Centipede game

In game theory, the centipede game, first introduced by Robert Rosenthal in 1981, is an extensive form game in which two players take turns choosing either to take a slightly larger share of an increasing pot, or to pass the pot to the other player. The payoffs are arranged so that if one passes the pot to one's opponent and the opponent takes the pot on the next round, one receives slightly less than if one had taken the pot on this round, but after an additional switch the potential payoff will be higher. Therefore, although at each round a player has an incentive to take the pot, it would be better for them to wait. Although the traditional centipede game had a limit of 100 rounds (hence the name), any game with this structure but a different number of rounds is called a centipede game.

The unique subgame perfect equilibrium (and every Nash equilibrium) of these games results in the first player taking the pot on the first round of the game; however, in empirical tests, relatively few players do so, and as a result, achieve a higher payoff than in the subgame perfect and Nash equilibria. These results are taken to show that subgame perfect equilibria and Nash equilibria fail to predict human play in some circumstances. The Centipede game is commonly used in introductory game theory courses and texts to highlight the concept of backward induction and the iterated elimination of dominated strategies, which show a standard way of providing a solution to the game.

Play

One possible version of a centipede game could be played as follows:

Consider two players: Alice and Bob. Alice moves first. At the start of the game, Alice has two piles of coins in front of her: one pile contains 4 coins and the other pile contains 1 coin. Each player has two moves available: either "take" the larger pile of coins and give the smaller pile to the other player or "push" both piles across the table to the other player. Each time the piles of coins pass across the table, the quantity of coins in each pile doubles. For example, assume that Alice chooses to "push" the piles on her first move, handing the piles of 1 and 4 coins over to Bob, doubling them to 2 and 8. Bob could now use his first move to either "take" the pile of 8 coins and give 2 coins to Alice, or he can "push" the two piles back across the table again to Alice, again increasing the size of the piles to 4 and 16 coins. The game continues for a fixed number of rounds or until a player decides to end the game by pocketing a pile of coins.

The addition of coins is taken to be an externality, as it is not contributed by either player.

Formal Definition

The centipede game may be written as where and . Players and alternate, starting with player , and may on each turn play a move from with a maximum of rounds. The game terminates when is played for the first time, otherwise upon moves, if is never played.

Suppose the game ends on round with player making the final move. Then the outcome of the game is defined as follows:

- If played , then gains coins and gains .

- If played , then gains coins and gains .

자, { I p,은(는) 다른 선수를 가리킨다.

평형해석 및 역유도

표준 게임 이론 도구는 첫 번째 선수가 동전 더미를 스스로 가져가면서 1라운드에서 이탈할 것으로 예측하고 있다. 지네 게임에서 순수 전략은 일련의 액션(이러한 선택 포인트 중 일부는 결코 도달하지 못할 수도 있지만, 게임의 각 선택 포인트마다 하나씩)으로 구성되며, 혼합 전략은 가능한 순수 전략에 대한 확률 분포다. 지네 게임의 순수 전략인 나시 평준화와 무한히 혼합된 전략인 내시 평준화가 있다. 그러나 서브게임 퍼펙트 평형(Nash 평형 개념에 대한 대중적인 세련됨)은 단 하나뿐이다.

독특한 서브게임 퍼펙트 평형에서 각 플레이어가 기회 있을 때마다 탈주를 선택한다. 이는 물론 1단계에서 탈당을 의미한다. 그러나 나시 평형주의 경우 최초 선택 기회(첫 번째 선수가 즉시 결함을 당한 이후 도달하지 못하더라도) 이후에 취할 조치는 협조적일 수 있다.

첫 번째 플레이어에 의한 이탈은 독특한 서브게임 퍼펙트 평형이며, 어떤 나시 평형에서도 요구하는 것으로, 역유도 방식으로 성립할 수 있다. 두 명의 선수가 최종 라운드에 도달했다고 가정해 보자; 두 번째 선수는 탈주하여 조금 더 큰 몫을 차지함으로써 더 잘 할 것이다. 우리는 두 번째 선수가 망명할 것이라고 예상하기 때문에, 첫 번째 선수는 마지막 라운드에서 두 번째 선수의 귀국을 허용함으로써 그녀가 받았을 것보다 약간 더 높은 보상을 취하면서, 두 번째 선수는 2라운드에서 마지막 라운드에서 망명하는 것을 더 잘 한다. 그러나 이것을 알고 있는 두 번째 선수는 3라운드에서 마지막 라운드에서 첫 번째 선수가 2라운드에서 마지막 라운드에서 탈주할 수 있도록 허용함으로써 받은 것보다 약간 더 높은 보상을 받아내야 한다. 이 추리는 게임 트리를 통해 거꾸로 진행되며, 1라운드에서 첫 번째 선수가 망명하는 것이 최선의 행동이라고 결론을 내린다. 같은 추리가 게임 트리의 어떤 노드에도 적용될 수 있다.

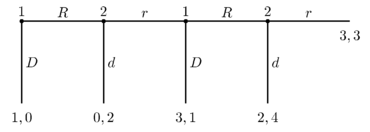

4라운드 후 종료되는 게임의 경우, 이 추론은 다음과 같이 진행된다. 만약 우리가 마지막 라운드에 도달한다면, 2번 플레이어는 r 대신 d를 선택해 3번 대신 4개의 동전을 받는 것이 더 나을 것이다. 다만 2가 d를 선택한다는 점에서 2가 아닌 3을 받아 2차에서 D를 선택해야 한다. 1이 2차에서 마지막 라운드에서 D를 선택한다는 점을 감안하면 2는 1이 아닌 2를 받아 3차에서 D를 선택해야 한다. 그러나 이를 감안할 때 1번 플레이어는 0 대신 1번을 받아 D를 선택해야 한다.

지네시 경기에는 나시 평형기가 많지만, 각 경기에서는 1라운드 1번 선수의 결함과 다음 라운드 2번 선수의 패스를 만류할 정도로 잦은 결함을 보이고 있다. 내시 평형 상태에 있다고 해서 서브게임 퍼펙트 평형에서처럼 게임의 모든 지점에서 전략이 합리적일 필요는 없다. 이것은 결코 기록되지 않은 이후의 경기 라운드에서 협력적인 전략이 여전히 내시 평형 상태에 있을 수 있다는 것을 의미한다. 위의 예에서 한 개의 나시 평형은 양쪽 선수가 각 라운드에서 (두 번 다시 도달하지 못한 후반 라운드에서도) 이탈하는 것이다. 또 다른 나시 평형으로는 1번 선수가 1라운드에서 망명하지만 3라운드를 통과하고 2번 선수가 어떤 기회에 망명하는 것이다.

경험적 결과

여러 연구에서 나시 평형(그리고 마찬가지로 서브게임 퍼펙트 평형) 플레이가 거의 관찰되지 않는다는 것을 증명했다. 대신 피실험자들은 "D" (또는 "d")를 선택하기 전에 여러 동작에 대해 "R" (또는 "r")을 연주하면서 부분적인 협력을 정기적으로 보여준다. 경기 전체를 통해 주체가 협력하는 것도 드물다. 예를 들어 McKelvey와 Palfrey(1992), Nagel과 Tang(1998)을 참조한다. 다른 많은 게임 이론 실험에서처럼 학자들은 판돈을 늘리는 효과를 연구해왔다. 다른 게임과 마찬가지로, 예를 들어 최후통첩 게임도, 판돈이 늘어나면서 플레이가 (하지만 도달하지는 않는다) 내쉬 평형 플레이에 접근한다.[citation needed]

Explanations

Since the empirical studies have produced results that are inconsistent with the traditional equilibrium analysis, several explanations of this behavior have been offered. Rosenthal (1981) suggested that if one has reason to believe his opponent will deviate from Nash behavior, then it may be advantageous to not defect on the first round.

One reason to suppose that people may deviate from the equilibrium behavior is if some are altruistic. The basic idea is that if you are playing against an altruist, that person will always cooperate, and hence, to maximize your payoff you should defect on the last round rather than the first. If enough people are altruists, sacrificing the payoff of first-round defection is worth the price in order to determine whether or not your opponent is an altruist. Nagel and Tang (1998) suggest this explanation.

Another possibility involves error. If there is a significant possibility of error in action, perhaps because your opponent has not reasoned completely through the backward induction, it may be advantageous (and rational) to cooperate in the initial rounds.

However, Parco, Rapoport and Stein (2002) illustrated that the level of financial incentives can have a profound effect on the outcome in a three-player game: the larger the incentives are for deviation, the greater propensity for learning behavior in a repeated single-play experimental design to move toward the Nash equilibrium.

Palacios-Huerta and Volij (2009) find that expert chess players play differently from college students. With a rising Elo, the probability of continuing the game declines; all Grandmasters in the experiment stopped at their first chance. They conclude that chess players are familiar with using backward induction reasoning and hence need less learning to reach the equilibrium. However, in an attempt to replicate these findings, Levitt, List, and Sadoff (2010) find strongly contradictory results, with zero of sixteen Grandmasters stopping the game at the first node.

Significance

Like the Prisoner's Dilemma, this game presents a conflict between self-interest and mutual benefit. If it could be enforced, both players would prefer that they both cooperate throughout the entire game. However, a player's self-interest or players' distrust can interfere and create a situation where both do worse than if they had blindly cooperated. Although the Prisoner's Dilemma has received substantial attention for this fact, the Centipede Game has received relatively less.

Additionally, Binmore (2005) has argued that some real-world situations can be described by the Centipede game. One example he presents is the exchange of goods between parties that distrust each other. Another example Binmore (2005) likens to the Centipede game is the mating behavior of a hermaphroditic sea bass which takes turns exchanging eggs to fertilize. In these cases, we find cooperation to be abundant.

Since the payoffs for some amount of cooperation in the Centipede game are so much larger than immediate defection, the "rational" solutions given by backward induction can seem paradoxical. This, coupled with the fact that experimental subjects regularly cooperate in the Centipede game, has prompted debate over the usefulness of the idealizations involved in the backward induction solutions, see Aumann (1995, 1996) and Binmore (1996).

See also

References

- Aumann, R. (1995). "Backward Induction and Common Knowledge of Rationality". Games and Economic Behavior. 8 (1): 6–19. doi:10.1016/S0899-8256(05)80015-6.

- ——— (1996). "A Reply to Binmore". Games and Economic Behavior. 17 (1): 138–146. doi:10.1006/game.1996.0099.

- Binmore, K. (2005). Natural Justice. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517811-1.

- ——— (1996). "A Note on Backward Induction". Games and Economic Behavior. 17 (1): 135–137. doi:10.1006/game.1996.0098.

- Levitt, S. D.; List, J. A. & Sadoff, S. E. (2010). "Checkmate: Exploring Backward Induction Among Chess Players" (PDF). American Economic Review. 101 (2): 975–990. doi:10.1257/aer.101.2.975.

- McKelvey, R. & Palfrey, T. (1992). "An experimental study of the centipede game". Econometrica. 60 (4): 803–836. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.295.2774. doi:10.2307/2951567. JSTOR 2951567.

- Nagel, R. & Tang, F. F. (1998). "An Experimental Study on the Centipede Game in Normal Form: An Investigation on Learning". Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 42 (2–3): 356–384. doi:10.1006/jmps.1998.1225.

- Palacios-Huerta, I. & Volij, O. (2009). "Field Centipedes". American Economic Review. 99 (4): 1619–1635. doi:10.1257/aer.99.4.1619.

- Parco, J. E.; Rapoport, A. & Stein, W. E. (2002). "Effects of financial incentives on the breakdown of mutual trust". Psychological Science. 13 (3): 292–297. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.612.8407. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00454. PMID 12009054.

- Rapoport, A.; Stein, W. E.; Parco, J. E. & Nicholas, T. E. (2003). "Equilibrium play and adaptive learning in a three-person centipede game". Games and Economic Behavior. 43 (2): 239–265. doi:10.1016/S0899-8256(03)00009-5.

- Rosenthal, R. (1981). "Games of Perfect Information, Predatory Pricing, and the Chain Store". Journal of Economic Theory. 25 (1): 92–100. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.482.8534. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(81)90018-1.

External links

- EconPort article on the Centipede Game

- Rationality and Game Theory - AMS column about the centipede game

- Online experiment in VeconLab

- Play the Centipede game in your browser on gametheorygame.nl