진핵생물

Eukaryote| 진핵생물 시간적 범위: 슈테리언-현재 | |

|---|---|

| 과학 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 (Chatton, 1925) Whittaker & Margulis, 1978 |

| 슈퍼그룹과 왕국[2] | |

| 동의어 | |

진핵생물(/juk ːˈk æ ʊ, -ə/)은 세포가 막으로 결합된 핵을 가지고 있는 유기체인 진핵생물의 영역을 구성합니다. 모든 동물, 식물, 곰팡이 및 많은 단세포 생물은 진핵생물입니다. 그들은 원핵생물의 두 그룹인 박테리아와 고세균과 함께 생명체의 주요 그룹을 구성합니다. 진핵생물은 생물의 수에서 소수를 차지하지만, 일반적으로 훨씬 큰 크기를 감안할 때, 그들의 집단적인 지구 생물량은 원핵생물의 것보다 훨씬 큽니다.

진핵생물은 아스가르드 고세균 내의 고세균에서 출현한 것으로 보입니다. 이것은 생명체의 영역이 박테리아와 고세균 두 개뿐이라는 것을 의미하며, 고세균 중에는 진핵생물이 포함되어 있습니다. 진핵생물은 고생대에 편모세포로 출현했을 가능성이 높습니다. 선도적인 진화 이론은 그들이 미토콘드리아를 형성한 혐기성 아스가르드 고세균과 호기성 프로테오박테리움 사이의 공생에 의해 만들어졌다는 것입니다. 시아노박테리움과의 공생의 두 번째 에피소드는 엽록체와 함께 식물을 만들었습니다.

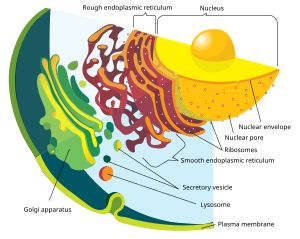

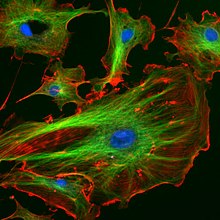

진핵 세포에는 핵, 소포체, 골지 장치와 같은 막 결합 소기관이 포함되어 있습니다. 진핵생물은 단세포 또는 다세포일 수 있습니다. 이에 비해 원핵생물은 일반적으로 단세포입니다. 단세포 진핵생물은 때때로 원생생물이라고 불립니다. 진핵생물은 유사분열을 통해 무성생식을 하고 감수분열과 생식세포 융합(수정)을 통해 무성생식을 할 수 있습니다.

다양성

진핵생물은 [5]가로 3마이크로미터 이하의 피코동물과 같은 미세한 단일 세포에서 190톤의 무게와 최대 33.6미터([6]110피트) 길이의 흰긴수염고래와 같은 동물 또는 해안 삼나무와 같은 식물, 최대 120미터(390피트) 높이의 식물에 이르기까지 다양한 생물입니다.[7] 많은 진핵생물들은 단세포입니다; 원생생물이라고 불리는 비공식적인 그룹은 많은 진핵생물들을 포함하며, 길이가 200피트(61미터)에 이르는 거대한 다시마와 같은 다세포 형태를 가지고 있습니다.[8] 다세포 진핵생물에는 동물, 식물, 곰팡이가 포함되어 있지만, 다시 말하지만, 이 그룹들도 많은 단세포 종을 포함하고 있습니다.[9] 진핵세포는 일반적으로 약 10,000배의 부피를 가진 원핵생물인 박테리아와 고세균보다 훨씬 큽니다.[10][11] 진핵생물은 생물의 수에서 소수를 차지하지만, 그들 중 많은 수가 훨씬 크기 때문에 그들의 집합적인 지구 생물량(468기가톤)은 원핵생물(77기가톤)보다 훨씬 크며, 식물만 지구 전체 생물량의 81% 이상을 차지합니다.[12]

- 진핵생물은 크기가 단일 세포에서 많은 톤의 무게를 가진 유기체에 이르기까지 다양합니다.

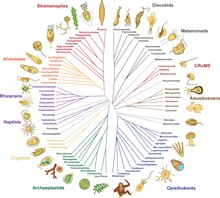

진핵생물은 주로 미세한 유기체로 구성된 다양한 계통입니다.[13] 어떤 형태로든 다세포는 진핵생물 내에서 적어도 25번은 독립적으로 진화했습니다.[14][15] 점액 곰팡이를 형성하는 아메바의 응집을 세지 않고 복잡한 다세포 생물은 동물, 공생균류, 갈조류, 홍조류, 녹조류, 육지 식물 등 6개 진핵생물 계통 내에서만 진화했습니다.[16] 진핵생물은 유전체 유사성에 의해 그룹화되므로 그룹은 종종 눈에 보이는 공유 특성이 부족합니다.[13]

특징 구별하기

핵

진핵생물의 특징은 세포에 핵이 있다는 것입니다. 이것은 그들의 이름을 그리스어 εὖ(eu, "well" 또는 "good")와 κάρυον(karyon, "넛" 또는 "커널", 여기서 "핵"을 의미함)에서 따왔습니다. 진핵 세포는 세포 소기관이라고 불리는 다양한 내막 결합 구조와 세포의 조직과 모양을 정의하는 세포골격을 가지고 있습니다. 핵은 세포의 DNA를 저장하고, 세포는 염색체라고 불리는 선형 다발로 나뉘는데,[18] 이들은 핵분열 과정에서 미세소관 스핀들에 의해 두 개의 일치하는 집합으로 분리됩니다.[19]

생화학

진핵생물은 스테란 합성과 같은 독특한 생화학적 경로를 가진 원핵생물과 여러 면에서 다릅니다.[20] 진핵생물의 특징 단백질은 다른 생명체 영역의 단백질과 상동성이 없지만 진핵생물 사이에서는 보편적인 것으로 보입니다. 여기에는 세포골격의 단백질, 복잡한 전사 기계, 막 분류 시스템, 핵공 및 생화학적 경로의 일부 효소가 포함됩니다.[21]

내막

진핵 세포는 다양한 막 결합 구조를 포함하며, 함께 내막 시스템을 형성합니다.[22] 소포와 액포라고 불리는 단순한 구획은 다른 막에서 싹이 나면서 형성될 수 있습니다. 많은 세포들이 음식과 다른 물질들을 세포내이입 과정을 통해 섭취하는데, 이 과정에서 외막이 침윤한 다음 꼬집어 소포를 형성합니다.[23] 일부 세포 제품은 세포외사멸을 통해 소포에 남을 수 있습니다.[24]

핵은 핵 외피로 알려진 이중막으로 둘러싸여 있으며, 핵 구멍은 물질이 안팎으로 움직일 수 있도록 합니다.[25] 핵막의 다양한 튜브 및 시트와 같은 확장은 단백질 수송 및 성숙에 관여하는 소포체를 형성합니다. 그것은 단백질을 합성하는 리보솜으로 덮인 거친 소포체를 포함합니다; 이것들은 내부 공간 또는 내강으로 들어갑니다. 그 후, 그들은 일반적으로 부드러운 소포체에서 싹트는 소포체로 들어갑니다.[26] 대부분의 진핵생물에서 이러한 단백질 운반 소포는 Golgi 장치인 평평한 소포(cisternae)의 스택에서 방출되고 추가로 변형됩니다.[27]

소포는 특수화되어 있을 수 있는데, 예를 들어 리소좀에는 세포질의 생체 분자를 분해하는 소화 효소가 포함되어 있습니다.[28]

미토콘드리아

미토콘드리아는 진핵 세포의 소기관입니다. 미토콘드리아는 당이나 지방을 산화시켜 에너지를 저장하는 분자 ATP를 생성함으로써 에너지를 제공하는 기능 때문에 흔히 "세포의 강자"라고 불립니다.[29][30][31] 미토콘드리아에는 두 개의 주변 막을 가지고 있는데, 각각은 인지질 이중층이며, 그 내부는 호기성 호흡이 일어나는 크리스타(cristae)라고 불리는 함입막으로 접혀 있습니다.[32]

미토콘드리아에는 세균 DNA와 구조적으로 매우 유사하고 진핵생물 RNA보다 세균 RNA와 구조적으로 더 가까운 RNA를 생성하는 rRNA와 tRNA 유전자를 암호화하는 고유의 DNA가 들어 있습니다.[33]

메타모나드 지아르디아(Giardia)와 트리코모나스(Trichomonas), 아메바조안 펠록사(Amoebozoan Pelomyca)와 같은 일부 진핵생물은 미토콘드리아가 부족한 것처럼 보이지만 모두 하이드로게노솜(hydrogenosome)이나 미토솜(mitosome)과 같은 미토콘드리아 유래 소기관을 포함하고 있으며, 2차적으로 미토콘드리아를 잃었습니다.[34] 그들은 세포질에서 효소 작용에 의해 에너지를 얻습니다.[35][34]

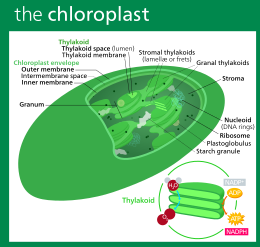

색소체

식물과 다양한 조류 그룹은 미토콘드리아뿐만 아니라 색소체를 가지고 있습니다. 색소체는 미토콘드리아와 마찬가지로 고유의 DNA를 가지고 있으며, 이 경우 시아노박테리아와 같은 내공생체에서 발달합니다. 그것들은 남조류와 같이 엽록소를 포함하고 광합성을 통해 유기 화합물(포도당과 같은)을 생성하는 엽록체의 형태를 갖습니다. 다른 사람들은 음식을 저장하는 데 관여합니다. 색소체는 아마도 단일 기원을 가지고 있었을 것이지만 모든 색소체 함유 그룹이 밀접한 관련이 있는 것은 아닙니다. 대신 일부 진핵생물은 2차 내공생 또는 섭취를 통해 다른 진핵생물로부터 그것을 얻었습니다.[36] 광합성 세포와 엽록체의 포획 및 격리, 클렙토플라스틱은 많은 유형의 현대 진핵생물에서 발생합니다.[37][38]

세포골격구조

세포골격은 세포가 움직이거나 모양을 바꾸거나 물질을 운반할 수 있는 운동 구조에 대한 강화 구조와 부착 지점을 제공합니다. 운동 구조는 액틴의 미세 필라멘트이며 α-액티닌, 핌브린 및 필라민을 포함한 액틴 결합 단백질이 막하 피질층 및 다발에 존재합니다. 미세소관의 운동 단백질, 다이네인과 키네인, 액틴 필라멘트의 미오신이 네트워크의 동적 특성을 제공합니다.[39][40]

많은 진핵생물들은 편모라고 불리는 길고 가느다란 운동성 세포질 돌기 또는 섬모라고 불리는 여러 개의 더 짧은 구조를 가지고 있습니다. 이 소기관은 움직임, 섭식, 감각에 다양하게 관여합니다. 그것들은 주로 튜불린으로 구성되어 있으며 원핵생물의 편모와는 완전히 다릅니다. 그들은 두 개의 싱글트를 둘러싸고 있는 9개의 이중선으로 특징적으로 배열된 중심 역할에서 발생하는 미세관 다발에 의해 지지됩니다. 편모는 많은 스트라메노파일처럼 털(mastigonem)을 가질 수 있습니다. 그들의 내부는 세포의 세포질과 연속적입니다.[41][42]

편모가 없는 세포와 그룹에도 구심점은 종종 존재하지만 침엽수와 개화 식물은 둘 다 없습니다. 그들은 일반적으로 다양한 미세소관 뿌리를 생성하는 그룹에서 발생합니다. 이것들은 세포골격의 주요 구성요소를 형성하며, 종종 여러 세포 분열 과정에 걸쳐 조립되며, 하나의 편모는 모체로부터 유지되고 다른 하나는 모체로부터 유래됩니다. 핵분열 과정에서 구심점이 스핀들을 생성합니다.[43]

세포벽

식물, 조류, 곰팡이 및 동물이 아닌 대부분의 크로말베올레이트의 세포는 세포벽으로 둘러싸여 있습니다. 이것은 세포막 외부의 층으로, 세포에 구조적 지지, 보호 및 여과 메커니즘을 제공합니다. 세포벽은 또한 물이 세포로 들어갈 때 과도한 팽창을 방지합니다.[44]

육상 식물의 주요 세포벽을 구성하는 주요 다당류는 셀룰로오스, 헤미셀룰로오스, 펙틴입니다. 셀룰로오스 미세섬유는 펙틴 매트릭스에 내장된 헤미셀룰로오스와 함께 연결됩니다. 1차 세포벽에서 가장 흔한 헤미셀룰로오스는 자일로글루칸입니다.[45]

성생식

진핵생물은 성생식을 수반하는 생애주기를 가지고 있는데, 각 세포에는 각 염색체의 사본이 1개씩만 존재하는 반수체상과 각 세포에는 각 염색체의 사본이 2개씩 존재하는 이배체상이 번갈아 존재합니다. 이배체상은 난자와 정자와 같은 두 개의 반수체 배우자가 융합하여 접합체를 형성하는데, 이는 유사분열에 의해 세포가 분열되어 체로 성장할 수 있으며, 어떤 단계에서는 염색체 수를 줄이고 유전적 변이성을 만드는 분열인 감수분열을 통해 반수체 배우자를 생성합니다.[46] 이 패턴에는 상당한 차이가 있습니다. 식물은 반수체 및 이배체 다세포 단계를 모두 가지고 있습니다.[47] 진핵생물은 원핵생물보다 대사 속도가 낮고 생성 시간이 길며, 그 이유는 진핵생물이 크기 때문에 부피에 대한 표면적 비율이 작기 때문입니다.[48]

성적 생식의 진화는 진핵생물의 원초적인 특징일 수 있습니다. Dacks와 Roger는 계통발생학적 분석을 바탕으로 이 그룹의 공통 조상에 통성 성이 존재한다고 제안했습니다.[49] 감수 분열에서 기능하는 핵심 유전자 세트는 이전에 무성인 것으로 생각되었던 두 유기체인 Trichomonas vaginalis와 Giardia interestinalis 모두에 존재합니다.[50][51] 이 두 종은 진핵생물 진화목에서 일찍 갈라진 계통의 후손이기 때문에 핵심 감수유전자, 따라서 성이 진핵생물의 공통 조상에 존재했을 가능성이 높습니다.[50][51] Leishmania 기생충과 같이 한때 무성으로 여겨졌던 종들은 성적인 순환을 합니다.[52] 이전에 무성으로 간주되었던 아메바는 고대에 유성이었고, 현재의 무성 그룹은 최근에 발생했을 가능성이 있습니다.[53]

진화

분류이력

고대에 아리스토텔레스와 테오프라스토스는 동물과 식물의 두 계통을 인정했습니다. 이 계통들은 18세기에 린네에 의해 왕국의 분류학적 등급을 받았습니다. 비록 그는 식물에 곰팡이를 포함시켰지만, 그것들은 꽤 뚜렷하고 별개의 왕국을 보장한다는 것을 나중에 깨달았습니다.[55] 다양한 단세포 진핵생물이 알려지게 되자 원래 식물이나 동물과 함께 놓이게 되었습니다. 1818년 독일의 생물학자 게오르크 A. 골드퓨스는 섬모와 같은 유기체를 지칭하는 원생동물이라는 단어를 만들었고,[56] 에른스트 해켈이 1866년 단세포 진핵생물인 프로티스타를 모두 아우르는 왕국으로 만들 때까지 이 그룹은 확장되었습니다.[57][58][59] 따라서 진핵생물은 4개의 왕국으로 보여지게 되었습니다.

그 당시 원생생물들은 원시적인 단세포적인 성질에 의해 연합된 "원생적인 형태", 따라서 진화적인 등급으로 생각되었습니다.[58] 생명의 나무에서 가장 오래된 가지에 대한 이해는 DNA 염기서열 분석을 통해서만 상당히 발전했고, 1990년 칼 우즈, 오토 칸들러, 마크 휠리스가 최상위 등급으로 왕국이 아닌 도메인의 체계를 제시하면서 도메인 "에우카리아"에 있는 모든 진핵생물 왕국을 통합했다고 말했습니다. ""eukary노트"는 계속 허용 가능한 공통 동의어가 될 것입니다." 1996년 진화생물학자 린 마굴리스(Lynn Margulis)는 "공생 기반 계통발생"을 만들기 위해 킹덤스와 도메인스를 "포함하는" 이름으로 대체할 것을 제안했고, "에우카리아(Eukarya, 공생에서 유래한 핵생물)"라는 설명을 제공했습니다.[4]

계통발생학

2014년까지 지난 20년간의 계통발생학적 연구에서 대략적인 합의가 나오기 시작했습니다.[9][61] 대부분의 진핵생물은 아모르페아(유니콘트 가설과 유사한 구성)와 식물과 대부분의 조류 계통을 포함하는 디포다(이전의 바이콘트)라는 두 개의 큰 분기군 중 하나에 배치될 수 있습니다. 세 번째 주요 그룹인 굴라타(Excurvata)는 병진적이기 때문에 공식적인 그룹으로 버려졌습니다.[2] 아래 제안된 계통발생학은 한 그룹의 굴(Discoba)만을 포함하며,[62] 피코조아인이 근연종이라는 2021년 제안을 포함합니다.[63] 프로보라는 2022년에 발견된 미생물 포식자 그룹입니다.[1] 메타모나다는 배치하기가 어렵습니다. 아마도 디스코바와 자매 관계일 수도 있고, 말라위모나다와도 자매 관계일 수도 있습니다.[13]

| 진핵생물 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2200mya? |

진핵생물의 기원

진핵세포의 기원, 즉 진핵생물의 기원은 생명체의 진화에 있어서 획기적인 사건인데, 진핵생물은 모든 복잡한 세포와 거의 모든 다세포 생물을 포함하기 때문입니다. 마지막 진핵생물 공통 조상(LECA)은 살아있는 모든 진핵생물의 가상적 기원이며,[65] 단일 개체가 아닌 생물학적 집단이었을 가능성이 높습니다.[66] LECA는 핵, 적어도 하나의 구심점과 편모, 통성 호기성 미토콘드리아, 성(meiosis 및 syngamy), 키틴 또는 셀룰로오스의 세포벽을 가진 휴면 낭종, 그리고 퍼옥시좀을 가진 원생생물이었던 것으로 추정됩니다.[67][68][69]

운동성 혐기성 고세균과 호기성 알파프로테오박테리움 사이의 내공생적 결합은 미토콘드리아와 함께 LECA와 모든 진핵생물을 발생시켰습니다. 두 번째, 훨씬 나중에 시아노박테리움과의 내공생은 엽록체와 함께 식물의 조상을 낳았습니다.[64]

고세균에서 진핵생물 바이오마커의 존재는 고세균 기원을 가리킵니다. 아스가르드 고세균의 유전체는 진핵생물의 특징인 세포골격과 복잡한 세포구조의 발달에 중요한 역할을 하는 진핵생물의 특징인 단백질 유전자를 많이 가지고 있습니다. 2022년, 극저온 전자 단층 촬영은 아스가르드 고세균이 복잡한 액틴 기반 세포골격을 가지고 있음을 입증하여 진핵생물의 고세균 조상에 대한 최초의 직접적인 시각적 증거를 제공했습니다.[70]

화석

진핵생물의 기원은 정확히 알 수 없지만, 16억 3천 5백만 년 전에 살았던 중국의 초기 다세포 진핵생물인 칭샤니아 마그니피아가 발견되었습니다. 왕관 그룹의 진핵생물은 후기 고생대(스타테리아어)에서 유래했을 것으로 추정되며, 약 16억 5천만 년 전에 살았던 최초의 명백한 단세포 진핵생물도 북중국에서 발견되었습니다: Tappania plana, Suiyusphaeridium macroreticulatum, Dictyospaera macroreticulata, Germinosphaera 폐포, 발레리아 로포스트리아타.[71]

최소 16억 5천만 년 전부터 알려진 아크리카치도 있고, 조류일 가능성이 있는 화석 그리파니아는 무려 21억 년이나 되었습니다.[72][73] "문제가 되는"[74] 화석 디스카그마는 22억 년 전의 고생물에서 발견되었습니다.[74]

"큰 식민지 유기체"를 나타내기 위해 제안된 구조물은 21억년 된 "프랑스 빌런 생물군"이라고 불리는 가봉의 "프랑스 빌런 B층"과 같은 고원생대의 검은 셰일에서 발견되었습니다.[75][76] 그러나 이러한 구조물의 화석으로서의 지위는 논쟁의 여지가 있으며, 다른 저자들은 이들이 유사 화석을 나타낼 수 있다고 제안합니다.[77] 진핵생물에 명확하게 할당할 수 있는 가장 오래된 화석은 중국의 루양 그룹의 것으로, 약 18억년에서 16억년 전의 것입니다.[78] 현대 그룹과 분명히 관련이 있는 화석은 12억 년 전으로 추정되는 홍조류의 형태로 나타나기 시작하지만, 최근 연구에 따르면 아마도 16억~17억 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는 빈디야 분지에 화석화된 사상성 조류가 존재한다고 합니다.[79]

호주 셰일에 진핵생물 특이적 바이오마커인 스테란이 존재한다는 것은 이전에 27억 년 전의 이 암석들에 진핵생물이 존재한다는 것을 시사했지만,[20][80] 이 고세균 바이오마커들은 나중의 오염물질로 반박되었습니다.[81] 가장 오래된 유효한 바이오마커 기록은 약 8억 년에 불과합니다.[82] 이와는 대조적으로 분자시계 분석을 통해 이르면 23억 년 전에 스테롤 생합성이 출현했음을 알 수 있습니다.[83] 스테란의 진핵생물 바이오마커로서의 특성은 일부 박테리아에 의한 스테롤 생성으로 인해 더욱 복잡해집니다.[84][85]

진핵생물은 그 기원이 언제든지 생태학적으로 지배적이 되었을 수 있습니다. 8억년 전 해양 퇴적물의 아연 조성이 크게 증가한 것은 원핵생물에 비해 아연을 우선적으로 소비하고 흡수하는 진핵생물의 상당한 수의 증가에 기인합니다. (늦어도)[86] 그로부터 약 10억 년 후에

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b Tikhonenkov DV, Mikhailov KV, Gawryluk RM, et al. (December 2022). "Microbial predators form a new supergroup of eukaryotes". Nature. 612 (7941): 714–719. Bibcode:2022Natur.612..714T. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05511-5. PMID 36477531. S2CID 254436650.

- ^ a b Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, et al. (January 2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ a b Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–4579. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ a b Margulis L (6 February 1996). "Archaeal-eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: phylogenetic classification of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 93 (3): 1071–1076. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.1071M. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.3.1071. PMC 40032. PMID 8577716.

- ^ Seenivasan R, Sausen N, Medlin LK, Melkonian M (26 March 2013). "Picomonas judraskeda Gen. Et Sp. Nov.: The First Identified Member of the Picozoa Phylum Nov., a Widespread Group of Picoeukaryotes, Formerly Known as 'Picobiliphytes'". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e59565. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859565S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059565. PMC 3608682. PMID 23555709.

- ^ Wood G (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ Earle CJ, ed. (2017). "Sequoia sempervirens". The Gymnosperm Database. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ van den Hoek C, Mann D, Jahns H (1995). Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30419-9. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b Burki F (May 2014). "The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (5): a016147. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016147. PMC 3996474. PMID 24789819.

- ^ DeRennaux B (2001). "Eukaryotes, Origin of". Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. Vol. 2. Elsevier. pp. 329–332. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384719-5.00174-x. ISBN 9780123847201.

- ^ Yamaguchi M, Worman CO (2014). "Deep-sea microorganisms and the origin of the eukaryotic cell" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Protozoology. 47 (1, 2): 29–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017.

- ^ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (17 May 2018). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ a b c Burki F, Roger AJ, Brown MW, Simpson AG (2020). "The New Tree of Eukaryotes". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV. 35 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 31606140. S2CID 204545629.

- ^ Grosberg RK, Strathmann RR (2007). "The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?" (PDF). Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 38: 621–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Parfrey L, Lahr D (2013). "Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes" (PDF). BioEssays. 35 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1002/bies.201200143. PMID 23315654. S2CID 13872783. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Popper ZA, Michel G, Hervé C, Domozych DS, Willats WG, Tuohy MG, Kloareg B, Stengel DB (2011). "Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: From algae to flowering plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 62: 567–590. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809. hdl:10379/6762. PMID 21351878. S2CID 11961888.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "eukaryotic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Bonev B, Cavalli G (14 October 2016). "Organization and function of the 3D genome". Nature Reviews Genetics. 17 (11): 661–678. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.112. hdl:2027.42/151884. PMID 27739532. S2CID 31259189.

- ^ "Mitosis - an overview". ScienceDirect Topics. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b Brocks JJ, Logan GA, Buick R, Summons RE (August 1999). "Archean molecular fossils and the early rise of eukaryotes". Science. 285 (5430): 1033–1036. Bibcode:1999Sci...285.1033B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.516.9123. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033. PMID 10446042.

- ^ Hartman H, Fedorov A (February 2002). "The origin of the eukaryotic cell: a genomic investigation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (3): 1420–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1420H. doi:10.1073/pnas.032658599. PMC 122206. PMID 11805300.

- ^ Linka M, Weber AP (2011). "Evolutionary Integration of Chloroplast Metabolism with the Metabolic Networks of the Cells". In Burnap RL, Vermaas WF (eds.). Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-94-007-1533-2. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Marsh M (2001). Endocytosis. Oxford University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-963851-2.

- ^ Stalder D, Gershlick DC (November 2020). "Direct trafficking pathways from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 107: 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.04.001. PMC 7152905. PMID 32317144.

- ^ Hetzer MW (March 2010). "The nuclear envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (3): a000539. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMC 2829960. PMID 20300205.

- ^ "Endoplasmic Reticulum (Rough and Smooth)". British Society for Cell Biology. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Golgi Apparatus". British Society for Cell Biology. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Lysosome". British Society for Cell Biology. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, et al. (July 1957). "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension". Pulmonary Circulation. 10 (1): 131–144. Bibcode:1957SciAm.197a.131S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0757-131. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015.

- ^ Voet D, Voet JC, Pratt CW (2006). Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 547, 556. ISBN 978-0471214953.

- ^ Mack S (1 May 2006). "Re: Are there eukaryotic cells without mitochondria?". madsci.org. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Zick M, Rabl R, Reichert AS (January 2009). "Cristae formation-linking ultrastructure and function of mitochondria". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1793 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.013. PMID 18620004.

- ^ Watson J, Hopkins N, Roberts J, Steitz JA, Weiner A (1988). "28: The Origins of Life". Molecular Biology of the Gene (Fourth ed.). Menlo Park, California: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc. p. 1154. ISBN 978-0-8053-9614-0.

- ^ a b Karnkowska A, Vacek V, Zubáčová Z, et al. (May 2016). "A Eukaryote without a Mitochondrial Organelle". Current Biology. 26 (10): 1274–1284. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.053. PMID 27185558.

- ^ Davis JL (13 May 2016). "Scientists Shocked To Discover Eukaryote With NO Mitochondria". IFL Science. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Sato N (2006). "Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids". In Wise RR, Hoober JK (eds.). The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 23. Springer Netherlands. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ^ Minnhagen S, Carvalho WF, Salomon PS, Janson S (September 2008). "Chloroplast DNA content in Dinophysis (Dinophyceae) from different cell cycle stages is consistent with kleptoplasty". Environ. Microbiol. 10 (9): 2411–7. Bibcode:2008EnvMi..10.2411M. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01666.x. PMID 18518896.

- ^ Bodył A (February 2018). "Did some red alga-derived plastids evolve via kleptoplastidy? A hypothesis". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 93 (1): 201–222. doi:10.1111/brv.12340. PMID 28544184. S2CID 24613863.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (1 January 2002). "Molecular Motors". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Sweeney HL, Holzbaur EL (May 2018). "Motor Proteins". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 10 (5): a021931. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021931. PMC 5932582. PMID 29716949.

- ^ Bardy SL, Ng SY, Jarrell KF (February 2003). "Prokaryotic motility structures". Microbiology. 149 (Pt 2): 295–304. doi:10.1099/mic.0.25948-0. PMID 12624192.

- ^ Silflow CD, Lefebvre PA (December 2001). "Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii". Plant Physiology. 127 (4): 1500–7. doi:10.1104/pp.010807. PMC 1540183. PMID 11743094.

- ^ Vorobjev IA, Nadezhdina ES (1987). The centrosome and its role in the organization of microtubules. International Review of Cytology. Vol. 106. pp. 227–293. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61714-3. ISBN 978-0-12-364506-7. PMID 3294718.

- ^ Howland JL (2000). The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-19-511183-5.

- ^ Fry SC (1989). "The Structure and Functions of Xyloglucan". Journal of Experimental Botany. 40 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1093/jxb/40.1.1.

- ^ Hamilton MB (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0.

- ^ Taylor TN, Kerp H, Hass H (2005). "Life history biology of early land plants: Deciphering the gametophyte phase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (16): 5892–5897. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501985102. PMC 556298. PMID 15809414.

- ^ Lane N (June 2011). "Energetics and genetics across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide". Biology Direct. 6 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-35. PMC 3152533. PMID 21714941.

- ^ Dacks J, Roger AJ (June 1999). "The first sexual lineage and the relevance of facultative sex". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 48 (6): 779–783. Bibcode:1999JMolE..48..779D. doi:10.1007/PL00013156. PMID 10229582. S2CID 9441768.

- ^ a b Ramesh MA, Malik SB, Logsdon JM (January 2005). "A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis". Current Biology. 15 (2): 185–191. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.003. PMID 15668177. S2CID 17013247.

- ^ a b Malik SB, Pightling AW, Stefaniak LM, Schurko AM, Logsdon JM (August 2007). Hahn MW (ed.). "An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in Trichomonas vaginalis". PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e2879. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2879M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002879. PMC 2488364. PMID 18663385.

- ^ Akopyants NS, Kimblin N, Secundino N, Patrick R, Peters N, Lawyer P, Dobson DE, Beverley SM, Sacks DL (April 2009). "Demonstration of genetic exchange during cyclical development of Leishmania in the sand fly vector". Science. 324 (5924): 265–268. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..265A. doi:10.1126/science.1169464. PMC 2729066. PMID 19359589.

- ^ Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (July 2011). "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 278 (1715): 2081–2090. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637. PMID 21429931.

- ^ Patrick J. Keeling; Yana Eglit (21 November 2023). "Openly available illustrations as tools to describe eukaryotic microbial diversity". PLOS Biology. 21 (11): e3002395. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.3002395. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 10662721. PMID 37988341. Wikidata Q123558544.

- ^ Moore RT (1980). "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina. 23: 361–373.

- ^ Goldfuß (1818). "Ueber die Classification der Zoophyten" [On the classification of zoophytes]. Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken (in German). 2 (6): 1008–1019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019. 1008쪽부터: "에르스테 클라세. 우르티에. 원생동물"(1교시. 원시 동물. 원생동물(원생동물) [참고: 이 저널의 각 페이지의 각 열에는 번호가 매겨져 있습니다. 한 페이지에 두 개의 열이 있습니다.]

- ^ Scamardella JM (1999). "Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista" (PDF). International Microbiology. 2 (4): 207–221. PMID 10943416. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011.

- ^ a b Rothschild LJ (1989). "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?". Journal of the History of Biology. 22 (2): 277–305. doi:10.1007/BF00139515. PMID 11542176. S2CID 32462158. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Whittaker RH (January 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–60. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.5430. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ Knoll AH (1992). "The Early Evolution of Eukaryotes: A Geological Perspective". Science. 256 (5057): 622–627. Bibcode:1992Sci...256..622K. doi:10.1126/science.1585174. PMID 1585174.

Eucarya, or eukaryotes

- ^ Burki F, Kaplan M, Tikhonenkov DV, et al. (January 2016). "Untangling the early diversification of eukaryotes: a phylogenomic study of the evolutionary origins of Centrohelida, Haptophyta and Cryptista". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 283 (1823): 20152802. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2802. PMC 4795036. PMID 26817772.

- ^ Brown MW, Heiss AA, Kamikawa R, Inagaki Y, Yabuki A, Tice AK, Shiratori T, Ishida K, Hashimoto T, Simpson A, Roger A (19 January 2018). "Phylogenomics Places Orphan Protistan Lineages in a Novel Eukaryotic Super-Group". Genome Biology and Evolution. 10 (2): 427–433. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy014. PMC 5793813. PMID 29360967.

- ^ Schön ME, Zlatogursky VV, Singh RP, et al. (2021). "Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6651. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.04.14.439778. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26918-0. PMC 8599508. PMID 34789758. S2CID 233328713. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ a b Latorre A, Durban A, Moya A, Pereto J (2011). "The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". In Gargaud M, López-Garcìa P, Martin H (eds.). Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Gabaldón T (October 2021). "Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell". Annual Review of Microbiology. 75 (1): 631–647. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213. PMID 34343017. S2CID 236916203.

- ^ O'Malley MA, Leger MM, Wideman JG, Ruiz-Trillo I (March 2019). "Concepts of the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (3): 338–344. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3..338O. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0796-3. hdl:10261/201794. PMID 30778187. S2CID 67790751.

- ^ Leander BS (May 2020). "Predatory protists". Current Biology. 30 (10): R510–R516. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.052. PMID 32428491. S2CID 218710816.

- ^ Strassert JF, Irisarri I, Williams TA, Burki F (March 2021). "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 1879. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.1879S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. PMC 7994803. PMID 33767194.

- ^ Koumandou VL, Wickstead B, Ginger ML, van der Giezen M, Dacks JB, Field MC (2013). "Molecular paleontology and complexity in the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 48 (4): 373–396. doi:10.3109/10409238.2013.821444. PMC 3791482. PMID 23895660.

- ^ Rodrigues-Oliveira T, Wollweber F, Ponce-Toledo RI, et al. (2023). "Actin cytoskeleton and complex cell architecture in an Asgard archaean". Nature. 613 (7943): 332–339. Bibcode:2023Natur.613..332R. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05550-y. hdl:20.500.11850/589210. PMC 9834061. PMID 36544020.

- ^ Miao, L.; Yin, Z.; Knoll, A. H.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, M. (2024). "1.63-billion-year-old multicellular eukaryotes from the Chuanlinggou Formation in North China". Science Advances. 10 (4): eadk3208. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adk3208. PMC 10807817. PMID 38266082.

- ^ Han TM, Runnegar B (July 1992). "Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old negaunee iron-formation, Michigan". Science. 257 (5067): 232–5. Bibcode:1992Sci...257..232H. doi:10.1126/science.1631544. PMID 1631544.

- ^ Knoll AH, Javaux EJ, Hewitt D, Cohen P (June 2006). "Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 361 (1470): 1023–1038. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. PMC 1578724. PMID 16754612.

- ^ a b c Retallack GJ, Krull ES, Thackray GD, Parkinson DH (2013). "Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa". Precambrian Research. 235: 71–87. Bibcode:2013PreR..235...71R. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2013.05.015.

- ^ El Albani A, Bengtson S, Canfield DE, et al. (July 2010). "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature. 466 (7302): 100–104. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..100A. doi:10.1038/nature09166. PMID 20596019. S2CID 4331375.

- ^ El Albani, Abderrazak (2023). "A search for life in Palaeoproterozoic marine sediments using Zn isotopes and geochemistry". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 623: 118169. Bibcode:2023E&PSL.61218169E. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118169. S2CID 258360867.

- ^ Ossa Ossa, Frantz; Pons, Marie-Laure; Bekker, Andrey; Hofmann, Axel; Poulton, Simon W.; et al. (2023). "Zinc enrichment and isotopic fractionation in a marine habitat of the c. 2.1 Ga Francevillian Group: A signature of zinc utilization by eukaryotes?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 611: 118147. Bibcode:2023E&PSL.61118147O. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118147.

- ^ Fakhraee, Mojtaba; Tarhan, Lidya G.; Reinhard, Christopher T.; Crowe, Sean A.; Lyons, Timothy W.; Planavsky, Noah J. (May 2023). "Earth's surface oxygenation and the rise of eukaryotic life: Relationships to the Lomagundi positive carbon isotope excursion revisited". Earth-Science Reviews. 240: 104398. Bibcode:2023ESRv..24004398F. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104398. S2CID 257761993. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Bengtson S, Belivanova V, Rasmussen B, Whitehouse M (May 2009). "The controversial "Cambrian" fossils of the Vindhyan are real but more than a billion years older". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (19): 7729–7734. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7729B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812460106. PMC 2683128. PMID 19416859.

- ^ Ward P (9 February 2008). "Mass extinctions: the microbes strike back". New Scientist. pp. 40–43. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ French KL, Hallmann C, Hope JM, Schoon PL, Zumberge JA, Hoshino Y, Peters CA, George SC, Love GD, Brocks JJ, Buick R, Summons RE (May 2015). "Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (19): 5915–5920. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5915F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419563112. PMC 4434754. PMID 25918387.

- ^ Brocks JJ, Jarrett AJ, Sirantoine E, Hallmann C, Hoshino Y, Liyanage T (August 2017). "The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals". Nature. 548 (7669): 578–581. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..578B. doi:10.1038/nature23457. PMID 28813409. S2CID 205258987.

- ^ Gold DA, Caron A, Fournier GP, Summons RE (March 2017). "Paleoproterozoic sterol biosynthesis and the rise of oxygen". Nature. 543 (7645): 420–423. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..420G. doi:10.1038/nature21412. hdl:1721.1/128450. PMID 28264195. S2CID 205254122.

- ^ Wei JH, Yin X, Welander PV (24 June 2016). "Sterol Synthesis in Diverse Bacteria". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 990. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00990. PMC 4919349. PMID 27446030.

- ^ Hoshino Y, Gaucher EA (June 2021). "Evolution of bacterial steroid biosynthesis and its impact on eukaryogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (25): e2101276118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11801276H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. PMC 8237579. PMID 34131078.

- ^ Isson TT, Love GD, Dupont CL, et al. (June 2018). "Tracking the rise of eukaryotes to ecological dominance with zinc isotopes". Geobiology. 16 (4): 341–352. Bibcode:2018Gbio...16..341I. doi:10.1111/gbi.12289. PMID 29869832.