영국 미술

English art| 영국의 문화 |

|---|

|

| 역사 |

| 사람 |

| 언어들 |

| 요리. |

| 종교 |

| 예체능 |

| 문학. |

영국 예술은 영국에서 만들어진 시각 예술이다.영국에는 유럽에서 가장 초기의 최북단 빙하기 동굴 벽화가 [1]있다.영국의 선사시대 미술은 대체로 현대 영국의 다른 곳에서 만들어진 미술과 일치하지만, 초기 중세 앵글로색슨 미술은 뚜렷한 [2]영국 양식의 발전을 보았고, 그 이후로도 영국 미술은 독특한 성격을 띠기 위해 계속되었다.1707년 대영제국의 성립 이후에 만들어진 영국 예술은 대부분의 면에서 동시에 영국의 예술로 간주될 수 있다.

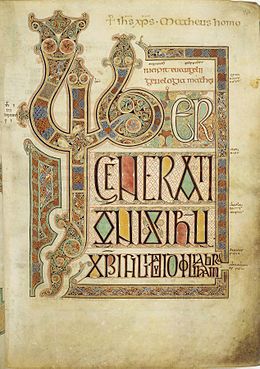

중세 영국 회화는 주로 종교적인 것으로, 강한 국가적 전통을 가지고 있었고 [3]유럽에서 영향력이 있었다.예술에 반감을 품었던 영국의 종교개혁은 이 전통을 갑자기 중단시켰을 뿐만 아니라 거의 모든 [4][5]벽화를 파괴하는 결과를 초래했다.지금은 빛을 발한 원고만이 대량으로 남아 있다.[6]

영국 르네상스의 예술은 초상화에 대한 강한 관심을 가지고 있으며, 초상화 미니어처는 다른 어느 [7]곳보다 영국에서 인기가 있었다.영국의 르네상스 조각은 주로 건축과 기념비적인 [8]무덤을 위한 것이었다.영국 풍경화에 대한 관심은 1707년 연합법이 제정될 무렵부터 [9]발전하기 시작했다.

특히 미술학자 니콜라우스 페브스너와 미술사학자 로이 스트롱은 영국 미술의 [10]실질적인 정의를 시도했다. 예술에 대한 이야기 역사)[11]이자 비평가인 피터 애크로이드(2002년 [12]그의 책 Albion에서).

초기 예술

유럽에서 가장 초기이자 최북단 동굴 미술품인 최초의 영국 미술품은 13,000년에서 15,000년 [13]전으로 추정되는 더비셔의 크레즈웰 크랙스에 있습니다.2003년, 사슴, 들소, 말, 그리고 새나 새 머리를 가진 사람들을 묘사한 80개 이상의 판화와 부조가 그곳에서 발견되었다.스톤헨지의 유명한 거대한 의식 풍경은 기원전 [14]2600년경 신석기 시대로 거슬러 올라간다.기원전 2150년경부터 비커인들은 청동 만드는 법을 배웠고 주석과 금을 모두 사용했다.그들은 금속 정련에 능숙해졌고 무덤이나 제물 구덩이에 안치된 그들의 예술 작품들은 [15]살아남았다.철기 시대에는 켈트족 문화로서 새로운 예술 양식이 등장하여 영국 섬 전체에 퍼졌다.금속 세공품, 특히 금 장신구가 여전히 중요했지만, 돌과 [16]나무도 사용되었을 것이다.이 양식은 기원전 1세기부터 로마 시대까지 이어져 중세 시대에 부흥기를 맞았다.로마의 도래는 많은 기념물, 특히 장례 기념물, 조각상, 흉상 등 많은 기념물이 남아 있는 고전적인 양식을 가져왔다.그들은 또한 유리 세공품과 모자이크를 [17]가져왔다.4세기에 영국에서 기독교 미술이 처음 만들어지면서 새로운 요소가 도입되었다.기독교의 상징과 그림이 새겨진 모자이크는 여러 개 [18]보존되어 있다.영국은 몇몇 주목할 만한 선사시대 언덕의 인물들을 자랑한다; 유명한 예는 옥스퍼드셔에 있는 유핑턴 화이트호스이다. 그것은 "3,000년 이상 동안...미니멀리즘 예술의 [19]걸작으로 소중히 여겨져 왔다"고 말했다.

초기 미술품: 갤러리

Uffington White Horse;[22] 기원전 1000년경.

Winchester Hards 아이템: 기원전 75-25년.[23]

중세 미술

로마 통치 이후, 앵글로 색슨 예술은 서튼 [25]후의 금속 작품에서 볼 수 있는 것처럼 게르만 전통들의 통합을 가져왔다.앵글로색슨 조각은 적어도 남아 [26]있는 거의 모든 상아나 뼈로 된 작은 작품에서 당대에 두드러졌다.특히 노섬브리아에서, 바이킹의 습격과 침략이 운동을 [27]크게 억제하기 전까지, 영국 열도에 걸쳐 공유된 섬나라 미술 양식은 유럽에서 가장 훌륭한 작품을 만들어냈다; 린디스판 책은 노섬브리아에서 [28]확실히 제작된 한 예이다.앵글로색슨 미술은 특히 금속 세공과 성 에델월드의 [29]베네딕토전과 같은 조명된 필사본에서 보여지는 현대 콘티넨탈 양식에서 매우 정교한 변형을 발전시켰다.우리가 알고 있는 대규모 앵글로색슨 회화와 조각품들은 아직 [30]남아있지 않습니다.

11세기 전반까지, 영국 미술은 귀금속의 [31]모든 작품들을 가장 중요시하는 부유한 앵글로색슨계 엘리트들의 아낌없는 후원으로부터 이익을 얻었다. 그러나 1066년 노르만 정복은 이 예술 붐을 갑자기 중단시켰고, 대신 작품들은 [32]녹아버리거나 노르망디로 옮겨졌다.소위 Bayeux Tapestry라고 불리는 이 옷은 노르만 정복에 이르는 사건들을 묘사하고 있는 영국의 커다란 자수 천으로 11세기 [33]후반으로 거슬러 올라간다.노르만 정복 후 몇 십 년 후, 영국의 원고 그림은 곧 다시 유럽의 최고 작품들 중 하나가 되었다; 윈체스터 성경과 세인트루이스와 같은 로마네스크 작품들. 알반스 시편, 그리고 티크힐 [34]시편과 같은 초기 고딕 양식의 시편.그 시대의 가장 잘 알려진 영국 조명가는 매튜 파리이다.[35]웨스트민스터 리터블과 윌튼 딥티치와 같은 영국 중세 판넬 그림의 희귀한 사례들 중 일부는 최고 [36]품질의 것이다.14세기 후반부터 16세기 초반까지 영국은 [37]북유럽 전역에 수출된 중간 시장 제단 조각과 작은 조각상들을 위한 노팅엄 알라바스터 부조에 상당한 산업이 있었다.교회를 통해 소개된 또 다른 예술 형태는 스테인드 글라스였는데, 이 또한 세속적인 [38]용도로 채택되었다.

중세 미술: 갤러리

이른바 Bayeux Tapestry (1070년대)[42]의 상세.

16세기와 17세기

"영국 [54]회화의 첫 원주민 태생의 천재"인 니콜라스 힐리어드 (1547년경-1619년 1월 7일)는 초상화 [55]축소판에서 강한 영국 전통을 시작했다.이 전통은 힐리어드의 제자인 아이작 올리버(1565년경–1617년 10월 2일)에 의해 지속되었는데, 그의 프랑스 위그노 부모는 이 예술가의 어린 시절에 영국으로 도망쳤다.

이 기간 동안 주목할 만한 다른 영국 아티스트는 다음과 같습니다.나다니엘 베이컨 (1585년–1627년), 존 베츠 (1531년–1570년), 존 베츠 (1616년 사망), 조지 가워 (1540년–1596년 사망), 윌리엄 라킨 (1580년대–1619년), 로버트 피크 (1551년–[56]1619년 사망)18세기 초까지 튜더 궁정의 예술가들과 그 후계자들 중에는 영향력 있는 수입 인재들이 다수 포함되어 있었다.한스 홀바인, 앤서니 반 다이크, 피터 폴 루벤스, 오라지오 젠티엔스키와 그의 딸 아르테미시아, 피터 렐리 경 (1662년부터 귀화한 영어 과목), 그리고 고드프리 크넬러 경 (1691년 기사 [57]작위까지 귀화한 영어 과목)

17세기에는 실물 크기의 초상화를 그린 영국의 화가들이 많이 나타났는데, 특히 윌리엄 돕슨 (1611–bur. 1646년)이 눈에 띄었다; 다른 화가들로는 코넬리우스 존슨 (1593–bur. [58]1661년)과 로버트 워커 (1599–1658년)가 있다.새뮤얼 쿠퍼 (1609–1672)는 그의 형 알렉산더 쿠퍼 (1609–1660)와 그들의 삼촌 존 호스킨스 (1589/1590–1664)처럼 힐리어드의 전통에서 뛰어난 소형화가였다.이 시대의 다른 유명한 초상화는 다음과 같다.토마스 플랫먼 (1635–1688), 리처드 깁슨 (1615–1690), 방탕한 존 그린힐 (1644–1676년), 존 라일리 (1646–1691년), 존 마이클 라이트 (1617–1694년)가 있었다.프란시스 바로 (1626년경–1704년)는 "영국 스포츠 [59]회화의 아버지"로 알려져 있다; 그는 조지 스터브스 (1724–1806)[60]의 작품에서 한 세기 후에 절정에 이른 전통을 시작한 영국 최초의 야생동물 화가이다.영국 여성들은 17세기에 전문적으로 그림을 그리기 시작했다; 주목할 만한 예로는 조안 칼릴과 메리 빌이 있다.[61]

17세기 전반 영국 귀족들은 찰스 1세와 21대 아룬델 [62]백작 토마스 하워드에 의해 이끌려 유럽 미술의 중요한 수집가가 되었다.17세기 말까지, 고전적인 고대와 르네상스의 문화적 유산을 접하는 유럽 여행인 그랜드 투어는 부유한 젊은 [63]영국인들에게 매우 엄격했다.

16~17세기: 갤러리

18세기와 19세기

18세기에, 영어 그림의 뚜렷한 스타일과 전통 자주 초상화에 집중하지만, 풍경화 관심을 높여, 그리고 새로운 초점은 그 genres,[79]의 계층 구조위에 해당하는 것 그리고 제임스 손힐(1675/167의 놀라운 일에 잘 나타나 형국이다 역사 그림, 놓여져 있었고 계속했다.6–1734. 역사 화가 로버트 슈트레이터 (1621–1679)는 그의 [80]시대에 높이 평가되었다.

윌리엄 호가스 (1697–1764)는 출생뿐만 아니라 습관, 기질, 그리고 기질에 있어서도 증가하는 영국 중산층 기질을 반영했다.흑인 유머로 가득한 그의 풍자적인 작품들은 현대 사회에 런던 생활의 기형, 약점, 그리고 폐해를 지적한다.호가스의 영향은 제임스 길레이 (1756–1815)와 조지 크루익상크 (1792–1878)[81]에 의해 지속된 독특한 영어 풍자 전통에서 찾을 수 있다.호가스가 일했던 장르 중 하나는 대화 작품이었고, 그의 동시대 사람들 중 조셉 하이모어 (1692–1780), 프란시스 헤이먼 (1708–1776), 아서 데비스 (1712–1787)[82]도 뛰어난 형태였다.

초상화는 유럽에서와 마찬가지로 영국에서 예술가가 생계를 유지하는 가장 쉽고 수익성이 높은 방법이었고, 영국의 전통은 반 다이크가 추적할 수 있는 초상화 스타일의 여유로운 우아함을 계속해서 보여주었다.주요 인물화가는 다음과 같습니다.토마스 게인즈버러(1727년–1788년), 조슈아 레이놀즈(1723년–1792년), 조지 롬니(1734년–1802년), 레무엘 "프랜시스" 애보트(1760년–1802년), 리처드 웨스트올(1765년–1836년), 토머스 로렌스(1769년) 경또한 유명한 사람은 조나단 리처드슨(1667–1745)과 그의 제자(그리고 반항적인 사위)이다.토마스 허드슨(1701년-1779년).더비의 조셉 라이트 (1734–1797)는 촛불 그림으로 잘 알려져 있다; 조지 스터브스 (1724–1806) 그리고 후에 에드윈 헨리 랜드시어 (1802–1873)는 동물 그림으로 잘 알려져 있다.세기가 끝날 무렵, 영국의 거만한 초상화는 해외에서 [83]많은 찬사를 받았다.

런던의 윌리엄 블레이크(1757–1827)는 간단한 분류를 무시하고 다양하고 선견지명이 있는 작품을 만들었다. 비평가 조나단 존스는 그를 "영국 역사상 가장 위대한 예술가"[84]로 간주한다.블레이크의 예술가 친구들로는 블레이크가 싸운 신고전학자 존 플락스만 (1755–1826)과 토마스 스토타드 (1755–1834)가 있었다.

18세기 이후의 인기 있는 상상 속에서 영국 풍경화는 주로 목가적인 [85]전원 풍경을 배경으로 한 더 큰 시골 주택의 개발을 하면서 목가적인 사랑과 반향으로부터 영감을 받아 영국 예술을 대표한다.세계적으로 풍경화의 위상을 높이는 데는 크게 두 가지 영국 로맨틱이 있습니다.존 컨스터블 (1776–1837)과 J. M. W. 터너 (1775–1851)는 풍경화를 뛰어난 역사 [86][87]그림으로 끌어올린 공로를 인정받고 있다.다른 유명한 18세기와 19세기 풍경화가들은 다음과 같습니다.조지 Arnald(1763–1841);동물의 소박한 그림의 프랜시스 발로 전통 위에서 발전하는 영어 수채화 물감 그림의 아버지로 인식되곤 한다 존 Linnell(1792–1882)경쟁자 그의 시간에 Constable에, 조지 몰 런드(1763–1804), 새뮤얼 팔머(1805–1881), 폴 Sandby(1731–1809),와 후속[88]watercolourists 존 롭.ert 코젠스 (1752–1797), 터너의 친구 토마스 기틴 (1775–1802), 토마스 히피 (1775–1835)[89]가 있었다.

19세기 초에는 노리치 화가의 유파가 출현했는데, 이는 런던 외곽의 첫 번째 지방 예술 운동이었다.희박한 후원 및 내부 반대 때문에 단명했던 그 유명한 구성원들은 "창시자" 존 크롬 (1768–1821), 존 셀 코트만 (1782–1842), 제임스 스타크 (1794–1859), 그리고 조셉 스탠나드 (1797–1830)[90]였다.

라파엘 전파 운동은 1840년대에 설립되어 19세기 후반 영국 미술을 지배했다.윌리엄 홀먼 헌트 (1827–1910), 단테 가브리엘 로세티 (1828–1882), 존 에버렛 밀레 (1828–1896)와 다른 멤버들은 화려하고 세밀하며 거의 사진적인 [91]스타일로 그려진 종교, 문학, 장르 작품에 집중했다.포드 매독스 브라운 (1821–1893)은 라파엘 전파의 [92]원칙을 공유했다.

영국의 대표적인 미술 평론가 존 러스킨은 19세기 후반에 큰 영향을 끼쳤다; 1850년대부터 그는 자신의 [93]사상에 영향을 받은 라파엘 전파를 옹호했다.예술 공예 운동의 창시자인 윌리엄 모리스(1834–1896)는 대량 산업 시대에 쇠퇴한 것처럼 보이는 전통적인 공예 기술의 가치를 강조했다.라파엘 전파 화가의 작품과 같은 그의 디자인은 중세 [94]모티브를 자주 언급했다.영국의 서사 화가 윌리엄 파월 프리스 (1819–1909)는 "호가스 이후 가장 위대한 영국 사교계 화가"[95]로 묘사되었고 화가이자 조각가인 조지 프레데릭 와츠 (1817–1904)는 그의 상징주의 작품으로 유명해졌다.

19세기 영국 군사술의 용감한 정신은 빅토리아 시대의 영국의 자기 [96]이미지를 형성하는데 도움을 주었다.주목할 만한 영국의 군사 예술가들은: 존 에드워드 채프먼 '체스터' 매튜스 (1843–1927),[97] 레이디 버틀러 (1846–1933),[98] 프랭크 대드 (1851–1929), 에드워드 매튜 헤일 (1852–1924), 찰스 에드윈 프립 (1854–1906)[99]을 포함한다.리처드 캐튼 우드빌 주니어(1856년–[100]1927년), 해리 페인(1858년–[101]1927년), 조지 델빌 롤랜드슨(1861년–1930년), 에드거 알프레드 할로웨이(1870년–1941년)[102]역사적인 해군 [103]장면을 전문으로 했던 토마스 데이비슨 (1842년-1919년)은 영국의 프라이드와 영광 (1894년)[104]에 아날드, 웨스트올, 애보트의 넬슨 관련 작품들의 놀라운 복제품을 포함시켰다.

19세기 말까지, 오브리 비어슬리(1872–1898)의 예술은 아르누보의 발전에 기여했고,[105] 무엇보다도 일본의 시각 예술에 대한 관심을 시사했다.

18~19세기: 갤러리

호가스의 결혼 A-la-Mode: 2, 테테아테; 1743년 경.[108]

더비의 '공기 펌프의 새에 관한 실험'의 조셉 라이트; 1768년.[115]

길레이가 1805년 [122]위험에 빠졌어

1885년 [132]이후, 줄리아, 에버크롬비 부인의 고든 장군 초상화.

20세기

인상주의는 [135]1886년에 설립된 New English Art Club에서 주목받았다.주목할 만한 구성원으로는 20세기에 영향력을 갖게 된 동족적 삶을 가진 두 명의 영국 화가인 월터 시커트와 필립 윌슨 스티어가 있었다.시커트는 1911-1913년에 활동한 후기 인상파 캠든 타운 그룹에 갔고 모더니즘으로의 [136]이행에서 두드러졌다.스티어의 바다와 풍경화는 그를 최고의 인상주의자로 만들어주었지만, 이후 작품은 컨스터블과 [137]터너의 영향을 받은 보다 전통적인 영국 스타일을 보여준다.

폴 내쉬 (1889–1946)는 영국 미술에서 모더니즘의 발전에 중요한 역할을 했다.그는 20세기 전반의 가장 중요한 풍경화가 중 한 명이었고, 그가 제1차 세계대전 동안 그린 작품들은 [138]분쟁의 가장 상징적인 이미지들 중 하나이다.내쉬는 슬레이드 미술학교에 다녔고, 그곳에서 영향력 있는 헨리 톤스(1862년-1937년) 밑에서 공부한 주목할 만한 세대의 예술가들 역시 해롤드 길먼(1876년-1919년), 스펜서 고어(1878년-1914년), 데이비드 봄버그(1890년-1959년), 스탠리 스펜서(1891년-1959년-1891년), 마크러(1891년)를 포함했다.

모더니즘의 가장 논쟁적인 영국 재능은 작가이자 화가인 윈덤 루이스였다.그는 예술에서 보르티시스트 운동을 공동 창시했고, 1920년대와 1930년대 초 그의 그림보다 그의 글쓰기로 더 잘 알려진 후, 1930년대와 1940년대의 그림들이 그의 가장 잘 알려진 작품들 중 일부를 구성하면서, 시각 예술에 더 집중된 작품으로 돌아왔다.Walter Sickert는 Windham Lewis를 "지금이나 다른 어떤 시대의 가장 위대한 초상화 화가"[139]라고 불렀다.모더니즘 조각은 대리석 조각과 대규모 추상 주조 청동 조각으로 잘 알려진 영국 예술가 헨리 무어 (1898–1986)와 [140]2차 세계대전 당시 콘월 세인트 아이브스에 거주했던 예술가들의 식민지에서 선도적인 인물이었던 바바라 헵워스 (1903–1975)에 의해 대표되었다.

Lancastrian L. S. Lowry (1887년-1976년)는 20세기 중반 잉글랜드 북서부의 공업지대에서 생활하는 장면으로 유명해졌다.그는 독특한 화풍을 발전시켰고 종종 "성냥개비 인간"[141]으로 불리는 그의 도시 풍경화로 가장 잘 알려져 있다.

20세기 중반 이후의 주목할 만한 영국 예술가로는 그레이엄 서덜랜드(1903–1980), 카렐 웨이트(1908–1997), 러스킨 스피어(1911–1990), 팝아트 선구자 리처드 해밀턴(1922–2011), 피터 블레이크(1932), 데이비드 호크니(1937), 그리고 라일리 (1937) 등이 있다.

포스트모더니즘의 발달에 따라, 영국 예술은 20세기 말에 터너 상과 동의어가 되었다; 1984년에 제정되었고 표면적으로 신뢰할 수 있는 의도로 이름이 붙여진 이 상은 어제 영국 예술에 [142]대한 명성을 거의 손상시켰다.상품 전시품에는 포름알데히드 상어와 부스스한 [143]침대가 포함되어 있다.비평가 매튜 콜링스는 다음과 같이 말합니다. "터너상 예술은 처음에는 뭔가 놀라워 보였지만, 그 다음에는 분명 누군가가 당신에게 말해 줄 진부한 아이디어를 표현하는 공식을 기반으로 합니다.아이디어는 결코 중요하지 않고 심지어 광고의 개념처럼 더 많은 개념도 아닙니다.어차피 아무도 그들을 쫓지 않아요. 왜냐하면 추구할 게 없기 때문이죠."[144]

터너상 기득권은 듀샹과 만조니와 [145]같은 진정한 우상 숭배자들에 대한 약한 개념적 호메이지로 만족했지만, 베릴 쿡과 같은 독창적인 재능은 거절했습니다.[146]이 시상식은 2000년부터 매년 "Stuckists"의 시위를 끌어모으고 있는데, 이 단체는 조형 예술과 미적 진정성으로의 회귀를 촉구하는 단체이다."터너 상을 받을 위험이 없는 유일한 예술가는 터너"라는 비아냥을 들으며, 스터키스트들은 2000년에 "리얼 터너 상 2000" 전시회를 열었고,[147] "쓰레기는 없다"고 약속했다.

20세기: 갤러리

폴 내쉬의 "We are making a new world"; 1918년.[153]

L. S. Lowry's Going to Work 1959년

21세기

조각가 앤서니 곰리(b. 1950)는 터너상을 수상한 지 10년 만에 인류에 [161]대한 유용성에 대한 의구심을 드러냈고, 어나더 플레이스(2005년)와 이벤트 호라이즌(2012년) 등 작품도 호평을 받으며 인기를 끌고 있다.뱅크시의 [162]유사 파괴적인 도시 예술은 [163]언론에서 많이 논의되어 왔다.

2014년 짧은 기간 동안 볼 수 있었던 매우 눈에 띄고 많은 찬사를 받은 공공 예술 작품은 예술가 폴 커민스(1977년생)와 극장 디자이너 톰 파이퍼의 합작품인 Blood Sweep Lands and Seas of Red였다.2014년 7월부터 11월 사이에 런던 타워에 설치된 것은 제1차 세계 대전 발발 100주년을 기념하는 것이었다. 그것은 888,246개의 세라믹 레드 양귀비로 구성되었으며,[164] 각 양귀비는 전쟁에서 전사한 한 명의 영국 군인과 식민지 군인을 상징하기 위한 것이었다.

Norman Ackroyd와 Richard Spare가 현대 판화 업계를 선도하고 있습니다.

전시된 영국 미술품

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

추가 정보

- 데이비드 바인드먼(ed.), 영국 미술의 템즈 앤 허드슨 백과사전(런던, 1985)

- 조지프 버크, 잉글리시 아트, 1714-1800 (Oxford, 1976년)

- 윌리엄 건트, 영국 회화의 간결한 역사 (런던, 1978년)

- 윌리엄 건트, 영국 회화의 위대한 세기: 호가스에서 터너까지 (런던, 1971년)

- Nikolaus Pevsner, 영국미술의 영어성 (런던, 1956년)

- William Vaughan, 영국화: 호가스에서 터너까지의 황금시대(런던, 1999년)

- 엘리스 워터하우스, 1530-1790, 4번째 Edn, 1978, 펭귄북스(현재의 예일 미술사 시리즈)

레퍼런스

- ^ "Britain's first nude?". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Western Dark Ages And Medieval Christendom". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The story of the Reformation needs reforming". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm". Tate. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Manuscripts from the 8th to the 15th century". British Library. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Medieval And Renaissance Sculpture". Ashmolean Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Edge of darkness". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Nikolaus Pevsner: The Englishness of English Art: 1955". BBC Online. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "That was then..." The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Ackroyd's England". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Prehistory: Arts & Invention". English Heritage. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "World's oldest doodle found on rock". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Why these Bronze Age relics make me jump for joy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Celts: not quite the barbarians history would have us believe". The Observer. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Romans: Arts & Invention". English Heritage. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Jesus, the early years". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Big Brother's logo 'defiles' White Horse". The Observer. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Graffiti disfigured Ice Age cave art". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Stonehenge: not archaeology, but art". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Uffington White Horse (c.1000BC)". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Archaeologists and amateurs agree pact". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Sacred mysteries". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon treasure hoard casts Beowulf and wealthy warriors of Mercia in a new light". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Ivory Carvings in England from Before the Norman Conquest". BBC History. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Insular Art". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Everything is illuminated". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Benedictional of St Aethelwold". British Library. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon art from the 7th century to the Norman conquest". History Today. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Largest Anglo-Saxon hoard in history discovered". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Norman World of Art". History Today. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Campaign to bring the Bayeux Tapestry back to Britain". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Romanesque Art". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Matthew Paris: English artist and historian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "'Rarest' medieval panel painting saved by recycling". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Alabaster Collection". Nottingham Castle. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Object of the week: stained glass". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Savage warrior: Sutton Hoo Helmet". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Revealed: hidden art behind the gospel truth". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "St Chad Gospels". Lichfield Cathedral. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Towns and a tapestry". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Psalter returns to St Albans Cathedral". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Peterborough Psalter". Fitzwilliam Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "National Gallery unveils England's oldest altarpiece". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Creation of the World, in the 'Flowers of History'". British Library. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Detailed record for Royal 2 B VII". British Library. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Luttrell Psalter". British Library. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "'Virile, if Somewhat Irresponsible' Design: The Marginalia of the Gorleston Psalter". British Library. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Tickhill Psalter". University of Missouri. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A precious stone set in a silver sea: The Wilton Diptych: Andrew Graham-Dixon deciphers the royal message for so long concealed within medieval England's most famous painting". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Consecration of St Thomas Becket as archbishop". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Midlands glazier created this medieval masterpiece". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Simon (1979). British Art. London: The Tate Gallery & The Bodley Head. p. 12. ISBN 0370300343.

- ^ "Small is beautiful". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Gaunt, William (1978). A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 15–56.

- ^ "Paintings". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Cornelius Johnson: Charles I's Forgotten Painter". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ 영국 미술, Art UK의 작품 또는 그 이후의 작품들2016년 9월 8일 회수.

- ^ "Monkeys and Dogs Playing: Francis Barlow (1626–1704)". Art UK. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ Gaunt, William (1978). A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 29–56.

- ^ "Charles I art collection reunited for first time in 350 years as Royal Academy relocates works from Van Dyke and Titian". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "The Town & Country Grand Tour". Town and Country Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Would the real Anne Boleyn please come forward?". On the Tudor Trail. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Montrose, Louis (2006). The Subject of Elizabeth: Authority, Gender, and Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 123. ISBN 0226534758.

- ^ "Portraits of Queen Elizabeth The First, Part 2: Portraits 1573-1587". Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "'Young Man Among Roses' by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619)". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "A Young Man Seated Under a Tree, c. 1590-1595". Royal Collection. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Final Years of Elizabeth I's Reign". History Today. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The only true painting of Shakespeare - probably". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Wihl, Gary (1988). Literature and Ethics: Essays Presented to A. E. Malloch. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0773506624.

- ^ "William Dobson: Charles II, 1630 - 1685. King of Scots 1649 - 1685. King of England and Ireland 1660 - 1685 (When Prince of Wales, with a page)". Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "King Charles I at his Trial". National trust. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "John Evelyn". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles II (1630-1685) c.1676". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "John Locke". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Hodnett, Edward (1978). Francis Barlow: The First Master of English Book Illustration. London: Scolar Press. p. 106. ISBN 0859673502.

- ^ "Artist: John Riley, British, 1646-1691; Samuel Pepys". Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Painting history: Manet on a mission". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Sheldonian ceiling restored". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Hogarth, the father of the modern cartoon". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Newman, Gerald (1978). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837. London: Routledge. p. 525. ISBN 0815303963.

- ^ "A Short History of British Portraiture". Royal Society of Portrait Painters. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Blake's heaven". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Constable, Turner, Gainsborough and the Making of Landscape". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (11 October 2007). "The Sunshine Boy". Time. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

At the turn of the 18th century, history painting was the highest purpose art could serve, and Turner would attempt those heights all his life. But his real achievement would be to make landscape the equal of history painting.

- ^ "British Watercolours 1750-1900: The Landscape Genre". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Paul Sandby at Royal Academy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Landscape painting". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Made In England: Norfolk". BBC Online. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Pre-Raphaelite art: the paintings that obsessed the Victorians". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Into the Frame: the Four Loves of Ford Madox Brown by Angela Thirlwell: review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "John Ruskin's marriage: what really happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Who was William Morris? The textile designer and early socialist whose legacy is still felt today". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "William Powell Frith, 1819–1909". Tate. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Artist and Empire review – a captivating look at the colonial times we still live in". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman, 2 September 1898". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Tate Britain to explore - but not celebrate - art and the British Empire". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Battle of Isandlwana, 22 January 1879". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1854". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Harry Payne: Artist". Look and Learn. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Edgar Alfred Holloway - 1870-1941". Canadian Anglo-Boer War Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Nelson's Last Signal at Trafalgar". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "England's Pride and Glory". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Erotic bliss shared by all at Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "History of the Painted Hall". Old Royal Naval College. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Alexander Pope". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "General James Wolfe (1727-1759) as a Young Man". National Trust-Quebec House. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Mr and Mrs Andrews". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Great Works: The James Family (1751) by Arthur Devis". The Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Robert Clive and Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey, 1757". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Stubbs's equine masterpiece puts animal passion into the National". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Warren Hastings". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump". National Gallery. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Emma Hamilton and George Romney". Walker Art Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Horatio Nelson". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Europe: a Prophecy". British Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The Pilgrimage to Canterbury, 1806–7". Tate. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Plumb-pudding in danger - or - State Epicures taking un Petit Souper by Gillray". British Library. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Saluting the R-ts bomb uncovered on his birth day August 12th. 1816". British Museum. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Portrait of Duke of Wellington". Waterloo 200. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian Dress". British Library. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Fighting Temeraire". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Our English Coasts, 1852 ('Strayed Sheep') 1852". Tate. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Oil Painting - The Last of England". Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles Dickens". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "What to say about... John Ruskin". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles George Gordon". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "England's Pride and Glory". Art UK. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman, 1898". National Army Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "New English Art Club". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Walter Richard Sickert: British artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Philip Wilson Steer: British artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Archival Trail: Paul Nash the war artist". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Wyndham Lewis: a monster - and a master of portrait painting". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Why it's time you fell in love with Britain's battered post-war statues". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "LS Lowry at Tate Britain: glimpses of a world beyond". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Not all modern art is trivial buffoonery". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "He's our favourite artist. So why do the galleries hate him so much?". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Blake's progress". The Observer. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Art in 2015: forget the Turner prize - this was the year the Old Masters became sexy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Beryl Cook". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Stuck on the Turner Prize". Artnet. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Girls Running, Walberswick Pier; 1888–94". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Spencer GoreInez and Taki; 1910". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Harold Gilman: Leeds Market, c.1913". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Brighton Pierrots; 1915". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Mark Gertler: Merry-Go-Round, 1916". Tate. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "We are Making a New World". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Sappers at Work: Canadian Tunnelling Company, R14, St Eloi". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A Battery Shelled". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Patients waiting outside a first aid post in a factory". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Recruit's progress: medical inspection". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Shipbuilding on the Clyde: The Furnaces". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "'World's largest tapestry' at Coventry Cathedral repaired". BBC News. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Four-Square (Walk Through), 1966". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The legacy game: Gormley isn't the first artist to worry about his place in history". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Supposing ... Subversive genius Banksy is actually rubbish". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Britain's best-loved artwork is a Banksy. That's proof of our stupidity". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Blood-swept lands: the story behind the Tower of London poppies tribute". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

![Ochre horse illustration from the Creswell Crags; 11000-13000 BC.[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a4/Ochre_Horse.jpg/154px-Ochre_Horse.jpg)

![Stonehenge; 2600 BC.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/Stonehenge_Sunset_%281%29_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1626228.jpg/154px-Stonehenge_Sunset_%281%29_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1626228.jpg)

![Uffington White Horse; c. 1000 BC.[22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Aerial_view_from_Paramotor_of_Uffington_White_Horse_-_geograph.org.uk_-_305467.jpg/154px-Aerial_view_from_Paramotor_of_Uffington_White_Horse_-_geograph.org.uk_-_305467.jpg)

![Winchester Hoard items; 75-25 BC.[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Winchester_Hoard_items.jpg/154px-Winchester_Hoard_items.jpg)

![Hinton St Mary Mosaic; 4th century AD.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Hinton_St_Mary.jpg/154px-Hinton_St_Mary.jpg)

![Sutton Hoo helmet; c. 625.[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Sutton.hoo.helmet.jpg/102px-Sutton.hoo.helmet.jpg)

![Lindisfarne Gospels; c. 700.[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/03/Lindisfarne_Gospels_folio_209v.jpg/115px-Lindisfarne_Gospels_folio_209v.jpg)

![Lichfield Gospels; c. 730.[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/LichfieldGospelsEvangelist.jpg/118px-LichfieldGospelsEvangelist.jpg)

![Detail from the so-called Bayeux Tapestry; c. 1070s.[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/Bayeux_Deense_bijl.jpg/154px-Bayeux_Deense_bijl.jpg)

![Mary Magdalen announcing the Resurrection, from the St. Albans Psalter; 1120–1145.[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Wga_12c_illuminated_manuscripts_Mary_Magdalen_announcing_the_resurrection.jpg/121px-Wga_12c_illuminated_manuscripts_Mary_Magdalen_announcing_the_resurrection.jpg)

![The Fitzwilliam Peterborough Psalter; before 1222.[44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Peterborough_Psalter_c_1220-25_Mercy_and_Truth.jpg/150px-Peterborough_Psalter_c_1220-25_Mercy_and_Truth.jpg)

![The Westminster Retable; c. 1270s.[45]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/Westminster_Retable.jpg/138px-Westminster_Retable.jpg)

![King Arthur in Matthew Paris's Flores Historiarum; 1306–1326.[46]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/StepanAngl.jpg/154px-StepanAngl.jpg)

![The Queen Mary Psalter; 1310–1320.[47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Queen_Mary%27s_Psalter.jpg/96px-Queen_Mary%27s_Psalter.jpg)

![Becket's death in the Luttrell Psalter; 1320–1345.[48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/SmrtBecketta.jpg/154px-SmrtBecketta.jpg)

![Gorleston Psalter; 14th century.[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Gorleston3.jpg/93px-Gorleston3.jpg)

![Tickhill Psalter; 14th century.[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Tickhill.jpg/103px-Tickhill.jpg)

![The Wilton Diptych (right); c. 1395–1399.[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/The_Wilton_Diptych_%28Right%29.jpg/102px-The_Wilton_Diptych_%28Right%29.jpg)

![Nottingham Alabaster of St Thomas Becket; 15th century.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/StThomasEnthroned.jpg/154px-StThomasEnthroned.jpg)

![Stained glass at York Minster by John Thornton (fl. 1405–1433).[53]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Seven_Churches_of_Asia_in_the_East_Window_at_York_Minster.jpg/128px-Seven_Churches_of_Asia_in_the_East_Window_at_York_Minster.jpg)

![Hoskins's miniature of Anne Boleyn (c. 1501–1536); n.d.[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/AnneBoleyn56.jpg/153px-AnneBoleyn56.jpg)

![George Gower's sieve portrait of Elizabeth I; 1579.[65]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/George_Gower_Elizabeth_Sieve_Portrait_2.jpg/116px-George_Gower_Elizabeth_Sieve_Portrait_2.jpg)

![John Bettes the Younger's portrait of Elizabeth I; c. 1585.[66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Elizabeth_I_attrib_john_bettes_c1585_90.jpg/129px-Elizabeth_I_attrib_john_bettes_c1585_90.jpg)

![Nicholas Hilliard's Young Man Among Roses; 1587.[67]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Nicholas_Hilliard_-_Young_Man_Among_Roses_-_V%26A_P.163-1910.jpg/86px-Nicholas_Hilliard_-_Young_Man_Among_Roses_-_V%26A_P.163-1910.jpg)

![Isaac Oliver's A Young Man Seated Under a Tree; 1590–1595.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/Isaac_Oliver_d._%C3%84._002.jpg/112px-Isaac_Oliver_d._%C3%84._002.jpg)

![Detail of Robert Peake the Elder's procession portrait of Elizabeth I; c. 1601.[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Elizabeth_I._Procession_portrait_%28detail%29.jpg/106px-Elizabeth_I._Procession_portrait_%28detail%29.jpg)

![The Chandos portrait of Shakespeare, attributed to John Taylor; 1600–1610.[70]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3c/CHANDOS3.jpg/120px-CHANDOS3.jpg)

![William Larkin's portrait of Sir Francis Bacon; c. 1610.[71]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/William_Larkin_Sir_Francis_Bacon_2.jpg/123px-William_Larkin_Sir_Francis_Bacon_2.jpg)

![Dobson's portrait of Charles II when Prince of Wales; 1644.[72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Charles_II_when_Prince_of_Wales_by_William_Dobson%2C_1642.jpg/117px-Charles_II_when_Prince_of_Wales_by_William_Dobson%2C_1642.jpg)

![Edward Bower's King Charles I at his trial; 1648.[73]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Charles_I_at_his_trial.jpg/124px-Charles_I_at_his_trial.jpg)

![Robert Walker's portrait of diarist John Evelyn; 1648.[74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Walker%2C_Robert_John_-_Evelyn.jpg/112px-Walker%2C_Robert_John_-_Evelyn.jpg)

![John Michael Wright's portrait of Charles II; c. 1676.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Charles_II_by_John_Michael_Wright.jpg/130px-Charles_II_by_John_Michael_Wright.jpg)

![John Greenhill's portrait of John Locke; c. 1672–1676.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4b/John_Locke_by_Greenhill.jpg/129px-John_Locke_by_Greenhill.jpg)

![Francis Barlow's Coursing the Hare; 1686.[77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Coursing_the_Hare.JPG/107px-Coursing_the_Hare.JPG)

![John Riley's portrait of Samuel Pepys; c. 1690.[78]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/Samuel_Pepys_by_John_Riley_%28Yale_University_Art_Gallery%29.tif/lossy-page1-127px-Samuel_Pepys_by_John_Riley_%28Yale_University_Art_Gallery%29.tif.jpg)

![West wall of James Thornhill's Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College; 1707–1726.[106]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/45/The_west_wall_of_the_Painted_Hall_at_the_Old_Royal_Naval_College.jpg/154px-The_west_wall_of_the_Painted_Hall_at_the_Old_Royal_Naval_College.jpg)

![Richardson's portrait of Alexander Pope; c. 1736.[107]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e2/Alexander_Pope_circa_1736.jpeg/128px-Alexander_Pope_circa_1736.jpeg)

![Hogarth's Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête; c. 1743.[108]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Marriage_A-la-Mode_2%2C_The_T%C3%AAte_%C3%A0_T%C3%AAte_-_William_Hogarth.jpg/154px-Marriage_A-la-Mode_2%2C_The_T%C3%AAte_%C3%A0_T%C3%AAte_-_William_Hogarth.jpg)

![Highmore's portrait of General James Wolfe; 1749.[109]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Major-General_James_Wolfe.jpg/131px-Major-General_James_Wolfe.jpg)

![Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews; c. 1750.[110]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Thomas_Gainsborough-Andrews.jpg/154px-Thomas_Gainsborough-Andrews.jpg)

![Arthur Devis's "conversation piece" portrait of the East India Company's Robert James and family; 1751.[111]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/Arthur_Devis_13.jpg/154px-Arthur_Devis_13.jpg)

![Francis Hayman's Robert Clive and Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey; 1757.[112]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Clive.jpg/154px-Clive.jpg)

![George Stubbs's Whistlejacket; c. 1762.[113]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Whistlejacket_by_George_Stubbs_edit.jpg/128px-Whistlejacket_by_George_Stubbs_edit.jpg)

![Sir Joshua Reynolds's portrait of Warren Hastings; 1766–1768.[114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/Warren_Hastings_by_Joshua_Reynolds.jpg/122px-Warren_Hastings_by_Joshua_Reynolds.jpg)

![Joseph Wright of Derby's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump; 1768.[115]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Joseph_Wright_of_Derby_-_Experiment_with_the_Air_Pump_-_WGA25892.jpg/154px-Joseph_Wright_of_Derby_-_Experiment_with_the_Air_Pump_-_WGA25892.jpg)

![George Romney's Emma Hart in a Straw Hat; 1785.[116]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/George_Romney_-_Emma_Hart_in_a_Straw_Hat.jpg/128px-George_Romney_-_Emma_Hart_in_a_Straw_Hat.jpg)

![Lemuel Francis Abbott's portrait of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson; 1797.[117]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Vice-Admiral_Horatio_Nelson%2C_1758-1805%2C_1st_Viscount_Nelson.jpg/126px-Vice-Admiral_Horatio_Nelson%2C_1758-1805%2C_1st_Viscount_Nelson.jpg)

![William Blake's The Ancient of Days, frontispiece to Europe a Prophecy; 1794.[118]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Europe_a_Prophecy_copy_D_1794_British_Museum_object_1.jpg/113px-Europe_a_Prophecy_copy_D_1794_British_Museum_object_1.jpg)

![Thomas Heaphy's portrait of Palmerston; 1802.[119]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/03/Palmerston_1802.jpg/126px-Palmerston_1802.jpg)

![Richard Westall's Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797; 1806.[120]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Nelson_at_Cadiz.jpg/122px-Nelson_at_Cadiz.jpg)

![Gillray's The Plumb-pudding in danger; 1805.[122]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/James_Gillray_-_The_Plum-Pudding_in_Danger_-_WGA08993.jpg/154px-James_Gillray_-_The_Plum-Pudding_in_Danger_-_WGA08993.jpg)

![Cruikshank's Saluting the Regent's Bomb; 1816.[123]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Saluting_the_Regent%27s_Bomb.jpg/154px-Saluting_the_Regent%27s_Bomb.jpg)

![Lawrence's post-Waterloo portrait of Wellington; 1816.[124]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Sir_Arthur_Wellesley_Duke_of_Wellington.jpg/120px-Sir_Arthur_Wellesley_Duke_of_Wellington.jpg)

![George Arnald's The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798; 1825–27.[125]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/The_Battle_of_the_Nile.jpg/154px-The_Battle_of_the_Nile.jpg)

![Phillips's portrait of Lord Byron; c. 1835.[126]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/Lord_Byron_in_Albanian_dress.jpg/128px-Lord_Byron_in_Albanian_dress.jpg)

![Turner's The Fighting Temeraire; 1839.[127]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Turner_temeraire.jpg/154px-Turner_temeraire.jpg)

![Holman Hunt's Our English Coasts; 1852.[128]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Hunt_english_coasts.jpg/154px-Hunt_english_coasts.jpg)

![Ford Madox Brown's The Last of England; 1852–1855.[129]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Ford_Madox_Brown%2C_The_last_of_England.jpg/138px-Ford_Madox_Brown%2C_The_last_of_England.jpg)

![William Powell Frith's portrait of Dickens; 1859.[130]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/Charles_Dickens_by_Frith_1859.jpg/123px-Charles_Dickens_by_Frith_1859.jpg)

![John Ruskin, leading English art critic of the Victorian era; 1867.[131]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/John_Ruskin_CDV_by_Elliott_%26_Fry%2C_1867.jpg/100px-John_Ruskin_CDV_by_Elliott_%26_Fry%2C_1867.jpg)

![Julia, Lady Abercromby's portrait of General Gordon; after 1885.[132]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e8/Charles_George_Gordon_by_Julia_Abercromby.jpg/126px-Charles_George_Gordon_by_Julia_Abercromby.jpg)

![Thomas Davidson's England's Pride and Glory; 1894.[133]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/England%27s_Pride_and_Glory.jpg/119px-England%27s_Pride_and_Glory.jpg)

![Woodville's The Charge of the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman, 2 September 1898; 1898.[134]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/RCWoodvilleJr_21Lancers_Omdurman.jpg/154px-RCWoodvilleJr_21Lancers_Omdurman.jpg)

![Philip Wilson Steer's Girls Running, Walberswick Pier; 1888–94.[148]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/GirlsRunning_Steer.jpg/154px-GirlsRunning_Steer.jpg)

![Spencer Gore's Balcony at the Alhambra; 1910–11.[149]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Spencer_Gore_Balcony_at_the_Alhambra_1910-11.jpg/112px-Spencer_Gore_Balcony_at_the_Alhambra_1910-11.jpg)

![Harold Gilman's Leeds market; c. 1913.[150]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/Gilman_leeds_market.jpg/154px-Gilman_leeds_market.jpg)

![Walter Sickert's Brighton Pierrots; 1915.[151]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/BrightonPierrotsWalterSickert.jpg/154px-BrightonPierrotsWalterSickert.jpg)

![Mark Gertler's Merry-Go-Round; 1916.[152]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Mark_Gertler_-_Merry-Go-Round_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/117px-Mark_Gertler_-_Merry-Go-Round_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

![Paul Nash's We are Making a New World; 1918.[153]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/We_are_Making_a_New_World_Art.IWMART1146.jpg/154px-We_are_Making_a_New_World_Art.IWMART1146.jpg)

![David Bomberg's Sappers at Work: Canadian Tunnelling Company, R14, St Eloi; 1918.[154]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Sappers_at_work_-_Canadian_Tunnelling_Company%2C_R14%2C_St_Eloi_Art.IWMART2708.jpg/125px-Sappers_at_work_-_Canadian_Tunnelling_Company%2C_R14%2C_St_Eloi_Art.IWMART2708.jpg)

![Wyndham Lewis's A Battery Shelled; 1919.[155]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/A_Battery_Shelled_Art.IWMART2747.jpg/154px-A_Battery_Shelled_Art.IWMART2747.jpg)

![Ruskin Spear's Patients waiting Outside a First Aid Post in a Factory; 1942.[156]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/Patients_waiting_Outside_a_First_Aid_Post_in_a_Factory_Art.IWMARTLD2683.jpg/154px-Patients_waiting_Outside_a_First_Aid_Post_in_a_Factory_Art.IWMARTLD2683.jpg)

![Carel Weight's Recruit's Progress; 1942.[157]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Recruit%27s_Progress-_Medical_Inspection_Art.IWMARTLD2909.jpg/154px-Recruit%27s_Progress-_Medical_Inspection_Art.IWMARTLD2909.jpg)

![Stanley Spencer's Shipbuilding on the Clyde: The Furnaces; 1946.[158]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/Shipbuilding_on_the_Clyde%2C_The_Furnaces_%28Art.IWM_ART_LD_5871%29.jpg/111px-Shipbuilding_on_the_Clyde%2C_The_Furnaces_%28Art.IWM_ART_LD_5871%29.jpg)

![Graham Sutherland's Christ tapestry in the rebuilt Coventry Cathedral; 1962.[159]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Coventry_Cathedral_interior_-_geograph.org.uk_-_291162.jpg/115px-Coventry_Cathedral_interior_-_geograph.org.uk_-_291162.jpg)

![Barbara Hepworth's Four-Square (Walk Through); 1966.[160]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Barbara_Hepworth_Geograph-685325-by-Fractal-Angel.jpg/102px-Barbara_Hepworth_Geograph-685325-by-Fractal-Angel.jpg)