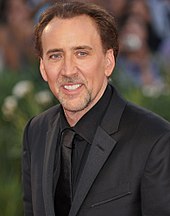

니콜라스 케이지

Nicolas Cage니콜라스 케이지 | |

|---|---|

2011년 샌디에이고 코믹콘 케이지 | |

| 태어난 | 니콜라스 김 코폴라 1964년 1월 7일 |

| 직업 | 배우,영화제작자 |

| 활동년수 | 1981~현재 |

| 작동하다 | 전체리스트 |

| 배우자 |

|

| 아이들. | 3 |

| 가족 | 코폴라 |

| 상 | 전체리스트 |

니콜라스 케이지([1][2]Nicolas Cage)라는 예명으로 알려진 니콜라스 김 코폴라(Nicolas Kim Coppola, 1964년 1월 7일 ~ )는 미국의 배우, 영화 프로듀서입니다. 그는 아카데미상, 영화배우조합상, 골든글로브상 등 다양한 상을 수상했습니다. 배우로서의 다재다능함으로 유명한 그는 다양한 영화 장르에 참여하여 컬트 추종자가 되었습니다.[3][4][5][6]

코폴라 가문에서 태어난 케이지는 리지몬트 고등학교 (1982)와 밸리 걸 (1983)과 같은 영화와 럼블 피쉬 (1983), 코튼 클럽 (1984), 페기 수 결혼 (1986)과 같은 삼촌 프랜시스 포드 코폴라의 다양한 영화에서 경력을 시작했습니다. 그는 문스트럭(1987)과 라이징 애리조나(1987)에서의 역할로 비평가들의 호평을 받았고, 극적인 영화 라스베가스(1995)에서의 연기로 아카데미 남우주연상을 받았습니다. 그는 2002년 코미디 드라마 영화 '어댑션'(2002)에서 쌍둥이 찰리와 도널드 카우프만 역을 맡아 아카데미상 후보에 올랐습니다.

케이지는 The Rock (1996), Con Air (1997), Face/Off (1997), Gone in 60 Seconds (2000), National Treasury 영화 시리즈 (2004–2007), Ghost Rider 영화 시리즈 (2007–2011), Kick-Ass (2010)와 같은 주류 액션 영화에서 입지를 다졌습니다. 그는 또한 "City of Angels" (1998), "Broading Out the Dead" (1999), 그리고 "The Family Man" (2000)에서 극적인 역할을 맡았습니다. 그는 더 크룩스 프랜차이즈 (2013 ~ 현재)와 스파이더맨: 인투 더 스파이더맨 (2018)에서 목소리 연기를 했습니다. 그는 맨디(2018), 피그(2021), 거대한 재능의 참을 수 없는 무게(2022), 그리고 꿈의 시나리오(2023)에서 주연으로 다시 주목받았습니다.[7][8][9]

케이지는 제작사 새턴 필름스를 소유하고 있으며 '뱀파이어의 그림자'(2000), '데이비드 게일의 삶'(2003) 등의 영화를 제작했으며 소니(2002)를 감독했습니다. 그는 2007년 엠파이어 매거진의 역대 최고의 영화 스타 100인 목록에서 40위에 올랐고, 2008년 프리미어지의 할리우드에서 가장 영향력 있는 100인에 37위에 올랐습니다.

초기의 삶과 가족

케이지(Cage)는 캘리포니아 롱비치(Long Beach)에서 문학 교수 어거스트 코폴라(August Coppola)와 댄서이자 안무가인 조이 보겔상(Joy Vogelsang) 사이에서 태어났습니다. 그는 가톨릭 집안에서 자랐습니다. 그의 아버지는 이탈리아 혈통이었고, 어머니는 주로 독일과 폴란드 혈통이었고, 아버지 쪽에는 영국과 스코틀랜드 혈통이 있었습니다.[10][11][12] 그의 친조부모는 작곡가 카르미네 코폴라와 배우 이탈리아 페니노였고, 그의 친증조부모는 바실리카타의 베르날다에서 온 이민자였습니다.[13] 아버지를 통해 감독 프란시스 포드 코폴라와 배우 탈리아 샤이어의 조카이자 감독 로만 코폴라와 소피아 코폴라, 영화 제작자 지안 카를로 코폴라, 배우 로버트와 제이슨 슈워츠먼의 사촌입니다.[14][15]

케이지는 세 아들 중 막내입니다. 그의 두 형제는 뉴욕의 라디오 스타 마크 코폴라와 크리스토퍼 코폴라 감독입니다. 그는 연예인이 된 많은 동문들로 유명한 [16]베벌리힐스 고등학교를 다녔습니다. 그는 어린 시절부터 연기를 꿈꿨고 UCLA 연극, 영화, 텔레비전 학교에도 다녔습니다. 그의 첫 번째 비영화적인 연기 경험은 골든 보이의 학교 작품에서였습니다.[17] 그는 "제임스 딘이 되고 싶어서" 연기를 시작했다고 말했습니다. 에덴 동쪽에 있는 '이유 없는 반란'에서 봤어요 에덴에서 딘이 나에게 영향을 주었던 것처럼, 록 노래도, 클래식 음악도, 아무 것도 나에게 영향을 주지 않았습니다. 제 마음을 날려버렸어요. '내가 하고 싶은 게 바로 그거야'라고 생각했어요."[18]

15살 때, 그는 삼촌인 프란시스 포드 코폴라에게 "연기를 보여줄게"라고 말하면서 스크린 테스트를 해보라고 설득하려고 했습니다. 그의 감정 폭발은 "차 안에서의 침묵"과 마주쳤습니다.[19] 코폴라는 이미 말론 브란도, 알 파치노, 진 핵맨, 로버트 드 니로를 감독했습니다. 그의 경력 초기에 케이지는 그의 삼촌의 몇몇 영화에 출연했지만, 그는 코폴라의 조카로 족벌주의가 나타나는 것을 피하기 위해 그의 이름을 니콜라스 케이지로 바꿨습니다. 그의 이름 선택은 마블 코믹스의 슈퍼히어로 루크 케이지와 작곡가 존 케이지에 의해 영감을 받았습니다.[20][21]

직업

1981~1988년: 초기 작업과 획기적인 전환

케이지(Cage)는 1981년 TV 파일럿 더 베스트 오브 타임스(The Best of Times)에서 연기 데뷔를 했는데, ABC는 이 영화를 본 적이 없습니다.[22] 그의 영화 데뷔는 1982년에 이루어졌는데, 그는 리지몬트 고등학교의 성인 영화 패스트 타임즈에서 라인홀드 역을 위해 오디션을 본 적이 있는 심사위원의 이름 없는 동료 역할을 맡았습니다.[23] 그 영화에 대한 그의 경험은 출연진들이 그의 삼촌의 영화들을 끝없이 인용하는 것으로 얼룩졌고, 이것은 그가 이름을 바꾸도록 영감을 주었습니다.[23]

케이지의 첫 주연은 로맨틱 코미디 밸리 걸 (1983)에서 데보라 포맨의 상대역으로 나왔는데, 그는 로미오와 줄리엣에 의해 느슨하게 영감을 받은 줄거리인 제목의 밸리 걸과 사랑에 빠지는 펑크 역할을 맡았습니다.[24] 이 영화는 약간의 흥행 성공을 거두었고 컬트 클래식으로 낙인찍혔습니다.[25] 그는 S.E.를 기반으로 한 그의 삼촌의 영화 아웃사이더에서 달라스 윈스턴의 역할을 위해 오디션을 봤습니다. 힌튼의 소설이지만 맷 딜런에게 졌습니다.[26] 하지만 케이지는 그해에 코폴라 감독의 또 다른 힌튼 소설 럼블 피쉬를 각색한 작품에 공동 주연을 맡았습니다.[27]

1984년, 케이지는 세 편의 영화에 출연했는데, 그 중 어느 영화도 박스오피스에서 좋은 성적을 거두지 못했습니다. 드라마 '레이싱 위드 더 문(1984)'에서 케이지는 숀 펜의 상대역으로 미 해병대 배치를 기다리는 친구로 등장했습니다.[28] 코폴라의 범죄 드라마 코튼 클럽에서 그는 범죄극인 빈센트 "매드 도그" 콜의 허구화된 버전을 연기했고, 비평가 폴 아타나시오로부터 "몸이 건장하고 폭력적인 깡패를 그리기 위해 그의 몇 순간을 예술적으로 사용했다"는 찬사를 받았습니다.[29] 올해의 그의 마지막 개봉작은 앨런 파커의 드라마 버디로, 그는 매튜 모딘과 함께 베트남 전쟁에서 복무하면서 입은 상처와 두 명의 친한 친구로 출연했습니다. 케이지는 그 역할을 위해 체중을 감량했고, 앞니 두 개를 빼내어 몸이 망가진 것처럼 보이게 했습니다.[30] 박스오피스에서 엄청난 저조한 성적에도 불구하고, 이 영화와 케이지와 모딘의 연기는 긍정적인 평가를 받았고, 뉴욕 타임즈의 비평가 자넷 매슬린은 "케이지 씨는 알의 절박함과 좌절감을 매우 동정적으로 포착합니다. 이 배우들은 함께 연기할 수 없었던 것을 가지고 기적을 만듭니다."[31]

1986년, 케이지는 거의 볼 수 없는 캐나다 스포츠 드라마 "The Boy in Blue"와 그의 삼촌의 판타지 코미디 "Peggy Sue Got Married" (1987)에서 고등학교 시절로 여행을 떠난 캐슬린 터너 캐릭터의 남편으로 출연했습니다.[32][33] 그 후 그는 코엔 형제의 범죄 코미디 라이징 애리조나 (1987)에서 우둔한 전 사기꾼 역으로 출연했습니다.[34]

케이지의 가장 큰 돌파구는 1987년 로맨틱 코미디 문스트럭으로, 그는 소원해진 형의 홀아비 약혼자와 사랑에 빠지는 다혈질의 제빵사로 셰어와 함께 출연했습니다.[21] 이 영화는 비평가들과 관객들 모두에게 히트를 쳐서 케이지에게 골든 글로브 남우주연상 – 영화 뮤지컬 또는 코미디[35] 부문 후보에 올랐습니다. 그의 회고적인 리뷰에서 로저 에버트는 케이지의 연기가 오스카상을 받을 만한 가치가 있다고 느꼈다고 썼습니다.[36]

1989-1994: 커리어 슬럼프

1989년, 케이지는 블랙 코미디 영화 뱀파이어의 키스에서 뱀파이어와 사랑에 빠지고 곧 자신을 뱀파이어라고 믿기 시작하는 남자로 출연했습니다. 이 영화는 주요한 흥행 실패작이었지만 주로 인터넷 밈에 등장하는 케이지의 초현실주의적이고 과장된 연기로 인해 컬트 팔로잉이 발전했습니다. 비평가 빈센트 캔비는 이 영화가 "케이지 씨의 혼란스럽고 독선적인 연기에 의해 지배되고 파괴되었다"고 생각했습니다.[37] 짐바브웨에서 이탈리아 드라마 '타임 투 킬(Time to Kill, 1989)'을 촬영한 후, 그는 로라 던과 함께 데이비드 린치 감독의 로맨틱 범죄 영화 '와일드 앳 하트(Wild at Heart, 1990)'에서 케이지의 캐릭터 '세일러' 리플리를 죽이기 위해 고용된 조폭들로부터 도망치는 한 쌍의 연인으로 출연했습니다. 케이지는 "항상 열정적이고, 거의 억제되지 않은 로맨틱한 캐릭터에 끌렸고, 세일러가 노래하는 장면에서 그의 영웅 중 한 명인 엘비스 프레슬리를 흉내 낼 수 있었기 때문에 이 프로젝트에 끌렸습니다.[21][38] '와일드 앳 하트'는 1990년 칸 영화제 황금종려상 수상 논란에도 불구하고 개봉과 동시에 엇갈린 평가를 받았습니다.[39] 케이지는 아방가르드 콘서트 공연 인더스트리얼 심포니 1번을 위해 린치, 던과 재회할 예정입니다.[40]

또한 1990년, 그는 탑건(1986)과 비교하여 비평가들에 의해 혹평된 액션 영화 파이어 버드(Fire Birds)에서 헬리콥터 조종사로 출연했습니다.[41] 케이지의 다음 작품인 에로틱 스릴러 영화 잔달리(1991)는 미국에서 직접 영상으로 개봉했지만 극장 개봉은 받지 못했습니다.[42] 로맨틱 코미디 허니문 인 베가스 (1992)에서 그의 "모든 사람들에게 친절한" 연기는 몇몇 긍정적인 비평가들이 그의 연기가 "과도하다"고 생각하는 가운데 케이지를 옹호하고 케이지를 두 번째 골든 글로브에 지명하게 한 로저 에버트의 연기를 [43]포함하여 몇몇 긍정적인 비평가들의 주목을 받았습니다.[44][35] 그는 이 영화를 홍보하기 위해 버라이어티 쇼 새터데이 나이트 라이브의 한 회를 진행했는데, 그의 유일한 진행자였습니다.[45]

1993년 케이지 감독의 세 영화, 즉 데드폴(그의 형 크리스토퍼 감독), 아모스 & 앤드류 그리고 레드록 웨스트는 박스 오피스에서 좋은 성적을 거두지 못했지만, 그가 히트맨으로 오인된 표류기를 연기한 마지막 언급된 네오 느와르 스릴러는 비평가들로부터 찬사를 받았습니다.[46] 코미디 가디언 테스 (1994)는 전직 영부인을 보호하는 비밀경호국 요원으로서 케이지와 셜리 맥레인을 짝지었지만, 일부 비평가들에 의해 그것이 파생적인 것으로 치부되었습니다.[47] 그는 다음으로 로맨틱 코미디 영화 '너에게 일어날 수도 있어'에서 돈에 쪼들린 경찰관 역으로 브리짓 폰다와 함께 주연을 맡았는데, 그는 복권 당첨금을 웨이트리스와 나누겠다고 제안했고, 그 후 많은 비판을 받았던 흥행 실패작 '낙원에 갇힌 크리스마스' 코미디 영화 '새터데이 나이트 라이브' 배우 존 로비츠와 다나 카비와 함께 출연했습니다.[48][49] 로비츠에 따르면, 케이지 감독이 조지 갈로가 거의 연출을 제시하지 않았기 때문에 케이지가 이 영화의 일부를 감독했다고 합니다.[50]

1995년 ~ 2003년: 결정적 성공과 액션 스타

범죄 영화 죽음의 키스(1995)에서 사이코패스 범죄자 킹핀 역할을 한 케이지의 연기는 많은 비평가들에게 이 영화의 강점으로 여겨졌지만,[51] 그의 가장 호평을 받은 연기는 라스베가스에서 매춘부와 사랑에 빠지는 알코올 중독 시나리오 작가로서 라스베가스를 떠나다라는 드라마에서 나왔습니다.[52] 이 역할은 아카데미 남우주연상과 골든 글로브 남우주연상을 수상했습니다. 그 부분을 준비하기 위해 케이지는 2주 동안 폭음을 했고 자신의 영상을 연구했습니다.[53]

1996년, 그는 마이클 베이의 "The Rock"에서 숀 코너리, 에드 해리스와 함께 주연을 맡았는데, 이 영화는 케이지를 위한 일련의 액션 영화들 중 첫 번째 작품입니다. 이 영화에서 그는 알카트라즈 연방 교도소에 침입한 FBI 화학무기 전문가를 연기했습니다. 더 락은 흥행과 비평가들의 호평을 받았는데, 알렉산더 라먼은 이 영화가 "케이지를 엇박자 액션 스타로서 예상치 못한 직업으로 시작시켰다"고 언급했습니다.[54]

그 다음, 그는 1997년 6월에 출시된 상업적으로 성공한 두 개의 액션 스릴러인 Con Air와 Face/Off에 출연했습니다. 존 쿠삭, 존 말코비치와 함께 케이지는 미국 마셜 항공기를 타고 탈옥 시도를 저지해야 하는 가석방자로 콘 에어에 캐스팅된 앙상블을 이끌었습니다. 이 영화의 제작자인 제리 부룩하이머는 '라스베가스를 떠나'와 '더 락'에서의 그의 연기에 깊은 인상을 받은 후 케이지에게 그 역할을 제안했습니다. 케이지는 악역 제의를 받지 못한 것에 실망했음에도 불구하고 수락했습니다.[55] 에버트는 케이지가 "잘못된 선택을 했다"고 생각했습니다. 캐머런 포를 매우, 매우 성실하고, 터널 시야로 모든 일에 접근하는 느림보 엘비스 타입으로 연기함으로써, 그가 건초종자가 아니었다면 더 재미있을 것입니다."[56]

존 우(John Woo)의 페이스/오프(Face/Off)는 케이지(Cage)와 존 트라볼타(John Travolta)가 서로를 사칭하기 위해 얼굴 이식 수술을 받고, 케이지와 트라볼타가 캐릭터를 바꾸도록 요구하는 2인 1역의 적으로 출연하는 것을 보았습니다. 두 공연 모두 비평가들로부터 찬사를 받았는데, BBC는 그들의 리뷰에서 "트라볼타와 케이지는 상대 배우의 성격을 반영하는 신체적인 미묘함으로 이중 역할을 투자한다"고 썼습니다.[57]

이 액션 영화들에 연속으로 출연한 후, 케이지는 한 여자(멕 라이언 분)와 사랑에 빠지는 천사를 연기한 독일 영화 욕망의 날개(1987)의 느슨한 리메이크작인 로맨틱 판타지 영화 시티 오브 엔젤스(1998)에서 "더 진지한 이별로 돌아가기로" 결정했습니다. 비평가들은 영화와 케이지의 연기에 대해 의견이 갈렸고, 그를 "끝도 없이 지략이 풍부하다"고 묘사하는 것과 "천사보다 더 연쇄 살인범을 닮았다"는 등의 다양한 평가를 받았습니다.[58][59] 1998년 그의 두 번째 영화인 Brian De Palma의 스릴러인 Snake Eyes는 그가 참석하고 있는 복싱 경기에서 정치적인 암살을 수사하는 부패한 형사로 케이지가 주연을 맡았습니다.[60] 이 영화는 각본에 대해 대체로 비판적이었던 엇갈린 평가를 받았습니다.[61]

다른 영화들로는 마틴 스코세이지의 1999년 뉴욕시 구급대원 드라마 '죽은[21] 자를 꺼내다'와 리들리 스콧의 2003년 블랙 코미디 범죄 영화 '성냥개비 맨'이 포함되어 있는데, 이 영화에서 그는 강박장애를 가진 사기꾼 역할을 맡았습니다.[62] 재정적인 성공을 거둔 케이지의 영화 대부분은 액션/어드벤처 장르였습니다. 여기에는 더 락,[63] 콘 에어,[64] 페이스 오프,[65] 60초 만에 사라짐이 포함되며 케이지는 은퇴한 자동차 도둑입니다.[66]

그는 2001년 영화 '캡틴 코렐리의 만돌린'에서 주연을 맡아 처음부터 만돌린을 연기하는 법을 배웠습니다.[67][68] 2002년, 그는 각색에서 실제 시나리오 작가 찰리 카우프만과 카우프만의 가상의 쌍둥이 도널드 역으로 오스카와 골든 글로브 남우주연상 후보에 다시 올랐습니다.[69]

2004-2011: 프랜차이즈 영화

지금까지 두 번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화 국보에서 그는 미국 건국의 아버지들이 숨겨놓은 보물을 찾기 위해 위험한 모험을 떠나는 괴짜 역사가 역을 맡았습니다.[70] 2005년, 그가 주연을 맡았던 두 영화, "Lord of War"와 "The Weather Man"[71]은 전국적인 개봉과 그의 연기에 대한 좋은 평가에도 불구하고 이렇다 할 관객을 찾지 못했습니다.[72] 2006년 리메이크된 '위커맨'은 매우 저조한 평가를 받았고, 4천만 달러의 예산을 회수하지 못했습니다.[73][74] 마블 코믹스의 캐릭터를 기반으로 하여 많은 비판을 받은 고스트 라이더(2007)는 개봉 주말 동안 4,500만 달러 이상을 벌어들였고, 2007년 3월 25일에 끝나는 주말까지 전 세계적으로 2억 8,000만 달러 이상을 벌었습니다.[75] 또한 2007년, 그는 작지만 주목할 만한 중국의 범죄 주모자 닥터 역할을 맡았습니다. 롭 좀비의 가짜 예고편 '늑대인간 S.S.의 여자들'의 푸 만추는 B-영화 이중 장편 영화 '그린드하우스[76]'의 '늑대인간'에 출연했고 케이지의 영화 [77]'패밀리맨'(2000)과 대체 타임라인을 엿보는 개념을 공유한 '넥스트'에 출연했습니다.[78]

2007년 11월, 케이지는 뉴욕에서 열린 링 오브 아너(Ring of Honor) 레슬링 쇼에서 레슬러의 주연을 찾기 위해 무대 뒤에서 발견되었습니다. 하지만 케이지는 역할을 준비할 시간이 부족하다고 느껴 제작에서 잠시 하차했고 대런 아로노프스키 감독은 미키 루크를 주연으로 선호했습니다. Rourke는 계속해서 그의 연기로 아카데미상 후보에 오를 것입니다.[79][80] /필름과의 인터뷰에서 아로노프스키는 영화를 떠나기로 한 케이지의 결정에 대해 "닉은 완전한 신사였고, 그는 내 마음이 미키와 함께 있다는 것을 이해했고 그는 옆으로 물러났습니다. 저는 배우로서 닉 케이지에 대한 존경심을 가지고 있고, 닉과 함께 할 수도 있었을 것이라고 생각합니다만... 알다시피, 닉은 미키를 믿을 수 없을 정도로 지지했고 미키와 오랜 친구이고 이 기회를 정말 돕고 싶어서 그는 경주에서 빠져 나왔습니다."[81]

2008년, 케이지는 방콕에서 직장 나들이를 하던 중 변심을 겪는 계약 킬러 조 역으로 출연했습니다. 이 영화는 팡 브라더스가 촬영한 것으로 동남아시아의 풍미가 뚜렷합니다.[82] 2009년, 케이지는 알렉스 프로야스가 감독한 공상과학 스릴러 영화 '노우닝'에 출연했습니다. 이 영화에서 그는 아들의 초등학교에서 발굴된 타임캡슐의 내용물을 조사하는 MIT 교수 역을 맡았습니다. 이미 실현된 캡슐 안에서 발견된 놀라운 예측은 그가 이번 주 말에 세상이 끝날 것이며 자신과 아들이 어떻게든 파괴에 연루되어 있다고 믿게 합니다.[83] 이 영화는 엇갈린 평가를 받았지만 개봉 주말 박스오피스 1위를 차지했습니다.[84]

또한 2009년, 케이지는 호평을 받은 독일 감독 베르너 허조그가 감독한 영화 '나쁜 중위: 뉴올리언스의 항구'에 출연했습니다.[85] 그는 도박, 마약, 알코올 중독으로 부패한 경찰관을 연기했습니다. 이 영화는 평론가들에게 매우 좋은 평가를 받았는데, 리뷰 애그리게이터 웹사이트 로튼 토마토에서 87%의 긍정적인 평가를 받았습니다.[86] 시카고 트리뷴의 마이클 필립스(Michael Phillips)는 "헤르조그는 자신의 이상적인 통역사를 찾았습니다. 그의 진실이 공연의 책략에 깊이 있는 공연자입니다. 신사 숙녀 여러분, 니콜라스 케이지(Nicolas Cage)는 자신의 최고의 기량을 갖추고 있습니다."[87]라고 쓰면서 케이지는 그의 연기로 찬사를 받았습니다. 이 영화는 고스트 라이더에서 그의 애정 상대 역할을 했던 에바 멘데스와 케이지를 재회시켰습니다.[88] 2010년, 케이지는 그가 마법사를 연기한 마법사의 견습생에 출연했고, 그 다음 해에는 흑사병을 일으킨 혐의로 기소된 한 여성을 수도원으로 이송하는 14세기 기사로서 시대 작품 '마녀의 계절'의 제목을 달았습니다.[89] 2011년, 케이지는 고스트 라이더의 후속작인 고스트 라이더: 복수의 정령에서 자신의 역할을 다시 맡았습니다.[90]

2012-2017: 다작 및 비디오 직접 촬영 영화

2013년에 케이지는 많은 프로젝트에 참여했습니다. 그가 그루그 크루드라는 이름의 캐릭터의 목소리 연기를 했던 애니메이션 영화 더 크루드를 포함한 주목할 만한 영화들. The Croods는 비평가들로부터 긍정적인 평가를 받았고, 1억 3천 5백만 달러의 예산에 비해 5억 8천 5백만 달러의 수익을 올린 흥행작이었습니다.[91] 그는 알래스카 연쇄 살인범 로버트 한센의 실제 범죄를 바탕으로 스콧 워커가 감독하고 각본을 쓴 스릴러 범죄 드라마 영화 겨울왕국에서 주인공으로 출연했습니다.[92] 그를 쿠삭과 재회시킨 이 영화는 케이지가 연기한 알래스카 주 경찰관이 한센인의 손아귀에서 탈출한 젊은 여성과 파트너가 되어 한센인을 체포하려는 모습을 묘사하고 있습니다. 이 영화는 케이지의 연기가 하이라이트이자 견고한 것으로 꼽혔지만 엇갈린 평가를 받았습니다.[93][94] 그는 또한 1991년 래리 브라운의 동명 소설을 각색한 데이비드 고든 그린이 감독하고 공동 제작한 독립 범죄 드라마 영화인 조에 출연했습니다. 이 영화에서 니콜라스 케이지(Nicolas Cage)는 15세 소년(Tye Sheridan 분)을 고용하고 학대하는 아버지로부터 그를 보호하는 괴로운 남자입니다. 이 영화는 2013년 8월 30일 제70회 베니스 국제 영화제에서 초연되었으며,[95][96] 2013년 토론토 국제 영화제에서 상영되었습니다.[97] 이 영화는 400만 달러의 예산으로 236만 달러의 수익을 올린 흥행 실패작이었지만, 케이지의 연기와 그린의 연출을 칭찬한 비평가들로부터 비평가들의 극찬을 받았습니다.

폴 슈레이더와 함께 한 케이지의 두 번째 영화인 2016년 블랙코미디 도그 이트 도그는 아기를 납치하기 위해 고용된 한 쌍의 전과자로서 윌렘 다포와 재회했습니다.[98] 이 영화는 2016년 5월 20일 칸 영화제에서 감독의 2주간 섹션의 폐막작으로 초연되었습니다.[99] 미국에서는 2016년 11월 4일에 출시되었습니다.[100] 가디언지의 피터 브래드쇼는 이 영화에 별 다섯 개 중 네 개를 주었고, "이 영화는 올바른 프로젝트에 적합한 감독이고 그 결과는 수년간 슈레이더의 최고의 작품입니다: 블랙코믹 혼돈 위에 세워진 낙농적이고, 고약하고, 맛없는 범죄 스릴러입니다."[101]라고 썼습니다. 할리우드 리포터의 토드 맥카시(Todd McCarthy)는 "클리블랜드에서 촬영된 희귀한 영화인 개밥견(Dog Eat Dog)은 확실히 저렴한 가격에 촬영된 것처럼 보이지만 활기와 재치로 화면에 필요한 것을 표시합니다."[102]라고 썼습니다.

케이지는 2017 토론토 국제 영화제 미드나잇 매드니스 섹션에서 초연된 브라이언 테일러의 공포 코미디 영화인 엄마와 아빠에서 셀마 블레어, 앤 윈터스와 함께 주연을 맡았습니다.[103] 2018년 1월 19일 극장에서 [104][105]개봉하여 비평가들로부터 긍정적인 평가를 받았으며, 리뷰 애그리게이터 로튼 토마토(Rotten Tomatoes)는 그의 연기를 "오버 투 더 톱(Over-the-top)"이라고 정의했습니다.[106] 존 워터스 감독은 2018년 최고의 영화 중 하나로 '엄마와 아빠'를 선정하며 개인 최고 순위 4위를 차지하며 이 영화를 높이 평가했습니다.[107]

2018년, 케이지는 2018 선댄스 영화제에서 1월 19일에 개봉한 액션 스릴러 영화 맨디에 출연했습니다.[108][109] RogerEbert.com 의 닉 앨런(Nick Allen)은 "케이지가 좋은 영화, 나쁜 영화, 잊을 수 없는 영화에서 보여준 끝없는 맹렬한 연기에 대해, 이상한 세계와 캐릭터에 대한 80년대의 열광적인 열정은 케이지의 위대함을 십분 활용하고, 일부는 그 후에"라고 말하며 영화를 칭찬했습니다. 10월, 맨디의 제작자 엘리야 우드는 니콜라스 케이지와 작곡가 요한 요한슨(그 해 2월 사망)[111]을 위한 오스카 캠페인 규모를 늘릴 계획이라고 발표했지만, 이 영화는 9월 14일 비디오 온 디맨드에서도 공개되었기 때문에 실격되었습니다.[112][113][114][115]

그 해 말, 케이지는 애니메이션 영화 틴 타이탄즈 고에서 클라크 켄트 / 슈퍼맨 목소리 연기를 했습니다! 영화로. 그는 원래 1990년대 팀 버튼 감독의 취소된 슈퍼맨 영화 슈퍼맨 라이브스에서 슈퍼맨을 연기할 예정이었습니다.[116] 그는 단색의 1930년대 우주 버전인 피터 파커 / 스파이더맨 느와르 (2018)의 목소리를 냈습니다. 케이지는 험프리 보가트, 제임스 캐그니, 에드워드 G. 로빈슨의 영화를 기반으로 그의 보컬 공연을 했습니다.[117]

2019년 1월 28일, 빅토르와 이리나 옐친은 2019 선댄스 영화제에서 그들의 아들 안톤 옐친, 러브, 안토샤에 관한 다큐멘터리를 개봉했습니다.[118] 이 다큐멘터리는 개릿 프라이스(Garret Price)가 감독했으며, 안톤의 친구들과 크리스틴 스튜어트(Kristen Stewart), J.J. 에이브럼스(J. Abrams), 크리스 파인(Chris Pine), 제니퍼 로렌스(Jennifer Lawrence), 조디 포스터(Jodie Foster), 존 조(John Cho), 마틴 랜도(Martin Landau)와 같은 협력자들과의 다양한 인터뷰를 담고 있습니다. 케이지는 안톤의 다양한 글을 읽으며 영화의 내레이터로 출연했습니다.[119]

2018년 12월, 케이지는 H.P. 러브크래프트의 단편 소설 "The Color Out of Space"를 바탕으로 리처드 스탠리의 "Color Out of Space"의 주연을 맡기로 계약했다고 발표했습니다.[120][121] 이것은 그가 The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996)에서 해고된 이후 감독된 스탠리의 첫 장편 영화였습니다.[122] 2019년 9월 7일, 2019 토론토 국제 영화제 미드나잇 매드니스(Midnight Madness)에서 첫 상영을 했고, 케이지는 크리에이티브 얼라이언스(Creative Coalition)의 스포트라이트 이니셔티브 상(Spotlight Initiative Award)을 수상했습니다.[123][124] 이 영화는 1월 22일 선별 시사회 상영에 이어 2020년 1월 24일 미국 81개 극장에서 개봉되었습니다.[125]

2018년 12월, Sion Sono가 Nicolas Cage 주연의 첫 번째 해외 제작 및 영어 데뷔작인 "유령의 포로들"을 작업 중이라고 발표했습니다. 케이지는 이 영화가 "내가 만든 영화 중에 가장 엉뚱한 영화일 수도 있다"[126]고 말했습니다. 그것의 줄거리는 유령의 나라라는 어두운 지역으로 사라진 주지사의 입양된 손녀를 구하기 위해 보내진 악명 높은 범죄자 히어로(케이지 분)를 중심으로 전개됩니다.[127] 이 영화는 2021년 1월 31일 2021 선댄스 영화제에서 세계 초연되었습니다.[128]

2018-현재 : 커리어 르네상스

이 섹션을 업데이트해야 합니다. (2023년 12월) |

2020년 5월, 케이지는 댄 라가나가 각본을 쓰고 제작한 8부작 타이거 킹 시리즈에서 조 이국적인 역을 연기할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[129] 2021년 7월에 프로젝트가 폐기되었음을 발표했습니다.[130]

2013년 4월, 드림웍스 애니메이션은 영화 The Croods의 속편을 발표했습니다.[131] 2013년 9월, 니콜라스 케이지가 첫 번째 영화에서 후속작 그루그 역으로 다시 출연할 것으로 확인되었습니다.[132] 2020년 11월 25일 미국에서 조엘 크로포드가 연출한 더 크루드: 어 뉴 에이지(The Croods: A New Age)가 극장 개봉했습니다.

케이지는 2021년 영화 돼지에서 제작 및 주연을 맡았는데, 여기서 전직 요리사가 은둔형 트러플 수렵꾼으로 변신한 로빈 "롭" 펠드는 납치된 후 사랑하는 수렵 돼지를 찾아 포틀랜드의 과거로 돌아가야 합니다. 케이지는 그의 연기로 비평가들의 호평을 받았고 비평가 초이스 영화상 남우주연상에 두 번째 후보로 지명되었습니다.[133] 그는 2022년 액션 코미디 영화인 거대한 재능의 참을 수 없는 무게에서 자신의 허구화된 버전을 연기함으로써 더 많은 찬사를 받았습니다.[134]

2021년 11월, 케이지는 유니버설 클래식 몬스터즈 스핀오프 영화인 렌필드에 캐스팅되었습니다. 케이지(Cage)는 니콜라스 홀트(Nicholas Hoult)의 제목 R.M. 렌필드(R.M. Renfield)의 드라큘라(Dracula) 역으로 조연으로 출연합니다. 이 영화는 크리스 맥케이가 감독을 맡았고, 라이언 리들리가 로버트 커크먼의 원작을 대본으로 썼습니다. 맥케이와 커크먼은 또한 스카이바운드 엔터테인먼트와 유니버설 픽처스의 합작 제작으로 데이비드 앨퍼트, 브라이언 퍼스트, 션 퍼스트와 함께 영화를 제작했습니다.[135] 본 촬영은 2022년 초에 시작되었습니다.[136][137]

케이지는 2023년 7월 데드 바이 데이라이트(Dead by Daylight)에서 자신으로 비디오 게임 데뷔를 했습니다. 그의 외모는 2023년 5월 17일 놀림을 받았습니다.[138]

케이지(Cage)는 2023년 영화 플래시(The Flash)에서 클라크 켄트(Clark Kent) / 슈퍼맨(Superman) 역을 맡아 슈퍼히어로의 대체 버전으로 카메오 출연했습니다.[139] 케이지는 볼륨 캡처를 통해 그의 장면을 촬영했고 CGI는 그의 나이를 줄이는 데 사용되었습니다.

제작 및 연출

케이지는 2002년에 James Franco가 그의 포주 역할을 하는 남자 매춘부로 출연하는 저예산 드라마인 Sonny로 감독 데뷔를 했습니다. 케이지는 이 영화에서 작은 역할을 맡았는데, 이 영화는 저조한 평가와 제한된 수의 극장에서 짧은 상영을 받았습니다.[21][140] 케이지의 제작 경력에는 새턴 필름의 첫 번째 노력인 뱀파이어의 그림자가 포함되어 있습니다.[141]

2006년 12월 초 바하마 국제 영화제에서 케이지는 다른 관심사를 추구하기 위해 앞으로 연기 활동을 축소할 계획이라고 발표했습니다. The Dresden Files for the Sci-Fi Channel에서 케이지는 총괄 프로듀서로 등재되어 있습니다.[142]

기타작업

열렬한 만화책 팬인 케이지(Cage)는 2002년 헤리티지 옥션을 통해 400권의 빈티지 만화 컬렉션을 160만 달러가 넘는 가격에 경매에 부쳤습니다.[143] 2007년, 그는 그의 아들 Weston과 함께 Virgin Comics에 의해 출판된 Voodoo Child라는 만화책을 만들었습니다.[144] 케이지(Cage)는 화가이자 언더그라운드 만화가인 로버트 윌리엄스(Robert Williams)의 팬이자 수집가입니다. 그는 Juxtapoz 잡지에 소개 글을 썼고 Death on the Boards라는 그림을 구입했습니다.[145]

리셉션과 연기 스타일

"케이지의 손에는 만화 같은 순간들이 진짜 감정으로 가득 차 있고 진짜 감정은 만화가 됩니다. 개별 장면부터 대사 한 줄에 이르기까지 모든 것이 창작의 기회로 받아들여진 것처럼 느껴집니다. 케이지는 그의 영화들이 그렇지 않을 때도 보통 흥미롭습니다. 그는 변덕스럽고 예측할 수 없습니다. 그는 매혹적이고 변덕스럽습니다. 그는 연주자입니다. 그는 말썽꾸러기입니다. 그는 재즈 음악가입니다."

—Luke Buckmaster, The Guardian[146]

2011년 2월, 케이지는 자신의 경력의 어느 시점에서 자신만의 연기 방식을 개발했다는 것을 깨달았고, 이를 "누보 샤머니치"라고 표현했습니다. 그는 그것에 대해 "언젠가는 책을 써야 할 것"이라고 언급했습니다.[147] 케이지는 나중에 브라이언 베이츠가 쓴 책 '배우의 길'에서 영감을 얻었다고 설명했는데, 그 책에서 그는 고대의 무속인들과 스페인인들 사이의 유사점에 대해 읽었습니다.[148] 다른 인터뷰에서 케이지는 독일 표현주의나[149] 서구 가부키 같은 용어를 사용하여 자신의 연기 스타일을 정의했습니다.[150]

때때로 케이지는 극단적인 방법으로 연기를 하기 위해 일어섰습니다. Birdy를 위해, 그의 캐릭터(베트남 전쟁의 참전 용사)의 고통을 육체적으로 느끼기 위해, 케이지는 마취 없이 어차피 뽑아야 했을 치아 두 개를 제거했습니다.[151] 그는 또한 붕대로 얼굴을 감싼 채 5주를 보내며 다양한 사람들의 살벌한 반응을 얻었습니다. 그가 붕대를 벗었을 때, 그의 피부는 여드름과 자라나는 털 때문에 감염되었습니다.[152]

뱀파이어 키스의 캐스팅 디렉터인 Marcia Shulman은 케이지가 제니퍼 빌스와의 러브신 동안 흥분하기 위해 뜨거운 요거트를 발가락 위에 부어 달라고 요청했다고 선언했습니다.[153] 그는 또한 액션 영화에서의 역할을 위해 UFC 챔피언 로이스 그레이시 밑에서 브라질 주짓수를 공부했습니다.[154] 2012년 조를 홍보하는 인터뷰에서 케이지는 그 역할을 위해 살을 찌우고 자신을 육식동물이라고 밝히기 위해 붉은 고기와 스테이크를 기본으로 하는 식단을 따랐다고 밝혔습니다.[155]

가디언지의 영화 평론가 루크 벅마스터에 따르면, "아무나 무심한 관찰자는 케이지가 재미있고, 카리스마 있고, 미친 듯이 현란하다는 것을 알 수 있습니다." 벅마스터는 이를 케이지 가족의 "잘 교양된" 배경 탓으로 돌리며, 이 배우가 "괴기스러운 캐릭터에 분명히 끌리며, 그들에 대한 거칠고 거침없는 접근으로 찬사를 받고 있다"고 말했습니다. 그는 주인공의 존재감과 캐릭터 배우의 기괴함을 가지고 있습니다." 배우 에단 호크는 2013년 케이지가 "말론 브란도 이후로 실제로 그 예술로 새로운 것을 한 유일한 배우"라고 말하며, 영화 관객들을 "내가 생각하기에 옛날 음유시인들에게 인기 있는 일종의 연기 스타일로" 데려간 것에 대해 공을 세웠습니다.[156]

영화감독 데이비드 린치는 그를 "미국 연기의 재즈 뮤지션"이라고 묘사했습니다.[146] 많은 비평가들은 케이지가 과잉행동을 했다고 비난했습니다.[146] 케이지 자신을 포함한 다른 사람들은 그의 의도적으로 극단적인 연기를 "메가 액팅"이라고 묘사했습니다.[157][158] 1990년대 후반, 배우의 주류 스릴러 영화 시리즈가 끝난 후, 숀 펜은 1999년 뉴욕 타임즈에 케이지가 "더 이상 배우가 아니라 공연자에 가깝다"고 말했습니다.[159] 그럼에도 불구하고, 펜은 미스틱 리버에서의 연기로 오스카 상을 수상한 후 연설에서 (성냥개비 남자에서) 케이지의 작품을 2003년 최고의 공연 중 하나로 묘사했습니다.[160]

2010년대 동안, 점점 더 많은 영화 평론가들이 케이지를 그의 세대에서 가장 과소평가된 배우 중 한 명으로 묘사했습니다.[161][162][163]

2021년 7월, 케이지는 버라이어티에게 자신의 공연에 부과된 상업적 제약 때문에 할리우드를 버리고 저예산 독립 영화에서 일하는 것을 선택했다고 말했습니다.[164][9]

개인생활

관계와 가족

1988년, 그녀는 배우 크리스티나 풀턴과 교제를 시작했고, 그 사이에 아들 웨스턴 코폴라 케이지(Weston Coppola Cage, 1990년 12월 26일 ~ )가 있습니다. 웨스턴은 두 개의 검은 금속 밴드에 참여했고, 그의 아버지의 영화 "로드 오브 워"에 헬리콥터 정비공으로 출연했습니다. 웨스턴을 통해 케이지는 2014년과 2016년에 태어난 두 명의 손자를 두고 있습니다.[165]

케이지는 다섯 번 결혼했습니다. 그의 첫 번째 부인은 배우 패트리샤 아퀘트로 1995년 4월에 결혼하여 2001년에 이혼했습니다.[166]

케이지의 두 번째 결혼은 엘비스와 프리실라 프레슬리의 딸인 싱어송라이터 리사 마리 프레슬리와의 결혼이었습니다. (엘비스 팬인 케이지는 '와일드 앳 하트'에서 엘비스를 공연하는데 영감을 주었습니다.) 두 사람은 2002년 8월 10일 하와이 카뮤엘라에서 결혼식을 올리고 107일 뒤인 2002년 11월 25일 이혼 소송을 냈습니다. 2004년 5월 24일 이혼이 확정되었습니다.[167]

케이지의 세 번째 아내는 앨리스 김이었습니다. 그들은 2004년 7월 30일 북부 캘리포니아의 한 개인 목장에서 결혼식을 올렸습니다.[168] 그녀는 2005년 10월 3일 (슈퍼맨의 태명을 따서) 아들 칼엘을 낳았습니다.[169] 그들은 2016년 1월에 이혼했습니다.[170]

2019년 3월 미국 라스베이거스에서 코이케 에리카와 결혼식을 올렸지만 4일 만에 결혼식을 올렸다.[171] 그는 3개월 후에 코이케와 이혼을 허락받았습니다.[172]

2021년 2월 16일,[173] 시바타 리코와 결혼. 그들의 딸 아우구스트 프란체스카는 2022년 9월 7일에 태어났습니다.[174]

정치적 견해와 종교적 신념

케이지는 가톨릭 집안에서 자랐지만 공개적으로 종교에 대해 이야기하지 않으며 인터뷰에서 종교와 관련된 질문에 대답하는 것을 거부합니다.[11] '아는 것'에 대한 그의 캐릭터의 종교적 믿음 부족과 연관될 수 있는지에 대한 질문에 케이지는 "알다시피, 제 개인적인 믿음이나 의견 중 어떤 것도 영화와의 관계에 영향을 미칠 위험을 무릅쓴 것입니다. 영화는 수수께끼로 남겨두는 것이 가장 좋다고 생각합니다. 답변보다 더 많은 질문을 남겼습니다. 저는 절대 설교하고 싶지 않습니다. 그래서 그것이 영화에서 얻는 것입니다. 그것은 제가 제공할 수 있는 것보다 훨씬 더 흥미롭습니다."[175]

샌타크루즈 캘리포니아대를 방문한 그는 "중국 신드롬이라는 영화에서 원자력에 대해 더 많이 배웠다"며 자신은 정치적으로 활동적인 배우가 아니며 작품에서 할 수 있다고 말했습니다.[176] 케이지는 2020년 대선에서 앤드류 양을 지지했습니다.[177]

그의 삶의 어느 순간, 케이지는 자신의 본성의 철학적인 측면을 발전시키고 싶다고 결심했고, 성배를 찾기 위한 탐험을 떠났습니다. 케이지는 그것을 찾기 위해 영국으로 여행을 갔지만, 또한 미국의 몇몇 지역도 보았습니다.[178][179]

자선활동

케이지는 할리우드에서 가장 관대한 스타 중 한 명으로 불렸습니다.[180] 그는 국제앰네스티에 그들이 전세계 분쟁에서 싸우도록 강요된 30만명의 어린이들에게 재활 보호소, 의료 서비스, 심리 및 재통합 서비스를 제공하는 데 사용할 수 있도록 2백만 달러를 기부했습니다.[181] 그는 또한 허리케인 카트리나의 희생자들을 위해 백만 달러를 기부했습니다.[182] 그는 노예제로부터의 자유와 아동 노동으로부터의 자유를 포함하여, 직장에서의 기본적인 권리에 대한 인식을 높이기 위한 예술가 참여 프로그램인 아트웍스를 지원한 최초의 예술가가 되었습니다.[183] 2023년 웨스턴 오스트레일리아에서 서퍼를 촬영하는 동안 케이지는 채널 세븐 퍼스 텔레톤에 5,000 호주 달러를 기부하는 전화를 직접 걸었습니다.[184]

케이지는 또한 그의 업적으로 유엔으로부터 인도주의 상을 수상하였으며, 2009년과 2013년에 다시 유엔 글로벌 저스티스 대사로 임명되었습니다.[185] 그는 국제 무기 통제에 대한 인식을 높이기 위해 영화 '로드 오브 워'를 중심으로 캠페인을 이끌었고, '힐 더 베이', '유엔 니그로 대학 기금', '로열 유나이티드 병원'의 '영원한 친구들 호소' 등을 지지하며 아기들을 위한 중환자실을 짓도록 했습니다.[186][187]

부동산과 세금문제

니콜라스 케이지(Nicolas Cage)는 2014년 포브스지의 톱 10 리스트에 오르지는 못했지만, 2009년 포브스지에 따르면 4천만 달러를 벌어들이며 할리우드에서 가장 돈을 많이 버는 배우 중 한 명으로 여겨졌습니다.[188][189] 케이지는 김씨와 함께 살던 말리부 집을 갖고 있었지만 2005년 1000만 달러에 이 땅을 팔았습니다. 2004년에 그는 바하마 파라다이스 섬에 부동산을 구입했습니다. 2006년 5월, 그는 나소에서 남동쪽으로 약 85마일(137km) 떨어져 있고 Faith Hill과 Tim McGraw가 소유한 비슷한 섬에 가까운 Exuma 군도에 있는 40에이커(16ha)의 섬을 구입했습니다.[190] 그는 2006년 독일 오버팔츠 지역에 있는 중세 성 슐로스 네이드슈타인을 사들여 2009년 250만 달러에 팔았습니다. 그의 할머니는 독일인으로 코체만 데르 모젤에 살았습니다.[191]

2007년 8월, 케이지는 로드 아일랜드 미들타운에 있는 24,000평방피트(2,200m2)의 벽돌과 돌로 만든 시골 저택인 "그레이 크레이그"를 구입했습니다. 26에이커(11ha)의 부동산을 차지하고 있는 이 집에는 12개의 침실과 10개의 욕실이 있으며 대서양을 내려다 볼 수 있습니다. 서쪽으로는 노르만 조류 보호구역과 접해 있습니다. 이 매물은 로드 아일랜드 주에서 가장 비싼 주택 구입 가격에 속했습니다.[192][193] 또한 2007년에 케이지는 영국 서머셋에 있는 미드포드 성을 구입했습니다.[194][195] 독일 성을 판 직후, 케이지는 바하마에 있는 700만 달러짜리 섬뿐만 아니라 로드 아일랜드, 루이지애나, 네바다, 캘리포니아에 있는 자신의 집도 시장에 내놓았습니다.[196]

2009년 7월 14일, 국세청은 Louisiana의 Cage 소유 부동산에 대한 연방세 유치권과 관련하여 미납된 연방세와 관련된 서류를 뉴올리언스에 제출했습니다. 국세청은 케이지가 2007년 연방소득세로 620만 달러 이상을 체납했다고 주장했습니다.[197] 게다가 국세청은 2002년부터 2004년까지 350,000달러 이상의 미납 세금에 대한 또 다른 유치권을 가지고 있었습니다.[198] 케이지는 2009년 10월 16일, 자신의 사업 담당자인 Samuel J. Levin을 상대로 과실과 사기 혐의로 2천만 달러의 소송을 제기했습니다.[199] 소송은 레빈이 "세금을 납부해야 할 때 지불하지 않았고, [케이지]를 투기적이고 위험한 부동산 투자에 놓았고, 그로 인해 (배우가) 재앙적인 손실을 입었습니다"라고 진술했습니다.'"케이지는[199] 또한 East West Bank와[200] Red Curve Investments로부터 수백만 달러의 미지급 대출에 대한 별도의 소송에 직면했습니다.

Samuel Levin은 Cage에게 자신의 능력 밖의 삶을 살고 있다고 경고하고 돈을 적게 쓰라고 촉구하는 내용의 소송에 대해 맞불을 놓았고 소송에 응했습니다. 레빈의 서류에는 "레빈의 말을 듣는 대신, 교차 피고 케이지(코폴라)는 자유 시간의 대부분을 높은 티켓 구매를 위해 쇼핑을 하며 보냈고, 결국 15개의 개인 거주지를 갖게 되었습니다."라고 적혀 있습니다. 레빈의 불평은 계속되었습니다. " 마찬가지로 레빈은 코폴라에게 걸프스트림 제트기를 사는 것에 반대하고, 요트를 사고 소유하는 것에 반대하고, 롤스로이스 비행단을 사고 소유하는 것에 반대하고, 수백만 달러의 보석과 예술품을 사는 것에 반대한다고 조언했습니다."[201]

레빈은 2007년에 "케이지의 쇼핑은 총 3,300만 달러 이상의 비용으로 3개의 거주지를 추가로 구입하는 것을 수반했습니다; 자동차 22대(롤스로이스 9대 포함), 값비싼 보석 12대, 예술품과 이국적인 물품 47대를 구입하는 것입니다"[201]라고 말했습니다. 그 물건들 중 하나는 타르보사우루스의 공룡 두개골이었습니다. 도난당한 사실을 발견하고 몽골 당국에 반환했습니다.[202]

케이지(Cage)에 따르면, 그는 루이지애나(Louisiana) 뉴올리언스(New Orleans)의 프렌치 쿼터(French Quarter)에 위치한 "미국에서 가장 유령이 나오는 집"을 소유하고 있었다고 합니다.[203] 이전 소유주 델핀 라오리의 이름을 따서 "라오리 하우스"로 알려진 이 집은 케이지의 재정 문제로 인해 2009년 11월 12일 경매에서 또 다른 뉴올리언스 부동산과 함께 총 550만 달러에 팔렸습니다.[204] 총 1,800만 달러의 대출을 받은 그의 벨 에어의 집은 2010년 4월 압류 경매에서 1,040만 달러의 공개 제안에도 불구하고 판매에 실패했습니다. 이는 케이지가 원래 판매하려고 했던 3,500만 달러보다 훨씬 적은 금액입니다. 1940년 11만 달러(2022년 230만 달러 상당)에 지어진 이 집은 딘 마틴과 가수 톰 존스가 각기 다른 시기에 소유하고 있었습니다.[205]

이 집은 결국 2010년 11월에 1,050만 달러에 팔렸습니다.[206] 네바다에 있는 또 다른 주택도 압류 경매에 부닥쳤습니다.[204] 2011년 11월, 케이지(Cage)는 헤리티지 옥션(Heritage Auction)이 관리하는 온라인 경매에서 세금 유치권 및 기타 부채를 지불하는 데 도움이 되는 기록적인 216만 달러(이전 기록은 150만 달러)에 액션 코믹스 #1을 판매했습니다. 케이지는 1997년에 이 만화를 11만 달러에 구입했습니다.[207] 그 만화는 2000년에 그에게서 도난 당했고, 케이지는 그 물건에 대한 보험금을 받았습니다. 2011년 3월 샌 페르난도 밸리(San Fernando Valley)에 있는 보관함에서 발견되었으며 ComicConnect.com 에서 이전에 케이지(Cage)에 판매된 복사본임을 확인했습니다. 보도에 따르면 2017년 5월까지 약 2,500만 달러의 가치가 있는 케이지는 남은 빚을 갚기 위해 "좌우의 영화 역할을 맡았다"고 합니다.[209] 2022년까지 케이지는 마침내 빚을 갚았고 영화 역할을 좀 더 선택적으로 하려고 했음을 확인했습니다.[210]

법률문제

캐슬린 터너는 2008년 회고록 '장미를 보내라'에서 케이지가 치와와를 훔쳤고, 페기 수 결혼식을 촬영하는 동안 음주운전으로 두 번이나 체포됐다고 썼습니다.[211] 나중에 그녀는 케이지가 치와와를 훔치지 않았다는 것을 인정했고 그녀는 미안해 했습니다.[212][213] 케이지는 터너와 그녀의 출판사 헤드라인 출판 그룹, 그리고 (데일리 메일이 책에서 발췌한 내용을 출판했을 때 그 주장을 반복했던) AP통신을 상대로 명예훼손 소송에서 이겼습니다.[214]

크리스티나 풀튼은 2009년 12월 케이지를 1,300만 달러와 그녀가 살고 있는 집을 위해 고소했습니다. 그 소송은 그녀가 집을 나가라는 명령에 대한 응답이었습니다; 그 명령은 케이지의 재정적 어려움에서 비롯되었습니다.[215] 이 사건은 2011년 6월에 해결되었습니다.[216]

케이지는 2011년 4월 15일 뉴올리언스의 프렌치 쿼터 지역에서 가정용 배터리 남용 혐의로 체포되어 평화와 대중의 음주를 방해했습니다. 한 경찰관은 케이지가 술에 취한 것처럼 보이다가 아내의 윗팔을 잡았다는 소문이 나자 구경꾼들에 의해 기치가 떨어졌습니다.[217] 케이지는 듀안 "도그" 채프먼에 의해 11,000달러의 보석금이 발부될 때까지 경찰에 구금되었습니다.[218] 그는 이후 2011년 5월 31일 법정에 출두하라는 명령을 받았습니다.[219] 뉴올리언스 지방 검사는 케이지에 대한 기소가 2011년 5월 5일에 취하되었다고 발표했습니다.[220][221]

연기 크레딧 및 포상

영화 산업에 기여한 공로로 케이지는 1998년 할리우드 대로 7021에 위치한 영화배우와 함께 할리우드 명예의 거리에 헌액되었습니다.[222][223] 2001년 5월, 케이지는 풀러턴 캘리포니아 주립 대학으로부터 미술 분야 명예 박사 학위를 수여 받았습니다. 그는 졸업식에서 연설했습니다.[224] 케이지는 또한 아카데미상 후보에 두 번 올랐습니다. 그는 1995년 영화 '라스베가스를 떠나다'에서의 역할로 아카데미 남우주연상을 수상했습니다. 그는 2002년 영화 '어댑션'에서의 역할로 두 번째 후보에 올랐습니다.[225]

그는 또한 골든 글로브상, 스크린 배우 조합상, 그리고 '라스베가스를 떠나다'로 더 많은 상을 받았습니다. 그는 그의 영화 '적응', '베가스의 신혼여행', '문스트룩'으로 골든 글로브, 영화배우조합, 영화배우조합(BAFTA)에 의해 지명되었습니다.[226] 그는 또한 많은 다른 상을 수상하고 후보에 올랐습니다.

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ "UPI Almanac for Monday, Jan, 7, 2019". United Press International. January 7, 2019. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

actor Nicolas Cage in 1964 (age 55)

- ^ Naden, Corinne J.; Blue, Rose (2003). Nicolas Cage. Lucent Books. ISBN 978-1590181362.

nicolas kim coppola.

- ^ "To celebrate an unforgettable career, here are the 10 essential Nicolas Cage movies The Spokesman-Review". www.spokesman.com.

- ^ Correspondents, B. N. N. (November 10, 2023). "Nicolas Cage: A Versatile Career and the Complexities of Fame".

- ^ Rose, Steve (October 2, 2018). "Put the bunny back in the box: is Nicolas Cage the best actor since Marlon Brando?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ Tafoya, Scout (May 25, 2021). "The Whole Parade: On the Incomparable Career of Nicolas Cage". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ Nguyen, Terry (August 7, 2019). "The enduring strangeness of Nicolas Cage". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "A Tribute to Nicolas Cage: The Rise, Journey & Latest 'Adaptation' of Our 'Kick-Ass' 'National Treasure'". Hollywood Insider. January 10, 2021. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Hibberd, James (December 4, 2023). "Nicolas Cage Says He's Almost Finished: "Three or Four More Movies Left"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ Ellwood, Mark (March 15, 2009). "Nicolas Cage is back with digit-al thriller 'Knowing'". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Fennell, Hilary (May 21, 2011). "This much I know: Karen Koster". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Anhalt, Karen Nickel (April 1, 2009). "Nicolas Cage Sells His Castle". People. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Cowie, Peter (August 22, 1994). Coppola: a biography. Da Capo Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0306805981.

- ^ Markovitz, Adam (December 14, 2007). "Coppola Family Flow". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Francis Ford Coppola's Hollywood family tree". CNN. July 15, 2009. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Hal Erickson (2014). "Nicolas Cage Full Biography". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage – Details". cinema.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Selby, Jenn (March 11, 2014). "Nicolas Cage on the rise of the celebutard". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ Hill, Logan (November 16, 2009). "The Wild, Wild Ways of Nicolas Cage" (PDF). New York. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Pall, Ellen (July 24, 1994). "Nicholas Cage, The Sunshine Man". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Nicolas Cage Biography". biography.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Coffel, Chris (December 16, 2016). "The Tao of Nicolas Cage: The Best of Times". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Lauren Schutte (February 14, 2012). "Nicolas Cage on Turning Down 'Dumb & Dumber,' Winning Another Oscar and the Movie that Made Him Change His Name". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Spencer, Ashley (May 11, 2020). "When 'Valley Girl' (and Nicolas Cage) Shook Up Hollywood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 15, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Sollosi, Mary (May 8, 2020). "Valley Girl is, like, a totally ironic nostalgia trip: Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Mell, Elia (August 30, 2013). Casting Might-Have-Beens. McFarland and Company. ISBN 978-1476609768. Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Leigh, Danny (January 2, 2009). "The view: The lost pleasures of Rumble Fish". The Guardian. Manchester. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1983). "Racing with the Moon". Variety. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Attanasio, Paul (December 14, 1984). "'Cotton Club': Coppola's Triumph". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (August 20, 2021). "The method and madness of Nicolas Cage". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 21, 1984). "The Screen: Alan Parker's 'Birdy'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Tafoya, Scout (May 25, 2021). "The Whole Parade: On the Incomparable Career of Nicolas Cage". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Billson, Anne (July 3, 2013). "The wonderfully mad world of Nicolas Cage". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Westbrook, Caroline (January 1, 2000). "Raising Arizona Review". Empire. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Nicolas Cage". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 22, 2003). "Moonstruck". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ James, Caryn (June 2, 1989). "Review/Film; The Woman He Adores, It Turns Out, Is a Vampire". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Whipp, Glenn (January 26, 2022). "Nicolas Cage meditates on movies, music and what makes him happy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Wild at Heart". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ "Industrial Symphony No. 1". Chicago Reader. April 25, 2017. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (May 25, 1990). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Fire Birds' Aiming to Be 'Top Gun' With Helicopters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (August 5, 2019). "Nicolas Cagetastic Case File #143: Zandalee". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ McBride, Joseph (August 20, 1992). "Honeymoon in Vegas". Variety. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 28, 1992). "Honeymoon in Vegas". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Baylis, Sheila Cosgrove (February 17, 2015). "Fans Petition for Nicolas Cage to Host Saturday Night Live". People. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Red Rock West". Rotten Tomatoes. June 16, 1993. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Howe, Desson (March 11, 1994). "'Guarding Tess'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Mark, Lois Alter (July 29, 1994). "Based on a True Story". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Hicks, Chris (December 6, 1994). "Film review: Trapped in Paradise". Deseret News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (October 12, 2020). "My World of Flops Christmas Catastrophe Case File #169/The Travolta/Cage Project #42 Trapped in Paradise (1994)". NathanRabin.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (April 21, 2022). "'Kiss of Death' (R)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage wins best actor Oscar". United Press International. March 26, 1996. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ "Cage Did Serious Research For Alcoholic Role". World Entertainment News Network. August 9, 2000. Archived from the original on July 5, 2004. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ^ Larman, Alexander (June 2, 2021). "First Alcatraz, then Iraq: how The Rock became Michael Bay's weapon of mass destruction". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Larman, Alexander (June 15, 2022). "'Nothing was too insane': is Con Air the strangest action film ever made?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 6, 1997). "Con Air". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Glanville, Martyn (December 10, 2000). "Face/Off (1997)". BBC. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel (April 6, 1998). "City of Angels". Variety. Archived from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (April 10, 1998). "Film Review; Heaven, He's From Heaven, But His Heart Beats So . . ". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (August 5, 1998). "Snake Eyes". Variety. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "Snake Eyes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 12, 2003). "Matchstick Men". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "The Rock". Rolling Stone. June 7, 1996. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage: 'Ghost Rider' star's top 10 insane movie roles". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage: 'Ghost Rider' star's top 10 insane movie roles". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Gone in 60 Seconds". The Guardian. August 3, 2000. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ "Captain Corelli's Mandolin : Interview With Nicolas Cage". cinema.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Captain Corelli's Mandolin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Adaptation". CBS Sunday Morning. April 6, 2014. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Cage Uncaged: A Nicolas Cage Retrospective". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Mercer, Benjamin (March 4, 2011). "'The Weather Man': Nicolas Cage's Last Good Movie". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Heritage, Stuart (February 26, 2007). "Ghost Rider Wigs Out Weekend Box Office For Second Week". Heckler Spray. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Clarke, Donald. "50 years, 50 films: The Wicker Man (1973)". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Monson, Leigh (September 1, 2016). "'The Wicker Man' remake is just as ridiculous even 10 years later". Substream Magazine. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "Ghost Rider". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Miska, Brad (May 15, 2014). "Nicolas Cage to 'Pay the Ghost' During Halloween Parade". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (April 27, 2007). "Glimpsing the Future (and a Babe)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Family man". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Bruno, Mike (November 12, 2007). "Mickey Rourke Starring in 'The Wrestler'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage: I Wasn't 'Dropped' From 'The Wrestler'". Access Hollywood. March 10, 2009. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter. "Interview: Darren Aronofsky – Part 1". /Film. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (September 4, 2008). "Bangkok Dangerous". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 18, 2009). "Knowing". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Travers, Peter (March 23, 2009). ""Knowing" and Other Nicolas Cage Box-Office Winners That Don't Deserve to Be Hits". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans". cinemablend.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "'Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans' – 3 1/2 stars". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "Talking Pictures: 'Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans' – 3 1/2 stars". Chicago Tribune. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "Ghost Rider Movie Blog: Casting Eva Mendes". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "MTV". MTV. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ "'Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance' Review". Screen Rant. February 17, 2012. Archived from the original on March 6, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "The Croods". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Dima Alzayat (October 20, 2011). "On Location: 'The Frozen Ground' heats up filming in Alaska". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "The Frozen Ground". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. August 23, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "The Frozen Ground". Metacritic. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ "Venezia 70". labiennale. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ "Venice film festival 2013: the full line-up". The Guardian. London. July 25, 2013. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ "Toronto film festival 2013: the full line-up". The Guardian. London. July 23, 2013. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (May 20, 2016). "Cannes Film Review: 'Dog Eat Dog'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (May 14, 2016). "Willem Dafoe's Loose Cannon Crook in Paul Schrader's 'Dog Eat Dog' – Cannes Video". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 16, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Erbland, Kate (September 26, 2016). "'Dog Eat Dog' Trailer: Nicolas Cage and Willem Dafoe Go Wild In Paul Schrader's Crazy Heist Thriller—Watch". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 16, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (May 20, 2016). "Dog Eat Dog review – Willem Dafoe is magnificently needy in Paul Schrader's tasty thriller". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (May 20, 2016). "'Dog Eat Dog': Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (February 12, 2016). "Berlin: Nicolas Cage Boards Horror Thriller 'Mom and Dad'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Miska, Brad (November 9, 2017). "'Mom and Dad' Turns Nicolas Cage and Selma Blair into Maniacs". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ Wilner, Norman (August 1, 2017). "TIFF 2017's Midnight Madness, documentary slates are announced". Now. NOW Communications. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ "Mom and Dad (2018)". Rotten Tomatoes. January 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Nordine, Michael (December 1, 2018). "John Waters' Favorite Movies of 2018 Are as Eclectic and Offbeat as He Is". IndieWire. Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Lodderhose, Diana (June 7, 2017). "Nicolas Cage To Star in Action Thriller 'Mandy' From SpectreVision, XYZ Films & Umedia". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Collis, Clark (January 16, 2018). "Nicolas Cage is seeking vengeance on exclusive poster for Sundance film Mandy". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Allen, Nick (January 20, 2018). "Sundance 2018: Mandy". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (February 10, 2018). "How Composer Jóhann Jóhannsson Helped Change the Genre Cinema Soundscape". Variety. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "Mandy (2018) – Daily Box Office Results – Box Office Mojo". boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Pearson, Ben (August 17, 2018). "'Mandy' Advance Screenings Coming to 226 Theaters, Featuring Conversation with Nicolas Cage and Director Panos Cosmatos". /Film. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (October 1, 2018). "'Mandy' Producer Elijah Wood: Nicolas Cage Back In Oscar-Level Form With Revenge Film's Surprise Success". Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ O'Brien, Becky (January 16, 2019). "'Mandy' is Disqualified From the Oscars". cinelinx.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (March 12, 2018). "Exclusive: Nicolas Cage plays Superman, Halsey is Wonder Woman in 'Teen Titans GO!'". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (July 5, 2018). "'Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse': Nicolas Cage Confirmed to Play Another Spider-Man". Collider. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ Kaufman, Amy (January 24, 2019). "Still grieving, Anton Yelchin's parents try to move forward with new documentary". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Barker, Andrew (January 30, 2019). "Sundance Film Review: 'Love, Antosha'". Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ "Richard Stanley is back in the saddle again, will direct 'Color out of space,' starring Nicolas Cage". Screen Comment. January 23, 2019. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage Nabs Lead in Sci-Fi Thriller 'Color Out of Space'". The Hollywood Reporter. January 25, 2019. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage Nabs Lead in Sci-Fi Thriller 'Color Out of Space'". The Hollywood Reporter. January 23, 2019. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "토론토, 미드나잇 매드니스, 디스커버리, TIFF Docs, 시네마테크를 공개합니다." 2019년 8월 8일 웨이백 머신에서 아카이브되었습니다. 스크린데일리 2019년 8월 8일

- ^ Tsirbas, Christos (September 8, 2019). "Toronto: Nicolas Cage Tells Spotlight Initiative Awards Art Is "Healthiest Medicine"". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Erbland, Kate (November 8, 2019). "'Color Out of Space' Trailer: Nicolas Cage Tackles H.P. Lovecraft in Trippy Alien Invasion Thriller". IndieWire. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ Nordine, Michael (December 14, 2018). "Nicolas Cage Calls 'Prisoners of the Ghostland' 'The Wildest Movie I've Ever Made'". IndieWire. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Squires, John (December 14, 2020). "Your New Nic Cage Obsession May End Up Being Sion Sono's Action-Horror Movie 'Prisoners of the Ghostland'". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (December 15, 2020). "Sundance Film Festival Lineup Features 38 First-Time Directors, Including Rebecca Hall and Robin Wright". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (May 4, 2020). "Nicolas Cage to play Joe Exotic in Tiger King miniseries". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage's Tiger King TV drama scrapped by Amazon". BBC News. July 14, 2021. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Croods 2 in the Works at DreamWorks Animation". ComingSoon.net. April 17, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage, Ryan Reynolds and Emma Stone Confirmed for The Croods 2". ComingSoon.net. September 9, 2013. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (July 14, 2021). "'Pig': Nicolas Cage skips the hamminess in an elegant story of pain and purpose". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage's 'Unbearable Weight' Gets Rare Perfect Rotten Tomatoes Score". Maxim. March 16, 2022. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Kit, Borys (November 30, 2021). "Nicolas Cage to Star as Dracula in Universal Monster Movie 'Renfield' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Kit, Borys (December 1, 2021). "Awkwafina Joins Nicolas Cage, Nicholas Hoult in Universal's 'Renfield'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Cavanaugh, Patrick (February 3, 2022). "Dracula Spinoff Renfield Announces Production Start With Set Photo". ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ @DeadbyDaylight (May 17, 2023). "It's the performance of a lifetime. Dead by Daylight: Nicolas Cage. Coming to a realm near you. Learn more on July 5th" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (May 24, 2023). "'The Flash' Director Just Announced the Movie's Most Shocking Cameo That's Decades in the Making". Variety. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ Agger, Michael (December 23, 2002). "Nic Cage's unfortunate Sonny incident". Slate. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Shepard, Jim (September 10, 2000). "FILM; Again, Nosferatu, the Vampire Who Will Not Die". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "The Dresden Files". TV Guide. Archived from the original on June 25, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Susman, Gary (October 1, 2002). "Book Value". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ Bowles, Scott (July 3, 2007). "Cage and son work comic 'Voodoo'". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "ISSUU". Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c Buckmaster, Luke (August 13, 2018). "I watched Nicolas Cage movies for 14 hours straight, and I'm sold". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Nicolas Cage는 자신만의 연기 방식을 가지고 있고 그것은 'Nouveau Shamanic'이라고 불립니다. Wayback Machine" 영화관에 2011년 8월 20일에 보관되었습니다. 2011년 8월 23일 회수

- ^ Nordine, Michael (April 3, 2014). "Nicolas Cage Explains His Acting Style, And His Legacy". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Nicholas Cage, Robert Bierman (1999). Vampire's Kiss (Motion picture). Event occurs at 9:35–45.

I guess in my own mind I [Nicholas Cage] had this idea that there could be a new expression in acting. I was weaned, oddly enough, on vampire—German expressionism films like Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and I wanted to be able to use that kind of silent film style of acting

- ^ Freeman, Hadley (October 1, 2018). "Nicolas Cage: 'If I don't have a job to do, I can be very self-destructive'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ Nicolas Cage Replies to Fans on the Internet Actually Me GQ, archived from the original on March 31, 2022, retrieved March 31, 2022

- ^ Macaluso, Beth Anne (June 15, 2015). "15 Times Stars Took Method Acting Too Far". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Lynch, Alex David (June 21, 2019). "Nicolas Cage Required Hot Yogurt On His Toes To Enjoy A Love Scene With Jennifer Beals During 'Vampire's Kiss'". The Playlist. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "The Ultimate List: Celebrity Black Belts & Martial Artists". Martial Arts & Action Movies. April 9, 2015. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "Esclusivo: Nicolas Cage, domatore di serpenti". Film.it (in Italian). September 2, 2013. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Hawke, Ethan (June 5, 2013). "I Am Ethan Hawke – AMAA". Reddit. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Billson, Anne (July 3, 2013). "The wonderfully mad world of Nicolas Cage". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

Cage's mega-acting can be a marvellous thing to behold: the bug-eyes, the yelling, the Mick Jagger poses, the Oscar-winning lugubriousness.

- ^ Whittaker, Richard (January 31, 2017). "Nicolas Cage Takes Over the Alamo: Watch the mega-acting star perform Edgar Allan Poe". Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 26, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

Yet what came out most was how Cage, whose reputation is for what has been dubbed mega-acting, takes his work incredibly seriously.

- ^ Anon. (April 5, 1999). "Scoop". People. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ "Oscar acceptance speech of Sean Penn". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. February 29, 2004. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Peterson, Alex (October 16, 2013). "Criminally Underrated: Nicolas Cage". Spectrum Culture.

- ^ Flood, Alex (March 18, 2018). "In defence of Nicolas Cage". NME. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ Palmer, Frank (January 7, 2018). "Why Nicolas Cage Is Secretly The Greatest Actor Ever". ScreenGeek.net. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ Lang, Brent (July 15, 2021). "'Pig' Star Nicolas Cage on Abandoning Hollywood: 'I've Gone Into My Own Wilderness'". Variety. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage's Son Weston Cage Welcomes Baby Boy Lucian Augustus With Wife Danielle". Us Weekly. July 3, 2014. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage's divorce from Patricia Arquette". Hello!. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Cage and Presley divorce made final". Today. May 26, 2004. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage and Alice Kim Marriage Profile". About.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2004. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Baby boy for actor Cage and wife". BBC News. October 4, 2005. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Kimble, Lindsey (June 24, 2016). "Nicolas Cage and Wife Alice Kim Are Separated, Rep Confirms". People. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Seemayer, Zach (March 28, 2019). "Nicolas Cage Files for Annulment With New Wife 4 Days After Getting Married". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ Seemayer, Zach (June 3, 2019). "Nicolas Cage Officially Divorced From Ex-Wife After 4-Day Marriage". Entertainment Tonight. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Napoli, Jessica (March 5, 2021). "Nicolas Cage marries Riko Shibata, his fifth wife, in Las Vegas ceremony: 'We are very happy'". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Andaloro, Angela; Leon, Anya (September 7, 2022). "Nicolas Cage and Wife Riko Welcome First Baby Together, Daughter August Francesca". People. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ Byrne, Paul (March 27, 2009). "Cage without a key". Irish Independent. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ Rappaport, Scott (May 26, 2003). "Nicolas Cage visits UCSC". UC Santa Cruz Currents. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Bort, Ryan (March 20, 2019). "What Is Going on With Andrew Yang's Candidacy?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Marchese, David (August 7, 2019). "Nicolas Cage on his legacy, his philosophy of acting and his metaphorical — and literal — search for the Holy Grail". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on August 11, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage Lived National Treasure by Searching for the Holy Grail". Vanity Fair. August 7, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ "Generous Celebs". Forbes. May 4, 2006. Archived from the original on July 14, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage Donate $2 million to Amnesty". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Cage donates 1 Million to Katrina's Victims". Softpedia. September 2, 2005. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ "ILO launches artists programme, Nicolas Cage calls for an end to child labour". International Labour Organization. October 15, 2012. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage donates $5000 to Telethon while in WA filming upcoming Hollywood blockbuster The Surfer". PerthNow. October 22, 2023. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage wins United Nations humanitarian award". BBC News. December 5, 2009. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage Appointed UNODC Goodwill Ambassador for Global Justice" (Press release). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. December 4, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "UNODC Goodwill Ambassador Nicolas Cage renews his appointment" (Press release). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. November 5, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Beale, Lauren (April 8, 2010). "Foreclosure auction of Nicolas Cage's mansion is a flop". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy (2014). "The Highest Paid Actors – 2014". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (May 19, 2006). "Nicolas Cage Buys Private Island". People. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Werner, Frank (August 10, 2006). "Liebeserklärung ans neue Heim" [Declaration of love for a new home]. Onetz (in German). Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Actor Nicolas Cage reportedly buys a 24,664-square-foot mansion in Middletown, Rhode Island for $15.7M". Berg Properties. August 2, 2007. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage Sells Gray Craig Estate – SOLD". Pricey Pads.com. December 23, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Hodgson, Martin (July 30, 2007). "Nicolas Cage joins Britain's castle-owning classes". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ Chittenden, Maurice (July 29, 2007). "Another day, another castle: Cage adds to his empire". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ Miller, Daniel (July 26, 2012). "Who in Hollywood Owns a Private Island". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage hit with $6.2 million tax bill". Houston Chronicle. August 3, 2009. Archived from the original on August 6, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Rodriguez, Brenda (November 1, 2009). "Nicolas Cage Blames Advisor for Financial Ruin". People. Archived from the original on November 4, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Serjeant, Jill (October 16, 2009). "Nicolas Cage sues ex-manager for "financial ruin". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 21, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage sued for $2 million". The Economic Times. October 3, 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ a b "Nic Cage spent too much: Ex-manager says". CNN. November 17, 2009. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "Actor Nicolas Cage returns stolen dinosaur skull he bought". Reuters. December 22, 2015. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Nicolas Cage 인터뷰 – "Late Show with David Letterman", 2008년 9월 2일

- ^ a b Yousuf, Hibah (November 13, 2009). "Nicolas Cage: Movie star, foreclosure victim". CNN. Archived from the original on November 17, 2009. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Beale, Lauren (April 8, 2010). "Foreclosure auction of Nicolas Cage's mansion is a flop". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ Beale, Lauren (November 11, 2010). "Nicolas Cage's Bel-Air home goes to new owner for just $10.5 million". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Super price for Superman comic". CNN. December 2, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Harris, Mike (April 10, 2011). "Simi man helps recover $1 million comic book stolen from Nicolas Cage". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ 마틴, 에미. "Nicolas Cage가 어떻게 1억 5천만 달러를 저택, 개인적인 섬, 그리고 진짜 공룡 두개골에 불었는가." 2017년 10월 3일, 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에서 보관, CNBC, 2017년 5월 10일 발행. 2017년 5월 14일 회수.

- ^ Smith, Jacob (March 23, 2022). "Nicolas Cage Confirms He Paid Off His Debts, Disses Disney As He Promotes 'The Unbearable Weight Of Massive Talent'". Bounding Into Comics. Archived from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Thomson, Katherine (December 4, 2008). "Nicolas Cage Wins Apology And Damages From Kathleen Turner". HuffPost. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Chivers, Tom (April 4, 2008). "Nicolas Cage 'didn't steal a chihuahua,' admits former co-star Kathleen Turner". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Pierce, Andrew (April 5, 2008). "Kathleen Turner sorry for labelling Nicolas Cage a dog-napper". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Holmwood, Leigh (April 4, 2008). "Cage wins libel battle over 'stolen dog'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ 디트로이트 프리 프레스, 2009년 12월 10일 12D 페이지

- ^ Duke, Alan (June 15, 2011). "Nicolas Cage settles lawsuit with his son's mother". CNN. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "Actor Nicolas Cage arrested in New Orleans". Reuters. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Vilensky, Mike (April 16, 2011). "Nicolas Cage Arrested in New Orleans (Updated)". New York. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage arrested in New Orleans". MSN. Archived from the original on April 18, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Ernest, Eugene (May 9, 2011). "Court Cleared all Allegations on Nicolas Cage". Archived from the original on May 14, 2011.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage no longer facing domestic violence charge for alleged drunken argument with wife". Daily News. New York. Reuters. May 6, 2011. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage". Walkoffame.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "CSU Newsline". Calstate.edu. April 16, 2001. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Julie (February 14, 2012). "Nicolas Cage Explains His Recent Oscar-Shunning Career Choices in Most Confusing, Cage-ian Way Possible". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Nicolas Cage". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2014.