실리콘 밸리

Silicon Valley실리콘 밸리 | |

|---|---|

| 좌표:37°22°39°N 122°04′03§ W/37.3750°N 122.06750°W좌표: 37°22°39°N 122°04 0 03 w 37 / 37 . 37750 n N 122 . 06750、 . 、 - . | |

| 나라 | 미국 |

| 주 | 캘리포니아 |

| 지역 | 샌프란시스코 베이 에어리어 |

| 메가레지온 | 캘리포니아 북부 |

| 시간대 | UTC-8(태평양) |

| • 여름 (DST) | UTC-7(PDT) |

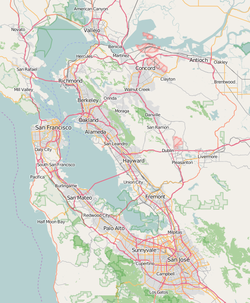

실리콘 밸리는 캘리포니아 북부에 있는 지역으로 첨단 기술과 혁신의 글로벌 중심지 역할을 합니다.샌프란시스코 만 구역의 남부에 위치하고 있으며, 대략적으로 San Mateo County, Santa Clara County 및 Alameda [1][2][3]County에 해당한다.San Jose는 실리콘 밸리에서 가장 큰 도시, 캘리포니아에서 세 번째로 큰 도시, 미국에서 10번째로 큰 도시입니다. 다른 실리콘 밸리의 주요 도시로는 Sunnyvale, Santa Clara, Redwood City, Mountain View, Palo Alto, Menlo Park, Cupertino 및 Fremont가 있습니다.브루킹스 [4]연구소에 따르면 새너제이 메트로폴리탄 지역은 1인당 GDP가 세계에서 세 번째로 높고(스위스 취리히와 노르웨이 오슬로에 이어), 2021년 6월 현재 미국에서 [5]100만 달러 이상의 가치가 있는 주택 비율이 가장 높다.

실리콘 밸리는 Fortune 1000에 속한 30개 이상의 기업 본사와 수천 개의 스타트업 기업을 포함한 세계 최대의 하이테크 기업들의 본거지입니다.실리콘 밸리는 또한 미국 내 벤처 캐피털 투자의 3분의 1을 차지하고 있으며, 이는 실리콘 밸리가 첨단 기술 혁신을 위한 선도적인 허브 및 스타트업 생태계가 되는 데 도움을 주고 있습니다.실리콘 기반의 집적회로, 마이크로프로세서, 마이크로컴퓨터가 개발된 것은 실리콘밸리에서였다.2021년 현재[update] 이 지역은 약 50만 명의 정보기술 근로자를 [6]고용하고 있다.

San Jose와 Santa Clara Valley, 그리고 Bay Area의 다른 두 주요 도시인 San Francisco와 Okland를 향해 북쪽으로 더 많은 하이테크 회사들이 설립됨에 따라, "Silicon Valley"라는 용어는 두 가지 정의를 가지게 되었습니다: Santa Clara County와 San Mateo County 남동부를 지칭하는 좁은 지리적 정의, 그리고 Metionomenomy.니션이란 베이 에리어 전체의 하이테크 비즈니스를 말합니다.실리콘 밸리라는 용어는 종종 미국의 첨단 기술 경제 부문을 위한 시네코체로 사용된다.이 이름은 또한 선도적인 첨단 기술 연구 및 기업들과 세계적인 대명사가 되었고, 따라서 비슷한 이름을 가진 장소들뿐만 아니라 전 세계 유사한 구조를 가진 연구 단지와 기술 센터에도 영감을 주었습니다.실리콘 밸리의 많은 기술 회사 본사가 관광 [7][8][9]명소가 되었다.최근 캘리포니아의 가뭄이 심해지면서 실리콘밸리 지역의 물 [10]안보가 더욱 악화되고 있다.

어원학

실리콘이라는 단어는 원래 실리콘 기반의 트랜지스터와 집적회로 칩을 전문으로 하는 지역의 많은 혁신가들과 제조업체들을 가리켰다.

그 이름의 대중화는 돈 회플러가 [1]한 것으로 알려져 있다.그는 1971년 1월 11일자 주간 무역신문 Electronic [11]News에 실린 "Silicon Valley USA" 기사에서 처음 그것을 사용했다.그러나 이 용어는 IBM PC와 수많은 관련 하드웨어 및 소프트웨어 제품이 소비자 시장에 소개된 1980년대 [1]초반까지 널리 사용되지 않았습니다.

역사

실리콘 밸리는 지역 대학에 있는 숙련된 과학 연구 기지, 풍부한 벤처 자본, 그리고 꾸준한 미 국방성 지출 등 여러 기여 요소들의 교차점을 통해 탄생했습니다.스탠포드 대학의 리더십은 계곡의 초기 개발에 특히 중요했습니다.이러한 요소들이 함께 그것의 [12]성장과 성공의 기초를 형성했다.

초기 군사 기원

베이 에리어는 오랫동안 미 해군의 연구와 기술의 주요 장소였다.1909년 찰스 헤롤드는 미국 최초의 라디오 방송국을 새너제이에서 정기적으로 편성했다.그해 말 스탠퍼드대를 졸업한 시릴 엘웰은 미국 폴센 아크 전파기술 특허를 사들여 팔로알토에 연방전신공사(FTC)를 설립했다.이후 10년 동안, FTC는 세계 최초의 글로벌 무선 통신 시스템을 만들었고 1912년 [13]해군과 계약을 맺었다.

1933년, 캘리포니아의 서니베일 공군기지는 미국 정부에 의해 격납고에 있는 USS 매콘을 수용하기 위한 해군 항공 기지(NAS)로 사용하기 위해 위탁되었다.이 기지는 NAS Moffett Field로 개명되었고 1933년에서 1947년 사이에 미 해군 비행선들이 그곳에 [14]기지를 두었다.

많은 기술 회사들이 해군에 봉사하기 위해 모펫 필드 주변 지역에 공장을 세웠다.해군이 비행선의 야망을 포기하고 서해안 운영의 대부분을 샌디에이고로 옮겼을 때, 국립항공자문위원회(NACA, NASA의 전신)는 항공 연구를 위해 모펫필드의 일부를 인수했다.원래 있던 회사들 중 많은 수가 남았고, 새로운 회사들이 입주했다.가까운 지역은 곧 1950년대부터 [15]1980년대까지 실리콘 밸리의 최대 고용주였던 록히드 같은 항공우주 회사들로 채워졌다.

스탠퍼드 대학의 역할

스탠포드 대학과 그 계열사, 졸업생들은 이 [16]분야의 발전에 큰 역할을 했다.실리콘 [citation needed]밸리의 부상과 함께 매우 강력한 지역적 연대감이 동반되었다.1890년대부터 스탠포드 대학의 지도자들은 이 사명을 (미국) 서부에 봉사하는 것으로 보고 그에 따라 학교를 만들었다.동시에, 동양의 이익의 손에 의한 서구의 착취는 자급자족적인 지역 산업을 건설하려는 지지자 같은 시도를 촉진시켰다.따라서 지역주의는 실리콘 밸리 [17]개발의 첫 50년[timeframe?] 동안 스탠포드의 이해와 이 지역의 첨단 기술 회사들의 이해 관계를 맞추는 데 도움을 주었다.

1946년부터 [18]스탠포드 대학의 공학부 학장이었던 프레드릭 터먼은 교직원과 졸업생들이 그들만의 회사를 설립하도록 격려했다.1951년 테르만은 스탠포드 산업단지(현재의 스탠포드 연구단지, 엘 카미노 리얼 남서쪽 페이지 밀 로드를 둘러싼 지역, 풋힐 고속도로를 넘어 아라스트라데로 로드에 이르는 지역)의 형성을 주도했다.이 곳에서 대학은 그 토지의 일부를 하이테크 [19]기업에 임대했다.터먼은 스탠포드 대학 캠퍼스에서 실리콘 밸리가 될 때까지 Hewlett-Packard, Varian Associates, Eastman Kodak, General Electric, Lockheed Corporation 및 기타 첨단 기술 회사들을 양성한 것으로 알려져[by whom?] 있습니다.

제2차 세계대전 이후 대학들은 귀국 [citation needed]학생들로 인해 엄청난 수요를 경험했다.1951년 스탠포드의 성장 요건에 대한 재정적 요구를 해결하고 졸업생들에게 지역 고용 기회를 제공하기 위해 프레데릭 터먼은 스탠포드의 땅을 스탠포드 산업단지(이후 스탠포드 연구단지)라는 이름의 오피스 파크로 임대할 것을 제안했습니다.리스는 하이테크 기업으로 한정되었다[by whom?].최초의 세입자는 1930년대 스탠포드 졸업생들이 군사용 레이더 부품을 만들기 위해 설립한 Varian Associates였습니다.테르만은 민간 기술 신생기업을 위한 벤처 캐피털도 찾았다.Hewlett-Packard는 주요 성공 사례 중 하나가 되었다.1939년 스탠포드 졸업생인 빌 휴렛과 데이비드 패커드에 의해 패커드의 차고에서 설립된 휴렛 패커드는 1953년 직후 스탠포드 연구단지로 사무실을 옮겼다.1954년 스탠포드는 회사의 정규직 직원들이 시간제로 대학에서 대학원 학위를 취득할 수 있도록 하기 위해 Honors Cooperative Program을 시작했습니다.초기 회사들은 비용을 충당하기 위해 학생 한 명당 등록금의 두 배를 지불하는 5년 약정에 서명했다.Hewlett-Packard는 세계에서 [20]가장 큰 개인용 컴퓨터 제조업체가 되었으며 1984년 최초의 주문형 서멀 드롭 잉크젯 프린터를 출시하면서 가정용 인쇄 시장을 혁신했습니다.다른 초기 입주자들로는 이스트만 코닥, 제너럴 일렉트릭, [21]록히드 등이 있었다.

실리콘의 부상

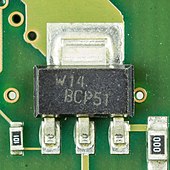

1956년, 최초의 작동 트랜지스터(존 바딘, 월터 하우저 브라테인)의 공동 발명자인 윌리엄 쇼클리는 팔로 알토에 있는 자신의 병든 어머니와 더 가까이 살기 위해 뉴저지에서 캘리포니아 마운틴 뷰로 이사했다.쇼클리의 작품은 수십 [22][23]년 동안 많은 전자 개발의 기초가 되었다.프레드릭 터먼과 윌리엄 쇼클리 둘 다 종종 "실리콘 [24][25]밸리의 아버지"라고 불린다.1953년 윌리엄 쇼클리는 바이폴라 트랜지스터의 발명에 대한 의견 차이로 벨 연구소를 떠났다.쇼클리는 캘리포니아 공과대학으로 잠시 복귀한 후 1956년 캘리포니아 마운틴뷰로 이사하여 쇼클리 반도체 연구소를 설립하였다.게르마늄을 반도체 물질로 사용한 다른 많은 연구자들과 달리 쇼클리는 실리콘이 트랜지스터를 만드는 데 더 좋은 물질이라고 믿었다.쇼클리는 현재의 트랜지스터를 새로운 3요소 설계(오늘날 쇼클리 다이오드라고 함)로 대체하려고 했지만, 그 설계는 "단순한" 트랜지스터보다 제작하기가 상당히 어려웠다.1957년 쇼클리는 실리콘 트랜지스터에 대한 연구를 중단하기로 결정했다.쇼클리의 학대적인 경영방식으로 인해 8명의 엔지니어가 회사를 떠나 페어차일드 세미컨덕터를 설립했습니다.쇼클리는 그들을 "배신자 8인"이라고 불렀습니다.Fairchild Semiconductor의 최초 직원 중 Robert Noyce와 Gordon Moore가 인텔을 [26][27]설립할 예정입니다.

1957년 벨 연구소의 모하메드 아탈라는 실리콘 표면을[31] 전기적으로 안정화시키고 표면의 [29]전자 상태 농도를 낮추는 열 산화에 [28][29][30]의한 실리콘 표면 패시베이션 공정을 개발했다.이로써 실리콘은 게르마늄의 전도성과 성능을 뛰어넘어 게르마늄을 대체하고 실리콘 반도체 [30][32][33]소자를 양산할 수 있는 발판을 마련했다.이로 인해 아탈라는 1959년 [34]동료 다원 칸과 함께 MOS 트랜지스터로도 알려진 MOSFET(금속 산화실리콘 전계효과 트랜지스터)를 발명하게 되었다.그것은 [35]다양한 용도로 소형화되고 대량 생산될 수 있는 최초의 진정한 콤팩트 트랜지스터였으며 실리콘 [32]혁명을 일으킨 것으로 알려져 있다.

MOSFET는 처음에는 Bell Labs에 의해 간과되고 무시되어 양극성 트랜지스터를 선호하게 되었고,[36] 이로 인해 Atalla는 Bell Labs에서 사임하고 1961년에 Hewlett-Packard에 합류하게 되었다.그러나 MOSFET는 RCA와 Fairchild Semiconductor에서 상당한 관심을 불러일으켰다.1960년 후반, Karl Zininger와 Charles Meuller는 RCA에서 MOSFET를 제작했고, Chih-Tang Sah는 Fairchild에서 MOS 제어 테트로드를 제작했습니다.이후 1964년 제너럴마이크로일렉트로닉스와 페어차일드가 MOS 소자를 상용화했다.[34]MOS 테크놀로지의 개발은 Fairchild나 Intel과 같은 캘리포니아의 스타트업 기업의 초점이 되어, 후에 실리콘 [37]밸리라고 불리게 되는 기술적, 경제적 성장을 촉진했습니다.

획일적인 집적 회로의 1959년 발명품에 이어(IC)로버트 노이스 페어차일드에서 모하메드 Atalla과 강대원에 의해 MOSFET(MOS트랜지스터) 벨 Labs,[34]Atalla에 먼저 1960,[35]를 확인해 보고 처음으로 상업적 금속 산화막 반도체 직접 회로 장군 마이크로에 의해 도입된 그 모스 집적 회로(모스 집적 회로)칩의 개념 제안된 반도체.전자1964년에 ics.[38]MOS IC의 개발은 컴퓨터의 중앙 처리 장치([39]CPU) 기능을 하나의 집적 [40]회로에 통합한 마이크로 프로세서의 발명으로 이어졌다.최초의 싱글칩 마이크로프로세서는 1971년 [39][42]인텔에서 Ted Hoff, Shima 마사토시, Stanley Mazor와 함께 Federico Faggin에 의해 설계되고 실현된 Intel 4004입니다.[41]1974년 4월 인텔은 인텔 8080을 [43]출시했습니다.이것은, 「컴퓨터 온 칩」, 「최초의 진정한 사용 가능한 마이크로프로세서」입니다.

인터넷의 기원

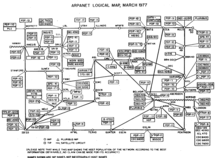

1963년 4월 23일, 국방부 ARPA의 정보처리기술사무소(IPTO)의 초대 책임자인 J. C. R. 릭라이더는 은하간 컴퓨터 네트워크의 회원들과 관계자들에게 보내는 사무실 메모를 발행했다.그것은 정부, 기관, 기업 및 [44][45][46][47]개인에게 정보 상호작용의 주요 및 필수적인 수단인 모든 사람에게 개방된 전자 공유물로 상상했던 컴퓨터 네트워크에 대한 그의 비전에 대한 그의 회의를 재조정했다.1962년부터 1964년까지 IPTO 책임자로서 Licklider는 정보기술에서 가장 중요한 세 가지 발전, 즉 여러 주요 대학에서의 컴퓨터 과학 학과의 설립, 시분할 [47]및 네트워킹을 시작했습니다.1969년에 스탠포드 연구소(현재의 SRI International)는 인터넷의 [48]전신인 ARPANET을 구성하는 4개의 원래 노드 중 하나를 운영했습니다.

벤처 캐피털의 출현

1970년대 초에는 이 지역에 많은 반도체 회사, 컴퓨터 회사, 프로그래밍 및 서비스 회사가 두 가지 모두에 서비스를 제공했습니다.산업 공간은 풍부했고 주택은 여전히 저렴했다.이 시대의 성장은 1972년 Kleiner Perkins와 Sequoia Capital을 시작으로 Sand Hill Road에 벤처 캐피털이 출현하면서 가속화되었습니다.1980년 12월 Apple Computer의 13억달러의 기업공개 성공 이후 벤처 캐피털의 가용성은 폭발적으로 증가했습니다.1980년대 이후 실리콘밸리는 세계에서 [49]가장 많은 벤처 캐피털 기업이 밀집해 있는 곳이다.

1971년 Don Hoefler는 Fairchild의 공동 설립자 [11][50]8명의 투자를 포함하여 실리콘 밸리 회사의 기원을 추적했습니다.Kleiner Perkins와 Sequoia Capital의 주요 투자자는 같은 그룹 출신으로,[51] Tech Crunch 2014년 Tech Crunch는 130개 관련 상장사 92개사를 대상으로 2,000개 이상의 기업을 대상으로 한 2조 1천억 달러 이상의 가치로 추산되었습니다.

컴퓨터 문화의 발흥

Homebrew Computer Club은 컴퓨터 [52]디바이스의 DIY 구축과 관련된 부품, 회로 및 정보를 교환하기 위해 모인 전자 매니아와 기술에 관심이 있는 취미로 구성된 비공식 그룹입니다.그것은 멘로 파크의 커뮤니티 컴퓨터 센터에서 만난 고든 프렌치와 프레드 무어에 의해 시작되었다.양사 모두,[53] 사람들이 모여 컴퓨터를 보다 쉽게 이용할 수 있도록 하기 위한 정기적이고 개방적인 포럼을 유지하는 것에 관심이 있었습니다.

1975년 3월, 캘리포니아 산마테오 카운티의 멘로 파크에 있는 프렌치 차고에서 첫 회의가 개최되었습니다.이것은 피플스 컴퓨터 컴퍼니가 검토하기 위해 이 지역에 보낸 최초의 유닛인 MITS Altair 마이크로컴퓨터가 도착했을 때였습니다.스티브 워즈니악과 스티브 잡스는 최초의 애플 I과 (후계자) 애플 II 컴퓨터를 설계하도록 영감을 준 첫 만남으로 인정받고 있습니다.그 결과 홈브루 컴퓨터 [54]클럽에서 애플I의 첫 시사회가 열렸다.이후 회의는 스탠포드 선형 가속기 [55]센터의 강당에서 열렸습니다.

소프트웨어의 등장

반도체는 여전히 이 지역 경제의 주요 요소이지만, 실리콘 밸리는 최근 몇 년간 소프트웨어와 인터넷 서비스의 혁신으로 가장 유명했습니다.실리콘 밸리는 컴퓨터 운영 체제, 소프트웨어 및 사용자 인터페이스에 큰 영향을 끼쳤습니다.

더글라스 엥겔바트는 NASA, 미국 공군 및 ARPA의 자금을 사용하여 1960년대 중반과 1970년대 스탠포드 연구소(현재의 SRI International)에서 마우스와 하이퍼텍스트 기반의 협업 도구를 발명했으며, 1968년 '모든 데모의 어머니'로 처음 공개 시연되었다.SRI의 Engelbart 증강연구센터도 ARPANET(인터넷의 선행기관)의 출범과 Network Information Center(현 InterNIC)의 설립에 관여하고 있습니다.제록스는 1970년대 초부터 엥겔바트의 최고 연구원들을 고용했다.1970년대와 1980년대에 Xerox의 Palo Alto Research Center(PARC)는 객체 지향 프로그래밍, 그래피컬 사용자 인터페이스(GUI), 이더넷, PostScript 및 레이저 프린터에서 중추적인 역할을 했습니다.

Xerox가 자사의 기술을 사용하여 장비를 마케팅하는 동안, 대부분의 경우 그 기술은 다른 곳에서 번창했습니다.Xerox의 발명은 직접 3Com과 Adobe Systems로 이어졌고, 간접적으로 Cisco, Apple Computer 및 Microsoft로 이어졌습니다.애플의 매킨토시 GUI는 스티브 잡스의 PARC 방문과 그에 따른 주요 [56]인력 채용의 결과였다.Cisco의 추진력은 스탠포드 대학의 [57]이더넷 캠퍼스 네트워크를 통해 다양한 프로토콜을 라우팅해야 하는 필요성에서 비롯되었습니다.

인터넷 시대

인터넷의 상업적 사용은 실용화되었고 1990년대 초에 걸쳐 서서히 성장하였다.1995년에 인터넷의 상업적 사용이 크게 증가하여 인터넷 스타트업인 Amazon.com, eBay, 그리고 Craigslist의 전신인 인터넷 스타트업의 초기 [58]물결이 시작되었다.

실리콘밸리는 일반적으로 1990년대 중반에 시작되어 2000년 4월 나스닥 주식시장이 급격히 하락하기 시작한 후 붕괴된 닷컴 버블의 중심이었던 것으로 여겨진다.거품 시대에 부동산 가격은 전례 없는 수준에 이르렀다.잠시 동안, 샌드 힐 로드는 세계에서 가장 비싼 상업용 부동산의 본거지였고, 경제 호황은 극심한 교통 체증을 초래했다.

페이팔 마피아는 때때로 [59]2001년 닷컴 파탄 이후 소비자 중심의 인터넷 회사들의 재등장을 고무시킨 것으로 알려져 있다.닷컴 붕괴 후에도 실리콘밸리는 세계 최고의 연구개발 센터 중 하나로 계속 자리매김하고 있습니다.2006년 월스트리트 저널의 기사에 따르면 미국에서 가장 창의적인 도시 20곳 중 12곳이 캘리포니아에 있고 그 중 10곳이 실리콘 [60]밸리에 있었다.산호세가 2005년 출원한 실용특허 3867건으로 1위를 차지했고, 2위는 서니베일로 1881건의 실용특허를 [61]받았다.실리콘밸리는 또한 상당한 수의 [62]"유니콘" 벤처의 본거지이기도 하며, 이는 10억 달러를 넘어선 신생 기업들을 지칭한다.

경제.

샌프란시스코 베이 에리어에는 387,000개의 하이테크 일자리가 있으며, 이 중 실리콘 밸리는 225,300개의 하이테크 일자리를 차지하고 있습니다.실리콘밸리는 민간 근로자 1000명당 285.9명으로 수도권에서 가장 높은 첨단 기술 인력 밀집도를 보이고 있다.실리콘밸리는 14만4800달러로 미국에서 가장 높은 평균 첨단기술 급여를 받고 있다.[63]주로 첨단 기술 분야인 캘리포니아 주(州)의 San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara는 [64]1인당 미국에서 가장 많은 백만장자와 가장 많은 억만장자를 보유하고 있습니다.

그 지역은 미국에서 [65][66]가장 큰 첨단 기술 제조 중심지이다.이 지역의 실업률은 2009년 1월 9.4%에서 2019년 [67]8월 현재 2.7%로 사상 최저치를 기록했다.실리콘밸리는 2011년 미국 벤처투자의 41%, 2012년 [68]46%를 받았다.더 많은 전통 산업도 첨단 기술의 발전 가능성을 인식하고 있으며, 몇몇 자동차 제조업체들은 실리콘 밸리에 사무실을 개설하여 기업가적 [69]생태계를 활용하고 있습니다.

트랜지스터의 제조는 실리콘 밸리의 핵심 산업이었다.생산[70] 노동력은 대부분 아시아계 및 라틴계 이민자로 구성되어 있으며, 이들은 집적회로 제조에 사용되는 화학물질로 인해 저임금을 받고 위험한 환경에서 일했다.기술, 엔지니어링, 설계, 행정직의 [72]보수가 상당 부분[71] 좋았다.

주택

실리콘 밸리는 일자리 창출과 주택 건설 사이의 시장 불균형으로 인해 심각한 주택난을 겪고 있습니다. 2010년부터 2015년까지 주택 건설보다 더 많은 일자리가 창출되었습니다.(40,000개의 일자리, 60,000개의 주택 단위)[73]이 부족은 생산직 [74]노동자의 범위를 훨씬 벗어나 집값을 매우 높게 만들었다.2016년 기준으로 방 두 개짜리 아파트는 약 2,500달러에 임대되었고, 중간 집값은 약 1백만 [73]달러였다.파이낸셜포스트는 실리콘밸리를 미국에서 가장 비싼 [75]주택지로 꼽았다.노숙은 중산층 거주자의 손이 닿지 않는 주택의 문제이며, 2015년 현재 낡은 [76]호텔을 개조하여 대피소를 개발하기 위해 노력하고 있는 산호세 이외에는 대피소가 거의 없다.

이코노미스트는 또한 높은 생활비를 이 지역 산업의 성공으로 돌린다.하지만, 이러한 높은 봉급과 낮은 봉급 사이의 불화는 더 이상 그곳에서 살 여유가 없는 많은 주민들을 밖으로 내몰고 있다.베이 에리어에서는, 향후 몇 년 이내에 이주를 계획하고 있는 주민이, 2016년 이후 34%에서 46%[77][78]로 35%증가했습니다.

주목받는 기업

실리콘 밸리에 수천 개의 하이테크 기업이 본사를 두고 있습니다.Fortune 1000대 기업에는 다음과 같은 기업이 포함되어 있습니다.

실리콘 밸리에 본사를 둔 기타 주목할 만한 기업(그 중 일부는 폐지, 인수 또는 이전)은 다음과 같습니다.

- 23andMe

- 3Com (Hewlett-Packard에 인수)

- 8x8

- 액텔

- 주식회사 액티베이트

- 아답텍

- 아리아 게임즈 앤드 엔터테인먼트

- 알테라

- Amazon.com의 A9.com

- Amazon.com의 Lab126.com

- 암달

- 아타리

- 아트멜

- Brocade 커뮤니케이션 시스템(Broadcom에 인수)

- BEA Systems(Oracle Corporation이 인수)

- 익스트림 네트워크

- 페어차일드 반도체

- Flex (공식적으로는 Flextronics)

- 주조 공장 네트워크

- Geeknet(슬래시닷)

- Global Foundries (뉴욕 몰타로 이전)

- 고프로

- 하모닉

- 히타치 데이터 시스템즈

- Hitachi 글로벌 스토리지 테크놀로지

- Hewlett Packard Enterprise (텍사스주 스프링으로 이전)

- IDEO

- 인포마티카

- Linked In(Microsoft가 인수)

- 록히드 마틴 스페이스(현재는 콜로라도주 덴버에 본사가 있음)

- 로지텍

- LSI(Broadcom에 인수됨)

- Maxtor(Seagate가 인수)

- McAfee (인텔에 인수)

- Memorex(Burroughs가 인수)

- 모질라 재단

- 무브

- National Semiconductor(텍사스 인스트루먼트에서 인수)

- NXP 반도체

- 누크(반스앤노블 자회사)

- Oracle Corporation (텍사스 오스틴으로 이전)

- 주식회사 팜(TCL 주식회사 인수)

- PARC

- 프루프 포인트

- 퀀트캐스트

- 쿠오라

- 램버스

- 주식회사 로쿠

- RSA 보안(EMC가 인수)

- SanDisk(Western Digital에 인수됨)

- SolarCity (Tesla, Inc.에 인수)

- Sony Mobile Communications (미국 자회사)

- 소니 인터랙티브 엔터테인먼트

- SRI 인터내셔널

- Sun Microsystems (Oracle Corporation에 인수)

- Sun Power

- 서베이몽키

- Symantec(현재는 NortonLifeLock으로 애리조나주 Tempe에 본사가 있음)

- Syntex(Roche가 인수)

- Tesla, Inc.(현재는 텍사스주 오스틴에 본사가 있음)

- TIBCO 소프트웨어

- 티보

- TSMC

- 우버

- 베리폰

- VeriSign

- Veritas Technologies (Symantec에서 분리)

- VMware(델테크놀로지스가 인수)

- 월마트 랩스

- WebEx(시스코시스템즈가 취득)

- 유튜브(Google에 인수)

- 옐프 주식회사

- 줌

- 징가

- Xilinx(AMD가 인수)

인구 통계

이 용어의 의미에 포함되는 지리적 지역에 따라 실리콘밸리의 인구는 350만에서 400만 사이이다.1999년 캘리포니아 공공정책연구소의 AnnaLee Saxenian의 연구에 따르면 실리콘밸리의 과학자와 엔지니어의 3분의 1이 이민자였으며 1980년 이후 실리콘밸리의 첨단 기술 회사 중 거의 4분의 1이 중국(17%)이나 인도계 CEO(7%)[86]에 의해 운영되었다고 한다.수천 명의 "한 자릿수 백만장자"를 포함한 잘 보상된 기술 직원과 관리자들의 계층이 있습니다.이러한 소득과 자산 범위는 실리콘 [87]밸리의 중산층 생활을 지탱할 것입니다.

다양성

2006년 11월, 캘리포니아 대학 데이비스는 [88]주내 여성의 비즈니스 리더십을 분석한 보고서를 발표했습니다.캘리포니아에 본사를 둔 400대 공기업 중 103곳이 샌타클라라 카운티(모든 카운티 중 가장 많은 곳)에 위치해 있지만 실리콘밸리 기업의 8.8%만이 여성 CEO를 [89]: 4, 7 둔 것으로 나타났다.이는 [90]주에서 가장 낮은 비율이었다. (샌프란시스코 카운티는 19.2%, 마린 카운티는 18.5%)[89]

실리콘 밸리의 기술 리더 자리는 남성들이 [91]거의 독점적으로 차지하고 있다.이는 벤처캐피털 자금을 지원받는 여성 주도 스타트업의 수뿐만 아니라 여성이 창업한 신생기업 수에서도 나타난다.Wadhwa는 [92]이공계를 공부하려는 부모의 격려가 부족하다는 것이 기여 요인이라고 말했다.그는 또한 여성 롤모델의 부족을 언급하며 빌 게이츠, 스티브 잡스, 마크 저커버그와 같은 대부분의 유명한 기술 리더들이 남성이라고 [91]언급했다.

2014년에는 구글, 야후, 페이스북, 애플 등이 상세한 직원 내역을 제공하는 기업 투명성 보고서를 발표했다.지난 5월 구글은 전 세계 기술직원의 17%가 여성이며 미국에서는 1%가 흑인이고 2%가 [93]히스패닉계라고 밝혔다.2014년 6월, Yahoo!와 Facebook으로부터 리포트를 입수.Yahoo!는 기술직의 15%가 여성, 2%가 흑인, 4%가 [94]히스패닉이라고 밝혔다.Facebook은 기술직의 15%가 여성이고 3%가 히스패닉이고 1%가 [95]흑인이라고 보고했습니다.지난 8월 애플은 전 세계 기술직원의 80%가 남성이며 미국에서는 기술직의 54%가 백인, 23%가 [96]아시아인이라고 발표했다.곧이어 USA Today는 실리콘 밸리의 기술 산업의 다양성 부족에 대한 기사를 실었는데, 실리콘 밸리의 대부분이 백인 또는 아시아인이고 남성이라고 지적했다."블랙스와 히스패닉계는 대부분 존재하지 않으며, 실리콘 밸리에서는 대기업에서 창업,[97] 벤처 캐피털에 이르기까지 여성의 대표성이 부족합니다."라고 보고서는 전했다.민권 운동가인 제시 잭슨은 기술 산업의 다양성을 향상시키는 것에 대해 "이것은 민권 [98]운동의 다음 단계"라고 말했고, T. J. 로저스는 잭슨의 주장에 반대했다.

2014년 10월 현재, 몇몇 유명 실리콘 밸리 기업들은 여성 준비 및 채용에 적극적으로 나서고 있습니다.블룸버그통신은 애플, 페이스북, 구글, 마이크로소프트(MS)가 제20회 연례 컴퓨팅 여성 그레이스 호퍼 기념 컨퍼런스에 참석해 여성 [99]엔지니어와 기술 전문가를 적극 영입하고 채용할 가능성이 있다고 보도했다.같은 달,[100] 제2회 플랫폼 서밋이 개최되어 테크놀로지의 인종과 성별의 다양성 증대에 대해 논의했습니다.2015년 4월 현재,[101] 창업 자금에 있어서 여성의 시각을 활용한 벤처 캐피털 기업의 창설에 경험이 풍부한 여성이 종사하고 있다.

2006년 [89]11월 UC 데이비스가 캘리포니아 여성 비즈니스 리더에 대한 연구를 발표한 후, 일부 새너제이 머큐리 뉴스의 독자들은 성차별이 실리콘밸리의 지도적 성별 격차를 이 주에서 가장 높게 만드는 데 기여했을 가능성을 일축했다.2015년 1월호 뉴스위크지는 실리콘밸리의 [102]성차별과 여성혐오에 대한 보도를 상세히 보도했다.이 기사의 저자인 니나 벌리는 "하이디 로이젠과 같은 여성들이 거래가 논의되는 동안 벤처 투자가가 자신의 손을 바지에 집어넣는 것에 대한 기사를 발표했을 때, 이 모든 것이 사람들을 불쾌하게 했을까요?"[103]

S&[104]P 100의 20.9%에 비해 실리콘밸리 기업의 이사회는 15.7%의 여성으로 구성되어 있습니다.

2012년 파오 대 클라이너 퍼킨스 소송은 경영진 엘렌 파오가 고용주 클라이너 [105]퍼킨스에 대한 성차별을 이유로 샌프란시스코 카운티 상급법원에 제소했다.이 사건은 2015년 2월에 재판에 회부되었다.2015년 3월 27일 배심원단은 모든 [106]혐의에서 클라이너 퍼킨스의 손을 들어줬다.그럼에도 불구하고, 언론에서 널리 보도된 이 사건은 벤처 캐피털과 기술 기업들과 그들의 여성 [107][108]직원들의 성차별에 대한 의식을 크게 발전시켰다.Facebook과 [109]Twitter를 상대로 2건의 다른 소송이 제기되었다.

자치체

다음 Santa Clara County 도시는 전통적으로 실리콘 밸리에 있는 것으로 간주됩니다(알파벳 순서대로).[citation needed]

실리콘 밸리의 지리적 경계는 수년에 걸쳐 변화해왔다.역사적으로 실리콘 밸리라는 용어는 산타 클라라 [1][2][3]밸리와 동의어로 취급되었고, 그 의미는 나중에 산타 클라라 카운티와 남부 산 마테오 카운티와 남부 알라메다 [110]카운티의 인접 지역을 가리키는 것으로 발전했다.그러나 수년간 이 지리적 지역은 샌프란시스코 카운티, 콘트라 코스타 카운티, 알라메다 카운티 및 산 마테오 카운티 북부 지역으로 확장되어 왔으며, 지역 경제의 확장과 신기술의 [110]개발로 인해 이러한 변화가 일어났다.

미국 노동부의 고용 및 임금 분기 센서스 프로그램은 실리콘 밸리를 알라메다, 콘트라 코스타, 샌프란시스코, 산마테오, 산타 클라라, 산타 크루즈 [111]카운티로 정의했습니다.

2015년 MIT 연구진은 성장 가능성이 높은 스타트업이 있는 도시를 측정하는 새로운 방법을 개발했으며, 이는 실리콘 밸리를 멘로 파크, 마운틴 뷰, 팔로 알토, 서니베일 [112][113]시를 중심으로 정의합니다.

교육

Woodside와 같은 실리콘밸리 고급 커뮤니티의 공립학교에 대한 자금은 종종 그 목적을 위해 설립되고 지역 주민들이 자금을 대는 민간 재단의 보조금으로 보충된다.이스트 팔로 알토와 같이 덜 부유한 지역에 있는 학교들은 반드시 주정부 [114]자금에 의존해야 한다.

단과대학 및 단과대학

- 베이 에리어 의학 아카데미

- 캘리포니아 경영 공과 대학

- 캘리포니아 사우스베이 대학교

- 카네기 멜론 실리콘 밸리

- 카냐다 대학교

- 샤봇 대학교

- 데안자 칼리지

- 드브리 대학교

- 에버그린 밸리 칼리지

- 풋힐 칼리지

- 가빌란 대학교

- 국제 기술 대학

- 새너제이 링컨 로스쿨

- 멘로 대학교

- 미션 칼리지

- 내셔널 대학교 새너제이 캠퍼스

- 노스웨스턴 공과대학교

- 올론 대학교

- 팔로알토 대학교

- 파머 칼리지 오브 카이로프랙틱 웨스트 캠퍼스

- 페랄타 칼리지

- 새너제이 시립 대학

- 산호세 주립 대학교

- 산타클라라 대학교

- 싱귤러티 대학교

- 소피아 대학교

- 스탠퍼드 대학교

- 캘리포니아 대학교 산타크루즈 실리콘밸리

- 샌프란시스코 대학교 사우스베이 캠퍼스

- 실리콘밸리 대학교

- 웨스트 밸리 칼리지

- 윌리엄 제섭 대학교

문화

이벤트

- 새너제이, Apple Worldwide Developers Conference

- 페이스북 F8, 새너제이

- 베이콘, 산타클라라

- 새너제이 공원에서의 크리스마스

- 시네퀘스트 영화제, 여러 장소

- FanimeCon, 새너제이

- LiveStrong Challenge 자전거 경주, 새너제이

- 로스[115] 알토스 예술과 와인 축제

- 마운틴뷰 예술과 와인 페스티벌, 마운틴뷰[116]

- 팔로알토[117] 예술제

- 샌프란시스코 국제 아시아계 미국인 영화제, 새너제이

- 새너제이 재즈 페스티벌

- 새너제이 홀리데이 퍼레이드, 새너제이

- 실리콘밸리 코믹콘, 새너제이

- 실리콘 밸리 프라이드, 새너제이

- 스탠퍼드 재즈 페스티벌

그래픽 아트

박물관

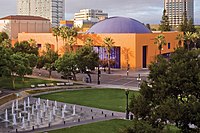

- 컴퓨터 역사 박물관

- 산호세 어린이 발견 박물관

- 퀴리오디세이

- 산타클라라 대학교 드사이셋 박물관

- 힐러 항공 박물관

- 산호세 역사공원

- HP 차고

- 인텔 뮤지엄

- 스탠퍼드 대학교 Iris & B. Gerald Cantor 시각예술 센터

- 산호세 재팬 아메리칸 뮤지엄

- 로스 알토스 역사 박물관

- 모펫 필드 역사학회 박물관

- 미국유산박물관

- 팔로알토 아트센터

- 팔로알토 주니어 박물관 및 동물원

- 포르투갈 역사박물관

- 로지크루치아 이집트 박물관

- 싼마테오현 역사박물관

- 산호세 미술관

- 새너제이 퀼트 & 섬유 박물관

- 서니베일 문화공원 박물관

- 기술혁신박물관

- 베트남 박물관

- 윈체스터 미스터리 하우스

공연 예술

- 미국 베토벤 협회

- 새너제이 아메리칸 뮤지컬 극장

- 발레 산호세

- 빙 콘서트홀

- 캘리포니아 청소년 교향곡

- 산 호세 오페라

- 심포니 실리콘 밸리

- 새너제이 공연 예술 센터

- 새너제이 브로드웨이

- 새너제이 레퍼토리 극장

- 산호세 청년 교향곡

- 새너제이 임프리브

- 스즈댄스코

- 브로드웨이 바이 더 베이

- TheaterWorks Theater Company

미디어

1980년 Intelligent Machines Journal은 InfoWorld로 이름을 바꾸고 Palo Alto에 사무실을 두고 [122]이 계곡의 마이크로컴퓨터 산업의 출현을 취재하기 시작했습니다.

지역 및 전국 미디어는 실리콘 밸리와 그 회사들을 다룹니다.CNN, 월스트리트저널, 블룸버그 뉴스는 팔로알토에서 실리콘밸리 지국을 운영하고 있다.공영방송 KQED(TV)와 KQED-FM 및 베이 에리어 지역 ABC 방송국 KGO-TV가 새너제이에서 지국을 운영하고 있습니다.NBC의 지역 베이 에리어 계열사인 KNTV는 산호세에 위치하고 있습니다.전국에서 방송되는 TV쇼 테크나우(Tech Now)와 CNBC 실리콘밸리 지국이 이곳에서 제작된다.실리콘 밸리를 서비스하는 새너제이 소재 미디어에는 새너제이 머큐리 뉴스 데일리, 메트로 실리콘 밸리 주간 등이 있습니다.

전문 매체로는 El Observador와 San Jose/Silicon Valley Business Journal이 있습니다.베이 에리어의 다른 주요 TV 방송국, 신문 및 미디어는 대부분 샌프란시스코 또는 오클랜드에서 운영됩니다.Patch.com는 실리콘밸리 주민들에게 현지 뉴스, 토론 및 이벤트를 제공하는 다양한 웹 포털을 운영하고 있습니다.Mountain View에는 KMVT-15라는 비영리 방송국이 있습니다.KMVT-15의 프로그램에는 Silicon Valley Education News(EdNews)-Edward Tico Producer가 포함됩니다.

문화 레퍼런스

일부 미디어 출연은 출시일 순으로 진행됩니다.

- 뷰 투 어 킬—제임스 본드 시리즈의 1985년 영화.본드는 실리콘 [123]밸리를 파괴하기 위해 이 영화의 대항마인 맥스 조린의 치밀한 책략을 좌절시켰다.

- Nerds의 승리: 우연한 제국의 부상– 1996년 다큐멘터리

- Pirates of Silicon Valley—1999년 Apple Computer와 Microsoft의 초창기를 그린 영화(Silicon Valley에 기반을 둔 것은 아니지만)

- 코드 몽키즈—2007년 코미디 시리즈

- 소셜 네트워크—2010년 영화

- Startups Silicon Valley—Bravo에서 2012년[124] 첫선을 보인 리얼 TV 시리즈

- 베타스 - 2013년 Amazon[125] Video에서 첫선을 보인 TV 시리즈

- 잡스—2013년 영화

- 인턴십—2013년 구글에서 일하는 것에 관한 코미디 영화

- 실리콘 밸리 - 2014년 HBO의 미국 시트콤

- Halt and Catch Fire—2014년 TV 시리즈, 최근 두 시즌은 주로 실리콘 밸리를 배경으로 합니다.

- 스티브 잡스—2015년 영화

- Watch Dogs 2 - Ubisoft가 개발한 2016년 비디오 게임

- Valley of the Boom - 실리콘 밸리의 1990년대 기술 붐에 대한 2019년 문서 드라마

- Devs: 2020 TV 미니시리즈

- Start-Up—2020년 한국 TV 시리즈에서는 한국의 3명의 인공지능(AI) 개발자가 실리콘 밸리에 위치한 가상의 회사인 2STO의 엔지니어 자리를 제안받았습니다.

- The Dropout—2022년 테라노스의 흥망성쇠를 다룬 TV 미니시리즈

- Super Pumped—Travis Kalanick의 Uber 시절 이야기를 다룬 2022년 TV 시리즈

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 실리콘 밸리의 명소 목록

- 전 세계 '실리콘' 지명이 있는 곳 목록

- 전 세계 기술 센터 목록

- 반도체 산업

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c d Malone, Michael S. (2002). The Valley of Heart's Delight: A Silicon Valley Notebook 1963 - 2001. New York: John S. Wiley & Sons. p. xix. ISBN 9780471201915. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Matthews, Glenna (2003). Silicon Valley, Women, and the California Dream: Gender, Class, and Opportunity in the Twentieth Century. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780804741545.

- ^ a b Shueh, Sam (2009). Silicon Valley. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780738570938. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "Silicon Valley Business Journal – San Jose Area has World's Third-Highest GDP Per Capita, Brookings Says". Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Kolomatsky, Michael (June 17, 2021). "Where Are the Million-Dollar Homes? - A new report reveals which U.S. metropolitan areas have the highest percentage of homes valued at $1 million or more". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Silicon Valley Index 2022 report" (PDF). Silicon Valley Index. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Carson, Biz. "16 Silicon Valley landmarks you must visit on your next trip". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ "Tech Headquarters You Can Visit in Silicon Valley". TripSavvy. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Sheng, Ellen (December 3, 2018). "Why the headquarters of iconic tech companies are now among America's top tourist attractions". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ "'Dire situation': Silicon Valley cracks down on water use as California drought worsens Climate crisis the Guardian". amp.theguardian.com. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Laws, David (January 7, 2015). "Who named Silicon Valley?". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ Castells, Manuel (2011). The Rise of the Network Society. John Wiley & Sons. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4443-5631-1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Sturgeon, Timothy J. (2000). "How Silicon Valley Came to Be". In Kenney, Martin (ed.). Understanding Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region. Stanford University. ISBN 978-0-8047-3734-0. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Black, Dave. "Moffett Field History". moffettfieldmuseum.org. Archived from the original on April 6, 2005. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (January 15, 2020). "Silicon Valley Abandons the Culture That Made It the Envy of the World". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Markoff, John (April 17, 2009). "Searching for Silicon Valley". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ 스테판 B.Adams, "Stanford's Regionalism in the Regionalism in Stanford's Rise of Silicon Valley", Enterprise & Society 2003 4 (3) : 521 ~ 543

- ^ 프레더릭 터먼: "터먼이 1946년 스탠포드 대학에 공학 학장으로 돌아왔을 때, 그는 전시의 명성과 경험을 미국 정부를 위한 연구를 장려함으로써 대학의 수입을 늘리는 데 활용했다.

- ^ Sandelin, John, The Story of the Stanford Industrial/Research Park, 2004, 2007년 6월 9일 Wayback Machine에 아카이브

- ^ "History of Computing Industrial Era 1984–1985". thocp.net. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "The Stanford Research Park: The Engine of Silicon Valley". PaloAltoHistory.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ Leonhardt, David (April 6, 2008). "Holding On". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

In 1955, the physicist William Shockley set up a semiconductor laboratory in Mountain View, partly to be near his mother in Palo Alto. …

- ^ Markoff, John (January 13, 2008). "Two Views of Innovation, Colliding in Washington". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

The co-inventor of the transistor and the founder of the valley's first chip company, William Shockley, moved to Palo Alto, Calif., because his mother lived there. ...

- ^ Tajnai, Carolyn (May 1985). "Fred Terman, the Father of Silicon Valley". Stanford Computer Forum. Carolyn Terman. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ "Silicon Valley's First Founder Was Its Worst Backchannel". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Goodheart, Adam (July 2, 2006). "10 Days That Changed History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017.

- ^ McLaughlin, John; Weimers, Leigh; Winslow, Ward (2008). Silicon Valley: 110 Year Renaissance. Silicon Valley Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-9649217-4-0. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ Kooi, E.; Schmitz, A. (2005). "Brief Notes on the History of Gate Dielectrics in MOS Devices". High Dielectric Constant Materials: VLSI MOSFET Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 33–44. ISBN 9783540210818.

- ^ a b Black, Lachlan E. (2016). New Perspectives on Surface Passivation: Understanding the Si-Al2O3 Interface. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 9783319325217. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Heywang, W.; Zaininger, K.H. (2013). "2.2. Early history". Silicon: Evolution and Future of a Technology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 26–28. ISBN 9783662098974.

- ^ Lécuyer, Christophe; Brock, David C. (2010). Makers of the Microchip: A Documentary History of Fairchild Semiconductor. MIT Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780262294324. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Feldman, Leonard C. (2001). "Introduction". Fundamental Aspects of Silicon Oxidation. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–11. ISBN 9783540416821.

- ^ Sah, Chih-Tang (October 1988). "Evolution of the MOS transistor-from conception to VLSI" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 76 (10): 1280–1326 (1290). Bibcode:1988IEEEP..76.1280S. doi:10.1109/5.16328. ISSN 0018-9219. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

Those of us active in silicon material and device research during 1956–1960 considered this successful effort by the Bell Labs group led by Atalla to stabilize the silicon surface the most important and significant technology advance, which blazed the trail that led to silicon integrated circuit technology developments in the second phase and volume production in the third phase.

- ^ a b c "1960: Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Transistor Demonstrated". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780470508923. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120 & 321–323. ISBN 9783540342588.

- ^ Lécuyer, Christophe (2006). Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 253–6 & 273. ISBN 9780262122818.

- ^ "1964 – First Commercial MOS IC Introduced". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ a b "1971: Microprocessor Integrates CPU Function onto a Single Chip". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ Osborne, Adam (1980). An Introduction to Microcomputers. Vol. 1: Basic Concepts (2nd ed.). Berkeley, California: Osborne-McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-931988-34-9. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ Intel's First Microprocessor—the Intel 4004, Intel Corp., November 1971, archived from the original on May 13, 2008, retrieved May 17, 2008

- ^ Federico Faggin, The Making of the First Microprocessor, 2019년 10월 27일 Wayback Machine, IEEE Solid-State Circuits Magazine, 2009년 겨울, IEEE Xplore에서 아카이브됨

- ^ Intel (April 15, 1974). "From CPU to software, the 8080 Microcomputer is here". Electronic News. New York: Fairchild Publications. pp. 44–45. 일렉트로닉 뉴스는 주간 무역 신문이었다.1974년 5월 2일자 일렉트로닉스 잡지에 같은 광고가 실렸다.

- ^ Licklider, J. C. R. (April 23, 1963). "Topics for Discussion at the Forthcoming Meeting, Memorandum For: Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network". Washington, D.C.: Advanced Research Projects Agency, via KurzweilAI.net. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ Leiner, Barry M.; et al. (December 10, 2003). ""Origins of the Internet" in A Brief History of the Internet version 3.32". The Internet Society. Archived from the original on June 4, 2007. Retrieved November 3, 2007.

- ^ Garreau, Joel (2006). Radical Evolution: The Promise and Peril of Enhancing Our Minds, Our Bodies—and what it Means to be Human. Broadway. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7679-1503-8. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (United States Government)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Christophe Lécuyer, "대학이 업계에 정말로 빚진 것은 무엇입니까?스탠포드 솔리드 스테이트 일렉트로닉스의 사례' Minerva: 2005년 과학, 학습 및 정책 리뷰: 51 ~ 71

- ^ Scott, W. Richard; Lara, Bernardo; Biag, Manuelito; Ris, Ethan; Liang, Judy (2017). "The Regional Economy of the San Francisco Bay Area". In Scott, W. Richard; Kirst, Michael W. (eds.). Higher Education and Silicon Valley: Connected But Conflicted. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9781421423081. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ 100년에 걸친 법적 다리: El Dorado의 금광에서 실리콘 밸리의 "황금" 스타트업까지 2013년 6월 1일 그레고리 그로모프가 Wayback Machine에 보관한

- ^ Morris, Rhett (July 26, 2014). "The First Trillion-Dollar Startup". Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ "Homebrew And How The Apple Came To Be". atariarchives.org. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Markoff, John (2006) [2005]. What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303676-0. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Wozniak, Steve (2006). iWoz. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-393-33043-4.

After my first meeting, I started designing the computer that would later be known as the Apple I. It was that inspiring.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000) [1984]. Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-135895-8.

- ^ 그래피컬 사용자 인터페이스(GUI)는 2002년 10월 1일 apple-history.com에서 웨이백 머신으로 아카이브되었습니다.

- ^ Waters, John K. (2002). John Chambers and the Cisco Way: Navigating Through Volatility. John Wiley & Sons. p. 28. ISBN 9780471273554.

- ^ W. Josephujjwal sarkar Campbell (January 2, 2015). "The Year of the Internet". 1995: The Year the Future Began. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27399-3.

- ^ Banks, Marcus (May 16, 2008). "Nonfiction review: 'Once You're Lucky'". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Reed Albergotti, "The Most Orbinctional Towns in America", 2017년 12월 3일, Wayback Machine Wall Street Journal, 2006년 7월 22-23일, P1에 보관.

- ^ 따오기

- ^ "The Unicorn List". Fortune. January 22, 2015. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Cybercities 2008: An Overview of the High-Technology Industry in the Nation's Top 60 Cities". aeanet.org. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "America's Greediest Cities". Forbes. December 3, 2007. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017.

- ^ Albanesius, Chloe (June 24, 2008). "AeA Study Reveals Where the Tech Jobs Are". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin. "Silicon Valley and N.Y. still top tech rankings". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "SAN JOSE-SUNNYVALE-SANTA CLARA METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREA" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2019.

- ^ "Venture Capital Survey Silicon Valley Fourth Quarter 2011". Fenwick.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Porsche lands in Silicon Valley to develop sportscars of the future". IBI. May 8, 2017. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

Carmakers who have recently expanded to Silicon Valley include Volkswagen, Hyundai, General Motors, Ford, Honda, Toyota, BMW, Nissan and Mercedes-Benz.

- ^ "Production Occupations (Major Group)". bls.gov. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2014. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ Matthews, Glenda (November 20, 2002). Silicon Valley, Women, and the California Dream: Gender, Class, and Opportunity in the Twentieth Century (1 ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 154–56. ISBN 978-0-8047-4796-7. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "Occupational Employment Statistics Semiconductor and Other Electronic Component Manufacturing". bls.gov. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2014. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Brown, Eliot (June 7, 2016). "Neighbors Clash in Silicon Valley Job growth far outstrips housing, creating an imbalance; San Jose chafes at Santa Clara". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Matthews, Glenda (November 20, 2002). Silicon Valley, Women, and the California Dream: Gender, Class, and Opportunity in the Twentieth Century (1 ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 233. ISBN 978-0-8047-4796-7. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ News, Bloomberg (July 29, 2016). "Zero down on a $2 million house is no problem in Silicon Valley's 'weird and scary' real estate market Financial Post". Financial Post. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite news}}:last1=범용명(도움말)이 있습니다. - ^ Potts, Monica (December 13, 2015). "Dispossessed in the Land of Dreams: Those left behind by Silicon Valley's technology boom struggle to stay in the place they call home". The New Republic. Archived from the original on December 14, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

A 2013 census showed Santa Clara County having more than 7,000 homeless people, the fifth-highest homeless population per capita in the country and among the highest populations sleeping outside or in unsuitable shelters like vehicles.

- ^ "Silicon Valley is changing, and its lead over other tech hubs narrowing". The Economist. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ "Why startups are leaving Silicon Valley". The Economist. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ Sharf, Samantha. "Full List: America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes 2017". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "Kron4 – Palo Alto Ranks No. 5 as Most Educated in the U.S." Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Palo Alto, Atherton crack top 10 priciest ZIP codes in U.S." March 29, 2016. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Saratoga among most educated small towns". January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "The top 10 wealthiest cities in America". madison.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ "America's Richest Zip Codes 2011". Bloomberg.com. December 7, 2011. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Zeveloff, Julie. "The 20 Most Expensive Housing Markets In America". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Saxenian, AnnaLee (1999). "Silicon Valley's New Immigrant Entrepreneurs" (PDF). Public Policy Institute of California. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2016.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Riflin, Gary (August 5, 2007). "In Silicon Valley, Millionaires Who Don't Feel Rich". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

Silicon Valley is thick with those who might be called working-class millionaires

- ^ "Women Missing From Decision-Making Roles in State Biz" (Press release). UC Regents. November 16, 2006. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c Ellis, Katrina (2006). "UC Davis Study of California Women Business Leaders" (PDF). UC Regents. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Zee, Samantha (November 16, 2006). "California, Silicon Valley Firms Lack Female Leaders (Update1)". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Wadhwa, Vivek (November 9, 2011). "Silicon Valley women are on the rise, but have far to go". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

This is one of Silicon Valley's most glaring faults: It is male-dominated.

- ^ Wadhwa, Vivek (May 15, 2010). "Fixing Societal Problems: It Starts With Mom and Dad". TechCrunch. AOL. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ Musil, Steven (May 28, 2014). "Google discloses its diversity record and admits it's not good". CNET. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Levy, Karyne (June 17, 2014). "Yahoo's Diversity Numbers Are Just As Terrible As The Rest of the Tech Industry's". Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Maxine (June 25, 2014). "Building a More Diverse Facebook". Facebook. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "Apple diversity report released; Cook 'not satisfied with the numbers'". CBS Interactive. Associated Press. August 13, 2014. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016.

- ^ Guynn, Jessica; Weise, Elizabeth (August 15, 2014). "Lack of diversity could undercut Silicon Valley". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Koch, Wendy (August 15, 2014). "Jesse Jackson: Tech diversity is next civil rights step". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Burrows, Peter (October 8, 2014). "Gender Gap Draws Thousands From Google, Apple to Phoenix". Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Porter, Jane (October 29, 2014). "Inside the Movement That's Trying to Solve Silicon Valley's Diversity Problem". Fast Company. Mansueto Ventures. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Claire Cain Miller (April 1, 2015). "Female-Run Venture Capital Funds Alter the Status Quo" (Dealbook blog). The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

We’re in the middle of a shifting trend where there are newly wealthy women putting their money to work, and similarly we’re starting to have a larger number of experienced investors,

- ^ Burleigh, Nina (January 28, 2015). "What Silicon Valley Thinks of Women". Newsweek. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Tam, Ruth (January 30, 2015). "Artist behind Newsweek cover: it's not sexist, it depicts the ugliness of sexism". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Ellen Pao gender discrimination trial grips Silicon Valley". TheGuardian.com. March 13, 2015. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ "Complaint of Ellen Pao" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Liz Gannes and Nellie Bowles (March 27, 2015). "Live: Ellen Pao Loses on All Claims in Historic Gender Discrimination Lawsuit Against Kleiner Perkins". Re/code. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

That's the full verdict. No on all claims.

- ^ Decker, Sue (March 26, 2015). "A Fish Is the Last to Discover Water: Impressions From the Ellen Pao Trial". Re/code. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

We may look back at this as a watershed moment—regardless of how the very attentive jury comes out on their verdict.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad (March 27, 2015). "Ellen Pao Disrupts How Silicon Valley Does Business". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

Ms. Klein argued that the Kleiner trial would become a landmark case for women in the workplace, as consequential for corporate gender relations as Anita Hill's accusations in 1991 of sexual harassment during the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas

- ^ Streitfeld, David (March 27, 2015). "Ellen Pao Loses Silicon Valley Gender Bias Case Against Kleiner Perkins". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

In a sign that the struggle over the place of women in Silicon Valley is only beginning, gender discrimination suits have recently been filed against two prominent companies, Facebook and Twitter.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Chris (April 19, 2012). "Welcome to the new and expanded Silicon Valley". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

After years of drawing a sharp circle that included Santa Clara County as well as southern San Mateo and Alameda counties, this newspaper is expanding the geographic boundaries that it considers to be part of Silicon Valley to include the five core Bay Area counties: Santa Clara, San Mateo, San Francisco, Alameda and Contra Costa.

- ^ "High-tech employment in Silicon Valley, 2001 and 2008". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. September 8, 2009. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

In this analysis, Silicon Valley is defined as Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties, in California.

- ^ 스턴, 스콧, 구즈만, 호르헤Nowcasting and Placecasting 성장 기업가정신 2016년 3월 4일 웨이백 머신에 보관.

- ^ Stern, Scott; Guzman, Jorge (February 6, 2015). "Science Magazine: Sign In". Science. 347 (6222): 606–609. doi:10.1126/science.aaa0201. PMID 25657229. S2CID 206632492. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Packer, George (May 27, 2013). "Change the World Silicon Valley transfers its slogans—and its money—to the realm of politics". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 29, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

In wealthy districts, the public schools have essentially been privatized; they insulate themselves from shortfalls in state funding with money raised by foundations they have set up for themselves.

- ^ "Arts & Wine Festival". Downtown Los Altos. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ "Events". Mountain View Downtown Guide. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ "Festival of the Arts". Palo Alto Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ "Barn Woodshop: Menlo Park furniture repair shop is a remnant of a bygone era". San Jose Mercury News. June 3, 2015. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ "Saturday: Allied Arts Guild holds open house". Almanac News. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Bowles, Nellie (February 6, 2016). "The 'cultural desert' of Silicon Valley finally gets its first serious art gallery". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ "Bay Area Radio Museum - The Charles Herrold Story". August 12, 2014.

- ^ Markoff, John (September 1999). Foreword, Fire in the Valley (Updated ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 978-0-07-135892-7.

- ^ "A View to a Kill (1985) - Plot". IMDb. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ "Start-Ups:Silicon Valley". IMDb. November 5, 2012. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Betas". IMDb. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

추가 정보

책들

- Bronson, Po (2013). The Nudist on the Lateshift: and Other Tales of Silicon Valley. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-8964-9.

- Cringely, Robert X. (1996) [1992]. Accidental Empires: How the boys of Silicon Valley make their millions, battle foreign competition, and still can't get a date. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-88730-855-0.

- English-Lueck, June Anne (2002). Cultures@Silicon Valley. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4429-4.

- Hayes, Dennis (1990) [1989]. Behind the Silicon Curtain: The Seductions of Work in a Lonely Era. Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-0-921689-62-1.

- Kaplan, David A. (2000). The Silicon Boys: And Their Valleys Of Dreams. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-688-17906-9.

- Koepp, Rob (April 11, 2003). Clusters of Creativity: Enduring Lessons on Innovation and Entrepreneurship from Silicon Valley and Europe's Silicon Fen. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-85566-9.

- Lécuyer, Christophe Lécuyer (2006) [2005]. Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930–1970. Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-262-12281-8.

- Levy, Steven (2014) [1984]. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-8839-3.

- O'Mara, Margaret Pugh (2015) [2004]. Cities of Knowledge: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6688-5.

- Pellow, David N; Park, Lisa Sun-Hee (2002). The Silicon Valley of Dreams: Environmental Injustice, Immigrant Workers, and the High-tech Global Economy. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6710-8.

- Saxenian, AnnaLee (1996). Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-75340-2.

- Scoville, Thomas (2001). Silicon Follies (Fiction). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7434-1945-1.

- Whiteley, Carol; McLaughlin, John (2002). Technology, Entrepreneurs and Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-9649217-1-9. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

저널 및 신문

- Kantor, Jodi (December 23, 2014). "A Brand New World in Which Men Ruled". The New York Times.

- Koenig, Neil (February 9, 2014). "Next Silicon Valleys: How did California get it so right?". BBC News.

- Malone, Michael S. (January 30, 2015). "The Purpose of Silicon Valley". MIT Technology Review.

- Norr, Henry (December 27, 1999). "Growth of a Silicon Empire". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Palmer, Barbara (February 4, 2004). "Red tile roofs in Bangalore: Stanford's look copied in Silicon Valley and beyond". Stanford Report.

- Schulz, Thomas (March 4, 2015). "Tomorrowland: How Silicon Valley Shapes Our Future". Der Spiegel.

- Sturgeon, Timothy J. (December 2000). "Chapter Two: How Silicon Valley Came to Be" (PDF). Industrial Performance Center. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Williams, James C. (December 2013). "From White Gold to Silicon Chips: Hydraulic Technology, Electric Power and Silicon Valley". Social Science Information (Abstract). Sage Publications. 52 (4): 558–574. doi:10.1177/0539018413497834. S2CID 145080600. (전체 텍스트를 보려면 구독이 필요합니다.)

시청각

- Silicon Valley: A Five Part Series (DVD). Narrated by Leonard Nimoy. Silicon Valley Historical Association. 2012.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 유지: 기타 인용 AV미디어 (주) (링크) - "A Weekend in Silicon Valley". The New York Times (Slideshow). August 27, 2010.

외부 링크

- Santa Clara County: 캘리포니아의 역사적인 실리콘 밸리—국립공원 서비스 웹사이트

- Silicon Valley—2013년 아메리칸 익스피리언스 다큐멘터리 방송

- 새너제이 주립대학에서 웨이백머신의 실리콘밸리 문화 프로젝트(2007년 12월 20일 아카이브)

- 실리콘 밸리 역사 협회

- 실리콘 밸리의 탄생

- 실리콘밸리 중앙상공회의소 웹사이트