국제적 관심사인 공중보건 비상사태

Public health emergency of international concernPHEIC(Public Health Emergency of International concerness, 국제 보건 비상사태)는 세계보건기구(WHO)가 "질병의 국제적 확산을 통해 다른 국가에 대한 공중 보건 위험을 구성하고 잠재적으로 조정된 국제적 대응을 필요로 하는 특별한 사건"에 대해 공식적으로 선언한 것으로, 다음과 같이 규정된다.이는 "영향받은 주의 국경을 넘어 공중 보건에 대한 영향을 줄 수 있다"며 "즉각적인 국제 [1]조치가 필요할 수 있다"는 것이다.2005년 국제보건규정(IHR)에 따르면 주정부는 [2]PHIC에 신속하게 대응할 법적 의무가 있습니다.이 선언은 2002-2004년 사스 [4]사태 이후 개발된 국제보건기구 [3]비상대책위원회(EC)에 의해 발표됐다.

2009년과 2022년 사이에, 7개의 PHEIC 선언이 있었다: 2009년 H1N1(또는 돼지 독감) 대유행, 2014년 소아마비 선언, 2013-2016년 서아프리카 에볼라 발생, 2015-16년 지카 바이러스 유행,[5] 2018-20년 키부 에볼라 유행,[6] 진행 중인 COVID-19 [7]대유행, 2022년 원숭이 발생.[8]권고사항은 임시적이며 [1]3개월마다 검토가 필요합니다.

자동적으로 사스, 천연두, 야생형 소아마비, 그리고 모든 새로운 인간 인플루엔자 아형은 PHEICs로 간주되기 때문에 [9]IHR의 결정을 필요로 하지 않는다.PHEIC는 감염성 질환에만 국한된 것이 아니라 화학약품이나 [10][11]방사성 물질에 노출되어 발생하는 비상사태를 커버할 수 있다.이는 "경보 시스템", "실천 요청" 및 "최후의 수단"[12][13]으로 볼 수 있습니다.

배경

질병의 확산을 억제하기 위한 조기 발견과 효과적인 대응을 위해 전 세계에 여러 감시 및 대응 시스템이 존재한다.시간 지연은 크게 두 가지 이유로 발생합니다.첫 번째는 첫 번째 사례와 의료 시스템에 의한 발병 확인 사이의 지연으로, 데이터 수집, 평가 및 구성을 통한 양호한 감시에 의해 완화된다.두 번째는 발병이 감지되고 국제적 [4]관심사로 널리 인식되고 선언될 때까지의 지연이다.이 선언은 2002-2003년 [4]사스 발생 이후 개발된 IHR(2005)[3]에 따라 운영되는 국제 전문가들로 구성된 비상대책위원회(EC)에 의해 발표된다.2009년과 2016년 사이에, 4개의 PHEIC [14]선언이 있었다.다섯 번째는 2019년 [6]7월 17일 발표된 2018-20년 키부 에볼라 유행이다.여섯 번째는 2019-20년 COVID-19 [15]대유행이었다.7번째는 2022년 원숭이 수두 [8]발생이다.2005년 국제보건규정(IHR)에 따라 주 당국은 [2]PHIC에 신속하게 대응할 법적 의무가 있습니다.

정의.

PHEIC는 다음과 같이 정의됩니다.

질병의 국제적 확산을 통해 다른 국가에 대한 공중 보건 위험을 구성하고 잠재적으로 국제 [16]협력이 필요한 특별한 사건.

이 정의는 잠재적으로 전지구적 범위에 있는 공중 보건 위기를 의미하며, [16][17]즉각적인 국제적 조치가 필요할 수 있는 "심각한, 갑작스러운, 비정상적이거나 예상치 못한" 상황을 암시한다.

이는 "경보 시스템", "실행 촉구" [12][13]및 "최후의 수단"으로 볼 수 있습니다.

잠재적인 문제 보고

WHO 회원국은 24시간 이내에 잠재적 PHEIC 사건을 [9]WHO에 보고할 수 있다.잠재적 발병 가능성을 보고하는 회원국이 될 필요는 없기 때문에 WHO에 대한 보고는 [18][19]비정부 소식통에 의해 비공식적으로 접수될 수도 있다.IHR(2005)에서는 PHEIC를 피하기 위해 모든 국가에서 이벤트를 검출, 평가, 통지 및 보고하는 방법이 확인되었다.공중 보건 위험에 대한 대응 또한 [12]결정되었다.

IHR 결정 알고리즘은 WHO 회원국이 잠재적 PHEIC가 존재하는지 여부와 WHO에 통지해야 하는지 여부를 결정하는 데 도움이 됩니다.다음 4개의 질문 중 [9]2개가 확인되면 WHO에 통보해야 합니다.

- 그 행사의 공중 보건에 미치는 영향은 심각한가요?

- 이 사건은 이례적인 것입니까, 아니면 예상치 못한 것입니까?

- 국제적 확산에 상당한 위험이 있습니까?

- 국제 여행 또는 무역 제한에 대한 상당한 위험이 있습니까?

PHEIC 기준에는 항상 [18]통지할 수 있는 질환 목록이 포함됩니다.사스, 천연두, 야생형 소아마비, 그리고 어떤 새로운 인간 인플루엔자 아형은 항상 PHEIC이며,[16] 그것들을 그렇게 선언하기 위해 IHR의 결정이 필요하지 않습니다.

대중의 관심을 끄는 대규모 건강 비상사태가 PHEIC가 [12]되기 위한 기준을 반드시 충족시키는 것은 아니다.예를 들어,[11][20] EC는 아이티에서의 콜레라 발생, 시리아에서의 화학 무기 사용, 일본에서의 후쿠시마 핵 참사를 위해 소집되지 않았다.

콜레라, 폐렴 페스트, 황열,[20] 바이러스성 출혈열을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않는 전염병이 되기 쉬운 질병에 대해서는 추가 평가가 필요하다.

PHEIC의 선언은 전염병에 직면한 국가에게 경제적 부담으로 보일 수 있다.전염병을 선언할 동기가 부족하고 PHEIC는 이미 [12]어려움을 겪고 있는 국가들의 무역에 제한을 두는 것으로 보일 수 있다.

비상 위원회

PHEIC를 선언하기 위해 WHO 사무총장은 인간의 건강과 국제적 확산에 대한 위험과 국제 전문가 위원회(ICR Emergency Committee, EC)의 조언을 포함하는 요소를 고려해야 한다. 이 중 한 명은 사건이 [1]발생한 지역 내에서 국가가 지명하는 전문가여야 한다.EC는 상임위원회가 아니라 임시변통으로 [21]만들어졌다.

2011년까지 IHR EC 회원국의 이름은 공개되지 않았지만 개혁의 여파로 공개되고 있다.이들 회원은 문제의 질병과 행사의 성격에 따라 선발된다.IHR 전문가 명단에서 이름을 따다.사무총장은 사건에 대한 모든 이용 가능한 데이터를 검토한 후 법적 기준과 미리 결정된 알고리즘을 사용하여 위기에 대한 기술적 평가에 따라 EC의 조언을 받는다.선언 후 EC는 위기에 [21]대처하기 위해 사무총장 및 회원국이 취해야 할 조치에 대해 권고한다.이 권장사항은 임시로 시행 [1]중인 3개월마다 검토해야 합니다.

선언

PHEIC 선언 요약

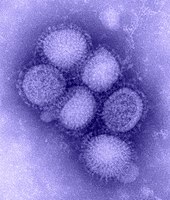

신종플루 (2009)

2009년 봄, 신종 인플루엔자 A(H1N1) 바이러스가 출현했다.그것은 북미의 멕시코에서 처음 발견되었다.그것은 미국과 [22]전 세계로 빠르게 퍼져나갔다.2009년 [23]4월 26일, 첫 [4]발병 후 한 달 이상이 지난 후, H1N1(또는 돼지 독감) 대유행이 아직 [24][25][26]3단계에 있을 때 초기 PHEIC가 선언되었다.같은 날 3시간 만에 WHO 웹사이트는 거의 200만 건의 접속을 받았고, 돼지 인플루엔자 [23]대유행 전용 웹사이트가 필요했다.H1N1이 PHEIC로 선언되었을 때, 그것은 오직 3개국에서만 [4]발생했다.따라서, H1N1의 PHEIC 발생 선언이 대중의 [20]공포를 부추기고 있다는 주장이 제기되었다.WHO가 후원한 2013년 연구는 계절 인플루엔자와 규모가 비슷하지만 65세 미만 [27]인구에서 사망률로 전환하기 때문에 계절 인플루엔자보다 수명이 더 오래 걸린다고 추정했다.

소아마비 (2014)

두 번째 PHEIC는 2014년 5월 5일 발표된 소아마비 선언으로 야생 소아마비와 순환성 백신 유래 폴리오 바이러스의 [10]사례가 증가했다.글로벌 박멸로서 달성된 지위는 아프가니스탄, 파키스탄,[20][10] 나이지리아에서 소수의 사례와 함께 육로 항공 여행과 국경 통과에 의해 위험하다고 간주되었다.

2019년 10월, 아프리카와 아시아의 새로운 백신 유래 사례와 더불어 파키스탄과 아프가니스탄의 지속적인 야생 소아마비 사례가 검토되었고, 소아마비는 계속해서 [28]PHEIC가 되었다.2021년 11월 현재, 아프가니스탄의 최근 사건, 많은 수의 예방접종되지 않은 어린이, 파키스탄의 이동성 인구 증가 및 COVID-19 대유행과 관련된 위험을 고려하면, 소아마비는 여전히 PHEIC로 [29]남아 있다.

에볼라 (2014년)

2014년 3월 기니와 라이베리아, 2014년 5월까지 시에라리온에서 에볼라 확진 환자가 보고되고 있다.2014년 8월 8일 금요일, 미국과 유럽에서 에볼라 바이러스가 발생한 후, 그리고 이미 다른 3개국에서 [12]수개월 동안 심각한 전염병이 진행 중인 가운데, WHO는 서아프리카에서의 [30]에볼라 발병에 대한 대응으로 세 번째 PHEIC를 선언했다.나중에, 한 리뷰는 미국에 대한 이 전염병의 직접적인 영향이 PHEIC [4]선언을 증가시켰다는 것을 보여주었다.자원 부족 [12]환경에서의 최초의 PHEIC입니다.

지카 바이러스 (2016년)

2016년 2월 1일, WHO는 당시 진행 중인 2015-16년 지카 바이러스 [31]유행과 관련이 있는 것으로 의심되었던 미주 지역의 소두증과 길랭-바레 증후군에 대한 대응으로 네 번째 PHEIC를 선언했다.이후 연구와 증거는 이러한 우려를 뒷받침했다; 4월에, WHO는 "지카 바이러스가 소두증과 길랭-바레 [32]증후군의 원인이라는 과학적 합의가 있다"고 말했다.PHEIC가 모기 매개 [20]질환으로 선언된 것은 이번이 처음이다.이 선언은 2016년 [33]11월 18일에 해제되었다.

키부 에볼라 (2018~20)

WHO는 2018년 10월과 2019년 4월에 2018-20년 키부 에볼라 유행병을 [34][35]PHEIC로 간주하지 않았다.반면 세계 보건 기구 패널들의 결정이 그것을 선언한 PH을 만장 일치였다 그 결정, 마이클 Osterholm 센터의 전염병 질병 연구 및 정책 연구원 감독과 함께(CIDRAP)실망과"는 에볼라 가스 콩고에서 단지 시합에 맞기를 기다리고 있어요 앉아 있을 수 있"[36] 상황을 설명하는 대응 논란의 여지가 있었죠완제품 부호추가 혜택을 [36]주지 않을 것입니다.2018년 10월과 2019년 4월에 PHEIC를 선언하는 것에 대한 조언은 두 경우 모두 충족된 것으로 보이지만 IHR EC의 투명성에 의문이 제기되었다.키부 에볼라 유행에 대한 진술에서 사용된 언어는 다른 것으로 알려져 있다.2018년 10월 EC는 "현 시점에서 PHEIC를 선언해서는 안 된다"고 밝혔다.PHEIC를 선언하기 위해 이전에 거부된 13개의 제안에서 결과 문구는 "PHEIC에 대한 조건이 현재 충족되지 않음" 및 "PHEIC를 구성하지 않음"을 인용했다.2019년 4월,[21][37] 그들은 IHR에 규정된 PHIC 기준의 일부가 아닌 개념인 "현 단계에서 PHIC를 선언하는 것은 추가적인 이익이 없다"고 밝혔다.

2019년 6월 이웃 우간다에서 에볼라 환자가 확인된 후, WHO 사무총장인 테드로스 아드하놈은 에볼라 확산이 [38][39]PHIC가 되었는지 여부를 평가하기 위해 2019년 6월 14일에 전문가 그룹의 세 번째 회의가 개최될 것이라고 발표했다.결론은 콩고민주공화국(DRC)과 이 지역에서 발병은 보건 비상사태였지만 PHEIC의 [40]세 가지 기준을 모두 충족하지 못했다는 것이다.2019년 6월 11일까지 사망자 수가 1,405명에 달하고, 2019년 6월 17일까지 1,440명에 달하지만, PHEIC를 선언하지 않은 이유는 국제적 확산의 전반적인 위험이 낮은 것으로 간주되며, DRC의 경제를 손상시킬 위험이 [41]높기 때문이다.Adhanom은 또한 PHEIC를 선언하는 것은 [42]전염병을 위한 기금을 모으기 위한 부적절한 방법이 될 것이라고 말했다.2019년 7월 DRC를 방문한 후 로리 스튜어트 영국 국방장관은 [43]WHO에 긴급사태를 선포할 것을 요구했다.

북키부의 수도 고마로 확산될 위험이 크다는 것을 인정하면서, 2019년 7월 10일자 워싱턴 포스트에 다니엘 루시와 론 클레인(전 미국 에볼라 대응 코디네이터)에 의해 PHEIC 선언이 발표되었다.그들의 선언은 "발병을 진화하기 위한 궤적이 없는 경우, 그 반대 경로인 심각한 단계적 확대는 여전히 가능하다"고 밝혔다.이 질병이 인근 콩고 고마로 옮겨가거나, 국제공항이 있는 인구 100만 명의 도시로 옮겨가거나, 남수단의 대규모 난민촌으로 건너갈 위험이 높아지고 있다.제한된 수의 백신 투여량이 남아있다면, 어느 쪽이든 대재앙이 될 것이다."[44][45]나흘 뒤인 2019년 7월 14일 국제공항과 이동 인구가 많은 고마에서 에볼라 환자가 확인됐다.그 후 WHO는 2019년 7월 17일 제4차 EC 회의의 재소집을 발표하면서 "지역 비상사태이며, 결코 세계적인 위협이 아니다"라고 공식 발표하고 무역이나 여행의 [46][47]제약 없이 PHEIC로 선포했다.이 선언에 대해 DRC 위원장은 바이러스학자가 이끄는 전문가 위원회와 함께 직접 행동을 감독할 책임을 지고,[48] Oly Ilunga Kalenga 보건장관은 이 선언에 반발하여 사임했다.PHEIC에 대한 검토는 2019년 10월 10일 EC의 제5차 회의에서 계획되었으며, 2019년 10월 18일 발생이 [50]종료됨에 따라 더 이상 PHEIC를 구성하지 않는다는 결정이 내려진 2020년 6월 26일까지 PHEIC로[6] 유지되었다.

COVID-19 (2020)

2020년 1월 30일, WHO는 중국 중부의 우한을 중심으로 [15][51]한 PHEIC인 COVID-19의 발생을 선언했다.

선언 당일 전 세계적으로 확인된 환자는 7818명으로 세계보건기구([52][53]WHO) 6개 지역 중 5개국의 19개국에 영향을 미쳤다.이전에 WHO는 2020년 1월 22일과 23일에 [54][55][56]발병과 관련하여 EC 회의를 열었지만, 필요한 데이터의 부족과 전지구적 [57][58]영향의 규모를 고려할 때 PHEIC를 선언하는 것은 시기상조라고 판단되었다.

WHO는 2020년 [59]3월 11일 COVID-19의 확산을 대유행으로 인정했다.비상대책위원회 제3차 회의는 2020년 [60]4월 30일, 제4차 회의는 7월 [61]31일, 제5차 회의는 [62]10월 29일, [63]제6차 회의는 2021년 1월 14일, [64]제7차 회의는 2021년 4월 15일, [65]제9차 회의는 2021년 10월 9일, 2022년 [66]1월 10일, 제11차 회의는 2022년 4월에 소집되었다.[67]2022년 [update]7월, 제12차 회의 이후에도 COVID-19는 [7]PHEIC로 남아 있다.

몽키두스 (2022년)

2022년 7월 21일 2022년 수두 발생을 위한 제2차 IHR 회의에서 비상대책위원회 위원들은 PHEIC 발행을 놓고 찬성 6명, 반대 [68]9명으로 의견이 갈렸다.2022년 7월 23일, WHO 사무총장은 발병이 [8]PHEIC라고 선언했다.

선언 당일에는 전 세계적으로 1만7186건이 보고돼 6개 WHO 지역 75개국에 모두 영향을 미쳤으며 아프리카 이외 지역에서는 5명, 아프리카 [69]국가에서는 72명이 사망했다.

앞서 WHO는 2022년 6월 23일 EC회의를 열어 42개국 이상에서 2100건 이상의 감염 사례가 발생했다.당시에는 [70]PHEIC 경보 기준에 도달하지 못했습니다.

대답

2018년 첫 4개 선언(2009-2016년)에 대한 조사에서는 WHO가 국제 보건 비상사태에 보다 효과적으로 대응하고 있으며, 이러한 비상사태에 대처하는 국제 시스템은 "강력하다"[5]는 것이 확인되었다.

야생 소아마비를 제외하고 처음 4개 선언에 대한 또 다른 리뷰는 반응이 다양하다는 것을 보여주었다.심각한 발병이나 더 많은 사람들을 위협한 발병은 신속한 PHEIC 선언을 받지 못했고, 연구는 미국 시민들이 감염되었을 때 그리고 긴급 상황이 [4]휴일과 일치하지 않을 때 더 빨리 대응한다는 가설을 세웠다.

선언 이외의 것

2013년 메르스

PHEIC는 2013년 중동호흡기증후군(MERS)[72][73] 발병과 함께 발병하지 않았다.사우디아라비아에서 시작된 메르스는 24개국 이상에 도달했고 2015년까지 580명 이상의 사망자가 발생했지만, 대부분의 사례는 지속적인 지역사회 확산보다는 병원 환경에서 발생했다.그 결과, 무엇이 PHEIC를 구성하는지는 [11][74]불분명해졌다.2020년 5월 현재 876명이 사망했다.[74][75]

비감염 이벤트

PHEIC는 전염병에만 국한된 것이 아니다.화학물질 또는 방사성 [11]물질에 의해 발생하는 사건을 포함할 수 있다.

항균성 내성의 출현과 확산이 PHEIC를 [76][77][78]구성할 수 있는지에 대해서는 논란이 있다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c d WHO의 Q&A(2019년 6월 19일). "International Health Regulations and Emergency Committees". WHO. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b Eccleston-Turner, Mark; McArdle, Scarlett (2020). "The law of responsibility and the World Health Organisation: a case study on the West African ebola outbreak". In Eccleston-Turner, Mark; Brassington, Iain (eds.). Infectious Diseases in the New Millennium: Legal and Ethical Challenges. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 89–110. ISBN 978-3-030-39818-7.

- ^ a b "Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations (2005); About IHR". WHO. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hoffman, Steven J.; Silverberg, Sarah L. (18 January 2018). "Delays in Global Disease Outbreak Responses: Lessons from H1N1, Ebola, and Zika". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (3): 329–333. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304245. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5803810. PMID 29345996.

- ^ a b Hunger, Iris (2018). Coping with Public Health Emergencies of International Concern. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198828945.003.0004. ISBN 978-0191867422.(설명 필요)

- ^ a b c WHO 성명서(2019년 10월 18일)."Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 18 October 2019". www.who.int. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Statement on the twelfth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "WHO Director-General declares the ongoing monkeypox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern". www.who.int. World Health Organization. 23 July 2022. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Mark A. Hall; David Orentlicher; Mary Anne Bobinski; Nicholas Bagley; I. Glenn Cohen (2018). "8. Public Health Law". Health Care Law and Ethics (9th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer. p. 908. ISBN 978-1-4548-8180-3.

- ^ a b c Wilder-Smith, Annelies; Osman, Sarah (8 December 2020). "Public health emergencies of international concern: a historic overview". Journal of Travel Medicine. 27 (8). doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa227. ISSN 1195-1982. PMC 7798963. PMID 33284964.

- ^ a b c d Gostin, Lawrence O.; Katz, Rebecca (2017). "6. The International Health Regulations: the governing framework for global health security". In Halabi, Sam F.; Crowley, Jeffrey S.; Gostin, Lawrence Ogalthorpe (eds.). Global Management of Infectious Disease After Ebola. Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0190604882.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rull, Monica; Kickbusch, Ilona; Lauer, Helen (8 December 2015). "Policy Debate International Responses to Global Epidemics: Ebola and Beyond". International Development Policy. 6 (2). doi:10.4000/poldev.2178. ISSN 1663-9375.

- ^ a b Maxmen, Amy (23 January 2021). "Why did the world's pandemic warning system fail when COVID hit?". Nature. 589 (7843): 499–500. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00162-4. PMID 33500574. S2CID 231768830. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Pillinger, Mara (2 February 2016). "WHO declared a public health emergency about Zika's effects. Here are three takeaways". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2019.(설명 필요)

- ^ a b WHO 성명서(2020년 1월 31일)."Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ a b c WHO 규제(2005년)."Annex 2 of the International Health Regulations (2005)". WHO. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Exter, André den (2015). "Part VI Public Health; Chapter 1.1 International Health Regulations (2005)". International Health Law and Ethics: Basic Documents (3rd ed.). Maklu. p. 540. ISBN 978-9046607923.

- ^ a b Davies, Sara E.; Kamradt-Scott, Adam; Rushton, Simon (2015). Disease Diplomacy: International Norms and Global Health Security. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421416489.

- ^ Lencucha, Raphael; Bandara, Shashika (18 February 2021). "Trust, risk, and the challenge of information sharing during a health emergency". Globalization and Health. 17 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s12992-021-00673-9. ISSN 1744-8603. PMC 7890381. PMID 33602281.

- ^ a b c d e Gostin, Lawrence O.; Katz, Rebeccas (June 2016). "The International Health Regulations: The Governing Framework for Global Health Security". The Milbank Quarterly. 94 (2): 264–313. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12186. PMC 4911720. PMID 27166578.

- ^ a b c Kamradt-Scott, Adam; Eccleston-Turner, Mark (1 April 2019). "Transparency in IHR emergency committee decision making: the case for reform". British Medical Journal Global Health. 4 (2): e001618. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001618. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 6509695. PMID 31139463.

- ^ Sara E. Davies; Adam Kamradt-Scott; Simon Rushton (2015). Disease Diplomacy: International Norms and Global Health Security. JHU Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4214-1648-9.

- ^ a b Director-General (2009). Implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005), Report of the Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 (PDF). WHO. p. 118.

- ^ Renee Dopplick (29 April 2009). "Inside Justice Swine Flu: Legal Obligations and Consequences When the World Health Organization Declares a 'Public Health Emergency of International Concern'". Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Margaret Chan (25 April 2009). "Swine influenza". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Swine flu illness in the United States and Mexico – update 2". World Health Organization. 26 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Simonsen, Lone; Spreeuwenberg, Peter; Lustig, Roger; Taylor, Robert J.; Fleming, Douglas M.; Kroneman, Madelon; Van Kerkhove, Maria D.; Mounts, Anthony W.; Paget, W. John; Hay, Simon I. (26 November 2013). "Global Mortality Estimates for the 2009 Influenza Pandemic from the GLaMOR Project: A Modeling Study". PLOS Medicine. 10 (11): e1001558. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001558. PMC 3841239. PMID 24302890.

- ^ "News Scan: Polio in Pakistan". CIDRAP. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Statement of the Thirty-second Polio IHR Emergency Committee". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak in West Africa declared a public health emergency of international concern". www.euro.who.int. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ WHO (2016년 2월 1일)WHO 사무총장, 지카 비상대책위원회 결과 요약

- ^ "Zika Virus Microcephaly And Guillain–Barré Syndrome Situation Report" (PDF). World Health Organization. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Fifth meeting of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (2005) regarding microcephaly, other neurological disorders and Zika virus". World Health Organization. WHO. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Green, Andrew (20 April 2019). "DR Congo Ebola outbreak not given PHEIC designation". The Lancet. 393 (10181): 1586. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30893-1. PMID 31007190.

- ^ "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 12th April 2019". World Health Organization. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ a b Cohen, Jon (12 April 2019). "Ebola outbreak in Congo still not an international crisis, WHO decides". Science Magazine. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Lancet, The (25 May 2019). "Acknowledging the limits of public health solutions". The Lancet. 393 (10186): 2100. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31183-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 31226033.

- ^ Hunt, Katie. "Ebola outbreak enters 'truly frightening phase' as it turns deadly in Uganda". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (12 June 2019). "Boy, 5, and Grandmother Die in Uganda as More Ebola Cases Emerge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 14 June 2019". World Health Organization. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Souchary, Stephanie (17 June 2019). "Ebola case counts spike again in DRC". CIDRAP. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Soucheray, Stephanie (16 July 2019). "WHO will take up Ebola emergency declaration question for a fourth time". CIDRAP. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (7 July 2019). "Declare Ebola outbreak in DRC an emergency, says UK's Rory Stewart". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Soucheray, Stephanie (11 July 2019). "Three more health workers infected in Ebola outbreak". CIDRAP. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Klain, Ronald A.; Lucey, Daniel (10 July 2019). "Opinion It's time to declare a public health emergency on Ebola". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern". World Health Organization. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak declared public health emergency". BBC News. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa (22 July 2019). "DRC health minister resigns after government takes Ebola reins". CIDRAP. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa; 9 October 2019. "Response resumes following security problems in DRC Ebola hot spot". CIDRAP. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Final Statement on the 8th meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005)". www.who.int. 26 June 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Ramzy, Austin; Jr, Donald G. McNeil (30 January 2020). "W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as the new Coronavirus Spreads". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ WHO 보고서(2020년 1월 30일)."Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV): Situation Report-10" (PDF). WHO. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". WHO. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Fifield, Anna; Sun, Lena H. (23 January 2020). "Nine dead as Chinese coronavirus spreads, despite efforts to contain it". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa (22 January 2020). "WHO decision on nCoV emergency delayed as cases spike". CIDRAP. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ WHO 성명서(2020년 1월 22일)."WHO Director-General's statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus". www.who.int. 22 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Joseph, Andrew (23 January 2020). "WHO declines to declare China virus outbreak a global health emergency". STAT. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ WHO 성명서(2020년 1월 23일)."Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus 2019 (n-CoV) on 23 January 2020". www.who.int. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020". World Health Organization. 20 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the third meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". www.who.int. 1 May 2020. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the fourth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the fifth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the sixth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Statement on the seventh meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Statement on the ninth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Statement on the tenth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". who.int. 19 January 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Statement on the eleventh meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox". World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Monkeypox: 72 deaths reported, with 2,821 cases confirmed, suspected so far this 2022". gulfnews.com. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "WHO emergency committee meets on monkeypox". France 24. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "WHO MERS-CoV". WHO. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Robert Herriman (17 July 2013). "MERS does not constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC): Emergency committee". The Global Dispatch. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ David R Curry (20 July 2013). "WHO Statement: Second Meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee concerning MERS-CoV – PHEIC Conditions Not Met global vaccine ethics and policy". Center for Vaccine Ethics and Policy. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ a b Mullen, Lucia; Potter, Christina; Gostin, Lawrence O.; Cicero, Anita; Nuzzo, Jennifer B. (1 June 2020). "An analysis of International Health Regulations Emergency Committees and Public Health Emergency of International Concern Designations" (PDF). BMJ Global Health. 5 (6): e002502. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002502. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 7299007. PMID 32546587.

- ^ "WHO Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Saudi Arabia". WHO. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Can the International Health Regulations apply to antimicrobial resistance?". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Wernli, Didier; Haustein, Thomas; Conly, John; Carmeli, Yehuda; Kickbusch, Ilona; Harbarth, Stephan (April 2011). "A call for action: the application of The International Health Regulations to the global threat of antimicrobial resistance". PLOS Medicine. 8 (4): e1001022. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001022. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3079636. PMID 21526227.

- ^ Kamradt-Scott, Adam (19 April 2011). "A Public Health Emergency of International Concern? Response to a Proposal to Apply the International Health Regulations to Antimicrobial Resistance". PLOS Medicine. 8 (4): e1001021. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001021. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3080965. PMID 21526165.

추가 정보

- 폴리오 바이러스의 국제적 확산에 관한 제23차 IHR 비상 위원회의 성명.WHO, 2020년 1월 7일