다낭성 난소증후군

Polycystic ovary syndrome| 다낭성 난소증후군 | |

|---|---|

| 기타이름 | 고안드로겐성 아나베이션(HA),[1] 스타인-레벤탈 증후군[2] |

| |

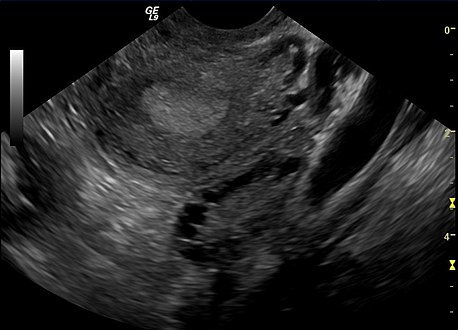

| 다낭성 난소 | |

| 전문 | 부인과, 내분비학 |

| 증상 | 생리불순, 생리중, 과도한 모발, 여드름, 골반통, 임신곤란, 도톰하고 진하고 벨벳 같은 피부[3] 조각 |

| 합병증 | 제2형 당뇨병, 비만, 폐쇄성 수면무호흡증, 심장질환, 기분장애, 자궁내막암[4] |

| 지속 | 장기[5] |

| 원인들 | 유전적, 환경적 요인[6][7] |

| 위험요소 | 비만, 운동부족, 가족력[8] |

| 진단방법 | 배란, 높은 안드로겐 수치, 난소 낭종에[4] 근거하여 |

| 감별진단 | 부신기능항진증, 갑상선기능저하증, 높은 혈중 프로락틴[9] 수치 |

| 치료 | 체중감량, 운동[10][11] |

| 약 | 피임약, 메트포르민, 항안드로겐[12] |

| 빈도수. | 가임기[8][13] 여성의 2~20% |

다낭성 난소 증후군, 또는 다낭성 난소 증후군(PCOS)은 생식기 여성에게 가장 흔한 내분비 질환입니다.[14] 이 증후군은 이 질환을 가진 일부 사람들의 난소에 형성되는 낭종의 이름을 따서 명명되었지만, 이것은 보편적인 증상이 아니며, 질병의 근본적인 원인은 아닙니다.[15][16]

PCOS를 가진 여성들은 불규칙한 생리 기간, 심한 생리 기간, 과도한 모발, 여드름, 골반 통증, 임신의 어려움, 두껍고 어두운 벨벳 같은 피부의 반점을 경험할 수 있습니다.[3] 이 증후군의 주요 특징은 고안드로겐증, 배란, 인슐린 저항성, 신경내분비 교란입니다.[17]

국제적인 증거를 검토한 결과, 일반 인구의 경우 4%에서 18% 사이의 범위가 보고되지만 일부 인구에서는 PCOS의 유병률이 26%까지 높을 수 있음을 발견했습니다.[18][19][20]

PCOS의 정확한 원인은 여전히 불확실하며 치료에는 약물을 사용하여 증상을 관리하는 것이 포함됩니다.[19]

정의.

일반적으로 다음과 같은 두 가지 정의가 사용됩니다.

- NIH

- 로테르담

2003년 로테르담에서 ESHRE/ASRM이 후원한 합의 워크숍에서 PCOS는 세 가지 기준 중 하나라도 충족되면 다음과 같은 결과를 초래할 수 있는 다른 주체가 없는 경우 존재하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[22][23][24]

로테르담의 정의는 더 넓은데, 더 많은 여성을 포함하여 가장 주목할 만한 것은 안드로겐 과잉이 없는 여성입니다. 비판론자들은 안드로겐 과잉이 있는 여성을 대상으로 한 연구에서 얻은 결과를 반드시 안드로겐 과잉이 없는 여성으로 추론할 수는 없다고 말합니다.[25][26]

- 안드로겐 과잉 PCOS 학회

- 2006년 Androgen Excess PCOS Society는 진단 기준을 다음과 같이 강화할 것을 제안했습니다.[22]

- 과잉 안드로겐 활성

- 난포/난포/난포 및/또는 다낭성 난소

- 과잉 안드로겐 활동을 유발할 수 있는 다른 개체의 배제

징후 및 증상

PCOS의 징후와 증상으로는 생리기간이 불규칙하거나 없거나, 생리기간이 많고, 과도한 신체와 얼굴의 털, 여드름, 골반통, 임신곤란, 두껍고 어두운 벨벳 같은 피부,[3] 난소낭종, 난소의 비대, 안드로겐 과다, 체중증가 등이 있습니다.[27][28]

관련 질환으로는 제2형 당뇨병, 비만, 폐쇄성 수면무호흡증, 심장질환, 기분장애, 자궁내막암 등이 있습니다.[4]

PCOS의 일반적인 징후와 증상은 다음과 같습니다.

- 월경장애: PCOS는 대부분 과월경(1년에 9번 이하의 월경기간) 또는 무월경(3개월 이상 연속 월경기간 없음)을 생성하지만 다른 종류의 월경장애도 발생할 수 있습니다.[22]

- 불임: 이것은 일반적으로 만성 배란(배란 부족)에서 직접적으로 발생합니다.[22]

- 남성화 호르몬의 높은 수준: 고안드로겐증이라고 알려진 가장 흔한 증상은 여드름과 다모증(턱이나 가슴 같은 남성의 모발 성장 패턴)이지만, 고월경(무겁고 긴 생리 기간), 안드로겐성 탈모증(털이 가늘어지거나 확산되는 탈모), 또는 다른 증상을 일으킬 수 있습니다.[22][29] PCOS를 가진 여성의 약 4분의 3(NIH/NICD 1990의 진단 기준)은 고안드로겐혈증의 증거를 가지고 있습니다.[30]

- 대사증후군: 이것은 낮은 에너지 수준과 음식 갈망을 포함하여, 중추 비만 및 인슐린 저항성과 관련된 다른 증상에 대한 경향으로 나타납니다.[22] 혈청 인슐린, 인슐린 저항성, 호모시스테인 수치는 PCOS를 가진 여성에서 더 높습니다.[31]

- 여드름: 테스토스테론 수치의 상승, 피지선 내의 기름 생성을 증가시키고 모공을 막습니다.[32] 많은 사람들에게 정서적 영향이 크고 삶의 질이 현저히 떨어질 수 있습니다.[33]

- 안드로겐 알로페시아: 추정 결과 PCOS 환자의 22%에서 안드로겐성 탈모증이 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났습니다.[32] 이것은 디하이드로테스토스테론(DHT) 호르몬으로 전환되는 높은 테스토스테론 수치의 결과입니다. 모낭이 막혀서 머리카락이 빠지고 더 이상의 성장을 막습니다.[34]

- 흑색극세포증(Acanthosis Nigricans): 검고 두껍고 벨벳 같은 패치가 형성될 수 있는 피부 상태([35]141쪽)

- 다낭성 난소: PCOS는 높은 안드로겐 수치, 불규칙한 월경 및/또는 한쪽 또는 양쪽 난소의 작은 낭종을 특징으로 하는 복잡한 장애입니다. 난소는 비대해지고 난자를 둘러싸고 있는 난포를 포함할 수 있습니다. 그 결과 난소가 규칙적으로 기능하지 못할 수 있습니다. 이 질병은 매달 난소당 난포 수가 평균 6-8개에서 2배, 3배 이상으로[citation needed] 증가하는 것과 관련이 있습니다. PCOS를 가진 여성은 불임, 제2형 당뇨병(DM-2), 심혈관 위험, 대사 증후군, 비만, 내당능 장애, 우울증, 폐쇄성 수면 무호흡(OSA), 자궁내막암, 비알코올성 지방간 질환/비알코올성 지방간염(NAFLD/NASH)을 포함한 여러 질병의 위험이 더 높습니다.[36]

PCOS를 가진 여성은 중심부 비만인 경향이 있지만, 같은 체질량지수를 가진 비 PCOS 여성에 비해 PCOS를 가진 여성에서 내장지방과 피하지방이 증가하는지, 변화가 없는지, 감소하는지에 대해서는 연구들이 대립하고 있습니다.[37] 어쨌든 테스토스테론, 안드로스타놀론(디하이드로테스토스테론), 난드롤론 데카노에이트와 같은 안드로겐은 암컷과 여성 모두에서 내장 지방 침착을 증가시키는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[38]

PCOS의 80%가 비만 여성에게 나타나지만, 질병 진단을 받은 여성의 20%는 비만이 아니거나 "날씬한" 여성입니다.[39] 하지만 PCOS를 가지고 있는 비만 여성은 고혈압, 인슐린 저항성, 대사증후군, 자궁내막 비대증과 같은 부작용의 위험이 더 높습니다.[40]

PCOS를 가진 대부분의 여성들이 과체중이거나 비만이라고 할지라도, 비만이 아닌 여성들도 PCOS로 진단될 수 있다는 것을 인정하는 것이 중요합니다. PCOS 진단을 받은 여성의 최대 30%가 진단 전후 정상 체중을 유지하고 있습니다. "Lean" 여성들은 여전히 PCOS의 다양한 증상에 직면해 있으며, 증상을 적절하게 해결하고 인식해야 하는 추가적인 어려움에 직면해 있습니다. 마른 여성들은 수년간 진단을 받지 못한 경우가 많고, 대개 임신에 어려움을 겪은 후 진단을 받습니다.[41] 마른 여성들은 당뇨병과 심혈관 질환에 대한 진단을 놓칠 가능성이 있습니다. 이 여성들은 또한 과체중이 아님에도 불구하고 인슐린 저항성이 발생할 위험이 증가합니다. 마른 여성들은 PCOS 진단에 대해 덜 심각하게 생각하는 경우가 많으며, 적절한 치료 옵션을 찾는 데 어려움을 겪기도 합니다. 대부분의 치료 옵션이 체중 감량과 건강한 다이어트의 접근에 국한되기 때문입니다.[42]

호르몬 수치

테스토스테론 수치는 일반적으로 PCOS를 가진 여성에게서 상승합니다.[43][44] 21개 연구의 PCOS를 가진 5,366명의 여성을 포함한 PCOS 관련 성기능 장애에 대한 2020년 체계적인 검토 및 메타분석에서 테스토스테론 수치가 분석된 결과 PCOS를 가진 여성의 경우 2.34 nmol/L(67 ng/dL), PCOS를 가진 여성의 경우 1.57 nmol/L(45 ng/dL)인 것으로 나타났습니다.[44] 1995년 PCOS를 가진 1,741명의 여성을 대상으로 한 연구에서 평균 테스토스테론 수치는 2.6 nmol/L (75(32-140) ng/dL)였습니다.[45] 많은 연구를 검토하고 메타분석을 실시한 1998년 연구에서 PCOS를 가진 여성의 테스토스테론 수치는 62~71ng/dL(2.2~2.5nmol/L), PCOS를 가진 여성의 테스토스테론 수치는 약 32ng/dL(1.1nmol/L)이었습니다.[46] 테스토스테론을 정량화하기 위해 액체 크로마토그래피-질량분석(LC-MS)을 사용한 PCOS 여성 596명을 대상으로 한 2010년 연구에서 테스토스테론의 중간 수준은 두 개의 다른 실험실을 통해 41 및 47ng/dL (25–75번째 백분위수 34–65ng/dL 및 27–58ng/dL, 12–184ng/dL 및 1–205ng/dL)[47]이었습니다. 테스토스테론 수치가 100~200ng/dL 이상인 경우, 다른 출처에 따라 선천성 부신 비대증 또는 안드로겐 분비 종양과 같은 고안드로겐증의 다른 가능한 원인이 존재할 수 있으므로 제외해야 합니다.[45][48][43] PCOS를 가진 여성의 경우, 난포자극호르몬(FSH)에 대한 황체형성호르몬(LH)의 비율이 일반적으로 2에서 3 사이로 증가하는 반면, 건강한 여성의 경우, 일반적으로 1에서 2 사이의 범위를 유지합니다. 이러한 불균형은 황체형성 호르몬 수치의 증가와 난포자극 호르몬 수치의 감소에 의해 발생합니다.[49]

연관조건

경고 표시에는 외관 변경이 포함될 수 있습니다. 그러나 불안, 우울증, 섭식 장애와 같은 정신 건강 문제의 징후도 있습니다.[27][medical citation needed]

PCOS 진단 결과 다음과 같은 위험이 증가하는 것으로 나타났습니다.

- 자궁내막 과증식과 자궁내막암(자궁내막암)이 발생할 수 있는데, 이는 자궁내막의 과축적, 또한 프로게스테론의 결핍으로 인해 에스트로겐에 의한 자궁세포의 자극이 장기화되기 때문입니다.[21][50] 이 위험이 직접적으로 증후군 때문인지 아니면 연관된 비만, 고인슐린혈증, 고안드로겐증 때문인지는 분명하지 않습니다.[51][52][53]

- 인슐린 저항성/제2형 당뇨병. 2010년에 발표된 한 보고서는 PCOS를 가진 여성들이 체질량지수(BMI)를 조절할 때조차 인슐린 저항성과 제2형 당뇨병의 유병률이 증가한다고 결론지었습니다.[21][54] PCOS는 또한 당뇨병의 높은 위험과 관련이 있습니다.[55]

- 특히 비만이거나 임신 중인[56] 경우 고혈압

- 우울과 불안[22][57]

- 이상지질혈증 – 지질대사의 장애 – 콜레스테롤과 중성지방. PCOS를 가진 여성들은 인슐린 저항성/제2형 당뇨병과 무관한 것으로 보이는 죽상경화증 유발 잔재의 감소된 제거를 보여줍니다.[58]

- 심혈관 질환,[21] 메타 분석은 BMI와 무관하게 PCOS가 없는 여성에 비해 PCOS가 있는 여성의 동맥 질환 위험을 2배로 추정합니다.[59]

- 획수[21]

- 체중증가

- 유산[60][61]

- 수면무호흡증, 특히 비만이 있는 경우

- 특히 비만이 있는 경우 비알코올성 지방간 질환

- 흑색극세포증(팔 아래, 사타구니 부위, 목 뒤쪽에 검게 그을린 피부 패치)[21]

- 자가면역 갑상샘염[citation 필요]

- 철결핍[62]

난소암과 유방암의 위험은 전체적으로 크게 증가하지 않습니다.[50]

원인

PCOS는 원인이 불확실한 이질적인 장애입니다.[63][64] 유전병이라는 몇 가지 증거가 있습니다. 이러한 증거에는 사례의 가족적 군집링, 이진성 쌍둥이와 비교하여 단형성의 더 큰 일치성, PCOS의 내분비 및 대사 특징의 유전성이 포함됩니다.[7][63][64] 자궁 내 안드로겐과 항뮐러 호르몬(AMH)이 일반적인 수준보다 더 많이 노출되면 나중에 PCOS가 발생할 위험이 높아진다는 일부 증거가 있습니다.[65]

유전적 요인과 환경적 요인이 복합적으로 작용하여 발생할 수 있습니다.[6][7][66] 위험 요소에는 비만, 신체 운동 부족, 이 질환을 앓고 있는 사람의 가족력이 포함됩니다.[8] 진단은 배란, 높은 안드로겐 수치, 난소 낭종의 세 가지 소견 중 두 가지를 기준으로 합니다.[4] 초음파로 낭종을 발견할 수 있습니다.[9] 유사한 증상을 일으키는 다른 질환으로는 부신 비대증, 갑상선 기능 저하증, 높은 혈중 프로락틴 수치 등이 있습니다.[9]

유전학

유전적 요소는 상염색체 우성 방식으로 유전되는 것으로 보이며, 여성의 경우 유전적 침투성은 높지만 발현성은 다양합니다. 이는 각 자녀가 부모로부터 유전되기 쉬운 유전적 변이를 물려받을 확률이 50%에 이르고, 딸이 변이를 받으면 어느 정도 딸이 병에 걸릴 수 있다는 것을 의미합니다.[64][67][68][69] 유전자 변이는 아버지 또는 어머니로부터 유전될 수 있으며, PCOS의 징후를 보일 두 아들(무증상 보균자이거나 조기 대머리 및/또는 과도한 모발과 같은 증상이 있을 수 있음)과 딸에게 전달될 수 있습니다.[67][69] 표현형은 적어도 부분적으로 대립유전자를 가진 여성의 난소 난포 세카 세포에 의해 분비되는 증가된 안드로겐 수준을 통해 나타나는 것으로 보입니다.[68] 영향을 받은 정확한 유전자는 아직 밝혀지지 않았습니다.[7][64][70] 드물게 단일 유전자 돌연변이로 인해 증후군의 표현형이 발생할 수 있습니다.[71] 그러나 증후군의 발병기전에 대한 현재의 이해는 그것이 복합적인 다유전성 장애라는 것을 암시합니다.[72]

대규모 선별 연구의 부족으로 인해 PCOS에서 자궁내막 이상의 유병률은 알려지지 않았지만 이 질환을 가진 여성은 자궁내막 비대증 및 암종, 월경 기능 장애 및 불임의 위험이 증가할 수 있습니다.

PCOS 증상의 중증도는 비만 등의 요인에 의해 크게 결정되는 것으로 보입니다.[7][22][73] PCOS는 증상이 부분적으로 가역적이기 때문에 대사 장애의 일부 측면을 가지고 있습니다. 부인과적인 문제로 고려하더라도 PCOS는 28가지 임상 증상으로 구성되어 있습니다.[74]

난소가 질병 병리의 중심이라고 이름이 알려주긴 하지만, 낭종은 질병의 원인이 아니라 하나의 증상입니다. 양쪽 난소를 제거해도 일부 PCOS 증상은 지속되고 낭종이 없어도 병이 나타날 수 있습니다. 1935년 Stein and Leventhal이 처음 기술한 이후 진단 기준, 증상, 원인 요인 등이 논쟁의 대상이 되고 있습니다. 산부인과 의사들은 종종 그것을 부인과적인 문제로 보고 난소가 주요한 영향을 받는 기관입니다. 그러나 최근의 통찰력은 다계통 장애를 보여주는데, 주요 문제는 시상하부의 호르몬 조절에 있으며, 많은 장기가 관련되어 있습니다. PCOS라는 용어는 가능한 증상의 범위가 넓기 때문에 사용됩니다. PCOS가 없는 다낭성 난소는 일반적인데, 유럽 여성의 약 20%가 다낭성 난소를 가지고 있지만 대부분의 여성은 PCOS가 없습니다.[15]

환경

PCOS는 산전 기간 동안의 노출[clarification needed],[75][76][77] 후성 유전적 요인, 환경 영향(특히 비스페놀 A 및 특정 약물과 같은 산업적 내분비 교란 물질)[78][79][80] 및 증가하는 비만율과 관련되거나 악화될 수 있습니다.[79]

내분비계 장애물질은 에스트로겐과 같은 호르몬을 모방하여 내분비계를 방해할 수 있는 화학물질로 정의됩니다. NIH (국립보건원)에 따르면, 내분비 교란 물질의 예로는 다이옥신과 트리클로산이 있을 수 있다고 합니다. 내분비 교란 물질은 동물에게 건강에 나쁜 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. [81] 내분비 교란 물질이 여성의 생식 건강을 방해하고 PCOS 및 관련 증상을 유발하거나 악화시키는 역할을 평가하기 위해서는 추가 연구가 필요합니다.[82]

병인

다낭성 난소는 난소가 과도한 양의 안드로겐 호르몬, 특히 테스토스테론을 생성하도록 자극을 받으면 발생합니다.[68]

PCOS를 가진 여성의 대다수는 인슐린 저항성을 가지고 있거나 비만이며, 이는 인슐린 저항성의 강력한 위험 요소입니다. 그러나 인슐린 저항성은 정상 체중 여성에서도 PCOS를 가진 여성들 사이에서 흔한 발견입니다.[10][22][31] 높아진 인슐린 수치는 PCOS로 이어지는 시상하부-뇌하수체-난소 축에서 볼 수 있는 이상에 기여하거나 유발합니다. 고인슐린혈증은 GnRH 펄스 주파수를 증가시키며,[83] 이는 결과적으로 LH/FSH 비율의[83][84] 증가로 난소 안드로겐 생산 증가, 난포 성숙 감소, SHBG 결합 감소를 초래합니다.[83] 또한 인슐린이 과다하면 17α-하이드록실라아제의 활성이 증가하여 프로게스테론이 안드로스테론으로 전환되고, 이는 다시 테스토스테론으로 전환되는 것을 촉매합니다. 고인슐린혈증의 복합적인 영향은 PCOS의 위험 증가에 기여합니다.[83]

지방 조직은 안드로스텐디온을 에스트론으로, 테스토스테론을 에스트라디올로 전환시키는 효소인 아로마타제를 가지고 있습니다. 비만 여성의 과도한 지방 조직은 과도한 안드로겐(항모증 및 바이러스화의 원인이 됨)과 과도한 에스트로겐(부정적 피드백을 통해 FSH를 억제함)을 모두 갖는 역설을 만듭니다.[85]

이 증후군은 다발성 난소 낭종의 초음파 검사에서 일반적인 징후로 인해 가장 널리 사용되는 이름을 얻었습니다. 이 "낭종"은 사실 미성숙 난소 난포입니다. 난포는 원시 난포에서 발달했지만, 난소 기능의 장애로 인해 초기 단계에서 발달이 중단되었습니다. 난포는 난소 주변을 따라 배열되어 초음파 검사에서 '진주의 끈'으로 나타날 수 있습니다.[86]

PCOS는 만성 염증과 관련이 있을 수 있으며,[87] 여러 조사자가 염증 매개체를 배란 및 기타 PCOS 증상과 연관시킵니다.[88][89] 마찬가지로, PCOS와 증가된 산화 스트레스 사이에도 관계가 있는 것 같습니다.[90]

진단.

PCOS를 가진 모든 사람이 다낭성 난소(PCO)를 가지고 있는 것도 아니고 난소 낭종을 가진 모든 사람이 PCOS를 가지고 있는 것도 아닙니다. 골반 초음파가 주요 진단 도구이지만 그것만이 유일한 것은 아닙니다.[91] 로테르담 기준으로 진단이 비교적 간단합니다. 증후군이 다양한 증상을 동반하는 경우에도 말입니다.[92]

- 다낭성 난소의 질경하 초음파 검사

- 초음파 검사에서 볼 수 있는 다낭성 난소

감별진단

갑상선 기능 저하증, 선천성 부신 비대증(21-하이드록실라제 결핍증), 쿠싱 증후군, 고프로락틴혈증(배란으로 이어지는), 안드로겐 분비 신생물, 그리고 다른 뇌하수체나 부신 장애들을 조사해야 합니다.[22][24][93]

평가 및 테스트

표준평가

- 특히 월경 패턴, 비만, 다모증 및 여드름에 대한 역사 기록. 임상 예측 규칙에 따르면 이 네 가지 질문은 민감도 77.1%(95% 신뢰 구간 [CI] 62.7%–88.0%) 및 특이도 93.8%(95% CI 82.8%–98.7%)[94]로 PCOS를 진단할 수 있습니다.

- 부인과 초음파 검사, 특히 작은 난소 난포를 찾고 있습니다. 이것들은 배란 실패와 함께 난소 기능의 장애로 인한 결과로 여겨지며, 이 질환의 전형적인 월경이 드물거나 없는 것으로 반영됩니다. 정상적인 생리 주기에서, 하나의 난자는 지배적인 난포에서 방출되는데, 본질적으로, 난자를 방출하기 위해 파열되는 낭종입니다. 배란 후 난포 잔해는 프로게스테론을 생성하는 황체로 변형되며, 이 황체는 약 12-14일 후에 수축하여 사라집니다. PCOS에서는 이른바 "포낭 정지(follicular strupt)"가 있는데, 즉, 여러 포낭이 5-7 mm 크기로 발달하지만 그 이상은 아닙니다. 배란 전 크기(16 mm 이상)에 도달하는 단일 난포는 없습니다. PCOS 진단에 널리 사용되는 로테르담 기준에 따르면 초음파 검사에서 의심 난소에서 12개 이상의 작은 난포를 봐야 합니다.[10][21] 더 최근의 연구에 따르면 18-35세 여성의 다낭성 난소 형태(PCOM)로 지정하려면 난소에 최소 25개의 난포가 있어야 합니다.[95] 난포는 주변부에 방향을 잡아 '진주 줄'처럼 보일 수 있습니다.[96] 고해상도의 질초음파 검사기를 사용할 수 없는 경우 최소 10 ml의 난소 부피는 다낭성 난소 형태를 갖는 것으로 허용되는 정의로 간주됩니다. 여포 수보다는.[95]

- 복강경 검사를 통해 난소의 외부 표면이 두꺼워지고 매끄럽고 진주백색으로 변할 수 있습니다. (PCOS 진단을 확인하기 위해 이런 방식으로 난소를 검사하는 것은 일상적이지 않기 때문에, 이것은 다른 이유로 복강경 검사가 시행된 경우 일반적으로 부수적인 소견일 것입니다.)[97]

- 안드로스텐디온 및 테스토스테론을 포함한 안드로겐의 혈청(혈액) 수치가 상승할 수 있습니다.[22] 700-800 µg/dL 이상의 데히드로에피안드로스테론 황산염(DHEA-S) 수치는 DHEA-S가 부신에 의해 독점적으로 만들어지기 때문에 부신 기능 장애를 매우 암시합니다. 테스토스테론 유리 수치는 PCOS 환자의 약 60%가 초정상 수치를 보일 [93][99]정도로 최선의 척도로 여겨집니다.[30]

일부 다른 혈액 검사는 암시적이지만 진단적이지 않습니다. 간 단위로 측정했을 때, LH(황체형성호르몬) 대 FSH(난포자극호르몬)의 비율은 PCOS를 가진 여성에서 증가합니다. 비정상적으로 높은 LH/FSH 비율을 지정하기 위한 일반적인 컷오프는 월경 주기 3일째에 테스트한 대로 2:1[100] 또는 3:1입니다[93]. 한 연구에서 PCOS를 가진 여성의 50% 미만에서 2:1 이상의 비율이 나타났기 때문에 패턴은 그다지 민감하지 않습니다.[100] 특히 비만이거나 과체중인 여성들 사이에서 [93]성호르몬 결합 글로불린의 수치가 낮은 경우가 많습니다.[101] 항 뮐러 호르몬(AMH)은 PCOS에서 증가되어 진단 기준의 일부가 될 수 있습니다.[102][103][104]

내당능시험

- 위험인자(비만, 가족력, 임신성 당뇨병 병력)[22]가 있는 여성의 2시간 경구 포도당 내성 검사(GTT)는 PCOS가 있는 여성의 15-33%에서 포도당 내성(인슐린 저항성) 장애를 나타낼 수 있습니다.[93] 프랭크 당뇨병은 이 질환을 가진 여성의 65-68%에서 볼 수 있습니다.[105] 인슐린 저항성은 정상 체중과 과체중 모두에서 관찰될 수 있지만 후자(및 진단을 위한 더 엄격한 NIH 기준과 일치하는 사람들)에서는 더 흔합니다. PCOS를 가진 사람의 50-80%는 어느 수준에서 인슐린 저항성을 가질 수 있습니다.[22]

- 단식 인슐린 수치 또는 인슐린 수치가 있는 GTT(IGTT라고도 함). 높아진 인슐린 수치는 약물에 대한 반응을 예측하는 데 도움이 되었으며, 여성의 경우 더 높은 용량의 메트포르민이 필요하거나 인슐린 수치를 현저히 낮추기 위해 두 번째 약물을 사용해야 함을 나타낼 수 있습니다. 높아진 혈당과 인슐린 수치는 인슐린을 낮추는 약, 저혈당 식단, 운동에 누가 반응하는지를 예측하지 못합니다. 정상 수치를 가진 많은 여성들이 복합 요법의 혜택을 받을 수 있습니다. 단식보다 2시간 인슐린 수치가 높고 혈당이 낮은 저혈당 반응이 인슐린 저항성과 일치합니다. HOMAI는 글루코스 및 인슐린 농도의 공복 값으로부터 계산된 수학적 유도로 인슐린 민감도를 직접적이고 적당히 정확하게 측정할 수 있습니다(글루코스 수준 x 인슐린 수준/22.5).[106]

관리

PCOS는 치료법이 없습니다.[5] 치료에는 체중 감소 및 운동과 같은 생활 습관 변화가 포함될 수 있습니다.[10][11]

최근 연구에 따르면 유산소 활동과 근력 활동을 모두 포함한 매일의 운동이 호르몬 불균형을 개선할 수 있다고 합니다.[107]

피임약은 주기의 규칙성, 과도한 모발 성장, 여드름을 개선하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[12] 복합 경구피임제는 특히 효과적이며 여드름과 다모증을 줄이고 생리 주기를 조절하는 치료의 1차 치료제로 사용됩니다. 특히 청소년의 경우가 그렇습니다.[107]

메트포르민과 항안드로겐도 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[12] 다른 전형적인 여드름 치료 및 제모 기술을 사용할 수 있습니다.[12] 생식력 향상을 위한 노력으로는 클로미펜이나 레트로졸을 이용한 체중 감량, 메트포르민, 배란 유도 등이 있습니다.[108] 체외 수정은 다른 조치가 효과적이지 않은 일부 사람들에 의해 사용됩니다.[108]

특정 미용 시술은 경우에 따라 증상을 완화하는 데 도움이 될 수도 있습니다. 예를 들어, 레이저 제모, 전기 분해 또는 일반 왁스, 뽑기 및 면도를 사용하는 것은 모두 다 털을 줄이는 효과적인 방법입니다.[35] PCOS의 주요 치료법에는 생활 습관 변화와 약물 사용이 포함됩니다.[109]

치료 목표는 다음과 같은 네 가지 범주로 고려될 수 있습니다.[citation needed]

이러한 각 분야에서 최적의 치료법에 대해서는 상당한 논쟁이 있습니다. 논쟁의 주요 요인 중 하나는 서로 다른 치료법을 비교하는 대규모 임상시험이 없다는 것입니다. 소규모 시행은 신뢰성이 떨어지는 경향이 있으므로 상충되는 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다. 체중이나 인슐린 저항성을 줄이는 데 도움이 되는 일반적인 개입은 근본적인 원인을 해결하기 때문에 이러한 모든 목적에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[110] PCOS는 상당한 정서적 고통을 유발하는 것으로 나타나므로 적절한 지원이 유용할 수 있습니다.[111]

다이어트

PCOS가 과체중 또는 비만과 관련이 있는 경우, 성공적인 체중 감량은 정상적인 배란/월경을 회복시키는 가장 효과적인 방법입니다. 미국 임상 내분비학회 지침은 인슐린 저항성과 모든[clarification needed] 호르몬 장애를 개선하는 10~15% 이상 체중 감소를 달성하는 목표를 제시하고 있습니다.[112] 여전히, 많은 여성들은 상당한 체중 감소를 달성하고 지속하는 것이 매우 어렵다는 것을 알고 있습니다. 인슐린 저항성 자체가 음식 갈망을 증가시키고 에너지 수치를 낮춰 주기 때문에 규칙적인 체중 감량 식단으로 체중을 감량하기 어려울 수 있습니다. 2013년 과학적 검토에 따르면 체중, 신체 구성 및 임신률, 월경 규칙성, 배란, 고안드로겐증, 인슐린 저항성, 지질 및 삶의 질이 식단 구성과 무관하게 체중 감소와 함께 발생하는 유사한 개선을 발견했습니다.[113] 그럼에도 불구하고, 총 탄수화물의 상당 부분을 과일, 채소 및 통곡물 공급원에서 얻는 낮은 GI 식단은 다량 영양소가 일치하는 건강 식단보다 월경 규칙성이 더 높아졌습니다.[113]

유제품, 설탕, 단순 탄수화물과 같이 염증을 유발하는 식품군의 섭취를 줄이는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다.[35]

지중해식 식단은 항염증 및 항산화 특성으로 인해 종종 매우 효과적입니다.[107]

비타민 D 결핍은 대사증후군의 발생에 어느 정도 역할을 할 수 있으며, 그러한 결핍의 치료를 나타냅니다.[114][115] 그러나 2015년의 체계적인 검토에서는 비타민 D 보충이 PCOS의 대사 및 호르몬 조절 장애를 감소시키거나 완화시킨다는 증거를 발견하지 못했습니다.[116] 2012년 현재, PCOS를 가진 사람들의 대사 결핍을 교정하기 위해 식이 보충제를 사용한 중재는 소규모, 통제되지 않은, 그리고 무작위적이지 않은 임상 시험에서 시험되었습니다. 결과 데이터는 그 사용을 권장하기에 불충분합니다.[117]

의약품

PCOS용 약물에는 경구 피임약과 메트포르민이 포함됩니다. 경구피임제는 성호르몬 결합 글로불린 생성을 증가시켜 유리 테스토스테론의 결합을 증가시킵니다. 이는 높은 테스토스테론으로 인한 다모증 증상을 줄이고 정상적인 생리 기간으로의 복귀를 조절합니다.[114] 피나스테리드, 플루타미드, 스피로놀락톤, 비카루타미드 등의 항안드로겐은 경구피임제에 비해 장점을 보이지 않지만 이를 견디지 못하는 사람들에게는 선택지가 될 수 있습니다.[118] FDA 승인을 받은 안드로겐성 탈모증 치료용 경구제는 피나스테리드가 유일합니다.[35]

메트포르민은 인슐린 저항성을 줄이기 위해 제2형 당뇨병에 일반적으로 사용되는 약물이며, PCOS에서 볼 수 있는 인슐린 저항성을 치료하기 위해 (영국, 미국, AU 및 EU에서) 라벨 외로 사용됩니다. 또한 메트포르민은 난소의 기능을 지원하여 정상적인 배란으로 돌아오는 경우도 많습니다.[114][119] 새로운 인슐린 저항성 약물 클래스인 티아졸리딘디온(글리타존)은 메트포르민과 동등한 효능을 보였으나 메트포르민은 더 유리한 부작용 프로필을 가지고 있습니다.[120][121] 영국 국립보건임상우수연구소는 2004년 PCOS와 체질량지수가 25 이상인 여성에게 다른 치료법이 효과를 내지 못했을 때 메트포르민을 투여할 것을 권고했습니다.[122][123] 메트포르민은 모든 유형의 PCOS에서 효과가 없을 수 있으므로 일반적인 1차 요법으로 사용해야 하는지에 대해서는 약간의 의견 차이가 있습니다.[124] 이 외에도 메트포르민은 복통, 입안의 금속성 맛, 설사, 구토 등 여러 가지 불쾌한 부작용과 관련이 있습니다.[125] 메트포르민은 임신 중에 사용해도 안전할 것으로 생각됩니다(미국에서는 임신 카테고리 B).[126] 2014년의 한 리뷰는 메트포르민의 사용이 임신 1기 동안 메트포르민으로 치료된 여성의 주요 선천적 결함의 위험을 증가시키지 않는다고 결론지었습니다.[127] 리라글루타이드는 PCOS를 가진 사람들의 체중과 허리둘레를 다른 약물보다 더 줄일 수 있습니다.[128] 근본적인 대사증후군의 관리에 스타틴의 사용은 여전히 불분명합니다.[109]

PCOS는 불규칙한 배란을 일으키기 때문에 임신이 어려울 수 있습니다. 임신을 시도할 때 생식력을 유도하는 약물로는 배란 유도제인 클로미펜이나 맥동성 류프로렐린이 있습니다. 무작위 대조군 실험의 증거에 따르면, 출생의 측면에서 메트포르민은 위약보다 더 나을 수 있고, 메트포르민과 클로미펜은 클로미펜 단독보다 더 나을 수 있지만, 두 경우 모두 여성은 메트포르민으로 위장 부작용을 경험할 가능성이 더 높을 수 있습니다.[129]

불임

PCOS를 가진 모든 여성이 임신에 어려움을 겪는 것은 아닙니다. 그러나 PCOS를 가진 일부 여성들은 몸이 규칙적인 배란에 필요한 호르몬을 생성하지 않기 때문에 임신에 어려움을 겪을 수 있습니다.[130] PCOS는 또한 유산이나 조기 분만의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있습니다. 하지만 정상적인 임신은 가능합니다. 의료 및 건강한 생활 방식을 포함합니다.[citation needed]

그렇게 하는 사람들에게는 배란이나 드물게 배란하는 것이 흔한 원인이고 PCOS는 배란 불임의 주요 원인입니다.[131] 다른 요인으로는 성선 자극 호르몬 수치의 변화, 고안드로겐혈증, 고인슐린혈증 등이 있습니다.[132] PCOS가 없는 여성과 마찬가지로 배란 중인 PCOS가 있는 여성도 성병 병력으로 인한 관막 막힘 등 다른 원인으로 불임이 될 수 있습니다.[133]

PCOS가 있는 과체중의 배란 여성의 경우 체중 감소와 식단 조절, 특히 단순 탄수화물 섭취를 줄이기 위한 조절이 자연 배란의 재개와 관련이 있습니다.[134] 디지털 건강 개입은 라이프스타일 변화와 약물 투여를 통해 PCOS를 관리하는 복합 요법을 제공하는 데 특히 효과적인 것으로 나타났습니다.[citation needed]

페마라는 FSH 수치를 높이고 난포의 발달을 촉진하는 대체 의약품입니다.[35]

체중 감량 후에도 여전히 배란기인 여성이나 배란기가 없는 마른 여성의 경우 레트로졸이나 시트르산 클로미펜을 사용한 배란 유도가 배란을 촉진하는 데 사용되는 주요 치료법입니다.[135][136][137] 클로미펜은 어떤 사람들에게는 기분 전환과 복부 경련을 일으킬 수 있습니다.[35]

이전에는 항당뇨 치료제 메트포르민이 배란 치료제로 권장됐지만 레트로졸이나 클로미펜에 비해 효과가 떨어지는 것으로 보입니다.[138][139]

레트로졸이나 클로미펜, 식이요법 및 생활습관 수정에 반응하지 않는 여성의 경우 난포 자극 호르몬(FSH) 주사 후 체외 수정(IVF)을 통한 난소 과자극 조절과 같은 보조 생식 기술 절차를 포함한 선택 사항이 있습니다.[140]

수술이 일반적으로 시행되지는 않지만 다낭성 난소는 복강경 수술인 "난소 천공"(전기소아, 레이저 또는 생검 바늘로 4-10개의 작은 난포를 뚫는 것)로 치료할 수 있으며, 이는 종종 클로미펜 또는 FSH로 보조 치료한 후 자발적인[114] 배란을 재개하거나 배란을 재개하는 결과를 가져옵니다.[141] (난소 쐐기 절제술은 유착과 같은 합병증과 자주 효과적인 약물의 존재로 인해 더 이상 많이 사용되지 않습니다.) 그러나 난소 천공이 난소 기능에 미치는 장기적인 영향에 대한 우려가 있습니다.[114]

멘탈 헬스

PCOS를 가진 여성이 그렇지 않은 여성보다 우울증을 가질 가능성이 훨씬 더 높지만 PCOS를 가진 여성의 항우울제 사용에 대한 증거는 아직 결정적이지 않습니다.[142] 그러나 PCOS 중 우울증과 정신적 스트레스의 병태생리는 스트레스 중 친염증성 표지자의 높은 활동성, 면역체계와 같은 심리적 변화를 포함한 다양한 변화와 연관되어 있습니다.[143]

PCOS는 불안, 양극성 장애, 강박 장애와 같은 우울증 외에 다른 정신 건강 관련 질환과 관련이 있습니다.[33]

다모증과 여드름

적절한 경우(예를 들어 피임이 필요한 가임기 여성의 경우) 표준 피임약은 종종 다모증 감소에 효과적입니다.[114] 노어스트렐, 레보노어스트렐과 같은 프로게스토겐은 안드로겐 효과 때문에 피해야 합니다.[114] 메트포르민은 경구피임제와 병용하는 것이 메트포르민이나 경구피임제 자체보다 더 효과적일 수 있습니다.[144]

여드름 치료제를 복용하는 경우, 켈리 모로-배즈 박사는 'PCOS로 번창하다'라는 제목의 설명에서 "약물이 호르몬 수치를 조정하는 데 시간이 걸리고 호르몬 수치가 조정되면, 기공이 과도하게 생성된 오일을 제거하고 피부 아래의 세균 감염이 제거되기 전에 눈에 띄는 결과를 보기 전에 더 많은 시간이 걸립니다."(p.138)

항안드로겐 효과가 있는 다른 약물로는 플루타미드,[145] 스피로놀락톤 등이 있는데,[114] 이는 다모증을 다소 개선시킬 수 있습니다. 메트포르민은 아마도 인슐린 저항성을 감소시킴으로써 다모증을 감소시킬 수 있으며, 인슐린 저항성, 당뇨병 또는 비만과 같이 메트포르민의 혜택을 받아야 하는 다른 특징이 있는 경우 종종 사용됩니다. 에플로르니틴(Vaniqa)은 크림 형태로 피부에 바르는 약으로 모낭에 직접 작용해 모발 성장을 억제합니다. 일반적으로 얼굴에 바릅니다.[114] 5-알파 환원효소 억제제(피나스테리드, 두타스테리드 등)도 사용할 수 있습니다.[146] 테스토스테론이 디하이드로테스토스테론으로 전환되는 것을 차단함으로써 작용합니다.

이러한 약제들이 임상 시험에서 상당한 효능을 보여주었지만(구강 피임약의 경우, 개인의[114] 60-100%에서), 모발 성장의 감소는 다모증의 사회적인 당혹감, 또는 뽑거나 면도하는 불편함을 없애기에 충분하지 않을 수 있습니다. 개인마다 다양한 치료법에 대한 반응이 다릅니다. 효과가 없다면 보통 다른 약을 사용해 볼 가치가 있지만, 약이 모든 사람에게 효과가 있는 것은 아닙니다.[147]

월경불순

불임이 주된 목적이 아니라면, 대개 피임약으로 월경을 조절할 수 있습니다.[114] 생리를 조절하는 목적은 본질적으로 여성의 편의와 아마도 그녀의 행복감을 위한 것입니다. 충분히 자주 발생하는 한 정기적인 생리에 대한 의료 요구 사항은 없습니다.[148]

규칙적인 생리 주기를 원하지 않는 경우 불규칙한 주기에 대한 치료가 반드시 필요한 것은 아닙니다. 대부분의 전문가들은 적어도 3개월에 한 번씩 생리 출혈이 발생하면 자궁내막 이상이나 암 발생 위험이 높아지는 것을 막기 위해 충분히 자주 자궁내막(모직물)을 배출하고 있다고 말합니다.[149] 만약 생리가 덜 자주 발생하거나 전혀 발생하지 않는다면, 어떤 형태로든 프로게스토겐 교체가 권장됩니다.[146]

대체의학

2017년의 리뷰는 myo-inositol과 D-chiro-inositol 모두 월경 주기를 조절하고 배란을 개선할 수 있지만 임신 확률에 대한 영향에 관한 증거는 부족하다고 결론지었습니다.[150][151] 2012년과 2017년의 리뷰에 따르면 미오이노시톨 보충제는 PCOS의 호르몬 장애 중 몇 가지를 개선하는 데 효과적인 것으로 나타났습니다.[152][153] Myo-inositol은 체외 수정을 받는 여성의 성선 자극 호르몬의 양과 난소 과자극 기간을 감소시킵니다.[154] 2011년 검토에서는 D-chiro-inositol로부터 유익한 효과를 결론짓기에는 충분한 증거를 찾지 못했습니다.[155] 침술의 사용을 뒷받침할 증거가 부족하고, 현재 연구는 결정적이지 않으며, 추가적인 무작위 대조 시험이 필요합니다.[156][157]

역학

PCOS는 18세에서 44세 사이의 여성들에게 가장 흔한 내분비 질환입니다.[22] 정의에 따라 이 연령대의 약 2%에서 20%까지 영향을 미칩니다.[8][13] 배란 부족으로 불임이 되면 PCOS가 가장 흔한 원인이며 환자의 진단을 유도할 수 있습니다.[4] 현재 PCOS로 인식되고 있는 것에 대한 가장 초기의 설명은 1721년 이탈리아에서 시작되었습니다.[158]

PCOS의 유병률은 진단 기준의 선택에 따라 달라집니다. 세계보건기구(WHO)는 2010년 기준 전 세계 여성 1억 1천 600만 명(여성의 3.4%)에게 영향을 미치는 것으로 추정하고 있습니다.[159] 또 다른 추정치는 생식기 여성의 7%가 영향을 받고 있다는 것을 나타냅니다.[160] 로테르담 기준을 이용한 또 다른 연구에서는 여성의 약 18%가 PCOS를 가지고 있으며, 이 중 70%는 이전에 진단되지 않은 것으로 나타났습니다.[22] 대규모 과학 연구의 부족으로 인해 국가마다 유병률도 다릅니다. 예를 들어 인도는 PCOS를 가진 여성 5명 중 1명의 비율로 알려져 있습니다.[161]

PCOS를 가진 여성의 심장 대사 인자의 인종적 차이를 조사한 연구는 거의 없습니다. PCOS를 가진 청소년과 젊은 성인의 대사증후군과 심혈관 질환 위험의 인종적 차이에 대한 자료도 제한적입니다.[162] 인종적 차이를 종합적으로 조사한 첫 번째 연구에서 심혈관 질환 위험인자에서 눈에 띄는 인종적 차이를 발견했습니다. 아프리카계 미국인 여성은 PCOS를 가진 백인 성인 여성에 비해 대사증후군 유병률이 현저히 높은 것으로 나타났습니다.[163] PCOS에 영향을 받는 모든 여성이 관리할 수 있는 자원을 가지고 있는지 확인하는 것은 PCOS를 가진 여성들 사이의 인종적 차이에 대한 추가적인 연구를 위해 중요합니다.[164][165]

다낭성 난소의 초음파 소견은 증후군에 영향을 받지 않는 여성의 8-25%에서 발견됩니다.[166][167][168][169] 경구피임제 복용 여성의 14%가 다낭성 난소를 가지고 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[167] 난소 낭종은 또한 레보노르스트렐 방출 자궁 내 장치(IUD)의 일반적인 부작용입니다.[170]

PCOS를 가진 여성의 심장 대사 인자의 인종적 차이를 조사한 연구는 거의 없습니다.[171]

역사

이 질환은 1935년 미국의 산부인과 의사 어빙 F에 의해 처음 기술되었습니다. Stein, Sr. 그리고 Michael L. L. Leventhal은 Stein-Leventhal 증후군이라는 원래 이름에서 따왔습니다.[91][21] Stein과 Leventhal은 미국에서 PCOS를 내분비 장애로 처음 기술했고, 이후 여성들 사이에서 가장 흔한 과란성 불임의 원인 중 하나로 인식되고 있습니다.[50]

현재 PCOS로 인식되는 사람에 대한 최초의 출판된 설명은 1721년 이탈리아에서였습니다.[158] 난소에 대한 낭종 관련 변화는 1844년에 기술되었습니다.[158]

어원

이 증후군의 다른 이름으로는 다낭성 난소 증후군, 다낭성 난소 질환, 기능성 난소 과안드로겐증, 난소 비대증, 공막성 난소 증후군, 스타인-레벤탈 증후군 등이 있습니다. 마지막 선택지는 원래 이름이며, 현재는 불임, 다낭성 난소의 확대, 다낭성 난소를 가진 무월경의 모든 증상을 가진 여성의 하위 집합에만 사용됩니다.[91]

이 질병에 대한 가장 일반적인 이름은 다낭성 난소라고 불리는 의료 영상의 전형적인 발견에서 유래합니다. 다낭성 난소는 표면 근처에 비정상적으로 많은 수의 발달 중인 알을 가지고 있으며, 많은 작은 낭종처럼 보입니다.[91]

사회와 문화

2005년 미국에서 400만 건의 PCOS가 보고되었으며, 이로 인해 43억 6천만 달러의 의료 비용이 발생했습니다.[172] 2016년 국립연구원 보건연구원의 그 해 연구 예산 323억 달러 중 PCOS 연구에 0.1%가 지출되었습니다.[173] 14세에서 44세 사이의 사람들 중 PCOS의 비용은 보수적으로 연간 43억 7천만 달러에 이를 것으로 추정됩니다.[23]

일반 인구의 여성과 달리 PCOS를 가진 여성은 우울증과 불안의 비율이 더 높습니다. 국제 지침과 인도 지침은 PCOS를 가진 여성에게 우울증과 불안에 대한 검진뿐만 아니라 심리 사회적 요인을 고려해야 한다고 제안합니다.[174] 전 세계적으로 이러한 측면은 PCOS가 환자의 삶에 미치는 진정한 영향을 반영하기 때문에 점점 더 초점이 맞춰지고 있습니다. 연구에 따르면 PCOS는 환자의 삶의 질에 악영향을 미칩니다.[174]

공인

많은 유명인사들과 공인들이 PCOS에 대한 경험에 대해 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

- 빅토리아 베컴[175]

- 마키 북아웃[176]

- 프랭키 브리지[177]

- Harnaam Kaur[178]

- 하이메 킹[179]

- 크리스에뜨 미켈레[180]

- 레아 미켈레[181]

- 케케 파머[182]

- 사샤 피테르스[183][184]

- 데이지 리들리[185]

- Romee Strijd[186]

- 리 틸먼[187]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ Kollmann M, Martins WP, Raine-Fenning N (2014). "Terms and thresholds for the ultrasound evaluation of the ovaries in women with hyperandrogenic anovulation". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (3): 463–464. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu005. PMID 24516084.

- ^ Legro RS (2017). "Stein-Leventhal syndrome". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 January 2021.[더 나은 출처가 필요합니다.]

- ^ a b c "What are the symptoms of PCOS?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 29 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Condition Information". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. January 31, 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Is there a cure for PCOS?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 31 January 2017.

- ^ a b De Leo V, Musacchio MC, Cappelli V, Massaro MG, Morgante G, Petraglia F (July 2016). "Genetic, hormonal and metabolic aspects of PCOS: an update". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (Review). 14 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s12958-016-0173-x. PMC 4947298. PMID 27423183.

- ^ a b c d e Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kandarakis H, Legro RS (August 2006). "The role of genes and environment in the etiology of PCOS". Endocrine. 30 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1385/ENDO:30:1:19. PMID 17185788. S2CID 21220430.

- ^ a b c d "What causes PCOS?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 29 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "How do health care providers diagnose PCOS?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 29 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Mortada R, Williams T (August 2015). "Metabolic Syndrome: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". FP Essentials (Review). 435: 30–42. PMID 26280343.

- ^ a b Giallauria F, Palomba S, Vigorito C, Tafuri MG, Colao A, Lombardi G, Orio F (July 2009). "Androgens in polycystic ovary syndrome: the role of exercise and diet". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine (Review). 27 (4): 306–315. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1225258. PMID 19530064. S2CID 260321191.

- ^ a b c d National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2014-07-14). "Treatments to Relieve Symptoms of PCOS". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ a b Pal L, ed. (2013). "Diagnostic Criteria and Epidemiology of PCOS". Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Current and Emerging Concepts. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 7. ISBN 9781461483946. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- ^ Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E (November 2015). "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and androgen excess and PCOS society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome-part 1". Endocrine Practice. 21 (11): 1291–1300. doi:10.4158/EP15748.DSC. PMID 26509855.

- ^ a b Dunaif A, Fauser BC (November 2013). "Renaming PCOS--a two-state solution". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (11): 4325–4328. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2040. PMC 3816269. PMID 24009134.

Around 20% of European women have polycystic ovaries (the prevalence is even higher in some other populations) but approximately two-thirds of these women do not have PCOS

- ^ Khan MJ, Ullah A, Basit S. 다낭성 난소 증후군(PCOS)의 유전적 기초: 현재의 관점. Appl Clin Genet. 2019.12.24.12:249-260.doi: 10.2147/TACG.S200341. PMID: 31920361; PMCID: PMC6935309.

- ^ Crespo RP, Bachega TA, Mendonça BB, Gomes LG (June 2018). "An update of genetic basis of PCOS pathogenesis". Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 62 (3): 352–361. doi:10.20945/2359-3997000000049. PMC 10118782. PMID 29972435. S2CID 49681196.

- ^ Muscogiuri G, Altieri B, de Angelis C, Palomba S, Pivonello R, Colao A, Orio F (September 2017). "Shedding new light on female fertility: The role of vitamin D". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 18 (3): 273–283. doi:10.1007/s11154-017-9407-2. PMID 28102491. S2CID 33422072.

- ^ a b Lentscher JA, Slocum B, Torrealday S (March 2021). "Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Fertility". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 64 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000595. PMID 33337743. S2CID 229323594.

- ^ Wolf WM, Wattick RA, Kinkade ON, Olfert MD (November 2018). "Geographical Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as Determined by Region and Race/Ethnicity". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (11): 2589. doi:10.3390/ijerph15112589. PMC 6266413. PMID 30463276.

indigenous Australian women could have a prevalence as high as 26%

- ^ a b c d e f g h 다낭성 난소증후군, e-Medicine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L (June 2010). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan". BMC Medicine. 8 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-41. PMC 2909929. PMID 20591140.

- ^ a b Azziz R (March 2006). "Controversy in clinical endocrinology: diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome: the Rotterdam criteria are premature". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (3): 781–785. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2153. PMID 16418211.

- ^ a b Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group (January 2004). "Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)". Human Reproduction. 19 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh098. PMID 14688154.

- ^ Carmina E (February 2004). "Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: from NIH criteria to ESHRE-ASRM guidelines". Minerva Ginecologica. 56 (1): 1–6. PMID 14973405. NAID 10025610607.

- ^ Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S (October 2004). "Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 18 (5): 671–683. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.001. PMID 15380140.

- ^ a b "What We Talk About When We Talk About PCOS". www.vice.com. 23 January 2019. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2022-02-28. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ Cortet-Rudelli C, Dewailly D (Sep 21, 2006). "Diagnosis of Hyperandrogenism in Female Adolescents". Hyperandrogenism in Adolescent Girls. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ a b Huang A, Brennan K, Azziz R (April 2010). "Prevalence of hyperandrogenemia in the polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosed by the National Institutes of Health 1990 criteria". Fertility and Sterility. 93 (6): 1938–1941. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.138. PMC 2859983. PMID 19249030.

- ^ a b Nafiye Y, Sevtap K, Muammer D, Emre O, Senol K, Leyla M (April 2010). "The effect of serum and intrafollicular insulin resistance parameters and homocysteine levels of nonobese, nonhyperandrogenemic polycystic ovary syndrome patients on in vitro fertilization outcome". Fertility and Sterility. 93 (6): 1864–1869. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.024. PMID 19171332.

- ^ a b Pasquali, Renato (2018), "Lifestyle Interventions and Natural and Assisted Reproduction in Patients with PCOS", Infertility in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 169–180, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45534-1_13, ISBN 978-3-319-45533-4, retrieved 2023-08-22

- ^ a b Brutocao C, Zaiem F, Alsawas M, Morrow AS, Murad MH, Javed A (November 2018). "Psychiatric disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Endocrine. 62 (2): 318–325. doi:10.1007/s12020-018-1692-3. PMID 30066285. S2CID 51889051.

- ^ Devi, T (2018), "Lifestyle Modifications in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome", Decoding Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd., p. 195, doi:10.5005/jp/books/13089_17, ISBN 9789386322852, retrieved 2023-08-22

- ^ a b c d e f g Morrow-Baez, Kelly (2018). Thriving with PCOS: Lifestyle Strategies to Successfully Manage Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- ^ Rasquin, Lorena I.; Anastasopoulou, Catherine; Mayrin, Jane V. (2023). "Polycystic Ovarian Disease". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29083730.

- ^ Sam S (February 2015). "Adiposity and metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome". Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 21 (2): 107–116. doi:10.1515/hmbci-2015-0008. PMID 25781555. S2CID 23592351.

- ^ Corbould A (October 2008). "Effects of androgens on insulin action in women: is androgen excess a component of female metabolic syndrome?". Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 24 (7): 520–532. doi:10.1002/dmrr.872. PMID 18615851. S2CID 24630977.

- ^ Goyal M, Dawood AS (2017). "Debates Regarding Lean Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Narrative Review". Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 10 (3): 154–161. doi:10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_77_17. PMC 5672719. PMID 29142442.

- ^ Sachdeva G, Gainder S, Suri V, Sachdeva N, Chopra S (2019). "Obese and Non-obese Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Comparison of Clinical, Metabolic, Hormonal Parameters, and their Differential Response to Clomiphene". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 23 (2): 257–262. doi:10.4103/ijem.IJEM_637_18. PMC 6540884. PMID 31161114.

- ^ Johnstone E, Cannon-Albright L, Peterson CM, Allen-Brady K (July 2018). "Lean PCOS may be a genetically distinct from obese PCOS: lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome and their relatives have no increased risk of T2DM". Human Reproduction. Oxford, England: Oxford Univ Press. 33: 454. doi:10.26226/morressier.5af300b3738ab10027aa99cd. S2CID 242055977.

- ^ Goyal M, Dawood AS (2017). "Debates Regarding Lean Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Narrative Review". Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 10 (3): 154–161. doi:10.4103/jhrs.jhrs_77_17. PMC 5672719. PMID 29142442.

- ^ a b Roger Mazze; Ellie S. Strock; Gregg D. Simonson; Richard M. Bergenstal (11 January 2007). Staged Diabetes Management: A Systematic Approach (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-0-470-06171-8. OCLC 1039172275.

Diagnosis and treatment. The first diagnostic test [of PCOS] is measurement of total testosterone and free testosterone by radioimmunoassay. If total testosterone is between 50 ng/dL and 200 ng/dL above normal (<2.5 ng/dL) PCOS is present. If >200 ng/dL then serum DHEA-S should be measured. If total testosterone or DHEA-S >700 μg/dL then rule out an ovarian or adrenal tumor. These tests should be followed by tests for hypothyroidism, hyperprolactinemia, and adrenal hyperplasia.

- ^ a b Loh HH, Yee A, Loh HS, Kanagasundram S, Francis B, Lim LL (September 2020). "Sexual dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hormones (Athens). 19 (3): 413–423. doi:10.1007/s42000-020-00210-0. PMID 32462512. S2CID 218898082.

A total of 5366 women with PCOS from 21 studies were included. [...] Women with PCOS [...] [had higher] serum total testosterone level (2.34 ± 0.58 nmol/L vs 1.57 ± 0.60 nmol/L, p < 0.001) compared with women without PCOS. [...] PCOS is characterized by high levels of androgens (dehydroepiandrosterone, androstenedione, and testosterone) and luteinizing hormone (LH), and increased LH/follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio [52].

- ^ a b Balen AH, Conway GS, Kaltsas G, Techatrasak K, Manning PJ, West C, Jacobs HS (August 1995). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: the spectrum of the disorder in 1741 patients". Hum Reprod. 10 (8): 2107–11. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136243. PMID 8567849.

The criteria for the diagnosis of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have still not been agreed universally. A population of 1741 women with PCOS were studied, all of whom had polycystic ovaries seen by ultrasound scan. The frequency distributions of the serum concentrations of [...] testosterone [...] were determined and compared with the symptoms and signs of PCOS. [...] A rising serum concentration of testosterone [mean and 95th percentiles 2.6 (1.1-4.8) nmol/1] was associated with an increased risk of hirsutism, infertility and cycle disturbance. [...] If the serum testosterone concentration is >4.8 nmol/1, other causes of hyperandrogenism should be excluded.

- ^ Steinberger E, Ayala C, Hsi B, Smith KD, Rodriguez-Rigau LJ, Weidman ER, Reimondo GG (1998). "Utilization of commercial laboratory results in management of hyperandrogenism in women". Endocr Pract. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.4158/EP.4.1.1. PMID 15251757.

- ^ Legro RS, Schlaff WD, Diamond MP, Coutifaris C, Casson PR, Brzyski RG, Christman GM, Trussell JC, Krawetz SA, Snyder PJ, Ohl D, Carson SA, Steinkampf MP, Carr BR, McGovern PG, Cataldo NA, Gosman GG, Nestler JE, Myers ER, Santoro N, Eisenberg E, Zhang M, Zhang H (December 2010). "Total testosterone assays in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: precision and correlation with hirsutism". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 95 (12): 5305–13. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-1123. PMC 2999971. PMID 20826578.

Design and Setting: We conducted a blinded laboratory study including masked duplicate samples at three laboratories—two academic (University of Virginia, RIA; and Mayo Clinic, LC/MS) and one commercial (Quest, LC/MS). Participants and Interventions: Baseline testosterone levels from 596 women with PCOS who participated in a large, multicenter, randomized controlled infertility trial performed at academic health centers in the United States were run by varying assays, and results were compared. [...] The median testosterone level by RIA was 50 ng/dl (25th–75th percentile, 34–71 ng/dl); by LC/MS at Mayo, 47 ng/dl (25th–75th percentile, 34–65 ng/dl); and by LC/MS at Quest, 41 ng/dl (25th–75th percentile, 27–58 ng/dl) (Fig. 1). The minimum and maximum values detected by RIA were 8 and 189 ng/dl, respectively; by LC/MS at Mayo, 12 and 184 ng/dl, respectively; and by LC/MS at Quest, 1 and 205 ng/dl, respectively. [...] Our sample size was robust and the largest study to date examining quality control of total testosterone serum levels in women.

- ^ Carmina, Enrico; Stanczyk, Frank Z.; Lobo, Rogerio A. (2019). "Evaluation of Hormonal Status". In Strauss, Jerome F.; Barbieri, Robert L. (eds.). Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management (8 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 887–915.e4. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-47912-7.00034-2. ISBN 9780323479127. S2CID 56977185.

- ^ 사디아, Z. (2020, 8월) 다낭성 난소 증후군 (PCOS)에서 난포 자극 호르몬 (LH:FSH) 비율 - 비만 대 비비만 여성. 의료 기록 보관소 (Sarajevo, 보스니아 헤르체고비나). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7520057/

- ^ a b c Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ (1 September 2014). "Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 748–758. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu012. PMC 4326303. PMID 24688118.

- ^ New MI (May 1993). "Nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia and the polycystic ovarian syndrome". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 687 (1): 193–205. Bibcode:1993NYASA.687..193N. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43866.x. PMID 8323173. S2CID 30161989.

- ^ Hardiman P, Pillay OC, Atiomo W (May 2003). "Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial carcinoma". Lancet. 361 (9371): 1810–1812. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13409-5. PMID 12781553. S2CID 27453081.

- ^ Mather KJ, Kwan F, Corenblum B (January 2000). "Hyperinsulinemia in polycystic ovary syndrome correlates with increased cardiovascular risk independent of obesity". Fertility and Sterility. 73 (1): 150–156. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00468-9. PMID 10632431.

- ^ Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ (2010). "Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (4): 347–363. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq001. PMID 20159883.

- ^ Falcone T, Hurd RW (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-323-03309-1.

- ^ "Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Barry JA, Kuczmierczyk AR, Hardiman PJ (September 2011). "Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction. 26 (9): 2442–2451. doi:10.1093/humrep/der197. PMID 21725075.

- ^ Ovalle F, Azziz R (June 2002). "Insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus". Fertility and Sterility. 77 (6): 1095–1105. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03111-4. PMID 12057712.

- ^ de Groot PC, Dekkers OM, Romijn JA, Dieben SW, Helmerhorst FM (1 July 2011). "PCOS, coronary heart disease, stroke and the influence of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (4): 495–500. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr001. PMID 21335359.

- ^ Goldenberg N, Glueck C (February 2008). "Medical therapy in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome before and during pregnancy and lactation". Minerva Ginecologica. 60 (1): 63–75. PMID 18277353.

- ^ Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS (January 2008). "Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 26 (1): 72–84. doi:10.1055/s-2007-992927. PMID 18181085. S2CID 260316768.

- ^ "Iron Deficiency Injectables Market: Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2020-2025". imarc. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ^ a b 836페이지(섹션:다낭성 난소 증후군)의 경우:

- ^ a b c d Legro RS, Strauss JF (September 2002). "Molecular progress in infertility: polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertility and Sterility. 78 (3): 569–576. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03275-2. PMID 12215335.

- ^ Filippou P, Homburg R (July 2017). "Is foetal hyperexposure to androgens a cause of PCOS?". Human Reproduction Update. 23 (4): 421–432. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmx013. PMID 28531286.

- ^ Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, Marshall JC, Laven JS, Legro RS (October 2015). "Scientific Statement on the Diagnostic Criteria, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Molecular Genetics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". Endocrine Reviews (Review). 36 (5): 487–525. doi:10.1210/er.2015-1018. PMC 4591526. PMID 26426951.

- ^ a b Crosignani PG, Nicolosi AE (2001). "Polycystic ovarian disease: heritability and heterogeneity". Human Reproduction Update. 7 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.1.3. PMID 11212071.

- ^ a b c Strauss JF (November 2003). "Some new thoughts on the pathophysiology and genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 997 (1): 42–48. Bibcode:2003NYASA.997...42S. doi:10.1196/annals.1290.005. PMID 14644808. S2CID 23559461.

- ^ a b Hamosh A (12 September 2011). "POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME 1; PCOS1". OMIM. McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ Amato P, Simpson JL (October 2004). "The genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 18 (5): 707–718. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.002. PMID 15380142.

- ^ Draper N, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Tomlinson JW, Chalder SM, Arlt W, et al. (August 2003). "Mutations in the genes encoding 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase interact to cause cortisone reductase deficiency". Nature Genetics. 34 (4): 434–439. doi:10.1038/ng1214. PMID 12858176. S2CID 22772927.

- ^ Ehrmann DA (March 2005). "Polycystic ovary syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (12): 1223–1236. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041536. PMID 15788499. S2CID 79796961.

- ^ Faghfoori Z, Fazelian S, Shadnoush M, Goodarzi R (November 2017). "Nutritional management in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A review study". Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome (Review). 11 (Suppl 1): S429–S432. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2017.03.030. PMID 28416368.

- ^ Witchel, Selma Feldman; Oberfield, Sharon E; Peña, Alexia S (2019-06-14). "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Presentation, and Treatment With Emphasis on Adolescent Girls". Journal of the Endocrine Society. 3 (8): 1545–1573. doi:10.1210/js.2019-00078. ISSN 2472-1972. PMC 6676075. PMID 31384717.

- ^ Hoeger KM (May 2014). "Developmental origins and future fate in PCOS". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 32 (3): 157–158. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1371086. PMID 24715509. S2CID 32069697.

- ^ Abbott DH, Barnett DK, Bruns CM, Dumesic DA (2005). "Androgen excess fetal programming of female reproduction: a developmental aetiology for polycystic ovary syndrome?". Human Reproduction Update. 11 (4): 357–374. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi013. PMID 15941725.

- ^ Rasgon N (June 2004). "The relationship between polycystic ovary syndrome and antiepileptic drugs: a review of the evidence". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 24 (3): 322–334. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000125745.60149.c6. PMID 15118487. S2CID 24603227.

- ^ Rutkowska A, Rachoń D (April 2014). "Bisphenol A (BPA) and its potential role in the pathogenesis of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)". Gynecological Endocrinology. 30 (4): 260–265. doi:10.3109/09513590.2013.871517. PMID 24397396. S2CID 5828672.

- ^ a b Palioura E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E (December 2013). "Industrial endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 36 (11): 1105–1111. doi:10.1007/bf03346762. PMID 24445124. S2CID 27141519.

- ^ Hu X, Wang J, Dong W, Fang Q, Hu L, Liu C (November 2011). "A meta-analysis of polycystic ovary syndrome in women taking valproate for epilepsy". Epilepsy Research. 97 (1–2): 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.07.006. PMID 21820873. S2CID 26422134.

- ^ "Endocrine Disruptors". National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Merkin SS, Phy JL, Sites CK, Yang D (July 2016). "Environmental determinants of polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertility and Sterility. 106 (1): 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.05.011. PMID 27240194.

- ^ a b c d Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dunaif A (December 2012). "Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications". Endocrine Reviews. 33 (6): 981–1030. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1034. PMC 5393155. PMID 23065822.

- ^ Lewandowski KC, Cajdler-Łuba A, Salata I, Bieńkiewicz M, Lewiński A (2011). "The utility of the gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) test in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)". Endokrynologia Polska. 62 (2): 120–128. PMID 21528473. ProQuest 2464206947.

- ^ Rojas J, Chávez M, Olivar L, Rojas M, Morillo J, Mejías J, Calvo M, Bermúdez V (2014). "Polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity: navigating the pathophysiologic labyrinth". Int J Reprod Med. 2014: 71905. doi:10.1155/2014/719050. PMC 4334071. PMID 25763405.

- ^ Ali, Heba Ibrahim; Elsadawy, Momena Essam; Khater, Nivan Hany (2016-03-01). "Ultrasound assessment of polycystic ovaries: Ovarian volume and morphology; which is more accurate in making the diagnosis?!". The Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine. 47 (1): 347–350. doi:10.1016/j.ejrnm.2015.10.002. ISSN 0378-603X.

- ^ Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL (2010). "Mediators of inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome in relation to adiposity". Mediators of Inflammation. 2010: 758656. doi:10.1155/2010/758656. PMC 2852606. PMID 20396393.

- ^ Fukuoka M, Yasuda K, Fujiwara H, Kanzaki H, Mori T (November 1992). "Interactions between interferon gamma, tumour necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-1 in modulating progesterone and oestradiol production by human luteinized granulosa cells in culture". Human Reproduction. 7 (10): 1361–1364. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137574. PMID 1291559.

- ^ González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP (January 2006). "Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (1): 336–340. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1696. PMID 16249279.

- ^ Murri M, Luque-Ramírez M, Insenser M, Ojeda-Ojeda M, Escobar-Morreale HF (2013). "Circulating markers of oxidative stress and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (3): 268–288. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms059. PMID 23303572.

- ^ a b c d 다낭성 난소질환 e-Medicine에서의 영상화

- ^ Lujan, Marla E.; Chizen, Donna R.; Pierson, Roger A. (2008). "Diagnostic Criteria for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pitfalls and Controversies". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 30 (8): 671–679. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32915-2. ISSN 1701-2163. PMC 2893212. PMID 18786289.

- ^ a b c d e f 다낭성난소증후군~e메디신에서 워크업

- ^ Pedersen SD, Brar S, Faris P, Corenblum B (June 2007). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: validated questionnaire for use in diagnosis". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (6): 1042–7, 1041. PMC 1949220. PMID 17872783.

- ^ a b Dewailly D, Lujan ME, Carmina E, Cedars MI, Laven J, Norman RJ, Escobar-Morreale HF (2013). "Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: a task force report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (3): 334–352. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt061. PMID 24345633.

- ^ O'Brien WT (1 January 2011). Top 3 Differentials in Radiology. Thieme. p. 369. ISBN 978-1-60406-228-1. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

Ultrasound findings in PCOS include enlarged ovaries with peripheral follicles in a "string of pearls" configuration.

- ^ Bordewijk, Esmée M; Ng, Ka Ying Bonnie; Rakic, Lidija; Mol, Ben Willem J; Brown, Julie; Crawford, Tineke J; van Wely, Madelon (2020-02-11). "Laparoscopic ovarian drilling for ovulation induction in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (2): CD001122. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001122.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7013239. PMID 32048270.

- ^ Somani N, Harrison S, Bergfeld WF (2008). "The clinical evaluation of hirsutism". Dermatologic Therapy. 21 (5): 376–391. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00219.x. PMID 18844715. S2CID 34029116.

- ^ Sharquie KE, Al-Bayatti AA, Al-Ajeel AI, Al-Bahar AJ, Al-Nuaimy AA (July 2007). "Free testosterone, luteinizing hormone/follicle stimulating hormone ratio and pelvic sonography in relation to skin manifestations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome". Saudi Medical Journal. 28 (7): 1039–1043. OCLC 151296412. PMID 17603706. INIST 18933286.

- ^ a b Banaszewska B, Spaczyński RZ, Pelesz M, Pawelczyk L (2003). "Incidence of elevated LH/FSH ratio in polycystic ovary syndrome women with normo- and hyperinsulinemia". Roczniki Akademii Medycznej W Bialymstoku. 48: 131–134. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.410.676. PMID 14737959.

- ^ Macpherson G (2002). Black's Medical Dictionary (40 ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 496. ISBN 0810849844.

- ^ Dumont A, Robin G, Catteau-Jonard S, Dewailly D (December 2015). "Role of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a review". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (Review). 13: 137. doi:10.1186/s12958-015-0134-9. PMC 4687350. PMID 26691645.

- ^ Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, et al. (2014). "The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women". Human Reproduction Update (Review). 20 (3): 370–385. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt062. PMID 24430863.

- ^ Broer SL, Broekmans FJ, Laven JS, Fauser BC (2014). "Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 688–701. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu020. PMID 24821925.

- ^ Andersen, Marianne; Glintborg, Dorte (2018). "Diagnosis and follow-up of type 2 diabetes in women with PCOS: a role for OGTT?". European Journal of Endocrinology. 179 (3): D1–D14. doi:10.1530/EJE-18-0237. ISSN 1479-683X. PMID 29921567. S2CID 49315075.

- ^ Muniyappa, Ranganath; Madan, Ritu; Varghese, Ron T. (2000), Feingold, Kenneth R.; Anawalt, Bradley; Boyce, Alison; Chrousos, George (eds.), "Assessing Insulin Sensitivity and Resistance in Humans", Endotext, South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc., PMID 25905189, retrieved 2022-10-19

- ^ a b c Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. 2022. doi:10.1016/c2018-0-03276-4. ISBN 9780128230459. S2CID 222263507.

- ^ a b National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2014-07-14). "Treatments for Infertility Resulting from PCOS". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ a b Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, Hoeger KM, Murad MH, Pasquali R, Welt CK (December 2013). "Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (12): 4565–4592. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2350. PMC 5399492. PMID 24151290.

- ^ Magkos, Faidon; Yannakoulia, Mary; Chan, Jean L.; Mantzoros, Christos S. (2009). "Management of the Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes Through Lifestyle Modification". Annual Review of Nutrition. 29: 223–256. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141200. ISSN 0199-9885. PMC 5653262. PMID 19400751.

- ^ Veltman-Verhulst SM, Boivin J, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BJ (2012). "Emotional distress is a common risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studies". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (6): 638–651. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms029. PMID 22824735.

- ^ Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, et al. (Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines) (July 2016). "American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity". Endocrine Practice. 22 (Suppl 3): 1–203. doi:10.4158/EP161365.GL. PMID 27219496.

- ^ a b Moran LJ, Ko H, Misso M, Marsh K, Noakes M, Talbot M, et al. (2013). "Dietary composition in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review to inform evidence-based guidelines". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (5): 432. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt015. PMID 23727939.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 다낭성 난소증후군~eMedicine 치료

- ^ Krul-Poel YH, Snackey C, Louwers Y, Lips P, Lambalk CB, Laven JS, Simsek S (December 2013). "The role of vitamin D in metabolic disturbances in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". European Journal of Endocrinology (Review). 169 (6): 853–865. doi:10.1530/EJE-13-0617. PMID 24044903.

- ^ He C, Lin Z, Robb SW, Ezeamama AE (2015). "Serum Vitamin D Levels and Polycystic Ovary syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 7 (6): 4555–4577. doi:10.3390/nu7064555. PMC 4488802. PMID 26061015.

- ^ Huang G, Coviello A (December 2012). "Clinical update on screening, diagnosis and management of metabolic disorders and cardiovascular risk factors associated with polycystic ovary syndrome". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 19 (6): 512–519. doi:10.1097/med.0b013e32835a000e. PMID 23108199. S2CID 205792902.

- ^ Alesi, Simon; Forslund, Maria; Melin, Johanna; Romualdi, Daniela; Peña, Alexia; Tay, Chau Thien; Witchel, Selma Feldman; Teede, Helena; Mousa, Aya (September 2023). "Efficacy and safety of anti-androgens in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". eClinicalMedicine. 63: 102162. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102162. PMC 10424142. PMID 37583655.

- ^ Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ (October 2003). "Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 327 (7421): 951–953. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7421.951. PMC 259161. PMID 14576245.

- ^ Li XJ, Yu YX, Liu CQ, Zhang W, Zhang HJ, Yan B, et al. (March 2011). "Metformin vs thiazolidinediones for treatment of clinical, hormonal and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis". Clinical Endocrinology. 74 (3): 332–339. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03917.x. PMID 21050251. S2CID 19620846.

- ^ Grover A, Yialamas MA (March 2011). "Metformin or thiazolidinedione therapy in PCOS?". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 7 (3): 128–129. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.16. PMID 21283123. S2CID 26162421. Gale A250471047.

- ^ 국립보건임상우수연구소. 11 임상지침 11 : 출산력: 출산력 문제가 있는 사람에 대한 평가 및 치료. 런던, 2004.

- ^ Balen A (December 2008). "Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome" (PDF). Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 13. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-18. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ Leeman L, Acharya U (August 2009). "The use of metformin in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome and associated anovulatory infertility: the current evidence". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 29 (6): 467–472. doi:10.1080/01443610902829414. PMID 19697191. S2CID 3339588.

- ^ NICE (December 2018). "Metformin Hydrochloride". National Institute for Care Excellence. NICE. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ Feig DS, Moses RG (October 2011). "Metformin therapy during pregnancy: good for the goose and good for the gosling too?". Diabetes Care. 34 (10): 2329–2330. doi:10.2337/dc11-1153. PMC 3177745. PMID 21949224.

- ^ Cassina M, Donà M, Di Gianantonio E, Litta P, Clementi M (1 September 2014). "First-trimester exposure to metformin and risk of birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 656–669. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu022. PMID 24861556.

- ^ Wang FF, Wu Y, Zhu YH, Ding T, Batterham RL, Qu F, Hardiman PJ (October 2018). "Pharmacologic therapy to induce weight loss in women who have obesity/overweight with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis" (PDF). Obesity Reviews. 19 (10): 1424–1445. doi:10.1111/obr.12720. PMID 30066361. S2CID 51891552.

- ^ Sharpe A, Morley LC, Tang T, Norman RJ, Balen AH (December 2019). "Metformin for ovulation induction (excluding gonadotrophins) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD013505. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013505. PMC 6915832. PMID 31845767.

- ^ "Erase the Dread and Stigma of PCOD". Matria. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ Balen AH, Morley LC, Misso M, Franks S, Legro RS, Wijeyaratne CN, et al. (November 2016). "The management of anovulatory infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an analysis of the evidence to support the development of global WHO guidance". Human Reproduction Update. 22 (6): 687–708. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmw025. PMID 27511809.

- ^ Qiao J, Feng HL (2010). "Extra- and intra-ovarian factors in polycystic ovary syndrome: impact on oocyte maturation and embryo developmental competence". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq032. PMC 3001338. PMID 20639519.

- ^ "What are some causes of female infertility?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. 31 January 2017.

- ^ Jurczewska, Justyna; Szostak-Węgierek, Dorota (2022-04-08). "The Influence of Diet on Ovulation Disorders in Women—A Narrative Review". Nutrients. 14 (8): 1556. doi:10.3390/nu14081556. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 9029579. PMID 35458118.

- ^ Franik, Sebastian; Le, Quang-Khoi; Kremer, Jan Am; Kiesel, Ludwig; Farquhar, Cindy (2022-09-27). "Aromatase inhibitors (letrozole) for ovulation induction in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (9): CD010287. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010287.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 9514207. PMID 36165742.

- ^ Tanbo T, Mellembakken J, Bjercke S, Ring E, Åbyholm T, Fedorcsak P (October 2018). "Ovulation induction in polycystic ovary syndrome". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 97 (10): 1162–1167. doi:10.1111/aogs.13395. PMID 29889977.

- ^ Hu S, Yu Q, Wang Y, Wang M, Xia W, Zhu C (May 2018). "Letrozole versus clomiphene citrate in polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 297 (5): 1081–1088. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4688-6. PMID 29392438. S2CID 4800270.

- ^ Penzias, Alan; Bendikson, Kristin; Butts, Samantha; Coutifaris, Christos; Falcone, Tommaso; Fossum, Gregory; Gitlin, Susan; Gracia, Clarisa; Hansen, Karl; La Barbera, Andrew; Mersereau, Jennifer; Odem, Randall; Paulson, Richard; Pfeifer, Samantha; Pisarska, Margareta; Rebar, Robert; Reindollar, Richard; Rosen, Mitchell; Sandlow, Jay; Vernon, Michael (September 2017). "Role of metformin for ovulation induction in infertile patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a guideline". Fertility and Sterility. 108 (3): 426–441. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.026. PMID 28865539.

- ^ Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, Carr BR, Diamond MP, Carson SA, et al. (February 2007). "Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (6): 551–566. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa063971. PMID 17287476.[1차가 아닌 소스가 필요합니다.]

- ^ Homburg, Roy (2004). "Management of infertility and prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 18 (5): 773–788. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.05.006. ISSN 1521-6934. PMID 15380146.

- ^ Ghanem, Mohamad E.; Elboghdady, Laila A.; Hassan, Mohamad; Helal, Adel S.; Gibreel, Ahmed; Houssen, Maha; Shaker, Mohamed E.; Bahlol, Ibrahiem; Mesbah, Yaser (2013). "Clomiphene Citrate co-treatment with low dose urinary FSH versus urinary FSH for clomiphene resistant PCOS: randomized controlled trial". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 30 (11): 1477–1485. doi:10.1007/s10815-013-0090-2. ISSN 1058-0468. PMC 3879942. PMID 24014214.

- ^ Zhuang J, Wang X, Xu L, Wu T, Kang D (May 2013). "Antidepressants for polycystic ovary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (5): CD008575. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008575.pub2. PMC 7390273. PMID 23728677.

- ^ Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou C, Palioura E, Kandaraki E, Livadas S (June 2008). "Does polycystic ovary syndrome start in childhood?". Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews. 5 (4): 904–911. PMID 18552753.

- ^ Fraison E, Kostova E, Moran LJ, Bilal S, Ee CC, Venetis C, Costello MF (August 2020). "Metformin versus the combined oral contraceptive pill for hirsutism, acne, and menstrual pattern in polycystic ovary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD005552. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005552.pub3. PMC 7437400. PMID 32794179.

- ^ "Polycystic ovary syndrome – Treatment". United Kingdom: National Health Service. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ a b 다낭성 난소증후군~eMedicine에서의 약물치료

- ^ van Zuuren, Esther J; Fedorowicz, Zbys; Carter, Ben; Pandis, Nikolaos (2015-04-28). "Interventions for hirsutism (excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD010334. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010334.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6481758. PMID 25918921.

- ^ "Irregular periods - NHS". Nhs.uk. 2020-10-21. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- ^ "What are the health risks of PCOS?". Verity – PCOS Charity. Verity. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Pundir J, Psaroudakis D, Savnur P, Bhide P, Sabatini L, Teede H, et al. (February 2018). "Inositol treatment of anovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomised trials" (PDF). BJOG. 125 (3): 299–308. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14754. PMID 28544572. S2CID 21090113.

- ^ Amoah-Arko A, Evans M, Rees A (20 October 2017). "Effects of myoinositol and D-chiro inositol on hyperandrogenism and ovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". Endocrine Abstracts. doi:10.1530/endoabs.50.P363.

- ^ Unfer V, Carlomagno G, Dante G, Facchinetti F (July 2012). "Effects of myo-inositol in women with PCOS: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Gynecological Endocrinology. 28 (7): 509–515. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.650660. PMID 22296306. S2CID 24582338.

- ^ Zeng L, Yang K (January 2018). "Effectiveness of myoinositol for polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Endocrine. 59 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1007/s12020-017-1442-y. PMID 29052180. S2CID 4376339.

- ^ Laganà AS, Vitagliano A, Noventa M, Ambrosini G, D'Anna R (October 2018). "Myo-inositol supplementation reduces the amount of gonadotropins and length of ovarian stimulation in women undergoing IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 298 (4): 675–684. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4861-y. PMID 30078122. S2CID 51921158.

- ^ Galazis N, Galazi M, Atiomo W (April 2011). "D-Chiro-inositol and its significance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". Gynecological Endocrinology. 27 (4): 256–262. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.538099. PMID 21142777. S2CID 1989262.

- ^ Lim CE, Ng RW, Cheng NC, Zhang GS, Chen H (July 2019). "Acupuncture for polycystic ovarian syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD007689. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007689.pub4. PMC 6603768. PMID 31264709.

- ^ Wu XK, Stener-Victorin E, Kuang HY, Ma HL, Gao JS, Xie LZ, et al. (June 2017). "Effect of Acupuncture and Clomiphene in Chinese Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 317 (24): 2502–2514. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7217. PMC 5815063. PMID 28655015.

- ^ a b c Kovacs GT, Norman R (2007-02-22). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9781139462037. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–2196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ^ McLuskie I, Newth A (January 2017). "New diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome". BMJ. 356: i6456. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6456. hdl:10044/1/44217. PMID 28082338. S2CID 13042313.

- ^ Pruthi B (26 September 2019). "One in five Indian women suffers from PCOS". The Hindu. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Ladson G, Dodson WC, Sweet SD, Archibong AE, Kunselman AR, Demers LM, et al. (July 2011). "Racial influence on the polycystic ovary syndrome phenotype: a black and white case-control study". Fertility and Sterility. 96 (1): 224–229.e2. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.002. PMC 3132396. PMID 21723443.

- ^ Hillman JK, Johnson LN, Limaye M, Feldman RA, Sammel M, Dokras A (September 2013). "Black women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have increased risk for metabolic syndrome (MET SYN) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to white women with PCOS". Fertility and Sterility. 100 (3): S100–S101. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.1707. ISSN 0015-0282.

- ^ Elghobashy, Mirna; Lau, Gar Mun; Davitadze, Meri; Gillett, Caroline D. T.; O’Reilly, Michael W.; Arlt, Wiebke; Kempegowda, Punith; Lindenmeyer, Antje (2023). "Concerns and expectations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome vary across age and ethnicity: findings from PCOS Pearls Study". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 14. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1175548. ISSN 1664-2392.

- ^ "Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (2023)". www.asrm.org. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ Polson DW, Adams J, Wadsworth J, Franks S (April 1988). "Polycystic ovaries--a common finding in normal women". Lancet. 1 (8590): 870–872. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91612-1. PMID 2895373. S2CID 41297081.

- ^ a b Clayton RN, Ogden V, Hodgkinson J, Worswick L, Rodin DA, Dyer S, Meade TW (August 1992). "How common are polycystic ovaries in normal women and what is their significance for the fertility of the population?". Clinical Endocrinology. 37 (2): 127–134. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02296.x. PMID 1395063. S2CID 12384062.

- ^ Farquhar CM, Birdsall M, Manning P, Mitchell JM, France JT (February 1994). "The prevalence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound scanning in a population of randomly selected women". The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 34 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1994.tb01041.x. PMID 8053879. S2CID 312422.

- ^ van Santbrink EJ, Hop WC, Fauser BC (March 1997). "Classification of normogonadotropic infertility: polycystic ovaries diagnosed by ultrasound versus endocrine characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertility and Sterility. 67 (3): 452–458. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)80068-4. PMID 9091329.

- ^ Hardeman J, Weiss BD (March 2014). "Intrauterine devices: an update". American Family Physician. 89 (6): 445–450. PMID 24695563.

- ^ Chahal, Nikhita; Quinn, Molly; Jaswa, Eleni A.; Kao, Chia-Ning; Cedars, Marcelle I.; Huddleston, Heather G. (2020-09-25). "Comparison of metabolic syndrome elements in White and Asian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: results of a regional, American cross-sectional study". F&S Reports. 1 (3): 305–313. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.09.008. ISSN 2666-3341. PMC 8244318. PMID 34223261.

- ^ Azziz R, Marin C, Hoq L, Badamgarav E, Song P (August 2005). "Health care-related economic burden of the polycystic ovary syndrome during the reproductive life span". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 90 (8): 4650–4658. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0628. PMID 15944216.

- ^ "RCDC Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC)". NIH. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ a b Chaudhari AP, Mazumdar K, Mehta PD (2018). "Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 40 (3): 239–246. doi:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_561_17. PMC 5968645. PMID 29875531.

- ^ "Sarah Hall investigates polycystic ovary syndrome". The Guardian. 2002-02-28. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Migdol, Erin. "'Teen Mom' Star Nails the 'Lose-Lose' Side of Chronic Illness Doctors Don't Always Get". The Mighty. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- ^ "All the celebrities who've opened up about life with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". Cosmopolitan. 26 November 2021. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ Chowdhury J. "What Every Woman Should Know About PCOS". www.refinery29.com. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "Actress Jaime King on her investment in Allara, a chronic care platform for women". Fortune. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ "Chrisette Michele Opens Up About Living With PCOS & No Longer Being Vegan - BlackDoctor.org - Where Wellness & Culture Connect". BlackDoctor.org. 2015-12-10. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ^ "Lea Michele On How PCOS Changed Her Relationship With Food: 'The Side Effects Can Be Brutal'". Health Magazine. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ Natale N (2021-11-17). "Keke Palmer Says PCOS Causes Facial Hair and Adult Acne". Prevention. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Seemayer Z (September 26, 2017). "Sasha Pieterse Tears Up Over Health Problems, Opens Up About Losing 15 Pounds Since Joining 'DWTS'". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Mizoguchi K, Stern AB (October 5, 2017). "Sasha Pieterse Wows on People's Ones to Watch Red Carpet as She Reveals Why She's 'So Thankful to DWTS'". people.com. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ "'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' Actress Opens Up About Painful Disorder". ABC News. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "Romee Strijd's Pregnancy Announcement Comes With an Honest Message About Reproductive Health". Vogue. 29 May 2020. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ Silman, Anna (March 10, 2020). "Lee's American Dream". The Cut. New York Media. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

더보기

- Bremer AA (October 2010). "Polycystic ovary syndrome in the pediatric population". Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. 8 (5): 375–394. doi:10.1089/met.2010.0039. PMC 3125559. PMID 20939704.

- "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 31 January 2017.

외부 링크

위키미디어 커먼즈의 다낭성 난소증후군 관련 미디어

위키미디어 커먼즈의 다낭성 난소증후군 관련 미디어