유전공학

Genetic engineering| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 유전공학 |

|---|

|

| 유전자 조작 생물 |

| 역사와 규정 |

| 과정 |

| 적용들 |

| 논쟁 |

유전자 변형 또는 유전자 조작이라고도 불리는 유전공학은 기술을 이용하여 유기체의 유전자를 변형하고 조작하는 것이다.그것은 개량되거나 새로운 유기체를 생산하기 위해 종의 경계를 넘어 유전자의 전달을 포함하여 세포의 유전자 구성을 바꾸는 데 사용되는 일련의 기술이다.새로운 DNA는 유전자 재조합 DNA법을 사용하여 해당 유전물질을 분리 및 복제하거나 DNA를 인공적으로 합성함으로써 얻을 수 있다.구조물은 보통 이 DNA를 숙주 유기체에 삽입하기 위해 만들어지고 사용된다.최초의 재조합 DNA 분자는 1972년 폴 버그에 의해 원숭이 바이러스 SV40의 DNA와 람다 바이러스의 결합으로 만들어졌다.유전자를 삽입하는 것뿐만 아니라, 그 과정은 유전자를 제거하거나 "녹아웃"하는데 사용될 수 있다.새로운 DNA는 무작위로 삽입되거나 [1]게놈의 특정 부분을 대상으로 할 수 있다.

유전자 공학을 통해 생성된 유기체는 유전자 변형(GM)된 것으로 간주되며, 그 결과 생성된 유기체는 유전자 변형 유기체(GMO)이다.최초의 GMO는 1973년 허버트 보이어와 스탠리 코헨에 의해 생성된 박테리아였다.루돌프 재니쉬는 1974년 생쥐에 외래 DNA를 삽입하면서 최초의 유전자 조작 동물을 만들었다.유전자 공학에 초점을 맞춘 최초의 회사, Genentech는 1976년에 설립되어 인간 단백질 생산을 시작했다.1978년 유전자 조작 인간 인슐린이 생산됐고 1982년 인슐린을 생산하는 박테리아가 상용화됐다.유전자 조작 식품은 1994년부터 플라브르 사브르 토마토의 출시와 함께 판매되고 있다.Flavr Savr는 유통기한이 길도록 설계되었지만, 현재 대부분의 GM 작물은 곤충과 제초제에 대한 내성을 높이기 위해 수정되었습니다.애완동물로 설계된 최초의 GMO인 GloFish는 2003년 12월 미국에서 판매되었다.2016년에는 성장호르몬으로 변형된 연어가 판매되었다.

유전공학은 연구, 의학, 산업생명공학, 농업 등 다양한 분야에서 응용되고 있다.연구에서 GMO는 기능 상실, 기능 향상, 추적 및 발현 실험을 통해 유전자 기능과 발현을 연구하는 데 사용된다.특정 조건에 책임이 있는 유전자를 제거함으로써 인간 질병의 동물 모델 유기체를 만드는 것이 가능하다.유전자 공학은 호르몬, 백신, 그리고 다른 약물을 생산할 뿐만 아니라 유전자 치료를 통해 유전병을 치료할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다.약을 생산하기 위해 사용되는 것과 같은 기술은 세탁 세제, 치즈, 그리고 다른 제품들을 위한 효소를 생산하는 것과 같은 산업적인 응용을 할 수 있다.

상업화된 유전자 변형 작물의 증가는 많은 다른 나라의 농부들에게 경제적 이익을 제공했지만, 또한 이 기술을 둘러싼 대부분의 논란의 원인이 되었다.이것은 초기 사용부터 존재해 왔습니다.첫 번째 현장 실험은 반GM 운동가들에 의해 파괴되었습니다.비록 현재 유전자 조작 작물에서 유래한 식품이 기존의 식품보다 인간의 건강에 더 큰 위험을 끼치지 않는다는 과학적 합의가 있지만, 유전자 조작 식품 안전은 비평가들에게 주요한 관심사이다.유전자 흐름, 비표적 유기체에 대한 영향, 식량 공급 통제 및 지적 재산권 문제도 잠재적인 문제로 제기되었다.이러한 우려는 1975년에 시작된 규제 프레임워크의 개발로 이어졌다.그것은 2000년에 채택된 바이오 안전에 관한 국제 조약인 카르타헤나 의정서를 이끌어냈다.개별 국가는 GMO에 관한 자체 규제 시스템을 개발했으며, 미국과 유럽 간에 가장 큰 차이가 발생하고 있다.

개요

유전공학은 DNA를 제거하거나 도입하거나 기존 유전물질을 그대로 변형시켜 유기체의 유전자 구조를 바꾸는 과정이다.여러 번 교배한 후 원하는 표현형을 가진 유기체를 선택하는 전통적인 동식물 사육과 달리, 유전공학은 한 유기체에서 직접 유전자를 가져와 다른 유기체로 전달한다.이것은 훨씬 더 빠르고, 어떤 유기체의 유전자를 삽입하는데 사용될 수 있고 다른 바람직하지 않은 유전자가 첨가되는 것을 [4]막습니다.

유전자 공학은 결함이 있는 유전자를 기능하는 [5]유전자로 대체함으로써 인간의 심각한 유전 장애를 잠재적으로 고칠 수 있다.그것은 특정 유전자의 기능을 [6]연구할 수 있게 해주는 연구에서 중요한 도구이다.약품, 백신, 그리고 다른 제품들은 그것들을 [7]생산하도록 조작된 유기체로부터 수확되었다.농작물은 수확량, 영양가, [8]환경 스트레스에 대한 내성을 증가시킴으로써 식량안보를 돕는 것이 개발되어 왔다.

DNA는 숙주 유기체에 직접 도입되거나 [9]숙주와 융합되거나 교배되는 세포에 도입될 수 있다.이는 유전성 유전물질의 새로운 조합을 형성하기 위해 재조합 핵산 기술에 의존하며, 벡터 시스템을 통해 간접적으로 또는 마이크로 주입, 매크로 주입 또는 마이크로 [10]캡슐화를 통해 해당 물질의 통합이 이루어진다.

유전자 공학은 일반적으로 유전자 변형 핵산이나 유전자 변형 유기체를 [9]사용하지 않는 전통적인 사육, 체외 수정, 다배체 유도, 돌연변이 유발 및 세포 융합 기술을 포함하지 않는다.그러나 유전자 공학의 일부 넓은 정의에는 선택적 [10]교배가 포함된다.복제와 줄기세포 연구는 유전공학으로 [11]간주되지 않지만 밀접하게 관련되어 있으며 유전공학이 [12]그 안에서 사용될 수 있다.합성 생물학은 유기체에 [13]인공 합성 물질을 도입함으로써 유전 공학을 한 단계 발전시키는 새로운 학문이다.

유전자 공학을 통해 변화된 식물, 동물, 미생물을 유전자 변형 생물 [14]또는 GMO라고 한다.다른 종의 유전 물질이 숙주에 첨가되면 그 결과 생기는 유기체를 유전자 변형 생물이라고 한다.같은 종의 유전 물질이나 숙주와 함께 자연적으로 번식할 수 있는 종을 사용한다면 그 결과 생기는 유기체는 시스제닉이라고 [15]불린다.표적 유기체로부터 유전 물질을 제거하기 위해 유전자 공학을 사용할 경우, 그 결과 발생하는 유기체를 녹아웃 [16]유기체라고 한다.유럽에서는 유전자 변형은 유전자 공학과 동의어이며, 미국이나 캐나다에서는 보다 전통적인 번식 [17][18][19]방법을 언급하기 위해 유전자 변형도 사용될 수 있다.

역사

인간은 수천 년 동안 자연 선택과 달리 선택적 교배 또는 인위적인[20]: 1 [21]: 1 선택을 통해 종의 게놈을 변화시켜 왔다.최근 돌연변이 교배는 선택적 교배를 위해 높은 빈도의 무작위 돌연변이를 생성하기 위해 화학 물질이나 방사선에 노출되는 것을 사용하고 있다.유전자 공학은 번식이나 돌연변이를 하지 않고 인간이 직접 DNA를 조작하는 기술로서 1970년대부터 존재해 왔다.1년 전에 유전에서 DNA의 역할 앨프리드 허시, 마사 Chase,[23]에 의해 2년 전 제임스 왓슨과 프랜시스 크릭은 DNA분자는double-helix 구조를 갖고 있는 것을 공식화 이 용어"유전 공학"먼저 윌리엄슨에 의해 그의 과학 소설 드래곤의 섬, 1951[22]–에 게재된 – 말이 만들어졌다 비록톤그는 gene직접 유전자 조작의 랄 개념은 스탠리 G에서 기초적인 형태로 탐구되었다. 와인바움의 1936년 공상 과학 소설 프로테우스 섬.[24][25]

1972년 폴 버그는 원숭이 바이러스 SV40의 DNA와 람다 [26]바이러스의 DNA를 결합해 최초의 재조합 DNA 분자를 만들었다.1973년 허버트 보이어와 스탠리 코헨은 대장균의 [27][28]플라스미드에 항생제 내성 유전자를 삽입함으로써 최초의 트랜스제닉 유기체를 만들었다.1년 후, 루돌프 재니쉬는 외래 DNA를 배아에 도입함으로써 트랜스제닉 쥐를 만들었고, 이는 세계 최초의 트랜스제닉[29] 동물로 만들었다. 이러한 업적은 과학계에서 유전 공학으로 인한 잠재적 위험에 대한 우려를 낳았으며, 1975년 아실로마르 회의에서 처음으로 심도 있게 논의되었다.이 회의에서 제안된 주요 사항 중 하나는 기술이 [30][31]안전하다고 간주될 때까지 재조합 DNA 연구에 대한 정부의 감독을 확립해야 한다는 것이었다.

1976년 허버트 보이어와 로버트 스완슨에 의해 최초의 유전공학 회사인 제넨텍이 설립되었고, 1년 후 이 회사는 대장균에서 인간 단백질(소마토스타틴)을 생산했다.Genentech는 [32]1978년 유전자 조작 인간 인슐린의 생산을 발표했다.1980년, 다이아몬드 대 차크라바티 사건에서 미국 대법원은 유전자 변형 생명체가 [33]특허를 받을 수 있다고 판결했다.박테리아에 의해 생성된 인슐린은 1982년 [34]미국 식품의약국(FDA)에 의해 방출이 승인되었다.

1983년 생명공학 회사인 Advanced Genetic Sciences(AGS)는 서리로부터 농작물을 보호하기 위해 얼음-마이너스 변종인 Pseudomonas syrigerae에 대한 현장 시험을 미국 정부의 허가를 신청했지만, 환경 단체와 시위자들은 법적 문제로 [35]4년 동안 현장 시험을 연기했다.1987년, 캘리포니아의 딸기 밭과 감자 밭에 얼음-마이너스 균주가 [37]뿌려졌을 때, 환경에 방출된[36] 최초의 유전자 변형 유기체가 되었다.두 시험장은 시험 전날 밤 "세계 최초의 시험장이 세계 최초의 현장 추적자를 끌어들였다"[36]는 활동가들의 공격을 받았다.

1986년 프랑스와 미국에서 유전자 조작 식물에 대한 첫 번째 현장 실험이 이루어졌으며 담배 식물은 제초제에 [38]내성을 갖도록 설계되었다.중국은 [39]1992년에 바이러스 내성 담배를 도입하면서 트랜스제닉 식물을 상업화한 최초의 국가였다.1994년 Calgene은 최초의 유전자 변형 식품인 Flavr Savr를 상업적으로 출시하는 승인을 얻었다. Flavr Savr는 유통기한이 [40]더 길도록 설계되었다.1994년 유럽연합은 제초제 브로모옥실닐에 내성을 갖도록 설계된 담배를 [41]승인하여 유럽에서 최초로 유전자 공학을 통해 상업화된 작물이 되었다.1995년, BT 감자는 FDA의 승인을 받은 후 환경보호청으로부터 안전 승인을 받아 [42]미국에서 처음으로 농약 생산 작물이 되었다.2009년에는 25개국에서 11개의 유전자 변형 작물이 상업적으로 재배되었으며, 그 중 재배 지역별로 가장 큰 것은 미국, 브라질, 아르헨티나, 인도, 캐나다, 중국, 파라과이, 남아프리카 [43]공화국이었다.

2010년, J. 크레이그 벤터 연구소의 과학자들은 최초의 합성 게놈을 만들어 빈 박테리아 세포에 삽입했다.그 결과 마이코플라스마 라보토리엄이라는 이름의 박테리아는 복제하여 [44][45]단백질을 생산할 수 있었다.4년 후, 이것은 한 걸음 더 나아가 독특한 염기쌍을 포함하는 플라스미드를 복제하는 박테리아가 개발되면서 확장된 유전자 [46][47]알파벳을 사용하도록 설계된 최초의 유기체를 만들었다.2012년, 제니퍼 도우드나와 엠마뉴엘 샤펜티어는 거의 [50]모든 유기체의 게놈을 쉽고 구체적으로 바꿀 수 있는 기술인 CRISPR/[48][49]Cas9 시스템을 개발하기 위해 협력했다.

과정

GMO의 작성은 다단계 프로세스입니다.유전공학자는 먼저 어떤 유전자를 유기체에 삽입할지를 선택해야 한다.이것은 결과 유기체에 대한 목적이 무엇인지에 의해 추진되며 이전의 연구에 기초하고 있다.유전자 검사는 잠재적 유전자를 판단하기 위해 수행될 수 있고, 그리고 나서 더 많은 테스트를 통해 최적의 후보자를 확인할 수 있다.마이크로어레이, 전사체학, 게놈 염기서열 분석의 발달로 적합한 [51]유전자를 찾는 것이 훨씬 쉬워졌다.운도 한몫한다; Roundup Ready 유전자는 과학자들이 제초제의 [52]존재 하에서 번성하는 박테리아를 발견한 후에 발견되었다.

유전자 분리 및 복제

다음 단계는 후보 유전자를 분리하는 것이다.유전자를 포함한 세포가 열리고 DNA가 [53]정제된다.이 유전자는 제한 효소를 사용하여 DNA를 조각으로[54] 자르거나 유전자 부분을 [55]증폭시키기 위해 중합효소 연쇄 반응(PCR)으로 분리된다.그런 다음 겔 전기영동을 통해 이러한 세그먼트를 추출할 수 있습니다.만약 선택된 유전자나 기증자의 게놈이 잘 연구되었다면, 이미 유전자 라이브러리에서 접근할 수 있을 것이다.DNA 배열이 알려져 있지만 사용 가능한 유전자의 복사본이 없는 경우, 그것은 [56]인공적으로 합성될 수도 있다.일단 분리되면 그 유전자는 플라스미드에 결합되어 박테리아에 삽입된다.플라스미드는 박테리아가 분열할 때 복제되어 유전자의 무한한 복사를 [57]보장한다.RK2 플라스미드는 다양한 단세포 생물에서 복제할 수 있는 능력이 뛰어나 유전자 공학 도구로서 [58]적합하다.

유전자가 대상 유기체에 삽입되기 전에 다른 유전 요소와 결합되어야 합니다.여기에는 전사를 시작하고 종료하는 프로모터 및 터미네이터 영역이 포함됩니다.대부분의 경우 항생제 내성을 부여하는 선택 가능한 마커 유전자가 추가되어 연구자들은 어떤 세포가 성공적으로 변형되었는지 쉽게 판단할 수 있다.그 유전자는 또한 더 나은 발현이나 효과를 위해 이 단계에서 수정될 수 있다.이러한 조작은 제한 소화, 결합 및 분자 [59]복제와 같은 재조합 DNA 기술을 사용하여 수행됩니다.

숙주 게놈에 DNA 삽입

숙주 게놈에 유전 물질을 삽입하는 데 사용되는 많은 기술이 있다.어떤 박테리아는 자연적으로 외래 DNA를 흡수할 수 있다.이 능력은 스트레스를 통해 다른 박테리아에서 유도될 수 있으며, 이것은 DNA에 대한 세포막의 투과성을 증가시킨다; 상승된 DNA는 게놈과 통합되거나 염색체 외 DNA로 존재할 수 있다. DNA는 일반적으로 세포 핵을 통해 주입될 수 있는 미세 주입을 사용하여 동물 세포에 삽입된다. 핵으로 직접 들어가거나 바이러스 [60]벡터의 사용을 통해 포락선을 형성할 수 있습니다.

식물 게놈은 물리적 방법 또는 T-DNA 이진 벡터에 호스트된 배열을 전달하기 위해 아그로박테륨을 사용하여 엔지니어링될 수 있습니다.식물에서는 유전자 물질을 식물 세포에 자연스럽게 삽입할 [62]수 [61]있는 아그로박테륨 T-DNA 서열을 이용하여 종종 아그로박테륨 매개 변형을 사용하여 DNA를 삽입한다.다른 방법으로는 금이나 텅스텐의 입자가 DNA로 코팅된 후 어린 식물 [63]세포로 발사되는 생물학, 세포막을 플라스미드 DNA에 투과시키기 위해 전기 충격을 사용하는 전기학 등이 있다.

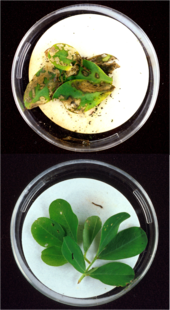

오직 하나의 세포만이 유전 물질로 변형되기 때문에, 유기체는 그 단일 세포에서 재생되어야 한다.식물에서 이것은 조직배양을 [64][65]통해 달성된다.동물에서는 삽입된 DNA가 배아줄기세포에 [66]존재하는지 확인하는 것이 필요하다.박테리아는 하나의 세포로 구성되어 복제적으로 번식하기 때문에 재생이 필요하지 않습니다.선택 가능한 마커는 변환된 세포와 변환되지 않은 세포를 쉽게 구별하기 위해 사용됩니다.이러한 마커들은 성숙한 트랜스제닉 [67]식물에서 선택 가능한 마커를 제거할 수 있는 많은 전략이 개발되었지만, 보통 트랜스제닉 유기체에 존재한다.

PCR, Southern Hybridation 및 DNA Sequencing을 사용하여 유기체가 새로운 [68]유전자를 가지고 있는지 확인하기 위한 추가 시험을 실시한다.이 검사들은 또한 삽입된 유전자의 염색체 위치와 복사 번호를 확인할 수 있다.유전자의 존재는 유전자가 표적 조직에서 적절한 수준으로 발현되는 것을 보장하지 않기 때문에 유전자 생성물(RNA와 단백질)을 찾고 측정하는 방법도 사용된다.여기에는 북부 교배, 정량적 RT-PCR, 웨스턴 블롯, 면역 형광, ELISA 및 표현형 [69]분석이 포함된다.

이 새로운 유전 물질은 숙주 게놈 내에 무작위로 삽입되거나 특정 위치를 대상으로 할 수 있다.유전자 타겟팅 기술은 특정 내생 유전자에 바람직한 변화를 주기 위해 상동 재조합을 사용한다.이는 식물과 동물에서 비교적 낮은 빈도로 발생하는 경향이 있으며 일반적으로 선택 가능한 마커를 사용해야 한다.유전자 표적의 빈도는 게놈 편집을 통해 크게 향상될 수 있다.게놈 편집은 유전체의 원하는 위치에 특정한 이중가닥 절단을 만드는 인공적으로 조작된 핵산 분해 효소를 사용하고, 세포의 내인성 메커니즘을 사용하여 상동 재조합과 비상동 종말 결합의 자연적 과정에 의해 유발된 절단을 복구합니다.공학적 핵산가수분해효소에는 메가핵산가수분해효소,[70][71] 아연 핑거 핵산가수분해효소,[72][73] 전사활성화제 유사 이펙터 핵산가수분해효소(TALENs)[74][75] 및 Cas9-가이드의 네 가지 종류가 있다.RNA 시스템(CRISPR에서 [76][77]채택됨).TALEN과 CRISPR은 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 두 가지이며 각각 고유한 [78]장점이 있습니다.TALEN은 타겟의 특수성이 높은 반면 CRISPR은 설계하기 쉽고 [78]효율적입니다.유전자 표적을 강화하는 것 외에,[79][80] 유전자 녹아웃을 생성하는 내생 유전자에 돌연변이를 도입하기 위해 조작된 핵산가수분해효소가 사용될 수 있다.

적용들

유전자 공학은 의학, 연구, 산업 및 농업 분야에서 응용되고 있으며 다양한 식물, 동물 및 미생물에 사용될 수 있습니다.유전자 변형된 최초의 유기체인 박테리아는 식품과 다른 [81][82]기질을 처리하는 약품이나 효소를 코드하는 새로운 유전자를 포함하는 플라스미드 DNA를 삽입할 수 있다.식물은 곤충 보호, 제초제 내성, 바이러스 내성, 영양 강화, 환경 압력에 대한 내성 및 식용 백신 [83]생산을 위해 수정되었습니다.대부분의 상용화된 유전자변형농산물은 내충성 또는 내초제 [84]작물이다.유전자 조작 동물은 연구, 모델 동물, 농산물이나 의약품 생산에 사용되어 왔다.유전자 조작 동물에는 유전자가 녹아웃된 동물, 질병에 걸리기 쉬운 동물, 추가적인 성장을 위한 호르몬, 그리고 [85]우유 속 단백질을 발현하는 능력이 포함된다.

약

유전자 공학은 약물의 제조, 인간의 상태를 모방한 모형 동물의 창조, 유전자 치료 등 의학에 많은 응용 분야를 가지고 있다.유전공학의 초기 사용 중 하나는 [32]박테리아에서 인간 인슐린을 대량 생산하는 것이었다.이 애플리케이션은 현재 인간 성장 호르몬, 모낭 자극 호르몬(불임 치료용), 인간 알부민, 모노클로널 항체, 항혈우병 인자, 백신 및 기타 많은 [86][87]약물에 적용되고 있다.생쥐 잡종(mouse hybridomas), 세포들이 함께 융합되어 모노클로널 항체를 만드는 유전 공학을 통해 인간 모노클로널 [88]항체를 만드는 데 적용되었습니다.면역력은 여전히 줄 수 있지만 감염 [89]배열은 부족한 유전자 조작 바이러스들이 개발되고 있다.

유전자 공학은 또한 인간 질병의 동물 모델을 만드는데 사용된다.유전자 조작 쥐는 가장 흔한 유전자 조작 동물 [90]모델이다.그것들은 암, 비만, 심장병, 당뇨병, 관절염, 약물 남용, 불안, 노화,[91] 파킨슨병을 연구하고 모델화하는데 사용되어 왔다.이러한 마우스 모델에 대해 잠재적인 치료법을 테스트할 수 있습니다.

유전자 치료는 일반적으로 결함이 있는 유전자를 효과적인 유전자로 대체함으로써 인간의 유전공학이다.체세포 유전자 치료를 이용한 임상 연구는 X-연계 SCID,[92] 만성 림프구성 백혈병(CLL),[93][94] 파킨슨병 [95]등 여러 질병과 함께 진행돼 왔다.2012년, 지방유전자 티파보벡은 임상용으로 [96][97]승인된 최초의 유전자 치료제가 되었다.2015년에 바이러스는 희귀한 피부병인 표피융해성 불소증을 앓고 있는 소년의 피부세포에 건강한 유전자를 삽입하여 성장시키고, 그 [98]병에 걸린 소년의 몸의 80%에 건강한 피부를 이식하는 데 사용되었다.

생식 유전자 치료는 어떠한 변화도 유전할 수 있는 결과를 가져올 것이고, 이것은 과학계의 [99][100]우려를 불러 일으켰다.2015년, CRISPR은 생존 불가능한 인간 [101][102]배아의 DNA를 편집하는 데 사용되었고, 주요 세계 학회의 과학자들은 유전적인 인간 게놈 [103]편집에 대한 모라토리엄을 요구하게 되었다.또한 이 기술이 치료뿐만 아니라 사람의 외모, 적응력, 지능, 성격 또는 [104]행동의 향상, 수정 또는 변경에 사용될 수 있다는 우려도 있다.치료와 강화의 차이 또한 [105]규명하기 어려울 수 있다.2018년 11월, He Jiankui는 인간 배아의 게놈을 편집하여 HIV가 세포에 들어가는 수용체를 코드하는 CCR5 유전자를 비활성화하려고 시도했다고 발표했다.그 작품은 비윤리적이고 위험하며 [106]시기상조라는 비난을 많이 받았다.현재 40개국에서 생식기 수정이 금지되어 있다.이런 종류의 연구를 하는 과학자들은 종종 배아가 아기로 자라도록 허락하지 않고 며칠 동안 배아가 자라도록 할 것이다.[107]

연구진은 돼지의 장기 [108]이식을 성공시키기 위해 돼지의 게놈을 인간 장기의 성장을 유도하기 위해 수정하고 있다.과학자들은 모기들이 말라리아에 면역이 되도록 모기의 게놈을 바꾸는 "유전자 운동"을 만들고 있으며,[109] 이 질병을 없애기 위해 유전자 변형된 모기들을 모기 개체군 전체에 확산시킬 방법을 찾고 있다.

조사.

유전자 공학은 유전자 기능을 [110]분석하기 위한 가장 중요한 도구 중 하나인 트랜스제닉 유기체의 창조와 함께 자연 과학자들에게 중요한 도구이다.광범위한 유기체의 유전자와 다른 유전 정보는 저장과 수정을 위해 박테리아에 삽입될 수 있으며, 그 과정에서 유전자 변형 박테리아를 만들 수 있다.박테리아는 값싸고, 성장하기 쉽고, 복제되고, 증식이 빠르고, 비교적 변형이 쉬우며, 거의 무기한 -80°C에서 저장될 수 있습니다.일단 유전자가 분리되면 연구를 위한 무제한 공급을 제공하는 박테리아 안에 [111]저장될 수 있다.

유기체는 특정 유전자의 기능을 발견하도록 유전적으로 조작된다.이것은 유전자가 발현되는 유기체의 표현형에 대한 영향일 수도 있고 유전자가 어떤 다른 유전자와 상호작용을 하는지일 수도 있다.이러한 실험에는 일반적으로 기능 상실, 기능 이득, 추적 및 표현이 포함됩니다.

- 유기체가 하나 이상의 유전자의 활동이 부족하도록 설계된 유전자 녹아웃 실험과 같은 기능 실험의 손실.단순한 녹아웃에서 원하는 유전자의 복사가 기능하지 않게 변형되었다.배아줄기세포는 이미 존재하는 기능적 복제를 대체하는 변경된 유전자를 통합한다.이 줄기세포들은 배반포에 주입되어 대리모에게 이식된다.이를 통해 실험자는 이 돌연변이에 의해 야기된 결함을 분석하여 특정 유전자의 역할을 결정할 수 있다.특히 자주 발생 생물학에 사용된다.[112]언제 이런 관심의 영역, 즉 전체 유전자에서 심지어는 모든 위치에 모든 위치에서 유전자의 점 돌연변이를 가진 도서관이 송금되면 이"돌연변이 생성 주사"라고 불린다.가장 간단한 메서드를 호출하고, 사용될 최초"주사 알라닌", 차례로 각 포지션이 비반응성 아미노산 알라닌에 변형된다.[113]

- 기능 실험의 이득, 녹아웃의 논리적 대응물.이것들은 때때로 원하는 유전자의 기능을 보다 정교하게 확립하기 위해 녹아웃 실험과 함께 수행된다.그 과정은 녹아웃 공학에서의 것과 거의 유사하지만, 그 구조가 보통 유전자의 추가적인 복제를 제공하거나 단백질의 합성을 더 자주 유도함으로써 유전자의 기능을 증가시키도록 설계되었다는 점을 제외한다.기능의 이득은 단백질이 기능에 충분한지 아닌지를 판단하기 위해 사용되지만, 특히 유전적 또는 기능적 [112]중복을 다룰 때 단백질이 항상 필요한 것은 아니다.

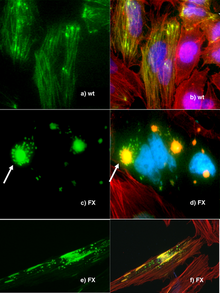

- 추적 실험 - 원하는 단백질의 국소화 및 상호작용에 대한 정보를 얻으려고 합니다.이것을 하는 한 가지 방법은 야생형 유전자를 '융합' 유전자로 대체하는 것이다. 이 유전자는 유전자 변형 산물을 쉽게 시각화할 수 있는 녹색 형광 단백질(GFP)과 같은 보고 요소와 함께 배열된 것이다.이것은 유용한 기술이지만, 조작은 유전자의 기능을 파괴할 수 있고, 이차적인 효과를 만들어 내고, 실험 결과에 의문을 제기할 수 있다.모노클로널 [112]항체에 결합 모티브 역할을 하는 작은 배열을 추가하는 것과 같이, 단백질의 기능을 완화시키지 않고 단백질 제품을 추적할 수 있는 보다 정교한 기술이 현재 개발되고 있다.

- 발현 연구는 특정 단백질이 어디서 언제 생산되는지를 발견하는 것을 목표로 한다.이러한 실험에서, 유전자의 프로모터로 알려진 단백질을 코드하는 DNA 이전의 DNA 배열은 GFP와 같은 리포터 유전자나 염료 생산을 촉진하는 효소로 대체된 단백질 코드 영역을 가진 유기체에 다시 도입된다.따라서 특정 단백질이 생성되는 시간과 장소를 관찰할 수 있다.발현 연구는 프로모터를 변화시켜 유전자의 적절한 발현에 중요하고 실제로 전사인자 단백질에 의해 결합되는 것을 발견함으로써 한 걸음 더 나아갈 수 있다. 이 과정은 프로모터 [114]때리기라고 알려져 있다.

산업의

유기체는 원하는 단백질을 과도하게 발현시키기 위해 효소와 같은 유용한 단백질을 코드하는 유전자로 세포를 변형시킬 수 있다.다음으로 산업발효를 이용하여 바이오리액터 설비에서 변형된 유기체를 성장시킨 후 단백질을 [115]정제함으로써 단백질의 대량으로 제조할 수 있다.일부 유전자는 박테리아에서 잘 작동하지 않기 때문에 효모, 곤충 세포 또는 포유류의 세포도 [116]사용될 수 있다.이 기술들은 인슐린, 인간 성장 호르몬, 백신과 같은 의약품, 트립토판 같은 보충제, 음식 생산의 보조제,[117] 그리고 연료를 생산하는데 사용된다.유전자 조작 박테리아가 있는 다른 응용 프로그램에는 바이오 [118]연료의 제조, 기름 유출, 탄소 및 기타 유독성[119] 폐기물의 정화 및 식수 [120]내 비소 검출과 같은 자연 순환 이외의 작업을 수행하도록 하는 것이 포함될 수 있습니다.특정 유전자 변형 미생물은 또한 그들의 환경에서 중금속을 추출하고 그것들을 더 쉽게 회복할 [121]수 있는 화합물에 통합시키는 능력 때문에 바이오미닝과 생물 개선에도 사용될 수 있다.

재료 과학에서는, 유전자 변형 바이러스가 보다 환경 친화적인 리튬 이온 배터리를 [122][123]조립하기 위한 발판으로 연구소에서 사용되어 왔다.박테리아는 또한 특정 환경 [124]조건 하에서 형광 단백질을 발현함으로써 센서 역할을 하도록 설계되었다.

농업

유전자 공학에서 가장 잘 알려져 있고 논란이 많은 응용 분야 중 하나는 유전자 변형 식품을 생산하기 위해 유전자 변형 농작물이나 유전자 변형 가축을 만들고 사용하는 것이다.작물은 생산을 증가시키고, 비생물적 스트레스에 대한 내성을 증가시키고, 식품의 구성을 바꾸거나, 새로운 [126]제품을 생산하기 위해 개발되어 왔다.

대규모로 상업적으로 출시된 최초의 작물은 병충해로부터 보호하거나 제초제에 대한 내성을 제공했습니다.곰팡이 및 바이러스 내성 작물도 개발 중이거나 [127][128]개발 중입니다.이것은 농작물의 곤충과 잡초 관리를 용이하게 하고 간접적으로 농작물 [129][130]수확량을 증가시킬 수 있다.생육을 가속화하거나 (소금, 추위 또는 가뭄 내성을 개선함으로써) 식물을 더 튼튼하게 만들어 수확량을 직접적으로 향상시키는 유전자 변형 작물도 [131]개발 중이다.2016년 연어는 성장호르몬에 의해 유전적으로 변형되어 정상적인 성인의 크기에 훨씬 [132]더 빨리 도달했다.

GMO는 영양가치를 높이거나 산업적으로 유용한 품질 또는 [131]양을 제공함으로써 생산물의 품질을 수정하는 방식으로 개발되었습니다.암플로라 감자는 산업적으로 더 유용한 녹말 혼합물을 생산한다.콩과 유채꽃은 더 많은 건강한 [133][134]기름을 생산하기 위해 유전적으로 변형되었다.최초의 상품화된 GM 식품은 숙성이 늦어져 유통기한이 [135]늘어난 토마토였다.

식물과 동물은 보통 그들이 만들지 않는 재료를 생산하도록 설계되었다.파밍은 농작물과 동물을 생물반응제로 사용하여 백신, 약물 중간체 또는 약물 자체를 생산한다. 유용한 제품은 수확으로부터 정제되어 표준 의약품 생산 과정에 [136]사용된다.소와 염소는 우유에서 약물과 다른 단백질을 발현하도록 조작되었고, 2009년 FDA는 염소 [137][138]젖에서 생산된 약을 승인했다.

기타 응용 프로그램

유전자 공학은 보존과 자연 영역 관리에 잠재적으로 응용될 수 있습니다.바이러스 벡터를 통한 유전자 이동은 [139]질병으로부터 멸종위기에 처한 동물군을 예방접종할 뿐만 아니라 침입종을 통제하는 수단으로 제안되어 왔다.트랜스제닉 나무는 야생 개체군의 [140]병원균에 대한 저항력을 부여하는 방법으로 제안되어 왔다.기후 변화와 다른 섭동의 결과로 유기체의 부적응의 위험이 증가하는 가운데, 유전자 조정을 통한 원활한 적응은 멸종 위험을 [141]줄이는 하나의 해결책이 될 수 있다.보존에 있어서의 유전공학의 응용은 지금까지 대부분 이론적이고 아직 실용화되지 않았다.

유전자 공학 또한 미생물 [142]예술을 만드는데 사용되고 있다.일부 박테리아는 흑백 [143]사진을 만들기 위해 유전적으로 조작되었다.라벤더 컬러의 카네이션,[144] 푸른 장미,[145] 빛나는[146][147] 물고기 등의 참신성 아이템도 유전자 공학을 통해 생산되고 있다.

규정

유전자 공학의 규제는 정부가 GMO의 개발과 출시와 관련된 위험을 평가하고 관리하기 위해 취하는 접근법에 관한 것이다.규제 프레임워크의 개발은 1975년 [148]캘리포니아의 아실로마에서 시작되었다.Asilomar 회의는 재조합 [30]기술의 사용에 관한 일련의 자발적인 가이드라인을 권고했다.기술이 발전함에 따라,[149] 미국은 과학기술청에 위원회를 설립하였고, 이 위원회는 USDA, FDA [150]및 EPA에 GM 식품의 규제 승인을 위임하였다.2000년 [152]1월 29일 GMO의 [151]이전, 취급, 사용을 규제하는 국제조약인 바이오 안전성에 관한 카르타헤나 의정서가 채택됐다.이 의정서의 회원국은 157개국이며, 많은 국가들이 이 의정서를 자국 [153]규제의 기준점으로 사용하고 있다.

유전자 변형 식품의 법적, 규제적 지위는 국가에 따라 다르며, 일부 국가는 금지하거나 제한하고 있고,[154][155][156][157] 다른 국가는 규제 수준이 크게 다른 음식을 허용하고 있다.일부 국가는 허가를 받아 GM 식품의 수입을 허용하지만, GM 제품이 아직 생산되지 않았음에도 불구하고 GM 식품의 재배를 허용하지 않거나(러시아, 노르웨이, 이스라엘), 재배에 대한 규정을 가지고 있다(일본, 한국).GMO 재배를 허용하지 않는 대부분의 국가는 연구를 [158]허용한다.미국과 유럽 사이에 가장 현저한 차이점 중 일부는 발생한다.미국의 정책은 (프로세스가 아닌) 제품에 초점을 맞추고 검증 가능한 과학적 위험만을 검토하며 실질적인 [159]동등성의 개념을 사용합니다.반면 유럽연합은 [160]아마도 세계에서 가장 엄격한 GMO 규제를 가지고 있을 것이다.모든 GMO는 조사 식품과 함께 "새로운 식품"으로 간주되며, 유럽 식품 안전국의 광범위한 사례별 식품 평가를 받는다.인가 기준은 "안전", "선택의 자유", "라벨링" 및 "추적 가능성"[161]의 네 가지 범주로 분류된다.GMO를 재배하는 다른 나라의 규제 수준은 유럽과 미국 사이에 있다.

| 지역 | 규제 기관 | 메모들 |

|---|---|---|

| 미국 | USDA, FDA 및 EPA[150] | |

| 유럽 | 유럽 식품 안전국[161] | |

| 캐나다 | 캐나다 보건 및 캐나다 식품 검사청[162][163] | 원산지[164][165] 방법에 관계없이 새로운 기능을 갖춘 규제 제품 |

| 아프리카 | 동아프리카 공동시장[166] | 최종 결정은 각 [166]개별 국가에 달려 있다. |

| 중국 | 농업유전자공학생물안전국[167] | |

| 인도 | 유전자 조작 및 유전자 공학 승인 위원회[168], 기관 바이오 안전성 위원회 | |

| 아르헨티나 | 국가농업생명공학자문위원회(환경영향), 국가보건농업품질원(식품안전), 국가농업지향([169]무역효과) | 농림축산어업식품부 [169]사무국의 최종 결정 |

| 브라질 | 국가생물안전기술위원회(환경 및 식품안전) 및 각료회의(상업 및 경제적 문제)[169] | |

| 호주. | 유전자 기술 규제 기관(모든 GM 제품 오버오버), 치료용품 관리국(GM 의약품), 호주 뉴질랜드 식품 표준 식품(GM 식품).[170][171] | 각 주 정부는 출시로 시장과 무역에 미치는 영향을 평가하고 승인된 유전자 변형 [171]제품을 관리하기 위한 추가 법률을 적용할 수 있습니다. |

규제당국에 관한 주요 이슈 중 하나는 GM 제품에 라벨을 붙여야 하는지 여부이다.유럽위원회는 정보에 입각한 선택을 허용하고, 잠재적인[172] 허위 광고를 피하고, 건강이나 환경에 대한 악영향이 [173]발견될 경우 제품의 철수를 용이하게 하기 위해 라벨 부착과 추적성이 필요하다고 말한다.미국 의학[174] 협회와 미국 과학 진흥[175] 협회는 자발적인 라벨 부착조차 해롭다는 과학적 증거가 없는 것은 오해의 소지가 있으며 소비자들에게 잘못된 경고를 할 것이라고 말한다.64개국에서 GMO 제품의 라벨 부착이 의무화되어 있습니다.[176]라벨 부착은 (국가마다 다름) GM 콘텐츠레벨 임계값까지 의무화하거나 임의화할 수 있습니다.캐나다와 미국에서는 GM 식품의 라벨 부착이 [177]자발적인 반면, 유럽에서는 승인된 GMO의 0.9%를 초과하는 모든 식품(가공식품 포함) 또는 사료에 라벨을 [160]부착해야 한다.

논란

비평가들은 윤리적, 생태학적, 경제적 문제를 포함한 몇 가지 이유로 유전자 공학의 사용을 반대해왔다.이러한 우려의 대부분은 유전자 조작 작물과 그것들로부터 생산된 식품이 안전한지, 그리고 그것들을 재배하는 것이 환경에 어떤 영향을 미칠지에 관한 것이다.이러한 논란은 소송, 국제 무역 분쟁, 항의로 이어졌고 일부 [178]국가에서는 상업용 제품에 대한 제한적인 규제로 이어졌다.

과학자들이 "신 역할을 하고 있다"는 비난과 다른 종교적 [179]문제들은 처음부터 이 기술에 기인했다.제기된 다른 윤리적 문제에는 [180]생명체의 특허, 지적재산권의 [181]사용, 제품에 [182][183]대한 라벨의 수준, 식품[184] 공급의 통제 및 규제 [185]과정의 객관성이 포함된다.비록 의문이 [186]제기되었지만, 대부분의 경제 연구는 GM 작물을 재배하는 것이 [187][188][189]농부들에게 유익하다는 것을 발견했다.

유전자 조작 작물과 양립 가능한 식물 사이의 유전자 흐름은 선택적인 제초제의 사용 증가와 함께, "초과"[190]가 발생할 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다.다른 환경적 우려는 토양 [191]미생물을 포함한 비표적 유기체에 대한 잠재적 영향과 이차적이고 내성적인 [192][193]해충의 증가를 포함한다.유전자 변형 작물에 대한 환경 영향의 대부분은 이해되기까지 수년이 걸릴 수 있으며 전통적인 농업 [191][194]관행에서도 명백하다.유전자 변형 물고기의 상업화와 함께 그들이 [195]탈출할 경우 환경에 어떤 영향을 미칠지에 대한 우려가 있다.

유전자 조작 식품의 안전성에 대한 세 가지 주요 우려 사항이 있다: 그것들이 알레르기 반응을 일으킬 수 있는지 여부, 유전자가 음식에서 인간 세포로 옮겨갈 수 있는지 여부, 그리고 인간의 섭취가 승인되지 않은 유전자가 다른 [196]작물로 넘어갈 수 있는지 여부.현재 유전자 조작 작물에서 유래한 식품은 기존의 [201][202][203][204][205]식품보다 인간의 건강에 더 큰 위험을 초래하지 않지만,[206][207][208] 각 유전자 조작 식품은 도입 전에 케이스 바이 케이스(case by case)로 테스트해야 한다는 과학적 합의가[197][198][199][200] 있다.그럼에도 불구하고, 일반 대중들은 유전자 조작 식품이 [209][210][211][212]안전하다고 과학자들 보다 덜 인식한다.

대중문화에서

유전공학은 많은 공상과학 [213]소설에서 특징지어진다.프랭크 허버트의 소설 화이트 페스트는 특히 [213]여성을 죽이는 병원체를 만들기 위해 유전자 공학을 의도적으로 사용하는 것을 묘사한다.허버트의 또 다른 창작물 중 하나인 룬 시리즈는 유전 공학을 사용하여 강력한 틸락수를 [214]창조한다.1978년 '브라질에서 온 소년들'과 1993년 '쥬라기 공원'을 제외하고는 유전공학에 대해 관객들에게 알려준 영화는 거의 없다. 둘 다 교훈, 시연, 그리고 과학영화의 [215][216]한 장면을 이용한다.유전공학적인 방법들은 영화에서는 약하게 표현된다; 웰컴 트러스트의 기고자인 마이클 클락은 6번째 날과 같은 영화에서 유전공학 및 생명공학의 묘사를 "심각하게 [216]왜곡되었다"고 말한다.클라크의 견해로는, 생명공학은 전형적으로 "환상적이지만 시각적으로 매력적인 형태"인 반면, 과학은 배경으로 밀려나거나 젊은 독자들에게 [216]적합하도록 허구화된다.

2007년 비디오 게임인 바이오쇼크에서 유전공학은 중앙 줄거리와 우주에서 중요한 역할을 한다.이 게임은 가상의 수중 디스토피아 랩쳐에서 발생하는데, 주민들은 이러한 힘을 부여하는 혈청인 "플라스미드"를 자신에게 주입한 후 유전적인 초인적인 능력을 갖게 된다.또한 랩쳐의 도시에는 범용적으로 조작된 어린 소녀들인 "Little Sisters"와 카바레 가수가 자신의 태아를 유전학자들에게 팔아넘기는 부차적인 줄거리도 있다. 유전학자들이 갓난아기에게 거짓 기억을 심어주고 유전공학으로 성인으로 자라게 하는 것이다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ "Genetic Engineering". Genome.gov. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Terms and Acronyms". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency online. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Vert M, Doi Y, Hellwich KH, Hess M, Hodge P, Kubisa P, Rinaudo M, Schué F (2012). "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04. S2CID 98107080.

- ^ "How does GM differ from conventional plant breeding?". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Erwin E, Gendin S, Kleiman L (22 December 2015). Ethical Issues in Scientific Research: An Anthology. Routledge. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-134-81774-0.

- ^ Alexander DR (May 2003). "Uses and abuses of genetic engineering". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79 (931): 249–51. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.931.249. PMC 1742694. PMID 12782769.

- ^ Nielsen J (1 July 2013). "Production of biopharmaceutical proteins by yeast: advances through metabolic engineering". Bioengineered. 4 (4): 207–11. doi:10.4161/bioe.22856. PMC 3728191. PMID 23147168.

- ^ Qaim M, Kouser S (5 June 2013). "Genetically modified crops and food security". PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e64879. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864879Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064879. PMC 3674000. PMID 23755155.

- ^ a b The European Parliament and the council of the European Union (12 March 2001). "Directive on the release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) Directive 2001/18/EC ANNEX I A". Official Journal of the European Communities.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ a b 유전자 변형 작물이 농업 식품 부문에 미치는 직원 경제적 영향; 페이지 42 용어집 – 2013년 5월 14일 웨이백 기계에서 보관된 용어 및 정의 농업 집행국: "유전자 공학:현대 분자생물학 기술을 통해 특정 유전자를 도입하거나 제거함으로써 유기체의 유전적 재능을 조작하는 것.유전자 공학의 넓은 정의에는 선택적 교배 및 기타 인위적 선택 수단도 포함된다." 2012년 11월 5일 취득

- ^ Van Eenennaam A. "Is Livestock Cloning Another Form of Genetic Engineering?" (PDF). agbiotech. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ Suter DM, Dubois-Dauphin M, Krause KH (July 2006). "Genetic engineering of embryonic stem cells" (PDF). Swiss Medical Weekly. 136 (27–28): 413–5. PMID 16897894. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011.

- ^ Andrianantoandro E, Basu S, Karig DK, Weiss R (16 May 2006). "Synthetic biology: new engineering rules for an emerging discipline". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (2006.0028): 2006.0028. doi:10.1038/msb4100073. PMC 1681505. PMID 16738572.

- ^ "What is genetic modification (GM)?". CSIRO.

- ^ Jacobsen E, Schouten HJ (2008). "Cisgenesis, a New Tool for Traditional Plant Breeding, Should be Exempted from the Regulation on Genetically Modified Organisms in a Step by Step Approach". Potato Research. 51: 75–88. doi:10.1007/s11540-008-9097-y. S2CID 38742532.

- ^ Capecchi MR (October 2001). "Generating mice with targeted mutations". Nature Medicine. 7 (10): 1086–90. doi:10.1038/nm1001-1086. PMID 11590420. S2CID 14710881.

- ^ 직원 바이오테크놀로지 – 2014년 8월 30일 미국 농무부에 보관된 농업 바이오테크놀로지 용어집 "유전자 수정:유전자 공학 또는 다른 전통적인 방법을 통해 특정 용도를 위한 식물 또는 동물의 유전적인 개선 생산.미국 이외의 일부 국가에서는 이 용어를 유전자 공학을 특정하기 위해 사용합니다." 2012년 11월 5일 취득

- ^ Maryanski JH (19 October 1999). "Genetically Engineered Foods". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ Staff (2005년 11월 28일) Health Canada – The Regulic Modified Food Archived in the Wayback Machine Glossary of Genetic Modified: "식물, 동물 또는 박테리아와 같은 유기체는 기존의 관절을 포함한 어떤 방법으로든 유전자 변형된 것으로 간주됩니다.딩. 'GMO'는 유전자 조작 유기체입니다." 2012년 11월 5일 취득

- ^ Root C (2007). Domestication. Greenwood Publishing Groups.

- ^ Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of plants in the old world. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Stableford BM (2004). Historical dictionary of science fiction literature. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8108-4938-9.

- ^ Hershey AD, Chase M (May 1952). "Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage". The Journal of General Physiology. 36 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1085/jgp.36.1.39. PMC 2147348. PMID 12981234.

- ^ "Genetic Engineering". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 2 April 2015.

- ^ Shiv Kant Prasad, Ajay Dash (2008). Modern Concepts in Nanotechnology, Volume 5. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8356-296-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 작성자 파라미터 사용(링크) - ^ Jackson DA, Symons RH, Berg P (October 1972). "Biochemical method for inserting new genetic information into DNA of Simian Virus 40: circular SV40 DNA molecules containing lambda phage genes and the galactose operon of Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 69 (10): 2904–9. Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.2904J. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.10.2904. PMC 389671. PMID 4342968.

- ^ Arnold P (2009). "History of Genetics: Genetic Engineering Timeline".

- ^ Gutschi S, Hermann W, Stenzl W, Tscheliessnigg KH (1 May 1973). "[Displacement of electrodes in pacemaker patients (author's transl)]". Zentralblatt für Chirurgie. 104 (2): 100–4. PMID 433482.

- ^ Jaenisch R, Mintz B (April 1974). "Simian virus 40 DNA sequences in DNA of healthy adult mice derived from preimplantation blastocysts injected with viral DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (4): 1250–4. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.1250J. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.4.1250. PMC 388203. PMID 4364530.

- ^ a b Berg P, Baltimore D, Brenner S, Roblin RO, Singer MF (June 1975). "Summary statement of the Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA molecules". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (6): 1981–4. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.1981B. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.6.1981. PMC 432675. PMID 806076.

- ^ "NIH Guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules". Office of Biotechnology Activities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

- ^ a b Goeddel DV, Kleid DG, Bolivar F, Heyneker HL, Yansura DG, Crea R, Hirose T, Kraszewski A, Itakura K, Riggs AD (January 1979). "Expression in Escherichia coli of chemically synthesized genes for human insulin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (1): 106–10. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76..106G. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.1.106. PMC 382885. PMID 85300.

- ^ US Supreme Court Cases from Justia & Oyez (16 June 1980). "Diamond V Chakrabarty". 447 (303). Supreme.justia.com. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ "Artificial Genes". Time. 15 November 1982. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Bratspies R (2007). "Some Thoughts on the American Approach to Regulating Genetically Modified Organisms". Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy. 16 (3): 101–31. SSRN 1017832.

- ^ a b BBC 뉴스 2002년 6월 14일 GM 농작물: 쓰디쓴 수확?

- ^ Maugh, Thomas H. II (9 June 1987). "Altered Bacterium Does Its Job: Frost Failed to Damage Sprayed Test Crop, Company Says". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ James C (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ James C (1997). "Global Status of Transgenic Crops in 1997" (PDF). ISAAA Briefs No. 5.: 31.

- ^ Bruening G, Lyons JM (2000). "The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato". California Agriculture. 54 (4): 6–7. doi:10.3733/ca.v054n04p6.

- ^ MacKenzie D (18 June 1994). "Transgenic tobacco is European first". New Scientist.

- ^ 유전자 변형 감자 Ok'd For Crops Lawrence Journal-World - 1995년 5월 6일

- ^ 상용화 바이오/GM 작물의 글로벌 현황: 2009 ISAAA Brief 41-2009, 2010년 2월 23일.2010년 8월 10일 취득

- ^ Pennisi E (May 2010). "Genomics. Synthetic genome brings new life to bacterium". Science. 328 (5981): 958–9. doi:10.1126/science.328.5981.958. PMID 20488994.

- ^ Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, et al. (July 2010). "Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome". Science. 329 (5987): 52–6. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...52G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.167.1455. doi:10.1126/science.1190719. PMID 20488990. S2CID 7320517.

- ^ Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, Corrêa IR, Romesberg FE (May 2014). "A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 385–8. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..385M. doi:10.1038/nature13314. PMC 4058825. PMID 24805238.

- ^ Thyer R, Ellefson J (May 2014). "Synthetic biology: New letters for life's alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 291–2. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..291T. doi:10.1038/nature13335. PMID 24805244. S2CID 4399670.

- ^ Pollack A (11 May 2015). "Jennifer Doudna, a Pioneer Who Helped Simplify Genome Editing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (August 2012). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–21. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. PMC 6286148. PMID 22745249.

- ^ Ledford H (March 2016). "CRISPR: gene editing is just the beginning". Nature. 531 (7593): 156–9. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..156L. doi:10.1038/531156a. PMID 26961639.

- ^ Koh H, Kwon S, Thomson M (26 August 2015). Current Technologies in Plant Molecular Breeding: A Guide Book of Plant Molecular Breeding for Researchers. Springer. p. 242. ISBN 978-94-017-9996-6.

- ^ "How to Make a GMO". Science in the News. 9 August 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Nicholl, Desmond S.T. (29 May 2008). An Introduction to Genetic Engineering. Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-139-47178-7.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. (2002). "8". Isolating, Cloning, and Sequencing DNA (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science.

- ^ Kaufman RI, Nixon BT (July 1996). "Use of PCR to isolate genes encoding sigma54-dependent activators from diverse bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (13): 3967–70. doi:10.1128/jb.178.13.3967-3970.1996. PMC 232662. PMID 8682806.

- ^ Liang J, Luo Y, Zhao H (2011). "Synthetic biology: putting synthesis into biology". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 3 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1002/wsbm.104. PMC 3057768. PMID 21064036.

- ^ "5. The Process of Genetic Modification". www.fao.org. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ J M Blatny, T Brautaset, C H Winther-Larsen, K Haugan 및 S Valla: "RK2 레플리콘을 기반으로 한 광범위한 호스트 복제 및 발현 벡터의 구축 및 사용" 환경. 미생물1997, 제63권, 제2호, 370페이지

- ^ Berg P, Mertz JE (January 2010). "Personal reflections on the origins and emergence of recombinant DNA technology". Genetics. 184 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.112144. PMC 2815933. PMID 20061565.

- ^ Chen I, Dubnau D (March 2004). "DNA uptake during bacterial transformation". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2 (3): 241–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro844. PMID 15083159. S2CID 205499369.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health (1 January 2004). Methods and Mechanisms for Genetic Manipulation of Plants, Animals, and Microorganisms. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ Gelvin SB (March 2003). "Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the "gene-jockeying" tool". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 67 (1): 16–37, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.67.1.16-37.2003. PMC 150518. PMID 12626681.

- ^ Head G, Hull RH, Tzotzos GT (2009). Genetically Modified Plants: Assessing Safety and Managing Risk. London: Academic Pr. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-12-374106-6.

- ^ Tuomela M, Stanescu I, Krohn K (October 2005). "Validation overview of bio-analytical methods". Gene Therapy. 12 Suppl 1 (S1): S131-8. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302627. PMID 16231045.

- ^ Narayanaswamy, S. (1994). Plant Cell and Tissue Culture. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. vi. ISBN 978-0-07-460277-5.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health (2004). Methods and Mechanisms for Genetic Manipulation of Plants, Animals, and Microorganisms. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ Hohn B, Levy AA, Puchta H (April 2001). "Elimination of selection markers from transgenic plants". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 12 (2): 139–43. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00188-9. PMID 11287227.

- ^ Setlow JK (31 October 2002). Genetic Engineering: Principles and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-306-47280-0.

- ^ Deepak S, Kottapalli K, Rakwal R, Oros G, Rangappa K, Iwahashi H, Masuo Y, Agrawal G (June 2007). "Real-Time PCR: Revolutionizing Detection and Expression Analysis of Genes". Current Genomics. 8 (4): 234–51. doi:10.2174/138920207781386960. PMC 2430684. PMID 18645596.

- ^ Grizot S, Smith J, Daboussi F, Prieto J, Redondo P, Merino N, Villate M, Thomas S, Lemaire L, Montoya G, Blanco FJ, Pâques F, Duchateau P (September 2009). "Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (16): 5405–19. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp548. PMC 2760784. PMID 19584299.

- ^ Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson MG, West A, Bidney D, Falco SC, Jantz D, Lyznik LA (January 2010). "Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease". The Plant Journal. 61 (1): 176–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04041.x. PMID 19811621.

- ^ Townsend JA, Wright DA, Winfrey RJ, Fu F, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Voytas DF (May 2009). "High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases". Nature. 459 (7245): 442–5. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..442T. doi:10.1038/nature07845. PMC 2743854. PMID 19404258.

- ^ Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi VM, Rock JM, Wu YY, Katibah GE, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson MA, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt SA, Butler HJ, Hinkley SJ, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD (May 2009). "Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases". Nature. 459 (7245): 437–41. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..437S. doi:10.1038/nature07992. PMID 19404259. S2CID 4323298.

- ^ Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF (October 2010). "Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases". Genetics. 186 (2): 757–61. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.120717. PMC 2942870. PMID 20660643.

- ^ Li T, Huang S, Jiang WZ, Wright D, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B (January 2011). "TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (1): 359–72. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq704. PMC 3017587. PMID 20699274.

- ^ Esvelt KM, Wang HH (2013). "Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology". Molecular Systems Biology. 9: 641. doi:10.1038/msb.2012.66. PMC 3564264. PMID 23340847.

- ^ Tan WS, Carlson DF, Walton MW, Fahrenkrug SC, Hackett PB (2012). "Precision editing of large animal genomes". Advances in Genetics Volume 80. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 80. pp. 37–97. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-404742-6.00002-8. ISBN 978-0-12-404742-6. PMC 3683964. PMID 23084873.

- ^ a b Malzahn A, Lowder L, Qi Y (24 April 2017). "Plant genome editing with TALEN and CRISPR". Cell & Bioscience. 7: 21. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0148-4. PMC 5404292. PMID 28451378.

- ^ Ekker SC (2008). "Zinc finger-based knockout punches for zebrafish genes". Zebrafish. 5 (2): 121–3. doi:10.1089/zeb.2008.9988. PMC 2849655. PMID 18554175.

- ^ Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Freyvert Y, Zeitler B, Miller JC, Choi VM, Jenkins SS, Wood A, Cui X, Meng X, Vincent A, Lam S, Michalkiewicz M, Schilling R, Foeckler J, Kalloway S, Weiler H, Ménoret S, Anegon I, Davis GD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Jacob HJ, Buelow R (July 2009). "Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases". Science. 325 (5939): 433. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..433G. doi:10.1126/science.1172447. PMC 2831805. PMID 19628861.

- ^ "Genetic Modification of Bacteria". Annenberg Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ Panesar, Pamit et al. (2010) "식품 가공의 효소:기초와 응용가능성", I K 국제출판사 제10장, ISBN 978-93-80026-33-6

- ^ "GM traits list". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications.

- ^ "ISAAA Brief 43-2011: Executive Summary". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications.

- ^ Connor S (2 November 2007). "The mouse that shook the world". The Independent.

- ^ Avise JC (2004). The hope, hype & reality of genetic engineering: remarkable stories from agriculture, industry, medicine, and the environment. Oxford University Press US. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-516950-8.

- ^ "Engineering algae to make complex anti-cancer 'designer' drug". PhysOrg. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Roque AC, Lowe CR, Taipa MA (2004). "Antibodies and genetically engineered related molecules: production and purification". Biotechnology Progress. 20 (3): 639–54. doi:10.1021/bp030070k. PMID 15176864. S2CID 23142893.

- ^ Rodriguez LL, Grubman MJ (November 2009). "Foot and mouth disease virus vaccines". Vaccine. 27 Suppl 4: D90-4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.039. PMID 19837296.

- ^ "Background: Cloned and Genetically Modified Animals". Center for Genetics and Society. 14 April 2005. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Knockout Mice". Nation Human Genome Research Institute. 2009.

- ^ Fischer A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Cavazzana-Calvo M (June 2010). "20 years of gene therapy for SCID". Nature Immunology. 11 (6): 457–60. doi:10.1038/ni0610-457. PMID 20485269. S2CID 11300348.

- ^ Ledford H (2011). "Cell therapy fights leukaemia". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.472.

- ^ Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, Park J, Wang X, Cowell LG, et al. (March 2013). "CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Science Translational Medicine. 5 (177): 177ra38. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. PMC 3742551. PMID 23515080.

- ^ LeWitt PA, Rezai AR, Leehey MA, Ojemann SG, Flaherty AW, Eskandar EN, et al. (April 2011). "AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial". The Lancet. Neurology. 10 (4): 309–19. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70039-4. PMID 21419704. S2CID 37154043.

- ^ 갤러거, 제임스(2012년 11월 2일) BBC 뉴스 - 유전자 치료: Glibera는 유럽위원회에 의해 승인되었다.Bbc.co.uk 를 참조해 주세요.2012년 12월 15일에 취득.

- ^ Richards S. "Gene Therapy Arrives in Europe". The Scientist. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Genetically Altered Skin Saves A Boy Dying of a Rare Disease". NPR.org. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "1990 The Declaration of Inuyama". 5 August 2001. Archived from the original on 5 August 2001.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: 원래 URL 상태를 알 수 없습니다(링크). - ^ Smith KR, Chan S, Harris J (October 2012). "Human germline genetic modification: scientific and bioethical perspectives". Archives of Medical Research. 43 (7): 491–513. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.09.003. PMID 23072719.

- ^ Kolata G (23 April 2015). "Chinese Scientists Edit Genes of Human Embryos, Raising Concerns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, et al. (May 2015). "CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes". Protein & Cell. 6 (5): 363–372. doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. PMC 4417674. PMID 25894090.

- ^ Wade N (3 December 2015). "Scientists Place Moratorium on Edits to Human Genome That Could Be Inherited". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Bergeson ER (1997). "The Ethics of Gene Therapy".

- ^ Hanna KE. "Genetic Enhancement". National Human Genome Research Institute.

- ^ Begley S (28 November 2018). "Amid uproar, Chinese scientist defends creating gene-edited babies – STAT". STAT.

- ^ Li, Emily (31 July 2020). "Diagnostic Value of Spiral CT Chest Enhanced Scan". Journal of Clinical and Nursing Research.

- ^ "GM pigs best bet for organ transplant". Medical News Today. 21 September 2003. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Harmon A (26 November 2015). "Open Season Is Seen in Gene Editing of Animals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Praitis V, Maduro MF (2011). "Transgenesis in C. elegans". Methods in Cell Biology. 106: 161–85. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-544172-8.00006-2. ISBN 9780125441728. PMID 22118277.

- ^ "Rediscovering Biology – Online Textbook: Unit 13 Genetically Modified Organisms". www.learner.org. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "Studying Gene Expression and Function".

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Park SJ, Cochran JR (25 September 2009). Protein Engineering and Design. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7659-2.

- ^ Kurnaz IA (8 May 2015). Techniques in Genetic Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-6090-8.

- ^ "Applications of Genetic Engineering". Microbiologyprocedure. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Biotech: What are transgenic organisms?". Easyscience. 2002. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Savage N (1 August 2007). "Making Gasoline from Bacteria: A biotech startup wants to coax fuels from engineered microbes". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Summers R (24 April 2013). "Bacteria churn out first ever petrol-like biofuel". New Scientist. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "Applications of Some Genetically Engineered Bacteria". Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Sanderson K (24 February 2012). "New Portable Kit Detects Arsenic in Wells". Chemical and Engineering News. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB (2011). Campbell Biology Ninth Edition. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-321-55823-7.

- ^ "New virus-built battery could power cars, electronic devices". Web.mit.edu. 2 April 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Hidden Ingredient in New, Greener Battery: A Virus". Npr.org. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Researchers Synchronize Blinking 'Genetic Clocks' – Genetically Engineered Bacteria That Keep Track of Time". ScienceDaily. 24 January 2010.

- ^ Suszkiw J (November 1999). "Tifton, Georgia: A Peanut Pest Showdown". Agricultural Research. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ Magaña-Gómez JA, de la Barca AM (January 2009). "Risk assessment of genetically modified crops for nutrition and health". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00130.x. PMID 19146501.

- ^ Islam A (2008). "Fungus Resistant Transgenic Plants: Strategies, Progress and Lessons Learnt". Plant Tissue Culture and Biotechnology. 16 (2): 117–38. doi:10.3329/ptcb.v16i2.1113.

- ^ "Disease resistant crops". GMO Compass. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010.

- ^ Demont M, Tollens E (2004). "First impact of biotechnology in the EU: Bt maize adoption in Spain". Annals of Applied Biology. 145 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00376.x.

- ^ Chivian E, Bernstein A (2008). Sustaining Life. Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-517509-7.

- ^ a b Whitman DB (2000). "Genetically Modified Foods: Harmful or Helpful?". Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Pollack A (19 November 2015). "Genetically Engineered Salmon Approved for Consumption". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ 유채씨(카놀라)는 중간 길이의 지방산을 증가시키기 위해 캘리포니아 만 식물(Umbellularia Californica)의 "12:0 티오에스테라아제" (TE) 효소를 코드하는 유전자에 의해 기름 함량을 수정하도록 유전공학적으로 조작되었습니다. Geo-pie.cornell.edu 2009년 7월 5일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브되었습니다.

- ^ Bomgardner MM (2012). "Replacing Trans Fat: New crops from Dow Chemical and DuPont target food makers looking for stable, heart-healthy oils". Chemical and Engineering News. 90 (11): 30–32. doi:10.1021/cen-09011-bus1.

- ^ Kramer MG, Redenbaugh K (1 January 1994). "Commercialization of a tomato with an antisense polygalacturonase gene: The FLAVR SAVR™ tomato story". Euphytica. 79 (3): 293–97. doi:10.1007/BF00022530. ISSN 0014-2336. S2CID 45071333.

- ^ Marvier M (2008). "Pharmaceutical crops in California, benefits and risks. A review" (PDF). Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 28 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1051/agro:2007050. S2CID 29538486.

- ^ "FDA Approves First Human Biologic Produced by GE Animals". US Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ Rebêlo P (15 July 2004). "GM cow milk 'could provide treatment for blood disease'". SciDev.

- ^ Angulo E, Cooke B (December 2002). "First synthesize new viruses then regulate their release? The case of the wild rabbit". Molecular Ecology. 11 (12): 2703–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01635.x. hdl:10261/45541. PMID 12453252. S2CID 23916432.

- ^ Adams JM, Piovesan G, Strauss S, Brown S (2 August 2002). "The Case for Genetic Engineering of Native and Landscape Trees against Introduced Pests and Diseases". Conservation Biology. 16 (4): 874–79. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00523.x. S2CID 86697592.

- ^ Thomas MA, Roemer GW, Donlan CJ, Dickson BG, Matocq M, Malaney J (September 2013). "Ecology: Gene tweaking for conservation". Nature. 501 (7468): 485–6. doi:10.1038/501485a. PMID 24073449.

- ^ Pasko JM (4 March 2007). "Bio-artists bridge gap between arts, sciences: Use of living organisms is attracting attention and controversy". msnbc.

- ^ Jackson J (6 December 2005). "Genetically Modified Bacteria Produce Living Photographs". National Geographic News.

- ^ Phys.Org 웹사이트2005년 4월 4일 "식물 유전자 치환 결과 세계 유일의 푸른 장미"

- ^ Katsumoto Y, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Fukui Y, Brugliera F, Holton TA, Karan M, Nakamura N, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Togami J, Pigeaire A, Tao GQ, Nehra NS, Lu CY, Dyson BK, Tsuda S, Ashikari T, Kusumi T, Mason JG, Tanaka Y (November 2007). "Engineering of the rose flavonoid biosynthetic pathway successfully generated blue-hued flowers accumulating delphinidin". Plant & Cell Physiology. 48 (11): 1589–600. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.319.8365. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm131. PMID 17925311.

- ^ PCT 어플리케이션 WO2000049150 "형광 트랜스제닉 관상어 발생을 위한 키메라 유전자 구조"발표 싱가포르 국립대학교 [1]

- ^ Stewart CN (April 2006). "Go with the glow: fluorescent proteins to light transgenic organisms" (PDF). Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (4): 155–62. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.02.002. PMID 16488034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Berg P, Baltimore D, Boyer HW, Cohen SN, Davis RW, Hogness DS, Nathans D, Roblin R, Watson JD, Weissman S, Zinder ND (July 1974). "Letter: Potential biohazards of recombinant DNA molecules" (PDF). Science. 185 (4148): 303. Bibcode:1974Sci...185..303B. doi:10.1126/science.185.4148.303. PMC 388511. PMID 4600381.

- ^ McHughen A, Smyth S (January 2008). "US regulatory system for genetically modified [genetically modified organism (GMO), rDNA or transgenic] crop cultivars". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 6 (1): 2–12. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00300.x. PMID 17956539.

- ^ a b U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy (June 1986). "Coordinated framework for regulation of biotechnology; announcement of policy; notice for public comment" (PDF). Federal Register. 51 (123): 23302–50. PMID 11655807. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}:author=범용명(도움말)이 있습니다. - ^ Redick, T.P. (2007). "The Cartagena Protocol on biosafety: Precautionary priority in biotech crop approvals and containment of commodities shipments, 2007". Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy. 18: 51–116.

- ^ "About the Protocol". The Biosafety Clearing-House (BCH). 29 May 2012.

- ^ "AgBioForum 13(3): Implications of Import Regulations and Information Requirements under the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety for GM Commodities in Kenya". 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ 유전자 조작 생물에 대한 제한.미국 의회도서관, 2014년 3월(LL 파일 번호 2013-009894)여러 국가에 대한 요약입니다.경유로

- ^ Bashshur R (February 2013). "FDA and Regulation of GMOs". American Bar Association. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Sifferlin A (3 October 2015). "Over Half of E.U. Countries Are Opting Out of GMOs". Time.

- ^ Lynch D, Vogel D (5 April 2001). "The Regulation of GMOs in Europe and the United States: A Case-Study of Contemporary European Regulatory Politics". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms - Law Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 22 January 2017.

- ^ Emily Marden, 위험과 규제: 유전자 조작 식품과 농업에 관한 미국 규제 정책, 44 B.C.L. Rev. 733 (2003) [2]

- ^ a b Davison J (2010). "GM plants: Science, politics and EC regulations". Plant Science. 178 (2): 94–98. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.12.005.

- ^ a b GMO 나침반: 유럽 규제 시스템.2012년 8월 14일 Wayback Machine Retrived 2012년 7월 28일에 아카이브 완료.

- ^ Government of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (20 March 2015). "Information for the general public". www.inspection.gc.ca.

- ^ Forsberg, Cecil W. (23 April 2013). "Genetically Modified Foods". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ 에반스, 브렌트, 루페스쿠, 미하이 (2012년 7월 15일)캐나다 - 농업 생명공학 연간– 2012년 12월 15일 아카이브 (Wayback Machine GAIN (Global Agricultural Information Network) 보고서 CA12029, 미국 농무부, 2012년 11월 5일 회수

- ^ McHugen A (14 September 2000). "Chapter 1: Hors-d'oeuvres and entrees/What is genetic modification? What are GMOs?". Pandora's Picnic Basket. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850674-4.

- ^ a b "Editorial: Transgenic harvest". Nature. 467 (7316): 633–634. 2010. Bibcode:2010Natur.467R.633.. doi:10.1038/467633b. PMID 20930796.

- ^ "AgBioForum 5(4): Agricultural Biotechnology Development and Policy in China". 5 September 2003. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ "TNAU Agritech Portal :: Bio Technology". agritech.tnau.ac.in.

- ^ a b c "BASF presentation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

- ^ 농업 – 주요 산업부 2011년 3월 29일 웨이백 머신에 아카이브

- ^ a b "Welcome to the Office of the Gene Technology Regulator Website". Office of the Gene Technology Regulator. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 On Genetically Modified Food And Feed" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2014.

The labeling should include objective information to the effect that a food or feed consists of, contains or is produced from GMOs. Clear labeling, irrespective of the detectability of DNA or protein resulting from the genetic modification in the final product, meets the demands expressed in numerous surveys by a large majority of consumers, facilitates informed choice and precludes potential misleading of consumers as regards methods of manufacture or production.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 1830/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 concerning the traceability and labeling of genetically modified organisms and the traceability of food and feed products produced from genetically modified organisms and amending Directive 2001/18/EC". Official Journal L 268. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2003. pp. 24–28.

(3) Traceability requirements for GMOs should facilitate both the withdrawal of products where unforeseen adverse effects on human health, animal health or the environment, including ecosystems, are established, and the targeting of monitoring to examine potential effects on, in particular, the environment. Traceability should also facilitate the implementation of risk management measures in accordance with the precautionary principle. (4) Traceability requirements for food and feed produced from GMOs should be established to facilitate accurate labeling of such products.

- ^ "Report 2 of the Council on Science and Public Health: Labeling of Bioengineered Foods" (PDF). American Medical Association. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012.

- ^ 미국과학진보협회(AAAS), 이사회(2012).유전자 변형 식품의 라벨 부착에 관한 AAAS 이사회 성명 및 관련 보도 자료: 2013년 11월 4일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 GM 식품 라벨의 법적 의무화는 소비자를 오인하고 허위 경보를 발생시킬 수 있다

- ^ Hallenbeck T (27 April 2014). "How GMO labeling came to pass in Vermont". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "The Regulation of Genetically Modified Foods". Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ Sheldon IM (1 March 2002). "Regulation of biotechnology: will we ever 'freely' trade GMOs?". European Review of Agricultural Economics. 29 (1): 155–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.7670. doi:10.1093/erae/29.1.155. ISSN 0165-1587.

- ^ Dabrock P (December 2009). "Playing God? Synthetic biology as a theological and ethical challenge". Systems and Synthetic Biology. 3 (1–4): 47–54. doi:10.1007/s11693-009-9028-5. PMC 2759421. PMID 19816799.

- ^ Brown C (October 2000). "Patenting life: genetically altered mice an invention, court declares". CMAJ. 163 (7): 867–8. PMC 80518. PMID 11033718.

- ^ Zhou W (10 August 2015). "The Patent Landscape of Genetically Modified Organisms". Science in the News. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Puckett L (20 April 2016). "Why The New GMO Food-Labeling Law Is So Controversial". Huffington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Miller H (12 April 2016). "GMO food labels are meaningless". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Savage S. "Who Controls The Food Supply?". Forbes. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Knight AJ (14 April 2016). Science, Risk, and Policy. Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-317-28081-1.

- ^ Hakim D (29 October 2016). "Doubts About the Promised Bounty of Genetically Modified Crops". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Areal FJ, Riesgo L, Rodríguez-Cerezo E (1 February 2013). "Economic and agronomic impact of commercialized GM crops: a meta-analysis". The Journal of Agricultural Science. 151 (1): 7–33. doi:10.1017/S0021859612000111. S2CID 85891950.

- ^ Finger R, El Benni N, Kaphengst T, Evans C, Herbert S, Lehmann B, Morse S, Stupak N (10 May 2011). "A Meta Analysis on Farm-Level Costs and Benefits of GM Crops" (PDF). Sustainability. 3 (5): 743–62. doi:10.3390/su3050743.

- ^ Klümper W, Qaim M (3 November 2014). "A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops". PLOS ONE. 9 (11): e111629. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1629K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111629. PMC 4218791. PMID 25365303.

- ^ Qiu J (2013). "Genetically modified crops pass benefits to weeds". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.13517. S2CID 87415065.

- ^ a b "GMOs and the environment". www.fao.org. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Dively GP, Venugopal PD, Finkenbinder C (30 December 2016). "Field-Evolved Resistance in Corn Earworm to Cry Proteins Expressed by Transgenic Sweet Corn". PLOS ONE. 11 (12): e0169115. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1169115D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169115. PMC 5201267. PMID 28036388.

- ^ Qiu, Jane (13 May 2010). "GM crop use makes minor pests major problem". Nature News. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.464.7885. doi:10.1038/news.2010.242.

- ^ Gilbert N (May 2013). "Case studies: A hard look at GM crops". Nature. 497 (7447): 24–6. Bibcode:2013Natur.497...24G. doi:10.1038/497024a. PMID 23636378.

- ^ "Are GMO Fish Safe for the Environment? Accumulating Glitches Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ "Q&A: genetically modified food". World Health Organization. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Nicolia A, Manzo A, Veronesi F, Rosellini D (March 2014). "An overview of the last 10 years of genetically engineered crop safety research". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 34 (1): 77–88. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.823595. PMID 24041244. S2CID 9836802.

We have reviewed the scientific literature on GE crop safety for the last 10 years that catches the scientific consensus matured since GE plants became widely cultivated worldwide, and we can conclude that the scientific research conducted so far has not detected any significant hazard directly connected with the use of GM crops. The literature about Biodiversity and the GE food/feed consumption has sometimes resulted in animated debate regarding the suitability of the experimental designs, the choice of the statistical methods or the public accessibility of data. Such debate, even if positive and part of the natural process of review by the scientific community, has frequently been distorted by the media and often used politically and inappropriately in anti-GE crops campaigns.

- ^ "State of Food and Agriculture 2003–2004. Agricultural Biotechnology: Meeting the Needs of the Poor. Health and environmental impacts of transgenic crops". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Currently available transgenic crops and foods derived from them have been judged safe to eat and the methods used to test their safety have been deemed appropriate. These conclusions represent the consensus of the scientific evidence surveyed by the ICSU (2003) and they are consistent with the views of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002). These foods have been assessed for increased risks to human health by several national regulatory authorities (inter alia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, the United Kingdom and the United States) using their national food safety procedures (ICSU). To date no verifiable untoward toxic or nutritionally deleterious effects resulting from the consumption of foods derived from genetically modified crops have been discovered anywhere in the world (GM Science Review Panel). Many millions of people have consumed foods derived from GM plants – mainly maize, soybean and oilseed rape – without any observed adverse effects (ICSU).

- ^ Ronald P (May 2011). "Plant genetics, sustainable agriculture and global food security". Genetics. 188 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128553. PMC 3120150. PMID 21546547.

There is broad scientific consensus that genetically engineered crops currently on the market are safe to eat. After 14 years of cultivation and a cumulative total of 2 billion acres planted, no adverse health or environmental effects have resulted from commercialization of genetically engineered crops (Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Committee on Environmental Impacts Associated with Commercialization of Transgenic Plants, National Research Council and Division on Earth and Life Studies 2002). Both the U.S. National Research Council and the Joint Research Centre (the European Union's scientific and technical research laboratory and an integral part of the European Commission) have concluded that there is a comprehensive body of knowledge that adequately addresses the food safety issue of genetically engineered crops (Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health and National Research Council 2004; European Commission Joint Research Centre 2008). These and other recent reports conclude that the processes of genetic engineering and conventional breeding are no different in terms of unintended consequences to human health and the environment (European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation 2010).

- ^ 단, 다음 항목도 참조하십시오.도밍고 JL, Giné Bordonaba J(2011년 5월)."유전자 변형 작물의 안전성 평가에 관한 학문적인 검토".환경 국제적이다. 37(4):734–42. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2011.01.003.PMID 21296423.그럼에도 불구하고 연구 구체적으로 유전자 조작 식물의 안전성 평가에만 수를 여전히 제한적이다.하지만, 그것은 처음으로 연구 팀, 그들의 연구 기준에(주로 콩 옥수수)고 영양가 있는 각각의 독특한 기존의 일반 비 유전자 변형 농산물 식물로서 안전하다 GM제품, 그리고 여전히 심각한 우려를 증폭시키고 각종의 많은, obs 제안의 수가, 특정한 평형 반듯이 누우는 것이 중요하다.Erved고, 또한 언급할 가치가 있는 연구는, 기존 번식으로 도출한 것 안전하고 영양도 이 유전자 조작 식물을 상업화의 책임을 져야 한다 생명 공학 회사나 동료들에 의해 주로 연주됬다 왔다는 GMfoods가 있는지 보여 주는 대부분의.아무튼, 이번 연구 최근 몇년간 과학 학술지에 기업이 발행의 부족으로 비교에서 현저한 사전을 나타냅니다.Krimsky S(2015년)."한 Illusory 합의 GMO건강 평가 뒤에"(PDF).과학, 기술,&인간의 가치. 40(6):883–914. doi:10.1177/0162243915598381.S2CID 40855100.2월 7일 2016년에 있는 원본(PDF)에서 Archived.10월 30일 2016년 Retrieved.나는 존경 받는 과학자들의 추천 글이 말 그대로 유전자 변형 농산물의 건강에 미치는 영향에 대해 전혀 과학적 논란이 일고 있다. 이 기사 시작했다.과학적 문학으로 내 조사 또 다른 이야기를 한다그리고 대비:Panchin AY, Tuzhikov AI(3월 2017년)."다수의 비교에 대해 수정 출간된 GMO연구의 위험이 없다는 증거를 전혀 찾을 수".생명 공학에서 중요한 살펴라. 37(2):213–217. doi:10.3109/07388551.2015.1130684.PMID 26767435.S2CID 11786594.여기, 우리는 많은 글을 일부는 힘차게 그리고 부정적으로 그리고 심지어 GMO금수 조치, 데이터의 통계적 평가에서 공통된 결함 같은 정치적 행동을 불러일으켰다 GM작물에 대한 일반 국민의 의견에 영향을 끼쳤다 것을 보여 준다.이러한 흠들에 대해 설명을 우리는 데이터가 이 기사에서 제시한 유전자 변형 유기체에 해를 입게 된 실질적인 증거를 제공하지 않다고 결론 내렸습니다.그 제시된 기사들 유전자 변형 농산물의 해로운 것을 제안한 국민의 높은 관심을 받았다.그러나, 그들의 주장에도 불구하고, 실제로 해로운 것과 공부를 유전자 변형 농산물의 실질적인 등가 부족에 대한 증거를 약화시키고 있다.우리는 유전자 변형 농산물은 지난 10년 1783년을 출간했다 기사가 실린 그것은 심지어 이러한 차이가 현실에 존재하지 않는다는 사실이 그들 중 일부 유전자 변형 농산물과 일반 작물 사이에 바람직하지 않은 차이 보고 했어야 했을 것으로 예상되다고 말한다.그리고 양 YT사인 ChenB(4월 2016년)."규율하는 유전자 변형 농산물 미국에서:과학, 법률과 공공 건강".필기장 식량 농업의 과학의 96(6):1851–5. doi:10.1002/jsfa.7523. PMID 26536836.그러므로 노력과 미국( 들어 도밍고와 Bordonaba, 2011년)중 유전자 변형 식품은 증가하는 정치적 문제를 금지할 라벨링 요구할 놀라운 것은 아니다.전반적으로, 넓은 과학적 합의는 최근 판매한 GM식품이 재래식 음식보다 더 소중한 위험을 야기할 보유하고 있...주요 및 국제 과학과 의학 협회가가 아무 부정적인 인간의 건강에 미치는 영향 GMO음식에 관련된 입증된 날짜에 전문 문학에서 보고되고 있다고 확언하고 있다.여러 우려에도 불구하고, 오늘날, 미국 과학 진흥 협회, 세계 보건 기구와 많은 독립 국제 과학 단체들은 유전자 변형 농산물은 다른 음식만큼 안전하다는 것에 동의한다.전통적인 육종 기술에 비해, 유전 공학이며, 대부분의 경우에 덜이 묘하게 일으킬 가능성이 정확하게 계산합니다.

- ^ "Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors on Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods" (PDF). American Association for the Advancement of Science. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

The EU, for example, has invested more than €300 million in research on the biosafety of GMOs. Its recent report states: "The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of research and involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies." The World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the British Royal Society, and every other respected organization that has examined the evidence has come to the same conclusion: consuming foods containing ingredients derived from GM crops is no riskier than consuming the same foods containing ingredients from crop plants modified by conventional plant improvement techniques.

Pinholster G (25 October 2012). "AAAS Board of Directors: Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could "Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers"". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 8 February 2016. - ^ European Commission. Directorate-General for Research (2010). A decade of EU-funded GMO research (2001–2010) (PDF). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Biotechnologies, Agriculture, Food. European Commission, European Union. doi:10.2777/97784. ISBN 978-92-79-16344-9. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "AMA Report on Genetically Modified Crops and Foods (online summary)". American Medical Association. January 2001. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

A report issued by the scientific council of the American Medical Association (AMA) says that no long-term health effects have been detected from the use of transgenic crops and genetically modified foods, and that these foods are substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts. (from online summary prepared by ISAAA)" "Crops and foods produced using recombinant DNA techniques have been available for fewer than 10 years and no long-term effects have been detected to date. These foods are substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts. (from original report by AMA: [3])

{{cite web}}:외부 링크quote=Bioengineered foods have been consumed for close to 20 years, and during that time, no overt consequences on human health have been reported and/or substantiated in the peer-reviewed literature.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: 원래 URL 상태를 알 수 없습니다(링크). - ^ "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms: United States. Public and Scholarly Opinion". Library of Congress. 9 June 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Several scientific organizations in the US have issued studies or statements regarding the safety of GMOs indicating that there is no evidence that GMOs present unique safety risks compared to conventionally bred products. These include the National Research Council, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Medical Association. Groups in the US opposed to GMOs include some environmental organizations, organic farming organizations, and consumer organizations. A substantial number of legal academics have criticized the US's approach to regulating GMOs.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering; Division on Earth Life Studies; Board on Agriculture Natural Resources; Committee on Genetically Engineered Crops: Past Experience Future Prospects (2016). Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (US). p. 149. doi:10.17226/23395. ISBN 978-0-309-43738-7. PMID 28230933. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

Overall finding on purported adverse effects on human health of foods derived from GE crops: On the basis of detailed examination of comparisons of currently commercialized GE with non-GE foods in compositional analysis, acute and chronic animal toxicity tests, long-term data on health of livestock fed GE foods, and human epidemiological data, the committee found no differences that implicate a higher risk to human health from GE foods than from their non-GE counterparts.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods". World Health Organization. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Different GM organisms include different genes inserted in different ways. This means that individual GM foods and their safety should be assessed on a case-by-case basis and that it is not possible to make general statements on the safety of all GM foods. GM foods currently available on the international market have passed safety assessments and are not likely to present risks for human health. In addition, no effects on human health have been shown as a result of the consumption of such foods by the general population in the countries where they have been approved. Continuous application of safety assessments based on the Codex Alimentarius principles and, where appropriate, adequate post market monitoring, should form the basis for ensuring the safety of GM foods.

- ^ Haslberger AG (July 2003). "Codex guidelines for GM foods include the analysis of unintended effects". Nature Biotechnology. 21 (7): 739–41. doi:10.1038/nbt0703-739. PMID 12833088. S2CID 2533628.

These principles dictate a case-by-case premarket assessment that includes an evaluation of both direct and unintended effects.

- ^ 영국 의학 협회 등 일부 의료 기관들, 더 조심 예방 원리에 의거한 "라고 옹호하다.유전자 조작된 음식과 건강:두번째 중간 statement"(PDF).영국 의료 협회.2004년 3월.3월 21일 2016년 Retrieved.우리의 관점에서, GMfoods의 가능성 유해한 건강 효과를 유발하는 매우 우려들을 많은 동등한 열의를 갖고 전통적으로 파생 음식에 신청하다 표현된 작다.하지만, 안전 관련은 아직 완전히 정보를 현재 사용 가능한 근거로 해고될 수 없다.때 장점과 위험 사이의 균형을 최적화하기 위해 노력하고, 경고의 측면에서 실수를 저지를, 그리고 무엇보다 지식과 경험 축적에서 배운 신중하다.유전자 변형과 같은 어떠한 새로운 기술은 인간 건강과 환경에 가능한 혜택과 위험 요소로 검토되어야 한다.모든 소설 음식과 마찬가지로, 유전자 조작 식품과 관련하여 안전성 평가 사례별로 이루어져야 한다.GM배심원 프로젝트의 구성원들은 유전자 변형의 제반 측면을 인정 받은 전문가들의 관련 과목에서 다양한 단체에 의해 보고되었다.GM심사 위원은 결론은 GMfoods가 현재 사용할 수의 판매와 GM작물의 상업적 성장은 계속되어야 할 것 중단되어야 한다에 도착했다.이런 결론, 급부에 대한 증거가 예방적인 원리와 부족에 근거한 것이었다.그 배심제 유전자 변형 작물의 농업, 환경, 음식 안전과 다른 잠재적인 건강 효과에 대한 영향을 걱정했다.왕립 협회는 검토(2002년)은 인간의 건강이 있는 위험 특정 바이러스 DNA서열의 유전자 변형 식물의 사용과 관련된 잠재적 유발 물질의 농작물에 도입에 대해서는 신중한 요구 무시할 수 있다는 결론을 내렸다 강조했다 증거는 상업적으로 이용 가능한 GMfoods을 일으키는 임상 알레르기 manifes의 부재입니다.tations.그 BMA지만 우리가 안전과 편익의 설득력 있는 증거를 제시하는 데 더 많은 연구와 감시를 위한 호출이 보증하는 견해가 없다는 강력한 증거는 GMfoods는 위험하지 않음을 증명할 수 있습니다.

- ^ Funk C, Rainie L (29 January 2015). "Public and Scientists' Views on Science and Society". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

The largest differences between the public and the AAAS scientists are found in beliefs about the safety of eating genetically modified (GM) foods. Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) scientists say it is generally safe to eat GM foods compared with 37% of the general public, a difference of 51 percentage points.

- ^ Marris C (July 2001). "Public views on GMOs: deconstructing the myths. Stakeholders in the GMO debate often describe public opinion as irrational. But do they really understand the public?". EMBO Reports. 2 (7): 545–8. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve142. PMC 1083956. PMID 11463731.

- ^ Final Report of the PABE research project (December 2001). "Public Perceptions of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Europe". Commission of European Communities. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Scott SE, Inbar Y, Rozin P (May 2016). "Evidence for Absolute Moral Opposition to Genetically Modified Food in the United States". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 11 (3): 315–324. doi:10.1177/1745691615621275. PMID 27217243. S2CID 261060.

- ^ a b "Genetic Engineering". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Koboldt D (29 August 2017). "The Science of Sci-Fi: How Science Fiction Predicted the Future of Genetics". Outer Places. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Moraga R (November 2009). "Modern Genetics in the World of Fiction". Clarkesworld Magazine (38). Archived from the original on 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b c Clark M. "Genetic themes in fiction films: Genetics meets Hollywood". The Wellcome Trust. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

추가 정보

- British Medical Association (1999). The Impact of Genetic Modification on Agriculture, Food and Health. BMJ Books. ISBN 0-7279-1431-6.

- Donnellan, Craig (2004). Genetic Modification (Issues). Independence Educational Publishers. ISBN 1-86168-288-3.

- Morgan S (1 January 2009). Superfoods: Genetic Modification of Foods. Heinemann Library. ISBN 978-1-4329-2455-3.

- Smiley, Sophie (2005). Genetic Modification: Study Guide (Exploring the Issues). Independence Educational Publishers. ISBN 1-86168-307-3.

- Watson JD (2007). Recombinant DNA: Genes and Genomes: A Short Course. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-2866-5.

- Weaver S, Michael M (2003). "An Annotated Bibliography of Scientific Publications on the Risks Associated with Genetic Modification". Wellington, NZ: Victoria University.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - Zaid A, Hughes HG, Porceddu E, Nicholas F (2001). Glossary of Biotechnology for Food and Agriculture – A Revised and Augmented Edition of the Glossary of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering. Rome, Italy: FAO. ISBN 92-5-104683-2.

외부 링크

| 라이브러리 리소스 정보 유전공학 |