뚱뚱해요.

Fat

| 음식에 들어있는 지방의 종류 |

|---|

| 구성 요소들 |

| 제조지방 |

영양학, 생물학, 화학에서, 지방은 보통 지방산의 에스테르 또는 그러한 화합물의 혼합물을 의미하는데, 가장 일반적으로 생물이나 음식에서 발생합니다.[1]

이 용어는 종종 식물성 기름과 동물의 지방 조직의 주요 성분인 트리글리세라이드(글리세롤의 삼중 에스테르)를 지칭합니다.[2] 또는 더 좁게는 실온에서 고체 또는 반고체인 트리글리세라이드를 지칭하며, 따라서 기름을 제외합니다.이 용어는 또한 물에는 불용성이지만 비극성 용매에는 용해되는 탄소, 수소 또는 산소로 구성된 생물학적 관련성이 있는 물질인 지질의 동의어로 더 광범위하게 사용될 수 있습니다.[1]이런 의미에서, 이 용어는 중성지방 외에도 모노글리세리드와 디글리세리드, 인지질(레시틴 등), 스테롤(콜레스테롤 등), 왁스(밀랍 등) [1]및 유리지방산과 같은 여러 다른 유형의 화합물을 포함하며, 이들은 보통 인간의 식단에 더 적은 양으로 존재합니다.[2]

지방은 탄수화물, 단백질과 함께 인간 식단의 3대 주요 영양소 그룹 중 하나이며 [1][3]우유, 버터, 톨로우, 라드, 소금 돼지고기, 식용유와 같은 일반적인 식품의 주요 성분입니다.그들은 많은 동물들에게 주요하고 밀도가 높은 음식 에너지 공급원이며 에너지 저장, 방수, 단열을 포함한 대부분의 생물들에게 중요한 구조적, 대사적 기능을 수행합니다.[4]인체는 식단에 포함되어야 하는 몇 가지 필수 지방산을 제외하고는 다른 음식 재료로부터 필요한 지방을 생산할 수 있습니다.식이 지방은 또한 수용성이 아닌 몇몇 향과 향의 성분과 비타민의 운반체이기도 합니다.[2]

생물학적 중요성

인간과 많은 동물들에게, 지방은 에너지원으로서 그리고 몸이 즉시 필요로 하는 것을 초과하는 에너지를 위한 저장소로서 역할을 합니다.연소되거나 대사될 때 지방 한 그램당 약 9칼로리 (37kJ = 8.8kcal)를 방출합니다.

지방은 또한 필수 지방산의 공급원이며, 중요한 식이요법의 필요조건입니다.비타민 A, D, E, 그리고 K는 지용성 물질인데, 이것은 그것들이 오직 소화되고, 흡수되고, 지방과 함께 수송될 수 있다는 것을 의미합니다.

지방은 건강한 피부와 머리카락을 유지하고, 신체 기관을 충격으로부터 절연시키고, 체온을 유지하고, 건강한 세포 기능을 촉진하는 데 중요한 역할을 합니다.지방은 또한 많은 질병에 대한 유용한 완충 역할을 합니다.특정 물질이 화학적이든 생물학적이든 간에 혈류에서 안전하지 않은 수준에 도달할 때, 신체는 그것을 새로운 지방 조직에 저장함으로써 효과적으로 불쾌감을 주는 물질을 희석시키거나 최소한 평형을 유지할 수 있습니다.[6]이것은 배설, 배뇨, 우발적이거나 의도적인 출혈, 피지 배설, 그리고 발모와 같은 방법으로 신체에서 해로운 물질들이 대사되거나 제거될 때까지 중요한 기관들을 보호하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

지방조직

동물에서 지방 조직 또는 지방 조직은 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 대사 에너지를 저장하는 신체의 수단입니다.지방 세포는 식단과 간 대사에서 유래된 지방을 저장합니다.에너지 스트레스 하에서 이 세포들은 저장된 지방을 분해하여 지방산과 글리세롤을 순환에 공급할 수 있습니다.이러한 대사 활동은 여러 호르몬(예: 인슐린, 글루카곤, 에피네프린)에 의해 조절됩니다.지방 조직은 렙틴 호르몬을 분비하기도 합니다.[7]

생산가공

다양한 화학적, 물리적 기술은 산업적으로 그리고 오두막이나 가정 환경에서 지방의 생산과 가공에 사용됩니다.여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 과일, 씨앗 또는 조류로부터 액체 지방을 추출하기 위해 누름, 예를 들어 올리브에서 올리브 오일

- 헥산 또는 초임계 이산화탄소와 같은 용매를 사용한 용매 추출

- 렌더링, 지방 조직에서 지방이 녹는 것, 예를 들어 톨로우, 라드, 어유, 고래 기름을 생산하는 것

- 버터를 만들기 위해 우유를 씹는 것

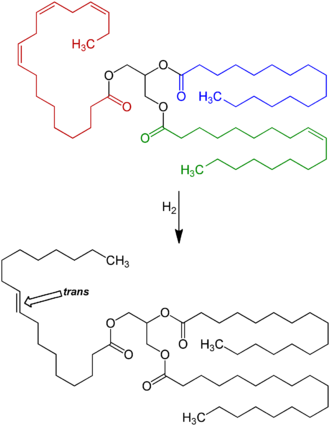

- 지방산의 포화도를 높이기 위한 수소화

- 흥미화, 다양한 트리글리세리드에 걸친 지방산의 재배열

- 융점이 높은 오일 성분을 제거하기 위한 월동

- 버터명확화

신진대사

췌장 리파아제는 에스테르 결합에서 작용하여 결합을 가수분해하고 지방산을 방출합니다.중성지방 형태에서 지질은 십이지장에 흡수될 수 없습니다.지방산, 모노글리세라이드(글리세롤 1개, 지방산 1개), 그리고 일부 디글리세라이드는 일단 트리글리세라이드가 분해되면 십이지장에 흡수됩니다.

장에서, 리파아제와 담즙의 분비에 따라, 중성지방은 지방 분해라고 불리는 과정에서 모노아실글리세롤과 유리지방산으로 분리됩니다.그들은 나중에 장 안에 있는 흡수성 장세포 세포로 옮겨집니다.중성지방은 그것들의 단편으로부터 장세포에서 재건되고 콜레스테롤과 단백질과 함께 포장되어 실로미크론을 형성합니다.이것들은 세포에서 배설되어 림프계에 의해 모아지고 혈액에 섞이기 전에 심장 근처의 큰 혈관으로 운반됩니다.다양한 조직이 카이로미크론을 포획하여 에너지원으로 사용될 중성지방을 방출할 수 있습니다.간세포는 중성지방을 합성하고 저장할 수 있습니다.신체가 에너지원으로 지방산을 필요로 할 때, 호르몬 글루카곤은 유리지방산을 방출하기 위해 호르몬에 민감한 리파아제에 의해 중성지방이 분해됨을 알립니다.뇌가 지방산을 에너지원으로 사용할 수 없기 때문에([8]케톤으로 전환되지 않는 한) 트리글리세라이드의 글리세롤 성분은 디하이드록시아세톤 인산으로 전환하여 포도당신생합성을 거쳐 글리세르알데하이드 3-인산으로 전환되어 뇌 연료로 사용될 수 있습니다.만약 뇌의 필요량이 신체의 필요량보다 많아지면, 지방 세포 또한 그러한 이유로 분해될지도 모릅니다.

중성지방은 세포막을 자유롭게 통과할 수 없습니다.리포단백질 리파아제라고 불리는 혈관 벽에 있는 특별한 효소는 중성지방을 유리지방산과 글리세롤로 분해해야 합니다.지방산은 지방산 수송 단백질(FATP)을 통해 세포에 흡수될 수 있습니다.

매우 낮은 밀도의 지단백(VLDL)과 실로미크론의 주요 성분인 중성지방은 식이지방의 에너지원이자 전달체로서 대사에 중요한 역할을 합니다.그들은 탄수화물(약 4kcal/g 또는 17kJ/g)보다 두 배 이상 많은 에너지(약 9kcal/g 또는 38kJ/g)를 함유하고 있습니다.[9]

영양 및 건강 측면

인간의 식단과 대부분의 생명체에서 가장 흔한 유형의 지방은 삼중 알코올 글리세롤 H(–CHOH–)

3H와 3개의 지방산의 에스테르인 중성지방입니다.트리글리세라이드의 분자는 글리세롤의 각각의 -OH기와 카복실기의 부분인 HO-사이의 축합 반응(특히 에스테르화)의 결과로 설명될 수 있습니다. 물 분자 HO를 제거하고 에스테르 브릿지-O-(O=)C-를 형성하는 각 지방산의 HO(O=)C-.

다른 덜 흔한 유형의 지방에는 글리세롤과 모노글리세라이드가 있는데, 여기서 에스테르화는 글리세롤의 –OH 그룹 중 두 개 또는 한 개로 제한됩니다.세틸 알코올과 같은 다른 알코올은 글리세롤을 대체할 수 있습니다.인지질에서 지방산 중 하나는 인산 또는 이의 모노에스테르로 대체됩니다.다양한 양과 종류의 식이 지방의 이점과 위험은 많은 연구의 대상이 되어 왔고, 여전히 매우 논란이 많은 주제입니다.[10][11][12][13]

필수지방산

인간의 영양에는 알파-리놀렌산(오메가-3 지방산)과 리놀레산(오메가-6 지방산)이라는 두 가지 필수 지방산이 있습니다.[14][5]성체는 이 두 가지로부터 필요한 다른 지질을 합성할 수 있습니다.

식원

| 유형 | 처리. 대우[17] | 포화상태 지방산 | 단불포화 지방산 | 다불포화 지방산 | 스모크 포인트 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 토탈[15] | 올레인식 산성의 (ω-9) | 토탈[15] | α-리놀렌식 산성의 (ω-3) | 리놀레익 산성의 (ω-6) | ω-6:3 비율을 | ||||

| 아보카도[18] | 11.6 | 70.6 | 52–66 [19] | 13.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 12.5:1 | 250°C(482°F)[20] | |

| 브라질너트[21] | 24.8 | 32.7 | 31.3 | 42.0 | 0.1 | 41.9 | 419:1 | 208°C(406°F)[22] | |

| 카놀라[23] | 7.4 | 63.3 | 61.8 | 28.1 | 9.1 | 18.6 | 2:1 | 204°C(400°F)[24] | |

| 코코넛[25] | 82.5 | 6.3 | 6 | 1.7 | 175°C(347°F)[22] | ||||

| 옥수수[26] | 12.9 | 27.6 | 27.3 | 54.7 | 1 | 58 | 58:1 | 232°C (450°F)[24] | |

| 목화씨[27] | 25.9 | 17.8 | 19 | 51.9 | 1 | 54 | 54:1 | 216°C(420°F)[24] | |

| 목화씨[28] | 수소 첨가의 | 93.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5:1 | ||

| 아마씨/ 아마씨[29] | 9.0 | 18.4 | 18 | 67.8 | 53 | 13 | 0.2:1 | 107°C(225°F) | |

| 포도씨 | 10.4 | 14.8 | 14.3 | 74.9 | 0.15 | 74.7 | 아주 높은 | 216°C(421°F)[30] | |

| 삼베씨[31] | 7.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 82.0 | 22.0 | 54.0 | 2.5:1 | 166°C(330°F)[32] | |

| 고올레산 홍화유[33] | 7.5 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 12.8 | 0 | 12.8 | 아주 높은 | 212°C(414°F)[22] | |

| 올리브, 엑스트라 버진[34] | 13.8 | 73.0 | 71.3 | 10.5 | 0.7 | 9.8 | 14:1 | 193°C(380°F)[22] | |

| 손바닥[35] | 49.3 | 37.0 | 40 | 9.3 | 0.2 | 9.1 | 45.5:1 | 235°C(455°F) | |

| 손바닥[36] | 수소 첨가의 | 88.2 | 5.7 | 0 | |||||

| 땅콩[37] | 16.2 | 57.1 | 55.4 | 19.9 | 0.318 | 19.6 | 61.6:1 | 232°C (450°F)[24] | |

| 쌀겨기름 | 25 | 38.4 | 38.4 | 36.6 | 2.2 | 34.4[38] | 15.6:1 | 232°C (450°F)[39] | |

| 참깨[40] | 14.2 | 39.7 | 39.3 | 41.7 | 0.3 | 41.3 | 138:1 | ||

| 콩[41] | 15.6 | 22.8 | 22.6 | 57.7 | 7 | 51 | 7.3:1 | 238°C(460°F)[24] | |

| 콩[42] | 부분적으로 수소화된 | 14.9 | 43.0 | 42.5 | 37.6 | 2.6 | 34.9 | 13.4:1 | |

| 해바라기[43] | 8.99 | 63.4 | 62.9 | 20.7 | 0.16 | 20.5 | 128:1 | 227°C(440°F)[24] | |

| 호두기름[44] | 정제되지 않은 | 9.1 | 22.8 | 22.2 | 63.3 | 10.4 | 52.9 | 5:1 | 160°C(320°F)[45] |

포화지방 대 불포화지방

다른 음식들은 포화지방산과 불포화지방산의 다른 비율로 다른 양의 지방을 포함하고 있습니다.소고기나 요구르트, 아이스크림, 치즈 그리고 버터와 같이 지방 우유를 통째로 또는 줄인 유제품과 같은 몇몇 동물 제품들은 대부분 포화 지방산을 가지고 있습니다 (그리고 몇몇은 상당한 양의 식이 콜레스테롤을 가지고 있습니다).돼지고기, 가금류, 계란, 해산물과 같은 다른 동물 제품들은 대부분 불포화 지방을 가지고 있습니다.산업화된 제빵 제품은 불포화 지방 함량이 높은 지방, 특히 부분적으로 수소화 오일을 함유한 지방을 사용할 수 있으며, 수소화 오일에 튀긴 가공 식품은 포화 지방 함량이 높습니다.[46][47][48]

식물과 어유는 일반적으로 더 높은 비율의 불포화 산을 함유하고 있지만 코코넛 오일과 팜 커널 오일과 같은 예외가 있습니다.[49][50]불포화 지방을 포함한 음식에는 아보카도, 견과류, 올리브 오일 그리고 카놀라와 같은 식물성 기름이 포함됩니다.

많은 신중한 연구들은 식단에서 포화 지방을 시스 불포화 지방으로 대체하는 것이 심혈관 질환,[51][52] 당뇨병, 혹은 사망의 위험을 줄인다는 것을 발견했습니다.[53]이러한 연구는 세계보건기구(WHO)를 포함한 많은 의료기관과 공중보건 부서들이 공식적으로 그 조언을 발표하게 만들었습니다.[54][55]이러한 권장 사항을 가진 일부 국가는 다음과 같습니다.

- 영국[56][57][58][59][60]

- 미국[53][61][62][63][64]

- 인디아[65][66]

- 캐나다[67]

- 오스트레일리아[68]

- 싱가포르[69]

- 뉴질랜드[70]

- 홍콩[71]

2004년의 리뷰는 "특정 포화 지방산 섭취의 안전한 하한선이 확인되지 않았다"는 결론을 내렸고, 다양한 개인의 생활 방식과 유전적 배경에 대한 다양한 포화 지방산 섭취의 영향이 향후 연구에서 초점이 되어야 한다고 권고했습니다.[72]

이 조언은 종종 두 종류의 지방을 각각 나쁜 지방과 좋은 지방으로 표시함으로써 지나치게 단순화됩니다.하지만, 대부분의 천연 식품과 전통적으로 가공된 식품의 지방과 기름은 불포화 지방산과 포화 지방산을 모두 포함하고 있기 때문에,[73] 포화 지방을 완전히 제외하는 것은 비현실적이고 아마도 현명하지 못할 것입니다.예를 들어, 코코넛과 팜유와 같은 포화 지방이 풍부한 일부 음식은 개발도상국 인구의 많은 부분에게 저렴한 식이 칼로리의 중요한 공급원입니다.[74]

미국 영양학회의 2010년 회의에서도 포화 지방을 피하라는 포괄적인 권고가 사람들로 하여금 건강상의 이점을 가질 수 있는 다불포화 지방의 양을 줄이거나 비만과 심장병의 위험이 높은 정제된 탄수화물로 지방을 대체하도록 만들 수 있다는 우려가 표명되었습니다.[75]

이러한 이유로, 예를 들어, 미국 식품 의약국은 포화 지방에서 열량의 최소 10%(고위험군의 경우 7%)를 섭취하고, 전체 지방에서 열량의 평균 30%(또는 그 이하)를 섭취할 것을 권고하고 있습니다.[76][74]2006년 미국 심장 협회(AHA)에서도 일반적인 7% 제한을 권고했습니다.[77][78]

WHO/FAO 보고서는 또한 미리스트 산과 팔미트 산의 함량을 줄이기 위해 지방을 교체할 것을 권고했습니다.[74]

지중해 지역의 많은 나라들에서 널리 퍼져있는 소위 지중해 식단은 북유럽 국가들의 식단보다 더 많은 총 지방을 포함하고 있지만, 그것의 대부분은 올리브 오일과 생선, 채소, 그리고 양고기와 같은 특정한 고기로부터 나오는 불포화 지방산(특히, 단일불포화 그리고 오메가-3)의 형태로 되어 있습니다.포화 지방의 소비가 비교적 최소인 반면.2017년의 리뷰는 지중해식 식단이 심혈관 질환, 전반적인 암 발생, 신경퇴행성 질환, 당뇨병, 사망률을 감소시킬 수 있다는 증거를 발견했습니다.[79]2018년 리뷰에 따르면 지중해식 식단은 전염성이 없는 질병의 위험 감소와 같은 전반적인 건강 상태를 개선할 수 있다고 합니다.그것은 또한 다이어트와 관련된 질병의 사회적, 경제적 비용을 줄일 수 있습니다.[80]

소수의 현대적인 리뷰들이 포화지방에 대한 이러한 부정적인 관점에 도전장을 던졌습니다.예를 들어, 1966년부터 1973년까지 식이 포화 지방을 리놀레산으로 대체하는 것이 관찰된 건강 영향에 대한 증거를 평가한 결과, 모든 원인, 관상동맥 심장 질환, 심혈관 질환으로 인한 사망률을 증가시킨 것으로 나타났습니다.[81]이러한 연구들은 많은 과학자들에 의해 논란이 되어 왔고,[82] 의학계에서는 포화지방과 심혈관 질환이 밀접한 관련이 있다는 것에 의견이 일치하고 있습니다.[83][84][85]그럼에도 불구하고, 이러한 불일치의 연구들은 포화 지방을 다중 불포화 지방으로 대체하는 것의 장점에 대한 논쟁을 촉발시켰습니다.[86]

심혈관질환

포화지방이 심혈관 질환에 미치는 영향은 광범위하게 연구되어 왔습니다.[87]포화지방 섭취량, 혈중 콜레스테롤 수치, 심혈관 질환 발생률 사이에 강하고, 일관되고, 등급화된 관계가 있다는 증거가 있다는 것이 일반적인 일치입니다.[53][87]이 관계는 많은 정부 및 의료 기관을 [88][89]포함하여 인과 관계로 받아들여지고 있습니다.[74][90][91][53][92][93][94][95]

2017년 AHA의 리뷰에 따르면 미국 식단에서 포화지방을 다불포화지방으로 대체하면 심혈관 질환의 위험이 30%[53] 감소할 수 있다고 추정했습니다.

포화 지방의 섭취는 일반적으로 이상지질혈증의 위험인자로 여겨지는데, 이는 높은 총 콜레스테롤, 높은 수준의 중성지방, 높은 수준의 저밀도 지단백(LDL, 나쁜" 콜레스테롤) 또는 낮은 수준의 고밀도 지단백(HDL, 좋은" 콜레스테롤)을 포함합니다.이러한 파라미터들은 차례로 심혈관 질환의 일부 유형에 대한 위험 지표로 여겨집니다.[96][97][98][99][100][92][101][102][103]이러한 효과는 어린이들에게서도 관찰되었습니다.[104]

여러 메타 분석(이전에 발표된 여러 실험 연구의 검토 및 통합)을 통해 포화 지방과 높은 혈청 콜레스테롤 수치 간의 유의한 관계가 확인되었으며,[53][105] 이는 다시 심혈관 질환의 위험 증가와 인과 관계가 있다고 주장되었습니다(소위 지질 가설).[106][107]하지만, 높은 콜레스테롤은 많은 요인에 의해 발생할 수도 있습니다.높은 LDL/HDL 비율과 같은 다른 지표들은 더 예측력이 있는 것으로 입증되었습니다.[107]52개국의 심근경색에 대한 연구에서 ApoB/ApoA1 비율(각각 LDL과 HDL 관련)이 모든 위험인자 중 가장 강력한 CVD 예측 변수였습니다.[108]비만, 중성지방 수치, 인슐린 민감성, 내피 기능 및 혈전 생성과 관련된 다른 경로가 있으며, 그 중에서도 CVD에서 역할을 하지만, 불리한 혈중 지질 프로필이 없는 경우 알려진 다른 위험 요소는 약한 아테로겐 효과만을 가지고 있습니다.[109]포화 지방산은 다양한 지질 수준에 다른 영향을 미칩니다.[110]

암

포화지방 섭취와 암 사이의 관계에 대한 근거는 현저히 약하며, 이에 대한 의학적 합의는 명확하지 않은 것으로 보입니다.

- 2003년에 발표된 메타분석은 포화지방과 유방암 사이의 상당한 양의 관계를 발견했습니다.[111]그러나 이후 두 번의 검토에서 약하거나 유의하지 않은 관계가 발견되었으며 [112][113]교란 요인이 널리 퍼져 있음을 지적했습니다.[112][114]

- 또 다른 리뷰는 동물성 지방 섭취와 대장암 발병 사이의 긍정적인 관계에 대한 제한된 증거를 발견했습니다.[115]

- 다른 메타분석들은 포화지방을 많이 섭취함으로써 난소암의 위험이 증가한다는 증거를 발견했습니다.[116]

- 일부 연구는 혈청 미리스트산과[117][118] 팔미트산[118], 식이 미리스트산과[119] 팔미트산[119] 포화 지방산과 알파-토코페롤 보충과[117] 결합된 혈청 팔미트산이 용량 의존적인 방식으로 전립선암의 위험 증가와 관련이 있음을 나타냈습니다.그러나 이러한 연관성은 실제 원인이라기 보다는 전암 사례와 대조군 사이에서 이러한 지방산의 섭취 또는 대사의 차이를 반영할 수 있습니다.[118]

뼈들

다양한 동물 연구들은 포화 지방의 섭취가 뼈의 미네랄 밀도에 부정적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 나타냈습니다.한 연구는 남성들이 특히 취약할 수 있다고 제안했습니다.[120]

성향 및 전반적인 건강상태

연구에 따르면 포화 지방산 대신 단불포화 지방산을 대체하는 것이 매일의 신체 활동 증가와 휴식 에너지 소비와 관련이 있다고 합니다.팔미트산 식이요법보다 더 많은 신체활동, 더 적은 분노, 그리고 더 적은 짜증이 고올레산 식이요법과 관련이 있었습니다.[121]

단일불포화지방 대 다불포화지방

인간의 식단에서 가장 흔한 지방산은 불포화 또는 단일불포화입니다.단일불포화지방은 붉은 고기, 통유제품, 견과류와 같은 동물의 살과 올리브, 아보카도와 같은 고지방 과일에서 발견됩니다.올리브 오일은 약 75%의 단일 불포화 지방입니다.[122]올레릭 품종이 풍부한 해바라기 오일은 적어도 70% 이상의 단일 불포화 지방을 함유하고 있습니다.[123]카놀라 오일과 캐슈는 모두 약 58%의 단일 불포화 지방입니다.[124]탈로우(소고기 지방)는 약 50%의 단일불포화지방이고,[125] 라드는 약 40%의 단일불포화지방입니다.[126]다른 공급원으로는 헤이즐넛, 아보카도 오일, 마카다미아넛 오일, 포도씨 오일, 땅콩 오일, 참기름, 옥수수 오일, 팝콘, 통곡물 밀, 시리얼, 오트밀, 아몬드 오일, 대마 오일, 차-오일 동백 등이 있습니다.[127]

다불포화 지방산은 주로 견과류, 씨앗, 생선, 씨앗 기름, 그리고 굴에서 발견됩니다.[128]

다불포화 지방의 식품 공급원은 다음과 같습니다.[128][129]

| 식품원(100g) | 다불포화지방(g) |

|---|---|

| 호두 | 47 |

| 카놀라유 | 34 |

| 해바라기씨 | 33 |

| 참깨 | 26 |

| 치아씨 | 23.7 |

| 무염 땅콩 | 16 |

| 땅콩버터 | 14.2 |

| 아보카도 오일 | 13.5[130] |

| 올리브유 | 11 |

| 홍화유 | 12.82[131] |

| 미역 | 11 |

| 정어리 | 5 |

| 콩 | 7 |

| 참치 | 14 |

| 야생연어 | 17.3 |

| 통곡물 밀 | 9.7 |

인슐린 저항성 및 민감성

MUFA(특히 올레산)는 인슐린 저항성의 발생을 낮추는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. PUFA(특히 많은 양의 아라키돈산)와 SFA(아라키돈산 등)는 인슐린 저항성을 증가시킵니다.이러한 비율은 인간 골격근의 인지질과 다른 조직에서도 지수화 될 수 있습니다.이러한 식이 지방과 인슐린 저항성 사이의 관계는 인슐린 저항성과 염증 사이의 관계에서 이차적인 것으로 추정되며, 이는 부분적으로 오메가-3와 -9 둘 다 항염증인 것으로 생각되는 식이 지방 비율(오메가-3/6/9)과 오메가-6 항염증인 것으로 부분적으로 조절됩니다.s, 특히 폴리페놀과 운동(이 두 가지 항염증)을 포함합니다.비록 친염증성 지방과 항염증성 지방 모두 생물학적으로 필요하지만, 대부분의 미국 식단에서 지방 식이 비율은 오메가-6 쪽으로 치우쳐 있으며, 그에 따른 염증 억제와 인슐린 저항성 강화가 뒤따릅니다.[73]이것은 다불포화 지방이 인슐린 저항성에 대한 보호 효과가 있다는 것을 보여주는 제안과는 반대되는 것입니다.[citation needed]

대규모 KANWU 연구는 MUFA를 증가시키고 SFA 섭취를 감소시키는 것이 인슐린 민감성을 향상시킬 수 있다는 것을 발견했지만, 식단의 전체적인 지방 섭취가 적었을 때에만 그러했습니다.[132]그러나 일부 MUFA는 인슐린 저항성(SFA와 같이)을 촉진할 수 있는 반면 PUFA는 인슐린 저항성을 보호할 수 있습니다.[133][134][clarification needed]

암

적혈구 막의 다른 MUFA와 함께 올레산의 수준은 유방암 위험과 긍정적으로 연관되어 있었습니다.동일한 막의 포화 지수(SI)는 유방암 위험과 역으로 연관되어 있었습니다.MUFA와 적혈구막의 낮은 SI는 폐경 후 유방암의 예측 인자입니다.이 두 변수 모두 delta-9 desaturase 효소( δ9-d)의 활성에 의존합니다.

PUFA 섭취 및 암에 대한 관찰 임상 시험의 결과는 일관성이 없으며 성별 및 유전적 위험을 포함한 암 발생 요인에 따라 다양합니다.[136]일부 연구는 오메가3 PUFA의 높은 섭취량 및/또는 혈액 수준과 유방암 및 대장암을 포함한 특정 암의 위험 감소 간의 연관성을 보여주는 반면, 다른 연구는 암 위험과의 연관성을 발견하지 못했습니다.[136][137]

임신 장애

다불포화지방 보충은 고혈압이나 전결장증과 같은 임신 관련 질환의 발생에는 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 나타났으나 임신 기간을 약간 늘리고 조기 조산 발생을 감소시킬 수 있습니다.[128]

미국과 유럽의 전문가 패널들은 태아와 신생아의 DHA 상태를 향상시키기 위해 임산부와 수유부가 일반인보다 더 많은 양의 다불포화지방을 섭취할 것을 권고하고 있습니다.[128]

"C는 뚱뚱하다" vs.트랜스지방

자연계에서 불포화 지방산은 트랜스와 반대로 cis 구성으로 이중 결합을 일반적으로 갖습니다.[138]그럼에도 불구하고, 트랜스 지방산(TFA)은 반추동물(소와 양 등)의 고기와 우유에서 소량 발생하며,[139][140] 일반적으로 전체 지방의 2-5%입니다.[141]공액 리놀레산(CLA)과 백신산을 포함하는 천연 TFA는 이 동물들의 반추에서 유래합니다.CLA는 두 개의 이중 결합을 가지고 있는데, 하나는 시스 구조이고 하나는 트랜스 구조이며, 이것은 동시에 시스- 및 트랜스 지방산을 만듭니다.[142]

| 음식종류 | 트랜스지방 함량 |

|---|---|

| 버터를 바른 | 2~7g |

| 통밀크 | 0.07 ~ 0.1g |

| 동물성 지방 | 0~5g[141] |

| 갈은 쇠고기 | 1g |

인간의 식단에서 트랜스 지방산이 식물성 기름과 생선 기름의 부분적인 수소화의 의도하지 않은 부산물이라는 것이 밝혀지면서 우려가 제기되었습니다.이러한 트랜스 지방산은 먹을 수 있지만, 많은 건강 문제와 관련되어 있습니다.[144]

1902년 빌헬름 노르만(Wilhelm Normann)에 의해 발명되고 특허를 받은 수소화 공정은 고래나 어유와 같은 비교적 저렴한 액체 지방을 더 많은 고체 지방으로 바꾸는 것과 부패를 방지함으로써 유통기한을 연장하는 것을 가능하게 했습니다.(처음에는 소비자의 혐오를 피하기 위해 지방 공급원과 과정을 비밀에 부쳤습니다.)[145]이 과정은 1900년대 초 식품 산업에서 널리 채택되었습니다; 처음에는 버터와 쇼트닝의 대체물인 마가린의 생산을 위해,[146] 그리고 결국에는 스낵 식품, 포장된 구운 제품, 그리고 기름에 튀긴 제품에 사용되는 다양한 다른 지방들을 위해.[147]

지방이나 기름의 완전 수소화는 완전 포화 지방을 생성합니다.그러나, 수소화는 일반적으로 특정 용융점, 경도 및 기타 특성을 갖는 지방 생성물을 생성하기 위해 완료되기 전에 중단되었습니다.부분 수소화는 이성질화 반응에 의해 시스 이중 결합의 일부를 트랜스 결합으로 바꿉니다.[147][148]트랜스 구성은 낮은 에너지 형태이기 때문에 선호됩니다[citation needed].

이러한 부반응은 오늘날 소비되는 트랜스 지방산의 대부분을 단연코 차지합니다.[149][150]2006년에 몇몇 산업화된 식품을 분석한 결과, 인공단축이 30%, 빵과 케이크 제품이 10%, 쿠키와 크래커가 8%, 짠 과자가 4%, 케이크 프로스팅과 단 것이 7%, 마가린과 기타 가공 스프레드가 26%에 이르는 것으로 나타났습니다.[143]그러나 2010년의 또 다른 분석에서는 마가린과 다른 가공 스프레드의 트랜스 지방이 0.2%에 불과한 것으로 나타났습니다.[151]식물성 지방을 부분적으로 수소화함으로써 형성된 인공 트랜스 지방이 함유된 식품의 총 지방의 최대 45%가 트랜스 지방일 수 있습니다.[141]제빵용 단축제는, 재구성되지 않는 한, 총 지방에 비해 약 30%의 트랜스 지방을 함유하고 있습니다.버터와 같은 고지방 유제품에는 약 4%가 함유되어 있습니다.트랜스 지방을 줄이기 위해 변형되지 않은 마가린은 중량 기준으로 최대 15%의 트랜스 지방을 함유할 수 있지만,[152] 일부 변형된 마가린은 트랜스 지방이 1% 미만입니다.

TFA의 높은 수치는 인기 있는 "패스트푸드" 식사에서 기록되고 있습니다.[150]2004년과 2005년에 수집된 맥도날드의 감자튀김 샘플을 분석한 결과, 뉴욕시에서 제공되는 감자튀김은 트랜스지방이 헝가리보다 두 배나 더 많이 함유되어 있고, 트랜스지방이 제한되어 있는 덴마크보다 28배나 더 많이 함유되어 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.켄터키 프라이드 치킨 제품의 경우, 뉴욕 제품의 트랜스 지방이 두 배 함유된 헝가리 제품의 패턴이 반대였습니다.미국 내에서도 뉴욕의 감자튀김이 애틀랜타의 감자튀김보다 트랜스지방 함량이 30%나 더 많은 등 변이가 있었습니다.[153]

심혈관질환

많은 연구들이 TFA의 섭취가 심혈관 질환의 위험을 높인다는 것을 발견했습니다.[14][5]하버드 공중 보건 학교는 TFA와 포화 지방을 시스 단불포화 지방과 다불포화 지방으로 대체하는 것이 건강에 도움이 된다고 조언합니다.[154]

트랜스 지방을 섭취하는 것은 부분적으로 저밀도 지단백(LDL, 종종 "나쁜 콜레스테롤"이라고 불리는)의 수준을 높이고, 고밀도 지단백(HDL, 종종 "좋은 콜레스테롤"이라고 불리는)의 수준을 낮추고, 혈류의 중성 지방을 증가시키고 전신 염증을 촉진함으로써 관상동맥 질환의 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[155][156]

트랜스지방 섭취에 대해 확인된 주요 건강 위험은 관상동맥질환(CAD)의 위험 상승입니다.[157]1994년의 한 연구는 미국에서 매년 30,000명 이상의 심장 사망이 트랜스 지방의 섭취에 기인한다고 추정했습니다.[158]2006년까지 100,000명의 사망자가 발생할 것으로 예상됩니다.[159]New England Journal of Medicine에 2006년에 발표된 트랜스 지방 연구의 종합적인 리뷰는 트랜스 지방 소비와 CAD 사이의 강력하고 신뢰할 수 있는 연관성을 보고하고, "열량 기준으로, 트랜스 지방은 다른 어떤 다량영양소보다 CAD의 위험을 더 높이는 것으로 보입니다.낮은 수준의 소비(총 에너지 섭취량의 1~3%)에서 상당히 증가된 위험을 제공합니다."[160]

트랜스지방이 CAD에 미치는 영향에 대한 주요 증거는 1976년 시작된 이래 120,000명의 여성 간호사를 추적해온 코호트 연구인 간호사 건강 연구에서 비롯되었습니다.이 연구에서, Hu와 동료들은 14년간의 추적 기간 동안 이 연구의 모집단으로부터 얻은 900개의 관상동맥 사건의 데이터를 분석했습니다.그는 (탄수화물 대신) 섭취한 트랜스지방 칼로리가 2% 증가할 때마다 간호사의 CAD 위험이 약 두 배(상대적 위험도 1.93, CI: 1.43~2.61) 증가한다고 밝혔습니다.반면 포화 지방 칼로리가 5% 증가할 때마다 (탄수화물 칼로리 대신) 위험이 17% 증가했습니다(상대적 위험도 1.17, CI: 0.97~1.41)."포화지방이나 트랜스 불포화지방을 시스(비수화) 불포화지방으로 대체하는 것은 탄수화물에 의한 이성질체 대체보다 더 큰 위험 감소와 관련이 있었습니다."[161]후씨는 트랜스지방 섭취를 줄이는 것의 이점에 대해서도 보고하고 있습니다.트랜스 지방에서 나오는 음식 에너지의 2%를 비트랜스 불포화 지방으로 대체하면 CAD 위험이 절반으로 줄어듭니다(53%).이에 비해 포화 지방에서 나오는 식품 에너지의 5%를 비트랜스 불포화 지방으로 대체하면 CAD의 위험이 43%[161] 감소합니다.

또 다른 연구는 CAD로 인한 사망을 고려했는데, 트랜스 지방의 소비는 사망률의 증가와 연관되어 있고, 다불포화 지방의 소비는 사망률의 감소와 연관되어 있습니다.[157][162]

트랜스 지방은 LDL(나쁜 콜레스테롤)의 혈중 수치를 증가시키는 포화와 같은 역할을 하는 것으로 밝혀졌지만, 포화 지방과 달리 HDL(좋은 콜레스테롤)의 수치도 감소시킵니다.관상동맥 질환의 위험성을 나타내는 일반적인 지표인 트랜스지방과 LDL/HDL 비율의 순 증가는 포화 지방으로 인한 것의 약 두 배입니다.[163][164][165]2003년에 발표된 (상대적으로) 시스와 트랜스 지방이 풍부한 식사의 혈중 지질에 대한 식사 효과를 비교한 무작위 교차 연구에서 콜레스테릴 에스테르 전달(CET)이 시스 식사 후보다 트랜스 식사 후에 28% 더 높았고 트랜스 식사 후 폴리포단백질(a)에서 지질 단백질 농도가 풍부해진 것으로 나타났습니다.[166]

시트로카인 테스트는 여전히 연구 중이지만 CAD 위험성을 나타내는 잠재적으로 더 신뢰할 수 있는 지표입니다.[157]700명 이상의 간호사를 대상으로 한 연구에서 트랜스지방 섭취량이 가장 높은 분위수에 있는 사람들은 가장 낮은 분위수에 있는 사람들보다 73% 더 높은 C-반응 단백질(CRP)의 혈중 수치를 가지고 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[167]

모유수유

인간 모유의 트랜스지방은 산모가 트랜스지방을 섭취함에 따라 변동하며 모유를 먹은 유아의 혈류 속 트랜스지방의 양은 모유에서 발견되는 양에 따라 변동한다는 것이 확인되었습니다.1999년에 보고된 인간 우유의 트랜스 지방(총 지방 대비) 비율은 스페인 1%, 프랑스 2%, 독일 4%, 캐나다와 미국 7%였습니다.[168]

기타 건강상의 위험

트랜스지방 섭취의 부정적인 결과가 심혈관 위험을 넘어선다는 제안들이 있습니다.일반적으로 트랜스지방을 섭취하는 것이 다른 만성적인 건강 문제의 위험을 특별히 증가시킨다고 주장하는 과학적 합의는 훨씬 덜합니다.

- 알츠하이머병:2003년 2월 신경학 기록 보관소에 출판된 한 연구는 동물 모델에서 확인되지는 않았지만 [169]트랜스 지방과 포화 지방의 섭취가 알츠하이머 병의 발병을 촉진한다고 제안했습니다.[170]트랜스지방은 중년 쥐의 기억력과 학습력을 손상시키는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.트랜스 지방을 먹은 쥐의 뇌는 건강한 신경학적 기능에 중요한 단백질이 적었습니다.해마와 주변의 염증, 학습과 기억을 담당하는 뇌의 부분.이것은 알츠하이머가 시작될 때 보통 볼 수 있는 것이지만, 쥐들이 아직 어렸음에도 불구하고 6주 후에 볼 수 있는 정확한 형태의 변화입니다.[171]

- 암: 트랜스 지방을 섭취하는 것이 전반적으로 암 위험을 크게 증가시킨다는 데에는 과학적인 합의가 없습니다.[157]미국 암 협회는 트랜스 지방과 암 사이의 관계가 "결정되지 않았다"고 말합니다.[172]한 연구는 트랜스 지방과 전립선 암 사이의 긍정적인 연관성을 발견했습니다.[173]하지만, 한 대규모 연구에서 트랜스 지방과 고등학교 전립선 암의 현저한 감소 사이의 상관관계를 발견했습니다.[174]트랜스 지방산의 섭취 증가는 유방암의 위험을 75%까지 증가시킬 수 있습니다. 유럽 암과 영양에 대한 프랑스의 전향적 조사의 결과를 암시합니다.[175][176]

- 당뇨병:트랜스지방 섭취에 따라 제2형 당뇨병의 위험이 증가할 것이라는 우려가 커지고 있습니다.[157][177]그러나 합의점을 찾지 못했습니다.[160]예를 들어, 한 연구에서는 트랜스지방 섭취량이 가장 높은 분위수의 사람들에게 위험이 더 높다는 것을 발견했습니다.[178]또 다른 연구에서는 총 지방 섭취량과 체질량 지수와 같은 다른 요인들이 설명되었을 때 당뇨병 위험이 없다는 것을 발견했습니다.[179]

- 비만:트랜스 지방이 비슷한 칼로리 섭취에도 불구하고 체중 증가와 복부 지방을 증가시킬 수 있다는 연구 결과가 나왔습니다.[180]6년간의 실험에서 트랜스지방 식단을 먹은 원숭이는 체중이 7.2% 증가한 것으로 나타났는데, 이는 단일불포화지방 식단을 먹은 원숭이의 체중이 1.8% 증가한 것과 비교됩니다.[181][182]비록 비만이 대중적인 미디어에서 트랜스 지방과 자주 관련이 있지만,[183] 이것은 일반적으로 너무 많은 칼로리를 섭취하는 것과 관련이 있습니다; 비록 6년간의 실험이 "통제된 식사 조건에서,"라는 결론을 내리면서, 트랜스 지방과 비만을 연결하는 강력한 과학적 합의는 없습니다.장기간의 TFA 섭취는 체중 증가의 독립적인 요인이었습니다.TFAs는 열량 과잉이 없는 경우에도 지방의 복부 내 침착을 개선했으며 인슐린 수용체 결합 신호 전달 장애가 있다는 증거와 함께 인슐린 저항성과 관련이 있었습니다."[182]

- 여성의 불임:2007년의 한 연구는 "탄수화물의 에너지 섭취와 대조적으로 트랜스 불포화 지방의 에너지 섭취가 2% 증가할 때마다 73% 더 큰 난소 불임의 위험과 관련이 있었습니다..".[184]

- 주요 우울증: 스페인 연구원들이 6년간 12,059명의 식단을 분석한 결과 트랜스 지방을 가장 많이 먹은 사람들이 트랜스 지방을 먹지 않은 사람들보다 우울증에 걸릴 위험이 48퍼센트나 더 높은 것으로 나타났습니다.[185]하나의 메커니즘은 전두엽 피질(OFC)의 궤도에서 도코사헥사엔산(DHA) 수준에 대한 트랜스 지방의 치환일 수 있습니다.생후 2개월에서 16개월 사이의 쥐에서 트랜스 fatty산(총 지방의 43%)의 매우 높은 섭취는 뇌의 DHA 수준 저하와 관련이 있었습니다(p=0.001).자살을 한 15명의 주요 우울증 피험자의 뇌를 사후 검사하여 27명의 연령 일치 대조군과 비교했을 때 자살 뇌는 OFC에서 DHA가 16%(남성 평균)에서 32%(여성 평균) 적은 것으로 나타났습니다.OFC는 보상, 보상 기대, 공감을 조절하고 변연계를 조절합니다.[186]

- 행동 과민성과 공격성: 이전 연구의 피실험자들에 대한 2012년 관찰 분석은 식이 트랜스지방산과 자가 보고된 행동 공격성과 과민성 사이의 강한 관계를 발견했으며, 이는 인과관계를 시사하지만 확립하지는 않습니다.[187]

- 감소된 메모리:1999-2005 UCSD Statin 연구의 결과를 재분석한 2015년 기사에서 연구원들은 "식이 트랜스 지방산을 더 많이 섭취하는 것은 높은 생산성을 가진 성인들의 단어 기억력이 더 나쁜 것과 연관이 있다, 성인들은 45세 미만입니다.[188]

- 여드름: 2015년 연구에 따르면, 트랜스 지방은 정제 당 또는 정제 녹말과 같은 높은 혈당 부하를 가진 탄수화물, 우유 및 유제품, 포화 지방과 함께 여드름을 촉진하는 서양 패턴 다이어트의 여러 구성 요소 중 하나인 반면, 여드름을 감소시키는 오메가-3 지방산은 서양 패턴 다이어트에서 부족합니다.[189]

생화학적 메커니즘

트랜스 지방이 특정한 건강 문제를 만들어내는 정확한 생화학적 과정은 계속되는 연구의 주제입니다.식이 트랜스지방의 섭취는 필수 지방산(오메가-3을 포함한 EFA)의 대사 능력을 저해하여 동맥벽의 인지질 지방산 구성에 변화를 초래하여 관상동맥 질환의 위험을 높입니다.[190]

트랜스 이중 결합은 플라크 형성에서와 같이 단단한 패킹을 선호하면서 분자에 선형적인 순응을 유도한다고 주장됩니다.대조적으로, 시스 이중 결합의 기하학적 구조는 분자에 굴곡을 형성하고, 그에 따라 단단한 형성을 배제한다고 주장됩니다.[citation needed]

트랜스 지방산이 관상동맥 질환에 기여하는 메커니즘은 상당히 잘 이해되어 있지만 당뇨병에 미치는 영향에 대한 메커니즘은 여전히 연구 중입니다.그들은 긴 사슬의 다불포화 지방산(LCPUFA)의 대사를 손상시킬 수 있습니다.[191]그러나 산모의 임신 트랜스 지방산 섭취는 모유 수유와 지능 사이의 긍정적인 연관성의 기초가 되는 것으로 생각되는 출생 시 유아의 LCPUFA 수치와 역으로 연관되어 있습니다.[192]

트랜스 지방은 다른 지방과 다르게 간에서 처리됩니다.그들은 필수 지방산을 아라키돈산과 프로스타글란딘으로 바꾸는 데 관여하는 효소인 델타 6 데사투라제를 방해함으로써 간 기능 장애를 일으킬 수 있습니다. 이 둘은 세포의 기능에 중요합니다.[193]

유제품에 들어있는 천연 "트랜스 지방"

몇몇 트랜스 지방산은 천연 지방과 전통적으로 가공된 음식에서 발생합니다.백신산은 모유에서 발생하며, 공액 리놀레산(CLA)의 일부 이성질체는 반추동물의 육류 및 유제품에서 발견됩니다.예를 들어, 버터는 트랜스 지방을 약 3% 함유하고 있습니다.[194]

미국 국립 낙농 위원회는 동물성 식품에 존재하는 트랜스 지방은 부분적으로 수소화된 기름에 존재하는 트랜스 지방과는 다른 종류이며 같은 부정적인 영향을 나타내지 않는다고 주장했습니다.[195]한 리뷰는 이 결론에 동의하지만 ("현재 증거의 합계는 반추동물 제품에서 트랜스 지방을 섭취하는 것이 공중 보건에 미치는 영향이 상대적으로 제한적임을 시사한다"는 것) 이것은 동물원에서 나오는 트랜스 지방의 섭취가 인공적인 것에 비해 낮기 때문일 수 있다고 경고합니다.[160]

2008년 메타 분석에 따르면 천연 또는 인공 유래에 관계없이 모든 트랜스 지방은 LDL 수치를 동등하게 높이고 HDL 수치를 낮추는 것으로 나타났습니다.[196]그러나 다른 연구들은 공액 리놀레산과 같은 동물성 트랜스 지방에 관해서는 다른 결과를 보여주었습니다.CLA는 항암효과가 있는 것으로 알려져 있지만, 연구원들은 CLA의 cis-9, trans-11 형태가 심혈관 질환의 위험을 감소시키고 염증과 싸우는 것을 도울 수 있다는 것도 발견했습니다.[197][198]

두 개의 캐나다 연구는 유제품에서 자연적으로 발생하는 TFA인 백신산이 총 LDL과 중성지방 수치를 낮춤으로써 수소화된 식물성 단축 또는 돼지고기 라드와 콩 지방의 혼합물에 비해 도움이 될 수 있다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[199][200][201]미국 농무부의 연구에 따르면 백신산은 HDL 콜레스테롤과 LDL 콜레스테롤을 모두 상승시키는 반면, 산업용 트랜스지방은 HDL에 유익한 영향을 주지 않고 LDL만 상승시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[202]

공식권고

인정된 증거와 과학적 합의를 고려하여, 영양 당국은 모든 트랜스 지방이 건강에 똑같이 해롭다고 생각하고, 그들의 소비량을 미량으로 줄일 것을 권고합니다.[203][204][205][206][207]2003년 WHO는 트랜스지방이 사람의 식단의[141] 0.9% 이하를 차지하도록 권고했고, 2018년에는 산업적으로 생산된 트랜스지방산을 전 세계 식품 공급에서 제거하는 6단계 지침을 도입했습니다.[208]

미국 국립과학원(NAS)은 미국과 캐나다 정부에 공공 정책과 제품 라벨링 프로그램에 사용할 영양학에 대해 조언합니다.에너지, 탄수화물, 섬유질, 지방, 지방산, 콜레스테롤, 단백질, 아미노산에[209] 대한 2002년 식이 기준 섭취량에는 트랜스 지방의 섭취에 대한 그들의 발견과 권장 사항이 포함되어 있습니다.[210]

그들의 권고사항은 두 가지 주요 사실에 근거하고 있습니다.첫째, "트랜스 지방산은 필수적인 것이 아니며 인간의 건강에 알려진 이점을 제공하지 않습니다".[155][211]둘째, LDL/HDL 비율에 대한 문서화된 효과를 고려할 때,[156] NAS는 "식용 트랜스 지방산이 포화 지방산보다 관상 동맥 질환과 관련하여 더 유해하다"고 결론 내렸습니다.뉴잉글랜드 저널 오브 메디신(NEJM)에 발표된 2006년 리뷰는 "영양학적인 관점에서 트랜스 지방산의 섭취는 상당한 잠재적인 해를 끼치지만 명백한 이점은 없다"고 말합니다.[160]

이러한 사실과 우려 때문에 NAS는 안전한 수준의 트랜스 지방 섭취가 없다는 결론을 내렸습니다.트랜스지방에는 적절한 수치, 일일 권장량 또는 허용 상한치가 없습니다.트랜스지방 섭취량이 증가하면 관상동맥 질환의 위험이 높아지기 때문입니다.[156]

이러한 우려에도 불구하고 NAS 식이 권고안에는 트랜스 지방을 식단에서 제거하는 것은 포함되지 않았습니다.트랜스 지방은 많은 동물성 식품에 미량으로 자연적으로 존재하기 때문에 일반적인 식단에서 트랜스 지방을 제거하면 바람직하지 않은 부작용과 영양 불균형을 초래할 수 있기 때문입니다.따라서 NAS는 "영양적으로 적절한 식단을 섭취하면서 트랜스 지방산의 섭취를 가능한 한 적게 할 것을 권장합니다."[212]NAS와 마찬가지로 WHO는 2003년에 트랜스 지방 섭취량을 전체 에너지 섭취량의 1% 미만으로 제한할 것을 권고하면서 공중 보건 목표와 트랜스 지방 섭취량의 균형을 맞추려고 노력해 왔습니다.[141]

규제조치

지난 수십 년 동안, 산업화되고 상업화된 식품의 트랜스지방 함량을 제한하는 많은 국가들에서 상당한 양의 규제가 있었습니다.

수소화 대안

부정적인 대중적 이미지와 엄격한 규제로 인해 부분 수소화 대체에 대한 관심이 높아졌습니다.지방 흥미화에서 지방산은 트리글리세리드의 혼합물 중 하나입니다.기름과 포화 지방의 적절한 혼합에 적용될 때, 아마도 원하지 않는 고체 또는 액체 중성 지방의 분리가 뒤따를 때, 이 과정은 지방산 자체에 영향을 주지 않고 부분적인 수소화의 결과와 유사한 결과를 얻을 수 있을 것입니다. 특히 새로운 "트랜스 지방"을 만들지 않고 말입니다.

수소화는 트랜스지방의 소량 생산만으로도 가능합니다.고압법은 트랜스 지방을 5~6% 함유한 마가린을 생산했습니다.현재 미국의 라벨링 요구 조건(아래 참조)에 따라 제조사는 제품에 트랜스지방이 없다고 주장할 수 있습니다.[213]트랜스 지방의 수준은 수소화 동안 온도와 시간의 변화에 의해서도 변경될 수 있습니다.

기름 (올리브, 콩, 카놀라와 같은), 물, 모노글리세라이드, 그리고 지방산을 섞어서 트랜스지방과 포화지방과 같은 방식으로 작용하는 "조리 지방"을 형성할 수 있습니다.[214][215]

오메가 3 지방산과 오메가 6 지방산

ω-3 지방산은 상당한 관심을 받아왔습니다.오메가-3 지방산 중에서 긴 사슬 형태나 짧은 사슬 형태 모두 유방암 위험과 지속적으로 연관되지 않았습니다.그러나 적혈구 막에서 가장 풍부한 오메가-3 다불포화 지방산인 도코사헥사엔산(DHA)의 높은 수준은 유방암의 위험 감소와 관련이 있었습니다.[135]다불포화 지방산의 섭취를 통해 얻은 DHA는 인지 및 행동 수행과 긍정적으로 연관되어 있습니다.[216]또한, DHA는 망막 자극 및 신경 전달뿐만 아니라 인간 뇌의 회백 물질 구조에도 중요합니다.[128]

흥미화

일부 연구에서는 전체 지방산 구성이 동일한 IE 및 IE가 아닌 지방과 함께 식단을 비교함으로써 관심 있는 (IE) 지방의 건강 효과를 조사했습니다.[217]

인간을 대상으로 한 여러 실험 연구에서는 2-위치에 25-40%의 C16:0 또는 C18:0을 갖는 IE 지방이 많은 식단과 2-위치에 3-9%의 C16:0 또는 C18:0만을 갖는 비 IE 지방이 있는 유사한 식단 간에 공복 혈중 지질에 대한 통계적 차이를 발견하지 못했습니다.[218][219][220]코코아 버터를 모방한 IE 지방 제품과 실제 비IE 제품의 혈중 콜레스테롤 수치에 미치는 영향을 비교한 연구에서도 부정적인 결과가 나왔습니다.[221][222][223][224][225][226][227]

말레이시아 팜 오일 위원회가[228] 자금을 지원한 2007년의 연구는 천연 팜유를 다른 흥미로운 또는 부분적으로 수소화된 지방으로 대체하는 것이 더 높은 LDL/HDL 비율과 혈장 포도당 수치와 같은 건강에 악영향을 초래한다고 주장했습니다.그러나 이러한 효과는 IE 프로세스 자체보다는 IE에서 포화 산과 부분적으로 수소화된 지방의 비율이 높기 때문일 수 있습니다.[229][230]

질병의 역할

인체에서 혈류 속의 높은 수치의 중성지방은 죽상동맥경화증, 심장병[231], 뇌졸중과 관련이 있습니다.[9]그러나 LDL과 비교할 때 중성지방의 증가된 수치가 미치는 상대적인 부정적인 영향:HDL 비율은 아직 알려지지 않았습니다.위험은 중성지방 수치와 HDL-콜레스테롤 수치 사이의 강한 역관계에 의해 부분적으로 설명될 수 있습니다.그러나 위험은 또한 높은 중성지방 수치가 작고 밀도가 높은 LDL 입자의 양을 증가시키기 때문입니다.[232]

가이드라인

국립 콜레스테롤 교육 프로그램은 중성지방 수치에 대한 지침을 세웠습니다.[233][234]

| 레벨 | 해석 | |

|---|---|---|

| (mg/dL) | (mmol/L) | |

| < 150 | < 1.70 | 정상 범위 – 저위험 |

| 150–199 | 1.70–2.25 | 정상보다 약간 높음 |

| 200–499 | 2.26–5.65 | 약간의 위험 |

| 500 이상 | > 5.65 | 매우 높음 – 위험도 높음 |

이 수치들은 8시간에서 12시간 정도 금식한 후에 테스트됩니다.중성지방 수치는 식사 후에도 일시적으로 더 높은 수치를 유지합니다.

AHA는 심장 건강을 개선하기 위해 100mg/dL(1.1mmol/L) 이하의 최적 중성지방 수치를 권장합니다.[235]

중성지방 수치 감소

체중 감량과 식이 조절은 고중성지방혈증의 효과적인 1차 생활습관교정 치료입니다.[236]중성지방 수치가 경미하거나 중간 정도 높은 사람들에게는 체중 감량, 적당한[237][238] 운동 및 식이 조절을 포함한 생활 방식의 변화가 권장됩니다.[239]이것은 식단에서 탄수화물(특히 과당)[236]과 지방의 제한과 조류, 견과류, 생선, 씨앗에서 나오는 오메가-3 지방산의[238] 섭취를 포함할 수 있습니다.[240]앞서 언급한 생활 방식 변경으로 보정되지 않은 중성지방 수치가 높은 사람에게는 약물이 권장되며, 섬유질이 우선적으로 권장됩니다.[239][241][242]오메가-3-카르복실산은 매우 높은 수준의 혈중 중성지방을 치료하는데 사용되는 또 다른 처방약입니다.[243]

약물로 고중성지방혈증을 치료하는 결정은 수준과 심혈관 질환의 다른 위험인자의 유무에 따라 달라집니다.췌장염의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있는 매우 높은 수치는 섬유질 부류의 약물로 치료됩니다.심혈관 위험 감소가 필요할 때 스타틴 등급의 약물뿐만 아니라 나이아신과 오메가-3 지방산도 스타틴 등급의 약물과 함께 사용될 수 있습니다.[239]

지방소화 및 대사

지방은 건강한 몸에서 분해되어 그들의 성분인 글리세롤과 지방산을 배출합니다.글리세롤 자체가 간에 의해 포도당으로 전환되어 에너지원이 될 수 있습니다.지방과 다른 지방질은 췌장에서 생성되는 리파아제라고 불리는 효소에 의해 몸에서 분해됩니다.

많은 세포 유형들은 신진대사를 위한 에너지원으로 포도당이나 지방산을 사용할 수 있습니다.특히 심장과 골격근은 지방산을 선호합니다.[citation needed]오랜 반대의 주장에도 불구하고, 지방산은 미토콘드리아 산화를 통해 뇌세포의 연료로 사용될 수도 있습니다.[244]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d "뚱뚱한" 항목 온라인 메리엄-웹스터 사전의 웨이백 머신에서 보관 2020-07-25, 센스 3.22020-08-09년 접속

- ^ a b c Thomas A. B. Sanders (2016): "인간 식단에서 지방의 역할"기능성 식이 지질 1-20페이지우드헤드/엘세비어, 332페이지 ISBN978-1-78242-247-1 Doi:10.1016/B978-1-78242-247-1.00001-6

- ^ "Macronutrients: the Importance of Carbohydrate, Protein, and Fat". McKinley Health Center. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Introduction to Energy Storage". Khan Academy.

- ^ a b c 영국 정부(1996): "일정 7: Wayback Machine에서 2013-03-17 영양 라벨 보관".1996년 식품 라벨링 규정 웨이백 머신에서 보관 2013-09-21.2020-08-09 접속.

- ^ Wu, Yang; Zhang, Aijun; Hamilton, Dale J.; Deng, Tuo (2017). "Epicardial Fat in the Maintenance of Cardiovascular Health". Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 13 (1): 20–24. doi:10.14797/mdcj-13-1-20. ISSN 1947-6094. PMC 5385790. PMID 28413578.

- ^ "The human proteome in adipose - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- ^ White, Hayden; Venkatesh, Balasubramanian (2011). "Clinical review: Ketones and brain injury". Critical Care. 15 (2): 219. doi:10.1186/cc10020. PMC 3219306. PMID 21489321.

- ^ a b Drummond, K. E.; Brefere, L. M. (2014). Nutrition for Foodservice and Culinary Professionals (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-05242-6.

- ^ 레베카 J. 도나텔 (2005):건강, 더 베이직, 6판.Pearson Education, San Francisco; ISBN 978-0-13-120687-8

- ^ 프랭크 B.후, 조앤 E. 맨슨, 월터 C.윌렛(2001):"식용지방의 종류와 관상동맥성 심장질환의 위험:비판적인 리뷰."미국 영양대학 저널 20권 1호 5-19페이지. Doi:10.1080/07315724.2001.10719008

- ^ 이 후퍼, 캐롤린 D.서머벨, 줄리안 P.T. 히긴스, 레이첼 L.톰슨, 나이젤 E. 캡스, 조지 데이비 스미스, 루돌프 A.리메르스마, 그리고 샤 에브라힘 (2001):"다이어트 지방 섭취와 심혈관 질환 예방: 체계적 검토"BMJ, 권 322, 757-.doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7289.757

- ^ 조지 A.브레이, 사하스폰 패라타쿨, 배리 M.Popkin (2004): "식용 지방과 비만: 동물, 임상 및 역학 연구 검토"Physiology & Behavior, 제83권, 제4호, 549-555페이지. Doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.039

- ^ a b 다리우쉬 모자파리안, 마르틴 B.카탄, 알베르토 아셰리오, 메이르 J. 스탬퍼, 월터 C.Willett (2006): "트랜스 지방산과 심혈관 질환".New England Journal of Medicine, 354권 15호 1601-1613페이지. Doi:10.1056/NEJMra054035 PMID 16611951

- ^ a b c "US National Nutrient Database, Release 28". United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. 이 표의 모든 값은 별도로 인용되거나 다른 성분 열의 단순 산술 합으로 기울어지지 않는 한 이 데이터베이스에서 가져온 것입니다.

- ^ Nutritiondata.com (SR 21)의 값은 2017년 9월 현재 USDA SR 28의 가장 최근 릴리스와 일치해야 할 수 있습니다.

- ^ "USDA Specifications for Vegetable Oil Margarine Effective August 28, 1996" (PDF).

- ^ "Avocado oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Ozdemir F, Topuz A (2004). "Changes in dry matter, oil content and fatty acids composition of avocado during harvesting time and post-harvesting ripening period" (PDF). Food Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 79–83. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-16. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ Wong M, Requejo-Jackman C, Woolf A (April 2010). "What is unrefined, extra virgin cold-pressed avocado oil?". Aocs.org. The American Oil Chemists' Society. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "Brazil nut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Katragadda HR, Fullana A, Sidhu S, Carbonell-Barrachina ÁA (2010). "Emissions of volatile aldehydes from heated cooking oils". Food Chemistry. 120: 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.070.

- ^ "Canola oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Wolke RL (May 16, 2007). "Where There's Smoke, There's a Fryer". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ "Coconut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Corn oil, industrial and retail, all purpose salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Cottonseed oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Cottonseed oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Linseed/Flaxseed oil, cold pressed, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Garavaglia J, Markoski MM, Oliveira A, Marcadenti A (2016). "Grape Seed Oil Compounds: Biological and Chemical Actions for Health". Nutrition and Metabolic Insights. 9: 59–64. doi:10.4137/NMI.S32910. PMC 4988453. PMID 27559299.

- ^ Callaway J, Schwab U, Harvima I, Halonen P, Mykkänen O, Hyvönen P, Järvinen T (April 2005). "Efficacy of dietary hempseed oil in patients with atopic dermatitis". The Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 16 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1080/09546630510035832. PMID 16019622. S2CID 18445488.

- ^ Melina V. "Smoke points of oils" (PDF). veghealth.com. The Vegetarian Health Institute.

- ^ "Safflower oil, salad or cooking, high oleic, primary commerce, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Olive oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Palm oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Palm oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, filling fat, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Oil, peanut". FoodData Central. usda.gov.

- ^ Orthoefer FT (2005). "Chapter 10: Rice Bran Oil". In Shahidi F (ed.). Bailey's Industrial Oil and Fat Products. Vol. 2 (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 465. doi:10.1002/047167849X. ISBN 978-0-471-38552-3.

- ^ "Rice bran oil". RITO Partnership. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Oil, sesame, salad or cooking". FoodData Central. fdc.nal.usda.gov. 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, (partially hydrogenated), fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "FoodData Central". fdc.nal.usda.gov.

- ^ "Walnut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "Smoke Point of Oils". Baseline of Health. Jonbarron.org.

- ^ "Saturated fats". American Heart Association. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Top food sources of saturated fat in the US". Harvard University School of Public Health. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fats". choosemyplate.gov. 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-15. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ^ Reece, Jane; Campbell, Neil (2002). Biology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2.

- ^ "What are "oils"?". ChooseMyPlate.gov, US Department of Agriculture. 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G (June 2015). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737. PMID 26068959.

- ^ Hooper, L; Martin, N; Jimoh, OF; Kirk, C; Foster, E; Abdelhamid, AS (21 August 2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. PMC 8092457. PMID 32827219.

- ^ a b c d e f Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV (July 2017). "Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (3): e1–e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. PMID 28620111. S2CID 367602.

- ^ "Healthy diet Fact sheet N°394". May 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ 세계보건기구:식품피라미드(영양)

- ^ "Fats explained" (PDF). HEART UK – The Cholesterol Charity. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-21. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Live Well, Eat well, Fat: the facts". NHS. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Fat: the facts". United Kingdom's National Health Service. 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "How to eat less saturated fat - NHS". nhs.uk. April 27, 2018.

- ^ "Fats explained - types of fat BHF".

- ^ "Key Recommendations: Components of Healthy Eating Patterns". Dietary Guidelines 2015-2020. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Cut Down on Saturated Fats" (PDF). United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Trends in Intake of Energy, Protein, Carbohydrate, Fat, and Saturated Fat — United States, 1971–2000". Centers for Disease Control. 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01.

- ^ "Dietary Guidelines for Americans" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. 2005.

- ^ "Dietary Guidelines for Indians - A Manual" (PDF). Indian Council of Medical Research, National Institute of Nutrition. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ "Health Diet". India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Archived from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Choosing foods with healthy fats". Health Canada. 2018-10-10. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Fat". Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council and Department of Health and Ageing. 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Getting the Fats Right!". Singapore's Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults" (PDF). New Zealand's Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Know More about Fat". Hong Kong's Department of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ German JB, Dillard CJ (September 2004). "Saturated fats: what dietary intake?". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (3): 550–559. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.3.550. PMID 15321792.

- ^ a b Storlien LH, Baur LA, Kriketos AD, Pan DA, Cooney GJ, Jenkins AB, et al. (June 1996). "Dietary fats and insulin action". Diabetologia. 39 (6): 621–31. doi:10.1007/BF00418533. PMID 8781757. S2CID 33171616.

- ^ a b c d Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (WHO technical report series 916) (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 81–94. ISBN 978-92-4-120916-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-04-21. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ Zelman K (2011). "The Great Fat Debate: A Closer Look at the Controversy—Questioning the Validity of Age-Old Dietary Guidance". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (5): 655–658. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026. PMID 21515106.

- ^ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-03-07). "Health Claim Notification for Saturated Fat, Cholesterol, and Trans Fat, and Reduced Risk of Heart Disease". FDA.

- ^ Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, Franklin B, Kris-Etherton P, Harris WS, Howard B, Karanja N, Lefevre M, Rudel L, Sacks F, Van Horn L, Winston M, Wylie-Rosett J (July 2006). "Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee". Circulation. 114 (1): 82–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. PMID 16785338. S2CID 647269.

- ^ Smith SC, Jackson R, Pearson TA, Fuster V, Yusuf S, Faergeman O, Wood DA, Alderman M, Horgan J, Home P, Hunn M, Grundy SM (June 2004). "Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum" (PDF). Circulation. 109 (25): 3112–21. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67. PMID 15226228.

- ^ Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, Sofi F (January 2018). "Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (1): 30–43. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2017.58. hdl:2158/1081996. PMID 28488692. S2CID 7702206.

- ^ Martinez-Lacoba R, Pardo-Garcia I, Amo-Saus E, Escribano-Sotos F (October 2018). "Mediterranean diet and health outcomes: a systematic meta-review". European Journal of Public Health. 28 (5): 955–961. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky113. PMID 29992229.

- ^ Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, Majchrzak-Hong SF, Faurot KR, Suchindran CM, Ringel A, Davis JM, Hibbeln JR (February 2013). "Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis". BMJ. 346: e8707. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8707. PMC 4688426. PMID 23386268.

- ^ Interview: Walter Willett (2017). "Research Review: Old data on dietary fats in context with current recommendations: Comments on Ramsden et al. in the British Medical Journal". TH Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, Cozma AI, Ha V, Kishibe T, Uleryk E, Budylowski P, Schünemann H, Beyene J, Anand SS (August 2015). "Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". BMJ. 351 (Aug 11): h3978. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3978. PMC 4532752. PMID 26268692.

- ^ Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, Majchrzak-Hong SF, Faurot KR, Suchindran CM, et al. (February 2013). "Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis". BMJ. 346: e8707. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8707. PMC 4688426. PMID 23386268.

- ^ Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Majchrzak-Hong S, Faurot KR, Broste SK, Frantz RP, Davis JM, Ringel A, Suchindran CM, Hibbeln JR (April 2016). "Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73)". BMJ. 353: i1246. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1246. PMC 4836695. PMID 27071971.

- ^ Weylandt KH, Serini S, Chen YQ, Su HM, Lim K, Cittadini A, Calviello G (2015). "Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: The Way Forward in Times of Mixed Evidence". BioMed Research International. 2015: 143109. doi:10.1155/2015/143109. PMC 4537707. PMID 26301240.

- ^ a b Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS (2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 5 (5): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7388853. PMID 32428300.

- ^ Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, et al. (2007). "European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary". European Heart Journal. 28 (19): 2375–2414. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. PMID 17726041.

- ^ Labarthe D (2011). "Chapter 17 What Causes Cardiovascular Diseases?". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ^ Kris-Etherton PM, Innis S (September 2007). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Dietary Fatty Acids". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 107 (9): 1599–1611 [1603]. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.024. PMID 17936958.

- ^ "Food Fact Sheet - Cholesterol" (PDF). British Dietetic Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-11-22. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors". World Heart Federation. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Lower your cholesterol". National Health Service. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Nutrition Facts at a Glance - Nutrients: Saturated Fat". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol". European Food Safety Authority. 2010-03-25. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom. "Position Statement on Fat" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ^ Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). "Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ^ "Cholesterol". Irish Heart Foundation. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (December 2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (PDF) (7th ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Cannon C, O'Gara P (2007). Critical Pathways in Cardiovascular Medicine (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 243.

- ^ Catapano AL, Reiner Z, De Backer G, Graham I, Taskinen MR, Wiklund O, et al. (July 2011). "ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)". Atherosclerosis. 217 Suppl 1 (14): S1-44. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.06.012. hdl:10138/307445. PMID 21723445.

- ^ "Monounsaturated Fat". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- ^ "You Can Control Your Cholesterol: A Guide to Low-Cholesterol Living". MerckSource. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ Sanchez-Bayle M, Gonzalez-Requejo A, Pelaez MJ, Morales MT, Asensio-Anton J, Anton-Pacheco E (February 2008). "A cross-sectional study of dietary habits and lipid profiles. The Rivas-Vaciamadrid study". European Journal of Pediatrics. 167 (2): 149–54. doi:10.1007/s00431-007-0439-6. PMID 17333272. S2CID 8798248.

- ^ Clarke R, Frost C, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R (1997). "Dietary lipids and blood cholesterol: quantitative meta-analysis of metabolic ward studies". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 314 (7074): 112–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7074.112. PMC 2125600. PMID 9006469.

- ^ Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH (February 1999). "Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 19 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1161/01.atv.19.2.187. PMID 9974397.

- ^ a b Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058. S2CID 54293528.

- ^ Labarthe D (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2 ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ^ Labarthe D (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- ^ Thijssen MA, Mensink RP (2005). "Fatty acids and atherosclerotic risk". Atherosclerosis: Diet and Drugs. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 170. Springer. pp. 165–94. doi:10.1007/3-540-27661-0_5. ISBN 978-3-540-22569-0. PMID 16596799.

- ^ Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S (November 2003). "Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature". British Journal of Cancer. 89 (9): 1672–1685. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601314. PMC 2394401. PMID 14583769.

- ^ a b Hanf V, Gonder U (2005-12-01). "Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 123 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.05.011. PMID 16316809.

- ^ Lof M, Weiderpass E (February 2009). "Impact of diet on breast cancer risk". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 21 (1): 80–85. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32831d7f22. PMID 19125007. S2CID 9513690.

- ^ Freedman LS, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Potischman N (Mar–Apr 2008). "Methods of Epidemiology: Evaluating the Fat–Breast Cancer Hypothesis – Comparing Dietary Instruments and Other Developments". Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.). 14 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31816a5e02. PMC 2496993. PMID 18391610.

- ^ Lin OS (2009). "Acquired risk factors for colorectal cancer". Cancer Epidemiology. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 472. pp. 361–72. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_16. ISBN 978-1-60327-491-3. PMID 19107442.

- ^ Huncharek M, Kupelnick B (2001). "Dietary fat intake and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis of 6,689 subjects from 8 observational studies". Nutrition and Cancer. 40 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1207/S15327914NC402_2. PMID 11962260. S2CID 24890525.

- ^ a b Männistö S, Pietinen P, Virtanen MJ, Salminen I, Albanes D, Giovannucci E, Virtamo J (December 2003). "Fatty acids and risk of prostate cancer in a nested case-control study in male smokers". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 12 (12): 1422–8. PMID 14693732.

- ^ a b c Crowe FL, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Overvad K, Aardestrup IV, Johnsen NF, Tjønneland A, Linseisen J, Kaaks R, Boeing H, Kröger J, Trichopoulou A, Zavitsanou A, Trichopoulos D, Sacerdote C, Palli D, Tumino R, Agnoli C, Kiemeney LA, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, Larrañaga N, Quirós JR, Sánchez MJ, González CA, Stattin P, Hallmans G, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Rinaldi S, Slimani N, Jenab M, Riboli E, Key TJ (November 2008). "Fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids and risk of prostate cancer in a case-control analysis nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (5): 1353–63. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26369. PMID 18996872.

- ^ a b Kurahashi N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane AS (April 2008). "Dairy product, saturated fatty acid, and calcium intake and prostate cancer in a prospective cohort of Japanese men". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 17 (4): 930–7. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2681. PMID 18398033. S2CID 551427.

- ^ Corwin RL, Hartman TJ, Maczuga SA, Graubard BI (2006). "Dietary saturated fat intake is inversely associated with bone density in humans: Analysis of NHANES III". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (1): 159–165. doi:10.1093/jn/136.1.159. PMID 16365076. S2CID 4443420.

- ^ Kien CL, Bunn JY, Tompkins CL, Dumas JA, Crain KI, Ebenstein DB, Koves TR, Muoio DM (April 2013). "Substituting dietary monounsaturated fat for saturated fat is associated with increased daily physical activity and resting energy expenditure and with changes in mood". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 97 (4): 689–97. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.051730. PMC 3607650. PMID 23446891.

- ^ Abdullah MM, Jew S, Jones PJ (February 2017). "Health benefits and evaluation of healthcare cost savings if oils rich in monounsaturated fatty acids were substituted for conventional dietary oils in the United States". Nutrition Reviews. 75 (3): 163–174. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuw062. PMC 5914363. PMID 28158733.

- ^ Huth PJ, Fulgoni VL, Larson BT (November 2015). "A systematic review of high-oleic vegetable oil substitutions for other fats and oils on cardiovascular disease risk factors: implications for novel high-oleic soybean oils". Advances in Nutrition. 6 (6): 674–93. doi:10.3945/an.115.008979. PMC 4642420. PMID 26567193.

- ^ Shute, Nancy (2012-05-02). "Lard Is Back In The Larder, But Hold The Health Claims". NPR. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ^ Fat content and composition of animal products: proceedings of a symposium, Washington, D.C., December 12-13, 1974. Washington: National Academy of Sciences. 1976. ISBN 978-0-309-02440-2. PMID 25032409.

- ^ "Ask the Expert: Concerns about canola oil". The Nutrition Source. 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola O, Ormazabal M, Vallejo A, Olivares M, Navarro P, Etxebarria N, Usobiaga A (January 2015). "Optimization of supercritical fluid consecutive extractions of fatty acids and polyphenols from Vitis vinifera grape wastes". Journal of Food Science. 80 (1): E101-7. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12715. PMID 25471637.

- ^ a b c d e "Essential Fatty Acids". Micronutrient Information Center, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "National nutrient database for standard reference, release 23". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ "Vegetable oil, avocado Nutrition Facts & Calories". nutritiondata.self.com.

- ^ "United States Department of Agriculture – National Nutrient Database". 8 September 2015. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

- ^ Vessby B, Uusitupa M, Hermansen K, Riccardi G, Rivellese AA, Tapsell LC, Nälsén C, Berglund L, Louheranta A, Rasmussen BM, Calvert GD, Maffetone A, Pedersen E, Gustafsson IB, Storlien LH (March 2001). "Substituting dietary saturated for monounsaturated fat impairs insulin sensitivity in healthy men and women: The KANWU Study". Diabetologia. 44 (3): 312–9. doi:10.1007/s001250051620. PMID 11317662.

- ^ Lovejoy JC (October 2002). "The influence of dietary fat on insulin resistance". Current Diabetes Reports. 2 (5): 435–40. doi:10.1007/s11892-002-0098-y. PMID 12643169. S2CID 31329463.

- ^ Fukuchi S, Hamaguchi K, Seike M, Himeno K, Sakata T, Yoshimatsu H (June 2004). "Role of fatty acid composition in the development of metabolic disorders in sucrose-induced obese rats". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 229 (6): 486–93. doi:10.1177/153537020422900606. PMID 15169967. S2CID 20966659.

- ^ a b Pala V, Krogh V, Muti P, Chajès V, Riboli E, Micheli A, Saadatian M, Sieri S, Berrino F (July 2001). "Erythrocyte membrane fatty acids and subsequent breast cancer: a prospective Italian study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 93 (14): 1088–95. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.14.1088. PMID 11459870.

- ^ a b "Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Health: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". US National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. 2 November 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Newman VA, Natarajan L, Rock CL, Thomson CA, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Pierce JP (February 2011). "Marine fatty acid intake is associated with breast cancer prognosis". The Journal of Nutrition. 141 (2): 201–6. doi:10.3945/jn.110.128777. PMC 3021439. PMID 21178081.

- ^ Martin CA, Milinsk MC, Visentainer JV, Matsushita M, de-Souza NE (June 2007). "Trans fatty acid-forming processes in foods: a review". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 79 (2): 343–50. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652007000200015. PMID 17625687.

- ^ Kuhnt K, Baehr M, Rohrer C, Jahreis G (October 2011). "Trans fatty acid isomers and the trans-9/trans-11 index in fat containing foods". European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 113 (10): 1281–1292. doi:10.1002/ejlt.201100037. PMC 3229980. PMID 22164125.

- ^ Kummerow, Fred August; Kummerow, Jean M. (2008). Cholesterol Won't Kill You, But Trans Fat Could. Trafford. ISBN 978-1-4251-3808-0.

- ^ a b c d e Trans Fat Task Force (June 2006). TRANSforming the Food Supply. Trans Fat Task Force. ISBN 0-662-43689-X. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ "DIETA DETOX ✅ QUÉ ES Y SUS 13 PODEROSOS BENEFICIOS". October 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Tarrago-Trani MT, Phillips KM, Lemar LE, Holden JM (June 2006). "New and existing oils and fats used in products with reduced trans-fatty acid content". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 106 (6): 867–80. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.010. PMID 16720128.

- ^ Menaa F, Menaa A, Menaa B, Tréton J (June 2013). "Trans-fatty acids, dangerous bonds for health? A background review paper of their use, consumption, health implications and regulation in France". European Journal of Nutrition. 52 (4): 1289–302. doi:10.1007/s00394-012-0484-4. PMID 23269652. S2CID 206968361.

- ^ "Wilhelm Normann und die Geschichte der Fetthärtung von Martin Fiedler, 2001". 20 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ^ Gormley JJ, Juturu V (2010). "Partially Hydrogenated Fats in the US Diet and Their Role in Disease". In De Meester F, Zibadi S, Watson RR (eds.). Modern Dietary Fat Intakes in Disease Promotion. Nutrition and Health. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 85–94. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-571-2_5. ISBN 978-1-60327-571-2.

- ^ a b "Tentative Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils". Federal Register. 8 November 2013. 2013-26854, Vol. 78, No. 217. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Hill JW, Kolb DK (2007). Chemistry for changing times. Pearson / Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-605449-8.

- ^ Ashok C, Ajit V (2009). "Chapter 4: Fatty acids". A Textbook of Molecular Biotechnology. I. K. International Pvt. p. 181. ISBN 978-93-80026-37-4.

- ^ a b Valenzuela A, Morgado N (1999). "Trans fatty acid isomers in human health and in the food industry". Biological Research. 32 (4): 273–87. doi:10.4067/s0716-97601999000400007. PMID 10983247.

- ^ "Heart Foundation: Butter has 20 times the trans fats of marg Australian Food News". www.ausfoodnews.com.au.

- ^ Hunter JE (2005). "Dietary levels of trans fatty acids" basis for health concerns and industry efforts to limit use". Nutrition Research. 25 (5): 499–513. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2005.04.002.

- ^ "What's in that french fry? Fat varies by city". NBC News. 12 April 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2007. AP 관련 기사

- ^ "지방과 콜레스테롤" 2016-11-18 하버드 공중 보건 학교 웨이백 머신에서 보관.02-11-16 검색.

- ^ a b Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients). National Academies Press. pp. 423. doi:10.17226/10490. ISBN 978-0-309-08525-0.

- ^ a b c Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 504.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ a b c d e Trans Fat Task Force (June 2006). "Appendix 9iii)". TRANSforming the Food Supply. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007. (트랜스 지방산에 대한 대체물의 건강적 의미에 대한 협의:전문가 응답내용 요약)

- ^ Willett WC, Ascherio A (May 1994). "Trans fatty acids: are the effects only marginal?". American Journal of Public Health. 84 (5): 722–4. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.5.722. PMC 1615057. PMID 8179036.

- ^ Zaloga GP, Harvey KA, Stillwell W, Siddiqui R (October 2006). "Trans fatty acids and coronary heart disease". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 21 (5): 505–12. doi:10.1177/0115426506021005505. PMID 16998148.

- ^ a b c d Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (April 2006). "Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (15): 1601–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054035. PMID 16611951. S2CID 35121566.

- ^ a b Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm E, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, et al. (November 1997). "Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women". The New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (21): 1491–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199711203372102. PMID 9366580.

- ^ Oh K, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (April 2005). "Dietary fat intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women: 20 years of follow-up of the nurses' health study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 161 (7): 672–9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi085. PMID 15781956.

- ^ Ascherio A, Katan MB, Zock PL, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (June 1999). "Trans fatty acids and coronary heart disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (25): 1994–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906243402511. PMID 10379026. S2CID 30165590.

- ^ Mensink RP, Katan MB (August 1990). "Effect of dietary trans fatty acids on high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in healthy subjects". The New England Journal of Medicine. 323 (7): 439–45. doi:10.1056/NEJM199008163230703. PMID 2374566.

- ^ Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester AD, Katan MB (May 2003). "Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 77 (5): 1146–55. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146. PMID 12716665.

- ^ Gatto LM, Sullivan DR, Samman S (May 2003). "Postprandial effects of dietary trans fatty acids on apolipoprotein(a) and cholesteryl ester transfer". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 77 (5): 1119–24. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1119. PMID 12716661.

- ^ Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Meigs JB, Manson JE, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, et al. (March 2005). "Consumption of trans fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (3): 562–6. doi:10.1093/jn/135.3.562. PMID 15735094.

- ^ Innis SM, King DJ (September 1999). "trans Fatty acids in human milk are inversely associated with concentrations of essential all-cis n-6 and n-3 fatty acids and determine trans, but not n-6 and n-3, fatty acids in plasma lipids of breast-fed infants". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 70 (3): 383–90. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.3.383. PMID 10479201.

- ^ Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney CC, Bennett DA, Aggarwal N, et al. (February 2003). "Dietary fats and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease". Archives of Neurology. 60 (2): 194–200. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.2.194. PMID 12580703.

- ^ a b Phivilay A, Julien C, Tremblay C, Berthiaume L, Julien P, Giguère Y, Calon F (March 2009). "High dietary consumption of trans fatty acids decreases brain docosahexaenoic acid but does not alter amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in the 3xTg-AD model of Alzheimer's disease". Neuroscience. 159 (1): 296–307. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.006. PMID 19135506. S2CID 35748183.

- ^ Granholm AC, Bimonte-Nelson HA, Moore AB, Nelson ME, Freeman LR, Sambamurti K (June 2008). "Effects of a saturated fat and high cholesterol diet on memory and hippocampal morphology in the middle-aged rat". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 14 (2): 133–45. doi:10.3233/JAD-2008-14202. PMC 2670571. PMID 18560126.

- ^ American Cancer Society. "Common questions about diet and cancer". Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Chavarro J, Stampfer M, Campos H, Kurth T, Willett W, Ma J (1 April 2006). "A prospective study of blood trans fatty acid levels and risk of prostate cancer". Proc. Amer. Assoc. Cancer Res. 47 (1): 943. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Brasky TM, Till C, White E, Neuhouser ML, Song X, Goodman P, et al. (June 2011). "Serum phospholipid fatty acids and prostate cancer risk: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial". American Journal of Epidemiology. 173 (12): 1429–39. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr027. PMC 3145396. PMID 21518693.

- ^ "Breast cancer: a role for trans fatty acids?". World Health Organization (Press release). 11 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008.

- ^ Chajès V, Thiébaut AC, Rotival M, Gauthier E, Maillard V, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. (June 2008). "Association between serum trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in the E3N-EPIC Study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 167 (11): 1312–20. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn069. PMC 2679982. PMID 18390841.

- ^ Riserus U (2006). "Trans fatty acids, insulin sensitivity and type 2 diabetes". Scandinavian Journal of Food and Nutrition. 50 (4): 161–165. doi:10.1080/17482970601133114.

- ^ Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S (July 2001). "Diet and risk of Type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate". Diabetologia. 44 (7): 805–17. doi:10.1007/s001250100547. PMID 11508264.

- ^ van Dam RM, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB (March 2002). "Dietary fat and meat intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men". Diabetes Care. 25 (3): 417–24. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.3.417. PMID 11874924.

- ^ Gosline A (12 June 2006). "Why fast foods are bad, even in moderation". New Scientist. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ "Six years of fast-food fats supersizes monkeys". New Scientist (2556): 21. 17 June 2006.

- ^ a b Kavanagh K, Jones KL, Sawyer J, Kelley K, Carr JJ, Wagner JD, Rudel LL (July 2007). "Trans fat diet induces abdominal obesity and changes in insulin sensitivity in monkeys". Obesity. 15 (7): 1675–84. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.200. PMID 17636085. S2CID 4835948.

- ^ Thompson TG. "Trans Fat Press Conference". Archived from the original on 9 July 2006.Thompson TG. "Trans Fat Press Conference". Archived from the original on 9 July 2006.미국 보건복지부 장관

- ^ Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Rosner BA, Willett WC (January 2007). "Dietary fatty acid intakes and the risk of ovulatory infertility". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (1): 231–7. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.1.231. PMID 17209201.

- ^ Roan S (28 January 2011). "Trans fats and saturated fats could contribute to depression". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ McNamara RK, Hahn CG, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Stanford KE, Richtand NM (July 2007). "Selective deficits in the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid in the postmortem orbitofrontal cortex of patients with major depressive disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.026. PMID 17188654. S2CID 32898004.

- ^ Golomb BA, Evans MA, White HL, Dimsdale JE (2012). "Trans fat consumption and aggression". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e32175. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732175G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032175. PMC 3293881. PMID 22403632.

- ^ Golomb BA, Bui AK (2015). "A Fat to Forget: Trans Fat Consumption and Memory". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0128129. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1028129G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128129. PMC 4470692. PMID 26083739.

- ^ Melnik BC (15 July 2015). Weinberg J (ed.). "Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update". Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 8: 371–88. doi:10.2147/CCID.S69135. PMC 4507494. PMID 26203267.

- ^ Kummerow FA, Zhou Q, Mahfouz MM, Smiricky MR, Grieshop CM, Schaeffer DJ (April 2004). "Trans fatty acids in hydrogenated fat inhibited the synthesis of the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the phospholipid of arterial cells". Life Sciences. 74 (22): 2707–23. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.013. PMID 15043986.

- ^ Mojska H (2003). "Influence of trans fatty acids on infant and fetus development". Acta Microbiologica Polonica. 52 Suppl: 67–74. PMID 15058815.

- ^ Koletzko B, Decsi T (October 1997). "Metabolic aspects of trans fatty acids". Clinical Nutrition. 16 (5): 229–37. doi:10.1016/s0261-5614(97)80034-9. PMID 16844601.

- ^ Mahfouz M (1981). "Effect of dietary trans fatty acids on the delta 5, delta 6 and delta 9 desaturases of rat liver microsomes in vivo". Acta Biologica et Medica Germanica. 40 (12): 1699–1705. PMID 7345825.

- ^ "National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 28". United States Department of Agriculture.[데드링크]

- ^ National Dairy Council (18 June 2004). "comments on 'Docket No. 2003N-0076 Food Labeling: Trans Fatty Acids in Nutrition Labeling'" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-16. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ Brouwer IA, Wanders AJ, Katan MB (March 2010). Reitsma PH (ed.). "Effect of animal and industrial trans fatty acids on HDL and LDL cholesterol levels in humans--a quantitative review". PLOS ONE. 5 (3): e9434. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9434B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009434. PMC 2830458. PMID 20209147.

- ^ Tricon S, Burdge GC, Kew S, Banerjee T, Russell JJ, Jones EL, et al. (September 2004). "Opposing effects of cis-9,trans-11 and trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid on blood lipids in healthy humans". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (3): 614–20. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.3.614. PMID 15321800.

- ^ Zulet MA, Marti A, Parra MD, Martínez JA (September 2005). "Inflammation and conjugated linoleic acid: mechanisms of action and implications for human health". Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 61 (3): 483–94. doi:10.1007/BF03168454. PMID 16440602. S2CID 32082565.

- ^ 반추동물의 트랜스지방이 도움이 될 수 있음 – Wayback Machine에서 2013-01-17 건강 뉴스 아카이브적색 궤도 (2011년 9월 8일).2013년 1월 22일 회수.

- ^ Bassett CM, Edel AL, Patenaude AF, McCullough RS, Blackwood DP, Chouinard PY, et al. (January 2010). "Dietary vaccenic acid has antiatherogenic effects in LDLr-/- mice". The Journal of Nutrition. 140 (1): 18–24. doi:10.3945/jn.109.105163. PMID 19923390.

- ^ Wang Y, Jacome-Sosa MM, Vine DF, Proctor SD (20 May 2010). "Beneficial effects of vaccenic acid on postprandial lipid metabolism and dyslipidemia: Impact of natural trans-fats to improve CVD risk". Lipid Technology. 22 (5): 103–106. doi:10.1002/lite.201000016.

- ^ 데이비드 J. 베어 박사.미국 농무부, 농업 연구 서비스, 벨츠빌 인체 영양 연구소.유제품 트랜스 지방 및 심장 질환 위험에 대한 새로운 발견, IDF 세계 유제품 서밋 2010, 2010년 11월 8-11일.오클랜드, 뉴질랜드

- ^ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (NDA) (2010). "Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for fats". EFSA Journal. 8 (3): 1461. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1461.

- ^ UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2007). "Update on trans fatty acids and health, Position Statement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2010.

- ^ Brouwer IA, Wanders AJ, Katan MB (March 2010). "Effect of animal and industrial trans fatty acids on HDL and LDL cholesterol levels in humans--a quantitative review". PLOS ONE. 5 (3): e9434. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9434B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009434. PMC 2830458. PMID 20209147.

- ^ "Trans fat". It's your health. Health Canada. Dec 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012.

- ^ "EFSA sets European dietary reference values for nutrient intakes" (Press release). European Food Safety Authority. 26 March 2010.

- ^ "WHO plan to eliminate industrially-produced trans-fatty acids from global food supply" (Press release). World Health Organization. 14 May 2018.

- ^ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. i. Archived from the original on 18 September 2006.

- ^ 요약 Wayback Machine에서 2007-06-25 보관.

- ^ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 447.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Food and nutrition board, institute of medicine of the national academies (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academies Press. p. 424.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Eller FJ, List GR, Teel JA, Steidley KR, Adlof RO (July 2005). "Preparation of spread oils meeting U.S. Food and Drug Administration Labeling requirements for trans fatty acids via pressure-controlled hydrogenation". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (15): 5982–4. doi:10.1021/jf047849+. PMID 16028984.

- ^ Hadzipetros P (25 January 2007). "Trans Fats Headed for the Exit". CBC News.

- ^ Spencelayh M (9 January 2007). "Trans fat free future". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ^ van de Rest O, Geleijnse JM, Kok FJ, van Staveren WA, Dullemeijer C, Olderikkert MG, Beekman AT, de Groot CP (August 2008). "Effect of fish oil on cognitive performance in older subjects: a randomized, controlled trial". Neurology. 71 (6): 430–8. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000324268.45138.86. PMID 18678826. S2CID 45576671.

- ^ Mensink, Ronald P.; Sanders, Thomas A.; Baer, David J.; Hayes, K. C.; Howles, Philip N.; Marangoni, Alejandro (2016-07-01). "The Increasing Use of Interesterified Lipids in the Food Supply and Their Effects on Health Parameters". Advances in Nutrition. 7 (4): 719–729. doi:10.3945/an.115.009662. ISSN 2161-8313. PMC 4942855. PMID 27422506.

- ^ Zock PJ, de Vries JH, de Fouw NJ, Katan MB (1995), "Positional distribution of fatty acids in dietary triglycerides: effects on fasting blood lipoprotein concentrations in humans." (PDF), Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 48–551, doi:10.1093/ajcn/61.1.48, hdl:1871/11621, PMID 7825538, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- ^ Nestel PJ, Noakes M, Belling GB, et al. (1995), "Effect on plasma lipids of interesterifying a mix of edible oils." (PDF), Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 950–55, doi:10.1093/ajcn/62.5.950, PMID 7572740, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- ^ Meijer GW, Weststrate JA (1997), "Interesterification of fats in margarine: effect on blood lipids, blood enzymes and hemostasis parameters.", Eur J Clin Nutr, vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 527–34, doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600437, PMID 11248878

- ^ Grande F, Anderson JT, Keys A (1970), "Comparison of effects of palmitic and stearic acids in the diet on serum cholesterol in man." (PDF), Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 1184–93, doi:10.1093/ajcn/23.9.1184, PMID 5450836, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- ^ Berry SE, Miller GJ, Sanders TA (2007), "The solid fat content of stearic acid-rich fats determines their postprandial effects." (PDF), Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 85, no. 6, pp. 1486–94, doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1486, PMID 17556683, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03

- ^ Zampelas A, Williams CM, Morgan LM, et al. (1994), "The effect of triacylglycerol fatty acids positional distribution on postprandial plasma metabolite and hormone responses in normal adult men.", Br J Nutr, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 401–10, doi:10.1079/bjn19940147, PMID 8172869

- ^ Yli-Jokipii K, Kallio H, Schwab U, et al. (2001), "Effects of palm oil and transesterified palm oil on chylomicron and VLDL triacylglycerol structures and postprandial lipid response." (PDF), J Lipid Res, vol. 42, no. 10, pp. 1618–25, PMID 11590218, archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-04

- ^ Berry SE, Woodward R, Yeoh C, Miller GJ, Sanders TA (2007), "Effect of interesterification of palmitic-acid rich tryacylglycerol on postprandial lipid and factor VII response", Lipids, 42 (4): 315–323, doi:10.1007/s11745-007-3024-x, PMID 17406926, S2CID 3986807

- ^ Summers LK, Fielding BA, Herd SL, et al. (1999), "Use of structured triacylglycerols containing predominantly stearic and oleic acids to probe early events in metabolic processing of dietary fat" (PDF), J Lipid Res, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 1890–98, PMID 10508209, archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-04

- ^ Christophe AB, De Greyt WF, Delanghe JR, Huyghebaert AD (2000), "Substituting enzymically interesterified butter for native butter has no effect on lipemia or lipoproteinemia in man", Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 44 (2): 61–67, doi:10.1159/000012822, PMID 10970994, S2CID 22276158

- ^ Sundram K, Karupaiah T, Hayes K (2007). "Stearic acid-rich interesterified fat and trans-rich fat raise the LDL/HDL ratio and plasma glucose relative to palm olein in humans" (PDF). Nutr Metab. 4: 3. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-4-3. PMC 1783656. PMID 17224066. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-01-28. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- ^ Destaillats F, Moulin J, Bezelgues JB (2007), "Letter to the editor: healthy alternatives to trans fats", Nutr Metab, vol. 4, p. 10, doi:10.1186/1743-7075-4-10, PMC 1867814, PMID 17462099

- ^ Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester AD, Katan MB (2003), "Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials." (PDF), Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 77, no. 5, pp. 1146–1155, doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146, PMID 12716665, archived (PDF) from the original on 2004-02-14

- ^ "Boston scientists say triglycerides play key role in heart health". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ Ivanova EA, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN (2017). "Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein as Biomarker for Atherosclerotic Diseases". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017: 1273042. doi:10.1155/2017/1273042. PMC 5441126. PMID 28572872.

- ^ "Triglycerides". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ 크로포드, H, 마이클현재 진단 및 치료 심장학.3판.맥그로-힐 메디컬, 2009. p19

- ^ "What's considered normal?". Triglycerides: Why do they matter?. Mayo Clinic. 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b Nordestgaard, BG; Varbo, A (August 2014). "Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease". The Lancet. 384 (9943): 626–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61177-6. PMID 25131982. S2CID 33149001.

- ^ GILL, Jason; Sara HERD; Natassa TSETSONIS; Adrianne HARDMAN (Feb 2002). "Are the reductions in triacylglycerol and insulin levels after exercise related?". Clinical Science. 102 (2): 223–231. doi:10.1042/cs20010204. PMID 11834142. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ a b 크로포드, H, 마이클현재 진단 및 치료 심장학.3판.맥그로-힐 메디컬, 2009. p21

- ^ a b c Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. (September 2012). "Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 (9): 2969–89. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213. PMC 3431581. PMID 22962670.

- ^ Davidson, Michael H. (28 January 2008). "Pharmacological Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease". In Davidson, Michael H.; Toth, Peter P.; Maki, Kevin C. (eds.). Therapeutic Lipidology. Contemporary Cardiology. Cannon, Christopher P.; Armani, Annemarie M. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press, Inc. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-58829-551-4.

- ^ Abourbih S, Filion KB, Joseph L, Schiffrin EL, Rinfret S, Poirier P, Pilote L, Genest J, Eisenberg MJ (2009). "Effect of fibrates on lipid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review". Am J Med. 122 (10): 962.e1–962.e8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.030. PMID 19698935.

- ^ Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, et al. (2010). "Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 375 (9729): 1875–1884. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60656-3. PMID 20462635. S2CID 15570639.

- ^ Blair, HA; Dhillon, S (Oct 2014). "Omega-3 carboxylic acids: a review of its use in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia". Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 14 (5): 393–400. doi:10.1007/s40256-014-0090-3. PMID 25234378. S2CID 23706094.

- ^ Panov, Alexander; Orynbayeva, Zulfiya; Vavilin, Valentin; Lyakhovich, Vyacheslav (2014). Baranova, Ancha (ed.). "Fatty Acids in Energy Metabolism of the Central Nervous System". BioMed Research International. Hindawa. 2014 (The Roads to Mitochondrial Dysfunction): 472459. doi:10.1155/2014/472459. PMC 4026875. PMID 24883315.