7 (뉴욕시 지하철 운행)

7 (New York City Subway service)  플러싱 로컬 플러싱 익스프레스 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 서단 | 34번가-허드슨 야드 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 동쪽 끝 | 플러싱-메인 스트리트 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 측점 | 22(현지 서비스) 18 (express서비스) 8 (초특급 서비스) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 압연주 | R188 418대(열차 38대, 오전 러시), R188 396대(열차 36대, 오후 러시)[1][2] (변경 가능한 주식양도) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 디포 | 코로나 야드 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 서비스 시작 | 1915년;1915) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

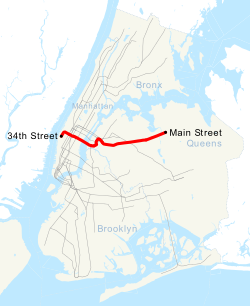

7 플러싱 로컬 및 <7> 플러싱 익스프레스는[3] 뉴욕 지하철의 A 부서에 있는 두 개의 고속 교통 서비스로, IRT 플러싱 라인 전체 길이에 따라 로컬 및 익스프레스 서비스를 제공합니다. 노선 엠블럼 또는 "총알"은 플러싱 라인을 제공하기 때문에 보라색으로 표시됩니다.[4]

퀸즈 플러싱의 메인 스트리트와 34번가 사이에 7대의 열차가 상시 운행됩니다.맨하탄 첼시의 허드슨 야드. 원형 탄환에 (7)로 표시된 지역 서비스는 상시 운영되며, 다이아몬드 모양 탄환에 <7>로 표시된 특급 서비스는 출퇴근 시간과 초저녁 피크 방향 및 특별 행사 시에만 운영됩니다.

7번 노선은 1915년 플러싱 라인이 개통되면서 운행을 시작했습니다. 1927년 이래로 7개 노선은 2015년 9월 13일 타임스퀘어에서 허드슨 야드까지 한 정거장 서쪽 연장을 제외하고는 대체로 동일한 노선을 유지하고 있습니다.

서비스이력

초기역사

1915년 6월 13일, IRT 플러싱 라인의 첫 번째 시험 열차가 그랜드 센트럴과 버논 대로-잭슨 애비뉴 사이를 운행했고, 뒤이어 6월 22일부터 수익 서비스가 시작되었습니다.[5] 플러싱 라인은 1916년 2월 15일 버논-잭슨 애비뉴에서 헌터스 포인트 애비뉴로 한 정거장 연장되었습니다.[6][7] 1916년 11월 5일 플러싱 라인은 퀸즈보로 플라자 역까지 동쪽으로 두 정거장 더 연장되었습니다.[8][9][7] 이 노선은 1917년 4월 21일 퀸즈보로 플라자에서 앨버티스 애비뉴(현재 103번가-코로나 플라자)까지 개통되었습니다.[8][10][11][12] 맨해튼 방향 선로의 앨버티스 애비뉴에서 111번가와 이전 터미널 사이를 왕복하는 셔틀 서비스가 1925년 10월 13일에 시작되었습니다.[13][14]

1926년 3월 22일 플러싱 라인 서비스가 그랜드 센트럴에서 5번가까지 서쪽으로 한 정거장 연장되었고, 이때 플러싱 라인의 그 부분이 개통되었습니다.[15][16]: 4 이 노선은 거의 정확히 1년 후인 1927년 3월 14일 타임스퀘어까지 연장되었습니다.[17]: 13 [18] 같은 해 5월 7일에 윌렛 포인트 대로까지 동쪽으로 연장된 노선이 개통되었지만,[19][17]: 13 첫 주에는 셔틀 열차가 운행을 시작할 때까지 운행을 했습니다.[20][21] 플러싱-메인 스트리트로의 동쪽 연장은 1928년 1월 21일에 문을 열었습니다.[22]

퀸스보로 플라자 동쪽에 있는 플러싱 라인의 서비스는 1912년부터 1949년까지 인터버러 래피드 트랜짓 컴퍼니(IRT)와 브루클린-맨하탄 트랜짓 코퍼레이션(BMT)이 공유했습니다. BMT 열차는 9번으로 지정된 반면 IRT 서비스는 지도에서만 7번으로 지정되었습니다.[23] IRT 노선은 1948년 "R-type" 롤링 스톡이 도입되면서 번호 지정이 이루어졌고, 각 서비스에 번호 지정이 있는 롤 사인이 포함되었습니다.[24] 타임스 스퀘어에서 플러싱까지의 경로는 7번으로 알려지게 되었습니다.[25]

익스프레스 서비스의 도입

1939년 뉴욕 만국 박람회를 위해 급행 열차가 1939년 4월 24일 운행되기 시작했습니다.[26] 첫 번째 열차는 오전 6시 30분에 메인 스트리트를 떠났습니다. IRT 익스프레스는 메인 스트리트와 타임스퀘어 사이를 9분마다 운행했고, BMT 익스프레스는 메인 스트리트와 퀸즈보로 플라자 사이를 운행했습니다. 메인 스트리트와 퀸즈보로 플라자 사이의 운행 시간은 15분, 메인 스트리트와 타임스퀘어 사이의 운행 시간은 27분이었습니다. 아침 러시에서 아침 러시에서 아침 6시 30분에서 10시 43분 사이에 맨해튼행 급행 운행. 오전 10시 50분 IRT의 경우 타임스퀘어에서, 11시 9분 퀸즈보로 플라자에서 BMT까지 메인 스트리트로 급행 운행이 시작되어 오후 8시까지 계속되었습니다.[27]

1949년 10월 17일, 플러싱 라인의 공동 BMT/IRT 운행이 종료되어 플러싱 라인은 IRT의 책임이 되었습니다.[28] BMT/IRT 이중 서비스 종료 후, 뉴욕시 교통위원회는 플러싱 라인 승강장을 11 IRT 차량 길이로, BMT 아스토리아 라인 승강장을 10 BMT 차량 길이로 연장할 것이라고 발표했습니다. 1950년에 시작되는 이 프로젝트에는 미화 3,850,000달러(2022년에는 46,800,000달러에 해당)가 소요될 예정입니다. 플랫폼은 51피트 길이의 IRT 차량 9대 또는 60피트 길이의 BMT 차량 7대만 미리 장착할 수 있었습니다.[29][30]

1953년 3월 12일, 두 대의 9량 급행 열차가 플러싱-메인 스트리트에서 타임스퀘어까지 아침 러시아워에 운행하기 시작했습니다.[31][32] Willets Point에 정차한 슈퍼 익스프레스는 Willets Point에서 정차한 후, Queensboro Plaza로 가는 모든 정류장을 건너뛰고 Woodside 및 Junction Boulevard 급행 정류장을 우회합니다. 러닝 타임은 25분에서 23분으로 단축되었습니다.[33] 1955년 8월 12일부터 4개의 슈퍼 익스프레스가 아침 출근 시간대에 운행되었습니다.[34] 1953년 9월 10일, 타임스퀘어에서 출발한 두 대의 급행 열차가 저녁 러시아워에 초특급 열차로 전환되었습니다.[33] 초특급은 1956년 1월 13일과 [35][36]1956년 12월 14일에 각각 아침 러시와 저녁 러시로 운행이 중단되었습니다.[35] 1954년 3월 20일 휴일 및 토요일 특급 운행이 중단되었습니다.[37]

1962년 11월 1일, 50대의 R17(번호 6500-6549)이 본선 IRT에서 7번으로 이관되어 10량 운행이 가능하게 되었습니다. IRT가 두 번째 차장 없이 10량짜리 열차를 운행한 것은 이번이 처음이었습니다.[38] 1964년 4월 플러싱 메도스-코로나 파크에서 열린 1964-1965 세계 박람회와 함께 열차는 11량으로 연장되었습니다.[39][40] 플러싱 라인은 이 향상된 서비스로 430대의 신형 R33 및 R36 "세계 박람회" 자동차를 받았습니다.[41]: 137

재활서비스 패턴

1차 개보수

1985년 5월 13일부터 1989년 8월 21일까지 IRT 플러싱 라인은 새로운 선로 설치, 역 구조물 보수, 노선 인프라 개선 등의 개선을 위해 정비되었습니다. 프로젝트에는 7천만 달러가 들었습니다.[42] 열차 접근성을 제공하기 위해 역 지역의 로컬 선로에서 선로 공사가 수행될 때 노선을 따라 지역 역에 임시 승강장이 건설되었습니다.[43]

주요 요소는 퀸즈 대로 고가의 레일을 교체하는 것이었습니다. 1970~80년대 플러싱 라인에 '코드 레드' 결함이 광범위하게 발생할 정도로 지하철이 노후화될 수 있었고, 바람이 시속 65마일(105km)을 넘으면 열차가 운행되지 않을 정도로 흔들릴 정도로 높은 구조물을 지탱하는 기둥도 있었기 때문입니다. <7> 프로젝트 기간 동안 급행 서비스가 중단되었지만 메츠 게임과 플러싱 메도우스 파크 이벤트에 추가로 7개의 서비스가 제공되었습니다. 프로젝트 기간 동안 평일 최대 10분, 주말 20분 지연이 예상되었습니다. 뉴욕시 교통국(NYCTA)은 <7> 급행 서비스를 대체하기 위해 고속버스 운행을 고려했지만, NYCTA에는 없었던 수백 대의 버스가 필요하기 때문에 이를 반대하기로 결정했습니다. 건설 프로젝트 동안 NYCTA는 지역 선로에서 시간당 25대의 열차를 운행했는데, 이는 사전에 지역과 급행을 구분하는 시간당 28대의 열차보다 3대 적은 수치입니다. 프로젝트 기간 동안 7일의 실행 시간이 10분 연장되었습니다.[44]

급행 운행 재개

이 프로젝트는 1989년 6월에 완료되었는데, 이는 예정된 1989년 12월 완공보다 6개월 앞서 이루어진 것입니다.[45] NYCTA는 1989년 6월 29일에 제안된 특급 서비스 복원에 관한 공청회를 열었습니다. NYCTA는 1989년 7월에 정기적인 A Division 일정 변경에 맞춰 급행 서비스를 시행할 것을 제안했습니다. 1988년부터 급행 서비스를 복원하기 위한 옵션을 계획하기 시작했습니다. 1985년 5월 이전에 시행된 서비스 패턴, 모든 지역 서비스의 지속, 윌렛 포인트와 퀸즈보로 플라자 사이를 쉬지 않고 운행하는 슈퍼 익스프레스 서비스, 스킵-스톱 익스프레스 서비스 등을 포함한 옵션이 지역 커뮤니티 보드에 제시되었습니다.[46]

1985년 5월 이전에는 맨해튼까지 6시 30분부터 9시 45분까지, 메인 스트리트까지 3시 15분부터 7시 30분까지 급행 열차가 운행되었습니다. 급행은 평균 3분, 현지인은 6분 간격으로 운행했습니다. 운행 간격이 일정하지 않아 실제로는 2분 후에 다른 급행 열차가 뒤따랐고, 다음 급행 열차가 도착할 때까지 4분이 더 지나야 했습니다. 급행열차에 대한 수요가 많아 급행과 현지인의 이러한 구분이 이루어졌습니다. 이전 여행에서 4분 후에 도착한 급행 열차는 2분 후에 도착한 급행 열차보다 승객이 두 배나 많았습니다. 특급 서비스가 폐지되고 33번가에서 신뢰할 수 없는 합병이 이루어지면서 서비스 신뢰성이 높아져 정시 성능이 95%[46]를 초과하는 경우가 많았습니다. 지역 전용 서비스를 유지하는 것은 맨해튼으로 향하는 정션 블러바드의 동쪽에서 탑승하는 많은 승객들의 시간을 절약하지 못했을 것이고, 지하철을 가장 효율적으로 이용할 수 있도록 제공하지 못했을 것이고, 혼잡한 퀸즈 블러바드 라인에 매력적인 대안을 제공하지 못했을 것이기 때문에 기각되었습니다. 슈퍼 익스프레스 서비스는 1985년 이전 서비스 패턴의 문제점을 재현하면서 각 익스프레스마다 2~3명의 현지인이 필요하다는 요구가 있어 기각되었습니다. 다른 급행 서비스 패턴에 따라 시간당 30대의 열차를 수용할 수 있는 시간당 24대로 노선 용량을 제한한 것에 대해 스킵-스톱 서비스가 기각되었습니다.[46]

NYCTA는 기존 수준의 신뢰성을 유지하고, 로컬 서비스를 기존 수준 또는 1985년 이전 수준보다 높은 수준으로 실행하고, 실행 시간을 더 빠르게 제공하는 것을 목표로 서비스 계획을 만들었습니다. NYCTA는 오전 6시 30분에서 10시 사이에 맨해튼으로,[45] 오후 3시 15분에서 8시 15분 사이에 플러싱으로 운행하는 급행 서비스의 재도입을 제안했습니다. 익스프레스 서비스는 61번가를 우회합니다.우드사이드(Woodside)는 급행 열차가 각 지역마다 한 대씩 운행할 수 있도록 하며, 급행 열차와 현지인 모두 4분마다 운행합니다. 고른 빈도로 급행과 현지인의 운행은 33번가에 도착하는 열차의 고른 간격에 도움이 될 것으로 기대했습니다. 빠른 급행 서비스로 인해 분기점 대로 북쪽에서 탑승하는 승객들이 붐비는 퀸즈 대로 라인으로 환승하는 것을 막을 수 있을 것으로 예상됩니다.[46] 우드사이드를 급행 정류장으로 제거한 것은 부분적으로 역의 열차가 지역과 급행 사이를 환승하는 승객에 의해 지연될 것이기 때문에 33번가 합병에서 시간을 절약할 수 없었습니다.[47][48] 1989년 7월 28일, MTA(Metropolitan Transport Authority) 위원회는 5대 3의 투표로 변경을 승인했습니다.[49] <7> 급행 운행은 1989년 8월 21일에 복구되었고, 7월부터 연기되었습니다.[50][51]: 17 고속 서비스로 메인 스트리트에서 맨해튼까지 6분, 정션 블러바드까지 4분이 절약되었습니다.[45] 1989년 9월, 200명의 승객과 공화당 시장 후보 루돌프 줄리아니는 61번가 역에서 급행 서비스 폐지에 항의하기 위해 집회를 열었습니다.[47] 1992년 2월 10일, 지역사회의 반대로 급행 운행이 6주간의 시험 운행으로 우드사이드에 정차를 재개했습니다.[52]

2차 개보수

1990년대 중반, MTA는 선로를 밸러스트로 지지하는 데 사용되었던 암석이 배수 불량으로 느슨해지면서 퀸즈 대로 고가 고가 교량 구조물이 불안정하다는 것을 발견했고, 이는 결국 콘크리트 구조물의 전체적인 건전성에 영향을 미쳤습니다. <7> 61번가 사이에 급행 운행이 다시 중단되었습니다.우드사이드와 퀸즈보로 플라자; 4개의 중간역에 급행 선로에 접근할 수 있는 임시 승강장이 설치되었습니다.[53] 작업은 1993년 4월 5일에 시작되었습니다.[54][55] 1997년 3월 31일 고가교 재건축 공사가 예정보다 빨리 끝나자 <7> 급행 운행이 전면 재개되었습니다.[56] 이 기간 내내 라이더십은 꾸준히 성장했습니다.[57]

확장 및 CBTC

Jacob K 근처 34번가와 11번가까지 서쪽과 남쪽으로 이동하는 7번 지하철 연장. 허드슨 야드에 있는 재비츠 컨벤션 센터는 5번이나 지연되었습니다.[58] 34번가-허드슨 야드 역은 원래 2013년 12월에 개장할 예정이었으나 2014년 5월로 연기되었습니다. 그리고 다시 2015년 9월 13일로 미뤘고, 그 이후로 승객들에게 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다.[59] 하지만 전체적인 역 건설 사업은 2018년 9월 초가 되어서야 완료되었습니다.[60][61]

2010년, 뉴욕시 공무원들은 허드슨 강을 건너 뉴저지(New Jersey)의 시카커스 정션(Secaucus Junction) 기차역까지 서비스를 더 연장하는 것을 고려하고 있다고 발표했습니다.[62] 이 프로젝트는 마이클 블룸버그 뉴욕 시장과 크리스 크리스티 뉴저지 주지사의 지원을 받았지만,[63] 2013년 조지프 로타 MTA 회장은 뉴저지 연장을 추진하지 않을 것이라고 발표했습니다. 게이트웨이 터널 프로젝트는 앰트랙과 NJ 트랜싯 열차를 위해 맨해튼으로 가는 새로운 터널을 수반합니다.[64] 2018년 2월 뉴욕과 뉴저지 항만청, MTA, NJ Transit 간의 공동 노력의 일환으로 이 연장이 다시 검토되었습니다.[65][66][67]

2008년, MTA는 통신 기반 열차 제어(CBTC)를 수용하기 위해 7가지 서비스를 전환하기 시작했습니다. 원래 5억 8,590만 달러가 소요될 것으로 예상되었던 CBTC의 설치는 시간당 2대의 추가 열차와 7 지하철 연장을 위한 2대의 추가 열차를 허용하기 위한 것으로, 용량을 7% 증가시켰습니다.[68] 구 남부 터미널인 타임스퀘어에서는 범퍼 블록으로 인해 7일 운행이 시간당 27대로 제한되었습니다. 34번가에 있는 신남방 터미널 –허드슨 야드에는 러시아워 열차를 보관할 수 있는 테일 트랙이 있으며, 서비스 빈도를 시간당 29대로 늘릴 수 있습니다.[68] 2013년부터 2016년까지 A 사업부용 CBTC 호환 신차(R188 계약)가 인도되었습니다.[68] 2017년 10월 CB메인 스트리트에서 74번가까지 TC 시스템이 활성화되었습니다.[69]: 59–65 2018년 11월 26일, 수많은 지연 끝에 나머지 7개 노선에서 CBTC가 활성화되었습니다.[70]

2023년 6월 26일부터 2024년 1월까지 <7> 급행열차는 플러싱선을 따라 개보수 공사로 퀸즈보로 플라자와 74번가-브로드웨이 사이에 모든 정차를 하고 있습니다.[71]

압연주

7편성은 11량 편성으로 운행되며, 7편성 한 편성의 차량 수는 다른 어떤 뉴욕 지하철 운행보다 많습니다. 그러나 이 열차는 11대의 "A" 디비전 열차가 565피트(172m) 길이에 불과한 반면, 10대의 60피트(18m) 또는 8대의 75피트(23m) 차량으로 구성된 표준 B 디비전 열차는 600피트(180m) 길이이기 때문에 시스템에서 가장 길지 않습니다.[72]

함대사

7호는 거의 모든 역사를 통틀어 스타인웨이 로우-V를 시작으로 나머지 IRT와 별도의 함대를 유지해 왔습니다. 스타인웨이는 1915년에서 1925년 사이에 스타인웨이 터널에 특별히 사용하기 위해 지어졌습니다. 그들은 스타인웨이 터널의 가파른 등급(4.5%)을 오르기 위해 특별한 기어비를 가지고 있었는데, 이는 표준 인터버러 장비가 할 수 없는 일이었습니다.[73]

1938년, 세계 박람회 Lo-V 자동차 주문이 세인트루이스에 접수되었습니다. 루이 자동차 회사. 이 차들은 각 자동차 끝에 전정이 없다는 점에서 IRT "전통"에서 벗어났습니다. 또한 당시 IRT가 파산했기 때문에 자동차는 단일 종단 자동차로 만들어졌으며 한쪽에는 모터맨을 위한 열차 제어 장치가, 다른 한쪽에는 차장을 위한 문 제어 장치가 장착되어 있었습니다.[74][75]

1948년부터는 R12, R14, R15가 7호기에 납품되었습니다. 1962년 11월 1일, 50대의 R17(6500-6549)이 본선 IRT에서 7번으로 이관되어 10량 운행이 가능하게 되었습니다. IRT가 두 번째 차장 없이 10량짜리 열차를 운행한 것은 이번이 처음이었습니다.[38]

1964년, 그림 창 R33S와 R36 자동차는 1964년 뉴욕 세계 박람회에 맞춰 구형 R12, R14, R15, R17을 대체했습니다. 1965년 초, NYCTA는 세계 박람회 방문객들을 돕기 위해 그 노선의 모든 역과 환승 지점을 나타내는 띠 지도를 그 노선의 430대의 자동차에 각각 배치했습니다. 이 혁신은 다른 서비스에 사용되지 않았으며, 롤링 스톡을 서로 공유했기 때문에 자동차가 잘못된 스트립 맵을 가질 수 있었습니다.[76]

레드버드 7호는 레드버드 차량을 이용한 마지막 운행이었으며, 2002년 2월까지 레드버드 7호의 차량은 모두 R33S/R36 레드버드 열차로 구성되어 있었습니다. 2001년에 R142/R142A 차량이 출시되면서 교통국은 모든 레드버드 차량의 퇴역을 발표했습니다. 2002년 1월부터 2003년 11월까지 봄바디어가 제작한 R62A 차량은 7일부터 레드버드 차량을 순차적으로 대체했습니다. R62A는 2002년 2월 19일 7번 노선에서 첫 운행을 시작했습니다.[77] 2003년 11월 3일, 마지막 레드버드 열차는 타임스퀘어와 당시 이름이 붙여졌던 윌렛 포인트-시어 스타디움 사이를 모든 정거장으로 종착지를 정했습니다.[78] 2000년 뉴욕 양키스와의 월드시리즈 때는 플러싱 라인이 시티필드와 이전 시어스타디움에 인접해 있었기 때문에 이 서비스로 달리는 레드버드 차량 여러 대가 메츠 로고와 색상으로 장식됐습니다.[79]

2008년까지 7번의 모든 R62A는 급행 열차와 지방 열차를 구분하기 위해 LED 표시등으로 업그레이드되었습니다. 이 표지판은 각 자동차의 측면에서 발견되는 롤 사인에 있습니다. 로컬은 7발 주변의 녹색 원이고 익스프레스는 빨간색 다이아몬드입니다. 이전에 롤 사인은 아래에 "Express"라는 단어와 함께 (7)(원 안에) 또는 <7>(다이아몬드 안에)을 보여주었습니다.[80]

R62A는 2014년 1월부터 2018년 3월 30일까지 플러싱 라인의 자동화 장비에 대비하여 R188에 의해 대체되었습니다. 퇴역한 R62A는 6편성으로 돌아갔고, 그 중 많은 R142A가 타고 R188로 개조되었습니다.[81][82] 2013년 11월 9일 R188편성의 첫차가 여객 운행을 시작했습니다. 2016년까지 CBTC가 장착된 R188 열차 세트의 대부분은 7번 열차에 있었고, 2018년 3월 30일까지 마지막 R62A 열차는 R188 차량에 의해 대체되었습니다.[83][84]

닉네임

7호선은 비공식적으로 "인터내셔널 익스프레스"[85]와 "오리엔트 익스프레스"라는 별명으로 불리는데,[86] 특히 루스벨트 애비뉴를 따라 이민자들이 거주하는 여러 다른 민족 지역을 여행하기 때문이기도 하고, 1964-65년 뉴욕 만국 박람회로 가는 주요 지하철 노선이었기 때문이기도 합니다.[87][88] 1999년 6월 26일, 영부인 힐러리 클린턴과 미국 교통부 장관 로드니 E. 슬레이터는 7개 노선을 루이스와 클라크 국립 역사탐방로, 지하 철도 등 15개 노선과 함께 내셔널 밀레니엄 트레일("International Express"라는 이름으로)로 지정했습니다.[89][90]

경로

서비스패턴

다음 표는 7 및 <7>에서 사용하는 선과 지정된 시간에 경로를 나타내는 음영 상자를 보여줍니다.[91]

| 선 | 부터 | 로. | 타는 곳 | 시대 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 언제나 | 러시아워, 피크방향 | ||||

| IRT 플러싱 라인(풀 라인) | 플러싱-메인 스트리트 | 74번가-브로드웨이 | 표현 | ||

| 현지의 | |||||

| 74번가-브로드웨이 | 로슨 가 33번가 | 현지의 | |||

| 퀸즈보로 플라자 | 34번가-허드슨 야드 | 모든. | |||

<7> 열차는 일반적으로 퀸즈보로 플라자 동쪽에서 급행으로 운행합니다. 2023년[update] 6월 현재 IRT 플러싱 라인의 구조적 개조로 인해 <7> 열차는 74번가-브로드웨이 동쪽에서만 급행 운행합니다.[92]

뉴욕 메츠의 주야간 및 주말 시티 필드에서 열리는 뉴욕 메츠 경기와 US 오픈 테니스 경기가 끝난 후에는 메츠-윌리츠 포인트에서 출발하여 정션 블러바드를 경유하여 맨해튼으로 가는 특급 서비스를 제공합니다. 헌터스 포인트 애비뉴와 버논 대로–잭슨 애비뉴.[93]

측점

7 및 <7>은 모두 IRT 플러싱 라인에서 작동합니다.[3]

파란색으로 표시된 역은 슈퍼 익스프레스 게임 스페셜이 제공하는 정류장을 나타냅니다.

| 역 서비스 범례 | |

|---|---|

| 항상 멈춥니다. | |

| 심야시간을 제외한 모든 시간대에 정차합니다. | |

| 평일 낮 시간대에 중지 | |

| 피크 방향으로만 러시아워를 중지합니다. | |

| 폐역 | |

| 기간내역 | |

| 스테이션은 미국 장애인법을 준수합니다. | |

| 스테이션은 미국 장애인법을 준수합니다. 지시된 방향으로만 | |

| 메자닌 전용 엘리베이터 이용 | |

Lcl | Exp | 측점 | 지하철 환승 | 연결/참고 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 퀸즈 | ||||||

| 플러싱 라인 | ||||||

| 플러싱-메인 스트리트 | 플러싱-메인 스트리트에 있는 LIRRP 포트 워싱턴 지점 Q44 버스 서비스 선택 라과디아 공항행 Q48 버스 | |||||

| 메츠-윌리츠 포인트 | ↑[a][94] | Mets-Willets Point에 있는 LIRRPort Washington 지점 라과디아 공항행 Q48 버스 일부 러시아워 여행은 이 역에서[b] 시작되거나 종료됩니다. 초특급 34번가 여행 –허드슨 야드는 이 역에서 출발합니다. | ||||

| 111번가 | 라과디아 공항행 Q48 버스 맨해튼행 열차는 2024년 봄까지 보수 공사 때문에 여기서 멈추지 않을 것입니다.[95] | |||||

| 103번가-코로나 플라자 | ||||||

| 분기점 대로 | 라과디아 공항행 Q72 버스 | |||||

| 90번가-엘름허스트 애비뉴 | ||||||

| 82번가-잭슨 하이츠 | 맨해튼행 열차는 2024년 봄까지 보수 공사 때문에 여기서 멈추지 않을 것입니다.[95] | |||||

| 74번가-브로드웨이 | E | 라과디아 공항으로 가는 Q47 버스(마린 에어 터미널만 해당) Q53 버스 서비스 선택 Q70 라과디아 공항으로 가는 버스 서비스 선택 | ||||

| 69번가 | 라과디아 공항으로 가는 Q47 버스(마린 에어 터미널만 해당). | |||||

| 61번가-우드사이드 | Woodside의 LIRRCity 터미널 존 Q53 버스 서비스 선택 Q70 라과디아 공항으로 가는 버스 서비스 선택 | |||||

| 52번가 | ||||||

| 46번가-블리스 스트리트 | ||||||

| 로워리 스트리트 40번가 | ||||||

| 로슨 가 33번가 | ||||||

| 퀸즈보로 플라자 | NW(BMT 아스토리아 선) | |||||

| 코트 스퀘어 | G(IND 크로스타운 선) EF <F> (코트 스퀘어의 IND Queens Boulevard Line – 23번가) | |||||

| 헌터스 포인트 애비뉴 | Hunterspoint Avenue의 LIRR City 터미널 존(피크 시간만 해당) | |||||

| 버논 대로-잭슨 애비뉴 | LIRR City Terminal Zone at Long Island City(피크 시간만 해당) | |||||

| 맨해튼 | ||||||

| 그랜드 센트럴-42번가 | 4 S(42번가 셔틀) | 그랜드 센트럴 터미널의 지하철-북단 철도 그랜드 센트럴 매디슨의 롱아일랜드 레일로드 | ||||

| 5번가 | B | |||||

| 타임스퀘어-42번가 | 13(IRT 브로드웨이-세븐 애비뉴 라인) ACE(42번가-항만청 버스 터미널의 IND 8번가 선) N S(42번가 셔틀) | 항만청 버스 터미널 M34A 버스 서비스 선택 | ||||

| 34번가-허드슨 야드 | M34 버스 서비스 선택 | |||||

대중문화에서

- 2000년 다큐멘터리 영화 #7번 열차: 이민자 여행은 매일 7번 열차를 타는 사람들의 민족적 다양성에 기반을 두고 있습니다.[96]

- 세븐 라인 아미(7 Line Army)는 뉴욕 메츠(New York Mets) 팬들의 모임으로, 7번 루트에서 이름이 유래되었습니다.[97]

- 1999년 스포츠 일러스트레이티드 인터뷰에서 당시 애틀랜타 브레이브스의 투수였던 존 로커는 7번 열차를 타는 것은 베이루트에서 보라색 머리를 한 아이와 에이즈에 걸린 퀴어들 옆에 있는 것과 같다고 주장했습니다. 베이루트는 네 명의 아이를 가진 20살짜리 엄마 바로 옆에 있습니다. 우울합니다. 제가 뉴욕에서 가장 싫어하는 것은 외국인들입니다. 여러분은 타임스퀘어에서 한 블록 전체를 걸어도 아무도 영어로 말하는 것을 들을 수 없습니다. 아시아인, 한국인, 베트남인, 인도인, 러시아인, 스페인인, 그리고 그 위에 있는 모든 것들. 도대체 어떻게 이 나라에 들어온 거지?"[98]

- 에어로소프트가 2015년 3월 출시한 PC 시뮬레이터 게임 '월드 오브 서브웨이 4'는 레드버드가 노선을 운행하던 시기의 7을 재현한 게임입니다. 다양한 조건의 주행 시뮬레이션은 물론 7의 작동과 느슨하게 관련된 스토리 라인이 있는 미션이 특징입니다.

- 2020년 1월, 배우 아욱와피나의 TV 쇼 노라 프롬 퀸즈를 홍보하기 위한 MTA와 코미디 센트럴 간의 합의의 일환으로, R188s의 7번 열차에 대한 기본 사전 녹화 방송이 일주일 동안 아욱와피나의 방송으로 대체되었습니다. Awkwafina의 발표는 표준 방송국 발표 외에도 농담을 특징으로 했습니다.[99][100][101] 이번 합의는 MTA가 광고의 한 형태로 열차 안내방송을 대체한 최초의 사례입니다.[102]

- 2022년 9월, 뉴욕 메츠의 텔레비전 방송국 아나운서 론 달링, 키스 에르난데스, 게리 코언이 7행을 따라 사전에 방송을 녹화했습니다.

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ '2021년 12월 19일부터 시행되는 갑(甲) 자동차 분할' 뉴욕 시 교통국, 운영 계획. 2021년 12월 17일

- ^ "Subdivision 'A' Car Assignments: Cars Required June 27, 2021" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 64 (7): 2. July 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ a b "7 Subway Timetable, Effective June 26, 2023". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ "mta.info - Line Colors". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on October 16, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ "Queensboro Tunnel Officially Opened — Subway, Started Twenty-Three Years Ago, Links Grand Central and Long Island City — Speeches Made in Station — Belmont, Shonts, and Connolly Among Those Making Addresses — $10,000,000 Outlay" (PDF). The New York Times. June 23, 1915. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Subway Extension Open - Many Use New Hunters Point Avenue Station" (PDF). The New York Times. February 16, 1916. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ^ a b Report of the Public Service Commission For The First District Of The State of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1916 Vol. 1. January 10, 1917.

- ^ a b Annual report — 1916-1917 (Report). Interborough Rapid Transit Company. December 12, 2013. hdl:2027/mdp.39015016416920.

- ^ "New Subway Link" (PDF). The New York Times. November 5, 1916. p. XX4. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Cunningham, Joseph; DeHart, Leonard O. (1993). A History of the New York City Subway System. J. Schmidt, R. Giglio, and K. Lang. p. 48. Archived from the original on December 31, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Transit Service on Corona Extension of Dual Subway System Opened to the Public" (PDF). The New York Times. April 22, 1917. p. RE1. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "To Celebrate Corona Line Opening" (PDF). The New York Times. April 20, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ "First Trains to be Run on Flushing Tube Line Oct. 13: Shuttle Operation Ordered to 111th Street Station on New Extension". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 5, 1925. p. 8. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Poor's Public Utility Section 1925. 1925. p. 523. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Fifth Av. Station of Subway Opened" (PDF). The New York Times. March 23, 1926. p. 29. Archived from the original on December 16, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Annual Report of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company For The Year Ended June 30, 1925. Interborough Rapid Transit Company. 1925. Archived from the original on December 31, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ a b State of New York Department of Public Service Metropolitan Division Transit Commission Seventh Annual Report For The Calendar Year 1927. New York State Transit Commission. 1928.

- ^ "New Queens Subway Opened to Times Sq" (PDF). The New York Times. March 15, 1927. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Corona Subway Extended" (PDF). The New York Times. May 8, 1927. p. 26. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Flushing to Celebrate" (PDF). The New York Times. May 13, 1927. p. 8. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Dual Queens Celebration" (PDF). The New York Times. May 15, 1927. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Flushing Rejoices as Subway Opens – Service by B.M.T. and I.R.T. Begins as Soon as Official Train Makes First Run – Hope of 25 Years Realized – Pageant of Transportation Led by Indian and His Pony Marks the Celebration – Hedley Talks of Fare Rise – Transit Modes Depicted" (PDF). The New York Times. January 22, 1928. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ Korman, Joseph (December 29, 2016). "Line Names". thejoekorner.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ Brown, Nicole (May 17, 2019). "How did the MTA subway lines get their letter or number? NYCurious". amNewYork. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Friedlander, Alex; Lonto, Arthur; Raudenbush, Henry (April 1960). "A Summary of Services on the IRT Division, NYCTA" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 3 (1): 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Fast Subway Service to Fair Is Opened" (PDF). The New York Times. April 25, 1939. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "First Flushing Express Train Runs Monday". New York Daily News. April 20, 1939. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Direct Subway Runs To Flushing, Astoria" (PDF). The New York Times. October 15, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Bennett, Charles G. (November 20, 1949). "Transit Platforms On Lines In Queens To Be Lengthened; $3,850,000 Program Outlined for Next Year to Care for Borough's Rapid Growth New Links Are To Be Built 400 More Buses to Roll Also — Bulk of Work to Be on Corona-Flushing Route Transit Program In Queens Outlined". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "37 Platforms On Subways To Be Lengthened: All Stations of B. M. T. and I.R.T.in Queens Included in $5,000,000 Program". New York Herald Tribune. November 20, 1949. p. 32. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1325174459.

- ^ "2 I.R.T. Expresses to Cut Flushing-Times Sq. Run". The New York Times. March 10, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "Super Express In Its First Run From Flushing: Journey to Times Square Is So Swift That It Even Leaves Bingham Behind". New York Herald Tribune. March 13, 1953. p. 19. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322299710.

- ^ a b Ingalls, Leonard (August 28, 1953). "2 Subway Lines to Add Cars, Another to Speed Up Service; 3 Subways To Get Improved Service". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "IRT-Flushing Will Add Fourth Super-Express". Long Island Star-Journal. Fultonhistory.com. August 6, 1955. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Linder, Bernard (December 1964). "Service Change". New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association.

- ^ "Queens I.R.T. Trains Cut; Evening Super Expresses Will Be Dropped on Monday". The New York Times. January 10, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "I.R.T. Service Reduced; Week-End Changes Made on West Side Local, Flushing Lines" (PDF). The New York Times. April 3, 1954. Archived from the original on December 31, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "R17s to the Flushing Line". New York Division Bulletin. Vol. 5, no. 6. Electric Railroaders' Association. December 1962. pp. M-8. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2018 – via Issuu.

- ^ Annual Report — 1962–1963. New York City Transit Authority. 1963.

- ^ "TA to Show Fair Train". Long Island Star – Journal. August 31, 1963. Retrieved August 30, 2016 – via Fulton History.

- ^ Sparberg, Andrew J. (2014). From a Nickel to a Token: The Journey from Board of Transportation to MTA. Empire State Editions. ISBN 9780823261932. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Slagle, Alton (December 2, 1990). "More delays ahead for No. 7 line". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ On May 13, Residents of Queens Are Going To Be Mad As Hell., New York City Transit Authority, May 1985

- ^ "Memorandum: Flushing Line project" (PDF). laguardiawagnerarchive.lagcc.cuny.edu. New York City Office of the Mayor. May 28, 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c Announcing <7> Flushing Line Express Service Starting Monday, August 21, 1989, New York City Transit Authority, 1989

- ^ a b c d "#7 Flushing Line Express Service" (PDF). laguardiawagnerarchive.lagcc.cuny.edu. New York City Transit Authority. May 4, 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Chittum, Samme (September 25, 1989). "Riders are expressive about No. 7: Elimination of 61st St. stop blasted for creating havoc". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Lubrano, Alfred (August 23, 1989). "Take No. 7 train, if you can". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 15, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Siegel, Joel (July 29, 1989). "2 train changes get OK". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Announcing #7 Express Service. Starting Monday, August 21". New York Daily News. August 20, 1989. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Annual Report on 1989 Rapid Routes Schedules and Service Planning. New York City Transit Authority. June 1, 1990. Archived from the original on December 31, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Attention 7 Customers". New York Daily News. February 7, 1992. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (October 9, 1995). "Along the Subway, a Feat in Concrete". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ "April 1993 Map Information". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. April 1993. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "The repairs we're making on the 7 line will take some time. Like 3-4 minutes per trip if you ride the express". New York Daily News. April 2, 1993. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "7 Express service is being restored between 61 Street/Woodside and Queensboro Plaza". New York Daily News. March 28, 1997. Archived from the original on June 12, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (February 16, 1997). "On the No. 7 Subway Line in Queens, It's an Underground United Nations". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Emma G. Fitzsimmons (March 24, 2015). "More Delays for No. 7 Subway Line Extension". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "New 34 St-Hudson Yards 7 Station Opens". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "MTA's 7 Line Extension Project Pushed Back Six Months". NY1. June 5, 2012. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "MTA Opens Second Entrance at 34 St-Hudson Yards 7 Station". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 1, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ "NYC Subway Line May Continue Into N.J." CBS 2 New York. November 17, 2010. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Mayor Bloomberg wants to extend 7 line to New Jersey". ABC7 New York. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ "MTA chief: No. 7 line won't be extended to NJ". New York Daily News. April 3, 2012. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ "Cross-Hudson study options include 7 line extension into NJ". am New York. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "7 Train To Secaucus Idea Resurrected". Secaucus, NJ Patch. March 1, 2018. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Martinez, Jose (February 28, 2018). "Proposal to extend 7 train into New Jersey revived". NY1. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c MTA의 자본 프로그램에 대한 Q&A 2010-2014년 3월 2일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브

- ^ Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting April 2018 (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. April 23, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Nessen, S. (November 27, 2018). "New Signals Fully Installed on 7 Line, but When Will Riders See Improvements?". Gothamist. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ "MTA Announces Service Changes on 7 Line to Accommodate Station Enhancements at 61 St-Woodside and 74 St-Broadway". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 25, 2023. Archived from the original on July 31, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Dougherty, Peter (2006) [2002]. Tracks of the New York City Subway 2006 (3rd ed.). Dougherty. OCLC 49777633 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sansone, Gene (2004). New York Subways. JHU Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-8018-7922-1.

- ^ Cudahy, B.J. (1995). Under the Sidewalks of New York: The Story of the Greatest Subway System in the World. Fordham University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8232-1618-5. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ "The Interborough Fleet, 1900-1939 (Composites, Hi-V, Low-V)". www.nycsubway.org. January 17, 1916. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Annual Report 1964–1965. New York City Transit Authority. 1965.

- ^ "New York City Subway Car Update" (PDF). The Bulletin. Vol. 61, no. 8. Electric Railroaders' Association. August 2018. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 27, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Luo, Michael (November 4, 2003). "Let Go, Straphangers. The Ride Is Over". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ The subway series: the Yankees, the Mets and a season to remember. St. Louis, Mo.: The Sporting News. 2000. ISBN 0-89204-659-7.

- ^ Donohue, Pete (April 1, 2008). "On No. 7 trains, red diamond means express, a green circle for local". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Rubinstein, Dana (September 5, 2012). "M.T.A. to upgrade 7 line by trading old cars to Lexington Avenue". Capital New York. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Moving Forward Accelerating the Transition to Communications-Based Train Control for New York City's Subways" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. May 2014. p. 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Mann, Ted (November 18, 2013). "MTA Tests New Subway Trains on Flushing Line". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "New Subway Cars Being Put to the Test". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. November 18, 2013. Archived from the original on May 15, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ "International Express". Columbia University Press. February 22, 2017. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Lewin, Tamar (November 20, 1988). "Long Island City, Woodside, Flushing: Stops Along the Way; No. 7 Line -- The Orient Express". The New York Times Magazine. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ "The International Express: Around the World on the 7 Train". Queens Tribune. Archived from the original on January 22, 2003. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Cohen, Billie (January 14, 2008). "No. 7 Train From Flushing-Main Street to Times Square". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ "First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, U.S. Transportation Secretary Slater Announce 16 National Millennium Trails". White House Millennium Council. June 26, 1999. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ "The No. 7 'International Express' Rolls Into History". Queens Courier. July 8, 1999. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ "Subway Service Guide" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ "MTA Announces Service Changes on 7 Line to Accommodate Station Enhancements at 61 St-Woodside and 74 St-Broadway". MTA. May 25, 2023. Archived from the original on July 31, 2023. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ "The MTA Is Your Ride to All Yankees and Mets Home Games". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "Mets-Willets Point Station: Accessibility on game days and special events only". New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "Improving the 7 Line". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. November 22, 2023. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ The Newsletter of the International Documentary Association. International Documentary Association. 2001. Archived from the original on November 23, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Colton, Chris (March 26, 2013). "860 Mets Fans Strong, Opening Day Just The Start For 'The 7 Line Army'". WCBS-TV. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ "At Full Blast Shooting outrageously from the lip, Braves closer John Rocker bangs away at his favorite targets: the Mets, their fans, their city and just about everyone in it". Sports Illustrated Vault Si.com. December 27, 1999. Archived from the original on November 29, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ Goldbaum, Christina (January 16, 2020). "Awkwafina's Latest Role: Subway Announcer. New Yorkers Have Thoughts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "'Stop Manspreading!': Queens Native Awkwafina Takes Over 7 Train Subway Announcement". NBC New York. January 16, 2020. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "Queens-born actress Awkwafina will voice 7 train announcements for a week before her new show premieres". amNewYork. January 16, 2020. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "The MTA Is Now Turning Subway Announcements Into Ads, Starting With Awkwafina". Gothamist. January 16, 2020. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

외부 링크

| 외부 동영상 | |

|---|---|

- MTA 뉴욕 시 교통편 – 7 플러싱 지역

- MTA 뉴욕 시 교통편 – 7 플러싱 익스프레스

- MTA 지하철 시간—7 열차

- "7 Subway Timetable, Effective June 26, 2023". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- "Fiscal Brief September 2002" (PDF). (144KB)