틱톡

TikTok | |

| 개발자 | 바이트댄스 |

|---|---|

| 초도출시 | 2016년 9월,~09년 (중국 및 인도만 해당) |

| 운영체제 | |

| 선대 | musical.ly |

| 사용 가능한 위치 | 40개[1] 국어 |

| 유형 | 비디오 공유 |

| 면허증. | 사용 조건이 포함된 독점 소프트웨어 |

| 웹사이트 | tiktok |

| |||||||||

| 개발자 | 북경마이크로라이브비전기술유한공사 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 초도출시 | 2016년 9월 20일, | ||||||||

| 안정적 해제 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| 운영체제 | |||||||||

| 사용 가능한 위치 | 간체 중국어, 영어[2] | ||||||||

| 유형 | 비디오 공유 | ||||||||

| 면허증. | 계약이 있는 독점 소프트웨어 | ||||||||

| 웹사이트 | douyin | ||||||||

| 도우인 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 중국인 | 抖音 | ||||||||||||||

| 문자적 의미 | "진동하는 소리" | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

중국 본토의 상대는 더우인(중국어: 抖音, pinyin: ǒ우이 ī은 중국 인터넷 기업 바이트댄스가 소유한 숏폼 비디오 호스팅 서비스입니다. 사용자가 제출한 동영상을 호스팅하며, 지속 시간은 3초에서 10분까지입니다.[4]

TikTok은 출시 이후 콘텐츠 제작자와 새로운 오디언스를 연결하는 데 있어 대체 앱보다 더 나은 추천 알고리즘을 사용하여 세계에서 가장 인기 있는 플랫폼 중 하나가 되었습니다.[5] 2020년 4월, 틱톡은 전 세계적으로 20억 건의 모바일 다운로드를 돌파했습니다.[6] 클라우드플레어는 TikTok을 2021년 가장 인기 있는 웹사이트로 선정하여 Google을 앞질렀습니다.[7] 틱톡의 인기는 음식과 음악의 바이럴 트렌드가 도약하고 플랫폼의 문화적 영향력을 전 세계적으로 높일 수 있게 해주었습니다.[8]

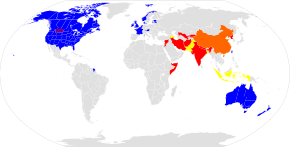

틱톡은 데이터 개인 정보 침해, 정신 건강 문제, 잘못된 정보, 공격적인 콘텐츠 및 이스라엘-하마스 전쟁 중 그 역할로 인해 정밀 조사를 받았습니다.[9] 국가들은 바이트댄스를 통해 중국 정부의 사용자 데이터 수집 가능성에 대한 국가 안보 우려로 어린이를 보호하기 위해 틱톡에 벌금을 부과하거나 금지 또는 제한을 시도했습니다.[9][10]

기업구조

TikTok Ltd는 Cayman 제도에 통합되었으며 싱가포르와 로스앤젤레스에 기반을 두고 있습니다.[11] 이 회사는 각각 미국, 호주(뉴질랜드 사업도 운영), 영국(유럽 연합의 자회사도 소유), 싱가포르(동남아시아와 인도에 사업을 소유)에 기반을 둔 4개의 기업을 소유하고 있습니다.[12][13]

베이징에 본사를 둔 ByteDance는 설립자와 중국 투자자, 기타 글로벌 투자자 및 직원이 소유하고 있습니다.[14] ByteDance의 주요 국내 자회사 중 하나는 1% 황금 지분을 통해 중국 국영 펀드 및 기업이 소유하고 있습니다.[15][16][17] TikTok과 ByteDance 사이에 인사 및 제품 개발 측면에서 중복이 존재한다고 직원들이 보고했습니다.[18][19][20] 틱톡은 2020년부터 미국에 본사를 둔 최고경영자(CEO)가 중요한 결정을 내릴 책임이 있으며 중국과의 연결을 축소했다고 밝혔습니다.[20]

역사

도우인

2016년 9월에 바이트댄스(ByteDance)에 의해 출시되었으며, 원래는 A.me 라는 이름이었다가 2016년 12월에 抖音(Douyin)로 리브랜딩되었습니다. Douyin은 200일 만에 개발되었으며 1년 만에 1억 명의 사용자를 확보했으며 매일 10억 개 이상의 비디오가 시청되었습니다.[23][24]

TikTok과 Douyin은 유사한 사용자 인터페이스를 공유하지만 플랫폼은 별도로 운영됩니다.[25][3][26] Douyin에는 구매, 호텔 예약, 지리 태그 리뷰 작성과 같은 다른 기능과 함께 사람들의 얼굴로 더 많은 비디오를 검색할 수 있는 비디오 검색 기능이 포함되어 있습니다.[27]

틱톡

Byte Dance는 Douyin의 해외 진출을 계획했습니다. 바이트댄스의 설립자인 장이밍(Jang Yiming)은 "중국은 전 세계 인터넷 사용자의 5분의 1만 거주하고 있습니다. 우리가 세계적인 규모로 확장하지 않는다면, 우리는 5분의 4를 주시하는 동료들에게 질 수밖에 없습니다. 따라서 세계화는 필수입니다."[28]

ByteDance는 TikTok을 Douyin의 글로벌 버전으로 만들었습니다. 틱톡은 2017년 9월에 국제 시장에 출시되었습니다.[29] 2017년 11월 9일, 바이트댄스는 거의 10억 달러를 들여 캘리포니아 산타모니카에 해외 지사를 두고 상하이에 본사를 둔 스타트업 Musical.ly 을 인수했습니다. Musical.ly 는 사용자가 짧은 립싱크 및 코미디 비디오를 만들 수 있도록 하는 소셜 미디어 비디오 플랫폼으로 2014년 8월에 처음 출시되었습니다. 틱톡은 2018년 8월 2일 기존 계정과 데이터가 하나의 앱으로 통합되어 틱톡이라는 이름을 유지하면서 Musical.ly 과 합병되었습니다.

2018년 1월 23일, 틱톡 앱은 태국 및 기타 국가의 앱 스토어에서 무료 애플리케이션 다운로드 중 1위를 차지했습니다.[35] 모바일 리서치 회사 센서타워의 데이터에 따르면 틱톡은 미국에서 1억 3천만 번 이상 다운로드되었으며 전 세계적으로 20억 건의 다운로드를 기록했습니다(이 숫자들은 중국의 안드로이드 사용자들을 제외한 것입니다).[36][37]

미국에서는 지미 팰런(Jimmy Fallon)과 토니 호크(Tony Hawk)를 포함한 유명 인사들이 2018년부터 이 앱을 사용하기 시작했습니다.[38][39] 제니퍼 로페즈, 제시카 알바, 윌 스미스, 저스틴 비버 등 다른 연예인들도 틱톡에 합류했습니다.[40] 2019년 1월 TikTok은 크리에이터가 자신의 비디오에 상품 판매 링크를 포함할 수 있도록 허용했습니다.[41]

2019년 9월 3일 틱톡과 미국 내셔널 풋볼 리그(NFL)는 다년간의 파트너십을 발표했습니다.[42] 이번 합의는 NFL의 100번째 시즌이 시작되기 불과 이틀 전에 이루어졌으며, 이 날 TikTok은 계약을 기념하여 팬들을 위한 활동을 주최했습니다. 이번 파트너십은 NFL 틱톡 공식 계정의 출시를 수반하며, 이는 후원 영상 및 해시태그 챌린지와 같은 새로운 마케팅 기회를 창출하기 위한 것입니다. 2020년 7월, Douyin을 제외한 TikTok은 존재한 지 4년이 채 되지 않아 전 세계적으로 8억 명에 가까운 월간 활성 사용자를 보고했습니다.[43]

2021년 5월, TikTok은 Kevin A의 사임에 따라 임시 CEO Vanessa Pappas의 자리를 맡은 Shou Zi Chew를 새로운 CEO로[44] 임명했습니다. 2020년 8월 27일 메이어.[45][46][47] 2021년 9월, 틱톡은 10억 명의 사용자를 달성했다고 보고했습니다.[48] 2021년 틱톡은 40억 달러의 광고 수익을 올렸습니다.[49]

2022년 10월, 틱톡은 영국에서 틱톡샵을 출시한 후 미국에서 전자상거래 시장으로 확장할 계획을 세우고 있는 것으로 알려졌습니다. 이 회사는 미국에 있는 일련의 주문 처리 센터의 직원들을 위한 구인 목록을 게시했으며 연말 전에 새로운 라이브 쇼핑 사업을 시작할 계획인 것으로 알려졌습니다.[50] 파이낸셜 타임즈는 틱이Tok은 비디오 게임 채널을 시작할 예정이지만, 이 보고서는 Digiday에 보낸 성명에서 거부되었으며, 대신 TikTok은 게임 커뮤니티의 소셜 허브를 목표로 하고 있습니다.[51][52]

앱 분석 그룹 센서 타워의 데이터에 따르면 2023년 3월 미국 틱톡 광고는 11% 성장했으며 펩시, 도어대시, 아마존, 애플 등이 최고 소비자로 꼽혔습니다. 리서치 그룹 인사이더 인텔리전스의 추정에 따르면 틱톡은 2022년 98억 9천만 달러에서 2023년 141억 5천만 달러의 매출을 올릴 것으로 예상됩니다.[53] 2024년 3월, 월스트리트 저널은 미국에서 틱톡의 성장이 정체되었다고 보도했습니다.[54]

적어도 2020년부터 미국 내 틱톡을 금지하라는 요구에 따라 미국 외국인투자위원회(CFIUS)는 2017년 틱톡의 Musical.ly 합병을 조사해 왔지만 프로젝트 텍사스 제안과 같은 틱톡과의 협상을 마무리하지 못하고 대신 의회의 조치를 기다리고 있습니다.

기타 시장에서의 확장

센서타워가 CNBC에 제공한 자료에 따르면 틱톡은 2018년 상반기 동안 애플 앱스토어에서 1억 400만 건 이상 다운로드되었습니다.[56]

8월에 musical.ly 과 합병한 후 다운로드가 증가했고 TikTok은 2018년 10월에 미국에서 가장 많이 다운로드 된 앱이 되었는데, 이 앱은 musical.ly 이 이전에 한 번 있었습니다. 2019년 2월 틱톡은 더우인과 함께 중국 내 안드로이드 설치를 제외한 전 세계적으로 10억 건의 다운로드를 기록했습니다.[58] 2019년 언론 매체들은 틱톡을 2010년부터 2019년까지 10년 동안 가장 많이 다운로드된 모바일 앱 7위로 꼽았습니다.[59] 2018년과 2019년 애플 앱스토어에서 페이스북, 유튜브, 인스타그램을 제치고 가장 많이 다운로드된 앱이기도 했습니다.[60][61] 2020년 9월, ByteDance와 Oracle 간에 클라우드 호스팅을 제공하기 위한 파트너 역할을 수행하는 계약이 확정되었습니다.[62][63] 2020년 11월, 틱톡은 소니 뮤직과 라이선스 계약을 체결했습니다.[64] 2020년 12월, 워너 뮤직 그룹은 틱톡과 라이선스 계약을 체결했습니다.[65][66]

짧은 비디오 클립의 광고 수익은 다른 소셜 미디어보다 낮습니다. 사용자가 더 많은 시간을 소비하는 반면, 미국 시청자는 시간당 0.31달러, 페이스북의 3분의 1, 인스타그램의 5분의 1, 인스타그램은 연간 67달러, 인스타그램은 200달러 이상의 수익을 올릴 것입니다.[67]

2023년 7월 이란 메흐르 통신은 "더우인의 전문가들"이 이란의 중국 수출을 가능하게 하기 위해 테헤란에서 이란 기업을 만날 것이라고 보도했습니다.[68]

2023년에는 여러 고위급 임원이 바이트댄스에서 틱톡으로 자리를 옮겨 돈벌이 작업에 집중했습니다. 일부는 베이징에서 미국으로 이주했습니다. 월스트리트저널 소식통에 따르면 이번 인사는 일부 틱톡 직원들의 우려로 이어졌으며 테드 크루즈 미국 상원의원의 사무실에 보고돼 추가 조사를 받고 있습니다.[69][70] 틱톡은 2023년 12월 고토의 인도네시아 전자상거래 사업인 토코피디아에 15억 달러를 투자했습니다.[71] 2024년 3월, The Information은 틱톡이 연간 수십억 달러의 손실을 입는 것은 투자자들 사이에서 공공연한 비밀이라고 보도했습니다.[72]

타 플랫폼과의 경쟁

사용자 기반의 규모는 페이스북, 인스타그램, 유튜브에 미치지 못하지만 틱톡은 그 어느 것보다 빠르게 월간 활성 사용자 10억 명을 달성했습니다.[73] TikTok의 경쟁으로 인해 페이스북이 소유한 인스타그램은 2022년 기준 1억 2천만 달러를 지출하여 더 많은 콘텐츠 제작자를 릴스 서비스로 유인했지만 참여 수준은 여전히 낮았습니다.[74] 스냅챗은 2021년에도 크리에이터들에게 2억 5천만 달러를 지급했습니다.[75] 유튜브 쇼츠(YouTube Shorts)를 포함한 많은 플랫폼과 서비스가 틱톡(TikTok)의 형식과 추천 페이지를 모방하기 시작했습니다. 이러한 변화는 인스타그램, 스포티파이 및 트위터 사용자들의 반발을 불러일으켰습니다.[73]

2022년 3월, 워싱턴 포스트는 페이스북의 소유주인 메타 플랫폼이 미국 공화당 지지자들의 지지를 받는 컨설팅 회사인 타겟 빅토리에 틱톡에 대한 로비와 미디어 캠페인을 조정하고 "미국 어린이와 사회에 대한 위험"으로 묘사하기 위해 돈을 지불했다고 보도했습니다. 현지 기자들에게 반 틱의 '백 채널' 역할을 해줄 것을 요청하는 등의 노력이 포함됐습니다.Tok 메시지, 의견 기사 작성 및 편집자에게 보내는 편지, 우려하는 부모의 이름으로 작성된 것을 포함하여 실제로 페이스북에서 시작된 "악의적인 클릭"과 "교사를 때려라"와 같은 틱톡 트렌드에 대한 이야기를 증폭시키고 페이스북 자체의 기업 이니셔티브를 홍보합니다. 메타와의 관계는 다른 관련자들에게 공개되지 않았습니다. Targeted Victory는 "작품이 자랑스럽다"고 말했습니다. 메타 대변인은 틱톡을 포함한 모든 플랫폼이 정밀 조사를 받아야 한다고 말했습니다.[76]

월스트리트저널은 실리콘밸리 경영진이 2023년 3월 틱톡 최고경영자(CEO)의 의회 청문회에 앞서 미국 의원들과 만나 '반중 동맹'을 구축했다고 보도했습니다.[77][78]

특징들

모바일 앱을 사용하면 짧은 동영상을 만들 수 있는데, 이 동영상은 종종 음악을 배경으로 하며 속도를 높이거나, 속도를 늦추거나, 필터로 편집할 수 있습니다.[79] 배경 음악 위에 자신만의 사운드를 추가할 수도 있습니다. 앱으로 뮤직비디오를 만들려면 사용자는 매우 다양한 음악 장르의 배경 음악을 선택하고 필터로 편집한 후 속도 조절과 함께 15초 분량의 비디오를 녹화한 후 틱톡이나 다른 소셜 플랫폼에서 다른 사람들과 공유할 수 있습니다.[80]

틱톡의 "For You" 페이지는 앱에서의 활동을 기반으로 사용자에게 추천하는 비디오 피드입니다. 콘텐츠는 사용자가 좋아하거나 상호 작용하거나 검색한 콘텐츠에 따라 틱톡의 인공지능에 의해 큐레이팅됩니다. 이는 사용자 간의 상호 작용과 관계를 기반으로 하는 다른 소셜 네트워크와 달리 사용자가 새로운 콘텐츠를 찾고 창작자가 새로운 청중에게 도달하는 데 도움이 됩니다.[81][5]

2020년 뉴욕 타임즈가 사용자 경험과 소셜 상호 작용을 형성하는 데 가장 진보된 알고리즘 중 하나로 인정한 틱톡의 알고리즘은 전통적인 소셜 미디어에서 눈에 띕니다.[82] 일반적인 플랫폼은 좋아요, 클릭 또는 팔로우와 같은 적극적인 사용자 행동에 초점을 맞추지만 틱톡은 비디오 시청 중에 더 광범위한 행동을 모니터링합니다. 그런 다음 이 포괄적인 관찰은 2020년 와이어드에서 언급한 바와 같이 알고리즘을 개선하는 데 사용됩니다.[83] 또한 2021년 월스트리트저널(Wall Street Journal)은 사용자의 선호도와 감정을 이해하는 데 있어 다른 소셜 미디어 플랫폼보다 우수성을 강조했습니다. 틱톡의 알고리즘은 이 통찰력을 활용하여 유사한 콘텐츠를 제시하여 사용자가 종종 분리하기 어려운 환경을 만듭니다.[84]

앱의 "리액션" 기능을 통해 사용자는 특정 비디오에 대한 반응을 촬영할 수 있으며, 이 비디오는 화면 주변에서 움직일 수 있는 작은 창에 배치됩니다.[85] "듀엣" 기능을 통해 사용자는 다른 비디오 외에도 비디오를 촬영할 수 있습니다.[86] "duet" 기능은 musical.ly 의 또 다른 상표였습니다. 듀엣 기능은 양측이 개인 정보 보호 설정을 조정하는 경우에만 사용할 수 있습니다.[87]

사용자가 아직 게시하고 싶지 않은 동영상은 "초안"에 저장할 수 있습니다. 사용자는 "초안"을 보고 적합하다고 판단되면 게시할 수 있습니다.[88] 앱을 통해 사용자는 계정을 "비공개"로 설정할 수 있습니다. 앱을 처음 다운로드할 때 기본적으로 사용자의 계정이 공개됩니다. 사용자는 설정에서 비공개로 변경할 수 있습니다. 개인 콘텐츠는 TikTok에서 볼 수 있지만 계정 소유자가 콘텐츠를 볼 수 있는 권한이 없는 TikTok 사용자는 차단됩니다.[89] 사용자는 다른 사용자 또는 "친구"만이 앱을 통해 댓글, 메시지 또는 "반응" 또는 "듀엣" 비디오를 통해 상호 작용할 수 있는지 여부를 선택할 수 있습니다.[85] 또한 사용자는 계정이 비공개인지 여부에 관계없이 특정 비디오를 "공개", "친구 전용" 또는 "비공개"로 설정할 수 있습니다.[89]

사용자는 친구에게 직접 메시지와 함께 동영상, 이모티콘 및 메시지를 보낼 수도 있습니다. 틱톡은 사용자의 댓글을 기반으로 동영상을 만드는 기능도 포함했습니다. 인플루언서는 종종 "라이브" 기능을 사용합니다. 이 기능은 팔로워가 1,000명 이상이고 16세 이상인 사람들에게만 제공됩니다. 18세 이상이면 사용자의 팔로워는 나중에 돈으로 교환할 수 있는 가상 "선물"을 보낼 수 있습니다.[90][91]

틱톡은 2020년 2월 부모가 앱에서 자녀의 존재를 제어할 수 있도록 '가족 안전 모드'를 발표했습니다. 화면 시간 관리 옵션, 제한 모드, 직접 메시지에 제한을 두는 옵션이 있습니다.[92] 이 앱은 2020년 9월 "가족 페어링"이라는 부모 통제 기능을 확장하여 부모와 보호자에게 틱톡의 어린이가 노출되는 것을 이해할 수 있는 교육 리소스를 제공했습니다. 이 기능에 대한 콘텐츠는 온라인 안전 비영리 단체인 인터넷 매터스와 협력하여 만들어졌습니다.[93]

2021년 10월, 틱톡은 사용자가 특정 크리에이터에게 직접 팁을 줄 수 있는 테스트 기능을 출시했습니다. 연령이 많고 팔로워 수가 최소 100,000명이며 조건에 동의하는 사용자의 계정은 프로필에 "팁" 버튼을 활성화할 수 있으며, 이 버튼을 통해 팔로워는 1달러부터 시작하여 얼마든지 팁을 줄 수 있습니다.[94]

2021년 12월, 틱톡은 사용자가 게임을 포함한 컴퓨터에서 열린 응용 프로그램을 방송할 수 있는 스트리밍 소프트웨어인 라이브 스튜디오(Live Studio)의 베타 테스트를 시작했습니다. 이 소프트웨어는 또한 모바일 및 PC 스트리밍을 지원하여 시작되었습니다.[95] 그러나 며칠 후 트위터의 사용자들은 소프트웨어가 오픈 소스인 OBS 스튜디오의 코드를 사용한다는 것을 발견했습니다. OBS는 GNU GPL 버전 2에 따라 TikTok이 OBS의 코드를 사용하려면 Live Studio의 코드를 공개해야 한다고 성명을 발표했습니다.[96]

2022년 5월 틱톡은 광고 수익 공유 프로그램인 틱톡 펄스(TikTok Pulse)를 발표했습니다. '틱톡 전체 동영상 중 상위 4%'를 커버하며 팔로워 수 10만 명 이상의 크리에이터만 이용할 수 있습니다. 자격을 갖춘 제작자의 비디오가 상위 4%에 도달하면 비디오와 함께 표시된 광고에서 수익의 50%를 차지합니다.[97]

2023년 7월, 틱톡은 현재 브라질과 인도네시아에서만 사용할 수 있는 틱톡 뮤직이라는 새로운 스트리밍 서비스를 시작했습니다.[98] 이 서비스는 사용자가 노래를 듣고 다운로드하고 공유할 수 있습니다.[98] 틱톡 뮤직은 유니버설 뮤직 그룹, 소니 뮤직, 워너 뮤직 그룹과 같은 주요 음반 회사의 곡들을 특징으로 하는 것으로 알려졌습니다.[98] 2023년 7월 19일, 틱톡 뮤직은 호주, 멕시코, 싱가포르에서 일부 사용자를 대상으로 확장되었습니다.[99]

유니버설 뮤직 그룹은 틱톡과의 아티스트 지급 및 플랫폼 내 AI 생성 음악 콘텐츠 규제 관련 분쟁에 이어 틱톡과의 라이선스 계약을 갱신하지 않기로 결정하여 2024년 1월 31일 이후 자사 음악을 사용할 수 없게 되었습니다.[100] 이는 최근 TikTok과 자체 라이선스 계약을 갱신한 Warner Music과 달리 주요 플랫폼에서 음악을 철수한 첫 번째 사례입니다.[101]

내용

바이럴 트렌드

이 앱은 전 세계적으로 수많은 바이럴 트렌드, 인터넷 유명인 및 음악 트렌드를 낳았습니다.[102] 사용자가 원본 콘텐츠의 오디오와 함께 기존 비디오에 자신의 비디오를 추가할 수 있는 기능인 듀엣(Duets)은 이러한 많은 트렌드를 촉발시켰습니다.[103] 많은 스타들이 2018년 8월 2일 틱톡과 합병한 musical.ly 에서 시작했습니다. 여기에는 로렌 그레이, 베이비 아리엘, 잭 킹, 리사와 레나, 제이콥 사토리우스, 그리고 다른 많은 사람들이 포함됩니다. 로렌 그레이는 2020년 3월 25일 찰리 다멜리오가 그녀를 추월할 때까지 틱톡에서 가장 많은 팔로워를 가진 사람으로 남아 있었습니다. Gray's는 TikTok 계정 중 최초로 플랫폼에서 4천만 명의 팔로워를 달성했습니다. 그녀는 4,130만 명의 팔로워를 보유하고 있습니다. D'Amelio는 5,000,000,000명의 팔로워를 가진 최초의 사람이었습니다. 찰리 다멜리오(Charli D'Amelio)는 2022년 6월 23일 하비 라메(Khaby Lame)에게 추월당할 때까지 플랫폼에서 가장 많이 팔로우 된 개인으로 남아 있었습니다. 2018년 8월 2일 플랫폼이 musical.ly 와 합병된 후 다른 크리에이터들이 명성을 얻었습니다. TikTok은 또한 릴 나스 엑스의 "Old Town Road"를 2019년 가장 큰 곡 중 하나이자 미국 빌보드 핫 100 역사상 가장 오래 지속된 1위 곡으로 만드는 데 큰 역할을 했습니다.[105][106][107]

틱톡은 많은 음악 아티스트들이 종종 외국 팬들을 포함하여 더 많은 청중을 얻을 수 있도록 해주었습니다. 예를 들어, 아시아 투어를 한 적이 없음에도 불구하고, 밴드 피츠 앤 더 탄트럼스는 2016년 그들의 노래 "Hand Clap"이 플랫폼에서 널리 인기를 끌면서 한국에서 많은 팔로워를 만들었습니다.[108] R&B와 랩 아티스트 지코의 "아무노래"는 사용자들이 노래의 안무에 맞춰 춤을 추는 #아무노래 챌린지의 인기로 한국 음악 차트에서 1위에 올랐습니다.[109] 이 플랫폼은 특히 COVID-19 팬데믹이 발생한 이후 수면자 히트곡에 대한 초기 상업적 성공을 거두지 못한 많은 곡을 출시했습니다.[110][111] 하지만 플랫폼에서 음악이 사용되는 아티스트에게 로열티를 지급하지 않아 비판을 받고 있습니다.[112]

클래식 스타들은 음악가의 첫 데뷔 후 수십 년 만에 태어난 젊은 관객들과 전통적인 장르를 넘나들며 연결할 수 있습니다. 2020년 플리트우드 맥의 "Dreams"는 믹 플리트우드의 스케이팅 비디오와 레크리에이션에 사용되었습니다. 이 노래는 43년 만에 빌보드 핫 100에 재진입했고 애플 뮤직에서 1위를 차지했습니다. 2022년, 케이트 부시의 "Running Up That Hill"은 Stranger Things의 팬들 사이에서 입소문이 났고, 원래 발매된 지 37년 만에 영국 싱글 차트에서 1위를 차지했습니다. 2023년 카일리 미노그의 "빠담빠담"은 많은 청소년 라디오 방송국들이 재생을 거부했음에도 불구하고 Z세대가 공유한 후 라디오 1 재생 목록에 들어갔습니다. TikTok에 강한 참여를 한 다른 나이든 아티스트로는 Elton John과 Rod Stewart가 있습니다.[113]

2020년 6월, 틱톡 사용자들과 케이팝 팬들은 틱톡 통신을 통해 트럼프 대통령의 털사 유세를 위해 "잠재적으로 수십만 장의 티켓을 등록했다고 주장"[114]하며 행사의 "빈 좌석 줄"[115]에 기여했습니다. 이후 2020년 10월에는 당시 대통령 후보였던 조 바이든을 지원하기 위해 틱톡 for Biden이라는 조직이 만들어졌습니다.[116] 선거가 끝난 후 조직명은 변경을 위해 Z세대로 변경되었습니다.[117][118]

2020년 8월 10일, 에밀리 제이콥슨은 픽사의 2007년 컴퓨터 애니메이션 영화 라타투유의 주인공을 찬양하는 노래인 "Ode to Remy"를 작곡하고 불렀습니다. 이 노래는 음악가 Daniel Mertzlufft가 이 노래의 백 트랙을 작곡했을 때 인기를 얻었습니다. 이에 대응하여 Ratatouille the Musical이라는 "크라우드소싱" 프로젝트를 만들기 시작했습니다. 머츠러프트의 영상 이후 의상 디자인, 부가곡, 플레이빌 등 새로운 요소들이 많이 생겨났습니다.[119] 2021년 1월 1일, Ratatouille the Musical의 1시간 전체 가상 프레젠테이션이 TodayTix에서 초연되었습니다. 레미 역에는 티투스 버지스, 장고 역에는 웨인 브래디, 에밀 역에는 애덤 램버트, 귀스토 역에는 케빈 체임벌린, 링귀니 역에는 앤드류 바스 펠드먼, 콜레트 역에는 애슐리 파크, 메이블 역에는 프리실라 로페즈, 스키너 역에는 메리 테스타, 에고 역에는 안드레 드 실즈가 출연했습니다.

"악의적인 핥기"로 알려진 바이러스성 틱톡 트렌드는 학생들이 학교 재산을 파손하거나 훔치고 그 행동의 비디오를 플랫폼에 게시하는 것을 포함합니다. 이러한 추세는 학교의 공공 기물 파손 행위와 그에 따른 일부 학교의 피해 예방 조치로 이어졌습니다. 일부 학생들은 유행에 동참한 혐의로 체포되었습니다.[120][121] 틱톡은 트렌드를 표시하는 콘텐츠에 대한 접근을 차단하고 차단하기 위한 조치를 취했습니다.[122] 또 다른 틱톡 트렌드인 기아 챌린지는 2010년에서 2021년 사이에 사용자들이 당시 표준 기능이었던 고정 장치 없이 제조된 기아와 현대 자동차의 특정 모델을 훔치는 것입니다. 미국 도로교통안전국에 따르면 2023년 2월 현재 최소 14건의 충돌사고와 8명의 사망자가 발생했습니다.[124] 지난 5월 기아와 현대는 2억 달러 규모의 집단소송을 해결하기 위해 피해 차량과 26,000개가 넘는 스티어링 휠 잠금장치에 소프트웨어 업데이트를 제공하기로 합의했습니다.

2023년에는 스트리머가 시청자의 프롬프트에 따라 비디오 게임 캐릭터처럼 행동하는 트렌드가 등장했습니다.[126]

중국판 틱톡 더우인에서는 2019년 8월 기준으로 많은 인기를 얻은 유명인 중에는 딜라바 딜무랏, 안젤라베이비, 뤄즈샹, 오우양 나나, 판창장 등이 있습니다.[127] 2022년 FIFA 월드컵에서 카타르의 에콰도르와의 개막전 패배로 분노한 표정이 기록되면서 카타르 10대 왕족이 인터넷 유명인사가 되었는데,[128] 그는 도우인 계정을 만든 지 일주일도 되지 않아 1,500만 명 이상의 팔로워를 모았습니다.[129]

음식과 조리법

틱톡 음식 트렌드는 소셜 미디어 플랫폼 틱톡의 특정 음식 레시피와 음식 관련 유행입니다.[130] 이 콘텐츠는 코로나19 팬데믹 기간인 2020년에 많은 사람들이 집에서 요리를 하고 식사를 하고 엔터테인먼트를 위해 소셜 미디어로 눈을 돌리면서 인기를 모았습니다.[130] 일부 틱톡 사용자들은 식단과 레시피를 공유하지만, 다른 사용자들은 쉽고 인기 있는 레시피의 단계별 동영상을 통해 틱톡에서 브랜드나 이미지를 확장합니다.[131] 사용자들은 종종 음식과 관련된 콘텐츠를 "푸드톡"이라고 부릅니다.[130]

해시태그 #TikTokFood와 #FoodTok은 음식과 관련된 내용을 식별하는 데 사용되며,[132] 앱이 만들어진 이후 각각 402억 회와 97억 회가 조회되었다고 회사 측은 밝혔습니다. 음식 트렌드는 수백만 명의 시청자에게 깊은 사회적 영향을 미쳤습니다.[131] 청소년 요리, 신체 이미지에 대한 대화, 소셜 미디어에서의 식품 마케팅 사용, 대중 트렌드로 인한 식량 부족 등에서 인기가 높아졌습니다.[133][134][135] 아이탄 버나스(Eitan Bernath), 제론 콤스(Jeron Combs), 에밀리 마리코(Emily Mariko)와 같은 특정 틱톡 콘텐츠 제작자는 음식 트렌드가 된 레시피를 제작하여 명성을 얻었습니다. 그들과 동료들은 남은 연어 그릇, 구운 페타 치즈 파스타, 페스토 계란과 같은 요리법을 개발했습니다.[136][137][138]패션과 바디사이즈

많은 크리에이터들이 자신에게 잘 맞는 옷 사이즈를 찾지 못하는 것에 대해 공개한 후 "미드사이즈" 패션은 틱톡에서 더 큰 노출을 얻었습니다. 여성복은 크게 쁘띠, 스트레이트, 플러스 사이즈로 나눌 수 있으며 그 사이에 틈이 있습니다. 전형적인 소비자의 옷과 비교하여 모델에 어떻게 다른 옷이 맞는지에 대한 사실적인 비디오는 그들이 고군분투하는 데 혼자라고 믿었던 많은 사람들에게 반향을 일으켰습니다.[139][140][141]

성형외과

성형수술을 홍보하는 콘텐츠는 TikTok에서 인기가 있으며 플랫폼에서 여러 가지 바이러스 트렌드를 낳았습니다. 2021년 12월, 미국 성형외과학회지인 성형외과는 틱톡에 일부 성형외과 의사들의 인기에 대한 기사를 실었습니다. 기사에서 성형외과 의사들은 의료 분야에서 소셜 미디어를 가장 빨리 채택한 사람들 중 일부이며 많은 사람들이 플랫폼에서 영향력 있는 사람으로 인식되었다고 언급했습니다. 이 기사는 2021년 2월까지 틱톡에서 가장 인기 있는 성형외과 의사에 대한 통계를 발표했으며 당시 5명의 다른 성형외과 의사가 플랫폼에서 100만 명의 팔로워를 돌파했습니다.[142][143]

2021년 틱톡에서 #노즈잡체크(#NoseJobCheck) 트렌드로 알려진 트렌드가 입소문을 타고 있다는 소식이 전해졌습니다. 틱톡(TikTok) 콘텐츠 제작자들은 코 성형 수술 전후에 코가 어떻게 보이는지 보여주면서 비디오에 특정 오디오를 사용했습니다. 2021년 1월까지 해시태그 #nosejob은 누적 조회수 16억, #nosejobcheck은 누적 조회수 10억, #nosejobCheck 트렌드에 사용된 오디오는 120,000개의 비디오에 사용되었습니다.[144] 2020년 당시 틱톡에서 가장 많이 팔로잉된 찰리 다멜리오(Charli D'Amelio)도 #코잡체크(NoseJobCheck) 영상을 만들어 이전에 부러진 코를 고치기 위한 수술 결과를 보여주었습니다.[145]

2022년 4월, NBC 뉴스는 외과 의사들이 청중들에게 시술을 광고하기 위해 플랫폼에서 인플루언서들에게 할인 또는 무료 미용 수술을 제공하고 있다고 보도했습니다. 그들은 또한 이러한 수술을 제공한 시설들이 틱톡에 그들에 대해 게시하고 있다고 보고했습니다. 틱톡은 플랫폼에서 성형수술 광고를 금지했지만 성형외과 의사들은 여전히 무보수 사진과 동영상 게시물을 사용하여 많은 청중에게 접근할 수 있습니다. NBC는 해시태그 '#성형수술'과 '#립필러'를 사용한 동영상이 해당 플랫폼에서 총 260억 건의 조회수를 기록했다고 보도했습니다.[146]

2022년 12월, 협측 지방 제거라는 미용 성형 시술이 플랫폼에서 입소문을 타고 있다는 소식이 전해졌습니다. 이 시술은 얼굴을 더 날씬하고 끌리는 모습으로 만들기 위해 뺨의 지방을 외과적으로 제거하는 것을 포함합니다. 협측 지방 제거와 관련된 해시태그를 사용한 동영상은 총 1억 8천만 건 이상의 조회수를 기록했습니다. 일부 틱톡 사용자들은 이 유행이 얻을 수 없는 아름다움의 기준을 조장한다고 비판했습니다.[147][148][149]

STEM 피드

2023년 3월 틱톡은 과학, 기술, 엔지니어링 및 수학(STEM) 콘텐츠 전용 피드를 선보였습니다. 커먼센스 네트워크와 협력하여 안전 및 연령 적정성을 확인하고 정보의 신뢰성을 위해 포인터 연구소와 협력합니다.[150][151]

난방

2023년 1월 포브스는 "난방" 도구를 통해 틱톡이 일일 조회수의 1~2%를 차지하는 특정 동영상을 수동으로 홍보할 수 있다고 보도했습니다. 추천 알고리즘에 의해 자동으로 픽업되지 않는 콘텐츠와 인플루언서를 성장시키고 다양화하기 위한 방법으로 이 관행이 시작되었습니다. 또한 FIFA 월드컵이나 테일러 스위프트와 같은 브랜드, 아티스트, NGO를 홍보하는 데 사용되었습니다.[152] 그러나 일부 직원들은 자신의 계정이나 배우자의 계정을 홍보하기 위해 이를 악용했고, 다른 직원들은 자신의 지침이 너무 많은 재량의 여지를 남긴다고 느꼈습니다. 틱톡은 미국에서 난방을 승인할 수 있는 사람은 극소수에 불과하며 홍보 영상은 사용자 피드의 0.002% 미만을 차지한다고 밝혔습니다. 중국의 영향력에 대한 우려를 해소하기 위해 향후 난방은 미국 내 검증된 보안 요원만이 수행할 수 있도록 미국 내 외국인투자위원회(CFIUS)와 협상을 진행 중이며, 이 과정은 오라클 등 제3자의 감사를 받게 됩니다.[153]

검열과 절제

틱톡과 더우인의 검열 정책은 투명하지 않다는 비판을 받아왔습니다. 1989년 천안문 광장 시위 및 학살, 파룬궁, 티베트, 대만, 체첸, 북아일랜드, 캄보디아 대량학살, 1998년 인도네시아 폭동, 쿠르드 민족주의 등과 관련된 내용을 금지하기 위하여 폭력의 조장, 분리주의, '국가의 민주화'를 반대하는 내부 지침을 사용할 수 있을 것이고, 흑인과 백인, 또는 다른 이슬람 종파들 사이의 민족적 갈등 좀 더 구체적인 목록은 러시아, 미국, 일본, 북한과 한국, 인도, 인도네시아, 그리고 튀르키예의 과거와 현재의 지도자들을 포함한 세계 지도자들에 대한 비판을 금지했습니다. 2019년 틱톡은 위구르족에 대한 신장 수용소의 인권 유린에 대한 동영상을 삭제했다가 50분 만에 작성자 계정과 함께 복구하면서 이 행동이 실수였고 다른 게시물에 오사마 빈 라덴의 짧은 "비극적인" 이미지에 의해 촉발됐다고 밝혔습니다.[156][157]

TikTok 중재자는 표시된 사용자가 "너무 못생겼거나, 가난하거나, 장애인"으로 간주되는 경우 "For You" 권장 사항의 게시물을 억제하라는 지시를 받았습니다.[158][159] 합법적인 장소에서도 술, 전체 또는 부분 나체, 성소수자 및 성간 내용물의 섭취가 제한되었습니다.[160] 이후 틱톡은 사과하고 반LGBTQ 이념에 대한 금지 조치를 취했지만, 중국 내 규제로 더우인에 대한 검열은 계속되고 있습니다.[161][162] 더우인 가이드라인은 또 미등록 외국인의 생중계, '봉건적 미신', '돈 숭배', 흡연과 음주, '이미 비만'인의 경쟁적 식사, '독성' 슬라임, 귀 핥기와 같은 '포노그래픽' ASMR, 노출이 심한 옷을 입은 여성 앵커 등도 금지하고 있습니다.[155]

ByteDance는 초기 지침이 글로벌하고 플랫폼이 여전히 성장하고 있을 때 온라인 괴롭힘과 분열을 줄이는 것을 목표로 한다고 말했습니다. 다른 지역의 사용자를 위해 현지 팀에서 맞춤형 버전으로 대체되었습니다.[163]

시티즌 랩의 2021년 3월 연구에 따르면 틱톡은 검색을 정치적으로 검열하지 않았지만 게시물의 여부에 대해서는 결론이 나지 않았습니다.[3][164] 조지아 공과대학 인터넷 거버넌스 프로젝트의 2023년 논문은 틱톡이 "직접 자료를 차단하거나 추천 알고리즘을 통해 간접적으로 검열을 수출하지 않는다"고 결론지었습니다.[165]

정밀 조사가 강화된 후 틱톡은 일부 외부 전문가에게 필터, 키워드, 가열 기준 및 소스 코드를 포함한 플랫폼의 익명화된 데이터 세트 및 프로토콜에 대한 액세스 권한을 부여한다고 밝혔습니다.[166][167]

럿거스 대학 연구진의 2023년 연구에 따르면 "틱톡에 대한 콘텐츠가 중국 정부의 이익과 일치하는 것을 기반으로 증폭되거나 억제될 가능성이 높습니다."[168] 그 후 연구원들은 틱톡이 민감한 주제의 해시태그를 분석하는 기능을 제거했다는 것을 발견했습니다.[169] 틱톡은 자사 크리에이티브 센터에서 검색할 수 있는 해시태그 수를 제한한 이유는 "잘못된 결론을 내리기 위해 잘못 사용된 것"이라고 밝혔습니다.[170][171]

카토 연구소의 한 역사학자는 럿거스 대학의 연구에 "기본적인 오류"가 있었다고 말하고 그 뒤에 이어진 무비판적인 뉴스 보도를 비판했습니다. 이 연구는 틱톡이 존재하기도 전의 데이터를 비교하여 앱이 역사적으로 민감한 주제에 대한 해시태그를 적게 가지고 있음을 보여줌으로써 결과를 왜곡합니다.[172][170]

극단주의와 증오

반유대주의, 이슬람 혐오증, 인종차별, 외국인 혐오증과 같은 극우 극단주의와 관련된 내용과 이를 촉진하고 확산하는 것에 대해 우려의 목소리가 제기되었습니다. 일부 영상은 홀로코스트 부인을 명시적으로 홍보하고 시청자들에게 백인 우월주의와 스와스티카의 이름으로 무기를 들고 싸우라고 말했습니다.[173] 틱톡이 어린 아이들 사이에서 인기를 얻고,[174] 극단주의적이고 혐오스러운 콘텐츠의 인기가 높아지면서 이들의 유연한 경계를 더욱 엄격하게 제한해야 한다는 요구가 나왔습니다. 이후 틱톡은 부적절한 콘텐츠를 걸러내고 충분한 보호와 보안을 제공할 수 있도록 더 강력한 부모 통제를 출시했습니다.[175]

말레이시아에서 틱톡은 특히 2022년 선거 이후 5월 13일 사건을 언급하며 인종과 종교에 대한 혐오 발언을 하는 데 일부 사용자들이 사용하고 있습니다. 틱톡은 커뮤니티 가이드라인을 위반한 내용의 동영상을 삭제하는 방식으로 대응했습니다.[176]

2019년 10월, 틱톡은 ISIL 선전 및 실행 동영상을 앱에 게시한 약 24개의 계정을 삭제했습니다.[177][178]

2023년 3월, 유대인 크로니클은 틱톡이 여전히 신나치 선전 영화 유로파를 홍보하는 비디오를 주최했다고 보도했습니다. 4개월 전에 이 문제에 대해 경고했음에도 불구하고 마지막 전투. 틱톡은 콘텐츠와 관련 계정을 삭제하고 계속 삭제할 것이며 검색어도 차단했다고 밝혔습니다.[179]

그래픽 내용

2021년 6월, 틱톡은 한 소녀가 춤을 추는 모습을 보여준 충격적인 영상이 화제가 된 후 사과했습니다. 이제 동영상이 업로드되기 전에 자동으로 감지되는 틱톡의 블랙리스트로 전송되었습니다.[180] 틱톡은 이전에 2020년 9월에 유포된 자살 동영상을 포함하여 플랫폼에서 그래픽 콘텐츠를 제거하기 위해 노력했으며, 이 동영상은 틱톡의 For You 섹션의 권장 클립에 표시되었습니다.[181][182]

오보

틱톡은 홀로코스트 부인을 금지했지만, 2020년 6월까지 해시태그가 각각 8,000만뷰, 5,000만뷰를 기록한 피자게이트와 큐논(미국 알트우파에서 인기 있는 두 가지 음모론) 등 다른 음모론이 플랫폼에서 인기를 끌고 있습니다.[183] 이 플랫폼은 또한 팬데믹의 클립과 같은 COVID-19 팬데믹에 대한 잘못된 정보를 퍼뜨리는 데 사용되었습니다.[183] 틱톡은 이들 영상 중 일부를 삭제하고 일반적으로 팬데믹 관련 태그가 부착된 영상에 대한 정확한 코로나19 정보 링크를 추가했습니다.[184]

2020년 1월, 좌파 미디어 워치독 미디어 매터스 포 아메리카(Media Matters for America)는 틱(Tik)이톡은 최근 잘못된 정보에 대한 정책에도 불구하고 코로나19 팬데믹과 관련된 잘못된 정보를 호스팅했습니다.[185] 2020년 4월 인도 정부는 TikTok에 COVID-19 팬데믹과 관련된 잘못된 정보를 게시하는 사용자를 제거할 것을 요청했습니다.[186] 정부가 팬데믹 확산에 관여하고 있다는 음모론도 다수 제기됐습니다.[187] 2020년 하반기 미국에서 선거 오보에 대한 34만 개 이상의 동영상과 코로나19 오보에 대한 5만 개의 동영상이 제거되었다고 보고했습니다.[188]

틱톡은 2022년 미국 중간선거에서 잘못된 정보를 방지하기 위해 40개 언어로 된 사용자들에게 인앱으로 제공할 수 있는 중간선거센터를 발표했습니다. 틱톡은 전미 국무장관 협회와 제휴를 맺고 사용자들에게 정확한 현지 정보를 제공합니다.[189]

2022년 9월, 뉴스가드 테크놀로지스는 미국에서 실시하고 분석한 틱톡 검색 중 19.4%가 코로나19 백신에 대한 의심스럽거나 유해한 내용, 집에서 만든 치료법, 2020년 미국 선거, 러시아의 우크라이나 침공, 롭 초등학교 총기난사, 낙태 등 잘못된 정보를 드러냈다고 보도했습니다. NewsGuard는 이와 대조적으로 구글의 결과가 더 높은 품질이라고 제안했습니다.[190] 호주에서 온 매셔블의 자체 테스트에서 '내 코로나 백신 접종'을 검색한 결과 무해한 결과가 나왔지만 '기후변화'를 입력한 후 '기후변화는 신화'와 같은 제안이 나왔습니다.[188]

2023년 11월, 싱가포르 법률 및 내무부 장관 K. 샨무감은 틱톡이 자신에 대한 허위·명예훼손 정보를 유포했다고 비난하는 사용자 3명의 신원에 대한 정보를 제공하도록 요구하는 법원 명령을 신청했습니다. 사용자들은 celebscritic.com 이 K를 주장하는 글을 TikTok에 공유했습니다. 샨무감은 혼외정사에 연루되었습니다.[191]

러시아의 우크라이나 침공

2022년 기준 틱톡은 러시아에서 10번째로 인기 있는 앱입니다.[192] 2022년 3월 새로운 러시아 전쟁 검열법이 설치된 후 회사는 러시아 및 비러시아 게시물과 라이브 스트림에 대한 일련의 제한을 발표했습니다.[193][194] 사용자 데이터 권한 그룹인 Tracking Exposed는 친러시아 포스터에 의해 악용된 기술적 결함일 가능성이 있는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 비록 이것과 다른 허점들이 3월 말 이전에 틱톡에 의해 패치되었지만, 크렘린의 "가짜 뉴스" 법의 효과에 더해 초기에 이 제한을 올바르게 이행하지 못한 것이 러시아에서 "전쟁 전 콘텐츠에 의해 지배되는 spl 인터넷"을 형성하는 데 기여했다고 밝혔습니다.[195][192] 틱톡은 전쟁에 대한 여론을 흔들면서도 기원을 모호하게 했다는 이유로 204개의 계정을 삭제했으며 팩트체크자들이 잘못된 정보 정책을 위반했다는 이유로 41,191개의 비디오를 삭제했다고 밝혔습니다.[196][197]

2023년 12월, BBC 뉴스는 러시아의 선전과 허위 정보를 홍보하는 800개에 가까운 가짜 틱톡 계정을 발견했다고 보도했습니다. 틱톡 자체 조사 결과 영어와 이탈리아어 등 부가어를 사용하는 계정을 포함해 1만 2천 개가 넘는 가짜 계정이 발견됐습니다.[198]

페미니즘

Tik에 대한 인기와 접근성의 증가톡은 디지털 페미니스트 운동과 플랫폼에서 비롯된 담론의 인기 증가에 기여했습니다. 틱톡과 같은 디지털 공간은 페미니스트와 같은 소외된 커뮤니티와 활동가가 더 안전하고 토론과 대화에 참여하거나 상황에 따라 불가능할 수 있는 정체성을 구축하는 데 더 용이한 장소로 느낄 수 있도록 합니다.[200] 틱톡과 같은 플랫폼을 통한 디지털 페미니스트 운동의 모멘텀은 전 세계의 많은 소셜 미디어 에이전트와 마케팅 캠페인이 온라인 이미지 또는 개인 브랜드의 일부로 어느 정도의 페미니즘을 채택하도록 장려했습니다. 자발적인 피어-피어 정보 공유라는 틱톡의 독특한 플랫폼 조직은 커뮤니티 참여, 디지털 지식 동원 및 사회 정의 커뮤니티 간 교류를 위한 활용을 가능하게 했습니다.[202] 플랫폼의 유기적인 잠재력에 의해 역으로 활성화되었지만, 페미니스트 문제와 지배적인 사회적, 계층적, 성별 가치의 반 페미니스트 강화는 모두 틱톡을 통해 널리 확산되고 선동되며, 반 페미니스트이라고 라벨링된 콘텐츠 자체가 틱톡에서 대중화됩니다.

사용.

인구통계

틱톡은 사용자의 41%가 16세에서 24세 사이이기 때문에 젊은 사용자에게 어필하는 경향이 있습니다. 2021년[update] 기준으로 이들은 Z세대로 간주됩니다.[81] 이런 틱톡 사용자 중 90%가 매일 앱을 사용한다고 답했습니다.[203] 2019년 틱톡의 지리적 용도에 따르면 소셜 플랫폼이 인도에서 금지되기 전 신규 사용자의 43%가 인도 출신인 것으로 나타났습니다.[204] 하지만 어른들도 틱톡에서 성장을 보였습니다. 틱톡에서 정기적으로 소식을 듣는 미국 성인의 비율은 2023년에 14%를 기록했습니다.[205]

영국 규제 기관인 오프콤의 보고서에 따르면 2023년 7월까지 틱톡은 12~15세 청소년의 28%가 플랫폼에 의존하는 등 소셜 미디어에서 영국 청소년의 주요 뉴스 소스가 되었습니다. BBC One/Two와 같은 전통적인 소스는 82%로 더 신뢰받고 있습니다.[206]

2022년 1분기 기준으로 미국의 월간 활성 사용자 수는 1억 명, 영국은 2,300만 명을 넘어섰습니다. 하루 평균 사용자는 앱에서 1시간 25분을 보내고 틱톡을 17번 개통했습니다.[207] 2022년 분석에 따르면 틱톡의 상위 100명의 남성 크리에이터 중 67%가 백인이었고 54%는 완벽에 가까운 얼굴 대칭성을 가지고 있었습니다.[208]

인기 있는 틱톡 사용자들은 주로 로스앤젤레스 지역에서 공동 주택에서 집단 생활을 해왔습니다.[209]

틴에이저 모드

중국은 특히 2018년 이후 더우인이 미성년자에게 사용되는 방식을 엄격하게 규제합니다.[210] 정부의 압력 아래 바이트댄스는 부모 통제와 지식 공유 등 화이트리스트 콘텐츠만 보여주는 '10대 모드'를 도입하고 장난, 미신, 댄스 클럽, 친 LGBT 콘텐츠를 금지했습니다.[a][161] 미성년자가 나이를 속이거나 성인의 계정을 이용하는 것을 막기 위해 만 14세 미만 이용자에 대한 의무적인 화면 제한과 실제 신원에 대한 계정 연동 요건이 마련됐습니다. 더우인과 틱톡의 차이점으로 인해 일부 미국 정치인과 논평가들은 회사나 중국 정부가 악의적인 의도를 가지고 있다고 비난했습니다.[210][211] 2023년 3월, 틱톡은 18세 미만 사용자에 대한 기본 화면 제한을 발표했습니다. 13세 미만은 시간을 연장하려면 부모님의 비밀번호가 필요합니다.[210]

미성년자 사용자

어린이들에게 인기 있는 다른 플랫폼들과 마찬가지로, 미성년자 사용자들은 그들의 일상과 위치를 무심코 드러낼 수 있고, 성적 약탈자들에 의한 잠재적인 오용에 대한 우려를 제기합니다.[212][213] 보고 당시(2018년) 틱톡은 중간 근거 없이 비공개 또는 완전히 공개된 두 가지 개인 정보 보호 설정만 있었습니다.[214] 노출이 심한 옷을 입고 춤을 추는 어린 소녀들과 같은 "섹시" 비디오의 댓글 섹션에는 나체 사진 요청이 포함되어 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 틱톡 자체는 비디오와 사진의 직접 메시지를 금지하고 있으며, 이는 후속 상호 작용이 있는 경우 다른 형태로 이루어져야 한다는 것을 의미합니다.[215][216]

최근 몇 년 동안, 미국은 미성년 소녀들에 대한 틱톡의 불법 행위로 성범죄자들을 기소하고 징역형을 선고했습니다.[217][218][219][220]

2021년 1월 22일, 이탈리아 데이터 보호 당국은 틱톡이 연령을 설정할 수 없는 이탈리아 사용자를 일시적으로 중단할 것을 요구했습니다.[221] 이 명령은 인터넷 도전에 연루된 10살 시칠리아 소녀가 사망한 후에 내려졌습니다. 틱톡은 이탈리아에 있는 사용자들에게 13세 이상이라는 사실을 다시 확인해달라고 요청했습니다. 5월까지 연령 확인에 실패하여 50만 개 이상의 계정이 제거되었습니다.[222]

2021년 7월, 네덜란드 데이터 보호 당국은 TikTok이 개인 정보 보호 성명서를 영어로만 제공하고 네덜란드어로 제공하지 않은 것에 대해 750,000유로의 벌금을 부과했습니다. 여기에 틱이 있다고 적혀있습니다.톡은 16세 미만 이용자에게 직접 메시지를 보내는 것을 금지하고 부모가 짝을 이룬 가족 계정을 통해 직접 사생활 설정을 관리할 수 있도록 하는 등 긍정적인 조치를 시행했지만, 계정을 만들 때 아이들이 나이 든 척할 위험은 여전합니다.[223][224]

틱톡은 BBC 뉴스 조사 결과 시리아 난민 캠프에서 수백 개의 계정이 생중계되는 것으로 밝혀지자 생중계 최소 연령을 16세에서 18세로 올렸습니다. 그들 중 30명은 디지털 기부를 위해 구걸하는 아이들의 모습을 보여주었습니다. 틱톡은 이 중 일부에 대해 70%의 수수료를 부과한 것으로 알려졌는데, 이는 회사가 이의를 제기한 수치입니다.[225]

2024년 3월, 이탈리아 경쟁 당국은 틱톡이 "프렌치 흉터" 챌린지와 같은 해로운 콘텐츠로부터 미성년자 사용자를 적절하게 보호하지 않아 사람의 뺨에 심한 핀치 마크를 남겼습니다.[226]

인플루언서 마케팅

틱톡은 이용자들이 재미뿐만 아니라 돈을 주고 콘텐츠를 만들 수 있는 플랫폼을 제공했습니다. 지난 몇 년 동안 플랫폼이 크게 성장함에 따라 기업은 광고를 하고 인플루언서 마케팅을 통해 의도한 인구 통계에 빠르게 도달할 수 있게 되었습니다. 플랫폼의 AI 알고리즘은 사용자의 선호도에 따라 콘텐츠를 선택하기 때문에 인플루언서 마케팅 잠재력에도 기여합니다. 후원 콘텐츠는 다른 소셜 미디어 앱만큼 플랫폼에서 널리 퍼지지는 않지만 브랜드와 인플루언서는 다른 플랫폼에 비해 더 많이 벌지는 않더라도 얼마든지 벌 수 있습니다.[228] 좋아요와 댓글과 같은 참여를 통해 돈을 버는 플랫폼의 인플루언서를 '밈 머신'이라고 합니다.[227]

2021년 뉴욕타임즈는 "BookTok"이라는 레이블이 태그된 책의 정서적 영향과 관련된 젊은이들의 바이럴 틱톡 영상이 문학 판매를 크게 이끌었다고 보도했습니다. 출판사들은 점점 더 플랫폼을 인플루언서 마케팅의 장으로 사용하고 있었습니다.

2022년 12월, NBC 뉴스는 텔레비전 부문에서 일부 틱톡과 유튜브 인플루언서들이 플랫폼 사용자들에게 수술을 광고하기 위해 무료 및 할인된 미용 수술을 제공하고 있다고 보도했습니다.[230]

2022년에는 influ 마케팅에 대한 반발로 플랫폼에서 '탈 influ 센싱'이라는 트렌드가 유행했다고 합니다. 이 트렌드에 참여하는 틱톡 크리에이터들은 인플루언서들이 홍보하는 제품을 비판하는 영상을 만들고, 시청자들에게 필요 없는 제품을 사지 말라고 당부했습니다. 하지만 트렌드에 참여하는 일부 크리에이터들은 당초 비판하던 인플루언서들과 같은 방식으로 자사 오디언스들에게 대체 상품을 홍보하고 제휴사 링크를 통해 만들어진 매출로 수수료를 받기 시작했습니다.[231][232]

2022년 6월, NBC 뉴스는 발 페티시 콘텐츠를 판매하는 웹사이트인 피트파인더가 지불한 인플루언서 중 일부가 자신들의 영상을 공개하지 않았다고 보도했습니다. 피트파인더는 인플루언서들에게 누가 그들에게 자금을 지원했는지에 대해 솔직해질 것을 제안했다고 말했습니다. 피트파인더의 기존 판매자들은 그 비디오들이 종종 발 사진을 올려 돈을 버는 것이 얼마나 "쉬운"지를 잘못 표현했다고 말했습니다. 다른 틱톡 제작자들은 무분별한 후원 계약 수락에 반대하는 목소리를 냈고 공개되지 않은 피트파인더 광고를 게시한 사람들을 비난했습니다.[233]

기업

2020년 10월, 전자상거래 플랫폼 쇼피파이(Shopify)는 소셜 미디어 플랫폼 포트폴리오에 틱톡(TikTok)을 추가하여 온라인 판매자가 틱톡에서 소비자에게 직접 제품을 판매할 수 있도록 했습니다.[234]

일부 소규모 기업은 틱톡을 사용하여 광고를 하고 일반적으로 제공하는 지리적 지역보다 더 넓은 청중에게 다가가기도 했습니다. 많은 소기업 틱톡 비디오에 대한 바이러스성 반응은 틱톡의 알고리즘에 기인하며, 이 알고리즘은 시청자들이 전반적으로 관심을 갖지만 적극적으로 검색하지는 않을 것으로 보이는 콘텐츠(양봉 및 벌목과 같은 비전통적인 유형의 기업에 대한 비디오)를 보여줍니다.[235]

2020년 그룹 나인 미디어와 글로벌과 같은 디지털 미디어 회사들은 틱톡 인플루언서와의 파트너십 중개 및 브랜드 콘텐츠 캠페인 개발과 같은 전술에 초점을 맞춰 틱톡을 점점 더 많이 사용했습니다.[236] 2019년[237] 5월 치폴레와 데이비드 도브릭의 파트너십, 2020년 9월 던킨도너츠와 찰리 다멜리오의 파트너십 등 대규모 브랜드와 최고의 틱톡 인플루언서 간의 주목할 만한 협업이 이루어졌습니다.[238]

성노동자

틱톡은 온리팬스와 같은 플랫폼에서 판매되는 포르노 콘텐츠를 홍보하기 위해 성노동자들이 정기적으로 사용합니다.[239] 한 포르노 배우가 자신을 '회계사'라고 지칭하는 바이럴 송을 올려 유행을 시작했습니다.[240] 2020년 틱톡은 "프리미엄 성 콘텐츠"를 홍보하는 콘텐츠를 금지하기 위해 서비스 조건을 업데이트하여 다수의 성인 콘텐츠 제작자에게 영향을 미쳤습니다.[241] 이에 대응하여 캡션과 비디오에 단어를 대체하고 필터를 사용하여 명시적인 이미지를 검열하기 시작했습니다.[242][243] 일부 성인 콘텐츠 제작자들은 틱톡의 추천 알고리즘을 해결하려고 노력하고 실패하는 많은 시청자들을 끌어들이는 수수께끼를 게시함으로써 게임화할 수 있는 방법을 찾았습니다. 그들 중 일부는 크리에이터의 OnlyFans 계정으로 리디렉션되어 그곳의 구독자로 끝납니다.[244]

선거운동

2021년부터 틱톡은 유럽 의회 선거를 앞두고 플랫폼에 "선거 센터"를 만들었습니다. EP 의원의 약 30%가 자신의 메시지를 전달하고 잘못된 정보를 제거하기 위해 틱톡을 사용합니다.[245]

2024년 2월, 조 바이든 미국 대통령의 재선 캠페인은 "고급 안전 예방 조치"를 취하면서 틱톡 계정을 개설했다고 발표했습니다. Biden은 Super Bowl LVIII 기간 동안 자신의 첫 번째 비디오를 게시했습니다.[246] 이 조치는 보안 문제로 많은 의원들로부터 비판을 받았습니다. 바이든 행정부는 2022년부터 러시아의 우크라이나 침공과 미국의 학자금 부채 탕감과 같은 뉴스 항목에 대해 틱톡커들에게 브리핑하고 있습니다.[247][248]

개인 정보 보호 및 보안 문제

앱과 관련하여 개인 정보 보호 문제가 제기되었습니다.[249][250] 틱톡의 개인 정보 보호 정책은 앱이 사용 정보, IP 주소, 사용자의 이동 통신사, 고유 장치 식별자, 키 입력 패턴 및 위치 데이터 등을 수집한다고 나열합니다.[251] 수집된 다른 정보에는 사용자가 보는 콘텐츠뿐만 아니라 사용자가 만든 콘텐츠를 기반으로 사용자가 추론한 관심사가 포함됩니다.[20] 틱톡은 바이트댄스를 비롯한 자사 기업집단과 데이터를 공유할 수 있습니다. 이 회사는 미국에 기반을 둔 팀이 감독하는 접근 통제 및 승인 프로세스를 사용한다고 말합니다.[20] 2021년 6월, 틱톡은 특수 효과 및 기타 목적을 위해 "페이스프린트 및 성문"을 포함한 잠재적인 생체 데이터 수집을 포함하도록 개인 정보 보호 정책을 업데이트했습니다. 약관에는 현지 법률이 요구하는 경우 사용자 승인이 요청된다고 명시되어 있습니다.[252] 전문가들은 미국의 일반적인 강력한 데이터 개인 정보 보호 법이 없기 때문에 이러한 법이 "모호하고" 미국에 미치는 영향이 "문제가 있다"고 생각했습니다.[253] 2022년 11월 유럽 개인 정보 보호 정책 업데이트에서 틱톡은 중국 및 기타 국가의 글로벌 기업 그룹 직원이 "실증된 필요성"을 기반으로 유럽 계정의 사용자 정보에 원격 액세스할 수 있다고 밝혔습니다.[254]

시티즌 랩의 2021년 3월 연구에 따르면 틱톡은 업계 규범, 정책에 명시된 내용 또는 추가 사용자 허가 없이 데이터를 수집하지 않았습니다.[164]

2023년 5월, 월스트리트 저널은 전직 직원들이 성소수자 관련 콘텐츠를 본 사용자를 추적하는 틱톡에 대해 불만을 제기했다고 보도했습니다. 이 회사는 알고리즘이 신원이 아닌 관심사를 추적하고 LGBT가 아닌 사용자도 이러한 콘텐츠를 볼 수 있다고 말했습니다.[255]

중국 정부의 잠재적 데이터 수집

틱톡의 소유주인 바이트댄스에 대한 중국 정부의 잠재적 통제와 영향력,[256] 특히 2017년 중국 국가정보법의 치외법적 영향력에 대한 우려가 제기되고 있습니다.[257][258] 법률의 한 조항은 모든 조직과 시민들이 "국가 정보 노력을 지원하고, 지원하고, 협력해야 한다"고 주장합니다.[259][260] 분석가들은 데이터 수집 위험에 대한 평가에 차이가 있습니다. 전략국제문제연구소의 짐 루이스는 틱톡이 중국 정부의 데이터 요청에 대해 항소할 권리가 없을 것이라고 말했습니다.[20] 일부 사이버 보안 전문가들은 개별 사용자가 위험에 처해 있지 않다고 말합니다.[261] 미국은 틱톡이 중국 당국과 이러한 정보를 공유했다는 증거를 제시하지 않았습니다.[262] TikTok의 Project Texas는 사용자 데이터를 미국 내에 보관하는 것이 동기가 되었습니다.[20]

중국 및 미국에서의 액세스 응답

2021년 10월, 2021년 페이스북 유출과 소셜 미디어 윤리에 대한 논란이 일자, 미국의 초당파 의원 모임은 틱톡, 유튜브, 스냅챗에 데이터 개인 정보 보호와 연령에 적합한 콘텐츠에 대한 절제에 대한 질문을 제기했습니다. 의원들은 틱톡이 중국 모기업 바이트댄스를 통해 중국 정부에 소비자 데이터를 넘길 수 있는지에 대해서도 '망언'했습니다.[263] 틱톡은 중국 정부에 정보를 제공하지 않으며 "미국 사용자 데이터"는 싱가포르에 백업과 함께 국내에 저장된다고 밝혔습니다.[264]

2022년 6월 버즈피드 뉴스는 내부 틱톡 회의의 유출된 오디오 녹음을 통해 중국의 직원들이 "모든 것"을 볼 수 있는 "마스터 관리자"를 포함하여 해외 데이터에 접근할 수 있었다고 보도했습니다. 녹음 중 일부는 미국 정부 계약자인 부즈 앨런 해밀턴과 협의하는 과정에서 이뤄졌습니다. 계약업체 대변인은 보고서의 일부 정보가 부정확하지만 틱톡이 고객 중 하나인지 확인하지도 부인하지도 않을 것이라고 말했습니다.[265] 이에 따라 마크 워너 의원과 마르코 루비오 의원 등 상원 정보위원회는 연방통신위원회(FCC)에 바이트댄스와 틱톡이 이들을 오도했는지 여부를 조사할 것을 요구했습니다.[266][267] 이 보도에 따라 틱톡은 중국 내 직원들이 미국 데이터에 접근할 수 있다고 확인했습니다.[268] 또한 이제 오라클 클라우드를 통해 미국 사용자 트래픽을 라우팅하고 다른 서버에서 백업 복사본을 삭제할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[269]

2022년 6월, 브렌던 카 FCC 위원은 민감한 데이터가 베이징에서[270][271] 액세스되고 있으며 바이트댄스는 "법에 따라 [중국 정부] 감시 요구를 준수해야 한다"며 구글과 애플에 틱톡을 앱 스토어에서 제거할 것을 요구했습니다.[270] 2022년 11월 크리스토퍼 A. 레이 연방수사국(FBI) 국장은 중국 정부가 틱톡을 이용자들에 대한 영향력 행사에 활용할 수 있다고 말했습니다.[272]

2023년 5월, 전 바이트댄스 직원은 2018년 중국 공산당 당원들이 홍콩 사용자의 기기 정보 및 통신, 특히 2019~2020년 홍콩 시위의 시위대 정보에 접근했다며 부당 해지 소송을 제기했습니다.[273][274][275] 바이트댄스 측은 직원이 사라진 프로젝트를 진행했으며 틱은 이를 부인했습니다.톡은 2020년 홍콩에서 퇴출되었습니다.[274]

2023년 6월, 틱톡은 미국 콘텐츠 제작자의 세금 양식과 사회보장번호와 같은 일부 금융 정보가 중국에 저장되어 있음을 확인했습니다. 이는 ByteDance와 계약을 체결하고 ByteDance로부터 결제 거래를 받는 사람들에게 적용됩니다. 유사한 정보가 "보호된 사용자 데이터"로 취급되지 않도록 유지될 것인지 여부는 미국 외국인 투자 위원회(CFIUS)와 협의 중입니다.[276] 2024년 2월, 국가정보국장의 미분류 연례 위협 평가에서 중국 정부가 운영하는 틱톡 계정이 2022년 미국 선거에 영향력을 행사했다고 밝혔습니다.[277]

프로젝트 텍사스

틱톡은 미국 정부의 보안 우려에 대응해 미국 정부나 오라클 등 제3자의 관리 하에 미국 내 특권 사용자 데이터 사일로화 작업을 진행해 왔습니다.[278] Project Texas로 명명된 이 이니셔티브는 무단 액세스, 주 영향력 및 소프트웨어 보안에 중점을 둡니다. 사용자 데이터, 소프트웨어 코드, 백엔드 시스템 및 콘텐츠 조정을 관리하기 위해 새로운 자회사인 TikTok U.S. Data Security Inc.(USDS)가 설립되었습니다. 고용 관행에 대해서도 바이트댄스나 틱톡이 아닌 미국 내 외국인투자위원회(CFIUS)에 보고할 예정입니다. Oracle은 USDS를 통해 데이터 흐름을 검토하고 확인합니다. 또한 소프트웨어 코드에 디지털 서명하고 업데이트를 승인하며 콘텐츠 조정 및 권장 사항을 감독합니다. 오라클과 미국 정부가 자체적으로 검토할 수 있도록 물리적 위치를 설정합니다.[279] 당사는 2021년부터 CFIUS와 프로젝트에 대한 비밀 협상을 진행해 왔으며 제안서를 제출했지만 이후 패널로부터 거의 응답을 받지 못했습니다.[280]

2023년 3월, 이 회사의 전직 직원은 텍사스 프로젝트가 충분하지 않으며 완전한 "재공학"이 필요할 것이라고 말했습니다. 이에 틱톡은 프로젝트 텍사스가 이미 앱을 리엔지니어링한 것이라며 프로젝트 사양이 확정되기 전인 2022년 전 직원이 퇴사했다고 맞받았습니다.[281]

프로젝트 클로버

틱톡은 유럽 사용자 데이터를 미국에 있는 서버로 전송해 비난에 직면했습니다. 영국의 국가 사이버 보안 센터와 유럽 정보를 현지에 저장하는 "프로젝트 클로버"에 대한 논의를 진행하고 있습니다. 이 회사는 아일랜드에 2개의 데이터 센터를 건설하고 노르웨이에 1개의 데이터 센터를 추가로 건설할 계획입니다. 제3자는 틱톡과 독립적으로 사이버 보안 정책, 데이터 흐름 및 인력 액세스를 감독합니다.[282][283][14]

언론인 간첩 사건

2022년 10월, 포브스는 바이트댄스의 한 팀이 공개되지 않은 이유로 특정 미국 시민들을 감시할 계획을 세웠다고 보도했습니다. 틱톡은 정확한 GPS 정보가 플랫폼에서 수집되지 않기 때문에 보고서가 제시한 추적 방식은 실현 가능하지 않을 것이라고 밝혔습니다.[284][285] 2022년 12월, 바이트댄스는 내부 조사 후 두 명의 기자와 그들의 밀접 접촉자의 데이터가 중국과 미국에서 온 직원들에 의해 액세스되었음을 확인했습니다. 포브스와 파이낸셜 타임즈의 기자들을 만났을 수도 있는 유출원을 밝혀내기 위한 것이었습니다. 데이터에는 사용자의 위치를 근사화하는 데 사용할 수 있는 IP 주소가 포함되었습니다. 바이트댄스는 이에 대해 직원 4명을 해고했다고 밝혔습니다.[286]

이 사건은 미국 법무부와 FBI에 의해 조사되고 있습니다.[287][288][278] 미국 버지니아 동부 지방 검사는 바이트댄스로부터 틱톡에 대한 언론인 감시와 관련된 정보를 소환한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[18] 2023년 12월 미국 하원 전략경쟁위원회는 FBI에 사건 현황을 문의했습니다.[289]

소프트웨어코드

2020년 1월 체크포인트 리서치는 해커가 틱톡의 공식 SMS 메시지를 스푸핑하고 악성 링크로 대체하여 사용자 계정에 액세스할 수 있는 취약점을 발견했습니다. 나중에 틱톡에 의해 패치되었습니다.[290]

2020년 8월, 월스트리트 저널은 틱톡이 구글의 정책을 위반하는 전술로 MAC 주소와 IMEI를 포함한 안드로이드 사용자 데이터를 추적했다고 보도했습니다.[291][292]

2022년 8월, 소프트웨어 엔지니어이자 보안 연구원인 펠릭스 크라우제는 틱톡과 다른 플랫폼의 인앱 브라우저에 키로거 기능에 대한 코드가 포함되어 있지만 데이터가 추적되거나 기록되었는지 여부를 추가로 조사할 수단이 없다는 것을 발견했습니다. 틱톡에서 코드가 비활성화되어 있다고 합니다.[293]

규제조치

미국 연방 무역 위원회

2019년 2월 27일, 미국 연방 무역 위원회(FTC)는 13세 미만 미성년자의 정보를 수집한 것과 관련하여 아동 온라인 프라이버시 보호법(COPPA)을 위반하여 ByteDance U.S. 570만 달러의 벌금을 부과했습니다.[294] 이에 바이트댄스는 틱톡에 어린이 전용 모드를 추가해 동영상 업로드, 사용자 프로필 구축, 다이렉트 메시지, 타인의 동영상 댓글 등을 차단하는 동시에 콘텐츠를 보고 녹화할 수 있도록 했습니다.[295] 2020년 5월, 한 옹호단체는 틱(Tik)이톡은 2019년 2월 동의 법령의 조건을 위반했으며, 이로 인해 의회에서 공정위 조사를 재개해야 한다는 요구가 제기되었습니다.[296][297][298] 2022년 3월, COPPA 위반에 대한 집단 소송에 이어 틱톡은 미화 110만 달러에 합의했습니다.[299][300]

데이터 보호 위원회(유럽)

2021년 9월, 아일랜드 데이터 보호 위원회(DPC)는 틱톡에 대해 미성년자 데이터 보호 및 개인 데이터 중국 이전과 관련된 조사를 시작했습니다.[301][302] 아일랜드 DPC는 틱톡이 네덜란드와 이탈리아 당국이 시작한 조사를 이어받아 자국에 사무소를 설립한 뒤 이런 문제를 처리하는 주도 기관이 됐습니다.[303][223] 2023년 9월, DPC는 어린이 데이터를 잘못 취급한 것에 대한 일반 데이터 보호 규정(GDPR) 위반으로 틱톡에 3억 4,500만 유로의 벌금을 부과했습니다.[304][305]

영국 정보국장실

2019년 2월 영국 정보국장실(ICO)은 미국 연방거래위원회(FTC)로부터 받은 바이트댄스의 벌금에 따라 틱톡에 대한 조사에 착수했습니다. 엘리자베스 덴햄 정보국장은 의회 위원회에서 이번 조사는 개인 데이터 수집 문제, 온라인에서 어린이들이 수집하고 공유하는 동영상 종류, 성인 누구나 모든 어린이에게 메시지를 보낼 수 있는 플랫폼의 오픈 메시징 시스템에 초점을 맞추고 있다고 말했습니다. 그녀는 회사가 잠재적으로 GDPR을 위반하고 있다고 언급했습니다. GDPR은 회사가 어린이를 위해 다양한 서비스와 다양한 보호를 제공하도록 요구합니다.[306] 2023년 4월 ICO는 어린이 데이터를 오용한 틱톡에 1,270만 파운드의 벌금을 부과했습니다.[307][308]

조사 보류 중

텍사스

2022년 2월, 켄 팩스턴(Ken Paxton) 현 텍사스 법무장관은 어린이의 사생활 침해 및 인신매매 촉진 혐의로 틱톡(TikTok)에 대한 조사를 시작했습니다.[309][310] 팩스턴은 텍사스 공공안전국이 멕시코 전역에 사람이나 물건을 밀수하기 위해 청소년들을 모집하는 시도를 보여주는 여러 콘텐츠를 모았다고 주장했습니다.미국 국경입니다. 그는 그 증거가 회사가 "인질 밀수, 성매매, 마약 밀매"에 연루되었다는 것을 증명할 수도 있다고 주장했습니다. 회사는 플랫폼에서 어떤 종류의 불법 행위도 지원되지 않는다고 주장했습니다.[311]

캐나다 프라이버시 커미셔너

2023년 2월, 캐나다의 개인정보 보호위원회는 앨버타, 브리티시 컬럼비아 및 퀘벡의 개인정보 보호위원회와 함께 틱톡의 데이터 수집 관행에 대한 조사를 시작했습니다.[312]

유럽 위원회

2024년 2월, 유럽연합 집행위원회는 틱톡에 대해 어린이를 겨냥한 콘텐츠와 광고 투명성과 관련된 디지털 서비스법(DSA) 위반 가능성에 대한 조사를 시작했습니다.[313]

호주정보위원조회

2023년 12월, 호주 정보 위원국은 틱톡이 호주 개인 정보 보호법을 위반했다는 주장이 제기된 가운데 호주 시민에 대한 데이터 수집에 대한 조사를 발표했습니다.[314]

논란거리

사이버 불링

복스는 2018년에 다른 플랫폼에 비해 틱톡에서 괴롭힘과 트롤이 상대적으로 드물었다고 언급했습니다.[216] 그럼에도 불구하고 몇몇 사용자들은 팔로워들과 상호작용하는 데 사용되는 Duet 또는 React와 같은 기능을 통해 사이버 괴롭힘을 보고했습니다.[315] 자폐증을 조롱하는 유행이 결국 플랫폼 자체에서도 큰 반발을 일으켰고, 결국 회사는 해시태그를 아예 삭제했습니다.[316][317] 자녀들이 종종 공포에 질려 있는 장애인들에게 어떻게 반응하는지를 촬영한 부모들은 능력주의에 대한 비판으로 이어졌습니다.[318] 2019년 12월, 독일 디지털 권리 단체 netzpolitik.org 의 보고서에 따라 틱톡은 사이버 폭력을 제한하기 위한 일시적인 노력으로 장애인 사용자뿐만 아니라 LGBTQ+ 사용자의 비디오를 억압했다고 인정했습니다.

중독과 정신건강

일부 사용자들이 틱톡 사용을 중단하기 어려울 수 있다는 우려가 나오고 있습니다.[320] 2018년 4월, 두인에 중독 감소 기능이 추가되었습니다.[320] 이를 통해 사용자는 90분마다 휴식을 취하도록 권장했습니다.[320] 이후 2018년에 이 기능은 틱톡 앱에 출시되었습니다. 틱톡은 인기 인플루언서를 활용해 시청자들에게 앱 사용을 중단하고 휴식을 취하도록 유도합니다.[321]

많은 사람들이 콘텐츠의 짧은 형태 특성으로 인해 앱이 사용자의 주의 지속 시간에 영향을 미치는 것에 대해 우려했습니다. 많은 틱톡 시청자들이 아직 두뇌가 발달 중인 어린 아이들이기 때문에 이것은 우려스러운 일입니다.[322] TikTok 경영진과 대표는 플랫폼의 광고주들에게 사용자들의 주의 집중 시간이 좋지 않다는 것을 언급하고 이를 알렸습니다. 이 회사의 조사에 따르면 소셜 미디어 사용자의 거의 50%가 1분 이상 비디오를 보는 것을 스트레스로 생각하고 사용자의 3분의 1이 두 배의 속도로 비디오를 시청한다고 합니다. 짧은 주의 집중 시간은 틱톡이 더 긴 콘텐츠 형식으로 전환하는 데 어려움을 겪었습니다.[207] 틱톡은 또한 아이들이 다른 사용자들에게 보낼 수 있는 코인을 구매할 수 있도록 하여 비판을 받았습니다.[323]

2022년 2월, 월스트리트 저널은 "전국의 정신 건강 전문가들이 성적인 틱톡 비디오를 게시하는 것이 십대 소녀들에게 미치는 영향에 대해 점점 더 우려하고 있습니다."라고 보도했습니다.[324] 2022년 3월, 미국 주 검찰총장 연합은 틱톡이 어린이의 정신 건강에 미치는 영향에 대한 조사를 시작했습니다.[325] 2022년 6월, 틱톡은 최대 중단 없는 화면 시간 허용을 설정할 수 있는 기능을 도입했으며, 그 후 앱은 피드를 탐색하는 기능을 차단합니다. 블록은 앱이 종료되고 설정된 시간 동안 사용되지 않은 상태로 방치된 후에만 상승합니다. 또한 앱에는 앱이 열리는 빈도, 브라우징에 소요되는 시간 및 브라우징이 발생하는 시기에 대한 통계가 포함된 대시보드가 있습니다.[326]

2021년 이후 자살, 자해 또는 섭식장애와 관련된 내용을 다루는 계정이 더 유사한 영상을 보여준 것으로 보고되었습니다. 일부 사용자는 코드로 작성하거나 파격적인 철자를 사용하여 틱톡 필터를 우회할 수 있었습니다. 회사는 부당한 사망과 관련된 여러 소송에 직면했습니다. 틱톡은 이와 유사한 권고의 '토끼 구멍'을 해체하기 위해 노력하고 있다고 밝혔습니다. 미국의 섭식 장애 검색은 정신 건강 자원을 제공하는 프롬프트를 받습니다.[327][328][329]

2021년에 플랫폼은 청소년들이 취침 시간 이후에 알림을 받는 것을 방지하는 기능을 도입할 것이라고 밝혔습니다. 회사는 13세에서 15세 사이의 사용자에게 오후 9시 이후에는 푸시 알림을 더 이상 보내지 않을 것입니다. 16~17세의 경우 오후 10시 이후에는 알림이 발송되지 않습니다.[330] 2023년 3월, 틱톡은 18세 미만 사용자에 대한 기본 화면 제한을 발표했습니다.[331]

월스트리트 저널은 투렛 증후군을 가진 콘텐츠 제작자들의 틱톡 동영상이 증가하는 것과 관련하여 의사들이 틱톡 사례의 급증을 경험했다고 보도했습니다. 의사들은 다양한 틱을 보여주는 콘텐츠를 소비한 사용자들이 집단 심인성 질환과 [332]유사하게 자신만의 틱을 개발하는 경우가 있기 때문에 그 원인이 사회적인 것일 수 있다고 제안했습니다.[333][334]

2022년 의약품 부족

2022년 11월, 호주의 의료 규제 기관인 TGA(Terapeutic Goods Administration)는 당뇨병 치료제 오젬픽(Ozempic)이 전 세계적으로 부족하다고 보고했습니다. TGA에 따르면 수요 증가는 체중 감량 목적의 의약품의 허가 외 처방이 증가했기 때문입니다.[335] 2022년 12월, 미국도 품귀 현상을 겪고 있는 가운데, 이 약에 대한 수요가 크게 증가한 것은 틱톡의 체중 감소 추세로 인해 약에 대한 동영상이 3억 6천만 뷰를 돌파했기 때문이라고 보고되었습니다.[336][337][338] 비만 치료를 위해 특별히 승인된 약물인 웨고비(Wegovy)도 일론 머스크가 체중 감량에 도움을 준 것으로 인정한 후 플랫폼에서 인기를 얻었습니다.[339][340]

작업장조건

이 회사의 몇몇 전직 직원들은 중국 시간대에 협력하기 위해 일요일 주중에 시작하는 것과 과도한 업무량을 포함한 열악한 직장 환경을 주장했습니다. 직원들은 일주일에 평균 85시간의 회의 시간을 가지며 종종 밤을 새워 일을 완성한다고 말했습니다. 일부 직원들은 사업장의 일정이 996 일정과 유사하게 운영된다고 주장했습니다. 회사는 주 5일(주 63시간) 오전 10시부터 오후 7시까지 근무한다는 방침을 명시하고 있지만 직원들은 근무시간 외 근무를 권장하고 있다고 언급했습니다. 한 여성 근로자는 회사가 여성 위생 제품을 바꾸는 데 시간을 충분히 주지 않았다고 불평했습니다. 또 다른 직원은 회사에서 일하는 것이 그녀가 결혼 치료를 받고 건강하지 않은 양의 체중을 감량하게 만들었다고 언급했습니다.[341] 이 같은 의혹에 대해 회사 측은 직원들의 '지원과 유연성'을 허용하는 데 전념하고 있다고 밝혔습니다.[342][343]

이스라엘-팔레스타인 분쟁

페이스북과 트위터와 같은 플랫폼이 콘텐츠를 차단한 후 팔레스타인인들이 자신들의 대의를 홍보하기 위해 틱톡에 의존했다는 보도와 [344]함께 이스라엘 분석가 요니 벤 메나켐은 이 앱을 이스라엘인에 대한 폭력을 선동하는 "위험한 영향력의 도구"라고 불렀습니다.[345][346] Ynet에 따르면, 팔레스타인의 무장 단체인 라이온스 덴은 틱톡을 통해 많은 인기를 얻었습니다.[347] 2023년 2월, 오츠마 예후디트 정치인 알모그 코헨은 동예루살렘 전체에 대한 틱톡 차단을 주장했습니다.[348]

타임스오브이스라엘에 따르면 2023년 하마스가 주도한 이스라엘 공격 이후 회사의 반유대주의가 '폭동'해 플랫폼에서 반유대인 및 반이스라엘 콘텐츠가 증가할 수 있었습니다.[349] 사차 바론 코헨, 데브라 메싱, 에이미 슈머, 틱톡 크리에이터 미리암 에자귀 등 유명 유대인들은 틱톡의 운영 책임자인 아담 프레셔와 사용자 운영 글로벌 책임자인 세스 멜닉 모두 유대인이라고 문제를 제기했습니다.[350]

틱톡을 금지하려는 미국 의원들은 이 플랫폼이 친(親) 하마와 친(親)팔레스타인 콘텐츠를 밀어붙이고 있다고 비난했습니다. 틱톡은 사용자 기반에 미국 이외의 지역도 포함되어 있으며, 해시태그는 조회수와 연령 차이로 인해 직접 비교할 수 없다고 밝혔습니다. 친팔레스타인 콘텐츠의 인기는 또한 앱의 젊은 사용자 기반에 의해 설명되었으며, 이는 이스라엘에서 팔레스타인으로 공감을 전환했습니다.[351][352]

뉴아랍에 따르면 북미 유대인 연맹은 틱톡 금지에 대한 지지를 표명했고, 이스라엘 비판론자들은 "이스라엘의 만행"을 비난하는 데 사용된 틱톡을 포함한 "친팔레스타인 목소리의 범죄화"를 비난했습니다.[353] 틱톡은 말레이시아의 파미 파질 통신부 장관도 친팔레스타인 콘텐츠를 탄압했다고 비난했습니다. 이 회사는 하마스를 칭찬하는 것을 금지하고 775,000개 이상의 비디오와 14,000개의 라이브 스트림을 제거했다고 밝혔습니다.[354][355]

2023년 11월, 오사마 빈 라덴의 2002년 "미국 국민에게 보내는 편지"는 틱톡과 다른 소셜 미디어에서 널리 퍼졌습니다. 그는 서한에서 미국과 이스라엘에 대한 미국의 지지를 비난하고 알카에다의 미국에 대한 전쟁을 방어적인 투쟁으로 지지했습니다. 미국인을 포함한 수많은 소셜 미디어 사용자들은 다시 등장한 편지 사본과 그 내용을 공유함으로써 미국의 외교 정책에 반대한다는 입장을 표명했습니다. 가디언 웹사이트는 이 편지를 20년 이상 전시한 뒤 삭제했고, 틱톡은 이 편지를 담은 동영상을 삭제하기 시작했습니다.[356] 워싱턴 포스트의 보도에 따르면 이 편지의 독성은 언론 보도 이전에 제한적이었으며 틱톡에서는 유행한 적이 없다고 합니다. 편지를 다루는 많은 틱톡 영상들은 빈 라덴에 대해 비판적이었고, 언론 보도는 편지의 폭력성을 높이면서 그 중요성을 과장했습니다.[357]

제한 및 금지

미국

2020년 1월, 미국 육군과 해군은 국방부가 틱톡을 보안 위험으로 분류한 후 정부 장치에 틱톡을 금지했습니다. 채용 담당자들은 할당량을 채우기 위해 앱을 사용해 왔으며, 일부는 개인 계정을 통해 참여 수준을 계속 유지하고 있습니다.[360][361][362]

뉴욕타임즈의 2020년 기사에 따르면, 중앙정보국 분석가들은 중국 정부가 앱에서 사용자 정보를 얻을 수 있지만 그렇게 했다는 증거는 없다고 판단했습니다.[363]

연방급

2020년 8월 6일, 당시 미국 대통령 도널드 트럼프는 틱톡이 바이트댄스에 의해 판매되지 않을 경우 45일 만에 거래를 금지하는 명령에[364][365] 서명했습니다.[366][367]

2020년 8월 14일, 트럼프는 바이트댄스에게 미국 틱톡 사업을 매각하거나 분사할 수 있는 90일의 시간을 부여하는 또 다른 명령을[368] 내렸습니다.[369] 트럼프 대통령은 이 명령에서 바이트댄스가 "미국의 국가 안보를 위협하는 행동을 취할 수도 있다"고 믿게 만드는 "신뢰할 수 있는 증거"가 있다고 말했습니다.[370] 도널드 트럼프는 틱톡의 모회사가 미국 사용자 데이터를 가져다가 바이트댄스라는 회사를 통해 중국 사업장에 다시 보고한다는 소문이 돌면서 틱톡이 위협이 될 것을 우려했습니다.[371]

2021년 6월, 조 바이든 신임 대통령은 틱톡에 대한 트럼프 행정부의 금지를 취소하는 행정명령에 서명하고 대신 상무부 장관에게 앱이 미국 국가 안보에 위협이 되는지 확인하기 위해 조사하도록 명령했습니다.[372]

12월 27일, 미국 하원의 최고 행정 책임자는 하원이 관리하는 모든 장치에서 틱톡을 금지했습니다.[373]

2022년 12월 30일, 조 바이든 대통령은 No Tik에 서명했습니다.Tokon Government Device Act, 일부 예외를 제외하고 연방 정부가 소유한 장치에서 앱을 사용하는 것을 금지합니다.[374]

2024년 3월 13일, 미국 하원은 H.R. 7521을 통과시켰는데, 이는 틱톡이 바이트댄스로부터 매각되지 않는 한 완전히 금지하는 것이었습니다.[375] 그 법안은 상원의 조치에 계류 중입니다.[10][376]

국가급

2023년 2월 현재 최소 32개(50개 중)의 주 정부 기관, 직원 및 계약자가 정부 발행 장치에서 틱톡을 사용하는 것에 대한 금지를 발표하거나 제정했습니다. 주정부의 금지는 공무원에게만 영향을 미치며 민간인이 개인 기기에 앱을 설치하거나 사용하는 것을 금지하지 않습니다.[377][378]

해설

비평가들은 미국 자체가 FISA 법에 따라 기술 회사를 통해 해외에 있는 개인들을 감시한다고 말합니다.[379] 틱톡과 다른 소셜 네트워크에서 수집한 데이터는 이미 다른 수단을 통해 구매할 수 있습니다.[379][380] 만약 통과된다면, H.R. 7521은 미국의 인터넷 회사들에 대한 권위주의적인 검열을 대담하게 만들 수 있고, 미국의 이익, 명성, 그리고 온라인 연설에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[381] 틱톡에 대한 중국 정부의 데이터 수집이나 영향력 캠페인에 대한 명확한 공개 증거는 없습니다.[278]

파트너십

2021년 4월 아부다비 문화관광부는 틱톡과 제휴를 맺고 도시 관광 활성화를 추진했습니다.[382] 2021년 1월 아랍에미리트 정부 미디어 사무소와의 겨울 캠페인 이후에 이루어졌습니다.[383]

2023년 6월 뉴질랜드 헤럴드는 뉴질랜드 및 호주 경찰과 협력하여 작업한 틱톡이 몽렐 몹, 블랙 파워, 킬러 비즈, 코만체로스, 몽골 및 반군을 포함한 범죄 조직과 관련된 340개의 계정과 2,000개의 비디오를 삭제했다고 보도했습니다. 틱톡은 앞서 조직적인 범죄 단체들이 갱 생활 방식과 싸움을 홍보하는 콘텐츠를 진행해 비난을 받은 바 있습니다. 틱톡 대변인은 "폭력적"이고 "혐오스러운" 조직의 콘텐츠에 대응하고 경찰과 협력하기 위한 플랫폼의 노력을 거듭 강조했습니다. 뉴질랜드 경찰청장 앤드류 코스터는 이 플랫폼이 갱단에 대해 "사회적으로 책임 있는 입장"을 취하고 있다고 칭찬했습니다.[384]

틱톡은 히스패닉 헤리티지 재단과 파트너십을 맺고 라틴계 소규모 기업을 지원하고 있으며, 기업가 정신에 따라 40명의 보조금 수혜자에게 각각 5,000달러를 적립하고 있습니다.[385]

올림픽 디지털 광고 규정이 완화된 후 틱톡과 팀 GB는 2024년 하계 올림픽을 위해 영국 선수들이 새로운 관객들과 연결할 수 있도록 후원 계약을 체결했습니다.[386]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 동성 결혼과 같은 주제에 대해서는 엄격하게 법적 설명자를 여전히 사용할 수 있습니다.

참고문헌

- ^ "TikTok – Make Your Day". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "抖音". App Store. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Lin, Pellaeon (22 March 2021). "TikTok vs Douyin: A Security and Privacy Analysis". Citizen Lab. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (1 July 2021). "TikTok is rolling out longer videos to everyone". The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Fung, Brian (12 March 2024). "TikTok creators fear a ban as the House prepares to vote on a bill that could block the app in America". CNN.

For You page makes it far easier for brands like August to reach new audiences compared to other apps, Okamoto said. Its recommendation algorithm is far better at expanding users' horizons and helping them to discover new creators

- ^ Carman, Ashley (29 April 2020). "TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads". The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "TikTok surpasses Google as most popular website of the year, new data suggests". NBC News. 22 December 2021. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Miltsov, Alex (2022). "Researching TikTok: Themes, Methods, and Future Directions". The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods: 664–676. doi:10.4135/9781529782943.n46. ISBN 9781529720969.

Even though TikTok is only a few years old, it has already been shaping the ways millions of people interact online and engage in artistic, cultural, social, and political activities.

- ^ a b Maheshwari, Sapna; Holpuch, Amanda (12 December 2023). "Why Countries Are Trying to Ban TikTok". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b Peterson, Kristina; Volz, Dustin; Andrews, Natalie (15 March 2024). "TikTok's Fate Now Hinges on the Senate". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ McDonald, Joe; Soo, Zen (24 March 2023). "Why does US see Chinese-owned TikTok as a security threat?". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ Campo, Richard (24 July 2023). "Is TikTok a national security threat?". Chicago Policy Review. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Shead, Sam (8 October 2020). "What a TikTok exec told the British government about the app that we didn't already know". CNBC. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ a b Goujard, Clothilde (22 March 2023). "What the hell is wrong with TikTok?". Politico. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Beijing takes stake, board seat in ByteDance's key China entity – The Information". Reuters. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ "China state firms invest in TikTok sibling, Weibo chat app". Associated Press News. 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "Fretting about data security, China's government expands its use of 'golden shares'". Reuters. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ a b Baker-White, Emily (16 March 2023). "The FBI And DOJ Are Investigating ByteDance's Use Of TikTok To Spy On Journalists". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ Baker-White, Emily (11 March 2022). "Inside Project Texas, TikTok's Big Answer To US Lawmakers' China Fears". Buzzfeed News. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Rodriguez, Salvador (25 June 2021). "TikTok insiders say social media company is tightly controlled by Chinese parent ByteDance". CNBC. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "The App That Launched a Thousand Memes Sixth Tone". Sixth Tone. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Is Douyin the Right Social Video Platform for Luxury Brands? Jing Daily". Jing Daily. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Graziani, Thomas (30 July 2018). "How Douyin became China's top short-video App in 500 days". WalktheChat. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "8 Lessons from the rise of Douyin (Tik Tok) · TechNode". TechNode. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "TikTok is owned by a Chinese company. So why doesn't it exist there?". CNN. 24 March 2023. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Forget The Trade War. TikTok Is China's Most Important Export Right Now". BuzzFeed News. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Niewenhuis, Lucas (25 September 2019). "The difference between TikTok and Douyin". SupChina. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "TikTok's Rise to Global Markets". hbsp.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Tik Tok, a Global Music Video Platform and Social Network, Launches in Indonesia". Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Lin, Liza; Winkler, Rolfe (9 November 2017). "Social-Media App Musical.ly Is Acquired for as Much as $1 Billion". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Social video app Musical.ly acquired for up to $1 billion". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Lee, Dami (2 August 2018). "The popular Musical.ly app has been rebranded as TikTok". Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Musical.ly Is Going Away: Users to Be Shifted to Bytedance's TikTok Video App". MSN. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Kundu, Kishalaya (2 August 2018). "Musical.ly App To Be Shut Down, Users Will Be Migrated to TikTok". Beebom. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "Tik Tok, Global Short Video Community launched in Thailand with the latest AI feature, GAGA Dance Machine The very first short video app with a new function based on AI technology". thailand.shafaqna.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (29 April 2020). "TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads". The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Yurieff, Kaya (21 November 2018). "TikTok is the latest social network sensation". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (15 November 2018). "TikTok surges past 6M downloads in the US as celebrities join the app". The Verge. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (20 November 2018). "TikTok App Nears 80 Million U.S. Downloads After Phasing Out Musical.ly, Lands Jimmy Fallon as Fan". Variety. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "A-Rod & J.Lo, Reese Witherspoon and the Rest of the A-List Celebs You Should Be Following on TikTok". People. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Yuan, Lin; Xia, Hao; Ye, Qiang (16 August 2022). "The effect of advertising strategies on a short video platform: evidence from TikTok". Industrial Management & Data Systems. 122 (8): 1956–1974. doi:10.1108/IMDS-12-2021-0754. ISSN 0263-5577. S2CID 251508287. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "The NFL joins TikTok in multi-year partnership". TechCrunch. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "50 TikTok Stats That Will Blow Your Mind in 2020 [UPDATED ]". Influencer Marketing Hub. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "TikTok Names ByteDance CFO Shou Zi Chew as New CEO". NDTV Gadgets 360. May 2021. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "TikTok CEO Kevin Mayer quits after 4 months". Fortune (magazine). Bloomberg News. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (18 May 2020). "In surprise move, a top Disney executive will run TikTok". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "Australian appointed interim chief executive of TikTok". ABC News. 28 August 2020. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (27 September 2021). "TikTok says it has passed 1 billion users". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "The all-conquering quaver". The Economist. 9 July 2022. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Belanger, Ashley (12 October 2022). "TikTok wants to be Amazon, plans US fullfillment centers and poaches staff". ArsTechnica. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Criddle, Cristina; McGee, Patrick (26 October 2022). "TikTok to launch standalone gaming channel". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Lee, Alexander (3 November 2022). "TikTok denies plans for an ad-driven gaming tab as it works to embrace the gaming community". Digiday. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Brands increase TikTok spending despite threat of US ban". Financial Times. 2023. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Wells, Meghan Bobrowsky and Georgia. "TikTok's American Growth Is Already Stalling". WSJ. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Primack, Dan (2024). "Congress is cracking down on TikTok because CFIUS hasn't". Axios. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Chen, Qian (19 September 2018). "The biggest trend in Chinese social media is dying, and another has already taken its place". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "How Douyin became China's top short-video App in 500 days – WalktheChat". WalktheChat. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "TikTok Pte. Ltd". Sensortower. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Rayome, Alison DeNisco. "Facebook was the most-downloaded app of the decade". CNET. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Chen, Qian (18 September 2018). "The biggest trend in Chinese social media is dying, and another has already taken its place". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ "TikTok surpassed Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat & YouTube in downloads last month". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ Novet, Jordan (13 September 2020). "Oracle stock surges after it confirms deal with TikTok-owner ByteDance". CNBC. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

Shares of Oracle surged Monday morning after it confirmed it has been chosen to serve as TikTok owner ByteDance's "trusted technology provider" in the U.S.

- ^ Kharpal, Arjun (25 September 2020). "Here's where things stand with the messy TikTok deal". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "TikTok signs deal with Sony Music to expand music library". Yahoo! Finance. 2 November 2020. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Warner Music Group inks licensing deal with TikTok". Music Business Worldwide. 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Warner Music signs with TikTok as more record companies jump on social media bandwagon". themusicnetwork.com. 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "How TikTok broke social media". The Economist. 21 March 2023. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "TikTok to market Iranian products in China: TCCIM – Mehr News Agency". Mehr News Agency. 2 July 2023. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Wells, Georgia (27 September 2023). "TikTok Employees Say Executive Moves to U.S. Show China Parent's Influence". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

The TikTok employees say they are worried that the appointments show ByteDance plays a greater role in TikTok's operations than TikTok has disclosed publicly.

- ^ Shepardson, David (3 October 2023). "US senators examine TikTok hiring of ByteDance executives". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ Park, Kate (11 December 2023). "TikTok to invest $1.5B in GoTo's Indonesia e-commerce business Tokopedia". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "TikTok Ban Bill Spotlights Open Secret: App Loses Money". The Information. 13 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b Murray, Conor (13 March 2023). "TikTok Clones: How Spotify, Instagram, Twitter And More Are Copying Features Like The 'For You' Page". Forbes. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Sato, Mia (12 September 2022). "Instagram knows it has a Reels problem". The Verge. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Silberling, Amanda (14 December 2021). "Snap paid $250 million to creators on its TikTok clone this year". Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Facebook paid GOP firm to malign TikTok". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 17 September 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Wells, Georgia (17 March 2023). "Silicon Valley and Capitol Hill Build an Anti-China Alliance". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "TikTok, X, and Meta CEOs to Face Congressional Hearing Over Child Sexual Exploitation". Rolling Stone. 20 November 2023. Archived from the original on 21 November 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "How to Use TikTok: Tips for New Users". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Matsakis, Louise (6 March 2019). "How to Use TikTok: Tips for New Users". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ a b Cervi, Laura (3 April 2021). "Tik Tok and generation Z". Theatre, Dance and Performance Training. 12 (2): 198–204. doi:10.1080/19443927.2021.1915617. ISSN 1944-3927. S2CID 236323384. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Ovide, Shira (3 June 2020). "TikTok (Yes, TikTok) Is the Future". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Matsakis, Louise. "How TikTok's 'For You' Algorithm Actually Works". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Scalvini, Marco (April 2023). "Making Sense of Responsibility: A Semio-Ethic Perspective on TikTok's Algorithmic Pluralism". Social Media + Society. 9 (2). doi:10.1177/20563051231180625. ISSN 2056-3051.

- ^ a b "TikTok adds video reactions to its newly-merged app". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "Tik Tok lets you duet with yourself, a pal, or a celebrity". The Nation. 22 May 2018. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Weir, Melanie. "How to duet on TikTok and record a video alongside someone else's". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Liao, Christina. "How to make and find drafts on TikTok using your iPhone or Android". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b "It's time to pay serious attention to TikTok". TechCrunch. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Delfino, Devon. "How to 'go live' on TikTok and livestream video to your followers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "How To Go Live & Stream on TikTok". Tech Junkie. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "TikTok gives parent remote control of child's app". BBC News. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "TikTok adds educational resources for parents as part of its Family Pairing feature". TechCrunch. September 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Keck, Catie (28 October 2021). "TikTok is testing a new tipping feature for some creators". TheVerge. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Porter, Jon (16 December 2021). "TikTok tests PC game streaming app that could let it take on Twitch". The Verge. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Roth, Emma (20 December 2021). "TikTok's new Live Studio app allegedly violates OBS' licensing policy". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (4 May 2022). "TikTok will start to share ad revenue with creators". The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "TikTok a lancé un nouveau service payant pour concurrencer Spotify et Deezer". Capital. 13 July 2023. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Weatherbed, Jess (19 July 2023). "TikTok Music beta expands to more countries". The Verge. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Weatherbed, Jess (1 February 2024). "TikTok loses Taylor Swift, Drake, and other major Universal Music artists". The Verge. Archived from the original on 1 February 2024. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Universal Music warns it will pull songs from TikTok". techxplore.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "How Does Tik Tok Outperform Tencent's Super App WeChat and Become One of China's Most Popular Apps? (Part 1)". kr-asia.com. 26 March 2018. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Maheshwari, Sapna (24 June 2023). "TikTok Is Our DJ Now. It's Playing a Lot of Meghan Trainor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ "TikTok Star Charli D'Amelio Officially Leaves the Hype House". People. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Coscarelli, Joe (9 May 2019), "How Lil Nas X Took 'Old Town Road' From TikTok Meme to No. 1 Diary of a Song", The New York Times, archived from the original on 10 November 2019, retrieved 26 November 2019

- ^ Koble, Nicole (28 October 2019). "TikTok is changing music as you know it". British GQ. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Leskin, Paige (22 August 2019). "The life and rise of Lil Nas X, the 'Old Town Road' singer who went viral on TikTok and just celebrated Amazon Prime Day with Jeff Bezos". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (10 May 2019). "TikTok Is the New Music Kingmaker, and Labels Want to Get Paid". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "'Any Song' is a viral hit thanks to TikTok challenge: Rapper Zico's catchy song and dance have become a craze all around the world". koreajoongangdaily.joins.com. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ McCathie, William (23 April 2020). "Say So, TikTok, and the 'Viral Sleeper Hit'". Cherwell. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Wass, Mike (14 July 2022). "Viral Revivals: From Kate Bush to Tom Odell, Inside the Business of Oldies as New Hit Songs". Variety. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "How TikTok Gets Rich While Paying Artists Pennies". Pitchfork. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Khomami, Nadia (28 June 2023). "'TikTok is age-agnostic': how Kylie and Fleetwood Mac found new young fans". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "TikTok Teens and K-Pop Stans Say They Sank Trump Rally". The New York Times. 21 June 2020. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "The President's Shock at the Rows of Empty Seats in Tulsa". The New York Times. 21 June 2020. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Morin, Rebecca. "Young and progressive voters aren't just 'settling for Biden' anymore; they're going all in". USA Today. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Ward, Ian (27 March 2022). "Inside the Progressive Movement's TikTok Army". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Latu, Dan (10 November 2021). "They started making TikToks for Joe Biden. Now Gen Z For Change wants to wield real political clout". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Felicia (21 November 2020). "Presenting: The Official (Fake) Ratatouille Playbill". Playbill. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Pelletiere, Nicole (17 September 2021). "15-year-old student's arrest linked to banned TikTok challenge after police locate video of crime". Fox News. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ ""Devious Licks" TikTok challenge leaving bathrooms plundered in many schools across the nation". minnesota.cbslocal.com. 17 September 2021. Archived from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Joelle (16 September 2021). "What to Know About the 'Devious Lick' TikTok Challenge — and Why Schools are Warning Parents". People. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Day, Andrea; DiLella, Chris (8 September 2022). "TikTok challenge spurs rise in thefts of Kia, Hyundai cars". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Hyundai and Kia Launch Service Campaign to Prevent Theft of Millions of Vehicles Targeted by Social Media Challenge NHTSA". www.nhtsa.gov. 14 February 2023. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J. (18 May 2023). "Hyundai and Kia agree to $200 million settlement over TikTok car theft challenge". The Verge. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Chong, Linda (12 August 2023). "They act like video game characters on TikTok. It nets $200 an hour". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Melody Tsui (6 August 2019). "What is Douyin, aka TikTok, and why are stars like Angelababy and Ouyang Nana on it?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "A young Qatari man leads the trend in China and becomes the most famous in it.. What is the story?" شاب قطري يتصدر الترند في الصين ويصبح الأكثر شهرة فيها.. ما القصة؟ (in Arabic). Al Jazeera. 24 November 2022. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Dorothy Kam (3 December 2022). "Royal teen at World Cup goes viral in China as 'dumpling wrapper prince'". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Lorenz, Taylor (24 May 2021). "TikTok, the Fastest Way on Earth to Become a Food Star". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ a b "TikTok brings unexpected success for food, beverage industry". SmartBrief. 29 June 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ "Usage of Hashtag". ❤️ Pimpmyacc. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Torres, Maria (25 January 2021). Teaching Nutrition Education and Cooking Self-Efficacy Through TikTok Videos: A Pilot Study (Thesis thesis). California State University, Northridge.

- ^ Hülsing, G. M. (25 June 2021). "#Triggerwarning: Body Image: A qualitative study on the influences of TikTok consumption on the Body Image of adolescents". essay.utwente.nl. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ King, Mac (4 March 2021). "Viral TikTok video recipe prompts feta cheese shortage". FOX 5 NY. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Moore, Cortney (24 May 2021). "TikTok's 'pesto eggs' are the latest food trend: 'You won't go back'". Fox News. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Weiss, Sabrina (5 October 2021). "This Viral Salmon Rice Bowl Recipe Is Taking Over TikTok Thanks to One Surprising Ingredient". People. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "We made the TikTok-famous pesto eggs and we're hooked". TODAY.com. 8 October 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Paton, Elizabeth (4 February 2023). "The Mean Life of a 'Midsize' Model". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ Allaire, Christian (21 February 2021). "This Curve Model Does Realistic Clothing Hauls on TikTok". Vogue. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ Dube, Rachel (11 October 2021). "What is mid-size fashion? Experts explain the TikTok trend". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ Das, Rishub K.; Drolet, Brian C. (December 2021). "Plastic Surgeons in TikTok: Top Influencers, Most Recent Posts, and User Engagement". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 148 (6): 1094e–1097e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008566. ISSN 0032-1052. PMID 34705755. S2CID 240074110. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Bushak, Lecia (11 November 2022). "TikTok's most popular plastic surgeon influencers". MM+M. Medical Marketing and Media. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Zitser, Joshua (10 January 2021). "Insider created a TikTok account and set the age at 14 to test how long before a plastic surgeon's promotional video appeared. It only took 8 minutes". Insider. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

The hashtag #nosejobcheck, which mainly consists of videos showcasing before-and-after clips of nasal surgery, has accumulated over one billion views on the platform. The hashtag #nosejob, which hosts similar videos, has over 1.6 billion views. There's even a unique 'nose job check' sound. Over 120,000 videos using this sound have been published on TikTok since last October.

- ^ Aviles, Gwen; Gopal, Trisha; Naftulin, Julia (23 March 2022). "Bella Hadid said she wished she still had 'the nose of her ancestors.' 'Ethnic nose jobs' are on the rise". Insider. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

In 2020, one of TikTok's biggest stars Charli D'Amelio shared her own nose job journey after receiving reconstructive surgery for what she deemed as "breathing problems" stemming from a broken nose.

- ^ Tenbarge, Kat (27 April 2022). "Young influencers are being offered cheap procedures in return for promotion. They say it's coming at a cost". NBC News. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Kalhan (20 December 2022). "Buccal fat removal videos have gone viral on TikTok. But some users prefer to embrace their natural, rounder faces". NBC News. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Ryu, Jenna (29 December 2022). "'Buccal fat removal': Who decided round cheeks were something to be insecure about?". USA Today. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Javaid, Maham (29 December 2022). "Where has all the buccal fat gone?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Sato, Mia (14 March 2023). "TikTok is adding a third feed just for science and math videos". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Malik, Aisha (14 March 2023). "TikTok is adding a dedicated feed for STEM content". Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Main, Nikki (13 March 2023). "TikTok Overrode Its Algorithm to Boost the World Cup and Taylor Swift". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Baker-White, Emily (20 January 2023). "TikTok's Secret 'Heating' Button Can Make Anyone Go Viral". Forbes. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Hern, Alex (25 September 2019). "Revealed: how TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

Notably absent from the list is Xi Jinping

- ^ a b Dodds, Laurence (12 July 2020). "Inside TikTok's dystopian Chinese censorship machine". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Handley, Erin (28 November 2019). "TikTok parent company complicit in censorship and Xinjiang police propaganda: report". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "TikTok apologises for deleting Feroza Aziz's video on plight of Muslim Uyghurs in China". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ a b Biddle, Sam; Ribeiro, Paulo Victor; Dias, Tatiana (16 March 2020). "Invisible Censorship – TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by "Ugly" People and the Poor to Attract New Users". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Hern, Alex (17 March 2020). "TikTok 'tried to filter out videos from ugly, poor or disabled users'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Hern, Alex (26 September 2019). "TikTok's local moderation guidelines ban pro-LGBT content". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ a b Hung, Allison; Rollet, Charles (3 January 2023). "Douyin Bans Pro-LGBT Content". IPVM. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ Sanchez, Kait (4 June 2021). "TikTok says the repeat removal of the intersex hashtag was a mistake". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Criddle, Cristina (12 February 2020). "Transgender users accuse TikTok of censorship". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ a b "TikTok and Douyin Explained". The Citizen Lab. 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Mueller, Miller; Farhat, Karim. "TikTok and US national security" (PDF). Internet Governance Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Roth, Emma (27 July 2022). "TikTok to provide researchers with more transparency as damaging reports mount". The Verge. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Ghaffary, Shirin (3 February 2023). "Behind the scenes at TikTok as it campaigns to change Americans' hearts and minds". The Verge. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ Maheshwari, Sapna (21 December 2023). "Topics Suppressed in China Are Underrepresented on TikTok, Study Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Maheshwari, Sapna (8 January 2024). "TikTok Quietly Curtails Data Tool Used by Critics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ a b Hadero, Haleluya (9 January 2024). "TikTok restricts tool used by researchers - and its critics - to assess content on its platform". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Hadero, Haleluya (9 January 2024). "TikTok restricts hashtag search tool used by researchers to assess content on its platform". NBC10 Philadelphia. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Matzko, Paul. "Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics: A Misleading Study Compares TikTok and Instagram". Cato Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Weimann & Masri (25 May 2020). "Research Note: Spreading Hate on TikTok". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 46 (5): 752–765. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027. S2CID 225776569. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "TikTok 'family safety mode' gives parents some app control". BBC News. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Stokel-Walker, Chris. "TikTok will make under-16s' accounts private by default to protect them from groomers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Tan, Arlene (23 November 2022). "Hate speech emerges on Malaysian TikTok as political uncertainty drags out". Arab News. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ Feuer, William (22 October 2019). "TikTok removes two dozen accounts used for ISIS propaganda". CNBC. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Wells, Georgia (23 October 2019). "Islamic State's TikTok Posts Include Beheading Videos". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Pope, Felix (2 March 2023). "TikTok is still hosting Nazi propaganda, despite warnings". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Gilbody-Dickerson, Claire (10 June 2021). "TikTok users lured into watching girl dance before video cuts to man's beheading". The Mirror. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ Haasch, Palmer. "TikTok removes a graphic video depicting a girl's beheading after users said they were 'traumatized' by the footage". Insider. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "TikTok tries to remove widely shared suicide clip". BBC News. 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ a b Dellinger, A. J. (22 June 2020). "Conspiracy theories are finding a hungry audience on TikTok". Mic. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Strapagiel, Lauren (27 May 2020). "COVID-19 Conspiracy Theorists Have Found A New Home On TikTok". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Kaplan, Alex (28 January 2020). "TikTok is hosting videos spreading misinformation about the coronavirus, despite the platform's new anti-misinformation policy". Media Matters for America. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Kalra, Aditya (7 April 2020). "India asks TikTok, Facebook to remove users spreading coronavirus misinformation". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Dickson, E.J. (13 May 2020). "On TikTok, COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories Flourish Amid Viral Dances". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b "TikTok's search suggests misinformation almost 20 percent of the time, says report". Mashable. 19 September 2022. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ "TikTok launches an in-app US midterms Elections Center, shares plan to fight misinformation". Newsroom TikTok. 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Misinformation Monitor: September 2022". NewsGuard. NewsGuard Technologies, Inc. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ "Shanmugam seeks court order requiring TikTok to name users who posted 'false, baseless' claims of extra-marital affair". TODAY. Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ a b Milmo, Dan (10 March 2022). "TikTok users in Russia can see only old Russian-made content". The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "TikTok suspends content in Russia in response to 'fake news' law". Techcrunch.com. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "TikTok suspends new posts in Russia due to the country's recent 'fake news' law". The Washington Post. London. 6 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Faddoul, Marc; Romano, Salvatore; Rama, Ilir; Kerby, Natalie; Giorgi, Giulia (13 April 2022). "Content Restrictions on TikTok in Russia following the Ukrainian War" (PDF). Tracking Exposed. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

cannot be solely attributed to TikTok's content restriction policies. The 'fake news' law ... is likely to have also increased the level of self-censorship ... likely to be a technical glitch ... these loopholes and tried to patch them

- ^ "Study finds TikTok's ban on uploads in Russia failed, leaving it dominated by pro-war content – TechCrunch". Techcrunch.com. 13 April 2022. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Russian state media is still posting to TikTok a month after the app blocked new content – TechCrunch". Techcrunch.com. 30 April 2021. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war: How TikTok fakes pushed Russian lies to millions". BBC News. 15 December 2023. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.