트랜스베이 튜브

Transbay Tube Transbay 튜브 보기 | |

| 개요 | |

|---|---|

| 라인 | |

| 위치 | 미국 캘리포니아 주 샌프란시스코 만 |

| 좌표 | Oakland 포털: 37°48′32″N 122°18′58″w / 37.80889°N 122.31611°W |

| 시스템 | 베이 지역 급행열차 |

| 시작 | 샌프란시스코 마켓 스트리트 지하철 |

| 끝 | 오클랜드 웨스트오클랜드 역 |

| No. 역의 | 없음 |

| 작전 | |

| 열린 | 1974년 9월 16일 ([1] |

| 소유자 | 샌프란시스코 만 지역 급행 교통 지구 |

| 연산자 | 샌프란시스코 만 지역 급행 교통 지구 |

| 캐릭터 | 급행열차 |

| 기술 | |

| 선 길이 | 3.6mi(5.8km) |

| No. 트랙이 있는 | 2 |

| 트랙 게이지 | 5ft 6인치(1,676mm) 인도 게이지 |

| 전기화됨 | 3차 레일, 1000V DC |

| 작동 속도 | 130km/h 80mph |

| 최고 고도 | 해수면 |

| 최저 고도 | 해수면 아래 135피트(41m) |

트랜스베이 튜브(Transbay Tube)는 베이 에어리어 래피드 트랜짓(Bay Area Rapid Transitation)의 4개 트랜스베이 노선을 샌프란시스코 만 아래로 샌프란시스코와 캘리포니아 오클랜드 사이에 실어 나르는 해저 철도 터널이다. 이 튜브는 길이가 3.6마일(5.8km)이며, 쌍둥이의 지루한 터널에 부착되어 있다.[2] 가장 가까운 역 사이의 철도 지하 구간(지하철 1개)은 총 길이 10km(6마일)이다. 이 관의 최대 깊이는 해발 135피트(41m)이다.

Transbay tube는 물에 잠긴 튜브 기법을 사용하여 57개 구역에 육지에 건설되어 현장으로 운반된 다음 주로 모래와 자갈로 옆면을 포장하여 물에 잠기고 바닥에 고정했다.[3]

1974년 문을 연 이 터널은 원래 BART 계획의 마지막 구간이었다.[4] 베리에사-리치몬드 노선을 제외한 모든 BART 노선이 트랜스베이 튜브를 통해 운행되고 있어 여객 및 열차 교통 면에서 시스템에서 가장 혼잡한 구간 중 하나이다. 출퇴근 피크 시간에는 시간당 28,000명 이상의 승객이 2.5분 정도의 짧은 통로로 터널을[5] 통과한다.[6] BART 열차는 배관 내에서 시간당 거의 80마일(130km/h)의 최고 속도에 도달하는데, 이는 이 시스템의 다른 곳에서 발견되는 평균 시속 36마일(h)의 두 배 이상이다.[7]

구상 및 시공

초기 개념

샌프란시스코만을 가로지르는 해저 철도 터널의 아이디어는 1872년 5월 12일 샌프란시스코 별난 노튼 황제가 발표한 선언문에서 제안하였다.[8][9] 노턴 황제는 1872년 9월 17일 두 번째 포고문을 발표하여, 자신의 초기 포고를 소홀히 한 오클랜드와 샌프란시스코의 도시 지도자들을 체포하겠다고 위협했다.[10]

이 아이디어에 대한 공식적인 고려는 1920년 10월 파나마 운하의 건설자인 조지 워싱턴 고탈스 소장에 의해 처음 주어졌다. Goethals가 제안한 튜브의 정렬은 오늘날의 Transbay Tube와 거의 정확하게 동일하며, 완성된 Transbay Tube의 지진 설계 측면의 일부를 예상하는 베이 머드 위에 건설할 것을 요구하였다. Goethals의 제안은 최대 5천만 달러(2020년 7억 2,500만 달러에 상당)의 비용이 들 것으로 추정되었다.[11] 1921년 7월 알라메다 동쪽에 위치한 샌프란시스코의 미션 록과 포트로 포인트 사이에 제안된 남방 크로싱의 정렬에 더 가까운 J. Vipond Davies와 Ralph Modjeski에 의해 경쟁적인 브리지 앤 터널 제안이 진전되었다. 데이비스와 모데스키는 전기 철도 교통을 위한 전용 터널의 아이디어를 간접적으로 지지하면서, 오랜 기간 결합된 자동차와 철도 터널에서 발생할 환기 문제에 대해 비판적이었다.[12] 데이비스와 모데스키의 제안은 1921년 10월에 베이를 횡단하기 위해 제안된 12개의 다른 프로젝트들과 함께 참여했는데, 이 프로젝트들 중 몇몇은 긴 터널을 통한 철도 서비스를 특징으로 한다.[13][14]

1947년 육해군 합동위원회는 당시 10년 된 베이 브리지의 자동차 정체 해소를 위한 수단으로 해저 튜브를 추천했다.[15] 이 권고안은 르베르 계획의 실현 가능성을 결정하기 위해 수행된 보고서에서 발표되었다.[16][17]

건설

1959년부터 지진 연구가 시작되었는데, 1960년과 1964년에 지루한 시험 프로그램, 베이 층에 지진 기록 시스템을 설치하는 등 다양한 연구가 시작되었다. 이 튜브의 경로는 예비 조사 결과 연속적인 암반 프로파일을 식별할 수 없어 베이 층의 보다 정밀한 지루함과 탐색이 필요하게 되자 수정되었다.[18] 이 경로는 가능한 한 암반을 피하기 위해 의도적으로 선택되었다. 그래서 관은 구부러지는 응력을 피하면서 자유롭게 구부러질 수 있었다.[19]

설계 개념과 경로 정렬은 1960년 7월까지 완료되었다.[20] 1961년 보고서는 트랜스베이 튜브의 비용을 미화 132,720,000달러(2020년 1,149,400,000달러와 동일)로 추정했다.[21] 1965년 이 관에 공사를 시작하였으며, 1969년 4월 3일 최종 구간을 내린 후 공사가 완료되었다.[22] BART는 최종 구간의 배치를 기념하기 위해 동상으로 만든 알루미늄 동전을 판매했다.[23] 설치되기 전 1969년 11월 9일 관람객들이 소량 구간을 거닐 수 있도록 튜브를 개방하였다.[24] 열차 운행에 필요한 선로와 전기화는 1973년에 완료되었으며, 자동배차시스템에 관한 캘리포니아 공공시설위원회의 우려를 불식시킨 후 원래 계획되었던 완공일로부터 5년 [25]후인 1974년 9월 16일에 개통되었다.[26] 첫 번째 시험운행은 1973년 8월 10일 자동제어된 열차에 의해 수행되었다. 222호 열차는 웨스트오클랜드에서 몽고메리 스트리트까지 시속 68~70마일(109~113km/시)으로 7분 만에 달려 최고속도 130km/시속 80마일(시속 130km)로 6분 만에 회항해 바트 관계자, 고위인사, 기자 등 100여 명의 승객이 탑승했다.[27]

이 터널은 깊이 2피트(0.61m)의 자갈 토대가 있는 폭 18m의 참호 안에 설치된다. 레이저는 참호의 준설과 자갈기초의 안착을 유도하기 위해 사용되었으며, 참호의 경우 3인치(76mm), 기초의 경우 1.8인치(46mm) 이내의 경로 정확도를 유지했다.[28] 참호 건설은 베이로부터 5,600,000 입방 야드(4,300,000 m3)의 자재를 준설해야 했다.[29]

이[30][31] 구조물은 70부두 베들레헴 철강조선소의 육지에 건설된 57개 개별 구간으로 대형 카타마란 바지선에 의해 만으로 견인된 것이다.[32] 강철 포탄이 완성된 후, 방수 격벽이 설치되었고 콘크리트를 부어 두께 2.3피트(0.70m)의 내부 벽과 트랙 베드를 형성하였다. 그리고 나서 그것들은 제자리에 띄워졌고(그들이 앉을 자리 위에 위치), 바지선은 베이 마루에 묶여 일시적인 장력 다리 플랫폼 역할을 했다.[33] 이 구간은 500t(450t)의 자갈로 밸러스트한 뒤 부드러운 흙과 진흙, 자갈이 가득한 참호로 내려 베이 바닥을 따라 수평을 이루었다. 일단 이 구간이 마련되면 잠수부들이 이 구간을 이미 물속에 놓여 있던 구간과 연결했고, 배치된 구간 사이의 격벽은 제거되고 측면에 모래와 자갈의 보호층이 채워졌다.[23][32] 베이의 소금물에서 나오는 부식작용에 저항하기 위해 음극방지가 제공되었다.[29]

이 프로젝트는 1970년에 약 1억 8천만 달러(2019년에는[34] 9억 3천 3백만 달러에 상당)가 들었고,[35][36] 그 중 9천만 달러는 건설에 쓰였으며, 나머지는 철도, 전기화, 환기, 열차 제어 시스템에 쓰였다.[37]

배열

튜브의 서쪽 종착역은 베이 브리지 북쪽 페리 빌딩 근처의 시내 마켓 스트리트 지하철과 직접 연결된다. 이 튜브는 샌프란시스코 반도와 예르바 부에나 섬 사이의 베이 브리지 서쪽 구간 아래를 가로지르며, 880번 주간고속도로 서쪽 7번가를 따라 오클랜드에서 나온다.[38][citation needed]

튜브의 섹션은 57개인데, 각 섹션의 길이는 273~336피트(83~102m)이다.[28] 각 구역의 평균 길이는 터널의 보어를 따라 측정된 328피트(100m)이며, 구역의 폭은 48피트(15m)이고, 높이는 24피트(7.3m)이며, 무게는 각각 약 10,000개의 단톤(9,100t)이다.[22] 경로에 따라 15개의 튜브 구간을 수평으로 곡선 처리하였고, 4개는 수직으로 곡선 처리하였으며, 2개는 수평과 수직으로 곡선 처리하였으며, 나머지 36개는 직선이었다.[28] 이 튜브의 각 섹션은 9,000,000달러(2020년 635,150,000달러)의 건설 계약에 근거하여 약 150만 달러(2020년 10,590,000달러 상당)의 비용이 들었다.[39] 강철 껍질은 두께가 0.625인치(15.9mm)[40]로 자체 무게를 지탱하고 후프 스트레스에 저항하기에 충분한 힘을 가지고 있다. 외부 컨설턴트인 랄프 브레이젤튼 펙 교수는 프로젝트 엔지니어 톰 쿠젤에게 흙 하중이 자연스럽게 아치를 형성하기 때문에 얇은 껍질이 적절하다고 설득했다.[19]

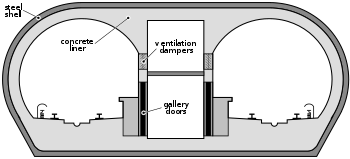

튜브는 2개의 터널과 중앙 유지 관리/보행 갤러리로 구성되어 있다. 각 터널은 보어 중심선에서 바깥쪽을 향해 8인치(200 mm)의 선로 중심선 간격띄우기를 가진 지름 약 5.2 m의 보어를 가지고 있다. 터널은 화재를 위한 가압수선을 포함한 상부 화랑의 유지관리 및 제어 장비를 갖춘 화랑 옆을 향하고 있다. 각 터널에는 하단 갤러리로 56개의 문이 열려 있으며, 약 330피트(100m) 간격으로 튜브의 샌프란시스코 쪽에서 연속적으로 번호가 매겨져 있다. 도어는 갤러리 쪽에서 잠겨 있으며 터널에서 비상 하드웨어를 통해 내부(갤러리 도어)로 열 수 있다. 문 사이에 터널은 갤러리 공간에 인접한 2.5피트(0.76m)의 좁은 통로를 가지고 있다.[41]

갤러리 공간의 상단 부분은 도관으로도 사용되어 강제 순환 시 분당 30만 입방피트(8,500m3/min)의 공기를 이동시킨다.[42] 터널은 샌프란시스코와 오클랜드의 끝에서 대기 중으로 방출되고 (상부 갤러리를 통해) 3번째 문마다 6피트(1.8m) 길이, 3피트(0.91m) 높이까지 원격 작동 댐퍼로 서로 방출된다.[41]

튜브의 각 끝은 특허 받은 슬라이딩 지진 이음매로[43] 환기구 구조물에 고정되어 6도 자유도(변환 및 3축 정도 회전)가 가능하다. 설계 시 이음매는 튜브 축을 따라 최대 4.25인치(108mm), 수직 또는 횡방향으로 최대 6.75인치(171mm)까지 이동할 수 있다.[44] 페리빌딩 뒤편 부두의 환승구조물(벤트) 꼭대기에 식당이 들어섰다.[45]

내진 보강

Transbay Tube는 외관과 내부를 모두 보강해야 한다. 2004년에는 총 지진 복구 비용이 3억 3천만 달러(2020년 452,200만 달러에 상당)로 추산되었다.[46]

1989년 로마 프리에타 지진 발생 후 주지사 위원회의 권고로 의뢰된 1991년 연구는 지진 관절이 "다음 지진 이후에도 거의 온전하고 기능적으로 유지될 것"[48]이라는 것을 발견했다.[47] 그러나 참호 안과 로마 프리에타 지진으로 인해 지진관절의 허용 이동량이 1.5인치(38mm)로 줄어들었다.[44][49]

1991년 연구는 2002년에 발표된 BART 지진 취약성 연구에 뒤이어 발표되었는데, 이 연구는 관 주위에 채워진 채움물이 강한 지진 동안 토양 액화 작용을 일으키기 쉬우며, 부력 중공관이 고정장치에서 이탈하거나 미끄럼틀의 용량을 초과하는 움직임을 유발할 수 있다는 결론을 내렸다.딩딩 [44][50][51]지진관절 보강 작업에서는 충전을 압축하여 더 조밀하고 액화되기 쉬운 상태로 만들어야 했다.[46] 컴팩션은 2006년 여름, 오클랜드 항구에 속해있는 관의 동쪽 끝에서 시작되었다.[52] 2010년 논문은 잠재적인 액화 메커니즘의 모델 시험에 근거하여 액화 때문에 튜브가 상승할 거리를 제한한다고 결론 내리고, 압축 노력의 정당성에 의문을 제기했다.[53][54]

튜브 내부에서는 2013년 3월 BART가 지진 발생 시 횡방향 이동으로부터 보호하기 위해 보강이 가장 필요한 튜브 내부 여러 곳에 무거운 철판을 설치하는 것을 포함하는 대대적인 개보수 시책을 시작했다. 4-숏톤(3.6t) 두께의 2.5인치(64mm) 두께의 판을 다룰 수 있도록 차량을 맞춤 제작했으며, 일단 제자리에 올리면 판을 기존 콘크리트 벽에 볼트로 고정시켜 끝에서 끝까지 용접했다.[55] 7,735,000달러(2020년 8,719,000달러 상당)의 계약이 캘리포니아 엔지니어링 계약자에게 주어졌다.[56] 2013년 이 작업을 완료하기 위해 BART는 주 중반(화요일, 수요일, 목요일)에 튜브의 2개 보어 중 1개를 닫아 15~20분이 지연됐다. 당초 약 14개월 정도 지속될 것으로 추정됐던 이 공사는 8개월 만에 2013년 12월 완공됐다.[57][58]

2016년 12월 BART는 2억6700만 달러(2020년 28억7920만 달러 상당)의 내진 보강 공사를 추가로 수행하기 위한 계약을 체결했다. 이 단계에서는 최악의 경우 기존 펌프가 적절하지 않기 때문에 튜브가 침수될 가능성을 줄이기 위해 새로운 강철 라이너와 고용량 펌프가 설치될 것이다. 작업은 2018년 여름에 시작될 예정이었고 완성하는데 2년 이상이 걸릴 예정이다. 튜브를 통한 서비스는 서비스 요일의 첫 번째 시간과 마지막 세 시간 동안 감소하거나 제거될 것이다.[59]

사건 및 문제

1979년 1월 화재

1979년 1월 17일 오후 6시경 샌프란시스코행 7량 열차(열차 117호)에서 튜브를 통과하던 중 전기 화재가 발생했다.[60][61] 소방관 1명(Lt. 오클랜드 소방국의 윌리엄 엘리엇(50)은 화재 진압 과정에서 연기와 유독성 흄 흡입으로 사망했다[62]. 피해 열차에 타고 있던 승객 40명과 BART 직원 2명은 반대 방향으로 지나가는 다른 열차에 의해 구조됐다.[41][63] 1979년 1월 화재 당시 관찰된 부실한 소통과 조정은 소방협회 중계산업 지침(NFPA 130, 고정가이드웨이 교통 및 여객철도 시스템 표준)을 개발하는 데 핵심적인 역할을 했다.[60]

화재 원인은 117호 열차에서 누전이 발생한 것으로 추적되었다. 5호차와 6호차의 컬렉터 슈즈 조립부는 앞서 열차(363호선)에서 떨어진 선로전환기 커버를 들이받고 고장 나 누전과 화재가 발생했다.[41]

이날 오전 샌프란시스코행 10량 열차 363호는 오후 4시 30분쯤 트랜스베이 튜브에 비상 정차해 연기와 화재 가능성을 보고했었다. 외부 점검이 없는 문제해결 결과 363호는 6번과 8번 차량의 탈선봉이 파손됐고 9번 차량의 주차 브레이크가 걸려 있는 것으로 드러났다. 탈선 바 회로를 청소하고 주차 브레이크를 수동으로 해제한 후 363호를 해제하여 진행을 진행시켰고, 달리 시티의 라인 끝에 도달하자마자 점검을 위해 서비스에서 제외되었다.[41]

363호 전동차는 전산화된 중앙통제시스템이 아닌 탑재기술자가 열차를 운행하는 '도로 매뉴얼' 모드로 운행하도록 급파됐다. 그 열차는 363번 선로가 정차한 인근 선로 사이에 있는 탈선봉 파편들을 보았다고 보도했지만 선로는 여전히 선명하고 운행이 가능한 상태였습니다. 곧바로 뒤따르던 열차도 '도로 매뉴얼'로 운행했지만 후속 열차는 363호 이후 열 번째인 117호 열차를 포함해 자동 모드로 튜브를 통해 투입됐다.[41]

117번은 트랜스베이 튜브에 진입한 직후인 오후 6시 6분에 비상정류장에 도착했는데, 운영자가 짙은 연기를 신고해 정확한 위치를 파악하지 못했다. 중앙 운영은 3차 레일의 전원을 차단했지만, 불타는 차로부터 열차의 리드 부분을 분리하기 위한 노력으로 40초 후에 그것을 복구했다. 이는 성공하지 못했고, 오후 6시 8분 환기팬을 켜 연기를 제거하려 했고, 오후 6시 15분 세 번째 레일이 다시 전원이 꺼졌다. 열차에 타고 있던 바트 감독관이 시각장애인 1명을 포함해 선두차에 탑승한 승객들을 모으는 데 일조했다.[41]

오클랜드 소방서는 웨스트오클랜드 역에 대응해 소방관 9명과 BART 경찰관 2명이 '도로 매뉴얼'로 달리는 900호 열차에 탑승했다. 900번은 보조 박스 커버와 탈선 바를 선로에서 제거하기 위해 튜브 안으로 약 1마일(1.6km) 떨어진 곳에서 멈춰야 했고, 결국 117번 뒤쪽으로 약 200피트(61m) 떨어진 곳에서 멈춰섰는데, 열차 운전자는 후미차가 짙은 검은 연기와 함께 불이 났다고 신고했다. 117호에 이르자 대응요원들은 연기에 의해 분리되었고, 경찰관 1명과 소방관 7명이 터널 사이 갤러리로 진입했으며, 나머지 7명은 연기에 의해 900호로 복귀할 수 밖에 없었다. 그러나 화랑 안의 일행은 다른 사람들이 따라올 수 있도록 터널의 문을 열어 놓고 있었다.[41]

1000명 이상의 승객이 탑승한 111호 열차는 마지막 샌프란시스코 정류장인 엠바르카데로에서 정차해 있었다. 오후 6시 21분 111번은 자동모드로 117호 사고지점에 인접한 동행터널로 진입해 연기가 가득 찬 서행터널을 따라 갤러리로 진입해 있던 승객들을 구조했다. 구조된 승객들이 111호에 탑승한 뒤 소방관들은 오후 6시59분 중앙파견대에 승객 전원이 117번에서 111번으로 이동했음을 알리며 117번 승객을 병원으로 이송하기 위해 곧바로 웨스트오클랜드로 자동 이송됐으나 가속과 동시에 연기가 뿜어져 나왔다.개방된 문을 통해 갤러리로 들어가는 서쪽 방향 터널을 제외한다. 이 무렵, 더 많은 소방관들이 오클랜드 환기구 구조물을 통해 30분 분량의 보급품을 휴대형 공기 마스크를 착용하고 응답했다.[41] 갤러리 쪽에서 동쪽 방향 터널로 통하는 문이 잠겨 있었고, 화랑에 연기가 가득 차 키홀이 가려져 소방대원들이 동쪽 방향 터널로 대피하지 못했다.[60]

출발하는 111호에서 나온 징병기의 힘으로 화랑의 소방대원들이 쓰러졌고, 소방대원들은 짙은 연기를 뚫고 화랑의 한 줄로 된 인간 사슬로서 동쪽으로 나아가기 시작했다. 이때쯤이면 그들의 휴대용 공기마스크는 바닥이 나기 시작했고, 중위는 낮았다. 윌리엄 엘리엇은 동료 소방관들의 도움을 필요로 하면서 어려움을 겪기 시작했다. 터널의 맑은 구간에 이르자 웨스트오클랜드에서 또 다른 열차가 '도로 매뉴얼'로 출동해 소방관들을 구조했다. 구조 열차가 웨스트 오클랜드로 돌아온 후, 소방관들은 치료를 위해 지역 병원으로 옮겨졌다. 엘리엇은 산소공급량이 다 떨어졌고, 연기 흡입과 청산가리 중독으로 사망했다.[41]

화재는 아직 완전히 진화되지는 않았지만 오후 10시 45분 진압을 선언하였다. 다음날인 1월 18일 오후 6시쯤, 오클랜드 소방관들은 BART의 창고 야적장에 있는 내장이 뚫린 열차 안에서 폭발에 대응했다.[60] BART는 튜브 서비스 손실로 인해 100만 달러(2020년 357만 달러)의 수익 손실과 더불어 튜브 수리 및 안전 개선에 110만 달러(2020년 392만 달러 상당)를 지출할 것이다.[64]

BART는 2월까지 샌프란시스코와 오클랜드 소방서장에게 새로운 대피 계획을 제안했으나,[64] 1979년 4월에야 Transbay Tube를 통한 BART 서비스가 재개되었고, 캘리포니아 공공시설 위원 리처드 D가 참여하였다. 자갈 경고는 "그 서비스를 이용하는 바트의 고객들은 [서비스를 재개하기 위한] 즉석 주문이 어떤 식으로든 안전한 서비스를 보장하지 않는다는 것을 충분히 알아야 한다"[65]고 말했다. 오클랜드 소방서와 샌프란시스코 소방서는 모두 BART 관계자들이 비상사태에 대한 통제권을 소방서에 넘기지 않았다고 비난했다.[60]

지진

예방책으로서, BART의 비상계획은 가장 가까운 역으로 가는 Transbay Tube나 Berkeley Hills Tunnel에 있는 열차를 제외하고, 지진이 일어나는 동안 열차가 멈추도록 지시한다. 그런 다음 라인 손상 여부를 검사하고, 손상이 발견되지 않으면 정상 작동을 재개한다.[66]

현재까지 가장 규모가 큰 것은 1989년 로마 프리에타 지진이다. 1989년의 지진 동안, 운전자는 뚜렷한 움직임이 없다고 보고했지만, 튜브를 통과하는 열차는 멈추라는 명령을 받았다.[67] 점검 결과, 이 튜브는 안전한 것으로 확인되었고, 6시간 후에 다시 열렸으며, 지진 발생 12시간 후에 시스템 전체에 걸쳐 정기적인 서비스가 재개되었다.[67][68] 이 사건으로 많은 지역 고속도로가 파손되었고, 동부간 트러스 구간에서 상층 데크 구간이 하층 데크 위로 떨어져 베이 브리지가 한 달 동안 폐쇄되면서 트랜스베이 튜브는 샌프란시스코와 오클랜드를 잇는 유일한 직항로였다.[47]

보행자

2012년[69] 10월과 2013년 8월에는 보행자들이 엠바르카데로역을 통해 튜브에 진입해 환승 서비스 중단과 지연이 발생했다.[70] 2016년 12월 말 한 남성이 엠바르카데로 역의 포털을 통해 튜브에 들어가 1시간 넘게 머물렀고, 교통경찰이 그를 수색하는 동안 열차는 수동 모드로 튜브를 통해 느린 속도로 계속 이동했다.[71]

장비 고장

트란스베이 튜브에 열차가 갇힌 뒤 여러 차례 운행이 차질을 빚었는데, 이는 부분적으로 노후화된 장비 탓이다.[72] 1979년 화재 외에도 튜브를 통해 이동하던 중 열차가 갈라져 2010년 3월 연결기가 고장 나 자동 정지됐다.[73] 2014년 9월 튜브 내에서 두 대의 정비 차량이 충돌해 선로 한 구간이 파손되고 BART 트래픽이 단일 선로에 의존할 수밖에 없었다.[74] 2015년 1월, 브레이크가 부주의로 차량에 걸려 열차가 튜브에 멈춰야 했다.[75] 2016년 12월 한 열차는 튜브에 정차한 뒤 수동 모드로 전환해 감속 운행해야 했고,[76] 2017년 4월 또 다른 결함 브레이크는 튜브에 강제로 정차해야 했다.[77]

잡음

샌프란시스코 크로니클의 2010년 조사에 따르면, 트랜스베이 튜브는 BART 시스템에서 가장 시끄러운 부분으로, 열차 내부의 음압 수준이 100데시벨(잭해머와 유사함)에 달한다.[78] 2008년 비디오 게임 데드 스페이스에서는 터널의 녹음이 산업 소음으로 사용되었다.[79] BART에 따르면 "반쉬, 부엉이, 또는 닥터 후스 타디스가 아무렇게나 달린다"는 소음은 콘크리트 울타리와 샌프란시스코-오클랜드 베이 다리 아래 터널이 교차할 때 트랙이 곡선으로 되어 높은 음의 끽끽 소리를 내는 것으로 악화된다.[78] 2015년, 6,500피트를 교체하고 3마일의 레일을 튜브에 갈아서 (스무팅)한 후, BART는 승차자들로부터 소음 감소와 긍정적인 피드백을 보고했다.[80]

해상교통

만을 통과하는 선박 교통은 닻을 내릴 때 튜브의 음극 보호 시스템에 사용되는 양극을 손상시킬 수 있다. 튜브를 둘러싸고 있는 충전된 참호에서 양극이 돌출되기 때문에 손상에 더 취약하다. 해양 교통은 튜브 상공에서 닻을 내리는 것이 제한되지만, BART는 양극 손상에 대한 정기적인 검사를 실시한다.[81]

튜브는 2014년 1월 31일 오전 8시 45분, 표류 화물선이 위치를 유지하기 위해 근처에 정박해 잠시 폐쇄되었다. 해경은 선박 위치 기준으로 오전 11시 55분 BART 관계자들에게 닻이 튜브에 가까이 있는 것으로 보인다고 통보해 검사가 진행되는 동안 약 20분간 튜브 서비스가 중단됐다. 손상은 발견되지 않았으며, 오후 12시 15분 튜브가 다시 열렸다. 항만 조종사들은 나중에 그 배가 관에서 남서쪽으로 1,200피트(370m) 떨어진 곳에 정박해 있었다고 지적했다.[82] 검문검사가 진행되는 동안 튜브를 통과하던 열차 두 대가 제자리에 멈춰 섰다. 열차가 15~20분 지연되면서 오후 1시쯤 정상 운행이 재개됐다.[40]

2017년 4월, 튜브 양극 정비를 위해 바트에서 일하던 데릭 바지선 '복수'가 늦은 겨울 폭풍 때 밤에 전복돼 침몰했다. 바지선은 트랜스베이 튜브를 덮은 채 위에서 쉬게 되었지만, 수송 작업에 지장을 주지는 않았다. 1차적인 우려는 디젤 연료의 누출 가능성이었고, 잠수부들은 하루 만에 누출을 막았다.[83]

미래

2007년, BART는 창립 50주년을 기념하면서 향후 50년 계획을 발표했다. 현재 터널을 2030년까지 가동할 수 있을 것으로 판단되면, 이 기관은 샌프란시스코 만 아래 별도의 Transbay Tube를 포함하여 기존 Transbay Tube와 평행하고 남쪽으로 운행할 계획이다. 제안된 4-bore 터널은 Transbay Transfer Center에 나타나 캘트레인과 계획된 캘리포니아 고속철도(CHSR) 시스템과의 연결 서비스를 제공할 것이다. 두 번째 튜브는 BART 열차를 위한 트랙 2개와 재래식/고속 레일용[84] 트랙 2개를 제공한다(BART 시스템과 재래식 미국 레일은 서로 다르고 호환되지 않는 레일 게이지를 사용하며 다른 안전 규정 세트에 따라 작동한다).

2018년, 캐피톨 코리더 통근 철도 서비스를 담당하는 BART와 CCJPA는 제안된 두 번째 건널목에 대한 가능한 정렬 선택권을 좁히기 위해 타당성 조사를 실시할 계획을 세우기 시작했다.[85][86] 이 연구는 캘트레인, CHSR, 캐피톨 코리더 및 잠재적으로 다른 철도 서비스에 대한 연결을 허용하기 위해 표준 궤간 철도 옵션을 계속 고려할 것이다.[86]

미디어에서

공사 기간 동안, 트랜스베이 튜브는 조지 루카스의 영화 THX 1138의 결말을 위한 촬영 장소로 잠깐 사용되기도 했다. 마지막 수직 상승은 실제로 카메라가 90° 회전하면서 불완전한(확정적으로 수평인) 트랜스베이 튜브에서 촬영되었다. 이 장면은 트랙 지지대 설치 전 촬영됐는데, 로버트 듀발 캐릭터가 노출된 철근들을 사다리 삼아 촬영했다.[citation needed]

테리 브룩스의 셰나라 시리즈인 '샤나라 연대기'의 텔레비전 각색은 부분적으로 베이 지역을 배경으로 하고 있으며, 주인공들이 트랜스베이 튜브를 통과하는 여정/질문 경로의 일부다.[87]

비디오 게임 Dead Space의 초기 섹션 중 하나는 트랜스베이 튜브를 통해 주행하면서 얻은 사운드 샘플을 특징으로 한다.[88][89]

참고 항목

- 키 시스템

- 리치먼드-샌 라파엘 다리: T.A.의 초기 제안. 토마시니는 샌프란시스코에서 올버니와 티부론 사이의 다리를 만나는 터널을 포함했다.

참조

- ^ "BART Tube Link Opens". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. AP. September 17, 1974. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "BART Transbay Tube & Transition Structure SC Solutions". www.scsolutions.com. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ "A History of BART: The Project Begins bart.gov". www.bart.gov. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ Strand, Robert (September 14, 1974). "San Francisco gets its space age underwater trains". The Dispatch. UPI. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "The Case for a Second Transbay Transit Crossing" (PDF). Bay Area Council Economic Institute. February 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 1, 2016.

- ^ Mallett, Zakhary (September 7, 2014). "2nd Transbay Tube needed to help keep BART on track". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Minton, Torri (September 17, 1984). "BART: It's not the system it set out to be". Spokane Chronicle. AP. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

Hitting speeds close to 80 mph only in the 3.6-mile tube under the bay, the trains average 36 mph for safety reasons, [BART spokesman Sy] Mouber said.

- ^ Norton I (June 15, 1872). "Proclamation". The Pacific Appeal. p. 1 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Believing Oakland Point to be the proper and only point of communication from this side of the Bay to San Francisco, we, Norton I, Dei gratia Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico, do hereby command the cities of Oakland and San Francisco to make an appropriation for paying the expense of a survey to determine the practicability of a tunnel under water; and if found practicable, that said tunnel be forthwith built for a railroad communication. Norton I. Given at Brooklyn the 12th day of May, 1812.

- ^ 브릿지 프로클라멘츠, 노턴 트러스트 황제.

- ^ Norton I (September 21, 1872). "Proclamation". The Pacific Appeal. p. 1 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Whereas, we issued our decree, ordering the citizens of San Francisco and Oakland to appropriate funds for the survey of a suspension bridge from Oakland Point via Goat Island; also for a tunnel; and to ascertain which is the best project; and whereas, the said citizens have hitherto neglected to notice our said decree; and whereas, we are determined our authority shall be fully respected; now, therefore, we do hereby command the arrest, by the army, of both the Boards of City Fathers, if they persist in neglecting our decrees. Given under our royal hand and seal, at San Francisco, this 17th day of September, 1872. NORTON 1.

- ^ "San Francisco Bay Bridge Project Revived by New Plans". Engineering News-Record. 87 (1): 16–17. July 7, 1921. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

Howe & Peters, consulting engineers of San Francisco, have been working for nearly two years as Pacific Coast representatives of George W. Goethals, in getting together data on the construction of a subway for both vehicular and rail traffic, which would connect the foot of Market St. with Oakland Mole. Tentative plans on this project, made public some months ago, call for a shield-driven concrete tube, similar to the type General Goethals recommended for the New York-New Jersey tube under the Hudson River.

Provision would be made for two decks, the upper for use of motor vehicles and the lower for electric trains. [...] The gradient would be kept below 3 per cent so freight could be handled easily. The depth of water along the route the tube would follow does not exceed 65 ft. and soundings taken at various points indicate that its entire length would be in blue mud. Not only would mud facilitate driving by the shield method, it is pointed out, but it would constitute a cushion to safeguard the tube from possible disalignment due to earthquake shocks.

[...]If the results of such a survey confirm the rough estimates, it is suggested that the construction of the entire 3.5-mi. concrete tube would be between $40,000,000 and $50,000,000. - ^ "Features of San Francisco Bay Bridge Report". Engineering News-Record. 87 (7): 268–269. August 18, 1921. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

Any high bridge between Yerba Buena Island and San Francisco would naturally land on Telegragh Hill [sic]. It would not only involve very long and costly spans, even if piers were permitted in the channel, but would land the traffic in a section of the city already quite congested, and from which a proper distribution would be impracticable. Any tunnel on this location would have to be constructed at great depth in an unknown rock formation, as the water depth is too great for tunneling under air pressure, and the length would consequently be so great as to involve an extremely difficult problem in ventilation for vehicular traffic. We there fore consider this plan as impracticable. Any continuous tunnel across the bay, on any location, while practicable for purely electrically operated railroad traffic, would involve most serious ventilation problems for vehicular traffic, and enormous expense if constructed for all classes of traffic.

- ^ "Thirteen Projects Submitted for San Francisco Bay Bridge". Engineering News-Record. 87 (18): 739. November 3, 1921. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Mel (1985). "ELEVEN: Seeds of Metropolitan Regionalism". The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective (Second ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-520-05510-1. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Bay Area Rapid Transit District (n.d.). "History of the Tube". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013.

- ^ H.Res529번길

- ^ Report of Joint Army-Navy Board on an additional crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Presidio of San Francisco, California. 1947.

- ^ Aisiks, E. G.; Tarshansky, I. W. (June 23–28, 1968). "Soil Studies for Seismic Design of San Francisco Transbay Tube". Vibration Effects of Earthquakes on Soils and Foundations (ASTM STP 450). Seventy-first Annual Meeting of the American Society for Testing and Materials. San Francisco, California: American Society for Testing and Materials. pp. 138–166. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Rogers, J. David; Peck, Ralph B. (2000). "Engineering Geology of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) System, 1964-75". Geolith. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel (1960). Trans-bay tube: engineering report (Report). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel (June 1961). Engineering Report to the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. p. 21. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

Use of a precast concrete tube with metal shell for the underwater crossing between shore points is recommended.

- ^ a b "Final Section Of Transit Tube Lowered Into San Francisco Bay". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. April 4, 1969. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "BART Tunnel Completion Moves Near". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. March 31, 1969. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "BART Tube Is Opened For Sunday Visitors". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. November 10, 1969. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Leavitt, Carrick (September 16, 1974). "After three year wait BART goes down the tube". Ellensburg Daily Record. UPI. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Bay Area Rapid Transit System to Open Last Link". The Times-News. AP. August 27, 1974. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Bay tube run made by BART". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. August 11, 1973. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Frobenius, P.K.; Robinson, W.S. (1996). "3: Tunnel Surveys and Alignment Control". In Bickel, John O.; Kuesel, Thomas R.; King, Elwyn H. (eds.). Tunnel Engineering Handbook (Second ed.). Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4613-8053-5. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Bay Tube is quake proof". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. January 12, 1978. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Ralph (2016). "History of Potrero Point Shipyards and Industry". Pier 70 San Francisco. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Bethlehem built section of the BART Tubes at Pier 70". Bethlehem Shipyard Museum. 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Walker, Mark (May 1971). "BART—The Way to Go for the '70s". Popular Science. New York, New York: Popular Science Publishing Company. 198 (5): 50–53, 134–135. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Gerwick Jr, Ben C. (2007). "5: Marine and Offshore Construction Equipment". Construction of Marine and Offshore Structures (Third ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0-8493-3052-0. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2020). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved September 22, 2020. 미국 국내총생산 디플레이터 수치는 Measurement Worth 시리즈를 따른다.

- ^ Godfrey Jr., Kneeland A. (December 1966). "Rapid Transit Renaissance". Civil Engineering. American Society of Civil Engineers. 36 (12): 28–33.

- ^ "Transit system safety studied". Lawrence Journal-World. AP. January 23, 1975. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Mayors open Transbay Tube". Lawrence Journal-World. AP. September 20, 1969. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Bay Tube Gets Longer". Reading Eagle. UPI. December 16, 1968. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Exclusive Club 120 Feet Deep Offshore In San Francisco Bay". Ellensburg Daily Record. UPI. March 12, 1969. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Bender, Kristin J.; Alund, Natalie Neysa (January 31, 2014). "BART: No damage after container ship's anchor drops near Transbay Tube". The Mercury News. San Jose, California. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. July 19, 1979. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Bay Area Rapid Transit System". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. July 24, 1997. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ 미국은 3517515, 워쇼, 로버트, 1970년 6월 30일에 발행된 "터널 건설 슬라이딩 어셈블리"를 파슨스 브린커호프 퀘이드 & 더글러스 주식회사에 할당하여 1968년 7월 17일에 발행했다.

- ^ a b c "Seismic retrofit for BART's Transbay tube". TunnelTalk. March 2004. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ Glover, Malcolm (October 16, 1980). "Ferry commuters set their sights on a motion picture's mirage". San Francisco Examiner. p. D2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Transbay Tube Earthquake retrofit keeps farmers market in place". Bay Area Rapid Transit (Press release). October 16, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Housner, George W. (May 1990). Competing Against Time: The Governor's Board of Inquiry on the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake (Report). State of California, Office of Planning and Research. pp. 19, 25, 36–37, 39. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

The impacts of the earthquake were much more than the loss of life and direct damage. The Bay Bridge is the principal transportation link between San Francisco and the East Bay. It was out of service for a [sic] over a month and caused substantial hardship as individuals and businesses accommodated themselves to its loss. [...] The most tragic impact of the earthquake was the life loss caused by the collapse of the Cypress Viaduct, while the most disruption was caused by the closure of the Bay Bridge for a month while it was repaired, leading to costly commute alternatives and probable economic losses. [...] On the other hand, the Board received reports of only very minor damage to the Golden Gate Bridge, which is founded on rock, and the BART Trans-bay Tube, which was specially engineered in the early 1960s to withstand earthquakes. [...] Two facts stand out: the importance of the Oakland–San Francisco link, and the volume of traffic borne by the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge—approximately double that of the Golden Gate Bridge, and almost equal to the combined traffic carried by all four other bridges. For automobile traffic, the Golden Gate and Bay bridges are essentially nonredundant systems, with alternative routes via the other bridges being time consuming to a level that seriously impacts commercial and institutional productivity. [...] The critical role played by the BART Trans-bay Tube in cross-bay transportation is clear, as is the fact that the South Bay bridges (San Mateo and Dumbarton) accommodated most of the redistribution of vehicular traffic. [...] Engineering studies should be instigated of the Golden Gate and San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridges, of the BART system, and of other important transportation structures throughout the State that are sufficiently detailed to reveal any possible weak links in their seimic resisting systems that could result in collapse or prolonged closure.

- ^ Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. (November 1991). Transbay Tube Seismic Joints Post-Earthquake Evaluation (Report). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (April 17, 2004). "SAN FRANCISCO - OAKLAND / BART warns of possible leaks in Transbay Tube in big quake". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Bechtel Infrastructure Corporation; Howard, Needles, Tammen & Bergendorff (2002). BART Seismic Vulnerability Study (Report). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved September 7, 2016.CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크)

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (April 17, 2004). "SAN FRANCISCO - OAKLAND / BART warns of possible leaks in Transbay Tube in big quake". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "BART awards first major construction contract to earthquake strengthen the Transbay Tube". Bay Area Rapid Transit (Press release). October 16, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Chou, J.C.; Kutter, B.L.; Travasarou, T.; Chacko, J.M. (August 2011). "Centrifuge Modeling of Seismically Induced Uplift for the BART Transbay Tube". Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. American Society of Civil Engineers. 137 (8): 754–765. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000489.

- ^ "Earthquake Safety Program Technical Information". Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Jordan, Melissa (March 20, 2013). "Late-night work over next 14 months will strengthen Transbay Tube against a quake". Bay Area Rapid Transit (Press release). Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ "Next stage of Transbay Tube retrofit set to launch". Bay Area Rapid Transit (Press release). January 26, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ "Transbay Tube Retrofit Work Wraps Up Early Ending Late Night Single Tracking" (Press release). Bay Area Rapid Transit District. December 2, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (December 2, 2013). "Transbay Tube retrofit, and late-night delays, end". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (December 1, 2016). "Commuters beware: BART has 2-year plan to strengthen Transbay Tube". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "3: Case Studies". Making Transportation Tunnels Safe and Secure. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. 2006. pp. 42–44. ISBN 978-0-309-09871-7. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Chisholm, Daniel (1992). "5—The Fruits of Informal Coordination". Coordination Without Hierarchy: Informal Structures in Multiorganizational Systems. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520080379. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "BART train burns in tunnel; one killed". Eugene Register-Guard. AP. January 18, 1979. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "Fire shuts down BART 'tube'". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. January 19, 1979. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b "BART cancels request to reopen bay tube". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. February 12, 1979. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "BART resumes tube service for first time since fatal fire". Eugene Register-Guard. AP. April 5, 1979. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ "BART to participate in statewide earthquake drill Thursday" (Press release). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. October 14, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Jordan, Melissa (2014). "Behind the Scenes of BART's Role as Lifeline for the Bay Area". San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

Donna "Lulu" Wilkinson, an experienced train operator, was barreling through the Transbay Tube at 80 miles per hour in the cab of a 10-car train when the quake hit.

"I didn't even feel it," she recalled. She was about halfway through to San Francisco when she got the order to stop and hold her position.

It was routine procedure (and remains so) to do a short hold after any earthquake, even smaller ones, and passengers were familiar with that routine. "They didn't panic," she said. "I got on the intercom and told them we were holding for a quake and would be moving shortly."

The design and strength of the tube, an engineering marvel sunk into mud on the bottom of the bay, had insulated the train and its passengers from feeling the earth's movements. - ^ Annex to 2010 Association of Bay Area Governments Local Hazard Mitigation Plan "Taming Natural Disasters" (PDF) (Report). Association of Bay Area Governments. 2010. p. 8. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

BART's success in maintaining continuous service directly after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake reconfirmed the system's importance as a transportation "lifeline." While the earthquake caused transient movements in the Tube there was no significant permanent movement and BART service was uninterrupted except for a short inspection period immediately following the quake. With the closure of the Bay Bridge and the Cypress Street Viaduct along the Nimitz Freeway, BART became the primary passenger transportation link between San Francisco and East Bay communities. Its average daily transport of 218,000 passengers before the earthquake increased to an average of 308,000 passengers per day during the first full business week following the earthquake.

- ^ "Man Walking In Transbay Tube Prompts Temporary BART Shutdown". CBS SFBayArea. October 15, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Alund, Natalie Neysa (August 11, 2013). "BART trains back on track after man found walking in Transbay Tube". Oakland Tribune. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Bodley, Michael (December 30, 2016). "Man who sparked BART delays by running into Transbay Tube IDd". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael; Veklerov, Kimberly; Ravani, Sarah (January 6, 2017). "BART systemwide meltdown after train gets stuck in West Oakland". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Henry K. (March 17, 2010). "BART train splits in two in Transbay Tube". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Kane, Will; Huet, Ellen; Lee, Henry K. (September 3, 2014). "BART reopens Transbay Tube track". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Kale (January 7, 2015). "BART delays again after train gets stuck in Transbay Tube". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Veklerov, Kimberly (December 20, 2016). "Train stuck in Transbay Tube causes major BART delays". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Bodley, Michael (April 12, 2017). "BART back up after major service delays". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Cabanatuan, Michael (September 7, 2010). "Noise on BART: How bad is it and is it harmful?". SFGate. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ SFGATE, Katie Dowd (January 13, 2019). "'The worst sound in the history of man': How BART trains turned terror in 'Dead Space'". SFGATE. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Riders notice a quieter ride following first of two tube shutdowns". www.bart.gov. August 13, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Reisman, Will (May 12, 2013). "BART working to protect Transbay Tube from elements, ships". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Kale; Ho, Vivian (February 1, 2014). "BART tube reopened after anchor scare". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "Close eye being kept on sunken barge atop BART's Transbay Tube". San Francisco Examiner. Bay City News. April 11, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (June 22, 2007). "BART's New Vision: More, Bigger, Faster". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A1. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ Hernández, Lauren (November 14, 2018). "A second transbay tube for BART? It could happen". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "New Transbay Rail Crossing Program Overview + Project Contracting Plan" (PDF). BART. November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Dowd, Katie (March 10, 2016). "MTV show uses BART's Transbay Tube as the key to saving the world". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Veca, Don (audio director); Napolitano, Jayson (interviewer) (October 7, 2008). "Dead Space sound design: In space no one can hear interns scream. They are dead" (Interview). Original Sound Version. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Dead Space Dev Diary #3 -- YouTube의 오디오(4:30부터 시작)

외부 링크

| 위키미디어 커먼즈에는 트랜스베이 튜브와 관련된 미디어가 있다. |

- BART 히스토리

- Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel (1958). Trans-bay tube: supplemental report (Report). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- Feaver, Douglas B. (June 3, 1979). "Fire Preparedness for Subways". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- Gursoy, Ahmet (1996). "14: Immersed Tube Tunnels". In Bickel, John O.; Kuesel, Thomas R.; King, Elwyn H. (eds.). Tunnel Engineering Handbook (Second ed.). Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 268–297. ISBN 978-1-4613-8053-5. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- Hartlaub, Peter (May 19, 2011). "The birth of BART: Photos from the 1960s and 70s". SFGate. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- Lewis, Scott (October 23, 2013). "Longest Immersed-Tube Tunnels". Engineering News-Record. Retrieved August 20, 2016. (필요한 경우)

- Bragman, Bob (March 3, 2017). "Rare photos from the BART Transbay Tube construction project". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 5, 2017.