년 5월에 공개되었습니다.[161]

총격 사건에 대한 대응으로, 아던은 더 강력한 총기 규제를 도입하겠다는 정부의 의도를 발표했습니다.[162] 그녀는 이번 공격으로 뉴질랜드 총기법의 여러 가지 약점이 드러났다고 말했습니다.[163] 공격이 있은 지 한 달도 안 되어 뉴질랜드 의회는 대부분의 반자동 무기와 공격용 소총, 총기를 반자동 총기로 바꾸는 부품, 그리고 더 높은 용량의 탄창을 금지하는 법을 통과시켰습니다.[164] 아던과 에마뉘엘 마크롱 프랑스 대통령은 "테러와 폭력적 극단주의를 조직하고 촉진하기 위해 소셜 미디어를 사용하는 능력을 종식시키기 위한 시도로 국가와 기술 회사를 하나로 모으는 것"을 목표로 하는 2019 크라이스트처치 콜 정상회담을 공동 의장했습니다.[165]

코로나19 범유행

2020년 3월 14일, 아던은 뉴질랜드의 COVID-19 대유행에 대응하여 정부가 3월 15일 0시부터 입국하는 모든 사람에게 14일 동안 자가 격리를 요구할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[166] 그녀는 새로운 규칙이 뉴질랜드가 "세계 어느 나라보다도 광범위하고 엄격한 국경 제한"을 가지고 있다는 것을 의미할 것이라고 말했습니다.[167] 3월 19일, 아던은 뉴질랜드의 국경이 3월 20일 오후 11시 59분(NZDT) 이후 모든 비시민 및 비영주 거주자에게 폐쇄될 것이라고 말했습니다.[168] 아던은 뉴질랜드가 25일 오후 11시 59분 전국 봉쇄령을 포함해 경보 4단계로 이동한다고 발표했습니다.[169]

국내외 언론들은 아던이 이끄는 정부의 대응을 다루며, 그녀의 리더십과 뉴질랜드에서의 발병에 대한 신속한 대응을 칭찬했습니다.[170][171] 워싱턴 포스트의 피필드는 그녀가 인터뷰, 기자 회견, 소셜 미디어를 정기적으로 사용하는 것을 "위기 소통의 달인"이라고 묘사했습니다.[172] 토니 블레어 영국 정부의 언론인이자 고문인 알라스테어 캠벨은 아던이 코로나바이러스 팬데믹으로 인한 인적, 경제적 결과를 모두 해결했다고 칭찬했습니다.[173]

2020년 4월 중순, 두 명의 신청자는 코로나19 팬데믹의 결과로 부과된 봉쇄 조치가 그들의 자유를 침해하고 "정치적 이익"을 위해 이루어졌다며 아던과 애슐리 블룸필드 보건부 국장을 포함한 몇몇 정부 관리들을 상대로 소송을 제기했습니다. 이 소송은 오클랜드 고등법원의 메리 피터스 판사에 의해 기각되었습니다.[174][175]

2020년 5월 5일, 아던과 그녀의 호주 상대인 스콧 모리슨, 그리고 몇몇 호주 주 및 영토 지도자들은 코로나바이러스 제한을 완화하기 위한 노력의 일환으로 양국 주민들이 여행 제한 없이 자유롭게 여행할 수 있는 태즈먼 횡단 코로나 안전 여행 구역을 개발하기 위해 협력하기로 합의했습니다.[176][177]

봉쇄 후 여론조사 결과 노동당이 60% 가까이 지지한 것으로 나타났습니다.[178][179] 2020년 5월, 아던은 뉴스허브-리드 리서치 여론조사에서 59.5%를 '선호하는 총리'로 평가했는데, 이는 리드 리서치 여론조사 역사상 가장 높은 점수입니다.[180][181] 아던이 창을 들고 달려온 반응에 의해 구조된 생명의 수는 숀 헨디(Shaun Hendy)가 이끄는 팀에 의해 최대 80,000명으로 추정되었습니다.[14]

2기(2020년~2023년)

2020년 총선에서 아던은 120석의 하원에서 65석의 전체 과반을 차지하고 전국 정당 투표의 50%를 차지하며 [182]압도적인 승리를 이끌었습니다(72명의 선거인단 중 71명에서 노동당보다 더 많은 사람들이 당 투표에서 이겼습니다).[183][184] 그녀는 또한 21,246표 차이로 앨버트 산 선거인단을 유지했습니다.[185] 아던은 그녀의 승리가 코로나19 팬데믹에 대한 정부의 대응과 그것이 미친 경제적 영향 덕분이라고 말했습니다.[186]

가사

2020년 12월 2일 아던은 뉴질랜드에 기후변화 비상사태를 선포하고 의회 동의안에서 2025년까지 정부가 탄소 중립을 하겠다고 약속했습니다. 이러한 탄소중립에 대한 약속의 일환으로 공공부문은 전기차나 하이브리드차만 구입하도록 의무화하고, 시간이 지남에 따라 차량을 20% 감축하며, 공공서비스 건물의 석탄화력 보일러 200대를 모두 단계적으로 폐지할 계획입니다. 이 동의안은 노동당, 녹색당, 마오리당은 지지했지만 야당인 국민당과 ACT당은 반대했습니다.[187][188] 하지만, 기후 운동가 그레타 툰베리는 아던에 대해 이렇게 말했습니다: "사람들이 저신다 아던과 그런 사람들이 기후 지도자라고 믿는 것은 재미있습니다. 그것은 단지 사람들이 기후 위기에 대해 얼마나 적게 알고 있는지를 말해줍니다. 배출량은 떨어지지 않았습니다."[189]

악화되는 주택 가격 문제에 대응하여, 주택 도시 개발부 장관 메간 우즈는 새로운 개혁을 발표했습니다. 이러한 개혁에는 이자율 세금 공제 철폐, 첫 주택 구매자에 대한 주택 지원 해제, 구의회를 위한 인프라 펀드(이름은 주택 가속화 펀드)의 갱신 할당, 브라이트 라인 테스트(Bright Line Test)를 5년에서 10년으로 연장하는 것이 포함되었습니다.[190][191]

2021년 6월 14일, 아던은 뉴질랜드 정부가 2021년 6월 26일 오클랜드 시청에서 던 레이즈에 대해 공식적으로 사과할 것이라고 확인했습니다. 던 레이드(Dawn Raids)는 1970년대와 1980년대 초 뉴질랜드의 파시피카 디아스포라(Pasifika Diaspia)의 구성원들을 불균형적으로 표적으로 삼은 일련의 경찰 급습이었습니다.[192][193]

2022년 9월, 아던은 뉴질랜드에서 가장 오래 통치한 군주인 엘리자베스 2세 여왕이 사망한 후 국가의 헌사를 이끌었습니다. 아던은 그녀를 "믿을 수 없는 여성"이자 "우리 삶의 상수"라고 묘사했습니다.[194] 그녀는 또한 여왕을 "매우 존경받고 존경받는" 군주로 묘사했습니다.[195] 아던은 또한 공화주의는 현재 의제에 포함되어 있지 않지만 앞으로 국가가 그러한 방향으로 나아갈 것이라고 믿었다고 말했습니다.[196]

2022년 12월 중순, 아던은 의회 질의 시간에 ACT당 대표인 데이비드 시모어를 "오만한 찌르기"라고 부르는 핫마이크에 녹화되었습니다. 뉴질랜드 의회 토론회는 TV로 중계되기 때문에 질문 시간에 텔레비전으로 중계되었습니다. 아던은 나중에 시모어에게 그녀의 발언에 대해 사과하라고 문자를 보냈습니다.[197][198] 이후 두 정치인은 화해하고 힘을 합쳐 총리의 발언을 담은 서명된 액자를 경매에 부쳐 전립선암 재단을 위해 6만 뉴질랜드 달러를 모금했습니다.[199]

코로나19 및 예방접종 프로그램

2020년 6월 17일, 아던 총리는 빌 게이츠가 요청한 회의에서 전화 회의를 통해 빌 게이츠와 멜린다 게이츠를 만났습니다. 회의에서 아던은 멜린다 게이츠로부터 코로나19 백신에 대한 집단적 접근을 지지하는 "목소리를 내야 한다"는 요청을 받았습니다. 아던은 기꺼이 도울 것이라고 공식 정보법 요청 답변을 통해 밝혔습니다. 아던 정부는 한 달 전인 지난 5월 빌 앤드 멜린다 게이츠 재단과 세계경제포럼 등이 설립한 CEPI(유행 대비 혁신을 위한 연합)에 1,500만 달러를 포함한 코로나19 백신 발굴을 돕기 위해 3,700만 달러를 약속한 바 있습니다. 그리고 또한 빌과 멜린다 게이츠 재단이 설립한 GAVI(Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunization)에 700만 달러를 기부했습니다. 회의에서 게이츠는 이 기여를 언급했습니다.[200] 아던은 또한 작년에 뉴욕에서 게이츠 부부를 만난 적이 있습니다.[201]

2020년 12월 12일, 아던과 쿡 제도의 마크 브라운 총리는 2021년 뉴질랜드와 쿡 제도 간의 여행 버블이 형성되어 양국 간의 양방향 검역 없는 여행이 가능할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[202] 12월 14일, 아던 총리는 뉴질랜드와 호주 정부가 다음 해에 두 나라 사이에 여행 거품을 조성하기로 합의했다고 확인했습니다.[203] 12월 17일, 아던은 또한 정부가 화이자/바이오의 기존 주식 외에 뉴질랜드와 태평양 파트너를 위해 제약사인 아스트라제네카와 노바백스로부터 2개의 백신을 추가로 구매했다고 발표했습니다.엔텍과 얀센 파마슈티카.[204]

2021년 1월 26일, 아던은 뉴질랜드 시민들이 "백신을 맞고 보호"될 때까지 뉴질랜드 국경은 대부분의 비시민과 비거주자들에게 폐쇄될 것이라고 말했습니다.[205] 코로나19 예방접종 프로그램은 2021년 2월부터 시작되었습니다.[206] 2021년 8월 SARS-CoV-2 델타 변종이 발생하면서 정부는 다시 전국적인 봉쇄령을 제정했습니다.[207] 9월까지 새로운 지역사회 감염자 수는 다시 감소하기 시작했습니다. 델타 변종 발병을 동시에 억제할 수 없었던 이웃 호주의 발병과 비교했습니다.[208]

2022년 1월 29일, 아던은 1월 22일 케리케리에서 오클랜드로 가는 에어 뉴질랜드 항공편에서 코로나19 환자의 밀접 접촉자로 확인되어 자가 격리에 들어갔습니다. 또 같은 항공편에 탑승했던 신디 키로 주지사와 앤드루 캠벨 공보수석도 자가 격리에 들어갔습니다.[209]

2022년 5월 14일, 아던은 코로나19 양성 반응을 보였습니다.[210] 그녀의 파트너 게이포드는 며칠 전인 5월 8일 코로나19 양성 판정을 받았습니다.[211]

외사

2020년 12월 초, 아던은 캔버라와 베이징 사이에 호주가 아프간인들을 상대로 전쟁 범죄를 저질렀다는 중국 외교부 관리 자오리젠의 트위터 게시물을 놓고 분쟁을 벌이는 동안 호주에 대한 지지를 표명했습니다. 그녀는 이 이미지가 사실적이지 않고 부정확하다고 묘사하면서 뉴질랜드 정부가 중국 정부에 우려를 제기할 것이라고 덧붙였습니다.[212][213]

2020년 12월 9일, 아던은 싱가포르 핀테크 페스티벌에서 가상으로 연설을 하며 뉴질랜드, 칠레, 싱가포르 간의 디지털 경제 파트너십 협정(DEPA)이 비즈니스 촉진을 위한 규제 정렬을 달성하기 위한 "첫 번째 중요한 단계"라고 박수를 보냈습니다.[214]

2021년 2월 16일, 아던은 호주 정부의 이중 뉴질랜드 취소 결정을 비판했습니다.호주 국적의 수하이라 아덴의 호주 시민권. 아덴은 여섯 살 때 뉴질랜드에서 호주로 이주하여 호주 시민권을 취득했습니다. 그녀는 그 후 2014년 ISIS 신부로서 이슬람 국가에서 살기 위해 시리아로 여행했습니다. 2021년 2월 15일, 아덴과 그녀의 자녀 2명은 터키 당국에 의해 불법 입국으로 구금되었습니다. 아던은 호주 정부가 자국민에 대한 의무를 포기했다고 비난했고 아덴과 그녀의 자녀들에게도 영사 지원을 제공했습니다. 이에 대해 스콧 모리슨 호주 총리는 아덴의 시민권을 취소하기로 한 결정을 옹호하면서 이중국적자들이 테러 활동을 할 경우 호주 시민권을 박탈하는 법안을 발의했다고 말했습니다.[215][216][217] 전화 통화 후, 두 정상은 아던 총리가 "매우 복잡한 법적 상황"이라고 표현한 것을 해결하기 위해 함께 노력하기로 합의했습니다.[218]

2021년 이스라엘-팔레스타인 위기에 대한 대응으로, 아던은 5월 17일 뉴질랜드가 "우리가 하마스로부터 본 무차별 로켓포 공격과 양측의 자기 방어를 훨씬 넘어선 대응으로 보이는 것을 비난한다"고 말했습니다. 그녀는 또한 이스라엘이 "존립할 권리"가 있지만 팔레스타인인들도 "평화로운 집, 안전한 집에 대한 권리"가 있다고 말했습니다.[219]

2021년 5월 말, 아던 총리는 퀸스타운에서 스콧 모리슨 호주 총리를 국빈 방문했습니다. 양국 정상은 코로나19 문제와 양국 관계, 인도·태평양 안보 문제 등에 대해 양국 협력을 확인하는 공동성명을 발표했습니다. 아던과 모리슨은 또한 남중국해 분쟁과 홍콩과 신장의 인권에 대한 우려를 제기했습니다.[220][221] 공동성명에 대해 왕원빈 중국 외교부 대변인은 호주와 뉴질랜드 정부가 중국의 내정을 간섭하고 있다고 비판했습니다.[222]

2021년 12월 초, 아던은 조 바이든 미국 대통령이 주최한 가상 민주주의 정상회의에 참석했습니다. 연설에서 그녀는 COVID-19 시대에 민주적 회복력을 강화하는 것에 대해 이야기했으며 패널 토론이 뒤따랐습니다. 아던 총리는 또 뉴질랜드가 태평양 국가들의 반부패 노력을 지원하는 데 100만 뉴질랜드 달러를 추가로 출연할 뿐 아니라 유네스코의 글로벌 미디어 방위 기금과 국제 공익 미디어 기금에도 기여할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[223]

2022년 4월, 아던은 뉴질랜드 의회가 우크라이나 침공에 대한 대응으로 만장일치로 러시아에 대한 제재를 가함에 따라 129명의 다른 의회 의원 및 고위 정부 관리와 함께 러시아 입국이 금지되었습니다.[224]

2022년 5월 말, 아던은 무역 및 관광 사절단을 이끌고 미국으로 갔습니다. 그녀는 여행 중에 바이든 행정부에게 2017년 이전 트럼프 행정부가 포기한 환태평양경제동반자협정의 후속인 포괄적·점진적 환태평양경제동반자협정(CPTPP)에 가입할 것을 촉구했습니다.[225][226] 아던은 스티븐 콜버트와 함께 레이트 쇼에 참석하면서 2019년 크라이스트처치 모스크 총격 사건 이후 뉴질랜드의 반자동 총기 금지를 이유로 롭 초등학교 총기 난사 사건을 규탄하고 더 강력한 총기 규제 조치를 주장하기도 했습니다.[227][228] 5월 27일, 아던은 하버드 대학교에서 총기 개혁과 민주주의에 대해 말하면서 연례 졸업식 연설을 했습니다. 그녀는 명예 법학박사 학위도 받았습니다.[229] 5월 28일, 아던은 개빈 뉴섬 캘리포니아 주지사와 기후 변화 완화 및 연구에 대한 뉴질랜드와 캘리포니아 간의 양자 협력을 공식화하는 양해각서에 서명했습니다.[230]

2022년 6월 1일, 아던은 조 바이든 미국 대통령과 카멀라 해리스 부통령을 만나 양국 관계를 재확인했습니다. 두 정상은 또 남중국해 분쟁, 러시아 침공 대응 우크라이나 지원, 대만과의 중국 긴장, 신장과 홍콩의 인권 침해 의혹 등 다양한 문제에 대한 양국 간 협력을 재확인하는 공동성명을 발표했습니다.[231][232] 이에 대해 자오리젠 중국 외교부 관리는 뉴질랜드와 미국이 중국이 태평양 도서 국가들과 관계를 맺고 있다는 허위 정보를 퍼뜨리려 한다고 비난하며 뉴질랜드가 명시한 '독자적 외교 정책'을 고수할 것을 촉구했습니다.[233][234]

2022년 6월 10일, 아던 총리는 새로 선출된 앤서니 알바니즈 호주 총리를 방문했습니다. 두 정상은 호주의 말썽 많은 501조 추방 정책, 태평양 지역에서의 중국의 영향, 기후 변화, 그리고 태평양 이웃 국가들과의 협력을 포함한 다양한 문제들에 대해 논의했습니다. 아던의 우려에 대해 알바니즈는 호주에 거주하는 뉴질랜드인들에게 미치는 추방 정책의 부정적인 영향에 대한 뉴질랜드의 우려를 해결할 방법을 모색할 것이라고 말했습니다.[235][236]

2022년 6월 말, 아던은 뉴질랜드가 나토 행사에서 공식적으로 연설한 첫 번째 나토 정상회의에 참석했습니다. 연설 중에 그녀는 평화와 인권에 대한 뉴질랜드의 헌신을 강조했습니다. 아던 총리는 또 중국이 남태평양의 국제규범과 규칙에 도전하고 있다고 비판했습니다. 그녀는 또한 러시아가 우크라이나에 대한 지원 때문에 뉴질랜드를 겨냥한 허위 정보 캠페인을 벌이고 있다고 주장했습니다.[237][238] 이에 대해 중국 대사관은 중국이 남태평양 지역과의 관계를 옹호하면서, 중국은 지역 개발 촉진에만 관심이 있을 뿐, 지역의 군사화를 추구하지 않았다고 주장했습니다.[239]

2022년 6월 30일, 아던은 볼로디미르 젤렌스키 우크라이나 대통령과 전화 통화를 했습니다. 젤렌스키는 앞서 유럽 무역 사절단 기간 동안 아던에게 우크라이나 방문을 요청했지만, 아던은 일정 문제로 인해 거절했습니다. 대화 도중 아던 총리는 젤렌스키 대통령에게 뉴질랜드가 러시아에 대한 제재를 계속할 것이라고 안심시켰습니다. 젤렌스키는 또한 뉴질랜드가 우크라이나에 원조를 제공한 것에 감사하고 우크라이나 재건을 위한 지원을 요청했습니다.[240]

2022년 8월 초, 아던은 뉴질랜드의 정치 지도자, 공무원, 시민 사회 지도자, 그리고 국민당과 야당 지도자 크리스토퍼 룩슨, 아츠를 포함한 언론인들로 구성된 대표단을 이끌었습니다. 카멜 세풀로니 문화유산부 장관과 윌리엄 시오 태평양 인민부 장관이 사모아 독립 60주년을 맞아 사모아를 국빈 방문했습니다. 이번 방문은 2022년 6월 사모아 총리 피아메 나오미 마타파의 뉴질랜드 방문에 앞서 이뤄졌습니다.[241][242] 8월 2일, 아던은 피아메와 만나 뉴질랜드의 기후 변화, 경제 회복력, COVID-19, 보건 및 사모아 계절 근로자를 포함한 양국 관계에 대한 우려 사항을 논의했습니다. 아던 총리는 또 뉴질랜드가 사모아의 기후변화 완화 노력을 지원하기 위해 1천500만 뉴질랜드달러, 아피아의 역사적인 사발랄로 시장을 재건하기 위해 1천200만 뉴질랜드달러의 지원을 약속할 것이라고 확인했습니다.[243]

2022년 9월, 아던은 약혼자 클라크 게이포드(Clarke Gayford)와 딸 네브(Neve)와 함께 엘리자베스 2세 여왕의 장례식에 참석했습니다. 장례식 동안, 그녀는 마오리 패션 디자이너 Kiri Nathan이 디자인한 전통적인 마오리 망토를 입었습니다.[244]

2022년 10월 말, 아던과 게이포드는 이 연구 기지의 65주년을 기념하기 위해 뉴질랜드의 남극 기지 스콧 기지를 방문했습니다. 정부는 이미 스콧 기지의 재개발에 3억 4천 4백만 뉴질랜드 달러를 투자했습니다. 뉴질랜드 공군의 아던의 C-130 허큘리스 항공기가 고장 난 후, 그녀와 그녀의 수행원들은 이탈리아의 C-130 허큘리스 항공기를 타고 크라이스트처치로 돌아갔습니다.[245][246]

2022년 11월 중순, 아던 총리는 캄보디아에서 열린 동아시아 정상회의에 참석하여 미얀마 군사정권의 정치범 처형을 규탄하고 러시아의 우크라이나 침공에 대응한 합의를 촉구했습니다.[247] 동아시아 정상회의 기간에 그녀는 바이든 미국 대통령과 만나 미국의 분유 부족 문제를 해결하는 데 도움이 되는 분유 공급을 위한 뉴질랜드 우유 회사 A2 밀크의 노력에 대해 논의했습니다.[248]

11월 30일, 아던 총리는 핀란드 정부 수반이 뉴질랜드를 처음 방문한 산나 마린 핀란드 총리를 모셨습니다. 그녀의 방문 동안, 두 정상은 양국간 무역 관계, 세계 경제 상황, 러시아의 우크라이나 침공, 그리고 이란의 인권에 대해 논의했습니다.[249][250] 이어진 기자회견에서 아던은 두 정부 수반이 비슷한 나이와 성별이기 때문에 만났다는 한 언론인의 제안을 거절했습니다.[251]

사직

2023년 1월 19일, 노동당의 여름 코커스 수련회에서 아던은 2월 7일까지 노동당 대표와 총리직을 사임하고 2023년 총선까지 의회를 떠날 것이라고 발표했습니다. 그녀는 파트너와 딸과 더 많은 시간을 보내고 싶은 욕구와 앞으로 4년을 더 보낼 수 없다는 것을 언급했습니다.[19][20][21] 아던 총리는 2022년 11월에 세 번째 임기를 추구할 것이라고 밝혔습니다.[252] 그녀가 사임 계획을 발표하면서 코커스 수련회에서 언론에 말한 아던은 "저는 이 직업이 무엇을 필요로 하는지 알고 있고 더 이상 정당하게 할 수 있는 충분한 양이 없다는 것을 알고 있습니다. 그렇게 간단합니다. 우리는 그 도전을 위해 새로운 어깨가 필요합니다."[253][254]

아던의 발표는 뉴질랜드 정치권 전반에서 반응을 불러일으켰습니다. 야당인 국민당과 ACT당의 지도자 크리스토퍼 룩슨과 데이비드 시모어는 아던 정부의 정책에 반대를 표하면서 그녀의 봉사에 감사를 표했습니다. 녹색당의 공동 지도자인 제임스 쇼는 아던이 그들의 정당들 사이에 건설적인 업무 관계를 조성했다고 공을 돌렸고, 동료 공동 지도자인 마라마 데이비슨은 아던이 "더 공정하고 안전한" 아오테아로아를 촉진하기 위한 그녀의 연민과 결단력에 대해 칭찬했습니다. 마오리당의 공동 지도자인 데비 은가레와 패커와 라위리 와이티티는 그녀의 리더십 자질과 뉴질랜드 사회에 대한 공헌을 높이 평가했습니다.[255][256] 뉴질랜드의 초대 지도자이자 전 부총리 윈스턴 피터스는 아던의 사임을 그녀의 정부가 2020-2023년 의회 임기 동안 약속과 목표를 이행하지 않았기 때문이라고 말했습니다.[256]

배우 샘 닐, 코미디언이자 작가인 미셸 아코트, 그리고 인터넷 사업가 킴 닷컴을 포함한 저명한 뉴질랜드인들은 아던의 서비스에 감사를 표했습니다. 해외에서는 앤서니 알바니즈 호주 총리와 몇몇 주 지도자들이 아던을 추모했습니다.[257][258]

여러 여론조사에서 아던의 국내 인기는 2023년 1월 19일 기준으로 사상 최저치를 기록했지만, 그녀는 이것이 노동당의 다음 선거 승리 가능성에 영향을 미칠 것이라고 부인했습니다.[254]

총리로서의 아던의 마지막 행사는 마오리족 예언자인 타후포티키 위레무 라타나의 생일 축하였습니다. 그 행사에서, 아던은 수상으로서의 그녀의 일을 "최고의 특권"이라고 불렀고, 그녀는 나라와 국민을 사랑한다고 말했습니다.[259] 2023년 1월 25일, 그녀는 노동당 지도부 선거에서 반대 없이 당선된 크리스 힙킨스에 의해 뉴질랜드 노동당의 총리와 지도자로 승계되었습니다.[260][261]

총리 이후의 경력

2023년 4월 4일 아던은 어스샷 상의 수탁자로 발표되었습니다.[262][263] 아던은 윌리엄 왕자에 의해 그 자리에 선발되었고, 그는 아던이 지속 가능하고 환경적인 해결책을 지원하기 위해 평생 동안 헌신했다고 말했습니다. 왕자에 따르면, 아던은 그가 상을 제정하도록 격려한 최초의 사람들 중 한 명이었습니다.[264]

힙킨스 총리는 같은 날 아던 총리를 크라이스트처치 이슬람 사원 총격 사건 이후 온라인 극단주의 콘텐츠에 대응하기 위해 설립한 크라이스트처치 콜 특사로 임명했습니다.[265] 그녀의 승리 연설 동안, 아던 총리는 뉴질랜드의 정치 지도자들과 정당들에게 기후 변화 대응 (Zero Carbon) 수정법 통과를 위한 정당간의 지지를 얻는 그녀의 역할을 강조하면서, 기후 변화로부터 정치를 제거할 것을 요구했습니다.[266]

아던은 2023년 가을부터 한 학기 동안 하버드 케네디 스쿨에서 이중 펠로우십을 수락하여 2023년 안젤로풀로스 글로벌 공공 리더 펠로우와 리더십과 거버넌스 기술을 공유하고 학습하려는 공공 리더십 센터의 하우저 리더로 활동했습니다. 그녀는 또한 그 기간 동안 하버드의 Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society와 함께 최초의 Knight Tech 거버넌스 리더십 펠로우로서 온라인 극단주의 연구에 집중할 것입니다.[267][268]

정치적 견해

아던은 자신을 사회 민주주의자, 진보주의자, 공화주의자, 페미니스트로 묘사했으며, 페미니스트 클라크를 정치적 영웅으로 인용했습니다. 그녀는 뉴질랜드의 아동 빈곤과 노숙자의 정도를 자본주의의 "돌연변이 실패"라고 묘사했습니다.[272][273] 아던은 2021년 예산에 대해 논평해 달라는 기자들의 질문에 "나를 항상 민주사회주의자로 묘사해왔다"고 말했지만, 이 용어는 정치 분야에서 일반적으로 사용되지 않기 때문에 뉴질랜드에서 유용하다고 생각하지 않습니다.[274] 좌파 잡지 자코뱅은 그녀의 정부가 사회주의자임에도 불구하고 사실상 신자유주의적이었다고 주장합니다.[275] 그녀는 뉴질랜드의 독특한 비핵화 정책을 언급하면서 기후 변화에 대한 조치를 취하는 것을 "우리 세대의 핵 없는 순간"이라고 설명했습니다.[276]

아던은 동성 결혼을 지지하는 발언을 했고,[277] 그녀는 결혼(결혼의 정의)에 투표했습니다. 그것을 합법화한 2013년 개정법.[278] 2018년, 그녀는 뉴질랜드 최초로 프라이드 퍼레이드를 한 총리가 되었습니다.[279] 아던은 1961년 범죄법에서 낙태를 제거하는 것을 지지했습니다.[280][281] 2020년 3월, 그녀는 낙태를 비범죄화하기 위해 법을 개정하는 낙태 입법법에 투표했습니다.[282][283]

아던은 2020년 뉴질랜드 대마초 국민투표에서 대마초 합법화에 찬성표를 던졌지만, 국민투표가 끝날 때까지 합법화에 대한 자신의 입장을 밝히기를 거부했습니다.[284]

뉴질랜드 정치의 논쟁거리인 마오리 선거인단의 미래와 관련하여 아던은 마오리가 선거인단의 유지 또는 폐지를 결정해야 한다고 생각하며, "(마오리는) 그 자리들이 갈 필요성을 제기하지 않았는데 왜 우리가 질문을 하겠는가?"[285]라고 말했습니다. 그녀는 학교에서 마오리어를 의무적으로 공부하는 것을 지지합니다.[10]

2017년 9월, 아던은 뉴질랜드가 국가 원수로서 뉴질랜드의 군주를 제거하는 것에 대해 논의하기를 원한다고 말했습니다.[269] 2021년 5월 24일 신디 키로 여사의 총독 임명을 발표하는 동안 아던은 뉴질랜드가 그녀의 일생 동안 공화국이 될 것이라고 믿었다고 말했습니다.[286] 하지만 그녀는 수년간 왕실 가족들과 정기적으로 만나며 "저의 특별한 견해는 여왕 폐하와 그녀의 가족들, 그리고 그들이 뉴질랜드를 위해 한 일에 대한 제가 가진 존경심을 바꾸지 않습니다. 저는 여러분이 두 가지 견해를 모두 가질 수 있다고 생각하고, 저는 그렇게 생각합니다."[287] 엘리자베스 2세 여왕의 사망 이후, 아던은 공화주의에 대한 그녀의 지지를 재확인했지만, 뉴질랜드가 공화제가 되는 공식적인 움직임은 "조만간 의제가 될 것"이 아니라고 말했습니다.[288]

아던은 이민률이 20,000-30,000명 정도 감소할 것을 제안합니다. "인프라 문제"라고 부르면서, 그녀는 "인구 증가에 대한 계획이 충분하지 않았고, 우리는 반드시 우리의 기술 부족을 적절하게 목표로 삼지 않았다"고 주장합니다.[289] 그러나 그녀는 난민들의 수용을 늘리고 싶어합니다.[290]

외교 분야에서 아던 총리는 이스라엘과 팔레스타인의 갈등을 해결하기 위한 2개 국가의 해결책을 지지한다고 밝혔습니다.[291] 그녀는 가자 국경에서 시위를 하는 동안 이스라엘이 팔레스타인인들을 살해한 것을 비난했습니다.[292]

2022년 11월 대법원의 획기적인 메이크 잇 16 인코퍼레이티드 대 법무장관 판결에 따라 아던은 투표 연령을 16세로 낮추는 것에 대한 지지의 목소리를 높였습니다. 그녀는 정부가 투표 연령을 16세로 낮추는 법안을 도입할 것이라고 발표했습니다; 그런 법안은 75%의 과반수를 요구합니다.[293]

공공이미지

아던은 종종 비판적으로 "유명한 정치인"으로 묘사되었습니다.[294][295][296] 노동당 대표가 된 후, 아던은 CNN과 같은 국제 언론을 포함한 언론의 많은 부분에서 긍정적인 보도를 받았는데,[297] 논평가들은 "자신다 효과"와 "자신다마니아"를 언급했습니다.[298][299]

Jacindamania는 Soft Power 30 지수를 포함한 일부 보고서에서 뉴질랜드가 세계적인 관심과 미디어 영향력을 갖게 된 요인으로 꼽혔습니다.[300] 2018년 해외 순방에서 아던은 특히 뉴욕 유엔에서 연설을 한 후 국제 언론의 많은 관심을 받았습니다. 그녀는 현대 세계 지도자들과 대조적으로 "트럼프주의에 반대하는 사람"으로 캐스팅되었습니다.[301] 트레이시 왓킨스는 스터프에 기고한 글에서 아던이 "세계 무대에서 돌파구"를 마련했으며, 그녀의 반응은 "정치 강자가 부상하고 있는 세계에서 틀을 깨는 젊은 여성으로서 진보 정치의 횃불 운반자"였다고 말했습니다. 그녀는 도널드 트럼프 미국 대통령과 블라디미르 푸틴 러시아 대통령과 같은 사람들의 근육 외교에 방해물입니다."[302]

아던이 그녀의 정부를 구성한 지 1년 후, 가디언지의 엘리너 에인지 로이는 자신다마니아의 인구가 줄어들고 있고, 약속된 변화가 충분히 보이지 않는다고 보도했습니다.[303] 2019년 12월 스핀오프의 편집자 토비 맨하이어가 10년을 검토했을 때, 그는 "아던은... 공감을 드러냈다"며 크라이스트처치 모스크 총격 사건과 와카리/화이트 아일랜드 화산 폭발 이후 그녀의 리더십을 칭찬했습니다. 가장 끔찍한 상황에서 뉴질랜드 사람들을 하나로 모으고 전세계 사람들에게 영감을 준 강철과 투명성. 화카리에서 발생한 비극적인 분화 이후 이번 주에 다시 한번 자신의 모습을 보여준 것은 성격의 힘이었습니다."[304]

그녀의 임기가 끝날 무렵 아던은 국내적으로 인기가 떨어지고 정치적 스펙트럼에서 비판의 수준이 높아졌지만, 그녀는 이것들이 총리직을 사임하기로 결정한 요인들이라고 부인했습니다.[305]

아너즈

아던은 서섹스 공작부인인 객원 편집자 메건이 2019년 9월호 영국 보그 표지에 출연하기로 선택한 15명의 여성 중 한 명이었습니다.[306] 포브스지(Forbes magazine)는 2021년 그녀를 34위로 선정하며 세계에서 가장 영향력 있는 여성 100인에 꾸준히 이름을 올렸습니다.[307] 그녀는 2019년 타임지 선정 100인 명단에[308] 포함되었고 타임지 선정 2019년 올해의 인물에 최종 후보로 올랐습니다.[309] 이 잡지는 나중에 그녀가 크라이스트처치 모스크 총격 사건을 처리한 것으로 6명의 후보 중 2019년 노벨 평화상을 수상할 수도 있다고 잘못 추측했습니다.[310] 2020년, 그녀는 Prospect에 의해 COVID-19 시대에 두 번째로 위대한 사상가로 선정되었습니다.[311] 2020년 11월 19일, 아던은 하버드 대학교의 2020 글리츠먼 국제 활동가상을 수상했습니다.[312]

2021년, 뉴질랜드의 동물학자 스티븐 A. 트레윅은 아던을 기리기 위해 날지 못하는 이 ē 타 종을 헤미안드루스 저신다라고 이름 지었습니다. 아던의 대변인은 딱정벌레(Mecodema jacinda), 이끼(Ocecellia jacinda-Arderniae),[315] 개미([316]Crematogaster jacindae, 사우디아라비아에서 발견됨)도 그녀의 이름을 따서 지어졌다고 말했습니다[314].

2021년 5월 중순, 포춘지는 아던이 코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안의 리더십과 크라이스트처치 모스크 총격 사건 및 와카리/화이트 아일랜드 폭발 사건을 처리한 것을 언급하며 세계 50대 리더 목록에서 1위를 차지했습니다.[317][318]

2022년 5월 26일, 아던은 하버드 대학교로부터 "세계를 형성하는" 공헌으로 명예 법학박사 학위를 받았습니다.[319]

2023년 국왕 생일 및 대관식에서 아던은 국가에 봉사한 공로로 뉴질랜드 훈장(GNZM)의 대녀 동반자로 임명되었습니다.[320]

사생활

종교관

뉴질랜드 예수 그리스도 후기성도 교회(The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints)의 일원으로 자란 아던은 2005년 25세의 나이로 교회를 떠났습니다. 왜냐하면 그것이 그녀의 개인적인 관점, 특히 동성애 권리를 지지하는 그녀의 관점과 상충되기 때문이라고 말했습니다.[321][322] 2017년 1월, 아던은 불가지론자라고 밝히며 "다시는 조직화된 종교의 일원이 될 수 없다"고 말했습니다.[321] 2019년 총리로서 그녀는 LDS 교회의 회장인 러셀 M을 만났습니다. 넬슨.[323]

가족

아던은 전 황가누이 시장인 해미시 맥두얼의 사촌입니다.[324] 그녀는 타라나키-킹 컨트리 셰인 아던의 전 국회의원의 먼 사촌이기도 합니다.[325] 셰인 아던은 저신다 아던이 총리가 되기 3년 전인 2014년에 의회를 떠났습니다.[326]

아던의 남편은 텔레비전 진행자인 클라크 게이포드입니다.[327][328] 이 부부는 2012년 뉴질랜드의 텔레비전 진행자이자 모델인 상호 친구인 콜린 마투라-제프리에 의해 소개되었을 때 처음 만났지만,[329] 게이포드가 논란이 되고 있는 정부 통신 보안국 법안과 관련하여 아던에게 연락하기 전까지 함께 시간을 보내지 않았습니다.[327] 그녀가 총리가 되었을 때 아던과 게이포드는 함께 살고 있었고, 2019년 5월 3일에 그들은 결혼을 하기로 약속한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[330][331] 결혼식은 2022년 1월로 예정되어 있었지만 SARS-CoV-2 오미크론 변종의 발생으로 인해 연기되었습니다.[332][333] 아던과 게이포드는 결국 2024년 1월 13일 호크스 베이의 해블록 노스 근처 크래기 레인지 와이너리에서 결혼식을 올렸습니다.[334]

2018년 1월 19일, 아던은 6월에 첫 아이를 출산할 예정이라고 발표하여 뉴질랜드 최초의 총리가 되었습니다.[335] 아던은 2018년 6월 21일 오클랜드 시립 병원에 [336]입원하여 같은 날 여아를 [337][338]출산하여 재임 중 출산한 두 번째 정부 수반이 되었습니다([9][338]1990년 베나지르 부토 이후). 딸의 이름은 네브 테 아로하(Neve Te Aroha)입니다.[339] 네브(Neve)는 아일랜드어 이름 니암(Niamh)의 영어식 이름으로, 아로하(Aroha)는 사랑을 뜻하는 마오리(Maori)이고, 테 아로하(Te Aroha)는 카이마이 산맥 서쪽에 있는 시골 마을로, 아던(Ardern)의 옛 고향인 모린스빌(Morrinsville) 근처에 있습니다.[340]

게이포드가 형사 범죄로 경찰 조사를 받고 있다는 소문이 커지자 2018년 아던과 마이크 부시 경찰청장 모두 게이포드가 그런 조사를 받지 않았고 받지 않았다는 사실을 확인하는 이례적인 조치를 취했습니다.[341][342]

참고 항목

- 뉴질랜드의 정부 목록

- 뉴질랜드의 정치

- 아던의 전 애완 고양이 패들스(고양이)

참고문헌

- ^ "Members Sworn". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). New Zealand Parliament. p. 2. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Talking work-related hearing loss with NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern". WorkSafe New Zealand. 28 September 2018. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ "2008 GENERAL ELECTION – OFFICIAL RESULT". 6 December 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Ardern, Jacinda – New Zealand Parliament". New Zealand Parliament. 17 April 2023.

- ^ Davison, Isaac (1 August 2017). "Andrew Little quits: Jacinda Ardern is new Labour leader, Kelvin Davis is deputy". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "2017 General Election – Official Results". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ a b Griffiths, James (19 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern to become New Zealand Prime Minister". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "The world's youngest female leader takes over in New Zealand". The Economist. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017.

- ^ a b Khan, M Ilyas (21 June 2018). "Ardern and Bhutto: Two different pregnancies in power". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

Now that New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has hit world headlines by becoming only the second elected head of government to give birth in office, attention has naturally been drawn to the first such leader – Pakistan's late two-time Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Tim (1 August 2017). "What Jacinda Ardern wants". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Live: Jacinda Ardern answers NZ's questions". Stuff. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Fifield, Anna (18 March 2019). "New Zealand's prime minister receives worldwide praise for her response to the mosque shootings". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Friedman, Uri (19 April 2020). "New Zealand's Prime Minister May Be the Most Effective Leader on the Planet". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ a b "The government valued your life at $4.53m – until Covid came along". Newsroom. 15 October 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (8 August 2020). "Election 2020: Labour launches an extremely centrist campaign". Stuff. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "The 2020 General Election and referendums: results, analysis, and demographics of the 53rd Parliament" (PDF). Parliament.nz. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Election 2020: The big winners and losers in Auckland". Stuff. 17 October 2020. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Schwartz, Matthew (17 October 2020). "New Zealand PM Ardern Wins Re-Election In Best Showing For Labour Party In Decades". NPR. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ a b Malpass, Luke (19 January 2023). "Live: Jacinda Ardern announces she will resign as prime minister by February 7th". Stuff. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b McClure, Tess (19 January 2023). "Jacinda Ardern resigns as prime minister of New Zealand". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand PM to step down next month". BBC News. 19 January 2023. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ McClure, Tess (22 January 2023). "New Zealand: Chris Hipkins taking over from Jacinda Ardern on Wednesday". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Candidate profile: Jacinda Ardern". 3 News. 19 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Cumming, Geoff (24 September 2011). "Battle for Beehive hot seat". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Bertrand, Kelly (30 June 2014). "Jacinda Ardern's country childhood". Now to Love. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Keber, Ruth (12 June 2014). "Labour MP Jacinda Ardern warms to Hairy and friends". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Jacobson, Julie. "Jacinda Ardern on her sister's wedding day surprise". Now To Love. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Walch, Tad (20 May 2019). "President Nelson meets New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, says church will donate to mosques". Deseret News. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Elder Ian S. Ardern: 'Go and do'". Church News. 23 April 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern visits Morrinsville College". The New Zealand Herald. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "Ardern, Jacinda: Maiden Statement". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). New Zealand Parliament. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Tanirau, Katrina (10 August 2017). "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern hits hometown in campaign trail". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b Ainge Roy, Eleanor (7 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern becomes youngest New Zealand Labour leader after Andrew Little quits". Archived from the original on 12 September 2017.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (16 September 2017). "How Marie Ardern got her niece Jacinda into politics". Stuff. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Waikato BCS grad Jacinda Ardern becomes leader of the NZ Labour Party". University of Waikato. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "2018". waikato.ac.nz. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "'Jacindamania' sweeps New Zealand as it embraces a new prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, who isn't your average pol". Los Angeles Times. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Ardern pays tribute to lives lost 20 years on from 9/11". Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ Tweed, David; Withers, Tracy (21 October 2017). "Kiwi PM Jacinda Ardern will be world's youngest female leader". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018.

- ^ Duff, Michelle. Jacinda Ardern: The Story Behind An Extraordinary Leader. Allen & Unwin. p. 70.

- ^ a b Dudding, Adam (17 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern: I didn't want to work for Tony Blair". Stuff. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017.

- ^ "People – New Zealand Labour Party". Archived from the original on 23 December 2008.

- ^ "New Voices: Jacinda Ardern, Chris Hipkins and Jonathan Young". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Kirk, Stacey (1 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern says she can handle it and her path to the top would suggest she's right". The Dominion Post. Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern to lead IUSY". The Standard. 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Labour Party list for 2008 election announced Scoop News". Scoop. 31 August 2008. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "Official Count Results – Waikato". electionresults.govt.nz. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (29 January 2010). "Greens' newest MP trains his sights on the bogan vote". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Jacinda Ardern". New Zealand Parliament. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Huffadine, Leith; Watkins, Tracy. "'Bridges and Ardern': the young guns who are now in charge". Stuff. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Auckland Central electorate results 2011". Electionresults.org.nz. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Miller, Raymond (2015). Democracy in New Zealand. Auckland University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-77558-808-5. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "Official Count Results – Auckland Central". Electoral Commission. 4 October 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Small, Vernon (24 November 2014). "Little unveils new Labour caucus". Stuff. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018.

- ^ "The Forum of Young Global Leaders". The Forum of Young Global Leaders. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Community". The Forum of Young Global Leaders. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Sachdeva, Sam (19 December 2016). "Labour MP Jacinda Ardern to run for selection in Mt Albert by-election". Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (15 September 2017). "'I've got what it takes': will Jacinda Ardern be New Zealand's next prime minister?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern Labour's sole nominee for Mt Albert by-election". Stuff. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Jones, Nicholas (12 January 2017). "Jacinda Ardern to contest Mt Albert byelection". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern wins landslide victory Mt Albert by-election". The New Zealand Herald. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ "Mt Albert – Preliminary Count". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern confirmed as Labour's new deputy leader". The New Zealand Herald. 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ "Labour's Raymond Huo set to return to Parliament after Maryan Street steps aside". The New Zealand Herald. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Andrew Little's full statement on resignation". The New Zealand Herald. 31 July 2017. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern is Labour's new leader, Kelvin Davis as deputy leader". 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b Kwai, Isabella (4 September 2017). "New Zealand's Election Had Been Predictable. Then 'Jacindamania' Hit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (31 July 2017). "Jacinda Ardern becomes youngest New Zealand Labour leader after Andrew Little quits". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Little asked Ardern to lead six days before he resigned". The New Zealand Herald. 14 September 2017. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ "Donations to Labour surge as Jacinda Ardern named new leader". The New Zealand Herald. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Video: Jacinda Ardern won't rule out capital gains tax". Radio New Zealand. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Tarrant, Alex (15 August 2017). "Labour leader maintains 'right and ability' to introduce capital gains tax if working group suggests it next term; Would exempt family home". Interest.co.nz. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Kirk, Stacey (1 September 2017). "Jacinda Ardern tells Kelvin Davis off over capital gains tax comments". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Hickey, Bernard (24 September 2017). "Jacinda stumbled into a $520bn minefield". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (14 September 2017). "Election: Labour backs down on tax, will not introduce anything from working group until after 2020 election". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Steven Joyce still backing Labour's alleged $11.7b fiscal hole". Newshub. 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Farmers protest against Jacinda Ardern's tax policies". The New Zealand Herald. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern unshaken by Morrinsville farming protest". Newshub. 19 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Vowles, Jack (3 July 2018). "Surprise, surprise: the New Zealand general election of 2017". Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 13 (2): 147–160. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2018.1443472.

- ^ "Mt Albert – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Preliminary results for the 2017 General Election". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "'Jacindamania' fails to run wild in New Zealand poll". The Irish Times. Reuters. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "2017 General Election – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Ardern and Davis to lead Labour negotiating team". Radio New Zealand. 26 September 2017. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "NZ First talks with National, Labour begin". Stuff. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Haynes, Jessica. "Jacinda Ardern: Who is New Zealand's next prime minister?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Chapman, Grant. "New PM Jacinda Ardern joins an elite few among world, NZ leaders". Newshub. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Green Party ratifies confidence and supply deal with Labour". The New Zealand Herald. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern reveals ministers of new government". The New Zealand Herald. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "New government ministers revealed". Radio New Zealand. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Small, Vernon (20 October 2017). "Predictable lineup of ministers as Ardern ministry starts to take shape". Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "Ministerial List". Ministerial List. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ Cheng, Derek (26 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern sworn in as new Prime Minister". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Steafel, Eleanor (26 October 2017). "Who is New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern – the world's youngest female leader?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Premiers and Prime Ministers". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "It's Labour! Jacinda Ardern will be next PM after Winston Peters and NZ First swing left". The New Zealand Herald. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Members – President Of The Council Of Women World Leaders". lrp.lt. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Atkinson, Neill. "Jacinda Ardern Biography". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern on baby news: 'I'll be Prime Minister and a mum'". Radio New Zealand. 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Patterson, Jane (21 June 2018). "Winston Peters is in charge: His duties explained". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Winston Peters is now officially Acting Prime Minister". The New Zealand Herald. 21 June 2018. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "'Throw fatty out': Winston Peters fires insults on last day as PM". The New Zealand Herald. 1 August 2018. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Mercer, Phil (16 October 2018). "A country famed for quality of life faces up to child poverty". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (2 July 2018). "Jacinda Ardern welcomes new welfare reforms from the sofa with new baby". The Guardian. Dunedin. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Supporting New Zealand families". Beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Biddle, Donna-Lee (28 November 2019). "Free lunches for low-decile school kids: What's on the menu?". Stuff. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Andelane, Lana (19 April 2020). "$25 benefit increase 'making a difference' for beneficiaries during lockdown – Carmel Sepuloni". Newshub. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Klar, Rebecca (6 June 2020). "New Zealand providing free sanitary products in schools". The Hill. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Heyward, Emily (4 March 2018). "Blenheim to get 13 new state houses in nationwide pledge". Stuff. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Neilson, Michael (25 January 2022). "Benefit increases go to 330,000 families – more than half in New Zealand". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Molyneux, Vita (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Business expert condemns Government decision to raise minimum wage amid pandemic". Newshub. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Jones, Shane (23 February 2018). "Provincial Growth Fund open for business". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Jones, Nicholas (20 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern confirms new government will dump tax cuts". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Collins, Simon (26 June 2019). "Teachers accept pay deal – but principals reject it". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Peter (18 April 2019). "Week in Politics: Labour's biggest campaign burden scrapped". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Williams, Larry. "Jack Tame: No CGT is 'enormous failure' for PM". Newstalk ZB. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "Ordinary New Zealanders bearing brunt of bright-line test". RNZ News. 29 January 2022. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b Ainge-Roy, Eleanor (6 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern defuses tensions on New Zealand's sacred Waitangi Day". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Sachdeva, Sam (6 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern ends five-day stay in Waitangi". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ O'Brien, Tova; Hurley, Emma (9 July 2018). "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern accepts Clare Curran's resignation as a minister". Newshub. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Clare Curran situation has 'done real damage' to Jacinda Ardern and Government's credibility – Simon Bridges". TVNZ. 7 September 2018. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Manhire, Toby (11 September 2019). "Timeline: Everything we know about the Labour staffer inquiry". The Spinoff. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Vance, Andrea. "Labour Party president Nigel Haworth has resigned – but it's not over". Stuff. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

Ardern says she didn't know the allegations were sexual until this week. That's hard to swallow.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (12 September 2019). "Ardern under pressure as staffer accused of sexual assault quits". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "New Zealand sets 2020 cannabis referendum". BBC News. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Cave, Damien (1 October 2020). "Jacinda Ardern Admits Having Used Cannabis. New Zealanders Shrug: 'Us Too.'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Official referendum results released". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Rychert, Marta; Wilkins, Chris (7 March 2021). "Why did New Zealand's referendum to legalise recreational cannabis fail?". Drug and Alcohol Review. 40 (6): 877–881. doi:10.1111/dar.13254. PMID 33677836. S2CID 232140948.

- ^ "Students disappointed Labour Party dropped fees-free plan". RNZ. 16 September 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Walters, Laura; Small, Vernon. "Jacinda Ardern makes first state visit to Australia to strengthen ties". Stuff. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (5 November 2017). "Key bromance haunts Jacinda Ardern's first Australia visit". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern: Australia's deportation policy 'corrosive'". BBC News. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern blasts Scott Morrison over Australia's deportation policy – video". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (28 February 2020). "Extraordinary scene as Jacinda Ardern directly confronts Scott Morrison over deportations". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ O'Meara, Patrick (9 November 2017). "PM heads to talks hoping to win TPP concessions". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ McCulloch, Craig (20 April 2018). "CHOGM: Ardern to toast Commonwealth at leaders' banquet". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Ensor, Jamie; Lynch, Jenna (24 September 2019). "Jacinda Ardern, Donald Trump meeting: US President takes interest in gun buyback". Newshub. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Gambino, Lauren (23 September 2019). "Trump showed interest in New Zealand gun buyback program, Ardern says". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Coughlan, Thomas (30 October 2018). "Ardern softly raises concern over Uighurs". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Christian, Harrison (7 November 2018). "The disappearing people: Uighur Kiwis lose contact with family members in China". Stuff. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Mutch Mckay, Jessica (14 November 2018). "Jacinda Ardern meets with Myanmar's leader, voices concern on Rohingya situation". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Bracewell-Worrall, Anna (5 September 2018). "'I am Prime Minister – I have a job to do': Jacinda Ardern defends separate Nauru flight". Newshub. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (24 September 2018). "Jacinda Ardern makes history with baby Neve at UN general assembly". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Cole, Brendan. "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand Prime Minister Makes History By Becoming First Woman to Bring Baby into U.N.Assembly". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Full speech: 'Me too must become we too' – Jacinda Ardern calls for gender equality, kindness at UN". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ "TPP deal revived once more, 20 provisions suspended". Radio New Zealand. 12 November 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership" (PDF). New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Satherley, Dan (12 November 2017). "TPP 'a damned sight better' now – Ardern". Newshub.co.nz. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Wahlquist, Calla (24 March 2019). "An image of hope: how a Christchurch photographer captured the famous Ardern picture". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ McConnell, Glenn (18 March 2019). "Face of empathy: Jacinda Ardern photo resonates worldwide after attack". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Britton, Bianca (15 March 2019). "New Zealand PM full speech: 'This can only be described as a terrorist attack'". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Three in custody after 49 killed in Christchurch mosque shootings". Stuff. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Greenfield, Charlotte; Westbrook, Tom. "New gun laws to make NZ safer after mosque shootings, says PM Ardern". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ George, Steve; Berlinger, Joshua; Whiteman, Hilary; Kaur, Harmeet; Westcott, Ben; Wagner, Meg (19 March 2019). "New Zealand mosque terror attacks". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "Christchurch shootings: Ardern vows never to say gunman's name". BBC News. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Collman, Ashley (19 March 2019). "People around the world are praising New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern for her compassionate response to the Christchurch mosque shootings". Thisisinsider. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Newson, Rhonwyn (18 March 2019). "Christchurch terror attack: Jacinda Ardern praised for being 'compassionate leader'". Newshub. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ "New Zealand's prime minister receives worldwide praise for her response to the mosque shootings". The Washington Post. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Shad, Saman (20 March 2019). "Five ways Jacinda Ardern has proved her leadership mettle". SBS World News. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ Picheta, Rob. "Image of Jacinda Ardern projected onto world's tallest building". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Prior, Ryan. "A painter has revealed an 80-foot mural of New Zealand's prime minister comforting woman after mosque attacks". CNN. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Walls, Jason (16 March 2019). "Christchurch mosque shootings: New Zealand to ban semi-automatic weapons". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (19 March 2019). "Jacinda Ardern says cabinet agrees New Zealand gun reform 'in principle'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Graham-McLay, Charlotte (10 April 2019). "New Zealand Passes Law Banning Most Semiautomatic Weapons, Weeks After Massacre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Core group of world leaders to attend Jacinda Ardern-led Paris summit". The New Zealand Herald. 29 April 2019. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "Everyone travelling to NZ from overseas to self-isolate". Radio New Zealand. 14 March 2020. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Keogh, Brittany (14 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Prime Minister Ardern updates New Zealand on Covid-19 outbreak". Stuff. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Whyte, Anna (19 March 2020). "PM places border ban on all non-citizens and non-permanent residents entering NZ". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Live: PM Jacinda Ardern to give update on coronavirus alert level". Stuff. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Ensor, Jamie (24 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Jacinda Ardern's 'incredible', 'down to earth' leadership praised after viral video". Newshub. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Khalil, Shaimaa (22 April 2020). "Coronavirus: How New Zealand relied on science and empathy". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Fifield, Anna (7 April 2020). "New Zealand isn't just flattening the curve. It's squashing it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Campbell, Alastair (11 April 2020). "Jacinda Ardern's coronavirus plan is working because, unlike others, she's behaving like a true leader". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Boyle, Chelseas (23 April 2020). "Lockdown lawsuit fails: Legal action against Jacinda Ardern dismissed". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Earley, Melanie (23 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Man's lawsuit over Covid-19 lockdown restrictions dismissed". Stuff. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Trans-Tasman bubble: Jacinda Ardern gives details of Australian Cabinet meeting". Radio New Zealand. 5 May 2020. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Wescott, Ben (5 May 2020). "Australia and New Zealand pledge to introduce travel corridor in rare coronavirus meeting". CNN. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ O'Brien, Tova (18 May 2020). "Newshub-Reid Research Poll: Jacinda Ardern goes stratospheric, Simon Bridges is annihilated". Newshub. MediaWorks TV. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "Pressure mounts as National falls to 29%, Labour skyrockets in 1 NEWS Colmar Brunton poll". 1 News. TVNZ. 21 May 2020. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Pandey, Swati (18 May 2020). "Ardern becomes New Zealand's most popular PM in a century – poll". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ O'Brien, Tova (18 May 2020). "Newshub-Reid Research Poll: Simon Bridges still confident he will lead National into election despite personal poll rating below 5 percent". Newshub. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "New Zealand election: Jacinda Ardern's Labour Party scores landslide win". BBC News. 17 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "2020 General Election and Referendums – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Shaw, Richard; Hayward, Bronwyn; Vowles, Jack; Curtin, Jennifer; MacDonald, Lindsey (17 October 2020). "Jacinda Ardern and Labour returned in a landslide — 5 experts on a historic New Zealand election". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Mt Albert – Official Result". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "New Zealand's Ardern credits virus response for election win". The Independent. 18 October 2020. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Phil (2 December 2020). "New Zealand declares a climate change emergency". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (2 December 2020). "Government will have to buy electric cars and build green buildings as it declares climate change emergency". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (25 September 2021). "Interview: The transformation of Greta Thunberg". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Sam Sachdeva (23 March 2021). "'No silver bullet', but Govt fires plenty at housing crisis". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Jeremy Couchman (25 March 2021). "Higher house price caps would have helped only a few hundred first home buyers". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Neilson, Michael (14 June 2021). "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announces apology for dawn raids targeting Pasifika". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Whyte, Anna (14 June 2021). "Government Minister Aupito William Sio in tears as he recalls family being subjected to dawn raid". 1 News. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Davison, Isaac (9 September 2022). "How NZ will honour Elizabeth, PM praises 'incredible woman'". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "PM mourns death of Queen Elizabeth II". New Zealand Government. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Brockett, Matthew (12 September 2022). "Ardern Expects New Zealand to Eventually Become a Republic". Bloomberg UK. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern caught on hot mic calling minor opposition party leader an 'arrogant prick'". The Guardian. 13 December 2022. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ McConnell, Glenn (14 December 2022). "Jacinda Ardern apologises for calling David Seymour an 'arrogant prick'". Stuff. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Ella (18 December 2022). "Jacinda Ardern and David Seymour's 'arrogant prick' charity auction reaches $60,000". Stuff. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Melinda Gates' plea to Ardern over Covid-19 vaccine". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Goalkeepers 2019 NYC Event Press Release". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Covid 19 coronavirus: Cook Islands, New Zealand travel bubble without quarantine from early next year". The New Zealand Herald. 12 December 2020. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (14 December 2020). "New Zealand travel bubble with Australia coming in early 2021, NZ PM confirms". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Govt secures another two Covid-19 vaccines, PM says every New Zealander will be able to be vaccinated". Radio New Zealand. 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ de Jong, Eleanor (26 January 2021). "New Zealand borders to stay closed until citizens are 'vaccinated and protected'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Covid 19 coronavirus: No new community cases – Ashley Bloomfield and health officials give press conference as first Kiwis receive vaccinations". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "New Zealand enters nationwide lockdown over one Covid case". BBC News. 17 August 2021. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Against all odds: how New Zealand is bending the Delta curve". The Guardian. 10 September 2021. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Covid-19: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern in self-isolation, identified as close contact of Covid case". Stuff. 29 January 2022. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern tests positive for Covid-19". Radio New Zealand. 14 May 2022. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (8 May 2022). "Covid-19 NZ: Jacinda Ardern isolating at home as partner Clarke Gayford infected". Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Perry, Nick (2 December 2020). "New Zealand joins Australia in denouncing China's tweet". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Patterson, Jane (1 December 2020). "New Zealand registers concern with China over official's 'unfactual' tweet". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Ng, Qi Siang (9 December 2020). "For Jacinda Ardern, the digital economy is about people too". The Edge. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Welch, Dylan; Dredge, Suzanne; Dziedzic, Stephen (16 February 2021). "New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern criticises Australia for stripping dual national terror suspect's citizenship". ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Whyte, Anna (16 February 2021). "Jacinda Ardern delivers extraordinary broadside at Australia over woman detained in Turkey – 'Abdicated its responsibilities'". 1 News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Ardern condemns Australia for revoking ISIL suspect's citizenship". Al Jazeera. 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Manch, Thomas (17 February 2021). "Jacinda Ardern, Scott Morrison agree to work in 'spirit of our relationship' over alleged Isis terrorist". Stuff. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "'I despair at what's happening' — Ardern condemns both Israel and Hamas over deadly violence in Gaza". 1 News. 17 May 2021. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ McClure, Tess (30 May 2021). "Jacinda Ardern hosts Scott Morrison in New Zealand for talks with post-Covid 'rulebook' on agenda". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Ardern, Jacinda (31 May 2021). "Joint statement: Prime Ministers Jacinda Ardern and Scott Morrison". Beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (1 June 2021). "China slams 'gross interference' from Jacinda Ardern and Scott Morrison's joint statement on Hong Kong and Xinjiang". Stuff. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Ardern, Jacinda (10 December 2021). "NZ attends US President's Democracy Summit". Beehive.govt.nz. Ministry of Health. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ "Russia bans Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern from entering country". Radio New Zealand. 8 April 2022. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Burns-Francis, Anna (25 May 2022). "Jacinda Ardern busy promoting NZ on US visit". 1 News. TVNZ. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand's Ardern urges US to return to regional trade pact". Al Jazeera. 26 May 2022. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ McClure, Tess (25 May 2022). "New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern responds to Texas school shooting". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Malpass, Luke; Jack, Amberleigh (27 May 2022). "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern responds to Texas school shooting on Late Show with Stephen Colbert". Stuff. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern addresses Harvard on gun control and democracy". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 27 May 2022. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "New Zealand signs partnership with California on climate change". Radio New Zealand. 28 May 2022. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "United States – Aotearoa New Zealand Joint Statement". The White House. 31 May 2022. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Malpass, Luke (1 June 2022). "Joe Biden meeting has strengthened NZ's relationship with US, Jacinda Ardern says". Stuff. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian's Regular Press Conference on June 1, 2022". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 1 June 2022. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Manch, Thomas; Morrison, Tina (2 June 2022). "China heavily criticises New Zealand for 'ulterior motives' after Biden meeting". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Mann, Toby; Burrows, Ian (10 June 2022). "Anthony Albanese says New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's concerns around deportations need to be considered". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Whyte, Anna (10 June 2022). "Ardern, Albanese to take trans-Tasman relationship 'to a new level'". 1 News. TVNZ. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ McClure, Tess (30 June 2022). "West must stand firm as China challenges 'rules and norms', Ardern tells Nato". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ McConnell, Glenn (30 June 2022). "Jacinda Ardern calls for nuclear disarmament, criticises China over human rights during Nato speech". Stuff. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Statement by the Spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in New Zealand on New Zealand's Comments to NATO Session". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in New Zealand. 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Scotcher, Katie (30 June 2022). "Ardern speaks to Zelensky, reiterates support and continued sanctions". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "After 865 days, Samoa reopens to tourists". 1 News. TVNZ. Australian Associated Press. 31 July 2022. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Ardern, Luxon and ministers to visit Samoa for treaty anniversary". Radio New Zealand. 28 July 2022. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Dexter, Giles (2 August 2022). "PM announces $15m to support Samoa with climate change priorities". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Tran, Cindy (20 September 2022). "Hidden meaning behind New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's outfit at Queen's funeral". Seven News. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Witton, Bridie (27 October 2022). "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand's presence in Antarctica at 'critical juncture'". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Gibbens, Krystal (29 October 2022). "Jacinda Ardern's plane breaks down in Antarctica". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Beckford, Gyles (13 November 2022). "Myanmar govt's executions 'a stain on region' – Jacinda Ardern". Radio New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (13 November 2022). "Jacinda Ardern in Cambodia: Catch-up with Joe Biden at East Asia Summit and a trade upgrade". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern and Sanna Marin dismiss claim they met due to 'similar age'". BBC News. 30 November 2022. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ McConnell, Glenn (30 November 2022). "Finnish PM Sanna Marin wants to go 'next level' with New Zealand, as she rallies against autocrats". Stuff. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Witton, Bridie (30 November 2022). "The not-so-subtle sexism that followed Finland's Sanna Marin from Helsinki to Auckland". Stuff. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ McClure, Tess (7 November 2022). "Jacinda Ardern rallies party faithful as Labour faces difficult re-election path". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern to step down as New Zealand's prime minister". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand PM to step down next month". BBC News. 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Political rivals react to Ardern's shock resignation". 1 News. TVNZ. 19 January 2023. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Jacinda Ardern quits: Prime Minister 'driven from politics' due to 'constant personalisation and vilification' – Te Pāti Māori". The New Zealand Herald. 19 January 2022. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern resigns: Politicians and New Zealanders pay tribute". Radio New Zealand. 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern resigns: The world reacts". Newshub.

- ^ "Leading New Zealand was 'greatest privilege', says Jacinda Ardern at final event". The Guardian. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Chris Hipkins sworn in as prime minister". Radio New Zealand. 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Whyte, Luke Malpass and Anna (20 January 2023). "Chris Hipkins set to become New Zealand's next prime minister". Stuff. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ tom_tep (4 April 2023). "Jacinda Ardern joins The Earthshot Prize as a Trustee". The Earthshot Prize. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Wood, Patrick (6 April 2023). "New Zealand's Jacinda Ardern takes on a new role after leaving politics this week". NPR. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Adams, Charley (4 April 2023). "Jacinda Ardern appointed trustee of Prince William's Earthshot Prize". BBC News. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ "Former PM Jacinda Ardern appointed as Christchurch Call Envoy". Radio New Zealand. 4 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.