크레아틴

Creatine

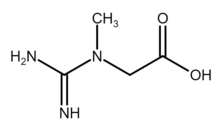

중성 형태의 크레아틴 골격 공식 | |

쌍성 이온 형태의 크레아틴 중 하나의 골격 공식 | |

쌍성이온 형태의 크레아틴의 볼 및 스틱 모델 | |

| 이름 | |

|---|---|

| 체계적인 IUPAC 이름 2-[카르바미미도일(메틸)아미노]아세트산 | |

| 기타명 N-카르바이미도일-N-메틸글리신; 메틸구아니도아세트산; N-아미디노사르코신 | |

| 식별자 | |

3D 모델(JSmol) | |

| 3DMet | |

| 907175 | |

| ChEBI | |

| CHEMBL | |

| 켐스파이더 | |

| 드럭뱅크 | |

| ECHA 인포카드 | 100.000.278 |

| EC 번호 |

|

| 240513 | |

| 케그 | |

| MeSH | 크레아틴 |

펍켐 CID | |

| RTECS 번호 |

|

| 유니 | |

CompTox 대시보드 (EPA) | |

| |

| |

| 특성. | |

| C4H9N3O2 | |

| 어금니 질량 | 131.135g·mol−1 |

| 외모 | 백정 |

| 냄새 | 무취 |

| 융점 | 255 °C (491 °F; 528 K) |

| 13.3 g L−1 (at 18 °C) | |

| 로그 P | −1.258 |

| 산도(pKa) | 3.429 |

| 기본성(pKb) | 10.568 |

| 등전점 | 8.47 |

| 열화학 | |

열용량 (C) | 171.1 J K−1 mol−1 (at 23.2 °C) |

표준 어금니 엔트로피 (S⦵298) | 189.5 J K−1 mol−1 |

스탕달피의 형성 (δ) | −538.06–−536.30 kJ mol−1 |

스탕달피의 연소 (δ) | −2.3239–−2.3223 MJ mol−1 |

| 약리학 | |

| C01EB06 (WHO) | |

| 약동학: | |

| 3시간 | |

| 위험성 | |

| GHS 라벨: | |

| |

| 경고문 | |

| H315, H319, H335 | |

| P261, P305+P351+P338 | |

| 관련 화합물 | |

관련 알칸산 | |

관련 화합물 | 디메틸아세트아미드 |

달리 명시된 경우를 제외하고 표준 상태의 재료에 대한 데이터가 제공됩니다(25°C [77°F], 100kPa). | |

크레아틴(/ˈ크리 ːə ti ː n/ 또는/ˈ크리 ːə t ɪ n/)은 공칭식을 갖는 유기 화합물입니다. (H2N)(HN)CN(CH3)CH2CO2H. 용액의 다양한 튜머(그 중 중성 형태 및 다양한 쌍성 이온 형태)에 존재합니다. 크레아틴은 척추동물에서 발견되며, 주로 근육과 뇌 조직에서 아데노신 삼인산(ATP)의 재활용을 촉진합니다. 재활용은 인산기의 기증을 통해 아데노신 이인산(ADP)을 ATP로 다시 전환함으로써 달성됩니다. 크레아틴은 완충 역할도 합니다.[2]

역사

크레아틴은 1832년 미셸 외젠 셰브룰(Michel Eugène Chevreul)이 골격근의 물 추출물에서 분리했을 때 처음으로 확인되었습니다. 그는 나중에 결정화된 침전물의 이름을 고기를 뜻하는 그리스어 κρέ α ς(kreas)에서 따왔습니다. 1928년 크레아틴은 크레아티닌과 평형 상태로 존재하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[3] 1920년대의 연구들은 많은 양의 크레아틴을 섭취해도 배설되지 않는다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 이 결과는 크레아틴을 저장하는 신체의 능력을 지적했으며, 이는 다시 식이 보충제로 사용할 것을 제안했습니다.[4]

1912년, 하버드 대학의 연구원 오토 폴린과 윌리 글로버 데니스는 크레아틴을 섭취하면 근육의 크레아틴 함량을 극적으로 높일 수 있다는 증거를 발견했습니다.[5][6] 1920년대 후반, 크레아틴을 정상량보다 더 많이 섭취함으로써 크레아틴의 근육 내 저장량이 증가할 수 있다는 것을 발견한 과학자들은 포스포크레아틴(크레아틴 인산염)을 발견했고, 크레아틴이 골격근 대사의 핵심 역할을 한다는 것을 밝혀냈습니다. 척추동물에서 자연적으로 형성됩니다.[7]

포스포크레아틴의[8][9] 발견은 1927년에 보고되었습니다.[10][11][9] 1960년대에 크레아틴 키나아제(CK)는 포스포크레아틴(PCR)을 사용하여 ADP를 인산화하여 ATP를 생성하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 따라서 PCr이 아닌 ATP가 근육 수축에 직접 소비됩니다. CK는 ATP/ADP 비율을 "완충"하기 위해 크레아틴을 사용합니다.[12]

크레아틴이 신체적 성과에 미치는 영향은 20세기 초부터 잘 기록되어 왔지만, 1992년 바르셀로나 올림픽 이후 대중에게 알려지게 되었습니다. 1992년 8월 7일 더 타임즈의 기사는 100미터 금메달을 딴 린포드 크리스티가 올림픽 전에 크레아틴을 사용했다고 보도했습니다(그러나 린포드 크리스티가 선수 생활 후반에 도핑으로 유죄 판결을 받았다는 것도 언급해야 합니다).[13] Bodybuilding Monthly의 한 기사는 400미터 허들에서 금메달을 딴 Sally Gunnell을 또 다른 크레아틴 사용자로 지목했습니다. 게다가, 타임즈는 또한 100미터 허들 선수인 콜린 잭슨이 올림픽 전에 크레아틴을 복용하기 시작했다고 언급했습니다.[14][15]

당시 영국에서는 효능이 낮은 크레아틴 보충제를 구입할 수 있었지만, 강도 향상을 위해 설계된 크레아틴 보충제는 1993년 실험 응용 과학(EAS)이라는 회사가 포스파젠이라는 이름으로 스포츠 영양 시장에 이 화합물을 선보이기 전까지는 상업적으로 구입할 수 없었습니다.[16] 그 후 수행된 연구에 따르면 크레아틴과 함께 높은 혈당 탄수화물을 섭취하면 크레아틴 근육 저장이 증가하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[17]

대사역할

크레아틴은 자연적으로 발생하는 비단백 화합물로 세포 내 ATP 재생에 사용되는 포스포크레아틴의 주성분입니다. 인체 전체 크레아틴과 인산염 저장고의 95%는 골격근에서 발견되고 나머지는 혈액, 뇌, 고환 및 기타 조직에 분포합니다.[18][19] 골격근의 전형적인 크레아틴 함량(크레아틴과 포스포크레아틴 모두)은 건조 근육량의 kg당 120 mmol이지만 보충을 통해 최대 160 mmol/kg에 도달할 수 있습니다.[20] 근육 내 크레아틴의 약 1-2%는 하루에 분해되고, 개인은 평균 (미보충) 크레아틴 저장을 유지하기 위해 하루에 약 1-3g의 크레아틴이 필요합니다.[20][21][22] 잡식성 식단은 이 값의 약 절반을 제공하고 나머지는 간과 신장에서 합성됩니다.[18][19][23]

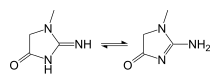

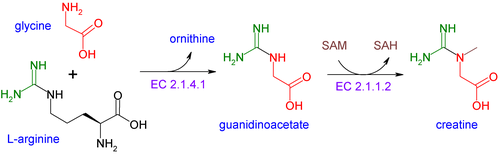

크레아틴은 필수 영양소가 아닙니다.[24] 아미노산 글리신과 아르기닌으로부터 인체 내에서 자연적으로 생성되는 아미노산 유도체로, S-아데노실 메티오닌(메티오닌의 유도체)이 구아니디노아세테이트를 크레아틴으로 전환하는 것을 촉매하는 데 추가적인 요구 사항이 있습니다. 생합성의 첫 번째 단계에서 효소 아르기닌:글리신 아미디노트랜스퍼라제(AGAT, EC:2.1.4.1)가 글리신과 아르기닌의 반응을 매개하여 구아니디노아세테이트를 형성합니다. 그런 다음 이 생성물은 S-아데노실 메티오닌을 메틸 공여체로 사용하여 구아니디노아세테이트 N-메틸트랜스퍼라제(GAMT, EC:2.1.1.2)에 의해 메틸화됩니다. 크레아틴 자체는 크레아틴 키나제에 의해 인산화되어 골격근과 뇌에서 에너지 완충제로 사용되는 포스포크레아틴을 형성할 수 있습니다. 크레아티닌이라고 불리는 크레아틴의 고리형 형태는 그것의 튜터와 크레아틴과 평형 상태로 존재합니다.

포스포크레아틴계

크레아틴은 혈액을 통해 운반되고 뇌와 골격근과 같은 에너지 요구량이 높은 조직에 의해 능동적인 운반 시스템을 통해 흡수됩니다. 골격근의 ATP 농도는 보통 2-5mM으로, 단 몇 초 만에 근육이 수축됩니다.[25] 에너지 요구량이 증가하는 시간 동안, 포스파젠(또는 ATP/PCR) 시스템은 효소 크레아틴 키나제(CK)에 의해 촉매되는 가역적인 반응을 통해 포스포크레아틴(PCR)을 사용하여 ADP로부터 ATP를 빠르게 재합성합니다. 인산기는 크레아틴의 NH 중심에 붙어 있습니다. 골격근에서 PCr 농도는 20-35 mM 이상에 이를 수 있습니다. 또한 대부분의 근육에서 CK의 ATP 재생 능력은 매우 높기 때문에 제한 요소가 아닙니다. ATP의 세포 농도는 작지만, ATP가 PCr과 CK의 큰 풀로부터 지속적이고 효율적으로 보충되기 때문에 변화를 감지하기가 어렵습니다.[25] 제안된 표현은 Krieder et al. 에 의해 설명되었습니다.[26] 크레아틴은 PCr의 근육 저장을 증가시키는 능력을 가지고 있으며, 잠재적으로 증가된 에너지 요구를 충족시키기 위해 ADP로부터 ATP를 재합성하는 근육의 능력을 증가시킵니다.[27][28][29]

크레아틴 보충은 위성 세포가 손상된 근육 섬유에 '기증'할 미오뉴클레오의 수를 증가시키는 것으로 보이며, 이는 이러한 섬유의 성장 가능성을 증가시킵니다. 이러한 미오뉴클레아티의 증가는 아마도 크레아틴이 미오제닉 전사 인자 MRF4의 수준을 증가시키는 능력에서 기인할 것입니다.[30]

유전적 결함

크레아틴 생합성 경로의 유전적 결핍은 다양한 심각한 신경학적 결함을 초래합니다.[31] 임상적으로 크레아틴 대사에는 세 가지 뚜렷한 장애가 있습니다. 두 합성 효소의 결핍은 GATM의 변이로 인한 L-아르기닌:글리신 아미디노트랜스퍼라제 결핍과 GAMT의 변이로 인한 구아니디노아세테이트 메틸트랜스퍼라제 결핍을 유발할 수 있습니다. 두 생합성 결함은 모두 상염색체 열성으로 유전됩니다. 세 번째 결함인 크레아틴 수송체 결함은 SLC6A8의 돌연변이에 의해 발생하고 X-연결 방식으로 유전됩니다. 이 상태는 크레아틴이 뇌로 전달되는 것과 관련이 있습니다.[32]

채식주의자

일부 연구에 따르면 총 근육 크레아틴은 채식주의자가 비채식주의자보다 현저히 낮습니다.[33][34][32][19] 이 발견은 아마도 잡식성 식단이 크레아틴의 주요 공급원이기 때문일 것입니다.[35] 락토오보 채식주의자와 비건의 근육 내 크레아틴 농도를 비채식주의자 수준까지 끌어올리기 위해서는 보충이 필요하다는 연구 결과가 나왔습니다.[33]

약동학

현재까지 크레아틴에 대한 연구는 대부분 크레아틴의 약리학적 특성에 초점을 맞추고 있지만 크레아틴의 약리학에 대한 연구는 부족한 실정입니다. 연구에 따르면 크레아틴의 임상 사용에 대한 약동학적 매개변수는 분포 부피, 간극, 생체 이용률, 평균 체류 시간, 흡수 속도 및 반감기와 같은 것으로 확립되지 않았습니다. 최적의 임상 투여 전에 명확한 약동학 프로파일을 설정해야 합니다.[36]

투약

적재단계

크레아틴 요구량은 체중에 따라 다를 수 있기 때문에 4개의 동일한 간격으로 나눈 대략 0.3g/kg/일이 제안되었습니다.[26][20] 또한 하루 3g의 저용량을 28일 동안 복용하면 6일 동안 급속 로딩 용량인 20g/일과 동일한 양으로 총 근육 크레아틴 저장량을 증가시킬 수 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[20] 그러나 28일 로딩 단계에서는 완전히 포화된 근육 저장 전까지 크레아틴 보충의 에르고제닉 이점이 실현되지 않습니다.

근육 크레아틴 저장의 이러한 증가는 연구 섹션에서 논의된 에르고제닉 이점과 상관관계가 있습니다. 그러나 크레아틴 합성 결핍을 상쇄하고 질병을 완화하기 위해 더 오랜 기간 동안 더 많은 용량이 연구되고 있습니다.[37][38][32]

유지보수단계

5-7일간의 로딩 단계 이후, 근육 크레아틴 저장소는 완전히 포화되고 보충제는 하루에 분해되는 크레아틴의 양을 충당하기만 하면 됩니다. 이 유지 용량은 원래 약 2-3 g/일(또는 0.03 g/kg/일)로 보고되었지만 [20]일부 연구에서는 포화 근육 크레아틴을 유지하기 위해 3-5 g/일 유지 용량을 제안했습니다.[17][22][39][40]

흡수.

건강한 성인의 내인성 혈청 또는 혈장 크레아틴 농도는 보통 2-12 mg/L 범위입니다. 건강한 성인에게 5g(5000mg)의 단일 경구 용량을 투여하면 섭취 후 1-2시간에 혈장 크레아틴 수치가 약 120mg/L로 최고치를 기록합니다. 크레아틴은 평균 3시간 미만으로 상당히 짧은 제거 반감기를 가지고 있으므로, 높아진 혈장 수준을 유지하기 위해서는 하루 동안 3-6시간마다 소량의 경구 투여를 해야 합니다.

없애기

크레아틴의 보충이 멈추면 근육 크레아틴 매장은 4-6주 안에 기준선으로 돌아오는 것으로 나타났습니다.[20][42][40]

운동과 운동

크레아틴 보충제는 에틸 에스테르, 글루코네이트, 1수화물 및 질산염 형태로 판매됩니다.[43]

스포츠 경기력 향상을 위한 크레아틴 보충제는 단기적인 사용에는 안전한 것으로 간주되지만 장기적인 사용 또는 어린이와 청소년에게 사용하기 위한 안전 데이터가 부족합니다.[44]

국제스포츠영양학회지의 2018년 리뷰 기사는 크레아틴 모노하이드레이트가 고강도 운동을 위한 에너지 가용성에 도움이 될 수 있다고 말했습니다.[45]

크레아틴을 사용하면 고강도 혐기성 반복 작업(작업 및 휴식 기간)에서 최대 출력과 성능을 5%에서 15%[46][47][48]까지 높일 수 있습니다. 크레아틴은 유산소 지구력에 큰 영향을 미치지 않지만 고강도 유산소 운동의 짧은 시간 동안 힘을 증가시킵니다.[49][obsolete source][50][obsolete source]

21,000명의 대학 운동선수를 대상으로 한 설문조사에서 14%의 운동선수가 경기력 향상을 위해 크레아틴 보충제를 복용하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[51] 운동을 하지 않는 사람들은 외모를 개선하기 위해 크레아틴 보충제를 복용하는 것을 보고합니다.[51]

조사.

인지수행능력

크레아틴은 뇌 기능과 인지 처리에 유익한 효과가 있는 것으로 보고되고 있지만, 그 증거는 체계적으로 해석하기 어렵고 적절한 용량을 알 수 없습니다.[52][53] 가장 큰 효과는 스트레스를 받거나 (예를 들어, 수면 부족으로 인해) 인지적으로 손상된 사람들에게서 나타나는 것으로 보입니다.[52][53]

2018년 체계적인 검토에 따르면 "일반적으로 크레아틴 투여에 의해 단기 기억력과 지능/추리력이 향상될 수 있다는 증거가 있는 반면, 다른 인지 영역의 경우 "결과가 상충되었다"고 합니다.[54] 또 다른 2023년 리뷰에서는 처음에 메모리 기능이 향상되었다는 증거를 발견했습니다.[55] 그러나 나중에 잘못된 통계가 통계적 유의성으로 이어진다는 것이 밝혀졌고 "이중 계산"을 수정한 후 그 효과는 노인에게만 유의했습니다.[56]

근육병

메타 분석에 따르면 크레아틴 치료는 근이영양증에서 근력을 증가시키고 잠재적으로 기능적 성능을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났습니다.[57] 크레아틴 치료는 대사성 근병증이 있는 사람의 근력을 개선하는 것으로 보이지 않습니다.[57] 많은 양의 크레아틴은 맥아들 병에 걸린 사람들이 복용할 때 근육통을 증가시키고 일상 생활의 활동에 장애를 일으킵니다.[57]

다양한 근이영양증을 가진 사람들을 대상으로 한 임상 연구에 따르면, 순수한 형태의 크레아틴 모노하이드레이트를 사용하면 부상 및 고정 후 재활에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[58]

미토콘드리아 질환

파킨슨병

크레아틴이 미토콘드리아 기능에 미치는 영향은 파킨슨병을 늦추는 효능과 안전성에 대한 연구로 이어졌습니다. 2014년 기준으로 편향의 위험, 작은 표본 크기, 짧은 시험 기간 등으로 인해 치료 결정에 대한 신뢰할 수 있는 근거를 제공하지 못했습니다.[59]

헌팅턴병

몇 가지 1차 연구는[60][61][62] 완료되었지만 헌팅턴병에 대한 체계적인 검토는 아직 완료되지 않았습니다.

ALS

근위축성 측삭경화증 치료제로는 효과가 없습니다.[63]

테스토스테론

2021년 연구에 대한 체계적인 검토에 따르면 "현재의 증거는 크레아틴 보충제가 총 테스토스테론, 유리 테스토스테론, DHT를 증가시키거나 탈모/신장을 유발한다는 것을 나타내지 않습니다."[64]

부작용

크레아틴 보충의 잘 문서화된 효과 중 하나는 보충 일정의 첫 주 내에 체중이 증가한다는 것인데, 이는 삼투압에 의한 근육 크레아틴 농도 증가로 인해 수분이 더 많이 유지되기 때문일 수 있습니다.[67]

2009년 체계적인 검토에 따르면 크레아틴 보충제가 수분 공급 상태와 내열성에 영향을 미치고 근육 경련과 설사를 유발할 수 있다는 우려가 신빙성이 없습니다.[68][69]

신기능

장기적인 크레아틴 보충은 신장 환자에게 안전성이 입증되지 않았습니다.[70]

국가신장재단이 발표한 2019년 체계적인 리뷰는 크레아틴 보충제가 신장 기능에 악영향을 미치는지 여부를 조사했습니다.[71] 그들은 1997년부터 2013년까지 크레아틴 4–20g/일의 표준 크레아틴 로딩 및 유지 프로토콜 대 위약을 조사한 15개의 연구를 확인했습니다. 그들은 신장 손상의 척도로 혈청 크레아티닌, 크레아티닌 클리어런스 및 혈청 요소 수치를 사용했습니다. 일반적으로 크레아틴 보충은 정상 한계 내에 유지되는 크레아티닌 수치를 약간 높이는 결과를 초래했지만 보충은 신장 손상을 유발하지 않았습니다(P 값 < 0.001). 2019년 체계적 검토에 포함된 특별 모집단에는 제2형 당뇨병 환자[72] 및 폐경 후 여성,[73] 보디빌더,[74] 운동선수,[75] 저항 훈련 인구가 포함되었습니다.[76][77][78] 이 연구는 또한 크레아틴이 신장 기능에 영향을 미친다는 보고가 있는 3개의 사례 연구에 대해 논의했습니다.[79][80][81]

미국 스포츠 의학 대학, 영양 및 식이요법 아카데미, 캐나다 영양사 간의 영양 전략 성능 향상에 대한 공동 성명에서 크레아틴은 에르고제닉 보조제 목록에 포함되었으며 사용 우려 사항으로 신장 기능을 나열하지 않습니다.[82]

국제스포츠영양학회지의 크레아틴에 대한 가장 최근의 입장은 크레아틴이 유아부터 노인, 운동선수에 이르기까지 건강한 인구를 섭취해도 안전하다고 말합니다. 그들은 또한 크레아틴을 장기간(5년) 사용하는 것이 안전한 것으로 간주되었다고 말합니다.[26]

정상적인 생리 기능을 위해서는 신장 자체가 포스포크레아틴과 크레아틴을 필요로 하며 실제로 신장은 상당한 양의 크레아틴 키나제(BB-CK 및 u-mtCK 동종효소)를 발현한다는 점을 언급하는 것이 중요합니다.[83] 동시에 내인성 크레아틴 합성을 위한 두 단계 중 첫 번째 단계는 신장 자체에서 이루어집니다. 신장 질환 환자와 투석 치료를 받는 환자는 일반적으로 장기에서 크레아틴 수치가 현저히 낮으며, 이는 병리학적 신장이 모두 크레아틴 합성 능력을 방해받고 원위 세뇨관의 소변에서 크레아틴을 역흡수하기 때문입니다. 또한 투석 환자는 투석 치료 자체에 의해 씻겨져 크레아틴이 소실되어 만성적으로 크레아틴이 고갈됩니다. 이러한 상황은 투석 환자들이 일반적으로 크레아틴의 소화원인 육류와 생선을 덜 섭취한다는 사실에 의해 악화됩니다. 따라서 이러한 환자의 만성 크레아틴 고갈을 완화하고 장기가 크레아틴 저장을 보충할 수 있도록 하기 위해 2017년 의학 가설 기사에서 투석 환자에게 여분의 크레아틴을, 바람직하게는 투석 내 투여에 의해 보충할 것을 제안했습니다. 투석 환자에서 크레아틴을 보충하면 근력, 운동의 조정, 뇌 기능이 향상되고 이러한 환자에게 흔히 발생하는 우울증과 만성 피로를 완화시켜 환자의 건강과 질이 크게 향상될 것으로 기대됩니다.[84][unreliable medical source?]

안전.

오염

2011년 이탈리아에서 시판 중인 33개의 보충제에 대한 조사에서 50% 이상이 적어도 하나의 오염 물질에서 유럽 식품 안전청의 권장 사항을 초과하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이러한 오염 물질 중 가장 널리 퍼진 것은 크레아티닌으로 신체에서도 생성되는 크레아티닌의 분해 산물입니다.[85] 크레아티닌은 샘플의 44%에서 유럽 식품 안전청의 권장 사항보다 고농도로 존재했습니다. 약 15%의 샘플에서 디하이드로-1,3,5-트리아진 또는 높은 디시안디아미드 농도가 검출 가능한 수준으로 나타났습니다. 중금속 오염은 문제가 되지 않았으며, 검출 가능한 수은 수준은 미미했습니다. 2007년에 검토한 두 가지 연구에서 불순물이 발견되지 않았습니다.[86]

상호작용

국립 보건원의 한 연구에 따르면 카페인은 크레아틴과 상호작용하여 파킨슨병의 진행 속도를 증가시킵니다.[87]

음식과 요리

크레아틴이 고온(148 °C 이상)에서 단백질과 설탕과 혼합되면, 그 결과 반응은 발암성 헤테로사이클릭 아민(HCAs)을 생성합니다.[88] 그런 반응은 고기를 굽거나 팬에 튀길 때 발생합니다.[89] 크레아틴 함량(조단백질의 백분율)은 육류 품질의 지표로 사용될 수 있습니다.[90]

식이요법 고려사항

크레아틴-모노하이드레이트는 보충제 생산에 사용되는 원료가 동물 유래가 없기 때문에 채식주의자와 비건에게 적합합니다.[91]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ Stout JR, Antonio J, Kalman E, eds. (2008). Essentials of Creatine in Sports and Health. Humana. ISBN 978-1-59745-573-2.

- ^ Barcelos RP, Stefanello ST, Mauriz JL, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Soares FA (2016). "Creatine and the Liver: Metabolism and Possible Interactions". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (1): 12–8. doi:10.2174/1389557515666150722102613. PMID 26202197.

The process of creatine synthesis occurs in two steps, catalyzed by L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) and guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (GAMT), which take place mainly in kidney and liver, respectively. This molecule plays an important energy/pH buffer function in tissues, and to guarantee the maintenance of its total body pool, the lost creatine must be replaced from diet or de novo synthesis.

- ^ Cannan RK, Shore A (1928). "The creatine-creatinine equilibrium. The apparent dissociation constants of creatine and creatinine". The Biochemical Journal. 22 (4): 920–9. doi:10.1042/bj0220920. PMC 1252207. PMID 16744118.

- ^ Volek JS, Ballard KD, Forsythe CE (2008). "Overview of Creatine Metabolism". In Stout JR, Antonio J, Kalman E (eds.). Essentials of Creatine in Sports and Health. Humana. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-59745-573-2.

- ^ Folin O, Denis W (1912). "Protein metabolism from the standpoint of blood and tissue analysis". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 12 (1): 141–61. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)88723-3. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Antonio, Jose (8 February 2021). "Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00412-w. PMC 7871530. PMID 33557850.

- ^ Brosnan JT, da Silva RP, Brosnan ME (May 2011). "The metabolic burden of creatine synthesis". Amino Acids. 40 (5): 1325–31. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0853-y. PMID 21387089. S2CID 8293857.

- ^ Saks V (2007). Molecular system bioenergetics: energy for life. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-527-31787-5.

- ^ a b Ochoa S (1989). Sherman EJ, National Academy of Sciences (eds.). David Nachmansohn. Biographical Memoirs. Vol. 58. National Academies Press. pp. 357–404. ISBN 978-0-309-03938-3.

- ^ Eggleton P, Eggleton GP (1927). "The Inorganic Phosphate and a Labile Form of Organic Phosphate in the Gastrocnemius of the Frog". The Biochemical Journal. 21 (1): 190–5. doi:10.1042/bj0210190. PMC 1251888. PMID 16743804.

- ^ Fiske CH, Subbarow Y (April 1927). "The nature of the 'inorganic phosphate' in voluntary muscle". Science. 65 (1686): 401–3. Bibcode:1927Sci....65..401F. doi:10.1126/science.65.1686.401. PMID 17807679.

- ^ Wallimann T (2007). "Introduction – Creatine: Cheap Ergogenic Supplement with Great Potential for Health and Disease". In Salomons GS, Wyss M (eds.). Creatine and Creatine Kinase in Health and Disease. Springer. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-4020-6486-9.

- ^ "Shadow over Christie's reputation".

- ^ "Supplement muscles in on the market". National Review of Medicine. 30 July 2004. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ Passwater RA (2005). Creatine. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-87983-868-3. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Stoppani J (May 2004). Creatine new and improved: recent high-tech advances have made creatine even more powerful. Here's how you can take full advantage of this super supplement. Muscle & Fitness. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ a b Green AL, Hultman E, Macdonald IA, Sewell DA, Greenhaff PL (November 1996). "Carbohydrate ingestion augments skeletal muscle creatine accumulation during creatine supplementation in humans". The American Journal of Physiology. 271 (5 Pt 1): E821-6. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.5.E821. PMID 8944667.

- ^ a b Cooper R, Naclerio F, Allgrove J, Jimenez A (July 2012). "Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 9 (1): 33. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-9-33. PMC 3407788. PMID 22817979.

Creatine is produced endogenously at an amount of about 1 g/d. Synthesis predominately occurs in the liver, kidneys, and to a lesser extent in the pancreas. The remainder of the creatine available to the body is obtained through the diet at about 1 g/d for an omnivorous diet. 95% of the bodies creatine stores are found in the skeletal muscle and the remaining 5% is distributed in the brain, liver, kidney, and testes [1].

- ^ a b c Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT (August 2016). "The role of dietary creatine". Amino Acids. 48 (8): 1785–91. doi:10.1007/s00726-016-2188-1. PMID 26874700. S2CID 3700484.

The daily requirement of a 70-kg male for creatine is about 2 g; up to half of this may be obtained from a typical omnivorous diet, with the remainder being synthesized in the body ... More than 90% of the body's creatine and phosphocreatine is present in muscle (Brosnan and Brosnan 2007), with some of the remainder being found in the brain (Braissant et al. 2011). ... Creatine synthesized in liver must be secreted into the bloodstream by an unknown mechanism (Da Silva et al. 2014a)

- ^ a b c d e f Hultman E, Söderlund K, Timmons JA, Cederblad G, Greenhaff PL (July 1996). "Muscle creatine loading in men". Journal of Applied Physiology. 81 (1): 232–7. doi:10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.232. PMID 8828669.

- ^ Balsom PD, Söderlund K, Ekblom B (October 1994). "Creatine in humans with special reference to creatine supplementation". Sports Medicine. 18 (4): 268–80. doi:10.2165/00007256-199418040-00005. PMID 7817065. S2CID 23929060.

- ^ a b Harris RC, Söderlund K, Hultman E (September 1992). "Elevation of creatine in resting and exercised muscle of normal subjects by creatine supplementation". Clinical Science. 83 (3): 367–74. doi:10.1042/cs0830367. PMID 1327657.

- ^ Brosnan JT, da Silva RP, Brosnan ME (May 2011). "The metabolic burden of creatine synthesis". Amino Acids. 40 (5): 1325–31. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0853-y. PMID 21387089. S2CID 8293857.

Creatinine loss averages approximately 2 g (14.6 mmol) for 70 kg males in the 20- to 39-year age group. ... Table 1 Comparison of rates of creatine synthesis in young adults with dietary intakes of the three precursor amino acids and with the whole body transmethylation flux

Creatine synthesis (mmol/day) 8.3 - ^ "Creatine". Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ a b Wallimann T, Wyss M, Brdiczka D, Nicolay K, Eppenberger HM (January 1992). "Intracellular compartmentation, structure and function of creatine kinase isoenzymes in tissues with high and fluctuating energy demands: the 'phosphocreatine circuit' for cellular energy homeostasis". The Biochemical Journal. 281 ( Pt 1) (Pt 1): 21–40. doi:10.1042/bj2810021. PMC 1130636. PMID 1731757.

- ^ a b c Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, Ziegenfuss TN, Wildman R, Collins R, et al. (2017). "International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 14: 18. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z. PMC 5469049. PMID 28615996.

- ^ Spillane M, Schoch R, Cooke M, Harvey T, Greenwood M, Kreider R, Willoughby DS (February 2009). "The effects of creatine ethyl ester supplementation combined with heavy resistance training on body composition, muscle performance, and serum and muscle creatine levels". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 6 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-6-6. PMC 2649889. PMID 19228401.

- ^ Wallimann T, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Schlattner U (May 2011). "The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine". Amino Acids. 40 (5): 1271–96. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0877-3. PMC 3080659. PMID 21448658..

- ^ T. 왈리만, M. 토카르스카-슐라트너, D. 노이만 u. a.: 인산염 회로: 크레아틴 키나제의 분자 및 세포 생리학, 활성산소에 대한 민감성 및 크레아틴 보충에 의한 증진. In: Molecular System Bioenergics: 생명을 위한 에너지. 22. November 2007. doi:10.1002/9783527621095.ch7C

- ^ Hespel P, Eijnde BO, Derave W, Richter EA (2001). "Creatine supplementation: exploring the role of the creatine kinase/phosphocreatine system in human muscle". Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 26 Suppl: S79-102. doi:10.1139/h2001-045. PMID 11897886.

- ^ "L-Arginine:Glycine Amidinotransferase". Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Braissant O, Henry H, Béard E, Uldry J (May 2011). "Creatine deficiency syndromes and the importance of creatine synthesis in the brain" (PDF). Amino Acids. 40 (5): 1315–24. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0852-z. PMID 21390529. S2CID 13755292. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ a b Burke DG, Chilibeck PD, Parise G, Candow DG, Mahoney D, Tarnopolsky M (November 2003). "Effect of creatine and weight training on muscle creatine and performance in vegetarians". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 35 (11): 1946–55. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000093614.17517.79. PMID 14600563.

- ^ Benton D, Donohoe R (April 2011). "The influence of creatine supplementation on the cognitive functioning of vegetarians and omnivores". The British Journal of Nutrition. 105 (7): 1100–5. doi:10.1017/S0007114510004733. PMID 21118604.

- ^ Solis MY, Artioli GG, Gualano B (2017). "Effect of age, diet, and tissue type on PCr response to creatine supplementation". Journal of Applied Physiology. 23 (2): 407–414. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00248.2017. PMID 28572496.

- ^ Persky AM, Brazeau GA (June 2001). "Clinical pharmacology of the dietary supplement creatine monohydrate". Pharmacological Reviews. 53 (2): 161–76. PMID 11356982.

- ^ Hanna-El-Daher L, Braissant O (August 2016). "Creatine synthesis and exchanges between brain cells: What can be learned from human creatine deficiencies and various experimental models?". Amino Acids. 48 (8): 1877–95. doi:10.1007/s00726-016-2189-0. PMID 26861125. S2CID 3675631.

- ^ Bender A, Klopstock T (August 2016). "Creatine for neuroprotection in neurodegenerative disease: end of story?". Amino Acids. 48 (8): 1929–40. doi:10.1007/s00726-015-2165-0. PMID 26748651. S2CID 2349130.

- ^ Kreider RB (February 2003). "Effects of creatine supplementation on performance and training adaptations". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 244 (1–2): 89–94. doi:10.1023/A:1022465203458. PMID 12701815. S2CID 35050122.

- ^ a b Greenhaff PL, Casey A, Short AH, Harris R, Soderlund K, Hultman E (May 1993). "Influence of oral creatine supplementation of muscle torque during repeated bouts of maximal voluntary exercise in man". Clinical Science. 84 (5): 565–71. doi:10.1042/cs0840565. PMID 8504634.

- ^ Jäger R, Harris RC, Purpura M, Francaux M (November 2007). "Comparison of new forms of creatine in raising plasma creatine levels". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 4: 17. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-4-17. PMC 2206055. PMID 17997838.

- ^ Vandenberghe K, Goris M, Van Hecke P, Van Leemputte M, Vangerven L, Hespel P (December 1997). "Long-term creatine intake is beneficial to muscle performance during resistance training". Journal of Applied Physiology. 83 (6): 2055–63. doi:10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.2055. PMID 9390981. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Cooper R, Naclerio F, Allgrove J, Jimenez A (July 2012). "Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 9 (1): 33. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-9-33. PMC 3407788. PMID 22817979.

- ^ Butts J, Jacobs B, Silvis M (2018). "Creatine Use in Sports". Sports Health. 10 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1177/1941738117737248. PMC 5753968. PMID 29059531.

- ^ Kerksick CM, Wilborn CD, Roberts MD, Smith-Ryan A, Kleiner SM, Jäger R, et al. (August 2018). "ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 15 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y. PMC 6090881. PMID 30068354.

- ^ Bemben MG, Lamont HS (2005). "Creatine supplementation and exercise performance: recent findings". Sports Medicine. 35 (2): 107–25. doi:10.2165/00007256-200535020-00002. PMID 15707376. S2CID 57734918.

- ^ Bird SP (December 2003). "Creatine supplementation and exercise performance: a brief review". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2 (4): 123–32. PMC 3963244. PMID 24688272.

- ^ Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F (September 2015). "Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses". Sports Medicine. 45 (9): 1285–1294. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0337-4. PMID 25946994. S2CID 7372700.

- ^ Engelhardt M, Neumann G, Berbalk A, Reuter I (July 1998). "Creatine supplementation in endurance sports". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 30 (7): 1123–9. doi:10.1097/00005768-199807000-00016. PMID 9662683.

- ^ Graham AS, Hatton RC (1999). "Creatine: a review of efficacy and safety". Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 39 (6): 803–10, quiz 875–7. doi:10.1016/s1086-5802(15)30371-5. PMID 10609446.

- ^ a b "Office of Dietary Supplements - Dietary Supplements for Exercise and Athletic Performance". Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ a b Dolan, Eimear; Gualano, Bruno; Rawson, Eric S. (2 January 2019). "Beyond muscle: the effects of creatine supplementation on brain creatine, cognitive processing, and traumatic brain injury". European Journal of Sport Science. 19 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644. ISSN 1746-1391. PMID 30086660. S2CID 51936612. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ a b Rawson, Eric S.; Venezia, Andrew C. (May 2011). "Use of creatine in the elderly and evidence for effects on cognitive function in young and old". Amino Acids. 40 (5): 1349–1362. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9. ISSN 0939-4451. PMID 21394604. S2CID 11382225. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Avgerinos, K. I.; Spyrou, N.; Bougioukas, K. I.; Kapogiannis, D. (2018). "Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Experimental Gerontology. 108: 166–173. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2018.04.013. PMC 6093191. PMID 29704637.

- ^ Prokopidis, Konstantinos; Giannos, Panagiotis; Triantafyllidis, Konstantinos K.; Kechagias, Konstantinos S.; Forbes, Scott C.; Candow, Darren G. (2023). "Effects of creatine supplementation on memory in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Nutrition Reviews. 81 (4): 416–27. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuac064. PMC 9999677. PMID 35984306.

- ^ Prokopidis, Konstantinos; Giannos, Panagiotis; Triantafyllidis, Konstantinos K; Kechagias, Konstantinos S; Forbes, Scott C; Candow, Darren G (16 January 2023). "Author's reply: Letter to the Editor: Double counting due to inadequate statistics leads to false-positive findings in "Effects of creatine supplementation on memory in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials"". Nutrition Reviews. 81 (11): 1497–1500. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuac111. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Kley RA, Tarnopolsky MA, Vorgerd M (June 2013). "Creatine for treating muscle disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD004760. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004760.pub4. PMC 6492334. PMID 23740606.

- ^ Walter MC, Lochmüller H, Reilich P, Klopstock T, Huber R, Hartard M, et al. (May 2000). "Creatine monohydrate in muscular dystrophies: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study". Neurology. 54 (9): 1848–50. doi:10.1212/wnl.54.9.1848. PMID 10802796. S2CID 13304657.

- ^ Xiao Y, Luo M, Luo H, Wang J (June 2014). "Creatine for Parkinson's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (6): CD009646. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009646.pub2. PMC 10196714. PMID 24934384.

- ^ Verbessem P, Lemiere J, Eijnde BO, Swinnen S, Vanhees L, Van Leemputte M, et al. (October 2003). "Creatine supplementation in Huntington's disease: a placebo-controlled pilot trial". Neurology. 61 (7): 925–30. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000090629.40891.4b. PMID 14557561. S2CID 43845514.

- ^ Bender A, Auer DP, Merl T, Reilmann R, Saemann P, Yassouridis A, et al. (January 2005). "Creatine supplementation lowers brain glutamate levels in Huntington's disease". Journal of Neurology. 252 (1): 36–41. doi:10.1007/s00415-005-0595-4. PMID 15672208. S2CID 17861207.

- ^ Hersch SM, Schifitto G, Oakes D, Bredlau AL, Meyers CM, Nahin R, Rosas HD (August 2017). "The CREST-E study of creatine for Huntington disease: A randomized controlled trial". Neurology. 89 (6): 594–601. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004209. PMC 5562960. PMID 28701493.

- ^ Pastula DM, Moore DH, Bedlack RS (December 2012). "Creatine for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD005225. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005225.pub3. PMID 23235621.

- ^ Antonio, J.; Candow, D. G.; Forbes, S. C.; Gualano, B.; Jagim, A. R.; Kreider, R. B.; Rawson, E. S.; Smith-Ryan, A. E.; Vandusseldorp, T. A.; Willoughby, D. S.; Ziegenfuss, T. N. (2021). "Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18 (13): 13. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00412-w. PMC 7871530. PMID 33557850.

- ^ Francaux M, Poortmans JR (December 2006). "Side effects of creatine supplementation in athletes". International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 1 (4): 311–23. doi:10.1123/ijspp.1.4.311. PMID 19124889. S2CID 21330062.

- ^ Buford TW, Kreider RB, Stout JR, Greenwood M, Campbell B, Spano M, et al. (August 2007). "International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: creatine supplementation and exercise". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 4. jissn: 6. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-4-6. PMC 2048496. PMID 17908288.

- ^ Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, Ziegenfuss TN, Wildman R, Collins R, et al. (13 June 2017). "International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 14: 18. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z. PMC 5469049. PMID 28615996.

- ^ Lopez RM, Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Ganio MS, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM (2009). "Does creatine supplementation hinder exercise heat tolerance or hydration status? A systematic review with meta-analyses". Journal of Athletic Training. 44 (2): 215–23. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.215. PMC 2657025. PMID 19295968.

- ^ Dalbo VJ, Roberts MD, Stout JR, Kerksick CM (July 2008). "Putting to rest the myth of creatine supplementation leading to muscle cramps and dehydration". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (7): 567–73. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.042473. PMID 18184753. S2CID 12920206. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Farquhar, William B.; Zambraski, Edward J. (2002). "Effects of creatine use on the athlete's kidney". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 1 (2): 103–106. doi:10.1249/00149619-200204000-00007. PMID 12831718.

- ^ de Souza E, Silva A, Pertille A, Reis Barbosa CG, Aparecida de Oliveira Silva J, de Jesus DV, et al. (November 2019). "Effects of Creatine Supplementation on Renal Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Renal Nutrition. 29 (6): 480–489. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2019.05.004. PMID 31375416. S2CID 199388424.

- ^ Gualano B, de Salles Painelli V, Roschel H, Lugaresi R, Dorea E, Artioli GG, et al. (May 2011). "Creatine supplementation does not impair kidney function in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 111 (5): 749–56. doi:10.1007/s00421-010-1676-3. PMID 20976468. S2CID 21335546.

- ^ Neves M, Gualano B, Roschel H, Lima FR, Lúcia de Sá-Pinto A, Seguro AC, et al. (June 2011). "Effect of creatine supplementation on measured glomerular filtration rate in postmenopausal women". Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 36 (3): 419–22. doi:10.1139/h11-014. PMID 21574777.

- ^ Lugaresi R, Leme M, de Salles Painelli V, Murai IH, Roschel H, Sapienza MT, et al. (May 2013). "Does long-term creatine supplementation impair kidney function in resistance-trained individuals consuming a high-protein diet?". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 10 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-10-26. PMC 3661339. PMID 23680457.

- ^ Kreider RB, Melton C, Rasmussen CJ, Greenwood M, Lancaster S, Cantler EC, et al. (February 2003). "Long-term creatine supplementation does not significantly affect clinical markers of health in athletes". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 244 (1–2): 95–104. doi:10.1023/A:1022469320296. PMID 12701816. S2CID 25947100.

- ^ Cancela P, Ohanian C, Cuitiño E, Hackney AC (September 2008). "Creatine supplementation does not affect clinical health markers in football players". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (9): 731–5. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.030700. PMID 18780799. S2CID 20876433.

- ^ Carvalho AP, Molina GE, Fontana KE (August 2011). "Creatine supplementation associated with resistance training does not alter renal and hepatic functions". Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 17 (4): 237–241. doi:10.1590/S1517-86922011000400004. ISSN 1517-8692.

- ^ Mayhew DL, Mayhew JL, Ware JS (December 2002). "Effects of long-term creatine supplementation on liver and kidney functions in American college football players". International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. 12 (4): 453–60. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.12.4.453. PMID 12500988.

- ^ Thorsteinsdottir B, Grande JP, Garovic VD (October 2006). "Acute renal failure in a young weight lifter taking multiple food supplements, including creatine monohydrate". Journal of Renal Nutrition. 16 (4): 341–5. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2006.04.025. PMID 17046619.

- ^ Taner B, Aysim O, Abdulkadir U (February 2011). "The effects of the recommended dose of creatine monohydrate on kidney function". NDT Plus. 4 (1): 23–4. doi:10.1093/ndtplus/sfq177. PMC 4421632. PMID 25984094.

- ^ Barisic N, Bernert G, Ipsiroglu O, Stromberger C, Müller T, Gruber S, et al. (June 2002). "Effects of oral creatine supplementation in a patient with MELAS phenotype and associated nephropathy". Neuropediatrics. 33 (3): 157–61. doi:10.1055/s-2002-33679. PMID 12200746. S2CID 9250579.

- ^ Rodriguez NR, Di Marco NM, Langley S (March 2009). "American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 41 (3): 709–31. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31890eb86. PMID 19225360.

- ^ ML.Guerrero, J.베론, B.스핀들러, P.그로스커트, T.왈리만과 F.베리.근치적으로 투과되는 A6 신장 세포 상피에서 Na+ 펌프의 대사적 지지: 크레아틴 키나제의 역할.인: 제이피올입니다. 1997 Feb;272(2 Pt 1):C697-706. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C697, PMID 9124314

- ^ T. Wallimann, U. Riek, M. M. Möddel: 투석 중 크레아틴 보충제: 투석 환자의 건강과 삶의 질 향상을 위한 과학적 근거.In: 의학적 가설 2017년 2월 99일, S. 1-14. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2016.12.002, PMID 28110688.

- ^ Moreta S, Prevarin A, Tubaro F (June 2011). "Levels of creatine, organic contaminants and heavy metals in creatine dietary supplements". Food Chemistry. 126 (3): 1232–1238. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.028.

- ^ Persky AM, Rawson ES (2007). "Safety of Creatine Supplementation". Creatine and Creatine Kinase in Health and Disease. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 46. pp. 275–89. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6486-9_14. ISBN 978-1-4020-6485-2. PMID 18652082.

- ^ Simon DK, Wu C, Tilley BC, Wills AM, Aminoff MJ, Bainbridge J, et al. (2015). "Caffeine and Progression of Parkinson Disease: A Deleterious Interaction With Creatine". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 38 (5): 163–9. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000102. PMC 4573899. PMID 26366971.

- ^ "Heterocyclic Amines in Cooked Meats". National Cancer Institute. 15 September 2004. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ "Chemicals in Meat Cooked at High Temperatures and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Dahl O (1 July 1963). "Meat Quality Measurement, Creatine Content as an Index of Quality of Meat Products". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 11 (4): 350–355. doi:10.1021/jf60128a026.

- ^ Gießing J (20 February 2019). Kreatin: Eine natürliche Substanz und ihre Bedeutung für Muskelaufbau, Fitness und Anti-Aging. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 135–136, 207. ISBN 9783752803969. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2021.