스페이스X 랩터

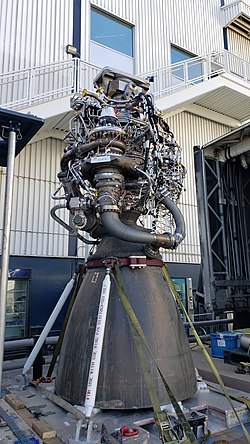

SpaceX Raptor 캘리포니아 호손에 있는 스페이스X의 공장 밖으로 운반할 준비가 된 랩터 1 로켓 엔진 | |

| 원산지 | 미국 |

|---|---|

| 제조사 | 스페이스X |

| 상황 | 현재사용중 |

| 액체연료 엔진 | |

| 추진제 | 록스 / CH4 |

| 혼합비율 | 3.6 (78% O2, 22% CH4)[1][2] |

| 주기 | 만류 단계 연소 |

| 펌프스 | 터보펌프 2개 |

| 배열 | |

| 체임버 | 1 |

| 노즐비 | |

| 성능 | |

| 스러스트 | 랩터 1: 185 tf (1.81 MN, 408,000 lbf)[5] 랩터 2: Raptor 3: 269 tf (2.64 MN; 593,000 lbf)[8] |

| 스로틀 범위 | 40–100%[11] |

| 추력대중량비 | 143.8, 해수면 |

| 체임버 압력 |

|

| 비임펄스, 진공 | 363 s (3.56 km/s)[10] |

| 비임펄스, 해수면 | 327 s (3.21 km/s)[9] |

| 질량 흐름 | |

| 연소시간 | 무차입증 |

| 치수 | |

| 길이 | 3.1 m (10 ft)[14] |

| 지름 | 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in)[15] |

| 건조중량 | 1,600kg (3,500lb)[6] |

| 사용처 | |

| 스페이스X 스타쉽 | |

랩터는 스페이스X가 개발하고 제조한 로켓 엔진 제품군입니다. 이 엔진은 극저온 액체 메탄 및 액체 산소("메탈록스")로 구동되는 FFSC(Full Flow Stage Combination Cycle) 엔진입니다.

SpaceX의 Starship 시스템은 초중량급 슈퍼헤비 부스터와 지구에서 발사될 때 두 번째 단계이자 우주에서 독립적인 우주선 역할을 하는 Starship 우주선에 랩터 엔진을 사용합니다.[16] 우주선 임무에는 탑재체를 지구 궤도로 들어올리는 것과 달과 화성으로의 임무가 포함되었습니다.[17] 엔진은 유지 보수가 거의 없이 재사용할 수 있도록 설계되었습니다.[18]

랩터는 역사상 세 번째 FFSC 엔진이며 비행 중인 차량에 동력을 공급하는 첫 번째 엔진입니다.[19]

설계.

만류 단계 연소

랩터는 완전 흐름 단계 연소 사이클에서 과냉각 액체 메탄 및 과냉각 액체 산소에 의해 구동됩니다.

FFSC는 Merlin이 사용하는 더 단순한 "오픈 사이클" 가스 발전기 시스템과 LOX/등유 추진제에서 벗어난 것입니다.[20] 우주왕복선에 처음 사용된 RS-25 엔진은 더 단순한 형태의 단계별 연소 사이클을 사용했습니다.[21] RD-180과[20] RD-191을 포함한 여러 러시아 로켓 엔진도 마찬가지였습니다.[22]

액체 메탄과 산소 추진제는 BE-4 엔진을 장착한 블루 오리진과 중국 스타트업 스페이스 에포크의 룽윈-70과 같은 많은 회사에서 채택되었습니다.[23] 2023년 7월에 궤도에 도달한 최초의 메탄 연료 발사체인 랜드스페이스의 주크-2 로켓.

산소가 풍부한 터빈은 산소 터보펌프에 동력을 공급하고 연료가 풍부한 터빈은 메탄 터보펌프에 동력을 공급합니다. 산화제와 연료 스트림은 모두 연소실로 들어가기 전에 가스상에서 완전히 혼합됩니다.[19] 랩터 2는 멀린의 점화 방식보다 덜 복잡하고, 더 가볍고, 더 저렴하며, 더 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 알려진 미공개 점화 방식을 사용합니다. 토치 점화기는 산소 및 전원 헤드에 사용됩니다. Raptor Vacuum의 엔진 점화는 이중 이중 스파크 플러그 점화 토치 점화기로 처리되므로 [24]멀린의 전용 소모성 점화기 유체가 필요하지 않습니다.[22] 랩터 2는 멀린의 핀틀 인젝터 대신 동축 스월 인젝터를 사용하여 연소실에 추진제를 허용합니다.[25][26]

2014년 이전에는 테스트 스탠드에 도달할 수 있을 정도로 충분히 진행된 FFSC 설계가 1960년대 소련의 RD-270 프로젝트와 2000년대 중반의 Aerojet Rocketdyne Integrated Powerhead Demonstrator 두 가지에 불과했습니다.[27][22][28]

랩터는 극도의 신뢰성을 위해 설계되었으며, 포인트 투 포인트 지구 운송 시장에서 요구하는 항공사 수준의 안전을 지원하는 것을 목표로 합니다.[29] 그윈 샷웰(Gwynne Shotwell)은 랩터가 "장수"를 전달할 수 있을 것이라고 주장했습니다. 그리고 더 양성적인 터빈 환경."[30][22]

추진제

랩터는 극저온 로켓 엔진에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 것처럼 비등점이 아닌 빙점 근처로 냉각된 유체인 깊은 극저온 추진체를 위해 설계되었습니다.[31] 과냉각 추진제는 공간을 적게 차지하여 탱크에 더 많은 추진제 질량을 허용합니다.[32] 과냉각 추진제는 또한 엔진 성능을 향상시킵니다. 비임펄스가 증가하고 발전된 동력 단위당 더 높은 추진제 연료 질량 유량으로 인해 터보펌프 입력 시 공동현상의 위험이 감소합니다.[22] 캐비테이션(거품)은 연료 흐름/압력을 감소시키고 엔진을 굶겨 터빈 블레이드를 부식시킬 수 있습니다.[33] 엔진의 연료 대비 산화제 비율은 약 3.8 대 1입니다.[34]

성능

랩터의 목표 성능은 진공 비임펄스 382초(3,750m/s)였으며, 추력은 3MN(67만 lbf), 챔버 압력은 300bar(30MPa; 4,400psi), 진공 최적화 변형의 경우 팽창 비율은 150이었습니다. 이것은 랩터 2로 이루어졌습니다.

제조 및 재료

초기 Rapter 프로토타입의 많은 구성 요소는 터보펌프 및 인젝터를 포함하여 3D 프린팅을 사용하여 제조되어 개발 및 테스트 속도를 높였습니다.[31][35] 2016년 서브스케일 개발 엔진은 부품의 40%(질량 기준)를 3D 프린팅으로 제조했습니다.[22] 2019년, 스페이스X의 자체 개발 SX300 인코넬 슈퍼 합금에서 엔진 매니폴드가 주조되었으며, 나중에 SX500으로 변경되었습니다.[36]

역사

구상

스페이스X의 멀린과 케스트렐 로켓 엔진은 RP-1과 액체 산소(케롤록스) 조합을 사용합니다. 랩터는 SpaceX의 Merlin 1D 엔진의 추력이 Falcon 9 및 Falcon Heavy 발사체에 동력을 공급합니다.

랩터는 2009년부터 수소와 산소 추진제를 태우는 것으로 구상되었습니다.[37] SpaceX는 2011년에 낮은 우선순위로 랩터 상위 단계 엔진에서 일하는 직원 몇 명을 두었습니다.[38][39]

2012년 10월, 스페이스X는 "멀린 1 시리즈의 엔진보다 몇 배 더 강력하고 멀린의 RP-1 연료를 사용하지 않는" 엔진에 대한 컨셉 작업을 발표했습니다.[40]

발전

2012년 11월, 머스크는 스페이스X가 메탄을 연료로 하는 로켓 엔진을 개발하고 있고, 랩터는 메탄을 기반으로 할 것이며,[41] 메탄은 화성 식민지화를 촉진할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[28] 화성 대기 중에 지하수와 이산화탄소가 존재하기 때문에 간단한 탄화수소인 메탄을 사바티에 반응을 이용해 화성에서 합성할 수 있었습니다.[42] NASA는 화성의 현장 자원 생산이 산소, 물, 메탄 생산에 사용 가능하다는 것을 발견했습니다.[43]

2014년 초 SpaceX는 랩터가 다음 로켓의 첫 번째 단계와 두 번째 단계에 모두 사용될 것이라고 확인했습니다. 이것은 디자인이 화성 식민지 수송기에서[28] 행성간 수송 시스템,[44] 빅 팰컨 로켓, 그리고 궁극적으로 스타쉽으로 발전하면서 유지되었습니다.[45]

이 개념은 랩터 지정 로켓 엔진 제품군(2012)[46]에서 풀 사이즈 랩터 엔진(2014)에 초점을 맞추기 위해 발전했습니다.[47]

2016년 1월, 미 공군은 SpaceX에 Falcon 9와 Falcon Heavy의 상부 단계에 사용할 시제품 Raptor를 개발하기 위해 미화 3,360만 달러의 개발 계약을 체결했습니다.[48][49]

첫 번째 버전은 250bar(25MPa, 3,600psi)의 챔버 압력에서 작동하도록 설계되었습니다.[50] 2024년 7월 현재 챔버 압력은 300bar에 달했습니다.[33]

각 엔진은 파이프와 배선을 엔진 열로부터 보호하기 위해 열 슈라우드가 필요합니다.[33]

테스트

랩터 부품의 초기 개발 테스트는[51] 2014년 4월에 [17][52]시작하여 NASA의 스테니스 우주 센터에서 수행되었습니다. 테스트는 시작 및 종료 절차, 하드웨어 특성화 및 검증에 중점을 두었습니다.[22]

SpaceX는 2014년부터 주입기 테스트를 시작하여 2015년에 산소 프리버너를 테스트했습니다. 4월부터 8월까지 총 400초 정도의 테스트 시간을 가진 프리버너의 76개의 핫파이어 테스트가 실행되었습니다.[51]

2016년 초, SpaceX는 랩터 테스트를 위해 텍사스 중심부에 있는 McGregor 테스트 사이트에 엔진 테스트 스탠드를 구축했습니다.[22][17] 최초의 랩터는 캘리포니아의 SpaceX Hawthorn 시설에서 제조되었습니다. 2016년 8월까지 개발 테스트를 위해 맥그리거로 배송되었습니다.[53] 엔진의 추력은 1 MN(220,000 lbf)이었습니다.[54] 테스트 스탠드에 도달한 최초의 FFSC 메탈록스 엔진이었습니다.[22]

설계 검증을 위해 서브스케일 개발 엔진을 사용했습니다. 그것은 비행 차량을 위해 구상된 엔진 디자인의 3분의 1 크기였습니다.[22] 200bar(20MPa, 2,900psi)의 챔버 압력과 1메가뉴턴(220,000lbf)의 추력을 특징으로 하며, SpaceX에서 설계한 SX500 합금을 사용하여 엔진에 최대 12,000파운드(830bar, 83MPa)의 고온 산소 가스를 포함하도록 만들어졌습니다.[55] 맥그리거에 있는 지상 시험대에서 짧게 발사하면서 시험을 했습니다.[22] 지구 대기에서 시험하면서 유동 분리 문제를 없애기 위해 시험 노즐 팽창 비율을 150으로 제한했습니다.[22]

2017년 9월까지 서브스케일 엔진은 42개의 테스트에 걸쳐 1200초의 발사를 완료했습니다.[56]

스페이스X는 2023년 2월 9일 31개의 엔진 테스트([57]33개로 예정)와 2023년 8월 25일 33개의 엔진 테스트를 포함하여 랩터 2를 사용하는 차량에 대한 많은 정적 화재 테스트를 완료했습니다.[58] 테스트 도중 50개 이상의 챔버가 녹았고, 20개 이상의 엔진이 폭발했습니다.[33]

SpaceX는 2023년 4월 20일 첫 통합 비행 테스트를 완료했습니다. 이 로켓은 33개의 랩터 2 엔진을 가지고 있었지만, 그 중 3개는 로켓이 움직이기 시작할 때쯤에 고장이 났습니다. 이 테스트는 멕시코 만 상공에서 ~39 km의 거리까지 올라간 후에 끝났습니다. 비행종결장치(FTS)가 부스터와 선박을 파괴하기 전에 여러 개의 엔진이 꺼졌습니다.[59]

두 번째 비행에서 33개의 부스터 엔진은 모두 부스트백 번 시동이 걸릴 때까지 불이 켜져 있었고, 6개의 스타쉽 엔진은 모두 FTS가 작동될 때까지 불이 켜져 있었습니다.[60][61]

스타쉽

원구성

2016년 11월, 랩터는 2020년대 초반에 제안된 행성 간 운송 시스템(ITS)에 전력을 공급할 것으로 예상되었습니다.[22] 머스크는 1단/부스터용으로 해수면에서 3,050kN(690,000lbf)의 추력을 가진 해수면 변형(팽창비 40:1)과 우주에서 3,285kN(73만8,000lbf)의 추력을 가진 진공 변형(팽창비 200:1)의 두 가지 엔진에 대해 논의했습니다. 1단의 고난이도 설계에서는 42개의 해수면 엔진이 구상되었습니다.[22]

두 번째 단계의 착륙에는 3개의 짐벌 해수면 랩터 엔진이 사용됩니다. 추가적인 6개의 비짐벌 진공 최적화 랩터(Raptor Vacuum)는 총 9개의 엔진에 대한 두 번째 단계의 주요 추진력을 제공합니다.[62][22] 랩터 진공은 훨씬 더 큰 노즐을 사용하여 382초(3,750m/s)의 특정 임펄스를 제공하도록 구상되었습니다.[63]

2017년 9월 머스크는 이전 디자인보다 약간 더 큰 추력을 가진 더 작은 랩터 엔진이 9m(30ft) 직경의 발사체인 BFR(Big Falcon Rocket)과 나중에 스타쉽(Starship)으로 이름을 바꾼 차세대 로켓에 사용될 것이라고 말했습니다.[64] 이 재설계는 지구 궤도 및 시스 달 탐사를 목표로 하여 새로운 시스템이 부분적으로 지구에 가까운 우주 공간에서 경제적인 우주 비행 활동을 통해 비용을 지불할 수 있도록 하였습니다.[65] 훨씬 더 작은 발사체를 사용하면 랩터 엔진이 더 적게 필요할 것입니다. 그 후 BFR은 첫 번째 스테이지에서 31대의 랩터를, 두 번째 스테이지에서 6대를 가질 예정이었습니다.[66][22]

스페이스X는 2018년 중반까지 해수면 랩터가 1,700kN(38,000lbf)의 추력을 가지고 330s(3,200m/s)의 특정 임펄스로 해수면에 도달할 것으로 예상되며, 노즐 출구 직경은 1.3m(4.3ft)라고 공개적으로 밝혔습니다. Raptor Vacuum은 진공에서[56] 356초(3,490m/s)의 비임펄스를 가지며, 노즐 출구 직경 2.4m(7.9ft)를 사용하여 375초(3,680m/s)의 비임펄스로 1,900kN(430,000lbf)의 힘을 발휘할 것으로 예상됩니다.[56]

2018년 9월에 제공된 BFR 업데이트에서 머스크는 랩터 엔진의 71초 화재 테스트 비디오를 보여주고 "이것은 배와 부스터 모두를 BFR에 동력을 공급할 랩터입니다. 그것은 동일한 엔진입니다. [...] 약 300bar 챔버 압력을 목표로 하는 약 200톤(미터)의 엔진입니다. [...] 높은 팽창 비율을 가지고 있다면 380의 특정 임펄스를 가질 가능성이 있습니다.[9] 스페이스X는 일생 동안 1000번의 비행을 목표로 했습니다.[67]

제안 Falcon 9 상부 스테이지

2016년 1월, 미국 공군(USAF)은 SpaceX에 Falcon 9 및 Falcon Heavy의 상부 단계에 사용할 랩터 시제품을 개발하기 위해 미화 3,360만 달러의 개발 계약을 체결했습니다. 이 계약에는 스페이스X가 최소 미화 6,730만 달러의 더블 매칭 자금을 지원해야 했습니다.[48][68] 엔진 테스트는 미국 공군의 감독하에 미시시피에 있는 나사의 스테니스 우주 센터에서 계획되었습니다.[48][49] USAF 계약은 단일 프로토타입 엔진 및 지상 테스트를 요구했습니다.[48]

2017년 10월, USAF는 진화된 소모성 발사체 프로그램을 위한 랩터 프로토타입에 대한 4,080만 달러의 수정 계약을 체결했습니다.[69] 그것은 액체 메탄과 액체 산소, 추진제, 완전 흐름 단계 연소 사이클을 사용하고 재사용할 수 있도록 하는 것이었습니다.[49]

생산.

2021년 7월, 스페이스X는 텍사스 남부에 기존 로켓 엔진 시험 시설 근처에 두 번째 랩터 생산 시설을 발표했습니다. 이 시설은 랩터 2의 연속 생산에 집중할 것이고, 캘리포니아 시설은 랩터 진공과 새로운/실험 랩터 디자인을 생산할 것입니다. 이 새로운 시설은 결국 매년 800개에서 1000개의 로켓 엔진을 생산할 것으로 예상됩니다.[70][71] 2019년 엔진의 (한계) 비용은 100만 달러에 육박하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 스페이스X는 연간 최대 500개의 랩터 엔진을 양산할 계획이었으며, 각각의 비용은 25만 달러 미만이었습니다.[72]

버전

랩터 진공

RVAC(Raptor Vacuum[73])는 공간에서 더 높은 비임펄스를 위해 재생 냉각 노즐이 확장된 Raptor의 변형입니다. 진공에 최적화된 랩터는 ~380s(3,700m/s)의 특정 임펄스를 목표로 했습니다.[74] 2020년 9월 맥그리거에서 랩터 진공 버전 1의 전체 기간 테스트가 완료되었습니다.[73] 랩터 진공의 첫 번째 기내 점화는 두 번째 통합 비행 테스트 중 S25에 있었습니다.[61]

랩터2

랩터 2는 랩터 1 엔진을 완전히 재설계한 것입니다.[75] 터보 기계, 챔버, 노즐 및 전자 제품은 모두 재설계되었습니다. 많은 플랜지가 용접부로 변환된 반면 다른 부품은 삭제되었습니다.[76] 생산이 시작된 후에도 간소화 작업이 이어졌습니다. 2022년 2월 10일, 머스크는 랩터 2의 기능과 디자인 개선을 보여주었습니다.[76][77]

2021년 12월 18일, 랩터 2는 제작을 시작했습니다.[78] 2022년 11월까지 SpaceX 생산량은 하루 이상이며 향후 발사를 위한 비축품을 만들었습니다.[79] 랩터 2는 스페이스X의 맥그리거 엔진 개발 시설에서 생산됩니다.

랩터 2는 2022년 2월까지 230tf(510,000lbf)의 추력을 지속적으로 달성하고 있었습니다. 머스크는 랩터 1의 약 절반에 달하는 제작비를 제시했습니다.[76]

랩터3

이 구간은 확장이 필요합니다. 추가해서 도와주시면 됩니다. (2023년 11월) |

2023년 5월, 머스크는 랩터 3~350bar(5,100psi)의 45초간 정적 발사에 성공하여 269톤의 추력을 생산했다고 보고했습니다.[80]

파생 엔진 설계

2021년 10월, 스페이스X는 새로운 로켓 엔진의 개념적 설계를 위한 노력을 시작했으며, 이는 추력 1톤당 미화 1,000달러 이하의 비용을 유지하는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다. 이 프로젝트는 1337 엔진이라고 불렸고, "LEET" (코딩 밈을 따서)라고 발음되었습니다.[79]

비록 이 노력은 2021년 말에 중단되었지만, 이 프로젝트는 이상적인 엔진을 정의하는 데 도움이 되었을 수 있으며 랩터 3에 통합된 아이디어를 생성했을 가능성이 있습니다. 머스크는 그 후 "랩터로 생명체를 다행성으로 만들 수는 없습니다. 너무 비싸기 때문입니다. 하지만 랩터는 1337년이 준비될 때까지 우리를 극복해야 합니다."라고 말했습니다.

다른 엔진과의 비교

| 엔진 | 로켓 | 스러스트 | 특정한 충동, 진공. | 스러스트-투- 중량비 | 추진제 | 주기 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 랩터 해면 | 스타쉽 | 2,400 kN (540,000 lbf)[54] | 350 s (3,400 m/s)[81] | 200(골) | LCH4/LOX | 만류 단계 연소 |

| 랩터 진공 | 380 s (3,700 m/s)[81] | 120 (최대) | ||||

| 멀린 1D 해수면 | 팔콘 부스터 스테이지 | 914 kN (205,000 lbf) | 311 s (3,050 m/s)[82] | 176[83] | RP-1 / LOX (과냉식) | 가스발생기 |

| 멀린 1D 진공 | 매상단 | 934 kN (210,000 lbf)[84] | 348 s (3,410 m/s)[84] | 180[83] | ||

| 블루 오리진 BE-4 | 뉴 글렌, 벌컨 | 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf)[85] | 339 s (3,320 m/s)[86] | LCH4/LOX | 산화제가 풍부한 단계 연소 | |

| 에네르고매쉬 RD-170/171M | 에네르기아, 제니트, 소유즈-5 | 7,904 kN (1,777,000 lbf)[87] | 337.2 s (3,307 m/s)[87] | 79.57[87] | RP-1 / LOX | |

| 에네르고매쉬 RD-180 | 아틀라스 3세, 아틀라스 5세 | 4,152 kN (933,000 lbf)[88] | 338 s (3,310 m/s)[88] | 78.44[88] | ||

| Energomash RD-191/181 | 앙가라 주, 안타레스 주 | 2,090 kN (470,000 lbf)[89] | 337.5 s (3,310 m/s)[89] | 89[89] | ||

| 쿠즈네초프 NK-33 | N1, Soyuz-2-1v | 1,638 kN (368,000 lbf)[90] | 331 s (3,250 m/s)[90] | 136.66[90] | ||

| 에네르고매쉬 RD-275M | 양성자-M | 1,832 kN (412,000 lbf) | 315.8 s (3,097 m/s) | 174.5 | 아니오24 / UDMH | |

| 로켓다인 RS-25 | 우주왕복선, SLS | 2,280 kN (510,000 lbf) | 453 s (4,440 m/s)[91] | 73[92] | LH2/LOX | 연료가 풍부한 단계 연소 |

| 에어로젯 로켓다인 RS-68A | 델타 IV | 3,560 kN (800,000 lbf) | 414 s (4,060 m/s) | 51[93] | LH2/LOX | 가스발생기 |

| 로켓다인 F-1 | 새턴 5세 | 7,740 kN (1,740,000 lbf) | 304 s (2,980 m/s)[94] | 83 | RP-1 / LOX | 가스발생기 |

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ Sierra Engineering & Software, Inc. (18 June 2019). "Exhaust Plume Calculations for SpaceX Raptor Booster Engine" (PDF). p. 1. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

The nominal operating condition for the Raptor engine is an injector face stagnation pressure (Pc) of 3669.5 psia and a somewhat fuel-rich engine O/F mixture ratio (MR) of 3.60. The current analysis was performed for the 100% nominal engine operating pressure (Pc=3669.5 psia) and an engine MR of 3.60.

- ^ Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (17 September 2021). "Draft Programmatic Environmental Assessment for the SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Launch Vehicle Program at the SpaceX Boca Chica Launch Site in Cameron County, Texas" (PDF). faa.gov. FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

Super Heavy is expected to be equipped with up to 37 Raptor engines, and Starship will employ up to six Raptor engines. The Raptor engine is powered by liquid oxygen (LOX) and liquid methane (LCH4) in a 3.6:1 mass ratio, respectively.

- ^ Sierra Engineering & Software, Inc. (18 June 2019). "Exhaust Plume Calculations for SpaceX Raptor Booster Engine" (PDF). p. 1. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

The subject engine uses a closed power cycle with a 34.34:1 regeneratively-cooled thrust chamber nozzle.

- ^ Dodd, Tim (7 August 2021). ""Starbase Tour with Elon Musk [PART 2]"". Everyday Astronaut. 4 minutes in. Youtube.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (23 January 2022). "Raptor 2 testing at full throttle on the SpaceX McGregor test stands". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ a b Dodd, Tim (14 July 2022). "Raptor 1 VS Raptor 2: What's New // What's Different". Everyday Astronaut. Youtube.

- ^ "Starship : Official SpaceX Starship Page". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "Raptor V3 just achieved 350 bar chamber pressure (269 tons of thrust). Congrats to @SpaceX propulsion team! Starship Super Heavy Booster has 33 Raptors, so total thrust of 8877 tons or 19.5 million pounds". 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Musk, Elon (17 September 2018). "First Lunar BFR Mission". YouTube. Event occurs at 45:30. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

And this is the Raptor engine that will power BFR both the ship and the booster, it's the same engine. And this is approximately a 200-ton thrust engine that's aiming for roughly a 300-bar or 300-atmosphere chamber pressure. And if you have it at a high expansion ratio it has the potential to have a specific impulse of 380.

- ^ Alejandro G. Belluscio (7 March 2014). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ @elonmusk (18 August 2020). "Max demonstrated Raptor thrust is ~225 tons & min is ~90 tons, so they're actually quite similar. Both Merlin & Raptor could throttle way lower with added design complexity" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ 2.23 MN 추력 및 350 s 특정 임펄스에서

- ^ a b 782% O, 22% CH4 혼합 비율

- ^ "Starship SpaceX". Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Musk, Elon (29 September 2017). "Making Life Multiplanetary". youtube.com. SpaceX. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ "Starship Users Guide, Revision 1.0, March 2020" (PDF). SpaceX/files. SpaceX. March 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

SpaceX's Starship system represents a fully reusable transportation system designed to service Earth orbit needs as well as missions to the Moon and Mars. This two-stage vehicle — composed of the Super Heavy rocket (booster) and Starship (spacecraft)

- ^ a b c Leone, Dan (25 October 2013). "SpaceX Could Begin Testing Methane-fueled Engine at Stennis Next Year". Space News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ "The rockets NASA and SpaceX plan to send to the moon".

- ^ a b Dodd, Tim (25 May 2019). "Is SpaceX's Raptor engine the king of rocket engines?". Everyday Astronaut. Youtube. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b Todd, David (22 November 2012). "SpaceX's Mars rocket to be methane-fuelled". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Musk said Lox and methane would be SpaceX's propellants of choice on a mission to Mars, which has long been his stated goal. SpaceX's initial work will be to build a Lox/methane rocket for a future upper stage, codenamed Raptor. The design of this engine would be a departure from the "open cycle" gas generator system that the current Merlin 1 engine series uses. Instead, the new rocket engine would use a much more efficient "staged combustion" cycle that many Russian rocket engines use.

- ^ "Space Shuttle Main Engines". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Belluscio, Alejandro G. (3 October 2016). "ITS Propulsion – The evolution of the SpaceX Raptor engine". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ Jones, Andrew. "Chinese startups conduct hot fire tests for mini version of SpaceX's Starship".

- ^ Ralph, Eric (27 August 2019). "SpaceX scrubs Starhopper's final Raptor-powered flight as Elon Musk talks 'finicky' igniters". Teslarati. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Raptor uses those spark plugs to ignite its ignition sources [forming] full-up blow torches ... —likely miniature rocket engines using the same methane and oxygen fuel as Raptor—then ignite the engine's methane and oxygen preburners before finally igniting those mixed, high-pressure gases in the combustion chamber.

- ^ Park, Gujeong; Oh, Sukil; Yoon, Youngbin; Choi, Jeong-Yeol (May 2019). "Characteristics of Gas-Centered Swirl-Coaxial Injector with Liquid Flow Excitation". Journal of Propulsion and Power. 35 (3): 624–631. doi:10.2514/1.B36647. ISSN 0748-4658.

- ^ Dodd, Tim (9 July 2022). "Elon Musk Explains SpaceX's Raptor Engine!". Everyday Astronaut. Youtube.

- ^ Nardi, Tom (13 February 2019). "The "impossible" tech behind SpaceX's new engine". Hackaday. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Belluscio, Alejandro G. (7 March 2014). "SpaceX advances drive for Mars rocket via Raptor power". NASAspaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (15 October 2017). "Musk offers more technical details on BFR system". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

[initial flight testing will be with] a full-scale ship doing short hops of a few hundred kilometers altitude and lateral distance ... fairly easy on the vehicle, as no heat shield is needed, we can have a large amount of reserve propellant and don't need the high area ratio, deep space Raptor engines. ... 'The engine thrust dropped roughly in proportion to the vehicle mass reduction from the first IAC talk,' Musk wrote when asked about that reduction in thrust. The reduction in thrust also allows for the use of multiple engines, giving the vehicle an engine-out capability for landings. ... Musk was optimistic about scaling up the Raptor engine from its current developmental model to the full-scale one. 'Thrust scaling is the easy part. Very simple to scale the dev Raptor to 170 tons,' he wrote. 'The flight engine design is much lighter and tighter, and is extremely focused on reliability.' He added the goal is to achieve 'passenger airline levels of safety' with the engine, required if the vehicle is to serve point-to-point transportation markets.

- ^ Shotwell, Gwynne (17 March 2015). "Statement of Gwynne Shotwell, President & Chief Operating Officer, Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX)" (PDF). Congressional testimony. US House of Representatives, Committee on Armed Service Subcommittee on Strategic Forces. pp. 14–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

SpaceX has already begun self-funded development and testing on our next-generation Raptor engine. ... Raptor development ... will not require external development funds related to this engine.

- ^ a b Elon Musk, Mike Suffradini (7 July 2015). Elon Musk comments on Falcon 9 explosion – Huge Blow for SpaceX (video). Event occurs at 39:25–40:45. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "The "super chill" reason SpaceX keeps aborting launches". Quartz. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dodd, Tim (9 July 2022). "Elon Musk Explains SpaceX's Raptor Engine!". Everyday Astronaut. Youtube. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Urban, Tim (16 August 2015). "How (and Why) SpaceX Will Colonize Mars — Page 4 of 5". Wait But Why. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

Musk: "The critical elements of the solution are rocket reusability and low cost propellant (CH4 and O2 at an O/F ratio of ~3.8). And, of course, making the return propellant on Mars, which has a handy CO2 atmosphere and lots of H2O frozen in the soil."

- ^ Zafar, Ramish (23 March 2021). "SpaceX's 3D Manufacturing Systems Supplier For Raptor Engine To Go Public Through SPAC Deal". Wccftech. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "SpaceX Casting Raptor Engine Parts from Supersteel Alloys Feb 2019". Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Long term SpaceX vehicle plans". HobbySpace.com. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "Notes: Space Access'11: Thurs. – Afternoon session – Part 2: SpaceX". RLV and Space Transport News. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "SpaceX Raptor LH2/LOX engine". RLV and Space Transport News. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, Zach (15 October 2012). "SpaceX aims big with massive new rocket". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ Todd, David (20 November 2012). "Musk goes for methane-burning reusable rockets as step to colonise Mars". FlightGlobal Hyperbola. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

"We are going to do methane." Musk announced as he described his future plans for reusable launch vehicles including those designed to take astronauts to Mars within 15 years, "The energy cost of methane is the lowest and it has a slight Isp (Specific Impulse) advantage over Kerosene," said Musk adding, "And it does not have the pain in the ass factor that hydrogen has".

- ^ GPUs to Mars: Full-Scale Simulation of SpaceX's Mars Rocket Engine. YouTube. 5 May 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ mmooney (8 November 2015). "In-Situ Resource Utilization – Mars Atmosphere/Gas Chemical Processing". NASA SBIR/STTR. NASA. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (27 September 2016). "SpaceX's Mars plans call for massive 42-engine reusable rocket". SpaceNews. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

Musk stated it's possible that the first spaceship would be ready for tests in four years... 'We're kind of being intentionally fuzzy about the timeline,' he said. 'We're going to try and make as much progress as we can with a very constrained budget.'

- ^ Foust, Jeff (15 October 2017). "Musk offers more technical details on BFR system". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Todd, David (20 November 2012). "Musk goes for methane-burning reusable rockets as step to colonise Mars". FlightGlobal Hyperbola. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

The new Raptor upper stage engine is likely to be only the first engine in a series of lox/methane engines.

- ^ Gwynne Shotwell (21 March 2014). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 21:25–22:10. 2212. Archived from the original (mp3) on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

our focus is the full Raptor size

- ^ a b c d "Contracts: Air Force". U.S. Department of Defense (Press release). 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Gruss, Mike (13 January 2016). "Orbital ATK, SpaceX Win Air Force Propulsion Contracts". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Elon Musk speech: Becoming a Multiplanet Species". 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. 제68회 호주 애들레이드 국제우주대회 연차총회

- ^ a b "NASA-SpaceX testing partnership going strong" (PDF). Lagniappe, John C. Stennis Space Center. NASA. September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

this project is strictly private industry development for commercial use

- ^ Messier, Doug (23 October 2013). "SpaceX to Conduct Raptor Engine Testing in Mississippi". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Berger, Eric (10 August 2016). "SpaceX has shipped its Mars engine to Texas for tests". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ a b 일론 머스크 트위터: SN40은 곧 테스트될 예정이며 330 바 엔진을 몇 가지 업그레이드했습니다. 참고로 랩터의 330bar는 225톤(50만 파운드)의 힘을 생산합니다.

- ^ "SpaceX Casting Raptor Engine Parts from Supersteel Alloys NextBigFuture.com". 18 February 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Gaynor, Phillip (9 August 2018). "The Evolution of the Big Falcon Rocket". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (9 February 2023). "SpaceX Test Fires 31 Engines on the Most Powerful Rocket Ever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1695158759717474379". Twitter. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Starship Flight Test". SpaceX. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Full Replay: SpaceX Launches Second Starship Flight Test, retrieved 30 November 2023

- ^ a b "- SpaceX - Launches". 21 November 2023. Archived from the original on 21 November 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Mike Wall (27 September 2016). "SpaceX's Elon Musk Unveils Interplanetary Spaceship to Colonize Mars". Space.com. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Musk, Elon (27 September 2016). "SpaceX IAC 2016 Announcement" (PDF). Mars Presentation. SpaceX. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ Mike Wall (29 September 2017). "Elon Musk Wants Giant SpaceX Spaceship to Fly People to Mars by 2024". Space.com. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Elon Musk (19 July 2017). Elon Musk, ISS R&D Conference (video). ISS R&D Conference, Washington DC, USA. Event occurs at 49:48–51:35. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

the updated version of the Mars architecture: Because it has evolved quite a bit since that last talk. ... The key thing that I figured out is how do you pay for it? If we downsize the Mars vehicle, make it capable of doing Earth-orbit activity as well as Mars activity, maybe we can pay for it by using it for Earth-orbit activity. That is one of the key elements in the new architecture. It is similar to what was shown at IAC, but a little bit smaller. Still big, but this one has a shot at being real on the economic front.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (29 September 2017). "Musk unveils revised version of giant interplanetary launch system". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ O'Callaghan, Jonathan (31 July 2019). "The wild physics of Elon Musk's methane-guzzling super-rocket". WIRED. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "SpaceX, Orbital ATK + Blue Origin Signed On By SMC For Propulsion Prototypes". Satnews Daily. 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Contracts: Air Force". U.S. Department of Defense Contracts press release. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

Space Exploration Technologies Corp., Hawthorne, California, has been awarded a $40,766,512 modification (P00007) for the development of the Raptor rocket propulsion system prototype for the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program. Work will be performed at NASA Stennis Space Center, Mississippi; Hawthorne, California; McGregor, Texas; and Los Angeles Air Force Base, California; and is expected to be complete by April 30, 2018. Fiscal 2017 research, development, test and evaluation funds in the amount of $40,766,512 are being obligated at the time of award. The Launch Systems Enterprise Directorate, Space and Missile Systems Center, Los Angeles AFB, California, is the contracting activity (FA8811-16-9-0001).

- ^ "Elon Musk says SpaceX's next Texas venture will be a rocket engine factory near Waco". Dallas Morning News. 10 July 2021. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Musk, Elon (10 July 2021). "We are breaking ground soon on a second Raptor factory at SpaceX Texas test site. This will focus on volume production of Raptor 2, while California factory will make Raptor Vacuum & new, experimental designs". Archived from the original on 10 July 2021.

- ^ "SpaceX – Starship". SpaceX. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

Starship is the fully reusable spacecraft and second stage of the Starship system.

- ^ a b "Completed a full duration test fire of the Raptor Vacuum engine at SpaceX's rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas". SpaceX. 24 September 2020. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Sea level Raptor's vacuum Isp is ~350 sec, but ~380 sec with larger vacuum-optimized nozzle". Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Ship 20 prepares for Static Fire - New Raptor 2 factory rises". NASASpaceFlight.com. 11 October 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Mooney, Justin; Bergin, Chris (11 February 2022). "Musk outlines Starship progress towards self-sustaining Mars city". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Starship Update, retrieved 12 February 2022

- ^ @elonmusk (18 December 2021). "Each Raptor 1 engine above produces 185 metric tons of force. Raptor 2 just started production & will do 230+ tons or over half a million pounds of force" (Tweet). Retrieved 20 November 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Isaacson, Walter. Elon Musk. Simon & Schuster. pp. 389–392. ISBN 978-1-9821-8128-4. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (13 May 2023). "Raptor V3 just achieved 350 bar chamber pressure (269 tons of thrust). Congrats to @SpaceX propulsion team! Starship Super Heavy Booster has 33 Raptors, so total thrust of 8877 tons or 19.5 million pounds" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Sea level Raptor's vacuum Isp is 350 sec, but 380 sec with larger vacuum-optimized nozzle". Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Merlin 1C". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b Mueller, Thomas (8 June 2015). "Is SpaceX's Merlin 1D's thrust-to-weight ratio of 150+ believable?". Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ a b "SpaceX Falcon 9 product page". Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Ferster, Warren (17 September 2014). "ULA To Invest in Blue Origin Engine as RD-180 Replacement". Space News. Archived from the original on 18 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "RD-171b". Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b c "RD-171M". NPO Energomash. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "RD-180". NPO Energomash. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "RD-191". NPO Energomash. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ a b c "NK-33". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2002. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "SSME". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Astronautica: SSME". Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Astronautica: RS-68". Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "F-1". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

외부 링크

- SpaceX Raptor Engine Test 2016년 9월 25일, SciNews, Video, 2016년 9월

- GPU to Mars: SpaceX의 Mars Rocket Engine, Adam Lichtl and Steven Jones의 본격 시뮬레이션, GPU 기술 컨퍼런스, 2015년 봄.

- 비공식 Raptor 엔진 로그 인포그래픽