월트 디즈니 컴퍼니

The Walt Disney Company디즈니 로고의 기업형 변형 | |

| |

| 디즈니 | |

| 이전에 |

|

| 유형 | 일반의 |

| 아이신 | US2546871060 |

| 산업 | |

| 전임자 | Laugh-O-Gram 스튜디오 |

| 설립. | 1923년 10월 16일, 전( |

| 설립자 | |

| 본사 | 디즈니 빌딩 팀, 월트 디즈니 스튜디오, 미국 |

서비스 지역 | 전 세계 |

주요 인물 | 수잔 아놀드 (회장) 밥 아이거 (최고경영자) |

| 상품들 | |

| 서비스 | |

| 수익. | |

| 총자산 | |

| 총자본 | |

종업원수 | 195,000 (2022) |

| 디비전 |

|

| 자회사 | |

| 웹 사이트 | thewaltdisneycompany |

| 각주/참고 자료 [1][2][3] | |

월트 디즈니 컴퍼니(Walt Disney Company)[4]는 미국 캘리포니아주 버뱅크의 월트 디즈니 스튜디오 단지에 본사를 둔 다국적 대중 매체 및 엔터테인먼트 기업이다.디즈니는 원래 1923년 10월 16일 월트와 로이 O. 디즈니 형제에 의해 디즈니 브라더스 스튜디오로 설립되었고, 1986년 월트 디즈니 컴퍼니로 이름을 변경하기 전에 월트 디즈니 스튜디오와 월트 디즈니 프로덕션이라는 이름으로 운영되었다.동사는 초기에, 동사의 마스코트인 인기 캐릭터 미키 마우스의 탄생과 애니메이션 영화의 시작으로 애니메이션 업계의 리더로서 자리매김했다.

1940년대 초까지 큰 성공을 거둔 후, 1950년대에 이 회사는 실사 영화, 텔레비전, 그리고 테마 파크로 다각화하기 시작했습니다.1966년 월트의 사망 이후, 특히 애니메이션 부문에서 회사의 수익은 감소하기 시작했다.1984년 디즈니의 주주들이 마이클 아이스너를 사장으로 선출하자, 스튜디오는 디즈니 르네상스라고 불리는 시기에 압도적인 성공을 거두기 시작했다.2005년, 밥 아이거 신임 CEO의 지휘하에, 동사는 다른 법인의 확장과 인수에 착수했습니다.밥 차펙은 아이거의 은퇴 후 2020년에 디즈니의 사장이 되었다.아이거는 2022년 차펙이 축출된 후 CEO로 복귀하게 된다.

1980년대부터 디즈니는 자사의 주력 패밀리 지향 브랜드보다 더 성숙한 콘텐츠를 마케팅하기 위해 기업 부서를 만들고 인수했습니다.이 회사는 월트 디즈니 픽처스, 월트 디즈니 애니메이션 스튜디오, 픽사, 마블 스튜디오, 루카스 필름, 20세기 스튜디오, 20세기 애니메이션, 서치라이트 픽처스를 포함한 영화 스튜디오 사업부로 알려져 있다.디즈니의 다른 주요 사업 부문에는 텔레비전, 방송, 스트리밍 미디어, 테마 파크 리조트, 소비자 제품, 출판 및 국제 운영 부문이 포함됩니다.이러한 다양한 세그먼트를 통해 디즈니는 ABC 방송 네트워크, Disney Channel, ESPN, Freeform, FX, National Geographic 등의 케이블 TV 네트워크, 출판, 판매, 음악 및 극장 부문, Disney+, Star+, ESPN+, Hulu, Hot Starie, Disney Experience 등의 소비자 직접 스트리밍 서비스를 소유하고 운영하고 있습니다.nces and Products. 전 세계 여러 테마파크, 리조트 호텔 및 크루즈 라인이 포함되어 있습니다.

디즈니는 세계에서 가장 크고 가장 잘 알려진 기업 중 하나이며, 2022년 포춘 500대 미국 기업 목록에서 53위에 올랐다.설립 이래, 이 회사는 총 135개의 아카데미 상을 수상했으며, 26개는 월트에게 수여되었다.이 회사는 또한 테마파크 산업에 혁명을 일으킬 뿐만 아니라 역대 최고의 영화들을 제작했다고 알려져 왔다.디즈니는 과거 인종차별적 고정관념을 묘사하고 영화에 LGBT 관련 요소를 포함하거나 포함하지 않는 표절 의혹으로 비난을 받아왔다.1940년부터 상장된 이 회사는 뉴욕증권거래소(NYSE)에서 거래되며 1991년부터 다우존스 산업평균지수의 구성 요소가 되었다.2020년 8월 주식의 3분의 2가 조금 안 되는 대형 금융기관이 보유했다.

역사

1923~1934: 창립, 미키마우스, 그리고 바보같은 교향곡

월트 디즈니와 그의 친구이자 애니메이터인 Ub [5]Iwerks가 설립한 캔자스시티의 영화 스튜디오인 Laugh-O-Gram Studio에서 월트는 앨리스의 이상한 나라라는 제목의 단편 영화를 만들었다.그것은 아역 여배우 버지니아 데이비스가 애니메이션 캐릭터들과 교류하는 것을 특징으로 했다.쇼트가 만들어진 직후인 1923년, Lauget-O-Gram Studio는 파산했지만, 후에 이 쇼트는 뉴욕 영화 배급사 Margaret J. Winkler가 그것을 사들임으로써 히트를 쳤다.월트는 6개의 앨리스 코미디 시리즈를 제작하는 계약을 맺었고,[6][7] 각각 6개의 에피소드로 구성된 2개의 시리즈를 추가로 제작할 수 있는 옵션을 갖췄다.계약 전에 [8]월트는 로이가 결핵에 걸렸기 때문에 그의 동생 로이 O. 디즈니와 합류하기 위해 할리우드로 가기로 결정했다.이로써 그들은 이 [9]영화들을 제작하기 위해 회사의 공식 시작인 10월 16일에 디즈니 브라더스 스튜디오를 공동 설립할 수 있었다.월트는 나중에 Iwerks와 Davis의 가족들도 [7]할리우드로 옮기도록 설득했다.1926년 1월, 하이페리온 거리에 디즈니 스튜디오가 완공되었고 디즈니 브라더스 스튜디오의 이름은 월트 디즈니 [10]스튜디오로 바뀌었다.이후 4년 동안 여러 편의 앨리스 영화를 제작한 후, 윙클러는 그녀의 남편인 찰스 민츠에게 영화를 배급하는 역할을 넘겨주었다.1927년, 민츠는 유니버설 픽처스의 새로운 시리즈 영화를 제작해 달라고 요청했다.이에 대응하여 월트는 오스왈드 더 럭키 [11]래빗이라는 캐릭터를 주인공으로 한 그의 첫 번째 완전 애니메이션 영화 시리즈를 만들었다.월트 디즈니 스튜디오는 오스왈드가 [12]나오는 26편의 영화를 만들 것이다.

1928년, 월트는 그의 영화에 더 많은 출연료를 원했지만 민츠는 가격을 낮추기를 원했다.월트가 유니버셜이 오스왈드에 대한 지적 재산권을 소유하고 있다는 것을 알게 된 직후, 민츠는 그가 [12][13]감액된 금액을 받지 않으면 그 없이 영화를 제작하겠다고 위협했다.월츠는 이를 거절했고 민츠는 월트 디즈니 스튜디오의 주요 애니메이션 제작자 4명과 계약을 맺고 자신의 스튜디오를 시작했다.Iwerks는 [14]Studio에 남을 수 있는 유일한 최고의 애니메이션 제작자가 될 것이다.오스왈드를 잃었기 때문에 월트와 아이웍스는 그를 원래 모티머 마우스라는 생쥐로 대체했다.이 캐릭터의 이름은 월트의 아내가 현재 회사의 마스코트인 [15][16]미키 마우스로 바꾸라고 종용한 후 바뀔 것이다.지난 5월, 이 영화사는 이 캐릭터를 테스트 상영작으로 두 편의 무성 영화인 Plane Crazy와 The Gallopin' Gaucho를 제작했다.그 후, 스튜디오는 첫 번째 사운드 필름과 세 번째 단편 미키 시리즈의 증기선 윌리 시리즈를 제작했다.싱크로나이즈드 사운드로 제작되어 최초의 포스트 제작 사운드 [17]만화를 만들었습니다.팻 파워스의 배급 회사가 이 영화를 배급할 것이고 증기선 윌리는 애니메이션 [15][18][19]산업에서 회사를 지배할 수 있는 길을 이끌면서 즉각적인 히트를 쳤다.이 소리는 리 드 포레스트의 포노필름 [20]시스템을 사용한 파워스의 시네폰 시스템을 사용하여 만들어졌다.그 회사는 1929년에 [21][22]동기 음향을 가진 두 개의 초기 영화를 성공적으로 재출시했다.

뉴욕의 콜로니 극장에서 증기선 윌리가 개봉된 후, 미키 마우스는 엄청나게 인기 있는 [22][15]캐릭터가 되었다.디즈니는 계속해서 그와 다른 [23]캐릭터들이 등장하는 여러 개의 만화를 만들곤 했다.월트와 로이가 [19]파워스와 함께 수익을 나누지 못하고 있다고 느꼈기 때문에 디즈니는 8월에 콜롬비아 픽처스와 함께 실리 심포니 시리즈를 시작했다.파워스는 나중에 자신의 스튜디오를 [24]차릴 아이웍스를 해고할 것이다.칼 스탈링은 시리즈를 시작하고 시리즈의 초기 영화들을 위한 음악을 작곡하는데 중추적인 역할을 했지만, 아이웍스가 [25][26]한 후에 회사를 떠났다고 한다.지난 9월, 극장 매니저 해리 우딘은 관객 수를 늘리기 위해 자신의 극장인 폭스 돔에서 미키 마우스 클럽을 설립할 수 있도록 허가를 요청했다.월트는 동의했지만 데이비드 E.다우씨는 우딘이 그의 클럽을 시작하기 전에 엘시노어 극장에서 처음으로 클럽을 시작했다.왜 우딘이 첫 번째 클럽을 만들지 않았는지는 알려지지 않았지만, 12월 21일 엘시노어에서 열린 클럽을 위한 첫 번째 모임에는 약 1,200명의 아이들이 참석했다.미키마우스 클럽은 결국 전국 800개 이상의 극장에 걸쳐 100만 명의 아이들이 [27][28]회원으로 가입했다.7월 24일, 킹 피처스 신디케이트의 사장 조셉 콘리는 디즈니 스튜디오에 미키 마우스 만화를 만들어 달라고 메일을 보냈다.그들은 11월에 시작하였고 승인 [29]받은 스트립 샘플을 그들에게 보냈다.12월 16일, 월트 디즈니 스튜디오의 제휴는, 「월트 디즈니 프로덕션즈, 유한 회사」라는 이름으로, 상업 부문인 「월트 디즈니 엔터프라이즈」와 부동산의 자회사인 「디즈니 필름 레코딩 컴퍼니」와 「릴드 부동산·인베스트먼트 컴퍼니」의 2개의 자회사로 재편성되었습니다.월트 부부는 이 회사의 지분 60%(6,000주), 로이는 40%를 갖고 있었다.[30]

연재만화 미키 마우스는 1930년 1월 13일 뉴욕 데일리 미러에 첫 선을 보였고 1931년까지 연재만화는 다른 20개국의 [31]신문뿐만 아니라 미국의 60개 신문에 실렸다.캐릭터들을 위한 상품들을 가지고 나오는 것이 회사에 더 많은 수익을 가져다 줄 것이라는 것을 알게 된 후, 월트는 뉴욕의 한 호텔에서 그가 300달러에 제조하고 있던 몇몇 필기용 태블릿에 미키 마우스를 넣을 수 있는 라이센스를 그에게 요구한 한 남자를 만났다.월트는 이에 동의했고 미키는 디즈니 머천다이징의 [32][33]시작과 함께 역사상 최초의 라이선스 캐릭터가 되었다.1933년 월트는 캔자스시티 광고회사 케이 케이멘을 소유한 남자에게 디즈니의 상품을 운영해 달라고 부탁했다.그는 동의했고 디즈니의 상품화를 완전히 바꿀 것으로 고려되었다.1년 만에 Kamen은 40개의 미키 라이선스를 획득했고 2년 만에 3천 5백만 달러의 매출을 올렸다.1934년 월트는 미키 [34][35]영화보다 미키의 상품으로 더 많은 돈을 벌었다고 주장했다.후에, 디즈니의 상품화 추진의 일환으로, 워터베리 시계 회사는 미키 마우스 시계를 만들었다.그것은 매우 유명해져서 대공황 기간 동안 워터베리를 파산으로부터 구했다.메이시스에서의 판촉 행사에서는 미키마우스 시계가 하루 만에 11,000개 팔렸고 2년 만에 250만 개가 팔렸다.[36][31][35]미키가 장난꾸러기 생쥐 대신 영웅적인 타입이 되기 시작하면서 디즈니는 개그를 [37]만들 수 있는 또 다른 캐릭터가 필요했다.월트가 라디오를 듣고 있을 때, 클라렌스 내쉬의 목소리를 듣고 그를 스튜디오로 초대했다.그의 목소리를 다시 들은 후, 월트는 스튜디오의 새로운 개그 캐릭터가 될 도널드 덕이라는 이름의 말하는 오리를 위해 그것을 사용하고 싶어했다.도날드는 1934년 지혜로운 작은 암탉에 처음 등장했다.미키만큼 빨리 인기를 끌지는 못했지만, 그는 도날드와 명왕성(1936년)에서 자신만의 주역을 맡았고 결국 자신만의 [38]시리즈를 갖게 되었다.

콜롬비아 영화사와의 실리 심포니와의 불화 이후 월트는 1932년부터 1937년까지 이 시리즈를 [39]배급하기 위해 유나이티드 아티스트와 배급 계약을 맺었다.1932년 디즈니는 1935년 말까지 테크니컬러와 컬러 만화를 제작하는 독점 계약을 맺었는데, 이는 실리 [40]심포니의 일부였던 꽃과 나무(1932년)를 시작으로 한다.이 영화는 사상 최초의 풀컬러 만화였고 [17]그해 말 아카데미 만화상을 수상했다.1933년, "어린 돼지 세 마리"는 또 다른 인기 있는 "실리 심포니"가 되었고 아카데미 [23][41]만화상을 수상하기도 했다.다른 실리 심포니 곡들도 작곡한 프랭크 처칠이 작곡한 영화 "Who's Fair of the Big Bad Wolf?"의 노래는 1930년대 내내 인기를 끌었고 가장 잘 알려진 디즈니 [25]노래 중 하나로 남아 있다.실리 심포니의 영화들은 또 다른 디즈니 영화인 페르디난드 더 황소가 [23]수상한 1938년을 제외하고 1931년부터 1939년까지 최우수 만화상을 수상했습니다.

1934~1949: 애니메이션, 파업, 제2차 세계 대전의 황금기

1934년, 월트는 디즈니의 첫 장편 애니메이션 영화인 백설공주와 일곱 난쟁이를 만들기로 결심했고, 그의 애니메이션 제작자들에게 그 이야기를 연기함으로써 말했다.로이는 월트가 스튜디오를 파산시킬 것이라며 제작하는 것을 막으려고 노력했고 할리우드는 이를 "디즈니의 어리석음"이라고 불렀지만 월트는 이 [42][43]영화를 계속 제작했다.월트는 영화에 대한 현실적인 접근을 하기로 결심하고 영화의 장면을 마치 [44]실사처럼 만들어냈다.영화를 만드는 과정에서, 그들은 배경에 [45]깊이의 착각을 일으키기 위해 다른 거리에 그림이 그려진 유리 조각인 멀티판 카메라를 만들었다.United Artist가 디즈니 쇼츠에 대한 미래의 텔레비전 판권을 획득하려고 시도한 후,[46] Walt는 1936년 3월 2일 RKO Radio Pictures와 배급 계약을 맺었다.그들은 백설공주 예산의 10배인 150만 [42]달러를 초과했다.

1937년 12월 12일 첫 선을 보이면서 제작하는데 3년이 걸렸다.이 영화는 2021년 1억 5천 79만 6천 296달러에 해당하는 8백만 달러를 벌어들이며 그 시점까지 역대 최고 수익을 올린 영화가 되었다; 몇 번의 재상영 후,[47][48] 이 영화는 인플레이션을 감안하여 미국에서 총 9억 9천 8백 44만 달러의 수익을 올릴 것이다.백설공주와 일곱 난장이의 수익 이후 디즈니는 캘리포니아 버뱅크에 51에이커(20.6ha) 규모의 새로운 스튜디오 단지를 건설하는 데 자금을 지원했고,[49][50] 1940년에 완전히 입주했다.같은 해 4월 2일 디즈니는 월트와 그의 가족과 함께 보통주를 보유하면서 첫 주식 공개를 했다.월트는 상장하기를 원하지 않았지만,[51] 회사는 돈이 필요했다.백설공주와 일곱 난장이의 개봉 직전에, 그들의 차기작 피노키오와 밤비 작업이 시작되었고, 밤비는 [46]연기되었다.비록 피노키오는 [52]애니메이션에서 획기적인 업적을 남겼다는 평과 함께 아카데미 최우수 노래상과 최우수 악보상을 수상할 것이지만, [53][54]2차 세계대전으로 인해 해외 개봉이 중단되었기 때문에 1940년 2월 23일 개봉 당시 박스오피스에서 부진한 성적을 거두게 될 것이다.

디즈니의 차기작 판타지아 또한 흥행 폭탄이었지만, 영화의 사운드트랙을 제작하기 위해 초기 개발 서라운드 사운드인 판타사운드를 만들어냄으로써 큰 성과를 거두었고,[55][56][57] 스테레오로 상영된 최초의 상업 영화가 되었다.1941년, 디즈니는 800명의 애니메이션 제작자 중 300명이 주로 회사의 최고 애니메이션 제작자 중 한 명인 아트 배빗이 이끄는 가운데 일부는 받는 임금 때문에 노조 결성을 위해 5주 동안 파업을 할 때 큰 차질을 빚었다.월트는 파업 중인 사람들이 비밀리에 공산주의자들이고, 결국 몇몇 최고의 [58][59]애니메이터들을 포함한 스튜디오의 많은 애니메이터들을 해고하게 될 것이라고 생각했다.로이는 이 회사의 주요 배급사들이 영화사에 투자하게 하려고 노력했고, 스튜디오를 위해 더 많은 제작비를 확보하려고 노력했지만,[60] 더 이상 직원 해고로 제작비는 더 이상 직원 해고로 상쇄될 수 없었다.로버트 벤틀리가 디즈니 스튜디오를 순회하는 디즈니의 네 번째 영화인 '마지못한 드래곤'의 시사회 동안 파업 시위대가 나타났다. 이 영화는 [61]제작비보다 10만 달러나 떨어질 것이다.

파업을 위한 협상이 진행되는 동안, 월트는 결과가 자신에게 [62]유리하지 않을 것을 알았기 때문에 협상 기간 동안 월트가 떠나도록 확실히 하기 위해 몇몇 애니메이터들과 함께 남미로 친선 여행을 하자는 미주 조정관실의 제안을 받아들였다.그곳에서 12주 동안 그들은 영화를 위한 음모를 꾸미기 시작했고 음악에 [63]영감을 받았다.파업의 결과로, 스튜디오는 연방 중재자들의 강요로 스크린 카툰가 길드를 인정했고 몇몇 애니메이션 제작자들을 잃었고 회사는 694명의 [64][59]직원만 남게 되었다.그들의 재정적 손실을 만회하기 위해 디즈니는 더 적은 예산으로 서둘러 다섯 번째 애니메이션 영화인 덤보를 제작할 것이다.덤보는 박스오피스에서 성공을 거두었고 [52][65]이 회사에 매우 필요한 재정적 이득이 될 것이다.진주만 폭격 후, 많은 애니메이션 제작자들이 [66]군대에 징집될 것이다.이후 미 육군 소속 500명의 병사들이 인근 록히드 항공기 공장을 보호하기 위해 8개월 동안 스튜디오를 점령하기 시작했다.그들이 그곳에 있는 동안, 그들은 장비를 큰 방음대에 고정하고 창고를 [67]탄약고로 개조했다.12월 8일, 해군은 월트에게 전쟁에 대한 지지를 얻기 위해 선전 영화를 제작해 줄 것을 요청했다.그는 9만 [68]달러에 20개의 전쟁 관련 반바지를 제작하기로 그들과 합의하고 계약을 맺었다.이 회사의 직원들 대부분은 이 프로젝트에 착수하여 Victory Through Air Power와 같은 영화를 만들었고 몇몇 [69][66]영화에 회사의 캐릭터들을 포함시켰다.

1942년 8월, 밤비는 마침내 디즈니의 여섯 번째 애니메이션 영화로 개봉되었고 박스 [70]오피스에서 좋은 성적을 거두지 못했다.1943년 디즈니는 남미를 방문한 후 살루도스 아미고스와 세 명의 카발레로스를 만들었지만,[66][71] 그들은 개봉을 잘 하지 못했다.이 두 영화는 "패키지 영화"로, 몇 개의 단편 만화들이 모여 장편 영화를 만들었는데, 디즈니는 이를 통해 Make Mine Music (1946), Fun and Fancy Free (1947), Melody Time (1948), 그리고 The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949)와 같은 영화를 제작할 것이다.[66]제작비가 적게 들면서, 스튜디오는 나중에 디즈니의 가장 논란이 많은 [72][73]영화가 될 Song of South를 시작으로 애니메이션이 혼합된 실사 영화 제작을 시작했다.회사가 돈이 부족했기 때문에, 1944년에 그들은 그들의 장편 영화를 다시 개봉할 계획을 세웠고, 이것은 매우 [73][74]필요한 수익을 창출할 것이다.1948년 디즈니는 자연 다큐멘터리 시리즈인 트루라이프 어드벤처스를 시작했는데, 이 시리즈는 1960년까지 상영되어 8개의 아카데미 [75][76]상을 수상하게 된다.1949년 애니메이션 영화 신데렐라 제작이 진행되던 중, 월트 디즈니 뮤직 컴퍼니는 신데렐라의 음악이 히트하기를 [77]바랐던 상품 판매 수익에 도움을 주기 위해 설립되었습니다.

1950~1967: 실사 영화, 텔레비전, 디즈니랜드, 월트 디즈니의 죽음

1950년, 디즈니의 8년 만의 애니메이션 영화 신데렐라가 개봉되었고 디즈니의 모습으로 돌아가는 것으로 여겨졌다.이는 백설공주 이후 디즈니의 최고의 흥행 성공작이 될 것이며, 박스 오피스 첫 해에 총 8백만 달러를 벌어들였고 220만 달러를 벌어들였다.월트는 기차에 정신이 팔려 디즈니 최초의 완전한 실사 영화 '보물섬'[78]을 만들기 위해 영국으로 여행을 떠났기 때문에 이전 영화들처럼 관여하지 않았다.그것이 성공적이었기 때문에, 그는 로빈 후드와 그의 즐거운 [79]사람들의 이야기를 제작하기 위해 영국으로 돌아갔다.1950년, 텔레비전 산업은 성장하기 시작했고, NBC가 디즈니사의 다음 애니메이션 영화 이상한 나라의 앨리스의 홍보 프로그램이자 코카콜라가 [80]후원하는 회사의 첫 텔레비전 제작물인 이상한 나라의 한 시간 동안을 방영했을 때 디즈니는 이에 동참했다.영국 여행 중 이상한 나라의 앨리스가 풀려나 제작 [81]예산보다 100만 달러가 모자라 회사에 실망을 안겨주었다.돌아온 월트는 그가 짓고 싶은 미키 마우스 파크라고 불리는 놀이공원에 대해 생각하기 시작했다. 미키 마우스 파크라는 스튜디오 근처에 증기선 타기 같은 볼거리가 있는 8에이커의 땅이지만, 사업은 계속 방해되었고 세 번째 영국 영화 "검과 장미"의 제작이 시작되었다.[82]월트는 그것을 감독할 뿐이지만, 그것은 월트 디즈니 브리티시 필름스 [83]리미티드라고 불리는 디즈니의 새로운 자회사에서 자금을 조달할 것이다.

월트는 그의 딸들과 그리피스 공원을 방문했을 때 놀이공원에 대한 아이디어를 처음 생각해냈다고 회상했다.그는 그들이 회전목마를 타는 것을 봤다고 말했고 "그게 있어야 한다고..." 생각했다고 말했다.부모와 자녀가 함께 [84][85]즐길 수 있는 놀이시설 같은 것"이라고 말했다.월트는 미키마우스파크를 계속 생각하면서 이름을 디즈니랜드로 바꾸기 전에 디즈니랜드로 [82]바꿨다.로이가 공원에 대해 의심했기 때문에 월트는 1952년 12월 16일 월트 디즈니 엔터프라이즈라고 불리는 새로운 개인 소유 회사를 설립하여 공원을 후원할 것이다.얼마 지나지 않아 1953년 [86]11월 WED 엔터프라이즈(현[a] 월트 디즈니 이매진링)로 이름을 변경하기 전에 월트 디즈니 주식회사로 이름을 바꾸게 된다.그는 계획을 세우기 위해 디자이너 그룹을 고용했고 이 계획을 세웠던 사람들은 "상상인"[87]으로 불리게 되었다.월트가 공원의 아이디어를 생각해 낸 이후, 그와 그의 친구들은 [88]어떻게 공원을 지을지에 대한 아이디어를 얻기 위해 미국과 유럽의 공원을 방문하곤 했다.스튜디오 근처의 버뱅크에 공원을 짓겠다는 그의 계획은 8에이커의 땅이 충분하지 않을 것이라는 것을 깨달았을 때 빠르게 바뀌었다.그는 공원을 [89]짓기 위해 인근 오렌지 카운티 로스앤젤레스 남동쪽 애너하임의 160에이커(65ha)의 오렌지 밭을 에이커당 6,200달러에 매입했다.1954년 7월 12일 공원 공사가 시작되었기 때문에 월트는 1955년까지 깨끗하고 [90]완벽한 스토리텔링 볼거리와 구역이 있는 공원이 완성되기를 원했다.

그들은 손님들이 주로 미주리주 [91]마르셀린에 있는 월트의 고향에서 출발한 20세기 초 미국의 작은 마을들을 테마로 한 메인 스트리트로 들어가 거리를 걸으며 다른 테마로 [92][93]된 땅이 뻗어 있는 중앙 허브로 들어가도록 설계했다.중앙 허브의 거리 끝에는 독일의 노이슈반슈타인 성에서 영감을 받아 4년 [94][95]후에 개봉될 같은 이름의 디즈니 영화에 나오는 성을 기반으로 한 77피트(23m) 높이의 잠자는 숲속의 공주 성이 있을 것이다.허브에서 뻗어나간 공원의 4개의 다른 테마 땅은 19세기의 미국 프런티어랜드, 야생 열대 정글을 닮은 어드벤처랜드, 디즈니의 애니메이션 동화 영화를 바탕으로 한 판타지랜드, 그리고 특히 미래의 풍경을 묘사하는 투모로우랜드로 구성될 것입니다.페이스 [96][97]에이지공원이 문을 열었을 때, 그 회사는 [98]총 1,700만 달러의 건설비가 들었다.

1953년 2월, 디즈니의 다음 애니메이션 영화인 피터팬이 개봉되어 성공을 거두었지만, 월트는 비용을 [99]올리지 않고 애니메이션을 개선할 수 있는 방법을 찾고 싶었다.디즈니가 트루라이프 다큐멘터리를 위해 두 편의 단편 영화인 "살아있는 사막"으로 특집을 만들고 싶었을 때, RKO의 변호사는 그것이 패키지로 판매된다면 1948년 반독점 대법원 판결을 어길 것이라고 믿었다.로이는 회사가 RKO 없이도 잘 될 것이라고 생각했고,[100] 회사는 스튜디오가 위치한 거리의 이름을 딴 자체 배급 회사 부에나 비스타 유통을 설립하여 그때부터 자신들의 영화를 배급했다.1954년, 디즈니의 첫 미국 실사 영화인 20,000 리그 언더 더 시네마 [101][102]스코프를 사용한 첫 번째 영화 중 하나가 개봉되었다.1950년대 초반부터 중반까지, 월트는 애니메이션 부서에 관심을 덜 쏟기 시작했고, 비록 스토리 미팅에 항상 참석했지만, 대부분의 운영을 그의 주요 애니메이션 제작자들에게 맡겼다.대신, 그는 텔레비전과 디즈니랜드와 [103]같은 다른 것들에 집중하기 시작했다.

공원을 조성하기 위한 자금을 마련하기 위해, 그 회사는 텔레비전 시리즈를 통해 공원을 홍보하기로 결정했다.1954년, NBC와 CBS가 계약을 맺기 위해 노력한 후, ABC는 디즈니랜드라고 불리는 10월부터 1시간짜리 주간 시리즈를 디즈니와 계약했다. 이 시리즈는 애니메이션 만화, 실사 특집, 스튜디오의 도서관에 있는 다른 자료들로 구성되어 있으며, 4개의 다른 영역의 4개의 다른 부분들을 거쳐갈 것이다.이 [104]시리즈는 성공적이었고 관객과 [105]평론가들의 찬사와 함께 시간대별로 50% 이상의 시청자를 얻었다.월트는 지난 8월 디즈니, 20년 이상 디즈니 서적의 출판사였던 웨스턴 퍼블리싱, ABC와 함께 이 [106]테마 파크의 자금 조달을 위해 또 다른 회사를 설립했습니다.

디즈니랜드의 성공과 함께, ABC는 디즈니가 매일 디즈니 만화, 어린이 뉴스릴, 그리고 장기자랑과 같은 것들을 보여주는 어린이 전용 버라이어티 쇼인 미키 마우스 클럽 시리즈를 제작하도록 허락했다.그것은 각각 [107]"Mousketeers"와 "Mooseketeers"라고 불리는 사회자와 재능 있는 어린이들과 어른들로 구성될 것이다.첫 번째 시즌이 끝난 후, 1,000만 명 이상의 어린이와 절반의 어른들이 매일 그것을 시청했고, 출연자들이 착용한 200만 개의 미키 마우스 귀가 팔렸으며, 프로그램의 메인 진행자 중 한 명인 지미 도드가 쓴 쇼 주제곡 "미키 마우스 행진곡"은 [108]고전이 되었다.1954년 12월 15일, 디즈니랜드는 5부작 미니시리즈 데이비 크로켓의 에피소드를 방영했는데, 이 에피소드는 페스 파커가 크로켓으로 출연했다.작가 닐 가블러는 크로켓 쿤스킨 [109]모자를 1,000만 개 팔면서 "하루아침에 전국적인 센세이션을 일으켰다"고 말했다.이 쇼의 주제곡 '데이비 크로켓의 발라드'는 세 마리 돼지의 'Who's Fraid of the Big Bad Wolf'만큼이나 미국 대중문화 전반에 퍼져 1000만 장의 음반을 판매했다.로스앤젤레스타임스는 이를 "세계에서 본 것 중 가장 위대한 상품화 유행"[110][111]이라고 평가했다.1955년 6월, 디즈니의 15번째 애니메이션 영화인 "레이디와 트램프"가 개봉되었고 [112]백설공주 이후 다른 디즈니 영화들보다 박스 오피스에서 더 좋은 성적을 거두었다.

1955년 7월 17일 일요일, 디즈니랜드는[b] 메인 스트리트만 완공되고 다른 땅은 몇 가지 놀이기구를 제공하는 총 20개의 놀이기구를 가지고 개장했다.그 당시에는 공원에 입장하는 데 1달러가 들었고 손님들은 각각의 개인 [113]승차료를 지불해야 했다.그들은 11,000명의 손님을 맞을 준비가 되어 있었지만, 위조 티켓이 쇄도하여 약 28,000명의 사람들이 나타났다.오프닝은 월트의 친구였던 배우 아트 링크레터, 밥 커밍스, 로널드 레이건 등이 진행하는 ABC에서 방영되었다.그것은 9천만 명 이상의 시청자를 끌어 모으며, 그 [114]날 현재까지 가장 큰 생방송이 되었다.개막은 너무 비참하고 성급해서 직원들에게 "블랙 선데이"라고 불릴 정도였다.식당들은 음식이 떨어졌고, 마크 트웨인 리버 보트는 약간 가라앉기 시작했고, 몇 번의 승차 오작동이 일어났으며, 음용수는 화씨 100도에서 작동하지 않았다.(38°C)의 [115][98]열개장 첫 주 동안 디즈니랜드는 161,657명의 손님이 방문했고 개장 첫 달에는 매일 20,000명 이상의 방문객이 방문했습니다.개장 1년 만에 360만 명이 찾았고 개장 2년 만에 400만 명이 더 찾아 그랜드 캐니언이나 옐로스톤 파크 같은 곳보다 더 인기가 많았다.그 해 디즈니는 총 2,450만 달러를 벌었는데, 이는 전년도의 1,[116]100만 달러와 비교된다.

월트는 영화보다 공원 일 때문에 더 바빴지만, 1950년대와 [117]60년대에 걸쳐 매년 평균 5편의 개봉작을 제작했다.만들어진 애니메이션 영화들은 잠자는 숲속의 공주, 100과 1의 달마시안, 그리고 [118]돌 속의 검과 같은 영화들이다.Sleeping Beauty는 회사의 재정적 손실이었고 디즈니는 그 시점까지 6백만 [119]달러의 영화 제작비를 지불했지만, One Thought and One Dalmatians는 드로잉을 전자적으로 애니메이션 [120]셀에 전송하기 위해 Xerography 프로세스를 사용하여 애니메이션을 만드는 새로운 방법을 도입했다.1956년, 셔먼 형제인 로버트와 리차드는 TV 시리즈 조로의 [121]주제가를 만들어 달라는 요청을 받았다.디즈니는 나중에 그들을 전속 스태프 작곡가로서 고용할 것이고, 이것은 10년 협회일 것이다.그들은 그 당시 디즈니 영화를 위한 많은 곡들과 테마파크를 위한 곡들을 썼는데, 그 중 몇 곡은 [122][123]히트작이었다.1950년대 후반에 디즈니는 실사 영화인 섀기 독과 프레드 맥머레이 [118][125]주연의 부재자 교수(1961년)[124]로 코미디 장르에 뛰어들었다.

디즈니는 또한 폴리아나(1960년)와 스위스 가족 로빈슨(1960년)을 포함한 아동 도서를 바탕으로 한 여러 편의 실사 영화를 만들었다.아역 배우 헤일리 밀스는 폴리아나에서 주연을 맡아 아카데미 청소년상을 수상하게 되며, 그 외 디즈니 영화 5편에는 부모 트랩 (1961년)[126][127]에서의 쌍둥이 역할도 포함되어 있다.또 다른 아역 배우 케빈 코코란은 디즈니 실사 영화의 많은 부분에서 유명한 인물로, 미키 마우스 클럽의 연재물에 처음 등장했는데, 그곳에서 그는 그와 함께 지낼 별명인 무치라는 이름의 소년을 연기할 것이다.그는 폴리아나에서 밀스와 함께 일했고 올드 옐러, 토비 타일러, 스위스 가족 [128]로빈슨과 같은 영화에 출연했다.1964년, 라이브 액션/애니메이션 뮤지컬 Mary Poppins가 개봉되어 그 해의 가장 많은 수익을 올린 영화가 되었다.이 영화는 팝핀스 역의 줄리 앤드류스와 셔먼 브라더스를 위한 노래상을 포함하여 5개의 아카데미 상을 받았으며, 영화 "침침 셰리"[129][130]로 최우수 작품상을 수상했다.

1960년대 가디언이 "1960년대 월트 디즈니 프로덕션을 가장 많이 대표했던 인물"이라고 부른 딘 존스는 That Darn Cat!(1965년), 어글리 닥스훈트(1966년), 그리고 두 번째 속편인 허브를 포함한 10편의 디즈니 영화에 출연했다.디즈니의 1960년대 마지막 아역 배우는 [133]이 회사와 10년 계약을 맺은 커트 러셀이 될 것이다.그는 딘 존스와 함께 The Computer Weared Tennis Shoes, The Horse in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Booth Executive, 그리고 The Strongest Man in the [134]World와 같은 영화에 출연했다.

1959년 말, 월트는 플로리다 팜 비치에 기술적 [135]발전으로 가득 찬 도시, 내일의 도시라고 불리는 또 다른 공원을 짓겠다는 아이디어를 가지고 있었다.1964년, 회사는 플로리다 올랜도 남서쪽의 땅을 공원을 건설할 지역으로 선택했고 재빨리 27,000에이커의 땅을 인수했다.1965년 11월 15일, 월트는 로이, 플로리다의 현 주지사와 함께 디즈니 월드라는 또 다른 공원 계획을 발표했습니다. 디즈니 월드에는 매직 킹덤의 더 크고 정교한 버전인 골프 코스와 리조트 호텔이 근처에 있고, 파 파의 심장부가 될 것입니다.1967년까지,[136] 회사는 디즈니랜드에 여러 번 확장을 했는데, 그 중에는 뉴올리언스 스퀘어라고 불리는 새로운 지역도 있었다. 뉴올리언스 스퀘어는 대부분 상점들로 가득 차 있고 루이지애나 주 뉴올리언스의 외관을 기반으로 할 것이다.1966년부터 1967년까지 그들은 세 개의 놀이기구를 추가했다. 그것은 작은 세상, 디즈니랜드 철도, 그리고 캐리비안의 해적이다.총 2천만 달러의 비용이 들었는데,[137] 이것은 공원을 만드는 데 드는 비용보다 3백만 달러가 더 들었다.그들은 또한 오디오 애니매트로닉스를 사용한 최초의 명소였던 월트 디즈니의 마법에 걸린 티키 룸, 1967년 디즈니랜드로 옮기기 전 1964년 뉴욕 세계 박람회에서 첫 선을 보인 월트 디즈니의 진보의 회전목마, 그리고 한 달 후에 [93]개장했던 날으는 코끼리 덤보와 같은 몇 가지 놀이기구들을 그 전에 추가했다.

1964년 11월 20일, 월트는 월트가 자신의 회사를 가지고 있는 것이 법적 문제를 일으킬 것이라고 생각한 로이의 설득으로 대부분의 WED Enterprise를 월트 디즈니 프로덕션에 375만 달러에 팔았다.월트는 그의 개인 사업, 주로 디즈니랜드 철도와 디즈니랜드 모노레일을 [138]다루기 위해 레트로라고 불리는 새로운 회사를 설립했습니다.이 회사가 이 프로젝트를 후원할 사람을 찾기 시작했을 때, 월트는 [139]내일의 도시 이름을 실험 프로토타입 커뮤니티의 약자인 EPCOT로 변경했습니다.월트는 제1차 세계대전 이후 담배를 많이 피웠기 때문에 건강이 나빠지기 시작했고, 그는 세인트루이스를 방문했습니다. 1965년 11월 2일 조셉 병원, 테스트를 위해.의사들은 그의 왼쪽 폐에서 호두 크기의 반점을 발견했고 며칠 후 그것이 암이라는 것을 알게 되었다.2주 후, 그는 병원에서 퇴원했지만, 과도하게 자란 림프절은 그가 더 이상 살 수 없다는 것을 보여주었다.1966년 12월 15일, 65세의 나이로 월트는 폐암에 [140][141]의한 순환기 파탄으로 사망했습니다.

1967-1984: 로이 O. 디즈니의 리더십과 죽음, 월트 디즈니 월드, 애니메이션 산업의 쇠퇴, 터치스톤 픽처스

1967년 월트가 작업한 마지막 두 편의 영화, 향후 20년간 디즈니의 가장 성공적인 영화가 될 애니메이션 영화 정글북, 그리고 실사 뮤지컬 "행복한 [142][143]백만장자"가 개봉되었다.월트가 죽은 후, 이 회사는 애니메이션 산업을 대부분 포기했지만, 여전히 몇몇 실사 영화를 [144][145]제작할 것이다.애니메이션 분야 직원은 500명에서 125명으로 줄어들기 시작했고 1970년부터 [146]1977년까지 21명만 고용했다.디즈니의 첫 포스트 월트 애니메이션 영화 아리스토캣스는 1970년에 개봉되었는데, 시카고 트리뷴의 데이브 케어는 "월트의 손이 없는 것이 [147]명백합니다."라고 말했다.이듬해 안티파시스트 뮤지컬 베드노브스와 브룸스틱스가 개봉돼 오스카 특수 시각효과상을 [148]수상했다.월트가 죽었을 때, 로이는 은퇴할 준비가 되었지만 월트의 유산을 유지하기를 원했고 회사의 [149][150]첫 번째 CEO이자 이사회 의장이 되었다.1967년 5월, 그는 플로리다 주의 입법부에서 디즈니 월드가 리디 크릭 개선구라고 불리는 지역에 준정부 기관을 가질 수 있도록 허용하는 법안을 통과시켰고, 그는 나중에 사람들에게 이것이 월트의 [151][152]꿈이라는 것을 상기시키기 위해 디즈니 월드의 이름을 디즈니 월드에서 월트 디즈니 월드로 바꿨다.시간이 흐르면서, EPCOT는 내일의 도시가 되었고 또 다른 놀이공원으로 [153]발전했다.약 4억 달러가 소요된 18개월간의 공사 후, 월트 디즈니 월드의 첫 번째 공원인 매직 킹덤은 디즈니의 컨템포러리 리조트,[154] 디즈니의 폴리네시아 리조트와 함께 1971년 10월 1일 10,000명의 방문객과 함께 개장했다.4,000명의 디즈니 연예인 및 미군 합창단과 함께 1,000명이 넘는 밴드 멤버들이 모인 퍼레이드는 작곡가 메레디스 윌슨이 이끄는 메인 스트리트를 행진했다.디즈니랜드와 달리 이 공원의 아이콘은 잠자는 숲속의 공주성 대신 신데렐라성이 될 것이다.3개월 후 추수감사절 날, 매직 킹덤에 들어가려는 차량들이 [155][156]주간 고속도로를 따라 수 마일에 걸쳐 늘어섰다.

1971년 12월 21일 로이는 세인트루이스에서 뇌출혈로 사망했다.조셉 병원.[150]로이의 사망 후 25년간 수석 이그제큐티브로 디즈니 사장을 지낸 돈 테이텀이 비디즈니 가족으로는 처음으로 CEO 겸 이사회 의장이 됐고 1938년부터 이 회사에 [157][158]몸담아온 카드 워커가 사장이 됐다.1973년 6월 30일까지 디즈니는 23,000명이 넘는 직원을 거느렸고 9개월 동안 총 257,751,000달러를 벌었는데, 이는 그들이 2억2,026,[159]000달러를 벌었던 전년도에 비해 증가한 것이다.11월에 디즈니는 또 다른 애니메이션 영화인 로빈 후드를 개봉했는데, 이 영화는 1,800만 [160]달러로 디즈니의 가장 큰 국제 수입 영화가 되었다.1970년대 내내 디즈니는 컴퓨터 웨어 테니스화의 속편인 '나우 유 시 힘', '나우 유 돈',[161] '러브 벅'의 두 속편인 '허비 라이즈 어게인'과 '하비 고즈 투 몬테 카를로', '마녀산으로 탈출',[162][163] '마녀산으로'[164]와 같은 실사 영화들을 개봉했다.1976년, 카드 워커가 회사의 CEO를 이어받았고, 테이텀은 1980년까지 회장으로 남아 있다가 워커가 그의 [149][158]뒤를 이었다.1977년, 로이 O. 디즈니의 아들이자 이 회사에서 일하는 유일한 디즈니인 로이 E. 디즈니는 회사의 결정에 [166]불복하여 회사의 임원직을 사임할 것이다.

1977년 디즈니는 성공적인 애니메이션 영화 "구조대"를 제작하여 박스 [167]오피스에서 4,800만 달러를 벌어들였다.라이브 액톤/애니메이션 뮤지컬 '피트 드래곤'은 1977년에 개봉되어 미국과 캐나다에서 1,600만 달러의 수익을 올렸지만, [168][169]이 회사는 실망스러운 것으로 간주되었다.1979년 디즈니의 첫 PG 등급 영화이자 지금까지 가장 비싼 영화인 '블랙홀'이 개봉되어 디즈니가 특수 효과도 사용할 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.스타워즈(1977년)처럼 흥행에 성공할 것이라고 생각했던 회사에 실망스러운 3,500만 달러의 수익을 올린 이 영화는 [170][171]개봉되고 있는 다른 공상과학 영화들에 대한 반응이었다.9월에, 부서의 15%가 넘는 12명의 애니메이션 제작자들이 스튜디오에서 사임했다.Don Bluth가 이끄는 그들은 트레이닝 프로그램 및 스튜디오 분위기와의 갈등으로 회사를 떠나 그들만의 회사 Don Bluth Productions(이후 Sullivan Bluth Studios)[172][173]를 설립했습니다.1981년, 디즈니는 덤보를 VHS에, 그리고 그 다음해 앨리스 인 원더랜드를 출시했고, 결국 디즈니는 그들의 모든 영화를 홈 미디어에 [174]공개하도록 이끌었다.7월 24일, 디즈니 캐릭터들을 주인공으로 [175][176]한 2년간의 아이스쇼 투어인 월트 디즈니 월드 온 아이스(Walt Disney World on Ice)가 디즈니가 Feld Entertainment에 캐릭터를 라이선스한 후 Brendan Byrne Meadowlands Arena에서 초연되었다.같은 달, 디즈니의 애니메이션 영화 "The Fox and the Hound"가 개봉되었고 3990만 [177]달러로 그 시점까지 가장 많은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되었다.이 영화는 월트가 전혀 관련이 없는 첫 번째 영화였고 디즈니의 나인 올드맨에 의해 만들어진 마지막 주요 작품이어서 젊은 애니메이션 제작자들이 더 [146]많은 일을 할 수 있도록 길을 열어주었다.

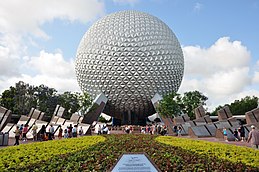

1982년 10월 1일, 이 회사의 수익이 감소하기 시작하자, 당시 엡콧 센터로 알려진 엡콧은 개장 [178][179]기간 동안 약 10,000명이 참석한 가운데 월트 디즈니 월드의 두 번째 테마 파크로 개장했다.이 공원은 건설에 9억 달러가 넘는 비용을 들여 멕시코, 중국, 독일, 이탈리아, 미국, 일본, 프랑스, 영국, 캐나다 등 9개국을 대표하는 미래세계관과 월드쇼케이스(World Showcase)[178][180]로 구성됐다.애니메이션 산업은 계속 하락해, 동사의 수익의 69%가 테마 파크로부터 나왔고, 월트 디즈니 월드의 1200만명의 관람객이 내년 [178]6월에 5%감소할 예정입니다.7월 9일 디즈니는 컴퓨터 생성 이미지(CGI) 트론을 주로 사용한 최초의 영화 중 하나를 개봉했는데,[181] 이는 비록 엇갈린 평가만 받았지만 다른 CGI 영화에도 큰 영향을 미칠 것이다.1982년에는 총 2,700만 [182]달러의 손실을 보았다.1983년 4월 15일 디즈니랜드와 매직킹덤과 비슷한 디즈니 최초의 외국 공원 도쿄 디즈니랜드가 일본 [183]우라야스에 문을 열었다.약 14억 달러가 투입된 이 공원 건설은 디즈니와 오리엔탈 랜드 컴퍼니가 함께 공원을 짓기로 동의한 1979년에 시작되었다.개장 후 10년 만에 이 공원은 1억 4천만 [184]명 이상의 방문객으로 히트를 쳤다.1억 달러의 투자 후, 디즈니는 4월 18일 디즈니 영화, 12개의 다른 프로그램, 그리고 성인들을 위한 두 개의 잡지 쇼와 같은 것을 보여주는 16시간짜리 케이블 텔레비전 시리즈인 디즈니 채널이라는 것을 보기 위해 돈을 지불하기 시작했다.잘 될 것으로 예상되었지만, 이 회사는 첫해 이후 약 91만 6천 명의 [185][186]가입자를 가지고 4830만 달러의 손실을 보았다.

1983년 월트의 사위 론 W 밀러가 1978년부터 이 회사의 사장으로 있었고,[149][187] 레이먼드 왓슨은 디즈니사의 CEO가 되었다.론은 스튜디오에서 [188]좀 더 성숙한 영화를 요구했고,[182] 그 결과 디즈니는 1984년 성인들과 청소년들을 위한 영화를 제작하기 위해 영화 배급사인 터치스톤 픽처스를 설립했다.스플래시 (1984년)는 레이블로 개봉된 첫 번째 영화였고,[189] 개봉 첫 주에 610만 달러의 수익을 올리며 스튜디오에 매우 필요한 성공작이 될 것이다.후에, 디즈니의 첫 번째 R 등급 영화인 "Down and Out in Beverly Hills"가 개봉되었고 [190]6,200만 달러의 수익을 올리며 이 회사의 또 다른 히트작이 되었다.이듬해 디즈니의 첫 PG-13 등급 영화인 Adventures in Babysiting이 개봉되었다.[191]1984년 Saul Steinberg는 회사 주식의 11.1%를 보유하면서 회사를 인수하려고 했습니다.그는 회사의 49%를 13억 달러에 사들이거나 회사 전체를 27억 5천만 달러에 사들이겠다고 제안했습니다.1천만 달러 미만의 자산을 가지고 있던 디즈니는 거절했고 그의 모든 주식을 3억 2,550만 달러에 사겠다고 제안했다.스타인버그는 이에 동의했고 디즈니는 은행으로부터 받은 13억 달러의 대출금 중 일부를 갚아 8억 6천 6백만 달러의 부채를 [192][193]떠안게 되었다.

1984-2005: 마이클 아이스너의 리더십, 디즈니 르네상스, 합병 및 인수

1984년 회사의 주주인 로이 E. 디즈니, 시드 배스, 릴리안과 다이애나 디즈니, 어윈 L. 제이콥스는 회사의 총 주식의 약 35.5%를 가지고 있던 Miller를 CEO로 밀어내고 이전에 Paramount의 사장이었던 Michael Eisner와 함께 CEO로 교체했다.웰스는 [194]대통령이다.디즈니에서 아이스너의 첫 행보는 그 당시에는 고려되지 않았던 주요 영화 스튜디오로 만드는 것이었다.그는 애니메이션 산업을 돕기 위해 제프리 카젠버그를 회장으로, 로이를 애니메이션 부문장으로 영입했다.그는 회사가 해왔던 것처럼 4년마다 제작하는 것이 아니라 18개월마다 애니메이션 영화를 제작하기를 원했다.영화 부문을 돕기 위해, 그들은 터치스톤을 통해 여러 영화를 제작하고 상품화할 새로운 디즈니 캐릭터를 만들기 위해 토요일 아침 만화를 만들기 시작했다.아이스너는 터치스톤 TV를 만들고 골든 걸스를 제작함으로써 디즈니를 텔레비전 산업에 더 많이 이끌었고, 이는 히트를 쳤습니다.이 회사는 또한 처음으로 1500만 달러에 테마파크를 홍보하기 시작했고,[195][196] 입장률을 10%까지 끌어올렸다.1984년 디즈니는 4,000만 달러로 가장 비싼 애니메이션 영화를 만들었고, 컴퓨터 제작 이미지인 블랙 코울드론을 다룬 첫 번째 애니메이션 영화이기도 하다. 이 영화는 더 어두운 테마 때문에 그들의 첫 번째 PG 등급 애니메이션 영화이기도 하다.그것은 결국 흥행 폭탄이 되었고, 회사는 애니메이션 부서를 [197]버뱅크의 스튜디오에서 캘리포니아 글렌데일의 창고로 옮기게 만들었다.1985년에 조직된 Silver Screen Partners II는 1억9천300만 달러를 들여 디즈니를 위한 LP 영화들을 후원했다.1987년 1월, Silver Screen III는 E.F.에 의한 영화 자금 조달 유한 제휴를 위해 가장 많은 3억 달러를 모금하여 디즈니를 위한 영화 자금 조달을 시작했습니다.허튼.[198]실버 스크린 IV는 또한 디즈니의 스튜디오에 자금을 [199]대기 위해 설치되었다.

1986년, 회사는 월트 디즈니 프로덕션에서 현재의 이름인 월트 디즈니 컴퍼니로 이름을 바꾸었고, 옛 이름은 영화 [200]산업만을 지칭한다고 말했다.디즈니의 애니메이션 산업이 쇠퇴함에 따라, 애니메이션 부서는 그들의 다음 영화인 "위대한 마우스 탐정"의 흥행이 필요했다.개봉 기간 동안 2,500만 달러의 총 수익을 올리며 애니메이션 [201]업계에서 이 회사에 매우 필요한 재정적 성공이 되었다.머천다이징으로 더 많은 수익을 창출하기 위해 1987년 글렌데일에 첫 번째 소매점을 열었다.그 성공으로 그들은 캘리포니아에 두 개의 매장을 더 열었고 1990년에는 [202][203]전국에 215개의 매장을 열었다.1989년에는 4억1100만달러의 수익과 1억8700만달러의 [204]이익으로 재무적인 성공을 거두었다.1987년 프랑스 정부와 계약을 맺고 파리에 디즈니랜드와 월트 디즈니 스튜디오 파크, 골프장, 호텔 [205][206]6개로 구성된 리조트를 짓기로 했다.

1988년, 디즈니의 27번째 애니메이션 영화 올리버 앤 컴퍼니가 전 애니메이션 제작자 돈 블루스의 The Land Before Time과 같은 날 개봉되었다. 올리버 앤 컴퍼니는 첫 개봉에서 1억 달러 이상의 수익을 올린 최초의 애니메이션 영화이자 첫 [207][208]개봉부터 가장 많은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되면서, The Land Before Time을 제쳤다.그 당시 디즈니는 Who Framed Rodger Rabbit (1988년), Three Men and a Baby (1987년), 그리고 베트남 굿모닝 (1987년)과 같은 영화로 할리우드의 모든 스튜디오 중 처음으로 흥행 선두에 올랐다.1983년의 총수입은 1억6천500만달러, 1987년에는 8억7천600만달러로 증가했으며, 영업수입은 1983년 마이너스 3천300만달러에서 1987년에는 플러스 1억3천만달러로 증가했습니다.순이익은 66% 증가했고 수익도 26% 증가했습니다.로스앤젤레스타임즈는 디즈니의 부활을 "기업 [209]세계에서는 정말 드문 일"이라고 평가했다.1989년 5월 1일 디즈니는 당시 디즈니-MGM 스튜디오로 불렸던 월트 디즈니 월드에 세 번째 놀이공원을 열었다.이 공원은 2008년까지 손님들이 [210]영화 속에 있는 것처럼 느끼도록 바뀌기 전까지는 주로 영화가 만들어지는 방법에 관한 것이었다.헐리우드 스튜디오의 개장에 이어 디즈니는 1989년 6월 1일 워터파크 태풍 라군을 개장했다; 2008년 워터파크에는 [211]총 280만 명의 사람들이 참석했다.1989년 디즈니는 설립자인 무펫 제작자 짐 헨슨으로부터 짐 헨슨 프로덕션을 인수하는 원칙적인 계약을 체결했습니다.이 계약에는 헨슨의 프로그래밍 라이브러리와 머펫 캐릭터(세서미 스트리트를 위해 만들어진 머펫 제외), 짐 헨슨의 개인 크리에이티브 서비스가 포함되어 있었다.그러나 헨슨은 거래가 성사되기 전인 1990년 5월 돌연 사망했고, 그 결과 두 회사는 이듬해 [212][213][214]12월 합병 협상을 중단했다.

1989년 11월 17일, 인어공주는 개봉되었고 디즈니 르네상스의 시작이라고 여겨진다. 디즈니 르네상스는 이 기간 동안 회사가 매우 성공적이고 비평가들로부터 호평을 받았다.이 영화는 개봉 초기부터 가장 많은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되었고, 박스 오피스에서 2억 3천 3백만 달러를 벌어들였다.[215][216]디즈니 르네상스 기간 동안, 하워드가 1991년에 사망할 때까지, 디즈니의 몇몇 노래들은 작곡가 앨런 멘켄과 작사가 하워드 애쉬먼에 의해 쓰여졌다.두 사람은 모두 6곡을 작곡하여 아카데미상 후보에 올랐으며, 두 곡의 수상곡은 "Under The Sea"와 "Beauty and the Beast"[217][218]이다.영화 사운드트랙용 음악을 포함해 주류 음악에 맞춘 음악을 만들기 위해 디즈니는 1990년 [219][220]1월 1일 음반사인 할리우드 레코드를 설립했다.1990년 9월, 디즈니는 디즈니용으로 만들어진 인터스코프 영화를 위한 노무라 증권 계열사에 의해 최대 2억달러의 자금을 조달하기로 했다.10월 23일, 디즈니는 터치우드 퍼시픽 파트너스를 설립하여 실버 스크린 파트너십 시리즈를 대체하여 영화 스튜디오의 주요 [199]자금원으로 삼았다.디즈니의 첫 번째 애니메이션 속편인 The Rescuards Down Under는 1990년 11월 16일에 개봉되었고 디즈니와 루카스필름 픽사의 컴퓨터 사업부에 의해 개발된 디지털 소프트웨어인 Computer Animation Production System (CAPS; 컴퓨터 애니메이션 제작 시스템)을 사용하여 제작되었으며,[216][221] 완전한 디지털로 제작된 최초의 장편 영화가 되었다.비록 이 영화는 4,740만 달러의 수익을 올리며 박스 오피스에서 고전했지만,[222][223] 비평가들로부터 긍정적인 평가를 받았다.1991년, 디즈니와 픽사는 세 편의 영화를 함께 제작하기로 합의했는데, 첫 번째 영화는 [224]토이스토리였다.

다우존스앤컴퍼니가 산업 평균에서 세 개의 회사를 대체하려고 하는 가운데, 디즈니는 5월에 "경제에서 엔터테인먼트와 레저 활동의 중요성"을 반영한다는 성명서와 함께 그 자리 중 하나를 채우기로 선택되었다.[225]디즈니의 다음 애니메이션 영화 '미녀와 야수'는 1991년 11월 13일에 개봉되었고 거의 [226][227]4억 3천만 달러의 수익을 올렸다.이 영화는 골든 글로브 최우수 작품상을 수상한 최초의 애니메이션 영화이며, 아카데미상 후보에 6개 오르며, 최우수 작품상 후보에 오른 최초의 애니메이션 영화가 되었다.[228]이 영화는 비평가들로부터 호평을 받았고, 일부는 이 영화가 최고의 디즈니 [229][230]영화라고 여겼다.그들의 새로운 출시와 동시에 디즈니는 1992년에 [231]NHL 팀인 The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim을 창단했다.디즈니의 다음 애니메이션 장편 알라딘은 1992년 11월 11일에 개봉되었고 5억 4백만 달러의 수익을 올리며 그 시점까지 가장 높은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되었고 5억 [232][233]달러를 기록한 최초의 애니메이션 영화가 되었다.이 곡은 "A Whole New World"로 아카데미 노래상과 최우수 [234]스코어상을 두 번 수상했다. "A Whole New World"는 올해의 [235][236]노래로 그래미상을 수상한 첫 번째이자 유일한 디즈니 곡이다.디즈니는 1993년 [237]독립 영화 배급사 미라맥스 필름을 인수함으로써 더 성숙한 영화를 확장시켰다.The Nature Conservancy와의 합작 사업에서 디즈니는 1993년 토종 동물과 식물 종을 보호하기 위해 플로리다에 8,500에이커(3,439ha)의 원수를 구입하여 디즈니 야생 보호 [238]구역을 설립했습니다.

1994년 4월 3일, 프랭크 웰스는 스키를 타러 휴가를 가던 중 헬리콥터 추락으로 사망했다.그와 아이스너, 그리고 Katzenberg는 1984년 [239]취임한 이후 회사의 시장 가치를 20억 달러에서 220억 달러로 끌어올리는데 도움을 주었다.6월 15일, 라이온 킹은 개봉되었고 엄청난 성공을 거두었다.이 영화는 총 9억 6,850만 [240][241]달러로 쥬라기 공원에 이어 역대 두 번째로 많은 수익을 올린 영화이자 역대 가장 많은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되었다.이 곡은 "Can You Feel the Love Tonight"로 아카데미 최우수 작품상과 노래상을 두 차례 수상했으며 비평가들의 [242][243]찬사를 받았다.출시 직후 카젠버그는 아이스너가 그를 사장으로 승진시키지 않자 회사를 떠났다.퇴사 후, 그는 영화 스튜디오 드림웍스 SKG를 [244]공동 설립하였다.웰스의 자리는 1995년 [245][246]8월 13일 아이스너의 친구 마이클 오비츠로 대체되었다.1994년에 디즈니는 ABC, NBC, 또는 CBS라는 빅3 방송사 중 하나를 인수하려고 노력해왔다. 이 회사는 그들에게 자사의 프로그램을 확실하게 배포할 수 있는 방송사를 제공하게 될 것이다.아이스너는 NBC를 인수하려 했으나 제너럴 일렉트릭이 과반수의 [247][248]지분을 보유하기를 원한다는 말을 듣고 거래는 취소되었다.1994년 디즈니는 101억 달러의 수익을 올렸고, 영화 산업은 전체의 48%, 테마 파크는 34%, 그리고 18%가 머천다이징에 의한 수익에 도달했습니다.디즈니의 총 순이익은 11억 달러로 전년보다 25%[249] 증가했다.3억 4천 6백만 달러의 수익을 올린 포카혼타스는 6월 16일 개봉하여 아카데미 뮤지컬/코미디 음악상과 "바람의 색깔"[250][251]로 최우수 노래상을 수상했다.픽사와 디즈니의 첫 번째 개봉작은 완전한 컴퓨터 제작 영화 토이 스토리였다.1995년 11월 19일 발매되어 비평가들의 호평을 받으며 총 3억 6천 1백만 달러의 흥행 수입을 올렸다.이 영화는 아카데미 특별공로상을 수상했을 뿐만 아니라 최우수 [252][253]각본상 후보에 오른 최초의 애니메이션 영화이기도 하다.

1995년 디즈니는 캐피털 시티/ABC Inc.를 190억달러에 인수했다고 발표했는데, 이는 당시 미국 역사상 두 번째로 큰 규모의 기업 인수였다.이 계약을 통해 디즈니는 방송 네트워크 ABC, 스포츠 네트워크 ESPN 및 ESPN 2의 지분 80%, Lifetime Television의 지분 50%, DIC Entertainment의 지분 50%, A&E Television Networks의 [249][254][255]지분 37.5%를 인수하게 된다.그 후, 동사는 1996년 [256][257]11월 18일, ABC 라디오 네트워크의 「라디오 디즈니」라고 불리는 청소년 전용의 라디오 프로그램을 개시했다.월트 디즈니사는 2월 22일 공식 웹사이트 disney.com를 개설했는데, 주로 테마파크를 홍보하고 상품에 [258]대한 정보를 제공하기 위해서였다.6월 19일, 이 회사의 다음 애니메이션 영화 "노트르담의 꼽추"가 개봉되어 박스 오피스에서 [259]3억 2,500만 달러를 벌어들였다.오비츠는 아이즈너와 경영 스타일이 달라 1996년 [260]사장직에서 해임됐다.디즈니는 1997년 9월 마수 B.V.에게 1040만 달러의 소송에서 패소했다. 이는 디즈니가 계약된 13개의 30분짜리 마수필라미 만화 쇼를 제작하지 못한 데 따른 것이다.대신, 디즈니는 다른 내부 "핫 부동산"이 회사의 [261]관심을 받을 만하다고 느꼈다.캘리포니아 에인절스의 지분 25%를 가진 디즈니는 1998년에 팀을 1억 1천만 달러에 인수하여 팀의 이름을 애너하임 에인절스로 바꾸고 경기장을 1억 달러에 [262][263]개조했다.헤라클레스는 6월 13일에 개봉하여 이전 영화들에 비해 흥행에서 저조한 성적을 거두어 [264]2억 5천 2백만 달러를 벌어들였다.2월 24일, 디즈니와 픽사는 디즈니를 배급사로 하여 5편의 영화를 함께 제작하기로 10년 계약을 맺었다.그들은 이 영화들을 디즈니 픽사 [265]제작물이라고 부르며 비용, 수익, 로고 크레딧을 공유할 것이다.디즈니 르네상스 당시 영화 부문은 1990년대 초인 영화(, 1990년대 초)는 미국 총 32억 달러(12억 달러)를 기록했다.n; 응, 맞다2억2천400만 [269]달러의 수익을 올린 컨에어(1997년)와 아마겟돈(1998년)[270]으로 1998년 최고 수익을 올린 영화입니다.

1998년 4월 22일, 디즈니 월드는 지구의 날에 580에이커(230ha)에 달하는 세계에서 가장 큰 테마 파크를 개장했습니다.그것은 동물학적인 주제를 바탕으로 6개의 땅으로 이루어져 있으며, 생명의 나무가 공원의 중심이고 2,000마리 이상의 동물이 [271][272]있다.디즈니의 다음 애니메이션 영화인 뮬란과 디즈니 픽사 영화 벅스 라이프가 각각 [273][274]6월 5일과 11월 20일에 개봉되었다.뮬란은 3억 4백만 달러로 1998년 6번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화가 되었고, 벅스 라이프는 3억 6천 [270]3백만 달러로 5번째로 높은 수익을 올렸다.6월 18일 7억 7천만 달러의 거래로 디즈니는 인터넷 검색엔진 인포섹의 지분 43%를 7천만 달러에 사들였고, 인포섹도 이전에 스타웨이브를 [275][276]인수했다.1994년 카니발과 로열 캐리비안의 협상이 잘 진행되지 않자 디즈니는 [277][278]1998년부터 크루즈 라인 운영을 시작할 것이라고 발표했다.디즈니 크루즈 라인의 첫 번째 두 배 부분은 디즈니 매직과 디즈니 원더로 명명될 것이며 이탈리아에서 핀칸티에리에 의해 만들어질 것이다.디즈니사는 유람선에 동행하기 위해 고다 케이를 이 노선의 전용 섬으로 사들여 2500만 달러를 들여 개조하고 이름을 캐스트어웨이 케이로 바꿨다.1998년 7월 30일, 디즈니 매직은 이 선의 첫 [279]항해로 출항했다.1999년 1월 12일 Infoseek과 합작하여 웹 포털 Go.com을 시작한 디즈니는 그 [280][281]해에 Infoseek의 나머지 부분을 인수했습니다.

디즈니 르네상스의 막을 내린 타잔은 6월 12일 개봉하여 박스 오피스에서 4억 4천 8백만 달러를 벌어들였고, 또한 필 콜린스의 "You'll Be in My Heart"[282][283][284][285]로 아카데미 원곡상을 수상했다.토이 스토리의 속편이자 디즈니 픽사 영화인 토이 스토리 2가 11월 13일 성공적인 영화로 개봉되어 5억 1,100만 달러의 흥행 [286][287]성적을 거두었다.2000년 [288][289]1월 25일, Ovitz의 자리를 메우고, Eisner는 ABC사의 네트워크 책임자 Bob Iger를 사장 겸 COO로 임명했습니다.디즈니는 11월에 DIC 엔터테인먼트를 앤디 휴워드에게 되팔았지만 여전히 그들과 [290]사업을 하고 있다.디즈니는 2001년에 몬스터 주식회사를 출시했을 때 픽사와 함께 또 다른 큰 성공을 거두었다.이후 디즈니는 어린이 케이블 방송사 폭스 패밀리 월드와이드를 30억 달러에 인수하고 23억 달러의 부채를 떠안았다.또, Fox Kids Europe, Latin American Fox Kids, Saban Entertainment의 프로그램 라이브러리의 6,500편 이상의 에피소드, [291]Fox Family Channel의 지분도 포함되어 있습니다.2001년 디즈니의 영업은 재정적자 1억5천8백만 달러, ABC 텔레비전 방송의 시청률 감소, 그리고 9.11 테러로 인한 관광 감소로 감소하였다.2001 회계연도의 디즈니의 수입은 1억 2천만 달러로 전년의 9억 2천만 달러보다 크게 줄었다.비용 절감을 돕기 위해 디즈니는 4,000명의 직원을 해고하고 300개에서 400개의 디즈니 [292][293]매장을 폐쇄할 것이라고 발표했다.2002년 월드 시리즈에서 우승한 후, 디즈니는 2003년 [294][295]사업가 아르투로 모레노에게 1억 8천만 달러에 엔젤스를 팔았다.2003년에 디즈니는 박스 오피스에서 [296]1년 만에 30억 달러를 벌어들인 최초의 스튜디오가 되었다.로이 디즈니는 2003년 회사의 운영 방식 때문에 은퇴를 선언하며 아이스너에게 은퇴를 요구했다. 같은 주에 이사회 멤버 스탠리 골드는 같은 이유로 퇴직을 선언하면서 "디즈니 구하기" 캠페인을 [297][298]함께 결성했다.

2004년, 회사의 연차총회에서 주주들은 43%의 투표로 아이즈너를 [299]이사회 회장직에서 물러나게 했다.3월 4일, 이사회의 멤버였던 조지 J. 미첼이 아이스너의 [300]후임으로 지명되었다.디즈니는 4월에 짐 헨슨 컴퍼니로부터 7500만 달러에 머펫 프랜차이즈를 인수했고, [301][302]그 과정에서 머펫 지주회사, LLC를 설립했습니다.디즈니-픽사 영화 인크레더블 (2004)과 9억 3,[303][304]600만 달러로 역대 두 번째로 높은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 된 니모를 찾아서 (2003)의 엄청난 성공에 이어,[305] 픽사는 2004년 디즈니와의 계약이 끝나자 새로운 배급사를 찾았다.디즈니 스토어가 고전하자 디즈니는 10월 [306]20일 313개의 체인점을 Children's Place에 매각했다.디즈니는 또한 2005년에 [307]마이티 덕스 NHL 팀을 헨리 사무엘리와 그의 아내 수잔에게 팔았다.로이는 회사에 재입사하기로 결심하고 "명예 감독"[308]이라는 직함을 가진 컨설턴트 역할을 맡게 되었다.

2005~2020년: Bob Iger의 리더십, 확장 및 디즈니+

2005년 3월 밥 아이거 사장이 9월 아이스너 퇴임 후 디즈니 CEO가 될 것이라는 발표가 있었다.아이거는 10월 [309][310]1일 공식적으로 디즈니 사장으로 임명됐다.디즈니의 11번째 테마파크 홍콩 디즈니랜드가 9월 12일 중국 홍콩에 문을 열었고,[311] 이 회사는 만드는 데 35억 달러가 들었다.2006년 1월 24일, 디즈니는 스티브 잡스로부터 픽사를 74억 달러에 인수하기 위한 움직임을 보였다.아이거는 픽사 CCO 존 라세터와 에드 캣멀 사장을 월트 디즈니 애니메이션 [312][313]스튜디오의 책임자로 임명했다.일주일 후, 디즈니는 ABC 스포츠 해설가 알 마이클스를 NBC뉴버설로 이적시켜 오스왈드 더 럭키 래빗과 26개의 오스왈드 [314]쇼츠에 대한 권리를 되찾았다.2월 6일, 이 회사는 ABC 라디오 네트워크와 22개 방송국을 27억 달러에 시타델 브로드캐스팅과 합병할 것이라고 발표했다.이 계약을 통해 디즈니는 텔레비전 방송사 시타델 [315][316]커뮤니케이션스의 지분 52%도 인수했다.디즈니 채널 영화 하이스쿨 뮤지컬이 방영되었고 사운드 트랙은 트리플 플래티넘을 기록하며 디즈니 채널 영화로는 처음으로 그렇게 [317]된 영화가 되었다.

디즈니의 2006년 실사 영화 캐리비안의 해적: 데드 맨 체스트는 디즈니의 가장 큰 히트작이자 박스 오피스에서 [318]10억 달러가 조금 넘는 수익을 올리며 역대 세 번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화였다.6월 28일, 이 회사는 이사회 멤버 중 한 명과 P&G의 전 CEO인 존 E로 조지 미첼을 대체할 것이라고 발표했다. 페퍼 주니어2007년에.[300]후속편인 하이스쿨 뮤지컬 2는 2007년 디즈니 채널에서 개봉되어 여러 케이블 시청률 기록을 [319]깼다.2007년 4월, 머펫 홀딩 컴퍼니는 디즈니 컨슈머 프로덕트에서 월트 디즈니 스튜디오 디비전으로 옮겨졌고,[320][321] 사업부의 재출시를 위한 노력의 일환으로 머펫 스튜디오로 이름을 변경했습니다.캐리비안의 해적: 앳 월드 엔드는 9억 [322]6천만 달러로 2007년 가장 많은 수익을 올린 영화가 되었다.디즈니 픽사 영화 '라타뚜이'와 '월-이'는 엄청난 성공을 거두었고,[323][324][325] 월-이 오스카 최우수 애니메이션상을 수상했다.디즈니는 폭스 패밀리 월드와이드 인수를 통해 제틱스 유럽 대부분을 인수한 뒤 2008년 [326]3억1800만달러에 회사를 완전히 장악했다.

밥 아이거는 2009년에 D23을 디즈니 공식 팬클럽으로 2년마다 열리는 D23 [327][328]엑스포와 함께 소개했다.2월에 디즈니는 향후 5년간 30편의 영화를 터치스톤 픽처스를 통해 배급하기로 드림웍스와 배급 계약을 발표했으며, 디즈니는 [329][330]총매출액의 10%를 받았다.널리 알려진 영화 업이 개봉되면서 디즈니는 박스 오피스에서 7억 3천 5백만 달러를 벌어들였고,[331][332] 이 영화는 오스카에서 최우수 애니메이션 장편영화상도 받았다.나중에 디즈니는 디즈니 [333]XD라는 이름의 나이 든 아이들을 위한 텔레비전 채널을 개설했다.디즈니는 지난 8월 마블 엔터테인먼트와 그들의 자산을 40억 달러에 인수했으며,[334] 이를 위해 슈퍼히로를 사용할 수 있게 되었다.디즈니는 9월에 News Corporation 및 NBC Universal과 제휴하여 스트리밍 서비스 Hulu의 지분 27%를 각각 획득하고 ABC Family와 Disney Channel을 스트리밍 [335]서비스에 추가했습니다.12월 16일, 로이 E. 디즈니는 디즈니 가족 중 [336]디즈니를 위해 적극적으로 일했던 마지막 사람으로 위암으로 세상을 떠났다.2010년 3월, Haim Saban은 700부작의 라이브러리를 포함한 Power Rangers 프랜차이즈를 약 [337][338]1억달러에 디즈니로부터 재취득했습니다.얼마 후 디즈니는 로널드 튜터가 이끄는 투자 그룹에 6억 6천만 [339]달러에 미라맥스 필름을 매각했다.그 기간 동안, 디즈니는 실사 영화인 이상한 나라의 앨리스와 디즈니 픽사 영화 토이스토리 3를 개봉했는데, 토이스토리 3는 10억 달러를 조금 넘는 수익을 올린 최초의 애니메이션 영화가 되었고, 가장 많은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되었다.그 해에 디즈니는 한 [340][341]해에 10억 달러짜리 영화 두 편을 개봉하는 최초의 스튜디오가 되었다.2007년에 ImageMovers Digital을 ImageMovers와 함께 시작한 후,[342] 디즈니는 2010년에 2011년까지 문을 닫을 것이라고 발표했다.

이듬해 디즈니는 그들의 마지막 전통적인 애니메이션 영화인 곰돌이 푸우를 [343]극장에 개봉했다.캐리비안의 해적 석방: On Stranger Tids는 10억 달러가 조금 넘는 수익을 거둬들였고, 이는 8번째 영화이자 디즈니의 세계에서 가장 높은 수익을 올린 영화가 되었으며,[344] 역대 세 번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화이기도 했다.2011년 1월, 디즈니 인터랙티브 스튜디오는 규모를 축소해,[345] 200명의 종업원을 해고했습니다.디즈니는 지난 4월 상하이 디즈니 리조트에 44억 달러를 들여 [346]새 테마파크를 착공했다.나중에, 8월에 밥 아이거는 픽사와 마블의 구매가 성공한 후, 그와 월트 디즈니 회사는 "훌륭한 캐릭터와 멋진 [347]이야기를 만들 수 있는 새로운 캐릭터나 사업을 구매하려고 한다"고 컨퍼런스 콜에서 말했다.2012년 10월 30일, 디즈니는 조지 루카스로부터 40억 5천만 달러에 루카스필름을 인수할 것이라고 발표했다.디즈니는 이 계약을 통해 2015년 첫 개봉을 시작으로 2, 3년 주기로 새 영화를 만들겠다고 밝힌 스타워즈, 인디애나 존스, 시각효과 스튜디오 인더스트리얼 라이트 & 매직, 비디오 게임 개발사 루카스 [348][349]아츠 등의 프랜차이즈 업체와 접촉하게 됐다.이후 2012년 [350]12월 21일에 판매가 완료되었다.

이후 2012년 2월 초 디즈니는 UTV Software Communications 인수를 완료하고 인도와 [351]아시아로 시장을 확대했습니다.3월에 Iger는 이사회 [352]의장직을 맡았다.마블 영화 어벤져스는 초기 개봉 총 13억 달러의 수익을 [353]올리며 역대 세 번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화가 되었다.박스 오피스에서 12억 달러 이상을 벌어들인 마블 영화 아이언맨3는 2013년에 [354]큰 성공을 거두었다.같은 해, 디즈니의 애니메이션 영화 겨울왕국이 개봉되었고 12억 [355][356]달러로 역대 가장 많은 수익을 올린 애니메이션 영화가 되었다.이 영화의 상품화는 매우 인기를 끌었고 그들은 1년 만에 10억 달러를 벌어들였고 이 영화의 상품 부족이 전세계적으로 일어났다.[357][358]2013년 3월, Iger는 개발 중인 2D 애니메이션 영화가 없다고 발표하였고, 한 달 후 손으로 그린 애니메이션 부문은 폐쇄되었고 몇몇 베테랑들은 [343]해고되었다.2014년 3월 24일 디즈니는 유튜브의 액티브 멀티채널 네트워크인 Maker Studios를 9억 [359]5천만 달러에 인수했다.

2015년 2월 5일, 토마스 O가 발표되었습니다. Staggs는 [360]COO로 승진했다.6월에 디즈니는 소비자 제품과 인터랙티브 사업부가 합병하여 디즈니 컨슈머 프로덕트와 인터랙티브 미디어의 [361]자회사를 신설할 것이라고 발표했다.8월에 마블 스튜디오는 재편성되어 월트 디즈니 스튜디오 [362]산하에 놓였다.8억 달러 이상의 수익을 올린 성공적인 애니메이션 영화 Inside Out의 개봉 후, 마블 영화 어벤져스는 다음과 같다. 에이지 오브 울트론은 개봉되었고 14억 [363][364]달러 이상의 수익을 올렸다.스타워즈: 포스가 개봉되어 20억 달러 이상의 수익을 올리며 역대 세 번째로 높은 수익을 [365]올린 영화가 되었다.10월에 디즈니는 텔레비전 채널 ABC 패밀리가 시청자의 범위를 [366][367]넓히는 것을 목표로 2016년에 프리폼으로 이름을 바꿀 것이라고 발표했다.2016년 4월 4일, 디즈니는 COO Thomas O를 발표했습니다.아이거에 이어 다음 순위로 여겨졌던 스태그스와 회사는 2016년 5월부로 26년간의 [368]회사 생활을 마감했다.2012년에 착공한 후, 상하이 디즈니랜드는 2016년 6월 16일에 회사의 여섯 번째 테마 파크 [369]리조트로 개장했습니다.스트리밍 서비스를 시작하기 위해 디즈니는 [370]8월에 MLB 기술 회사인 BAMTECH의 주식 33%를 10억 달러에 사들였다.2016년에 디즈니는 10억 달러 이상을 벌어들인 네 편의 영화를 가지고 있었는데, 그것은 애니메이션 영화 주토피아, 마블 영화 캡틴 아메리카였다. 시빌 워, 픽사 영화 도리를 찾아서, 그리고 로그 원은 디즈니를 국내 박스 [371][372]오피스에서 30억 달러를 넘어선 최초의 스튜디오로 만들었다.디즈니는 또한 그들의 콘텐츠와 상품을 마케팅하기 위해 소셜 미디어 플랫폼인 트위터를 사들이려고 시도했지만, 결국 그 거래에서 손을 뗐다.아이거는 그 이유는 회사가 필요하지 않은 책임을 떠맡을 것이라고 생각했기 때문이며 그에게 [373]디즈니는 느껴지지 않는다고 말했다.

2017년 3월 23일, 디즈니는 아이거 CEO의 임기를 2019년 7월 2일까지 1년 연장하기로 합의했으며,[374][375] 퇴임 후 컨설턴트로 3년간 회사에 남기로 합의했다고 발표했다.2017년 8월 8일, 디즈니는 BAMTECH의 기술을 바탕으로 2019년까지 자체 스트리밍 플랫폼을 출시할 의도로 스트리밍 서비스 넷플릭스와의 유통 계약을 종료할 것이라고 발표했다.그 기간 동안 디즈니는 BAMTECH의 지분 75%를 인수하기 위해 15억 달러를 투자했다.디즈니는 [376][377]또한 2018년까지 "연간 약 10,000개의 라이브 지역, 국가, 국제 게임 및 이벤트"로 ESPN 스트리밍 서비스를 시작할 계획이었다.지난 11월 존 라세터 CCO는 "실수" 때문에 회사를 6개월 동안 쉬겠다고 말했는데, 이는 나중에 성관계 비위 [378]의혹으로 알려졌다.같은 달, 디즈니와 21세기 폭스는 디즈니가 폭스의 [379]자산 대부분을 인수하는 협상을 시작했다.2018년 3월부터 전략적인 조직 개편으로 디즈니 파크, 익스피리언스 및 제품 및 Direct-to-Consumer & International이라는 두 개의 비즈니스 세그먼트가 탄생했습니다.파크&컨슈머 프로덕트는 주로 파크&리조트와 컨슈머 프로덕트&인터랙티브 미디어의 합병으로, Direct-to-Consumer & International은 Disney-ABC TV 그룹과 Studios Entertainment Plus Disney Digital Network에서 [380]디즈니 인터내셔널 및 글로벌 판매, 배급 및 스트리밍 유닛을 인수했습니다.아이거 CEO는 "미래를 위한 전략적인 사업 포지셔닝"이라고 표현했지만 뉴욕타임스는 21세기 폭스 매수를 [381]예상하고 조직 개편을 검토했다.

2017년 디즈니는 두 편의 영화가 10억 달러를 돌파했습니다. 실사 영화인 '미녀와 야수'와 '스타워즈'입니다. 마지막 제다이.[382][383]디즈니는 4월 [384]12일 스포츠 스트리밍 서비스 ESPN+를 시작했다.2018년 6월, 디즈니는 Lasseter가 연말까지 회사를 떠날 것이라고 선언하고,[385] 그때까지 컨설턴트로 남았습니다.그의 후임으로, 디즈니는 겨울왕국의 공동 감독이자 레크잇 랄프의 공동 작가인 제니퍼 리를 월트 디즈니 애니메이션 스튜디오의 책임자로, 그리고 1990년부터 픽사에서 일하며 업, 인크레더블, 인사이드 아웃을 감독한 피트 독터를 [386][387]픽사의 책임자로 승진시켰다.이달 말 컴캐스트는 21세기폭스를 510억달러에 인수하겠다고 제안했으나 디즈니가 710억달러로 맞섰고 컴캐스트는 폭스스카이 인수를 제안했다.디즈니는 또한 미국 법무부로부터 [388][389]폭스 인수를 위한 반독점 승인을 받았다.디즈니는 10억 달러를 벌어들인 세 편의 영화, 마블 영화, 블랙 팬더와 어벤져스로 2016년 기록을 갈아치운 것처럼 다시 박스 오피스에서 70억 달러를 벌어들였다. 인피니티 워와 픽사 영화 인크레더블 2는 인피니티 워가 20억 달러를 돌파하며 역대 [390][391]5번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화가 되었다.

2019년 3월 20일, 디즈니는 21세기 폭스의 자산을 소유주 루퍼트 머독으로부터 713억 달러에 인수하여 디즈니 역사상 최대 규모의 인수전이 되었다.구매 후, 뉴욕 타임즈는 디즈니를 "세계에서 [392]볼 수 없는 거대한 엔터테인먼트 기업"이라고 묘사했다.이 인수를 통해 디즈니는 20세기 폭스, 20세기 폭스 텔레비전, 폭스 서치라이트, 폭스 네트워크 그룹, 인도 텔레비전 방송사 스타 인디아, 스트리밍 서비스 스타+, 핫스타를 인수하여 Hulu의 지분을 최대 60%까지 보유하게 되었습니다.폭스사와 그 자산은 독점금지법 [393][394]때문에 거래에서 제외되었다.디즈니는 또한 마블의 캡틴 마블, 실사 알라딘, 픽사의 토이 스토리 4, 라이온 킹, 스타 워즈의 CGI 리메이크 작품인 스타 워즈 등 7편의 영화를 보유한 최초의 영화 스튜디오가 되었다. The Rise of Skywalker와 그 시점까지 27억 9천 7백만 달러의 수익을 올린 영화, Avatar (2009)[395][396]가 2021년에 중국에서 재발매되기 전에.11월 12일, 디즈니, 픽사, 마블, 스타워즈, 내셔널 지오그래픽, 그리고 다른 브랜드들의 500편의 영화와 7,500편의 TV 쇼가 있는 디즈니의 주문형 오버더 탑 스트리밍 서비스 디즈니 플러스가 미국, 캐나다, 네덜란드에서 시작되었다.첫날 스트리밍 플랫폼은 1,000만 명 이상의 가입자를 확보했고 2022년에는 1억 3,500만 명 이상의 가입자를 확보했으며 190개 이상의 [397][398]국가에 진출했습니다.2020년 초에 디즈니는 20세기 스튜디오와 서치라이트 [399]픽처스로 재상표하는 모든 자산에서 폭스라는 이름을 삭제했다.

2020–현재: 밥 차펙의 리더십, COVID-19 대유행 및 아이거의 복귀

밥 차펙은 이 회사에서 18년간 근무하며 디즈니 파크스 익스피리언스 앤 프로덕츠 회장을 역임했으며, 아이거가 2020년 2월 25일 퇴임한 후 디즈니의 CEO가 되었다.Iger는 회사의 창의적 [400][401]전략을 돕기 위해 2021년 12월 31일까지 임원 회장으로 회사에 머물 것이라고 말했습니다.4월에 Iger는 COVID-19 대유행 기간 동안 회사를 돕기 위해 전무 회장으로서 회사의 운영 의무를 재개했고 Chapek은 [402][403]이사회에 임명되었습니다.COVID-19 대유행 기간 동안 디즈니는 모든 테마 파크를 폐쇄하고, 개봉할 영화 몇 편을 연기했으며, 크루즈 [404][405][406]라인의 모든 운영을 중단했다.휴업으로 인해 디즈니는 10만 명의 직원들에게 급여를 지급하지 않을 것이지만, 미국 직원들에게 2조 달러의 경기부양 점검을 통해 정부 혜택을 신청하도록 촉구하면서, 회사가 매달 5억 달러를 절약할 것이라고 발표했다.게다가 아이거는 4750만 달러의 연봉을 모두 포기했고 샤펙은 50%의 [407]연봉을 삭감했다.

디즈니는 2020년 2분기 14억달러의 손실을 보고했으며, 수익은 전년 54억달러에서 4억7500만달러로 [408]91% 감소했다.8월까지 그 회사의 3분의 2는 대형 금융기관이 [409]소유하고 있었다.9월에는 파크, 익스피리언스 및 프로덕트 부문 직원 28,000명을 해고해야 했는데, 이 중 67%가 파트타임 근로자였습니다.조시 다마로 사업부 회장은 "처음에는 이 상황이 오래가지 않고 빨리 회복되어 정상으로 돌아오기를 바랐다"고 있었다.7개월 후에는 그렇지 않다는 것을 알게 되었습니다."게다가 디즈니는 2020년도 [410]3분기에 총 47억 달러의 손실을 보았다.디즈니는 지난 11월 파크스 익스피리언스 앤 프로덕츠 부문 직원 4000명을 추가로 해고해 직원 [411]수를 32,000명으로 늘렸다.다음 달, 디즈니는 영화 [412]스튜디오를 감독할 디즈니 스튜디오 콘텐츠 부서의 회장으로 앨런 버그먼을 임명했다.COVID-19 불황으로 디즈니는 2021년 [413]2월 20세기 스튜디오의 애니메이션 스튜디오 블루 스카이 스튜디오를 폐쇄했다.터치스톤 TV가 12월에 운영을 중단함에 따라, 디즈니는 2021년 3월에 성숙한 [414][415]시청자들을 집중 공략하기 위해 20번째 텔레비전 애니메이션의 새로운 부서를 출범시킬 것이라고 발표했다.지난 4월, 디즈니와 소니는 소니가 넷플릭스와의 계약이 [416]종료되면 2022년부터 2026년까지 소니의 영화를 TV 네트워크에서 방영하거나 디즈니+에서 스트리밍할 수 있도록 하는 다년간의 라이선스 계약에 합의했다.비록 COVID-19 때문에 박스 오피스에서는 잘 되지 않았지만, 디즈니의 애니메이션 영화 엔칸토의 개봉은 "We Don't Talk About Bruno"가 엄청난 [417][418]인기를 끌면서 대유행 기간 동안 가장 큰 히트작 중 하나였다.

12월 31일 이거의 회장 임기가 끝난 후, 그는 이사회 회장직도 사임할 것이라고 발표했다.그의 후임으로, 회사는 칼라일 그룹의 운영 임원과 현재 이사인 수전 아놀드를 디즈니의 첫 여성 [419]회장으로 영입했다.3월 10일, 디즈니는 러시아의 우크라이나 침공으로 인해 러시아에서 하던 모든 사업을 중단했다.디즈니는 러시아의 침공으로 인해 주요 영화 개봉을 중단한 최초의 할리우드 스튜디오였고,[420] 곧이어 다른 영화 스튜디오들도 그 뒤를 따랐다.2022년 3월 플로리다 공립학교 학군에서 성적 성향이나 성 정체성에 대한 교실 교육을 연령에 맞지 않는 방식으로 금지한 '플로리다 학부모 교육권법'에 대해 직원 60여명이 침묵을 지키는 것에 대한 회사의 대응에 항의했다."디즈니 더 베터 워크아웃"으로 불리는 직원들은 약 일주일 동안 디즈니 스튜디오 근처에서 시위를 벌였고, 다른 직원들은 소셜 미디어를 통해 우려의 목소리를 냈다.직원들이 디즈니 측에 법안을 지지한 플로리다 정치인들에게 선거 기부를 중단하고 직원들을 보호하며 플로리다 월트 디즈니 월드의 건설을 중단하라고 요구하자 차펙은 회사가 침묵을 지키는 실수를 저질렀다고 답하며 "우리는 LGBTQ+ 커뮤니티에 대한 지속적인 지지를 맹세한다"고 말했다.「[421][422]그것」입니다.

디즈니가 이 법안에 대한 반응을 보이는 가운데 플로리다 주 의회는 6월 [423]1일부로 론 드산티스 플로리다 주지사가 이 법안에 서명하면서 디즈니의 준정부 지역인 리디 크릭을 제거하는 법안을 통과시켰다.6월 28일, 디즈니의 이사진들은 만장일치로 샤펙에게 3년 계약을 [424]연장하는 것에 동의했다.지난 8월 디즈니 스트리밍은 2억2100만 명의 가입자를 확보해 넷플릭스를 제치고 2억2000만 [425]명의 가입자를 확보했다.

2022년 11월 20일, Iger는 실적 부진으로 Chapek의 뒤를 이어 CEO로 복귀했습니다.이사회는 Iger가 2년간 새로운 성장을 위한 전략을 개발하고 [426]후임자를 선정하는 데 도움을 줄 것을 명령받았다고 발표했다.

회사 단위

Walt Disney Company는 6개의 주요 비즈니스 세그먼트를 운영하고 있으며, 2개의 주요 부문과 4개의 콘텐츠 [427]그룹이 있습니다.

디비전

- 디즈니 미디어 및 엔터테인먼트 배포(DED)는 모든 글로벌 유통, 판매, 판매, 판매, 판매, 판매, 회사, 판매, 판매, 제품, 마케팅, 마케팅, 마케팅, 회사, 회사, 회사, 회사, 회사,-어, 엑스테네요. -네.r+), 극장 전시 유닛, 홈 미디어 배급, 디즈니 뮤직 그룹, ABC 소유 텔레비전 방송국 및 국내 TV 네트워크.[427]

- Disney Parks, Experience, and Products(DPEP)는 회사의 테마파크, 크루즈 라인, 여행 관련 자산, 소비자 제품 및 출판 부서를 감독합니다.디즈니의 리조트 및 다양한 관련 소유물은 다음과 같습니다.월트 디즈니 월드, 디즈니랜드 리조트, 도쿄 디즈니 리조트, 디즈니랜드 파리, 홍콩 디즈니랜드 리조트, 상하이 디즈니 리조트, 디즈니 바캉스 클럽, 디즈니 크루즈 라인, 어드벤처 by 디즈니.[429]그 부서는 조쉬 다마로가 [427]이끌고 있다.

콘텐츠 그룹

- 월트 디즈니 스튜디오는 월트 디즈니 픽처스, 월트 디즈니 애니메이션 스튜디오, 픽사, 마블 스튜디오, 루카스 필름, 20세기 스튜디오, 서치라이트 픽처스, 디즈니 네이처, 디즈니 극장 그룹을 포함한 회사의 영화화된 엔터테인먼트 및 극장 엔터테인먼트 사업체들로 구성되어 있습니다.그 부서는 Alan [427]Bergman이 이끌고 있다.

- 디즈니 종합 엔터테인먼트 컨텐츠(DGE)는, 월트 디즈니 텔레비전(ABC 텔레비전 네트워크, 디즈니 텔레비전 스튜디오 - ABC 시그니처, 서치 라이트 텔레비전, 20번째 텔레비전, 20번째 텔레비전 애니메이션 등, 미국의 엔터테인먼트 중심 텔레비전 채널과 제작사로 구성되어 있습니다.nd Freeform), 디즈니 브랜드 텔레비전, FX 네트워크, ABC 뉴스, 내셔널 지오그래픽 파트너의 73% 소유권.그 부서는 Dana [428][430][431]Walden이 이끌고 있다.

- ESPN 및 스포츠 콘텐츠는 케이블 채널, ESPN+ 및 ABC의 스포츠 뉴스, 스포츠 뉴스 및 오리지널 및 비스크립트 스포츠 관련 콘텐츠뿐만 아니라 ESPN의 라이브 스포츠 프로그래밍에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.그 부서는 제임스 [427]피타로가 이끌고 있다.

- Disney International Content and Operations는 4개의 다른 허브로 분할된 국제 선형 채널 및 스트리밍 서비스에 대한 광고 판매, 배포, 제작 및 운영을 관리함으로써 글로벌 시장과 연계된 지역 및 지역 콘텐츠를 감독하는 데 주력하고 있습니다.아시아 태평양, 유럽, 중동 및 아프리카(EMEA), 인도, 중남미.그 부서는 레베카 [432]캠벨이 이끌고 있다.

리더십

현재의

- 이사회[433]

- 이그제큐티브[433]

- CEO Bob Iger 씨

- Alan Bergman, Disney Studios 콘텐츠 회장

- Rebecca Campbell 회장, 국제 콘텐츠 및 운영 담당

- Jennifer Cohen, 기업의 사회적 책임 담당 이그제큐티브 바이스 프레지던트

- 디즈니 파크, 경험 및 제품 회장 Josh D'Amaro

- Horacio Gutierrez, 시니어 이그제큐티브 바이스 프레지던트 겸 제너럴 카운셀

- Jolene Negre, 준고문 겸 비서

- Alicia Schwarz, 수석 부사장 겸 최고 컴플라이언스 책임자

- 로널드 L.Iden, 시니어 바이스 프레지던트 겸 최고 보안 책임자

- Christine McCarthy, 수석 부사장 겸 최고재무책임자

- 카를로스 A.고메즈, 시니어 바이스 프레지던트 겸 재무 담당

- Diane Jurgens, 엔터프라이즈 테크놀로지 및 최고 정보 책임자, 이그제큐티브 바이스 프레지던트

- 알렉시아 S.Quadrani, 투자자 정보 담당 시니어 바이스 프레지던트

- Brent Woodford, 총괄, 재무 및 세무 담당 이그제큐티브 바이스 프레지던트

- ESPN 및 스포츠 콘텐츠 부문 회장 James Pitaro

- Paul Richardson, 시니어 이그제큐티브 바이스 프레지던트

- Latondra Newton, 수석 부사장, 최고 다양성 책임자

- Christina Schake, 시니어 이그제큐티브 바이스 프레지던트

- Dana Walden, Disney General Entertainment Contents 회장

과거의 리더십

- 경영자 회장

- 밥 아이거 (2020–2021)

- 체어맨

월트 디즈니는 회사의 창의적인 측면에 더 집중하기 위해 1960년 회장직에서 물러나 "모든 제작을 [434]담당하는 전무 프로듀서"가 되었다.

4년간의 공백 끝에 로이 O. 디즈니가 회장이 되었다.

- 월트 디즈니 (1945~1960)

- 로이 O. 디즈니 (1964-1971)

- 돈 테이텀(1971~1980)

- 카드 워커(1980-1983)

- 레이먼드 왓슨(1983년-1984년)

- 마이클 아이스너(1984~2004)

- 조지 J. 미첼(2004~2006)

- 존 E. 페퍼 주니어(2007~2012)

- 밥 아이거(2012~2021년)

- 수잔 아놀드 (2022년 ~ 현재)

- 부회장

- 프레지던트

- 월트 디즈니 (1923년-1945년)

- 로이 O. 디즈니 (1945-1968)

- 돈 테이텀(1968년-1971년)

- 카드 워커(1971~1980)

- 론 W. 밀러(1980-1984)

- 프랭크 웰스(1984~1994)

- 마이클 오비츠(1995~1997)

- 마이클 아이스너(1997~2000)

- 밥 아이거(2000~2012)

- 최고 경영자(CEO)

- 로이 O. 디즈니 (1929-1971)

- 돈 테이텀(1971년-1976년)

- 카드 워커(1976-1983)

- 론 W. 밀러(1983년-1984

- 마이클 아이스너(1984~2005)

- 밥 아이거(2005년~2020년, 2022년~현재)

- 밥 차펙 (2020–2022)

- 최고운영책임자(COO)

레거시

월트 디즈니사는 세계에서 가장 큰 엔터테인먼트 회사 중 하나이며 애니메이션 [436][437]산업의 선구자로 여겨지며 애니메이션 영화 중 122편과 함께 790편의 장편을 제작했다.피노키오, 토이 스토리, 밤비, 라따뚜이, 백설공주와 일곱 난쟁이, 메리 포핀스 [438][439][440]등과 같은 영화들을 포함하여, 그들의 많은 영화들은 역대 최고의 영화들로 여겨진다.2022년 현재, 이 회사는 총 135개의 아카데미 상을 수상했으며, 그 중 32개는 월트가 수상했다.그들은 아카데미 단편 애니메이션상 16개, 노래상 16개, 장편 애니메이션상 15개, 음악상 11개, 다큐멘터리상 5개, 시각효과상 5개 등 다양한 특별상을 [441]수상했다.또한 디즈니는 2022년 [442][443][444][d]현재 29개의 골든 글로브 상, 51개의 영국 아카데미 영화 및 텔레비전 예술상, 36개의 그래미 상을 수상했다.디즈니는 또한 미키 마우스, 우디, 캡틴 아메리카, 잭 스패로우, 아이언 맨, 그리고 [15][463][464]엘사와 같은 역대 가장 영향력 있고 기억에 남는 가상의 캐릭터들을 만들었다.

디즈니는 또한 애니메이션 산업에 혁명을 일으켜 인정받았다.Den of Geek은 첫 번째 애니메이션 영화인 백설공주와 일곱 난쟁이를 만드는 것의 위험이 "[465]영화관을 변화시켰다"고 말했다.이 회사는 주로 월트를 통해 캐릭터에 [466][143]개성을 더할 뿐만 아니라 애니메이션, 기술 혁신을 위한 더 진보된 기술을 도입했다고 한다.디즈니의 애니메이션 기술 혁신 중 일부는 멀티판 카메라, 제로그래피, 캡스, 딥 캔버스, 렌더맨의 [221]창조를 포함합니다.이 영화의 많은 디즈니 노래들 또한 빌보드 [467]핫 100 1위에 오르며 매우 인기가 많아졌다.실리 심포니 시리즈의 다른 노래들은 엄청난 인기를 끌었고 전국적으로 [25]들렸다.

디즈니는 2022년 포춘지 선정 미국 500대 기업 중 총 매출 53위, 2022년 포춘지 선정 "세계에서 가장 존경받는 기업"[1][468] 4위에 올랐다.스미스소니언 매거진은 디즈니 테마파크보다 더 강력한 순수한 아메리카나의 상징이 매우 적으며, 회사 이름과 미키 마우스가 "가계 이름"[469]인 등 "잘 확립된 문화적 아이콘"이라고 선언했다.디즈니는 또한 12개의 공원이 있는 테마파크 업계에서 가장 큰 경쟁사 중 하나이며, 이 모든 공원은 2018년에 가장 많이 방문한 25개의 공원이었다.디즈니는 전세계 테마파크에 1억 5천 7백만 명 이상의 방문객을 가지고 있으며, 세계에서 가장 많이 방문한 테마파크 회사가 되어 두 번째로 많은 방문객 수를 기록했다.1억 5천 7백만 명의 방문객 중, 마법 왕국은 총 2080만 명의 방문객을 차지하여 세계에서 [470][471]가장 많이 방문한 테마파크가 되었다.디즈니가 처음 테마파크 산업에 뛰어들었을 때, CNN은 "이미 전설적인 회사를 변화시켰다.그리고 그것은 모든 테마파크 [472]산업을 변화시켰습니다."월트 디즈니 월드는 또한 오렌지 카운티 [473]레지스터에 의해 "테마 파크가 어떻게 회사를 라이프스타일 브랜드로 만드는데 도움을 줄 수 있는지를 보여줌으로써 엔터테인먼트를 변화시켰다"고 한다.

비판과 논란

월트 디즈니사는 과거에 성차별적이고 인종차별적인 내용이라고 알려진 내용뿐만 아니라 그들의 영화에 성소수자 요소를 넣었고 LGBT의 대표성을 충분히 갖추지 못했다는 비판을 받아왔다.표절 의혹, 열악한 임금과 근로 조건 제공, 동물 학대 논란도 있었다.디즈니의 몇몇 영화들은 인종차별주의자로 여겨져 왔다.디즈니의 가장 논란이 많은 영화 중 하나인 Song of the South는 인종차별주의자로 묘사된 잘못된 고정관념을 가지고 있다는 비난을 받았다.이러한 이유로 이 영화는 홈 비디오나 디즈니 플러스에 [474]공개되지 않았다.인종차별주의자로 불린 또 다른 것들로는 환타지아의 하얀 백점을 섬기는 검은 백점박이 해바라기, 아시아인으로 지나치게 과장된 것으로 여겨지는 레이디와 트램프의 샴 고양이, 피터팬의 아메리카 원주민 부족에 대한 고정관념, 아프리카계 미국인으로 묘사되는 덤보의 까마귀 등이 있다.자이브를 사용하고 지도자의 이름은 짐 크로우(Jim Crow)로, 인종 [475][476]차별법을 지칭하는 인종차별적 용어로 여겨진다.디즈니+에서 잘못된 인종차별적 고정관념을 가지고 있다고 여겨지는 영화를 볼 때, 디즈니는 [477]논란을 피하기 위해 영화가 시작되기 전에 거부권을 추가했다.

디즈니는 또한 이미 존재하는 작품들의 영화 표절 때문에 여러 번 비난을 받아왔다.특히, 라이온 킹은 애니메이션 제작자 테즈카 오사무의 [478]'하얀 사자 김바'라는 애니메이션 시리즈와 캐릭터와 사건에서 많은 유사점을 가지고 있다는 비난을 받고 있다.디즈니가 애니메이션 쇼 나디아와 많은 유사점을 가지고 있다는 비판을 받은 또 다른 영화는 다음과 같다. 푸른 물의 비밀은 아틀란티스였습니다. 잃어버린 제국.비슷한 점이 너무 널리 알려져 스튜디오 제작자인 가이낙스는 디즈니를 고소하려 했으나 시리즈의 방송사인 [479]NHK에 의해 저지되었다.단편 눈사람 (2014)의 제작자 켈리 윌슨은 애니메이션 영화 겨울왕국에서의 그녀의 쇼트의 저작권 침해로 디즈니를 상대로 첫 번째 소송이 취하된 후 두 번의 소송을 제기했다.디즈니는 나중에 소송을 해결하고 그녀와 계약을 맺어 [480]이 영화의 속편을 제작할 수 있게 했다.시나리오 작가 게리 L. 골드만은 디즈니가 과거에 주토피아와 똑같은 제목의 이야기를 그들에게 던졌다고 주장하며 주토피아를 만든 것에 대해 디즈니를 고소했다.판사는 나중에 [481]표절을 입증할 충분한 증거가 없다며 소송을 기각했다.

디즈니는 그들의 영화에 LGBT 요소를 넣는 것과 그들의 미디어에 충분한 LGBT 대표성을 넣지 않는 것 둘 다로 비난을 받아왔다.실사 영화 '미녀와 야수'에서 빌 콘돈 감독은 르푸가 게이 캐릭터로 나올 것이라고 발표했다.이로 인해 쿠웨이트, 말레이시아, 앨라배마의 한 극장은 이 영화를 금지했고 러시아는 더 엄격한 [482]평가를 내렸다.러시아와 몇몇 중동 국가에서는 픽사 영화 '온워드'가 디즈니의 첫 공개 레즈비언 캐릭터인 '오피서 스펙터'를 출연시켰다는 이유로 상영 금지를 당했고, 반면 다른 이들은 디즈니가 LGBT를 [483][484]더 많이 대변할 필요가 있다고 말했다.두 명의 레즈비언들이 키스하는 장면 때문에 픽사의 라이트이어는 13개의 주요 이슬람 국가에서 상영이 금지되었고, 영화는 [485][486]박스 오피스에서도 거의 수익을 내지 못했다.유출된 디즈니 미팅 동영상에서 참석자들은 LGBT 테마를 회사 매체에 밀어넣는 것에 대해 이야기했고, 일부 참석자들은 디즈니가 "아이들을 성적으로 만들려고 한다"며 화를 냈고, 다른 참석자들은 그들의 [487]행동에 박수를 보냈다.

몇몇 디즈니 공주 영화들은 여성에 대한 성차별적인 것으로 여겨져 왔다.백설공주는 그녀의 외모에 대해 너무 걱정하고 있는 반면, 신데렐라는 재능이 없는 것으로 여겨진다.오로라는 또한 구조되기를 항상 기다리고 있기 때문에 강하지 않다고 한다.공주 영화에서 성차별주의자로 여겨지는 다른 점들은 그들 중 일부는 남성들이 더 많은 대화와 더 많은 말투를 가지고 있다는 것이다.디즈니의 새로운 영화들은 이전 영화들보다 [488]성차별에 관한 한 개선된 것으로 여겨진다.

1990년 디즈니는 디스커버리 섬에서 독수리를 때려죽이고 새를 쏘고 그 중 일부를 굶긴 혐의로 16건의 동물 학대 혐의로 법정에 서는 것을 피하기 위해 9만 5천 달러를 지불했다.그들은 다른 동물들을 공격하고 그들의 [489]먹이를 빼앗았기 때문에 그렇게 했다.애니멀 킹덤이 처음 문을 열었을 때, 몇몇 동물들이 죽었기 때문에 동물들에 대한 우려가 있었다.동물 보호 단체들의 항의가 일어났지만, 미국 농무부는 동물 복지 규정을 [490]위반하는 것을 발견하지 못했다.디즈니는 또한 열악한 근무 환경을 가지고 있다고 한다.디즈니랜드에서는 시간당 평균 13달러의 박봉에 대한 2,000명의 노동자들의 항의가 일어났으며, 일부는 그들이 그들의 [491]집이나 아파트에서 쫓겨났다고 말했다.2010년 디즈니 제품을 만들고 있던 중국의 한 공장에서 근로자들이 근무시간을 3배로 초과해 노동자들 중 한 명이 [492]자살했다.

재무 데이터

수익

| 연도 | 스튜디오 엔터테인먼트[e] | 디즈니 컨슈머 제품[f] | 디즈니 인터랙티브[493][494] 미디어 | 파크&리조트[g] | 디즈니 미디어[h] 네트워크 | 총 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 2,593.0 | 724 | 2,794.0 | 6,111 | [495] | ||

| 1992 | 3,115 | 1,081 | 3,306 | 7,502 | [495] | ||

| 1993 | 3,673.4 | 1,415.1 | 3,440.7 | 8,529 | [495] | ||

| 1994 | 4,793 | 1,798.2 | 3,463.6 | 359 | 10,414 | [496][497][498] | |

| 1995 | 6,001.5 | 2,150 | 3,959.8 | 414 | 12,525 | [496][497][498] | |

| 1996 | 10,095[f] | 4,502 | 4,190[i] | 18,739 | [497][499] | ||

| 1997 | 6,981 | 3,782 | 174 | 5,014 | 6,522 | 22,473 | [500] |

| 1998 | 6,849 | 3,193 | 260 | 5,532 | 7,142 | 22,976 | [500] |

| 1999 | 6,548 | 3,030 | 206 | 6,106 | 7,512 | 23,435 | [500] |

| 2000 | 5,994 | 2,602 | 368 | 6,803 | 9,615 | 25,402 | [501] |

| 2001 | 7,004 | 2,590 | 6,009 | 9,569 | 25,790 | [502] | |

| 2002 | 6,465 | 2,440 | 6,691 | 9,733 | 25,360 | [502] | |

| 2003 | 7,364 | 2,344 | 6,412 | 10,941 | 27,061 | [503] | |

| 2004 | 8,713 | 2,511 | 7,750 | 11,778 | 30,752 | [503] | |

| 2005 | 7,587 | 2,127 | 9,023 | 13,207 | 31,944 | [504] | |

| 2006 | 7,529 | 2,193 | 9,925 | 14,368 | 34,285 | [504] | |

| 2007 | 7,491 | 2,347 | 10,626 | 15,046 | 35,510 | [505] | |

| 2008 | 7,348 | 2,415 | 719 | 11,504 | 15,857 | 37,843 | [506] |

| 2009 | 6,136 | 2,425 | 712 | 10,667 | 16,209 | 36,149 | [507] |

| 2010 | 6,701[j] | 2,678[j] | 761 | 10,761 | 17,162 | 38,063 | [508] |

| 2011 | 6,351 | 3,049 | 982 | 11,797 | 18,714 | 40,893 | [509] |

| 2012 | 5,825 | 3,252 | 845 | 12,920 | 19,436 | 42,278 | [510] |

| 2013 | 5,979 | 3,555 | 1,064 | 14,087 | 20,356 | 45,041 | [511] |

| 2014 | 7,278 | 3,985 | 1,299 | 15,099 | 21,152 | 48,813 | [512] |

| 2015 | 7,366 | 4,499 | 1,174 | 16,162 | 23,264 | 52,465 | [513] |

| 2016 | 9,441 | 5,528 | 16,974 | 23,689 | 55,632 | [514] | |

| 2017 | 8,379 | 4,833 | 18,415 | 23,510 | 55,137 | [515] | |

| 2018 | 9,987 | 4,651 | 20,296 | 24,500 | 59,434 | [516] | |

| 연도 | 스튜디오 엔터테인먼트 | 소비자 및 국제 직접 지원 | 공원, 체험 및 제품 | 미디어[h] 네트워크 | 총 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 10,065 | 3,414 | 24,701 | 21,922 | 59,434 | [517] |

| 2019 | 11,127 | 9,349 | 26,225 | 24,827 | 69,570 | [518] |

| 2020 | 9,636 | 16,967 | 16,502 | 28,393 | 65,388 | [519] |

| 연도 | 미디어 및 엔터테인먼트 배포 | 공원, 체험 및 제품 | 총 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 50,866 | 16,552 | 67,418 | [520] |

| 2022 | 55,040 | 28,705 | 83,745 | [521] |

영업 수입

| 연도 | 스튜디오 엔터테인먼트[e] | 디즈니 컨슈머 제품[f] | 디즈니 인터랙티브[493] 미디어 | 공원 및 리조트[g] | 디즈니 미디어 네트워크[h] | 총 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 318 | 229 | 546 | 1,094 | [495] | ||

| 1992 | 508 | 283 | 644 | 1,435 | [495] | ||

| 1993 | 622 | 355 | 746 | 1,724 | [495] | ||

| 1994 | 779 | 425 | 684 | 77 | 1,965 | [496][497] | |

| 1995 | 998 | 510 | 860 | 76 | 2,445 | [496][497] | |

| 1996 | 1,596[f] | - 300[k] | 990 | 747 | 3,033 | [497] | |

| 1997 | 1,079 | 893 | −56 | 1,136 | 1,699 | 4,312 | [500] |

| 1998 | 769 | 801 | −94 | 1,288 | 1,746 | 4,079 | [500] |

| 1999 | 116 | 607 | −93 | 1,446 | 1,611 | 3,231 | [500] |

| 2000 | 110 | 455 | −402 | 1,620 | 2,298 | 4,081 | [501] |

| 2001 | 260 | 401 | 1,586 | 1,758 | 4,214 | [502] | |

| 2002 | 273 | 394 | 1,169 | 986 | 2,826 | [502] | |

| 2003 | 620 | 384 | 957 | 1,213 | 3,174 | [503] | |

| 2004 | 662 | 534 | 1,123 | 2 169 | 4,488 | [503] | |

| 2005 | 207 | 543 | 1,178 | 3,209 | 5,137 | [504] | |

| 2006 | 729 | 618 | 1,534 | 3,610 | 6,491 | [504] | |

| 2007 | 1,201 | 631 | 1,710 | 4,285 | 7,827 | [505] | |

| 2008 | 1,086 | 778 | −258 | 1,897 | 4,942 | 8,445 | [506] |

| 2009 | 175 | 609 | −295 | 1,418 | 4,765 | 6,672 | [507] |

| 2010 | 693 | 677 | −234 | 1,318 | 5,132 | 7,586 | [508] |

| 2011 | 618 | 816 | −308 | 1,553 | 6,146 | 8,825 | [509] |

| 2012 | 722 | 937 | −216 | 1,902 | 6,619 | 9,964 | [510] |

| 2013 | 661 | 1,112 | −87 | 2,220 | 6,818 | 10,724 | [511] |

| 2014 | 1,549 | 1,356 | 116 | 2,663 | 7,321 | 13,005 | [512] |

| 2015 | 1,973 | 1,752 | 132 | 3,031 | 7,793 | 14,681 | [513] |

| 2016 | 2,703 | 1,965 | 3,298 | 7,755 | 15,721 | [514] | |

| 2017 | 2,355 | 1,744 | 3,774 | 6,902 | 14,775 | [515] | |

| 2018 | 2,980 | 1,632 | 4,469 | 6,625 | 15,706 | [516] | |

| 연도 | 스튜디오 엔터테인먼트 | 소비자 및 국제 직접 지원 | 공원, 체험 및 제품 | 디즈니 미디어 네트워크 | 총 | 원천 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 3,004 | −738 | 6,095 | 7,338 | 15,689 | [517] | |

| 2019 | 2,686 | −1,814 | 6,758 | 7,479 | 14,868 | [518] | |

| 2020 | 2,501 | −2,806 | −81 | 9,022 | 8,108 | [519] | |

| 연도 | 미디어 및 엔터테인먼트 배포 | 공원, 체험 및 제품 | 총 | 원천 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 7,295 | 471 | 7,766 | [520] |

| 2022 | 4,216 | 7,905 | 12,121 | [521] |

필름 라이브러리

최고 흥행 영화

| 순위 | 제목 | 연도 | 흥행 총액 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 어벤져스: 엔드게임 | 2019 | $2,797,800,564 |

| 2 | 스타워즈:깨어난 포스 | 2015 | $2,064,615,817 |

| 3 | 어벤져스:인피니티 워 | 2018 | $2,048,359,754 |

| 4 | 라이온킹 | 2019 | $1,654,367,425 |

| 5 | 어벤져스 | 2012 | $1,515,100,211 |

| 6 | 프로즌 II | 2019 | $1,445,182,280 |

| 7 | 어벤져스:울트론 시대 | 2015 | $1,395,316,979 |

| 8 | 흑표범 | 2018 | $1,336,494,321 |

| 9 | 스타워즈:라스트 제다이 | 2017 | $1,331,635,141 |

| 10 | 미녀와 야수 | 2017 | $1,273,109,220 |

| 11 | 언 | 2013 | $1,265,596,785 |

| 12 | 인크레더블 2 | 2018 | $1,242,805,359 |

| 13 | 아이언맨 3 | 2013 | $1,215,392,272 |

| 14 | 캡틴 아메리카:남북 전쟁 | 2016 | $1,151,918,521 |

| 15 | 캡틴 마블 | 2019 | $1,129,727,388 |

| 16 | 토이스토리 4 | 2019 | $1,073,080,329 |

| 17 | 스타워즈:스카이워커의 부활 | 2019 | $1,072,848,487 |

| 18 | 토이스토리 3 | 2010 | $1,068,879,522 |

| 19 | 캐리비안의 해적:망자의 상자 | 2006 | $1,066,179,725 |

| 20 | 로그 원: 스타워즈 스토리 | 2016 | $1,055,135,598 |

| 21 | 알라딘 | 2019 | $1,046,649,706 |

| 22 | 캐리비안의 해적:낯선 조류에 대하여 | 2011 | $1,045,713,802 |

| 23 | 이상한 나라의 앨리스 | 2010 | $1,025,491,110 |

| 24 | 도리를 찾아서 | 2016 | $1,025,006,125 |

| 25 | 주토피아 | 2016 | $1,004,629,935 |

| 순위 | 제목 | 연도 | 흥행 총액 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 프로즌 II | 2019 | $1,445,182,280 |

| 2 | 언 | 2013 | $1,265,596,785 |

| 3 | 인크레더블 2 | 2018 | $1,242,805,359 |

| 4 | 토이스토리 4 | 2019 | $1,073,080,329 |

| 5 | 토이스토리 3 | 2010 | $1,068,879,522 |

| 6 | 도리를 찾아서 | 2016 | $1,025,006,125 |

| 7 | 주토피아 | 2016 | $1,004,629,935 |

| 8 | 라이온킹 | 1994 | $986,214,868 |

| 9 | 니모를 찾아서 | 2003 | $936,094,852 |

| 10 | Inside Out(Inside Out) | 2015 | $852,830,107 |

| 11 | 코코 | 2017 | $797,666,425 |

| 12 | 몬스터 대학교 | 2013 | $743,455,810 |

| 13 | 업. | 2009 | $731,463,377 |

| 14 | 빅 히어로 6 | 2014 | $649,657,407 |

| 15 | 모아나 | 2016 | $634,965,560 |

| 16 | 인크레더블 | 2004 | $631,441,092 |

| 17 | 라따뚜이 | 2007 | $626,549,695 |

| 18 | 엉키다 | 2010 | $584,899,819 |

| 19 | 몬스터즈 주식회사 | 2001 | $560,483,719 |

| 20 | 카2 | 2011 | $560,155,383 |

| 21 | 용감한. | 2012 | $554,606,532 |

| 22 | 벽면-E | 2008 | $532,508,025 |

| 23 | 인터넷을 파괴한 랄프 | 2018 | $529,290,830 |

| 24 | 토이스토리2 | 1999 | $511,358,276 |

| 25 | 알라딘 | 1992 | $504,050,219 |

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 디즈니의 영화 목록

- 디즈니의 텔레비전 시리즈 목록

- 디즈니 대학교

- 디즈니페이션

- 부에나 비스타

- 맨더빌-앤서니 대 월트디즈니사, 맨더빌이 자동차 제작으로 자신의 저작권이 있는 아이디어를 침해했다고 주장한 연방법원 소송입니다.

- 대기업 목록

- 디즈니의 인수 목록

레퍼런스

메모들

- ^ "WED"는 월터 엘리아스 디즈니의 머리글자에서 따왔다.

- ^ 비록 7월 17일이 다음 날 공개 개장 전에 미리 공개될 예정이었지만, 디즈니랜드는 7월 17일을 공식 [98]개장일로 사용하고 있다.

- ^ 그의 공식 직함은 co였다.부회장

- ^ 그래미상 레퍼런스 목록:

- ^ a b Films and Film Entertainment로도 선정됨

- ^ a b c d 1996년 크리에이티브 콘텐츠로 통합, 2016년 컨슈머 프로덕트 및 인터랙티브 미디어로 통합, 2018년 파크&리조트와 통합

- ^ a b 월트 디즈니 어트랙션(1989–2000), 월트 디즈니 파크 앤 리조트(2000–2005), 디즈니 데스티네이션(2005–2008), 월트 디즈니 파크 앤 리조트 월드와이드(2008–2018)라고 불립니다.

- ^ a b c 1994년부터 1996년까지 방송

- ^ 캐피털시티/ABC Inc. 인수 후

- ^ a b Marvel Entertainment의 성과로 첫해

- ^ 디즈니사는 WDIG와 연계하지 않고 부동산에 관한 재무변경으로 3억달러의 손실을 보고했습니다.

인용문

- ^ a b "Walt Disney". Fortune. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ "The Walt Disney Company". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Gibson, Kate (June 24, 2022). "Disney among slew of U.S. companies promising to cover abortion travel costs". CBS News. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ "Disney English Definition and Meaning". Lexico. Oxford. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Martin, Mackenzie (May 22, 2021). "Walt Disney Didn't Actually Draw Mickey Mouse. Meet the Kansas City Artist Who Did". NPR. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Carol (April 28, 1985). "Cartoon Producer Recalls Early Days". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Rockefeller 2015, 페이지 3. 오류:: 2015

- ^ Pitcher, Ken (October 1, 2021). "50 years ago: Roy Disney made Walt's dream come true". ClickOrlando. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 42

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 98

- ^ Rockefeller 2015, 페이지 4. 오류:: 2015

- ^ a b "Could Oswald the Lucky Rabbit have been bigger than Mickey?". BBC. December 3, 2022. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (September 5, 2020). "The Incredible True Story of Disney's Oswald the Lucky Rabbit". Collider. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Susanin & Rockefeller 2011, 페이지 182 오류: 없음: 2011 (도움말

- ^ a b c d Suddath, Claire (November 18, 2008). "A Brief History of Mickey Mouse". Time. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Parkel, Inga (July 4, 2022). "Disney could lose Mickey Mouse as 95-year copyright expiry nears". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Davis, Elizabeth (June 25, 2019). "Historically yours: Mickey Mouse is born". Jefferson City News Tribune. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Davis, Amy 2019, 페이지 9. 오류::

- ^ a b Gabler, Neal (September 12, 2015). "Walt Disney, a Visionary Who Was Crazy Like a Mouse". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ Feiling 1967, 187페이지

- ^ Lauren, Baltimore (June 24, 2017). "Rare First Appearance Mickey Mouse Animation Art Up For Auction". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ a b 장벽 2003, 54페이지

- ^ a b c Susanin 2011, 페이지

- ^ 장벽 2007, 75-78페이지

- ^ a b c Kaufman, J.B. (April 1997). "Who's Afraid of ASCAP? Popular Songs in the Silly Symphonies". Animation World Magazine. Vol. 2, no. 1. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 77

- ^ Lynn, Capi (December 23, 2019). "Here's how Salem kids formed the first ever Mickey Mouse Club in the nation in 1929". Statesman Journal. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ Krasniewicz 2010, 페이지 51

- ^ Kaufman & Gerstein 2018, 84-85페이지.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 342

- ^ a b Iyer, Aishwarya (January 18, 2020). "A look back at Mickey Mouse, as the comic strip turns 90". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ Rivkin, Mike (April 3, 2021). "Antiques: The Life and Times of Mickey Mouse". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ Krasniewicz 2010, 페이지 52

- ^ "How Mickey got Disney through the Great Depression". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. April 23, 2020. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Krasniewicz 2010, 55페이지

- ^ Zavaleta, Jonathan (March 20, 2022). "A Brief History of the Mickey Mouse Watch (Plus, the Best Mickey Mouse Watches to Buy)". Spy.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 199-201페이지.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 201, 203

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 89, 136.

- ^ Nye, Doug (December 28, 1993). "In Glorious Color". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Noonan, Kevin (November 4, 2015). "Technicolor's Major Milestones After 100 Years of Innovation". Variety. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Ryan, Desmond (July 24, 1987). "Disney Animator Recalls Gamble That Was Snow White". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Susanin 2011, 페이지

- ^ Lambie, Ryan (February 8, 2019). "Disney's Snow White: The Risk That Changed Filmmaking Forever". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ 윌리엄스, 데니 & 데니 2004, 페이지 116.

- ^ a b 장벽 2007, 페이지 136

- ^ "Top of the box office: The highest-grossing movies of all time". The Daily Telegraph. May 1, 2018. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 271; 장벽 2007, 페이지 131

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 158-60.

- ^ Gabler 2007, 페이지 287. 오류:: 2007

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 152

- ^ a b Martens, Todd (March 31, 2019). "The original Dumbo arguably was Disney's most important blockbuster". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Pinocchio: THR's 1940 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. February 23, 2020. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 151–152.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 309-10.

- ^ Violante, Anthony (November 1, 1991). "Late Bloomer Disney's Fantasia, a Commercial Flop in 1940, Come to Full Flower on Home Video". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Bergan 2011, 페이지 82

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 366, 370

- ^ a b Sito, Tom (July 19, 2005). "The Disney Strike of 1941: How It Changed Animation & Comics". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 171

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 161, 180

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 370-71

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 372

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 374

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 380

- ^ a b c d Allison, Austin (October 14, 2021). "How Disney Animation's Most Forgotten Era Saved the Studio During WWII". Collider. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 381–82; 장벽 2007, 페이지 182.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 383

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 184

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 180

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 187-88

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 432-33

- ^ a b Lattanzio, Ryan (March 29, 2022). "Song of the South: 12 Things to Know About Disney's Most Controversial Movie". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (February 3, 2017). "A Rare Trip Inside Disney's Secret Animation Vault". Vulture. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Larsen, Peter (December 5, 2006). "New life for Disney's True-Life Adventures". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 208

- ^ Hollis & Ehrbar 2006, 7-8페이지

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 221

- ^ 장벽 2007, 223-25페이지.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 228; 가블러 2008, 페이지 503.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 230페이지, 가블러 2008, 487페이지

- ^ a b 가블러 2008, 페이지 488-89.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 225

- ^ Tremaine, Julie (October 13, 2020). "The story behind the California attraction that inspired Disneyland". San Francisco Gate. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 191; 가블러 2008.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 236

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 294; 가블러 2008, 페이지 534.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 235쪽, 가블러 2008, 495쪽

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 500-01.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 240페이지; 가블러 2008, 498-99페이지, 524.

- ^ Reynolds, Christopher (July 10, 2015). "Disneyland: How Main Street, U.S.A. is rooted in Walt Disney's Missouri childhood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 498-99

- ^ a b Martin, Garrett (October 13, 2021). "A Guide to Disney World's Opening Day Attractions". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Walsh, Kathryn (March 16, 2018). "The Different Castles Around Disneyland Theme Parks". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 499

- ^ Bemis, Bethanee (January 3, 2017). "How Disney Came to Define What Constitutes the American Experience". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ "Disneyland Opening Day, 1955". The Hollywood Reporter. July 17, 2015. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Happy birthday, Disneyland! Iconic park celebrates 66th anniversary today". ABC7. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 491

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 262-63.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 241, 262–63.

- ^ Williams, Owen (August 7, 2014). "Film Studies 101: Ten Movie Formats That Shook the World". Empire. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ 2001년 제철소, 페이지 110

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 242-45, 248.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 511

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 245

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 520-21.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 522

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 514

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 514-15.

- ^ King, Jonathan (February 27, 1995). "The Crockett Craze : It's been 40 years since Fess Parker had us running around in coonskin caps. But the values his show inspired live on". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ 뉴콤 2000, 페이지 24

- ^ "Opening Day at Disneyland, July 17, 1955". The Denver Post. Associated Press. June 26, 2006. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ MacDonald, Brady (July 10, 2015). "Disneyland got off to a nightmare start in 1955, but 'Walt's Folly' quickly won over fans". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Dowd, Katie (July 15, 2020). "'Black Sunday': Remembering Disneyland's disastrous opening day on its 66th anniversary". San Francisco Gate. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 537

- ^ 브라운 2022, 페이지 573

- ^ a b 가블러 2008 페이지 585

- ^ 장벽 1999, 페이지 559. 오류:: CITREF 1999

- ^ Zad, Martle (April 12, 1992). "101 Dalmatians, 6,469,952 Spots on Home Video". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ 가블러 2008, 페이지 563

- ^ Lyons, Mike (April 1, 2000). "Sibling Songs: Richard & Robert Sherman and Their Disney Tunes". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Posner, Michael (August 19, 2009). "Disney songwriters' family feud". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 268

- ^ Folkart, Burt (November 6, 1991). "Movie and TV actor Fred MacMurray dies: Entertainer: He played comedic and dramatic roles during a career that began when he was 5". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp, Cari (March 18, 2022). "Hayley Mills Finally Gets Her Oscar!". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Perez, Lexy (September 7, 2021). "Hayley Mills Reflects on Early Career, Walt Disney, Turning Down Lolita Role and More in Memoir". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Bergan, Ronald (October 12, 2015). "Kevin Corcoran obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Higgens, Bill (December 10, 2018). "Hollywood Flashback: Mary Poppins Success Helped Walt Create Disney World in 1964". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Patton, Charlie (January 20, 2013). "Oscar-winning composer talks the making of Mary Poppins". The Florida Times-Union. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Bergan, Ronald (September 4, 2015). "Dean Jones obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Puente, Maria (September 2, 2015). "Disney star Dean Jones dies". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Russian, Ale (July 10, 2017). "Kurt Russell Reflects on Mentor Walt Disney: I Learned 'How to Make Movies' from Him". People. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Zad, Martie (August 6, 2000). "Young Kurt Russell's Family Flicks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 301

- ^ 장벽 2007, 302–03페이지; 가블러 2008, 606–08페이지.

- ^ Harrison, Scott (April 30, 2017). "From the Archives: Walt and the pirates". Los Angeles TImes. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 306–07; 가블러 2008, 페이지 629.

- ^ 장벽 2007, 페이지 307

- ^ Mikkelson, David (October 19, 1995). "Was Walt Disney Frozen?". Snopes. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Gabler 208, 페이지 626–31. 오류:: (

- ^ 2001년 제철소, 페이지 51; 그리핀 2000, 페이지 101

- ^ a b Spiegel, Josh (January 11, 2021). "A Crash Course in the History of Disney Animation Through Disney+". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (March 26, 2016). "Waking Sleeping Beauty documentary takes animated look at Disney renaissance". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Lambie, Ryan (June 26, 2019). "Exploring Disney's Fascinating Dark Phase of the 70s and 80s". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Sito, Tom (November 1, 1998). "Disney's The Fox and the Hound: The Coming of the Next Generation". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Dave, Kehr (April 13, 1987). "Aristocats Lacks Subtle Disney Hand". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Long, Rebecca (August 8, 2021). "The Anti-Fascist Bedknobs and Broomsticks Deserves Its Golden Jubilee". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Radulovic, Petrana (February 27, 2020). "Your complete guide to what the heck the Disney CEO change is and why you should care". Polygon. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Roy O. Disney, Aide of Cartoonist Brother, Dies at 78". The New York Times. December 22, 1971. p. 39. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Eades, Mark (December 22, 2016). "Remembering Roy O. Disney, Walt Disney's brother, 45 years after his death". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Levenson, Eric; Gallagher, Dianna (April 21, 2022). "Why Disney has its own government in Florida and what happens if that goes away". CNN. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Patches, Matt (May 20, 2015). "Inside Walt Disney's Ambitious, Failed Plan to Build the City of Tomorrow". Esquire. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "49 years ago, Walt Disney World opened its doors in Florida". Fox 13 Tampa Bay. October 1, 2021. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (September 29, 2021). "Disney World Opened 50 Years Ago; These Workers Never Left". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Greg, Allen (October 1, 2021). "50 years ago, Disney World opened its doors and welcomed guests to its Magic Kingdom". NPR. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Donn B. Tatum". Variety. June 3, 1993. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "E. Cardon 'Card' Walker". Variety. November 30, 2005. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Empire Is Hardly Mickey Mouse". The New York Times. July 18, 1973. p. 30. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Disney's Dandy Detailed Data; Robin Hood Takes $27,500,000; Films Corporate Gravy-Maker". Variety. January 15, 1975. p. 3.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (August 24, 1972). "Spirited Romp for Invisible Caper Crew". The New York Times. p. 0. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Herbie Rides Again". Variety. December 31, 1973. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo". Variety. December 31, 1977. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (July 3, 1975). "Screen: Witch Mountain: Disney Fantasy Shares Bill with Cinderella". The New York Times. p. 0. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Eder, Richard (January 29, 1977). "Disney Film Forces Fun Harmlessly". The New York Times. p. 11. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (November 3, 1999). "Nephew Is Disney's Last Disney". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ King, Susan (June 22, 2015). "Disney's animated classic The Rescuers marks 35th anniversary". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ 루카스 2019, 페이지 89

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1978". Variety. January 3, 1979. p. 17.

- ^ Kit, Borys (December 1, 2009). "Tron: Legacy team mount a Black Hole remake". Reuters. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Weiner, David (December 13, 2019). ""We Never Had an Ending:" How Disney's Black Hole Tried to Match Star Wars". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (September 20, 1979). "11 Animators Quit Disney, Form Studio". The New York Times. p. 14. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Poletick, Rachel (February 2, 2022). "Don Bluth Entertainment: How One Animator Inspired a Disney Exodus". Collider. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ 루카스 2019, 페이지 153

- ^ "World on Ice Show Opens July 14 in Meadowlands". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 28, 1981. p. 48. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Sherman, Natalie (April 7, 2014). "Howard site is a key player for shows like Disney on Ice and Monster Jam". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (January 9, 1990). "Mermaid Swims to Animation Record". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Hayes (October 2, 1982). "Fanfare as Disney Opens Park". The New York Times. p. 33. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Wynne, Sharron Kennedy (September 27, 2021). "For Disney World's 50th anniversary, a look back at the Mouse that changed Florida". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "On This Day: Epcot opened at Walt Disney World in 1982". Fox 35 Orlando. October 1, 2021. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ King, Susan (January 7, 2017). "Tron at 35: Star Jeff Bridges, Creators Detail the Uphill Battle of Making the CGI Classic". Variety. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (February 16, 1984). "Touchstone Label to Replace Disney Name on Some Films". The New York Times. p. 19. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Shoji, Kaori (April 12, 2013). "Tokyo Disneyland turns 30!". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Shapiro, Margaret (December 16, 1989). "Unlikely Tokyo Bay Site Is a Holiday Hit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Bedell, Sally (April 12, 1983). "Disney Channel to Start Next Week". The New York Times. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Steve, Knoll (April 29, 1984). "The Disney Channel Has an Expensive First Year". The New York Times. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Raymond Watson, former Disney chairman, dies". Variety. October 22, 2012. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Bartlett, Rhett (February 10, 2019). "Ron Miller, Former President and CEO of The Walt Disney Co., Dies at 85". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Disney makes big splash at box office". UPI. March 12, 1984. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (March 13, 2021). "Hollywood Flashback: Down and Out in Beverly Hills Mocked the Rich in 1986". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Chapman, Glenn (March 29, 2011). "Looking back at Adventures in Babysitting". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Sanello, Frank (June 11, 1984). "Walt Disney Productions ended financier Saul Steinberg's takeover attempt..." UPI. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas (June 12, 1984). "Steinberg Sells Stake to Disney". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas (September 24, 1984). "New Disney Team's Strategy". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Aljean, Harmentz (December 29, 1985). "The Man Re-animating Disney". The New York Times. p. 13. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (May 20, 2020). "The Disney Renaissance Didn't Happen Because of Jeffrey Katzenberg; It Happened in Spite of Him". Collider. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Kois, Dan (October 19, 2010). "The Black Cauldron". Slate. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "Breifly: E. F. Hutton raised $300 million for Disney". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 1987. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b "Disney, Japan Investors Join in Partnership : Movies: Group will become main source of finance for all live-action films at the company's three studios". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. October 23, 1990. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Change". The New York Times. January 4, 1986. p. 33. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (November 21, 2019). "The Sherlockian Brilliance of The Great Mouse Detective". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.