나왈

Narwhal| 나왈[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

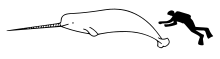

| 평균 사람과 비교한 크기 | |

| 과학 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 코데아타 |

| 클래스: | 포유류 |

| 주문: | Artiodactyla |

| 인프라오더: | 고래목 |

| 가족: | 단동과 |

| 속: | 모노돈 린네, 1758년 |

| 종: | 모노케로스 |

| 이항명 | |

| 모노돈모노케라톱스 | |

| |

| 나왈 개체군의 분포 | |

나왈(Monodon monoceros)은 이빨고래의 일종입니다. 모노돈과(Monodontidae)에 속하며, 모노돈속(Monodon)의 유일종입니다. 다 자란 나팔은 보통 길이가 3.0~5.5m(9.8~18.0피트)이고 무게는 800~1,600kg(1,800~3,500lb)입니다. 이 종의 가장 두드러진 특징은 최대 3m (9.8피트)에 달하는 성인 수컷의 긴 단일 엄니입니다. 나팔은 흰색이고 몸 전체에 불규칙한 흑갈색의 반점이 흩어져 있습니다. 등지느러미 대신 얕은 등지느러미를 가지고 있습니다. 그것은 사회적 동물이며 최대 20명의 구성원으로 그룹을 구성할 수 있습니다. 칼 린네는 1758년에 그의 작품인 Systema Naturae에서 이 종을 과학적으로 묘사했습니다.

북극해에서 주로 발견되며, 북극곰과 범고래의 포식 공격에만 취약합니다. 나팔고래는 일반적으로 6월에서 9월 사이에 배핀 만을 방문합니다. 이 기간이 지나면 약 1,700km(1,100mi)에 이르는 데이비스 해협으로 이동하여 4월까지 그곳에 머무릅니다. 먹이는 대부분 아르코가두스 빙하, 보레오가두스 사야다, 그린란드 넙치, 갑오징어, 새우, 암후크 오징어로 이루어져 있습니다. 나팔은 가장 깊은 곳에 사는 해양 포유류 중 하나로, 많은 개체들이 1,500 m (5,000 ft) 이상의 깊이에서 잠수합니다. 4월이나 5월에 해양 패키지에서 짝짓기를 하며, 평균 15개월 동안 지속되는 임신을 합니다. 대부분의 다른 고래류들처럼, 나팔은 다른 고래류들과 의사소통을 하기 위해 클릭, 휘파람, 노크를 사용합니다.

170,000마리의 살아있는 나팔고래가 있는 것으로 추정되며, 이 종은 국제 자연 보전 연맹에 의해 가장 덜 우려되는 종으로 등재되었습니다. 나팔고래는 수백 년 동안 캐나다 북부와 그린란드의 이누이트에 의해 고기와 상아를 얻기 위해 사냥되어 왔으며 규제된 생계형 사냥이 계속되고 있습니다.

분류법

나팔은 칼 린네가 1758년에 그의 Systema Naturae에서 처음 기술한 많은 종들 중 하나였습니다.[6] 이 종의 가장 초기 묘사 중 하나는 올라우스 마그누스가 1555년에 이마에 뿔이 달린 물고기 같은 생물을 그린 것입니다.[7] 이 동물의 이름은 고대 노르드어 nár에서 유래되었는데, "시체"를 의미하며, 물 표면에 있을 때 회색으로 얼룩진 색소 [8]침착과 움직이지 않는 경향("로깅"이라고 함)을 참조한 것으로 추정됩니다.[9] 학명인 모노돈 모노케로(Monodon monoceros)는 그리스어 모노돈에서 "단이빨 외뿔"을 의미하는 모노케로(monókero)로 유래되었습니다.[10]

나팔고래는 흰돌고래(Delphinapterus leucas)와 가장 밀접한 관련이 있습니다. 이 두 종은 함께 "흰고래"로 불리기도 하는 모노돈티과(Monodontidae)의 유일한 현존하는 종으로 구성됩니다. 모노돈티과는 뚜렷한 멜론 (음향 감각 기관), 짧은 주둥이, 그리고 진정한 등지느러미가 없는 것으로 구별됩니다.[11]

나왈과 벨루가는 별개의 속으로 분류되지만, 매우 드물게 교배할 수 있다는 증거가 있습니다. 1990년경 웨스트 그린란드에서 비정상적으로 생긴 고래 한 마리를 포함한 세 마리의 동물의 유해가 발견되었습니다. 해양동물학자들은 이 특이한 고래를 알려진 다른 종들과 다르게 묘사했고, 나팔과 벨루가 사이의 중간 특징을 가지고 있어, 이 고래가 나를루가(두 종의 잡종)에 속한다는 것을 나타내었고,[12] 2019년에 DNA 분석을 통해 이 사실이 확인되었습니다.[13] 이 잡종이 번식할 수 있는지 여부는 아직 알려지지 않았습니다.[14][12]

진화

유전적 증거에 따르면 델피노이데아 계통군 내에서 돌고래는 흰고래와 더 밀접한 관련이 있으며 이 두 계통군은 지난 1,100만 년 이내에 돌고래로부터 갈라진 별도의 계통군을 구성하고 있습니다.[15] 화석 증거는 고대 흰고래가 열대 바다에서 살았다는 것을 보여줍니다. 그들은 플라이오세 동안 해양 먹이 사슬의 변화에 대응하여 북극과 아북극 해역으로 이동했을 수 있습니다.[16] 2020년 유전체 염기서열 분석을 기반으로 한 계통발생학 연구에 따르면 약 498만 년 전(mya)에 흰돌고래가 흰돌고래에서 분리되었습니다.[17] 모노돈티과 화석을 분석한 결과, 약 10.82~20.12 mya 정도의 Phocoenidae에서 분리된 것으로 보이며, 자매 분류군으로 간주됩니다.[18] 다음 계통수는 모노돈티과(Monodontidae)에 대한 2019년 연구를 기반으로 합니다.[19]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

묘사

나팔고래는 중간 크기의 고래로, 엄니를 제외한 몸길이는 3.0~5.5m(10~18피트)입니다.[20][21] 수컷은 평균 4.1m (13.5피트), 암컷은 평균 3.5m (11.5피트)입니다. 몸무게는 800~1,600kg(1,760~3,530lb)이며, 수컷이 암컷보다 큽니다.[20] 수컷 나팔원숭이는 보통 3.9m (12.8피트)의 길이에 11세에서 13세 사이에 성적으로 성숙합니다. 암컷은 5살에서 8살 사이의 더 어린 나이에 성적으로 성숙해집니다. 이 나이는 약 3.4 m (11.2 ft)입니다.[20]

나팔의 색소침착은 얼룩덜룩한 무늬로 흰색 바탕에 흑갈색의 자국이 있습니다.[8] 태어날 때 가장 어둡고 나이가 들수록 창백해집니다. 성적으로 성숙할 때 배꼽과 생식기 슬릿에 흰색 반점이 생깁니다. 나이 든 수컷들은 거의 순백색일지도 모릅니다.[20][22] 등지느러미가 없고, 대신 얕은 등지느러미를 가지고 있습니다. 이것은 아마도 얼음 아래에서 수영을 더 쉽게 하거나, 구르기를 더 쉽게 하거나, 표면적과 열 손실을 줄이기 위한 진화적 적응일 것입니다.[23] 그것의 목 척추는 대부분의 고래들처럼 함께 융합되는 대신 육지 포유류의 그것처럼 관절로 연결되어 있어 목의 유연성이 매우 높습니다. 이러한 특성은 밀접하게 관련된 흰긴수염고래가 공유합니다.[9] 암컷 나팔의 꼬리 흡충은 앞쪽 가장자리가 뒤로 쓸고 있고, 수컷 나팔의 꼬리 흡충은 그런 특징이 없으며, 대신 안쪽으로 휘어져 있습니다. 이는 엄니로 인한 항력을 줄이기 위한 적응이라 생각됩니다.[21]

대부분의 다른 해양 포유류와 비교했을 때, 나팔은 몸 안에 미오글로빈의 양이 더 많아 더 깊은 잠수를 용이하게 합니다.[24] 골격근은 심해에서 장기간 먹이를 찾을 수 있도록 적응되어 있습니다. 이러한 활동을 하는 동안 산소는 일반적으로 느리게 전환되는 근육에 저장되어 느리지만 기동 가능한 동작을 가능하게 합니다.[25]

투스크

수컷 나팔의 가장 눈에 띄는 특징은 하나의 긴 엄니인데, 이는 위턱의 왼쪽에서 돌출된 송곳니입니다[26].[27] 엄니는 일생 동안 자라며 평균 1.5~2.5m (4.9~8.2피트)에 달합니다.[28][29] 최대 엄니 길이는 3m(10피트)입니다.[30] 속이 비어 있으며 무게는 최대 7.45kg(16.4lb)입니다. 어떤 수컷은 두 개의 엄니를 기를 수도 있는데, 이는 오른쪽 개도 입술을 통해 자랄 때 발생합니다.[31] 암컷은 엄니를 거의 자라지 않습니다: 엄니가 자라지 않을 때, 엄니는 일반적으로 수컷보다 작고, 눈에 띄는 나선은 없습니다.[32][33]

나왈 엄니의 기능에 대해 논의하고 있습니다. 어떤 생물학자들은 나팔원숭이들이 그들의 엄니를 싸움에 사용한다고 제안하는 반면, 다른 생물학자들은 그들의 엄니가 해빙을 깨거나 먹이를 찾는데 사용될 수 있다고 주장합니다. 그러나 나팔 엄니는 사회적 지위를 나타내기 위해 사용되는 2차 성징이라는 데에는 공감대가 형성되어 있습니다.[34] 엄니는 주변 해양 환경의 바닷물 자극을 뇌로 연결하는 수백만 개의 신경 말단을 가진 고도로 신경이 발달한 감각 기관으로 동물 주변의 온도 변화를 감지합니다.[35][36][37] 2014년 논문에서는 수컷 외뿔고래가 엄니를 함께 문지르는 것이 이전에 가정한 공격적인 남성 대 남성 경쟁의 자세 표시가 아니라 각각 통과한 물의 특성에 대한 정보를 전달하는 방법이라고 제안했습니다.[26] 2016년 8월, 누나부트주 트렘블레이 사운드에서 외뿔고래가 표면에서 먹이를 먹는 드론 비디오는 엄니가 작은 북극 대구를 두드리고 기절시키는 데 사용되어 먹이로 더 쉽게 잡을 수 있음을 보여주었습니다.[38][39] 일반적으로 엄니가 없는 암컷이 일반적으로 수컷보다 더 오래 살기 때문에 엄니는 동물의 생존에 중요한 기능을 할 수 없습니다. 따라서 일반적으로 나팔 상아의 일차적인 기능은 생식과 관련되어 있다고 받아들여지고 있습니다.[40]

전치

나팔에는 위턱에 위치한 열린 치아 소켓에 주로 서식하는 여러 개의 작은 전치류가 있습니다. 이 치아는 개방형 치아 소켓을 후방, 복부 및 측방으로 둘러싸고 있으며 모양과 재질이 다양합니다.[26][41] 작은 치아의 다양한 형태와 해부학은 진화적 노화의 경로를 나타냅니다.[26]

분배

나팔은 북극해의 대서양과 러시아 지역에서 주로 발견됩니다. 개체는 일반적으로 허드슨 만, 허드슨 해협, 배핀 만의 북쪽 지역,[42][43] 그린란드의 동쪽 해안, 그린란드의 북쪽 끝에서 동쪽으로 러시아 동부(동쪽 170°)로 이어지는 스트립과 같은 캐나다 북극 군도에서 기록됩니다. 이 스트립의 땅에는 스발바르, 프란츠 조셉 랜드, 세베르나야 젬랴가 있습니다.[8] 나팔의 최북단 목격은 북위 약 85°의 프란츠 요제프 랜드 북쪽에서 발생했습니다.[8] 허드슨 베이 북부에는 12,500마리로 추정되는 나팔고래가 있는 반면 배핀 베이에는 약 140,000마리가 살고 있습니다.[44]

마이그레이션

나팔고래는 계절적 이동을 보이며, 일반적으로 얕은 물에서 얼음이 없는 선호되는 여름 장소로 돌아가는 충실도가 높습니다. 여름에는 10-100마리의 무리를 지어 해안으로 더 가까이 이동합니다. 겨울에는 두꺼운 얼음 아래에서 더 깊은 바다로 이동하고, 해빙의 좁은 틈에서 표면으로 나오거나, 납으로 알려진 더 넓은 균열에서 표면으로 이동합니다.[45] 봄이 오면, 이 리드들은 수로로 열리고 나팔들은 해안 만으로 돌아옵니다.[46] Narwhals는 일반적으로 6월에서 9월 사이에 북쪽으로 더 이동합니다. 이 기간 후, 그들은 데이비스 해협으로 남쪽으로 이동하는데, 그 여정은 약 1,700 킬로미터(1,100 마일)에 걸쳐 있으며, 4월까지 그곳에 머무릅니다.[44] 캐나다와 서그린란드에서 온 나팔들은 5% 미만의 개방된 물과 높은 밀도의 그린란드 넙치가 있는 대륙 경사면을 따라 데이비스 해협과 배핀 만의 팩아이스를 정기적으로 방문합니다.[47]

행동 및 생태학

나팔들은 보통 5명에서 10명, 때로는 20명까지 모입니다. 그룹은 암컷과 어린 수컷만 있는 "수양"일 수도 있고, 산란 후의 수컷 또는 성체 수컷("황소")만 포함할 수도 있지만, 혼합 그룹은 연중 언제든지 발생할 수 있습니다.[20] 여름에는 여러 그룹이 모여 500마리에서 1,000마리 이상의 개체를 포함할 수 있는 더 큰 집합체를 형성합니다.[20] 황소등고래들이 서로의 엄니를 문지르는 것이 관찰되었는데, 이는 "투스킹"이라고 알려져 있는 표시입니다.[36][48]

나팔은 월동하는 바다에서 해양 포유류에게 기록된 가장 깊은 잠수를 하며, 하루에 15번 이상 최소 800m(2,620ft)까지 잠수하며, 많은 잠수가 1,500m(4,920ft)에 달합니다. 이 깊이까지 잠수하면 약 25분 동안 지속됩니다.[49] 다이빙 시간은 계절성뿐만 아니라 환경 간의 지역적 차이에 따라 깊이가 다를 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 배핀만 월동지에서는 강수가 많은 해안, 일반적으로 배핀만 남쪽에 있는 깊은 곳으로 잠수하는 경향이 있습니다. 이는 하위 집단 간의 서식지 구조, 먹이 가용성 또는 유전적 적응의 차이를 시사합니다. 북쪽 월동지에서는, 이 지역의 수심이 더 깊음에도 불구하고, 나팔들은 남쪽 개체수만큼 깊게 잠수하지 않습니다. 이것은 주로 먹이가 표면에 더 가까이 집중되어 있기 때문에 나팔고래가 먹이 찾기 전략을 변경하게 됩니다.[49]

다이어트

다른 해양 포유류에 비해, 나팔은 상대적으로 제한적이고 전문적인 식단을 가지고 있습니다.[50] 73마리의 나팔고래의 위 내용물을 조사한 결과 북극 대구(Boreogadus saya)가 가장 많이 섭취하는 먹이로 나타났고, 그린란드 넙치(Rainhardtius hiphoglosoides)가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 많은 양의 보레오-대서양 암후크 오징어(Gonatus fabricii)가 발견되었습니다. 수컷은 암컷보다 붉은 물고기(세바스테스 마리누스)와 북극 대구(Arctogadus glacialis) 두 종을 더 자주 섭취했습니다. 두 종 모두 주로 500m(1,640피트) 이상의 깊은 곳에서 발견됩니다. 이 연구는 또한 먹이의 크기가 성별이나 연령에 따라 다르지 않다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[51] 위에서 발견되는 다른 품목에는 울프피쉬, 카펠린, 홍어 알 및 때로는 바위가 포함됩니다.[20][47][45]

겨울에는 빽빽한 얼음 속에서 주로 광어를 비롯한 해면 먹이를 먹고 삽니다. 여름 동안 나팔원숭이는 북극 대구와 그린란드 넙치를 주로 먹으며, 북극 대구와 같은 다른 물고기가 나머지 먹이를 구성합니다.[51] 나팔고래는 겨울 동안 여름 동안보다 훨씬 더 많은 음식을 소비합니다.[47][45] 잘 발달된 치열이 없기 때문에, 나팔은 먹이에 가까이 헤엄쳐서 입으로 빨아먹으면서 먹이를 먹는 것으로 여겨집니다.[52]

사육중

암컷은 6~8살이 되면 송아지를 낳기 시작합니다.[9] 다 자란 나팔고래는 연안에서 먹이 활동을 하는 3월부터 5월까지 짝짓기를 합니다. 암컷은 임신 15개월 후 7월에서 8월 사이에 송아지를 낳습니다.[53] 대부분의 해양 포유류들과 마찬가지로, 평균 1.5 m (4.9 ft)의 길이를 가진 단 한 마리의 어린 동물만 태어났습니다. 태어날 때, 송아지는 흰색 또는 밝은 회색입니다.[54] 출생 간격은 일반적으로 2년에서 3년 사이입니다.[55] 여름에 배핀 섬의 다른 해안 입구를 따라 개체군을 집계하는 동안 송아지 수는 10,000마리에서 35,000마리 사이의 전체 수의 0.05%에서 5%까지 다양했으며, 이는 더 높은 송아지 수가 분만 및 보육원 서식지를 유리한 입구에 반영할 수 있음을 나타냅니다.[56]

갓 태어난 송아지는 지방이 풍부한 산모의 모유를 수유하면서 두꺼워지는 얇은 지방층으로 삶을 시작합니다. 송아지는 약 20개월 동안 우유에 의존합니다.[9] 이 긴 수유 기간은 송아지가 성숙하면서 생존하는 데 필요한 기술을 배울 수 있는 시간을 줍니다. 송아지는 일반적으로 어미의 두 몸 길이 내에 머무릅니다.[9][56] 이 종은 갱년기를 겪는 것으로 생각됩니다. 이 단계 동안 암컷은 무리의 송아지를 계속 돌볼 수 있습니다.[55]

2024년 연구에서 과학자들은 Odontoceti의 5종이 폐경기를 진화시켜 전반적으로 더 높은 수명을 얻었다고 결론지었습니다. 반면에 그들의 생식 수명은 늘어나지도 줄어들지도 않았습니다. 이것에 대한 몇 가지 주요 이유, 즉 생식 및 비생식 여성이 송아지의 발달에 역할을 하는 세대 간 지원이 일치합니다. Odontoceti 5종의 송아지는 한 마리의 암컷이 성공적으로 사육하기가 매우 어렵기 때문에 갱년기 암컷의 도움이 생존 가능성을 높이기 위해 필요하다는 가설이 세워졌습니다.[57]

의사소통

대부분의 이빨고래들처럼, 나팔고래들은 먹이를 찾기 위해 길을 찾고 사냥하기 위해 소리를 사용합니다. 내르왈스는 주로 블로우 홀 근처의 챔버 사이의 공기 이동에 의해 만들어진 "클릭", "휘파람", "노크"를 통해 목소리를 냅니다.[58] 이 소리들의 진동수는 0.3에서 125헤르츠 사이인 반면, 반향정위에 사용되는 소리들은 일반적으로 19에서 48헤르츠 사이입니다.[59][60] 소리는 두개골의 경사진 앞쪽에서 반사되어 동물의 멜론에 의해 집중되며, 이는 주변 근육 구조를 통해 제어할 수 있습니다.[61] 반향 위치 클릭은 주로 먹이 탐지와 근거리에서 장애물을 찾기 위해 생성됩니다.[62] "휘파람"과 "제비"는 주로 다른 포드 구성원들과 의사 소통하는 데 사용됩니다.[63] 같은 포드에서 녹음된 통화는 다른 포드에서 녹음된 통화보다 더 유사하므로 그룹 또는 개인별 통화가 나왈에서 발생할 가능성을 시사합니다. Narwhals는 다양한 음향 환경에서 소리 전파를 극대화하기 위해 펄스 호출의 지속 시간과 피치를 조정하기도 합니다.[64] 외뿔고래가 내는 다른 소리로는 트럼펫 소리와 "삐걱거리는 문 소리"가 있습니다.[9] 나왈 보컬 레퍼토리는 근연종인 벨루가와 유사하며, 호루라기 주파수 범위, 호루라기 지속 시간 및 펄스 호출의 반복 속도가 비슷하지만, 벨루가 호루라기는 주파수 범위가 더 높고 호루라기 윤곽이 더 다양할 것으로 생각됩니다.[65]

수명 및 사망률 요인

나팔원숭이는 평균 50년을 살고 있지만, 눈의 수정체에서 나온 아미노산을 이용한 나이 결정 기술은 암컷 나팔원숭이는 115 ± 10년, 수컷 나팔원숭이는 84 ± 9년까지 살 수 있음을 시사합니다.[66] 질식에 의한 사망은 늦가을 북극이 얼기 전에 나팔고래가 이동하지 못할 때 종종 발생합니다.[20][67] 나팔고래는 공기를 마시면서 개방된 물에 더 이상 접근할 수 없고 얼음이 너무 두꺼워서 뚫을 수 없다면 익사합니다. 얼음에 숨 쉬는 구멍은 최대 1,450m (4,760ft) 떨어져 있을 수 있는데, 이로 인해 먹이를 찾는 장소의 사용이 제한되고 이 구멍은 어른 고래가 숨을 쉴 수 있도록 최소 0.5m (1.6ft) 너비여야 합니다.[24] 내르왈은 또한 이러한 포획 사건으로 인해 굶어 죽습니다.[20]

1914-1915년에 포획은 약 600명에게 영향을 미쳤으며, 대부분은 디스코 만과 같은 지역에서 발생했습니다. 1915년 웨스트 그린란드에서 가장 큰 포획에서, 1,000마리가 넘는 나팔고래들이 얼음 아래에 갇혔습니다.[68] 북극 겨울인 2008년에서 2010년 사이에 몇 가지 바다 포획 사례가 기록되었는데, 이전에 그러한 사건이 기록된 적이 없는 일부 지역도 포함됩니다.[67] 이것은 여름 장소에서 출발하는 날짜가 더 늦다는 것을 시사합니다. 그린란드 주변 지역은 바람과 해류로 인한 주변 지역의 해빙 이류(이동)를 경험하여 그 과정에서 해빙 농도의 변화를 촉진합니다. 같은 지역으로 돌아가는 경향 때문에 날씨와 얼음 상태의 변화가 항상 개활지를 향한 나팔 이동과 관련이 있는 것은 아닙니다. 해빙 변화가 나팔고래에게 얼마나 위험을 주는지는 현재 불분명합니다.[20]

주요 포식자는 북극곰으로, 일반적으로 어린 나고래가 숨쉴 수 있는 구멍에서 기다립니다.[20][69] 범고래는 함께 무리를 지어 나팔 꼬투리를 압도하고 포위하며,[70] 한 번의 공격으로 수십 마리의 나팔을 죽입니다.[71] 범고래는 범고래와 같은 포식자를 피하기 위해 속도에 의존하기보다는 얼음 흐름 아래에 숨기 위해 장기간의 잠수를 사용할 수 있습니다.[24]

보존.

나팔고래는 IUCN 적색 목록에서 가장 관심사가 적은 종으로 분류되어 있습니다. 2017년 기준으로 전 세계 인구는 총 17만 명 중 성숙한 개체가 123,000명으로 추정됩니다. 노던 허드슨 베이에는 2011년 기준으로 약 12,000마리의 나팔고래가 있으며, 2013년에는 서머셋 섬에 약 49,000마리가 있습니다. 애드미럴티 만에 약 35,000개, 이클립스 사운드에 10,000개, 이스턴 배핀 베이에 17,000개, 존스 사운드에 12,000개가 있습니다. 스미스 사운드, 잉글필드 브레딩, 멜빌 베이의 인구 수는 각각 16,000명, 8,000명, 3,000명입니다. 스발바르 해역에는 약 837마리의 나팔고래가 살고 있습니다.[4]

1972년, 미국은 해양 포유류 보호법에 의해 명시된 바와 같이 외뿔고래 신체 부위로 만든 제품의 상업적 수입을 금지했습니다.[4] 나팔원숭이는 CITES 및 CMS 부록 II에 나열되어 있으며, 이는 나팔원숭이와 그 신체 부위의 거래가 국제적으로 제한되고 통제된다는 것을 의미합니다.[5][72] 이 종은 또한 COSEWIC에서 멸종 위기에 처한 종으로 분류됩니다.[44] 나팔은 감금하기가 어렵습니다.[36]

위협

인간은 나팔을 사냥합니다; 상업적으로 거래되는 나팔 제품에는 피부, 고기, 치아 및 엄니, 조각된 척추가 포함됩니다. 캐나다에서 600마리, 그린란드에서 400마리 등 매년 약 1,000마리의 나팔고래가 죽임을 당합니다. 캐나다의 수확량은 1970년대에 이 수준에서 꾸준했고, 1980년대 후반과 1990년대에는 연간 300-400까지 떨어졌다가 1999년 이후 다시 증가했습니다. 그린란드는 1980년대와 1990년대에 매년 700-900개씩 더 많이 수확했습니다.[73]

엄니는 캐나다와[74][75] 그린란드에서 조각된 것과 조각되지 않은 것 모두 판매됩니다.[76] 사냥한 내르고래 한 마리당 평균 1~2개의 척추뼈와 1~2개의 이빨이 팔립니다.[74] 그린란드에서는 껍질(묵투크)을 어류 공장에 상업적으로 [76]판매하고 캐나다에서는 다른 지역 사회에 판매합니다.[74] 2013년 허드슨 만에서 나팔 사냥으로 받은 연간 총 가치의 추정치 중 하나는 나팔당 6,500 캐나다 달러(6,300 달러)였으며, 그 중 4,570 캐나다 달러(4,440 달러)는 피부와 고기에 대한 것이었습니다. 그러나 시간과 장비에서 비용을 뺀 순이익은 1인당 CA$7(US$6.80)의 손실을 입었습니다. 사냥은 보조금을 받지만, 그들은 돈보다는 주로 전통을 지지하고 있고, 경제 분석은 고래 관찰이 대안적인 수익원이 될 수 있다고 지적했습니다.[74]

나팔고래가 성장함에 따라 생물학적 축적이 이루어집니다.[77] 해양의 오염이 해양 포유류의 생물 축적의 주요 원인이라고 생각됩니다. 이것은 나팔 개체군의 건강 문제로 이어질 수 있습니다.[78] 생체 축적을 하면 수많은 금속이 지방, 간, 신장, 근육 등에 나타납니다. 신장은 간에 비해 아연과 카드뮴의 농도가 높습니다. 반면에 납, 구리, 수은은 거의 풍부하지 않았습니다. 한 연구에 따르면 간과 신장에는 이 금속들의 농도가 밀집되어 있는 반면, 지방에는 이 금속들이 거의 없었습니다. 체중과 성별이 다른 사람들은 그들의 장기에 있는 금속의 농도에 있어서 차이를 보였습니다.[77]

나팔은 환경, 특히 배핀 만과 데이비스 해협 지역과 같은 북쪽 월동지에서 해빙 범위를 변경하여 기후 변화에[46] 가장 취약한 북극 해양 포유류 중 하나입니다. 이들 지역에서 수집된 위성 데이터는 해빙의 양이 이전보다 현저하게 감소했음을 보여줍니다.[79] 나팔원숭이의 먹이 찾기 범위는 그들의 생활 초기에 발달된 패턴으로 여겨지며 겨울 동안 필요한 식량 자원을 얻을 수 있는 능력을 증가시킵니다. 이 전략은 지역 먹이 분포에 대한 개별 수준의 반응보다는 강력한 사이트 충실도에 초점을 맞추고 겨울 동안 초점을 맞춘 먹이 찾기 지역을 초래합니다. 이와 같이, 조건이 바뀌었음에도 불구하고, 나팔들은 이주하는 동안 같은 지역으로 계속 돌아갈 것입니다.[79] 이들은 플리오세 후기에 출현했으며 따라서 빙하와 기후 변화에 적응을 겪었을 것입니다.[80]

해빙의 감소는 포식에 대한 노출을 증가시켰을 수 있습니다. 2002년 시오라팔루크의 사냥꾼들은 잡힌 나팔수의 증가를 경험했지만, 이러한 증가는 노력 증가와 관련이 없는 것으로 보이며,[81] 기후 변화가 나팔수를 수확에 더 취약하게 만들고 있을 수 있음을 암시합니다. 과학자들은 인구 수를 평가하고, 지속 가능한 할당량을 할당하고, 지속 가능한 개발에 대한 현지 수용을 보장할 것을 권장합니다. 석유 탐사와 관련된 지진 조사는 정상적인 이동 패턴을 방해합니다. 이러한 교란된 이동은 또한 해빙 포획 증가와 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[82]

인간과의 관계

이누이트

나팔 사냥은 일반적으로 불법이지만 이누이트는 합법적으로 나팔 사냥이 허용됩니다. 그들은 침입하기가 매우 어렵고 사냥꾼들을 위해 어려운 어획물을 만듭니다.[83] 나팔고래는 많은 양의 지방 때문에 바다표범이나 고래와 같은 다른 바다 포유동물들과 같은 방식으로 광범위하게 사냥되어 왔습니다. 나팔의 거의 모든 부분, 즉 고기, 피부, 지방, 장기가 소비됩니다. 생피와 붙어있는 지방인 묵뚝이는 별미로 여겨집니다. 동물 한 마리당 한두 개의 척추뼈가 도구와 예술에 사용됩니다.[74][8] 피부는 북극권에서는 얻기 힘든 비타민 C의 중요한 공급원입니다. Qaanaaq와 같은 그린란드의 일부 지역에서는 전통적인 사냥 방법을 사용하고 손으로 만든 카약으로 고래를 작살로 잡습니다. 그린란드와 캐나다 북부의 다른 지역에서는 고속 보트와 사냥용 소총이 사용됩니다.[8]

이누이트 전설에 따르면, 나팔의 엄니는 허리에 작살줄이 묶인 한 여성이 큰 나팔에 꽂힌 후 바다로 끌려가면서 만들어졌습니다. 그런 다음 그녀는 나팔로 변했습니다. 꼬인 매듭으로 쓰고 있던 그녀의 머리카락은 나선형 나팔 엄니가 되었습니다.[84]

알리콘

나팔 엄니는 수세기 동안 유럽에서 많은 사람들이 찾고 있습니다. 이것은 나왈 엄니가 전설적인 유니콘의 뿔이라는 중세의 믿음에서 비롯되었습니다.[85][86] 나팔 엄니의 거래는 대략 1000년에 시작되었습니다.[87] 과학자들은 오랫동안 바이킹들이 그린란드 해변과 주변 지역에 떠밀려온 엄니들을 모았다고 추측해 왔지만, 다른 이들은 북유럽인들이 이누이트에서 엄니들을 얻은 후 유럽인들과 서로 교환했다고 추측하고 있습니다.[88][89] 바이킹들은 전투나 사냥에 사용하기 위해 엄니로 무기를 만들었습니다. 역사가 해들리 미어스(Hadley Meares)는 "유니콘이 그리스도의 상징이 된 중세 시대에 무역이 강화되어 거의 성스러운 동물이 되었습니다."라고 인용합니다.[90] 무역은 르네상스 시대에 널리 퍼졌습니다.[91]

유럽 전역에서, 유니콘 뿔의 능력에 대한 증가하는 페티시에 더하여, 나왈 엄니는 왕과 여왕에게 국가 선물로 주어졌습니다.[85] 엄니의 가격표는 금으로 된 무게보다 수백 배나 더 비싸다고 합니다.[92] 죽음의 침대에 보석으로 덮인 나팔 엄니가 있는 반면,[85] 엘리자베스 1세는 영국의 선원이자 사병인 마틴 프로비셔로부터 10,000 파운드[93] 상당의 나팔 엄니를 받았는데, 그는 이 엄니가 "바다에서 온 것"이라고 제안했습니다. 그런 다음 상아는 호기심이 담긴 캐비닛에 전시되었습니다.[94][95] 그것들은 또한 해독제로 사용되었고, 독을 탐지하는 데 사용되었습니다.[96] 이 알리콘은 많은 약효를 부여받았고, 시간이 흐르면서 자연의 오염된 물을 정화하는 것 외에도 풍진, 홍역, 열, 통증에 대한 사용이 권장되었습니다.[97][98] 17세기 말로 갈수록 과학이 부상하면서 마술과 연금술에 대한 믿음이 줄어들었습니다. 나팔 엄니가 실제 해독제와 반대라는 것이 확인된 후, 그것을 이 목적으로 사용하는 관행은 이후에 중단되었습니다.[99]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ Wilson, Don E.; Reeder, DeeAnn M. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. JHU Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- ^ Newton, Edwin Tulley (1891). The Vertebrata of the Pliocene deposits of Britain. London: Printed for H.M. Stationery off., by Eyre and Spottiswoode. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.57425.

- ^ "Monodon monoceros Linnaeus 1758 (narhwal)". PBDB.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Lowry, L.; Laidre, K.; Reeves, R. (2017). "Monodon monoceros". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T13704A50367651.en.

- ^ a b "Appendices CITES". cites.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). "Monodon monoceros". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Stockholm: Lars Salvius. p. 824.

- ^ McLeish, Todd (2013). Narwhals: Arctic Whales in a Melting World. University of Washington Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-295-80469-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Heide-Jørgensen, M. P.; Laidre, K. L. (2006). Greenland's Winter Whales: The Beluga, the Narwhal and the Bowhead Whale. Ilinniusiorfik Undervisningsmiddelforlag, Nuuk, Greenland. pp. 100–125. ISBN 8-779-75299-3.

- ^ a b c d e f "The narwhal: unicorn of the seas" (PDF). Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1880). "Narwhal". An American Dictionary of the English Language. G. & C. Merriam. p. 854.

- ^ Brodie, Paul (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 200–203. ISBN 0-871-96871-1.

- ^ a b Heide-Jørgensen, Mads P.; Reeves, Randall R. (July 1993). "Description of an anomalous Monodontid skull from West Greenland: a possible hybrid?". Marine Mammal Science. 9 (3): 258–268. Bibcode:1993MMamS...9..258H. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1993.tb00454.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Skovrind, Mikkel; Castruita, Jose Alfredo Samaniego; Haile, James; Treadaway, Eve C.; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Westbury, Michael V.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Szpak, Paul; Lorenzen, Eline D. (20 June 2019). "Hybridization between two high Arctic cetaceans confirmed by genomic analysis". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 7729. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7729S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44038-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6586676. PMID 31221994.

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie (20 June 2019). "First-ever beluga–narwhal hybrid found in the Arctic". Live Science. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Waddell, Victor G.; Milinkovitch, Michel C.; Bérubé, Martine; Stanhope, Michael J. (1 May 2000). "Molecular phylogenetic examination of the Delphinoidea trichotomy: congruent evidence from three nuclear loci indicates that porpoises (Phocoenidae) share a more recent common ancestry with white whales (Monodontidae) than they do with true dolphins (Delphinidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 15 (2): 314–318. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0751. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 10837160.

- ^ Vélez-Juarbe, Jorge; Pyenson, Nicholas D. (1 March 2012). "Bohaskaia monodontoides , a new monodontid (Cetacea, Odontoceti, Delphinoidea) from the Pliocene of the western North Atlantic Ocean". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (2): 476–484. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..476V. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.641705. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 55606151.

- ^ Louis, Marie; Skovrind, Mikkel; Samaniego Castruita, Jose Alfredo; Garilao, Cristina; Kaschner, Kristin; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Haile, James S.; Lydersen, Christian; Kovacs, Kit M.; Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Postma, Lianne; Ferguson, Steven H.; Willerslev, Eske; Lorenzen, Eline D. (29 April 2020). "Influence of past climate change on phylogeography and demographic history of narwhals (Monodon monoceros)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1925): 20192964. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2964. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 7211449. PMID 32315590.

- ^ Racicot, Rachel A.; Darroch, Simon A. F.; Kohno, Naoki (October 2018). "Neuroanatomy and inner ear labyrinths of the narwhal, Monodon monoceros, and beluga, Delphinapterus leucas (Cetacea: Monodontidae)". Journal of Anatomy. 233 (4): 421–439. doi:10.1111/joa.12862. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 6131972. PMID 30033539.

- ^ Bianucci, Giovanni; Pesci, Fabio; Collareta, Alberto; Tinelli, Chiara (4 May 2019). "A new Monodontidae (Cetacea, Delphinoidea) from the lower Pliocene of Italy supports a warm-water origin for narwhals and white whales". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (3): e1645148. Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E5148B. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1645148. hdl:11568/1022436. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 202018525. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Macdonald, David Whyte; Barrett, Priscilla (2001). Mammals of Europe. Princeton University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-691-09160-9. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b Fontanella, Janet E.; Fish, Frank E.; Rybczynski, Natalia; Nweeia, Martin T.; Ketten, Darlene R. (October 2011). "Three-dimensional geometry of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) flukes in relation to hydrodynamics". Marine Mammal Science. 27 (4): 889–898. Bibcode:2011MMamS..27..889F. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00439.x. hdl:1912/4924. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ "Monodon monoceros". Fisheries and Aquaculture Department: Species Fact Sheets. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ Dietz, Rune; Shapiro, Ari D.; Bakhtiari, Mehdi; Orr, Jack; Tyack, Peter L; Richard, Pierre; Eskesen, Ida Grønborg; Marshall, Greg (19 November 2007). "Upside-down swimming behaviour of free-ranging narwhals". BMC Ecology. 7 (1): 14. Bibcode:2007BMCE....7...14D. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-7-14. ISSN 1472-6785. PMC 2238733. PMID 18021441.

- ^ a b c Williams, Terrie M.; Noren, Shawn R.; Glenn, Mike (April 2011). "Extreme physiological adaptations as predictors of climate-change sensitivity in the narwhal (Monodon monoceros)". Marine Mammal Science. 27 (2): 334–349. Bibcode:2011MMamS..27..334W. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00408.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Pagano, Anthony M.; Williams, Terrie M. (15 February 2021). "Physiological consequences of Arctic sea ice loss on large marine carnivores: unique responses by polar bears and narwhals". Journal of Experimental Biology. 224 (Suppl_1). doi:10.1242/jeb.228049. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 33627459.

- ^ a b c d Nweeia, Martin T.; Eichmiller, Frederick C.; Hauschka, Peter V.; Donahue, Gretchen A.; Orr, Jack R.; Ferguson, Steven H.; Watt, Cortney A.; Mead, James G.; Potter, Charles W.; Dietz, Rune; Giuseppetti, Anthony A.; Black, Sandie R.; Trachtenberg, Alexander J.; Kuo, Winston P. (18 March 2014). "Sensory ability in the narwhal tooth organ system". The Anatomical Record. 297 (4): 599–617. doi:10.1002/ar.22886. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 24639076. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Louis, Marie; Skovrind, Mikkel; Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Szpak, Paul; Lorenzen, Eline D. (3 February 2021). "Population-specific sex and size variation in long-term foraging ecology of belugas and narwhals". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (2). Bibcode:2021RSOS....802226L. doi:10.1098/rsos.202226. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 8074634. PMID 33972883.

- ^ Dietz, Rune; Desforges, Jean-Pierre; Rigét, Frank F.; Aubail, Aurore; Garde, Eva; Ambus, Per; Drimmie, Robert; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Sonne, Christian (10 May 2021). "Analysis of narwhal tusks reveals lifelong feeding ecology and mercury exposure". Current Biology. 31 (9): 2012–2019.e2. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E2012D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.018. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 33705717. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Mann, Janet (2000). Cetacean Societies: Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales. University of Chicago Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-226-50341-0. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Dipper, Frances (2021). The Marine World: A Natural History of Ocean Life. Princeton University Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-691-23244-7. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Garde, Eva; Peter Heide-Jørgensen, Mads; Ditlevsen, Susanne; Hansen, Steen H. (January 2012). "Aspartic acid racemization rate in narwhal (Monodon monoceros) eye lens nuclei estimated by counting of growth layers in tusks". Polar Research. 31 (1): 15865. doi:10.3402/polar.v31i0.15865. ISSN 1751-8369.

- ^ Charry, Bertrand; Tissier, Emily; Iacozza, John; Marcoux, Marianne; Watt, Cortney A. (4 August 2021). "Mapping Arctic cetaceans from space: a case study for beluga and narwhal". PLOS ONE. 16 (8): e0254380. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1654380C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254380. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8336832. PMID 34347780.

- ^ B. Eales, Nellie (17 October 1950). "The skull of the foetal narwhal, Monodon monoceros". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 235 (621): 1–33. Bibcode:1950RSPTB.235....1E. doi:10.1098/rstb.1950.0013. ISSN 2054-0280. PMID 24538734. S2CID 40943163. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Best, Robin C. (December 1981). "The tusk of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros): interpretation of its function (Mammalia: Cetacea)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 59 (12): 2386–2393. doi:10.1139/z81-319. ISSN 0008-4301. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Nweeia, Martin T.; Eichmiller, Frederick C.; Hauschka, Peter V.; Donahue, Gretchen A.; Orr, Jack R.; Ferguson, Steven H.; Watt, Cortney A.; Mead, James G.; Potter, Charles W.; Dietz, Rune; Giuseppetti, Anthony A.; Black, Sandie R.; Trachtenberg, Alexander J.; Kuo, Winston P. (April 2014). "Sensory ability in the narwhal tooth organ system". The Anatomical Record. 297 (4): 599–617. doi:10.1002/ar.22886. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 24639076.

- ^ a b c Broad, William (13 December 2005). "It's sensitive. Really". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ Vincent, James (19 March 2014). "Scientists suggest they have the answer to the mystery of the narwhal's tusk". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Laidre, Kristin L.; Moon, Twila; Hauser, Donna D. W.; McGovern, Richard; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Dietz, Rune; Hudson, Ben (October 2016). "Use of glacial fronts by narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in West Greenland". Biology Letters. 12 (10): 20160457. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0457. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 5095189. PMID 27784729.

- ^ Berta, Annalisa (2023). Sea Mammals: The Past and Present Lives of Our Oceans' Cornerstone Species. Princeton University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-691-23664-3.

- ^ Kelley, Trish C.; Stewart, Robert E. A.; Yurkowski, David J.; Ryan, Anna; Ferguson, Steven H. (April 2015). "Mating ecology of beluga ( Delphinapterus leucas ) and narwhal ( Monodon monoceros) as estimated by reproductive tract metrics". Marine Mammal Science. 31 (2): 479–500. Bibcode:2015MMamS..31..479K. doi:10.1111/mms.12165. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ "For a dentist, the narwhal's smile is a mystery of evolution". Smithsonian Insider. 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (2018), "Narwhal: Monodon monoceros", in Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M.; Kovacs, Kit M. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third Edition), Academic Press, pp. 627–631, ISBN 978-0-12-804327-1, archived from the original on 20 January 2023, retrieved 27 January 2024

- ^ Belikov, Stanislav E.; Boltunov, Andrei N. (21 July 2002). "Distribution and migrations of cetaceans in the Russian Arctic according to observations from aerial ice reconnaissance". NAMMCO Scientific Publications. 4: 69–86. doi:10.7557/3.2838. ISSN 2309-2491. Archived from the original on 27 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Watt, C.A.; Orr, J.R.; Ferguson, S.H. (January 2017). "Spatial distribution of narwhal (Monodon monoceros) diving for Canadian populations helps identify important seasonal foraging areas". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 95 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1139/cjz-2016-0178. ISSN 0008-4301. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Laidre, K. L.; Heide-Jorgensen, M. P. (January 2005). "Winter feeding intensity of narwhals (Monodon monoceros)". Marine Mammal Science. 21 (1): 45–57. Bibcode:2005MMamS..21...45L. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01207.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ a b Laidre, Kristin L.; Stirling, Ian; Lowry, Lloyd F.; Wiig, Øystein; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Ferguson, Steven H. (March 2008). "Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change". Ecological Applications. 18 (sp2): S97–S125. Bibcode:2008EcoAp..18S..97L. doi:10.1890/06-0546.1. ISSN 1051-0761. PMID 18494365.

- ^ a b c Laidre, K.L.; Heide-Jørgensen, M.P.; Jørgensen, O.A.; Treble, M.A. (1 January 2004). "Deep-ocean predation by a high Arctic cetacean". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 61 (3): 430–440. Bibcode:2004ICJMS..61..430L. doi:10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.02.002. ISSN 1095-9289.

- ^ "The biology and ecology of narwhals". noaa.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ a b Laidre, Kristin L.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Dietz, Rune; Hobbs, Roderick C.; Jørgensen, Ole A. (17 October 2003). "Deep-diving by narwhals (Monodon monoceros): differences in foraging behavior between wintering areas?". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 261: 269–281. Bibcode:2003MEPS..261..269L. doi:10.3354/meps261269. ISSN 0171-8630.

- ^ Chambault, P.; Tervo, O. M.; Garde, E.; Hansen, R. G.; Blackwell, S. B.; Williams, T. M.; Dietz, R.; Albertsen, C. M.; Laidre, K. L.; Nielsen, N. H.; Richard, P.; Sinding, M. H. S.; Schmidt, H. C.; Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (29 October 2020). "The impact of rising sea temperatures on an Arctic top predator, the narwhal". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 18678. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1018678C. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75658-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7596713. PMID 33122802.

- ^ a b Finley, K. J.; Gibb, E. J. (December 1982). "Summer diet of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) in Pond Inlet, northern Baffin Island". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 60 (12): 3353–3363. doi:10.1139/z82-424. ISSN 0008-4301.

- ^ Jensen, Frederik H.; Tervo, Outi M.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Ditlevsen, Susanne (25 March 2023). "Detecting narwhal foraging behaviour from accelerometer and depth data using mixed-effects logistic regression". Animal Biotelemetry. 11 (1): 14. Bibcode:2023AnBio..11...14J. doi:10.1186/s40317-023-00325-2. ISSN 2050-3385.

- ^ Klinowska, Margaret, ed. (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. IUCN. p. 79. ISBN 2-880-32936-1. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Tinker, Spencer Wilkie (1988). Whales of the World. E. J. Brill. p. 213. ISBN 0-935-84847-9. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ a b Garde, Eva; Hansen, Steen H.; Ditlevsen, Susanne; Tvermosegaard, Ketil Biering; Hansen, Johan; Harding, Karin C.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (7 July 2015). "Life history parameters of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) from Greenland". Journal of Mammalogy. 96 (4): 866–879. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv110. ISSN 0022-2372. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ a b Evans Ogden, Lesley (6 January 2016). "Elusive narwhal babies spotted gathering at Canadian nursery". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Ellis, Samuel; Franks, Daniel W.; Nielsen, Mia Lybkær Kronborg; Weiss, Michael N.; Croft, Darren P. (13 March 2024). "The evolution of menopause in toothed whales". Nature: 1–7. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07159-9. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Blackwell, Susanna B.; Tervo, Outi M.; Conrad, Alexander S.; Sinding, Mikkel H. S.; Hansen, Rikke G.; Ditlevsen, Susanne; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (13 June 2018). "Spatial and temporal patterns of sound production in East Greenland narwhals". PLOS ONE. 13 (6): e0198295. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398295B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198295. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5999075. PMID 29897955.

- ^ Still, Robert; Harrop, Hugh; Dias, Luís; Stenton, Tim (2019). Europe's Sea Mammals Including the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands and Cape Verde: A field guide to the whales, dolphins, porpoises and seals. Princeton University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-691-19062-4. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Miller, Lee A.; Pristed, John; Møshl, Bertel; Surlykke, Annemarie (October 1995). "The click-sounds of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in Inglefield Bay, Northwest Greenland". Marine Mammal Science. 11 (4): 491–502. Bibcode:1995MMamS..11..491M. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1995.tb00672.x. ISSN 0824-0469. S2CID 85148204. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Senevirathna, Jayan Duminda Mahesh; Yonezawa, Ryo; Saka, Taiki; Igarashi, Yoji; Funasaka, Noriko; Yoshitake, Kazutoshi; Kinoshita, Shigeharu; Asakawa, Shuichi (January 2021). "Transcriptomic insight into the melon morphology of toothed whales for aquatic molecular developments". Sustainability. 13 (24): 13997. doi:10.3390/su132413997. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Zahn, Marie J.; Rankin, Shannon; McCullough, Jennifer L. K.; Koblitz, Jens C.; Archer, Frederick; Rasmussen, Marianne H.; Laidre, Kristin L. (12 November 2021). "Acoustic differentiation and classification of wild belugas and narwhals using echolocation clicks". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 22141. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1122141Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-01441-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8589986. PMID 34772963.

- ^ Marcoux, Marianne; Auger-Méthé, Marie; Humphries, Murray M. (October 2012). "Variability and context specificity of narwhal (Monodon monoceros) whistles and pulsed calls". Marine Mammal Science. 28 (4): 649–665. Bibcode:2012MMamS..28..649M. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00514.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Lesage, Véronique; Barrette, Cyrille; Kingsley, Michael C. S.; Sjare, Becky (January 1999). "The effect of vessel noise on the vocal behavior of belugas in the St. Lawrence river estuary, Canada". Marine Mammal Science. 15 (1): 65–84. Bibcode:1999MMamS..15...65L. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00782.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Jones, Joshua M.; Frasier, Kaitlin E.; Westdal, Kristin H.; Ootoowak, Alex J.; Wiggins, Sean M.; Hildebrand, John A. (1 March 2022). "Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhal (Monodon monoceros) echolocation click detection and differentiation from long-term Arctic acoustic recordings". Polar Biology. 45 (3): 449–463. Bibcode:2022PoBio..45..449J. doi:10.1007/s00300-022-03008-5. ISSN 1432-2056. S2CID 246176509.

- ^ Garde, Eva; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Hansen, Steen H.; Nachman, Gösta; Forchhammer, Mads C. (28 February 2007). "Age-specific growth and remarkable longevity in narwhals (Monodon monoceros) from West Greenland as estimated by aspartic acid racemization". Journal of Mammalogy. 88 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1644/06-mamm-a-056r.1. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ a b Laidre, Kristin; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Stern, Harry; Richard, Pierre (1 January 2012). "Unusual narwhal sea ice entrapments and delayed autumn freeze-up trends". Polar Biology. 35 (1): 149–154. Bibcode:2012PoBio..35..149L. doi:10.1007/s00300-011-1036-8. ISSN 1432-2056. S2CID 253807718.

- ^ Porsild, Morten P. (1918). "On "savssats": a crowding of Arctic animals at holes in the sea Ice". Geographical Review. 6 (3): 215–228. Bibcode:1918GeoRv...6..215P. doi:10.2307/207815. ISSN 0016-7428. JSTOR 207815.

- ^ William F. Perrin; Bernd Wursig; J. G. M. 'Hans' Thewissen, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 929–930. ISBN 978-0-080-91993-5. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Ferguson, Steven H.; Higdon, Jeff W.; Westdal, Kristin H. (30 January 2012). "Prey items and predation behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Nunavut, Canada based on Inuit hunter interviews". Aquatic Biosystems. 8 (1): 3. Bibcode:2012AqBio...8....3F. doi:10.1186/2046-9063-8-3. ISSN 2046-9063. PMC 3310332. PMID 22520955.

- ^ "Invasion of the killer whales: killer whales attack pod of narwhal". Public Broadcasting System. 19 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ "Fact sheet narwhal and climate change CITES" (PDF). cms.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Witting, Lars (10 April 2017), Meta population modelling of narwhals in East Canada and West Greenland–2017, doi:10.1101/059691, S2CID 89062294, retrieved 14 February 2024

- ^ a b c d e Hoover, C.; Bailey, M. L.; Higdon, J.; Ferguson, S. H.; Sumaila, R. (2013). "Estimating the economic value of narwhal and beluga hunts in Hudson Bay, Nunavut". Arctic. Arctic Institute of North America. 66 (1): 1–16. doi:10.14430/arctic4261. ISSN 0004-0843.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (19 August 2009). "Inuit hunters help scientists track narwhals". NPR.org. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b Heide-Jørgensen, Mads P. (22 April 1994). "Distribution, exploitation and population status of white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in West Greenland". Meddelelser om Grønland. Bioscience. 39: 135–149. doi:10.7146/mogbiosci.v39.142541. ISSN 0106-1054.

- ^ a b Wagemann, R.; Snow, N. B.; Lutz, A.; Scott, D. P. (9 December 1983). "Heavy metals in tissues and organs of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros)". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 40 (S2): s206–s214. doi:10.1139/f83-326. ISSN 0706-652X.

- ^ Bouquegneau, Krishna Das; Debacker, Virginie; Pillet, Stéphane Jean-Marie (2003), "Heavy metals in marine mammals", Toxicology of Marine Mammals, CRC Press, pp. 147–179, doi:10.1201/9780203165577-11, ISBN 978-0-429-21746-3, retrieved 4 February 2024

- ^ a b Laidre, Kristin L.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (10 February 2011). "Life in the lead: extreme densities of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in the offshore pack ice". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 423: 269–278. Bibcode:2011MEPS..423..269L. doi:10.3354/meps08941. ISSN 0171-8630.

- ^ Laidre, Kristin L.; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter (February 2005). "Arctic sea ice trends and narwhal vulnerability". Biological Conservation. 121 (4): 509–517. Bibcode:2005BCons.121..509L. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.06.003. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Nielsen, Martin Reinhardt (1 August 2009). "Is climate change causing the increasing narwhal (Monodon monoceros) catches in Smith Sound, Greenland?". Polar Research. 28 (2): 238–245. doi:10.3402/polar.v28i2.6115. ISSN 1751-8369.

- ^ Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Hansen, Rikke Guldborg; Westdal, Kristin; Reeves, Randall R.; Mosbech, Anders (February 2013). "Narwhals and seismic exploration: is seismic noise increasing the risk of ice entrapments?". Biological Conservation. 158: 50–54. Bibcode:2013BCons.158...50H. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.005. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Blackwell, Susanna B.; Tervo, Outi M.; Samson, Adeline L.; Garde, Eva; Hansen, Rikke G.; Ngô, Manh Cu’ò’ng; Conrad, Alexander S.; Trinhammer, Per; Schmidt, Hans C.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Williams, Terrie M.; Ditlevsen, Susanne (2021). "Behavioral response study on seismic airgun and vessel exposures in narwhals". Frontiers in Marine Science. 8. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.658173. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Bastian, Dawn Elaine; Mitchell, Judy K. (2004). Handbook of Native American Mythology. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 54–55. ISBN 1-851-09533-0.

- ^ a b c Pluskowski, Aleksander (January 2004). "Narwhals or unicorns? Exotic animals as material culture in medieval Europe". European Journal of Archaeology. 7 (3): 291–313. doi:10.1177/1461957104056505. ISSN 1461-9571. S2CID 162878182.

- ^ 다스톤, 로레인과 파크, 캐서린 (2001). 경이와 자연 훈장, 1150–1750. ISBN 0-942299-91-4.

- ^ Dugmore, Andrew J.; Keller, Christian; McGovern, Thomas H. (6 February 2007). "Norse Greenland settlement: reflections on climate change, trade, and the contrasting fates of human settlements in the North Atlantic islands". Arctic Anthropology. 44 (1): 12–36. doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0038. ISSN 0066-6939. PMID 21847839. S2CID 10030083.

- ^ Dectot, Xavier (October 2018). "When ivory came from the seas. On some traits of the trade of raw and carved sea-mammal ivories in the Middle Ages". Anthropozoologica. 53 (1): 159–174. doi:10.5252/anthropozoologica2018v53a14. ISSN 0761-3032. S2CID 135259639.

- ^ Schmölcke, Ulrich (December 2022). "What about exotic species? Significance of remains of strange and alien animals in the Baltic Sea region, focusing on the period from the Viking Age to high medieval times (800–1300 CE)". Heritage. 5 (4): 3864–3880. doi:10.3390/heritage5040199. ISSN 2571-9408.

- ^ Berger, Miriam (30 November 2019). "The narwhal tusk has a wondrous and mystical history. A new chapter was added on London Bridge". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Châtelet-Lange, Liliane; Franciscond, Renate (March 1968). "The Grotto of the unicorn and the harden of the Villa Di Castello". The Art Bulletin. 50 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1080/00043079.1968.10789120. ISSN 0004-3079.

- ^ Nweeia, Martin T. (15 February 2024). "Biology and cultural Importance of the narwhal". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 12: 187–208. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-021122-112307. ISSN 2165-8110. PMID 38358838.

- ^ Sherman, Josepha (2015). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Routledge. p. 476. ISBN 978-1-31-745938-5. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Regard, Frédéric, ed. (2014), "Ice and Eskimos: Dealing With a New Otherness", The Quest for the Northwest Passage: Knowledge, Nation and Empire, 1576–1806, Pickering & Chatto, ISBN 978-1-84893-270-8, retrieved 13 February 2024

- ^ Duffin, Christopher J. (January 2017). "'Fish', fossil and fake: medicinal unicorn horn". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 452 (1): 211–259. Bibcode:2017GSLSP.452..211D. doi:10.1144/SP452.16. ISSN 0305-8719. S2CID 133366872.

- ^ Wexler, Philip (2017). Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Academic Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-12-809559-1.

- ^ Rochelandet, Brigitte (2003). Monstres et merveilles de Franche-Comté: fées, fantômes et dragons (in French). Editions Cabédita. p. 131. ISBN 978-2-88295-400-8.

- ^ Robertson, W. G. Aitchison (1926). "The Use of the Unicorn's Horn, Coral and Stones in Medicine". Annals of Medical History. 8 (3): 240–248. ISSN 0743-3131. PMC 7946245. PMID 33944492.

- ^ Meares, Hadley (16 April 2019). "How 'unicorn horns' became the poison antidote of choice for paranoid royals". HISTORY. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

추가읽기

- Ford, John; Ford, Deborah (March 1986). "Narwhal: unicorn of the Arctic seas". National Geographic. Vol. 169, no. 3. pp. 354–363. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Groc, Isabelle (12 February 2014). "The world's weirdest whale: hunt for the sea unicorn". New Scientist. Retrieved 10 February 2024.