호미니니

Hominini| 호미니니 시간 범위: Ma K N | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2개의 호미닌:침팬지를 안고 있는 인간(호모 사피엔스) | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 챠다타 |

| 클래스: | 젖꼭지 |

| 주문: | 영장류 |

| 서브오더: | 하플로히니 |

| 인프라스트럭처: | 심이폼목 |

| 패밀리: | 호미나과 |

| 서브패밀리: | 인간아과 |

| 부족: | 호미니니 아람부르, 1948년[1] |

| 표준속 | |

| 호모 린네, 1758년 | |

| 속 | |

호미니족은 호미니아과(Homininae)의 분류학적 부족을 형성한다.호미니속은 현존하는 호모속(인간)과 판속(침팬지와 보노보속)을 포함하며, 표준 용법에서는 고릴라속(고릴라속)을 제외한다.

이 용어는 카밀 아람부르(1948)에 의해 처음 도입되었다.Arambourg는 그레이(1825)로 인한 호미니나와 시미나의 범주를 그의 새로운 하위 문장으로 결합했다.

전통적으로 침팬지, 고릴라, 오랑우탄은 퐁기드로 함께 분류되었다.그레이의 분류 이후, 인간과 침팬지, 그리고 고릴라가 [3]오랑우탄보다 서로 더 밀접하게 연관되어 있다는 것을 확인하는 유전적 계통학으로부터 증거가 축적되었다.이전의 퐁기드는 이미 [3]인간을 포함한 호미니과(Hominidae)로 재배정되었지만, 이러한 재배정의 세부 사항은 여전히 논란이 되고 있다. 호미니니 내에서 모든 출처가 고릴라를 제외하는 것은 아니며, 모든 출처가 침팬지를 포함하는 것은 아니다.

인류는 오스트랄로피테카인(Australopithecine) 지류(subtribe)에 현존하는 유일한 종이며, 이 지류에는 인간의 멸종된 가까운 친척들도 많이 포함되어 있다.

용어와 정의

회원 자격과 관련하여, 호미니니가 판을 제외하는 것으로 간주될 때, 파니니("Panins")[4]는 판을 포함하는 부족을 유일한 [5][6]속이라고 언급할 수 있다.또는 아마도 판을 다른 드라이오피테쿠스속과 함께 놓아 파니니족이나 파니나의 전체 부족 또는 하위 종족들을 하나로 만들 수 있습니다.소수파 반대 지명으로는 호미니니의 고릴라와 호모의 팬(Goodman 등 1998년), 호모의 팬과 고릴라가 있다(Watson 등 2001년).

관례상, 형용사 용어 "호미닌" (또는 명목화된 "호미닌")은 호미니니 부족을 지칭하는 반면, 하위 기술인 호미니나 (그리고 모든 고대 인류 종족)의 구성원들은 "호미니니아" ("호미니안")[7][8][9]으로 지칭된다.이는 호미니 부족이 판과 호모를 모두 포함한다고 제시한 만과 바이스(1996)의 제안에 따른 것이다.판속은 파니나 아족으로 불리며 호모속은 [10]호미니나 아족에 포함된다.하지만, "호미닌"을 사용하여 파니나의 구성원들, 즉 호모만을 위한 것이거나 인간과 오스트랄로피테쿠스 종 모두를 위한 것을 제외하는 대체 규정이 있습니다.이 대체 규약은 예를 들어 에 언급되어 있습니다.코인(2009년)[11]과 던바(2014년)[6]에서.팟츠(2010)는 판(Pan)을 제외한 다른 의미로 호미니니(Hominini)라는 이름을 사용하며 침팬지를 위한 별도의 부족(아족)을 파니니(Panini)[5]라는 이름으로 도입했다.최근의 이 전당 대회에서 콘트라 Arambourg, 이 용어"hominin", 인류는 오스트랄로 피테쿠스, 아르디 피테 쿠스, 그리고 침팬지(아래 분기도 보)으로 이어지는 라인을 이별 뒤에 일어났다 다른 사람들에게;[12][13]즉, 그들이,"hominins"이들은 연장에서, 과거 분열의 인간적인 면모에 화석들과 구별하는 적용된다.아니hominins" (또는 "비호미닌 호미니드")[11]

분해도

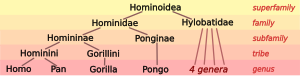

이 분지도는 호미니(호미니 조상이 아닌 분지)의 분지에 초점을 맞춘 호미니상과와 그 후손 분지군을 보여준다.호미니과(Hominidae)는 오랑우탄을 포함한 폰기아과(Ponginae), 고릴리니족(Gorillini), 호미니족(Hominini)으로 이루어져 있으며, 후자의 두 과는 호미니족의 아과를 형성하고 있다.호미니니는 파니나와 오스트랄로피테치나로 나뉜다.호미니나(인간)는 일반적으로 오스트랄로피테시나 내에서 나타난 것으로 간주된다(판(Pan)을 제외한 대체 정의에 따르면 호미니니의 대체 정의에 대략 일치한다).

화석 증거와 결합된 유전자 분석에 따르면, 인류는 약 2500만년 전 올리고세-마이오세 [14]경계 부근에서 구세계 원숭이로부터 분리되었다고 한다.Homininae와 Ponginae 아과의 가장 최근의 공통 조상(MRCA)은 약 1500만년 전에 살았다.Ponginae의 가장 잘 알려진 화석 속은 시바피테쿠스이며, 1250만 년 전부터 850만 년 전까지의 여러 종으로 구성되어 있다.오랑우탄과 치아의 형태학에서 [15]다르다.다음 분해도에서, 분지군이 방사한 대략적인 시간은 수백만 년 전(Mya)으로 표시된다.

| 호미노아과(20.4Mya) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

진화사

사헬란트로푸스와 오로린 둘 다 800만 년에서 400만 년 전 사이에 조상 침팬지-인간 분화 사건의 추정 기간 동안 존재했다.판속의 직접 조상이라고 할 수 있는 화석 표본은 거의 발견되지 않았다.케냐에서 발견된 최초의 침팬지 화석 소식은 2005년에 발표되었다.하지만, 그것은 545년에서 284,000년 [16]전 사이의 매우 최근 시대로 거슬러 올라갑니다.판과 분리된 친인류 또는 "선인류" 혈통의 분리는 완전히 갈라지기 보다는 복잡한 분화-교배 과정으로 보이며, 13Mya(호미니족 자체의 나이와 비슷한 나이)에서 약 4Mya 사이의 어느 곳에서나 일어난다.패터슨 외 연구진에 따르면, 다른 염색체들은 서로 다른 시기에 분열된 것으로 보이며, 6.3~5.4Mya 기간 동안 두 개의 출현하는 계통들 사이에서 광범위한 교배 활동이 일어났다.(2006년),[17]이 연구 그룹은 한 번의 가설적인 후기 교배기는 특히 원시 인류와 줄기 침팬지의 X 염색체 유사성에 기초하고 있으며, 이는 최종 교배기가 심지어 4Mya만큼 최근이었다는 것을 암시한다.웨이클리(2008)는 침팬지-인간 마지막 공통 조상(CHLCA)[18] 이전에 조상 집단의 X 염색체에 대한 선택 압력을 포함한 다른 설명을 제안했다.

대부분의 DNA 연구는 인간과 Pan이 99% [19][20]동일하다는 것을 발견했지만, 한 연구는 코드화되지 않은 [21]DNA에서 일부 차이가 발생하면서 94%의 공통성만을 발견했다.4.4Mya에서 3Mya까지 거슬러 올라가는 오스트랄로피테카인은 [22][23]호모속의 초기 구성원으로 진화했을 가능성이 높다.2000년, 호모가 사실 오스트랄로피테쿠스 [25]조상으로부터 유래한 것이 아니라는 것을 암시하면서, 일찍이 6.2Mya로 거슬러 올라가는 Orrorin tugenensis의 발견은 그 [24]가설의 비판적인 요소들에 잠시 이의를 제기했다.나열된 모든 화석 속은 다음 항목에 대해 평가됩니다.

- 호모의 조상일 확률과

- 그들이 다른 어떤 영장류보다 호모에 더 가까운지 여부 - 그들을 호미닌으로 식별할 수 있는 두 가지 특성.

파란트로푸스, 아르디피테쿠스, 오스트랄로피테쿠스를 포함한 어떤 것들은 널리 조상이고 [26]호모와 밀접한 관련이 있는 것으로 생각되고 있다; 다른 속들, 특히 사헬란트로푸스를 포함한 다른 속들은 과학자들의 한 집단에서 지지를 받고 있지만 [27][28]다른 집단에서는 의심을 받고 있다.

알려진 호미닌종 목록

현존하는 종은 굵은 글씨로 되어 있다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Arambourg, C. (1948). "La Classification des Primates et Particulierement des Hominiens". Mammalia. 12 (3). doi:10.1515/mamm.1948.12.3.123. ISSN 0025-1461. S2CID 84553920.

- ^ Fuss, J.; Spassov, N.; Begun, D. R.; Böhme, M. (2017). "Potential hominin affinities of Graecopithecus from the Late Miocene of Europe". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0177127. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1277127F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177127. PMC 5439669. PMID 28531170.

- ^ a b McNulty, Kieran P. (2016). "Hominin taxonomy and phylogeny: what's in a name?". Nature. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

However, overwhelming genetic evidence has since demonstrated that humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas are much more closely related to each other than to the orangutan ... Thus, there is no genetic support for grouping the great apes together in a distinct group from humans. For this reason, many researchers now place all species of great ape and human within a single family, Hominidae – making them all proper "hominids".

- ^ Delson (1977). "Catarrhine phylogeny and classification: principles, methods and comments". Journal of Human Evolution. 6 (5): 450. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(77)80057-2.

- ^ a b Potts (2010). What does it mean to be human?. Washington: National Geographic Society. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4262-0606-1.

- ^ a b Dunbar, Robin (2014). Human evolution. ISBN 9780141975313.

Conventionally, taxonomists now refer to the great ape family (including humans) as 'hominids', while all members of the lineage leading to modern humans that arose after the split with the [Homo-Pan] LCA are referred to as 'hominins'. The older literature used the terms hominoids and hominids respectively.

- ^ Andrews, Peter; Harrison, Terry (2005-01-01). "The Last Common Ancestor of Apes and Humans". Interpreting the Past: 103–121. doi:10.1163/9789047416616_013. ISBN 9789047416616. S2CID 203884394.

- ^ Diogo, Rui; Wood, Bernard (2015-11-20). Boughner, Julia C.; Rolian, Campbell (eds.). Origin, Development, and Evolution of Primate Muscles, with Notes on Human Anatomical Variations and Anomalies. Developmental Approaches to Human Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 167–204. doi:10.1002/9781118524756.ch8. ISBN 978-1-118-52475-6. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- ^ Worthington, Steven (May 2012). New approaches to late Miocene hominoid systematics: Ranking morphological characters by phylogenetic signal (PhD). New York University. Retrieved 2022-04-30 – via www.proquest.com.

- ^ Mann, Alan; Weiss, Mark (1996). "Hominoid phylogeny and taxonomy: a consideration of the molecular and fossil evidence in an historical perspective". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 5 (1): 169–181. doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0011. PMID 8673284.

- ^ a b Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why evolution is true. London: Penguin Books. pp. 197–208, 244, 248. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9.

Anthropologists apply the term hominin to all the species on the "human" side of our family tree after it split from the branch that became modern chimps." (p.197)

- ^ Brenda J. Bradley (1 April 2008). "Reconstructing phylogenies and phenotypes: a molecular view of human evolution". Journal of Anatomy. 212 (4): 337–353. doi:10.1111/J.1469-7580.2007.00840.X. ISSN 1469-7580. PMC 2409108. PMID 18380860. Wikidata Q24646554.

- ^ Wood; Richmond, B. G. (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.

Thus human evolution is the study of the lineage, or clade, comprising species more closely related to modern humans than to chimpanzees. Its stem species is the so-called 'common hominin ancestor', and its only extant member is Homo sapiens. This clade contains all the species more closely related to modern humans than to any other living primate. Until recently, these species were all subsumed into a family, Hominidae, but this group is now more usually recognised as a tribe, the Hominini.

- ^ "Fossils may pinpoint critical split between apes and monkeys". redOrbit.com. 15 May 2013.

- ^ Taylor, C. (2011). "Old men of the woods". Palaeos. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ McBrearty, Sally; Jablonski, Nina G. (2005). "First fossil chimpanzee". Nature. 437 (7055): 105–108. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..105M. doi:10.1038/nature04008. PMID 16136135. S2CID 4423286.

- ^ Patterson, N.; Richter, D. J.; Gnerre, S.; Lander, E. S.; Reich, D. (June 2006). "Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature. 441 (7097): 1103–8. Bibcode:2006Natur.441.1103P. doi:10.1038/nature04789. PMID 16710306. S2CID 2325560.

- ^ Wakeley, J. (March 2008). "Complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature. 452 (7184): E3–4, discussion E4. Bibcode:2008Natur.452....3W. doi:10.1038/nature06805. PMID 18337768. S2CID 4367089.

Patterson et al. suggest that the apparently short divergence time between humans and chimpanzees on the X chromosome is explained by a massive interspecific hybridization event in the ancestry of these two species. However, Patterson et al. do not statistically test their own null model of simple speciation before concluding that speciation was complex, and—even if the null model could be rejected—they do not consider other explanations of a short divergence time on the X chromosome. These include natural selection on the X chromosome in the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, changes in the ratio of male-to-female mutation rates over time, and less extreme versions of divergence with gene flow. I therefore believe that their claim of hybridization is unwarranted.

- ^ King, Mary-Claire (1973). Protein polymorphisms in chimpanzee and human evolution (PhD). University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Wong, Kate (1 September 2014). "Tiny genetic differences between humans and other primates pervade the genome". Scientific American.

- ^ Minkel, J. R. (19 December 2006). "Humans and chimps: close but not that close". Scientific American.

- ^ Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why evolution is true. London: Penguin Books. pp. 202–204. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9.

After A. afarensis, the fossil record shows a confusing melange of gracile australopithecine species lasting up to about two million years ago. … [T]he late australopithecines, already bipedal, were beginning to show changes in teeth, skull, and brain that presage modern humans. It is very likely that the lineage that gave rise to modern humans included at least one of these species.

- ^ Cameron, D. W. (2003). "Early hominin speciation at the Plio/Pleistocene transition". HOMO: Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 54 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1078/0018-442x-00057. PMID 12968420.

- ^ Potts (2010). What does it mean to be human?. Washington: National Geographic Society. p. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-4262-0606-1.

- ^ Reynolds, Sally C.; Gallagher, Andrew (2012). African genesis: perspectives on hominin evolution. ISBN 9781107019959.

The discovery of Orrorin has ... radically modified interpretations of human origins and the environmental context in which the African apes/hominoid transition occurred, although ... the less likely hypothesis of derivation of Homo from the australopithecines still holds primacy in the minds of most palaeoanthropologists.

- ^ Potts (2010). What does it mean to be human?. Washington: National Geographic Society. p. 31–424. ISBN 978-1-4262-0606-1.

- ^ Brunet, M.; Guy, F.; Pilbeam, D.; et al. (July 2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa". Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969.

Sahelanthropus is the oldest and most primitive known member of the hominid clade, close to the divergence of hominids and chimpanzees.

- ^ Wolpoff, Milford; Senut, Brigitte; Pickford, Martin; Hawks, John (October 2002). "Sahelanthropus or 'Sahelpithecus'?" (PDF). Nature. 419 (6907): 581–582. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..581W. doi:10.1038/419581a. hdl:2027.42/62951. PMID 12374970. S2CID 205029762.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is an enigmatic new Miocene species, whose characteristics are a mix of those of apes and Homo erectus and which has been proclaimed by Brunet et al. to be the earliest hominid. However, we believe that features of the dentition, face and cranial base that are said to define unique links between this Toumaï specimen and the hominid clade are either not diagnostic or are consequences of biomechanical adaptations. To represent a valid clade, hominids must share unique defining features, and Sahelanthropus does not appear to have been an obligate biped.

외부 링크

- 휴먼 타임라인 (인터랙티브)– Smithsonian, 국립 자연사 박물관 (2016년 8월).