맨해튼 파이낸셜 디스트릭트

Financial District, Manhattan금융 지구 | |

|---|---|

![The Financial District of Lower Manhattan, including Wall Street, the world’s principal financial center.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/85/Manhattan_in_the_distance_%28Unsplash%29.jpg/400px-Manhattan_in_the_distance_%28Unsplash%29.jpg) | |

뉴욕시 소재지 | |

| 좌표:40°42°27°N 74°00′33″w/40.70750°N 74.00917°W좌표: 40°42°27°N 74°00°33°W / 40.70750°N 74.00917°W / | |

| 나라 | |

| 주 | |

| 도시 | 뉴욕 시 |

| 자치구 | 맨해튼 |

| 커뮤니티 구역 | 맨해튼 1[2] |

| 지역 | |

| • 합계 | 1.17km2(0.453평방마일) |

| 인구. (2011년)[3] | |

| • 합계 | 57,627 |

| • 밀도 | 49,000/km2(130,000/140mi) |

| 경제학 | |

| • 중간 소득 | $125,565 |

| 시간대 | UTC-5(동부) |

| 우편 번호 | 10004, 10005, 10006, 10007, 10038 |

| 지역번호 | 212, 332, 646 및 917 |

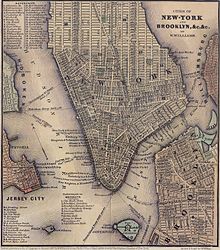

파이낸셜 [4]디스트릭트 오브 로어 맨해튼은 뉴욕 맨해튼 섬의 남쪽 끝에 위치한 동네이다.서쪽은 웨스트 사이드 고속도로, 북쪽은 챔버스 스트리트와 시청 공원, 북동쪽은 브루클린 브리지, 남동쪽은 이스트 리버, 남쪽은 사우스 페리와 배터리와 경계를 이루고 있습니다.

뉴욕시는 1624년에 금융 지구에 만들어졌고, 그 주변은 [5]17세기 후반 뉴 암스테르담 정착지의 경계와 대략적으로 겹친다.이 지역은 뉴욕 증권거래소와 뉴욕 연방준비은행을 포함한 많은 주요 금융 기관의 사무실과 본사로 구성되어 있습니다.금융지구의 월스트리트에 정박해 있는 뉴욕은 세계에서 [6][7][8][9][10]가장 재정적인 도시이자 금융의 중심지로 불리며, 뉴욕 증권거래소는 [11][12]시가총액 기준으로 세계 최대의 증권거래소이다.뉴욕상품거래소, 나스닥, 뉴욕상품거래소, 구 미국증권거래소 등 금융지구에 본사가 있거나 본사가 있는 주요 거래소가 여럿 있다.

Financial District는 Manhattan Community District 1의 일부이며 주요 ZIP 코드는 10004, 10005, 10006, 10007 및 10038입니다.[2]뉴욕시 경찰국 제1지구에서 순찰하고 있습니다.

묘사

파이낸셜 디스트릭트는 Lower Manhattan의 시청 공원 남쪽 지역을 대략 포함하지만 배터리 파크와 배터리 파크 시티는 제외됩니다.2001년 9월 11일 테러가 일어나기 전까지 이 근처에 있었던 옛 세계무역센터에는 그 후신인 원 월드 트레이드 센터가 있다.파이낸셜 디스트리의 중심은 종종 월 스트리트와 브로드 스트리트의 코너로 간주되며, 둘 다 이 [13]지역 내에 완전히 포함되어 있습니다.Financial District의 북동부(Fulton Street 및 John Street와 함께)는 20세기 초에 보험 지구로 알려졌습니다. 왜냐하면 그곳에 본사를 두거나 뉴욕 지사를 유지한 보험 회사 수가 많았기 때문입니다.

이 용어는 월스트리트의 동의어로 사용되기도 하지만, 후자는 종종 금융 시장 전체(및 지역의 거리이기도 함)에 대해 동의어로 사용된다. 반면, "금융 지구"는 실제 지리적 위치를 의미한다.파이낸셜 디스트릭트는 맨해튼 커뮤니티 보드 1의 일부이며, 5개의 다른 지역(배터리 파크 시티, 시빅 센터, 그리니치 사우스, 시포트, 트리베카)[2]도 포함되어 있습니다.

스트리트 그리드

이 지역의 거리는 1811년 커미셔너스 플랜 이전에 카스텔로 계획의 일부로 배치되었으며, 휴스턴 스트리트 북쪽 맨해튼 거리의 배치를 결정하는 그리드 플랜이다.따라서, "숨막히는 인공 협곡"[14]을 만드는 한 묘사에 따르면, 그곳은 "한 차선의 차량들이 양쪽으로 가장 높은 건물들과 경계를 이룰 만큼 거의 넓지 않다"고 한다.일부 도로는 보행자 전용으로 지정되고 차량 통행이 [15]금지되어 있다.

관광업

파이낸셜 디스트릭트는 뉴욕시의 주요 관광지입니다.한 보도는 로어 맨해튼을 "카메라를 들고 다니는 관광객들과 싸운다"[16]고 묘사했다.여행 가이드들은 트리니티 처치, 뉴욕 연방준비은행 빌딩 금고, 뉴욕 증권거래소 [17]빌딩과 같은 장소를 강조한다.월 스트리트 투어의 악당들은 박물관 방문과 "금융법이나 금융 허점을 뚫는 방법을 찾는데 능숙한"[18] 다양한 금융가들의 토론을 포함한 걸어 다니는 역사적인 투어이다.때때로 예술가들은 즉석 공연을 한다; 예를 들어, 2010년에 22명의 댄서들로 구성된 극단이 빌리 [19]도너가 안무한 "도시 공간의 신체에 있는 금융 지구의 구석과 구석으로 몸을 담그고 밀어 넣는다".주요 명소 중 하나인 연방준비제도이사회는 1997년 방문객 갤러리를 열기 위해 75만 달러를 지불했다.뉴욕증권거래소와 미국증권거래소도 1990년대 후반에 방문객들을 위한 시설을 업그레이드하기 위해 돈을 썼다.미국 연방준비제도이사회(FRB) 지하의 금고와 자유의 여신상에 가는 것만큼이나 거래 층에서 눈을 떼지 않는 것도 매력이다.[16]

아키텍처

금융가의 건축은 일반적으로 길드 시대에 뿌리를 두고 있지만, 이웃에 아트 데코 영향도 있다.이 지역은 좁은 도로와 가파른 지형으로 구분되며, 이러한[14] 좁은 급경사 지역의 고층 건설로 인해 크레인 [20]붕괴와 같은 사고가 종종 발생하고 있다.한 보고서는 맨해튼 하부를 세 개의 기본 [14]구역으로 구분했습니다.

- 파이낸셜 디스트릭트(특히 존 스트리트)가 적절한 곳

- World Trade Center 지역 남쪽—그리니치, 워싱턴 및 웨스트 스트리트를 따라 World Trade Center 남쪽으로 몇 블록 떨어진 곳

- 수백 [14]년 된 저층 건물과 사우스 스트리트 시포트로 특징지어지는 시포트 구역은 한 가지 설명에 따르면 "조용하고 주거적이며 오래된 세계의 매력이 있다"고 합니다.

미국 최초의 국회의사당이자 초대 대통령으로서 조지 워싱턴의 첫 취임식 장소인 연방관 국립기념관은 월 스트리트와 나사우 스트리트의 모퉁이에 위치해 있다.

금융 지구에는 사우스 스트리트 시포트 역사 지구, 새롭게 개조된 17번 부두, 뉴욕 시 경찰 박물관, 미국 금융 박물관, 미국 인디언 박물관, 트리니티 교회, 세인트 폴 예배당, 그리고 유명한 황소와 같은 많은 관광 명소가 있습니다.볼링 그린은 브로드웨이에서 열리는 전통적인 티커테이프 퍼레이드의 시작점이며, 이곳은 영웅의 협곡으로도 알려져 있다.유대인 유산 박물관과 초고층 빌딩 박물관은 모두 인접한 배터리 파크 시티에 있으며, 또한 브룩필드 플레이스(구 세계 금융 센터)의 본거지이기도 합니다.

이 지역의 또 다른 주요 앵커는 뉴욕 증권거래소이다.시 당국은 그것의 중요성을 깨닫고 "월가와 브로드가의 모퉁이에 있는 신고전주의 사원이 더 이상 성장하지 않았다"고 믿었고, 1998년에 금융 [21]지구에 그것을 유지하기 위해 상당한 세금 혜택을 제공했다.2001년 9월 11일 테러로 인해 [21]재건 계획이 지연되었다.Exchange는 아직 같은 사이트를 점유하고 있다.Exchange는 대량의 테크놀로지와 데이터의 중심입니다.예를 들어, Exchange 층에서 직접 일하는 3,000명의 사람들을 수용하려면 3,500 킬로와트의 전기와 거래 층에만 8,000개의 전화 회선이 필요하며 [22]지하 200마일의 광섬유 케이블이 필요합니다.

공식 랜드마크

금융 지구의 빌딩은 다음과 같은 몇 가지 유형의 공식 랜드마크 명칭 중 하나를 가질 수 있습니다.

- 뉴욕시 랜드마크 보존 위원회는 뉴욕시의 역사적 구역의 랜드마크와 건물을 식별하고 지정하는 책임을 지는 뉴욕시 기관이다.뉴욕시의 랜드마크(NYCL)는 개별([23]외부), 내부 및 경치 랜드마크로 분류할 수 있습니다.

- National Regist of Historic Places(NRHP)는 미국 연방정부가 역사적 [24]중요성을 고려하여 보존할 가치가 있다고 간주하는 구역, 부지, 건물, 구조물 및 물건의 공식 목록입니다.

- National Historical Landmark(NHL)는 미국 역사, 건축, 엔지니어링 또는 문화에서 중요한 장소에 초점을 맞추고 있으며, 모든 NHL 사이트도 NRHP에 [25]있습니다.

다음 랜드마크는 Morris Street 남쪽과 Whitehall Street/Broadway 서쪽입니다.[26]

- 웨스트 스트리트 21번지(NRHP,[27] NYCL

- Alexander Hamilton 미국 커스텀 하우스, Bowling Green(NHL, NRHP, NYCL, NYCL 인테리어)[28]

- 볼링 그린 펜스(NYCL)[29]

- 볼링 그린(NRHP)[30]

- 볼링 그린 오피스 빌딩, 브로드웨이 11번지(NYCL)[31]

- Castle Clinton, 배터리 (NRHP, NYCL)[32]

- 시티 피어 A, 배터리(NRHP, NYCL)[33]

- Cunard Building, 25 Broadway (NYCL, NYCL 내부)[34]

- 다운타운 애슬레틱 클럽, 웨스트 스트리트 19번지(NYCL)[35]

- Interborough Rapid Transit System, 배터리 파크 컨트롤 하우스(NRHP,[36] NYCL)

- 브로드웨이 1번지 국제상업해양회사 빌딩(NRHP, NYCL)[37]

- James Watson House, 7 State Street (NRHP, NYCL)[38]

- 화이트홀 빌딩, 17 Battery Place (NYCL)[39]

브로드웨이 서쪽의 Morris Streets와 Barclay [26]Streets 사이에는 다음과 같은 랜드마크가 있습니다.

- 미국 증권거래소 빌딩(NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[40]

- 65 브로드웨이 (NYCL)[41]

- 90 웨스트 스트리트 (NRHP, 뉴욕주)[42]

- 94 그리니치 스트리트 (NYCL)[43]

- 195 브로드웨이(NYCL, NYCL 내부)[44]

- 브로드웨이 71번지 엠파이어 빌딩(NRHP, NYCL)[45]

- 뉴욕 카운티 변호사 협회 빌딩, Vesey Street 14(NRHP, NYCL)[46]

- Vesey Street 20번지 올드 뉴욕 이브닝 포스트 빌딩(NRHP, NYCL)[47]

- Robert & Anne Dickkey House, 67 그리니치 스트리트(NYCL)[48]

- 세인트조지 시리아 가톨릭 교회, 워싱턴 스트리트 103번지(NYCL)[49]

- Fulton Street 브로드웨이 세인트 폴 채플(NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[50]

- 바클레이 스트리트 22번지(NRHP, NYCL)[51] 성 베드로 로마 가톨릭 교회

- Trinity and United States Realty Buildings, Broadway 111-115 (둘 다 뉴욕시)[52]

- Trinity Church, Broadway at Wall Street(NRHP, NYCL)[53]

- Verizon Building, West Street 140(NRHP, NYCL, NYCL 내부)[54]

다음 랜드마크는 월 스트리트 남쪽과 브로드웨이/화이트홀 스트리트 [26]동쪽에 있습니다.

- 1 하노버 스퀘어(NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[55]

- 월가(NYCL)×[56]1

- 월스트리트 코트 1개(NRHP, 뉴욕주)[57]

- 1 윌리엄 스트리트 (NYCL)[58]

- 20 교환 장소(NYCL)[59]

- 23 월가(NRHP, 뉴욕주)[60]

- 26 브로드웨이 (NYCL)[61]

- 월가 55번지(NRHP, NYCL, NYCL 내부)[62]

- 브로드 스트리트 70번지(NRHP, NYCL)[63] 미국 지폐 회사 건물

- Battery Maritine Building, South Street(NRHP, NYCL)[64]

- 브로드 스트리트 25번지 브로드 익스체인지 빌딩(NRHP, 뉴욕주)[65]

- 비버 스트리트 56번지(NYCL)[66] 델모니코 빌딩

- 제1경찰서, 구전표 100장(NRHP, NYCL)[67]

- 프라운스 선술집, 펄 스트리트 54번지(NRHP, NYCL)[68]

- Broad Street 8-18번지 뉴욕 증권거래소 빌딩(NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[69]

- 월 스트리트 59-63번지 월 앤 하노버 빌딩(NRHP)[70]

브로드웨이 동쪽에는 월가와 메이든 레인 사이에 다음과 [26]같은 랜드마크가 있습니다.

- 14 월가(NYCL)[71]

- 리버티 스트리트 28번지 (NYCL)[72]

- 월가 40번지 (NRHP, 뉴욕주)[73]

- 월가 48번지(NRHP,[74] NYCL

- 파인 스트리트 56번지(NRHP, NYCL)[75]

- 파인 스트리트 70번지(NYCL, NYCL 내부)[76]

- 90~94 메이든 레인(NYCL)[77]

- 브로드웨이 100번지(NYCL)[78] 아메리칸 슈어티 빌딩

- 리버티 스트리트 65번지 상공회의소 빌딩(NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[79]

- 파인 스트리트 60번지 다운타운 어소시에이션 빌딩(NYCL)[80]

- Equitable Building (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[81]

- 월가 26번지 연방홀 국립기념관(NHL, NRHP, NYCL, NYCL 내부)[82]

- 뉴욕 연방준비은행 리버티 스트리트 33번지 빌딩(NRHP, NYCL)[83]

- 리버티 스트리트 55번지 리버티 타워(NRHP, NYCL)[84]

- 마린 미들랜드 빌딩, 140 브로드웨이(NYCL)[85]

메이든 레인(Maiden Lane)과 브루클린 다리([26]Brooklyn Bridge) 사이에 있는 브로드웨이와 파크 로우(Park Row)의 동쪽에는 다음과 같은 랜드마크가 있습니다.

- 5 Beekman Street (NYCL)[86]

- Nassau Street 63 (NYCL)[87]

- 150 Nassau Street (NYCL)[88]

- 베넷 빌딩, Nassau Street 99(NYCL)[89]

- Corbin Building, John Street 13번지([90]NRHP, NYCL)

- Excelsior Power Company 빌딩, 33-43 골드 스트리트(NYCL)[91]

- 존 스트리트 감리교회, 존 스트리트 44번지(NRHP, NYCL)[92]

- Fulton Street(NYCL)[93] 127번지 Keuffel & Esser Company 빌딩

- 모스 빌딩, 나소 스트리트 138-42 (NYCL)[94]

- 뉴욕타임스빌딩, 파크로 41(NYCL)[95]

- 파크열 빌딩, 15 파크열(NRHP, NYCL)[96]

- 포터 빌딩, 38 파크 로우(NYCL)[97]

다음 랜드마크는 여러 개별 [26]영역에 적용됩니다.

- 프라운스 선술집 블록 역사 지구(NRHP, NYCL)[98]

- South Street Seport Historic District(NRHP, NYCL; 다수의 개별 [99]랜드마크 포함)

- 뉴암스테르담과 식민지 뉴욕 거리 계획(NYCL)[100]

- 스톤 스트리트 역사 지구(NYCL)[101]

- 월 스트리트, 풀턴 스트리트 역 내부(NYCL)[102]

역사

뉴암스테르담

지금의 금융 지구는 한때 맨해튼 섬의 전략적인 남쪽 끝에 위치한 뉴 암스테르담의 일부였다.뉴암스테르담은 포트암스테르담에서 유래한 것으로, 북강(허드슨 강)에 있는 네덜란드 서인도 회사의 모피 무역 사업을 방어하기 위한 것이었다.1624년 네덜란드 공화국의 지방 연장선이 되었고 1625년 [103]뉴네덜란드 주의 수도로 지정되었다.1655년까지 뉴네덜란드의 인구는 2,000명으로 증가했고 1,500명이 뉴암스테르담에 살았다.1664년까지, 뉴네덜란드의 인구는 거의 9,000명으로 치솟았고, 그 중 2,500명은 뉴암스테르담에, 1,000명은 포트 오렌지 근처에, 나머지는 다른 마을과 [104][105]마을에 살았다.1664년에 영국인들은 뉴암스테르담을 점령하고 뉴욕시로 [106]이름을 바꿨다.

19세기와 20세기

19세기 후반과 20세기 초반, 뉴욕의 기업 문화는 초기 초고층 빌딩 건설의 주요 중심지였고, 미국 대륙에서 오직 시카고와 견줄 수 있었다.브로드웨이와 허드슨 강 사이, 그리고 베시 스트리트와 배터리 사이 등 주거 구역도 있었다.볼링 그린 지역은 가난한 사람들, 높은 유아 사망률,[107] 그리고 "이 도시에서 가장 열악한 주거 환경"이 있는 "월스트리트의 뒷마당"으로 묘사되었다.건설의 결과, 뉴욕시를 동쪽에서 바라보면, 두 개의 뚜렷한 건물 덩어리가 보입니다. 왼쪽은 파이낸셜 디스트릭트, 오른쪽은 더 높은 미드타운 인근입니다.맨하탄의 지질은 맨하탄 지하에 단단한 암반 덩어리가 높은 빌딩의 견고한 토대를 제공하면서 높은 빌딩에 적합하다.초고층 빌딩은 건설하는 데 비용이 많이 들지만, 금융 지구의 토지가 부족하기 때문에 초고층 [108]빌딩 건설에 적합했다.

비즈니스 작가 존 브룩스는 저서 '원스 인 골콘다'에서 20세기 초를 이 지역의 [109]전성기라고 여겼다.The Corner로 알려진 J. P. Morgan & Company의 본사인 23 Wall Street의 주소는 "미국의 금융계와 심지어 [109]금융계의 정확한 중심"이었다.

1920년 9월 16일, 금융 지구의 가장 번화한 모퉁이이자 모건 은행의 사무실 건너편인 월가와 브로드 가의 모퉁이 근처에서 강력한 폭탄이 폭발했다.이로 인해 38명이 사망하고 143명이 [110]중상을 입었다.이 지역은 수많은 위협에 시달렸다; 1921년 한 번의 폭탄 위협으로 형사들은 "월가의 폭탄 [111]폭발의 재발을 막기 위해" 그 지역을 봉쇄했다.

20세기 후반의 성장

20세기의 대부분 동안, 금융 지구는 사실상 밤에 비워지는 사무실만 있는 비즈니스 커뮤니티였다.1961년 뉴욕타임스의 한 보도는 "5시 30분 이후 그리고 토요일과 일요일 하루 종일 그 지역에 자리잡는 죽음과 같은 고요함"[14]을 묘사했다.그러나 기술 변화와 시장 상황의 변화에 따라 이 지역의 주거 이용이 확대되는 방향으로 변화가 일어나고 있다.일반적인 패턴은 수십만 명의 근로자들이 낮에 그 지역으로 출퇴근하는 것이며, 때로는 도시의 다른 지역뿐만 아니라 뉴저지나 롱아일랜드에서 택시를[112] 나눠 타고 밤에 출발하는 것이다.1970년에는 833명만이 "체임버스 스트리트 남쪽"에 살았고, 1990년에는 13,782명이 거주했으며, 배터리[21] 파크 시티와 사우스 브리지 [113]타워스 같은 지역이 추가되었다.Battery Park City는 92에이커의 매립지에 건설되었고, 1982년부터 3,000명의 사람들이 그곳으로 이주하였다. 그러나 1986년에는 더 많은 상점과 상점, 공원이 있다는 증거와 더불어 더 많은 주택 [114]개발 계획이 있었다.

1966년에 세계무역센터가 건설되기 시작했지만, 세계무역센터는 완공되었을 때 세입자를 유치하는 데 어려움을 겪었다.그럼에도 불구하고, 몇몇 실질적인 회사들은 그곳에서 공간을 구입했다.그것의 인상적인 높이는 운전자와 보행자를 위한 시각적 랜드마크로 만드는데 도움을 주었다.금융지구의 연결고리가 월가에서 세계무역센터 단지로 물리적으로 이동하면서 도이체방크 빌딩, 90웨스트 스트리트, One Liberty Plaza 등 주변 빌딩으로 옮겨간 측면도이체방크 빌딩, 90웨스트 스트리트, One Liberty Plaza 등 다양한 측면에서 볼 수 있다.1990년대 후반의 부동산 성장은 현저했습니다.금융지구와 맨해튼의 다른 곳에서 거래와 새로운 프로젝트가 이루어졌습니다.한 회사는 월스트리트에 [115]240억 달러 이상을 다양한 프로젝트에 투자했습니다.1998년 뉴욕증권거래소와 뉴욕시는 9억 달러의 거래를 체결하여 뉴욕증권거래소가 강을 건너 저지시티로 이동하는 것을 막았다. 이 거래는 "시 역사상 기업이 마을을 떠나는 것을 막는 가장 큰 거래"[116]로 묘사되었다.NYSE의 경쟁사인 나스닥은 본사를 워싱턴에서 [117]뉴욕으로 옮겼다.

1987년 주식시장은[118] 폭락했고 그에 이은 비교적 짧은 불황으로 맨해튼은 10만 개의 일자리를 잃었다고 한 추정치가 [113]있다.통신비가 낮아짐에 따라 은행과 중개업체는 금융지구에서 좀 더 저렴한 [113]곳으로 이전할 수 있었습니다.1990-91년의 불경기는 "지속적으로 높은" 도심 사무실 공실률과 일부 건물들이 "비어있는"[14] 것으로 나타났다.

주택가

1995년, 시 당국은 상업용 부동산을 주거용으로 [14]전환하기 위한 인센티브를 제공하는 Lower Manhattan Revivation Plan을 제안했다.1996년 한 묘사에 따르면, "이 지역은 밤에 죽는다...이웃과 [113]공동체가 필요합니다."지난 20년 동안, 일부 사례에서 [21]시 당국의 인센티브와 함께, 금융 지구의 더 큰 주거 거주 지역으로의 이동이 있었다.많은 빈 사무실 건물들이 다락방과 아파트로 개조되었다. 예를 들어,[113] 석유 재벌 해리 싱클레어의 사무실 건물인 리버티 타워는 1979년에 협동조합으로 전환되었다.1996년에는 건물과 창고의 5분의 1이 비어 있었고,[113] 많은 건물들이 생활권으로 전환되었다.일부 개조 작업은 기존 [113]건축 법규를 충족하기 위해 건물 외관의 노후된 고가일을 비싸게 복원해야 하는 등의 문제에 직면했습니다.이 지역 주민들은 슈퍼마켓, 영화관, 약국, 더 많은 학교, 그리고 "좋은 식당"[113]을 갖기를 원했다.잡 로트라는 이름의 할인 소매점은 세계무역센터에 있었지만 처치 스트리트로 옮겨갔다. 상인들은 추가적인 미분양 품목을 가파른 가격에 구입하여 소비자들에게 할인 판매했다. 그리고 쇼핑객들은 "시청 직원들과 월스트리트의 간부들과 친하게 지내는" 알뜰 주부들과 브라우징 은퇴자들을 포함했다.rm은 [119]1993년에 파산했다.

1990년대에 약 2만5000명으로 60% 증가했다는 보고가 있었지만, 2000년의 2차 추정치(2000년의 다른 지도에 근거한 인구 조사)에서는 12,042명이었다.2001년까지 몇몇 식료품점, 세탁소, 그리고 두 개의 초등학교와 한 개의 상위 [21]고등학교가 있었다.

21세기

9/11 공격

2001년 뉴욕증권거래소(NYSE)라고 불리는 빅보드는 "세계에서 가장 크고 권위 있는 주식 시장"[120]으로 묘사되었다.2001년 9월 11일 세계무역센터가 파괴되었을 때, 1970년대 이후 새로운 발전이 이 복합단지를 미적으로 밀어내면서 건축적 공허를 남겼다.그 공격은 통신 [120]네트워크를 붕괴시켰다.한 가지 추정치는 이 동네에서 가장 좋은 사무실 공간의 45%[118]가 사라졌다는 것이다.물리적 파괴는 엄청났다.

잔해가 금융가의 몇몇 거리에 널려 있었다.위장복을 입은 주방위군 대원들이 검문소를 지켰다.세계무역센터 붕괴로 인한 먼지로 뒤덮인 버려진 커피카트가 인도를 가로질러 옆으로 쓰러져 있었다.대부분의 지하철역은 문을 닫았고, 대부분의 전등은 여전히 꺼져 있었고, 대부분의 전화는 작동하지 않았고, 소수의 사람들만이 어제 아침 월스트리트의 좁은 협곡을 걸었다.

--

그러나 뉴욕증권거래소는 공격 [22]일주일 만인 9월 17일 재개장하기로 결정했다.9월 11일 이후 금융 서비스 산업은 연말 보너스가 65억 달러라는 상당한 감소와 함께 침체기를 거쳤다.[119]

이 지역의 차량 폭격을 막기 위해 당국은 콘크리트 장벽을 쌓았고, 볼라드에 각각 5천 달러에서 8천 달러를 지출함으로써 시간이 지남에 따라 콘크리트 방벽을 더욱 매력적으로 만들 방법을 찾아냈다.월 스트리트와 브로드 스트릿을 포함한 인근 지역의 몇몇 거리는 특별히 설계된 볼라드로 봉쇄되었다.

로저스 마블은 넓고 비스듬한 표면이 사람들에게 앉을 장소를 제공하는 새로운 종류의 볼라드를 디자인했는데, 볼라드는 절대 무시할 수 없는 전형적인 볼라드와는 대조적이다.노고라고 불리는 이 볼라드는 프랭크 게리의 비정통 문화 궁전 중 하나처럼 보이지만 주변 환경에 무감각한 것은 아니다.그것의 청동 표면은 실제로 월스트리트의 상업 사원들의 웅장한 출입구를 메아리친다.역사적인 트리니티 교회 주변 지역에서 월스트리트로 진입할 때 보행자들은 그들 무리 사이를 쉽게 빠져나갑니다.하지만 자동차는 지나갈 수 없다.

--

재개발

세계무역센터의 파괴는 수십 [108]년 동안 볼 수 없었던 규모의 발전을 촉진시켰다.연방정부, 주정부 및 지방정부가 제공하는 세금 혜택은 발전을 촉진했다.대니얼 리베스킨드 메모리 재단을 중심으로 한 새로운 세계무역센터 단지는 9.11 테러 이후였다.현재 1776피트(541m) 높이의 이 센터피스는 2014년 원월드 트레이드 [121]센터로 문을 열었다.이 지역에 대한 접근성을 개선하기 위한 새로운 교통 단지인 풀튼 센터는 [122]2014년에 문을 열었고,[123][124] 세계 무역 센터 교통 허브는 2016년에 문을 열었다.또, 2007년에는 뉴욕 마하리시 글로벌 파이낸셜 캐피털이 뉴욕증권거래소 인근 브로드 스트리트 70번지에 본사를 설립해 [125]투자자를 모집하고 있다.

2010년대에는 금융지구가 주상복합도시로 자리잡았다.125 그리니치 스트리트와 130 윌리엄과 같은 몇 개의 새로운 고층 빌딩이 개발되었고, 1 월 스트리트, 에퀴터블 빌딩, 울워스 빌딩과 같은 다른 구조물들은 광범위하게 [126]개조되었다.게다가, 근무 시간 동안 군중들의 일반적인 패턴과 밤에는 비어있음에도 불구하고, 밤에는 개 산책객들의 징후가 더 많았고 24시간 동네가 있었다.2010년에는 [14]10개의 호텔과 13개의 박물관이 있었다.2007년 프랑스 패션 소매업체 에르메스는 파이낸셜 디스트릭트에 4700달러짜리 가죽 드레지 안장 또는 47,000달러짜리 한정판 악어 [15]서류가방과 같은 상품을 판매하기 위해 매장을 열었다.그러나 도시의 [127]다른 곳과 같은 거지가 있다는 보고가 있다.2010년까지 거주 인구는 [128]24,400명으로 증가했으며 고급 아파트와 고급 [129]소매상들로 인해 이 지역은 성장하고 있다.

2012년 10월 29일, 뉴욕과 뉴저지는 허리케인 샌디에 의해 침수되었다.지역 최고 기록인 14피트 높이의 폭풍 해일은 로어 맨해튼의 많은 지역에서 대규모 도로 홍수를 일으켰다.콘 에디슨 공장의 변압기 폭발로 이 지역에 전기가 나갔다.뉴욕시의 대중 교통은 폭풍이 닥치기 전에 이미 예방 조치로 정지된 가운데, 뉴욕 증권거래소와 다른 금융 거래소는 10월 31일 재개장하면서 [130]이틀간 문을 닫았다.2013년부터 2021년까지, 금융 지구의 거의 200개의 건물이 주거용으로 전환되었다.게다가 2001년부터 2021년 사이에 금융과 보험업에 종사하는 기업의 비율은 55%[131]에서 30%로 감소했다.

인구 통계

뉴욕시 정부는 인구 조사를 위해 파이낸셜 디스트릭트를 배터리 파크 시티-로어 [132]맨하탄이라고 불리는 더 큰 근린 집계 지역의 일부로 분류합니다.2010년 미국 인구 조사 자료에 따르면 배터리 파크 시티-로어 맨해튼의 인구는 39,699명으로 2000년의 20,088명보다 19,611명(97.6%) 증가했다.479.77에이커(194.16ha)의 면적을 차지하는 이 지역의 인구 밀도는 82.7/에이커(52,900/sq mi; 20,400/km2)[133]였다.이 지역의 인종 구성은 백인 65.4%(2만5965명), 흑인 3.2%(1288명), 원주민 0.1%, 아시아 20.2%(8,016명), 태평양 섬 주민 0.0%(17명), 기타 인종 0.4%(153명), 기타 인종 2.01%(2,170명)였다.어떤 인종이든 히스패닉 또는 라틴계는 인구의 [134]7.7% (3,055명)였다.

금융지구와 기타 맨해튼 로어 지역을 구성하는 커뮤니티 1지구 전체는 뉴욕 건강의 2018년 커뮤니티 헬스 프로파일 기준으로 63,383명의 주민이 살고 있으며 평균 수명은 85.[135]: 2, 20 8세이다.이는 뉴욕시 모든 [136]: 53 (PDF p. 84) [137]지역의 평균 수명인 81.2세보다 높은 것이다.대부분의 거주자는 젊은 층에서 중년층 성인으로 절반(50%)이 25~44세 사이이며, 14%는 0~17세, 18%는 45~64세 사이이다.대학생과 노인 거주자의 비율은 각각 11%[135]: 2 와 7%로 낮았다.

2017년 현재, 지역구 1과 2(그리니치 빌리지와 소호 포함)의 중앙 가계 소득은 144,878달러였지만, 금융 지구의 중앙 소득은 125,[138][3]565달러였다.2018년에는 금융 지구 및 맨해튼 하부 거주자의 약 9%가 빈곤한 생활을 하고 있었는데, 이에 비해 맨해튼 전체는 14%, 뉴욕 전체는 20%가 빈곤한편,맨해튼의 7%와 뉴욕시의 9%에 비해 거주자 25명 중 1명(4%)은 실업자였다.임대료 부담(임대료 지불에 어려움을 겪는 거주자의 비율)은 파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼의 38%이며, 자치구 전체와 시 전체 요율은 각각 45%와 51%입니다.이 계산에 따르면 2018년 현재[update] 파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼은 도시의 나머지 지역에 비해 고소득으로 간주되며 고급화가 이루어지지 [135]: 7 않고 있다.

금융구의 인구는 2014년 43,000명에서 2018년 [139]현재 약 61,000명으로 증가하여 2000년 인구 조사 때의 [140]23,000명보다 거의 두 배 가까이 증가했다.

정치적 대표성

현지의

뉴욕 시의회에서 금융 지구는 민주당 마가렛 [141][142]친으로 대표되는 1구역의 일부입니다.

금융가를 대표하는 시의원/의원 목록

- 1922년-1930년: 마틴 F. 타나헤이, 민주당

- 1938년~1947년: 자치구 전체 비례대표

- 1965-1974: 사울 샤리슨

- 1974년~1977년: 앤서니 가에타, 민주당

- 1977년~1985년: 니콜라스 라포르테, 민주당

- 1985년 : 프랭크 포셀라, 민주당

- 1986~1990년: 수전 몰리나리, 공화당원

- 1990~1991년: 알프레드 C. 세룰로 3세, 공화당

- 1991-2001: 캐스린 E. 자유, 민주

- 2002 ~ 2010 : Alan Gerson, 민주당

- 2010 ~ 현재 : Margaret Chin, 민주당

주

Financial District는 민주당의 Brian [145]P. Kavanagh로 대표되는 26대 주 상원 [143][144]선거구의 일부입니다.뉴욕주 의회에서 북서쪽 끝은 민주당 데보라 글릭이 [145][146][147]대표한 66번 지역구에 속하지만, 대부분의 지역은 민주당 Yuh-Line Niou로 대표되는 65번 지역구에 속합니다.

연방정부

2013년 현재[update],[148][149] 금융 지구는 미국 하원의 두 개의 의회 지역구 내에 위치하고 있다.이 지역의 대부분은 민주당의 제롤드 내들러 의원이 대표로 있는 뉴욕 제10의회 선거구의 일부이며, 북동쪽 끝은 민주당의 캐롤린 [145]말로니 의원이 대표로 있는 뉴욕 제12의회 선거구의 일부입니다.

경찰과 범죄

Financial District와 Lower Manhattan은 16 Ericsson [150]Place에 위치한 NYPD 제1지구에서 순찰하고 있습니다.제1경찰서는 2010년 1인당 범죄로 69개 순찰지역 중 63위를 차지했다.다른 뉴욕 경찰서에 비해 범죄 건수는 적지만 거주 인구도 훨씬 [151]적다.2018년 현재[update] 인구 10만명당 24명의 비치명적 폭행률로 금융지구와 로어맨하탄의 1인당 강력범죄 발생률은 도시 전체보다 낮다.인구 10만 명당 152명의 수감률은 도시 [135]: 8 전체보다 낮다.

1경찰서는 1990년대보다 범죄율이 낮아져 1990년부터 2018년까지 모든 범주의 범죄가 86.3% 감소했다.경찰청은 2018년 [152]한 해 동안 살인 1건, 강간 23건, 강도 80건, 중범죄 61건, 절도 85건, 중절도 1085건, 자동차 21건을 신고했다.

화재 안전

파이낸셜 디스트릭트는,[153] 다음의 3개의 뉴욕시 소방서(FDNY)에 의해서 운영되고 있습니다.

- 엔진 컴퍼니 4 / 래더 컴퍼니 15 / 디콘 유닛 – 사우스[154] 스트리트 42

- 엔진 컴퍼니 6 – Beekman[155] Street 49

- 엔진 컴퍼니 10/래더 컴퍼니 10 – 리버티[156] 스트리트 124

헬스

2018년 현재[update], 10대 엄마들의 조기 출산과 출산은 도시 전체의 다른 곳보다 금융 구역과 로어 맨해튼에서 덜 흔하다.Financial District와 Lower Manhattan에서는 1,000명당 77명(도시 전체 1,000명당 87명 대비), 1,000명당 2.2명(도시 전체 1,000명당 19.3명 대비)의 조산아 수가 있었지만, 10대 출산율은 작은 표본 [135]: 11 크기에 기초하고 있다.파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼은 보험에 가입하지 않은 거주자의 인구가 적다.2018년, 이 비보험 거주자 인구는 시 전체의 12%보다 적은 4%로 추정되었지만, 이는 표본 크기가 [135]: 14 작았다.

파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼의 대기오염 물질 중 가장 치명적인 유형인 미세 입자 물질의 농도는 0.0096mg/m3(9.6×10oz−9/cuft)로 도시 [135]: 9 평균보다 높다.파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼 거주자의 16%가 흡연자이며,[135]: 13 이는 시 거주자의 평균인 14%보다 많은 수치입니다.Financial District와 Lower Manhattan에서는 거주자의 4%가 비만, 3%가 당뇨병, 15%가 고혈압으로 도시 전체의 평균인 [135]: 16 24%, 11%, 28%에 비해 도시에서 가장 낮은 비율을 보이고 있습니다.또한 어린이의 5%가 비만이며, 이는 도시 전체의 평균인 [135]: 12 20%에 비해 도시에서 가장 낮은 비율이다.

주민의 96%가 매일 과일과 야채를 먹고 있는데, 이는 시의 평균인 87%보다 많은 것이다.2018년에는 주민의 88%가 자신의 건강을 "좋다", "매우 좋다" 또는 "우수하다"라고 표현했는데, 이는 시의 평균인 78%[135]: 13 보다 많은 수치입니다.Financial District와 Lower Manhattan의 슈퍼마켓마다 6개의 보데가스가 [135]: 10 있습니다.

가장 가까운 주요 병원은 시빅 센터 [157][158]지역에 있는 뉴욕 프레스비터리안 로어 맨해튼 병원입니다.

우체국과 우편번호

파이낸셜 디스트릭트는 여러 ZIP 코드 내에 있습니다.가장 큰 ZIP 코드는 배터리 중심인 10004번, 월가 중심인 10005번, 월드 트레이드 센터 주변인 10006번, 시청 주변인 10007번, 사우스 스트리트 시포트 주변인 10038번입니다.또한 연방준비은행 주변 10045번, 에퀴터블 빌딩 주변 10271번, 울워스 [159]빌딩 주변 10279번 등 하나의 블록에 걸쳐 있는 여러 개의 작은 ZIP 코드가 있습니다.

미국 우체국은 금융 지구에 4개의 우체국을 운영하고 있습니다.

교육

파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼은 일반적으로 2018년 현재 다른[update] 도시보다 대학 교육을 받은 거주자의 비율이 높다.25세 이상(84%)이 대부분이며, 고졸 이하가 4%, 고졸 이하가 12%다.반면 맨해튼 거주자의 64%와 도시 거주자의 43%는 대학 이상의 [135]: 6 교육을 받고 있다.2000년 61%였던 Financial District 및 Lower Manhattan 학생의 수학 우수율은 2011년 80%로 상승했고, 같은 [164]기간 읽기 성취도는 66%에서 68%로 증가했다.

파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 로어 맨해튼의 초등학생 결석률은 뉴욕시의 다른 지역보다 낮다.Financial District와 Lower Manhattan에서는 초등학생의 6%가 1년에 20일 이상 결석했습니다.이는 도시 전체의 평균인 20%[135]: 6 [136]: 24 (PDF p. 55) 보다 적은 수치입니다.또한 파이낸셜 디스트릭트와 Lower Manhattan의 고교생 중 96%가 정시에 졸업합니다.이는 도시 전체의 평균인 75%[135]: 6 보다 높은 수치입니다.

학교

뉴욕시 교육청은 금융 [165]지구에서 다음과 같은 공립 학교를 운영하고 있습니다.

- 도시의회 청년여성경영대학원(9~[166]12학년)

- 스프루스 스트리트 스쿨(그레이드 PK-8)[167]

- 밀레니엄 고등학교(9~[168]12학년)

- 리더십 및 공공서비스 고등학교(9~[169]12학년)

- 맨해튼 예술 및 언어 아카데미(9~[170]12학년)

- 경제금융고등학교(9~[171]12학년)

라이브러리

뉴욕 공공 도서관(NYPL)은 근처에 두 개의 분관을 운영하고 있습니다.뉴암스테르담 지점은 브로드웨이 근처 머레이 스트리트 9번지에 위치해 있습니다.1989년 [172]오피스 빌딩 1층에 설립되었습니다.Battery Park City 지점은 Murray Street 근처의 North End Avenue 175에 있습니다.2010년에 완공된 이 2층 지점은 NYPL의 첫 LEED 인증 [173]지점입니다.

교통.

파이낸셜 디스트릭트에 [174]위치한 뉴욕 시영 지하철역은 다음과 같습니다.

- 볼링 그린, 월 스트리트 (4열차 및 5열차)

- Broad Street (J 및 Z 열차)

- 챔버스 -WTC-Park Place-Cortlandt Street (2, 3, A, C 및E 열차)

- 시청, 렉터 스트리트(N, R, W 열차)

- Fulton Street (A 및 C 열차)

- WTC Cortlandt 렉터 스트리트 (1, 2, 3열차)

- 사우스페리/화이트홀 스트리트(1, N, R, W열차)

가장 큰 교통 허브인 Fulton Center는 2001년 9월 11일까지 14억 달러의 재건 프로젝트가 필요한 후 2014년에 완공되었으며, 적어도 5개의 다른 플랫폼 세트가 포함되어 있습니다.이 교통 허브는 2014년 [175]말 현재 하루 30만 명의 승객을 수용할 것으로 예상되었습니다.World Trade Center Transportation Hub와 PATH 역은 [176]2016년에 문을 열었다.

또한 MTA 지역 버스 운영은 금융 지구에서 여러 버스 노선, 즉 M15, M15 SBS, M20, M55 및 M103 노선이 지역을 통해 남북으로 운행되고 M9 및 M22 노선이 지역을 통해 서북동쪽으로 운행됩니다.금융가를 [177]달리는 MTA 고속버스 노선도 많다.Lower Manhattan Development Corporation은 2003년에 [178]무료 셔틀버스인 Downtown Connection을 운영하기 시작했습니다. 이 노선은 [179]낮 동안 금융 지구를 순환합니다.

화이트홀 [180]터미널의 Staten Island 페리, Pier 11/Wall Street의 NYC 페리 및 Battery Park City 페리 터미널,[181] Battery Maritary [182]Building의 Governers Island 서비스도 시내 중심가에 집중되어 있습니다.

가장 높은 빌딩

| 이름. | 이미지 | 높이 피트(m) | 플로어 | 연도 | 메모들 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 원 월드 트레이드 센터 |  | 1,776 (541.3) | 104 | 2014 | 2013년 5월 10일에 완공된 이후 세계에서 7번째로 높고 미국에서 가장 높은 빌딩입니다.그것은 또한 서반구에서 가장 높은 건물이며 세계에서 [183][184]가장 높은 올 오피스 빌딩이다. |

| 3 세계 무역 센터 |  | 1,079 (329) | 80 | 2018 | 혼용,[185] 2018년에 오픈. |

| 4 세계 무역 센터 |  | 978 (298) | 74 | 2013 | 재건된 세계무역센터와 금융지구에서 세 번째로 높은 건물입니다.그 건물은 2013년에 [186]세입자들에게 개방되었다. |

| 파인 스트리트 70번지 |  | 952 (290) | 66 | 1932 | 미국에서 22번째로 높은 빌딩; 이전의 American International Building and Citys Service[187][188] Building 70 Pine은 644개의 임대 주택, 132개의 호텔 방, 35,000 평방 피트의 소매점을[189] 가진 주거용 초고층 빌딩으로 탈바꿈하고 있다. |

| 30 파크 플레이스 |  | 937 (286) | 82 | 2016 | 포시즌스 프라이빗 레지던스와 호텔.2015년에 보충하여 [190]2016년에 완성. |

| 40 월 스트리트 |  | 927 (283) | 70 | 1930 | 미국에서 26번째로 높다; 1930년에 두 달 미만에 세계에서 가장 높은 빌딩; 이전에는 Bank of Manhattan Trust Building; 40 Wall[191][192] Street로도 알려져 있었다. |

| 리버티 스트리트 28번지 |  | 813 (248) | 60 | 1961 | [193][194] |

| 웨스트 스트리트 50번지 |  | 778 (237) | 63 | 2016 | [195][196] |

| 웨스트 스트리트 200 |  | 749 (228) | 44 | 2010 | Goldman Sachs[197][198] World Headquarters라고도 합니다. |

| 월가 60번지 |  | 745 (227) | 55 | 1989 | 도이치 뱅크[199][200] 빌딩이라고도 합니다. |

| 원 리버티 플라자 |  | 743 (226) | 54 | 1973 | 이전에는 미국 스틸[201][202] 빌딩으로 알려져 있었습니다. |

| 20 교환 장소 |  | 741 (226) | 57 | 1931 | 시티은행-농민신탁빌딩으로[203][204] 알려짐 |

| 200 베시 스트리트 |  | 739 (225) | 51 | 1986 | Three World Financial[205][206] Center라고도 합니다. |

| HSBC 은행 빌딩 |  | 688 (210) | 52 | 1967 | 마린 미들랜드[207][208] 빌딩이라고도 합니다. |

| 워터 스트리트 55 |  | 687 (209) | 53 | 1972 | [209][210] |

| 1 월 스트리트 |  | 654 (199) | 50 | 1931 | 뱅크 오브 뉴욕 멜론[211][212] 빌딩이라고도 합니다. |

| 리버티 스트리트 225 |  | 645 (197) | 44 | 1987 | Two World Financial[213][214] Center라고도 합니다. |

| 1 뉴욕 플라자 |  | 640 (195) | 50 | 1969 | [215][216] |

| 홈 인슈어런스 플라자 |  | 630 (192) | 45 | 1966 | [217][218] |

갤러리

월가 23번지에 있는 옛 모건 가문 건물

리버티 플라자(One Liberty Plaza)는 이 지역의 많은 현대식 고층 건물 중 하나이다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Jones, Huw (March 24, 2022). "New York widens lead over London in top finance centres index". www.reuters.com. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c "NYC Planning Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Wall Street/Financial District neighborhood in New York". Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Couzzo, Steve (April 25, 2007). "FiDi Soaring High". New York Post. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

The Financial District is over. So is the "Wall Street area." But say hello to FiDi, the coinage of major downtown landlord Kent Swig, who decided it's time to humanize the old F.D. with an easily remembered, fun-sounding acronym.

- ^ "Manhattan, New York – Some of the Most Expensive Real Estate in the World Overlooks Central Park". The Pinnacle List. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ Richard Florida (March 3, 2015). "Sorry, London: New York Is the World's Most Economically Powerful City". Bloomberg.com. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

Our new ranking puts the Big Apple firmly on top.

- ^ "Top 8 Cities by GDP: China vs. The U.S." Business Insider, Inc. July 31, 2011. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

For instance, Shanghai, the largest Chinese city with the highest economic production, and a fast-growing global financial hub, is far from matching or surpassing New York, the largest city in the U.S. and the economic and financial super center of the world.

"PAL sets introductory fares to New York". Philippine Airlines. Retrieved March 25, 2015. - ^ John Glover (November 23, 2014). "New York Boosts Lead on London as Leading Finance Center". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "UBS may move US investment bank to NYC". e-Eighteen.com Ltd. June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "GFCI 31 Rank - Long Finance". www.longfinance.net. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ "2013 WFE Market Highlights" (PDF). World Federation of Exchanges. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "NYSE Listings Directory". Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Aaron Donovan (September 9, 2001). "If You're Thinking of Living In/The Financial District; In Wall Street's Canyons, Cliff Dwellers". The New York Times: Real Estate. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Claire Wilson (July 29, 2007). "Hermès Tempts the Men of Wall Street". The New York Times: Real Estate. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b David M. Halbfinger (August 27, 1997). "New York's Financial District Is a Must-See Tourist Destination". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ LIsa W. Foderaro (June 20, 1997). "A Financial District Tour". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ T.L. Chancellor (January 14, 2010). "Walking Tours of NYC". USA Today: Travel. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Aaron Rutkoff (September 27, 2010). "'Bodies in Urban Spaces': Fitting In on Wall Street". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Sarah Wheaton and Ravi Somaiya (March 27, 2010). "Crane Falls Against Financial District Building". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Noelle Knox and Martha T. Moor (October 24, 2001). "'Wall Street' migrates to Midtown". USA Today. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c Leslie Eaton and Kirk Johnson (September 16, 2001). "AFTER THE ATTACKS: WALL STREET; STRAINING TO RING THE OPENING BELL -- AFTER THE ATTACKS: WALL STREET". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Landmark Types and Criteria - LPC". Welcome to NYC.gov. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "How to List a Property". National Register of Historic Places (U.S. National Park Service). November 26, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "Eligibility". National Historic Landmarks (U.S. National Park Service). August 29, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Discover New York City Landmarks". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved December 21, 2019 – via ArcGIS.

- ^ "21 West Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 16, 1998. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Historic Structures Report: Building at 21 West Street" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 11, 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: U.S. Custom House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 31, 1972. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Custom House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 14, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Custom House Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 9, 1979. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Bowling Green Fence" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 14, 1970. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Bowling Green" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 29, 1980. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bowling Green Offices Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Castle Clinton National Monument" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 15, 1966. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Castle Clinton" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: City Pier A" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 27, 1975. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Pier A" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 12, 1977. Retrieved February 2, 2020. - ^ "Cunard Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Cunard Building, First Floor Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Downtown Athletic Club Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 14, 2000. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Battery Park Control House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. May 6, 1980. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Interborough Rapid Transit System, Battery Park Control House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 22, 1973. Retrieved February 2, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: International Mercantile Marine Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. March 2, 1991. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"International Mercantile Marine Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 16, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: James Watson House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 24, 1972. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"James Watson House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Whitehall Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 17, 2000. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: American Stock Exchange Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1978. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"New York Curb Exchange (incorporating the New York Curb Market Building), later known as the American Stock Exchange" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 26, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "American Express Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 12, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: West Street Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 12, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"West Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 19, 1998. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "94 Greenwich Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 23, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "American Telephone and Telegraph Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 25, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"American Telephone and Telegraph Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 25, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Empire Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 13, 1983. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Empire Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Old New York County Lawyers' Association Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 30, 1982. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

"New York County Lawyers' Association Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Retrieved February 16, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: New York Evening Post Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 16, 1977. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

"New York Evening Post Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Retrieved February 16, 2020. - ^ "Robert and Anne Dickey House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 28, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Saint George's Syrian Catholic Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 14, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Saint Paul's Chapel" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 23, 1980. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Saint Paul's Chapel and Graveyard" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 18, 1966. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Saint Peter's Roman Catholic Church" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 23, 1980. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"St. Peter's Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ "Trinity Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 7, 1988. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Realty Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 7, 1988. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Trinity Church and Graveyard" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 8, 1976. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Trinity Church and Graveyard" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 16, 1966. Retrieved July 28, 2019. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Barclay-Vesey Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 30, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Barclay-Vesey Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 1, 1991. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Barclay-Vesey Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 1, 1991. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: New York Cotton Exchange" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 7, 1972. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Hanover Bank" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "1 Wall Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 6, 2001. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Beaver Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 6, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Beaver Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "J. & W. Seligman & Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "City Bank-Farmers Trust Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: 23 Wall Street Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 19, 1972. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"J. P. Morgan & Co. Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Standard Oil Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: National City Bank Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 30, 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"National City Bank Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"National City Bank Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 12, 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: American Bank Note Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 30, 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"American Bank Note Company Office Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Municipal Ferry Pier" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 12, 1976. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Whitehall Ferry Terminal, 11 South Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 25, 1967. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Broad Exchange Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 13, 1998. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Broad Exchange Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 27, 2000. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Delmonico's Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: First Police Precinct Station House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 29, 1982. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"First Precinct Police Station" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 20, 1977. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Fraunces Tavern" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. March 6, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Fraunces Tavern" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1978. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 9, 1985. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ 05001288.pdf "Historic Structures Report: Wall and Hanover Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 16, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

{{cite web}}:확인.url=값(도움말) - ^ "Bankers Trust Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "One Chase Manhattan Plaza" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 10, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Manhattan Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 16, 2000. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Manhattan Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 12, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Bank of New York & Trust Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 28, 2003. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Bank of New York & Trust Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 13, 1998. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Wallace Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 28, 2003. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"56-58 Pine Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 11, 1997. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Cities Service Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 21, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Cities Service Building, First Floor Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 21, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "90–94 Maiden Lane Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 1, 1989. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "American Surety Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Chamber of Commerce Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 6, 1973. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 18, 1966. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Down Town Association Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 11, 1997. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Equitable Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1975. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Equitable Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Federal Hall" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 15, 1966. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Custom House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Federal Hall Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 27, 1975. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. May 6, 1980. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Liberty Tower" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 15, 1983. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Liberty Tower" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 24, 1982. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Marine Midland Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Temple Court Building and Annex" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 10, 1998. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "63 Nassau Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 15, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "American Tract Society Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 15, 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bennett Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 21, 1995. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Corbin Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 18, 2003. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Corbin Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Excelsior Steam Power Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 13, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: John Street United Methodist Church" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 4, 1973. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"John Street Methodist Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ "Keuffel & Esser Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 26, 2005. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Morse Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 2006. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "New York Times Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 6, 1999. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Park Row Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 16, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Park Row Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 15, 1999. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Potter Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 7, 1996. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Fraunces Tavern Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 28, 1977. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Fraunces Tavern Block Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 14, 1978. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: South Street Seaport Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 12, 1978. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"South Street Seaport Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 10, 1977. Retrieved July 28, 2019. - ^ "Street Plan of New Amsterdam and Colonial New York" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 14, 1983. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Stone Street Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "IRT Subway System Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "New Amsterdam becomes New York". HISTORY. February 9, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Jacobs, Jaap (2009). The Colony of New Netherland. p. 32.

- ^ Park, Kingston Ubarn Cultural. "Dutch Colonization". nps.gov.

- ^ Schoolcraft, Henry L. (1907). "The Capture of New Amsterdam". English Historical Review. 22 (88): 674–693. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXII.LXXXVIII.674. JSTOR 550138.

- ^ "TO CLEAR BACK YARD OF WALL ST. DISTRICT; Bowling Green Neighborhood Association Reports Progress in Lower Manhattan. CITY OFFICIALS GIVE AID Work Said to be Experiment Offering Great Promise for a Community Plan". The New York Times. May 14, 1916. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b "Better than flying: Despite the attack on the twin towers, plenty of skyscrapers are rising. They are taller and more daring than ever, but still mostly monuments to magnificence". The Economist. June 1, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Daniel Gross (October 14, 2007). "The Capital of Capital No More?". The New York Times: Magazine. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ 월가가 폭발한 날, 베벌리 게이지: 테러의 첫 번째 시대의 미국 이야기.뉴욕: 옥스포드 대학 출판부, 2009; 페이지 160-161.

- ^ "DETECTIVES GUARD WALL ST. AGAINST NEW BOMB OUTRAGE; Entire Financial District Patrolled Following Anonymous Warning to a Broker". The New York Times. December 19, 1921. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Michael M. Grynbaum (June 18, 2009). "Stand That Blazed Cab-Sharing Path Has Etiquette All Its Own". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Michael Cooper (January 28, 1996). "NEW YORKERS & CO.: The Ghosts of Teapot Dome;Fabled Wall Street Offices Are Now Apartments, but Do Not Yet a Neighborhood Make". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Michael deCourcy Hinds (March 23, 1986). "SHAPING A LANDFILL INTO A NEIGHBORHOOD". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Laura M. Holson and Charles V. Bagli (November 1, 1998). "Lending Without a Net; With Wall Street as Its Banker, Real Estate Feels the World's Woes". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Charles V. Bagli (December 23, 1998). "City and State Agree to $900 Million Deal to Keep New York Stock Exchange". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Charles V. Bagli (May 7, 1998). "N.A.S.D. Ponders Move to New York City". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Noelle Knox and Martha T. Moor (October 24, 2001). "'Wall Street' migrates to Midtown". USA Today. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Bruce Lambert (December 19, 1993). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: LOWER MANHATTAN; At Job Lot, the Final Bargain Days". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Alex Berenson (October 12, 2001). "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE EXCHANGE; Feeling Vulnerable At Heart of Wall St". The New York Times: Business Day. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Dawsey, Josh (October 23, 2014). "One World Trade to Open Nov. 3, But Ceremony is TBD". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Yee, Vivian (November 9, 2014). "Out of Dust and Debris, a New Jewel Rises". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Verrill, Courtney (March 4, 2016). "New York City's $4 billion World Trade Center Transportation Hub is finally open to the public". Business Insider. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "World Trade Center transportation hub, dubbed Oculus, opens to public". ABC7 New York. March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ MARIA ASPAN (July 2, 2007). "Maharishi's Minions Come to Wall Street". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Plitt, Amy (March 9, 2016). "The Financial District's massive building boom, mapped". Curbed NY. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Patty Stonesifer and Sandy Stonesifer (January 23, 2009). "Sister, Can You Spare a Dime? I don't give to my neighborhood panhandlers. Should I?". Slate. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Sushil Cheema (May 29, 2010). "Financial District Rallies as Residential Area". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Michael Stoler (June 28, 2007). "Refashioned: Financial District Is Booming With Business". New York Sun. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Sandy keeps financial markets closed Tuesday". CBS News.

- ^ Bentley, Elliot (September 1, 2021). "How the 9/11 Attacks Remade New York City's Financial District". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ 뉴욕시 근린주택 집계 지역*, 2010, 인구과 - 뉴욕시 도시계획부, 2012년 2월.2016년 6월 16일에 접속.

- ^ 표 PL-P5 NTA: 에이커당 총인구 및 인구수 - 뉴욕시 근린주택표*, 2010년, 인구과 - 뉴욕시 도시계획부, 2012년 2월2016년 6월 16일에 접속.

- ^ 표 PL-P3A NTA: 상호 배타적 인종과 히스패닉 출신에 따른 총인구 - 뉴욕시 근린주택 집계 지역*, 2010, 인구과 - 뉴욕시 도시계획부, 2011년 3월 29일2016년 6월 14일에 접속.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Financial District (Including Battery Park City, Civic Center, Financial District, South Street Seaport and Tribeca)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "New Yorkers are living longer, happier and healthier lives". New York Post. June 4, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "NYC-Manhattan Community District 1 & 2--Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho PUMA, NY". Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Bob Pisani (May 18, 2018). "New 3 World Trade Center to mark another step in NYC's downtown revival". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ C. J. Hughes (August 8, 2014). "The Financial District Gains Momentum". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Council Members & Districts". New York City Council. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "District 1". New York City Council. March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "2012 Senate District Maps: New York City" (PDF). The New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ "NY Senate District 26". NY State Senate. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Elected Officials & District Map". New York State Board of Elections. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "2012 Assembly District Maps: New York City" (PDF). The New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ "New York State Assembly Member Directory". Assembly Member Directory. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ 인구통계학적 조사와 재배치에 관한 뉴욕주 입법 태스크포스 10번 지역구2017년 5월 5일 취득.

- ^ 뉴욕시 의회 선거구, 뉴욕주 인구통계 조사 및 재배치에 관한 입법 태스크포스.2017년 5월 5일 취득.

- ^ "NYPD – 1st Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "Downtown: Battery Park, Financial District, SoHo, TriBeCa – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "1st Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 4/Ladder Company 15/Decontamination Unit". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 6". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 10/Ladder Company 10". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Manhattan Hospital Listings". New York Hospitals. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Best Hospitals in New York, N.Y." US News & World Report. July 26, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Financial District, New York City-Manhattan, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Church Street". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Hanover". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Peck Slip". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Whitehall". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Financial District – MN 01" (PDF). Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ "Financial District New York School Ratings and Reviews". Zillow. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "Urban Assembly School of Business for Young Women, the". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Spruce Street School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Millennium High School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Leadership and Public Service High School". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Manhattan Academy For Arts & Language". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "High School of Economics and Finance". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "About the New Amsterdam Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "About the Battery Park City Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Biggest NY Subway Hub Opens; Expects 300,000 Daily". ABC News. December 10, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ "World Trade Center transportation hub, dubbed Oculus, opens to public". ABC7 New York. March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Brooklyn Bus Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Bronx Bus Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Staten Island Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 21, 2003). "The Ground Zero Memorial: Transportation; Free Bus Service Starts in Lower Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Downtown Connection Bus". www.downtownny.com. Alliance for Downtown New York. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "NYC DOT - Staten Island Ferry Schedule". Welcome to NYC.gov. January 1, 1980. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Route Map". NYC Ferry. November 2, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "Governors Island Ferry Service". New York City's Historic Battery Maritime Building. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ "One World Trade Center". The Skyscraper Center. CTBUH. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Murray, Matt; Kim, Eun Kyung (May 14, 2013). "Cheers Erupt as Spire Tops One World Trade Center". CNBC. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ^ Elizabeth Fazzare (June 11, 2018). "3 World Trade Center Is Officially Unveiled After Years of Delays". Architectural Digest.

- ^ "Building Overview". Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "American International". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "American International Building". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ 쿠오조, 스티브"도심의 파인 스트리트 70번지에 대한 새로운 계획은 하늘을 찌를 듯" 뉴욕 포스트(2013년 10월 29일)

- ^ "Four Seasons Hotel at 30 Park Place Will Open in July 2016". Zoe Rosenberg. August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "The Trump Building". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Trump Building". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "One Chase Manhattan Plaza". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "One Chase Manhattan Plaza". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Financial District, Manhattan". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- ^ "50 West Street". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "Goldman Sachs Headquarters". Emporis.com. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Goldman Sachs New World Headquarters". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "60 Wall Street". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "60 Wall Street". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "One Liberty Plaza". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "1 Liberty Plaza". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "20 Exchange Place". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "20 Exchange Place". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Three World Financial Center". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Three World Financial Center". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "HSBC Bank Building". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "HSBC Bank Building". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "55 Water Street". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "55 Water Street". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Bank of New York Building". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Bank of New York Building". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Two World Financial Center". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Two World Financial Center". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "One New York Plaza". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "One New York Plaza". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Home Insurance Plaza". Emporis.com. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Home Insurance Plaza". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

외부 링크

Wikivoyage의 맨해튼 파이낸셜 디스트릭트 여행 가이드

Wikivoyage의 맨해튼 파이낸셜 디스트릭트 여행 가이드- 금융가 사진

- Wikipages Financial District(위키파이낸셜 디스트릭트)는 Wiki 기반의 파이낸셜 디스트릭트 비즈니스 디렉토리입니다.