토성

Saturn | |||||||||||||

| 지정 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 발음 | /settrn/ ( | ||||||||||||

의 이름을 따서 명명됨 | 토성 | ||||||||||||

| 형용사 | 토성어 /sɜtnirni/[2]n[3]/, 크로니어 /kkro[4] /niən/[5] | ||||||||||||

| 궤도 특성[11] | |||||||||||||

| 에폭 J2000.0 | |||||||||||||

| 아필리온 | 151만450km(10.1238AU) | ||||||||||||

| 근일점 | 1,352,55만 km (90412 AU) | ||||||||||||

| 1,433,53,000km(9.5826AU) | |||||||||||||

| 편심 | 0.0565 | ||||||||||||

| 378.09일 | |||||||||||||

평균 궤도 속도 | 9.68 km/s (6.01 mi/s) | ||||||||||||

| 317.020°[7] | |||||||||||||

| 기울기 | |||||||||||||

| 113.665° | |||||||||||||

| 2032년[9] 11월 29일 | |||||||||||||

| 339.392°[7] | |||||||||||||

| 이미 알려진 위성 | 83호, 공식 명칭 포함, 무수히 많은 추가 소성단.[10] | ||||||||||||

| 물리적[11] 특성 | |||||||||||||

평균 반지름 | 58,232 km (36,184 mi)[a] 9.1402 어스 | ||||||||||||

적도 반지름 |

| ||||||||||||

극 반지름 |

| ||||||||||||

| 평탄화 | 0.09796 | ||||||||||||

| 둘레 | |||||||||||||

| 용량 |

| ||||||||||||

| 덩어리 |

| ||||||||||||

평균 밀도 | 0.687 g/cm3 (0.0248 lb/cu in)[b] (물보다 작음) 0.1246 어스 | ||||||||||||

| 0.22[14] | |||||||||||||

| 35.5 km/s (22.1 mi/s)[a] | |||||||||||||

| 10시간 32m 36초 10.5433[6] 시간 | |||||||||||||

| 10h 33m 38s + 1m 52s (119ms). [15][16] | |||||||||||||

적도 회전 속도 | 9.87km/s(6.13mi/s, 35,500km/h)[a] | ||||||||||||

| 26.73° (궤도에 대하여) | |||||||||||||

| 40.589°, 4221hms | |||||||||||||

북극 편각 | 83.537° | ||||||||||||

| 알베도 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| -0.55[19] ~+1.17[19] | |||||||||||||

| 14.5 ~ 20.1 인치 (링 연결) | |||||||||||||

| 대기[11] | |||||||||||||

표면 압력 | 140kPa[22] | ||||||||||||

| 59.5km(37.0mi) | |||||||||||||

| 볼륨별 구성 |

| ||||||||||||

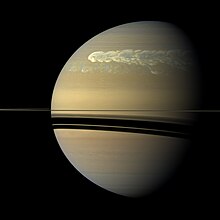

토성은 태양에서 여섯 번째 행성이며 태양계에서 목성에 이어 두 번째로 크다.이것은 평균 반지름이 지구의 [23][24]약 9.5배인 거대 가스 행성이다.이것은 지구의 평균 밀도의 8분의 1밖에 되지 않지만, 더 큰 부피로 인해 토성은 95배 이상 [25][26][27]더 무겁습니다.

토성의 내부는 철-니켈과 암석(실리콘과 산소 화합물)의 핵으로 구성되어 있을 가능성이 높습니다.그것의 핵은 깊은 금속 수소 층, 액체 수소와 액체 헬륨의 중간 층, 그리고 마지막으로 기체 외부 층으로 둘러싸여 있습니다.토성은 대기 상층부의 암모니아 결정 때문에 옅은 노란색을 띤다.금속 수소층 내의 전류는 토성의 행성 자기장을 발생시키는 것으로 생각되는데, 이것은 지구보다 약하지만 토성의 큰 크기 때문에 지구의 580배의 자기 모멘트를 가지고 있다.토성의 자기장 세기는 목성의 [28]20분의 1 수준이다.외부 분위기는 대체로 싱겁고 대조적이지 않지만, 오래가는 특징이 나타날 수 있다.토성의 풍속은 목성보다는 높지만 [29]해왕성보다는 높지 않은 1,800km/h에 이를 수 있다.

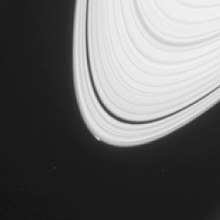

이 행성의 가장 주목할 만한 특징은 주로 얼음 입자로 구성되어 있고 적은 양의 암석 파편과 먼지로 이루어져 있는 눈에 띄는 고리 체계이다.적어도 83개의[30] 위성이 토성 주위를 돌고 있는 것으로 알려져 있으며, 그 중 53개는 공식적으로 이름이 붙여졌다; 이것은 토성의 고리에 있는 수백 개의 위성을 포함하지 않는다.토성의 가장 큰 달이자 태양계에서 두 번째로 큰 타이탄은 비록 질량이 적지만 수성보다 크며, 태양계에서 유일하게 실질적인 [31]대기를 가지고 있는 달이다.

이름 및 기호

토성은 로마의 부와 농업의 신이자 목성의 아버지의 이름을 따서 지어졌다.이것의 ![]() 천문학적 기호()는 그리스 옥시린쿠스 파피리로 거슬러 올라가며,[32] 이 행성의 그리스 이름인 크로누스의 줄임말로서 수평으로 획을 그은 그리스 카파로 볼 수 있다.그것은 나중에 이 이교도 상징을 기독교화하기 위해 16세기에 십자가가 꼭대기에 추가되면서 소문자의 그리스 에타처럼 보이게 되었다.

천문학적 기호()는 그리스 옥시린쿠스 파피리로 거슬러 올라가며,[32] 이 행성의 그리스 이름인 크로누스의 줄임말로서 수평으로 획을 그은 그리스 카파로 볼 수 있다.그것은 나중에 이 이교도 상징을 기독교화하기 위해 16세기에 십자가가 꼭대기에 추가되면서 소문자의 그리스 에타처럼 보이게 되었다.

로마인들은 한 주의 일곱 번째 요일을 토요일로 명명했는데,[33] 이는 토성의 이름을 따서 "새턴의 날"이라고 했습니다.

물리적 특성

토성은 주로 수소와 헬륨으로 이루어진 거대 가스 행성이다.그것은 단단한 [34]핵을 가지고 있을 가능성이 높지만 확실한 표면은 없다.토성의 자전은 토성이 타원형 구상체 모양을 갖도록 한다. 즉, 토성은 극지방에서 평평해지고 적도에서 부풀어 오른다.적도와 극지름은 거의 10% 차이가 난다: 60,268 km 대 54,364 km.[11]태양계의 다른 거대 행성인 목성, 천왕성, 해왕성 또한 타원형이지만 그 정도는 아니다.팽창과 회전 속도의 조합은 적도를 따라 8.96m/s의2 유효 표면 중력이 극지방의 74%이며 지구의 표면 중력보다 낮다는 것을 의미한다.그러나 적도 탈출 속도는 초속 36km로 [35]지구보다 훨씬 높다.

토성은 태양계에서 물보다 밀도가 낮은 유일한 행성입니다. 즉, 약 30% [36]정도 낮습니다.토성의 핵은 물보다 상당히 밀도가 높지만, 이 행성의 평균 비밀도는 대기 때문에 0.69g/cm이다3.목성의 [37]질량은 지구의 318배이고 토성은 지구의 [11]95배입니다.목성과 토성은 모두 합쳐서 [38]태양계 전체 행성 질량의 92%를 차지한다.

내부구조

수소와 헬륨이 대부분이지만, 토성 질량의 99.9%를 포함하는 반경에서 밀도가 0.01g/cm3 이상일 때 수소가 이상적이지 않은 액체가 되기 때문에 토성 질량의 대부분은 기체상에 있지 않다.토성 내부의 온도, 압력, 밀도는 모두 핵을 향해 꾸준히 상승하는데, 이것은 수소가 더 깊은 [38]층의 금속이 되게 만든다.

표준 행성 모형은 토성의 내부가 수소와 헬륨으로 둘러싸인 작은 암석 핵을 가지고 있고 [39]미량의 다양한 휘발성 물질을 가지고 있는 목성과 비슷하다는 것을 암시합니다.왜곡의 분석은 토성이 목성보다 훨씬 더 중심에서 응축되어 있고, 따라서 토성의 중심 근처에 수소보다 훨씬 더 많은 양의 밀도가 있는 물질을 포함하고 있다는 것을 보여준다.토성의 중심부에는 약 50%의 질량이 포함되어 있는 반면, 목성의 중심부에는 약 67%[40]의 수소가 포함되어 있습니다.

이 중심핵은 지구와 성분이 비슷하지만 밀도가 더 높습니다.토성의 중력 모멘트를 내부 물리 모델과 조합하여 조사함으로써 토성 중심핵의 질량에 제약을 가할 수 있게 되었습니다.2004년에 과학자들은 핵의 질량이 지구의 [41][42]9배에서 22배이며, 이는 직경이 약 25,000km에 [43]해당한다고 추정했다.하지만 토성의 고리를 측정한 결과 질량은 지구 17개 정도이고 반지름은 토성 전체 [44]반지름의 약 60퍼센트에 해당하는 훨씬 더 확산된 핵이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.이것은 더 두꺼운 액체 금속 수소 층에 둘러싸여 있고, 이어서 헬륨 포화 분자 수소의 액체 층이 점차 고도가 상승하는 기체로 전환됩니다.가장 바깥쪽 층은 1,000 킬로미터에 달하며 [45][46][47]가스로 구성되어 있다.

토성은 중심핵이 11,700°C에 이르는 뜨거운 내부를 가지고 있으며, 태양으로부터 받는 에너지보다 2.5배 더 많은 에너지를 우주로 방출한다.목성의 열에너지는 켈빈에 의해 생성됩니다.느린 중력 압축의 헬름홀츠 메커니즘은 토성의 열 생성을 설명하기에 충분하지 않을 수 있다. 왜냐하면 토성은 질량이 적기 때문이다.대안 또는 추가 메커니즘은 토성 내부 깊숙이 있는 헬륨 방울의 "억류"를 통해 열을 발생시키는 것일 수 있습니다.물방울이 낮은 밀도의 수소를 통해 내려올 때, 이 과정은 마찰에 의해 열을 방출하고 토성의 외부 층을 [48][49]헬륨으로 고갈시킵니다.이 하강하는 물방울들은 [39]핵을 둘러싼 헬륨 껍질로 축적되었을 수 있습니다.다이아몬드의 강우량은 목성과 거대 얼음 행성인[50] 천왕성과 [51]해왕성뿐만 아니라 토성 내부에서도 발생할 수 있다고 제안되어 왔다.

대기.

토성의 외부 대기는 96.3%의 수소 분자와 3.25%의 [52]헬륨을 함유하고 있다.헬륨의 비율은 태양에서 [39]이 원소의 풍부함에 비해 상당히 부족합니다.헬륨(금속성)보다 무거운 원소의 양은 정확히 알려져 있지 않지만, 그 비율은 태양계의 형성에 따른 원시적인 양과 일치한다고 가정한다.이 무거운 원소들의 총 질량은 토성 [53]중심부에 위치한 상당한 부분과 함께 지구 질량의 19-31배로 추정됩니다.

미량의 암모니아, 아세틸렌, 에탄, 프로판, 포스핀, 메탄 등이 토성의 [54][55][56]대기에서 검출되었다.상층 구름은 암모니아 결정으로 구성되어 있고, 하층 구름은 황화수소 암모늄(NHSH4) [57]또는 물로 구성되어 있는 것으로 보입니다.태양으로부터의 자외선은 상층 대기에서 메탄 광분해를 일으켜 일련의 탄화수소 화학반응을 일으켜 생성물이 에디와 확산에 의해 아래쪽으로 운반된다.이 광화학 주기는 토성의 연간 계절 [56]주기에 의해 조절된다.

클라우드 레이어

토성의 대기는 목성과 비슷한 띠 모양의 패턴을 보이지만, 토성의 띠는 적도 부근에서 훨씬 희미하고 넓다.이 띠들을 설명하는 데 사용되는 명명법은 목성과 동일합니다.토성의 미세한 구름 패턴은 1980년대 보이저 우주선이 비행할 때까지 관측되지 않았다.그 이후로, 지구 망원경은 정기적인 관측을 [58]할 수 있을 정도로 향상되었다.

구름의 구성은 깊이와 증가하는 압력에 따라 달라집니다.상층 구름층에서는 온도가 100~160K이고 압력이 0.5~2bar로 확장되는 구름은 암모니아 얼음으로 구성되어 있습니다.물 얼음 구름은 압력이 약 2.5 바인 수준에서 시작하여 온도가 185에서 270 K 사이인 9.5 바까지 확장됩니다.이 층에는 190-235K의 압력 범위 3~6bar의 수소 황화 암모늄 얼음이 혼합되어 있다.마지막으로 압력이 10~20bar이고 온도가 270~330K인 하층에는 수용액에 [59]암모니아가 포함된 물방울 영역이 포함되어 있습니다.

토성의 보통 무미건조한 대기는 때때로 긴 수명의 타원형이나 목성에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 다른 특징들을 보여줍니다.1990년 허블우주망원경은 보이저호 조우 때는 없었던 토성 적도 부근의 거대한 흰 구름을 촬영했고 1994년에는 또 다른 작은 폭풍이 관측됐다.1990년의 폭풍은 북반구 하지 [60]무렵에 토성년, 대략 30년에 한 번씩 일어나는 독특하지만 단명한 현상인 대백점의 한 예이다.이전의 그레이트 화이트 스팟은 1876년, 1903년, 1933년, 1960년에 관측되었으며 1933년 폭풍이 가장 유명했다.주기성이 유지되면 2020년경 [61]또 다른 폭풍이 발생할 것이다.

토성의 바람은 해왕성 다음으로 태양계의 행성들 중 두 번째로 빠르다.보이저 데이터는 최대 동풍 500m/s(1,800km/h)[62]를 나타낸다.2007년 카시니 우주선의 이미지에서 토성의 북반구는 천왕성과 비슷한 밝은 파란색을 보였다.그 색은 레일리 [63]산란 때문에 생긴 것 같다.서모그래피는 토성의 남극이 따뜻한 극 소용돌이를 가지고 있다는 것을 보여주었는데, 이것은 태양계에서 [64]그러한 현상의 유일한 사례이다.토성의 온도는 보통 -185°C인 반면, 소용돌이의 온도는 종종 [64]토성의 가장 따뜻한 점으로 추정되는 -122°C까지 도달합니다.

북극 육각형 구름 패턴

약 78°N의 대기 중 북극 소용돌이 주변의 지속적인 육각파 패턴이 보이저 [65][66][67]이미지에서 처음 발견되었습니다.육각형의 측면은 각각 약 14,500 km(9,000 mi) 길이로,[68] 지구의 지름보다 길다.전체 구조는 토성 내부의 [69]자전 주기와 같은 103924ms 주기h(행성의 전파 방출 주기와 같은 주기)로 회전한다.육각형 형상은 가시 [70]대기 중의 다른 구름처럼 경도가 변화하지 않습니다.그 패턴의 기원은 많은 추측의 문제이다.대부분의 과학자들은 이것이 대기 중에 있는 정파 패턴이라고 생각한다.다각형 모양은 [71][72]유체의 차등 회전을 통해 실험실에서 복제되었습니다.

남극 소용돌이

남극 지역의 HST 영상은 제트 기류의 존재를 나타내지만, 강한 극 소용돌이나 육각형 정재파는 [73]없다.NASA는 2006년 11월 카시니호가 명확하게 정의된 눈벽을 [74][75]가진 남극에 고정된 "허리케인 같은" 폭풍을 목격했다고 보고했다.아이월 구름은 이전에 지구 이외의 행성에서 목격된 적이 없었다.예를 들어, 갈릴레오 우주선의 사진들은 [76]목성의 대적점에 있는 아이월을 보여주지 않았다.

남극 폭풍은 수십억 [77]년 동안 존재했을지도 모른다.이 소용돌이는 지구의 크기와 맞먹으며 시속 [77]550km의 바람을 가지고 있다.

기타 기능

카시니는 "진주의 끈"이라는 별명을 가진 북위도에서 발견되는 일련의 구름 특징을 관찰했다.이러한 기능은 더 깊은 클라우드 [78]계층에 있는 클라우드 클리어입니다.

자기권

토성은 단순하고 대칭적인 형태인 자기 쌍극자를 가진 고유 자기장을 가지고 있다.적도에서의 강도 0.2가우스(δT)는 목성 주위의 자기장의 약 20분의 1이며 지구 [28]자기장보다 약간 약합니다.결과적으로, 토성의 자기권은 목성의 [80]자기권보다 훨씬 작다.보이저 2호가 자기권에 진입했을 때, 태양풍 압력이 높았고, 몇 시간 안에 확대되었지만, 자기권은 토성 반경 19, 즉 110만 km (712,000 mi)[81] 밖에 확장되지 않았고, 약 3일 [82]동안 유지되었다.아마도 자기장은 목성과 비슷하게 생성될 것입니다. 즉, 금속-수소 [80]발전기라고 불리는 액체 금속-수소층의 전류에 의해 생성될 것입니다.이 자기권은 태양으로부터 태양풍 입자를 편향시키는 데 효과적이다.달 타이탄은 토성 자기권 바깥을 돌고 타이탄 바깥 [28]대기의 이온화된 입자로부터 플라즈마를 발생시킨다.토성의 자기권은 지구의 자기권과 마찬가지로 오로라를 [83]생성한다.

궤도 및 회전

토성과 태양 사이의 평균 거리는 14억 킬로미터 이상입니다.평균 궤도 속도가 9.68 km/s일 때, 토성 10,759일(또는 약 9.68 km/s)[11]이 걸린다.29+1⁄2년)[84]을 사용하여 [11]태양 주위를 한 바퀴 돈다.결과적으로, 그것은 [85]목성과 거의 5:2의 평균 운동 공명을 형성합니다.토성의 타원 궤도는 지구의 [11]궤도면에 대해 2.48° 기울어져 있다.근일점 및 근일점 거리는 [11][86]각각 평균 9.195 및 9.957AU입니다.토성의 가시적인 특징은 위도에 따라 다른 속도로 회전하며, 목성의 경우처럼 여러 회전 주기가 다양한 영역에 할당되어 있습니다.

천문학자들은 토성의 자전 속도를 규정하기 위해 세 가지 다른 시스템을 사용한다.시스템 I은 101400ms(844.3°/d)의h 주기를 가지며 적도 구역, 적도 벨트 및 적도 벨트를 포함한다.극지방은 시스템 I과 유사한 회전 속도를 갖는 것으로 간주됩니다.북극과 남극 지역을 제외한 다른 모든 토성 위도는 시스템 II로 표시되며, 10m 38 25s.4(810.76°/d)의h 회전 주기를 할당받았다.시스템 III는 토성의 내부 회전 속도를 나타냅니다.Voyager 1과 Voyager [87]2가 감지한 행성으로부터의 무선 방출을 기준으로 시스템 III의 회전 주기는 10 39m 22.4(810s.8°/d)입니다h.시스템 III는 시스템 [88]II를 크게 대체했습니다.

실내의 회전 주기에 대한 정확한 값은 여전히 알 수 없습니다.2004년 토성에 접근하던 중 카시니는 토성의 전파 자전 주기가 약 10h 45ms 45s ± [89][90]36으로 현저하게 증가했음을 발견했다.카시니 탐사선, 보이저 탐사선, 파이오니어 탐사선의 다양한 측정치를 종합한 결과 토성 회전율(토성 전체의 지시 회전율)은 103235입니다hms.[91]이 행성의 C 고리에 대한 연구는 10m 33s [15][16]38의 자전h 주기를 산출합니다.

2007년 3월, 행성으로부터의 전파 방출의 변화가 토성의 자전 속도와 일치하지 않는 것이 발견되었다.이러한 변화는 토성의 위성 엔셀라두스의 간헐천 활동으로 인해 발생할 수 있다.이 활동에 의해 토성의 궤도로 방출된 수증기는 대전되어 토성의 자기장을 끌어당겨 행성의 회전에 비해 [92][93][94]토성의 회전을 약간 늦춘다.

토성의 명백한 기이한 점은 토성에 알려진 트로이 소행성이 없다는 것이다.이들은 L과5 L로4 명명된 안정된 라그랑지안 지점에서 태양을 공전하는 소행성으로, 궤도를 따라 행성과 60° 각도로 위치해 있습니다.트로이 소행성은 화성, 목성, 천왕성, 해왕성에서 발견되었다.장기 공명을 포함한 궤도 공명 메커니즘이 토성 트로이 [95]목마 실종의 원인으로 여겨지고 있습니다.

자연 위성

토성에는 83개의 알려진 위성이 있으며, 그 중 53개는 정식 [10]이름을 가지고 있다.게다가, 토성의 [96]고리에 지름 40~500미터의 수십에서 수백 개의 위성이 있다는 증거가 있는데, 이 위성은 진짜 위성으로 여겨지지 않는다.가장 큰 위성인 타이탄은 [97]고리를 포함한 토성 궤도 질량의 90% 이상을 차지한다.토성의 두 번째로 큰 위성인 레아는 희박한 [99][100][101]대기와 함께 [98]희박한 고리계를 가지고 있을 것이다.

다른 위성들 중 많은 것들이 작다: 34개는 지름이 10킬로미터 미만이고, 14개는 [102]지름이 10킬로미터에서 50킬로미터 사이이다.전통적으로 토성의 위성 대부분은 그리스 신화에 나오는 타이탄들의 이름을 따서 지어졌다.타이탄은 태양계에서 유일하게 대기를 [103][104]가진 인공위성으로 복잡한 유기화학이 일어난다.그것은 탄화수소 [105][106]호수를 가진 유일한 위성이다.

2013년 6월 6일, IAA-CSIC의 과학자들은 [107]생명체가 존재할 가능성이 있는 타이탄 상층 대기에서 다환 방향족 탄화수소가 검출되었다고 보고했다.2014년 6월 23일, NASA는 타이탄 대기 중 질소가 [108]혜성과 관련된 오르트 구름의 물질에서 나왔다는 강력한 증거를 확보했다고 주장했다.

혜성과 화학적 구성이 비슷해 보이는 토성의 [109]위성 엔셀라두스는 종종 미생물의 [110][111][112][113]잠재적 서식지로 여겨져 왔다.이러한 가능성의 증거로는 엔셀라두스의 방출된 얼음 대부분이 액체 [114][115][116]소금물의 증발에서 나온다는 것을 보여주는 "바다와 같은" 조성을 가진 인공위성의 염분이 풍부한 입자가 포함된다.2015년 카시니가 엔셀라두스의 플룸을 통해 비행한 결과 [117]메타노제네시스로부터 생명체를 유지할 수 있는 대부분의 성분이 발견되었다.

2014년 4월, NASA 과학자들은 2013년 [118]4월 15일 카시니에 의해 촬영된 A 고리 내에서 새로운 달의 시작 가능성을 보고했다.

행성 고리

토성은 아마도 시각적으로 [46]독특하게 만드는 행성 고리 체계로 가장 잘 알려져 있을 것이다.고리는 토성의 적도로부터 바깥쪽으로 6,630에서 120,700 킬로미터까지 뻗어 있으며 두께는 평균 약 20미터(66피트)이다.주로 물 얼음으로 구성되어 있으며, 미량의 톨린 불순물과 약 7%의 비정질 [119]탄소로 코팅되어 있습니다.고리를 구성하는 입자의 크기는 먼지 얼룩에서부터 [120]10미터까지 다양합니다.다른 거대 가스 회사들도 고리 시스템을 가지고 있지만, 토성의 것이 가장 크고 가장 잘 보입니다.

고리의 기원에 관한 두 가지 주요 가설이 있다.한 가지 가설은 고리가 토성의 파괴된 달의 잔재라는 것이다.두 번째 가설은 고리가 토성이 형성된 원래의 성운 물질로부터 남겨진다는 것이다.E 고리의 얼음은 엔셀라두스의 [121][122][123][124]간헐천에서 나온다.고리의 물의 풍부함은 방사상으로 다양하며, 가장 바깥쪽의 고리 A는 얼음물에서 가장 순수합니다.이 풍부성 변화는 유성 [125]충돌로 설명될 수 있다.

주 고리 너머 행성에서 1200만 km 떨어진 곳에 희박한 피비 고리가 있다.그것은 다른 고리에 대해 27°의 각도로 기울어져 있고, 피비처럼 역행하는 [126]방식으로 궤도를 돈다.

판도라와 프로메테우스를 포함한 토성의 위성들 중 일부는 고리를 제한하고 고리가 [127]퍼지는 것을 막는 양치기 달 역할을 한다.Pan과 Atlas는 토성의 고리에 약한 선형 밀도의 파동을 일으켜 질량을 [128]더 확실하게 계산해냈다.

관찰 및 탐사의 역사

토성의 관찰과 탐사는 세 단계로 나눌 수 있다.첫 번째 단계는 현대의 망원경이 발명되기 전의 (육안 등)두 번째 단계는 17세기에 시작되었고, 시간이 지남에 따라 향상된 지구에서 망원경으로 관찰했습니다.세 번째 단계는 우주 탐사선, 궤도 또는 근접 비행에 의한 방문입니다.21세기에는 지구에서 망원경 관측(허블 우주 망원경과 같은 지구 궤도 관측소 포함)을 계속하고 2017년 은퇴할 때까지 토성 주변의 카시니 궤도선에서 망원경 관측을 계속한다.

고대 관측

토성은 선사시대부터 [129]알려져 왔고, 초기 기록된 역사에서는 다양한 신화의 주요 인물이었다.바빌로니아의 천문학자들은 [130]토성의 움직임을 체계적으로 관찰하고 기록했습니다.고대 그리스어로 이 행성은 δααδαδα Painon으로 [131]알려졌으며, 로마 시대에는 "토성의 별"[132]로 알려졌습니다.고대 로마 신화에서 파이논 행성은 이 농경신에게 신성시되었으며, 이 행성에서 현대적 이름을 [133]따왔다.로마인들은 새턴노스를 그리스 신 크로노스와 동등하다고 여겼다; 현대 그리스어로, 이 행성은 크로노스라는 이름을 유지하고 있다.[134]

그리스 과학자 프톨레마이오스는 토성의 궤도에 대한 그의 계산은 토성이 [135]반대편에 있을 때 그가 한 관찰에 기초했다.힌두 점성술에는 나바그라하스로 알려진 9개의 점성술 개체가 있다.토성은 "샤니"로 알려져 있고 인생에서 [133][135]행해진 선과 악행을 바탕으로 모두를 판단한다.고대 중국과 일본의 문화는 토성을 "지구별"로 지정했다.이것은 전통적으로 자연 [136][137][138]원소를 분류하는 데 사용되었던 다섯 가지 원소를 기반으로 했습니다.

고대 히브리어로 토성은 샤바타이라고 [139]불린다.그것의 천사는 카시엘이다.지성 또는 유익한 정신은 '아그젤'[140]이고, 어두운 정신(데몬)은 '자젤'[140][141][142]이다.자젤은 솔로모닉 마법에서 "사랑 마법에 효과적"[143][144]인 위대한 천사로 묘사되어 왔다.오스만 터키어, 우르두어, 말레이어로 자젤의 이름은 아랍어(아랍어: حل,, 로마자: Zuhal)[141]에서 유래한 '주할'이다.

유럽의 관측(17~19세기)

토성의 고리는 분해하기 위해 적어도 지름[145] 15mm의 망원경이 필요했고, 따라서 크리스티안 호이겐스가 1655년에 고리를 보고 1659년에 이것에 대해 출판할 때까지 존재한다고 알려져 있지 않았다.갈릴레오는 1610년 [146][147]원시 망원경으로 토성이 토성의 [148][149]측면에 있는 두 개의 달처럼 둥글지 않게 보이는 것을 잘못 생각했다.호이겐스가 더 큰 망원경 배율을 사용한 후에야 이 개념이 반박되었고, 고리는 처음으로 실제로 목격되었습니다.호이겐스는 또한 토성의 위성 타이탄을 발견했고, 지오반니 도메니코 카시니는 나중에 다른 4개의 위성을 발견했습니다.이아페토스, 레아, 테티스, 디오네.1675년, 카시니는 현재 카시니 [150]분할로 알려진 틈을 발견했다.

1789년 윌리엄 허셜이 미마스와 엔셀라두스라는 두 개의 위성을 추가로 발견하기까지 더 이상의 의미 있는 발견은 없었다.타이탄과 공명하는 불규칙한 모양의 위성 하이페리온은 1848년 영국 팀에 [151]의해 발견되었다.

1899년 윌리엄 헨리 피커링은 토성과 동시에 회전하지 않는 매우 불규칙한 위성 피비를 발견했다.[151]피비는 그러한 위성이 발견된 첫 번째 위성이며 토성을 역행 궤도로 도는 데는 1년 이상이 걸린다.20세기 초 타이탄에 대한 연구는 1944년 타이탄이 두꺼운 대기를 가지고 있다는 것을 확인하게 했습니다. 이것은 태양계의 [152]위성들 중 독특한 특징입니다.

최신 NASA 및 ESA 탐사선

파이오니어 11 플라이바이

파이어니어 11호는 1979년 9월 토성이 구름 꼭대기에서 2만 km 이내를 통과했을 때 처음으로 토성을 통과했다.분해능이 너무 낮아서 표면의 디테일을 식별하지 못했지만, 이 행성과 그 위성들 중 몇 개를 촬영했다.이 우주선은 또한 토성의 고리를 연구했는데, 얇은 F-링과 고리의 어두운 틈이 높은 위상각(태양 방향)에서 볼 때 밝다는 사실을 밝혀냈는데, 이는 이 고리들이 미세한 빛 산란 물질을 포함하고 있다는 것을 의미한다.게다가 파이오니아 11호는 [153]타이탄의 온도를 측정했다.

보이저 플라이바이

1980년 11월, 보이저 1호는 토성계를 방문했다.그것은 행성, 고리와 위성의 첫 고해상도 이미지를 되돌려 보냈다.다양한 달의 표면적 특징이 처음으로 목격되었다.보이저 1호는 타이탄을 근접 비행하면서 달의 대기에 대한 지식을 늘렸다.타이탄의 대기는 가시적인 파장으로 투과할 수 없다는 것을 증명했다. 따라서 표면의 세부 사항은 보이지 않았다.그 비행체는 태양계 [154]비행기에서 우주선의 궤적을 바꾸었다.

거의 1년 후인 1981년 8월, 보이저 2호는 토성계에 대한 연구를 계속했다.대기와 고리의 변화에 대한 증거뿐만 아니라 토성의 위성들을 더 가까이서 촬영한 사진들이 입수되었다.불행하게도, 근접 비행하는 동안, 탐사선의 회전식 카메라 플랫폼이 며칠간 고착되었고 계획된 몇 가지 영상이 손실되었다.토성의 중력은 우주선의 궤적을 [154]천왕성으로 향하게 하기 위해 사용되었다.

탐사선은 행성의 고리 근처 또는 내부에서 궤도를 도는 몇 개의 새로운 위성과 작은 맥스웰 갭(C 고리 내부의 간격)과 킬러 갭(A 고리 내의 폭 42km의 간격)을 발견하여 확인하였다.

카시니호이겐스 우주선

카시니호Huygens 우주 탐사선은 2004년 7월 1일 토성 궤도에 진입했다.2004년 6월에는 고해상도 이미지와 데이터를 전송하면서 Phoebe를 근접 통과시켰습니다.토성의 가장 큰 위성인 타이탄에 대한 카시니호의 근접 비행은 수많은 섬과 산이 있는 큰 호수와 해안선의 레이더 이미지를 포착했다.이 궤도선은 2004년 12월 25일 호이겐스 탐사선을 발사하기 전에 두 번의 타이탄 비행을 완료했다.호이겐스는 2005년 [155]1월 14일 타이탄 표면에 착륙했다.

2005년 초부터 과학자들은 토성의 번개를 추적하기 위해 카시니호를 이용했다.번개의 힘은 지구 [156]번개의 약 1,000배이다.

2006년, NASA는 카시니호가 토성의 위성 엔셀라두스의 간헐천에서 분출하는 표면 아래 수십 미터 이하의 액체 저수지에 대한 증거를 발견했다고 보고했다.이 얼음 입자들의 제트는 달의 남극 [158]지역에 있는 구멍에서 토성 궤도로 방출된다.엔셀라두스에서 [157]100개 이상의 간헐천이 확인되었다.2011년 5월, NASA 과학자들은 엔셀라두스가 "우리가 알고 있는 태양계에서 지구 너머로 생명체가 살 수 있는 가장 살기 좋은 곳으로 떠오르고 있다"[159][160]고 보고했다.

카시니 사진은 토성의 밝은 주 고리 바깥과 G와 E 고리 안에 이전에 발견되지 않은 행성 고리가 있다는 것을 밝혀냈다.이 고리의 근원은 야누스와 에피메테우스 [161]앞바다에 있는 유성체의 충돌로 추측된다.2006년 7월 타이탄 북극 근처의 탄화수소 호수의 이미지가 반환되었고, 2007년 1월에 그 존재가 확인되었다.2007년 3월, 북극 근처에서 탄화수소 바다가 발견되었는데, 그 중 가장 큰 바다는 카스피해의 [162]거의 크기이다.2006년 10월, 탐사선은 토성의 [163]남극에서 지름 8,000 킬로미터의 사이클론 같은 폭풍과 눈벽을 감지했다.

2004년부터 2009년 11월 2일까지, 탐사선은 8개의 새로운 [164]위성을 발견하고 확인했다.2013년 4월 카시니는 530km/h(330mph)[165] 이상의 바람과 함께 지구상에서 발견된 것보다 20배 더 큰 허리케인의 이미지를 보냈다.2017년 9월 15일, 카시니-후이겐스 우주선은 토성과 토성의 내부 [166][167]고리 사이의 틈새를 통과하는 "그랜드 피날레" 임무를 수행했다.카시니호의 대기권 진입으로 임무가 종료되었다.

장래의 미션을 생각할 수 있는 미션

토성의 계속적인 탐사는 현재 진행 중인 뉴 프런티어 임무 프로그램의 일환으로 NASA에게 여전히 실행 가능한 선택 사항으로 여겨지고 있다.NASA는 이전에 토성 대기권 진입 탐사선을 포함한 토성 임무와 토성의 위성 타이탄과 엔셀라두스에서의 생명체 거주 가능성 및 발견 가능성에 대한 조사를 위해 드래곤플라이에 의해 [168][169]제출될 계획을 요청했었다.

관찰

토성은 지구에서 육안으로 쉽게 볼 수 있는 5개의 행성 중 가장 멀리 떨어져 있으며, 나머지 4개는 수성, 금성, 화성, 목성이다.토성은 밤하늘에서 육안으로 밝고 노란 빛의 점으로 보입니다.토성의 평균 겉보기 등급은 0.46이고 표준 편차는 0.34입니다.[19]대부분의 매그니튜드 변동은 태양과 지구에 대한 고리 시스템의 기울기에 기인한다.가장 밝은 등급인 -0.55는 고리의 평면이 가장 높게 기울어진 시간 부근에 발생하며, 가장 약한 등급인 1.17은 가장 덜 [19]기울어진 시간 부근에 발생한다.행성이 황도대의 배경 별자리에 대한 황도의 전체 회로를 완성하는 데는 약 29.5년이 걸린다.대부분의 사람들은 명확한 분해능이 존재하는 [46][145]토성 고리의 이미지를 얻기 위해 최소 30배 확대하는 광학 보조기(매우 큰 쌍안경 또는 작은 망원경)를 필요로 할 것이다.지구가 토성년 마다 두 번 발생하는 고리 평면을 통과할 때, 고리는 너무 얇기 때문에 시야에서 잠시 사라집니다.이러한 "사라짐"은 2025년에 일어날 것이지만,[170] 토성은 관측하기에는 태양에 너무 가까이 있을 것이다.

토성과 토성의 고리는 행성이 180°의 연장선상에 있을 때 또는 그와 반대되는 위치에 있을 때 가장 잘 보이며, 따라서 하늘에서 태양 반대편에 나타납니다.토성과의 대립은 매년 약 378일에 한 번씩 발생하며, 그 결과 행성이 가장 밝게 나타납니다.지구와 토성은 둘 다 태양으로부터의 거리가 시간에 따라 변하기 때문에 토성의 밝기는 반대편에서 반대편으로 변화합니다.토성은 또한 고리가 더 잘 보이도록 각을 졌을 때 더 밝게 보입니다.예를 들어, 2002년 12월 17일 반대편에서는 2003년 말 [171]토성이 지구와 태양에 더 가까웠음에도 불구하고 고리의 방향은 지구에 [171]비해 양호했기 때문에 토성이 가장 밝게 나타났다.

때때로 토성은 달에 의해 가려진다.태양계의 모든 행성들과 마찬가지로, 토성의 엄폐는 "계절"에 일어납니다.토성 엄폐는 약 12개월 동안 매달 이루어지며, 그 후 약 5년 동안 그러한 활동이 등록되지 않을 것이다.달의 궤도는 토성 궤도에 비해 몇 도 기울어져 있기 때문에, 엄폐는 토성이 두 평면이 교차하는 하늘의 지점 중 하나 근처에 있을 때만 발생합니다(토성 연도의 길이와 달 궤도의 18.6년 결절 세차 주기 모두 주기성에 [172]영향을 미칩니다).

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

메모들

레퍼런스

- ^ Walter, Elizabeth (21 April 2003). Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53106-1.

- ^ "Saturnian". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (가입 또는 참여기관 회원가입 필요)

- ^ "Enabling Exploration with Small Radioisotope Power Systems" (PDF). NASA. September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Müller; et al. (2010). "Azimuthal plasma flow in the Kronian magnetosphere". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (A8): A08203. Bibcode:2010JGRA..115.8203M. doi:10.1029/2009ja015122.

- ^ "Cronian". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (가입 또는 참여기관 회원가입 필요)

- ^ a b Seligman, Courtney. "Rotation Period and Day Length". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Simon, J.L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). "Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 663–683. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^ Souami, D.; Souchay, J. (July 2012). "The solar system's invariable plane". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: 11. Bibcode:2012A&A...543A.133S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219011. A133.

- ^ "HORIZONS Planet-center Batch call for November 2032 Perihelion". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov (Perihelion for Saturn's planet-center (699) occurs on 2032-Nov-29 at 9.0149170au during a rdot flip from negative to positive). NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Solar System Dynamics – Planetary Satellite Discovery Circumstances". NASA. 15 November 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Williams, David R. (23 December 2016). "Saturn Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ "By the Numbers – Saturn". NASA Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "NASA: Solar System Exploration: Planets: Saturn: Facts & Figures". Solarsystem.nasa.gov. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Fortney, J.J.; Helled, R.; Nettlemann, N.; Stevenson, D.J.; Marley, M.S.; Hubbard, W.B.; Iess, L. (6 December 2018). "The Interior of Saturn". In Baines, K.H.; Flasar, F.M.; Krupp, N.; Stallard, T. (eds.). Saturn in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–68. ISBN 978-1-108-68393-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ a b McCartney, Gretchen; Wendel, JoAnna (18 January 2019). "Scientists Finally Know What Time It Is on Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ a b Mankovich, Christopher; et al. (17 January 2019). "Cassini Ring Seismology as a Probe of Saturn's Interior. I. Rigid Rotation". The Astrophysical Journal. 871 (1): 1. arXiv:1805.10286. Bibcode:2019ApJ...871....1M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaf798. S2CID 67840660.

- ^ Hanel, R.A.; et al. (1983). "Albedo, internal heat flux, and energy balance of Saturn". Icarus. 53 (2): 262–285. Bibcode:1983Icar...53..262H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(83)90147-1.

- ^ Mallama, Anthony; Krobusek, Bruce; Pavlov, Hristo (2017). "Comprehensive wide-band magnitudes and albedos for the planets, with applications to exo-planets and Planet Nine". Icarus. 282: 19–33. arXiv:1609.05048. Bibcode:2017Icar..282...19M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.023. S2CID 119307693.

- ^ a b c d Mallama, A.; Hilton, J.L. (2018). "Computing Apparent Planetary Magnitudes for The Astronomical Almanac". Astronomy and Computing. 25: 10–24. arXiv:1808.01973. Bibcode:2018A&C....25...10M. doi:10.1016/j.ascom.2018.08.002. S2CID 69912809.

- ^ a b "Saturn's Temperature Ranges". Sciencing. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "The Planet Saturn". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Knecht, Robin (24 October 2005). "On The Atmospheres Of Different Planets" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ Brainerd, Jerome James (24 November 2004). "Characteristics of Saturn". The Astrophysics Spectator. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "General Information About Saturn". Scienceray. 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Brainerd, Jerome James (6 October 2004). "Solar System Planets Compared to Earth". The Astrophysics Spectator. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Dunbar, Brian (29 November 2007). "NASA – Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008). "Mass of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Russell, C. T.; et al. (1997). "Saturn: Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere". Science. 207 (4429): 407–10. Bibcode:1980Sci...207..407S. doi:10.1126/science.207.4429.407. PMID 17833549. S2CID 41621423. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ^ "The Planets ('Giants')". Science Channel. 8 June 2004.

- ^ Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew; Alexandersen, Mike; Petit, Jean-Marc (May 2022). "Discovery of the Closest Saturnian Irregular Moon, S/2019 S 1, and Implications for the Direct/Retrograde Satellite Ratio". The Astronomical Journal. 3 (5): 5. Bibcode:2022PSJ.....3..107A. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac64a2. S2CID 248771843. 107.

- ^ Munsell, Kirk (6 April 2005). "The Story of Saturn". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory; California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 16 August 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ a b Jones, Alexander (1999). Astronomical papyri from Oxyrhynchus. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780871692337. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Falk, Michael (June 1999), "Astronomical Names for the Days of the Week", Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 93: 122–133, Bibcode:1999JRASC..93..122F, archived from the original on 25 February 2021, retrieved 18 November 2020

- ^ Melosh, H. Jay (2011). Planetary Surface Processes. Cambridge Planetary Science. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-51418-7. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Gregersen, Erik, ed. (2010). Outer Solar System: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and the Dwarf Planets. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 119. ISBN 978-1615300143. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Saturn – The Most Beautiful Planet of our solar system". Preserve Articles. 23 January 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Williams, David R. (16 November 2004). "Jupiter Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ a b Fortney, Jonathan J.; Nettelmann, Nadine (May 2010). "The Interior Structure, Composition, and Evolution of Giant Planets". Space Science Reviews. 152 (1–4): 423–447. arXiv:0912.0533. Bibcode:2010SSRv..152..423F. doi:10.1007/s11214-009-9582-x. S2CID 49570672.

- ^ a b c Guillot, Tristan; et al. (2009). "Saturn's Exploration Beyond Cassini-Huygens". In Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (eds.). Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. p. 745. arXiv:0912.2020. Bibcode:2009sfch.book..745G. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_23. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9. S2CID 37928810.

- ^ "Saturn - The interior Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Fortney, Jonathan J. (2004). "Looking into the Giant Planets". Science. 305 (5689): 1414–1415. doi:10.1126/science.1101352. PMID 15353790. S2CID 26353405. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Saumon, D.; Guillot, T. (July 2004). "Shock Compression of Deuterium and the Interiors of Jupiter and Saturn". The Astrophysical Journal. 609 (2): 1170–1180. arXiv:astro-ph/0403393. Bibcode:2004ApJ...609.1170S. doi:10.1086/421257. S2CID 119325899.

- ^ "Saturn". BBC. 2000. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Mankovich, Christopher R.; Fuller, Jim (2021). "A diffuse core in Saturn revealed by ring seismology". Nature Astronomy. 5 (11): 1103–1109. arXiv:2104.13385. Bibcode:2021NatAs...5.1103M. doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01448-3. S2CID 233423431. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Faure, Gunter; Mensing, Teresa M. (2007). Introduction to planetary science: the geological perspective. Springer. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-4020-5233-0. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Saturn". National Maritime Museum. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ "Structure of Saturn's Interior". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ de Pater, Imke; Lissauer, Jack J. (2010). Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0-521-85371-2. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "NASA – Saturn". NASA. 2004. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (9 October 2013). "Diamond Rain May Fill Skies of Jupiter and Saturn". Space.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Kaplan, Sarah (25 August 2017). "It rains solid diamonds on Uranus and Neptune". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Saturn". Universe Guide. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ^ Guillot, Tristan (1999). "Interiors of Giant Planets Inside and Outside the Solar System". Science. 286 (5437): 72–77. Bibcode:1999Sci...286...72G. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.72. PMID 10506563. S2CID 6907359.

- ^ Courtin, R.; et al. (1967). "The Composition of Saturn's Atmosphere at Temperate Northern Latitudes from Voyager IRIS spectra". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 15: 831. Bibcode:1983BAAS...15..831C.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (22 January 2009). "Atmosphere of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b Guerlet, S.; Fouchet, T.; Bézard, B. (November 2008). Charbonnel, C.; Combes, F.; Samadi, R. (eds.). "Ethane, acetylene and propane distribution in Saturn's stratosphere from Cassini/CIRS limb observations". SF2A-2008: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the French Society of Astronomy and Astrophysics: 405. Bibcode:2008sf2a.conf..405G.

- ^ Martinez, Carolina (5 September 2005). "Cassini Discovers Saturn's Dynamic Clouds Run Deep". NASA. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ^ Orton, Glenn S. (September 2009). "Ground-Based Observational Support for Spacecraft Exploration of the Outer Planets". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 105 (2–4): 143–152. Bibcode:2009EM&P..105..143O. doi:10.1007/s11038-009-9295-x. S2CID 121930171.

- ^ Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (2009). Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (eds.). Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. Springer. p. 162. Bibcode:2009sfch.book.....D. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Pérez-Hoyos, S.; Sánchez-Laveg, A.; French, R. G.; J. F., Rojas (2005). "Saturn's cloud structure and temporal evolution from ten years of Hubble Space Telescope images (1994–2003)". Icarus. 176 (1): 155–174. Bibcode:2005Icar..176..155P. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.01.014.

- ^ Kidger, Mark (1992). "The 1990 Great White Spot of Saturn". In Moore, Patrick (ed.). 1993 Yearbook of Astronomy. 1993 Yearbook of Astronomy. London: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 176–215. Bibcode:1992ybas.conf.....M.

- ^ Hamilton, Calvin J. (1997). "Voyager Saturn Science Summary". Solarviews. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ Watanabe, Susan (27 March 2007). "Saturn's Strange Hexagon". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Warm Polar Vortex on Saturn". Merrillville Community Planetarium. 2007. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ Godfrey, D. A. (1988). "A hexagonal feature around Saturn's North Pole". Icarus. 76 (2): 335. Bibcode:1988Icar...76..335G. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90075-9.

- ^ Sanchez-Lavega, A.; et al. (1993). "Ground-based observations of Saturn's north polar SPOT and hexagon". Science. 260 (5106): 329–32. Bibcode:1993Sci...260..329S. doi:10.1126/science.260.5106.329. PMID 17838249. S2CID 45574015.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (6 August 2014). "Storm Chasing on Saturn". New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "New images show Saturn's weird hexagon cloud". NBC News. 12 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Godfrey, D. A. (9 March 1990). "The Rotation Period of Saturn's Polar Hexagon". Science. 247 (4947): 1206–1208. Bibcode:1990Sci...247.1206G. doi:10.1126/science.247.4947.1206. PMID 17809277. S2CID 19965347.

- ^ Baines, Kevin H.; et al. (December 2009). "Saturn's north polar cyclone and hexagon at depth revealed by Cassini/VIMS". Planetary and Space Science. 57 (14–15): 1671–1681. Bibcode:2009P&SS...57.1671B. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2009.06.026.

- ^ Ball, Philip (19 May 2006). "Geometric whirlpools revealed". Nature. doi:10.1038/news060515-17. S2CID 129016856. 행성 대기의 소용돌이 소용돌이 중심에 나타나는 기괴한 기하학적 모양은 물 한 바가지로 간단한 실험을 통해 설명될 수 있지만, 토성의 패턴과 이것을 연관짓는 것은 결코 확실치 않다.

- ^ Aguiar, Ana C. Barbosa; et al. (April 2010). "A laboratory model of Saturn's North Polar Hexagon". Icarus. 206 (2): 755–763. Bibcode:2010Icar..206..755B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.10.022. 액체 용액에서 회전하는 원반을 실험하는 것은 토성과 비슷한 안정적인 육각형 패턴 주위에 소용돌이를 형성한다.

- ^ Sánchez-Lavega, A.; et al. (8 October 2002). "Hubble Space Telescope Observations of the Atmospheric Dynamics in Saturn's South Pole from 1997 to 2002". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 34: 857. Bibcode:2002DPS....34.1307S. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ "NASA catalog page for image PIA09187". NASA Planetary Photojournal. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ "Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn". BBC News. 10 November 2006. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ "NASA Sees into the Eye of a Monster Storm on Saturn". NASA. 9 November 2006. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ^ a b Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (13 November 2006). "A Hurricane Over the South Pole of Saturn". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ "Cassini Image Shows Saturn Draped in a String of Pearls" (Press release). Carolina Martinez, NASA. 10 November 2006. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Hubble sees a flickering light display on Saturn". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ a b McDermott, Matthew (2000). "Saturn: Atmosphere and Magnetosphere". Thinkquest Internet Challenge. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "Voyager – Saturn's Magnetosphere". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (14 December 2010). "Hot Plasma Explosions Inflate Saturn's Magnetic Field". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Russell, Randy (3 June 2003). "Saturn Magnetosphere Overview". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (26 January 2009). "Orbit of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Michtchenko, T. A.; Ferraz-Mello, S. (February 2001). "Modeling the 5 : 2 Mean-Motion Resonance in the Jupiter-Saturn Planetary System". Icarus. 149 (2): 357–374. Bibcode:2001Icar..149..357M. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6539.

- ^ Jean Meeus, Astronomical Algorithms (Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, 1998). Average of the nine extremes on p 273. All are within 0.02 AU of the averages.

- ^ Kaiser, M. L.; Desch, M. D.; Warwick, J. W.; Pearce, J. B. (1980). "Voyager Detection of Nonthermal Radio Emission from Saturn". Science. 209 (4462): 1238–40. Bibcode:1980Sci...209.1238K. doi:10.1126/science.209.4462.1238. hdl:2060/19800013712. PMID 17811197. S2CID 44313317.

- ^ Benton, Julius (2006). Saturn and how to observe it. Astronomers' observing guides (11th ed.). Springer Science & Business. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-85233-887-9. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Scientists Find That Saturn's Rotation Period is a Puzzle". NASA. 28 June 2004. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (30 June 2008). "Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Anderson, J. D.; Schubert, G. (2007). "Saturn's gravitational field, internal rotation and interior structure" (PDF). Science. 317 (5843): 1384–1387. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1384A. doi:10.1126/science.1144835. PMID 17823351. S2CID 19579769. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Enceladus Geysers Mask the Length of Saturn's Day" (Press release). NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 22 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Gurnett, D. A.; et al. (2007). "The Variable Rotation Period of the Inner Region of Saturn's Plasma Disc" (PDF). Science. 316 (5823): 442–5. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..442G. doi:10.1126/science.1138562. PMID 17379775. S2CID 46011210. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2020.

- ^ Bagenal, F. (2007). "A New Spin on Saturn's Rotation". Science. 316 (5823): 380–1. doi:10.1126/science.1142329. PMID 17446379. S2CID 118878929.

- ^ Hou, X. Y.; et al. (January 2014). "Saturn Trojans: a dynamical point of view". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 437 (2): 1420–1433. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.437.1420H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1974.

- ^ Tiscareno, Matthew (17 July 2013). "The population of propellers in Saturn's A Ring". The Astronomical Journal. 135 (3): 1083–1091. arXiv:0710.4547. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1083T. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/1083. S2CID 28620198.

- ^ Brunier, Serge (2005). Solar System Voyage. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-521-80724-1.

- ^ Jones, G. H.; et al. (7 March 2008). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea" (PDF). Science. 319 (5868): 1380–1384. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J. doi:10.1126/science.1151524. PMID 18323452. S2CID 206509814. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2018.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (26 November 2010). "Tenuous Oxygen Atmosphere Found Around Saturn's Moon Rhea". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ NASA (30 November 2010). "Thin air: Oxygen atmosphere found on Saturn's moon Rhea". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Ryan, Clare (26 November 2010). "Cassini reveals oxygen atmosphere of Saturn′s moon Rhea". UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Saturn's Known Satellites". Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Cassini Finds Hydrocarbon Rains May Fill Titan Lakes". ScienceDaily. 30 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Voyager – Titan". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Evidence of hydrocarbon lakes on Titan". NBC News. Associated Press. 25 July 2006. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Hydrocarbon lake finally confirmed on Titan". Cosmos Magazine. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ López-Puertas, Manuel (6 June 2013). "PAH's in Titan's Upper Atmosphere". CSIC. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Dyches, Preston; et al. (23 June 2014). "Titan's Building Blocks Might Pre-date Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Battersby, Stephen (26 March 2008). "Saturn's moon Enceladus surprisingly comet-like". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ NASA (21 April 2008). "Could There Be Life On Saturn's Moon Enceladus?". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis (24 June 2009). "Hunt for Life on Saturnian Moon Heats Up". Wired Science. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Spotts, Peter N. (28 September 2005). "Life beyond Earth? Potential solar system sites pop up". USA Today. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Pili, Unofre (9 September 2009). "Enceladus: Saturn′s Moon, Has Liquid Ocean of Water". Scienceray. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Strongest evidence yet indicates Enceladus hiding saltwater ocean". Physorg. 22 June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Kaufman, Marc (22 June 2011). "Saturn′s moon Enceladus shows evidence of an ocean beneath its surface". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Greicius, Tony; et al. (22 June 2011). "Cassini Captures Ocean-Like Spray at Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Chou, Felicia; Dyches, Preston; Weaver, Donna; Villard, Ray (13 April 2017). "NASA Missions Provide New Insights into 'Ocean Worlds' in Our Solar System". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Platt, Jane; et al. (14 April 2014). "NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Poulet F.; et al. (2002). "The Composition of Saturn's Rings". Icarus. 160 (2): 350. Bibcode:2002Icar..160..350P. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6967. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Porco, Carolyn. "Questions about Saturn's rings". CICLOPS web site. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Spahn, F.; et al. (2006). "Cassini Dust Measurements at Enceladus and Implications for the Origin of the E Ring" (PDF). Science. 311 (5766): 1416–1418. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1416S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.6748. doi:10.1126/science.1121375. PMID 16527969. S2CID 33554377. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Finger-like Ring Structures In Saturn's E Ring Produced By Enceladus' Geysers". CICLOPS web site. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Icy Tendrils Reaching into Saturn Ring Traced to Their Source". CICLOPS web site (Press release). 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "The Real Lord of the Rings". Science@NASA. 12 February 2002. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Esposito, Larry W.; et al. (February 2005). "Ultraviolet Imaging Spectroscopy Shows an Active Saturnian System" (PDF). Science. 307 (5713): 1251–1255. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1251E. doi:10.1126/science.1105606. PMID 15604361. S2CID 19586373. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2019.

- ^ Cowen, Rob (7 November 1999). "Largest known planetary ring discovered". Science News. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Russell, Randy (7 June 2004). "Saturn Moons and Rings". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (3 March 2005). "NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Continues Making New Discoveries". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Observing Saturn". National Maritime Museum. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ Sachs, A. (2 May 1974). "Babylonian Observational Astronomy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 276 (1257): 43–50. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...43S. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0008. JSTOR 74273. S2CID 121539390.

- ^ Φαίνων. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum.

- ^ a b "Starry Night Times". Imaginova Corp. 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ "Greek Names of the Planets". 25 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

The Greek name of the planet Saturn is Kronos. The Titan Cronus was the father of Zeus, while Saturn was the Roman God of agriculture.

See also the Greek article about the planet. - ^ a b Corporation, Bonnier (April 1893). "Popular Miscellany – Superstitions about Saturn". The Popular Science Monthly: 862. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ De Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1912). Religion in China: universism. a key to the study of Taoism and Confucianism. American lectures on the history of religions. Vol. 10. G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 300. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ Crump, Thomas (1992). The Japanese numbers game: the use and understanding of numbers in modern Japan. Nissan Institute/Routledge Japanese studies series. Routledge. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0415056090.

- ^ Hulbert, Homer Bezaleel (1909). The passing of Korea. Doubleday, Page & company. p. 426. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ Cessna, Abby (15 November 2009). "When Was Saturn Discovered?". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ a b "The Magus, Book I: The Celestial Intelligencer: Chapter XXVIII". Sacred-Text.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Saturn in Mythology". CrystalLinks.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Beyer, Catherine (8 March 2017). "Planetary Spirit Sigils – 01 Spirit of Saturn". ThoughtCo.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Meaning and Origin of: Zazel". FamilyEducation.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

Latin: Angel summoned for love invocations

- ^ "Angelic Beings". Hafapea.com. 1998. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

a Solomonic angel of love rituals

- ^ a b Eastman, Jack (1998). "Saturn in Binoculars". The Denver Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Chan, Gary (2000). "Saturn: History Timeline". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008). "History of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (7 July 2008). "Interesting Facts About Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (27 November 2009). "Who Discovered Saturn?". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Micek, Catherine. "Saturn: History of Discoveries". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ a b Barton, Samuel G. (April 1946). "The names of the satellites". Popular Astronomy. Vol. 54. pp. 122–130. Bibcode:1946PA.....54..122B.

- ^ Kuiper, Gerard P. (November 1944). "Titan: a Satellite with an Atmosphere". Astrophysical Journal. 100: 378–388. Bibcode:1944ApJ...100..378K. doi:10.1086/144679.

- ^ "The Pioneer 10 & 11 Spacecraft". Mission Descriptions. Archived from the original on 30 January 2006. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Missions to Saturn". The Planetary Society. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Lebreton, Jean-Pierre; et al. (December 2005). "An overview of the descent and landing of the Huygens probe on Titan". Nature. 438 (7069): 758–764. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..758L. doi:10.1038/nature04347. PMID 16319826. S2CID 4355742.

- ^ "Astronomers Find Giant Lightning Storm At Saturn". ScienceDaily LLC. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ a b Dyches, Preston; et al. (28 July 2014). "Cassini Spacecraft Reveals 101 Geysers and More on Icy Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Pence, Michael (9 March 2006). "NASA's Cassini Discovers Potential Liquid Water on Enceladus". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Lovett, Richard A. (31 May 2011). "Enceladus named sweetest spot for alien life". Nature: news.2011.337. doi:10.1038/news.2011.337. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Kazan, Casey (2 June 2011). "Saturn's Enceladus Moves to Top of "Most-Likely-to-Have-Life" List". The Daily Galaxy. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Shiga, David (20 September 2007). "Faint new ring discovered around Saturn". NewScientist.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (14 March 2007). "Probe reveals seas on Saturn moon". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (10 November 2006). "Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ "Mission overview – introduction". Cassini Solstice Mission. NASA / JPL. 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "Massive storm at Saturn's north pole". 3 News NZ. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Dyches, Preston (15 September 2017). "NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Ends Its Historic Exploration of Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (14 September 2017). "Cassini Vanishes Into Saturn, Its Mission Celebrated and Mourned". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (8 January 2016). "NASA Expands Frontiers of Next New Frontiers Competition". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ April 2017, Nola Taylor Redd 25 (25 April 2017). "'Dragonfly' Drone Could Explore Saturn Moon Titan". Space.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Saturn's Rings Edge-On". Classical Astronomy. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ a b Schmude Jr., Richard W. (Winter 2003). "Saturn in 2002–03". Georgia Journal of Science. 61 (4). ISSN 0147-9369. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Tanya Hill; et al. (9 May 2014). "Bright Saturn will blink out across Australia – for an hour, anyway". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

Further reading

- Alexander, Arthur Francis O'Donel (1980) [1962]. The Planet Saturn – A History of Observation, Theory and Discovery. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-23927-9.

- Gore, Rick (July 1981). "Voyager 1 at Saturn: Riddles of the Rings". National Geographic. Vol. 160, no. 1. pp. 3–31. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Lovett, L.; et al. (2006). Saturn: A New View. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3090-2.

- Karttunen, H.; et al. (2007). Fundamental Astronomy (5th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-34143-7.

- Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; et al. (2007). "Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 98 (3): 155–180. Bibcode:2007CeMDA..98..155S. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y.

- de Pater, Imke; Lissauer, Jack J. (2015). Planetary Sciences (2nd updated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-521-85371-2.

External links

- Saturn overview by NASA's Science Mission Directorate

- Saturn fact sheet at the NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive

- Saturnian System terminology by the IAU Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature

- Cassini-Huygens legacy website by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Saturn at SolarViews.com

- Interactive 3D gravity simulation of the Cronian system Archived 17 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine