지카바이러스

Zika virus| 지카바이러스 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 지카 바이러스의 전자현미경 사진입니다. 바이러스 입자(디지털 보라색)는 직경이 40nm이고 외부 외피와 조밀한 내부 코어를 가지고 있습니다.[1] | |

| |

| 지카 바이러스 캡시드 모델, 체인 색상, PDB 엔트리 5ire[2] | |

| 바이러스분류 | |

| (순위 없음): | 바이러스 |

| 영역: | 리보비리아 |

| 왕국: | 오르소나비래 |

| 문: | 키트리노비리코타 |

| 클래스: | Flasuviricetes |

| 순서: | 아마릴로비랄레스 |

| 가족: | 플라비바이러스과 |

| 속: | 플라비바이러스 |

| 종: | 지카바이러스 |

지카 바이러스(ZikV; 발음 / ˈzi ːk ə/ 또는 / ˈz ək ɪ/)는 플라비바이러스과에 속하는 바이러스입니다. A. egypti 및 A. albopictus와 같은 주간 활동성 이집트숲모기에 의해 전파됩니다.[5] 그 이름은 1947년에 바이러스가 처음 분리된 우간다의 지카 숲에서 유래했습니다.[6] 지카 바이러스는 뎅기열, 황열병, 일본뇌염, 웨스트 나일 바이러스와 한 속을 공유합니다.[6] 1950년대부터 아프리카에서 아시아에 이르는 좁은 적도대 내에서 발생하는 것으로 알려져 왔습니다. 2007년부터 2016년까지[update] 바이러스가 동쪽으로 퍼지면서 태평양을 건너 아메리카 대륙으로 확산되어 2015-2016년 지카 바이러스 유행으로 이어졌습니다.[7]

지카열 또는 지카 바이러스 질병으로 알려진 이 감염은 종종 아주 가벼운 형태의 뎅기열과 유사한 증상을 일으키거나 가벼운 증상만을 유발합니다.[5] 특별한 치료법은 없지만 파라세타몰(아세트아미노펜)과 휴식이 증상에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[8] 2019년 4월 현재 임상용으로 승인된 백신은 없으나 현재 다수의 백신이 임상시험 중에 있습니다.[9][10][11] 지카는 임산부에서 아기로 퍼질 수 있습니다. 이로 인해 소두증, 심각한 뇌 기형 및 기타 선천적 결함이 발생할 수 있습니다.[12][13] 성인의 지카 감염은 드물게 길랭-바레 증후군을 유발할 수 있습니다.[14]

2016년 1월, 미국 질병통제예방센터(CDC)는 강화된 예방 조치를 사용하는 것을 포함한 피해 국가에 대한 여행 안내와 임산부에 대한 여행 연기를 고려하는 것을 포함한 지침을 발표했습니다.[15][16] 다른 정부나 보건 기관들도 비슷한 여행 경보를 내렸고,[17][18][19] 콜롬비아, 도미니카 공화국, 푸에르토리코, 에콰도르, 엘살바도르, 자메이카는 여성들에게 위험성에 대해 더 많이 알려질 때까지 임신을 연기하라고 권고했습니다.[18][20]

바이러스학

지카 바이러스는 플라비바이러스과와 플라비바이러스속에 속하므로 뎅기열, 황열병, 일본뇌염, 웨스트나일 바이러스와 관련이 있습니다. 다른 플라비바이러스와 마찬가지로 지카 바이러스는 외피와 20면체로 되어 있으며, 비분절된 단일가닥 10킬로베이스의 포지티브 센스 RNA 유전체를 가지고 있습니다. 스폰드웨니 바이러스와 가장 밀접한 관련이 있으며 스폰드웨니 바이러스 계통에서 알려진 두 가지 바이러스 중 하나입니다.[21][22][23][24][25]

포지티브 센스 RNA 유전체는 바이러스 단백질로 직접 번역될 수 있습니다. 비슷한 크기의 웨스트 나일 바이러스와 같은 다른 플라비바이러스에서와 마찬가지로 RNA 유전체는 7개의 비구조적 단백질과 3개의 구조적 단백질을 단일 다단백질(Q32ZE1)의 형태로 암호화합니다.[27] 구조 단백질 중 하나가 바이러스를 캡슐화합니다. 이 단백질은 플라비바이러스 외피 당단백질로, 숙주 세포의 엔도솜 막에 결합하여 세포내이입을 시작합니다.[28] RNA 유전체는 12kDa 캡시드 단백질의 사본과 함께 뉴클레오캡시드를 형성합니다. 뉴클레오캡시드는 차례로 두 개의 바이러스 당단백질로 변형된 숙주 유래 막 안에 둘러싸여 있습니다. 바이러스 유전체 복제는 단일 가닥의 포지티브 센스 RNA(ssRNA(+) 유전체에서 이중 가닥 RNA를 만든 후 전사 및 복제하여 바이러스 mRNA와 새로운 ssRNA(+) 유전체를 제공하는 데 의존합니다.[29][30]

세포가 지카 바이러스에 감염된 지 6시간이 지나면 세포 내 액포와 미토콘드리아가 부풀어 오르기 시작한다는 종단 연구 결과가 나왔습니다. 이 부종은 매우 심해져 세포 사멸, 즉 부종증이라고도 합니다. 이러한 형태의 프로그램된 세포 사멸은 유전자 발현을 필요로 합니다. IFITM3는 바이러스 부착을 차단하여 바이러스 감염으로부터 보호할 수 있는 세포 내 막횡단 단백질입니다. 세포는 IFITM3 수치가 낮을 때 지카 감염에 가장 취약합니다. 일단 세포가 감염되면 바이러스가 소포체를 재구조화하여 큰 액포를 형성하여 세포가 죽게 됩니다.[31]

아프리카 계통과 아시아 계통의 두 가지 지카 계통이 있습니다.[32] 계통발생학적 연구에 따르면 아메리카 대륙에 퍼진 바이러스는 아프리카 유전자형과 89% 동일하지만 2013~2014년 발병 당시 프랑스령 폴리네시아에서 유통된 아시아 계통과 가장 밀접한 관련이 있습니다.[32][33][34]

아시아 계통은 1928년경에 처음으로 진화한 것으로 보입니다.[35]

변속기

이 바이러스의 척추동물 숙주는 주로 사람에게 가끔씩만 전염되는 소위 동물성 모기-원숭이-모기 주기를 가진 원숭이들이었습니다. 2007년 이전에 지카는 "인간에게, 심지어 고도로 동물성이 있는 지역에서도, 인지된 '스필오버' 감염을 거의 일으키지 않았습니다." 그러나 드물게 다른 아르보 바이러스가 사람의 질병으로 확립되어 모기-사람-모기 순환으로 전파되는데, 예를 들어 황열병 바이러스와 뎅기열 바이러스(둘 다 플라비바이러스), 치쿤구니아 바이러스(토가바이러스) 등이 이에 해당합니다.[36] 유행병의 원인은 알려지지 않았지만, 같은 종의 모기 매개체를 감염시키는 관련 아르보 바이러스인 뎅기열은 특히 도시화와 세계화에 의해 심화되는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[37] 지카는 주로 이집트숲모기에 의해 전파되며,[38] 성적 접촉이나[39] 수혈을 통해서도 전염될 수 있습니다.[40] 지카 바이러스의 기본 재생산 수(R0, 전염성의 척도)는 1.4에서 6.6 사이로 추정되었습니다.[41]

2015년, 라틴 아메리카와 카리브해 지역에서 지카의 급속한 확산에 대한 뉴스 보도가 주목을 끌었습니다.[42] 당시 범미보건기구는 바베이도스, 볼리비아, 브라질, 콜롬비아, 도미니카공화국, 에콰도르, 엘살바도르, 프랑스령 기아나, 과들루프, 과테말라, 가이아나, 아이티, 온두라스, 마르티니크, 멕시코, 파나마, 파라과이, 푸에르토리코, 세인트마틴, 수리남, 베네수엘라.[43][44][45] 2016년 8월까지 50개 이상의 국가에서 지카 바이러스의 활발한 (현지적인) 전염이 발생했습니다.[46]

모기

지카는 주로 낮에 활동하는 이집트숲모기 암컷에 의해 전파됩니다.[47][48] 모기는 알을 낳기 위해 피를 먹고 살아야 합니다.[49]: 2 이 바이러스는 A. 아프리카누스, A. picoargenteus, A. furcifer, A. hensilli, A. luteocephalus 및 A. vittatus와 같은 Aedes 속의 많은 수목 모기 종에서도 분리되었으며 모기에서 외부 배양 기간은 약 10일입니다.[24]

벡터의 실제 범위는 아직 알려지지 않았습니다. 지카는 아노펠레스 쿠스타니, Mansonia uniformis 및 Culex perfuscus와 함께 더 많은 종의 이집트숲모기에서 발견되었지만 이것만으로 매개체로 입증되지는 않습니다.[48] 바이러스의 존재를 감지하기 위해서는 일반적으로 RT-PCR 기술을 사용하여 실험실에서 유전 물질을 분석해야 합니다. 훨씬 저렴하고 빠른 방법은 모기의 머리와 가슴에 빛을 비추고, 근적외선 분광법을 이용해 바이러스의 특징인 화합물을 검출하는 것입니다.[50]

호랑이 모기인 A. albopictus에 의한 전염은 2007년 가봉에서 발생한 도시 발병에서 보고되었으며, 가봉은 이 나라를 새로 침범하여 치쿤구니아와 뎅기 바이러스가 동시에 발생하는 주요 매개체가 되었습니다.[51] 바이러스를 가지고 있는 사람이 A. albopictus가 흔한 다른 지역으로 여행을 가면 새로운 발병이 일어날 수 있습니다.[52]

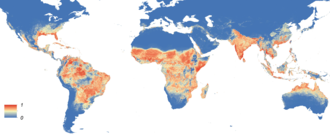

지카를 전파하는 모기 종의 분포는 지카의 잠재적인 사회적 위험을 구분할 수 있습니다. 가장 많이 인용되는 지카(Zika) 운송업체인 A. 이집트(A. egypti)의 전 세계적인 무역과 여행으로 인해 전 세계적인 유통이 확대되고 있습니다.[53] 이집트숲모기(A. Egypti) 분포는 이제 기록된 것 중 가장 광범위합니다 – 북아메리카와 심지어 유럽 주변부(Madeira, 네덜란드, 그리고 북동 흑해 연안)를 포함한 남극 대륙을 제외한 모든 대륙의 부분에서 말입니다.[54] 워싱턴 DC의 캐피톨 힐 인근에서 지카를 옮길 수 있는 모기가 발견되었으며 유전적 증거는 그들이 이 지역에서 최소 4번 연속 겨울을 보냈다는 것을 시사합니다. 연구 저자들은 모기가 북부 기후에서 지속성을 위해 적응하고 있다고 결론지었습니다.[55] 지카 바이러스는 감염 후 일주일 정도 모기를 통해 전염되는 것으로 보입니다. 이 바이러스는 정액을 통해 전염될 때 감염 후(최소 2주) 더 오랜 기간 동안 감염되는 것으로 생각됩니다.[56][57]

지카의 생태학적 틈새에 대한 연구는 지카가 뎅기열보다 강수량과 기온의 변화에 더 큰 영향을 받아 열대 지역에 국한될 가능성이 높다는 것을 시사합니다. 그러나 지구 온도가 상승하면 질병 매개체가 더 북쪽으로 범위를 확장하여 지카가 따를 수 있습니다.[58]

성적인

지카는 남성과 여성에서 성적 파트너로 전염될 수 있습니다. 대부분의 알려진 사례는 증상이 있는 남성에서 여성으로 전염되는 것입니다.[39][59][60] 2016년 4월 현재, 지카의 성적 전염은 2015년 발병 당시 아르헨티나, 호주, 프랑스, 이탈리아, 뉴질랜드, 미국 등 6개국에서 기록되었습니다.[14] ZIKV는 정액에서 수개월 동안 지속될 수 있으며 바이러스 RNA가 최대 1년까지 검출됩니다.[61] 이 바이러스는 인간 고환에서 복제되어 고환 대식세포, 관주위 세포 및 정자 전구체인 생식 세포를 포함한 여러 세포 유형을 감염시킵니다.[62] 정액 파라미터는 증상 발생 후 몇 주 동안 환자에서 변경될 수 있으며 정자는 감염될 수 있습니다.[63] CDC는 2016년 10월부터 지카와 함께 지역을 여행한 남성에게 증상이 발생하지 않더라도 바이러스가 여전히 전염되기 때문에 복귀 후 최소 6개월 동안 콘돔을 사용하거나 성관계를 갖지 말 것을 권고했습니다.[64]

임신

지카 바이러스는 수직(또는 "엄마 대 아이") 전염, 임신 중 또는 분만 중에 전파될 수 있습니다.[12][65] 임신 중 감염은 태어나지 않은 아이의 신경 발달 변화와 관련이 있습니다.[66] 감염의 심각한 진행은 태어나지 않은 아이의 소두증 발병과 관련이 있는 반면, 가벼운 감염은 잠재적으로 나중에 신경 인지 장애로 이어질 수 있습니다.[67][68][69] 지카 발병 이후 소두증 이외의 선천성 뇌 이상도 보고되고 있습니다.[70] 쥐를 대상으로 한 연구에 따르면 뎅기 바이러스에 대한 모체 면역이 지카에 의한 태아 감염을 강화하고 소두증 표현형을 악화시키며 임신 중 손상을 강화할 수 있다고 제안했지만 이것이 사람에게서 발생하는지 여부는 알려지지 않았습니다.[71][72]

수혈

2016년[update] 4월 현재 브라질에서 수혈을 통한 지카 전염 사례가 전 세계적으로 2건 보고되었으며,[40] 이후 미국 식품의약국(FDA)은 헌혈자 선별 검사와 고위험 헌혈자 4주 연기를 권고했습니다.[73][74] 2013년 11월과 2014년 2월의 헌혈자 중 2.8%(42명)가 지카 RNA 양성 반응을 보였으며, 헌혈 당시 모두 무증상이었다는 프랑스 폴리네시아 지카 사태 당시 헌혈자 선별 연구에 따르면 잠재적 위험이 의심되었습니다. 양성 기증자 중 11명은 기증 후 지카열 증상을 보고했지만 34개 샘플 중 3개 샘플만 배양액이 증가했습니다.[75]

병인

지카 바이러스는 모기의 중장 상피 세포와 침샘 세포에서 복제됩니다. 5-10일이 지나면 모기의 침에서 바이러스를 찾을 수 있습니다. 모기의 침을 사람의 피부에 접종하면 바이러스가 표피 각질세포, 피부 섬유아세포, 랑게르한스 세포를 감염시킬 수 있습니다. 바이러스의 발병기전은 림프절과 혈류로의 확산과 함께 계속될 것으로 추정됩니다.[21][76] 플라비바이러스는 세포질에서 복제되지만 지카항원은 감염된 세포핵에서 발견되었습니다.[77]

NS4A라는 번호의 바이러스 단백질은 새로운 뉴런의 성장을 조절하는 경로를 가로채 뇌 성장을 방해하기 때문에 작은 머리 크기(소두증)로 이어질 수 있습니다.[78] 초파리에서는 NS4A와 이웃 NS4B 모두 눈의 성장을 제한합니다.[79]

지카열

지카열(Zika fever, 일명 지카 바이러스 질환)은 지카 바이러스에 의해 발생하는 질병입니다.[80] 약 80%의 사례가 무증상인 것으로 추정되지만 데이터 품질의 광범위한 변화로 인해 이 수치의 정확성이 방해를 받고 발병 상황에 따라 수치가 크게 달라질 수 있습니다.[81] 증상이 있는 경우는 대개 경미하고 뎅기열과 유사할 수 있습니다.[80][82] 증상으로는 발열, 붉은 눈, 관절통, 두통, 황반성 발진 등이 나타날 수 있습니다.[80][83][84] 증상은 일반적으로 7일 미만 지속됩니다.[83] 초기 감염 동안 보고된 사망자는 발생하지 않았습니다.[82] 임신 중 감염은 일부 아기의 소두증 및 기타 뇌 기형을 유발합니다.[12][13] 성인의 감염은 길랭-바레 증후군과 관련이 있으며 지카 바이러스는 인간 슈반 세포를 감염시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[82][85]

진단은 환자가 아플 때 혈액, 소변 또는 타액에서 지카 바이러스 RNA의 존재 여부를 검사하는 것입니다.[80][83] 2019년에는 세인트 워싱턴 대학교의 연구 결과를 바탕으로 진단 검사를 개선했습니다. 혈청에서 지카 감염을 검출하는 루이, FDA 시판 허가 받았습니다.[86]

예방에는 질병이 발생한 지역에서 모기에 물리는 것을 줄이고 콘돔을 적절히 사용하는 것이 포함됩니다.[83][87] 물림을 방지하기 위한 노력으로는 DEET 또는 피카리딘 계열의 방충제 사용, 옷, 모기장으로 몸의 많은 부분을 덮고 모기가 번식하는 물을 제거하는 것 등이 있습니다.[80] 백신은 없습니다.[83] 보건 당국은 2015-2016년 지카 발병으로 피해를 입은 지역의 여성들은 임신을 연기하는 것을 고려하고 임산부들은 이 지역으로 여행하지 말 것을 권고했습니다.[83][88] 특별한 치료법은 없지만, 파라세타몰(아세트아미노펜)과 휴식이 증상에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[83] 병원에 입원하는 것은 거의 필요하지 않습니다.[82]

치료

지카 바이러스에 감염된 사람은 수분을 충분히 섭취하고 누워서, 열과 통증을 액체 용액으로 치료하는 것이 좋습니다. 아세트아미노펜이나 파라세타몰 같은 약을 복용하면 열과 통증을 완화하는 데 도움이 됩니다.[according to whom?] 예를 들어, 미국 CDC를 참조하면 아스피린과 같은 소염제와 비스테로이드제를 복용하는 것은 권장되지 않습니다.[89] 해당 환자가 이미 다른 질환으로 치료를 받고 있는 경우, 다른 약물이나 추가 치료를 받기 전에 담당 의사에게 알리는 것이 좋습니다.[90]

백신개발

세계보건기구는 임산부에게 사용하기 안전한 불활성화 백신 및 기타 비생식 백신을 개발하는 것이 우선되어야 한다고 제안했습니다.[91]

2016년[update] 3월 현재 18개 기업과 기관이 지카 백신을 개발하고 있지만, 약 10년 동안 백신이 널리 보급될 것 같지 않다고 말합니다.[91][92]

FDA는 2016년 6월 지카 백신에 대한 인체 임상시험을 처음으로 승인했습니다.[93] 2017년 3월, DNA 백신이 임상 2상을 승인받았습니다. 이 백신은 지카 바이러스 외피 단백질의 유전자를 발현하는 플라스미드로 알려진 작고 원형의 DNA 조각으로 구성되어 있습니다. 백신에는 바이러스의 전체 서열이 포함되어 있지 않기 때문에 감염을 일으킬 수 없습니다.[94] 2017년 4월 현재 서브유닛과 불활성화 백신 모두 임상에 진입하였습니다.[95]

역사

원숭이와 모기의 바이러스 분리, 1947년

이 바이러스는 1947년 4월 황열병 연구소의 과학자들에 의해 빅토리아 호수 근처 우간다 지카 숲의 우리에 놓여진 붉은털 원숭이로부터 처음 분리되었습니다.[99] 1948년 1월 같은 장소에서 모기 A. 아프리카누스로부터 두 번째 분리가 이어졌습니다.[100] 원숭이가 열이 났을 때, 연구원들은 1948년 지카라고 이름 지어진 "여과성 전염성 물질"을 혈청에서 분리했습니다.[101]

인체 감염의 최초의 증거, 1952년

지카는 1952년 발표된 우간다의 혈청학적 조사 결과에서 인간을 감염시키는 것으로 처음 알려졌습니다.[102] 테스트한 99명의 사람 혈액 샘플 중 6.1%가 중화항체를 가지고 있었습니다. 1954년 황열병으로 의심되는 황달의 발병 조사의 일환으로 연구원들은 환자로부터 바이러스를 분리했다고 보고했지만,[103] 이 병원체는 나중에 밀접하게 관련된 스폰드웨니 바이러스인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[104] 스폰드웨니는 1956년에 보고된 한 연구자에게서도 자가 감염의 원인으로 밝혀졌습니다.[105]

적도 아프리카와 아시아로 확산, 1951~현재

몇몇 아프리카와 아시아 국가들에서의 후속 혈청학적 연구는 이 바이러스가 이 지역들의 인간 집단 내에 널리 퍼져 있었다는 것을 나타냈습니다.[101] 인체 감염의 첫 번째 실제 사례는 1964년 심슨에 의해 확인되었는데,[106] 심슨은 모기로부터 바이러스를 분리하던 중 그 자신이 감염되었습니다.[101] 그때부터 2007년까지 아프리카와 동남아시아에서 발생한 지카 감염의 추가 확인된 인간 사례는 13건에 불과했습니다.[107] 2017년에 발표된 연구에 따르면 지카 바이러스는 소수의 사례만 보고되었지만 1992년에서 2016년 사이에 수집된 혈액 샘플에서 ZIKV IgM 항체가 테스트되었을 때 지난 20년 동안 서아프리카에서 묵묵히 순환되었습니다.[108] 2017년 앙골라는 지카열 환자 2명을 보고했습니다.[109] 지카는 2016년 현재 탄자니아에서도 발생하고 있습니다.[110]

미크로네시아, 2007

2007년 4월 미크로네시아 연방의 Yap섬에서 아프리카와 아시아 이외의 지역에서 최초로 발병하였으며, 발진, 결막염, 관절통을 특징으로 하며, 이는 처음에는 뎅기열, 치쿤구니아 또는 로스강 질병으로 생각되었습니다.[111] 급성 병기 환자의 혈청 샘플에는 지카의 RNA가 포함되어 있었습니다. 확진자는 49명, 미확진자는 59명, 입원자는 없고 사망자는 없었습니다.[112]

2013–2014

2013년 10월 오세아니아의 첫 발병 이후 프랑스령 폴리네시아에 감염된 것으로 추정되는 11%의 인구가 길랭-바레 증후군을 나타냈습니다. ZIKV의 확산은 뉴칼레도니아, 이스터섬, 쿡 제도로 이어졌으며 2014년 1월까지 1385명의 환자가 확인되었습니다. 같은 해 이스터 섬에서는 51건의 사례를 인정했습니다. 호주는 2012년부터 사례를 보기 시작했습니다. 인도네시아 등 감염국에서 귀국한 여행객들이 가져온 것으로 조사됐습니다. 뉴질랜드도 귀국 외국인 여행객을 통한 감염률 증가를 경험했습니다. 오늘날 지카를 경험하는 오세아니아 국가는 뉴칼레도니아, 바누아투, 솔로몬 제도, 마셜 제도, 아메리칸 사모아, 사모아, 통가입니다.[113]

2013년과 2014년 사이에 프랑스령 폴리네시아, 이스터 섬, 쿡 제도, 뉴칼레도니아에서 추가 전염병이 발생했습니다.[4]

아메리카, 2015-현재

2015년과 2016년에 아메리카 대륙에서 유행이 있었습니다. 발병은 2015년 4월 브라질에서 시작되어 남미, 중미, 북미, 카리브해의 다른 국가로 확산되었습니다. 2016년 1월, WHO는 이 바이러스가 연말까지 대부분의 아메리카 대륙에 퍼질 가능성이 있다고 말했습니다.[114] 그리고 2016년 2월, WHO는 브라질에서 보고된 소두증과 길랭-바레 증후군의 집단 발병을 선언했는데, 이는 지카 발병과 관련이 있는 것으로 강하게 의심됩니다. 이는 국제 공중보건 비상사태입니다.[6][115][116][117] 브라질에서는 150만 명이 지카에 감염된 것으로 추정됐으며,[118] 2015년 10월부터 2016년 1월 사이에 3,500건 이상의 소두증 사례가 보고됐습니다.[119]

많은 나라들이 여행 경보를 발령했고, 이번 발병은 관광 산업에 상당한 영향을 미칠 것으로 예상됐습니다.[6][120] 몇몇 국가들은 자국민들에게 바이러스와 태아 발달에 미치는 영향에 대해 더 많이 알려질 때까지 임신을 연기하라고 권고하는 이례적인 조치를 취했습니다.[20] 2016년 리우데자네이루에서 개최된 하계 올림픽을 계기로 전 세계 보건 관계자들은 브라질과 국제 선수들과 관광객들이 귀국했을 때 바이러스가 확산될 수 있는 잠재적인 위기에 대한 우려를 표명했습니다. 일부 연구원들은 3주 동안 1~2명의 관광객만 감염될 수도 있고, 10만 명당 약 3.2명의 관광객이 감염될 수도 있다고 추측했습니다.[121] 2016년 11월, 세계보건기구는 지카 바이러스가 여전히 "매우 중대하고 장기적인 문제"를 나타낸다고 언급하면서 지카 바이러스가 더 이상 세계적인 비상사태가 아니라고 선언했습니다.[122]

2017년 8월 기준으로 아메리카 대륙의 새로운 지카 바이러스 환자 수는 급격히 감소했습니다.[123]

인도, 방글라데시

2017년 5월 15일 구자라트 주에서 3건의 인도 지카 바이러스 감염 사례가 보고되었습니다.[124][125] 2018년 말까지 라자스탄에서 최소 159건, 마디아 프라데시에서 127건의 환자가 발생했습니다.[126]

2021년 7월 인도 케랄라주에서 첫 지카 바이러스 감염 사례가 보고되었습니다. 첫 확진자 이후 이전에 증상을 보였던 19명이 검사를 받았고, 이 중 13명이 양성 반응을 보여 지카가 적어도 2021년 5월부터 케랄라에서 유통되고 있음을 보여주었습니다.[127] 2021년 8월 6일까지 케랄라에서 65건의 사례가 보고되었습니다.[128]

2021년 10월 22일 칸푸르의 인도 공군 장교가 지카 바이러스 양성 반응을 보여 인도 우타르프라데시주에서 최초로 보고된 사례가 되었습니다.[129]

2016년 3월 22일, 로이터 통신은 지카가 회고적 연구의 일환으로 방글라데시 치타공의 한 노인의 2014년 혈액 샘플에서 분리되었다고 보도했습니다.[130]

동아시아

2016년 8월에서 11월 사이에 싱가포르에서 455건의 지카 바이러스 감염이 확인되었습니다.[131][132]

2023년 태국에서 722건의 지카 바이러스 환자가 보고되었습니다.[133] 2019-2022년 로베르트 코흐 연구소는 독일로 수입된 29건의 지카바이러스 사례를 보고했습니다. 2023년 전체 수입 지카 바이러스 사례 16건 중 10건은 태국 여행 후 진단을 받은 것으로 전체 지카 바이러스 사례의 62%가 상대적, 절대적으로 크게 증가했습니다.[134]

참고문헌

- ^ Goldsmith C (18 March 2005). "TEM image of the Zika virus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Sirohi D, Chen Z, Sun L, Klose T, Pierson TC, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ (April 2016). "The 3.8 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus". Science. 352 (6284): 467–470. Bibcode:2016Sci...352..467S. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5316. PMC 4845755. PMID 27033547.

- ^ "How to pronounce Zika". HowToPronounce.com.

- ^ a b "Zika virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (6): 1090. June 2014. doi:10.3201/eid2006.ET2006. PMC 4036762. PMID 24983096.

- ^ a b c Malone RW, Homan J, Callahan MV, Glasspool-Malone J, Damodaran L, Schneider A, et al. (March 2016). "Zika Virus: Medical Countermeasure Development Challenges". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (3): e0004530. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004530. PMC 4774925. PMID 26934531.

- ^ a b c d Sikka V, Chattu VK, Popli RK, Galwankar SC, Kelkar D, Sawicki SG, et al. (11 February 2016). "The Emergence of Zika Virus as a Global Health Security Threat: A Review and a Consensus Statement of the INDUSEM Joint working Group (JWG)". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 8 (1): 3–15. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.176140. PMC 4785754. PMID 27013839.

- ^ Mehrjardi MZ (1 January 2017). "Is Zika Virus an Emerging TORCH Agent? An Invited Commentary". Virology. 8: 1178122X17708993. doi:10.1177/1178122X17708993. PMC 5439991. PMID 28579764.

- ^ "Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment". Zika virus. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Abbink, P; Stephenson, KE; Barouch, DH (19 June 2018). "Zika virus vaccines". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 16 (10): 594–600. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0039-7. PMC 6162149. PMID 29921914.

- ^ Fernandez, E; Diamond, MS (19 April 2017). "Vaccination strategies against Zika virus". Current Opinion in Virology. 23: 59–67. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.006. PMC 5576498. PMID 28432975.

- ^ "Zika Virus Vaccines NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". www.niaid.nih.gov.

- ^ a b c Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR (May 2016). "Zika Virus and Birth Defects--Reviewing the Evidence for Causality". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (20): 1981–1987. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. PMID 27074377. S2CID 20675635.

- ^ a b "CDC concludes Zika causes microcephaly and other birth defects". CDC. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Zika virus microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome situation report" (PDF). World Health Organization. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Zika Virus in the Caribbean". Travelers' Health: Travel Notices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 January 2016.

- ^ Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman D, Fischer M, Ellington SR, Callaghan WM, Jamieson DJ (January 2016). "Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak--United States, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (2): 30–33. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6502e1. PMID 26796813.

- ^ "Zika virus: Advice for those planning to travel to outbreak areas". ITV Report. ITV News. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Pregnant Irish women warned over Zika virus in central and South America". RTÉ News. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Zika: Olympics plans announced by Rio authorities". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

The Rio de Janeiro authorities have announced plans to prevent the spread of the Zika virus during the Olympic Games later this year. ... The US, Canada and EU health agencies have issued warnings saying pregnant women should avoid traveling to Brazil and other countries in the Americas which have registered cases of Zika.

- ^ a b "Zika virus triggers pregnancy delay calls". BBC News. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ a b Knipe DM, Howley PM (2007). Fields Virology (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1156, 1199. ISBN 978-0-7817-6060-7.

- ^ a b Faye O, Freire CC, Iamarino A, Faye O, de Oliveira JV, Diallo M, et al. (9 January 2014). "Molecular evolution of Zika virus during its emergence in the 20(th) century". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (1): e2636. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002636. PMC 3888466. PMID 24421913.

- ^ Cao-Lormeau VM, Roche C, Teissier A, Robin E, Berry AL, Mallet HP, et al. (June 2014). "Zika virus, French polynesia, South pacific, 2013". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (6): 1085–1086. doi:10.3201/eid2006.140138. PMC 4036769. PMID 24856001.

- ^ a b Hayes EB (September 2009). "Zika virus outside Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (9): 1347–1350. doi:10.3201/eid1509.090442. PMC 2819875. PMID 19788800.

- ^ Kuno G, Chang GJ (1 January 2007). "Full-length sequencing and genomic characterization of Bagaza, Kedougou, and Zika viruses". Archives of Virology. 152 (4): 687–696. doi:10.1007/s00705-006-0903-z. PMID 17195954.

- ^ Goodsell DS (2016). "Zika Virus". RCSB Protein Data Bank. doi:10.2210/rcsb_pdb/mom_2016_5.

- ^ Cox BD, Stanton RA, Schinazi RF (August 2015). "Predicting Zika virus structural biology: Challenges and opportunities for intervention". Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy. 24 (3–4): 118–126. doi:10.1177/2040206616653873. PMC 5890524. PMID 27296393.

- ^ Dai L, Song J, Lu X, Deng YQ, Musyoki AM, Cheng H, et al. (May 2016). "Structures of the Zika Virus Envelope Protein and Its Complex with a Flavivirus Broadly Protective Antibody". Cell Host & Microbe. 19 (5): 696–704. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.013. PMID 27158114.

- ^ "ViralZone: Zika virus (strain Mr 766)". viralzone.expasy.org. SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Pierson TC, Diamond MS (April 2012). "Degrees of maturity: the complex structure and biology of flaviviruses". Current Opinion in Virology. 2 (2): 168–175. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.011. PMC 3715965. PMID 22445964.

- ^ Monel B, Compton AA, Bruel T, Amraoui S, Burlaud-Gaillard J, Roy N, et al. (June 2017). "Zika virus induces massive cytoplasmic vacuolization and paraptosis-like death in infected cells". The EMBO Journal. 36 (12): 1653–1668. doi:10.15252/embj.201695597. PMC 5470047. PMID 28473450.

- ^ a b Enfissi A, Codrington J, Roosblad J, Kazanji M, Rousset D (January 2016). "Zika virus genome from the Americas". Lancet. 387 (10015): 227–228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00003-9. PMID 26775124.

- ^ Zanluca C, Melo VC, Mosimann AL, Santos GI, Santos CN, Luz K (June 2015). "First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 110 (4): 569–572. doi:10.1590/0074-02760150192. PMC 4501423. PMID 26061233.

- ^ a b Lanciotti RS, Lambert AJ, Holodniy M, Saavedra S, Signor L (May 2016). "Phylogeny of Zika Virus in Western Hemisphere, 2015". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (5): 933–935. doi:10.3201/eid2205.160065. PMC 4861537. PMID 27088323.

- ^ Ramaiah A, Dai L, Contreras D, Sinha S, Sun R, Arumugaswami V (July 2017). "Comparative analysis of protein evolution in the genome of pre-epidemic and epidemic Zika virus". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 51: 74–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2017.03.012. PMID 28315476.

- ^ Fauci AS, Morens DM (February 2016). "Zika Virus in the Americas--Yet Another Arbovirus Threat". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (7): 601–604. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1600297. PMID 26761185. S2CID 4377569.

- ^ Gubler DJ (December 2011). "Dengue, Urbanization and Globalization: The Unholy Trinity of the 21(st) Century". Tropical Medicine and Health. 39 (4 Suppl): 3–11. doi:10.2149/tmh.2011-S05. PMC 3317603. PMID 22500131.

- ^ "Zika virus found in common house mosquitoes in Brazil". CNN. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ a b Oster AM, Russell K, Stryker JE, Friedman A, Kachur RE, Petersen EE, et al. (April 2016). "Update: Interim Guidance for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus--United States, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (12): 323–325. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6512e3. PMID 27032078.

- ^ a b Vasquez AM, Sapiano MR, Basavaraju SV, Kuehnert MJ, Rivera-Garcia B (April 2016). "Survey of Blood Collection Centers and Implementation of Guidance for Prevention of Transfusion-Transmitted Zika Virus Infection--Puerto Rico, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (14): 375–378. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6514e1. PMID 27078190.

- ^ "Assessing the global threat from Zika virus". Science Magazine. 12 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016 – via www.sciencemagazinedigital.org.

- ^ Moloney A (22 January 2016). "FACTBOX – Zika virus spreads rapidly through Latin America, Caribbean". Thomson Reuters Foundation News. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Mitchell C (18 January 2016). "As the Zika virus spreads, PAHO advises countries to monitor and report birth anomalies and other suspected complications of the virus". Media Center. Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Mitchell C (2 February 2016). "PAHO Statement on Zika Virus Transmission and Prevention". PAHO.org. Pan American Health Organization.

- ^ "5 things you need to know about Zika". CNN. 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Zika Virus". All Countries & Territories with Active Zika Virus Transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Abushouk AI, Negida A, Ahmed H (November 2016). "An updated review of Zika virus". Journal of Clinical Virology. 84: 53–58. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2016.09.012. PMID 27721110.

- ^ a b Ayres CF (March 2016). "Identification of Zika virus vectors and implications for control". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): 278–279. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00073-6. PMID 26852727.

- ^ Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Dengue Branch. "Dengue and the Aedes aegypti mosquito" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Wishart S (July–August 2018). "Shining a light on Zika". New Zealand Geographic (152): 25.

- ^ Grard G, Caron M, Mombo IM, Nkoghe D, Mboui Ondo S, Jiolle D, et al. (February 2014). "Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa)--2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus?". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (2): e2681. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002681. PMC 3916288. PMID 24516683.

- ^ Zammarchi L, Stella G, Mantella A, Bartolozzi D, Tappe D, Günther S, et al. (February 2015). "Zika virus infections imported to Italy: clinical, immunological and virological findings, and public health implications". Journal of Clinical Virology. 63: 32–35. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2014.12.005. PMID 25600600.

- ^ Kraemer MU, Sinka ME, Duda KA, Mylne AQ, Shearer FM, Barker CM, et al. (June 2015). "The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus". eLife. 4: e08347. doi:10.7554/eLife.08347. PMC 4493616. PMID 26126267.

- ^ "Aedes aegypti". Health Topics: Vectors: Mosquitos. European Centre for Disease Protection and Control. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Craig S, Collins B (26 January 2016). "Mosquitoes capable of carrying Zika virus found in Washington, D.C." Notre Dame News. University of Notre Dame.

- ^ "Zika outbreak: What you need to know". BBC News. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "How to Avoid Mosquito Bites in Florida". 10 June 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Carlson CJ, Dougherty ER, Getz W (August 2016). "An Ecological Assessment of the Pandemic Threat of Zika Virus". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (8): e0004968. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004968. PMC 5001720. PMID 27564232.

- ^ Oussayef NL, Pillai SK, Honein MA, Ben Beard C, Bell B, Boyle CA, et al. (January 2017). "Zika Virus -10 Public Health Achievements in 2016 and Future Priorities". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (52): 1482–1488. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6552e1. PMID 28056005.

- ^ "WHO chief going to the Olympics, says Zika risk low". Reuters. 29 July 2016.

According to Margaret Chan, the director of the WHO, 'Of course, we also have learnt from the latest evidence it's not just infected men who can pass the disease to their sex partners. There was a case of a lady passing the disease to a man, so it can go both directions.'

- ^ Le Tortorec A, Matusali G, Mahé D, Aubry F, Mazaud-Guittot S, Houzet L, Dejucq-Rainsford N (July 2020). "From Ancient to Emerging Infections: The Odyssey of Viruses in the Male Genital Tract". Physiological Reviews. 100 (3): 1349–1414. doi:10.1152/physrev.00021.2019. PMID 32031468. S2CID 211045539.

- ^ Matusali G, Houzet L, Satie AP, Mahé D, Aubry F, Couderc T, et al. (October 2018). "Zika virus infects human testicular tissue and germ cells". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 128 (10): 4697–4710. doi:10.1172/JCI121735. PMC 6159993. PMID 30063220.

- ^ Joguet G, Mansuy JM, Matusali G, Hamdi S, Walschaerts M, Pavili L, et al. (November 2017). "Effect of acute Zika virus infection on sperm and virus clearance in body fluids: a prospective observational study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 17 (11): 1200–1208. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30444-9. PMID 28838639.

- ^ Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, Havers F, Oduyebo T, Hills SL, et al. (October 2016). "Update: Interim Guidance for Preconception Counseling and Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus for Persons with Possible Zika Virus Exposure - United States, September 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (39): 1077–1081. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6539e1. PMID 27711033.

- ^ "CDC Zika: Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 April 2016. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Paploski IA, Prates AP, Cardoso CW, Kikuti M, Silva MM, Waller LA, et al. (August 2016). "Time Lags between Exanthematous Illness Attributed to Zika Virus, Guillain-Barré Syndrome, and Microcephaly, Salvador, Brazil". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (8): 1438–1444. doi:10.3201/eid2208.160496. PMC 4982160. PMID 27144515.

- ^ Aguilar Ticona JP, Nery N, Ladines-Lim JB, Gambrah C, Sacramento G, de Paula Freitas B, et al. (February 2021). Ramos AM (ed.). "Developmental outcomes in children exposed to Zika virus in utero from a Brazilian urban slum cohort study". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 15 (2): e0009162. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009162. PMC 7891708. PMID 33544730.

- ^ Rubin EJ, Greene MF, Baden LR (March 2016). "Zika Virus and Microcephaly". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (10): 984–985. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1601862. PMID 26862812. S2CID 205079825.

- ^ Stanelle-Bertram S, Walendy-Gnirß K, Speiseder T, Thiele S, Asante IA, Dreier C, et al. (October 2018). "Male offspring born to mildly ZIKV-infected mice are at risk of developing neurocognitive disorders in adulthood". Nature Microbiology. 3 (10): 1161–1174. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0236-1. hdl:10138/306618. PMID 30202017. S2CID 52181681.

- ^ Kikuti M, Cardoso CW, Prates AP, Paploski IA, Kitron U, Reis MG, et al. (November 2018). "Congenital brain abnormalities during a Zika virus epidemic in Salvador, Brazil, April 2015 to July 2016". Euro Surveillance. 23 (45): 1–10. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.45.1700757. PMC 6234531. PMID 30424827.

- ^ Rathore AP, Saron WA, Lim T, Jahan N, St John AL (February 2019). "Maternal immunity and antibodies to dengue virus promote infection and Zika virus-induced microcephaly in fetuses". Science Advances. 5 (2): eaav3208. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.3208R. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav3208. PMC 6392794. PMID 30820456.

- ^ Brown JA, Singh G, Acklin JA, Lee S, Duehr JE, Chokola AN, et al. (March 2019). "Dengue Virus Immunity Increases Zika Virus-Induced Damage during Pregnancy". Immunity. 50 (3): 751–762.e5. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.005. PMC 6947917. PMID 30737148.

- ^ "Recommendations for Donor Screening, Deferral, and Product Management to Reduce the Risk of Transfusion-Transmission of Zika Virus" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. February 2016.

- ^ "Zika virus infection outbreak, Brazil and the Pacific region" (PDF). Rapid Risk Assessments. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 May 2015. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Musso D, Nhan T, Robin E, Roche C, Bierlaire D, Zisou K, et al. (April 2014). "Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014". Euro Surveillance. 19 (14): 20761. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.14.20761. PMID 24739982.

- ^ Chan JF, Choi GK, Yip CC, Cheng VC, Yuen KY (May 2016). "Zika fever and congenital Zika syndrome: An unexpected emerging arboviral disease". The Journal of Infection. 72 (5): 507–524. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2016.02.011. hdl:10722/231183. PMC 7112603. PMID 26940504.

- ^ Buckley A, Gould EA (August 1988). "Detection of virus-specific antigen in the nuclei or nucleoli of cells infected with Zika or Langat virus". The Journal of General Virology. 69 (8): 1913–1920. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-69-8-1913. PMID 2841406.

- ^ Chiu M (14 November 2019). "How maternal Zika virus infection results in newborn microcephaly". ScienMag. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Harsh S, Fu Y, Kenney E, Han Z, Eleftherianos I (April 2020). "Zika virus non-structural protein NS4A restricts eye growth in Drosophila through regulation of JAK/STAT signaling". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 13 (4): dmm040816. doi:10.1242/dmm.040816. PMC 7197722. PMID 32152180.

- ^ a b c d e "Zika virus". World Health Organization. January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Haby MM, Pinart M, Elias V, Reveiz L (June 2018). "Prevalence of asymptomatic Zika virus infection: a systematic review". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 96 (6): 402–413D. doi:10.2471/BLT.17.201541. PMC 5996208. PMID 29904223.

- ^ a b c d "Factsheet for health professionals". Health topics: Zika virus infection. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chen LH, Hamer DH (May 2016). "Zika Virus: Rapid Spread in the Western Hemisphere". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (9): 613–615. doi:10.7326/M16-0150. PMID 26832396.

- ^ Musso D, Nilles EJ, Cao-Lormeau VM (October 2014). "Rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (10): O595–O596. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12707. PMID 24909208.

- ^ Dhiman G, Abraham R, Griffin DE (July 2019). "Human Schwann cells are susceptible to infection with Zika and yellow fever viruses, but not dengue virus". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 9951. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.9951D. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46389-0. PMC 6616448. PMID 31289325.

- ^ "Zika diagnostic test granted market authorization by FDA". Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Oster AM, Russell K, Stryker JE, Friedman A, Kachur RE, Petersen EE, et al. (April 2016). "Update: Interim Guidance for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus--United States, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (12): 323–325. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6512e3. PMID 27032078.

- ^ "Brazil warns against pregnancy due to spreading virus". CNN. 24 December 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ "Treatment for Zika Virus". CDC. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Saxena SK, Elahi A, Gadugu S, Prasad AK (June 2016). "Zika virus outbreak: an overview of the experimental therapeutics and treatment". Virusdisease. 27 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1007/s13337-016-0307-y. PMC 4909003. PMID 27366760.

- ^ a b "WHO and experts prioritize vaccines, diagnostics and innovative vector control tools for Zika R&D". World Health Organization. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Cook J (27 January 2016). "Zika virus: US scientists say vaccine '10 years away'". BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Sagonowsky E (21 June 2016). "Inovio set for first Zika vaccine human trial". fiercepharma.com. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Phase 2 Zika vaccine trial begins in U.S., Central and South America". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 31 March 2017.

- ^ Fernandez E, Diamond MS (April 2017). "Vaccination strategies against Zika virus". Current Opinion in Virology. 23: 59–67. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.006. PMC 5576498. PMID 28432975.

- ^ "Geographic Distribution". Zika Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Gatherer D, Kohl A (February 2016). "Zika virus: a previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas". The Journal of General Virology. 97 (2): 269–273. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000381. PMID 26684466.

- ^ "Zika virus in the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Cohen J (8 February 2016). "Zika's long, strange trip into the limelight". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ Haddow AD, Schuh AJ, Yasuda CY, Kasper MR, Heang V, Huy R, et al. (2012). "Genetic characterization of Zika virus strains: geographic expansion of the Asian lineage". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (2): e1477. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477. PMC 3289602. PMID 22389730.

- ^ a b c Wikan N, Smith DR (July 2016). "Zika virus: history of a newly emerging arbovirus". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 16 (7): e119–e126. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(16)30010-x. PMID 27282424.

- ^ Dick GW (September 1952). "Zika virus. II. Pathogenicity and physical properties". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 46 (5): 521–534. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(52)90043-6. PMID 12995441.

- ^ Macnamara FN (March 1954). "Zika virus: a report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 48 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(54)90006-1. PMID 13157159.

- ^ Wikan N, Smith DR (January 2017). "First published report of Zika virus infection in people: Simpson, not MacNamara". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 17 (1): 15–17. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30525-4. PMID 27998553.

- ^ Bearcroft WG (September 1956). "Zika virus infection experimentally induced in a human volunteer". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 50 (5): 442–448. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(56)90091-8. PMID 13380987.

- ^ Simpson DI (July 1964). "Zika virus infection in man". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 58 (4): 335–338. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(64)90201-9. PMID 14175744.

- ^ Austin R (10 February 2016). "Experts Study Zika's Path From First Outbreak in Pacific". The New York Times. Hong Kong. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Henry M (24 May 2017). "Zika virus found to be circulating in Africa for decades". Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Angola reports first two cases of Zika virus". Reuters. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Blood samples show presence of Zika virus in Tanzania". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Altman LK (3 July 2007). "Little-Known Virus Challenges a Far-Flung Health System". The New York Times.

- ^ Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. (June 2009). "Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (24): 2536–2543. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. PMID 19516034.

- ^ Saiz JC, Vázquez-Calvo Á, Blázquez AB, Merino-Ramos T, Escribano-Romero E, Martín-Acebes MA (19 April 2016). "Zika Virus: the Latest Newcomer". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 496. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00496. PMC 4835484. PMID 27148186.

- ^ "WHO sees Zika outbreak spreading through the Americas". Reuters. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ "WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome". World Health Organization. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Roberts M (1 February 2016). "Zika-linked condition: WHO declares global emergency". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Pearson M (2 February 2016). "Zika virus sparks 'public health emergency'". CNN. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Boadle A (18 February 2016). Brown T, Orr B (eds.). "U.S., Brazil researchers join forces to battle Zika virus". Reuters. Brasilia. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Microcephaly in Brazil potentially linked to the Zika virus epidemic, ECDC assesses the risk". News and Media. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Kiernan P, Jelmayer R (3 February 2016). "Zika Fears Imperil Brazil's Tourism Push". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Belluz J (26 May 2016). "Rio Olympics 2016: why athletes and fans aren't likely to catch Zika". Vox. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "World Health Organization declares end of Zika emergency". The Irish Times. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Cohen J (16 August 2017). "Zika has all but disappeared in the Americas. Why?". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aao6984.

- ^ "2017 - India". World Health Organization. 26 May 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Bhardwaj S, Gokhale MD, Mourya DT (November 2017). "Zika virus: Current concerns in India". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 146 (5): 572–575. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1160_17 (inactive 1 August 2023). PMC 5861468. PMID 29512599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 2023년 8월 기준 DOI 비활성화 (링크) - ^ Rolph MS, Mahalingam S (May 2019). "Zika's passage to India". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 19 (5): 469–470. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30169-0. PMID 31034391. S2CID 140302216.

- ^ "Zika Virus Disease – India". World Health Organization. 14 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "65 Zika virus cases reported in Kerala as on August 2, 2021: Health minister Mansukh Mandaviya". The Economic Times. 6 August 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Singh R (24 October 2021). "Zika virus case detected in Kanpur, first in Uttar Pradesh". India Today. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "Bangladesh Confirms First Case of Zika Virus". Newsweek. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Ho, Zheng Jie Marc; et al. (Singapore Zika Study Group) (August 2017). "Outbreak of Zika virus infection in Singapore: an epidemiological, entomological, virological, and clinical analysis". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 813–821. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30249-9. PMID 28527892.

- ^ "Zika Virus in Singapore". CDC. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ HPS Travel Health Fit for Travel (4 January 2024). "Zika virus in Thailand". www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Epidemiologisches Bulletin (18 January 2024). "Vermehrte Zikavirus-Fälle bei Thailandreisenden" (PDF). Robert Koch-Institut.

![]() 이 기사는 질병 통제 예방 센터의 웹 사이트나 문서의 공용 도메인 자료를 통합합니다.

이 기사는 질병 통제 예방 센터의 웹 사이트나 문서의 공용 도메인 자료를 통합합니다.

외부 링크

- "Zika virus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 November 2014.

- "Zika virus". Fact sheet. World Health Organization.

- "Zika virus illustrations, 3D model, and animation". visual-science.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Zika virus (strain Mr 766)". Viral Zone.

- Schmaljohn AL, McClain D (1996). "54. Alphaviruses (Togaviridae) and Flaviviruses (Flaviviridae)". In Baron S (ed.). Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. PMID 21413253. NBK7633.

- "Animation on Zika". YouTube. Scientific Animations without Borders and the World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 December 2021.

- Schuchat A (15 October 2018). "Zika Virus 101". YouTube. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 20 December 2021.