비만

Obesity| 비만 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 최적, 과체중, 비만을 나타내는 실루엣과 허리둘레 | |

| 전문 | 내분비학 |

| 증상 | 지방[1] 증가 |

| 합병증 | 심혈관질환, 제2형 당뇨병, 폐쇄성 수면무호흡증, 특정 암, 골관절염, 우울증[2][3] |

| 원인들 | 에너지 밀도가 높은 음식의 과도한 섭취, 앉아서 일하는 일과 생활방식, 그리고 신체활동의 부족, 교통수단의 변화, 도시화, 지원정책의 부족, 건강한 식단에 대한 접근의 부족, 유전학[1][4]. |

| 진단법 | BMI > 30 kg/m2[1] |

| 예방 | 사회 변화, 식품 산업의 변화, 건강한 생활 방식에 대한 접근, 개인의 선택[1] |

| 치료 | 다이어트, 운동, 약물, 수술[5][6] |

| 예후 | 기대수명[2] 단축 |

| 빈도수. | 7억 / 12% (2015년)[7] |

| 사망자 | 연간 280만명 |

| 에 관한 시리즈의 일부 |

| 인체체중 |

|---|

비만은 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있을 정도로 과도한 체지방이 축적된 의학적 상태이며 때로는 질병으로 간주됩니다.[8][9][10] 체중을 키의 제곱으로 나눈 체질량지수(BMI)가 30kg/m2 이상일 때 비만으로 분류되며, 25~30kg/m2 범위는 과체중으로 정의됩니다.[1] 일부 동아시아 국가들은 비만을 계산하기 위해 더 낮은 값을 사용합니다.[11] 비만은 장애의 주요 원인이며 다양한 질병 및 상태, 특히 심혈관 질환, 제2형 당뇨병, 폐쇄성 수면 무호흡증, 특정 유형의 암, 골관절염과 관련이 있습니다.[2][12][13]

비만에는 개인적, 사회경제적, 환경적 원인이 있습니다. 알려진 원인으로는 식이요법, 신체활동, 자동화, 도시화, 유전적 민감성, 약물, 정신장애, 경제정책, 내분비장애, 내분비계 장애, 내분비계 교란 화학물질 노출 등이 있습니다.[1][4][14][15]

특정 시기에 비만인 대다수가 체중 감량을 시도하고 종종 성공하지만, 장기간 체중 감량을 유지하는 것은 드문 일입니다.[16] 비만을 예방하기 위한 효과적이고 잘 정의된 증거 기반의 개입은 없습니다. 비만 예방을 위해서는 사회, 지역사회, 가족 및 개인 수준의 개입을 포함한 복잡한 접근 방식이 필요합니다.[1][13] 운동뿐만 아니라 식단의 변화는 건강 전문가들이 추천하는 주요 치료법입니다.[2] 이러한 식이 선택이 가능하고 저렴하며 접근하기 쉬운 경우 지방 또는 당 함량이 높은 식품과 같은 에너지 밀도가 높은 식품의 소비를 줄이고 식이 섬유 섭취를 늘려 식이 품질을 향상시킬 수 있습니다.[1] 적절한 식단과 함께 식욕을 줄이거나 지방 흡수를 줄이기 위해 약물을 사용할 수 있습니다.[5] 식이요법, 운동, 약물치료 등이 효과적이지 않을 경우 위의 부피나 장의 길이를 줄이기 위해 위 풍선이나 수술을 시행하여 포만감을 일찍 느끼거나 음식물에서 영양소를 흡수하는 능력이 저하될 수 있습니다.[6][17]

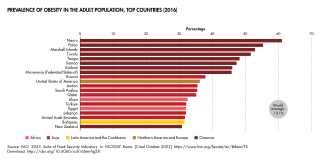

비만은 성인과 어린이의 비율이 증가하면서 전 세계적으로 예방 가능한 주요 사망 원인입니다.[18] 2022년 전 세계적으로 10억 명 이상의 사람들이 비만이었으며(성인 8억 7,900만 명, 어린이 1억 5,900만 명), 이는 1990년 등록된 성인 환자의 두 배 이상(어린이 환자보다 4배 이상 높음)을 나타냅니다.[19][20] 비만은 남성보다 여성에게 더 흔합니다.[1] 오늘날 비만은 세계 대부분에서 오명을 쓰고 있습니다. 반대로, 과거와 현재를 막론하고 일부 문화에서는 비만을 부와 비옥함의 상징으로 여기며 호의적인 시각을 가지고 있습니다.[2][21] 세계보건기구, 미국, 캐나다, 일본, 포르투갈, 독일, 유럽의회 및 의학회, 예를 들어 미국의사협회는 비만을 질병으로 분류합니다. 영국과 같은 다른 나라들은 그렇지 않습니다.[22][23][24][25]

분류

| 카테고리[26] | BMI(kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| 저체중 | < 18.5 |

| 정상중량 | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| 과체중 | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| 비만(Ⅰ급) | 30.0 – 34.9 |

| 비만(Ⅱ급) | 35.0 – 39.9 |

| 비만(Ⅲ급) | ≥ 40.0 |

비만은 일반적으로 건강에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 상당한 체지방 축적으로 정의됩니다.[27] 의료 기관들은 사람들을 키의 제곱을 미터로 나타낸 킬로그램 단위의 체중 비율인 체질량 지수 (BMI)를 기준으로 비만으로 분류하는 경향이 있습니다. 세계보건기구(WHO)는 성인의 경우 "과체중"을 BMI 25 이상, "비만"을 BMI 30 이상으로 정의하고 있습니다.[27] 미국 질병통제예방센터(CDC)는 BMI를 기준으로 비만을 더 세분화하는데, BMI 30~35를 1등급 비만, 35~40을 2등급 비만, 40+를 3등급 비만이라고 합니다.[28]

아이들의 경우 비만 측정은 키와 몸무게와 함께 나이를 고려합니다. 5-19세 어린이의 경우, WHO는 비만을 자신의 나이에 대한 중앙값보다 높은 BMI 2 표준 편차(5세의 경우 약 18세, 19세의 경우 약 30세)로 정의합니다.[27][29] 세계보건기구(WHO)는 5세 미만 어린이의 경우 비만을 키의 중앙값보다 높은 3 표준 편차로 정의하고 있습니다.[27]

WHO 정의에 대한 일부 수정 사항은 특정 조직에 의해 이루어졌습니다.[30] 수술 문헌은 클래스 II와 클래스 III 또는 클래스 III 비만만을 정확한 값이 여전히 논란이 되는 추가 범주로 나눕니다.[31]

- BMI 35 또는 40 kg/m ≥은 심각한 비만입니다.

- BMI가 35 kg/m ≥이고 비만과 관련된 건강 상태 또는 ≥ 40 또는 45 kg/m를 경험하는 것이 병적 비만입니다.

- ≥ 45 또는 50 kg/m의 BMI는 초비만입니다.

아시아 인구가 백인보다 낮은 BMI로 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미치면서 일부 국가에서는 비만을 재정의했습니다. 일본은 비만을 25kg/m2[11] 이상의 BMI로 정의한 반면 중국은 28kg/m2 이상의 BMI를 사용합니다.[30]

학계에서 선호하는 비만 지표는 체지방률(BF%)인데, 이는 체중에 대한 사람의 지방의 총 중량의 비율이며, BMI는 단지 BF%[32]를 근사화하는 방법으로 간주됩니다. 여성의 경우 32%, 남성의 경우 25%를 초과하는 수치는 일반적으로 비만을 나타내는 것으로 간주됩니다.

BMI는 마른 체질량, 특히 근육량의 개인 간 차이를 무시합니다. 육체 노동이나 스포츠에 과중한 사람들은 지방이 적음에도 불구하고 높은 BMI 값을 가질 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, BMI 지표에 따르면 전체 NFL 선수의 절반 이상이 "비만"(BMI ≥ 30)으로 분류되고, 4명 중 1명은 "극도 비만"(BMI ≥ 35)으로 분류됩니다. 그러나, 그들의 평균 체지방률인 14%는 건강한 범위 내에 있습니다.[34] 마찬가지로, 스모 선수들은 BMI에 의해 "심각한 비만" 또는 "매우 심각한 비만"으로 분류될 수 있지만, 많은 스모 선수들은 체지방 비율이 대신 사용될 때 비만으로 분류되지 않습니다(체지방이 25% 미만입니다).[35] 일부 스모 선수들은 많은 양의 살코기 체질량 때문에 높은 BMI 값을 가진 비스모 비교 그룹보다 더 많은 체지방을 가지고 있지 않은 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[35]

건강에 미치는 영향

비만은 다양한 대사 질환, 심혈관 질환, 골관절염, 알츠하이머병, 우울증 및 특정 유형의 암에 걸릴 위험을 증가시킵니다.[36] 비만의 정도와 동반 질환의 유무에 따라 비만은 예상되는 수명보다 2-20년 짧은 것과 관련이 있습니다.[37][36] 높은 BMI는 식단과 신체 활동으로 인한 질병의 직접적인 원인은 아니지만 위험을 나타내는 지표입니다.[13]

사망률

비만은 전 세계적으로 예방 가능한 주요 사망 원인 중 하나입니다.[38][39][40] 사망 위험은 비흡연자의 경우 BMI가 20-25 kg/m로2[41][37][42] 가장 낮고 현재 흡연자의 경우 24-27 kg/m로2 어느 방향으로든 변화와 함께 위험이 증가합니다.[43][44] 이것은 적어도 4개의 대륙에서 적용되는 것으로 보입니다.[42] 다른 연구에 따르면 BMI 및 허리둘레와 사망률의 연관성은 U 또는 J자형인 반면 허리-엉덩이 비율 및 허리-키 비율과 사망률의 연관성은 더 긍정적입니다.[45] 아시아인의 경우 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 위험이 22~25kg/m2 사이에서 증가하기 시작합니다.[46] 2021년 세계보건기구는 비만으로 인해 연간 최소 280만 명이 사망하는 것으로 추정했습니다.[47] 평균적으로 비만은 6~7년, BMI 30~35kg/m는 2~4년, 심한 비만(BMI ≥ 40kg/m)은 10년 수명을 줄입니다.

이환율

비만은 많은 신체적, 정신적 상태의 위험을 증가시킵니다. 이러한 동반 질환은 당뇨병 2형, 고혈압, 고혈압 콜레스테롤 및 높은 중성지방 수치를 포함하는 의학적 장애의 조합인 [2]대사 증후군에서 가장 일반적으로 나타납니다.[49] RAK 병원의 연구에 따르면 비만인 사람들은 긴 코로나에 걸릴 위험이 더 큽니다.[50] CDC는 비만이 심각한 코로나19 질병의 가장 강력한 위험 요소라는 사실을 밝혀냈습니다.[51]

합병증은 비만에 의해 직접적으로 발생하거나 잘못된 식습관이나 좌식 생활과 같은 공통된 원인을 공유하는 메커니즘을 통해 간접적으로 관련이 있습니다. 비만과 특정 조건 사이의 연관성의 강도는 다양합니다. 가장 강력한 것 중 하나는 제2형 당뇨병과의 연관성입니다. 과도한 체지방은 남성 당뇨병 환자의 64%, 여성 당뇨병 환자의 77%를 기반으로 합니다.[52]: 9

건강에 미치는 영향은 지방량 증가에 따른 영향(골관절염, 폐쇄성 수면 무호흡증, 사회적 낙인 등)과 지방세포 수 증가에 따른 영향(당뇨병, 암, 심혈관 질환, 비알코올성 지방간 질환 등)의 두 가지로 나뉩니다.[2][53] 체지방의 증가는 인슐린에 대한 신체의 반응을 변화시켜 잠재적으로 인슐린 저항성을 유발합니다. 증가된 지방은 또한 염증성 상태와 [54][55]혈전성 상태를 만듭니다.[53][56]

이 기사의 일부(아래 표와 관련된 것)를 업데이트해야 합니다.이할 수 바랍니다. (2022년 3월) |

| 의료분야 | 조건. | 의료분야 | 조건. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 심장학 | 피부과 | ||

| 내분비학 및 생식의학 | 소화기학 | ||

| 신경학 | 종양학[70] | ||

| 정신의학 | 호흡기학 | ||

| 류마티스 및 정형외과 | 비뇨기과신학 |

건강 측정 지표

새로운 연구는 임상의에 의해 더 건강한 비만인 사람들을 식별하고 비만인 사람들을 단일 그룹으로 취급하지 않는 방법에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.[81] 비만으로 인한 의학적 합병증을 경험하지 못하는 비만인 사람들을 (대사적으로) 건강한 비만이라고 부르기도 하지만, 이 그룹이 (특히 노인들 사이에서) 존재하는 정도에 대해서는 논쟁이 있습니다.[82] 대사적으로 건강한 것으로 간주되는 사람의 수는 사용되는 정의에 따라 다르며 보편적으로 받아들여지는 정의는 없습니다.[83] 대사이상이 비교적 적은 비만인 사람들이 많고, 소수의 비만인 사람들은 의학적인 합병증이 없습니다.[83] 미국 임상 내분비학자 협회의 지침은 의사들이 제2형 당뇨병 발병 위험을 평가하는 방법을 고려할 때 비만 환자와 함께 위험 계층화를 사용할 것을 요구합니다.[84]: 59–60

2014년, BioSHARE–EU 건강 비만 프로젝트(Maelstrom Research, 맥길 대학 보건 센터의 연구소 산하 팀)는 건강한 비만에 대한 두 가지 정의를 내렸는데, 하나는 더 엄격하고 다른 하나는 덜 엄격합니다.[82][85]

| 덜 엄격함 | 더 엄격하게 | |

|---|---|---|

| 아래와 같이 측정된 혈압으로 약학적 도움이 없음 | ||

| 전체(mmHg) | ≤ 140 | ≤ 130 |

| Systolic (mmHg) | 무차입증 | ≤ 85[clarification needed] |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | ≤ 90 | 무차입증 |

| 아래와 같이 측정된 혈당 수치로 약학적 도움이 없음 | ||

| 혈당(mmol/L) | ≤ 7.0 | ≤ 6.1 |

| 아래와 같이 측정된 중성지방으로 약학적 도움이 없음 | ||

| 금식(mmol/L) | ≤ 1.7 | |

| 비금식 (mmol/L) | ≤ 2.1 | |

| 다음과 같이 측정된 고밀도 지단백으로 약학적 도움이 없음 | ||

| 남자(mmol/L) | > 1.03 | |

| 여성(mmol/L) | > 1.3 | |

| 심혈관 질환 진단 없음 | ||

이러한 기준을 마련하기 위해 BioSHARE는 연령과 담배 사용을 통제하여 비만과 관련된 대사 증후군에 어떤 영향을 미칠 수 있는지 연구했지만 대사적으로 건강한 비만에는 존재하지 않는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[86] 대사적으로 건강한 비만에 대한 다른 정의가 존재하는데, 여기에는 특정 개인에서 신뢰할 수 없는 BMI가 아닌 허리 둘레를 기준으로 한 정의도 포함됩니다.[83]

비만인 사람의 건강에 대한 또 다른 식별 지표는 종아리 힘이며, 이는 비만인 사람의 신체 건강과 양의 상관관계가 있습니다.[87] 일반적으로 신체 구성은 대사적으로 건강한 비만의 존재를 설명하는 데 도움이 된다고 가정됩니다. 대사적으로 건강한 비만은 대사 증후군을 가진 비만인 사람과 체중이 동등한 전체 지방량을 가지고 있음에도 불구하고 낮은 양의 이소성 지방(지방 조직 이외의 조직에 저장된 지방)을 가지고 있는 것으로 종종 발견됩니다.[88]: 1282

서바이벌 패러독스

일반 인구에서 비만의 부정적인 건강 결과는 사용 가능한 연구 증거에 의해 잘 뒷받침되지만 특정 하위 그룹의 건강 결과는 비만 생존 역설로 알려진 현상인 BMI 증가에서 개선되는 것으로 보입니다.[89] 이 역설은 1999년 혈액투석을[89] 받는 과체중과 비만인 사람들에게서 처음 기술되었으며 이후 심부전과 말초동맥질환(PAD)을 가진 사람들에게서 발견되었습니다.[90]

심부전이 있는 사람들의 경우, BMI가 30.0에서 34.9 사이인 사람들은 정상 체중인 사람들보다 사망률이 낮았습니다. 이것은 사람들이 점점 더 병이 들수록 살이 빠지는 경우가 많기 때문입니다.[91] 다른 유형의 심장 질환에서도 비슷한 발견이 이루어졌습니다. 제1급 비만과 심장병을 가진 사람들은 심장병을 가진 정상 체중의 사람들보다 더 큰 심장병을 가지고 있지 않습니다. 그러나 비만도가 높은 사람들의 경우 심혈관 질환이 추가로 발생할 위험이 증가합니다.[92][93] 심장 우회 수술 후에도 과체중과 비만에서 사망률 증가는 보이지 않습니다.[94] 한 연구는 비만인 사람들이 심장 사건 후에 더 공격적인 치료를 받음으로써 생존율이 향상되는 것을 설명할 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[95] 또 다른 연구는 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환(COPD)을 PAD를 가진 사람들에게 고려한다면 비만의 이점은 더 이상 존재하지 않는다는 것을 발견했습니다.[90]

원인들

비만의 "칼로리는 칼로리" 모델은 과도한 음식 에너지 섭취와 신체 활동 부족의 조합을 대부분의 비만 사례의 원인으로 상정합니다.[96] 제한된 수의 사례는 주로 유전학, 의학적 이유 또는 정신 질환으로 인한 것입니다.[15] 이와는 대조적으로, 사회적 차원에서 비만율이 증가하는 것은 쉽게 접근할 수 있고 입맛에 맞는 식단,[97] 자동차에 대한 의존도 증가, 기계화된 제조 때문인 것으로 느껴집니다.[98][99]

불충분한 수면, 내분비계 장애, 특정 약물(예를 들어 비정형 항정신병제)의 사용 증가,[100] 주변 온도 증가, 흡연율 감소,[101] 인구통계학적 변화, 초산모의 산모 연령 증가 등 전 세계적으로 비만율 증가의 원인으로 일부 다른 요인들이 제안되었습니다. 환경으로부터의 후성유전학적 조절 장애에 대한 변화, 구색 교배를 통한 표현형 변이 증가, 다이어트에 대한 사회적 압력 [102]등. 한 연구에 따르면, 이와 같은 요인들은 과도한 음식 에너지 섭취와 신체 활동의 부족만큼 큰 역할을 할 수 있지만,[103] 비만의 어떤 제안된 원인에 대한 효과의 상대적인 크기는 다양하고 불확실합니다. 최종 진술이 이루어지기 전에 인간에 대한 무작위 대조 시험의 일반적인 필요성이 있기 때문입니다.[104]

내분비학회에 따르면, "비만이 단순히 과도한 체중의 수동적인 축적으로부터 발생하는 것이 아니라 에너지 항상성 체계의 장애라는 증거가 증가하고 있습니다."[105]

다이어트

| 데이터 없음 <1,600 (<6,700) 1,600–1,800 (6,700–7,500) 1,800–2,000 (7,500–8,400) 2,000–2,200 (8,400–9,200) 2,200–2,400 (9,200–10,000) 2,400–2,600 (10,000–10,900) | 2,600–2,800 (10,900–11,700) 2,800–3,000 (11,700–12,600) 3,000–3,200 (12,600–13,400) 3,200–3,400 (13,400–14,200) 3,400–3,600 (14,200–15,100) >3,600 (>15,100)

|

입맛에 맞는 고열량 음식(특히 지방, 설탕 및 특정 동물성 단백질)에 대한 과도한 식욕은 전 세계적으로 비만을 유발하는 주요 요인으로 간주되며, 이는 아마도 식습관에 영향을 미치는 신경 전달 물질의 불균형 때문일 것입니다.[107] 1인당 식이 에너지 공급은 지역과 국가에 따라 현저하게 다릅니다. 또한 시간이 지남에 따라 크게 변화했습니다.[106] 1970년대 초반부터 1990년대 후반까지 동유럽을 제외한 전 세계 모든 지역에서 1인당 하루 평균 식량 에너지(식량 구입)가 증가했습니다. 미국은 1996년에 1인당 3,654 칼로리 (15,290 kJ)로 가장 높은 가용성을 보였습니다.[106] 이는 2003년에 3,754 칼로리(15,710 kJ)로 더욱 증가했습니다.[106] 1990년대 후반 동안 유럽인들은 1인당 3,394 칼로리(14,200kJ)를 가지고 있었고, 아시아의 개발도상국에서는 1인당 2,648 칼로리(11,080kJ), 사하라 사막 이남의 아프리카 사람들은 1인당 2,176 칼로리(9,100kJ)를 가지고 있었습니다.[106][108] 총 음식 에너지 소비량은 비만과 관련이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[109]

식이 지침의[110] 광범위한 가용성은 과식과 잘못된 식이 선택의 문제를 해결하는 데 거의 도움이 되지 않았습니다.[111] 1971년부터 2000년까지 미국의 비만율은 14.5%에서 30.9%[112]로 증가했습니다. 같은 기간 동안 평균적인 음식 에너지 소비량이 증가했습니다. 여성의 경우 하루 평균 335칼로리(1971년 1,542칼로리(6,450kJ), 2004년 1,877칼로리(7,850kJ) 증가한 반면, 남성의 경우 하루 평균 168칼로리(700kJ) 증가(1971년 2,450칼로리(10,300kJ), 2004년 2,618칼로리(10,950kJ) 증가했습니다. 이 여분의 음식 에너지의 대부분은 지방 소비보다는 탄수화물 소비의 증가에서 비롯됩니다.[113] 이러한 여분의 탄수화물의 주요 공급원은 현재 미국 젊은이들의 일일 음식 에너지의 거의 25%를 차지하는 가당 음료와 [114]감자 칩입니다.[115] 청량 음료, 과일 음료, 아이스 티와 같은 가당 음료의 섭취는 비만율[116][117] 증가와 대사 증후군 및 제2형 당뇨병의 위험 증가에 기여하는 것으로 여겨집니다.[118] 비타민 D 결핍은 비만과 관련된 질병과 관련이 있습니다.[119]

사회가 에너지 밀도가 높고, 많은 부분을 차지하며, 패스트푸드 식사에 점점 더 의존하게 되면서, 패스트푸드 소비와 비만 사이의 연관성이 더욱 우려되고 있습니다.[120] 미국에서는 1977년에서 1995년 사이에 패스트푸드 식사의 소비가 3배, 이러한 식사로 인한 음식 에너지 섭취가 4배 증가했습니다.[121]

미국과 유럽의 농업 정책과 기술로 인해 식품 가격이 낮아졌습니다. 미국에서는 미국 농장 법안을 통한 옥수수, 콩, 밀, 쌀의 보조금 지급으로 주요 가공 식품 공급원이 과일과 채소에 비해 저렴해졌습니다.[122] 칼로리 계산법과 영양 사실 라벨은 사람들이 얼마나 많은 음식 에너지를 소비하고 있는지에 대한 인식을 포함하여 더 건강한 음식 선택을 하도록 유도하려고 시도합니다.

비만인 사람들은 정상 체중인 사람들에 비해 음식 섭취량을 지속적으로 과소 보고합니다.[123] 이것은 열량계실에서[124] 수행된 사람들의 테스트와 직접 관찰에 의해 뒷받침됩니다.

좌식생활방식

앉아있는 생활 방식은 비만에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있습니다.[52]: 10 전 세계적으로 육체적으로 덜 힘든 일로 큰 변화가 있었고,[125][126][127] 현재 전 세계 인구의 적어도 30%가 불충분한 운동을 하고 있습니다.[126] 이는 주로 기계화된 운송 수단의 사용이 증가하고 가정에서 노동 절약 기술이 더 많이 보급되기 때문입니다.[125][126][127] 어린이의 경우 신체 활동 수준의 감소(특히 보행 및 체육의 양이 크게 감소함)가 있는 것으로 보이며, 이는 안전 문제, 사회적 상호 작용의 변화(이웃 어린이와의 관계 감소 등) 때문일 수 있습니다. 그리고 부적절한 도시 디자인(안전한 신체 활동을 위한 공공 공간이 너무 적음).[128] 활발한 여가 시간 신체 활동의 세계적 추세는 덜 명확합니다. 세계보건기구는 전 세계 사람들이 덜 적극적인 여가 활동을 하고 있다고 지적한 반면, 핀란드의[129] 연구는 증가하고 미국의 연구는 여가 시간 신체 활동이 크게 변하지 않았다는 것을 발견했습니다.[130] 아이들의 신체 활동은 큰 기여를 하지 못할 수도 있습니다.[131]

어린이와 성인 모두 텔레비전 시청 시간과 비만 위험 사이에는 연관성이 있습니다.[132][133][134] 미디어 노출의 증가는 소아 비만의 비율을 증가시키며, 텔레비전 시청 시간에 비례하여 비율이 증가합니다.[135]

유전학

이 섹션을 업데이트해야 합니다. (2021년 7월) |

다른 많은 의학적 조건과 마찬가지로 비만은 유전적 요인과 환경적 요인 사이의 상호 작용의 결과입니다.[137] 식욕과 신진대사를 조절하는 다양한 유전자의 다형성은 음식 에너지가 충분할 때 비만이 되기 쉽습니다. 2006년 현재, 인간 게놈에 있는 이 사이트들 중 41개 이상이 유리한 환경이 존재할 때 비만의 발병과 관련이 있습니다.[138] FTO 유전자(지방량 및 비만 관련 유전자)가 2개인 사람들은 위험 대립 유전자가 없는 사람들에 비해 평균적으로 3-4kg 더 나가고 비만 위험이 1.67배 더 높은 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[139] 유전자로 인한 사람들 간의 BMI 차이는 6%에서 85%[140]까지 조사된 인구에 따라 다릅니다.

비만은 프라더-윌리 증후군, 바르데-비들 증후군, 코헨 증후군, 모모 증후군과 같은 여러 증후군의 주요 특징입니다. (이러한 상태를 배제하기 위해 비증후군성 비만이라는 용어가 사용되기도 합니다.)[141] 조기 발병 중증 비만(10세 이전 발병 및 정상보다 3개 이상 높은 표준 편차에 대한 체질량 지수로 정의됨)을 가진 사람의 경우 7%가 단일 점 DNA 돌연변이를 가지고 있습니다.[142]

특정 유전자보다는 유전 패턴에 초점을 맞춘 연구 결과 비만인 부모 두 명의 자손도 80%가 비만인 것으로 나타났는데, 이와는 대조적으로 정상 체중이었던 부모 두 명의 자손은 10% 미만이었습니다.[143] 같은 환경에 노출된 사람마다 기저 유전자 때문에 비만의 위험이 다릅니다.[144]

알뜰 유전자 가설은 인간 진화 과정에서 식이 부족으로 인해 사람들이 비만에 걸리기 쉽다고 가정합니다. 에너지를 지방으로 저장하여 드물게 풍부한 기간을 활용하는 능력은 식량 가용성이 다양한 시기에 유리할 것이며 지방 비축량이 더 많은 개인은 기근에서 살아남을 가능성이 더 높습니다. 그러나 지방을 저장하는 이러한 경향은 안정적인 식량 공급이 있는 사회에서 부적응적입니다.[medical citation needed] 이 이론은 다양한 비판을 받았으며, 표류 유전자 가설, 알뜰 표현형 가설 등 진화론적 기반의 다른 이론들도 제안되었습니다.[medical citation needed]

기타병

특정 신체적, 정신적 질병과 이를 치료하는 데 사용되는 약학적 물질은 비만의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다. 비만 위험을 높이는 의학적 질병에는 여러 희귀 유전 증후군(위에 나열된)과 일부 선천성 또는 후천성 질환, 갑상선 기능 저하증, 쿠싱 증후군, 성장 호르몬 결핍증,[145] 폭식 장애 및 야간 섭식 증후군과 같은 일부 섭식 장애가 포함됩니다.[2] 그러나 비만은 정신 질환으로 간주되지 않으므로 DSM-IVR에 정신 질환으로 등재되지 않습니다.[146] 과체중과 비만의 위험은 정신과적 장애가 없는 사람보다 정신과적 장애가 있는 환자에서 더 높습니다.[147] 비만과 우울증은 서로 영향을 주고받으며 비만은 임상적 우울증의 위험을 증가시키고, 우울증 또한 비만의 발병 가능성을 높입니다.[3]

약물에 의한 비만

인슐린, 설포닐루레아, 티아졸리딘디온, 비정형 항정신병약, 항우울제, 스테로이드, 특정 항경련제(페닐토인과 발프로에이트), 피조티펜, 일부 호르몬 피임법 등 특정 약물이 체중 증가 또는 신체 구성의 변화를 유발할 수 있습니다.[2]

사회적 결정요인

유전적인 영향은 비만을 이해하는 데 중요하지만, 특정 국가 또는 전 세계에서 볼 수 있는 극적인 증가를 완전히 설명할 수는 없습니다.[148][better source needed] 에너지 소비를 초과하는 에너지 소비가 개인 단위로 체중 증가로 이어진다는 것은 인정되지만, 사회적 규모에서 이 두 요소의 변화 원인에 대해서는 많은 논의가 있습니다. 그 원인에 대해서는 여러 가지 이론이 있지만 대부분은 여러 가지 요인이 복합적으로 작용한다고 생각합니다.

사회 계층과 BMI 사이의 상관관계는 세계적으로 다양합니다. 1989년의 연구는 선진국에서 높은 사회 계층의 여성들이 비만일 가능성이 적다는 것을 발견했습니다. 다른 사회 계층의 남성들 사이에는 유의미한 차이가 나타나지 않았습니다. 개발도상국에서는 여성, 남성 및 높은 사회 계층의 어린이가 비만 비율이 더 높았습니다.[better source needed][149] 2007년에 같은 연구를 반복하면서 같은 관계를 발견했지만, 그 관계는 더 약했습니다. 상관 강도의 감소는 세계화의 영향 때문으로 느껴졌습니다.[150] 선진국에서는 성인 비만 수준과 과체중인 10대 어린이의 비율이 소득 불평등과 상관관계가 있습니다. 미국 주들 사이에서도 비슷한 관계가 보입니다: 더 높은 사회 계층에서도 더 많은 성인들이 더 불평등한 주에서 비만입니다.[151]

BMI와 사회 계층 간의 연관성에 대해 많은 설명이 제시되었습니다. 선진국에서는 부유한 사람들이 더 영양가 있는 음식을 살 수 있고, 날씬함을 유지해야 한다는 사회적 압력을 더 많이 받고 있으며, 신체 건강에 대한 더 큰 기대와 함께 더 많은 기회를 가질 수 있다고 생각됩니다. 미개발 국가에서는 음식을 살 수 있는 능력, 육체 노동으로 인한 높은 에너지 소비, 더 큰 신체 크기를 선호하는 문화적 가치가 관찰된 패턴에 기여하는 것으로 여겨집니다.[150] 사람들이 일생 동안 가지고 있는 체중에 대한 태도도 비만에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 시간에 따른 BMI 변화의 상관관계는 친구, 형제, 배우자 사이에서 발견되었습니다.[152] 스트레스와 낮은 사회적 지위는 비만의 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 보입니다.[151][153][154]

흡연은 개인의 체중에 상당한 영향을 미칩니다. 담배를 끊은 사람들은 10년 동안 평균 4.4kg (9.7lb), 여성은 5.0kg (11.0lb) 증가합니다.[155] 그러나 흡연율의 변화는 전체 비만율에 거의 영향을 미치지 않았습니다.[156]

미국에서, 한 사람이 가지고 있는 아이들의 수는 그들의 비만 위험과 관련이 있습니다. 여성의 위험은 어린이 1명당 7% 증가하는 반면, 남성의 위험은 어린이 1명당 4% 증가합니다.[157] 이것은 의존적인 자녀를 가지는 것이 서양 부모들의 신체 활동을 감소시킨다는 사실에 의해 부분적으로 설명될 수 있습니다.[158]

개발도상국에서 도시화는 비만율을 증가시키는 역할을 하고 있습니다. 중국의 전체 비만율은 5% 미만이지만, 일부 도시에서는 20%[159] 이상의 비만율을 보이고 있습니다. 부분적으로, 이것은 도시 디자인 문제(예를 들어 신체 활동을 위한 부적절한 공공 공간) 때문일 수 있습니다.[128] 자전거를 타거나 걷는 것과 같은 적극적인 교통 수단과는 반대로, 자동차 안에서 보내는 시간은 비만의 위험 증가와 상관관계가 있습니다.[160][161]

초기 생활의 영양실조는 개발도상국의 비만율 증가에 역할을 하는 것으로 여겨집니다.[162] 영양실조 기간 동안 발생하는 내분비 변화는 음식 에너지가 더 많아지면 지방 저장을 촉진할 수 있습니다.[162]

장내세균

감염원이 신진대사에 미치는 영향에 대한 연구는 아직 초기 단계입니다. 장내 세균총은 마른 사람과 비만한 사람 사이에 다른 것으로 나타났습니다. 장내 세균총이 대사 잠재력에 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 징후가 있습니다. 이러한 명백한 변화는 비만에 기여하는 에너지를 수확할 수 있는 더 큰 능력을 부여하는 것으로 여겨집니다. 이러한 차이가 비만의 직접적인 원인인지 결과인지는 아직 명확하게 밝혀지지 않았습니다.[163] 아이들 사이의 항생제 사용은 또한 나중에 비만과 관련이 있습니다.[164][165]

바이러스와 비만 사이의 연관성은 인간과 여러 다른 동물 종에서 발견되었습니다. 이러한 연관성이 비만율 증가에 기여했을 수 있는 양은 아직 결정되지 않았습니다.[166]

기타요인

충분한 수면을 취하지 않는 것도 비만과 관련이 있습니다.[167][168] 어느 쪽이 다른 쪽을 유발하는지는 불분명합니다.[167] 짧은 수면이 체중 증가를 증가시키더라도 이것이 의미 있는 정도인지, 수면을 늘리는 것이 도움이 될지는 불분명합니다.[169]

어떤 사람들은 "오베소겐"이라고 불리는 화학 화합물이 비만에 역할을 할 수 있다고 제안했습니다.

성격의 특정 측면은 비만과 관련이 있습니다.[170] 외로움,[171] 신경증, 충동성, 보상에 대한 민감성은 비만인 사람에게 더 흔하고, 양심과 자기 통제는 비만인 사람에게 덜 흔합니다.[170][172] 이 주제에 대한 대부분의 연구는 설문지 기반이기 때문에 이러한 결과는 성격과 비만의 관계를 과대평가할 수 있습니다. 비만인 사람들은 비만의 사회적 낙인을 인식할 수 있고 설문지 응답은 그에 따라 편향될 수 있습니다.[170] 마찬가지로, 어릴 때 비만인 사람들의 성격은 비만의 위험 요소로 작용하기보다는 비만 낙인에 의해 영향을 받을 수 있습니다.[170]

세계화와 관련하여 무역 자유화는 비만과 관련이 있는 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 1975-2016년 동안 175개국의 데이터를 기반으로 한 연구에 따르면 비만 유병률은 무역 개방도와 양의 상관관계가 있으며 개발도상국에서 그 상관관계가 더 강했습니다.[173]

병태생리학

비만의 발병에는 서로 다르지만 관련된 두 가지 과정이 관련된 것으로 간주됩니다: 지속적인 양의 에너지 균형(에너지 소비를 초과하는 에너지 섭취)과 체중 "설정점"을 증가된 값으로 재설정하는 것입니다.[174] 두 번째 과정은 효과적인 비만 치료법을 찾는 것이 어려웠던 이유를 설명해 줍니다. 이 과정의 근본적인 생물학은 여전히 불확실하지만, 그 메커니즘을 명확히 하기 위한 연구가 시작되고 있습니다.[174]

생물학적 수준에서 비만의 발달과 유지에 관련된 많은 가능한 병태생리학적 메커니즘이 있습니다.[175] 1994년 J. M. Friedman의 실험실에 의해 렙틴 유전자가 발견되기 전까지 이 연구 분야는 거의 접근되지 않았습니다.[176] 렙틴과 그렐린은 말초에서 생성되지만 중추신경계에 작용하여 식욕을 조절합니다. 특히, 그들과 다른 식욕 관련 호르몬들은 음식 섭취와 에너지 소비의 조절의 중심인 뇌의 한 부분인 시상하부에 작용합니다. 시상하부 내에는 식욕을 통합하는 역할을 하는 여러 회로가 있는데, 멜라노코르틴 경로가 가장 잘 알려져 있습니다.[175] 회로는 시상하부의 영역인 아치형 핵으로 시작되며, 이 영역은 각각 뇌의 섭식 및 포만감 중심인 측면 시상하부(LH)와 복막 시상하부(VMH)로 출력됩니다.[177]

아치형 핵에는 두 개의 서로 다른 뉴런 그룹이 포함되어 있습니다.[175] 첫 번째 그룹은 뉴로펩티드 Y(NPY)와 아구티 관련 펩타이드(AgRP)를 공동 발현하며 LH에 대한 자극 입력과 VMH에 대한 억제 입력을 가지고 있습니다. 두 번째 그룹은 프로-오피오멜라노코르틴(POMC)과 코카인 및 암페타민 조절 전사체(CART)를 공동 발현하며 VMH에 대한 자극 입력과 LH에 대한 억제 입력을 가지고 있습니다. 따라서 NPY/AgRP 뉴런은 섭식을 자극하여 포만감을 억제하는 반면, POMC/CART 뉴런은 포만감을 자극하여 섭식을 억제합니다. 두 그룹의 아치형 핵 뉴런은 렙틴에 의해 부분적으로 조절됩니다. 렙틴은 POMC/CART 그룹을 자극하면서 NPY/AgRP 그룹을 억제합니다. 따라서 렙틴 결핍 또는 렙틴 저항성을 통한 렙틴 신호 전달의 결핍은 과식을 초래하고 일부 유전적 및 후천적 형태의 비만을 설명할 수 있습니다.[175]

관리

비만의 주요 치료법은 처방된 식단과 신체 운동을 포함한 생활 습관 개입을 통한 체중 감량으로 구성됩니다.[23][96][178][179] 어떤 식단이 장기적인 체중 감소를 지원할 수 있는지는 불분명하며, 저칼로리 식단의 효과가 논란이 되고 있지만,[180] 장기간에 걸쳐 칼로리 소비를 줄이거나 신체 운동을 증가시키는 생활 방식의 변화도 시간이 지남에 따라 체중이 천천히 회복됨에도 불구하고 지속적인 체중 감소를 일으키는 경향이 있습니다.[23][180][181][182] 국가 체중 관리 등록부 참가자의 87%가 10년 동안 10%의 체중 감량을 유지할 수 있었지만 [183][clarification needed]장기적인 체중 감량 유지를 위한 가장 적절한 식이 요법은 아직 알려지지 않았습니다.[184] 미국에서는 식이 변화와 운동을 병행하는 집중적인 행동 중재가 권장됩니다.[23][178][185] 간헐적 단식은 지속적인 에너지 제한에 비해 체중 감소의 추가적인 이점이 없습니다.[184] 어떤 종류의 다이어트를 하든지 간에, 고수는 체중 감량 성공에 더 중요한 요소입니다.[184][186]

몇 가지 저칼로리 식단이 효과적입니다.[23] 단기적으로 저탄수화물 식단은 체중 감량을 위해 저지방 식단보다 더 잘 보입니다.[187] 그러나 장기적으로는 모든 유형의 저탄수화물 및 저지방 식단이 동등하게 유익해 보입니다.[187][188] 다양한 식단과 관련된 심장 질환과 당뇨병 위험은 유사한 것으로 보입니다.[189] 비만인 사람들 사이에서 지중해 식단을 장려하면 심장병의 위험이 낮아질 수 있습니다.[187] 단 음료 섭취 감소도 체중 감소와 관련이 있습니다.[187] 라이프 스타일 변화에 따른 장기적인 체중 감량 유지 성공률은 2~20%[190]로 낮습니다. 식습관과 생활습관 변화는 임신 중 과도한 체중 증가를 제한하고 산모와 아이 모두의 결과를 개선하는 데 효과적입니다.[191] 비만이면서 심장질환의 다른 위험인자를 가지고 있는 사람들에게는 집중적인 행동상담이 권장됩니다.[192]

보건정책

비만은 유병률, 비용 및 건강 영향으로 인해 복잡한 공중 보건 및 정책 문제입니다.[193] 따라서 이를 관리하려면 지역 사회, 지방 당국 및 정부의 광범위한 사회적 맥락과 노력의 변화가 필요합니다.[185] 공중 보건 노력은 인구의 비만 유병률 증가에 책임이 있는 환경 요인을 이해하고 수정하고자 합니다. 솔루션은 음식 에너지 과잉 소비를 유발하고 신체 활동을 억제하는 요인을 변화시키는 것을 살펴봅니다. 이러한 노력에는 학교에서 연방정부가 지원하는 급식 프로그램, 어린이에 대한 직접 정크 푸드 마케팅 제한,[194] 학교에서 설탕이 첨가된 음료에 대한 접근 감소 등이 포함됩니다.[195] 세계보건기구는 설탕이 든 음료에 세금을 부과할 것을 권장합니다.[196] 도시 환경을 조성할 때 공원 접근성을 높이고 보행로를 개발하기 위해 노력해 왔습니다.[197]

매스 미디어 캠페인은 비만에 영향을 미치는 행동을 변화시키는 데 효과가 제한적인 것으로 보이지만 신체 활동과 식단에 대한 지식과 인식을 증가시켜 장기적으로 변화를 가져올 수 있습니다. 캠페인은 또한 앉거나 누워있는 시간을 줄이고 신체적으로 활동하려는 의도에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[198][199] 메뉴에 대한 에너지 정보가 포함된 영양 라벨은 레스토랑에서 식사하는 동안 에너지 섭취를 줄이는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[200] 일부에서는 초가공 식품에 대한 정책을 요구합니다.[201][202]

의학적 개입

약

1930년대 비만 관리를 위한 의약품이 도입된 이후 많은 화합물이 시도되었습니다. 그들 중 대부분은 소량씩 체중을 줄이고, 그들 중 몇몇은 부작용 때문에 더 이상 비만을 위해 판매되지 않습니다. 1964년에서 2009년 사이에 시장에서 철수한 25개의 항비만제 중 23개가 뇌의 화학적 신경전달물질의 기능을 변화시키는 작용을 했습니다. 금단에 이르게 된 이 약들의 가장 흔한 부작용은 정신적 장애, 심장 부작용, 약물 남용 또는 약물 의존이었습니다. 사망자는 7개 제품과 관련이 있는 것으로 알려졌습니다.[203]

장기 사용에 유익한 5가지 약물은 오르리스타트, 로르카세린, 리라글루타이드, 펜터민-토피라메이트, 날트렉손-부프로피온입니다.[204] 그들은 1년 후 위약에 비해 3.0에서 6.7 kg (6.6-14.8 lbs)의 체중 감소를 초래합니다.[204] Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexone-buppropion은 미국과 유럽 모두에서 구입할 수 있으며, 펜터민-토피라메이트는 미국에서만 구입할 수 있습니다.[205] 유럽 규제 당국은 부분적으로 심장 판막 문제와 심장 판막 문제 및 보다 일반적인 심장 및 혈관 문제가 펜터민-토피라메이트와 연관되어 있기 때문에 로르카세린 및 펜터민-토피라메이트를 거부했습니다.[205] Lorcaserin은 미국에서 판매되다가 암과의 연관성 때문에 2020년에 시장에서 퇴출되었습니다.[206] Orlistat 사용은 높은 비율의 위장 부작용과[207] 관련이 있으며 신장에 미치는 부정적인 영향에 대한 우려가 제기되었습니다.[208] 이러한 약물이 심혈관 질환이나 사망과 같은 비만의 장기 합병증에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 정보는 없지만,[5] 리라글루타이드는 제2형 당뇨병에 사용될 때 심혈관 사건을 감소시킵니다.[209]

2019년 체계적인 검토는 비만 성인에서 다양한 용량의 플루옥세틴(60mg/d, 40mg/d, 20mg/d, 10mg/d)의 체중에 미치는 영향을 비교했습니다.[210] 위약과 비교했을 때, 플루옥세틴의 모든 용량은 체중 감소에 기여하지만 치료 기간 동안 어지러움, 졸음, 피로, 불면증 및 메스꺼움과 같은 부작용을 경험할 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 나타났습니다. 그러나 이러한 결론은 확실성이 낮은 증거에서 나온 것입니다.[210] 같은 리뷰에서 저자들은 플루옥세틴이 비만 성인의 체중에 미치는 영향을 다른 비만치료제인 오메가3 겔과 비교하고 치료를 받지 않은 경우 근거의 질이 떨어져 결정적인 결과에 도달하지 못했습니다.[210]

조현병 치료를 위한 항정신병 약물 중 클로자핀이 가장 효과적이지만 대사증후군을 유발할 위험도 가장 높아 비만이 주를 이룹니다. 클로자핀 때문에 체중이 증가하는 사람들의 경우, 메트포르민을 복용하면 대사증후군의 다섯 가지 구성 요소 중 세 가지인 허리둘레, 공복 포도당, 공복 중성지방이 개선될 수 있다고 합니다.[211]

수술.

비만에 가장 효과적인 치료법은 비만치료 수술입니다.[6][23] 시술의 종류로는 복강경 조절식 위 밴딩, Roux-en-Y 위 우회술, 수직 소매 위 절제술, 담췌관 전환술 등이 있습니다.[204] 심각한 비만에 대한 수술은 장기간의 체중 감소, 비만 관련 상태의 개선,[212] 전체 사망률 감소와 관련이 있지만, 대사 건강의 개선은 수술이 아닌 체중 감소에서 비롯됩니다.[213] 한 연구에 따르면 10년 동안 14%에서 25% 사이의 체중 감소가 있었고 (수행된 절차 유형에 따라) 표준 체중 감소 측정과 비교했을 때 모든 원인 사망률이 29% 감소했습니다.[214] 합병증은 약 17%에서 발생하고 7%에서 재수술이 필요합니다.[212]

역학

기술적인 문제로 인해 그래프를 사용할 수 없습니다. Fabricator 및 MediaWiki.org 에 대한 자세한 정보가 있습니다. |

원본 데이터를 보거나 편집합니다.

초기 역사적 시기에는 비만이 드물었고 이미 건강의 문제로 인식되었지만 소수의 엘리트만이 달성할 수 있었습니다. 그러나 근대 초기에 번영이 증가함에 따라, 그것은 점점 더 많은 인구 집단에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[215] 1970년대 이전까지 비만은 가장 부유한 국가에서도 비교적 드문 질환이었고, 비만이 존재했을 때 부유한 국가에서 발생하는 경향이 있었습니다. 그리고 나서, 사건들의 융합이 인간의 상태를 바꾸기 시작했습니다. 제1세계 국가의 인구 평균 BMI가 증가하기 시작했고, 그 결과 과체중과 비만의 비율이 급격히 증가했습니다.[216]

1997년 WHO는 비만을 세계적인 유행병으로 공식 인정했습니다.[114] 세계보건기구는 2008년 기준으로 최소 5억 명의 성인(10% 이상)이 비만인 것으로 추정하고 있으며, 여성의 비율이 남성보다 높습니다.[217] 전 세계적인 비만 유병률은 1980년에서 2014년 사이에 두 배 이상 증가했습니다. 2014년에는 6억 명 이상의 성인이 비만이었으며, 이는 전 세계 성인 인구의 약 13%에 해당합니다.[218] 2015-2016년 현재 미국에서 영향을 받는 성인의 비율은 전체적으로 약 39.6%(남성 37.9%, 여성 41.1%)입니다.[219] 2000년 세계보건기구(WHO)는 건강 악화의 가장 중요한 원인 중 하나로 과체중과 비만이 영양실조와 전염병과 같은 더 전통적인 공중 보건 문제를 대체하고 있다고 밝혔습니다.[220]

비만율도 최소 50세[52]: 5 또는 60세까지 연령이 증가함에 따라 증가하며 미국, 호주, 캐나다의 심각한 비만율은 전체 비만율보다 빠르게 증가하고 있습니다.[31][221][222] OECD는 적어도 2030년까지 비만율이 증가할 것으로 예상했으며, 특히 미국, 멕시코, 영국에서 비만율이 각각 47%, 39%, 35%에 이를 것으로 예상했습니다.[223]

한때 고소득 국가들만의 문제로 여겨졌던 비만율은 전 세계적으로 증가하고 있으며 선진국과 개발도상국 모두에게 영향을 미치고 있습니다.[224] 이러한 증가는 도시 환경에서 가장 극적으로 느껴졌습니다.[217]

성별과 성별에 따른 차이도 비만의 유병률에 영향을 미칩니다. 전 세계적으로 남성보다 비만한 여성이 더 많지만 비만을 측정하는 방법에 따라 그 수가 다릅니다.[225][226]

역사

어원

비만은 라틴어 obesitas에서 왔는데, 이는 "통통통, 지방, 혹은 통통한"을 의미합니다. ē소스는 에데르(먹는 것)의 과거의 한 부분으로 ob(오버)이 추가됩니다. 옥스포드 영어 사전은 1611년 Randle Cotgrave에 의해 처음으로 사용된 것을 기록하고 있습니다.[228]

역사적 태도

고대 그리스 의학은 비만을 의학적 장애로 인식하고 고대 이집트인들도 같은 방식으로 보았다고 기록하고 있습니다.[215] 히포크라테스는 "강압은 질병 그 자체일 뿐만 아니라 다른 사람들의 전조이다"라고 썼습니다.[2] 인도의 외과의사 Sushruta (기원전 6세기)는 비만을 당뇨병과 심장 장애와 연관시켰습니다.[230] 그는 그것과 그것의 부작용을 치료하는 데 도움이 되는 신체적인 작업을 추천했습니다.[230] 인류 역사의 대부분 동안 인류는 식량 부족으로 어려움을 겪었습니다.[231] 그러므로 비만은 역사적으로 부와 번영의 상징으로 여겨져 왔습니다. 고대 동아시아 문명의 고위 관리들 사이에서 흔했습니다.[232] 17세기 영국 의학 작가 토비아스 베너(Tobias Venner)는 출판된 영어 책에서 이 용어를 사회적 질병으로 처음 언급한 사람 중 한 명으로 알려져 있습니다.[215][233]

산업혁명이 시작되면서 국가의 군사력과 경제력은 군인과 노동자의 신체 크기와 힘에 모두 의존하고 있음을 알게 되었습니다.[114] 평균 체질량 지수를 현재 저체중으로 간주되는 것에서 현재 정상 범위로 증가시킨 것이 산업화 사회의 발전에 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[114] 따라서 키와 몸무게는 모두 19세기 선진국에서 증가했습니다. 20세기 동안 인구가 키에 대한 유전적 잠재력에 도달함에 따라 체중이 키보다 훨씬 더 많이 증가하기 시작하여 비만이 발생했습니다.[114] 1950년대에는 선진국에서 부의 증가가 어린이 사망률을 감소시켰지만 체중이 증가하면서 심장과 신장 질환이 더 흔해졌습니다.[114][234] 이 기간 동안 보험 회사는 체중과 기대 수명의 연관성과 비만인의 보험료 인상을 깨달았습니다.[2]

역사를 통틀어 많은 문화권에서 비만을 성격 결함의 결과로 간주해 왔습니다. 고대 그리스 코미디에서 비만인 캐릭터는 식탐이 많고 조롱의 대상이었습니다. 기독교 시대에 음식은 게으름과 정욕의 죄를 짓는 관문으로 여겨졌습니다.[21] 현대 서구 문화에서 과도한 체중은 매력적이지 않은 것으로 간주되는 경우가 많으며 비만은 일반적으로 다양한 부정적인 고정관념과 관련이 있습니다. 모든 연령대의 사람들은 사회적인 오명에 직면할 수 있고 괴롭힘을 당하거나 동료들에게 기피될 수 있습니다.[235]

건강한 체중에 대한 서구 사회의 대중의 인식은 이상적이라고 여겨지는 체중에 대한 인식과 다르며, 20세기 초부터 둘 다 변화했습니다. 이상적인 것으로 여겨지는 비중은 1920년대 이후 더 낮아졌습니다. 이는 1922년부터 1999년까지 미스 아메리카 미인대회 우승자의 평균 신장이 2% 증가한 반면, 평균 체중은 12%[236] 감소한 것에서 알 수 있습니다. 반면, 건강 체중에 대한 사람들의 관점은 반대 방향으로 바뀌었습니다. 영국에서 사람들이 자신이 과체중이라고 생각하는 체중은 1999년보다 2007년에 현저하게 높았습니다.[237] 이러한 변화는 지방의 비율이 증가함에 따라 여분의 체지방이 정상으로 받아들여지기 때문인 것으로 생각됩니다.[237]

비만은 여전히 아프리카의 많은 지역에서 부와 행복의 표시로 여겨집니다. 이것은 HIV 전염병이 시작된 이후 특히 일반화되었습니다.[2]

예술.

20,000년에서 35,000년 전의 인체에 대한 최초의 조각적 표현은 비만한 여성을 묘사합니다. 어떤 사람들은 금성의 형상이 다산을 강조하는 경향 때문이라고 생각하지만, 다른 사람들은 그것들이 당대 사람들의 "살이 찌는 것"을 나타낸다고 생각합니다.[21] 그러나 코풀런스는 그리스와 로마 예술 모두에 존재하지 않으며, 아마도 절제에 관한 그들의 이상과 일치합니다. 이것은 기독교 유럽 역사의 많은 부분에서 계속되었고, 사회경제적 지위가 낮은 사람들만 비만으로 묘사되었습니다.[21]

르네상스 시대 동안 일부 상류층은 영국의 헨리 8세와 알레산드로 달 보로의 초상화에서 볼 수 있듯이 큰 덩치를 과시하기 시작했습니다.[21] 루벤스 (1577–1640)는 정기적으로 그의 사진에서 육중한 여성을 묘사했는데, 이것은 루벤스케라는 용어에서 유래되었습니다. 그러나 이 여성들은 여전히 출산력과 관계가 있는 "모래시계" 모양을 유지했습니다.[238] 19세기 동안 서구 세계에서 비만에 대한 관점이 바뀌었습니다. 수세기 동안 비만이 부와 사회적 지위의 동의어였던 후, 날씬함이 바람직한 기준으로 여겨지기 시작했습니다.[21] 예술가 조지 크룩생크는 그의 1819년 판화인 벨 동맹 혹은 블랙번의 여성 개혁가!!!에서 블랙번의 여성 개혁가들의 작품을 비판했고 그들을 여성스럽지 않게 묘사하기 위한 수단으로 뚱뚱함을 사용했습니다.[239]

사회와 문화

경제적 영향

건강에 미치는 영향 외에도 비만은 고용의[240]: 29 [241] 불리함과 사업 비용 증가를 포함하여 많은 문제를 야기합니다. 이러한 효과는 개인에서 기업, 정부에 이르기까지 모든 사회 수준에서 느껴집니다.

2005년 미국의 비만으로 인한 의료 비용은 전체 의료 비용의 20.6%인 1,902억 달러로 추정된 반면,[242][243][244] 캐나다의 비만 비용은 1997년 20억 캐나다 달러(총 의료 비용의 2.4%)로 추정되었습니다.[96] 2005년 호주의 과체중과 비만으로 인한 연간 총 직접 비용은 210억 호주 달러였습니다. 과체중과 비만인 호주인들도 356억 호주달러의 정부 보조금을 받았습니다.[245] 다이어트 제품에 대한 연간 지출의 예상 범위는 미국에서만 400억 달러에서 1,000억 달러입니다.[246]

2019년 Lancet 비만 위원회는 WHO 담배 규제 기본 협약을 모델로 한 글로벌 조약을 요구했으며, 각국은 비만과 영양실조 문제를 해결하고 식품 산업을 정책 개발에서 명시적으로 제외했습니다. 그들은 비만으로 인한 전 세계적인 비용을 연간 2조 달러, 즉 세계 GDP의 약 2.8%로 추정하고 있습니다.[247]

비만 예방 프로그램은 비만과 관련된 질병을 치료하는 비용을 줄이는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 그러나 사람들이 오래 살수록 의료 비용이 더 많이 발생합니다. 따라서 연구원들은 비만을 줄이는 것이 대중의 건강을 증진시킬 수는 있지만 전반적인 건강 지출을 감소시킬 가능성은 낮다고 결론짓습니다.[248] 설탕 음료세와 같은 죄악세는 식생활과 소비자 습관을 억제하고 경제적 통행료를 상쇄하기 위한 노력으로 세계적으로 특정 국가에서 시행되었습니다.

비만은 사회적 낙인과 취업에서의 불이익으로 이어질 수 있습니다.[240]: 29 비만 근로자는 정상 체중에 비해 평균적으로 결근률이 높고 장애 휴가를 더 많이 받아 고용주의 비용이 증가하고 생산성이 떨어집니다.[250] 듀크 대학 직원들을 조사한 연구에 따르면 BMI가 40kg/m2 이상인 사람들은 BMI가 18.5–24.9kg/m인2 사람들보다 두 배나 더 많은 근로자 보상 청구를 한 것으로 나타났습니다. 그들은 또한 손실된 근무 일수가 12배 이상이었습니다. 이 그룹에서 가장 흔한 부상은 낙상과 리프팅으로 인해 하지, 손목 또는 손, 허리에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[251] 앨라배마 주 공무원 보험 위원회는 비만 근로자들이 체중을 줄이고 건강을 개선하기 위한 조치를 취하지 않으면 무료가 될 건강 보험에 한 달에 25달러를 부과하는 논란이 많은 계획을 승인했습니다. 이러한 조치는 2010년 1월부터 시작되어 BMI가 35kg/m를2 초과하고 1년이 지나도록 건강을 개선하지 못하는 주 근로자에게 적용됩니다.[252]

비만인 사람은 직장에 채용될 가능성이 낮고 승진할 가능성이 낮다는 연구 결과도 있습니다.[235] 비만인 사람들은 또한 동등한 직업에 대해 비만이 아닌 사람들보다 더 적은 임금을 받습니다. 비만 여성은 평균 6%를 덜 벌고 비만 남성은 3%를 덜 받습니다.[240]: 30

항공, 의료 및 식품 산업과 같은 특정 산업에는 특별한 우려가 있습니다. 증가하는 비만율로 인해 항공사들은 더 높은 연료 비용과 좌석 폭을 늘려야 하는 압력에 직면해 있습니다.[253] 2000년, 비만 승객들의 추가 체중으로 인해 항공사들은 2억 7,500만 달러의 비용을 지불했습니다.[254] 의료 산업은 특수 리프팅 장비와 비만 구급차를 포함한 중증 비만 환자를 처리하기 위한 특수 시설에 투자해야 했습니다.[255] 레스토랑이 비만을 유발한다고 비난하는 소송으로 인해 레스토랑 비용이 증가합니다.[256] 2005년 미국 의회는 비만과 관련하여 식품 산업에 대한 민사 소송을 방지하기 위한 법안을 논의했지만 법이 되지 않았습니다.[256]

2013년 미국의사협회가 비만을 만성질환으로 분류함에 [24]따라 건강보험회사가 비만치료, 상담, 수술비 등을 부담할 가능성이 높아졌다고 생각되고, 그리고 지방 치료제나 유전자 치료제의 연구 개발 비용은 보험사들이 비용을 보조하는 데 도움이 된다면 더 저렴해질 것입니다.[257] 그러나 AMA 분류는 법적 구속력이 없기 때문에 건강 보험사는 여전히 치료 또는 시술에 대한 보장을 거부할 권리가 있습니다.[257]

2014년, 유럽 사법 재판소는 병적 비만이 장애라고 판결했습니다. 법원은 직원의 비만으로 인해 "다른 근로자와 동등하게 직업 생활에 그 사람의 완전하고 효과적인 참여"가 불가능한 경우 장애로 간주되며 그러한 이유로 해고하는 것은 차별적이라고 말했습니다.[258]

저소득 국가에서는 비만이 부의 신호가 될 수 있습니다. 2023년 실험 연구에 따르면 우간다의 비만한 사람들은 신용에 접근할 가능성이 더 높았습니다.[259]

사이즈수용

지방 수용 운동의 주요 목표는 과체중과 비만인 사람들에 대한 차별을 줄이는 것입니다.[261][262] 그러나 운동의 일부는 비만과 부정적인 건강 결과 사이의 확립된 관계에 도전하려고 시도하고 있습니다.[263]

비만의 수용을 촉진하는 많은 조직이 존재합니다. 그들은 20세기 후반에 두각을 나타냈습니다.[264] 미국에 본부를 둔 전미지방수용협회(NAAFA)는 1969년 결성돼 규모 차별 종식을 위한 시민권 단체로 자처하고 있습니다.[265]

국제 규모 수용 협회(ISAA)는 1997년에 설립된 비정부 기구입니다. 글로벌 지향점을 더 많이 가지고 있으며 크기 수용을 촉진하고 체중 기반 차별을 종식시키는 데 도움이 되는 임무를 설명합니다.[266] 이들 단체는 종종 미국 장애인법(ADA)에 따라 비만을 장애로 인정해야 한다고 주장합니다. 그러나 미국의 법률 체계는 잠재적인 공중 보건 비용이 비만을 보장하기 위해 이 차별 금지법을 연장함으로써 얻을 수 있는 혜택을 초과한다고 결정했습니다.[263]

산업계가 연구에 미치는 영향

2015년 뉴욕 타임즈는 2014년에 설립된 비영리 단체인 글로벌 에너지 밸런스 네트워크(Global Energy Balance Network)에 비만을 피하고 건강하기 위해 칼로리 섭취를 줄이기보다는 운동을 늘리는 데 집중해야 한다고 주장하는 기사를 실었습니다. 이 단체는 코카콜라 컴퍼니로부터 최소 150만 달러의 자금을 지원받아 설립되었으며, 이 회사는 두 명의 설립 과학자 그레고리 A에게 400만 달러의 연구 자금을 제공했습니다. 2008년부터 핸드와 스티븐 N. 블레어.[267][268]

보고서

많은 기관들이 비만과 관련된 보고서를 발표했습니다. 1998년, "성인의 과체중 및 비만의 식별, 평가 및 치료에 관한 임상 지침"이라는 제목의 첫 번째 미국 연방 지침이 발표되었습니다. 증거 보고서".[269] 2006년, 현재 비만 캐나다로 알려진 캐나다 비만 네트워크는 "성인과 어린이의 비만 관리 및 예방에 관한 캐나다 임상 진료 지침(CPG)"을 발표했습니다. 이것은 성인과 어린이의 과체중 및 비만 관리 및 예방을 다루기 위한 포괄적인 증거 기반 지침입니다.[96]

2004년, 영국 왕립 의사 대학, 공중 보건 학부, 영국 왕립 소아과 및 아동 보건 대학은 영국에서 증가하는 비만 문제를 강조하는 보고서 "Storing Up Problems"를 발표했습니다.[270] 같은 해, 하원 건강 선정 위원회는 영국에서 비만이 건강과 사회에 미치는 영향과 이 문제에 대한 가능한 접근법에 대한 "지금까지 수행된 가장 포괄적인 조사[...]"를 발표했습니다.[271] 2006년 미국 국립보건임상우수연구원(NICE)은 비만의 진단 및 관리에 관한 가이드라인을 발표하고 지방의회 등 비의료기관에 대한 정책적 시사점을 제시하였습니다.[272] 2007년 데릭 완리스(Derek Wanless)가 킹스 펀드(King's Fund)를 위해 작성한 보고서는 비만은 추가 조치가 취해지지 않으면 국가 보건 서비스(National Health Service)를 재정적으로 약화시킬 수 있는 능력이 있다고 경고했습니다.[273] 2022년 국립보건의료연구원(NIHR)은 지방 당국이 비만을 줄이기 위해 무엇을 할 수 있는지에 대한 포괄적인 연구 검토를 발표했습니다.[199]

비만 정책 조치(OPA) 프레임워크는 조치를 업스트림 정책, 미드스트림 정책 및 다운스트림 정책으로 나눕니다. 업스트림 정책은 사회 변화와 관련이 있는 반면, 미드스트림 정책은 개인 수준에서 비만의 원인이 되는 것으로 여겨지는 행동을 바꾸려고 노력하는 반면, 다운스트림 정책은 현재 비만인 사람들을 치료합니다.[274]

소아비만

건강한 BMI 범위는 아이의 나이와 성별에 따라 다릅니다. 어린이와 청소년의 비만은 95번째 백분위수보다 큰 BMI로 정의됩니다.[275] 이 백분위수들이 기준으로 삼는 참조 데이터는 1963년부터 1994년까지의 것이므로 최근 비만율의 증가에 영향을 받지 않습니다.[276] 아동 비만은 21세기에 유행성 비율에 도달했으며 선진국과 개발도상국 모두에서 증가하고 있습니다. 캐나다 소년의 비만율은 1980년대 11%에서 1990년대 30% 이상으로 증가했으며, 같은 기간 동안 브라질 어린이의 비만율은 4%에서 14%로 증가했습니다.[277] 영국에서는 1989년에 비해 2005년에 비만 아동이 60% 더 많았습니다.[278] 미국에서 과체중 및 비만 아동의 비율은 2008년 16%로 증가했으며, 이는 지난 30년 동안 300% 증가한 것입니다.[279]

성인의 비만과 마찬가지로, 많은 요인들이 소아 비만의 증가율에 기여합니다. 식생활의 변화와 신체활동의 감소는 최근 아동비만 발생률의 증가에 가장 중요한 두 가지 원인으로 여겨지고 있습니다.[280] 어린이들에게 건강에 좋지 않은 음식을 광고하는 것도 그들의 제품 소비를 증가시키기 때문에 기여합니다.[281] 생후 6개월 동안의 항생제는 7세에서 12세 사이의 과도한 체중과 관련이 있습니다.[165] 소아비만은 성인기까지 지속되는 경우가 많고 수많은 만성질환과 연관이 있기 때문에 비만인 어린이는 고혈압, 당뇨, 고지혈증, 지방간질환 등의 검사를 많이 받습니다.[96]

어린이에게 사용되는 치료법은 주로 생활습관 중재와 행동 기법이지만, 어린이의 활동성을 높이려는 노력은 거의 성공하지 못했습니다.[282] 미국에서는 의약품이 이 연령대에서 사용할 수 있도록 FDA 승인을 받지 않았습니다.[277] 일차 진료에 대한 간략한 체중 관리 개입(예: 의사 또는 간호사가 제공)은 소아 과체중 또는 비만을 줄이는 데 약간의 긍정적인 효과만 있습니다.[283] 식이 및 신체 활동의 변화를 포함하는 다중 구성 요소 행동 변화 개입은 6세에서 11세 사이의 어린이에서 단기적으로 BMI를 감소시킬 수 있지만 이점은 적고 증거의 질은 낮습니다.[284]

다른 동물들

애완동물의 비만은 많은 나라에서 흔합니다. 미국에서는 개의 23~41%가 과체중이고, 약 5.1%가 비만입니다.[285] 고양이의 비만율은 6.4%[285]로 약간 높았습니다. 호주에서는 수의학 환경에서 개들의 비만율이 7.6%[286]로 밝혀졌습니다. 개의 비만 위험은 주인의 비만 여부와 관련이 있지만 고양이와 주인 사이에는 비슷한 상관관계가 없습니다.[287]

참고 항목

참고문헌

인용문

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Obesity and overweight Fact sheet N°311". WHO. January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Haslam DW, James WP (October 2005). "Obesity". Lancet (Review). 366 (9492): 1197–1209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. PMID 16198769. S2CID 208791491.

- ^ a b Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG (March 2010). "Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (3): 220–9. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. PMID 20194822.

- ^ a b Yazdi FT, Clee SM, Meyre D (2015). "Obesity genetics in mouse and human: back and forth, and back again". PeerJ. 3: e856. doi:10.7717/peerj.856. PMC 4375971. PMID 25825681.

- ^ a b c Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA (January 2014). "Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review". JAMA (Review). 311 (1): 74–86. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281361. PMC 3928674. PMID 24231879.

- ^ a b c Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK (August 2014). "Surgery for weight loss in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Meta-analysis, Review). 2014 (8): CD003641. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. PMC 9028049. PMID 25105982.

- ^ Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, et al. (GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators) (July 2017). "Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. PMC 5477817. PMID 28604169.

- ^ Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. (May 2021). "Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 143 (21): e984–e1010. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973. PMC 8493650. PMID 33882682.

- ^ CDC (21 March 2022). "Causes and Consequences of Childhood Obesity". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Policy Finder". American Medical Association (AMA). Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b Kanazawa M, Yoshiike N, Osaka T, Numba Y, Zimmet P, Inoue S (2005). "Criteria and Classification of Obesity in Japan and Asia-Oceania". Nutrition and Fitness: Obesity, the Metabolic Syndrome, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer. World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics. Vol. 94. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1159/000088200. ISBN 978-3-8055-7944-5. PMID 16145245. S2CID 19963495.

- ^ "Obesity - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Chiolero A (October 2018). "Why causality, and not prediction, should guide obesity prevention policy". The Lancet. Public Health. 3 (10): e461–e462. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30158-0. PMID 30177480.

- ^ Kassotis CD, Vandenberg LN, Demeneix BA, Porta M, Slama R, Trasande L (August 2020). "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: economic, regulatory, and policy implications". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 8 (8): 719–730. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30128-5. PMC 7437819. PMID 32707119.

- ^ a b Bleich S, Cutler D, Murray C, Adams A (2008). "Why is the developed world obese?". Annual Review of Public Health (Research Support). 29: 273–295. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090954. PMID 18173389.

- ^ Strohacker K, Carpenter KC, McFarlin BK (15 July 2009). "Consequences of Weight Cycling: An Increase in Disease Risk?". International Journal of Exercise Science. 2 (3): 191–201. PMC 4241770. PMID 25429313.

- ^ Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Alvarez EE, Sendra-Gutiérrez JM, González-Enríquez J (July 2008). "Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis". Obesity Surgery. 18 (7): 841–846. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9331-8. PMID 18459025. S2CID 10220216.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Mental Health (2 ed.). Academic Press. 2015. p. 158. ISBN 9780123977533.

- ^ NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) (29 February 2024). "Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults". The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2.

- ^ "One in eight people are now living with obesity". www.who.int. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Woodhouse R (2008). Obesity in art: a brief overview. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Vol. 36. pp. 271–86. doi:10.1159/000115370. ISBN 978-3-8055-8429-6. PMID 18230908.

- ^ "The implications of defining obesity as a disease: a report from the Association for the Study of Obesity 2021 annual conference - eClinicalMedicine".

- ^ a b c d e f Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. (June 2014). "2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society". Circulation. 129 (25 Suppl 2): S102–S138. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. PMC 5819889. PMID 24222017.

- ^ a b Pollack A (18 June 2013). "A.M.A. Recognizes Obesity as a Disease". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013.

- ^ Weinstock M (21 June 2013). "The Facts About Obesity". H&HN. American Hospital Association. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ The SuRF Report 2 (PDF). The Surveillance of Risk Factors Report Series (SuRF). World Health Organization. 2005. p. 22.

- ^ a b c d "Obesity and overweight". World Health Organization. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "BMI-for-age (5–19 years)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ a b Bei-Fan Z (December 2002). "Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults: study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults". Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 11 (Suppl 8): S685–93. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.s8.9.x.Bei-Fan Z (December 2002). "Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults: study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults". Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 11 (Suppl 8): S685–93. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.s8.9.x.원래 인쇄된 것은 다음과 같습니다.

- ^ a b Sturm R (July 2007). "Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000–2005". Public Health. 121 (7): 492–6. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.006. PMC 2864630. PMID 17399752.

- ^ Seidell JC, Flegal KM (1997). "Assessing obesity: classification and epidemiology" (PDF). British Medical Bulletin. 53 (2): 238–252. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011611. PMID 9246834.

- ^ "Regular Exercise: How It Can Boost Your Health".

- ^ "NFL Players Not at Increased Heart Risk: Study finds they showed no more signs of cardiovascular trouble than general male population".

- ^ a b Yamauchi T, Abe T, Midorikawa T, Kondo M (2004). "Body composition and resting metabolic rate of Japanese college Sumo wrestlers and non-athlete students: are Sumo wrestlers obese?". Anthropological Science. 112 (2): 179–185. doi:10.1537/ase.040210.

- ^ a b Blüher M (May 2019). "Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 15 (5): 288–298. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8. PMID 30814686. S2CID 71146382.

- ^ a b c d Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R (March 2009). "Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies". Lancet. 373 (9669): 1083–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. PMC 2662372. PMID 19299006.

- ^ Barness LA, Opitz JM, Gilbert-Barness E (December 2007). "Obesity: genetic, molecular, and environmental aspects". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 143A (24): 3016–34. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32035. PMID 18000969. S2CID 7205587.

- ^ Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL (March 2004). "Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000". JAMA. 291 (10): 1238–45. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. PMID 15010446. S2CID 14589790.

- ^ Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, Stevens J, VanItallie TB (October 1999). "Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States". JAMA. 282 (16): 1530–8. doi:10.1001/jama.282.16.1530. PMID 10546692.

- ^ Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, Norat T, Janszky I, Tonstad S, Romundstad P, Vatten LJ (May 2016). "BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants". BMJ. 353: i2156. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2156. PMC 4856854. PMID 27146380.

- ^ a b Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju S, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. (The Global BMI Mortality Collaboration) (August 2016). "Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents". Lancet. 388 (10046): 776–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1. PMC 4995441. PMID 27423262.

- ^ Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW (October 1999). "Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (15): 1097–105. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910073411501. PMID 10511607.

- ^ Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K, et al. (November 2008). "General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (20): 2105–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. PMID 19005195. S2CID 23967973.

- ^ Carmienke S, Freitag MH, Pischon T, Schlattmann P, Fankhaenel T, Goebel H, Gensichen J (June 2013). "General and abdominal obesity parameters and their combination in relation to mortality: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 67 (6): 573–85. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2013.61. PMID 23511854.

- ^ WHO Expert Consultation (January 2004). "Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies". Lancet. 363 (9403): 157–63. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15268-3. PMID 14726171. S2CID 15637224.

- ^ "Obesity". www.who.int. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L (January 2003). "Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 138 (1): 24–32. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008. hdl:1765/10043. PMID 12513041. S2CID 8120329.

- ^ Grundy SM (June 2004). "Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (6): 2595–600. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0372. PMID 15181029. S2CID 7453798.

- ^ "Obesity linked to long Covid-19, RAK hospital study finds". Khaleej Times. 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, Rosenblum HG, Belay B, Ko JY, et al. (July 2021). "Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020 – March 2021". Preventing Chronic Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18: E66. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210123. PMC 8269743. PMID 34197283.

- ^ a b c Seidell JC (2005). "Epidemiology – definition and classification of obesity". In Kopelman PG, Caterson ID, Stock MJ, Dietz WH (eds.). Clinical obesity in adults and children: In Adults and Children. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-1-4051-1672-5.

- ^ a b Bray GA (June 2004). "Medical consequences of obesity". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (6): 2583–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0535. PMID 15181027.

- ^ Shoelson SE, Herrero L, Naaz A (May 2007). "Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance". Gastroenterology. 132 (6): 2169–80. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.059. PMID 17498510.

- ^ Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB (July 2006). "Inflammation and insulin resistance". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (7): 1793–801. doi:10.1172/JCI29069. PMC 1483173. PMID 16823477.

- ^ Dentali F, Squizzato A, Ageno W (July 2009). "The metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for venous and arterial thrombosis". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 35 (5): 451–7. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1234140. PMID 19739035. S2CID 260320617.

- ^ Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Ezzati M, Woodward M, Rimm EB, Danaei G (March 2014). "Metabolic mediators of the effects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1·8 million participants". Lancet. 383 (9921): 970–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61836-X. PMC 3959199. PMID 24269108.

- ^ Aune D, Sen A, Norat T, Janszky I, Romundstad P, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ (February 2016). "Body Mass Index, Abdominal Fatness, and Heart Failure Incidence and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies". Circulation. 133 (7): 639–49. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016801. PMID 26746176. S2CID 115876581.

- ^ Darvall KA, Sam RC, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW, Adam DJ (February 2007). "Obesity and thrombosis". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 33 (2): 223–33. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.006. PMID 17185009.

- ^ a b c d Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A (June 2007). "Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 56 (6): 901–16, quiz 917–20. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004. PMID 17504714.

- ^ Hahler B (June 2006). "An overview of dermatological conditions commonly associated with the obese patient". Ostomy/Wound Management. 52 (6): 34–6, 38, 40 passim. PMID 16799182.

- ^ a b c Arendas K, Qiu Q, Gruslin A (June 2008). "Obesity in pregnancy: pre-conceptional to postpartum consequences". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 30 (6): 477–488. doi:10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32863-8. PMID 18611299.

- ^ a b c d Dibaise JK, Foxx-Orenstein AE (July 2013). "Role of the gastroenterologist in managing obesity". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 7 (5): 439–51. doi:10.1586/17474124.2013.811061. PMID 23899283. S2CID 26275773.

- ^ Harney D, Patijn J (2007). "Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies". Pain Medicine (Review). 8 (8): 669–77. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00227.x. PMID 18028045.

- ^ Bigal ME, Lipton RB (January 2008). "Obesity and chronic daily headache". Current Pain and Headache Reports (Review). 12 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0011-8. PMID 18417025. S2CID 23729708.

- ^ Sharifi-Mollayousefi A, Yazdchi-Marandi M, Ayramlou H, Heidari P, Salavati A, Zarrintan S, Sharifi-Mollayousefi A (February 2008). "Assessment of body mass index and hand anthropometric measurements as independent risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome". Folia Morphologica. 67 (1): 36–42. PMID 18335412.

- ^ Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Wang Y (May 2008). "Obesity and central obesity as risk factors for incident dementia and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obesity Reviews (Meta-analysis). 9 (3): 204–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00473.x. PMC 4887143. PMID 18331422.

- ^ Wall M (March 2008). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri)". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports (Review). 8 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1007/s11910-008-0015-0. PMID 18460275. S2CID 17285706.

- ^ Munger KL, Chitnis T, Ascherio A (November 2009). "Body size and risk of MS in two cohorts of US women". Neurology (Comparative Study). 73 (19): 1543–50. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c0d6e0. PMC 2777074. PMID 19901245.

- ^ Basen-Engquist K, Chang M (February 2011). "Obesity and cancer risk: recent review and evidence". Current Oncology Reports. 13 (1): 71–6. doi:10.1007/s11912-010-0139-7. PMC 3786180. PMID 21080117.

- ^ a b c Poulain M, Doucet M, Major GC, Drapeau V, Sériès F, Boulet LP, Tremblay A, Maltais F (April 2006). "The effect of obesity on chronic respiratory diseases: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies". CMAJ. 174 (9): 1293–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051299. PMC 1435949. PMID 16636330.

- ^ Poly TN, Islam MM, Yang HC, Lin MC, Jian WS, Hsu MH, Jack Li YC (5 February 2021). "Obesity and Mortality Among Patients Diagnosed With COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Medicine. 8: 620044. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.620044. PMC 7901910. PMID 33634150.

- ^ Aune D, Norat T, Vatten LJ (December 2014). "Body mass index and the risk of gout: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies". European Journal of Nutrition. 53 (8): 1591–601. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0766-0. PMID 25209031. S2CID 38095938.

- ^ Tukker A, Visscher TL, Picavet HS (March 2009). "Overweight and health problems of the lower extremities: osteoarthritis, pain and disability". Public Health Nutrition (Research Support). 12 (3): 359–68. doi:10.1017/S1368980008002103. PMID 18426630.

- ^ Molenaar EA, Numans ME, van Ameijden EJ, Grobbee DE (November 2008). "[Considerable comorbidity in overweight adults: results from the Utrecht Health Project]". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (English abstract) (in Dutch). 152 (45): 2457–63. PMID 19051798.

- ^ Corona G, Rastrelli G, Filippi S, Vignozzi L, Mannucci E, Maggi M (2014). "Erectile dysfunction and central obesity: an Italian perspective". Asian Journal of Andrology. 16 (4): 581–91. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.126386. PMC 4104087. PMID 24713832.

- ^ Hunskaar S (2008). "A systematic review of overweight and obesity as risk factors and targets for clinical intervention for urinary incontinence in women". Neurourology and Urodynamics (Review). 27 (8): 749–57. doi:10.1002/nau.20635. PMID 18951445. S2CID 20378183.

- ^ Ejerblad E, Fored CM, Lindblad P, Fryzek J, McLaughlin JK, Nyrén O (June 2006). "Obesity and risk for chronic renal failure". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (Research Support). 17 (6): 1695–702. doi:10.1681/ASN.2005060638. PMID 16641153.

- ^ Makhsida N, Shah J, Yan G, Fisch H, Shabsigh R (September 2005). "Hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome: implications for testosterone therapy". The Journal of Urology (Review). 174 (3): 827–34. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.612.1060. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000169490.78443.59. PMID 16093964.

- ^ Pestana IA, Greenfield JM, Walsh M, Donatucci CF, Erdmann D (October 2009). "Management of "buried" penis in adulthood: an overview". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (Review). 124 (4): 1186–95. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b5a37f. PMID 19935302. S2CID 36775257.

- ^ Denis GV, Hamilton JA (October 2013). "Healthy obese persons: how can they be identified and do metabolic profiles stratify risk?". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 20 (5): 369–376. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000433058.78485.b3. PMC 3934493. PMID 23974763.

- ^ a b Blüher M (May 2020). "Metabolically Healthy Obesity". Endocrine Reviews. 41 (3): bnaa004. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnaa004. PMC 7098708. PMID 32128581.

- ^ a b c Smith GI, Mittendorfer B, Klein S (October 2019). "Metabolically healthy obesity: facts and fantasies". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 129 (10): 3978–3989. doi:10.1172/JCI129186. PMC 6763224. PMID 31524630.

- ^ Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, et al. (July 2016). "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for Medical Care of Patients with Obesity". Endocrine Practice. 22 (Suppl 3): 1–203. doi:10.4158/EP161365.GL. PMID 27219496. S2CID 3996442.

- ^ van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Nuotio M, Slagter SN, Doiron D, Fischer K, Foco L, Gaye A, Gögele M, Heier M, Hiekkalinna T, Joensuu A (February 2014). "The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolically healthy obesity in Europe: a collaborative analysis of ten large cohort studies". BMC Endocrine Disorders. BioMed Central (Springer Nature). 14: 9. doi:10.1186/1472-6823-14-9. ISSN 1472-6823. PMC 3923238. PMID 24484869.

- ^ Stolk R (26 November 2013). "The Healthy Obese Project (HOP)" (PDF). BioSHaRE Newsletter (4): 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Scott D, Shore-Lorenti C, McMillan LB, Mesinovic J, Clark RA, Hayes A, Sanders KM, Duque G, Ebeling PR (March 2018). "Calf muscle density is independently associated with physical function in overweight and obese older adults". Journal of Musculoskeletal and Neuronal Interactions. Likovrisi: Hylonome Publications. 18 (1): 9–17. ISSN 1108-7161. PMC 5881124. PMID 29504574.

- ^ Karelis AD (October 2008). "Metabolically healthy but obese individuals". The Lancet. 372 (9646): 1281–1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61531-7. PMID 18929889. S2CID 29584669.

- ^ a b Schmidt DS, Salahudeen AK (2007). "Obesity-survival paradox-still a controversy?". Seminars in Dialysis (Review). 20 (6): 486–92. doi:10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00349.x. PMID 17991192. S2CID 37354831.

- ^ a b U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (June 2003). "Behavioral counseling in primary care to promote a healthy diet: recommendations and rationale". American Family Physician (Review). 67 (12): 2573–6. PMID 12825847.

- ^ Habbu A, Lakkis NM, Dokainish H (October 2006). "The obesity paradox: fact or fiction?". The American Journal of Cardiology (Review). 98 (7): 944–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.039. PMID 16996880.

- ^ Romero-Corral A, Montori VM, Somers VK, Korinek J, Thomas RJ, Allison TG, Mookadam F, Lopez-Jimenez F (August 2006). "Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studies". Lancet (Review). 368 (9536): 666–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69251-9. PMID 16920472. S2CID 23306195.

- ^ Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fonarow GC, Norris CM, McAlister FA (July 2008). "Body mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysis". American Heart Journal (Meta-analysis, Review). 156 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.014. PMID 18585492. S2CID 25332291.

- ^ Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Norris CM, Mullen JC, Pretorius V, Kalantar-Zadeh K (February 2008). "Effect of obesity on short- and long-term mortality postcoronary revascularization: a meta-analysis". Obesity (Meta-analysis). 16 (2): 442–50. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.36. PMID 18239657. S2CID 205524756.

- ^ Diercks DB, Roe MT, Mulgund J, Pollack CV, Kirk JD, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Smith SC, Boden WE, Peterson ED (July 2006). "The obesity paradox in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines Quality Improvement Initiative". American Heart Journal (Research Support). 152 (1): 140–8. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.09.024. PMID 16824844.

- ^ a b c d e Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, Hramiak IM, Sharma AM, Ur E (April 2007). "2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]". CMAJ (Practice Guideline, Review). 176 (8): S1–13. doi:10.1503/cmaj.061409. PMC 1839777. PMID 17420481.

- ^ Drewnowski A, Specter SE (January 2004). "Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Review). 79 (1): 6–16. doi:10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. PMID 14684391.

- ^ Nestle M, Jacobson MF (2000). "Halting the obesity epidemic: a public health policy approach". Public Health Reports (Research Support). 115 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1093/phr/115.1.12 (inactive 27 January 2024). JSTOR 4598478. PMC 1308552. PMID 10968581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 메인트: DOI 2024년 1월 기준 비활성화 (링크) - ^ James WP (March 2008). "The fundamental drivers of the obesity epidemic". Obesity Reviews (Review). 9 (Suppl 1): 6–13. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00432.x. PMID 18307693. S2CID 19894128.

- ^ 마스와 PS. "향정신성 약물과 관련된 체중 증가" 약물치료에 대한 전문가 의견. 2000;1:377–389.

- ^ 바움, 찰스 L. "담배 비용이 체질량지수와 비만에 미치는 영향" 보건경제학 18.1 (2009): 3-19. APA

- ^ Memon AN, Gowda AS, Rallabhandi B, Bidika E, Fayyaz H, Salib M, Cancarevic I (September 2020). "Have Our Attempts to Curb Obesity Done More Harm Than Good?". Cureus. 12 (9): e10275. doi:10.7759/cureus.10275. PMC 7538029. PMID 33042711. S2CID 221794897.

- ^ Keith SW, Redden DT, Katzmarzyk PT, Boggiano MM, Hanlon EC, Benca RM, et al. (November 2006). "Putative contributors to the secular increase in obesity: exploring the roads less traveled". International Journal of Obesity (Review). 30 (11): 1585–1594. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803326. PMID 16801930. S2CID 342831.

- ^ 맥알리스터, 에밀리 제트 외. "비만 유행의 유력한 원인" 식품과학과 영양학에서의 비평적 고찰 vol. 49,10 (2009): 868-913. doi: 10.1080/10408390903372599

- ^ Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, Drewnowski A, Ravussin E, Redman LM, Leibel RL (August 2017). "Obesity Pathogenesis: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement". Endocrine Reviews (Professional society guidelines). 38 (4): 267–296. doi:10.1210/er.2017-00111. PMC 5546881. PMID 28898979.

- ^ a b c d e f "EarthTrends: Nutrition: Calorie supply per capita". World Resources Institute. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Bojanowska E, Ciosek J (15 February 2016). "Can We Selectively Reduce Appetite for Energy-Dense Foods? An Overview of Pharmacological Strategies for Modification of Food Preference Behavior". Current Neuropharmacology. 14 (2): 118–42. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666151109103147. PMC 4825944. PMID 26549651.

- ^ "USDA: frsept99b". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ "Diet composition and obesity among Canadian adults". Statistics Canada.

- ^ National Control for Health Statistics. "Nutrition For Everyone". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Marantz PR, Bird ED, Alderman MH (March 2008). "A call for higher standards of evidence for dietary guidelines". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 34 (3): 234–40. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.017. PMID 18312812.

- ^ Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL (October 2002). "Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000". JAMA. 288 (14): 1723–7. doi:10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. PMID 12365955.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (February 2004). "Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients—United States, 1971–2000". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 53 (4): 80–2. PMID 14762332.

- ^ a b c d e f Caballero B (2007). "The global epidemic of obesity: an overview". Epidemiologic Reviews. 29: 1–5. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm012. PMID 17569676.

- ^ Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB (June 2011). "Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men". The New England Journal of Medicine (Meta-analysis). 364 (25): 2392–404. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. PMC 3151731. PMID 21696306.

- ^ Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB (August 2006). "Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Review). 84 (2): 274–88. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.2.274. PMC 3210834. PMID 16895873.

- ^ Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL (January 2009). "Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity". Obesity Reviews (Review). 10 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00523.x. PMID 18764885. S2CID 28672221.

- ^ Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Willett WC, Hu FB (November 2010). "Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis". Diabetes Care (Meta-analysis, Review). 33 (11): 2477–83. doi:10.2337/dc10-1079. PMC 2963518. PMID 20693348.

- ^ Wamberg L, Pedersen SB, Rejnmark L, Richelsen B (December 2015). "Causes of Vitamin D Deficiency and Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Metabolic Complications in Obesity: a Review". Current Obesity Reports. 4 (4): 429–40. doi:10.1007/s13679-015-0176-5. PMID 26353882. S2CID 809587.

- ^ Rosenheck R (November 2008). "Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk". Obesity Reviews (Review). 9 (6): 535–47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00477.x. PMID 18346099. S2CID 25820487.

- ^ Lin BH, Guthrie J, Frazao E (1999). "Nutrient contribution of food away from home". In Frazão E (ed.). Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 750: America's Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. pp. 213–39. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012.

- ^ Pollan M (22 April 2007). "You Are What You Grow". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Kopelman P, Caterson I (2005). "An overview of obesity management". In Kopelman PG, Caterson ID, Stock MJ, Dietz WH (eds.). Clinical obesity in adults and children: In Adults and Children. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 319–326 (324). ISBN 978-1-4051-1672-5.

- ^ Schieszer J. Metabolism alone doesn't explain how thin people stay thin. The Medical Post.

- ^ a b "Obesity and overweight". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ a b c "WHO Physical Inactivity: A Global Public Health Problem". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ a b Ness-Abramof R, Apovian CM (February 2006). "Diet modification for treatment and prevention of obesity". Endocrine (Review). 29 (1): 5–9. doi:10.1385/ENDO:29:1:135. PMID 16622287. S2CID 31964889.

- ^ a b Salmon J, Timperio A (2007). "Prevalence, Trends and Environmental Influences on Child and Youth Physical Activity". Pediatric Fitness (Review). Medicine and Sport Science. Vol. 50. pp. 183–99. doi:10.1159/000101391. ISBN 978-3-318-01396-2. PMID 17387258.

- ^ Borodulin K, Laatikainen T, Juolevi A, Jousilahti P (June 2008). "Thirty-year trends of physical activity in relation to age, calendar time and birth cohort in Finnish adults". European Journal of Public Health (Research Support). 18 (3): 339–44. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckm092. PMID 17875578.

- ^ Brownson RC, Boehmer TK, Luke DA (2005). "Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors?". Annual Review of Public Health (Review). 26: 421–43. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437. PMID 15760296.

- ^ Wilks DC, Sharp SJ, Ekelund U, Thompson SG, Mander AP, Turner RM, Jebb SA, Lindroos AK (February 2011). "Objectively measured physical activity and fat mass in children: a bias-adjusted meta-analysis of prospective studies". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17205. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617205W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017205. PMC 3044163. PMID 21383837.

- ^ Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH (April 1996). "Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine (Review). 150 (4): 356–62. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290022003. PMID 8634729.

- ^ Vioque J, Torres A, Quiles J (December 2000). "Time spent watching television, sleep duration and obesity in adults living in Valencia, Spain". International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders (Research Support). 24 (12): 1683–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801434. PMID 11126224. S2CID 26129544.

- ^ Tucker LA, Bagwell M (July 1991). "Television viewing and obesity in adult females". American Journal of Public Health. 81 (7): 908–11. doi:10.2105/AJPH.81.7.908. PMC 1405200. PMID 2053671.

- ^ Emanuel EJ (2008). "Media + Child and Adolescent Health: A Systematic Review" (PDF). Common Sense Media. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ Jones M. "Case Study: Cataplexy and SOREMPs Without Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Prader Willi Syndrome. Is This the Beginning of Narcolepsy in a Five Year Old?". European Society of Sleep Technologists. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ Albuquerque D, Nóbrega C, Manco L, Padez C (September 2017). "The contribution of genetics and environment to obesity". British Medical Bulletin. 123 (1): 159–173. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldx022. PMID 28910990.

- ^ Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH (May 2006). "Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Review). 26 (5): 968–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.508.7066. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000216787.85457.f3. PMID 16627822. S2CID 6052584.

- ^ Loos RJ, Bouchard C (May 2008). "FTO: the first gene contributing to common forms of human obesity". Obesity Reviews (Review). 9 (3): 246–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00481.x. PMID 18373508. S2CID 23487924.

- ^ Yang W, Kelly T, He J (2007). "Genetic epidemiology of obesity". Epidemiologic Reviews (Review). 29: 49–61. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm004. PMID 17566051.

- ^ Walley AJ, Asher JE, Froguel P (July 2009). "The genetic contribution to non-syndromic human obesity". Nature Reviews. Genetics (Review). 10 (7): 431–42. doi:10.1038/nrg2594. PMID 19506576. S2CID 10870369.

- ^ Farooqi S, O'Rahilly S (December 2006). "Genetics of obesity in humans". Endocrine Reviews (Review). 27 (7): 710–18. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0040. PMID 17122358.

- ^ Kolata G (2007). Rethinking thin: The new science of weight loss – and the myths and realities of dieting. Picador. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-312-42785-6.

- ^ Walley AJ, Asher JE, Froguel P (July 2009). "The genetic contribution to non-syndromic human obesity". Nature Reviews. Genetics (Review). 10 (7): 431–42. doi:10.1038/nrg2594. PMID 19506576. S2CID 10870369.

However, it is also clear that genetics greatly influences this situation, giving individuals in the same 'obesogenic' environment significantly different risks of becoming obese.

- ^ Rosén T, Bosaeus I, Tölli J, Lindstedt G, Bengtsson BA (January 1993). "Increased body fat mass and decreased extracellular fluid volume in adults with growth hormone deficiency". Clinical Endocrinology. 38 (1): 63–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb00974.x. PMID 8435887. S2CID 25725625.

- ^ Zametkin AJ, Zoon CK, Klein HW, Munson S (February 2004). "Psychiatric aspects of child and adolescent obesity: a review of the past 10 years". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Review). 43 (2): 134–50. doi:10.1097/00004583-200402000-00008. PMID 14726719.

- ^ Chiles C, van Wattum PJ (2010). "Psychiatric aspects of the obesity crisis". Psychiatr Times. 27 (4): 47–51.

- ^ Yach D, Stuckler D, Brownell KD (January 2006). "Epidemiologic and economic consequences of the global epidemics of obesity and diabetes". Nature Medicine. 12 (1): 62–6. doi:10.1038/nm0106-62. PMID 16397571. S2CID 37456911.

- ^ Sobal J, Stunkard AJ (March 1989). "Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature". Psychological Bulletin (Review). 105 (2): 260–75. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.260. PMID 2648443.

- ^ a b McLaren L (2007). "Socioeconomic status and obesity". Epidemiologic Reviews (Review). 29: 29–48. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm001. PMID 17478442.

- ^ a b Wilkinson R, Picket K (2009). The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane. pp. 91–101. ISBN 978-1-84614-039-6.

- ^ Christakis NA, Fowler JH (July 2007). "The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years". The New England Journal of Medicine (Research Support). 357 (4): 370–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.581.4893. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa066082. PMID 17652652. S2CID 264194973.

- ^ Björntorp P (May 2001). "Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities?". Obesity Reviews. 2 (2): 73–86. doi:10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00027.x. PMID 12119665. S2CID 23665421.

- ^ Goodman E, Adler NE, Daniels SR, Morrison JA, Slap GB, Dolan LM (August 2003). "Impact of objective and subjective social status on obesity in a biracial cohort of adolescents". Obesity Research (Research Support). 11 (8): 1018–26. doi:10.1038/oby.2003.140. PMID 12917508.

- ^ Flegal KM, Troiano RP, Pamuk ER, Kuczmarski RJ, Campbell SM (November 1995). "The influence of smoking cessation on the prevalence of overweight in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (18): 1165–70. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511023331801. PMID 7565970.

- ^ Chiolero A, Faeh D, Paccaud F, Cornuz J (April 2008). "Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Review). 87 (4): 801–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. PMID 18400700.

- ^ Weng HH, Bastian LA, Taylor DH, Moser BK, Ostbye T (2004). "Number of children associated with obesity in middle-aged women and men: results from the health and retirement study". Journal of Women's Health (Comparative Study). 13 (1): 85–91. doi:10.1089/154099904322836492. PMID 15006281.

- ^ Bellows-Riecken KH, Rhodes RE (February 2008). "A birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood". Preventive Medicine (Review). 46 (2): 99–110. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.003. PMID 17919713.

- ^ "Obesity and Overweight" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ McCormack GR, Virk JS (September 2014). "Driving towards obesity: a systematized literature review on the association between motor vehicle travel time and distance and weight status in adults". Preventive Medicine. 66: 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.002. hdl:1880/115549. PMID 24929196. S2CID 12470420.

- ^ King DM, Jacobson SH (March 2017). "What Is Driving Obesity? A Review on the Connections Between Obesity and Motorized Transportation". Current Obesity Reports. 6 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1007/s13679-017-0238-y. PMID 28243840. S2CID 207474312.

- ^ a b Caballero B (March 2001). "Introduction. Symposium: Obesity in developing countries: biological and ecological factors". The Journal of Nutrition (Review). 131 (3): 866S–870S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.3.866s. PMID 11238776.

- ^ DiBaise JK, Zhang H, Crowell MD, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Decker GA, Rittmann BE (April 2008). "Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity". Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Review). 83 (4): 460–9. doi:10.4065/83.4.460. PMID 18380992.

- ^ "Antibiotics: repeated treatments before the age of two could be a factor in obesity". Prescrire International. 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ a b Cox LM, Blaser MJ (March 2015). "Antibiotics in early life and obesity". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 11 (3): 182–190. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.210. PMC 4487629. PMID 25488483.

- ^ Falagas ME, Kompoti M (July 2006). "Obesity and infection". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases (Review). 6 (7): 438–46. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70523-0. PMID 16790384.

- ^ a b Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, Miller MA (May 2008). "Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults". Sleep. 31 (5): 619–626. doi:10.1093/sleep/31.5.619. PMC 2398753. PMID 18517032.

- ^ Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, Ji C, Cappuccio FP (April 2018). "Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies". Sleep. 41 (4). doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy018. PMID 29401314.

- ^ Horne J (May 2011). "Obesity and short sleep: unlikely bedfellows?". Obesity Reviews. 12 (5): e84–e94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00847.x. PMID 21366837. S2CID 23948346.

- ^ a b c d Gerlach G, Herpertz S, Loeber S (January 2015). "Personality traits and obesity: a systematic review". Obesity Reviews. 16 (1): 32–63. doi:10.1111/obr.12235. PMID 25470329. S2CID 46500679.

- ^ Lauder W, Mummery K, Jones M, Caperchione C (May 2006). "A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations". Psychology, Health & Medicine. 11 (2): 233–245. doi:10.1080/13548500500266607. PMID 17129911. S2CID 24974378.

- ^ Jokela M, Hintsanen M, Hakulinen C, Batty GD, Nabi H, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimäki M (April 2013). "Association of personality with the development and persistence of obesity: a meta-analysis based on individual-participant data". Obesity Reviews. 14 (4): 315–323. doi:10.1111/obr.12007. PMC 3717171. PMID 23176713.

- ^ An R, et al. (July 2019). "Trade openness and the obesity epidemic: a cross-national study of 175 countries during 1975-2016". Annals of Epidemiology. 37: 31–36.

- ^ a b Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, Drewnowski A, Ravussin E, Redman LM, et al. (2017). "Obesity Pathogenesis: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement". Endocr Rev. 38 (4): 267–296. doi:10.1210/er.2017-00111. PMC 5546881. PMID 28898979.

- ^ a b c d Flier JS (January 2004). "Obesity wars: molecular progress confronts an expanding epidemic". Cell (Review). 116 (2): 337–50. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01081-X. PMID 14744442. S2CID 6010027.

- ^ Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM (December 1994). "Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue". Nature (Research Support). 372 (6505): 425–32. Bibcode:1994Natur.372..425Z. doi:10.1038/372425a0. PMID 7984236. S2CID 4359725.

- ^ Boulpaep EL, Boron WF (2003). Medical physiology: A cellular and molecular approach. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 1227. ISBN 978-0-7216-3256-8.

- ^ a b US Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). "2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans - health.gov". health.gov. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. (September 2019). "2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 140 (11): e596–e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. PMC 7734661. PMID 30879355.

- ^ a b Strychar I (January 2006). "Diet in the management of weight loss". CMAJ (Review). 174 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1503/cmaj.045037. PMC 1319349. PMID 16389240.

- ^ Shick SM, Wing RR, Klem ML, McGuire MT, Hill JO, Seagle H (April 1998). "Persons successful at long-term weight loss and maintenance continue to consume a low-energy, low-fat diet". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 98 (4): 408–413. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00093-5. PMID 9550162.

- ^ Tate DF, Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Wing RR (April 2007). "Long-term weight losses associated with prescription of higher physical activity goals. Are higher levels of physical activity protective against weight regain?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Randomized Controlled Trial). 85 (4): 954–959. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.4.954. PMID 17413092.

- ^ Thomas JG, Bond DS, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR (January 2014). "Weight-loss maintenance for 10 years in the National Weight Control Registry". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 46 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.019. PMID 24355667.

- ^ a b c Yannakoulia M, Poulimeneas D, Mamalaki E, Anastasiou CA (March 2019). "Dietary modifications for weight loss and weight loss maintenance". Metabolism. 92: 153–162. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.01.001. PMID 30625301.

- ^ a b Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. (September 2018). "Behavioral Weight Loss Interventions to Prevent Obesity-Related Morbidity and Mortality in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 320 (11): 1163–1171. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.13022. PMID 30326502.

- ^ Gibson AA, Sainsbury A (July 2017). "Strategies to Improve Adherence to Dietary Weight Loss Interventions in Research and Real-World Settings". Behavioral Sciences. 7 (3): 44. doi:10.3390/bs7030044. PMC 5618052. PMID 28696389.

- ^ a b c d Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) (1987). "Dietary treatment of obesity". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 499 (1): 250–263. Bibcode:1987NYASA.499..250B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36216.x. PMID 3300485. S2CID 45507530. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Johnston BC, Kanters S, Bandayrel K, Wu P, Naji F, Siemieniuk RA, Ball GD, Busse JW, Thorlund K, Guyatt G, Jansen JP, Mills EJ (September 2014). "Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 312 (9): 923–33. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10397. PMID 25182101.

- ^ Naude CE, Schoonees A, Senekal M, Young T, Garner P, Volmink J (2014). "Low carbohydrate versus isoenergetic balanced diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE (Research Support). 9 (7): e100652. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j0652N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100652. PMC 4090010. PMID 25007189.

- ^ Wing RR, Phelan S (July 2005). "Long-term weight loss maintenance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Review). 82 (1 Suppl): 222S–225S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. PMID 16002825.

- ^ Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, Glinkowski S, Roseboom T, Tomlinson JW, Kunz R, Mol BW, Coomarasamy A, Khan KS (May 2012). "Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: meta-analysis of randomised evidence". BMJ (Meta-analysis). 344: e2088. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2088. PMC 3355191. PMID 22596383.

- ^ LeFevre ML (October 2014). "Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161 (8): 587–93. doi:10.7326/M14-1796. PMID 25155419. S2CID 262280720.

- ^ Satcher D (2001). The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of Surgeon General. ISBN 978-0-16-051005-2.

- ^ Barnes B (18 July 2007). "Limiting Ads of Junk Food to Children". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ "Fewer Sugary Drinks Key to Weight Loss". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ "WHO urges global action to curtail consumption and health impacts of sugary drinks". WHO. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Brennan Ramirez LK, Hoehner CM, Brownson RC, Cook R, Orleans CT, Hollander M, Barker DC, Bors P, Ewing R, Killingsworth R, Petersmarck K, Schmid T, Wilkinson W (December 2006). "Indicators of activity-friendly communities: an evidence-based consensus process". American Journal of Preventive Medicine (Research Support). 31 (6): 515–24. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.026. PMID 17169714.

- ^ Stead M, Angus K, Langley T, Katikireddi SV, Hinds K, Hilton S, et al. (May 2019). "Mass media to communicate public health messages in six health topic areas: a systematic review and other reviews of the evidence". Public Health Research. 7 (8): 1–206. doi:10.3310/phr07080. PMID 31046212.

- ^ a b "How can local authorities reduce obesity? Insights from NIHR research". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 19 May 2022.

- ^ Crockett RA, King SE, Marteau TM, Prevost AT, Bignardi G, Roberts NW, et al. (February 2018). "Nutritional labelling for healthier food or non-alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD009315. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009315.pub2. PMC 5846184. PMID 29482264.

- ^ Nestle M (June 2022). "Regulating the Food Industry: An Aspirational Agenda". American Journal of Public Health. 112 (6): 853–858. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.306844. PMC 9137006. PMID 35446606.

- ^ Finlay M, van Tulleken C, Miles ND, Onuchukwu T, Bury E (20 April 2023). "How did ultra-processed foods take over, and what are they doing to us?". the Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Onakpoya IJ, Heneghan CJ, Aronson JK (November 2016). "Post-marketing withdrawal of anti-obesity medicinal products because of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review". BMC Medicine. 14 (1): 191. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0735-y. PMC 5126837. PMID 27894343.

- ^ a b c Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA (January 2017). "Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity". The New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (3): 254–266. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1514009. PMID 28099824. S2CID 20407626.

- ^ a b Wolfe SM (August 2013). "When EMA and FDA decisions conflict: differences in patients or in regulation?". BMJ. 347: f5140. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5140. PMID 23970394. S2CID 46738622.

- ^ "Belviq, Belviq XR (lorcaserin) by Eisai: Drug Safety Communication – FDA Requests Withdrawal of Weight-Loss Drug". FDA. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Rucker D, Padwal R, Li SK, Curioni C, Lau DC (December 2007). "Long term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: updated meta-analysis". BMJ (Meta-analysis). 335 (7631): 1194–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39385.413113.25. PMC 2128668. PMID 18006966.