그린란드 빙상

Greenland ice sheet| 그린란드 빙상 | |

|---|---|

| 그뢴란드 인들란디스 세르메르수아크 | |

| |

| 유형 | 빙상 |

| 좌표 | 76°42'N 41°12'W / 76.7°N 41.2°W[1] |

| 지역 | 1,710,000 km2 (660,000 sq mi)[2] |

| 길이 | 2,400 km (1,500 mi)[1] |

| 폭 | 1,100 km (680 mi)[1] |

| 두께 | 1.67km(1.0mi)(평균), ~3.5km(2.2mi)(최대)[2] |

그린란드 빙상은 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 얼음을 형성하는 빙상입니다. 두께는 평균 1.67 km (1.0 mi), 두께는 최대 3 km (1.9 mi)가 넘습니다.[2] 남북 방향으로 거의 2,900km(1,800mi) 길이이며, 북쪽 가장자리 부근의 위도 77°N에서 최대 너비는 1,100km(680mi)입니다.[1] 이 빙하는 그린란드 표면의 약 80%, 즉 남극 대륙 빙하 면적의 약 12%인 1,710,000 평방 킬로미터를 덮고 있습니다.[2] 과학 문헌에서 '그린랜드 빙상'이라는 용어는 종종 GIS 또는 GrIS로 단축됩니다.[3][4][5][6]

그린란드는 적어도 1800만년 동안 주요 빙하와 만년설을 가지고 있었지만,[7] 약 260만년 전에 하나의 빙하가 처음으로 그 섬의 대부분을 덮었습니다.[8] 그 이후로 크게 성장하고[9][10] 위축되었습니다.[11][12][13] 그린란드에서 가장 오래된 것으로 알려진 얼음은 약 100만년 전의 것입니다.[14] 인위적인 온실가스 배출로 인해 빙상은 현재 지난 1000년 동안 가장 따뜻하며 [15]적어도 지난 12,000년 동안 가장 빠른 속도로 얼음을 잃어가고 있습니다.[16]

여름마다 지표면의 일부가 녹고, 얼음 절벽이 바다로 갈라집니다. 일반적으로 빙상은 겨울 강설에 의해 보충됩니다.[4] 하지만 지구 온난화로 인해 빙하는 1850년 이전보다 2배에서 5배 더 빨리 녹고 [17]있으며 1996년 이후로 강설량이 따라가지 못하고 있습니다.[18] 2°C(3.6°F) 이하로 유지하는 파리 협정 목표가 달성된다면 그린란드 얼음의 용해만으로도 여전히 추가될 것입니다. 세기말까지 지구 해수면 상승에 6cm(2+1⁄2인치) 배출량이 줄어들지 않으면 2100년까지 용융으로 약 13cm(5인치)가 추가되며,[19]: 1302 최악의 경우 약 33cm(13인치)가 됩니다.[20] 비교하자면, 1972년 이래로 지금까지 용융은 1.4 cm (1 ⁄ 2 인치)를 기여한 반면, 1901년부터 2018년 사이에 모든 출처의 해수면 상승은 15-25 cm (6-10 인치)였습니다.

만약 2,900,000 입방 킬로미터(69만 6,000 입방 킬로미터)의 빙하가 모두 녹는다면, 이는 지구의 해수면을 ~7.4 미터(24 피트) 증가시킬 것입니다.[2] 1.7 °C (3.1 °F)에서 2.3 °C (4.1 °F) 사이의 지구 온난화는 이 용해를 피할 수 없게 만들 것입니다.[6] 그러나 1.5°C(2.7°F)는 여전히 해수면 상승의 1.4m(4+1 ⁄ 2ft)에 해당하는 얼음 손실을 초래하며, 온도가 감소하기 전에 그 수준을 초과하면 더 많은 얼음이 손실됩니다. 지구 온도가 계속해서 상승한다면, 빙상은 1,000년에서[20] 1만년 이내에 사라질 수도 있습니다.[24][25]

묘사

빙상은 빙하화 과정을 통해 형성되는데, 이 과정에서 현지 기후가 충분히 차가워서 매년 눈이 쌓일 수 있습니다. 매년 쌓인 눈 층이 쌓이면서, 눈의 무게는 수백 년에 걸쳐 점점 더 깊은 곳의 눈을 압축하여 굳힌 다음 단단한 빙하 얼음으로 압축됩니다.[13] 그린란드에서 빙상이 형성되자, 그 크기는 현재 상태와 비슷하게 유지되었습니다.[26] 그러나 그린란드 역사상 빙상이 현재의 경계를 넘어 120 km (75 mi)까지 확장된 기간은 11번 있었고, 마지막 기간은 약 100만 년 전이었습니다.[9][10]

얼음의 무게로 인해 산과 같은 충분히 큰 장애물에 의해 정지되지 않는 한 얼음은 천천히 "흐르게" 됩니다.[13] 그린란드는 해안선 근처에 많은 산이 있는데, 이것은 보통 빙하가 북극해로 더 이상 흘러 들어가는 것을 막습니다. 이전의 11번의 빙하기 에피소드는 빙하가 그 산들 위로 흐를 수 있을 정도로 충분히 커졌기 때문에 주목할 만합니다.[9][10] 오늘날 빙상의 북서쪽과 남동쪽 가장자리는 출구 빙하를 통해 빙상이 바다로 흘러나올 수 있을 정도로 산에 충분한 틈이 있는 주요 지역입니다. 이 빙하들은 정기적으로 얼음 조각이라고 알려진 곳에서 얼음을 흘립니다.[28] 석회화되고 녹고 있는 얼음 싱크에서 방출된 퇴적물이 해저에 쌓이고 프램 해협과 같은 곳에서 나온 퇴적물 코어는 그린란드의 빙하에 대한 긴 기록을 제공합니다.[7]

지질사

지난 1,800만 년의 대부분 동안 그린란드에 큰 빙하가 있었다는 증거가 있지만,[7] 이 얼음체들은 아마도 주변 주변 76,000 평방 킬로미터와 100,000 평방 킬로미터(29,000 평방 마일과 39,000 평방 마일)를 차지하는 마니소크와 플레이드 이스블링크와 같은 다양한 더 작은 현대 사례들과 유사했을 것입니다. 그린란드의 조건은 처음에는 하나의 일관된 빙상이 발달하기에 적합하지 않았지만, 이것은 약 1,000만년 전, 현재 서부와 동부 그린란드의 고지대를 형성하는 두 개의 수동적인 대륙 가장자리가 융기를 경험했던 중신세 동안에 변하기 시작했습니다. 그리고 궁극적으로 해발 2000~3000m 높이의 상부 평면을 형성했습니다.[29][30]

나중에 융기된 플라이오세 동안 해발 500~1000미터에서 더 낮은 평면을 형성했습니다. 융기의 세 번째 단계는 평면 표면 아래에 여러 개의 계곡과 피오르를 만들었습니다. 이 융기는 지형 강수량 증가와 더 낮은 표면 온도로 인해 빙하가 심화되어 얼음이 축적되고 지속될 수 있도록 합니다.[29][30] 최근 300만 년 전, 플리오세 온난기 동안 그린란드의 얼음은 동쪽과 남쪽의 가장 높은 봉우리에 국한되었습니다.[31] 얼음 덮개는 [8]그 이후로 점차 확장되어 270만년에서 260만년 전 대기의 이산화탄소 수치가 280에서 320ppm 사이로 떨어졌을 때까지 온도가 서로 다른 얼음 덮개가 섬 대부분을 연결하고 덮을 수 있을 정도로 충분히 떨어졌습니다.[3]

빙심 및 퇴적물 시료

빙상의 바닥은 지열 활동으로 인해 충분히 따뜻해서 그 아래에 액체 상태의 물이 있을 수 있습니다.[33] 이 액체 상태의 물은, 그 위에 있는 얼음의 무게로부터 압력을 받아, 침식을 일으킬 수 있고, 결국에는 빙상 아래에 기반암만 남게 됩니다. 하지만, 그린란드 빙상의 일부는 정상 부근에 있는데, 이 빙상은 땅에 단단히 얼어붙은 얼음의 기초층 위를 미끄러져 내려와 고대의 토양을 보존하고 있으며, 시추를 통해 이를 회수할 수 있습니다. 가장 오래된 이러한 토양은 약 270만 년 동안 지속적으로 얼음으로 덮여 있었고,[13] 정상에서 3킬로미터(1.9마일) 떨어진 또 다른 깊은 얼음 핵은 약 1,000,000년 된 얼음을 드러냈습니다.[14]

래브라도 해의 퇴적물 샘플은 거의 모든 그린란드 남부 얼음이 400,000년 전에 해양 동위원소 단계 11 동안 녹았다는 증거를 제공합니다.[11][34] 그린란드 북서부의 캠프 센추리에서 채취한 다른 얼음 코어 샘플은 그곳의 얼음이 플라이스토세 기간인 지난 140만 년 동안 적어도 한 번은 녹았고 적어도 280,000년 동안 돌아오지 않았음을 보여줍니다.[12] 이러한 발견은 기온이 산업화 이전의 조건보다 2.5 °C (4.5 °F) 미만으로 따뜻했던 지질학적으로 최근 기간 동안 현재 빙상 부피의 10% 미만이 남아 있었다는 것을 시사합니다. 이것은 기후 모델이 일반적으로 그러한 조건에서 고체 얼음의 지속적인 존재를 시뮬레이션하는 방법과 모순됩니다.[35][13] 1989년에서 1993년 사이 그린란드 빙상 정상까지 시추된 3km(1.9mi) 길이의 얼음 코어에서 얻은 ~100,000년 기록을 분석한 결과, 지질학적으로 기후의 급격한 변화에 대한 증거를 제공했으며, 대서양 자오선 역전 순환(AMOC)과 같은 티핑 포인트에 대한 연구를 알려주었습니다.[36]

얼음 코어는 빙하의 과거 상태와 다른 종류의 고기후 데이터에 대한 귀중한 정보를 제공합니다. 얼음 핵에 있는 물 분자의 산소 동위원소 구성의 미묘한 차이는 당시 물 주기에 대한 중요한 정보를 밝힐 수 있는 반면,[37] 얼음 핵 내에 얼어붙은 기포는 시간에 따른 가스 및 대기 입자 구성의 스냅샷을 제공합니다.[38][39]얼음 코어는 적절하게 분석되면 과거의 기온 기록,[37] 강수량 패턴,[40] 화산 폭발,[41] 태양 변화,[38] 해양 1차 생산량,[39] 심지어 토양 식생 피복 및 관련 산불 발생 빈도의 변화를 재구성하는 데 적합한 풍부한 프록시를 제공합니다.[42] 그린란드에서 온 얼음 핵은 고대 그리스와[43] 로마 제국 시대의 납 생산과 같은 인간의 영향도 기록하고 있습니다.[44]

최근 용융

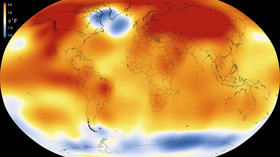

1960년대부터 1980년대까지 그린란드 남부를 포함한 북대서양의 한 지역은 세계에서 온난화보다는 냉각을 보여주는 몇 안 되는 지역 중 하나였습니다.[45][46] 이 위치는 1930년대와 1940년대에 직전 또는 직후 수십 년 동안보다 상대적으로 따뜻했습니다.[47] 보다 완전한 데이터 세트는 동시에 관찰된 북극 해빙 감소에 따라 1900년[48](산업혁명이 시작되고 지구 이산화탄소 수준에[49] 미치는 영향이 훨씬 후)부터 시작되는 온난화 및 얼음 손실 추세와 1979년경부터 시작되는 강한 온난화 추세를 확립했습니다.[50] 1995-1999년, 그린란드 중부는 1950년대보다 이미 2 °C (3.6 °F) 더 따뜻했습니다. 1991년과 2004년 사이에 스위스 캠프라는 한 곳의 겨울 평균 기온은 거의 6°C (11°F) 상승했습니다.[51]

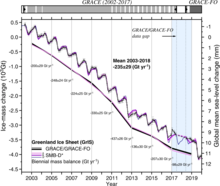

이러한 온난화와 일관되게, 1970년대는 그린란드 빙상이 성장한 마지막 10년으로, 매년 약 47기가톤이 증가했습니다. 1980년부터 1990년까지 연평균 51 Gt/y의 질량 감소가 있었습니다.[21] 1990-2000년 기간 동안 연평균 41Gt/y의 손실을 보였으며,[21] 1996년은 그린란드 빙상이 순 질량 증가를 보인 마지막 해였습니다. 2022년 현재, 그린란드 빙상은 26년 연속으로 얼음이 사라지고 있으며,[18] 지난 천 년 동안 기온이 가장 높았는데, 20세기 평균보다 약 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) 더 따뜻했습니다.[15]

빙상 성장 또는 감소의 순 비율은 여러 요인에 의해 결정됩니다. 다음은 다음과 같습니다.

- 중심부와 그 주변의 눈의 축적 및 융해 속도

- 시트의 가장자리를 따라 얼음이 녹는 것

- 출구 빙하로부터 또한 시트의 가장자리를 따라 바다로 갈라지는 얼음

2001년 IPCC 제3차 평가 보고서가 발표되었을 때, 현재까지의 관측 결과를 분석한 결과 연간 520 ± 26기가톤의 얼음 축적이 297 ± 32 Gt/yr 및 32 ± 3 Gt/yr의 얼음 손실에 해당하는 유출 및 바닥 용융, 235 ± 33 Gt/yr의 빙산 생산에 의해 상쇄되었으며 연간 -44 ± 53 기가톤의 순손실이 발생한 것으로 나타났습니다.[52]

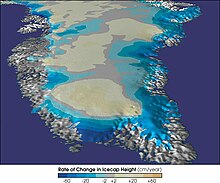

그린란드 빙상으로 인한 연간 얼음 손실은 2000년대에 가속화되어 2000-2010년에는 ~187Gt/yr에 도달했으며 2010-2018년에는 평균 연간 286Gt의 질량 손실이 발생했습니다. 관측된 빙상의 순 손실의 절반(1992년에서 2018년 사이에 얼음 3,902기가톤(Gt), 즉 전체 질량의[53] 약 0.13%)이 8년 동안 발생했습니다. 해수면 상승에 해당하는 것으로 환산했을 때, 그린란드 빙상은 1972년 이후 약 13.7mm를 기여했습니다.[21]

2012년에서 2017년 사이에는 연간 0.68mm를 기여했는데, 1992년에서 1997년 사이에는 연간 0.07mm를 기여했습니다.[53] 2012-2016년 기간 동안 그린랜드의 순 기여는 육지 빙원(열팽창 제외)에서 해수면 상승의 37%에 해당합니다.[55] 이러한 용융 속도는 지난 12,000년 동안 빙상이 경험한 가장 큰 것과 맞먹습니다.[16]

현재 그린란드 빙상은 온난화의 극심한 지역적 증폭을 받는 북극에 위치하고 있기 때문에 매년 남극 빙상보다 더 많은 질량을 잃고 있습니다.[45][56][57] 서남극 빙상의 얼음 손실은 트와이트와 파인 아일랜드 빙하의 취약성으로 인해 가속화되고 있으며, 해수면 상승에 대한 남극의 기여는 금세기 말 그린란드를 추월할 것으로 예상됩니다.[17][19]

관측된 빙하 후퇴

출구 빙하가 북극으로 얼음을 흘리면서 후퇴하는 것은 그린란드 빙상 감소의 큰 요인입니다. 빙하로 인한 손실은 1980년대 이후 관측된 얼음 손실의 49%에서 66.8% 사이를 설명한다고 추정됩니다.[21][53] 빙하가 높이를 잃기 시작하면서 얇아지는 현상이 감지되면서 1990년대까지 빙상 마진의 70%에 걸쳐 이미 얼음의 순 손실이 관찰되었습니다.[59] 1998년과 2006년 사이에 해안 빙하의 경우 1990년대 초에 비해 4배 더 빠르게 얇아져 연간 1m(3+1 ⁄ 2피트)에서 10m(33피트) 사이의 속도로 떨어지는 반면 내륙에 있는 빙하는 그러한 가속을 거의 겪지 않았습니다.

가장 극적으로 얇아진 예 중 하나는 남동쪽의 Kangerlusuaq 빙하였습니다. 길이는 20마일(32km)이 넘고 폭은 4.5마일(7km), 두께는 약 1km(1⁄2마일)로 그린란드에서 세 번째로 큰 빙하입니다. 1993년과 1998년 사이에 해안에서 5km(3m) 이내에 있는 빙하의 일부는 높이가 50m(164ft)나 감소했습니다.[63] 관측된 얼음 유속은 1988-1995년 연간 3.1-3.7 마일 (5-6 km)에서 2005년 연간 8.7 마일 (14 km)로, 당시 빙하 중 가장 빠른 유속이었습니다.[62] Kangerlusuaq의 후퇴는 2008년까지 느려졌고,[64] 2016-2018년까지 약간의 회복을 보였습니다.[65]

그린란드의 다른 주요 출구 빙하들도 최근 수십 년 동안 급격한 변화를 겪고 있습니다. 가장 큰 출구 빙하는 야콥샤븐 이스르 æ (그린란드어: 수십 년 동안 빙하학자들에 의해 관찰된 그린란드 서부의 세르메크 쿠잘레크).[66] 역사적으로 빙하의[67] 6.5%(캉거루수아크의[62] 4%와 비교)에서 하루 최대 20미터(66피트)의 속도로 얼음을 배출합니다.[68] 1850년에서 1964년 사이에 약 30 km (19 mi) 후퇴할 만큼 충분한 얼음을 잃었지만, 질량 증가는 이후 35년 동안 균형을 유지할 수 있을 정도로 충분히 증가했지만,[68] 1997년 이후에는 급격한 질량 감소로 전환되었습니다.[69][67] 2003년까지 연평균 얼음 유속은 1997년 이후 거의 두 배로 증가했는데, 이는 빙하 앞의 얼음 혀가 붕괴되고 [69]빙하가 2001년에서 2005년 사이에 94 평방 킬로미터(36 평방 마일)의 얼음을 흘렸기 때문입니다.[70] 얼음 흐름은 2012년 하루 45미터(148피트)에 달했지만,[71] 이후 상당히 느려졌고, 2016년과 2019년 사이에 질량 증가를 보였습니다.[72][73]

그린란드 북부의 피터만 빙하는 절대적인 면에서는 더 작지만, 최근 수십 년 동안 가장 급격한 붕괴를 경험했습니다. 2000년부터 2001년까지 85제곱킬로미터(33제곱미터)의 유빙을 잃었고, 2008년에는 28제곱킬로미터(11제곱미터)의 빙산이 부서졌고, 2010년 8월에는 260제곱킬로미터(100제곱미터)의 빙산이 빙붕에서 갈라졌습니다. 이것은 1962년 이래로 가장 큰 북극 빙하가 되었고, 선반 크기의 4분의 1에 달했습니다.[74] 2012년 7월, 피터만 빙하는 맨해튼 면적의 두 배인 120 제곱 킬로미터 (46 평방 마일)에 달하는 또 다른 주요 빙하를 잃었습니다.[75] 2023년 현재 빙하의 빙붕은 2010년 이전 상태의 약 40%가 사라졌으며, 더 이상의 얼음 손실에서 회복될 가능성은 낮은 것으로 간주됩니다.[76]

2010년대 초, 일부 추정치는 가장 큰 빙하를 추적하는 것이 얼음 손실의 대부분을 설명하기에 충분할 것이라고 제안했습니다.[77] 그러나 빙하의 역학은 빙하의 두 번째로 큰 빙하인 헬하임 빙하에서 볼 수 있듯이 예측하기 어려울 수 있습니다. 그것의 얼음 손실은 1993년과 2005년 사이에 빙하 지진의 현저한 증가와 관련하여 2005년에 급격한 후퇴로 정점을 찍었습니다.[78][79] 그 이후로 2005년 위치 근처에서 비교적 안정적인 상태를 유지하고 있으며, 야콥샤벤과 캉거루수아크에 비해 상대적으로 적은 질량을 잃었지만 가까운 미래에 또 다른 급격한 후퇴를 경험할 수 있을 만큼 충분히 침식되었을 수 있습니다.[80][81] 한편, 더 작은 빙하는 지속적으로 가속 속도로 질량을 잃고 있으며,[82] 이후 연구에서는 더 작은 빙하를 설명하지 않으면 전체 빙하 후퇴가 과소평가된다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[21] 2023년까지 그린란드 해안의 얼음 손실 속도는 2000년 이후 20년 동안 두 배로 증가했는데, 이는 대부분 작은 빙하로 인한 손실 가속화 때문입니다.[83][84]

빙하 후퇴를 가속화하는 프로세스

2000년대 초부터 빙하학자들은 그린란드의 빙하 후퇴가 너무 빨리 가속화되어 지표면 온도 상승에 따른 선형적인 용융 증가로 설명할 수 없으며 추가적인 메커니즘도 작동해야 한다고 결론지었습니다.[86][87][88] 가장 큰 빙하에서 발생하는 급격한 석회화 현상은 1986년에 "야콥스하븐 효과"로 처음 설명된 것과 일치합니다.[89] 얇아지면 빙하의 부력이 증가하여 후퇴를 방해할 마찰이 줄어들고, 속도가 증가하여 석회화 전선에서 힘의 불균형이 발생합니다.[90][91][67] 1997년 이후 야콥샤븐 이스브라에와 다른 빙하들의 전반적인 가속은 빙하 전선을 아래에서 녹이는 북대서양 해역의 온난화에 기인했습니다. 이 온난화가 1950년대부터 계속되는 동안,[92] 1997년에는 순환의 변화가 있었고, 이로 인해 이르밍거 해의 상대적으로 따뜻한 해류가 서그린란드의 빙하와 더 가까이 접촉하게 되었습니다.[93] 2016년까지 서그린란드 해안선의 많은 부분을 가로지르는 물은 1990년대에 비해 1.6°C(2.9°F) 따뜻해졌고, 일부 더 작은 빙하는 일반적인 분만 과정보다 더 많은 얼음을 잃어 빠른 후퇴로 이어졌습니다.[94]

반대로 Jakobshavn Isbrae는 깊은 빙하 해구를 통해 높은 노출을 경험하기 때문에 해양 온도 변화에 민감합니다.[95][96] 이러한 민감도는 2015년 이후 해수의 유입이 더 느려진 원인이 되었음을 의미하며,[73] 이는 대부분 해빙과 빙산이 바로 연안에서 더 오래 생존할 수 있었고, 따라서 빙하를 안정화시키는 데 도움이 되었기 때문입니다.[97] 마찬가지로, Helheim과 Kangerdlugssuaq의 빠른 후퇴와 그 후의 감속은 또한 인근 해류의 각각의 온난화와 냉각과 관련이 있습니다.[98] 피터만 빙하의 빠른 후퇴 속도는 조수에 따라 1킬로미터 정도 앞뒤로 이동하는 것으로 보이는 접지선의 지형과 연결되어 있습니다. 유사한 과정이 다른 빙하에서 발생할 수 있다면 궁극적인 대량 손실 속도가 두 배가 될 수 있다고 제안되었습니다.[99][85]

빙하 표면의 융해가 증가하면 출구 빙하의 측면 후퇴를 가속화할 수 있는 몇 가지 방법이 있습니다. 첫째, 지표면의 녹은 물의 증가는 더 많은 양의 얼음판을 통해 물랭을 통해 암반으로 흘러가게 합니다. 그곳에서 빙하의 바닥을 윤활하고 더 높은 기저 압력을 생성하여 마찰을 줄이고 얼음 절단 속도를 포함하여 빙하 운동을 가속화합니다. 이 메커니즘은 1998년과 1999년에 Sermeq Kujalleq에서 관찰되었으며, 2~3개월 동안 유량이 최대 20% 증가했습니다.[100][101] 그러나 일부 연구에 따르면 이 메커니즘은 가장 큰 출구 빙하가 아닌 특정 작은 빙하에만 적용되며 [102]얼음 손실 추세에 약간의 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[103]

둘째로, 일단 녹은 물이 바다로 흘러들어간다면, 그것은 해양 온난화가 전혀 없는 경우에도 해수와 상호작용하고 지역 순환을 변화시킴으로써 빙하에 여전히 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[104] 특정 피오르드에서는 얼음 아래에서 흘러나오는 큰 용탕이 바닷물과 섞여서 분만 전선에 손상을 줄 수 있는 난류 플룸을 만들 수 있습니다.[105] 모델들은 일반적으로 녹은 물의 유출로 인한 영향을 해양 온난화의 이차적인 것으로 간주하지만,[106] 13개 빙하를 관측한 결과, 녹은 물 기둥이 얕은 접지선을 가진 빙하에 더 큰 역할을 하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[107] 게다가, 2022년 연구는 깃털로 인한 온난화가 그린란드 북서쪽의 수중 용융에 더 큰 영향을 미쳤다는 것을 시사합니다.[104]

마지막으로, 녹은 물은 폭이 2cm(1인치)에 불과한 대부분의 연구 도구가 집어 들기에는 너무 작은 균열을 통해서 흐를 수도 있다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다. 이러한 균열은 빙상 전체를 통해 기반암으로 연결되지는 않지만 여전히 지표면에서 수백 미터 아래까지 내려갈 수 있습니다.[108] 얼음판을 약화시키고, 얼음을 통해 직접 더 많은 열을 전달하고, 얼음이 더 빨리 흐르도록 하기 때문에 얼음판의 존재는 중요합니다.[109] 이 최근 연구는 현재 모델에 포착되지 않았습니다. 이러한 발견을 뒷받침하는 과학자 중 한 명인 Alun Hubbard는 "현재의 과학적 이해가 그들의 존재를 수용할 수 없는" 물소를 발견하는 것이 보통 그들의 형성에 필요한 것으로 생각되는 기존의 큰 크레바스가 없는 상태에서 그들이 헤어라인 균열로부터 어떻게 발달할 수 있는지를 무시하기 때문이라고 설명했습니다.[110]

표면이 녹는 것을 관찰했습니다.

현재 그린란드 빙상 표면의 총 얼음 축적량은 출구 빙하 개별 손실 또는 여름 동안의 표면 용융보다 크며, 이 둘의 결합으로 연간 순 손실이 발생합니다.[4] 예를 들어, 1994년과 2005년 사이에 빙하의 내부는 매년 평균 6cm (2.4인치)씩 두꺼워졌는데, 이는 부분적으로 [북대서양 진동]의 증가 단계 때문입니다.[111] 매년 여름, 이른바 눈의 선이 빙상의 표면을 그 위의 영역으로 분리하고, 그 위에도 눈이 계속 쌓이고, 그 아래의 영역은 여름의 융해가 일어나는 영역입니다.[112] 눈 라인의 정확한 위치는 매년 여름에 움직이고, 만약 눈 라인이 전년도에 덮었던 일부 지역에서 멀어진다면, 더 어두운 얼음이 노출되면서 눈 라인이 훨씬 더 많이 녹는 경향이 있습니다. 설선에 대한 불확실성은 각각의 녹는 계절을 미리 예측하기 어렵게 만드는 요인 중 하나입니다.[113]

스노우 라인 위의 얼음 축적률의 주목할 만한 예는 제2차 세계 대전 초기에 추락하여 1992년에 회수된 록히드 P-38 라이트닝 전투기인 글레이셔 걸(Glacier Girl)에 의해 제공되며, 그 때까지 268피트(81+1 ⁄2m)의 얼음 아래에 묻혀 있었습니다. 또 다른 예는 2017년 에어버스 A380이 그린란드 상공에서 제트 엔진 중 하나가 폭발한 후 캐나다에 비상 착륙해야 했을 때 발생했습니다. 엔진의 거대한 공기 흡입 팬은 2년 후 빙상에서 회수되었는데, 그때 이미 얼음과 눈의 4피트(1m) 아래에 묻혀 있었습니다.[115]

여름 표면 용융이 증가하고 있지만, 용융이 지속적으로 자체적으로 눈 축적을 초과하기까지는 수십 년이 걸릴 것으로 예상됩니다.[4] 또한 기후 변화가 물 순환에 미치는 영향과 관련된 지구 강수량의 증가는 그린란드 상공의 강설량을 증가시킬 수 있으며, 따라서 이러한 전환을 더욱 지연시킬 수 있다는 가설도 제시되고 있습니다.[116] 이 가설은 2000년대에 빙상 위의 장기 강수 기록의 상태가 좋지 않았기 때문에 테스트하기 어려웠습니다.[117] 2019년까지 그린란드 남서부 지역의 적설량은 증가했지만 [118]그린란드 서부 지역 전체의 강수량은 크게 감소한 것으로 나타났습니다.[116] 게다가, 1980년 이후 비가 4배나 증가하면서 북서쪽의 강수량은 눈 대신 비로 더 많이 내렸습니다.[119] 비는 눈보다 따뜻하며, 얼음판 위에 얼면 더 어둡고 덜 단열된 얼음층을 형성합니다. 특히 늦여름 사이클론으로 인해 넘어질 때 손상을 입는데, 이전 모델에서는 점점 더 발생하는 것을 간과했습니다.[120] 수증기도 증가했는데, 이는 역설적으로 건조한 공기가 아닌 습한 공기를 통해 열이 아래로 쉽게 방출되도록 함으로써 용융을 증가시킵니다.[121]

종합해보면, 여름의 온기가 눈과 얼음을 슬러시로 만들고 연못을 녹이는 스노우 라인 아래의 멜트 존은 1979년 상세 측정이 시작된 이후 가속적인 속도로 확대되고 있습니다. 2002년까지 면적은 1979년 이후 16% 증가한 것으로 밝혀졌으며 매년 녹는 계절은 이전 기록을 모두 경신했습니다.[45] 또 다른 기록은 2012년 7월에 작성되었는데, 이때 용융대가 빙상 표면의 97%까지 확장되었고,[122] 그 해 용융기 동안 빙상은 전체 질량(2900Gt)의 약 0.1%를 잃었으며, 순손실(464Gt)은 또 다른 기록을 세웠습니다.[123] 이는 빙하가 녹는 것이 특정 지역이 아닌 거의 전체 빙상 표면에서 일어나는 "대규모 융해 사건"의 첫 번째 직접 관측 사례가 되었습니다.[124] 그 사건은 알베도로 인해 일반적으로 더 낮은 온도를 초래하는 구름 덮개가 실제로 밤에 첫 번째 층의 용융물 재동결을 방해하여 총 용융물 유출을 30%[125][126] 이상 증가시킬 수 있다는 반직관적인 발견으로 이어졌습니다. 얇고 물이 풍부한 구름은 가장 나쁜 영향을 미치며 2012년 7월에 가장 두드러졌습니다.[127]

얼음 코어는 2012년과 같은 규모의 용융 사건이 마지막으로 발생한 것이 1889년이라는 것을 보여주었고, 일부 빙하학자들은 2012년이 150년 주기의 일부라는 희망을 나타냈습니다.[128][129] 이는 2019년 여름 고온과 부적절한 구름 덮개의 결합으로 인해 더 큰 질량 용융 사건이 발생하여 궁극적으로 최대 300,000 마일(482,803.2 km) 이상을 덮었던 것으로 입증되었습니다. 예상대로 2019년에는 586Gt 순 질량 감소라는 새로운 기록을 세웠습니다.[54][130] 2021년 7월에는 또다시 기록적인 대량 용융 사건이 발생했습니다. 최고점에서는 340,000 마일(547,177.0 km)에 달했고, 며칠 동안 하루 88 Gt의 얼음 손실이 발생했습니다.[131][132] 2021년 8월에도 고온이 계속되어 용융 범위는 337,000 mi(542,348.9 km)에 머물렀습니다. 당시 해발 10,551피트(3,215.9m)에 위치한 그린란드 정상역에는 13시간 동안 비가 내렸습니다.[133] 1989년 이래로 정상의 기온이 겨우 세 번이나 영하로 올랐고, 이전에는 그곳에 비가 내린 적이 없었기 때문에, 연구원들은 강우량을 측정할 강수량 측정기가 없었습니다.[134]

그린란드 중앙 빙상의 엄청난 두께 때문에, 가장 광범위한 녹는 사건도 동파 시즌이 시작되기 전에 극히 일부에만 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로 과학 문헌에서 "단기 변동성"으로 간주됩니다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 그들의 존재는 중요합니다: 현재 모델들이 그러한 사건의 범위와 빈도를 과소평가한다는 사실은 IPCC 제 5차 평가 보고서의 해수면 상승 예측의 중간 시나리오가 아닌 그린란드와 남극에서 관측된 빙상 감소가 최악의 경우를 추적하는 주요 원인 중 하나로 간주됩니다.[135][136][137] 그린란드의 가장 최근의 과학적인 예측들 중 일부는 연구된 기간(즉, 지금부터 2100년 사이 또는 지금부터 2300년 사이)에 걸쳐 매년 대규모의 융해 사건이 발생하는 극단적인 시나리오를 포함하며, 그러한 가상의 미래가 얼음 손실을 크게 증가시킬 것임을 설명합니다. 그래도 연구 기간 내에 빙상 전체가 녹지는 않을 겁니다.[138][139]

알베도 변동

빙상에서 연간 기온은 그린란드의 다른 지역보다 상당히 낮습니다. 남돔(위도 63°~65°N)에서 약 -20°C(-4°F), 북돔(위도 72°N(그린란드에서 네 번째로 높은 정상)에서 가까운 -31°C(-24°F)입니다.[1] 1991년 12월 22일 그린란드 빙상의 지형 정상 부근의 자동 기상 관측소에서 -69.6 °C (-93.3 °F) 의 기온이 기록되어 북반구에서 기록된 가장 낮은 기온이 되었습니다. 이 기록은 28년 이상 눈에 띄지 않다가 2020년에 마침내 인정받았습니다.[140] 이러한 낮은 온도는 부분적으로 빙상의 밝은 흰색 표면이 햇빛을 반사하는 데 매우 효과적이기 때문에 빙상의 높은 알베도 때문에 발생합니다. 얼음 알베도 피드백은 온도가 증가함에 따라 더 많은 얼음이 녹고 맨땅이 드러나거나 심지어 더 어두운 연못을 형성하는 것을 의미하며, 이 둘은 모두 알베도를 감소시키는 역할을 하며, 이는 온난화를 가속화하고 추가적인 용융에 기여합니다. 이는 기후 모델에 의해 고려되며, 기후 모델은 빙상이 완전히 손실되면 지구 온도가 0.13 °C (0.23 °F) 증가하는 반면 그린란드의 지역 온도는 0.5 °C (0.90 °F)에서 3 °C (5.4 °F) 증가할 것으로 추정합니다.[141][24][25]

불완전한 용융조차도 이미 얼음 알베도 피드백에 어느 정도 영향을 미칩니다. 더 어두운 용융 연못의 형성 외에도, 더 따뜻한 온도는 빙하의 표면에 조류의 성장을 증가시킬 수 있게 합니다. 해조류의 매트는 얼음 표면보다 색깔이 어둡기 때문에 열복사를 더 많이 흡수하고 얼음이 녹는 속도를 높입니다.[142] 2018년에는 먼지, 그을음, 살아있는 미생물과 조류로 뒤덮인 지역이 2000년에서 2012년 사이에 12% 성장한 것으로 나타났습니다.[143] 2020년에 매연과 먼지와 달리 빙상 모델에 의해 설명되지 않는 조류의 존재는 이미 매년 10~13%[144]씩 증가하고 있음이 입증되었습니다. 또한 빙상이 녹는 것으로 인해 서서히 낮아지면서 표면 온도가 상승하기 시작하고 눈이 쌓이기 어려워지고 얼음으로 변하게 되는데, 이를 지표면 상승 피드백이라고 합니다.[145][146]

그린란드 용탕의 지구물리 및 생화학적 역할

1993년에도 그린란드의 녹은 결과 연간 300입방킬로미터의 담수가 바다로 유입되었는데, 이는 남극 빙상에서 유입되는 액체 용융물보다 상당히 큰 양이었고, 전 세계 모든 강에서 바다로 유입되는 담수의 0.7%에 해당하는 양이었습니다.[148] 이 녹은 물은 순수하지 않고 다양한 원소를 함유하고 있는데, 특히 철을 포함하고 있는데, 그 중 약 절반(매년 약 30만 톤)이 식물성 플랑크톤의 영양소로 생물학적으로 이용 가능합니다.[149] 따라서 그린란드의 녹은 물은 지역 피오르드에서 해양 1차 생산을 향상시키고,[150] 전체 1차 생산의 40%가 녹은 물의 영양소에 기인한 래브라도 해에서 더 멀리 떨어져 있습니다.[151] 1950년대 이후 기후 변화로 인한 그린란드 융해의 가속화는 이미 북아이슬란드 선반 해역에서 생산성을 증가시키고 있으며,[152] 그린란드 피오르드의 생산성도 19세기 후반부터 현재에 이르는 역사적 기록의 어느 시점보다 높습니다.[153] 일부 연구에 따르면 그린란드의 녹은 물은 주로 탄소와 철을 첨가하는 것이 아니라 질산염이 풍부한 저수층을 교반하여 표면의 식물성 플랑크톤에 더 많은 영양분을 공급함으로써 해양 생산성에 도움이 된다고 합니다. 출구 빙하가 내륙으로 후퇴함에 따라 용융수는 하층에 영향을 미칠 수 없게 되며, 이는 용융수의 양이 증가하더라도 용융수의 이점이 감소할 것임을 의미합니다.[147]

그린란드에서 오는 녹은 물의 영향은 영양소 수송을 넘어서고 있습니다. 예를 들어, 녹은 물에는 용해된 유기 탄소도 포함되어 있는데, 이는 빙상 표면의 미생물 활동에서 비롯되며, 얼음 아래의 고대 토양과 식물의 잔재에서 발생합니다.[155] 전체 빙상 아래에는 약 0.5-27억 톤의 순수한 탄소가 있고, 그 안에는 훨씬 적습니다.[156] 이는 북극 영구 동토층 내에 포함된 1400-16500억 톤 [157]또는 연간 약 400억 톤의 CO를2 인위적으로 배출하는 것보다 훨씬 적습니다.)[19]: 1237 그러나 녹은 물을 통한 이 탄소의 방출은 전체 이산화탄소 배출량을 증가시킬 경우 여전히 기후 변화 피드백으로 작용할 수 있습니다.[158] 러셀 빙하에는 녹은 물 탄소가 이산화탄소보다 훨씬 큰 지구 온난화 잠재력을 가진 메탄으로 대기에 방출되는 것으로 알려진 지역이 하나 있습니다.[154] 그러나 그것은 또한 많은 수의 메탄영양 박테리아를 보유하고 있어서 그러한 배출을 제한합니다.[159][160]

2021년 연구에 따르면 남서부 빙상 아래에 수은(독성이 강한 중금속)의 광물 퇴적물이 있어야 한다고 주장했는데, 이는 녹은 물이 지역 피오르드로 유입되기 때문입니다. 이 농도가 확인된다면 전 세계 모든 강에서 수은의 10%에 해당하는 농도가 될 것입니다.[161][162] 2024년 후속 연구에서는 21개 지역의 용융물에서 "매우 낮은" 농도만 발견했습니다. 2021년 결과는 수은에 의한 우발적인 샘플 오염에 의해 가장 잘 설명되었다고 결론지었습니다.II) 염화물(chloride), 제1 연구팀이 시약으로 사용하는 것.[163] 하지만, 이전에 미국 군사 기지였던 캠프 센추리에서 독성 폐기물이 방출될 위험이 여전히 남아 있습니다. 이 곳은 얼음 벌레 프로젝트를 위해 핵무기를 운반하기 위해 건설된 곳이었습니다. 이 프로젝트는 취소되었지만 현장은 결코 정화되지 않았으며, 이제 용융이 진행됨에 따라 핵 폐기물, 2만 리터의 화학 폐기물 및 2,400만 리터의 처리되지 않은 하수로 용융물을 오염시킬 위협이 있습니다.[164][165]

마지막으로, 담수의 양이 증가하면 해양 순환에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[45] 일부 과학자들은 그린란드로부터의 이러한 증가된 배출을 대서양 자오선 전복 순환, 즉 AMOC와 연결된 소위 북대서양의 차가운 방울과 연결시켜 그 명백한 둔화를 연관시켰습니다.[167][168][169][170] 2016년, 한 연구는 그린란드 추세에 대한 더 나은 시뮬레이션을 8개의 최첨단 기후 모델의 예측에 통합함으로써 미래 AMOC 변화에 대한 예측을 개선하려고 시도했습니다. 그 연구는 2090년부터 2100년까지 AMOC가 현재 궤도와 가장 유사한 대표 농도 경로 4.5에서 약 18% 약화(잠재력이 3%에서 34% 사이 약화)되는 반면,[171][172] 대표 농도 경로 8.5에서는 37% 약화(15%에서 65% 사이 약화)되는 것을 발견했습니다. 지속적으로 증가하는 배출량을 가정합니다. 두 시나리오가 2100년 이후로 연장될 경우 AMOC는 궁극적으로 RCP 4.5 하에서 안정화되지만 RCP 8.5 하에서 지속적으로 감소합니다. 2290~2300년 평균 감소율은 74%이고 해당 시나리오에서 완전히 붕괴될 가능성은 44%이며 광범위한 부작용이 발생합니다.[173]

향후 빙결손실

단기

2021년 IPCC 제6차 평가 보고서는 가장 높은 지구 온난화와 관련된 시나리오인 SSP5-8.5 하에서 그린란드 빙상 용융이 지구 해수면에 약 13cm(5인치)를 추가할 것이라고 추정했습니다(3+1 ⁄ 2-7인치). 그리고 5-23cm(2-9인치)의 매우 가능성 있는 범위(5-95% 신뢰 수준). "중간" SSP2-4.5 시나리오는 각각 4~13cm(1+1 ⁄ 2~5인치) 및 1~18cm(1 ⁄ 2~7인치)의 가능성과 매우 가능성이 높은 8cm(3인치)를 추가합니다. 파리 협정의 목표가 상당 부분 달성된다고 가정하는 낙관적인 시나리오인 SSP1-2.6은 약 6cm(2+1 ⁄2인치)와 15cm(6인치) 이하를 추가하며, 빙상이 질량을 증가시켜 해수면을 약 2cm(1인치) 감소시킬 가능성이 작습니다.

제임스 한센(James Hansen)이 이끄는 일부 과학자들은 빙상이 빙상 모델에 의해 추정되는 것보다 훨씬 더 빨리 분해될 수 있다고 주장했지만,[176] 심지어 그들의 예상도 그린란드의 많은 부분이 21세기에 살아남습니다.[2] Hansen의 2016년 논문은 그린란드의 얼음 손실이 2060년까지 약 33 cm (13 in)를 추가할 수 있으며, 이 수치는 남극 빙하의 두 배에 달하며,[177] CO2 농도가 백만분의 600 parts를 초과할 경우 과학계에서 즉시 논란이 되었습니다.[178] 반면에 다른 과학자들의 2019년 연구는 최악의 기후 변화 시나리오에서 2100년까지 최대 33cm (13인치)를 주장했습니다.[20]

현재의 손실과 마찬가지로 빙상의 모든 부분이 동일하게 기여하는 것은 아닙니다. 예를 들어, 북동 그린란드 얼음 스트림은 RCP 4.5와 RCP 8.5 아래에서 각각 1.3-1.5cm에서 2100년까지 기여할 것으로 추정됩니다.[179] 반면에, 가장 큰 세 빙하인 야콥샤븐, 헬하임, 그리고 캉거루수아크는 모두 빙상의 남쪽 절반에 위치하고 있고, 그들 중 세 개만이 RCP 8.5 아래에 9.1-14.9 mm를 추가할 것으로 예상됩니다.[28] 마찬가지로, 2013년 추산에 따르면 2200년까지 그들과 또 다른 대형 빙하는 RCP 8.5 아래에서 2200년까지 29~49 밀리미터, RCP 4.5 아래에서 19~30 밀리미터를 추가할 것으로 예상됩니다.[180] 이를 종합하면, 그린란드의 21세기 얼음 손실에 대한 단일한 가장 큰 기여는 북서쪽과 중앙 서쪽 하천(Jakobshavn을 포함한 후자)에서 발생할 것으로 예상되며, 빙하 후퇴는 전체 얼음 손실의 적어도 절반을 책임질 것입니다. 표면 용융이 금세기 말에 지배적이 될 것이라는 이전의 연구들과는 대조적으로.[58] 하지만 만약 그린란드가 해안 빙하를 모두 잃게 된다면, 그린란드가 계속해서 줄어들 것인지의 여부는 전적으로 여름에 녹는 표면이 겨울 동안의 얼음 축적보다 지속적으로 더 큰지 여부에 의해 결정될 것입니다. 최고 배출량 시나리오에서는 해안 빙하가 사라지기 훨씬 전인 2055년경에 발생할 수 있습니다.[4]

그린란드로부터의 해수면 상승이 모든 해안에 똑같이 영향을 미치는 것은 아닙니다. 빙상의 남쪽은 다른 부분보다 훨씬 더 취약하고, 관련된 얼음의 양은 지각의 변형과 지구의 자전에 영향이 있다는 것을 의미합니다. 이 효과는 미묘하지만, 이미 미국 동부 해안은 전 세계 평균보다 빠른 해수면 상승을 경험하게 합니다.[181] 동시에 그린란드 자체도 빙상이 줄어들고 지반 압력이 가벼워지면서 등압 반등을 경험할 것입니다. 마찬가지로, 얼음 덩어리가 줄어들면 다른 육지 덩어리에 비해 해안가에 더 낮은 중력을 발휘합니다. 이 두 과정은 그린란드가 다른 곳에서 상승하더라도 그린란드 연안의 해수면을 떨어뜨릴 것입니다.[182] 이 현상의 반대는 소빙하기 동안 빙하가 질량이 증가했을 때 발생했습니다: 증가된 무게는 더 많은 물을 끌어들이고 특정 바이킹 정착지를 물에 잠기게 했고, 곧 바이킹 포기에 큰 역할을 했을 것입니다.[183][184]

장기

특히, 빙하의 거대한 크기는 단기적으로 기온 변화에 둔감하게 만들 뿐만 아니라, 고생대의 증거에서 알 수 있듯이, 그 아래로 거대한 변화를 초래합니다.[11][35][34] 극지 증폭은 그린란드를 포함한 북극을 지구 평균보다 3~4배 더 따뜻하게 만듭니다.[186][187][188] 따라서 130,000~115,000년 전의 에미안 간빙기와 같은 시기는 지구적으로 오늘날보다 그다지 따뜻하지 않았지만, 빙상은 8°C(14°F) 더 따뜻했고, 북서쪽은 현재보다 130 ± 300m 더 낮았습니다.[189][190] 일부 추정치에 따르면 가장 취약하고 가장 빠르게 하강하는 빙상 부분은 1997년경에 이미 "돌아오지 않는 지점"을 지나 온도 상승이 멈추더라도 소멸될 것입니다.[191][185][192]

2022년 논문에 따르면 2000-2019년 기후는 미래에 이미 전체 빙상의 ~3.3% 부피를 손실하고 미래의 온도 변화와 무관하게 궁극적으로 27cm(10+1 ⁄ 2인치)의 SLR을 약속합니다. 그들은 또한 2012년 빙하에서 목격된 그 당시 기록적인 용융이 새로운 정상이 된다면, 그 빙하는 약 78cm (30+1 ⁄2인치) SLR에 이를 것이라고 추정했습니다. 또 다른 논문은 400,000년 전의 고기후 증거가 최소한 1에 해당하는 그린란드의 얼음 손실과 일치한다고 제안했습니다.1.5 °C (2.7 °F)에 가까운 기후에서 해수면이 4 m (4+1 ⁄ 2 ft) 상승하며, 이는 적어도 가까운 미래에 피할 수 없는 현상입니다.

또한 지구 온난화의 특정 수준에서 그린란드의 빙하 전체가 결국에는 녹을 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 처음에는 ~2,850,000 km3(684,000 cumi)에 달하는 것으로 추정되어 전 세계 해수면이 7.2 m(24 ft) 증가할 것으로 [52]예상되었으나 나중에 추정된 바에 따르면 ~2,900,000 km3(696,000 cumi)로 크기가 증가하여 ~7.4 m(24 ft)의 해수면 상승이 이루어졌습니다.[2]

총 빙상 손실 임계값

2006년에 이 빙상은 3.1 °C (5.6 °F)에서 사라질 가능성이 가장 높으며, 1.9 °C (3.4 °F)에서 5.1 °C (9.2 °F) 사이의 범위가 있을 것으로 추정되었습니다.[193] 그러나 이러한 추정치는 2012년에 급격히 감소하여 임계 값이 0.8°C(1.4°F)에서 3.2°C(5.8°F) 사이에 있을 수 있으며, 1.6°C(2.9°F)가 빙상이 사라진 가장 그럴듯한 지구 온도입니다.[194] 낮아진 온도 범위는 후속 문헌에서 널리 사용되었으며,[34][195] 2015년 저명한 NASA 빙하학자 에릭 리그노(Eric Rignot)는 2°C(3.6°F) 또는 3°C(5.4°F)의 지구 온난화 후 "그린란드의 얼음이 사라졌다"고 동의할 것이라고 주장했습니다.[145]

2022년 기후 시스템의 티핑 포인트에 대한 과학 문헌의 주요 검토는 임계값이 1.5°C(2.7°F)일 가능성이 가장 높으며, 상한 수준은 3°C(5.4°F), 최악의 경우 임계값은 0.8°C(1.4°F)로 변경되지 않았다고 제안했습니다.[24][25] 동시에, 빙하 붕괴의 가장 빠른 시기는 1000년이며, 이는 2500년까지 지구 온도가 10°C(18°F)를 초과하는 최악의 경우를 가정한 연구에 기초한 것이며,[20] 그렇지 않을 경우 얼음 손실은 약 10년에 걸쳐 발생한다고 언급했습니다.임계값을 초과한 후 1000년이 경과합니다. 가능한 최장 추정치는 15,000년입니다.[24][25]

2023년에 발표된 모델 기반 예측에 따르면 그린란드 빙상은 이전 추정치에서 제안한 것보다 약간 더 안정적일 수 있습니다. 한 논문은 빙상 붕괴의 임계 값이 1.7°C (3.1°F)에서 2.3°C (4.1°F) 사이에 있을 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 발견했습니다. 또한, 이 얼음판은 처음으로 기준치가 뚫린 후 몇 세기까지 온난화가 1.5°C(2.7°F) 이하로 줄어들면 여전히 얼음판을 구할 수 있으며, 지속적인 붕괴를 피할 수 있음을 나타냅니다. 하지만 그렇게 하면 전체 빙상이 유실되는 것을 막을 수 있지만, 애초에 온난화 문턱을 넘지 않았던 경우와 달리 전체 해수면 상승은 최대 수 미터까지 높아질 것입니다.[6]

보다 복잡한 빙상 모델을 사용한 또 다른 논문에서는 온난화가 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) 도를 넘었기 때문에 ~26 cm (10 in)의 해수면 상승이 불가피해졌으며,[5] 이는 2022년 직접 관측에서 도출된 추정치와 거의 일치한다는 것을 발견했습니다.[138] 그러나 1.6 °C (2.9 °F)는 빙하가 장기간 해수면 상승의 2.4 m (8 ft)에 불과할 가능성이 있는 반면, 온도가 지속적으로 2 °C (3.6 °F)를 초과할 경우 6.9 m (23 ft) 상당의 해수면 상승이 거의 완전하게 녹을 가능성이 있음을 발견했습니다. 이 논문은 또한 남그린란드 얼음 전체가 녹을 때까지 온도를 0.6°C(1.1°F) 이하로 낮추면 그린란드의 얼음 손실이 역전될 수 있으며, 이는 CO2 농도가 300ppm으로 감소하지 않으면 해수면이 1.8m(6ft) 상승하고 어떤 재성장도 막을 수 있다고 제안했습니다. 만약 빙상 전체가 녹는다면, 기온이 산업화 이전 수준 이하로 떨어질 때까지 빙상은 다시 자라기 시작하지 않을 것입니다.[5]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d e Greenland Ice Sheet. 24 October 2023. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "How Greenland would look without its ice sheet". BBC News. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Tan, Ning; Ladant, Jean-Baptiste; Ramstein, Gilles; Dumas, Christophe; Bachem, Paul; Jansen, Eystein (12 November 2018). "Dynamic Greenland ice sheet driven by pCO2 variations across the Pliocene Pleistocene transition". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4755. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07206-w. PMC 6232173. PMID 30420596.

- ^ a b c d e Noël, B.; van Kampenhout, L.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; van de Berg, W. J.; van den Broeke, M. R. (19 January 2021). "A 21st Century Warming Threshold for Sustained Greenland Ice Sheet Mass Loss". Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (5): e2020GL090471. Bibcode:2021GeoRL..4890471N. doi:10.1029/2020GL090471. hdl:2268/301943. S2CID 233632072.

- ^ a b c d Höning, Dennis; Willeit, Matteo; Calov, Reinhard; Klemann, Volker; Bagge, Meike; Ganopolski, Andrey (27 March 2023). "Multistability and Transient Response of the Greenland Ice Sheet to Anthropogenic CO2 Emissions". Geophysical Research Letters. 50 (6): e2022GL101827. doi:10.1029/2022GL101827. S2CID 257774870.

- ^ a b c d Bochow, Nils; Poltronieri, Anna; Robinson, Alexander; Montoya, Marisa; Rypdal, Martin; Boers, Niklas (18 October 2023). "Overshooting the critical threshold for the Greenland ice sheet". Nature. 622 (7983): 528–536. Bibcode:2023Natur.622..528B. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06503-9. PMC 10584691. PMID 37853149.

- ^ a b c Thiede, Jörn; Jessen, Catherine; Knutz, Paul; Kuijpers, Antoon; Mikkelsen, Naja; Nørgaard-Pedersen, Niels; Spielhagen, Robert F (2011). "Millions of Years of Greenland Ice Sheet History Recorded in Ocean Sediments". Polarforschung. 80 (3): 141–159. hdl:10013/epic.38391.

- ^ a b Contoux, C.; Dumas, C.; Ramstein, G.; Jost, A.; Dolan, A.M. (15 August 2015). "Modelling Greenland ice sheet inception and sustainability during the Late Pliocene" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 424: 295–305. Bibcode:2015E&PSL.424..295C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2015.05.018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Knutz, Paul C.; Newton, Andrew M. W.; Hopper, John R.; Huuse, Mads; Gregersen, Ulrik; Sheldon, Emma; Dybkjær, Karen (15 April 2019). "Eleven phases of Greenland Ice Sheet shelf-edge advance over the past 2.7 million years" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 12 (5): 361–368. Bibcode:2019NatGe..12..361K. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0340-8. S2CID 146504179. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Robinson, Ben (15 April 2019). "Scientists chart history of Greenland Ice Sheet for first time". The University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Reyes, Alberto V.; Carlson, Anders E.; Beard, Brian L.; Hatfield, Robert G.; Stoner, Joseph S.; Winsor, Kelsey; Welke, Bethany; Ullman, David J. (25 June 2014). "South Greenland ice-sheet collapse during Marine Isotope Stage 11". Nature. 510 (7506): 525–528. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..525R. doi:10.1038/nature13456. PMID 24965655. S2CID 4468457.

- ^ a b Christ, Andrew J.; Bierman, Paul R.; Schaefer, Joerg M.; Dahl-Jensen, Dorthe; Steffensen, Jørgen P.; Corbett, Lee B.; Peteet, Dorothy M.; Thomas, Elizabeth K.; Steig, Eric J.; Rittenour, Tammy M.; Tison, Jean-Louis; Blard, Pierre-Henri; Perdrial, Nicolas; Dethier, David P.; Lini, Andrea; Hidy, Alan J.; Caffee, Marc W.; Southon, John (30 March 2021). "A multimillion-year-old record of Greenland vegetation and glacial history preserved in sediment beneath 1.4 km of ice at Camp Century". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (13): e2021442118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11821442C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2021442118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8020747. PMID 33723012.

- ^ a b c d e Gautier, Agnieszka (29 March 2023). "How and when did the Greenland Ice Sheet form?". National Snow and Ice Data Center. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ a b Yau, Audrey M.; Bender, Michael L.; Blunier, Thomas; Jouzel, Jean (15 July 2016). "Setting a chronology for the basal ice at Dye-3 and GRIP: Implications for the long-term stability of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 451: 1–9. Bibcode:2016E&PSL.451....1Y. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.053.

- ^ a b Hörhold, M.; Münch, T.; Weißbach, S.; Kipfstuhl, S.; Freitag, J.; Sasgen, I.; Lohmann, G.; Vinther, B.; Laepple, T. (18 January 2023). "Modern temperatures in central–north Greenland warmest in past millennium". Nature. 613 (7506): 525–528. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..525R. doi:10.1038/nature13456. PMID 24965655. S2CID 4468457.

- ^ a b Briner, Jason P.; Cuzzone, Joshua K.; Badgeley, Jessica A.; Young, Nicolás E.; Steig, Eric J.; Morlighem, Mathieu; Schlegel, Nicole-Jeanne; Hakim, Gregory J.; Schaefer, Joerg M.; Johnson, Jesse V.; Lesnek, Alia J.; Thomas, Elizabeth K.; Allan, Estelle; Bennike, Ole; Cluett, Allison A.; Csatho, Beata; de Vernal, Anne; Downs, Jacob; Larour, Eric; Nowicki, Sophie (30 September 2020). "Rate of mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet will exceed Holocene values this century". Nature. 586 (7827): 70–74. Bibcode:2020Natur.586...70B. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2742-6. PMID 32999481. S2CID 222147426.

- ^ a b "Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Executive Summary". IPCC. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ a b Stendel, Martin; Mottram, Ruth (22 September 2022). "Guest post: How the Greenland ice sheet fared in 2022". Carbon Brief. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Fox-Kemper, B.; Hewitt, H.T.; Xiao, C.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, G.; Drijfhout, S.S.; Edwards, T.L.; Golledge, N.R.; Hemer, M.; Kopp, R.E.; Krinner, G.; Mix, A. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (eds.). "Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change" (PDF). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, US. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Aschwanden, Andy; Fahnestock, Mark A.; Truffer, Martin; Brinkerhoff, Douglas J.; Hock, Regine; Khroulev, Constantine; Mottram, Ruth; Khan, S. Abbas (19 June 2019). "Contribution of the Greenland Ice Sheet to sea level over the next millennium". Science Advances. 5 (6): 218–222. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.9396A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav9396. PMC 6584365. PMID 31223652.

- ^ a b c d e f Mouginot, Jérémie; Rignot, Eric; Bjørk, Anders A.; van den Broeke, Michiel; Millan, Romain; Morlighem, Mathieu; Noël, Brice; Scheuchl, Bernd; Wood, Michael (20 March 2019). "Forty-six years of Greenland Ice Sheet mass balance from 1972 to 2018". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (19): 9239–9244. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.9239M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1904242116. PMC 6511040. PMID 31010924.

- ^ IPCC, 2021: Wayback Machine에서 2021년 8월 11일 보관된 정책 입안자를 위한 요약. 수신인: 2021년 기후변화: 물리 과학의 기초. Wayback Machine에서 2023년 5월 26일 보관된 기후 변화에 관한 정부 간 패널의 제6차 평가 보고서에 대한 작업 그룹 I의 기여 [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Pean, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. 첸, L. 골드파브, M.I. 고미스, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, B. Zhou(eds)]. 캠브리지 대학 출판부, 영국 캠브리지와 뉴욕, 뉴욕, 미국, pp. 3–32, doi:10.1017/97810091596.001

- ^ a b Christ, Andrew J.; Rittenour, Tammy M.; Bierman, Paul R.; Keisling, Benjamin A.; Knutz, Paul C.; Thomsen, Tonny B.; Keulen, Nynke; Fosdick, Julie C.; Hemming, Sidney R.; Tison, Jean-Louis; Blard, Pierre-Henri; Steffensen, Jørgen P.; Caffee, Marc W.; Corbett, Lee B.; Dahl-Jensen, Dorthe; Dethier, David P.; Hidy, Alan J.; Perdrial, Nicolas; Peteet, Dorothy M.; Steig, Eric J.; Thomas, Elizabeth K. (20 July 2023). "Deglaciation of northwestern Greenland during Marine Isotope Stage 11". Science. 381 (6655): 330–335. Bibcode:2023Sci...381..330C. doi:10.1126/science.ade4248. PMID 37471537. S2CID 259985096.

- ^ a b c d Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science. 377 (6611): eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl:10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Strunk, Astrid; Knudsen, Mads Faurschou; Egholm, David L. E; Jansen, John D.; Levy, Laura B.; Jacobsen, Bo H.; Larsen, Nicolaj K. (18 January 2017). "One million years of glaciation and denudation history in west Greenland". Nature Communications. 8: 14199. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814199S. doi:10.1038/ncomms14199. PMC 5253681. PMID 28098141.

- ^ Aschwanden, Andy; Fahnestock, Mark A.; Truffer, Martin (1 February 2016). "Complex Greenland outlet glacier flow captured". Nature Communications. 7: 10524. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710524A. doi:10.1038/ncomms10524. PMC 4740423. PMID 26830316.

- ^ a b Khan, Shfaqat A.; Bjørk, Anders A.; Bamber, Jonathan L.; Morlighem, Mathieu; Bevis, Michael; Kjær, Kurt H.; Mouginot, Jérémie; Løkkegaard, Anja; Holland, David M.; Aschwanden, Andy; Zhang, Bao; Helm, Veit; Korsgaard, Niels J.; Colgan, William; Larsen, Nicolaj K.; Liu, Lin; Hansen, Karina; Barletta, Valentina; Dahl-Jensen, Trine S.; Søndergaard, Anne Sofie; Csatho, Beata M.; Sasgen, Ingo; Box, Jason; Schenk, Toni (17 November 2020). "Centennial response of Greenland's three largest outlet glaciers". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5718. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5718K. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19580-5. PMC 7672108. PMID 33203883.

- ^ a b Japsen, Peter; Green, Paul F.; Bonow, Johan M.; Nielsen, Troels F.D.; Chalmers, James A. (5 February 2014). "From volcanic plains to glaciated peaks: Burial, uplift and exhumation history of southern East Greenland after opening of the NE Atlantic". Global and Planetary Change. 116: 91–114. Bibcode:2014GPC...116...91J. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.01.012.

- ^ a b Solgaard, Anne M.; Bonow, Johan M.; Langen, Peter L.; Japsen, Peter; Hvidberg, Christine (27 September 2013). "Mountain building and the initiation of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 392: 161–176. Bibcode:2013PPP...392..161S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.09.019.

- ^ Koenig, S. J.; Dolan, A. M.; de Boer, B.; Stone, E. J.; Hill, D. J.; DeConto, R. M.; Abe-Ouchi, A.; Lunt, D. J.; Pollard, D.; Quiquet, A.; Saito, F.; Savage, J.; van de Wal, R. (5 March 2015). "Ice sheet model dependency of the simulated Greenland Ice Sheet in the mid-Pliocene". Climate of the Past. 11 (3): 369–381. Bibcode:2015CliPa..11..369K. doi:10.5194/cp-11-369-2015.

- ^ Yang, Hu; Krebs-Kanzow, Uta; Kleiner, Thomas; Sidorenko, Dmitry; Rodehacke, Christian Bernd; Shi, Xiaoxu; Gierz, Paul; Niu, Lu J.; Gowan, Evan J.; Hinck, Sebastian; Liu, Xingxing; Stap, Lennert B.; Lohmann, Gerrit (20 January 2022). "Impact of paleoclimate on present and future evolution of the Greenland Ice Sheet". PLOS ONE. 17 (1): e0259816. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1759816Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259816. PMC 8776332. PMID 35051173.

- ^ Vinas, Maria-Jose (3 August 2016). "NASA Maps Thawed Areas Under Greenland Ice Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 12 December 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Irvalı, Nil; Galaasen, Eirik V.; Ninnemann, Ulysses S.; Rosenthal, Yair; Born, Andreas; Kleiven, Helga (Kikki) F. (18 December 2019). "A low climate threshold for south Greenland Ice Sheet demise during the Late Pleistocene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (1): 190–195. doi:10.1073/pnas.1911902116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6955352. PMID 31871153.

- ^ a b Schaefer, Joerg M.; Finkel, Robert C.; Balco, Greg; Alley, Richard B.; Caffee, Marc W.; Briner, Jason P.; Young, Nicolas E.; Gow, Anthony J.; Schwartz, Roseanne (7 December 2016). "Greenland was nearly ice-free for extended periods during the Pleistocene". Nature. 540 (7632): 252–255. Bibcode:2016Natur.540..252S. doi:10.1038/nature20146. PMID 27929018. S2CID 4471742.

- ^ Alley, Richard B (2000). The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00493-5.

- ^ a b Gkinis, V.; Simonsen, S. B.; Buchardt, S. L.; White, J. W. C.; Vinther, B. M. (1 November 2014). "Water isotope diffusion rates from the NorthGRIP ice core for the last 16,000 years – Glaciological and paleoclimatic implications". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 405: 132–141. arXiv:1404.4201. Bibcode:2014E&PSL.405..132G. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.08.022.

- ^ a b Adolphi, Florian; Muscheler, Raimund; Svensson, Anders; Aldahan, Ala; Possnert, Göran; Beer, Jürg; Sjolte, Jesper; Björck, Svante; Matthes, Katja; Thiéblemont, Rémi (17 August 2014). "Persistent link between solar activity and Greenland climate during the Last Glacial Maximum". Nature Geoscience. 7 (9): 662–666. Bibcode:2014NatGe...7..662A. doi:10.1038/ngeo2225.

- ^ a b Kurosaki, Yutaka; Matoba, Sumito; Iizuka, Yoshinori; Fujita, Koji; Shimada, Rigen (26 December 2022). "Increased oceanic dimethyl sulfide emissions in areas of sea ice retreat inferred from a Greenland ice core". Communications Earth & Environment. 3 (1): 327. Bibcode:2022ComEE...3..327K. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00661-w. ISSN 2662-4435.

텍스트와 이미지는 Wayback Machine에서 2017년 10월 16일에 보관된 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived에 따라 제공됩니다.

텍스트와 이미지는 Wayback Machine에서 2017년 10월 16일에 보관된 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived에 따라 제공됩니다. - ^ Masson-Delmotte, V.; Jouzel, J.; Landais, A.; Stievenard, M.; Johnsen, S. J.; White, J. W. C.; Werner, M.; Sveinbjornsdottir, A.; Fuhrer, K. (1 July 2005). "GRIP Deuterium Excess Reveals Rapid and Orbital-Scale Changes in Greenland Moisture Origin" (PDF). Science. 309 (5731): 118–121. Bibcode:2005Sci...309..118M. doi:10.1126/science.1108575. PMID 15994553. S2CID 10566001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Zielinski, G. A.; Mayewski, P. A.; Meeker, L. D.; Whitlow, S.; Twickler, M. S.; Morrison, M.; Meese, D. A.; Gow, A. J.; Alley, R. B. (13 May 1994). "Record of Volcanism Since 7000 B.C. from the GISP2 Greenland Ice Core and Implications for the Volcano-Climate System". Science. 264 (5161): 948–952. Bibcode:1994Sci...264..948Z. doi:10.1126/science.264.5161.948. PMID 17830082. S2CID 21695750.

- ^ Fischer, Hubertus; Schüpbach, Simon; Gfeller, Gideon; Bigler, Matthias; Röthlisberger, Regine; Erhardt, Tobias; Stocker, Thomas F.; Mulvaney, Robert; Wolff, Eric W. (10 August 2015). "Millennial changes in North American wildfire and soil activity over the last glacial cycle" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 8 (9): 723–727. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..723F. doi:10.1038/ngeo2495. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Wood, J.R. (21 October 2022). "Other ways to examine the finances behind the birth of Classical Greece". Archaeometry. 65 (3): 570–586. doi:10.1111/arcm.12839.

- ^ McConnell, Joseph R.; Wilson, Andrew I.; Stohl, Andreas; Arienzo, Monica M.; Chellman, Nathan J.; Eckhardt, Sabine; Thompson, Elisabeth M.; Pollard, A. Mark; Steffensen, Jørgen Peder (29 May 2018). "Lead pollution recorded in Greenland ice indicates European emissions tracked plagues, wars, and imperial expansion during antiquity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (22): 5726–5731. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.5726M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721818115. PMC 5984509. PMID 29760088.

- ^ a b c d "Arctic Climate Impact Assessment". Archived from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2006.

- ^ "Arctic Climate Impact Assessment". Union of Concerned Scientists. 16 July 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Vinther, B. M.; Andersen, K. K.; Jones, P. D.; Briffa, K. R.; Cappelen, J. (6 June 2006). "Extending Greenland temperature records into the late eighteenth century" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (D11): D11105. Bibcode:2006JGRD..11111105V. doi:10.1029/2005JD006810. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ Kjeldsen, Kristian K.; Korsgaard, Niels J.; Bjørk, Anders A.; Khan, Shfaqat A.; Box, Jason E.; Funder, Svend; Larsen, Nicolaj K.; Bamber, Jonathan L.; Colgan, William; van den Broeke, Michiel; Siggaard-Andersen, Marie-Louise; Nuth, Christopher; Schomacker, Anders; Andresen, Camilla S.; Willerslev, Eske; Kjær, Kurt H. (16 December 2015). "Spatial and temporal distribution of mass loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet since AD 1900". Nature. 528 (7582): 396–400. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..396K. doi:10.1038/nature16183. hdl:1874/329934. PMID 26672555. S2CID 4468824.

- ^ Frederikse, Thomas; Landerer, Felix; Caron, Lambert; Adhikari, Surendra; Parkes, David; Humphrey, Vincent W.; Dangendorf, Sönke; Hogarth, Peter; Zanna, Laure; Cheng, Lijing; Wu, Yun-Hao (19 August 2020). "The causes of sea-level rise since 1900". Nature. 584 (7821): 393–397. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2591-3. PMID 32814886. S2CID 221182575.

- ^ IPCC, 2007. 트렌버스, K.E., P.D. 존스, P. 암벤제, R. 보자리우, D. Easterling, A. Klein Tank, D. 파커, F. 라힘자데, J.A. 렌윅, M. 러스티쿠치, B. Soden and P. Zhai, 2007: 관측치: 지표 및 대기 기후 변화. 수신인: 기후 변화 2007: 물리 과학의 기초. 기후변화에 관한 정부간 패널의 제4차 평가보고서에 대한 워킹그룹 I의 기여[솔로몬, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. 첸, M. 후작, K.B. 에이버리, M. Tignor와 H.L. Miller (eds)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 영국 Cambridge and New York, New York, USA.[1] 2017년 10월 23일 Wayback Machine에서 보관

- ^ Steffen, Konrad; Cullen, Nicloas; Huff, Russell (13 January 2005). Climate variability and trends along the western slope of the Greenland ice sheet during 1991-2004 (PDF). 85th American Meteorogical Union Annual Meeting. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007.

- ^ a b 2001년 기후변화: 과학적 기초. IPCC(Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change)의 제3차 평가보고서에 대한 워킹그룹 I의 기여[Houghton, J.T., Y. Ding, D.J. Griggs, M. Noguer, P.J. van der Linden, X. Dai, K. Maskell, C.A. Johnson (eds)]Cambridge University Press, 영국 Cambridge and New York, New York, USA, 881pp. [2]2007년 12월 16일 Wayback Machine에서 보관, [3] 2017년 1월 19일 Wayback Machine에서 보관.

- ^ a b c Shepherd, Andrew; Ivins, Erik; Rignot, Eric; Smith, Ben; van den Broeke, Michiel; Velicogna, Isabella; Whitehouse, Pippa; Briggs, Kate; Joughin, Ian; Krinner, Gerhard; Nowicki, Sophie (12 March 2020). "Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2018". Nature. 579 (7798): 233–239. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1855-2. hdl:2268/242139. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31822019. S2CID 219146922. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Record melt: Greenland lost 586 billion tons of ice in 2019". phys.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Bamber, Jonathan L; Westaway, Richard M; Marzeion, Ben; Wouters, Bert (1 June 2018). "The land ice contribution to sea level during the satellite era". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (6): 063008. Bibcode:2018ERL....13f3008B. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aac2f0.

- ^ Xie, Aihong; Zhu, Jiangping; Kang, Shichang; Qin, Xiang; Xu, Bing; Wang, Yicheng (3 October 2022). "Polar amplification comparison among Earth's three poles under different socioeconomic scenarios from CMIP6 surface air temperature". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 16548. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1216548X. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21060-3. PMC 9529914. PMID 36192431.

- ^ Moon, Twila; Ahlstrøm, Andreas; Goelzer, Heiko; Lipscomb, William; Nowicki, Sophie (2018). "Rising Oceans Guaranteed: Arctic Land Ice Loss and Sea Level Rise". Current Climate Change Reports. 4 (3): 211–222. Bibcode:2018CCCR....4..211M. doi:10.1007/s40641-018-0107-0. ISSN 2198-6061. PMC 6428231. PMID 30956936.

- ^ a b c Choi, Youngmin; Morlighem, Mathieu; Rignot, Eric; Wood, Michael (4 February 2021). "Ice dynamics will remain a primary driver of Greenland ice sheet mass loss over the next century". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 26. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2...26C. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00092-z.

텍스트와 이미지는 Wayback Machine에서 2017년 10월 16일에 보관된 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived에 따라 제공됩니다.

텍스트와 이미지는 Wayback Machine에서 2017년 10월 16일에 보관된 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived에 따라 제공됩니다. - ^ Moon, Twila; Joughin, Ian (7 June 2008). "Changes in ice front position on Greenland's outlet glaciers from 1992 to 2007". Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. 113 (F2). Bibcode:2008JGRF..113.2022M. doi:10.1029/2007JF000927.

- ^ a b Sole, A.; Payne, T.; Bamber, J.; Nienow, P.; Krabill, W. (16 December 2008). "Testing hypotheses of the cause of peripheral thinning of the Greenland Ice Sheet: is land-terminating ice thinning at anomalously high rates?". The Cryosphere. 2 (2): 205–218. Bibcode:2008TCry....2..205S. doi:10.5194/tc-2-205-2008. ISSN 1994-0424. S2CID 16539240.

- ^ Shukman, David (28 July 2004). "Greenland ice-melt 'speeding up'". The BBC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Connor, Steve (25 July 2005). "Melting Greenland glacier may hasten rise in sea level". The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 July 2005. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Thomas, Robert H.; Abdalati, Waleed; Akins, Torry L.; Csatho, Beata M.; Frederick, Earl B.; Gogineni, Siva P.; Krabill, William B.; Manizade, Serdar S.; Rignot, Eric J. (1 May 2000). "Substantial thinning of a major east Greenland outlet glacier". Geophysical Research Letters. 27 (9): 1291–1294. Bibcode:2000GeoRL..27.1291T. doi:10.1029/1999GL008473.

- ^ Howat, Ian M.; Ahn, Yushin; Joughin, Ian; van den Broeke, Michiel R.; Lenaerts, Jan T. M.; Smith, Ben (18 June 2011). "Mass balance of Greenland's three largest outlet glaciers, 2000–2010". Geophysical Research Letters. 27 (9). Bibcode:2000GeoRL..27.1291T. doi:10.1029/1999GL008473.

- ^ Barnett, Jamie; Holmes, Felicity A.; Kirchner, Nina (23 August 2022). "Modelled dynamic retreat of Kangerlussuaq Glacier, East Greenland, strongly influenced by the consecutive absence of an ice mélange in Kangerlussuaq Fjord". Journal of Glaciology. 59 (275): 433–444. doi:10.1017/jog.2022.70.

- ^ "Ilulissat Icefjord". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Joughin, Ian; Abdalati, Waleed; Fahnestock, Mark (December 2004). "Large fluctuations in speed on Greenland's Jakobshavn Isbræ glacier". Nature. 432 (7017): 608–610. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..608J. doi:10.1038/nature03130. PMID 15577906. S2CID 4406447.

- ^ a b Pelto.M, Hughes, T, Fastook J., Brecher, H. (1989). "Equilibrium state of Jakobshavns Isbræ, West Greenland". Annals of Glaciology. 12: 781–783. Bibcode:1989AnGla..12..127P. doi:10.3189/S0260305500007084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ a b "Fastest Glacier doubles in Speed". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ^ "Images Show Breakup of Two of Greenland's Largest Glaciers, Predict Disintegration in Near Future". NASA Earth Observatory. 20 August 2008. Archived from the original on 31 August 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ Hickey, Hannah; Ferreira, Bárbara (3 February 2014). "Greenland's fastest glacier sets new speed record". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Rasmussen, Carol (25 March 2019). "Cold Water Currently Slowing Fastest Greenland Glacier". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b Khazendar, Ala; Fenty, Ian G.; Carroll, Dustin; Gardner, Alex; Lee, Craig M.; Fukumori, Ichiro; Wang, Ou; Zhang, Hong; Seroussi, Hélène; Moller, Delwyn; Noël, Brice P. Y.; Van Den Broeke, Michiel R.; Dinardo, Steven; Willis, Josh (25 March 2019). "Interruption of two decades of Jakobshavn Isbrae acceleration and thinning as regional ocean cools". Nature Geoscience. 12 (4): 277–283. Bibcode:2019NatGe..12..277K. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0329-3. hdl:1874/379731. S2CID 135428855.

- ^ "Huge ice island breaks from Greenland glacier". BBC News. 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Iceberg twice the size of Manhattan breaks off Greenland glacier". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The Associated Press. 18 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Åkesson, Henning; Morlighem, Mathieu; Nilsson, Johan; Stranne, Christian; Jakobsson, Martin (9 May 2022). "Petermann ice shelf may not recover after a future breakup". Nature Communications. 13: 2519. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.2519A. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29529-5.

- ^ Enderlin, Ellyn M.; Howat, Ian M.; Jeong, Seongsu; Noh, Myoung-Jong; van Angelen, Jan H.; van den Broeke, Michiel (16 January 2014). "An improved mass budget for the Greenland ice sheet". Geophysical Research Letters. 41 (3): 866–872. Bibcode:2014GeoRL..41..866E. doi:10.1002/2013GL059010.

- ^ Howat, I. M.; Joughin, I.; Tulaczyk, S.; Gogineni, S. (22 November 2005). "Rapid retreat and acceleration of Helheim Glacier, east Greenland". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (22). Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3222502H. doi:10.1029/2005GL024737.

- ^ Nettles, Meredith; Ekström, Göran (1 April 2010). "Glacial Earthquakes in Greenland and Antarctica". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 38 (1): 467–491. Bibcode:2010AREPS..38..467N. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152414. ISSN 0084-6597.

- ^ Kehrl, L. M.; Joughin, I.; Shean, D. E.; Floricioiu, D.; Krieger, L. (17 August 2017). "Seasonal and interannual variabilities in terminus position, glacier velocity, and surface elevation at Helheim and Kangerlussuaq Glaciers from 2008 to 2016" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth's Surface. 122 (9): 1635–1652. Bibcode:2017JGRF..122.1635K. doi:10.1002/2016JF004133. S2CID 52086165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Williams, Joshua J.; Gourmelen, Noel; Nienow, Peter; Bunce, Charlie; Slater, Donald (24 November 2021). "Helheim Glacier Poised for Dramatic Retreat". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (17). Bibcode:2021GeoRL..4894546W. doi:10.1029/2021GL094546.

- ^ Howat, Ian M.; Smith, Ben E.; Joughin, Ian; Scambos, Ted A. (9 September 2008). "Rates of southeast Greenland ice volume loss from combined ICESat and ASTER observations". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (17). Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3517505H. doi:10.1029/2008gl034496. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 3468378.

- ^ Larocca, L. J.; Twining–Ward, M.; Axford, Y.; Schweinsberg, A. D.; Larsen, S. H.; Westergaard–Nielsen, A.; Luetzenburg, G.; Briner, J. P.; Kjeldsen, K. K.; Bjørk, A. A. (9 November 2023). "Greenland-wide accelerated retreat of peripheral glaciers in the twenty-first century". Nature Climate Change. 13 (12): 1324–1328. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13.1324L. doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01855-6.

- ^ Morris, Amanda (9 November 2023). "Greenland's glacier retreat rate has doubled over past two decades". Northwestern University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b Ciracì, Enrico; Rignot, Eric; Scheuchl, Bernd (8 May 2023). "Melt rates in the kilometer-size grounding zone of Petermann Glacier, Greenland, before and during a retreat". PNAS. 120 (20): e2220924120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12020924C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2220924120. PMC 10193949. PMID 37155853.

- ^ Rignot, Eric; Gogineni, Sivaprasad; Joughin, Ian; Krabill, William (1 December 2001). "Contribution to the glaciology of northern Greenland from satellite radar interferometry". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 106 (D24): 34007–34019. Bibcode:2001JGR...10634007R. doi:10.1029/2001JD900071.

- ^ Rignot, E.; Braaten, D.; Gogineni, S.; Krabill, W.; McConnell, J. R. (25 May 2004). "Rapid ice discharge from southeast Greenland glaciers". Geophysical Research Letters. 31 (10). Bibcode:2004GeoRL..3110401R. doi:10.1029/2004GL019474.

- ^ Luckman, Adrian; Murray, Tavi; de Lange, Remko; Hanna, Edward (3 February 2006). "Rapid and synchronous ice-dynamic changes in East Greenland". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (3). Bibcode:2006GeoRL..33.3503L. doi:10.1029/2005gl025428. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 55517773.

- ^ Hughes, T. (1986). "The Jakobshavn Effect". Geophysical Research Letters. 13 (1): 46–48. Bibcode:1986GeoRL..13...46H. doi:10.1029/GL013i001p00046.

- ^ Thomas, Robert H. (2004). "Force-perturbation analysis of recent thinning and acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbræ, Greenland". Journal of Glaciology. 50 (168): 57–66. Bibcode:2004JGlac..50...57T. doi:10.3189/172756504781830321. ISSN 0022-1430. S2CID 128911716.

- ^ Thomas, Robert H.; Abdalati, Waleed; Frederick, Earl; Krabill, William; Manizade, Serdar; Steffen, Konrad (2003). "Investigation of surface melting and dynamic thinning on Jakobshavn Isbrae, Greenland". Journal of Glaciology. 49 (165): 231–239. Bibcode:2003JGlac..49..231T. doi:10.3189/172756503781830764.

- ^ Straneo, Fiammetta; Heimbach, Patrick (4 December 2013). "North Atlantic warming and the retreat of Greenland's outlet glaciers". Nature. 504 (7478): 36–43. Bibcode:2013Natur.504...36S. doi:10.1038/nature12854. PMID 24305146. S2CID 205236826.

- ^ Holland, D M.; Younn, B. D.; Ribergaard, M. H.; Lyberth, B. (28 September 2008). "Acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbrae triggered by warm ocean waters". Nature Geoscience. 1 (10): 659–664. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..659H. doi:10.1038/ngeo316. S2CID 131559096.

- ^ Rignot, E.; Xu, Y.; Menemenlis, D.; Mouginot, J.; Scheuchl, B.; Li, X.; Morlighem, M.; Seroussi, H.; van den Broeke, M.; Fenty, I.; Cai, C.; An, L.; de Fleurian, B. (30 May 2016). "Modeling of ocean-induced ice melt rates of five west Greenland glaciers over the past two decades". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (12): 6374–6382. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43.6374R. doi:10.1002/2016GL068784. hdl:1874/350987. S2CID 102341541.

- ^ Clarke, Ted S.; Echelmeyer, Keith (1996). "Seismic-reflection evidence for a deep subglacial trough beneath Jakobshavns Isbræ, West Greenland". Journal of Glaciology. 43 (141): 219–232. doi:10.3189/S0022143000004081.

- ^ van der Veen, C.J.; Leftwich, T.; von Frese, R.; Csatho, B.M.; Li, J. (21 June 2007). "Subglacial topography and geothermal heat flux: Potential interactions with drainage of the Greenland ice sheet". Geophysical Research Letters. L12501. 34 (12): 5 pp. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3412501V. doi:10.1029/2007GL030046. hdl:1808/17298. S2CID 54213033. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ Joughin, Ian; Shean, David E.; Smith, Benjamin E.; Floricioiu, Dana (24 January 2020). "A decade of variability on Jakobshavn Isbræ: ocean temperatures pace speed through influence on mélange rigidity". The Cryosphere. 14 (1): 211–227. Bibcode:2020TCry...14..211J. doi:10.5194/tc-14-211-2020. PMID 32355554.

- ^ Joughin, Ian; Howat, Ian; Alley, Richard B.; Ekstrom, Goran; Fahnestock, Mark; Moon, Twila; Nettles, Meredith; Truffer, Martin; Tsai, Victor C. (26 January 2008). "Ice-front variation and tidewater behavior on Helheim and Kangerdlugssuaq Glaciers, Greenland". Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. 113 (F1). Bibcode:2008JGRF..113.1004J. doi:10.1029/2007JF000837.

- ^ Miller, Brandon (8 May 2023). "A major Greenland glacier is melting away with the tide, which could signal faster sea level rise, study finds". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Zwally, H. Jay; Abdalati, Waleed; Herring, Tom; Larson, Kristine; Saba, Jack; Steffen, Konrad (12 July 2002). "Surface Melt-Induced Acceleration of Greenland Ice-Sheet Flow". Science. 297 (5579): 218–222. Bibcode:2002Sci...297..218Z. doi:10.1126/science.1072708. PMID 12052902. S2CID 37381126.

- ^ Pelto, M. (2008). "Moulins, Calving Fronts and Greenland Outlet Glacier Acceleration". RealClimate. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Das, Sarah B.; Joughin, Ian; Behn, Mark D.; Howat, Ian M.; King, Matt A.; Lizarralde, Dan; Bhatia, Maya P. (9 May 2008). "Fracture Propagation to the Base of the Greenland Ice Sheet During Supraglacial Lake Drainage". Science. 320 (5877): 778–781. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..778D. doi:10.1126/science.1153360. hdl:1912/2506. PMID 18420900. S2CID 41582882. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Thomas, R.; Frederick, E.; Krabill, W.; Manizade, S.; Martin, C. (2009). "Recent changes on Greenland outlet glaciers". Journal of Glaciology. 55 (189): 147–162. Bibcode:2009JGlac..55..147T. doi:10.3189/002214309788608958.

- ^ a b Slater, D. A.; Straneo, F. (3 October 2022). "Submarine melting of glaciers in Greenland amplified by atmospheric warming". Nature Geoscience. 15 (10): 794–799. Bibcode:2022NatGe..15..794S. doi:10.1038/s41561-022-01035-9.

- ^ Chauché, N.; Hubbard, A.; Gascard, J.-C.; Box, J. E.; Bates, R.; Koppes, M.; Sole, A.; Christoffersen, P.; Patton, H. (8 August 2014). "Ice–ocean interaction and calving front morphology at two west Greenland tidewater outlet glaciers". The Cryosphere. 8 (4): 1457–1468. Bibcode:2014TCry....8.1457C. doi:10.5194/tc-8-1457-2014.

- ^ Morlighem, Mathieu; Wood, Michael; Seroussi, Hélène; Choi, Youngmin; Rignot, Eric (1 March 2019). "Modeling the response of northwest Greenland to enhanced ocean thermal forcing and subglacial discharge". The Cryosphere. 13 (2): 723–734. Bibcode:2019TCry...13..723M. doi:10.5194/tc-13-723-2019.

- ^ Fried, M. J.; Catania, G. A.; Stearns, L. A.; Sutherland, D. A.; Bartholomaus, T. C.; Shroyer, E.; Nash, J. (10 July 2018). "Reconciling Drivers of Seasonal Terminus Advance and Retreat at 13 Central West Greenland Tidewater Glaciers". Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. 123 (7): 1590–1607. Bibcode:2018JGRF..123.1590F. doi:10.1029/2018JF004628.

- ^ Chandler, David M.; Hubbard, Alun (19 June 2023). "Widespread partial-depth hydrofractures in ice sheets driven by supraglacial streams". Nature Geoscience. 37 (20): 605–611. Bibcode:2023NatGe..16..605C. doi:10.1038/s41561-023-01208-0.

- ^ Phillips, Thomas; Rajaram, Harihar; Steffen, Konrad (23 October 2010). "Cryo-hydrologic warming: A potential mechanism for rapid thermal response of ice sheets". Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (15): e2021GL092942. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3720503P. doi:10.1029/2010GL044397. S2CID 129678617.

- ^ Hubbard, Alun (29 June 2023). "Meltwater is infiltrating Greenland's ice sheet through millions of hairline cracks – destabilizing its structure". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Satellite shows Greenland's ice sheets getting thicker". The Register. 7 November 2005. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017.

- ^ Mooney, Chris (29 August 2022). "Greenland ice sheet set to raise sea levels by nearly a foot, study finds". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

As it thaws, scientists think the change will manifest itself at a location called the snow line. This is the dividing line between the high altitude, bright white parts of the ice sheet that accumulate snow and mass even during the summer, and the darker, lower elevation parts that melt and contribute water to the sea. This line moves every year, depending on how warm or cool the summer is, tracking how much of Greenland melts in a given period.

- ^ Ryan, J. C.; Smith, L. C.; van As, D.; Cooley, S. W.; Cooper, M. G.; Pitcher, L. H.; Hubbard, A. (6 March 2019). "Greenland Ice Sheet surface melt amplified by snowline migration and bare ice exposure". Science Advances. 5 (3): 218–222. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.3738R. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav3738. PMC 6402853. PMID 30854432.

- ^ "Glacier Girl: The Back Story". Air & Space Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (14 October 2020). "How investigators found a jet engine under Greenland's ice sheet". CNN Business. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b Lewis, Gabriel; Osterberg, Erich; Hawley, Robert; Marshall, Hans Peter; Meehan, Tate; Graeter, Karina; McCarthy, Forrest; Overly, Thomas; Thundercloud, Zayta; Ferris, David (4 November 2019). "Recent precipitation decrease across the western Greenland ice sheet percolation zone". The Cryosphere. 13 (11): 2797–2815. Bibcode:2019TCry...13.2797L. doi:10.5194/tc-13-2797-2019. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Bales, Roger C.; Guo, Qinghua; Shen, Dayong; McConnell, Joseph R.; Du, Guoming; Burkhart, John F.; Spikes, Vandy B.; Hanna, Edward; Cappelen, John (27 March 2009). "Annual accumulation for Greenland updated using ice core data developed during 2000–2006 and analysis of daily coastal meteorological data" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres. 114 (D6). Bibcode:2009JGRD..114.6116B. doi:10.1029/2008JD011208. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Auger, Jeffrey D.; Birkel, Sean D.; Maasch, Kirk A.; Mayewski, Paul A.; Schuenemann, Keah C. (6 June 2017). "Examination of precipitation variability in southern Greenland". Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres. 122 (12): 6202–6216. Bibcode:2017JGRD..122.6202A. doi:10.1002/2016JD026377.

- ^ Niwano, M.; Box, J. E.; Wehrlé, A.; Vandecrux, B.; Colgan, W. T.; Cappelen, J. (3 July 2021). "Rainfall on the Greenland Ice Sheet: Present-Day Climatology From a High-Resolution Non-Hydrostatic Polar Regional Climate Model". Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (15): e2021GL092942. Bibcode:2021GeoRL..4892942N. doi:10.1029/2021GL092942.

- ^ Doyle, Samuel H.; Hubbard, Alun; van de Wal, Roderik S. W.; Box, Jason E.; van As, Dirk; Scharrer, Kilian; Meierbachtol, Toby W.; Smeets, Paul C. J. P.; Harper, Joel T.; Johansson, Emma; Mottram, Ruth H.; Mikkelsen, Andreas B.; Wilhelms, Frank; Patton, Henry; Christoffersen, Poul; Hubbard, Bryn (13 July 2015). "Amplified melt and flow of the Greenland ice sheet driven by late-summer cyclonic rainfall". Nature Geoscience. 8 (8): 647–653. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..647D. doi:10.1038/ngeo2482. hdl:1874/321802. S2CID 130094002.

- ^ Mattingly, Kyle S.; Ramseyer, Craig A.; Rosen, Joshua J.; Mote, Thomas L.; Muthyala, Rohi (22 August 2016). "Increasing water vapor transport to the Greenland Ice Sheet revealed using self-organizing maps". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (17): 9250–9258. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43.9250M. doi:10.1002/2016GL070424. S2CID 132714399.

- ^ "Greenland enters melt mode". Science News. 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "Arctic Report Card: Update for 2012; Greenland Ice Sheet" (PDF). 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Adam (9 August 2021). "'Massive melting event' torpedoes billions of tons of ice the whole world depends on". The Hill. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Ice cores show that these widespread melt events were really rare prior to the 21st century, but since then, we have had several melt seasons.

- ^ Van Tricht, K.; Lhermitte, S.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; Gorodetskaya, I. V.; L'Ecuyer, T. S.; Noël, B.; van den Broeke, M. R.; Turner, D. D.; van Lipzig, N. P. M. (12 January 2016). "Clouds enhance Greenland ice sheet meltwater runoff". Nature Communications. 7: 10266. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710266V. doi:10.1038/ncomms10266. PMC 4729937. PMID 26756470.

- ^ Mikkelsen, Andreas Bech; Hubbard, Alun; MacFerrin, Mike; Box, Jason Eric; Doyle, Sam H.; Fitzpatrick, Andrew; Hasholt, Bent; Bailey, Hannah L.; Lindbäck, Katrin; Pettersson, Rickard (30 May 2016). "Extraordinary runoff from the Greenland ice sheet in 2012 amplified by hypsometry and depleted firn retention". The Cryosphere. 10 (3): 1147–1159. Bibcode:2016TCry...10.1147M. doi:10.5194/tc-10-1147-2016.

- ^ Bennartz, R.; Shupe, M. D.; Turner, D. D.; Walden, V. P.; Steffen, K.; Cox, C. J.; Kulie, M. S.; Miller, N. B.; Pettersen, C. (3 April 2013). "July 2012 Greenland melt extent enhanced by low-level liquid clouds". Nature. 496 (7443): 83–86. Bibcode:2013Natur.496...83B. doi:10.1038/nature12002. PMID 23552947. S2CID 4382849.

- ^ Revkin, Andrew C. (25 July 2012). "'Unprecedented' Greenland Surface Melt – Every 150 Years?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Meese, D. A.; Gow, A. J.; Grootes, P.; Stuiver, M.; Mayewski, P. A.; Zielinski, G. A.; Ram, M.; Taylor, K. C.; Waddington, E. D. (1994). "The Accumulation Record from the GISP2 Core as an Indicator of Climate Change Throughout the Holocene". Science. 266 (5191): 1680–1682. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1680M. doi:10.1126/science.266.5191.1680. PMID 17775628. S2CID 12059819.

- ^ Sasgen, Ingo; Wouters, Bert; Gardner, Alex S.; King, Michalea D.; Tedesco, Marco; Landerer, Felix W.; Dahle, Christoph; Save, Himanshu; Fettweis, Xavier (20 August 2020). "Return to rapid ice loss in Greenland and record loss in 2019 detected by the GRACE-FO satellites". Communications Earth & Environment. 1 (1): 8. Bibcode:2020ComEE...1....8S. doi:10.1038/s43247-020-0010-1. ISSN 2662-4435. S2CID 221200001.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. - ^ Milman, Oliver (30 July 2021). "Greenland: enough ice melted on single day to cover Florida in two inches of water". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Greenland's vast ice sheet is undergoing a surge in melting...The deluge of melting has reached deep into Greenland's enormous icy interior, with data from the Danish government showing that the ice sheet lost 8.5bn tons of surface mass on Tuesday alone.

- ^ Turner, Ben (2 August 2021). "'Massive melting event' strikes Greenland after record heat wave". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

High temperatures on 28 July caused the third-largest single-day loss of ice in Greenland since 1950; the second and first biggest single-day losses occurred in 2012 and 2019. Greenland's yearly ice loss began in 1990. In recent years it has accelerated to roughly four times the levels before 2000.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (20 August 2021). "Rain falls on peak of Greenland ice cap for first time on record". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Rain has fallen on the summit of Greenland's huge ice cap for the first time on record. Temperatures are normally well below freezing on the 3,216-metre (10,551ft) peak...Scientists at the US National Science Foundation's summit station saw rain falling throughout 14 August but had no gauges to measure the fall because the precipitation was so unexpected.

- ^ Patel, Kasha (19 August 2021). "Rain falls at the summit of Greenland Ice Sheet for first time on record". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Rain fell on and off for 13 hours at the station, but staff are not certain exactly how much rain fell...there are no rain gauges at the summit because no one expected it to rain at this altitude.

- ^ "Sea level rise from ice sheets track worst-case climate change scenario". phys.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Ice sheet melt on track with 'worst-case climate scenario'". www.esa.int. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Slater, Thomas; Hogg, Anna E.; Mottram, Ruth (31 August 2020). "Ice-sheet losses track high-end sea-level rise projections". Nature Climate Change. 10 (10): 879–881. Bibcode:2020NatCC..10..879S. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0893-y. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 221381924. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Box, Jason E.; Hubbard, Alun; Bahr, David B.; Colgan, William T.; Fettweis, Xavier; Mankoff, Kenneth D.; Wehrlé, Adrien; Noël, Brice; van den Broeke, Michiel R.; Wouters, Bert; Bjørk, Anders A.; Fausto, Robert S. (29 August 2022). "Greenland ice sheet climate disequilibrium and committed sea-level rise". Nature Climate Change. 12 (9): 808–813. Bibcode:2022NatCC..12..808B. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01441-2. S2CID 251912711.

- ^ a b c Beckmann, Johanna; Winkelmann, Ricarda (27 July 2023). "Effects of extreme melt events on ice flow and sea level rise of the Greenland Ice Sheet". The Cryosphere. 17 (7): 3083–3099. Bibcode:2023TCry...17.3083B. doi:10.5194/tc-17-3083-2023.

- ^ "WMO verifies −69.6°C Greenland temperature as Northern hemisphere record". World Meteorological Organization. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023.

- ^ Wunderling, Nico; Willeit, Matteo; Donges, Jonathan F.; Winkelmann, Ricarda (27 October 2020). "Global warming due to loss of large ice masses and Arctic summer sea ice". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 5177. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5177W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18934-3. PMC 7591863. PMID 33110092.

- ^ Shukman, David (7 August 2010). "Sea level fears as Greenland darkens". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023.

- ^ Berwyn, Bob (19 April 2018). "What's Eating Away at the Greenland Ice Sheet?". Inside Climate News. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Cook, Joseph M.; Tedstone, Andrew J.; Williamson, Christopher; McCutcheon, Jenine; Hodson, Andrew J.; Dayal, Archana; Skiles, McKenzie; Hofer, Stefan; Bryant, Robert; McAree, Owen; McGonigle, Andrew; Ryan, Jonathan; Anesio, Alexandre M.; Irvine-Fynn, Tristram D. L.; Hubbard, Alun; Hanna, Edward; Flanner, Mark; Mayanna, Sathish; Benning, Liane G.; van As, Dirk; Yallop, Marian; McQuaid, James B.; Gribbin, Thomas; Tranter, Martyn (29 January 2020). "Glacier algae accelerate melt rates on the south-western Greenland Ice Sheet". The Cryosphere. 14 (1): 309–330. Bibcode:2020TCry...14..309C. doi:10.5194/tc-14-309-2020.

- ^ a b Gertner, Jon (12 November 2015). "The Secrets in Greenland's Ice Sheet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023.

- ^ Roe, Gerard H. (2002). "Modelling Precipitation over ice sheets: an assessment using Greenland". Journal of Glaciology. 48 (160): 70–80. Bibcode:2002JGlac..48...70R. doi:10.3189/172756502781831593.

- ^ a b Hopwood, M. J.; Carroll, D.; Browning, T. J.; Meire, L.; Mortensen, J.; Krisch, S.; Achterberg, E. P. (14 August 2018). "Non-linear response of summertime marine productivity to increased meltwater discharge around Greenland". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3256. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3256H. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05488-8. PMC 6092443. PMID 30108210.

- ^ Statham, Peter J.; Skidmore, Mark; Tranter, Martyn (1 September 2008). "Inputs of glacially derived dissolved and colloidal iron to the coastal ocean and implications for primary productivity". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 22 (3): GB3013. Bibcode:2008GBioC..22.3013S. doi:10.1029/2007GB003106. ISSN 1944-9224.

- ^ Bhatia, Maya P.; Kujawinski, Elizabeth B.; Das, Sarah B.; Breier, Crystaline F.; Henderson, Paul B.; Charette, Matthew A. (2013). "Greenland meltwater as a significant and potentially bioavailable source of iron to the ocean". Nature Geoscience. 6 (4): 274–278. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..274B. doi:10.1038/ngeo1746. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ Arendt, Kristine Engel; Nielsen, Torkel Gissel; Rysgaard, Sren; Tnnesson, Kajsa (22 February 2010). "Differences in plankton community structure along the Godthåbsfjord, from the Greenland Ice Sheet to offshore waters". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 401: 49–62. Bibcode:2010MEPS..401...49E. doi:10.3354/meps08368.

- ^ Arrigo, Kevin R.; van Dijken, Gert L.; Castelao, Renato M.; Luo, Hao; Rennermalm, Åsa K.; Tedesco, Marco; Mote, Thomas L.; Oliver, Hilde; Yager, Patricia L. (31 May 2017). "Melting glaciers stimulate large summer phytoplankton blooms in southwest Greenland waters". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (12): 6278–6285. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.6278A. doi:10.1002/2017GL073583.

- ^ Simon, Margit H.; Muschitiello, Francesco; Tisserand, Amandine A.; Olsen, Are; Moros, Matthias; Perner, Kerstin; Bårdsnes, Siv Tone; Dokken, Trond M.; Jansen, Eystein (29 September 2020). "A multi-decadal record of oceanographic changes of the past ~165 years (1850-2015 AD) from Northwest of Iceland". PLOS ONE. 15 (9): e0239373. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1539373S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239373. PMC 7523958. PMID 32991577.

- ^ Oksman, Mimmi; Kvorning, Anna Bang; Larsen, Signe Hillerup; Kjeldsen, Kristian Kjellerup; Mankoff, Kenneth David; Colgan, William; Andersen, Thorbjørn Joest; Nørgaard-Pedersen, Niels; Seidenkrantz, Marit-Solveig; Mikkelsen, Naja; Ribeiro, Sofia (24 June 2022). "Impact of freshwater runoff from the southwest Greenland Ice Sheet on fjord productivity since the late 19th century". The Cryosphere. 16 (6): 2471–2491. Bibcode:2022TCry...16.2471O. doi:10.5194/tc-16-2471-2022.

- ^ a b Christiansen, Jesper Riis; Jørgensen, Christian Juncher (9 November 2018). "First observation of direct methane emission to the atmosphere from the subglacial domain of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 16623. Bibcode:2018NatSR...816623C. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35054-7. PMC 6226494. PMID 30413774.

- ^ Bhatia, Maya P.; Das, Sarah B.; Longnecker, Krista; Charette, Matthew A.; Kujawinski, Elizabeth B. (1 July 2010). "Molecular characterization of dissolved organic matter associated with the Greenland ice sheet". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 74 (13): 3768–3784. Bibcode:2010GeCoA..74.3768B. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2010.03.035. hdl:1912/3729. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Wadham, J. L.; Hawkings, J. R.; Tarasov, L.; Gregoire, L. J.; Spencer, R. G. M.; Gutjahr, M.; Ridgwell, A.; Kohfeld, K. E. (15 August 2019). "Ice sheets matter for the global carbon cycle". Nature Communications. 10: 3567. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.3567W. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-11394-4. PMID 31417076.

- ^ Tarnocai, C.; Canadell, J.G.; Schuur, E.A.G.; Kuhry, P.; Mazhitova, G.; Zimov, S. (June 2009). "Soil organic carbon pools in the northern circumpolar permafrost region". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 23 (2): GB2023. Bibcode:2009GBioC..23.2023T. doi:10.1029/2008gb003327.

- ^ Ryu, Jong-Sik; Jacobson, Andrew D. (6 August 2012). "CO2 evasion from the Greenland Ice Sheet: A new carbon-climate feedback". Chemical Geology. 320 (13): 80–95. Bibcode:2012ChGeo.320...80R. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.05.024.

- ^ Dieser, Markus; Broemsen, Erik L J E; Cameron, Karen A; King, Gary M; Achberger, Amanda; Choquette, Kyla; Hagedorn, Birgit; Sletten, Ron; Junge, Karen; Christner, Brent C (17 April 2014). "Molecular and biogeochemical evidence for methane cycling beneath the western margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet". The ISME Journal. 8 (11): 2305–2316. Bibcode:2014ISMEJ...8.2305D. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.59. PMC 4992074. PMID 24739624.

- ^ Znamínko, Matěj; Falteisek, Lukáš; Vrbická, Kristýna; Klímová, Petra; Christiansen, Jesper R.; Jørgensen, Christian J.; Stibal, Marek (16 October 2023). "Methylotrophic Communities Associated with a Greenland Ice Sheet Methane Release Hotspot". Microbial Ecology. 86 (4): 3057–3067. Bibcode:2023MicEc..86.3057Z. doi:10.1007/s00248-023-02302-x. PMC 10640400. PMID 37843656.

- ^ Hawkings, Jon R.; Linhoff, Benjamin S.; Wadham, Jemma L.; Stibal, Marek; Lamborg, Carl H.; Carling, Gregory T.; Lamarche-Gagnon, Guillaume; Kohler, Tyler J.; Ward, Rachael; Hendry, Katharine R.; Falteisek, Lukáš; Kellerman, Anne M.; Cameron, Karen A.; Hatton, Jade E.; Tingey, Sarah; Holt, Amy D.; Vinšová, Petra; Hofer, Stefan; Bulínová, Marie; Větrovský, Tomáš; Meire, Lorenz; Spencer, Robert G. M. (24 May 2021). "Large subglacial source of mercury from the southwestern margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Nature Geoscience. 14 (5): 496–502. Bibcode:2021NatGe..14..496H. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00753-w.

- ^ Walther, Kelcie (15 July 2021). "As the Greenland Ice Sheet Retreats, Mercury is Being Released From the Bedrock Below". Columbia Climate School. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Jørgensen, Christian Juncher; Søndergaard, Jens; Larsen, Martin Mørk; Kjeldsen, Kristian Kjellerup; Rosa, Diogo; Sapper, Sarah Elise; Heimbürger-Boavida, Lars-Eric; Kohler, Stephen G.; Wang, Feiyue; Gao, Zhiyuan; Armstrong, Debbie; Albers, Christian Nyrop (26 January 2024). "Large mercury release from the Greenland Ice Sheet invalidated". Science Advances. 10 (4). doi:10.1126/sciadv.adi7760.

- ^ Colgan, William; Machguth, Horst; MacFerrin, Mike; Colgan, Jeff D.; van As, Dirk; MacGregor, Joseph A. (4 August 2016). "The abandoned ice sheet base at Camp Century, Greenland, in a warming climate". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (15): 8091–8096. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43.8091C. doi:10.1002/2016GL069688.

- ^ Rosen, Julia (4 August 2016). "Mysterious, ice-buried Cold War military base may be unearthed by climate change". Science Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cabbage, Michael; McCarthy, Leslie; Norton, Karen (20 January 2016). "NASA, NOAA Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Stefan Rahmstorf; Jason E. Box; Georg Feulner; Michael E. Mann; Alexander Robinson; Scott Rutherford; Erik J. Schaffernicht (May 2015). "Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation" (PDF). Nature. 5 (5): 475–480. Bibcode:2015NatCC...5..475R. doi:10.1038/nclimate2554. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Melting Greenland ice sheet may affect global ocean circulation, future climate". Phys.org. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Yang, Qian; Dixon, Timothy H.; Myers, Paul G.; Bonin, Jennifer; Chambers, Don; van den Broeke, M. R.; Ribergaard, Mads H.; Mortensen, John (22 January 2016). "Recent increases in Arctic freshwater flux affects Labrador Sea convection and Atlantic overturning circulation". Nature Communications. 7: 10525. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710525Y. doi:10.1038/ncomms10525. PMC 4736158. PMID 26796579.

- ^ Greene, Chad A.; Gardner, Alex S.; Wood, Michael; Cuzzone, Joshua K. (18 January 2024). "Ubiquitous acceleration in Greenland Ice Sheet calving from 1985 to 2022". Nature. 625 (7995): 523–528. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06863-2. ISSN 0028-0836. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ a b Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ a b Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.