MMR 백신

MMR vaccine MMR 백신 | |

| 의 조합 | |

|---|---|

| 홍역 백신 | 백신 |

| 유행성 이하선염 백신 | 백신 |

| 풍진 백신 | 백신 |

| 임상 데이터 | |

| 상호 | M-M-R II, Priorix, Tresivac, 기타 |

| 기타 이름 | MPR[1] 백신 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 모노그래프 |

| Medline Plus | a601176 |

| 라이선스 데이터 | |

| 임신 카테고리 |

|

| ATC 코드 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 식별자 | |

| CAS 번호 | |

| 켐스파이더 |

|

| | |

MMR 백신은 홍역, 유행성 이하선염, 풍진(독일 홍역)[6]에 대한 백신으로, 약칭 MMR로 불리며, 일반적으로 생후 약 9개월에서 15개월에서 6세에 두 번째 접종 후 최소 [7][8][9]4주 간격으로 투여된다.2회 복용 후, 97%의 사람들이 홍역, 88%가 유행성 이하선염, 그리고 적어도 97%가 [7]풍진으로부터 보호된다.면역력이 [7]없는 사람, HIV/[10][11]AIDS를 잘 통제하고 있는 사람, 면역력이 [8]부족한 사람 중 홍역에 72시간 이내에 노출되는 사람에게도 이 백신이 권장된다.그것은 [12]주사제로 투여된다.

MMR 백신은 전 세계적으로 널리 사용되고 있다.1999년과 [13]2004년 사이에 전세계적으로 5억 개 이상의 도스가 투여되었고,[14] 전세계적으로 백신이 도입된 이후 5억 7천 5백만 개의 도스가 투여되었다.홍역은 예방접종이 [14]보편화되기 전에 매년 260만 명의 사망자를 낳았다.이는 2012년 현재 저소득[update] 국가에서 매년 122,000명까지 감소하였다.[14]예방접종을 통해 2018년 현재[update] 북미와 남미 지역의 홍역 발생률은 매우 [14]낮다.백신을 [14]접종하지 않은 인구에서 질병률이 증가하는 것으로 나타났다.2000년과 2016년 사이에 예방접종은 홍역 사망률을 84%[15] 더 줄였다.

예방접종의 부작용은 일반적으로 경미하며 특별한 [16]치료 없이도 해결된다.여기에는 발열, 주사 부위의 [16]통증 또는 홍조 등이 포함될 수 있습니다.심각한 알레르기 반응은 백만 [16]명 중 한 명꼴로 발생한다.MMR 백신은 살아있는 바이러스를 포함하고 있기 때문에 임신 중에는 권장되지 않지만 모유 [7]수유 중에 투여될 수 있습니다.그 백신은 다른 [16]백신과 동시에 투여해도 안전하다.최근 예방접종을 받는다고 해서 홍역, 유행성 이하선염, 풍진이 [7]다른 사람에게 전염될 위험이 높아지지는 않는다.MMR 면역과 자폐 스펙트럼 [17][18][19]장애 사이의 연관성에 대한 증거는 없다.MMR 백신은 세 [7]가지 질병의 살아있는 약화된 바이러스의 혼합물이다.

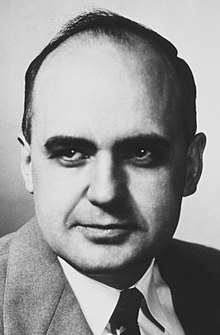

MMR 백신은 Maurice Hilleman에 [6]의해 개발되었습니다.1971년 [20]Merck에 의해 미국에서 사용이 허가되었다.홍역, 유행성 이하선염, 풍진 백신은 각각 1963년, 1967년, 1969년에 면허되었다.[20][21]두 번째 선량에 대한 권고는 [20]1989년에 도입되었다.수두도 커버하는 MMRV 백신이 [7]대신 사용될 수 있다.유행성 이하선염에 대한 보장이 없는 MR 백신도 가끔 사용된다.[22]

의료용

코크란은 "MMR과 MMRV 백신의 안전성과 효과에 [17]대한 기존 증거는 홍역 유행성 이하선염 풍진과 수두와 관련된 질병과 사망률을 줄이기 위해 전지구적 홍역 근절을 목표로 하는 현재의 대량 면역 정책을 뒷받침한다"고 결론지었다.

복합 MMR 백신은 동시에 3회 주사하는 것보다 덜 고통스럽게, 다른 날짜에 3회 주사하는 것보다 더 빠르고 효율적으로 면역성을 유도한다.영국 공중 보건부는 1988년 현재 단일 복합 백신을 제공하는 것이, 두 백신을 따로 접종할 수 있는 선택권을 주는 것이 아니라,[23] 백신 섭취를 증가시켰다고 보고했습니다.

홍역

홍역 예방 백신이 널리 사용되기 전에는 질병 발생률이 너무 높아 감염이 "[24]죽음과 세금만큼 불가피한" 것으로 느껴졌다.미국에서 보고된 홍역 환자는 1963년 백신이 도입된 이후 매년 수십만 명에서 수만 명으로 감소했다.1971년과 1977년 발병 이후 백신 섭취가 증가하면서 1980년대에는 매년 수천 건의 사례가 발생했다.1990년에 거의 30,000명의 환자가 발생하자 백신 접종을 다시 추진하고 권장 일정에 두 번째 백신을 추가했다.미국에서는 1997년부터 2013년 사이에 매년 200건 미만의 사례가 보고되었고, 이 질병은 더 이상 그곳의 [25][26][27]풍토병으로 여겨지지 않는다.

홍역 예방접종이 질병, 장애, 사망을 예방하는 효과는 잘 입증되어 있다.미국에서 홍역 백신을 처음 20년 동안 허가 받은 것은 5200만 건의 홍역 예방접종, 17,400건의 지적 장애, 5,200명의 [28]사망을 막았다.1999-2004년 동안 세계보건기구와 유니세프가 주도한 전략은 홍역 예방접종 범위를 개선하여 [29]전 세계적으로 약 140만 명의 홍역 사망자를 방지했다.2000년과 2013년 사이에 홍역 예방접종은 [30]홍역으로 인한 사망을 75% 감소시켰다.

홍역은 세계 많은 지역에서 흔하다.비록 미국에서 2000년에서 탈락해 언명한 백신 접종과 예방 접종을 거부하는 사람들과 좋은 통신의 높은 금리는 절반 이상이 한 백신 접종을 하지 않은 indivi엤기 때문을 유지하고, 발병 홍역의 U.S.[31일]에 홍역은 2005년 미국의 신고된 66건 중에서 제거하는 것이 것을 방지할 필요 있다.dua나는 루마니아 [32]방문 중에 홍역에 걸렸다.이 사람은 예방접종을 받지 않은 많은 아이들과 함께 지역사회로 돌아왔다.그 결과 34명이 감염되었으며, 대부분 어린이와 거의 모든 사람이 감염되었다. 9%는 병원에 입원했으며, 발병 억제 비용은 167,685달러로 추산되었다.주변 [31]지역사회의 높은 백신 접종률로 인해 큰 전염병을 피할 수 있었다.

2017년 미네소타 소말리아계 미국인 커뮤니티에서 홍역이 발생했는데, 이 지역에서는 백신이 자폐증을 유발할 수 있다는 잘못된 인식으로 MMR 예방접종률이 떨어졌다.질병통제예방센터는 2017년 [33]4월 10일까지 65명의 발병 어린이를 기록했다.

풍진

독일 홍역으로도 알려진 풍진 또한 광범위한 예방 접종 전에는 매우 흔했다.풍진의 주요 위험은 아기가 선천성 풍진에 걸릴 수 있는 임신 기간 동안이며, 이것은 심각한 선천성 [34]기형을 일으킬 수 있다.

유행성 이하선염

유행성 이하선염은 한 때 특히 어린 시절에 매우 흔했던 또 다른 바이러스 질환이다.유행성 이하선염은 사춘기 이후 남성에게 감염되면 양쪽 난초염으로 불임으로 [35]이어질 수 있다.

행정부.

MMR 백신은 일반적으로 생후 12개월에 첫 번째 용량인 [12]피하주사에 의해 투여된다.두 번째 투여량은 첫 번째 [36]투여 후 1개월 이내에 투여할 수 있다.두 번째 선량은 첫 번째 선량 후 홍역 면역이 생기지 않은 소수의 사람들(2-5%)에게 면역력을 생성하는 선량이다.미국에서는 유치원에 입학하기 전에 하는 것이 [37]편리하기 때문이다.홍역이 흔한 지역은 일반적으로 생후 9개월에 첫 번째 용량과 [8]15개월에 두 번째 용량을 권장한다.

안전.

MMR 백신의 각 성분에서 드물게 심각한 부작용이 발생할 수 있습니다.10%의 어린이들이 첫 예방접종 [38]후 5-21일 후에 발열, 불쾌감, 발진이 생기고 3%는 평균적으로 [39]18일 동안 관절통이 지속된다.나이 든 여성들은 관절통, 급성 관절염, 그리고 심지어 드물게 만성 [40]관절염의 위험이 더 높은 것으로 보인다.무지외반증은 매우 드물지만 [41]백신에 대한 심각한 알레르기 반응이다.한 가지 원인은 계란 [42]알레르기일 수 있다.2014년에 FDA는 급성 파종성 뇌척수염(ADEM)과 횡골수염이라는 두 가지 가능한 부작용을 승인했으며, 패키지 [43]삽입물에 "걷기 어려움"을 추가할 수 있도록 허용했다.2012년 IOM 보고서에 따르면 MMR 백신의 홍역 성분은 면역력이 떨어진 사람에게 홍역 포함 체뇌염을 일으킬 수 있다.이 보고서는 또한 MMR 백신과 [44]자폐증 사이의 어떠한 연관성도 거부했다.백신의 일부 버전은 항생제 [19]네오마이신을 포함하고 있기 때문에 이 항생제에 알레르기가 있는 사람들에게는 사용되어서는 안 된다.

신경 질환에 대한 보고의 수는 우라베 유행성 이하선염 균주를 포함한 MMR 백신과 바이러스 뇌수막염의 [40][45]일종인 무균성 뇌수막염의 드문 부작용 사이의 연관성에 대한 증거 외에는 매우 적다.영국 국립보건국은 1990년대 초 일시적인 가벼운 바이러스성 뇌수막염 증세를 이유로 우라베형 이하선염의 사용을 중단하고 [46]대신 제릴 린형 이하선염의 형태로 전환했다.Urabe 균주는 여전히 많은 국가에서 사용되고 있으며, Urabe 균주의 MMR은 Jeryl Lynn [47]균주의 MMR보다 제조 비용이 훨씬 저렴하며, 다소 높은 부작용 비율과 함께 효과가 높은 균주는 전체적인 부작용 [46]발생률을 감소시키는 이점이 있을 수 있다.

Cochrane 리뷰에 따르면 위약과 비교하여 MMR 백신은 더 적은 상기도 감염, 더 많은 자극성 및 유사한 수의 다른 [17]부작용과 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났다.

자연 후천성 홍역은 면역 혈소판 감소성 자반증(ITP, 자반성 발진, 2개월 이내에 해결되는 출혈 경향 증가)과 함께 발생하는 경우가 많으며, 1~2만 [17]건에서 발생한다.약 40,000명 중 1명의 어린이가 MMR 백신 [17]접종 후 6주 이내에 ITP를 획득할 것으로 생각된다.6세 미만의 ITP는 일반적으로 가벼운 질병이며, 장기적인 결과를 [48][49]초래하는 경우는 거의 없습니다.

자폐증에 대한 잘못된 주장

1998년 Andrew Wakefield 등은 경쟁 백신을 지원하면서 대장 증상과 자폐증 또는 MMR [50]백신 투여 직후 획득한 기타 장애를 가진 12명의 어린이에 대한 사기 논문을 발표했다.2010년, Wakefield의 연구는 General Medical Council에 의해 "최악의"[51] 것으로 판명되었고, The Lancet은 [52][53]그 논문을 완전히 철회했다.The Lancet의 철회 후 3개월 후, Wakefield는 The [54]Lancet에 게재된 연구에서 고의적인 위조를 확인하는 성명서와 함께 영국의 의료 등록부에서 삭제되었고,[55] 영국에서 의사 개업을 금지당했다.이 연구는 영국 의학 [56]저널에 의해 2011년에 사기라고 선언되었다.

웨이크필드의 발표 이후, 여러 동료들이 검토한 연구들은 백신과 [17][57]자폐증 사이의 어떠한 연관성도 보여주지 못했다.질병통제예방센터,[58] [59]국립과학아카데미 의학연구소, 영국 국립보건국[60], 코크레인 도서관[17] 리뷰는 모두 연관성의 증거가 없다고 결론지었다.

백신을 3회 분량으로 투여해도 부작용의 가능성이 감소하지 않고 먼저 [57][61]예방접종을 받지 않은 두 가지 질환에 의한 감염 가능성이 높아진다.보건 전문가들은 MMR-자율주의 논쟁에 대한 언론 보도가 [62]백신 접종률의 감소를 촉발시켰다고 비판해왔다.Wakefield의 기사가 발표되기 전에는 영국의 MMR 접종률이 92%였지만, 발표 후에는 80% 이하로 떨어졌다.1998년 영국에는 56명의 홍역 환자가 발생했고, 2008년에는 1348명의 환자가 발생했으며,[63] 두 명의 사망자가 확인되었다.

일본에서는 MMR 트리플렛은 사용하지 않습니다.면역력은 홍역과 풍진 혼합 백신을 통해 달성되고, 그 후 유행성 이하선염 전용 백신을 통해 달성된다.이것은 그 나라의 자폐증 비율에 영향을 미치지 않았고, MMR 자폐증 [64]가설을 더욱 반증했다.

역사

MMR 백신의 성분 바이러스 변종은 모든 바이러스가 복제를 위해 살아있는 숙주 세포를 필요로 하기 때문에 동물과 인간 세포에서 증식을 통해 개발되었습니다.

예를 들어, 유행성 이하선염과 홍역 바이러스의 경우, 바이러스 변종은 태아화된 계란에서 배양되었다.이것은 닭 세포에 적합하고 인간 세포에 적합하지 않은 변종 바이러스를 만들어냈다.그러므로 이러한 변종은 감쇠 변종이라고 불린다.이러한 변종들은 야생 변종보다 인간 신경세포에 덜 치명적이기 때문에 신경쇠약이라고 불리기도 한다.

루벨라 성분인 메루박스는 6년 [65][66]전인 1961년 도출된 인간 배아 폐세포주 WI-38(위스타 연구소 이름)을 이용한 증식을 통해 1967년 개발됐다.

| 면역된 질병 | 성분 백신 | 바이러스 균주 | 전파 매체 | 배지 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 홍역 | 감쇠폭스 | 엔더의 감쇠 에드먼스턴[67] 균주 | 병아리배아세포배양 | 중형 199 |

| 유행성 이하선염 | 유행성 이하선염[68] | 제릴 린(B레벨) 변형률[69] | ||

| 풍진 | 머루백스 2세 | 위스타 RA 27/3주 생감쇠 풍진 바이러스 | WI-38 인간 배아 세포주 | MEM(완충염, 태아 소 혈청, 인간 혈청 알부민, 네오마이신 등을 포함한 용액) |

"MPR 백신"은 이 백신을 지칭할 때도 사용되며, "P"는 [1]유행성 이하선염에 의한 이하선염을 말한다.

Merck MMR II는 동결 건조(경화)되어 있으며 살아있는 바이러스를 포함하고 있습니다.주입하기 전에 제공된 [70]용매를 사용하여 재구성합니다.

2018년에 발표된 리뷰에 따르면, Pluserix로 알려진 글락소스미스클라인(GSK) MMR 백신은 "슈바르츠 홍역 바이러스, 제릴 린 유사 유행성 이하선염 변종, RA27/3 풍진 바이러스를 포함하고 있다"[71]고 한다.

플러세릭스는 [72]1999년에 헝가리 사람들에게 소개되었다.엔더의 에드먼스턴주는 1999년부터 헝가리에서 Merck MMR II [72]제품에 사용되어 왔습니다.약화된 슈바르츠 홍역을 사용하는 GSK PRIVIX 백신은 2003년 [72]헝가리인들에게 도입되었다.

MMRV 백신

MMR 백신은 홍역, 유행성 이하선염, 풍진, 수두(닭머리) 혼합 백신으로 백신 [36]투여를 간소화하기 위해 MMR 백신의 대체 백신으로 제안되어 왔다.예비 데이터에 따르면 MMR과 수두 주사는 각각 10,000회당 4회인 반면, MMRV 백신 접종 시 10,000회당 9회의 열성 발작률이 나타난다. 따라서 미국 보건 당국은 별도의 [73]주사보다 MMRV 백신 사용을 선호하지 않는다.

2012년[74] 연구에서 소아과 의사 및 가정의사는 MMRV에서 발열성 발작(발작)의 위험 증가에 대한 인식을 측정하기 위해 설문 조사를 보냈습니다. 가정의 74%와 소아과 의사 29%는 발열성 발작의 위험 증가에 대해 알지 못했습니다.정보 진술서를 읽은 후 가정의의 7%와 소아과 의사의 20%만이 건강한 12개월에서 15개월 된 아이에게 MMRV를 추천할 것이다.MMR+V보다 MMRV를 권장할 때 "가장 중요한" 결정 요소로 보고된 요인은 ACIP/AAFP/AAP 권고 사항(소아과 의사 77%, 가정의 의사 73%)이었다.

MR백신

이 백신은 홍역과 풍진에는 해당되지만 [22]유행성 이하선염에는 해당되지 않습니다.2014년 현재 "소수의 (미확인) 국가"[22]에서 사용되고 있다.

사회와 문화

종교적 관심사

일부 브랜드의 백신은 돼지에서 유래한 젤라틴을 안정제로 [75]사용한다.돼지 유도체가 없는 대체 백신이 승인되고 이용 [75]가능함에도 불구하고,[75][76] 이것은 일부 지역사회에서 점유율을 감소시켰다.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b Grignolio A (2018). Vaccines: Are they Worth a Shot?. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 9783319681061. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ "Measles virus vaccine / mumps virus vaccine / rubella virus vaccine (M-M-R II) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ "M-M-R II- measles, mumps, and rubella virus vaccine live injection, powder, lyophilized, for suspension". DailyMed. 23 May 2022. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Priorix- measels, mumps, and rubella vaccine, live kit". DailyMed. 3 June 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "M-M-RVaxPro EPAR". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Maurice R. Hilleman, PhD, DSc". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): 225–226. July 2005. doi:10.1053/j.spid.2005.05.002. PMID 16044396.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (2017). "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017". Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 92 (17): 205–227. hdl:10665/255149. PMID 28459148.

- ^ World Health Organization (January 2019). "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2017 - Recommendations". Vaccine. 37 (2): 219–222. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.066. PMID 28760612.

- ^ Kinney R (2 May 2017). "Core Concepts –,Immunizations in Adults – Basic HIV Primary Care – National HIV CurriculumImmunizations in Adults". www.hiv.uw.edu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Watson JC, Hadler SC, Dykewicz CA, Reef S, Phillips L (22 May 1998). "Measles, mumps, and rubella – vaccine use and strategies for elimination of measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome and control of mumps: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). MMWR Recomm Rep. 47 (RR-8): 1–57. PMID 9639369. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Administering MMR Vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "Progress in Reducing Global Measles Deaths, 1999–2004". CDC. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Addressing misconceptions on measles vaccination". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Measles Fact Sheet #286". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d "MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) Vaccine Information Statement". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 August 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Marchione P, Debalini MG, Demicheli V (November 2021). "Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD004407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5. PMC 8607336. PMID 34806766.

- ^ Hussain A, Ali S, Ahmed M, Hussain S (July 2018). "The Anti-vaccination Movement: A Regression in Modern Medicine". Cureus. 10 (7): e2919. doi:10.7759/cureus.2919. PMC 6122668. PMID 30186724.

- ^ a b Spencer JP, Trondsen Pawlowski RH, Thomas S (June 2017). "Vaccine Adverse Events: Separating Myth from Reality". American Family Physician. 95 (12): 786–794. PMID 28671426.

- ^ a b c Goodson JL, Seward JF (December 2015). "Measles 50 Years After Use of Measles Vaccine". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 29 (4): 725–743. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.08.001. PMID 26610423.

- ^ "Measles: information about the disease and vaccines Questions and Answers" (PDF). Immunization Action Coalition. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Information Sheet Observed Rate of Vaccine Reactions, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccines" (PDF). fdaghana.gov.gh. May 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR): use of combined vaccine instead of single vaccines". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Babbott FL Jr; Gordon JE (1954). "Modern measles". Am J Med Sci. 228 (3): 334–61. doi:10.1097/00000441-195409000-00013. PMID 13197385.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (October 1994). "Summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 1993" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 42 (53): i–xvii, 1–73. PMID 9247368. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (July 2009). "Summary of Notifiable Diseases --- United States, 2007" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 56 (53). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. (2015). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ISBN 978-0990449119. Archived from the original on 2016-12-30. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ^ Bloch AB, Orenstein WA, Stetler HC, et al. (1985). "Health impact of measles vaccination in the United States". Pediatrics. 76 (4): 524–32. doi:10.1542/peds.76.4.524. PMID 3931045. S2CID 6512947.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (March 2006). "Progress in reducing global measles deaths, 1999–2004" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55 (9): 247–9. PMID 16528234. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ "Measles Fact Sheet #286". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b Parker AA, Staggs W, Dayan GH, Ortega-Sánchez IR, Rota PA, Lowe L, et al. (2006). "Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States". N Engl J Med. 355 (5): 447–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060775. PMID 16885548. S2CID 34529542.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (December 2006). "Measles—United States, 2005" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55 (50): 1348–51. PMID 17183226. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ Hall V, Banerjee E, Kenyon C, Strain A, Griffith J, Como-Sabetti K, et al. (July 2017). "Measles Outbreak — Minnesota April–May 2017" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66 (27): 713–717. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 5687591. PMID 28704350. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ "Rubella vaccine information". National Network for Immunization Information. 2006-09-25. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ^ Jequier AM (2000). Male infertility: a guide for the clinician. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-632-05129-8. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ a b Vesikari T, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Rentier B, Gershon A (2007). "Increasing coverage and efficiency of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and introducing universal varicella vaccination in Europe: a role for the combined vaccine". Pediatr Infect Dis J. 26 (7): 632–638. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3180616c8f. PMID 17596807. S2CID 41981427.

- ^ "MMR vaccine questions and answers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2004. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ^ Harnden A, Shakespeare J (2001). "10-minute consultation: MMR immunisation". BMJ. 323 (7303): 32. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7303.32. PMC 1120664. PMID 11440943.

- ^ Thompson GR, Ferreyra A, Brackett RG (1971). "Acute Arthritis Complicating Rubella Vaccination" (PDF). Arthritis & Rheumatism. 14 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1002/art.1780140104. hdl:2027.42/37715. PMID 5100638. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-25. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- ^ a b Schattner A (2005). "Consequence or coincidence? The occurrence, pathogenesis and significance of autoimmune manifestations after viral vaccines". Vaccine. 23 (30): 3876–86. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.005. PMID 15917108.

- ^ Carapetis JR, Curtis N, Royle J (2001). "MMR immunisation. True anaphylaxis to MMR vaccine is extremely rare". BMJ. 323 (7317): 869. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7317.869a. PMC 1121404. PMID 11683165.

- ^ Fox A, Lack G (October 2003). "Egg allergy and MMR vaccination". Br J Gen Pract. 53 (495): 801–2. PMC 1314715. PMID 14601358. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26.

- ^ "Approval for label change". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2012). Stratton K, Ford A, Rusch E, Clayton EW (eds.). Adverse Effects of Vaccines. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13164. ISBN 978-0-309-21435-3. PMID 24624471. Bookshelf ID: NBK190024.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (1994). "Measles and mumps vaccines". In Stratton KR, Howe CJ, Johnston RB (eds.). Adverse Events Associated with Childhood Vaccines: Evidence Bearing on Causality. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/2138. ISBN 978-0-309-07496-4. PMID 25144097. Bookshelf ID: NBK236291. Archived from the original on 2015-08-24. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ^ a b Colville A, Pugh S, Miller E, Schmitt HJ, Just M, Neiss A (1994). "Withdrawal of a mumps vaccine". Eur J Pediatr. 153 (6): 467–8. doi:10.1007/BF01983415. PMID 8088305. S2CID 43300463.

- ^ Fullerton KE, Reef SE (2002). "Commentary: Ongoing debate over the safety of the different mumps vaccine strains impacts mumps disease control". Int J Epidemiol. 31 (5): 983–4. doi:10.1093/ije/31.5.983. PMID 12435772.

- ^ Sauvé LJ, Scheifele D (January 2009). "Do childhood vaccines cause thrombocytopenia?". Paediatr Child Health. 14 (1): 31–2. doi:10.1093/pch/14.1.31. PMC 2661332. PMID 19436461.

- ^ Black, C., Kaye, J. A. and Jick, H. (2003). "MMR vaccine and idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 55 (1): 107–111. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01790.x. PMC 1884189. PMID 12534647.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Wakefield A, Murch S, Anthony A; et al. (1998). "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children". Lancet. 351 (9103): 637–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0. PMID 9500320. S2CID 439791. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크)(추출) - ^ Cassandra Jardine (29 Jan 2010). "GMC brands Dr Andrew Wakefield 'dishonest, irresponsible and callous'". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Retraction—Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children". Lancet. 375 (9713): 445. February 2010. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60175-4. PMID 20137807. S2CID 26364726.

- ^ Triggle N (2 February 2010). "Lancet accepts MMR study 'false'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "General Medical Council, Fitness to Practise Panel Hearing, 24 May 2010, Andrew Wakefield, Determination of Serious Professional Misconduct" (PDF). General Medical Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ Meikle J, Sarah B (24 May 2010). "MMR row doctor Andrew Wakefield struck off register". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H (2011). "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ. 342 (jan05 1, c7452): c7452. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452. PMID 21209060. S2CID 43640126.

- ^ a b National Health Service (2004). "MMR: myths and truths". Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ "Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008-08-22. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2004). Immunization Safety Review. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10997. ISBN 978-0-309-09237-1. PMID 20669467. Bookshelf ID: NBK25344.

- ^ MMR Fact Sheet 2007-06-15 영국 국립보건서비스(National Health Service)의 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브된 MMR 팩트 시트.2007년 6월 13일에 액세스.

- ^ MMR vs 3개의 개별 백신:

- Halsey NA; Hyman SL; Conference Writing Panel (2001). "Measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and autistic spectrum disorder: report from the New Challenges in Childhood Immunizations Conference convened in Oak Brook, Illinois, June 12–13, 2000". Pediatrics. 107 (5): e84. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.e84. PMID 11331734.

- Leitch R, Halsey N, Hyman SL (2002). "MMR—Separate administration-has it been done?". Pediatrics. 109 (1): 172. doi:10.1542/peds.109.1.172. PMID 11773568. Archived from the original on 2007-02-16. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- Miller E (2002). "MMR vaccine: review of benefits and risks". J Infect. 44 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0930. PMID 11972410.

- ^ "Doctors issue plea over MMR jab". BBC News. 2006-06-26. Archived from the original on 2018-07-07. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Thomas J (2010). "Paranoia strikes deep: MMR vaccine and autism". Psychiatric Times. 27 (3): 1–6. Archived from the original on 2015-04-09.

- ^ Honda H, Shimizu Y, Rutter M (2005). "No effect of MMR withdrawal on the incidence of autism: a total population study". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 46 (6): 572–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.1619. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01425.x. PMID 15877763.

- ^ Plotkin SA, Vaheri A (1967). "Human fibroblasts infected with rubella virus produce a growth inhibitor". Science. 156 (3775): 659–661. Bibcode:1967Sci...156..659P. doi:10.1126/science.156.3775.659. PMID 6023662. S2CID 32622296.

- ^ Hayflick L, Moorhead PS (1967). "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains". Exp. Cell Res. 25 (3): 585–621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. PMID 13905658.

- ^ "Attenuvax Product Sheet" (PDF). Merck & Co. 2006. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-31. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Merck Co. (2002). "MUMPSVAX (Mumps Virus Vaccine Live) Jeryl Lynn Strain" (PDF). Merck Co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

- ^ Young ML, Dickstein B, Weibel RE, Stokes J Jr, Buynak EB, Hilleman MR (1967). "Experiences with Jeryl Lynn strain live attenuated mumps virus vaccine in a pediatric outpatient clinic". Pediatrics. 40 (5): 798–803. doi:10.1542/peds.40.5.798. PMID 6075651. S2CID 35878536.

- ^ "About the Vaccine – MMR and MMRV Vaccine Composition and Dosage". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2021-01-26. Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 2021-10-07.

- ^ Reef SE, Plotkin SA (2018). "Rubella Vaccines". Plotkin's Vaccines. pp. 970–1000.e18. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35761-6.00052-3. ISBN 9780323357616.

- ^ a b c Böröcz K, Csizmadia Z, Markovics Á, Farkas N, Najbauer J, Berki T, Németh P (February 2020). "Application of a fast and cost-effective 'three-in-one' MMR ELISA as a tool for surveying anti-MMR humoral immunity: the Hungarian experience". Epidemiology and Infection. 148: e17. doi:10.1017/S0950268819002280. PMC 7019553. PMID 32014073.

- ^ Klein NP, Yih WK, Marin M, et al. (March 2008). "Update: recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding administration of combination MMRV vaccine" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 57 (10): 258–260. PMID 18340332. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ O'Leary ST, Suh CA, Marin M (Nov 2012). "Febrile seizures and measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine: what do primary care physicians think?". Vaccine. 30 (48): 6731–6733. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.075. PMID 22975026.

- ^ a b c "Vaccines and porcine gelatine" (PDF). Public Health England. August 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Pager T (9 April 2019). "'Monkey, Rat and Pig DNA': How Misinformation Is Driving the Measles Outbreak Among Ultra-Orthodox Jews". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

추가 정보

- World Health Organization (January 2009). The immunological basis for immunization series: module 7: measles (update 2009). World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/44038. ISBN 9789241597555.

- World Health Organization (November 2010). The immunological basis for immunization series: module 16: mumps. World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/97885. ISBN 9789241500661.

- World Health Organization (December 2008). The immunological basis for immunization series: module 11: rubella. World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/43922. ISBN 9789241596848.

- Ramsay M, ed. (December 2019). "Chapter 21: Measles". Immunisation against infectious disease. Public Health England.

- Ramsay M, ed. (April 2013). "Chapter 23: Mumps". Immunisation against infectious disease. Public Health England.

- Ramsay M, ed. (April 2013). "Chapter 28: Rubella". Immunisation against infectious disease. Public Health England.

- Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. (2015). "Chapter 13: Measles". Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ISBN 978-0990449119.

- Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. (2015). "Chapter 15: Mumps". Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ISBN 978-0990449119.

- Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. (2015). "Chapter 20: Rubella". Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ISBN 978-0990449119.

- Roush SW, Baldy LM, Hall MA, eds. (March 2019). "Chapter 7: Measles". Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Atlanta GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- Roush SW, Baldy LM, Hall MA, eds. (March 2019). "Chapter 9: Mumps". Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Atlanta GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- Roush SW, Baldy LM, Hall MA, eds. (March 2019). "Chapter 14: Rubella". Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Atlanta GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

외부 링크

- "Measles Mumps Rubella Vaccines". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- 미국 국립의학도서관의 홍역-볼거리-풍진 백신(MeSH)