아메다바드

Ahmedabad아메다바드 카르나바티, 아샤발 | |

|---|---|

| 암다바드 | |

| 닉네임: 인도의 문화유산 도시 | |

| 나라 | |

| 주 | 구자라트 주 |

| 구 | 아메다바드 |

| 설립 | 아샤발로서의 11세기 |

| 설립자 : | 아샤 브힐 왕 |

| 이름: | 아흐마드 샤 1세 |

| 정부 | |

| • 유형 | 시장-의회 |

| • 본문 | 암다바드 시 |

| • 시장님 | 키리트 파르마 (BJP) |

| • 부시장 | 기타 파텔 (BJP)[1] |

| • 시위원 | M. 텐나라산[2] |

| • 경찰청장 | 산제이 슈리바스타브 IPS[3] |

| 지역 | |

| • 토탈 | 1,866 km2 (720 sqmi) |

| • 등수 | 인도 8위 (구자랏 주 1위) |

| 승진 | 53m (174ft) |

| 인구. (2023)[6] | |

| • 토탈 | EST 8,650,605 |

| • 등수 | 5번째 |

| 데몬(들) | 암다바디, 아메다바디 |

| 언어 | |

| • 오피셜 | 구자라트 주 |

| • 추가관계자 | 영어 |

| 시간대 | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| 핀코드 | 3800XX |

| 지역코드 | 079 |

| 차량등록 | GJ-01(서쪽), GJ-27(동쪽), GJ-38바블라(농촌)[7] |

| HDI (2016) | 0.867[8] |

| 성비 | 1.11[9] ♂/♀ |

| 식자율 | 85.3%[10] |

| 국내총생산 | 680억[11] 달러 |

| 웹사이트 | ahmedabadcity |

| 기준 | 문화: (ii), (v) |

| 언급 | 1551 |

| 비문 | 2017년 (제41회) |

| 지역 | 535.7 ha (2.068 sqmi) |

| 완충구역 | 395 ha (1.53 sqmi) |

아메다바드(/ˈɑːm ə b æd, -b ɑːd/ AH-m ə-d ə-ba(h)d; 구자라티:ˈəmd ɑːʋɑːd)는 인도 구자라트 주에서 가장 인구가 많은 도시입니다.아메다바드 지역의 행정 본부이자 구자라트 고등법원의 소재지입니다.아메다바드의 인구는 5,570,585명(2011년 인구 조사 기준)으로 인도에서 다섯 번째로 인구가 많은 도시이며,[14] 6,357,693명으로 추정되는 전체 도시 인구는 인도에서 일곱 번째로 인구가 많은 도시입니다.아흐메다바드는 쌍둥이 도시라고도 알려진 간디나가르의 구자라트 수도로부터 25 km [16](16 mi) 떨어진 [15]사바르마티 강둑 근처에 위치하고 있습니다.[17]

아메다바드는 인도의 중요한 경제 및 산업 중심지로 부상했습니다.칸푸르와 함께 '인도의 맨체스터'로 알려진 인도에서 두 번째로 큰 목화 생산지입니다.아메다바드의 증권 거래소는 (2018년 폐쇄되기 전) 이 나라에서 두 번째로 오래되었습니다.크리켓은 아메다바드에서 인기 있는 스포츠입니다. 모테라에 있는 Narendra Modi Stadium이라고 불리는 새로 지어진 경기장은 132,000명의 관중을 수용할 수 있어 세계에서 가장 큰 경기장입니다.세계적인 Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Sports Enclave는 현재 건설 중이며 완공되면 인도에서 가장 큰 스포츠 센터(Sports City) 중 하나가 될 것입니다.인도 경제의 자유화의 효과는 상업, 통신 및 건설과 같은 3차 부문 활동으로 인도의 경제에 활력을 불어넣었습니다.[18]아메다바드의 인구 증가는 건설업과 주택 산업의 증가로 이어졌고, 그 결과 고층 건물의 발전을 가져왔습니다.[19]

2010년, 아메다바드는 포브스지가 선정한 10년 중 가장 빠르게 성장한 도시 3위에 올랐습니다.[20]2012년, 타임즈 오브 인디아는 아메다바드를 인도에서 가장 살기 좋은 도시로 선정했습니다.[21]2020년 아메다바드 지하철의 국내 총생산은 680억 달러로 추산되었습니다.[22]2020년에 아메다바드는 생활 편의 지수에서 인도에서 세 번째로 살기 좋은 도시로 선정되었습니다.[23]2022년 7월, 타임지는 아메다바드를 2022년 세계에서 가장 위대한 50곳의 목록에 포함시켰습니다.[24]

아메다바드는 인도 정부의 대표적인 스마트 시티 미션에 따라 스마트 시티로 개발될 인도 100개 도시 중 하나로 선정되었습니다.[25]2017년 7월, 역사적인 도시인 아메다바드, 즉 올드 아메다바드가 유네스코 세계 문화 유산 도시로 선언되었습니다.[26]

어원

"아흐메다바드"라는 이름은 서기 1411년에 이 도시를 설립한 술탄 아흐메드 샤의 이름에서 유래되었습니다.그 도시의 원래 이름은 "아사발" 이었는데, 이것은 사바르마티 강둑에 위치한 작은 정착지였습니다.[27]

지역 전설에 따르면, 술탄 아흐메드 샤는 사냥 탐험을 하러 나갔다가 자신의 사냥개들과 마주칠 만큼 용감한 토끼와 마주쳤다고 합니다.토끼의 용기에 감명을 받은 술탄 아흐메드 샤는 그 자리에 새로운 도시를 건설하기로 결정하고 자신의 이름을 따 "아흐메다바드" 라고 이름 지었습니다.[28]

수년에 걸쳐, 아메다바드는 무역과 상업의 중요한 중심지가 되면서 번영한 도시로 성장했습니다.오늘날 인도의 가장 큰 도시 중 하나이며 기념물, 박물관, 축제 등 풍부한 문화 유산으로 유명합니다.[29]당시 아힐와라(현재의 파탄)의 차울루키야(솔란키) 통치자인 카르나는 아샤발의 빌 왕과 전쟁을 벌여 성공을 거두고 [30]사바르마티 강둑에 카르나바티라는 도시를 세웠습니다.[31]

역사

아흐메다바드 주변 지역은 아샤발이라고 알려졌던 11세기부터 사람들이 거주해왔습니다.[32]당시 아힐와라(현재의 파탄)의 차울루키야(솔란키) 통치자인 카르나는 아샤발의 빌 왕과 전쟁을 벌여 성공을 거두고 [33]사바르마티 강둑에 카르나바티라는 도시를 세웠습니다.[31]솔란키의 통치는 구자라트가 돌카의 바겔라 왕조의 지배를 받게 된 13세기까지 지속되었습니다.구자라트는 그 후 14세기에 델리 술탄국의 지배하에 들어갔습니다.하지만, 15세기 초까지, 지역의 무슬림 총독 Zafar Khan Muzaffar는 델리 술탄국으로부터 그의 독립을 확립했고, 스스로 구자라트의 술탄을 Muzaffar Shah I로 추대하여, 무자파리드 왕조를 세웠습니다.[34][35][36]1411년, 그 지역은 그의 손자인 술탄 아흐메드 샤의 통제하에 들어갔고, 그는 그의 새로운 수도를 위해 사바르마티 강둑을 따라 숲이 우거진 지역을 선택했습니다.그는 카르나바티 근처에 새로운 성벽 도시의 기초를 놓았고, 자신의 이름을 따서 아메다바드라고 이름 지었습니다.[37][38]다른 기록에 따르면, 그는 그 지역에 있는 4명의 이슬람교 성인들의 이름을 따서 그 도시의 이름을 지었다고 합니다. 그들은 모두 아흐메드라는 이름을 가지고 있었습니다.[39]아흐메드 샤 1세는 1411년[40] 2월 26일(목요일 오후 1시 20분, 히즈리년 813년[41] 두 알키다 둘째 날) 마네크 부르즈에서 도시의 기초를 다졌습니다.마네크 부르즈는 1411년 아흐메드 샤 1세가 바드라 요새를 건설하는 것을 돕기 위해 개입한 전설적인 15세기 힌두 성인 마네크나트의 이름을 따서 지어졌습니다.[37][42][43][44]그는 1411년 3월 4일 이곳을 새로운 수도로 선택했습니다.[45]성 마네크나트의 13대 후손인 찬단과 라제시 나트는 매년 아메다바드 창립일과 비자야다샤미 축제 때 푸자를 하고 국기를 게양합니다.[37][43][46][47]

1487년, 아흐메드 샤의 손자인 마흐무드 베가다는 둘레가 10킬로미터(6.2마일)인 외벽으로 도시를 요새화했고, 12개의 문, 189개의 요새, 그리고 6,000개가 넘는 전투로 구성되었습니다.[48]1535년 구자라트의 통치자 바하두르 샤가 디우로 도망쳤을 때, 후마윤은 참파네르를 점령한 후 잠시 아메다바드를 점령했습니다.[49]그 후 아메다바드는 1573년 구자라트가 무굴 황제 아크바르에 의해 정복될 때까지 무자파리드 왕조에 의해 다시 점령되었습니다.무굴 통치 기간 동안 아메다바드는 제국의 무역의 중심지 중 하나가 되었고, 주로 직물을 중심으로 유럽까지 수출되었습니다.무굴의 통치자 샤자한은 샤히바우그에 있는 모티 샤히 마할의 건설을 후원하며 일생의 전성기를 그 도시에서 보냈습니다.1630-32년의 데칸 기근은 1650년과 1686년의 기근과 마찬가지로 도시에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[50]아마다바드는 1758년까지 무굴족의 지방 본부로 남아있었는데, 그 때 그들은 마라타족에게 도시를 항복시켰습니다.[51]

마라타 제국의 통치 기간 동안, 이 도시는 푸나의 페스화와 바로다의 개크와드 사이의 갈등의 중심지가 되었습니다.[52]1780년, 제1차 영국-마라타 전쟁 중 제임스 하틀리 휘하의 영국군이 아메다바드를 급습하여 점령했지만, 전쟁이 끝나자 마라타족에게 다시 넘겨졌습니다.영국 동인도 회사는 제3차 영국-마라타 전쟁 중인 1818년에 그 도시를 인수했습니다.[39]1824년에는 군정이, 1858년에는 시정이 세워졌습니다.[39]영국 통치 기간 동안 봄베이 대통령직에 통합된 아메다바드는 구자라트 지역에서 가장 중요한 도시 중 하나가 되었습니다.1864년 봄베이, 바로다, 센트럴 인디아 철도(BB&)에 의해 아메다바드와 뭄바이(당시 봄베이) 사이의 철도 연결이 설립되었습니다.CI), 도시를 통해 인도 북부와 남부 사이의 교통과 무역을 가능하게 합니다.[39]시간이 지나면서, 그 도시는 발전하는 섬유 산업의 본거지로 자리매김했고, 이것은 "동쪽의 맨체스터"라는 별명을 얻었습니다.[53]

마하트마 간디가 1915년 팔디 근처의 코흐랍 아쉬람과 1917년 사바르마티 강둑에 사티아그라하 아쉬람(현재의 사바르마티 아쉬람)이라는 두 개의 아쉬람을 설립하면서 인도 독립 운동은 도시에 뿌리를 내리게 되었습니다.[39][54]1919년 롤래트 법에 반대하는 대규모 시위 동안, 섬유 노동자들은 1차 세계대전 이후 전시 규제를 연장하려는 영국의 시도에 항의하여 도시 전역의 51개의 정부 건물을 불태웠습니다.1920년대에 섬유 노동자들과 교사들은 시민권과 더 나은 임금과 노동조건을 요구하며 파업에 들어갔습니다.1930년 간디는 아흐메다바드에서 단디 소금 행진을 위해 그의 회람에서 출발함으로써 소금 사티아그라하를 시작했습니다.평화적인 시위로 거리로 나온 많은 사람들에 의해 도시의 행정부와 경제 기관들은 1930년대 초에 작동하지 않게 되었고, 1942년에는 인도철수운동 기간에 다시 작동하지 않게 되었습니다.1947년 인도의 독립과 분할 이후, 도시는 1947년 힌두교도들과 이슬람교도들 사이에 발생한 극심한 공동 폭력으로 상처를 입었습니다. 아마다바드는 도시의 인구를 늘리고 인구와 경제를 변화시킨 [55]파키스탄 출신의 힌두 이민자들에 의해 정착의 중심지였습니다.

1960년까지 아메다바드는 50만 명이 조금 안 되는 인구를 가진 대도시가 되었고, 고전적이고 식민지 시대의 유럽풍 건물들이 도시의 철저한 도로에 늘어서 있었습니다.[56]1960년 5월 1일 봄베이 주의 분할 이후 구자라트 주의 주도로 선정되었습니다.[57]이 기간 동안 많은 수의 교육 및 연구 기관이 도시에 설립되어 고등 교육, 과학 및 기술의 중심지가 되었습니다.[58]같은 기간 중에 중화학공업이 설립되면서 아메다바드의 경제 기반은 더욱 다양해졌습니다.많은 나라들이 인도의 경제 계획 전략을 모방하려고 했고, 그들 중 하나인 한국은 인도의 두 번째 "5개년 계획"을 모방했습니다.[59]

1970년대 후반, 수도는 새로 건설된 도시 간디나가르로 옮겨갔습니다.이것은 개발의 부족으로 특징지어지는, 그 도시의 오랜 쇠퇴의 시작을 나타냅니다.1974년 나브 니르만 선동 – L.D.의 호스텔 식비 20% 인상 반대 시위. 아메다바드 공과대학 – 당시 구자라트의 수석 장관이었던 치만바이 파텔을 제거하려는 움직임으로 눈덩이처럼 불어났습니다.[60]1980년대에 국내에 예약 정책이 도입되어 1981년과 1985년에 예약 반대 시위가 벌어졌습니다.시위는 다양한 카스테스에 속한 사람들 사이의 폭력적인 충돌을 목격했습니다.[61]그 도시는 2001년 구자라트 지진에 상당한 영향을 받았습니다; 50개의 다층 건물이 붕괴되었고, 752명이 사망하고 많은 피해를 입었습니다.[62]2002년 구자라트 폭동으로 알려진 인도 서부 구자라트 주에서 3일간의 힌두교도와 이슬람교도 간의 폭력 사태가 아메다바드로 확산되었고, 동부 차만푸라에서는 2002년 2월 28일 굴바르그 사회 학살로 69명이 사망했습니다.[63]도시 주변에 난민 캠프가 설치되어 50,000명의 이슬람교도들과 몇몇 작은 힌두교 캠프들을 수용했습니다.[64]

2008년 아메다바드 폭탄 테러, 17차례의 폭탄 폭발로 여러 명이 사망하고 부상했습니다.[65]테러 단체 하르카트울지는 이번 공격이 자신들의 소행이라고 주장했습니다.[66]

아메다바드는 인도에서 미국, 중국, 캐나다와 같은 주요 경제국의 총리를 유치한 몇 안 되는 도시 중 하나입니다.2020년 2월 24일, 도널드 트럼프 미국 대통령이 뉴욕을 방문한 최초의 대통령이 되었습니다.이 행사의 이름은 나마스테 트럼프 입니다.앞서 시진핑 주석과 쥐스탱 트뤼도 총리가 서울을 방문했습니다.[67][68][69]

인구통계학

인구.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 출처 : 인도의 인구조사 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2011년 인도 인구[update] 조사에서 아메다바드의 인구는 5,633,927명으로 인도에서 5번째로 인구가 많은 도시입니다.[citation needed]아메다바드를 중심으로 한 도시 집적지는 현재 7,650,000명으로 추정되는 6,357,693명의 인구를 가진 인도에서 7번째로 인구가 많은 도시 집적지입니다.[15][16]그 도시는 88.29%의 식자율을 가지고 있었습니다; 남자의 92.30%와 여자의 83.85%가 식자율을 가지고 있었습니다.[citation needed]제9차 계획 인구조사에 따르면, 아메다바드에는 30,737명의 시골 가족들이 살고 있습니다.이 중 5.41%(1663가구)가 빈곤선 이하로 살고 있습니다.[70]약 44만 명의 사람들이 도시 내의 빈민가에 살고 있습니다.[71]2008년에 아메다바드에는 2273명의 비거주 인도인이 살고 있었습니다.[72]2020년[update] 기준으로 아메다바드의 인구는 8,059,441명으로 추산됩니다.1950년, 아메다바드의 인구는 854,959명이었습니다.아메다바드는 2015년 이후 950,155명이 증가했으며, 이는 연간 2.54%의 변화를 의미합니다.[73]유엔 세계 인구 전망에 따르면, 2025년까지 인구는 8,854,444명으로 증가할 수 있습니다.빠르면 2035년 11,062,112명으로 급증할 것으로 전망됩니다.[74]

2010년 포브스지는 아메다바드를 인도에서 가장 빠르게 성장하는 도시로 평가했고, 중국의 도시 청두와 충칭에 이어 세계에서 세 번째로 빠르게 성장하는 도시로 선정했습니다.[75]2011년에는 선도적인 시장 조사 기관인 IMRB로부터 인도에서 가장 살기 좋은 도시로 선정되기도 했습니다.[76]2003년 국가범죄기록국(NCRB)의 보고서에 따르면, 아메다바드는 인구 백만 명 이상의 인도 35개 도시 중에서 범죄율이 가장 낮습니다.[77]2011년 12월, 시장 조사 회사인 IMRB는 인도의 다른 거대 도시들과 비교했을 때 아메다바드가 살기에 가장 좋은 거대 도시라고 발표했습니다.[78]

B.K의 교수인 브라즐랄 사포바디아에 따르면, 아메다바드의 모든 부동산의 절반 미만이 "공동체 조직"(즉, 협동조합)에 의해 소유되고 있습니다.경영대학원, "도시의 공간적 성장은 이러한 조직들의 기여 정도입니다."[79]아메다바드 주 정부는 인도 육군 간부들을 위한 거주지역을 제공하고 있습니다.[80]

빈곤

1970년대 중반과 1980년대 초, 아흐메다바드의 부의 상당 부분을 담당했던 방직 공장들은 자동화와 국내 전문 직기와의 경쟁에 직면했습니다.몇몇 공장들은 문을 닫았고, 4만에서 5만명 사이의 사람들이 수입원을 잃었고, 많은 사람들이 도심의 비공식적인 정착지로 이주했습니다.아메다바드 시의 관리 및 행정 기관인 아메다바드 시는 동시에 과세 기반의 많은 부분을 잃었고 서비스에 대한 수요가 증가했습니다.1990년대 들어 새롭게 등장한 제약, 화학, 자동차 제조업은 숙련된 노동력을 필요로 하기 때문에 일자리를 찾는 많은 이주민들은 결국 비공식 부문에 종사하게 되고 슬럼가에 정착하게 됩니다.[81]

아메다바드는 가난을 줄이고 가난한 주민들의 생활 조건을 개선하기 위해 노력해왔습니다.도시 빈곤율은 1993-1994년 28%에서 2011-2012년 10%로 하락했습니다.[81]이것은 부분적으로 AMC의 강화와 가난한 주민들을 대표하는 여러 시민사회단체(CSO)와의 협력에 기인합니다.AMC는 프로젝트와 프로그램을 통해 빈민가에 유틸리티와 기본적인 서비스를 제공해 왔습니다.하지만, 몇 가지 어려움이 남아 있고, 위생 시설, 깨끗한 수돗물, 전기를 이용할 수 없는 주민들이 여전히 많습니다.종종 종교적 긴장에 뿌리를 둔 폭동은 지역사회의 안정을 위협하고 종교와 카스트 제도에 걸쳐 공간적 분리를 야기했습니다.자본 투자와 기술 혁신의 초점이 되는 '글로벌 도시'를 만드는 것을 목표로 하는 국가적 계획과 친빈곤, 포용적 개발의 균형을 맞추는 공동의 노력이 남아 있습니다.

비공식 주택과 빈민가

2011년 기준으로 인구의 약 66%가 정식 주택에 거주하고 있으며, 나머지 34%는 산업 노동자들을 위한 주택인 슬럼가나 채울에 살고 있습니다.아마다바드에는 약 700개의 슬럼 정착촌이 있으며, 전체 주택 재고의 11%가 공공 주택입니다.아메다바드의 인구는 증가한 반면 주택 재고는 전반적으로 일정하게 유지되고 있으며, 이는 공식 및 비공식 주택의 밀도 증가와 기존 공간의 경제적 사용으로 이어졌습니다.인도 인구조사에 따르면 아메다바드 빈민가 인구는 1991년 전체 인구의 25.6%였으며 2011년에는 4.5%로 감소했다고 추정하지만, 이 수치는 논란의 여지가 있으며 지역 단체들은 인구조사가 비공식 인구를 과소 추정한다고 주장합니다.슬럼 정착촌에 거주하는 인구 비율이 감소했고, 슬럼 주민들의 생활 여건도 전반적으로 개선됐다는 데도 공감대가 형성되고 있습니다.[81][needs update?]

슬럼 네트워킹 프로젝트

1990년대에 AMC는 슬럼가 인구 증가에 직면했습니다.그들은 거주자들이 수도, 하수도, 그리고 전기에 대한 합법적인 연결에 대해 기꺼이 그리고 지불할 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다. 그러나, 거주기간 문제 때문에, 그들은 낮은 품질의, 비공식적인 연결에 대해 더 높은 가격을 지불하고 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.이를 해결하기 위해 1995년부터 AMC는 시민사회단체와 협력하여 슬럼 네트워킹 프로젝트(SNP: Slum Networking Project)를 개발하여 60여 개 슬럼의 기본 서비스를 개선하고 약 13,000여 가구가 혜택을 받았습니다.[81]파리바르탄(Change)이라고도 알려진 이 프로젝트는 빈민가 주민들이 AMC, 민간 기관, 소액 금융 대출 기관 및 지역 NGO와 함께 파트너가 되는 참여형 계획을 포함했습니다.이 프로그램의 목적은 물리적 기반시설(급수, 하수도, 개별 화장실, 포장도로, 빗물 배수 및 나무심기 포함)과 지역사회 발전(즉, 주민단체, 여성단체, 지역사회 건강 개입 및 직업훈련)을 제공하는 것이었습니다.[82]또한, 참여 가구는 사실상 최소 10년의 재직 기간을 부여받았습니다.이 프로젝트에는 총 ₹4,350만 달러가 들었습니다.지역 사회 구성원들과 민간 부문들은 각각 ₹6억 달러를 기부했고, NGO들은 ₹9천만 달러를 제공했고, AMC는 나머지 프로젝트에 대한 비용을 지불했습니다.슬럼가의 각 가구는 주택 업그레이드 비용의 12% 이하를 책임지고 있었습니다.[81]

이 프로젝트는 일반적으로 성공적인 것으로 여겨져 왔습니다.대부분의 사람들이 집 밖에서 일을 하기 때문에, 기본적인 서비스를 이용할 수 있게 됨으로써 거주자들의 근무시간이 늘어났습니다.그것은 또한 질병, 특히 수인성 질병의 발병률을 감소시켰고, 아이들의 등교율을 높였습니다.[83]SNP는 2006년 UNHAB을 받았습니다.ITAT 두바이 국제 생활 환경 개선 모범 사례상.[84]그러나 새로운 인프라의 유지보수에 대한 지역사회의 책임과 능력에 대한 우려는 여전히 남아 있습니다.또한 AMC가 SNP의 일환으로 업그레이드 된 슬럼 2개를 철거하여 휴양공원을 조성하면서 신뢰가 약화되었습니다.[81]

종교와 민족

2011년 인구 조사에 따르면, 힌두교도는 인구의 81.56%를 차지하는 이 도시의 주요 종교 공동체이며, 이슬람교도 (13.51%), 자인 (3.62%), 기독교인 (0.85%), 시크교 (0.24%)[85]가 그 뒤를 이었습니다.불교도, 다른 종교를 따르는 사람들, 그리고 어떤 종교도 언급하지 않은 사람들이 나머지를 구성합니다.

- 미르자푸르에 있는 카르멜산 성모 대성당은 아메다바드 교구의 성당입니다.[86][87]

- 아메다바드의 주민 대부분은 구자라트 원주민입니다.이 도시에는 약 2000명의 파르시(조로아스터교)와 [88]베네이스라엘 유대인 공동체의 125명의 회원이 살고 있습니다.[89]이 도시에는 유대교 회당도 하나 있습니다.[90]

지리학

아메다바드는 구자라트 중북부의 사바르마티 강둑에 위치한 해발 53미터의 인도 서부에 위치하고 있습니다.면적은 505 km2 (195 sqmi) 입니다.[91][92][93][94]사바르마티는 여름에 물이 자주 마르고 작은 물줄기만 남는데, 이 도시는 모래가 많고 건조한 지역에 있습니다.그러나 사바르마티 강 전선 프로젝트와 제방의 실행으로 나르마다 강의 물이 사바르마티 강으로 흘러들어가 연중 강물이 흐르게 함으로써 아메다바드의 물 문제를 제거했습니다.쿠치의 란 강의 꾸준한 확장은 도시 지역과 주의 많은 지역 주변의 사막화를 증가시킬 위협이 되었지만, 나르마다 운하 네트워크는 이 문제를 완화시킬 것으로 예상됩니다.Taltej-Jodhpur Tekra의 작은 언덕들을 제외하고, 그 도시는 거의 평평합니다.칸카리아, 바스트라푸르, 찬돌라 등 세 개의 호수가 도시의 경계 안에 있습니다.마니나가르 근처에 있는 칸카리아는 1451년 구자라트의 술탄 쿠트브-우드딘에 의해 개발된 인공 호수입니다.[95]

인도 표준국에 따르면 이 도시는 지진에 대한 취약성을 증가시키기 위해 2에서 5까지의 규모로 지진 구역 3에 해당합니다.[96]

아메다바드는 사바르마티족에 의해 물리적으로 구분되는 동부와 서부 두 지역으로 나뉩니다.강의 동쪽 둑에는 바드라의 중심 마을을 포함하는 옛 도시가 자리잡고 있습니다.아메다바드의 이 지역은 바자회가 꽉 들어찬 것이 특징이며, 밀집된 건물들의 폴 시스템과 수많은 예배 장소들이 있습니다.[97]폴(Pol)은 카스트, 직업 또는 종교로 연결된 특정 집단의 많은 가족으로 구성된 주택 클러스터입니다.[98][99]이것은 인도 구자라트의 아메다바드라는 오래된 성벽 도시에[98] 있는 폴란드인들의 목록입니다.이러한[100] 폴란드인들의 유산은 아메다바드가 유네스코의 잠정목록인 선정기준 II, III, IV에 등재되는 데 도움이 되었습니다.[101]EuroIndia Center 사무총장은 아메다바드의 1만 2천 가구가 복구되면 유산 관광과 관련 사업을 촉진하는데 큰 도움이 될 것이라고 말했습니다.[102]모토 수타르바도의 아트 레비(Art Reverie)는 Res Artis 센터입니다.아메다바드의 첫 번째 폴은 마후라트 폴이라고 이름 붙여졌습니다.[103]구 도시에는 또한 주요 기차역, 주요 우체국, 그리고 무자파리드와 영국 시대의 몇몇 건물들이 있습니다.식민지 시대에는 도시가 사바르마티 강의 서쪽으로 확장되었고, 1875년 엘리스 다리(그리고 후에 현대의 네루 다리)의 건설로 촉진되었습니다.도시의 서부에는 교육 기관, 현대식 건물, 주거 지역, 쇼핑몰, 멀티플렉스, 그리고 아쉬람 로드, C.G. 로드, 사르케이-간디나가르 고속도로와 같은 도로를 중심으로 한 새로운 비즈니스 지구가 있습니다.[104]

사바르마티 강변은 인도 아메다바드의 사바르마티 강둑을 따라 개발되고 있는 해안 지역입니다.1960년대에 제안되어 2005년에 건설이 시작되었고, 2012년에 문을 열었습니다.[105]

기후.

아메다바드는 더운 반건조 기후(쾨펜 기후 구분: BSh)로 열대 사바나 기후에 필요한 비보다 약간 적은 비가 내립니다.여름, 몬순, 겨울의 세가지 주요 계절이 있습니다.장마철을 제외하면 기후는 매우 건조합니다.날씨는 3월부터 6월까지 덥습니다; 평균 여름 최고 기온은 43 °C (109 °F)이고, 평균 최저 기온이 24°C (75°F)입니다.11월부터 2월까지 평균 최고 기온은 30°C(86°F)이고, 평균 최저 기온은 13°C(55°F)입니다.북쪽에서 불어오는 찬 바람이 1월의 온화한 추위의 원인입니다.남서 몬순은 6월 중순에서 9월 중순까지 습한 기후를 가져옵니다.연평균 강우량은 약 800밀리미터(31인치)이지만, 잦은 집중호우로 인해 지역 하천이 범람하고 장마가 평소처럼 서쪽으로 멀리 확장되지 않을 때 가뭄이 발생하는 것은 드문 일이 아닙니다.2016년 5월 20일, 도시 최고 기온은 48°C(118°F)를 기록했습니다.[106]

| 아메다바드의 기후 자료(1991~2020년 정규) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 달 | 얀 | 2월 | 마 | 4월 | 그럴지도 모른다 | 준 | 줄 | 8월달 | 9월 | 10월달 | 11월 | 12월 | 연도 |

| 높은 °C(°F) 기록 | 36.1 (97.0) | 40.6 (105.1) | 43.9 (111.0) | 46.2 (115.2) | 48.0 (118.4) | 47.2 (117.0) | 42.2 (108.0) | 40.4 (104.7) | 41.7 (107.1) | 42.8 (109.0) | 38.9 (102.0) | 35.6 (96.1) | 48.0 (118.4) |

| 평균 높은 °C(°F) | 27.9 (82.2) | 31.0 (87.8) | 35.8 (96.4) | 39.7 (103.5) | 41.8 (107.2) | 39.0 (102.2) | 33.7 (92.7) | 32.3 (90.1) | 33.6 (92.5) | 35.6 (96.1) | 33.1 (91.6) | 29.5 (85.1) | 34.4 (93.9) |

| 일평균 °C(°F) | 20.2 (68.4) | 22.5 (72.5) | 27.6 (81.7) | 31.7 (89.1) | 34.3 (93.7) | 33.1 (91.6) | 29.7 (85.5) | 28.5 (83.3) | 29.2 (84.6) | 28.5 (83.3) | 24.8 (76.6) | 21.4 (70.5) | 27.6 (81.7) |

| 평균 낮은 °C(°F) | 12.4 (54.3) | 14.6 (58.3) | 19.6 (67.3) | 24.2 (75.6) | 27.3 (81.1) | 27.7 (81.9) | 26.1 (79.0) | 25.3 (77.5) | 24.9 (76.8) | 21.8 (71.2) | 17.2 (63.0) | 13.6 (56.5) | 21.2 (70.2) |

| 낮은 °C(°F) 기록 | 3.3 (37.9) | 2.2 (36.0) | 9.4 (48.9) | 12.8 (55.0) | 19.1 (66.4) | 19.4 (66.9) | 20.4 (68.7) | 21.2 (70.2) | 17.2 (63.0) | 12.6 (54.7) | 8.3 (46.9) | 3.6 (38.5) | 2.2 (36.0) |

| 평균강수량mm(인치) | 1.2 (0.05) | 0.6 (0.02) | 1.1 (0.04) | 2.5 (0.10) | 5.5 (0.22) | 84.3 (3.32) | 310.1 (12.21) | 242.2 (9.54) | 120.2 (4.73) | 13.1 (0.52) | 1.9 (0.07) | 0.9 (0.04) | 783.6 (30.85) |

| 평균 우천일수 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 6.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 33.9 |

| 평균상대습도(%) | 35 | 26 | 21 | 20 | 25 | 44 | 69 | 72 | 63 | 43 | 39 | 38 | 41 |

| 평균 이슬점 °C(°F) | 9 (48) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | 14 (57) | 19 (66) | 23 (73) | 25 (77) | 25 (77) | 24 (75) | 19 (66) | 14 (57) | 11 (52) | 17 (62) |

| 월평균 일조 시간 | 287.3 | 274.3 | 277.5 | 297.2 | 329.6 | 238.3 | 130.1 | 111.4 | 220.6 | 290.7 | 274.1 | 288.6 | 3,019.7 |

| 평균자외선지수 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 10 |

| 출처 1: 인도 기상청(2012년까지 최고 및 최저 기록)[107][108][109][110] 시간 및 날짜(듀포인트, 2005-2015)[111] | |||||||||||||

| 출처 2: NOAA (1971년~1990년),[112] IEM ASOS (5월 최고 기록)[113] 웨더 아틀라스[114] | |||||||||||||

2010년 5월 46.8 °C(116.2 °F)에 달하는 폭염과 수백 명의 목숨을 앗아간 후,[116] 아메다바드 시립 법인(AMC)은 보건 및 학술 단체의 국제 연합과 협력하고 기후 개발 지식 네트워크의 지원을 받아 아메다바드 열 행동 계획을 개발했습니다.[117]취약한 인구에 대한 더위의 건강 영향을 줄이기 위해 인식을 높이고 정보를 공유하며 대응을 조율하는 것을 목표로 하는 이 행동 계획은 건강에 대한 역열의 위협을 해결하기 위한 아시아 최초의 종합 계획입니다.[118]또한 지역사회 참여, 폭염 위험에 대한 대중의 인식 구축, 의료 및 지역사회 종사자들이 폭염과 관련된 질병에 대응하고 예방할 수 있도록 교육하고, 폭염이 닥쳤을 때 기관 간 비상 대응 활동을 조정하는 데 중점을 두고 있습니다.[119]

도시경관

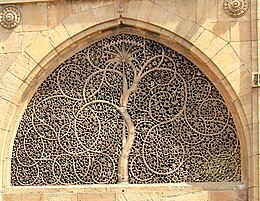

아흐메드 샤의 통치하에 있었던 아흐메다바드의 역사 초기 건축업자들은 힌두의 장인정신과 페르시아 건축을 융합하여 인도-사라키아 양식을 탄생시켰습니다.[120]이 도시의 많은 이슬람 사원들은 이런 방식으로 지어졌습니다.[120]시디 사이예드 모스크는 구자라트 술탄국의 마지막 해에 지어졌습니다.전체적으로 아치형이며, 측면과 후면 아치에 10개의 석재 격자무늬 창이나 잘리가 있습니다.이 시대의 개인 저택이나 하벨리에는 조각이 있습니다.[98]폴(Pol)은 Old Ahmedabad의 전형적인 주택 클러스터입니다.

독립 후에 현대식 건물들이 아메다바드에 나타났습니다.도시의 건축가들은 IIM-A를 설계한 Louis Kahn, Shodhan과 Sarabhai Villas, Sanskar Kendra와 Mill Owners' Association Building을 설계한 Le Corbusier, 그리고 Calico Mills와 Calico Dome의 행정 건물을 설계한 Frank Lloyd Wright를 포함합니다.[121][122]B. V. Doshi는 Le Corbusier의 작품을 감독하기 위해 파리에서 도시로 왔고 나중에 건축 학교(현재의 CEPT)를 세웠습니다.그의 지역 작품으로는 상가트, 암다바드니 구파, 타고르 기념관, 건축 학교 등이 있습니다.도시스의 파트너가 된 찰스 코레아는 간디 아쉬람과 아츄트 칸빈데, 아흐메다바드 섬유산업 연구회 단지를 설계했습니다.[123][124][125]Christopher Charles Benninger의 첫 번째 작품인 Alliance Française는 Ellis Bridge 지역에 위치해 있습니다.[126]아난트 라제는 Louis Kahn의 IIM-A 캠퍼스, 즉 Ravi Mathai Auditorium과 KLMD에 주요한 추가 시설을 설계했습니다.[127]

로 가든, 빅토리아 가든, 발 바티카 등이 이 도시에서 가장 많이 방문합니다.Law Garden은 근처에 위치한 Law College of Law에서 이름을 따왔습니다.빅토리아 가든은 바드라 요새의 남쪽 가장자리에 위치해 있으며 빅토리아 여왕의 동상이 있습니다.발바티카는 칸카리아 호수 주변에 위치한 어린이 공원으로 놀이공원도 있습니다.그 도시의 다른 정원으로는 파리말 정원, 우스만푸라 정원, 프라흘라드 나가르 정원, 랄 다르와자 정원 등이 있습니다.[128]아메다바드의 캄라 네루 동물원에는 플라밍고, 카라칼, 아시아 늑대, 친카라 등 멸종 위기에 처한 많은 종들이 살고 있습니다.[129]

서기 1451년에 지어진 칸카리아 호수는 아메다바드에서 가장 큰 호수 중 하나입니다.[130]초기에는 쿠투브 호즈 또는 하우즈에 쿠투브라는 이름으로 알려져 있었습니다.[131]바푸나가르의 랄 바하두르 샤스트리 호수는 거의 136,000 제곱 미터입니다.2010년에는 아메다바드 주변에 또 다른 34개의 호수가 계획되어 있으며, 이 중 5개의 호수는 AMC에 의해 개발될 예정이며, 나머지 29개는 아메다바드 도시개발청(AUDA)에 의해 개발될 예정입니다.[132]바스트라푸르 호수는 아메다바드의 서쪽에 위치한 작은 인공 호수입니다.2002년 지방 당국에 의해 미화된 이곳은 녹지와 포장된 산책로로 둘러싸여 시민들에게 인기 있는 여가 장소가 되었습니다.[133]찬돌라 호수의 면적은 1200헥타르입니다.가마우지, 칠황새, 저어새의 서식지입니다.[134]저녁 시간에는 많은 사람들이 이곳을 찾아 한가롭게 산책을 합니다.[135]나로다에는 최근에 개발된 호수가 있으며,[136] IB농장(다스탄농장)의 카트와다에는 세계 최대 규모의 골동품 자동차 컬렉션도 있습니다.[137]AMC는 사바르마티 강변도 개발했습니다.[138]

피라나 덤프 현장 인근에 배치된 교통경찰 직원들의 건강 상태를 살피며, 아메다바드 시 경찰은 배치된 직원들이 신선한 공기를 마실 수 있도록 교통 지점에 실외 공기청정기를 설치할 예정입니다.[139]

-

시디 사이예드 모스크 외부에서 바라본 대리석 스크린

-

후티싱 자인 데라사르 정문

-

칸카리아 호, 아마다바드

시정

아흐메다바드는 아흐메다바드 지역의 행정 본부로, 아흐메다바드 시공사(AMC)가 관리합니다.AMC는 1949년 봄베이 지방공사법에 따라 1950년 7월에 설립되었습니다.AMC 위원은 주 정부가 임명하는 인도 행정 서비스(IAS) 담당자로 행정 집행 권한을 보유하고 있으며, 법인은 아마다바드 시장이 맡고 있습니다.192명의 시의원을 시민투표로 선출하고, 선출된 의원은 부시장과 시장을 뽑습니다.비할 파텔 시장은 2018년 6월 14일에 임명되었습니다.[140]AMC의 행정적 책임은 상하수도 서비스, 초등 교육, 보건 서비스, 소방 서비스, 대중 교통 및 도시 기반 시설입니다.[94]AMC는 "2014년 인도 최고의 거버넌스 및 행정 관행"으로 21개 도시 중 9위를 차지했습니다.전국 평균 3.3점에 비해 10점 만점에 3.4점을 받았습니다."[141] 아메다바드는 시간당 두 건의 사고를 기록하고 있습니다.[142]

그 도시는 48개의 구를 구성하는 7개의 구역으로 나뉩니다.[143][144]도시의 도시와 교외 지역은 아메다바드 도시 개발청(AUDA)에 의해 관리됩니다.

- 도시는 록 사바 (인도 의회의 하원)에서 선출된 국회의원 2명과 구자라트 비단 사바에서 입법의회 의원 21명으로 대표됩니다.

- 구자라트 고등법원은 아마다바드에 위치해 있으며, 이 도시는 구자라트의 사법 수도가 되었습니다.[145]법 집행과 공공 안전은 인도 경찰국(IPS) 직원인 경찰국장이 이끄는 아메다바드 시 경찰에 의해 유지됩니다.[146]

공공서비스

- 의료 서비스는 주로 아시아에서 가장 큰 민간 병원인 아메다바드 민간 병원에서 제공됩니다.[147]

- 도시의 전기는 이전에 국영 기업이었던 아메다바드 전기 회사가 소유하고 운영하는 토렌트 전력 유한회사에 의해 생산되고 분배됩니다.[148]아메다바드는 인도에서 전력 부문이 민영화된 몇 안 되는 도시 중 하나입니다.[149]

문화

아메다바드 사람들은 다양한 축제를 축하합니다.1월 14일과 15일에 연날리기를 포함하는 추수 축제인 우타라얀이 기념 행사와 기념 행사를 포함합니다.나브라트리의 9일 밤은 도시 전역의 장소에서 구자라트의 가장 유명한 민속 춤인 가르바를 공연하는 사람들과 함께 기념됩니다.매년 열리는 라트 야트라 행렬은 자간나트 사원에서 힌두교 달력의 아샤드 수드비즈 날짜에 열립니다.디왈리, 홀리, 크리스마스 그리고 무하람과 같은 축제들 또한 기념됩니다.[150][151]

아흐메다바드에서 가장 인기 있는 요리 중 하나는 구자라트 탈리인데, 1900년에 찬드빌라스 호텔이 처음으로 상업적으로 제공했습니다.[152]그것은 로티(차파티), 달, 쌀 그리고 샤크(요리된 야채, 때때로 카레와 함께)로 구성되어 있고 피클과 구운 파파드가 곁들여져 있습니다.달콤한 요리로는 라두, 망고, 베드미가 있습니다.도클라스, 플라자, 데브라스는 아메다바드에서 일반적으로 소비되는 음식입니다.[153]음료로는 버터밀크와 차가 있습니다.구자라트는 건조한 상태이기 때문에 아마다바드에서는 술을 마시는 것이 법적으로 금지되어 있습니다.[154]

인도 음식과 국제 음식을 제공하는 많은 식당들이 있습니다.수세기에 걸쳐 도시의 자인과 힌두 공동체에 의해 유지되어 온 채식주의의 강한 전통이 존재하기 때문에, 대부분의 음식점들은 채식주의 음식만을 제공합니다.[155]세계 최초의 채식주의 피자헛이 아메다바드에 문을 열었습니다.[156]KFC는 채식 품목을 제공하기 위한 별도의 직원 유니폼을 가지고 있으며 맥도날드처럼 별도의 주방에서 채식 음식을 준비합니다.[157][158][159][160]아메다바드에는 바티야르 갈리, 칼루푸르, 자말푸르와 같은 오래된 지역에서 전형적인 무글라이 비채식 음식을 제공하는 많은 레스토랑이 있습니다.[161]

Manek Chowk은 도시 중심부 근처에 있는 탁 트인 광장으로 아침에는 채소 시장, 오후에는 보석 시장으로 기능합니다.하지만 저녁에는 길거리 음식을 파는 노점상들의 거대한 집합체가 되는 것으로 가장 잘 알려져 있습니다.이것은 힌두교 성인인 바바 마네나트의 이름을 따 지어졌습니다.[162]아메다바드의 일부 지역은 그들의 민속 예술로 알려져 있습니다.랑겔라폴의 장인들은 넥타이로 염색한 반디니스를 만들고, 마두푸라의 코블러 가게는 전통적인 모즈디(모즈리라고도 함) 신발을 팝니다.힌두교의 신 가네샤의 우상과 다른 종교적 아이콘들은 굴바이 테크라 지역의 장인들에 의해 대량으로 만들어집니다.2019년에는 사바르마티 강에서 전통적인 석고 오브 파리 아이돌을 수몰시키는 효과에 대한 인지도가 높아져 친환경 아이돌에 대한 수요가 급증했습니다.[163]Law Garden에 있는 가게들은 거울로 만든 수공예품들을 팝니다.[128]

구자라트 문학 진흥을 위해 아메다바드에 세 개의 주요 문학 기관이 설립되었습니다.구자랏 비디야 사바와 구자랏 사히티야 패리샤드와 구자랏 사히티야 사바입니다.삽탁음대 축제는 새해 첫 주에 열립니다.이 행사는 라비 샹카르(Ravi Shankar)에 의해 시작되었습니다.[164][165]

르 코르뷔지에가 설계한 아메다바드의 여러 건물 중 하나인 산스카 켄드라(Sanskar Kendra)는 아메다바드의 역사, 예술, 문화, 건축 등을 전시하는 박물관입니다.간디 스마라크 상그라할라야와 사르다르 발라브하이 파텔 국립 기념관에는 구자라트 태생의 인도 독립운동 지도자 마하트마 간디와 사르다르 파텔과 관련된 사진, 문서 및 기타 기사들이 영구적으로 전시되어 있습니다.칼리코 직물 박물관에는 인도 및 국제 직물, 의류 및 직물의 많은 컬렉션이 있습니다.[166]하즈라트 피르 모하마드 샤 도서관에는 아랍어, 페르시아어, 우르두어, 신디어, 터키어로 된 희귀한 원본 원고 모음집이 있습니다.[citation needed]베차르 도구 박물관은 스테인리스 스틸, 유리, 황동, 구리, 청동, 아연 그리고 독일 은 도구들을 전시하고 있습니다.[167][168]컨플렉토리움은 예술을 통해 사회의 갈등을 탐구하는 인터랙티브 설치 공간입니다.

슈레이아스 재단은 캠퍼스에 4개의 박물관을 가지고 있습니다.슈레이아스 민속 박물관(로카야탄 박물관)에는 다양한 구자라트 공동체의 예술 형식과 예술품이 있습니다.칼파나 망갈다스 어린이 박물관에는 장난감, 인형, 춤과 드라마 의상, 동전, 전세계 전통 쇼에서 녹음된 음악의 저장소가 있습니다.카하니는 구자라트의 박람회와 축제 사진을 소장하고 있습니다.Sangeeta Vadyakhand는 인도와 다른 나라들의 악기들의 갤러리입니다.[169][170][171]

L.D.인도학 연구소는 76,000개의 자인 원고와 500개의 삽화가 있는 판본, 45,000권의 인쇄된 책들을 소장하고 있으며, 자인 원고, 인도 조각, 테라코타, 미니어처 회화, 천화, 채색 두루마리, 청동, 목공예, 인도 동전, 직물, 장식 예술의 가장 큰 수집품이 되고 있습니다.라빈드라나트 타고르의 그림과 네팔과 티벳의 예술 [172]작품들더 엔씨.메타 미니어처 페인팅 갤러리에는 인도 전역에서 온 화려한 미니어처 페인팅과 원고들의 컬렉션이 있습니다.[173]

1949년 과학자 비크람 사라바이 박사와 그의 아내 바라트 나띠얌 무용수 므리날리니 사라바이가 다르파나 공연예술아카데미를 설립했습니다.그 영향으로 아마다바드는 인도 고전 무용의 중심지가 되었습니다.[174]

교육

아메다바드의 식자율은 2001년 79.89%에서 2011년 89.62%로 높아졌습니다.2011년 현재, 남성과 여성의 식자율은 각각 93.96 퍼센트와 84.81 퍼센트였습니다.

아마다바드의 여러 대학 중 구자라트 대학교가 가장 크고 가장 오래된 대학이라고 주장합니다.[175] 비록 구자라트 비디아피스는 1920년 마하트마 간디에 의해 설립되었지만 영국 라지 (Raj)로부터 인가를 받지 못했고 1963년에야 대학교로 간주되었습니다.[176]그 도시의 많은 대학들이 구자라트 대학과 제휴하고 있습니다.

구자라트 공과대학, CEPT 대학, 니르마 대학, 인프라 기술 연구 및 관리 연구소(IITRAM), 아흐메다바드 대학 모두 금세기부터 존재합니다.Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University에는 원격 교육 과정에 등록된 10만 명이 넘는 학생들이 있습니다.[177][178]

아흐메다바드에는 인도 경영연구소 아흐메다바드가 위치해 있으며, 2018년 인적자원개발부가 선정한 인도 내 경영기관 중 1위를 차지했습니다.[179]

1947년 아메다바드에서 가장 오래된 연구소인 과학자 비크람 사라바이(Vikram Sarabhai)에 의해 설립된 물리연구소는 우주과학, 천문학, 고에너지 물리학 및 기타 연구 분야에서 활발한 활동을 하고 있습니다.[180]다르파나 공연 예술 아카데미는 유네스코에 의해 "세계 문화 및 자연 유산 보호"에 적극적인 기관으로 등재되었습니다.[181][182]

아메다바드의 학교들은 AMC에 의해 공개적으로 운영되거나, 법인, 신탁 및 기업에 의해 개인적으로 운영됩니다.대부분의 학교들은 구자라트 고등 교육 위원회에 소속되어 있지만, 일부 학교들은 중등 교육을 위한 중앙 위원회, 인도 학교 자격증 시험을 위한 위원회, 국제 바칼로레아 및 국립 개방 학교 기관에 소속되어 있습니다.

미디어

아흐메다바드의 신문에는 타임즈 오브 인디아, 인디아 익스프레스, DNA, 이코노믹 타임즈, 파이낸셜 익스프레스, 아흐메다바드 미러, 메트로와 같은 영어 일간지가 포함되어 있습니다.[183]다른 언어로 된 신문에는 디비야 바스카, 구자라트 사마차르, 산데쉬, 라자스탄 파트리카, 삼바브, 아안호데키 등이 있습니다.[183]이 도시는 1919년 마하트마 간디가 설립한 역사적인 나바지반 출판사의 본거지입니다.[184]

국영 전인도 라디오 아메다바드는 중파 대역과 FM 대역(96.7MHz)으로 도시에서 방송됩니다.[185]라디오 시티(91.1 MHz), 레드 FM(93.5 MHz), 마이 FM(94.3 MHz), 라디오 원(95.0 MHz), 라디오 미르치(98.3 MHz), 미르치 러브(104 MHz) 등 5개의 민간 지역 FM 방송국과 경쟁하고 있습니다.Gyan Vani (104.5 MHz)는 미디어 협력 모델에 따라 운영되는 교육용 FM 라디오 방송국입니다.[186]2012년 3월 구자라트 대학교는 90.8 MHz의 캠퍼스 라디오 서비스를 시작했는데, 이는 주에서 처음이자 인도에서 다섯 번째로 진행된 것입니다.[187]

국영 텔레비전 방송국인 Doordarshan은 무료 지상파 채널을 제공하고, In Cablenet, Siti Cable 및 GTPL의 3개 멀티 시스템 사업자는 구자라트어, 힌디어, 영어 및 기타 지역 채널을 케이블을 통해 혼합하여 제공합니다.[188]전화 서비스는 지오, BSNL 모바일, 에어텔, 보다폰 아이디어 등 유선 및 이동 통신 사업자가 제공합니다.[189]

경제.

아메다바드의 국내 총생산은 2014년에 640억 달러로 추정되었습니다.[190][191]RBI는 2012년 6월 기준으로 아메다바드를 전국에서 7번째로 큰 예금 센터와 7번째로 큰 신용 센터로 평가했습니다.[192]19세기에 섬유와 의복 산업은 강력한 자본 투자를 받았습니다.1861년 5월 30일 란초달 초탈은 최초의 인도 직물 공장인 아메다바드 방적 및 직조 회사 유한회사를 설립하고 [193]칼리코 밀스, 바기차 밀스 및 아르빈드 밀스와 같은 일련의 직물 공장을 설립했습니다.1905년까지 도시에는 약 33개의 방직 공장이 있었습니다.[194]제1차 세계대전 중 섬유산업은 급속한 성장을 이루었고 인도산 제품의 구매를 촉진한 마하트마 간디의 스와데시 운동의 영향을 받았습니다.[195]아메다바드는 직물 산업으로 "동양의 맨체스터"로 알려져 있습니다.[54]이 도시는 데님의 최대 공급처이자 인도에서 가장 큰 원석과 보석 수출국 중 하나입니다.[18]자동차 산업 또한 이 도시에 중요합니다. Tata의 Nano 프로젝트 이후 포드, 스즈키, 푸조는 아마다바드 근처에 엔진 및/또는 차량 제조 공장을 설립했습니다.[196][197][198]

암바바디 지역에 위치한 아메다바드 증권거래소는 인도에서 두 번째로 오래된 증권거래소입니다.지금은 없어졌습니다.[199]인도에서 가장 큰 두 제약회사인 자이더스 카딜라와 토렌트 제약회사가 이 도시에 기반을 두고 있습니다.세제와 화학 산업 단위를 운영하는 니르마 산업 그룹은 그 도시에 회사 본사를 두고 있습니다.그 도시에는 다국적 무역 및 인프라 개발 회사인 아다니 그룹의 회사 본사가 있습니다.[200]댐과 운하의 사르다르 가로바르 프로젝트는 도시를 위한 식수와 전기 공급을 향상시켰습니다.[201]정보 기술 산업은 아메다바드에서 크게 발전하여 Tata Consultancy Services와 같은 회사들이 아메다바드에 사무실을 열었습니다.[202]2002년 NASCOM에서 IT 지원 서비스를 위한 "Super Nine Indian Destinations"에 대해 조사한 결과, 아메다바드는 인도에서 가장 경쟁력 있는 9개 도시 중 5위를 차지했습니다.[203]이 도시의 교육 및 산업 기관들은 인도의 나머지 지역에서 학생들과 젊은 숙련 노동자들을 끌어 모았습니다.[204]아메다바드에는 카딜라 헬스케어, 라스나, 와그 바크리, 니르마, 카딜라 파마슈티컬스, 인타스 바이오 제약 등 인도의 주요 기업들이 입주해 있습니다.아메다바드는 뭄바이 다음으로 인도에서 두 번째로 큰 면직물 중심지이며 구자라트에서 가장 큰 도시입니다.[205]많은 면화 제조 회사들이 아마다바드와 그 주변에서 운영되고 있습니다.[206][207][208][209][210]직물은 그 도시의 주요 산업 중 하나입니다.[211]구자라트 산업개발공사는 아흐메다바드의 산과 탈루카에 있는 토지를 인수하여 3개의 새로운 산업단지를 설립했습니다.[212]

교통.

항공사

도심에서 15km(9.3mi) 떨어진 Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel 국제공항은 Ahmedabad와 인접한 주도 Gandhinagar로 가는 국내선과 국제선을 제공합니다.[213]이 공항은 구자라트에서 가장 붐비는 공항이며 승객 수송 면에서는 인도에서 7번째로 붐빕니다.[214]아메다바드 공항은 이전에 인도 공항청에 의해 관리되었으며 2020년 11월 운영 및 유지보수를 위해 도시에 기반을 둔 아다니 그룹에 임대되었습니다.[215]돌레라 국제공항은 현재 페다라 인근에 건설될 계획입니다.총 면적이 7,500헥타르에 달하는 인도에서 가장 큰 공항이 될 것입니다.[216]

수상기

2020년 10월 31일, 인도 최초의 수상 비행기가 아메다바드와 케바디아의 유니티 여신상 사이에서 운항을 시작했습니다.이 19인승 비행기는 두 목적지를 매일 네 번 왕복합니다.[217]

레일

아메다바드는 서부 철도 지역의 6개 운영 부서 중 하나입니다.[218]지역적으로 칼루푸르 역으로 알려진 아메다바드 기차역은 다른 교외 철도역과 차별화되는 주요 종착역입니다.[citation needed]구자라트와 서부 철도 지역의 기차역의 중심지입니다.많은 노선들이 구자라트와 인도의 여러 지역들과 연결되는 이 도시에서 출발합니다.사바르마티 분기점, 마니나가르, 간디그람, 아사르바, 찬들로디야와 같은 다른 도시들과 연결되는 다른 주요 역들도 있습니다.

아메다바드 지하철

아메다바드 지하철은 2015년 3월에 건설을 시작했습니다.[219][220][221][222] 아메다바드 지하철의 1단계 길이는 40km입니다. 6.5km는 지하에 있고 나머지 구간은 고가입니다.[223]나렌드라 모디 총리는 2019년 3월 4일 바스트랄 감과 어패럴 파크 사이의 첫 구간을 개통하였고, 2019년 3월 6일 대중에게 공개되었습니다.[224]나머지 1단계는 2022년 9월 30일에 시작되었습니다.[225]2단계 건설은 간디나가르를 연결하는 2021년에 시작되었습니다.[226]

도로

국도 48호선이 아마다바드를 지나 뉴델리, 뭄바이와 연결됩니다.국도 147호선은 아메다바드와 간디나가르를 연결합니다.그것은 두 개의 출구가 있는 94 km (58 mi) 길이의 고속도로인 국도 1호선을 통해 바도다라와 연결됩니다.이 고속도로는 골든 쿼드러플 프로젝트의 일부입니다.[227]

2001년, 아메다바드는 중앙오염통제위원회가 선정한 85개 도시 중 인도에서 가장 오염이 심한 도시로 선정되었습니다.구자라트 오염통제위원회는 오염을 줄이기 위해 아메다바드에 있는 37,733대의 모든 자동차 인력거의 연료를 더 깨끗한 압축 천연 가스로 전환하도록 자동차 인력거 운전자들에게 1만 ₹의 인센티브를 주었습니다.그 결과, 2008년, 아메다바드는 인도에서 50번째로 가장 오염된 도시로 선정되었답니다.[228]

버스

아메다바드 BRTS

아메다바드 BRTS는 이 도시의 버스 고속 교통 시스템입니다.아흐메다바드 시공사 등의 자회사인 아흐메다바드 얀마르그 유한회사가 운영하고 있습니다.[229][230]2009년 10월 개통된 이 네트워크는 2015년 12월까지 89km(55마일)까지 확장되었으며 일일 승객 수는 132,000명입니다.[231]아메다바드 시 교통국(AMTS)은 아메다바드 시 교통국이 운영하는 공공 버스 서비스입니다.[232]750대 이상의 AMTS 버스가 도시를 운행합니다.[232]아메다바드 BRTS는 CNG와 디젤 버스를 제외한 50대의 전기 버스도 운행하고 있습니다.[233]

AMTS

아메다바드 시 교통 서비스는 1947년 4월 1일에 시작된 공공 버스 서비스로 아메다바드 시 교통 공사에서만 운영됩니다.2018년 현재 900대 이상의 버스가 도시의 거의 모든 지역을 커버하고 있습니다.[234]

자전거.

자전거 대여 및 공유 서비스는 2013년 MYBYK에 의해 아메다바드에서 시작되었습니다.이 프로젝트는 200대의 자전거로 시작되었으며 한 BRT 역에서 다른 역으로 통근할 수 있는 자전거를 제공하는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다.2021년 현재 150개의 자전거 허브와 6,000대의 자전거를 보유하고 있으며, 아메다바드는 인도에서 가장 큰 공공 자전거 공유지(PBS) 도시입니다.[235][236]

스포츠

크리켓은 이 도시에서 가장 인기있는 스포츠 중 하나입니다.[237]1982년에 지어진 사르다르 발라브하이 파텔 경기장(Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium)으로 알려진 나렌드라 모디 경기장(Narendra Modi Stadium)은 국제 경기와 테스트 경기를 하루 동안 개최합니다.이 경기장은 132,000명의 관중을 수용할 수 있는 세계에서 가장 큰 경기장입니다.[238]1987년, 1996년, 2011년 크리켓 월드컵을 개최했습니다.[239]국내 대회에 출전하는 1급팀 구자라트 크리켓팀의 홈구장입니다.아메다바드는 구자라트의 아메다바드 시 스포츠 클럽에 두 번째 크리켓 경기장을 가지고 있습니다.[240]

그 밖에 필드하키, 배드민턴, 테니스, 스쿼시, 골프 등이 인기 스포츠입니다.아메다바드에는 9개의 골프장이 있습니다.[241]미타할리 멀티 스포츠 단지는 다양한 실내 스포츠를 홍보하기 위해 아흐메다바드 시립 공사에 의해 개발되고 있습니다.[242]아마다바드는 롤러스케이트와 탁구 국가 레벨 경기도 개최했습니다.[243]포뮬러 원 디자인 컨셉에 기반한 380 미터 길이의 트랙이 소개되면서 카트 경주는 도시에서 인기를 얻고 있습니다.[244][245]

사바르마티 마라톤은 2011년부터 매년 12월부터 1월까지 개최되고 있으며, 풀 마라톤과 하프 마라톤, 7km 드림 달리기, 시각 장애인을 위한 5km 달리기, 5km 휠체어 달리기 등의 카테고리가 있습니다.[246]2007년, 아메다바드는 51번째 국가급 사격 경기를 개최했습니다.[247]2016년 카바디 월드컵은 아메다바드의 더 아레나에서 트란스타디아(칸카리아 축구장을 개조한 것)에 의해 열렸습니다.세계 프로 당구 선수권 대회에서 5번이나 우승하고 인도 최고의 스포츠 상인 라지브 간디 켈 라트나를 받은 게트 세티는 아마다바드에서 자랐습니다.[248]

아다니 아메다바드 마라톤은 아다니 그룹이 2017년부터 매년 주최하고 있으며, 첫 대회에서 8,000명의 참가자를 유치했으며 2020년에는 코로나19 지침에 따라 첫 가상 마라톤 대회를 개최했습니다.[249]

아메다바드 2036 올림픽 유치

아메다바드는 2036년 하계 올림픽의 잠재적인 개최 도시로 확인되었습니다.구자라트 정부는 올림픽 유치를 지원하기 위한 기반시설 개발을 위해 아메다바드와 그 주변에 33개의 장소를 확인했습니다.[250]그 도시의 입찰은 또한 호주의 컨설턴트들을 포함한 국제적인 전문 지식으로 형성되고 있습니다.[251]구자라트 정부는 아마다바드의 올림픽 유치를 관리하기 위해 특수목적차량(SPV)을 설치하고 있습니다.[252]사르다르 발라브하이 파텔 경기장의 운명은 올림픽 준비의 일환으로 고려되고 있습니다.[253]

관광지

유산

모스크와 무덤

- 시디 바시르 모스크-흔들리는 미나렛

- 시디 사이예드 모스크

- 사르케이 로자

- 아흐메드 샤의 모스크

- 하이바트 칸의 모스크

- 자마 모스크

- 아흐마드 샤의 무덤

- 라니노 하지로

- 쿠트부딘 모스크

- 사이야드 우스만 모스크

- 대스투르 칸의 모스크

- 미야 칸 치슈티 모스크

- 아컷 비비의 모스크

- 다리야 칸의 무덤

- 아잠과 무아잠 칸의 무덤

- 쿠투브-에-알람 모스크

- 샤이알람의 로자

- 무하피즈 칸 모스크

- 라니 루파마티 모스크

- 라니 십리 모스크

- 말리크 이산의 모스크

- 모하메드 거스 모스크

- 바바 루루이 모스크

- 와지후딘의 무덤

- 사르다르 칸의 로자

박물관

- 칼리코 직물 박물관

- 랄바이 달팟바이 박물관

- 구자라트 과학도시

- 오토 월드 빈티지 자동차 박물관

스텝웰스

템플스

- 후티싱 자인 사원 - 샤히바우그

- 쉬리 스와미나라얀 만디르 칼루푸르 - 칼루푸르

- 쉬리 자간나트 만디르 - 자말푸르

- 캠프 하누만 만디르 - 샤히바우그

다른이들

주목할 만한 사람들

- 고탐 아다니(Gautam Adani, 1962년 ~ )는 아다니 그룹의 회장이자 설립자입니다.

- 이슬람 학자이자 작가인 알리 셰르 벵갈리(Ali Sher Bengali, 1570년대 사망)

- M.C. 바트 - 인권변호사

- 재스프리트 범라(Jasprit Bumrah, 1993년 ~ ), 크리켓 선수

- Kishore Chauhan - 인도 기업가이자 전자 회사인 Arises India Limited의 설립자

- Alisha Chinai - (1965년생) 인도 팝 앨범과 힌디어 시네마에서 재생 노래로 유명한 인도 팝 가수

- Jhinabhai Desai - Snehrashmi로 더 잘 알려진 구자라트 시인, 작가, 교육자, 정치 지도자, 인도 독립 운동가

- 프라카시 K. 데사이 - 인도 공군 원수

- Prasannavadan Bagwanji Desai - 인도의 인구통계학자, 경제학자, 독립운동가

- Drashti Dhami - 인도의 텔레비전 배우, Get - Hui Sabse Parayi와 Madhubala와 같은 힌디어 TV 시리즈에서 그녀의 역할로 유명합니다 – Ek Ishq Ek Junoon

- 프리츠커 건축상 수상자 B. V. 도시

- 수브라마니암 하리하란 아이어 - 인권변호사

- 가우랑쟈니 - 사회학자

- Naresh Kanodia - 구자라티 영화에서 그의 작품으로 유명한 인도의 배우이자 정치가

- 산지브 쿠마르 - 1970년대 발리우드 영화에서 그의 역할로 유명한 인도 배우

- 슈레니크 카스투르바이 랄바이 - 인도의 사업가이자 자선가로, 인도의 교육과 연구에 기여한 것으로 유명합니다.

- 자베르흐와 메건이 - 구자라트 문학과 구자라트의 민속 문학에 기여한 것으로 유명한 인도 시인, 작가, 자유 투사

- Ketan Mehta - 발리우드와 구자라티 영화계에서 그의 작품으로 유명한 인도 영화 감독

- Sudhir Mehta - 인도의 사업가이자 인도의 선도적인 제약 및 전력 회사인 Torrent Group의 회장

- Rohinton Mistry - 인도계 캐나다 소설가이자 단편 작가

- 나르하리 파리크(Narhari Parikh, 1891년 ~ 1957년 사망), 작가, 활동가, 사회 개혁가

- 기리쉬바이 파텔 - 인권변호사

- Karsanbhai Patel - 인도 억만장자 기업가이자 비누, 세제 및 기타 생활용품을 전문으로 하는 소비재 회사 니르마의 설립자

- Pankaj Patel - 인도의 사업가이자 인도의 대표적인 제약 회사인 Cadila Healthcare의 전 회장

- 스미타 파틸 - 1970년대와 1980년대에 힌디어, 마라티어, 말라얄람 영화에서 작업한 것으로 유명한 인도 여배우.

- 팔구니 파탁 - 인도의 가수이자 공연자로, 나브라트리 기간 동안 인기 있는 단디야와 가르바 공연으로 "단디야의 여왕"으로 알려져 있습니다.

- Amrita Pritam - 펀자브 문학으로 유명한 인도의 작가이자 시인

- 만리카 사라바이(Mallika Sarabhai, 1953년 ~ )는 인도의 클래식 댄서, 안무가, 활동가입니다.

- 비크람 사라바이(Vikram Sarabhai, 1919년 ~ 1971년 사망)는 물리학자이자 천문학자로, 물리연구소를 설립하고 ISRO 설립에 기여했습니다.

- 제이 샤 - BCCI 비서(관리자)

- 코말 샤(미술 수집가), 미술 수집가, 자선가, 컴퓨터 엔지니어, 실리콘 밸리의[254] 사업가

- Naseeruddin Shah - 발리우드와 인도 평행 영화에서 그의 작품으로 유명한 인도 배우이자 감독

- 라비 샹카르 - 인도의 음악가이자 작곡가로, 인도 클래식 음악에서의 그의 업적과 서양의 시타르를 대중화시킨 것으로 유명합니다.

- 헤만트 셰쉬 - 1960년대 인도 국가대표로 활약한 인도 크리켓 선수

- 무쿨 신하 - 인권변호사

- 니르자리 신하 - 인권운동가

- Manhar Udhas - 힌디어, 구자라트어 및 기타 인도 언어 작업으로 유명한 인도 재생 가수

- Achyut Yagnik - 저널리스트, 학자, 활동가

- 요츠나 야그닉 - 판사

- 디샤 바카니 - 인도 텔레비전 배우

국제관계

- 자매도시

아스트라한 주, 아스트라한[255] 주

아스트라한 주, 아스트라한[255] 주 콜럼버스, 오하이오, 미국 (2008)

콜럼버스, 오하이오, 미국 (2008) 광저우, 광둥, 중국 (2014년 9월)[257]

광저우, 광둥, 중국 (2014년 9월)[257] 저지 시티, 뉴저지, 미국 (1994)

저지 시티, 뉴저지, 미국 (1994) 일본 효고현 고베시 (2019년)[259][260]

일본 효고현 고베시 (2019년)[259][260] 바야돌리드, 카스티야 레온, 스페인 (2019)[261]

바야돌리드, 카스티야 레온, 스페인 (2019)[261]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ "Bijal Patel is mayor, Makwana her deputy". The Times of India. 15 June 2018.

- ^ "Gujarat government transport 23 IAS officers; AMC GMC get new commissioners". DeshGujarat. 12 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ "City police chief visits stadium, ashram". The Times of India. 14 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "About Us". Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Gujarāt (India): State, Major Agglomerations & Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Population", worldpopulationreview.com

- ^ Kaushik, Himanshu; Parikh, Niyati (3 January 2019). "GJ-01 series registers 12% drop in one year". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "District Human Development Reports United Nations Development Programme". UNDP. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Distribution of Population, Decadal Growth Rate, Sex-Ratio and Population Density". 2011 census of India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ "Gujarat elections 2022: Seats with high literacy rates record low voting numbers". The Times of India. 8 December 2022. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Haritas, Bhragu (28 June 2017). "Richest Cities Of India". BW Businessworld. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020.

Ahemadabad. The largest city of Gujarat has an estimated GDP of $68 billion.

- ^ Tiwari, Anuj (22 October 2021). "Top 10 Richest Cities in India;". India Times.

The Manchester of East, Ahmedabad, is among the richest cities of India. The city ranks eighth on the list with an estimated GDP of $68 billion.

- ^ Dave, Jitendra (28 March 2012). "Is it Ahmadabad or Amdavad? No one knows for sure". DNA India. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ 인도에서 가장 인구가 많은 도시 https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/cities/india

- ^ a b "India: States and Major Agglomerations – Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Major Agglomerations of the World – Population Statistics and Maps". citypopulation.de. 1 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Ahmadabad & Gandhinagar a tale of twin cities". One India One People. 1 December 2015.

- ^ a b Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (2006). "Profile of the City Ahmadabad" (PDF). Ahmadabad Municipal Corporation Ahmadabad, Urban Development Authority and CEPT University, Ahmadabad. Ahmadabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Ahmadabad joins ITES hot spots". The Times of India. 16 August 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ Kotkin, Joel. "In pictures—The Next Decade's fastest growing cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ "Ahmedabad best city to live in, Pune close second". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Tiwari, Anuj (22 October 2021). "Richest Cities Of India". India Times. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

The Manchester of East, Ahmedabad, is among the richest cities of India. The city ranks eighth on the list with an estimated GDP of $68 billion.

{{cite news}}: CS1 유지 : url-status (링크) - ^ "Ahmedabad rated as third best city to live in, moves up by 20 spots in a year". www.timesnownews.com. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Ahmedabad, India: World's Greatest Places 2022". Time. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Government releases list of 20 smart cities". The Times of India. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "600-year-old smart city gets World Heritage tag". The Times of India. 9 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Ahmedabad History".[영구 데드링크]

- ^ "Ahmedabad".[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Turner, Jane (1996). The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 1. Grove. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-884446-00-9.

- ^ Michell, George; Snehal Shah; John Burton-Page; Mehta, Dinesh (28 July 2006). Ahmadabad. Marg Publications. pp. 17–19. ISBN 81-85026-03-3.

- ^ a b Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India Through the Ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 173.

- ^ Turner, Jane (1996). The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 1. Grove. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-884446-00-9.

- ^ Michell, George; Snehal Shah; John Burton-Page; Mehta, Dinesh (28 July 2006). Ahmadabad. Marg Publications. pp. 17–19. ISBN 81-85026-03-3.

- ^ Wink, André (1990). Indo-Islamic Society: 14th - 15th Centuries. Brill. p. 143. ISBN 978-90-04-13561-1.

Zafar Khan Muzaffar, the first independent ruler of Gujarat was not a foreign muslim but a Khatri convert, of a low subdivision called Tank, originally from Southern Punjab.

- ^ Kapadia, Aparna (2018). In Praise of Kings: Rajputs, Sultans and Poets in Fifteenth-century Gujarat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-107-15331-8.

Gujarati historian Sikandar does narrate the story of Muzaffar Shah's ancestors having once been Hindu "Tanks", a branch of Khatris who trace their dynasty from the solar god.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- ^ a b c More, Anuj (18 October 2010). "Baba Maneknath's kin keep alive 600-yr old tradition". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ 이 모호성은 황제 표트르 1세가 그의 새로운 수도를 "상트페테르부르크"라고 명명한 경우와 유사하며, 공식적으로는 성 베드로를 언급하기도 하지만 사실은 자신을 언급하기도 합니다.

- ^ a b c d e "History of Ahmedabad". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, egovamc.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (14 November 2010). "In Ahmedabad, history is still alive as tradition". dna. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "History". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Jilkad is anglicized name of the month Dhu al-Qi'dah, Hijri year not mentioned but derived from date converter

- ^ Desai, Anjali H., ed. (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9780978951702. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Flags changed at city's foundation by Manek Nath baba's descendants". The Times of India. TNN. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Ruturaj Jadav and Mehul Jani (26 February 2010). "Multi-layered expansion". Ahmedabad Mirror. AM. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "02/26/2015: Divya Bhaskar e-Paper, ahmedabad, e-Paper, ahmedabad e Paper, e Newspaper ahmedabad, ahmedabad e Paper, ahmedabad ePaper". Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ^ Ajay, Lakshmi (27 February 2015). "Ahmedabad city turns 604". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ "Manek Burj's sorry state fails to move AMC". DNA. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Kuppuram, G (1988). India Through the Ages: History, Art, Culture, and Religion. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 739. ISBN 978-81-85067-08-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal Throne. Orion Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7538-1758-2.

- ^ Sangwan, Satpal; Y. P. Abrol; Mithilesh K. Tiwari (2002). Land Use – Historical Perspectives: Focus on Indo-Gangetic Plains. Allied Publishers. p. 151. ISBN 978-81-7764-274-2.

- ^ Prakash, Om (2003). Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement. Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. pp. 282–284. ISBN 81-261-0938-6.

- ^ Kalia, Ravi (2004). "The Politics of Site". Gandhinagar: Building National Identity in Postcolonial India. Univ of South Carolina Press. pp. 30–59. ISBN 1-57003-544-X. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ Iain Borden; Murray Fraser; Barbara Penner (11 August 2014). Forty Ways to Think About Architecture: Architectural History and Theory Today. John Wiley & Sons. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-118-82261-6. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b A. Srivathsan (23 June 2006). "Manchester of India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ Gilly, Thomas Albert; Gilinskiy, Yakov (8 December 2009). The Ethics of Terrorism: Innovative Approaches from an International Perspective (17 Lectures). Charles C Thomas Publisher. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-398-07867-6. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1962). Cities and Civilization. Popular Prakashan. p. 96.

- ^ Acyuta Yājñika; Suchitra Sheth (2005). The Shaping of Modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva, and Beyond. Penguin Books India. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-14-400038-8. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Political Science. FK Publications. 1978. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-89611-86-6. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Wolf, Jr., Charles. "Korea's Five year plan" (PDF). Ministry of Reconstruction of Korea.

- ^ Shah, Ghanshyam (20 December 2007). "60 revolutions—Nav nirman movement". India Today. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Yagnik, Achyut (May 2002). "The pathology of Gujarat". New Delhi: Seminar Publications. Archived from the original on 22 March 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ Sinha, Anil. "Lessons learned from the Gujarat earthquake". WHO Regional Office for south-east Asia. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ "Safehouse of Horrors". Tehelka. 3 November 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ "CNN.com - Desolate life in India's refugee camps - May 15, 2002". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "17 bomb blasts rock Ahmedabad, 15 dead". CNN-IBN. 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ "India blasts toll up to 37". CNN. 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ Langa, Mahesh (23 February 2020). "Ahmedabad glitters to welcome Donald Trump". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Chinese President Xi Jinping arrives in Ahmedabad". The Economic Times. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Justin Trudeau visits IIM A, says empowering women is the smart thing to do". Ahmedabad Mirror. 19 February 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "BPL Census for ninth plan". Ahmedabad District Collectorate. Archived from the original on 24 May 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ "Slum Population in Million Plus Cities". Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 23 December 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- ^ "NRI Directory". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Population 2021 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations". population.un.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Cheers Ahmedabad! City is racing ahead". DNA India. 16 October 2010. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Ahmedabad best city to live in, Pune close second". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ John, Paul (16 October 2005). "Surat crime rate lowest". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ "Ahmedabad best city to live in, Pune close second". The Times of India. 11 December 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Sapovadia, Vrajlal (2007). "A critical study of urban land ownership by an individual vis-à-vis institutional (or community) based ownership—The Impact of type of ownership on spatial growth, efficiency and equity: A case study of Ahmedabad, India" (PDF). Urban Research Symposium 2007. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ^ "Army plans to bridge accommodation deficit for staffers". New India Press. Indo-Asian News Service. 16 September 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2008.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ a b c d e f 바트칼, 탄비, 윌리엄 에이비스, 수잔 니콜라이."아메다바드의 진보에 관한 경고적 이야기", n.d., 48.

- ^ a b 세계은행.2007. 아메다바드의 슬럼 네트워킹 프로젝트: 변화를 위한 파트너링 (영어) 2018년 4월 29일 웨이백 머신에서 보관.물 및 위생 프로그램 사례 연구.워싱턴 DC: 세계 은행.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/353971468259772248/The-Slum-Networking-Project-in-Ahmedabad-partnering-for-change

- ^ SEWA Academy (2002) Parivartan과 그 영향: 아흐메다바드시 빈민가의 인프라 개발 파트너십 프로그램.SEWA 모노그래프.아메다바드:여성 자영업자 협회.

- ^ "Dubai International Award for Best Practices Winners Ahmedabad Slum Networking Programme". mirror.unhabitat.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Mount Carmel Cathedral". Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018. G카톨릭

- ^ "Our Parish". St. Xavier’s Parish, Ahmedabad. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "High ageing rate, health problems worry Parsi community". The Times of India. 22 October 2001. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "인도 아메다바드의 유대인 여러분, 토라 두루마리 환영합니다."웨이백 머신 유대인 저널에 2012년 9월 15일 보관. 2012년 9월 13일. 2012년 9월 13일.

- ^ Katz, Nathan; Ellen S. Goldberg. "The Last Jews in India and Burma". Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2006.

- ^ "Expansion of Municipal Corporations". The Times of India. 19 June 2020. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Municipalities have extension in Gujarat". Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "AMC Expansion". 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Amdavad city". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Gujarat State Gazetteers. Directorate of Govt, Print., Stationery and Publications, Gujarat State. 1984. p. 46.

- ^ "Performance of buildings during the 2001 Bhuj earthquake" (PDF). Jag Mohan Humar, David Lau, and Jean-Robert Pierre. The Canadian Association for Earthquake Engineering. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Historic city of Ahmadabad - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Reader in Urban Sociology. Orient Blackswan. 1991. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-0-86311-152-5. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ "Residential Cluster, Ahmedabad: Housing based on the traditional Pols" (PDF). arc.ulaval.ca/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Patel, Bholabhai (26 February 2011). "અમદાવાદની પોળ સંસ્કૃતિની એક મર્મસ્પર્શી ઝલક" (in Gujarati). Divya Bhaskar. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Tentative Lists". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Dave, Jitendra (28 August 2009). "Ahmedabad heritage set to conquer Spain". Daily News and Analysis. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Vaarso". Ahmedabad Mirror. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Urban Structure and Growth". The Ahmedabad Chronicle: Imprints of a Millennium. Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design. 2002. p. 83.

- ^ "Sabarmati River Front Time line".

- ^ "Ahmedabad records hottest day in century as mercury hits 48 degrees Celcius". Indian Express. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Climatological Table Period: 1981–2010". India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Ever recorded Maximum and minimum temperatures up to 2010" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Climatological Information - Ahmedabad (42647)". India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India". Time and Date. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Climate Normals 1971–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "VAAH Data for May 18, 2016". IEM. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ "Climate and monthly weather forecast Ahmedabad, India". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Climatological Tables 1991-2020" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Chitre, Mandar; Halliday, Adam (3 May 2012). "Weather: Researchers fear 'May 2010 heat wave' may return to city". Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Heat Action Plan – Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation" (PDF). Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ 특징: 인도 아메다바드, 폭염 대비 및 경보 시스템 출시 2013년 6월 4일 웨이백 머신 기후 및 개발 지식 네트워크에서 보관.2013년 7월 31일 회수.

- ^ 인도 도시의 열 관련 위험 해결: 아메다바드의 열 행동 계획 2014년 7월 12일 웨이백 머신, 테하스 샤 박사, 딜리프 마발란카르 박사, 굴레즈 샤 아즈하르 박사, 안잘리 자이스왈 및 메러디스 코놀리, 아메다바드 시립 법인, 인도 공중 보건 연구소-간디나가르 및 천연 자원 방위 위원회, 2014년

- ^ a b B.R. Kishore; Shiv Sharma (2008). India – A Travel Guide. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 491. ISBN 978-81-284-0067-4. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (15 November 2009). "Calico dome: Crumbling crown of architecture". Daily News and Analysis. India. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Shastri, Parth (16 October 2011). "Calico Dome: The icon of its time". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Doshi, Balkrishna V.; Tsuboi, Yoshikatsu; Raj, Mahendra (1967). "Tagore hall". Arts Asiatiques. 60.

- ^ Gans, Deborah (2006). The Le Corbusier guide. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 211–. ISBN 978-1-56898-539-8. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Gargiani, Roberto; Rosellini, Anna (25 November 2011). Le Corbusier: Beton Brut and Ineffable Space (1940–1965): Surface Materials and Psychophysiology of Vision. EPFL Press. pp. 417–. ISBN 978-0-415-68171-1. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Christopher Charles Benninger Architects". Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "He was a teacher and an institution". The Times of India. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Law Garden Night Market". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Endangered species Identified for breeding and their species coordinator". Central Zoo Authority India. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ Ward, Philip (1998). Gujarat-Daman-Diu. Orient Longman Limited. ISBN 9788125013839. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (2 April 2012). "Reminiscing the Kankaria Lake of yore". DNA India. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Jadav, Ruturaj (14 April 2010). "City of lakes-With 34 new lakes under development, Ahmedabad is set to pose a challenge to Udaipur". Ahmedabad Mirror. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Vastapur lake travel guide". Trodly. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ '정글 아웃 더 데어(sic)'입니다.인디안 익스프레스, 2013년 8월 18일

- ^ "Chandola Lake". ahmedabad.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012.

- ^ "Get ready to pay entry fee at Naroda Lake". dna. 11 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ "VCCCI". vccci.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ Mahadevia, Darshin (2008). Inside the Transforming Urban Asia: Processes, Policies and Public Actions (1. publ. ed.). New Delhi: Concept. p. 650. ISBN 978-81-8069-574-2. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Ahmedabad: Air purifiers to be installed near Pirana dumping site for traffic police". dna. 8 February 2019. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Bijal Patel appointed city Mayor". Ahmedabad Mirror. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Nair, Ajesh. "Annual Survey of India's City-Systems" (PDF). janaagraha.org. Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Ahmedabad registers two accidents per hour and Gujarat 18: EMRI 108". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "CCRS". www.amccrs.com. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Delimitation order announced: Ahmedabad to have 48 wards". The Indian Express. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "City Information". aai.aero/. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Saikia new Ahmedabad police chief". The Indian Express. 20 October 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ Dasgupta, Manas (25 September 2008). "Civil Hospital planned as world's biggest hospital". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Group Companies—The Ahmedabad Electricity Company Limited". Torrent Group. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ Vedavalli, Rangaswamy (13 March 2007). Energy for Development: Twenty-first Century Challenges of Reform and Liberalization in Developing Countries. Anthem Press. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-1-84331-223-9. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Lacklustre Uttarayan for kite sellers due to demand slump". The Indian Express. 13 January 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Festive fervour high as people gear up for Navratri celebrations". The Indian Express. 20 September 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ O'Brien, Charmaine (2013). The Penguin Food Guide to India. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-93-5118-575-8. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Dalal, Tarla (2003). The Complete Gujarati Cookbook. Sanjay & Co. p. 4. ISBN 81-86469-45-1. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Naomi Canton (17 August 2017). "We're beneficiaries of reverse colonialism: Boris". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Food – IIMA". iimahd.ernet.in. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Made for India: Succeeding in a Market Where One Size Won't Fit All". India Knowledge@Wharton. The Wharton School. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "KFC in Ahmedabad". Burrp.com Network 18. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Nair, Avinash (17 October 2011). "Kentucky Friend [sic] Chicken changes dress code for vegeterian [sic] Gujarat". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Hum dono hai alag alag" (PDF). press release. McDonald's India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Mcdonald's in Ahmedabad". Burrp.com Network 18. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Food". Outlook Traveller. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Anjali H. Desai (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-9789517-0-2. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Paniker, Shruti (31 August 2019). "Go green with Ganesha". Ahmedabad Mirror. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Schedule of Virasat — virasatfestival.org" (PDF). virasatfestival.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Saptak Music Festival". Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "The Calico Museum of Textiles". Calicomuseum.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Vechaar Utensils Museum". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Kaushalam. "Vechaar ~ Utensils Museum Vishalla Environmental Center for Heritage of Art Architecture and Research". vechaar.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Shreyas Folk Museum". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "Shreyas Foundation". Shreyasfoundation.in. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "Lokayatan Folk Museum". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "L D Museum of Indology". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "N C Mehta Gallery". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "Dancer, patron of the arts Mrinalini Sarabhai: Her feet are footsteps in Ahmedabad's history". The Indian Express. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ "Gujarat University". gujaratuniversity.org.in. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013.

- ^ "Gujarat Vidyapith: History". Gujarat Vidyapith. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ "List of University (State wise)—Gujarat". University Grants Commission, India. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2006.

- ^ "Introduction". baou.edu.in. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017.

- ^ "MHRD, National Institute Ranking Framework (NIRF)". nirfindia.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Jain, R.; Dave, H.; Deshpande, M. R. (September 2001). "Solar X-ray Spectrometer (SoXS) development at Physical Research Laboratory/ISRO". Solar Encounter. Proceedings of the First Solar Orbiter Workshop. European Space Agency. 493: 109. Bibcode:2001ESASP.493..109J. 비브코드:2006JAPA...27..175J

- ^ "Intangible Cultural Heritage" (PDF). UNESCO. 5 February 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2017.

- ^ "Decision of the Intergovernmental Committee: 2.COM 4 – intangible heritage – Culture Sector". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Ahmedabad Newspapers". All you can read. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Gandhi copyright breathes life into Navjivan Trust". The Times of India. 1 October 2003. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "requency Schedule for 30 March 2008 to 26 October 2008". All India Radio. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Gyan Vani to be expanded". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 July 2001. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Ahmed, Syed Khalique (31 March 2012). "GU launches first campus FM radio station in state, fifth in country". The Indian Express. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Jha, Paras (24 November 2010). "Historic silence: Staff strike switches off Akashvani, Doordarshan in Gujarat". DNA India. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ Haslam, Catherine. "A Guide to India's Telecom Market". lightreading.com. Light reading Asia. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Engineering Expo – Ahmedabad". mpponline.in. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

Total GDP of Ahmedabad is 64 Billion

- ^ "Know the 10 most developed Indian cities based on GDP". IndiaTVNews. 9 January 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

Ahmedabad. This largest industrial hub in Gujarat contributes a GDP of about $64 billion.

- ^ "Top 10 Indian Cities and Their Major Industrial Activities". Listice. 3 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Textile industry of Ahmedabad". Ahmedabad Textile Mills' Association. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ "History of textile industry in Ahmedabad". Textile Association of India. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Industry and Commerce". The Ahmedabad Chronicle: Imprints of a Millennium. Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design. 2002. p. 34.

- ^ "Groundbreaking performed for Peugeot plant at Sanand site in Gujarat". deshgujarat.com. 2 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Suzuki to pick Gujarat for new $1.3 bln plant". The Economic Times. Reuters. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Ford bets big on India, to build plant in Gujarat". Reuters. 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "ASE to sell off iconic Manekchowk building". DNA India. 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Adani Group locations". Adani.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Narmada water reaches Ahmedabad". Business Line. Chennai, India. 14 March 2001. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Tiku, Nitasha (11 December 2007). "Ahmedabad, Kolkata among new global hotspots". Rediff. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Ahmedabad joins ITES hot spots". The Times of India. 16 August 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ "About Ahmedabad". ozoneindiagroup. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Chand, Smriti (9 December 2013). "Cotton Textile Industry in India: Production, Growth and Problems". Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Soma Textiles & Industries, Ltd". Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Kumar Textile Industries". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Textiles:: Reliance Industries Limited". Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Growth of Cotton Textile Industry in Ahmedabad". Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Singh, Vipul (2009). Longman Vistas 8. Pearson Education India. p. 174. ISBN 978-81-317-2910-6. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Mehta, Makrand (1982). The Ahmedabad Cotton Textile Industry: Genesis and Growth. New Order Book Co.

- ^ Dave, Kapil (15 May 2011). "Six new GIDC estates to come up in Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Routes to/from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport". Our Airports. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Traffic News for the month of March 2019: Annexure-II" (PDF). Airports Authority of India. 1 May 2019. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Adani Group takes over Ahmedabad airport on lease for 50 years, starts operations". www.businesstoday.in. 8 November 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Federa, father of all airports". The Times of India. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Langa, Mahesh; Chandra, Jagriti (31 October 2020). "PM Modi inaugurates seaplane services to Statue of Unity". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Organisation". Western Railways. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ "New firm to speed up Metro in Ahmedabad". Daily News and Analysis. 2 May 2009. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ DeshGujarat (14 March 2015). "First 6 km works of Ahmedabad Metro to be completed by September 2016:CM". DeshGujarat. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Metro set to roll by October 2017". The Times of India. 12 December 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "IL&FS; Engineering Services Bags Rs. 374.64 Cr Metro Rail Contract in Gujarat". The Hans India. 15 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Rai, Neha (30 August 2018). "The Metro Mechanism of Ahmedabad". Ashaval.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "PM Modi Flags Off Ahmedabad Metro, Takes Inaugural Ride". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "PM Modi to launch Ahmedabad Metro Phase 1, flag off Vande Bharat Express during two-day Gujarat visit". 28 September 2022.

- ^ "'Very important gifts for Ahmedabad, Surat': PM Modi launches metro rail projects in Gujarat". Times Now. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "PM flags off Ahmedabad expressway". Business Line. 30 January 2003. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ "Ahmedabad riding clean fuel wave to healthier future". The Economic Times. India. 10 August 2008. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ "About-Ahmedabad Janmarg Ltd". Ahmedabad BRTS. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Ahmedabad BRTS:Urban Transport Initiatives in India: Best Practices in PPP" (PDF). National Institute of Urban Affairs. 2010. pp. 18–48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "City's BRTS didn't enhance public transport usage". The Times of India. 5 January 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Highlights of Ahmedabad civic budget 2009–10". Desh Gujarat. 3 February 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Ahmedabad BRTS electric bus". Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "Gujarat govt approaches HC for purchase of heavy diesel vehicles - ET Auto". ETAuto.com. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Parikh, Niyati (15 June 2021). "Amdavadi firm aims to make city country's bicycle capital Ahmedabad News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Parikh, Niyati (20 June 2021). "The 'cycling' shift in Ahmedabad". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Sports in Ahmedabad". ahmedabadonline. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "All about Motera stadium, the largest cricket stadium in the world". The Hindu. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Indian Grounds". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Sardar Patel Stadium". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ Kaushik, Himanshu (20 January 2007). "Five more golf courses to tee off in state". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Manish, Kumar (23 September 2007). "Multi-crore sports complex in city". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Looking to Feature". Sports Authority of Gujarat. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Menon, Lekha (23 November 2004). "No sense of adventure". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Karting". J K Tyres. Archived from the original on 16 July 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Sabarmati Marathon Official Website-Race Categories". sabarmatimarathon.net. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "National Shooting C'ships to be held at Ahmedabad". Press Trust of India. 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Geet Sethi Profile". Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Fourth edition of Ahmedabad Marathon goes virtual with app-based remote running". Hindustan Times. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Ahead of Olympics bid, Gujarat identifies 33 sites". Times of India. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Aussie flair to shape Ahmedabad bid for 2036 Olympics". Times of India. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Gujarat govt to set up SPV for Ahmedabad's 2036 Olympic Games bid". Desh Gujarat. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "As Ahmedabad preps for Olympics 2036, AMC in quandary about Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium's fate". Times Now News. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Sheets, Hilarie M. (22 March 2023). "Komal Shah, Champion of Female Artists, Works to Raise Their Profiles". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Upadhyay, Dadan (9 December 2015). "Modi to reconnect in Russia with Astrakhan". www.rbth.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "The India Connection: Local leaders work to grow Columbus' robust Indian business community". Columbus CEO. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Sanyal, Anindita (15 May 2015). "India Gets 3 Sister Cities in China, and One Sister Province". NDTV. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Sister City Agreements". data.jerseycitynj.gov. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Kobe, Ahmedabad to be sister cities". The Times of India. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Sister City Partnership: LoI shared between Ahmedabad and Kobe". Current Affairs Today. 28 June 2019. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "City's got a Spanish sister". 6 July 2017. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

추가열람

- 묵티라지 차우한과 카말리카 보스.인도 실내디자인의 역사 제1권: Ahmedabad (2007) ISBN 81-904096-0-3

- Kenneth L. Gillion (1968). Ahmedabad: A Study in Indian Urban History. University of California Press. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv. A History of Important Ancient Towns and Cities in Gujarat and Kathiawad (From the Earliest Times Down to the Moslem Conquest). ASIN B0008B2NGA.

- Crook, Nigel (1993). India's Industrial Cities: Essays in Economy and Demography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-563172-2.

- Rajan, K. V. Soundra (1989). Ahmadabad. Archaeological Survey of India.

- Forrest, George William. Cities of India. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-93823-9.

- Gandhi, R (1990). Patel: A Life. Navajivan Press, Ahmedabad. ASIN B0006EYQ0A.

- Michell, George (2003). Ahmadabad. Art Media Resources. ISBN 81-85026-03-3.

- Spodek, Howard (2011). Ahmedabad: Shock City of Twentieth-Century India. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35587-4.

외부 링크

- Ahmedabad Collectorate 2011년 7월 21일 Wayback Machine에서 보관

- 아메다바드 앳 컬리

- 아마다바드 백과사전 æ디아 브리태니커 출품작

- 245711197 아메다바드(Amedabad) 오픈 스트리트 맵(OpenStreet Map)