결핵

Tuberculosis| 결핵 | |

|---|---|

| 기타 이름 | 폐결핵, 폐결핵, 폐결핵, 대백색병 |

| |

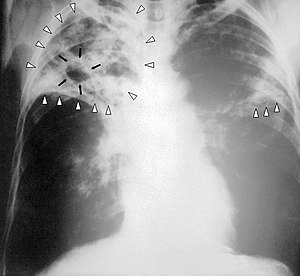

| 진행성 결핵 환자의 흉부 X-ray:양쪽 폐의 감염은 흰색 화살촉으로, 충치의 형성은 검은색 화살촉으로 표시된다. | |

| 전문 | 감염성 질환, 맥박학 |

| 증상 | 만성 기침, 발열, 피 섞인 기침, 체중[1] 감소 |

| 원인들 | 결핵균[1] |

| 위험요소 | 흡연, HIV/AIDS[1] |

| 진단 방법 | CXR, 배양, 투베르쿨린 피부검사, QuantiFERON[1] |

| 차동 진단 | 폐렴, 히스토플라스마증, 살코이드증, 콕시디오이드균증[2] |

| 예방 | 고위험군 선별, 감염자 치료, 칼메테게린균(BCG)[3][4][5] 예방접종 |

| 치료 | 항생제[1] |

| 빈도수. | 25%의 사람([6]잠시 TB) |

| 사망. | 150만 (표준)[7] |

결핵(TB)은 보통 결핵균([1]MTB)에 의해 발생하는 전염병이다.결핵은 일반적으로 폐에 영향을 미치지만 신체의 다른 [1]부위에도 영향을 미칠 수 있다.대부분의 감염은 증상이 없고,[1] 이 경우 잠복결핵이라고 알려져 있습니다.잠복감염의 약 10%가 활성질환으로 진행되며,[1] 이를 치료하지 않으면 감염자의 절반가량이 사망한다.활동성 결핵의 대표적인 증상은 혈액이 함유된 점액과 함께 만성 기침, 발열, 식은땀, 체중 [1]감소입니다.그것은 역사적으로 [8]질병과 관련된 체중 감소 때문에 소비라고 불렸다.다른 장기의 감염은 다양한 [9]증상을 일으킬 수 있다.

결핵은 폐에 활동성 결핵이 있는 사람들이 기침, 침 뱉기, 말하거나 [1][10]재채기를 할 때 공기를 통해 한 사람에서 다른 사람으로 전파된다.잠복결핵이 있는 사람들은 그 [1]병을 퍼뜨리지 않는다.활성 감염은 HIV/AIDS 환자나 [1]흡연자에게서 더 자주 발생합니다.활성 TB의 진단은 흉부 X-ray, 현미경 검사 및 체액 [11]배양에 기초한다.잠복결핵의 진단은 투베르쿨린 피부검사([11]TST) 또는 혈액검사에 의존합니다.

결핵 예방은 고위험군 선별, 환자 조기 발견 및 치료, BCG([3][4][5]Bacillus Calmette-Guérin) 백신 접종을 포함한다.고위험군에는 활동성 [4]결핵 환자의 가정, 직장 및 사회적 접촉이 포함된다.치료를 위해서는 장기간에 [1]걸쳐 여러 항생제를 사용해야 한다.항생제 내성은 다제내성결핵(MDR-TB)[1] 발생률이 증가함에 따라 증가하는 문제이다.

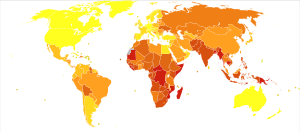

2018년에는 전 세계 인구의 4분의 1이 [6]결핵에 감염된 것으로 생각되었다.매년 [12]인구의 약 1%에서 새로운 감염이 발생한다.2020년에는 약 1천만 명이 활동성 결핵에 걸려 150만 명이 사망했으며, 이는 COVID-19에 이어 [13]감염성 질환으로 인한 두 번째 주요 사망 원인이 되었다.2018년 현재 대부분의 결핵 환자는 동남아시아 지역(44%), 아프리카 지역(24%), 서태평양 지역(18%)에서 발생했으며, 50% 이상이 8개국에서 진단되고 있다.이어 인도(27%), 중국(9%), 인도네시아(8%), 필리핀(6%), 파키스탄(6%), 나이지리아(4%), 방글라데시(4%)[14] 순이었다.2021년까지 매년 신규 발생 건수는 [13][1]약 2%씩 감소했습니다.많은 아시아와 아프리카 국가의 약 80%가 양성 반응을 보이는 반면, 미국 인구의 5~10%는 투베르쿨린 검사를 [15]통해 양성 반응을 보인다.결핵은 [16]고대부터 인간에게 존재해 왔다.

징후 및 증상

결핵은 신체의 모든 부분을 감염시킬 수 있지만, 가장 일반적으로 폐에서 발생한다.[9]폐외결핵은 폐외에서 결핵이 발병할 때 발생하지만 폐외결핵은 폐외결핵과 [9]공존할 수 있다.

일반적인 증상과 증상으로는 발열, 오한, 식은땀, 식욕부진, 체중감소, [9]피로 등이 있습니다.또한 상당한 네일 클럽이 발생할 [18]수 있습니다.

폐활량

결핵 감염이 활성화되면, 가장 일반적으로 폐와 관련이 있습니다(경우의 [16][19]약 90%).증상으로는 가슴 통증과 가래를 생성하는 장기 기침을 포함할 수 있다.약 25%의 사람들이 아무런 증상이 없을 수 있다(즉,[16] 그들은 무증상으로 남아 있다).때때로 사람들은 적은 양의 피를 토할 수 있고, 매우 드문 경우, 감염이 폐동맥이나 라스무센의 동맥류로 침식되어 대량 [9][20]출혈을 일으킬 수 있다.결핵은 만성 질환이 되어 폐 상엽에 광범위한 흉터를 일으킬 수 있다.위 폐엽은 아래 [9]폐엽보다 결핵에 더 자주 걸린다.이 차이의 이유는 [15]명확하지 않다.공기 흐름이 [15]좋거나 폐 [9]상부의 림프 배수가 잘 되지 않기 때문일 수 있습니다.

폐외

활성 환자의 15-20%에서 감염은 폐 밖으로 퍼져 다른 종류의 [21]결핵을 일으킨다.이것들은 총칭해서 폐외결핵으로 [22]표기된다.폐외결핵은 면역력이 약해진 사람들과 어린 아이들에게서 더 흔하게 발생한다.HIV에 감염된 사람의 경우 50% 이상의 [22]사례에서 발생합니다.주목할 만한 폐외 감염 부위로는 늑막(결핵성 늑막염), 중추신경계(결핵성 뇌수막염), 림프계(목의 음낭), 생식기관계(요로겐성 결핵), 뼈와 관절(척추의 포트병) 등이 있다.잠재적으로 더 심각하고 널리 퍼진 결핵의 형태는 "분산 결핵"[9]이라고 불리며, 또한 이것은 또한 밀리어 결핵이라고도 알려져 있습니다.밀리어리 결핵은 현재 폐외환자의 [23]약 10%를 차지한다.

원인들

마이코박테리아

결핵의 주요 원인은 미코박테륨 결핵인데, 이것은 작고, 호기성,[9] 운동성이 없는 세균이다.이 병원체의 높은 지질 함량은 독특한 임상적 [24]특징의 많은 부분을 설명한다.이것은 보통 [25]1시간 이내에 분열하는 다른 박테리아에 비해 매우 느린 속도로 16시간에서 20시간마다 분열한다.마이코박테리아는 외막 지질 이중층을 [26]가지고 있다.그램 염색 시 MTB는 세포벽의 [27]지질 및 마이콜산 함량이 높기 때문에 매우 약한 "그램 양성"으로 염색하거나 염료를 보유하지 않습니다.MTB는 약한 소독제에 견딜 수 있고 건조한 상태에서 몇 주 동안 생존할 수 있습니다.자연계에서는 숙주의 세포 내에서만 증식할 수 있지만 결핵균은 [28]실험실에서 배양할 수 있다.

가래에서 나온 예상 샘플의 조직학적 얼룩을 이용하여, 과학자들은 현미경으로 MTB를 확인할 수 있다.MTB는 산성용액으로 처리해도 얼룩이 남아있어 내산성균으로 [15][27]분류된다.가장 일반적인 내산성 염색 기술은 질-닐센[29] 염색과 킨윤 염색으로, 내산성 바실리를 파란색 [30]바탕에 뚜렷이 보이는 밝은 빨간색으로 염색합니다.오라민로다민염색[31], 형광현미경법도[32] 이용된다.

결핵균 복합체(MTBC)에는 결핵을 일으키는 마이코박테리아(M. bovis, M. africanum, M. canetti, M. microti)[33]가 포함되어 있습니다.M. africanum은 널리 퍼지지 않지만,[34][35] 아프리카 일부 지역에서 결핵의 중요한 원인이다.M. bovis는 한때 결핵의 흔한 원인이었지만 저온 살균 우유의 도입으로 [15][36]선진국에서의 공중 보건 문제로서 이것을 거의 없앴다.M. canetti는 희귀하고 아프리카의 뿔에 국한된 것으로 보이지만, 아프리카 [37][38]이민자들에게서 몇 가지 사례가 목격되었다.M. microti는 또한 희귀하고 면역 결핍자에게만 나타나지만, 그 유병률은 상당히 [39]과소평가될 수 있다.

다른 알려진 병원성 마이코박테리아로는 M. 나프래, M. Avium, M. cansasi 등이 있다.후자의 2종은 비결핵 마이코박테리아(NTM) 또는 비정형 마이코박테리아로 분류된다.NTM은 결핵도 나병도 일으키지 않지만 [40]결핵과 비슷한 폐질환을 일으킨다.

전송

활동성 폐결핵이 있는 사람들이 기침, 재채기, 말하기, 노래하기, 또는 침을 뱉을 때, 그들은 직경 0.5에서 5.0 µm의 전염성 에어로졸 방울을 배출한다.한 번의 재채기는 40,000개의 [41]물방울을 방출할 수 있습니다.결핵의 감염량이 매우 적기 때문에 이 방울들 각각은 [42]질병을 전염시킬 수 있다.

전염의 위험

결핵환자와 장기간, 빈번히, 또는 밀접하게 접촉하는 사람은 감염될 위험이 특히 높아 감염률이 22%[43]로 추정됩니다.활동적이지만 치료되지 않은 결핵에 걸린 사람은 연간 [44]10-15명 이상의 다른 사람들을 감염시킬 수 있다.전염은 활동성 결핵에 걸린 사람에서만 일어나야 합니다.잠복 감염자는 [15]전염성이 없는 것으로 생각됩니다.한 사람에서 다른 사람으로 전염될 확률은 보균자에 의해 배출되는 감염 비말의 수, 환기 효과, 노출 기간, M. 결핵 균주의 독성, 감염되지 않은 사람의 면역 수준 등을 포함한 [45]여러 요인에 따라 달라집니다.사람 대 사람 확산의 캐스케이드는 활성("오버트") TB를 가진 사람들을 분리하여 항결핵 약물 요법을 시행함으로써 막을 수 있다.효과적인 치료 후, 저항력이 없는 활성 감염 환자는 일반적으로 [43]다른 사람들에게 전염되지 않습니다.만약 누군가가 감염된다면, 새로 감염된 사람이 다른 [46]사람에게 전염될 만큼 충분히 감염되기까지 보통 3~4주가 걸린다.

위험요소

많은 요인들이 개인을 결핵 감염 [47]및/또는 질병에 더 취약하게 만든다.

활성 질환 위험

전 세계적으로 활동성 결핵 발병의 가장 중요한 위험 요인은 동시 HIV 감염입니다. 결핵 환자의 13%도 HIV에 [48]감염되어 있습니다.이것은 HIV 감염률이 [49][50]높은 사하라 사막 이남의 아프리카에서는 특히 문제가 되고 있습니다.결핵에 감염된 HIV 감염자가 아닌 사람 중 약 5~10%가 [18]평생 활동성 질환에 걸리고, 반대로 HIV와 함께 감염된 사람 중 30%가 [18]활동성 질환에 걸린다.

코르티코스테로이드 및 인플릭스맵(항α)과 같은 특정 약물의 사용TNF 모노클로널 항체)는 특히 선진국에서 [16]또 다른 중요한 위험 요소이다.

다른 위험 요인:alcoholism,[16]당뇨병을 포함한다 진성(3-fold 위험을 증가시켜)[51]규폐증(는 30배 위험성을 증대시켰다)[52]흡연(2-fold 위험성을 증대시켰다)[53]실내 공기 오염, 영양 실조, 젊은 age,[47]최근 취득한 결핵 감염, 기분 전환용 마약 사용, 심각한 신장 질환, 낮은 체중, 장기 이식, 머리와 n.eck cancer,[54]과 유전자틱 감수성[55](유전자 위험 인자의 전반적인 중요성은 정의되지 않은 상태로[16] 유지됨).

감염에 대한 민감성

흡연은 감염의 위험을 증가시킨다.감염 민감성을 증가시키는 추가적인 요인에는 어린 [47]나이가 포함된다.

병인 발생

M. 결핵에 감염된 사람들의 약 90%는 무증상 잠복 결핵 감염(LTBI라고도 함)[57]을 가지고 있으며, 잠복 감염이 명백한 활동성 결핵 [58]질환으로 진행될 확률은 10%에 불과하다.HIV에 감염된 사람의 경우 활성 결핵에 걸릴 위험이 [58]연간 10% 가까이 증가합니다.효과적인 치료가 이루어지지 않으면 활성 결핵 환자의 사망률은 최대 66%[44]에 달합니다.

결핵 감염은 마이코박테리아가 폐포 기낭에 도달하여 폐포 대식세포의 [15][59][60]내분비체 내에 침입하여 복제될 때 시작된다.대식세포는 그 박테리아가 외래 박테리아임을 확인하고 식세포증(phagocytosis)으로 제거하려고 시도한다.이 과정 동안, 박테리아는 대식세포에 둘러싸여 파고솜이라고 불리는 막으로 묶인 소포에 일시적으로 저장된다.그리고 나서 파고솜은 리소좀과 결합하여 파고이소좀을 만든다.파골리소좀에서, 세포는 박테리아를 죽이기 위해 활성산소와 산을 사용하려고 시도한다.하지만, 결핵은 이러한 독성 물질로부터 자신을 보호하는 두껍고 왁스 같은 미콜산 캡슐을 가지고 있다.M. 결핵은 대식세포 내에서 번식할 수 있고 결국 면역세포를 죽일 것이다.

Ghon 포커스라고 알려진 폐의 1차 감염 부위는 일반적으로 하엽의 상부 또는 [15]상엽의 하부 중 하나에 위치합니다.폐결핵은 혈류로부터의 감염을 통해서도 발생할 수 있다.이것은 Simon 포커스로 알려져 있으며 일반적으로 [61]폐의 상부에 있습니다.이 혈액형 전염은 말초 림프절, 신장, 뇌, 그리고 [15][62]뼈와 같은 더 먼 곳으로 감염을 확산시킬 수 있습니다.알려지지 않은 이유로 심장, 골격근육, 췌장,[63] 갑상선에 거의 영향을 주지 않지만 신체의 모든 부분이 이 병에 걸릴 수 있다.

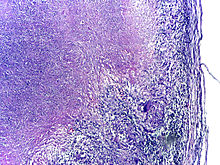

결핵은 육아종 염증 질환 중 하나로 분류된다.대식세포, 상피세포, T림프구, B림프구 및 섬유아세포가 모여 육아종을 형성하고, 감염된 대식세포를 둘러싼 림프구가 있다.다른 대식세포가 감염된 대식세포를 공격할 때, 그것들은 함께 융합되어 폐포 내강에서 거대한 다핵세포를 형성한다.육아종은 마이코박테리아 전파를 막고 면역체계의 [64]세포 상호작용을 위한 국소적인 환경을 제공할 수 있다.하지만, 더 최근의 증거는 박테리아가 숙주의 면역 체계에 의한 파괴를 피하기 위해 육아종을 사용한다는 것을 암시한다.육아종의 대식세포와 수지상세포는 림프구에 항원을 제시할 수 없기 때문에 면역반응이 [65]억제된다.육아종 내 세균은 잠복 감염을 일으킬 수 있다.육아종의 또 다른 특징은 결절의 중심에 비정상적인 세포사(괴사)가 생기는 것이다.육안으로는 부드럽고 하얀 치즈의 질감을 가지고 있으며 케이스성 [64]괴사라고 불립니다.

만약 결핵 박테리아가 손상된 조직 부위에서 혈류로 유입된다면, 그들은 몸 전체로 퍼질 수 있고 많은 감염을 일으킬 수 있으며,[66] 모두 조직에 작고 하얀 결절처럼 보입니다.어린 아이들과 HIV에 걸린 사람들에게서 가장 흔하게 나타나는 이 심각한 형태의 결핵은 밀리어 [67]결핵이라고 불립니다.이 파종성 결핵에 걸린 사람들은 치료를 받아도 높은 치사율을 보인다(약 30%).[23][68]

많은 사람들이 감염이 잦아들었다가 잦아들었다.조직 파괴와 괴사는 종종 치유와 [64]섬유화에 의해 균형을 이룬다.감염된 조직은 흉터와 케이스형 괴사물질로 채워진 충치로 대체된다.활동적인 질병 동안, 이러한 충치들 중 일부는 공기 통로 (브론치)에 결합되고 이 물질은 기침을 할 수 있습니다.그것은 살아있는 박테리아를 포함하고 있기 때문에 감염을 확산시킬 수 있다.적절한 항생제로 치료하면 박테리아가 죽어서 치유될 수 있습니다.치료 후, 환부는 결국 흉터 [64]조직으로 대체된다.

진단.

활동성 결핵

징후와 증상만 보고 활동성 결핵을 진단하는 것은 어렵고 [70]면역력이 약한 사람에게서 질병을 진단하는 것도 어렵다.[69]그러나 폐질환의 징후나 체질 증상이 [70]2주 이상 지속되는 경우에는 결핵 진단을 고려해야 한다.일반적으로 흉부 X선과 산속 세균에 대한 여러 가래 배양은 초기 [70]평가의 일부입니다.대부분의 개발도상국에서는 [71][72]간섭물질 방출 검사와 투베르쿨린 피부 테스트가 거의 사용되지 않습니다.IGRA(Interferon Gamma Release assay)[72][73]는 HIV에 감염된 사람들에게서 유사한 제한이 있다.

TB의 최종 진단은 임상 샘플(예: 가래, 고름 또는 조직 생검)에서 M. 결핵을 식별하여 이루어집니다.하지만, 이 천천히 성장하는 유기체의 어려운 배양 과정은 혈액이나 가래 [74]배양에 2주에서 6주가 걸릴 수 있습니다.그러므로, 치료는 종종 문화가 [75]확인되기 전에 시작된다.

핵산 증폭 테스트 및 아데노신 탈아미나아제 테스트를 통해 [69]TB를 신속하게 진단할 수 있습니다.항체를 검출하기 위한 혈액 검사는 특이하거나 민감하지 않기 때문에 [76]권장하지 않습니다.

잠복결핵

만톡스 투베르쿨린 피부 검사는 [70]결핵에 걸릴 위험이 높은 사람들을 검사하는 데 종종 사용된다.이전에 Bacille Calmette-Guerin 백신을 접종한 사람은 거짓 양성 반응이 [77]나올 수 있습니다.그 검사는 육종, 호지킨 림프종, 영양실조, 그리고 가장 주목할 만한 활동성 [15]결핵을 가진 사람들에게 거짓으로 음성일 수 있다.혈액 샘플에 대한 간섭 감마 방출 분석은 만두 [75]검사에 양성 반응을 보이는 사람들에게 권장됩니다.이것들은 면역이나 대부분의 환경 마이코박테리아에 영향을 받지 않기 때문에 거짓 양성 결과를 [78]적게 발생시킨다.그러나 그들은 M. szulgai, M. marinum, M. cansasii의 영향을 [79]받는다.IGRA는 피부 테스트와 함께 사용할 경우 민감도를 높일 수 있지만 단독으로 [80]사용할 경우 피부 테스트보다 민감도가 낮을 수 있습니다.

미국 예방 서비스 태스크 포스(USPSTF)는 잠복결핵 위험이 높은 사람들을 투베르쿨린 피부 검사 또는 간섭 감마 방출 검사를 [81]통해 선별할 것을 권고했다.일부에서는 의료 종사자 검사를 권고하고 있지만,[82] 2019년 현재[update] 이에 대한 혜택의 증거는 빈약하다.질병통제예방센터는 [83]2019년에 알려지지 않은 노출을 가진 의료 종사자에 대한 연간 검사 권고를 중단했다.

예방

결핵 예방과 통제 노력은 주로 영유아의 예방접종과 활성 [16]환자의 발견과 적절한 치료에 달려 있다.세계보건기구(WHO)는 치료 요법을 개선하고 환자 수를 [16]약간 줄임으로써 어느 정도 성공을 거두었다.일부 국가는 결핵 의심자를 비자발적으로 구금 또는 검사하거나 [84]감염되면 비자발적으로 치료하는 법을 가지고 있다.

백신

2021년 현재[update] 사용 가능한 백신은 BCG([85][86]Bacillus Calmette-Guérin)뿐이다.어린이에서 그것은 감염에 걸릴 위험을 20%까지 낮추고 감염이 활성 질병으로 변할 위험을 거의 60%[87]까지 감소시킨다.

그것은 전 세계적으로 가장 널리 사용되는 백신으로, 전체 어린이 중 90% 이상이 [16]예방접종을 받고 있다.그것이 유도하는 면역력은 약 10년 [16]후에 감소한다.결핵은 캐나다, 서유럽, 미국에서 흔치 않기 때문에 BCG는 [88][89][90]고위험자에게만 투여된다.백신 사용에 반대하는 이유 중 하나는 투베르쿨린 피부 테스트가 거짓 양성 반응을 일으켜 검사 [90]도구로서의 유용성을 떨어뜨린다는 것이다.몇 가지 백신이 [16]개발되고 있다.

BCG 주사 외에 피내 MVA85A 백신은 결핵 [91]예방에 효과가 없습니다.

공중 보건

1800년대 동안 과밀, 공공 침 뱉기, 정기적인 위생(손 씻기 포함)에 초점을 맞춘 공중 보건 캠페인은 접촉 추적, 격리 및 치료와 함께 결핵 및 기타 공기 질환의 전염을 극적으로 억제하는 데 도움이 되는 것을 방해하거나 느리게 확산시키는 데 도움을 주었다.대부분의 [92][93]선진국에서 주요 공중 보건 문제로서 결핵을 없애는 데 도움을 주었다.영양실조 등 결핵 확산을 악화시킨 다른 위험 요소들도 개선되었지만, HIV의 출현 이후, 결핵에 감염될 수 있는 면역 약자의 새로운 집단이 제공되었다.

세계보건기구(WHO)는 1993년 [16]결핵을 '글로벌 보건 비상사태'로 선포했고, 2006년 결핵방지 파트너십(Stop TB Partnership)은 출범 이후 [94]2015년까지 1400만 명의 생명을 구하는 것을 목표로 한 결핵을 막는 글로벌 계획을 수립했다.HIV 관련 결핵의 증가와 다제내성 [16]결핵의 출현으로 2015년까지 달성되지 못한 목표도 다수 있다.미국흉부학회에 의해 개발된 결핵 분류 시스템은 주로 공중 보건 [95]프로그램에 사용된다.2015년, 2035년 이전에 사망률을 95% 줄이고 발병률을 90% 감소시키기 위한 End TB 전략을 시작했습니다.결핵 퇴치의 목표는 신속한 검사, 짧고 효과적인 치료 과정, 그리고 완전히 효과적인 [96]백신의 부족으로 인해 방해받고 있다.

MDR-TB에 노출된 사람들에게 항결핵제를 투여하는 것의 유익성과 위해성은 [97]명확하지 않다.HIV 양성자가 HAART 치료를 이용할 수 있도록 하는 것은 활성 결핵 감염으로 진행될 위험을 최대 90%까지 크게 줄이고 이 모집단을 [98]통한 확산을 완화할 수 있다.

★★

결핵 치료는 항생제를 사용하여 박테리아를 죽인다.효과적인 결핵 치료는 약물의 진입을 방해하고 많은 항생제를 [99]무효로 만드는 마이코박테리아 세포벽의 특이한 구조와 화학적 구성 때문에 어렵습니다.

활성 결핵은 박테리아가 항생제 [16]내성을 일으킬 위험을 줄이기 위해 여러 항생제를 조합하여 가장 잘 치료된다.결핵에 걸린 HIV 양성 환자에게 리팜피신 대신 리파부틴을 일상적으로 사용하는 것은 2007년 [100]현재로선[update] 불명확한 혜택이다.

TB † TB

잠복결핵은 이소니아지드 또는 리팜핀 단독으로 또는 리팜피신 또는 리팜펜틴과 [101][102][103]이소니아지드의 조합으로 치료된다.

치료는 [45][101][104][103]약물에 따라 3개월에서 9개월 정도 걸립니다.잠복성 감염자는 [105]후년에 활동성 결핵 질환으로 진행되는 것을 방지하기 위해 치료를 받는다.

교육이나 상담은 잠복 결핵 치료의 [106]완료율을 향상시킬 수 있다.

2010년 현재[update] 신종 폐결핵의 권장 치료법은 리팜피신, 이소니아지드, 피라진아미드 및 에탐부톨을 포함한 항생제 조합의 6개월이며, 마지막 4개월은 [16]리팜피신과 이소니아지드만 있다.이소니아지드에 대한 내성이 높은 경우에는 [16]에탐부톨을 대체품으로 지난 4개월간 첨가해도 된다.6개월 이상 항결핵제로 치료하면 차이가 작더라도 6개월 미만 치료와 비교할 때 성공률이 높아집니다.준수 문제가 [107]있는 사람들에게는 더 짧은 치료법이 권장될 수 있습니다.또한 6개월 치료법에 [108]비해 짧은 항결핵 치료법을 지지한다는 증거는 없다.하지만 최근, 국제적인, 한, 통제 임상 실험에서 결과는 4개월간 매일 치료 요법을 포함하는, 또는"최적화,"moxifloxacin(2PHZM/2PHM)과rifapentine고 효과적은 기존의 표준 6개월의 식이 요법으로drug-susceptible 결핵(결핵)질병 치료에서 안전하다high-dose을 나타낸다.[109]

결핵이 재발하면 치료를 [16]결정하기 전에 어떤 항생제에 민감한지 검사하는 것이 중요하다.다제내성 TB(MDR-TB)가 검출되면 18~24개월 동안 최소 4가지 유효 항생제를 사용한 치료가 [16]권장된다.

세계보건기구(WHO)는 항생제를 [110]적절하게 복용하지 않는 사람의 수를 줄이기 위해 의료 제공자가 자신의 약물을 복용하는 것을 관찰하는 것과 같은 직접 관찰 치료법을 권고한다.단순히 독립적으로 약을 복용하는 사람들에 대한 이러한 관행을 뒷받침하는 증거는 [111]질이 떨어진다.직접 관찰된 치료가 완치된 사람들의 수나 그들의 [111]약을 완성한 사람들의 수를 향상시킨다는 것을 나타내는 강력한 증거는 없다.적당한 품질 증거는 사람들이 집에서와 진료소에서 관찰되거나 가족 대 의료 [111]종사자에 의해 관찰되는 경우에도 차이가 없음을 시사한다.치료와 예약의 중요성을 사람들에게 상기시키는 방법은 작지만 중요한 [112]개선으로 이어질 수 있습니다.또한 일주일에 2~3회 리팜피신이 포함된 간헐적 치료를 뒷받침할 충분한 증거가 없다. 치료율을 개선하고 재발률을 [113]감소시키는 일일 용량 요법과 동일한 효과를 가지고 있기 때문이다.또한 [114]결핵환자를 치료할 때 매일 복용하는 요법에 비해 매주 2회 또는 3회씩 간헐적인 단기 코스 요법의 효과에 대한 충분한 증거가 없다.

1차 내성은 내성 결핵균에 감염되었을 때 발생한다.완전 감수성 MTB를 가진 사람은 치료 중 부적절한 치료, 규정 준수 부족 또는 질 낮은 [115]약물 사용으로 인해 2차(취득) 내성이 생길 수 있습니다.약물 내성 결핵은 치료가 더 길고 더 비싼 약이 필요하기 때문에 많은 개발도상국에서 심각한 공중 보건 문제입니다.MDR-TB는 리팜피신과 이소니아지드 두 가지 가장 효과적인 첫 번째 결핵 약물에 대한 저항성으로 정의된다.광범위하게 약물에 내성이 있는 결핵은 또한 두 번째 약물의 6가지 [116]등급 중 3가지 이상에 내성이 있다.완전히 약물에 내성이 있는 결핵은 현재 사용되는 모든 [117]약물에 내성이 있다.2003년 이탈리아에서 [118]처음 발견됐지만 [117][119]2012년까지는 널리 보고되지 않았으며 이란과 [120]인도에서도 발견됐다.리네졸리드는 XDR-TB 환자를 치료하는 데 어느 정도 효과가 있지만 부작용과 약물 복용 중단이 [121][122]흔했다.베다킬린은 여러 약물에 내성이 있는 [123]TB에서 사용할 수 있도록 잠정적으로 지지된다.

XDR-TB는 광범위하게 내성이 있는 TB를 정의하는 데 사용되는 용어로 MDR-TB의 10가지 경우 중 1가지를 구성합니다.XDR TB 사례는 90% 이상의 [120]국가에서 확인되었습니다.

리팜피신 또는 MDR-TB가 알려진 환자의 경우 Genotype® MTBDRSl 검사(배양 분리 또는 도말 양성 검체에 수행됨)와 같은 분자 테스트가 2차 항혈관계 약물 [124][125]내성을 검출하는 데 유용할 수 있습니다.

★★★

결핵 감염에서 명백한 결핵 질환으로의 진행은 세균이 면역 체계 방어 체계를 극복하고 증식하기 시작할 때 일어난다.1차 결핵 질환(경우 중 약 1~5%)의 경우, [15]초기 감염 직후에 발생합니다.그러나 대부분의 경우 뚜렷한 [15]증상 없이 잠복 감염이 발생합니다.이러한 휴면 세균은 이러한 잠복 사례의 5~10%에서 활동적인 결핵을 발생시키며,[18] 종종 감염 후 수년 후에 발생한다.

HIV 감염 등에 의한 면역 억제와 함께 재활성화 위험이 높아집니다.결핵과 HIV에 감염된 사람들의 경우,[15] 재활성화 위험은 매년 10%까지 증가한다.M. 결핵 균주의 DNA 지문을 사용한 연구는 재감염이 이전에 [127]생각했던 것보다 재발성 결핵에 실질적으로 더 많이 기여하는 것으로 나타났으며,[128] 결핵이 흔한 지역에서 재활성화된 사례의 50% 이상을 차지할 수 있다고 추정했다.결핵으로 사망할 확률은 2008년 현재[update] [16]약 4%로 1995년의 8%보다 낮아졌다.

도말 양성 폐결핵 환자(HIV 공동 감염 없음)는 치료 없이 5년 후 50~60%가 사망하는 반면 20~25%는 자연 치유(치료)를 달성한다.결핵은 거의 항상 HIV 공동 감염을 치료하지 않은 사람들에게 치명적이며 HIV의 [129]항레트로바이러스 치료에도 불구하고 사망률이 증가한다.

★★

전 세계 인구의 약 4분의 1이 결핵에 [6]감염되어 있으며,[12] 매년 인구의 약 1%에서 새로운 감염이 발생하고 있습니다.그러나, 대부분의 결핵 감염은 질병을 [130]유발하지 않으며, 감염의 90-95%는 증상이 [57]없는 상태로 남아 있다.2012년에는 약 860만 명의 만성 환자가 활동하였다.[131]2010년에는 880만 명의 새로운 결핵 환자가 진단되었고 120만-145만 명의 사망자가 발생했다(대부분 개발도상국에서 [48][132]발생).이 중 약 35만 명이 HIV에 [133]감염된 사람들에게서 발생한다.2018년, 결핵은 단일 감염원에 [134]의한 전 세계 사망 원인 1위였다.총 결핵 환자 수는 2005년 이후 감소해 온 반면,[48] 새로운 환자 수는 2002년 이후 감소해 왔다.

결핵은 계절에 따라 발생하며 매년 봄과 여름에 [135][136][137][138]최고조에 달합니다.이것의 이유는 불분명하지만,[138][139] 겨울 동안의 비타민 D 결핍과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.또한 결핵을 저온, 저습도, 저우량 등 다양한 기상 조건과 연관짓는 연구도 있다.결핵 발병률이 기후 [140]변화와 관련이 있을 수 있다는 주장이 제기되어 왔다.

결핵은 인구과밀과 영양실조와 밀접하게 연관되어 있어 빈곤의 주요 [16]질병 중 하나이다.따라서 고위험군에는 불법 마약을 주사하는 사람, 취약한 사람들이 모이는 지역(예: 교도소 및 노숙자 쉼터), 의료 소외계층 및 자원 부족 지역, 고위험 인종 소수자, 고위험 범주 환자와 밀접하게 접촉하는 어린이, 의료 서비스 제공자가 포함된다.이 [141]환자들에게요

결핵의 발병률은 연령에 따라 다르다.아프리카에서는 주로 청소년과 [142]청소년에게 영향을 미친다.그러나 발병률이 급격히 감소한 국가(미국 등)에서 결핵은 주로 노인과 면역력이 저하된 질병이다(위 위험 요인은 위에 [15][143]열거되어 있다).전 세계적으로 22개의 "고부담" 주 또는 국가가 모두 80%의 환자 및 83%의 [120]사망률을 경험하고 있습니다.

캐나다와 호주에서 결핵은 원주민들, 특히 외딴 지역에서 [144][145]몇 배 더 흔하다.이에 기여하는 요인으로는 건강 상태와 행동을 유발하는 경향의 높은 유병률, 과밀과 빈곤이 포함된다.일부 캐나다 원주민 집단에서는 유전적 감수성이 [47]한 역할을 할 수 있다.

사회경제적 지위(SES)는 결핵 위험에 크게 영향을 미친다.SES가 낮은 사람들은 결핵에 걸릴 가능성이 더 높고 그 질병에 의해 더 심각한 영향을 받는다.SES가 낮은 사람은 결핵 발병 위험 요인(예: 영양실조, 실내 공기오염, HIV 공동감염 등)의 영향을 받을 가능성이 높으며, 혼잡하고 환기가 잘 되지 않는 공간에 추가로 노출될 가능성이 높다.불충분한 건강관리는 또한 확산을 촉진하는 활동적인 질병을 가진 사람들이 신속하게 진단되고 치료되지 않는다는 것을 의미한다. 따라서 아픈 사람들은 감염 상태를 유지하고 (계속)[47] 감염을 확산시킨다.

결핵의 분포는 전 세계적으로 균일하지 않다. 많은 아프리카, 카리브해, 남아시아, 동유럽 국가의 인구의 약 80%가 결핵 테스트에서 양성 반응을 보이는 반면, 미국 인구의 5~10%만이 [15]양성 반응을 보인다.효과적인 백신의 개발의 어려움, 비싸고 시간이 걸리는 진단 과정, 수개월의 치료의 필요성, HIV 관련 결핵의 증가, 그리고 미국에서의 약물 내성 사례의 출현을 포함한 많은 요인들 때문에 이 병을 완전히 통제하려는 희망은 극적으로 꺾였다.1980년대.[16]

선진국에서 결핵은 덜 흔하고 주로 도시 지역에서 발견됩니다.유럽에서는 결핵으로 인한 사망자가 1850년 10만 명 중 500명에서 1950년 10만 명 중 50명으로 줄었다.공중 보건의 향상은 항생제가 도착하기 전부터 결핵을 감소시키는 것이었지만, 이 질병은 공중 보건에 중대한 위협으로 남아 1913년 영국에서 의학 연구 위원회가 결성되었을 때 그것의 첫 번째 초점은 결핵 [146]연구였다.

2010년 세계 각지의 인구 10만 명당 비율은 전 세계 178명, 아프리카 332명, 미주 36명, 지중해 동부 173, 유럽 63, 동남아시아 278명, 서태평양 [133]139명 등이었다.

러시아는 1965년 10만명당 61.9명에서 1993년 [147][148]10만명당 2.7명으로 TB 사망률이 감소하면서 특히 큰 진전을 이뤘다. 그러나 사망률은 2005년 10만명당 24명으로 증가했고 [149]이후 2015년에는 10만명당 11명으로 후퇴했다.

★★★

중국은 1990년부터 [133]2010년 사이에 결핵 사망률이 약 80% 감소하는 등 특히 극적인 진전을 이루었다.2004년부터 [120]2014년까지 신규 발생 건수는 17% 감소했다.

2007년에 TB의 추정 발병률이 가장 높은 나라는 에스와티니로 인구 10만명당 1,200명이 발생했다.2017년 인구 대비 추정 발생률이 가장 높은 나라는 레소토로 인구 [150]10만명당 665명이었다.

★★★

2017년 현재, 인도가 [150]약 2,740,000명으로 가장 많은 총 발병률을 보였다.세계보건기구(WHO)에 따르면 2000-2015년 인도의 추정 사망률은 연간 인구 10만명당 55명에서 36명으로 감소했으며 [151][152]2015년에는 48만명으로 추산된다.인도에서는 결핵 환자의 대부분이 민간 파트너와 민간 병원에서 치료를 받고 있다.증거는 결핵 국가 조사가 인도의 [153]개인 클리닉과 병원에서 진단되고 기록된 환자 수를 나타내지 않는다는 것을 보여준다.

★★★

미국의 원주민들은 [154]결핵으로 인한 사망률이 5배 더 높으며, 보고된 모든 결핵 [155]사례의 84%를 소수 인종과 민족이 차지했다.

미국에서는 2017년 [150]전체 결핵 환자 수가 인구 10만명당 3명이었다.캐나다에서 결핵은 여전히 일부 시골 지역에서 [156]풍토병이다.

2017년 영국에서 국가 평균은 10만 명당 9명이었고 서유럽에서 가장 높은 발병률은 포르투갈에서 10만 명당 20명이었다.

★★★

결핵은 [16]고대부터 존재해 왔다.가장 오래된 M. 결핵은 약 17,000년 [159]전의 와이오밍의 들소 잔해에서 이 질병의 증거를 보여준다.그러나 결핵이 소에서 시작돼 사람에게 옮았는지, 소와 인간의 결핵이 공통의 조상으로부터 분리됐는지는 여전히 [160]불분명하다.인간의 결핵 복합체 유전자와 동물의 MTBC 유전자의 비교는 연구자들이 이전에 믿었던 것처럼 인간이 동물 사육 중에 동물로부터 MTBC를 얻지 않았다는 것을 암시한다.두 종류의 결핵균은 신석기 혁명 [161]이전에도 인간을 감염시켰을 수 있는 공통 조상을 갖고 있다.골격 유적은 일부 선사시대 인간(기원전 4000년)이 결핵에 걸렸다는 것을 보여주며,[162] 연구자들은 기원전 3000년에서 2400년까지 거슬러 올라가는 이집트 미라의 척추에서 결절성 부패를 발견했다.유전자 연구에 따르면 서기 [163]100년경부터 아메리카 대륙에 결핵이 존재한다고 한다.

산업 혁명 전에, 민간인들은 종종 결핵을 뱀파이어와 연관시켰다.가족 중 한 명이 이 질병으로 사망했을 때, 다른 감염된 사람들은 서서히 건강을 잃었습니다.사람들은 이것이 원래 결핵에 걸린 사람이 다른 [164]가족들로부터 생명을 빼앗아서 생긴 것이라고 믿었다.

리처드 모튼은 1689년에 [165][166]결절과 관련된 폐 형태를 병리학으로 확립했지만, 다양한 증상으로 인해 결핵은 1820년대까지 단일 질병으로 식별되지 않았다.벤자민 마틴은 1720년에 소비가 [167]서로 가까이 사는 사람들에 의해 퍼진 미생물에 의해 발생한다고 추측했다.1819년 르네 레넥은 결핵이 폐결핵의 [168]원인이라고 주장했다.J. L. Schönlein은 "결핵"이라는 이름을 처음 출판했다.1832년 투베르쿨로오스).[169][170]1838년부터 1845년까지 켄터키에 있는 매머드 동굴의 소유주인 존 크로건은 일정한 온도와 순수한 동굴 공기로 병을 치료하기 위해 결핵에 걸린 많은 사람들을 동굴로 데려왔다.; 각각은 [171]1년 안에 죽었다.헤르만 브레머는 1859년 실레지아의 [172]괴베르스도르프(현재의 소코와프스코)에 첫 결핵 요양원을 열었다.1865년 장 앙투안 빌민은 결핵이 접종을 통해 사람에게서 동물과 [173]동물 사이에 전염될 수 있다는 것을 증명했다. (빌민의 발견은 존 버든 샌더슨에 의해 1867년과 1868년에 확인되었다.)[174]

로버트 코흐는 1882년 [175][176]3월 24일 결핵을 일으키는 세균인 M. 결핵을 확인하고 기술했다.그는 이 [177]발견으로 1905년 노벨 생리의학상을 받았다.코흐는 소와 인간의 결핵 질환이 유사하다고 믿지 않았고 이로 인해 감염된 우유를 감염원으로 인식하는 것이 지연되었다.1900년대 전반에는 저온 살균 과정을 적용한 후 이 소스로부터의 전염 위험이 극적으로 감소했습니다.코흐는 1890년에 결핵의 "리메디"로서 결핵균의 글리세린 추출물을 "투베르쿨린"이라고 부르며 발표했다.효과는 없었지만, 나중에 증상전 [178]결핵의 존재에 대한 선별 검사로 성공적으로 적응되었다.세계 결핵의 날은 매년 3월 24일로 코흐의 원래 과학 발표 기념일이다.

Albert Calmette와 Camille Guérin은 1906년 약화된 소줄 결핵을 사용하여 결핵에 대한 예방접종을 최초로 성공시켰다.그것은 바실 칼메트 게린이라고 불렸다.BCG 백신은 1921년 [179]프랑스에서 인간에게 처음 사용되었지만, [180]2차 세계대전 후에야 미국, 영국, 독일에서 널리 받아들여졌다.

결핵은 도시 빈민들 사이에서 흔한 질병이 되면서 19세기와 20세기 초에 광범위한 대중의 우려를 불러일으켰다.1815년 영국에서 4명 중 1명은 "소비"로 인한 사망이었다.1918년까지 결핵은 여전히 프랑스에서 [citation needed]6명 중 1명의 사망자를 발생시켰다.결핵이 전염되는 것으로 결정된 후, 1880년대에 영국에서 그것은 알림 질환 목록에 올랐다; 사람들이 공공장소에서 침을 뱉는 것을 막기 위한 캠페인이 시작되었고, 감염된 가난한 사람들은 감옥을 닮은 요양원에 들어가도록 격려받았다.텐션)[172]"신선한 공기"와 요양원에서의 노동의 이점이 무엇이든 간에, 심지어 최상의 조건에서도, 5년 c.이내에 들어간 사람들 중 50%가 죽었다([172]1916년).1913년 영국에서 의학연구위원회가 결성되었을 때, 처음에는 [181]결핵 연구에 초점을 맞췄다.

유럽에서는 1600년대 초반부터 결핵 발병률이 최고조에 달하기 시작해 1800년대에 이르러 전체 [182]사망자의 25%에 육박했다.18, 19세기 유럽에서 결핵이 유행하면서 [183][184]계절적 패턴을 보였다.1950년대까지 유럽의 사망률은 [185]약 90% 감소했다.비록 질병이 심각한 위협으로 남아있지만, 위생,[185] 예방접종 및 기타 공중 보건 조치의 개선은 스트렙토마이신과 다른 항생제가 도착하기 전부터 결핵의 비율을 크게 감소시키기 시작했습니다.1946년 항생제 스트렙토마이신의 개발로 결핵의 효과적인 치료와 치료가 실현되었다.이 약이 도입되기 전에는 감염된 폐를 쓰러뜨려 "휴식"시키고 결핵 병변을 [186]치유하는 "기흉 기술"을 포함한 외과적 개입이 유일한 치료법이었다.

다제내성결핵(MDR-TB)의 출현으로 특정 결핵 감염 사례의 수술이 다시 도입되었다.이는 박테리아 수를 줄이고 혈류 [187]내 항생제에 대한 나머지 박테리아 노출을 증가시키기 위해 폐에 있는 감염된 흉강("bullae")을 제거하는 것을 포함합니다.결핵을 없애려는 희망은 1980년대 약물 내성 균주의 증가로 끝이 났다.이후 결핵이 재발하면서 1993년 [188]세계보건기구(WHO)가 세계 보건 비상사태를 선포했다.

사회와 문화

이름

결핵은 기술적인 것부터 익숙한 [189]것까지 많은 이름으로 알려져 왔다.Phthis는 폐결핵의 [8]옛 용어인 소비를 뜻하는 그리스어이다. 기원전 460년경 히포크라테스는 Phthis를 [190]건기의 질병으로 묘사했다.TB는 결핵균의 줄임말이다.소비는 그 병을 가리키는 가장 흔한 19세기 영어 단어였다.'완전'을 뜻하는 라틴어 루트 콘은 '아래에서 차지하다'[191]를 뜻하는 수미어와 연결되어 있다.저자는 존 번얀의 '배드먼 씨의 삶과 죽음'에서 폐병을 '이 [192]모든 죽음의 선장'이라고 부른다.[189]

미술과 문학

결핵은 수세기 동안 감염자들 사이에서 시적이고 예술적인 자질과 연관되어 있었으며, "낭만병"[189][193]으로도 알려져 있었다.시인 존 키츠, 퍼시 비시 셸리, 및 에드가 앨런 포우, 그 작곡가 프레데리크 Chopin,[194]에 극작가 안톤 체호프, 소설가 프란츠 카프카, 캐서린 Mansfield,[195]샬롯 브론테, 표도르 도스토예프스키, 토마스 만, W. 서머셋 Maugham,[196]조지 Orwell,[197]과 로버트 루이스 스티븐슨, 그리고 arti과 같은 주요 예술적 인물이다.sts 앨리스 Neel,[198]Jean-Antoine Watteau, Elizabeth Siddal, Marie Bashkirtseff, Edvard Munch, Oubrey Beardsley, Amedeo Modigliani는 이 병에 걸렸거나 감염된 사람들에게 둘러싸여 있었다.결핵이 예술적 재능을 돕는다는 믿음이 널리 퍼져 있었다.이 효과를 위해 제안된 물리적 메커니즘에는 미열과 독소혈증이 포함되어 있으며, 이는 그들이 삶을 더 명확하게 보고 [199][200][201]결정적으로 행동하도록 돕는 것으로 알려졌다.

결핵은 요양원을 [202]배경으로 한 토마스 만의 마법산처럼 문학에서 자주 재사용되는 주제를 형성했고, 밴 모리슨의 노래 "T.B."에서처럼 음악에서도 자주 재사용되는 주제를 형성했다. 시트'[203]는 오페라에서는 푸치니의 라보엠과 베르디의 라 [201]트라비아타에서, 예술에서는 모네의 첫 번째 아내 카밀의 임종 [204]때 그리고 영화에서는 1945년 세인트루이스의 종과 같이. 메리는 잉그리드 버그먼이 [205]결핵을 앓고 있는 수녀로 출연하고 있어요

공중 보건 활동

2014년에 WHO는 [206]2030년까지 결핵 발생률을 80% 줄이고 결핵 사망률을 90% 줄이는 것을 목표로 하는 "종말 TB" 전략을 채택했다.이 전략에는 [207]2020년까지 TB 발생률을 20%, TB 사망률을 35% 감소시키는 이정표가 포함되어 있습니다.그러나 2020년까지 전 세계적으로 인구당 발생률이 9% 감소하는 데 그쳤고, 유럽 지역은 19%, 아프리카 지역은 16% [207]감소하였다.마찬가지로 사망자 수는 14% 감소하는데 그쳐 2020년의 35% 감소라는 이정표를 놓쳤다. 일부 지역은 더 나은 진전(유럽 31%, 아프리카 [207]19%)을 보이고 있다.이에 대응하여 2020년에는 치료, 예방 및 자금 지원 마일스톤도 놓쳤다. 예를 들어, 목표치인 [207]3000만 명에 못 미치는 630만 명만이 결핵 예방을 시작했다.

세계보건기구(WHO), 빌과 멜린다 게이츠 재단, 그리고 미국 정부는 [208][209][210]2012년 현재 저소득층과 중산층 국가에서 사용하기 위해 빠르게 작동하는 결핵 진단 검사를 보조하고 있다.이 테스트는 빠르게 반응할 뿐만 아니라 항생제 리팜피신에 대한 내성이 있는지 여부를 판단할 수 있습니다.리팜피신은 다제내성 결핵을 나타낼 수 있으며 HIV에 [208][211]감염된 사람들에게도 정확합니다.2011년 현재[update] 자원이 부족한 많은 장소들은 가래 현미경 [212]검사만을 이용할 수 있다.

인도는 2010년에 전 세계에서 총 결핵 환자 수가 가장 많았는데, 부분적으로는 민간 및 공공 의료 부문의 [213]질병 관리 부실에 기인한다.개정된 국가 결핵 통제 프로그램과 같은 프로그램들은 공공 의료 서비스를 [214][215]받는 사람들의 결핵 수치를 줄이기 위해 노력하고 있다.

2014년 EIU-헬스케어 보고서에 따르면 무관심과 자금 지원 확대에 대한 충동에 대처할 필요가 있습니다.보고서는 루시카 디투이 "TB"는 고아와 같다고 인용하고 있다.부담이 큰 나라에서도 방치돼 기증자나 의료 [120]개입에 투자하는 사람들에게 잊혀지는 경우가 많습니다.

글로벌 에이즈, 결핵, 말라리아 퇴치를 위한 기금(Global Fund to Tweat AIDS, Tubercusic and Malaria)의 마크 다이불 집행이사는 "우리는 지구상에서 결핵을 대유행과 공중 보건 위협으로 끝낼 수 있는 도구를 가지고 있지만 우리는 그렇게 [120]하지 않고 있다"고 표현했다.몇몇 국제기구들은 치료의 투명성을 높이도록 촉구하고 있으며, 2014년부터 의무적으로 정부에 환자 보고를 시행하고 있는 국가들도 늘어나고 있다. 그러나 준수는 종종 가변적이지만 말이다.상업적 치료제 공급자는 보조 치료제뿐만 아니라 2차 약물을 과다 처방하여 추가적인 [120]규제에 대한 요구를 촉진할 수 있다.브라질 정부는 보편적 결핵 치료를 제공하고 있어 이 문제를 줄일 수 [120]있다.반대로 결핵 감염률 감소는 감염률 감소를 위한 프로그램의 수와 관련이 없을 수 있지만, [120]인구의 교육, 소득 및 건강 수준 증가와 관련이 있을 수 있다.2009년에 세계은행이 계산한 바와 같이, 이 질병의 비용은 "고부담"[120] 국가에서 연간 1,500억 달러를 초과할 수 있다.이 병을 근절하는 데 진전이 없는 것은 2억 5천만 명의 중국 [120]시골 이민자들 중처럼 인내심 있는 후속 조치가 부족하기 때문일 수도 있다.

능동적 접촉 추적이 결핵 [216]환자 발견률 향상에 도움이 된다는 것을 보여주는 데이터는 충분하지 않다.호별 방문, 교육 전단, 매스미디어 전략, 교육 세션과 같은 개입은 [217]결핵 발견률을 단기간에 높일 수 있다.소셜 네트워크 분석과 같은 새로운 컨택트레이스 방법과 기존의 컨택트레이스 [218]방법을 비교하는 연구는 없습니다.

★★★

그 질병을 예방하는 데 있어서 느린 진보는 부분적으로 [120]결핵과 관련된 낙인 때문일 수 있다.오명은 영향을 받은 사람들로부터의 전염에 대한 두려움 때문일 수 있다.이러한 오명은 결핵과 빈곤, 그리고 아프리카에서는 [120]에이즈 사이의 연관성 때문에 추가로 발생할 수 있다.그러한 오명은 현실적이고 인식될 수 있다. 예를 들어 가나에서는 결핵에 걸린 사람들이 공공 [219]모임에 참석하는 것이 금지된다.

결핵에 대한 낙인은 [120]치료의 지연, 치료 준수의 저하, 가족 구성원들의[219] 사망원인을 비밀로 하는 결과를 초래할 수 있어 질병이 더욱 [120]확산될 수 있습니다.이와는 대조적으로 러시아에서는 오명이 치료 [219]준수를 증가시키는 것과 관련이 있었다.결핵 오명은 또한 사회적으로 소외된 개인에게 더 큰 영향을 미치며 [219]지역마다 다르다.

오명을 줄이는 한 가지 방법은 감염된 사람들이 경험을 공유하고 지원을 제공할 수 있는 "TB 클럽"을 홍보하거나 [219]상담을 통해서일 수 있습니다.일부 연구는 결핵 교육 프로그램이 낙인 감소에 효과적이며, 따라서 치료 [219]고수를 증가시키는데 효과적일 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.그럼에도 불구하고, 2010년[update] 현재 낙인 감소와 사망률의 관계에 대한 연구는 부족하며, 에이즈를 둘러싼 낙인을 감소시키기 위한 유사한 노력은 최소한으로 효과가 [219]있었다.일부는 오명이 질병보다 더 나쁘다고 주장했으며, 결핵 환자는 종종 어렵거나 [120]바람직하지 않은 것으로 인식되기 때문에 의료 서비스 제공자는 의도하지 않게 오명을 강화할 수 있습니다.결핵의 사회적, 문화적 차원에 대한 더 많은 이해는 또한 오명을 줄이는 [220]데 도움이 될 수 있다.

BCG 백신은 한계가 있어 새로운 결핵 백신을 개발하기 위한 연구가 [221]진행 중이다.많은 잠재적 후보들이 현재 1단계와 2단계 임상시험 [221][222]중이다.이용 가능한 백신의 효능을 개선하기 위해 두 가지 주요 접근법이 사용된다.한 가지 접근법은 BCG에 서브유닛 백신을 추가하는 것이고, 다른 전략은 새롭고 더 나은 살아있는 [221]백신을 만드는 것이다.서브유닛 백신의 일례인 MVA85A는 2006년 현재 남아프리카공화국에서 시험 중이며 유전자 변형 [223]백신을 기반으로 한다.백신은 잠복병과 활성병 [224]치료에 중요한 역할을 할 것으로 기대된다.

더 많은 발견을 장려하기 위해 연구원들과 정책 입안자들은 2006년 현재 백신 개발의 새로운 경제 모델을 홍보하고 있다.상금, 세금 우대, 사전 시장 [225][226]약속 등이 그것이다.Stop TB Partnership,[227] 남아프리카 결핵 백신 이니셔티브 및 Aeras Global TB 백신 재단을 포함한 많은 그룹이 [228]연구에 참여하고 있습니다.이 중 Aeras Global TB Baccine Foundation은 Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation으로부터 2억8000만달러(미국) 이상의 기부금을 받아 고부하 [229][230]국가에서 사용할 수 있는 결핵 예방백신을 개발하고 허가했다.

2012년 현재 다제내성 결핵에 대해 베다킬린과 딜라미니드를 [231]포함한 많은 약물이 연구되고 있다.베다킬린은 2012년 [232]말에 미국 식품의약국(FDA)의 승인을 받았다.이러한 새로운 약물의 안전성과 효과는 2012년 현재 비교적 소규모의 연구 [231][233]결과에 기초하고 있기 때문에 불확실하다.그러나 기존 데이터는 환자들이 표준 결핵 치료 외에도 bedaquiline을 다섯번 죽을이 새로운 drug,[234]없이 의학적인 저널 기사들 왜 FDA과 이 회사에 금융 분야 관계를bedaquiline inf을 만드는 약을 승인하였다에 대해 보건 정책의 문제 제기에 초래하고 있는 것보다는 것으로 나타난다.luen그 [233][235]사용에 대한 의사의 지원.

스테로이드 추가 요법은 활발한 폐결핵 [236]감염에 어떤 이점도 보여주지 않았다.

기타 동물

마이코박테리아는 조류,[237] 물고기, 설치류,[238] [239]파충류를 포함한 많은 다른 동물들을 감염시킨다.그러나 결핵균 아종은 [240]야생동물에는 거의 존재하지 않는다.뉴질랜드의 소와 사슴 떼에서 마이코박테륨 보비스에 의한 소결핵을 근절하려는 노력은 비교적 [241]성공적이었다.영국에서의 노력은 [242][243]덜 성공적이었다.

2015년 현재[update], 결핵은 미국에서 포획된 코끼리들 사이에서 널리 퍼지고 있는 것으로 보인다.이 동물들은 원래 사람에게서 이 병을 얻었다고 믿어지는데, 이 과정은 역동물병이라고 불린다.이 질병은 사람과 다른 동물 모두를 감염시키기 위해 공기를 통해 퍼질 수 있기 때문에 서커스와 [244][245]동물원에 영향을 미치는 공중 보건 문제이다.

레퍼런스

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Tuberculosis (TB)". who.int. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Ferri FF (2010). Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. p. Chapter T. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ a b Hawn TR, Day TA, Scriba TJ, Hatherill M, Hanekom WA, Evans TG, et al. (December 2014). "Tuberculosis vaccines and prevention of infection". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 78 (4): 650–71. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00021-14. PMC 4248657. PMID 25428938.

- ^ a b c Implementing the WHO Stop TB Strategy: a handbook for national TB control programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). 2008. p. 179. ISBN 978-92-4-154667-6. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ a b Harris RE (2013). "Epidemiology of Tuberculosis". Epidemiology of chronic disease: global perspectives. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 682. ISBN 978-0-7637-8047-0.

- ^ a b c "Tuberculosis (TB)". World Health Organization (WHO). 16 February 2018. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Tuberculosis deaths rise for the first time in more than a decade due to the COVID-19 pandemic". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ a b The Chambers Dictionary. New Delhi: Allied Chambers India Ltd. 1998. p. 352. ISBN 978-81-86062-25-8. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Adkinson NF, Bennett JE, Douglas RG, Mandell GL (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. Chapter 250. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

- ^ "Basic TB Facts". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ a b Konstantinos A (2010). "Testing for tuberculosis". Australian Prescriber. 33 (1): 12–18. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2010.005.

- ^ a b "Tuberculosis". World Health Organization (WHO). 2002. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Tuberculosis (TB)". WHO. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Global tuberculosis report". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kumar V, Robbins SL (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1. OCLC 69672074.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Lawn SD, Zumla AI (July 2011). "Tuberculosis". Lancet. 378 (9785): 57–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3. PMID 21420161. S2CID 208791546. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Schiffman G (15 January 2009). "Tuberculosis Symptoms". eMedicine Health. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d Gibson PG, Abramson M, Wood-Baker R, Volmink J, Hensley M, Costabel U, eds. (2005). Evidence-Based Respiratory Medicine (1st ed.). BMJ Books. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-7279-1605-1. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ Behera D (2010). Textbook of Pulmonary Medicine (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 457. ISBN 978-81-8448-749-7. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Halezeroğlu S, Okur E (March 2014). "Thoracic surgery for haemoptysis in the context of tuberculosis: what is the best management approach?". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (3): 182–85. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.25. PMC 3949181. PMID 24624281.

- ^ Jindal SK, ed. (2011). Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 549. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ^ a b Golden MP, Vikram HR (November 2005). "Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview". American Family Physician. 72 (9): 1761–68. PMID 16300038.

- ^ a b Habermann TM, Ghosh A (2008). Mayo Clinic internal medicine: concise textbook. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. p. 789. ISBN 978-1-4200-6749-1. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Southwick F (2007). "Chapter 4: Pulmonary Infections". Infectious Diseases: A Clinical Short Course, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. pp. 104, 313–14. ISBN 978-0-07-147722-2.

- ^ Jindal SK (2011). Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 525. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H (March 2010). "Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins". Trends in Microbiology. 18 (3): 109–16. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005. PMC 2931330. PMID 20060722.

- ^ a b Madison BM (May 2001). "Application of stains in clinical microbiology". Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 76 (3): 119–25. doi:10.1080/714028138. PMID 11475314.

- ^ Parish T, Stoker NG (December 1999). "Mycobacteria: bugs and bugbears (two steps forward and one step back)". Molecular Biotechnology. 13 (3): 191–200. doi:10.1385/MB:13:3:191. PMID 10934532. S2CID 28960959. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Medical Laboratory Science: Theory and Practice. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. 2000. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-07-463223-9. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Acid-Fast Stain Protocols". 21 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Kommareddi S, Abramowsky CR, Swinehart GL, Hrabak L (November 1984). "Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: comparison of the fluorescent auramine-O and Ziehl-Neelsen techniques in tissue diagnosis". Human Pathology. 15 (11): 1085–9. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80253-1. PMID 6208117.

- ^ van Lettow M, Whalen C (2008). Semba RD, Bloem MW (eds.). Nutrition and health in developing countries (2nd ed.). Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-934115-24-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ van Soolingen D, Hoogenboezem T, de Haas PE, Hermans PW, Koedam MA, Teppema KS, et al. (October 1997). "A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an exceptional isolate from Africa". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 47 (4): 1236–45. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-4-1236. PMID 9336935.

- ^ Niemann S, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Joloba ML, Whalen CC, Guwatudde D, Ellner JJ, et al. (September 2002). "Mycobacterium africanum subtype II is associated with two distinct genotypes and is a major cause of human tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (9): 3398–405. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.9.3398-3405.2002. PMC 130701. PMID 12202584.

- ^ Niobe-Eyangoh SN, Kuaban C, Sorlin P, Cunin P, Thonnon J, Sola C, et al. (June 2003). "Genetic biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Cameroon". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 41 (6): 2547–53. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.6.2547-2553.2003. PMC 156567. PMID 12791879.

- ^ Thoen C, Lobue P, de Kantor I (February 2006). "The importance of Mycobacterium bovis as a zoonosis". Veterinary Microbiology. 112 (2–4): 339–45. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.047. PMID 16387455.

- ^ Acton QA (2011). Mycobacterium Infections: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional. ScholarlyEditions. p. 1968. ISBN 978-1-4649-0122-5. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Pfyffer GE, Auckenthaler R, van Embden JD, van Soolingen D (1998). "Mycobacterium canettii, the smooth variant of M. tuberculosis, isolated from a Swiss patient exposed in Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (4): 631–4. doi:10.3201/eid0404.980414. PMC 2640258. PMID 9866740.

- ^ Panteix G, Gutierrez MC, Boschiroli ML, Rouviere M, Plaidy A, Pressac D, et al. (August 2010). "Pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium microti: a study of six recent cases in France". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 59 (Pt 8): 984–989. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.019372-0. PMID 20488936.

- ^ American Thoracic Society (August 1997). "Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 156 (2 Pt 2): S1–25. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement. PMID 9279284.

- ^ Cole EC, Cook CE (August 1998). "Characterization of infectious aerosols in health care facilities: an aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies". American Journal of Infection Control. 26 (4): 453–64. doi:10.1016/S0196-6553(98)70046-X. PMC 7132666. PMID 9721404.

- ^ Nicas M, Nazaroff WW, Hubbard A (March 2005). "Toward understanding the risk of secondary airborne infection: emission of respirable pathogens". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 2 (3): 143–54. doi:10.1080/15459620590918466. PMC 7196697. PMID 15764538.

- ^ a b Ahmed N, Hasnain SE (September 2011). "Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in India: moving forward with a systems biology approach". Tuberculosis. 91 (5): 407–13. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.006. PMID 21514230.

- ^ a b "Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104". World Health Organization (WHO). November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis: What the Clinician Should Know" (PDF) (5th ed.). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. 2011. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Causes of Tuberculosis". Mayo Clinic. 21 December 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Narasimhan P, Wood J, Macintyre CR, Mathai D (2013). "Risk factors for tuberculosis". Pulmonary Medicine. 2013: 828939. doi:10.1155/2013/828939. PMC 3583136. PMID 23476764.

- ^ a b c "The sixteenth global report on tuberculosis" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2012.

- ^ "Global tuberculosis control–surveillance, planning, financing WHO Report 2006". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ^ Chaisson RE, Martinson NA (March 2008). "Tuberculosis in Africa – combating an HIV-driven crisis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (11): 1089–92. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0800809. PMID 18337598.

- ^ Restrepo BI (August 2007). "Convergence of the tuberculosis and diabetes epidemics: renewal of old acquaintances". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (4): 436–38. doi:10.1086/519939. PMC 2900315. PMID 17638190.

- ^ "Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 49 (RR-6): 1–51. June 2000. PMID 10881762. Archived from the original on 17 December 2004.

- ^ van Zyl Smit RN, Pai M, Yew WW, Leung CC, Zumla A, Bateman ED, et al. (January 2010). "Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD". The European Respiratory Journal. 35 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1183/09031936.00072909. PMC 5454527. PMID 20044459.

These analyses indicate that smokers are almost twice as likely to be infected with TB and to progress to active disease (RR of about 1.5 for latent TB infection (LTBI) and RR of ∼2.0 for TB disease). Smokers are also twice as likely to die from TB (RR of about 2.0 for TB mortality), but data are difficult to interpret because of heterogeneity in the results across studies.

- ^ "TB Risk Factors Basic TB Facts TB CDC". cdc.gov. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Möller M, Hoal EG (March 2010). "Current findings, challenges and novel approaches in human genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis". Tuberculosis. 90 (2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2010.02.002. PMID 20206579.

- ^ Good JM, Cooper S, Doane AS (1835). The Study of Medicine. Harper. p. 32. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016.

- ^ a b Skolnik R (2011). Global health 101 (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-7637-9751-5.

- ^ a b Mainous III AR, Pomeroy C (2009). Management of antimicrobials in infectious diseases: impact of antibiotic resistance (2nd rev. ed.). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-60327-238-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Houben EN, Nguyen L, Pieters J (February 2006). "Interaction of pathogenic mycobacteria with the host immune system". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 9 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.014. PMID 16406837.

- ^ Queval CJ, Brosch R, Simeone R (2017). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 2284. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02284. PMC 5703847. PMID 29218036.

- ^ Khan MR (2011). Essence of Paediatrics. Elsevier India. p. 401. ISBN 978-81-312-2804-3. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Herrmann JL, Lagrange PH (February 2005). "Dendritic cells and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: which is the Trojan horse?". Pathologie-Biologie. 53 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2004.01.004. PMID 15620608.

- ^ Agarwal R, Malhotra P, Awasthi A, Kakkar N, Gupta D (April 2005). "Tuberculous dilated cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized entity?". BMC Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-5-29. PMC 1090580. PMID 15857515.

- ^ a b c d Grosset J (March 2003). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the extracellular compartment: an underestimated adversary". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 47 (3): 833–36. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.3.833-836.2003. PMC 149338. PMID 12604509.

- ^ Bozzano F, Marras F, De Maria A (2014). "Immunology of tuberculosis". Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 6 (1): e2014027. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2014.027. PMC 4010607. PMID 24804000.

- ^ Crowley LV (2010). An introduction to human disease: pathology and pathophysiology correlations (8th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-7637-6591-0. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Anthony H (2005). TB/HIV a Clinical Manual (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). p. 75. ISBN 978-92-4-154634-8. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Jacob JT, Mehta AK, Leonard MK (January 2009). "Acute forms of tuberculosis in adults". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (1): 12–17. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.018. PMID 19114163.

- ^ a b Bento J, Silva AS, Rodrigues F, Duarte R (2011). "[Diagnostic tools in tuberculosis]". Acta Médica Portuguesa. 24 (1): 145–54. PMID 21672452.

- ^ a b c d Escalante P (June 2009). "In the clinic. Tuberculosis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (11): ITC61-614, quiz ITV616. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-01006. PMID 19487708. S2CID 639982. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Metcalfe JZ, Everett CK, Steingart KR, Cattamanchi A, Huang L, Hopewell PC, Pai M (November 2011). "Interferon-γ release assays for active pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in adults in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 Suppl 4 (suppl_4): S1120-9. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir410. PMC 3192542. PMID 21996694.

- ^ a b Sester M, Sotgiu G, Lange C, Giehl C, Girardi E, Migliori GB, et al. (January 2011). "Interferon-γ release assays for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The European Respiratory Journal. 37 (1): 100–11. doi:10.1183/09031936.00114810. PMID 20847080.

- ^ Chen J, Zhang R, Wang J, Liu L, Zheng Y, Shen Y, et al. (2011). Vermund SH (ed.). "Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e26827. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626827C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026827. PMC 3206065. PMID 22069472.

- ^ Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (2006). Diagnostics for tuberculosis: global demand and market potential. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). p. 36. ISBN 978-92-4-156330-7. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ a b 미국 국립 보건 및 임상 우수 연구소.임상지침 117: 결핵.런던, 2011년

- ^ Steingart KR, Flores LL, Dendukuri N, Schiller I, Laal S, Ramsay A, et al. (August 2011). Evans C (ed.). "Commercial serological tests for the diagnosis of active pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 8 (8): e1001062. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001062. PMC 3153457. PMID 21857806.

- ^ Rothel JS, Andersen P (December 2005). "Diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: is the demise of the Mantoux test imminent?". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 3 (6): 981–93. doi:10.1586/14787210.3.6.981. PMID 16307510. S2CID 25423684.

- ^ Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D (August 2008). "Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update". Annals of Internal Medicine. 149 (3): 177–84. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00241. PMC 2951987. PMID 18593687.

- ^ Jindal SK, ed. (2011). Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 544. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Amicosante M, Ciccozzi M, Markova R (April 2010). "Rational use of immunodiagnostic tools for tuberculosis infection: guidelines and cost effectiveness studies". The New Microbiologica. 33 (2): 93–107. PMID 20518271.

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Bauman L, Davidson KW, Epling JW, et al. (September 2016). "Screening for Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 316 (9): 962–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.11046. PMID 27599331.

- ^ Gill J, Prasad V (November 2019). "Testing Healthcare Workers for Latent Tuberculosis: Is It Evidence Based, Bio-Plausible, Both, Or Neither?". The American Journal of Medicine. 132 (11): 1260–1261. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.017. PMID 30946831.

- ^ Sosa LE, Njie GJ, Lobato MN, Bamrah Morris S, Buchta W, Casey ML, et al. (May 2019). "Tuberculosis Screening, Testing, and Treatment of U.S. Health Care Personnel: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (19): 439–443. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6819a3. PMC 6522077. PMID 31099768.

- ^ Coker, Richard; Thomas, Marianna; Lock, Karen; Martin, Robyn (2007). "Detention and the Evolving Threat of Tuberculosis: Evidence, Ethics, and Law". Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 35 (4): 609–615. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00184.x. ISSN 1073-1105.

- ^ McShane H (October 2011). "Tuberculosis vaccines: beyond bacille Calmette-Guerin". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 366 (1579): 2782–89. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0097. PMC 3146779. PMID 21893541.

- ^ "Vaccines Basic TB Facts TB CDC". cdc.gov. CDC. 16 June 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, Rodrigues LC, Sridhar S, Habermann S, et al. (August 2014). "Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 349: g4643. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4643. PMC 4122754. PMID 25097193.

- ^ "Vaccine and Immunizations: TB Vaccine (BCG)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ "BCG Vaccine Usage in Canada – Current and Historical". Public Health Agency of Canada. September 2010. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ a b Teo SS, Shingadia DV (June 2006). "Does BCG have a role in tuberculosis control and prevention in the United Kingdom?". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (6): 529–31. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.085043. PMC 2082765. PMID 16714729.

- ^ Kashangura R, Jullien S, Garner P, Johnson S, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (April 2019). "MVA85A vaccine to enhance BCG for preventing tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD012915. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012915.pub2. PMC 6488980. PMID 31038197.

- ^ Clark M, Riben P, Nowgesic E (October 2002). "The association of housing density, isolation and tuberculosis in Canadian First Nations communities". International Journal of Epidemiology. 31 (5): 940–945. doi:10.1093/ije/31.5.940. PMID 12435764.

- ^ Barberis I, Bragazzi NL, Galluzzo L, Martini M (March 2017). "The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 58 (1): E9–E12. PMC 5432783. PMID 28515626.

- ^ "The Global Plan to Stop TB". World Health Organization (WHO). 2011. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, Benz EJ (2005). Sections 1–10 (4. ed., paperback ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 560. ISBN 978-0-19-857014-1. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Uplekar M, Weil D, Lonnroth K, Jaramillo E, Lienhardt C, Dias HM, et al. (May 2015). "WHO's new end TB strategy". Lancet. 385 (9979): 1799–1801. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60570-0. PMID 25814376. S2CID 39379915.

- ^ Fraser A, Paul M, Attamna A, Leibovici L, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (April 2006). "Drugs for preventing tuberculosis in people at risk of multiple-drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005435. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005435.pub2. PMC 6532726. PMID 16625639.

- ^ Piggott DA, Karakousis PC (27 December 2010). "Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in the setting of TB treatment". Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2011: 103917. doi:10.1155/2011/103917. PMC 3017895. PMID 21234380.

- ^ Brennan PJ, Nikaido H (1995). "The envelope of mycobacteria". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 64: 29–63. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. PMID 7574484.

- ^ Davies G, Cerri S, Richeldi L (October 2007). "Rifabutin for treating pulmonary tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005159. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005159.pub2. PMC 6532710. PMID 17943842.

- ^ a b Latent tuberculosis infection. World Health Organization (WHO). 2018. p. 23. ISBN 978-92-4-155023-9. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Borisov AS, Bamrah Morris S, Njie GJ, Winston CA, Burton D, Goldberg S, et al. (June 2018). "Update of Recommendations for Use of Once-Weekly Isoniazid-Rifapentine Regimen to Treat Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67 (25): 723–726. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6725a5. PMC 6023184. PMID 29953429.

- ^ a b Sterling TR, Njie G, Zenner D, Cohn DL, Reves R, Ahmed A, et al. (February 2020). "Guidelines for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 69 (1): 1–11. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6901a1. PMC 7041302. PMID 32053584.

- ^ Njie GJ, Morris SB, Woodruff RY, Moro RN, Vernon AA, Borisov AS (August 2018). "Isoniazid-Rifapentine for Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 55 (2): 244–252. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.030. PMC 6097523. PMID 29910114.

- ^ Menzies D, Al Jahdali H, Al Otaibi B (March 2011). "Recent developments in treatment of latent tuberculosis infection". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 133 (3): 257–66. PMC 3103149. PMID 21441678.

- ^ M'imunya JM, Kredo T, Volmink J, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (May 2012). "Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD006591. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006591.pub2. PMC 6532681. PMID 22592714.

- ^ Gelband H, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (25 October 1999). "Regimens of less than six months for treating tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001362. PMC 6532732. PMID 10796641.

- ^ Grace AG, Mittal A, Jain S, Tripathy JP, Satyanarayana S, Tharyan P, Kirubakaran R, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (December 2019). "Shortened treatment regimens versus the standard regimen for drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD012918. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012918.pub2. PMC 6953336. PMID 31828771.

- ^ "Landmark TB Trial Identifies Shorter-Course Treatment Regimen". CDC. NCHHSTP Media Team Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 October 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Mainous III AB (2010). Management of Antimicrobials in Infectious Diseases: Impact of Antibiotic Resistance. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-60327-238-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Karumbi J, Garner P (May 2015). "Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003343. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003343.pub4. PMC 4460720. PMID 26022367.

- ^ Liu Q, Abba K, Alejandria MM, Sinclair D, Balanag VM, Lansang MA, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (November 2014). "Reminder systems to improve patient adherence to tuberculosis clinic appointments for diagnosis and treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD006594. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006594.pub3. PMC 4448217. PMID 25403701.

- ^ Mwandumba HC, Squire SB, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (23 October 2001). "Fully intermittent dosing with drugs for treating tuberculosis in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000970. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000970. PMC 6532565. PMID 11687088.

- ^ Bose A, Kalita S, Rose W, Tharyan P, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (January 2014). "Intermittent versus daily therapy for treating tuberculosis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007953. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007953.pub2. PMC 6532685. PMID 24470141.

- ^ O'Brien RJ (June 1994). "Drug-resistant tuberculosis: etiology, management and prevention". Seminars in Respiratory Infections. 9 (2): 104–12. PMID 7973169.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (March 2006). "Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs--worldwide, 2000-2004". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 55 (11): 301–5. PMID 16557213. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017.

- ^ a b McKenna M (12 January 2012). "Totally Resistant TB: Earliest Cases in Italy". Wired. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Migliori GB, De Iaco G, Besozzi G, Centis R, Cirillo DM (May 2007). "First tuberculosis cases in Italy resistant to all tested drugs". Euro Surveillance. 12 (5): E070517.1. doi:10.2807/esw.12.20.03194-en. PMID 17868596.

- ^ "Totally Drug-Resistant TB: a WHO consultation on the diagnostic definition and treatment options" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Kielstra P (30 June 2014). Tabary Z (ed.). "Ancient enemy, modern imperative – A time for greater action against tuberculosis" (PDF). The Economist. Economist Intelligence Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Singh B, Cocker D, Ryan H, Sloan DJ, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (March 2019). "Linezolid for drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD012836. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012836.pub2. PMC 6426281. PMID 30893466.

- ^ Velayati AA, Masjedi MR, Farnia P, Tabarsi P, Ghanavi J, ZiaZarifi AH, Hoffner SE (August 2009). "Emergence of new forms of totally drug-resistant tuberculosis bacilli: super extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis or totally drug-resistant strains in Iran". Chest. 136 (2): 420–425. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2427. PMID 19349380.

- ^ "Provisional CDC Guidelines for the Use and Safety Monitoring of Bedaquiline Fumarate (Sirturo) for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis". Archived from the original on 4 January 2014.

- ^ Theron G, Peter J, Richardson M, Warren R, Dheda K, Steingart KR, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (September 2016). "® MTBDRsl assay for resistance to second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD010705. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010705.pub3. PMC 5034505. PMID 27605387.

- ^ "The use of molecular line probe assays for the detection of resistance to second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Lambert ML, Hasker E, Van Deun A, Roberfroid D, Boelaert M, Van der Stuyft P (May 2003). "Recurrence in tuberculosis: relapse or reinfection?". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 3 (5): 282–7. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00607-8. PMID 12726976.

- ^ Wang JY, Lee LN, Lai HC, Hsu HL, Liaw YS, Hsueh PR, Yang PC (July 2007). "Prediction of the tuberculosis reinfection proportion from the local incidence". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196 (2): 281–8. doi:10.1086/518898. PMID 17570116.

- ^ "1.4 Prognosis - Tuberculosis". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Fact Sheets: The Difference Between Latent TB Infection and Active TB Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 20 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ "Global tuberculosis report 2013". World Health Organization (WHO). 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2006.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ a b c "Global Tuberculosis Control 2011" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "Tuberculosis". WHO. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Douglas AS, Strachan DP, Maxwell JD (September 1996). "Seasonality of tuberculosis: the reverse of other respiratory diseases in the UK". Thorax. 51 (9): 944–946. doi:10.1136/thx.51.9.944. PMC 472621. PMID 8984709.

- ^ Martineau AR, Nhamoyebonde S, Oni T, Rangaka MX, Marais S, Bangani N, et al. (November 2011). "Reciprocal seasonal variation in vitamin D status and tuberculosis notifications in Cape Town, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (47): 19013–19017. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111825108. PMC 3223428. PMID 22025704.

- ^ Parrinello CM, Crossa A, Harris TG (January 2012). "Seasonality of tuberculosis in New York City, 1990-2007". The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 16 (1): 32–37. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0145. PMID 22236842.

- ^ a b Korthals Altes H, Kremer K, Erkens C, van Soolingen D, Wallinga J (May 2012). "Tuberculosis seasonality in the Netherlands differs between natives and non-natives: a role for vitamin D deficiency?". The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 16 (5): 639–644. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0680. PMID 22410705.

- ^ Koh GC, Hawthorne G, Turner AM, Kunst H, Dedicoat M (2013). "Tuberculosis incidence correlates with sunshine: an ecological 28-year time series study". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e57752. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857752K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057752. PMC 3590299. PMID 23483924.

- ^ Kuddus MA, McBryde ES, Adegboye OA (September 2019). "Delay effect and burden of weather-related tuberculosis cases in Rajshahi province, Bangladesh, 2007-2012". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 12720. Bibcode:2019NatSR...912720K. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49135-8. PMC 6722246. PMID 31481739.

- ^ Griffith DE, Kerr CM (August 1996). "Tuberculosis: disease of the past, disease of the present". Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 11 (4): 240–45. doi:10.1016/S1089-9472(96)80023-2. PMID 8964016.

- ^ "Global Tuberculosis Control Report, 2006 – Annex 1 Profiles of high-burden countries" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ^ "2005 Surveillance Slide Set". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 September 2006. Archived from the original on 23 November 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ^ FitzGerald JM, Wang L, Elwood RK (February 2000). "Tuberculosis: 13. Control of the disease among aboriginal people in Canada". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 162 (3): 351–55. PMC 1231016. PMID 10693593.

- ^ Quah SR, Carrin G, Buse K, Heggenhougen K (2009). Health Systems Policy, Finance, and Organization. Boston: Academic Press. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-12-375087-7. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ 의학 연구 위원회MRC의 발신기지.2008년 4월 11일 2006년 10월 7일에 액세스 된 웨이백 머신에 아카이브.

- ^ 블라디미르 M.Shkolnikov와 France Meslee.사망률 추세가 반영된 러시아 역학 위기 2020년 8월 11일 Wayback Machine, 표 4.11에 보관되어 있다.

- ^ WHO, Wayback Machine, 2011에서 2006년 12월 12일 글로벌 결핵 대책 아카이브.

- ^ "WHO global tuberculosis report 2016. Annex 2. Country profiles: Russian Federation". Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Global Tuberculosis Report 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ "WHO Global tuberculosis report 2016: India". Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Govt revisits strategy to combat tuberculosis". Daily News and Analysis. 8 April 2017. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Mahla RS (August 2018). "Prevalence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 18 (8): 836. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30401-8. PMID 30064674.

- ^ Birn AE (2009). Textbook of International Health: Global Health in a Dynamic World. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-19-988521-3. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ "CDC Surveillance Slides 2012 – TB". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Al-Azem A, Kaushal Sharma M, Turenne C, Hoban D, Hershfield E, MacMorran J, Kabani A (1998). "Rural outbreaks of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Canadian province". Abstr Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 38: 555. abstract no. L-27. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011.

- ^ "Tuberculosis incidence (per 100,000 people)". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ "Tuberculosis deaths by region". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Rothschild BM, Martin LD, Lev G, Bercovier H, Bar-Gal GK, Greenblatt C, et al. (August 2001). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA from an extinct bison dated 17,000 years before the present". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 33 (3): 305–11. doi:10.1086/321886. PMID 11438894.

- ^ Pearce-Duvet JM (August 2006). "The origin of human pathogens: evaluating the role of agriculture and domestic animals in the evolution of human disease". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 81 (3): 369–82. doi:10.1017/S1464793106007020. PMID 16672105. S2CID 6577678.

- ^ Comas I, Gagneux S (October 2009). Manchester M (ed.). "The past and future of tuberculosis research". PLOS Pathogens. 5 (10): e1000600. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000600. PMC 2745564. PMID 19855821.

- ^ Zink AR, Sola C, Reischl U, Grabner W, Rastogi N, Wolf H, et al. (January 2003). "Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNAs from Egyptian mummies by spoligotyping". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 41 (1): 359–67. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.1.359-367.2003. PMC 149558. PMID 12517873.

- ^ Konomi N, Lebwohl E, Mowbray K, Tattersall I, Zhang D (December 2002). "Detection of mycobacterial DNA in Andean mummies". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (12): 4738–40. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.12.4738-4740.2002. PMC 154635. PMID 12454182.

- ^ Sledzik PS, Bellantoni N (June 1994). "Brief communication: bioarcheological and biocultural evidence for the New England vampire folk belief" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 94 (2): 269–74. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330940210. PMID 8085617. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2017.

- ^ 레옹 샤를 알베르 칼메트라는 이름을 누가 지었습니까?

- ^ Trail RR (April 1970). "Richard Morton (1637-1698)". Medical History. 14 (2): 166–74. doi:10.1017/S0025727300015350. PMC 1034037. PMID 4914685.

- ^ 마틴 B(1720년).새로운 이론 Consumptions—More의 Especially Phthisis 또는 소비의 Lungs.영국 런던:T.Knaplock.P.51:"Animalcula 또는 아주 미세한 사는 생물의 오리지널과 필수적인 원인..것이 가능할 어떠한 특정 종,..."P.79:"따라서, 상습적인 한 Consumptive 환자와 같은 침대에서, 끊임없이 그와 함께 마시는 것에 의해 먹는 것은 거짓말을 하면서 매우 자주 있어서 거의, d로로 심각한 대화를 나눌 수 있는폐에서 뿜어내는 호흡의 일부분이 생으로, 건강한 사람에 의해 폐병이 잡힐 수 있다."

- ^ ReneLaennec은 RT(1819년).드 l'auscultation médiate...(프랑스어로).제1권. 프랑스 파리:J.-A.Brosson(J.-S Chaudé. p. 20.26월 2021년에 원래에서 Archived.612월 2020년 Retrieved.페이지의 주 20:"L'existence 데 dans 르poumon.(원인(constitue 르charactère anatomique propre 드 라 phthisie pulmonaire(a).(a)...l'effet하고 있어 cette maladie 타이어 아들 nominalcapital공칭 자본, c'est-à-dire, 드 라 소비 tubercules."부터(폐에서는 좀 혹의 존재 원인과 폐 관의 독특한 해부학적 특징을 구성한다.rculosis (a) (a) ...이 질병[폐결핵]이 그 이름을 갖게 된 영향, 즉 폐병).

- ^ Schönlein JL (1832). Allgemeine und specielle Pathologie und Therapie [General and Special Pathology and Therapy] (in German). Vol. 3. Würzburg, (Germany): C. Etlinger. p. 103. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "결핵"이라는 단어는 1829년 Schönlein의 임상 노트에 처음 등장했습니다.:제이 SJ, Kırbıyık U, 우즈는 JR, 스틸 GA, 호이트었고, GR도 Schwengber RB, 굽타 P(11월 2018년)를 참조하십시오."결핵의 현대 이론:미국의 역사적 기원의 유럽과 북미에서culturomic 분석".국제 저널 결핵, 폐 학회. 22(11):1249–1257. doi:10.5588/ijtld.18.0239.PMID 30355403.S2CID 53027676.참고 특히 부록 페이지의 주 iii.

- ^ 켄터키: 역사가 긴 매머드 동굴.2006년 8월 13일 Wayback Machine CNN에서 아카이브.2004년 2월 27일.2006년 10월 8일에 액세스.

- ^ a b c McCarthy OR (August 2001). "The key to the sanatoria". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 94 (8): 413–17. doi:10.1177/014107680109400813. PMC 1281640. PMID 11461990. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Villemin JA (1865). "Cause et nature de la tuberculose" [Cause and nature of tuberculosis]. Bulletin de l'Académie Impériale de Médecine (in French). 31: 211–216.

- 다음 항목도 참조하십시오.

- ^ Burdon-Sanderson, John Scott. (1870) "전염의 친밀한 병리학에 대한 입문 보고서"부록:추밀원 의료관 12차 보고서 (1869년)제38권, 229-256권

- ^ Koch R (24 March 1882). "Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose" [The Etiology of Tuberculosis]. Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift. 19: 221–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-56454-7_4. ISBN 978-3-662-56454-7. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "History: World TB Day". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ 노벨 재단노벨 생리의학상 1905년.2006년 12월 10일 Wayback Machine 액세스 2006년 10월 7일에 아카이브 완료.

- ^ Waddington K (January 2004). "To stamp out 'so terrible a malady': bovine tuberculosis and tuberculin testing in Britain, 1890–1939". Medical History. 48 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1017/S0025727300007043. PMC 546294. PMID 14968644.

- ^ Bonah C (December 2005). "The 'experimental stable' of the BCG vaccine: safety, efficacy, proof, and standards, 1921–1933". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 36 (4): 696–721. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2005.09.003. PMID 16337557.

- ^ Comstock GW (September 1994). "The International Tuberculosis Campaign: a pioneering venture in mass vaccination and research". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 19 (3): 528–40. doi:10.1093/clinids/19.3.528. PMID 7811874.

- ^ Hannaway C (2008). Biomedicine in the twentieth century: practices, policies, and politics. Amsterdam: IOS Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-58603-832-8. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ^ Bloom BR (1994). Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, DC: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-55581-072-6.

- ^ Frith J. "History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague". Journal of Military and Veterans' Health. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Zürcher K, Zwahlen M, Ballif M, Rieder HL, Egger M, Fenner L (5 October 2016). "Influenza Pandemics and Tuberculosis Mortality in 1889 and 1918: Analysis of Historical Data from Switzerland". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0162575. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1162575Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162575. PMC 5051959. PMID 27706149.

- ^ a b Persson S (2010). Smallpox, Syphilis and Salvation: Medical Breakthroughs That Changed the World. ReadHowYouWant.com. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4587-6712-7. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Shields T (2009). General thoracic surgery (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 792. ISBN 978-0-7817-7982-1. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Lalloo UG, Naidoo R, Ambaram A (May 2006). "Recent advances in the medical and surgical treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 12 (3): 179–85. doi:10.1097/01.mcp.0000219266.27439.52. PMID 16582672. S2CID 24221563.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions about TB and HIV". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Lawlor C. "Katherine Byrne, Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination". British Society for Literature and Science. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Hippocrates 3.16 Classics, MIT". Archived from the original on 11 February 2005. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지보수: 부적합한 URL(링크) - ^ Caldwell M (1988). The Last Crusade. New York: Macmillan. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-689-11810-4.

- ^ Bunyan J (1808). The Life and Death of Mr. Badman. London: W. Nicholson. p. 244. Retrieved 28 September 2016 – via Internet Archive.

captain.

- ^ Byrne K (2011). Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67280-2.

- ^ "About Chopin's illness". Icons of Europe. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Vilaplana C (March 2017). "A literary approach to tuberculosis: lessons learned from Anton Chekhov, Franz Kafka, and Katherine Mansfield". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 56: 283–85. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2016.12.012. PMID 27993687.

- ^ Rogal SJ (1997). A William Somerset Maugham Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-313-29916-2. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Eschner K. "George Orwell Wrote '1984' While Dying of Tuberculosis". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Tuberculosis (whole issue)". Journal of the American Medical Association. 293 (22): cover. 8 June 2005. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Lemlein RF (1981). "Influence of Tuberculosis on the Work of Visual Artists: Several Prominent Examples". Leonardo. 14 (2): 114–11. doi:10.2307/1574402. JSTOR 1574402. S2CID 191371443. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Wilsey AM (May 2012). 'Half in Love with Easeful Death:' Tuberculosis in Literature. Humanities Capstone Projects (PhD Thesis thesis). Pacific University. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ a b Morens DM (November 2002). "At the deathbed of consumptive art". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (11): 1353–8. doi:10.3201/eid0811.020549. PMC 2738548. PMID 12463180.

- ^ "Pulmonary Tuberculosis/In Literature and Art". McMaster University History of Diseases. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Thomson G (1 June 2016). "Van Morrison – 10 of the best". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Tuberculosis Throughout History: The Arts" (PDF). United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Corliss R (22 December 2008). "Top 10 Worst Christmas Movies". Time. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

'If you don't cry when Bing Crosby tells Ingrid Bergman she has tuberculosis', Joseph McBride wrote in 1973, 'I never want to meet you, and that's that.'

- ^ "The End TB Strategy". who.int. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Global tuberculosis report 2020. World Health Organization. 2020. ISBN 978-92-4-001313-1. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Public–Private Partnership Announces Immediate 40 Percent Cost Reduction for Rapid TB Test" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 6 August 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Lawn SD, Nicol MP (September 2011). "Xpert® MTB/RIF assay: development, evaluation and implementation of a new rapid molecular diagnostic for tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance". Future Microbiology. 6 (9): 1067–82. doi:10.2217/fmb.11.84. PMC 3252681. PMID 21958145.

- ^ "WHO says Cepheid rapid test will transform TB care". Reuters. 8 December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 December 2010.

- ^ STOPTB (5 April 2013). "The Stop TB Partnership, which operates through a secretariat hosted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2014.

- ^ Lienhardt C, Espinal M, Pai M, Maher D, Raviglione MC (November 2011). "What research is needed to stop TB? Introducing the TB Research Movement". PLOS Medicine. 8 (11): e1001135. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001135. PMC 3226454. PMID 22140369.

- ^ Sandhu GK (2011). "Tuberculosis: Current Situation, Challenges and Overview of its Control Programs in India". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 3 (2): 143–150. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.81691. ISSN 0974-777X. PMC 3125027. PMID 21731301.

- ^ Bhargava A, Pinto L, Pai M (2011). "Mismanagement of tuberculosis in India: Causes, consequences, and the way forward" (PDF). Hypothesis. 9 (1): e7. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 유지보수: 부적합한 URL(링크) - ^ Amdekar Y (July 2009). "Changes in the management of tuberculosis". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 76 (7): 739–42. doi:10.1007/s12098-009-0164-4. PMID 19693453. S2CID 41788291. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marks GB (September 2011). "Active case finding in contacts of people with tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD008477. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008477.pub2. PMC 6532613. PMID 21901723.

- ^ Mhimbira FA, Cuevas LE, Dacombe R, Mkopi A, Sinclair D, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (November 2017). "Interventions to increase tuberculosis case detection at primary healthcare or community-level services". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (11): CD011432. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011432.pub2. PMC 5721626. PMID 29182800.

- ^ Braganza Menezes D, Menezes B, Dedicoat M, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (August 2019). "Contact tracing strategies in household and congregate environments to identify cases of tuberculosis in low- and moderate-incidence populations". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (8): CD013077. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013077.pub2. PMC 6713498. PMID 31461540.

- ^ a b c d e f g Courtwright A, Turner AN (July–August 2010). "Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions". Public Health Reports. 125 Suppl 4 (4_suppl): 34–42. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S407. PMC 2882973. PMID 20626191.

- ^ Mason PH, Roy A, Spillane J, Singh P (March 2016). "Social, Historical and Cultural Dimensions of Tuberculosis". Journal of Biosocial Science. 48 (2): 206–32. doi:10.1017/S0021932015000115. PMID 25997539.

- ^ a b c Martín Montañés C, Gicquel B (March 2011). "New tuberculosis vaccines". Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 29 Suppl 1: 57–62. doi:10.1016/S0213-005X(11)70019-2. PMID 21420568.

- ^ Zhu B, Dockrell HM, Ottenhoff TH, Evans TG, Zhang Y (April 2018). "Tuberculosis vaccines: Opportunities and challenges". Respirology. 23 (4): 359–368. doi:10.1111/resp.13245. PMID 29341430.

- ^ Ibanga HB, Brookes RH, Hill PC, Owiafe PK, Fletcher HA, Lienhardt C, et al. (August 2006). "Early clinical trials with a new tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, in tuberculosis-endemic countries: issues in study design". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 6 (8): 522–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70552-7. PMID 16870530.

- ^ Kaufmann SH (October 2010). "Future vaccination strategies against tuberculosis: thinking outside the box". Immunity. 33 (4): 567–77. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.015. PMID 21029966.

- ^ Webber D, Kremer M (2001). "Stimulating Industrial R&D for Neglected Infectious Diseases: Economic Perspectives" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 79 (8): 693–801. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007.

- ^ Barder O, Kremer M, Williams H (2006). "Advance Market Commitments: A Policy to Stimulate Investment in Vaccines for Neglected Diseases". The Economists' Voice. 3 (3). doi:10.2202/1553-3832.1144. S2CID 154454583. Archived from the original on 5 November 2006.

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2009). Achieving the global public health agenda: dialogues at the Economic and Social Council. New York: United Nations. p. 103. ISBN 978-92-1-104596-3. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Jong EC, Zuckerman JN (2010). Travelers' vaccines (2nd ed.). Shelton, CT: People's Medical Publishing House. p. 319. ISBN 978-1-60795-045-5. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Announcement (12 February 2004). "Gates Foundation Commits $82.9 Million to Develop New Tuberculosis Vaccines". Archived from the original on 10 October 2009.

- ^ Nightingale K (19 September 2007). "Gates foundation gives US$280 million to fight TB". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ a b Zumla A, Hafner R, Lienhardt C, Hoelscher M, Nunn A (March 2012). "Advancing the development of tuberculosis therapy". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 11 (3): 171–2. doi:10.1038/nrd3694. PMID 22378254. S2CID 7232434. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "J&J Sirturo Wins FDA Approval to Treat Drug-Resistant TB". Bloomberg News. 31 December 2012. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ a b Avorn J (April 2013). "Approval of a tuberculosis drug based on a paradoxical surrogate measure". JAMA. 309 (13): 1349–50. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.623. PMID 23430122.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration. "Briefing Package: NDA 204–384: Sirturo" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2014.

- ^ Zuckerman D, Yttri J (January 2013). "Antibiotics: When science and wishful thinking collide". Health Affairs. doi:10.1377/forefront.20130125.027503.

- ^ Critchley JA, Orton LC, Pearson F (November 2014). "Adjunctive steroid therapy for managing pulmonary tuberculosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD011370. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011370. PMC 6532561. PMID 25387839.

- ^ Shivaprasad HL, Palmieri C (January 2012). "Pathology of mycobacteriosis in birds". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 15 (1): 41–55, v–vi. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.11.004. PMID 22244112.

- ^ Reavill DR, Schmidt RE (January 2012). "Mycobacterial lesions in fish, amphibians, reptiles, rodents, lagomorphs, and ferrets with reference to animal models". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 15 (1): 25–40, v. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.10.001. PMID 22244111.

- ^ Mitchell MA (January 2012). "Mycobacterial infections in reptiles". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 15 (1): 101–11, vii. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.10.002. PMID 22244116.

- ^ Wobeser GA (2006). Essentials of disease in wild animals (1st ed.). Ames, IO [u.a.]: Blackwell Publishing. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8138-0589-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Ryan TJ, Livingstone PG, Ramsey DS, de Lisle GW, Nugent G, Collins DM, et al. (February 2006). "Advances in understanding disease epidemiology and implications for control and eradication of tuberculosis in livestock: the experience from New Zealand". Veterinary Microbiology. 112 (2–4): 211–19. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.025. PMID 16330161.

- ^ White PC, Böhm M, Marion G, Hutchings MR (September 2008). "Control of bovine tuberculosis in British livestock: there is no 'silver bullet'". Trends in Microbiology. 16 (9): 420–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.566.5547. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2008.06.005. PMID 18706814.

- ^ Ward AI, Judge J, Delahay RJ (January 2010). "Farm husbandry and badger behaviour: opportunities to manage badger to cattle transmission of Mycobacterium bovis?". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 93 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.09.014. PMID 19846226.