안토시아닌

Anthocyanin

안토시아닌(Anthosianin)은 안토시아닌이라고도 불리며, pH에 따라 빨간색, 보라색, 파란색 또는 검은색으로 나타날 수 있는 수용성 진공 색소입니다.1835년, 독일의 약사인 루트비히 클라모르 마르콰르트는 그의 논문 "Die Farben der Blüthen"에서 처음으로 꽃에 파란 색을 주는 화합물에 안토키안이라는 이름을 붙였습니다.안토시아닌이 풍부한 식용 식물로는 블루베리, 라즈베리, 검은 쌀, 검은 콩 등이 있으며, 그 중에서도 빨강, 파랑, 보라, 검정 등이 있습니다.단풍의 몇몇 색깔은 안토시아닌에서 [1][2]유래된 것입니다.

안토시아닌은 페닐프로파노이드 경로를 통해 합성되는 플라보노이드(flavonoid)라고 불리는 모종의 분자에 속합니다.그들은 잎, 줄기, 뿌리, 꽃, 과일을 포함한 고등 식물의 모든 조직에서 발생할 수 있습니다.안토시아닌은 [3]당을 첨가함으로써 안토시아니딘으로부터 유도됩니다.그들은 냄새가 없고 적당히 떫습니다.

안토시아닌은 유럽연합(EU)에서 식음료 착색제로 승인됐지만 식품이나 보충 [4]성분으로 사용할 경우 안전성이 검증되지 않아 식품첨가제로 사용할 수 없습니다.안토시아닌이 인간의 생물학이나 [4][5][6]질병에 어떤 영향을 미친다는 결정적인 증거는 없습니다.

안토시아닌이 풍부한 식물

배색

꽃에서 안토시아닌 축적에 의해 제공되는 착색은 다양한 동물 꽃가루 매개자를 끌어들일 수 있는 반면, 과일에서 동일한 착색은 이러한 적색, 청색 또는 보라색을 포함하는 잠재적으로 먹을 수 있는 과일로 초식 동물을 유인함으로써 씨앗 분산을 도울 수 있습니다.

식물생리학

안토시아닌은 극한의 [7][8]온도로부터 식물을 보호하는 역할을 할 수 있습니다.토마토 식물은 활성 산소종에 대항하는 안토시아닌으로 차가운 스트레스로부터 보호하여 [7]잎의 세포사멸률을 낮춥니다.

광흡광도

안토시아닌의 붉은 색을 담당하는 흡광 패턴은 어린 케르쿠스 코시페라 잎과 같은 광합성 활성 조직에서 녹색 엽록소의 흡광 패턴과 상보적일 수 있습니다.그것은 녹색에 [9]이끌릴지도 모르는 초식동물의 공격으로부터 나뭇잎을 보호할 수도 있습니다.

발생

안토시아닌은 주로 꽃과 과일에서 발견되지만 잎과 줄기, 뿌리에서도 발견됩니다.이 부분들에서, 그들은 주로 표피와 주변 메조필 세포와 같은 외부 세포 층에서 발견됩니다.

자연에서 가장 자주 발생하는 것은 시아니딘, 델피니딘, 말비딘, 펠라고니딘, 페토니딘, 페투니딘의 글리코사이드입니다.광합성에 고정된 모든 탄화수소의 약 2%가 플라보노이드 및 그 유도체, 예를 들어 안토시아닌으로 변환됩니다.모든 육지 식물이 안토시아닌을 포함하는 것은 아닙니다; 선인장, 사탕무, 아마란스를 포함한 육질 식물에서, 그것들은 베타레인으로 대체됩니다.안토시아닌과 베타레인은 같은 [10][11]식물에서 발견된 적이 없습니다.

때때로 안토시아닌 함량이 높기 위해 일부러 사육되는 고추와 같은 관상용 식물은 특이한 요리적이고 미적인 매력을 가지고 있을 [12]수 있습니다.

꽃으로

안토시아닌은 일부 메코놉시스 종과 [13]재배종의 푸른 양귀비와 같은 많은 식물의 꽃에서 발생합니다.안토시아닌은 Tipala gesneriana, Tipala fosteriana,[14] Tipala eichleri와 같은 다양한 튤립 꽃에서도 발견되었습니다.

음식에서

| 식원 | 안토시아닌 함량 100g당 mg 단위로 |

|---|---|

| 악사이 | 410[15] |

| 블랙커런트 | 190–270 |

| 아로니아(초크베리) | 1,480[16] |

| 마리온블랙베리 | 317[17] |

| 블랙크로우베리 | 4,180[18] |

| 검은복분자 | 589[19] |

| 라즈베리 | 365 |

| 야생블루베리 | 558[20] |

| 체리 | 122[21] |

| 가넷여왕매실 | 277[22] |

| 레드커런트 | 80–420 |

| 흑미 | 60 [23] |

| 검은콩 | 213[24] |

| 블루콘(메이즈) | 71[25] |

| 자색옥수수 | 1,642 |

| 보라색 옥수수 껍질(건조) | 커널보다 10배 더 많은 수 |

| 보라색 토마토(신선) | 283 ± 46[26] |

| 콩코드포도 | 326[27] |

| 노튼포도 | 888[27] |

| 적양배추(신선) | c. 150[28] |

| 적양배추(건조) | c. 1442[28] |

안토시아닌이 풍부한 식물은 블루베리, 크랜베리, 빌베리와 같은 백시늄 종, 블랙 라즈베리, 레드 라즈베리, 블랙베리를 포함한 루부스 베리, 블랙커런트, 체리, 가지 (오렌지) 껍질, 블랙 라이스, 유베, 오키나와 고구마, 콩코드 포도, 무스카딘 포도, 레드 양배추, 바이올렛 꽃잎입니다.빨간 복숭아와 사과에는 안토시아닌이 [29][30][31][32]들어있습니다.안토시아닌은 바나나, 아스파라거스, 완두콩, 회향나무, 배, 그리고 감자에 덜 풍부하고, 특정한 그린구스베리 [16]품종에서는 전혀 없을 수 있습니다.

특히 흑콩(Glycine max L)의 종자 피막에서 가장 높은 기록량이 나타남.Merr.) 100g당 약 2g,[33] 보라색 옥수수 알맹이와 껍질, 블랙 초크베리(Aronia melanocarpa L.)의 껍질과 과육을 함유하고 있습니다(표 참조).안토시아닌 [34][35]함량을 결정하는 샘플 기원, 제조 및 추출 방법의 중대한 차이로 인해, 다음 표에 제시된 값은 직접적으로 비교할 수 없습니다.

자연, 전통적인 농업 방법, 그리고 식물 번식은 안토시아닌을 포함하는 다양한 희귀한 작물들을 생산해왔는데, 파란색 또는 빨간색의 살이 있는 감자들과 보라색 또는 빨간색의 브로콜리, 양배추, 콜리플라워, 당근, 그리고 옥수수를 포함했습니다.정원 토마토는 원래 칠레와 갈라파고스 제도에서 [36]온 야생 종의 보라색 착색의 유전적 기반을 정의하기 위해 유전자 변형 유기체의 (그러나 그것들을 최종 보라색 토마토에 포함시키지는 않음) 침투 라인을 사용하는 번식 프로그램의 대상이 되었습니다.인디고 로즈(Indigo Rose)로 알려진 품종은 2012년 [36]농업계와 가정용 정원사들이 상업적으로 이용할 수 있게 되었습니다.안토시아닌 함량이 높은 토마토를 투자하면 유통기한이 두 배로 늘어나고 수확 후 곰팡이 병원체인 보트리티스 시네레아의 [37]성장을 억제합니다.

어떤 토마토들은 또한 [38]과일에 많은 양의 안토시아닌을 생산하기 위해 금어초의 전사 인자로 유전적으로 변형되었습니다.안토시아닌은 또한 자연적으로 숙성된 [39][40]올리브에서 발견될 수 있으며, [39]일부 올리브의 빨간색과 보라색의 원인이 되기도 합니다.

식물성 식품의 잎에

보라색 옥수수, 블루베리, 또는 링곤베리와 같은 다채로운 식물 음식의 잎에 있는 안토시아닌의 함량은 먹을 수 있는 알맹이나 [41][42]과일보다 약 10배 높습니다.

안토시아닌의 양을 평가하기 위해 포도 열매 잎의 색 스펙트럼을 분석할 수 있습니다.스펙트럼 [43]분석에 기초하여 과일의 성숙도, 품질, 수확시간을 평가할 수 있습니다.

단풍색

가을 단풍을 담당하는 빨강, 보라, 그리고 그것들의 혼합된 조합은 안토시아닌에서 유래되었습니다.카로티노이드와 달리 안토시아닌은 성장기 내내 잎에 존재하지 않지만 [2]여름이 끝날 무렵에는 활발하게 생성됩니다.그들은 늦여름에 식물 안과 밖의 요인들의 복잡한 상호작용으로 인해 잎 세포의 수액에서 생깁니다.그들의 형성은 잎의 인산염의 수준이 [1]감소함에 따라 빛이 있을 때 당이 분해되는 것에 따라 달라집니다.가을의 주황색 잎들은 안토시아닌과 카로티노이드의 조합으로부터 생겨납니다.

안토시아닌은 온대 지역에서 약 10%의 나무 종에 존재하지만 뉴잉글랜드와 같은 특정 지역에서는 최대 70%의 나무 종에서 안토시아닌이 [2]생성될 수 있습니다.

착색제 안전성

안토시아닌은 착색제 코드가 [44][45]E163인 유럽 연합, 호주 및 뉴질랜드에서 식품 착색제로서 사용이 승인되었습니다.2013년 유럽 식품 안전청의 과학 전문가 패널은 다양한 과일과 채소의 안토시아닌이 식품 [4]첨가물로서 사용을 승인하기 위한 안전성과 독성 연구에 의해 불충분하게 특성화되었다고 결론 내렸습니다.위원회는 적포도 껍질 추출물과 블랙커런트 추출물을 사용한 안전한 역사에서 유럽에서 생산된 컬러 식품까지 확장하여 이 추출물 공급원들이 판결의 예외이며 충분히 [4]안전하다는 것을 보여주었다고 결론 내렸습니다.

안토시아닌 추출물은 미국에서 식품용으로 승인된 색소 첨가물 중에 특별히 열거되어 있지는 않지만, 색소로 사용하도록 승인된 포도 주스, 적포도 껍질 그리고 많은 과일과 채소 주스는 자연적으로 생성되는 안토시아닌이 [46]풍부합니다.의약품 또는 [47]화장품에 대한 승인된 착색제 중에 안토시아닌 공급원은 포함되지 않습니다.지방산으로 에스테르화하면 안토시아닌은 [48]식품의 친유성 착색제로 사용될 수 있습니다.

인휴먼

안토시아닌이 시험관 [49]내에서 항산화 작용을 하는 것으로 나타났지만,[5][50][51] 안토시아닌이 풍부한 음식을 섭취한 후 인간의 항산화 효과에 대한 증거는 없습니다.통제된 시험관 조건과 달리 생체 내 안토시아닌의 운명은 흡수된 물질의 대부분이 화학적으로 변형된 대사 물질로 존재하며([52]5% 미만) 잘 보존되지 않는다는 것을 보여줍니다.안토시아닌이 풍부한 음식을 섭취한 후에 보이는 혈액의 항산화 능력의 증가는 음식에 있는 안토시아닌에 의해 직접적으로 발생하는 것이 아니라,[52] 대신 음식에 있는 플라보노이드(안토시아닌 모체 화합물)의 대사로부터 유도된 요산 수치의 증가에 의해 발생할 수 있습니다.섭취된 안토시아닌의 대사산물이 위장관에서 재흡수되어 혈액에 들어가 전신적인 분포를 할 수 있고 더 작은 [52]분자로 효과를 가질 수 있습니다.

안토시아닌으로 인해 "항산화 작용"이 있다고 주장되는 음식을 먹는 것의 가능한 건강상 이점에 대한 2010년 과학적 증거 검토에서, 유럽 식품 안전청은 1) 사람의 식이 안토시아닌으로 인한 유익한 항산화 효과에 대한 근거가 없고, 2) 원인과 결과에 대한 증거가 없다는 결론을 내렸습니다.안토시아닌이 풍부한 식품의 소비와 DNA, 단백질, 지질의 산화적 손상으로부터의 보호 사이의 관계, 3) "항산화", "항암", "항노화" 또는 "건강한 노화" [5]효과를 가진 안토시아닌이 풍부한 식품의 소비에 대한 일반적인 증거는 없었습니다.

화학적 성질

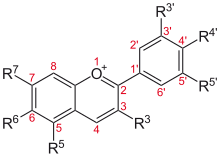

플라빌륨 양이온 유도체

| 기본구조 | 안토시아니딘 | R3' | R4' | R5' | R3 | R5 | R6 | R7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 아우란티니딘 | −H | −OH | −H | −OH | −OH | −OH | −OH |

| 시아니딘 | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | |

| 델피니딘 | −OH | −OH | −OH | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | |

| 유로피니딘 | −OCH 3 | −OH | −OH | −OH | −OCH 3 | −H | −OH | |

| 펠라고니딘 | −H | −OH | −H | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | |

| 말비딘 | −OCH 3 | −OH | −OCH 3 | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | |

| 페오니딘 | −OCH 3 | −OH | −H | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | |

| 페투니딘 | −OH | −OH | −OCH 3 | −OH | −OH | −H | −OH | |

| 로지니딘 | −OCH 3 | −OH | −H | −OH | −OH | −H | −OCH 3 |

안토시아니딘의 글리코사이드

안토시아닌, 안토시아니딘은 대부분 안토시아니딘의 3-글루코사이드입니다.안토시아닌은 무설탕 안토시아니딘 글리코사이드와 안토시아닌 [citation needed]글리코사이드로 세분됩니다.2003년 현재, 400개 이상의 안토시아닌이 [53]보고된 반면, 2006년 초의 후기 문헌에서는 550개 이상의 다른 안토시아닌이 보고되었습니다.안토시아닌이 pH의 변화에 반응하여 발생하는 화학구조의 차이는 할로크로미즘이라고 불리는 과정을 통해 산의 적색에서 염기의 청색으로 변화하기 때문에 pH 지표로 자주 사용되는 이유입니다.

안정성.

안토시아닌은 생체 내와 생체 내에서 물리화학적 분해가 일어날 수 있는 것으로 생각됩니다.구조, pH, 온도, 빛, 산소, 금속 이온, 분자 내 연관성 및 다른 화합물(코피그, 당, 단백질, 분해 생성물 등)과의 분자 간 연관성은 일반적으로 안토시아닌의 색상 [54]및 안정성에 영향을 미치는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.B-링 하이드록실화 상태와 pH는 안토시아닌의 페놀산 및 알데히드 [55]성분으로의 분해를 매개하는 것으로 나타났습니다.실제로 섭취된 안토시아닌의 상당 부분은 섭취 후에 생체 내에서 페놀산과 알데히드로 분해될 가능성이 있습니다.이러한 특성은 생체 내에서 특정 안토시아닌 메커니즘의 과학적 고립을 혼란스럽게 합니다.

pH를

안토시아닌은 일반적으로 높은 pH에서 분해됩니다.그러나, 페타닌(페투니딘 3-[6-O-(4-O-(E))-p-쿠마로일-O-α-와 같은 일부 안토시아닌l-람노피라노실)-β-d-글루코피라노사이드]-5-O-β-d-글루코피라노사이드)는 pH 8에서 분해에 강해 식품 [56]착색제로 효과적으로 사용될 수 있는 것.

환경 pH 지표로 사용

안토시아닌은 pH에 따라 색이 변하기 때문에 pH 지표로 사용될 수 있습니다; 그것들은 산성 용액에서 빨간색 또는 분홍색, 중성 용액에서 보라색(pH≥7), 알칼리 용액에서 녹색-황색(pH >7),[57] 그리고 색소가 완전히 감소된 매우 알칼리 용액에서 무색입니다.

생합성

- 안토시아닌 색소는 다른 모든 플라보노이드와 마찬가지로 세포 내 두 가지 화학 원료 흐름에서 조립됩니다.

- 이러한 스트림은 식물에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 폴리케티드 폴딩 메커니즘을 통해 중간 칼콘 유사 화합물을 형성하는 효소 칼콘 합성효소에 의해 만나 결합되고,

- 칼콘은 이후에 효소 칼콘 이성질화효소에 의해 전형적인 색소인 나링게닌으로 이성질화됩니다.

- 나링게닌은 플라바논 하이드록실라아제, 플라보노이드 3'-하이드록실라아제, 플라보노이드 3',5'-하이드록실라아제 등의 효소에 의해 산화되며,

- 이러한 산화 생성물은 다이하이드로플라보놀 4-환원효소에 의해 상응하는 무색의 [59]류코안토시아니딘으로 추가로 환원됩니다.

- 류코안토시아니딘은 한때 안토시아니딘 합성효소 또는 류코안토시아니딘 다이옥시제네이스라고 불리는 다이옥시제네이스의 직접적인 전구체로 여겨졌습니다.류코안토시아니딘 환원효소(LAR)의 생성물인 플라반-3-올(Flavan-3-ol)이 최근 그들의 진정한 기질인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.

- 불안정한 안토시아니딘은 UDP-3-O-글루코실트랜스퍼레이스와 [60]같은 효소에 의해 설탕 분자에 추가로 결합되어 최종적으로 비교적 안정한 안토시아닌을 생산합니다.

따라서 이 색소들을 합성하기 위해서는 5개 이상의 효소가 필요하며, 각각의 효소들은 함께 작용합니다.유전적인 요인이나 환경적인 요인에 의해 이러한 효소의 메커니즘 중 하나에 약간의 방해가 있어도 안토시아닌의 생성을 중단시킬 수 있습니다.안토시아닌을 생산하는 생물학적 부담이 비교적 높은 반면, 식물은 안토시아닌이 제공하는 환경 적응, 질병 내성 및 해충 내성으로부터 상당한 혜택을 받습니다.

안토시아닌 생합성 경로에서, L-페닐알라닌은 페닐알라닌 암모늄야아제(PAL), 시나메이트 4-하이드록실라아제(C4H), 4-쿠마레이트 CoA 리가아제(4CL), 칼콘 합성효소(CHS) 및 칼콘 이성질화효소(CHI)에 의해 나링게닌으로 전환됩니다.다음 경로를 촉매하여 플라바논 3-하이드록실레이스(F3H), 플라보노이드 3'-하이드록실레이스(F3H), 디하이드로플라보놀 4-환원효소(DFR), 안토시아니딘 합성효소(ANS), UDP-글루코사이드: 플라보노이드 글루코실트랜스퍼레이스(UFGT) 및 메틸트랜스퍼레이스(MT)에 의한 복합 아글리콘 및 안토시아닌의 형성을 유도하는 방법.UFGT는 UF3로 나뉩니다.안토시아닌의 글루코실화를 담당하는 GT와 UF5GT.[61]

아라비돕시스 탈리아나(Arabidopsis thaliana)에서, 안토시아닌 생합성 경로에 UGT79B1 및 UGT84A2의 두 글리코실트랜스퍼레이스가 관여합니다.UGT79B1 단백질은 시아니딘 3-O-글루코사이드를 시아니딘 3-O-자일로실(1→2)글루코사이드로 전환시킵니다.UGT84A2는 시나픽산(sinapic acid: UDP-glucosyl transferase)[62]을 암호화합니다.

유전자 분석

페놀성 대사 경로와 효소는 유전자의 형질전환을 통해 연구될 수 있습니다.안토시아닌 색소 1(AtPAP1)의 생산에서 아라비놉시스 조절 유전자는 다른 식물 종에서 [63]발현될 수 있습니다.

염료감응형 태양전지

안토시아닌은 빛 에너지를 전기 [64]에너지로 변환시키는 능력 때문에 유기 태양 전지에 사용되어 왔습니다.기존의 p-n 접합 실리콘 셀 대신 염료 감응형 태양 전지를 사용하면 순도가 낮고 부품 재료가 풍부할 뿐만 아니라 유연한 기판 위에서 생산할 수 있어 롤투롤 인쇄 [65]공정에 적용할 수 있다는 점이 많은 장점입니다.

비주얼 마커

안토시아닌 형광체, 식물 세포 연구를 위한 도구가 [66]다른 형광체를 필요로 하지 않고 살아있는 세포 이미징을 가능하게 합니다.안토시아닌 생산은 시각적으로 [67]식별이 가능하도록 유전자 조작된 물질로 조작될 수 있습니다.

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b Davies, Kevin M. (2004). Plant pigments and their manipulation. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4051-1737-1.

- ^ a b c Archetti, Marco; Döring, Thomas F.; Hagen, Snorre B.; et al. (2011). "Unravelling the evolution of autumn colours: an interdisciplinary approach". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (3): 166–73. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.006. PMID 19178979.

- ^ Andersen, Øyvind M (17 October 2001). "Anthocyanins". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001909. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ a b c d "Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of anthocyanins (E 163) as a food additive". EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority. 11 (4): 3145. April 2013. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2013.3145.

- ^ a b c EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2010). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061". EFSA Journal. 8 (2): 1489. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1752.

- ^ "Flavonoids". Micronutrient Information Center. Corvallis, Oregon: Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ a b Qiu, Zhengkun; Wang, Xiaoxuan; Gao, Jianchang; Guo, Yanmei; Huang, Zejun; Du, Yongchen (4 March 2016). "The Tomato Hoffman's Anthocyaninless Gene Encodes a bHLH Transcription Factor Involved in Anthocyanin Biosynthesis That Is Developmentally Regulated and Induced by Low Temperatures". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0151067. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1151067Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151067. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4778906. PMID 26943362.

- ^ Breusegem, Frank Van; Dat, James F. (1 June 2006). "Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Cell Death". Plant Physiology. 141 (2): 384–390. doi:10.1104/pp.106.078295. ISSN 1532-2548. PMC 1475453. PMID 16760492.

- ^ Karageorgou P; Manetas Y (2006). "The importance of being red when young: anthocyanins and the protection of young leaves of Quercus coccifera from insect herbivory and excess light". Tree Physiol. 26 (5): 613–621. doi:10.1093/treephys/26.5.613. PMID 16452075.

- ^ Francis, F.J. (1999). Colorants. Egan Press. ISBN 978-1-891127-00-7.

- ^ Stafford, Helen A. (1994). "Anthocyanins and betalains: evolution of the mutually exclusive pathways". Plant Science. 101 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1016/0168-9452(94)90244-5.

- ^ Stommel J, Griesbach RJ (September 2006). "Twice as Nice Breeding Versatile Vegetables". Agricultural Research Magazine, US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Colour range within genus". Meconopsis Group. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ N. Marissen, W. G. van Doorn, U. van Meeteren, 국제 원예학회, 제8회 관상 식물의 수확 후 생리학 국제 심포지엄, 2005, p. 248, Google Books

- ^ Moura, Amália Soares dos Reis Cristiane de; Silva, Vanderlei Aparecido da; Oldoni, Tatiane Luiza Cadorin; et al. (March 2018). "Optimization of phenolic compounds extraction with antioxidant activity from açaí, blueberry and goji berry using response surface methodology". Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture. 30 (3): 180–189. doi:10.9755/ejfa.2018.v30.i3.1639.

- ^ a b Wu X; Gu L; Prior RL; et al. (December 2004). "Characterization of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in some cultivars of Ribes, Aronia, and Sambucus and their antioxidant capacity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (26): 7846–56. doi:10.1021/jf0486850. PMID 15612766.

- ^ Siriwoharn T; Wrolstad RE; Finn CE; et al. (December 2004). "Influence of cultivar, maturity, and sampling on blackberry (Rubus L. Hybrids) anthocyanins, polyphenolics, and antioxidant properties". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (26): 8021–30. doi:10.1021/jf048619y. PMID 15612791.

- ^ Ogawa K; Sakakibara H; Iwata R; et al. (June 2008). "Anthocyanin Composition and Antioxidant Activity of the Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) and Other Berries". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (12): 4457–62. doi:10.1021/jf800406v. PMID 18522397.

- ^ Wada L; Ou B (June 2002). "Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of Oregon caneberries". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 50 (12): 3495–500. doi:10.1021/jf011405l. PMID 12033817.

- ^ Hosseinian FS; Beta T (December 2007). "Saskatoon and wild blueberries have higher anthocyanin contents than other Manitoba berries". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (26): 10832–8. doi:10.1021/jf072529m. PMID 18052240.

- ^ Wu X; Beecher GR; Holden JM; et al. (November 2006). "Concentrations of anthocyanins in common foods in the United States and estimation of normal consumption". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (11): 4069–75. doi:10.1021/jf060300l. PMID 16719536.

- ^ Fanning K; Edwards D; Netzel M; et al. (November 2013). "Increasing anthocyanin content in Queen Garnet plum and correlations with in-field measures". Acta Horticulturae. 985 (985): 97–104. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.985.12.

- ^ Hiemori M; Koh E; Mitchell A (April 2009). "Influence of Cooking on Anthocyanins in Black Rice (Oryza sativa L. japonica var. SBR)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (5): 1908–14. doi:10.1021/jf803153z. PMID 19256557.

- ^ Takeoka G; Dao L; Full G; et al. (September 1997). "Characterization of Black Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Anthocyanins". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 45 (9): 3395–3400. doi:10.1021/jf970264d.

- ^ Herrera-Sotero M; Cruz-Hernández C; Trujillo-Carretero C; Rodríguez-Dorantes M; García-Galindo H; Chávez-Servia J; Oliart-Ros R; Guzmán-Gerónimo R (2017). "Antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of blue corn and tortilla from native maize". Chemistry Central Journal. 11 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/s13065-017-0341-x. PMC 5662526. PMID 29086902.

- ^ Butelli E, Titta L, Giorgio M, et al. (2008). "Enrichment of tomato fruit with health-promoting anthocyanins by expression of select transcription factors". Nat Biotechnol. 26 (11): 1301–1308. doi:10.1038/nbt.1506. PMID 18953354. S2CID 14895646.

- ^ a b Muñoz-Espada, A. C.; Wood, K. V.; Bordelon, B.; et al. (2004). "Anthocyanin Quantification and Radical Scavenging Capacity of Concord, Norton, and Marechal Foch Grapes and Wines". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (22): 6779–86. doi:10.1021/jf040087y. PMID 15506816.

- ^ a b Ahmadiani, Neda; Robbins, Rebecca J.; Collins, Thomas M.; Giusti, M. Monica (2014). "Anthocyanins Contents, Profiles, and Color Characteristics of Red Cabbage Extracts from Different Cultivars and Maturity Stages". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (30): 7524–31. doi:10.1021/jf501991q. PMID 24991694.

- ^ Cevallos-Casals, BA; Byrne, D; Okie, WR; et al. (2006). "Selecting new peach and plum genotypes rich in phenolic compounds and enhanced functional properties". Food Chemistry. 96 (2): 273–328. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.032.

- ^ Sekido, Keiko; et al. (2010). "Efficient breeding system for red-fleshed apple based on linkage with S3-RNase allele in 'Pink Pearl'". HortScience. 45 (4): 534–537. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.45.4.534.

- ^ Oki, Tomoyuki; Kano, Mitsuyoshi; Watanabe, Osamu; Goto, Kazuhisa; Boelsma, Esther; Ishikawa, Fumiyasu; Suda, Ikuo (2016). "Effect of consuming a purple-fleshed sweet potato beverage on health-related biomarkers and safety parameters in Caucasian subjects with elevated levels of blood pressure and liver function biomarkers: a 4-week, open-label, non-comparative trial". Bioscience of Microbiota, Food and Health. 35 (3): 129–136. doi:10.12938/bmfh.2015-026. PMC 4965517. PMID 27508114.

- ^ Moriya, Chiemi; Hosoya, Takahiro; Agawa, Sayuri; Sugiyama, Yasumasa; Kozone, Ikuko; Shin-ya, Kazuo; Terahara, Norihiko; Kumazawa, Shigenori (7 April 2015). "New acylated anthocyanins from purple yam and their antioxidant activity". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 79 (9): 1484–1492. doi:10.1080/09168451.2015.1027652. PMID 25848974. S2CID 11221328.

- ^ Choung, Myoung-Gun; Baek, In-Youl; Kang, Sung-Taeg; et al. (December 2001). "Isolation and determination of anthocyanins in seed coats of black soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.)". J. Agric. Food Chem. 49 (12): 5848–51. doi:10.1021/jf010550w. PMID 11743773.

- ^ Krenn, L; Steitz, M; Schlicht, C; et al. (November 2007). "Anthocyanin- and proanthocyanidin-rich extracts of berries in food supplements—analysis with problems". Pharmazie. 62 (11): 803–12. PMID 18065095.

- ^ Siriwoharn, T; Wrolstad, RE; Finn, CE; et al. (December 2004). "Influence of cultivar, maturity, and sampling on blackberry (Rubus L. Hybrids) anthocyanins, polyphenolics, and antioxidant properties". J Agric Food Chem. 52 (26): 8021–30. doi:10.1021/jf048619y. PMID 15612791.

- ^ a b Scott J (27 January 2012). "Purple tomato debuts as 'Indigo Rose'". Oregon State University Extension Service, Corvallis. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Zhang, Y.; Butelli, E.; De Stefano, R.; et al. (2013). "Anthocyanins Double the Shelf Life of Tomatoes by Delaying Overripening and Reducing Susceptibility to Gray Mold". Current Biology. 23 (12): 1094–100. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.072. PMC 3688073. PMID 23707429.

- ^ Butelli, Eugenio; Titta, Lucilla; Giorgio, Marco; et al. (November 2008). "Enrichment of tomato fruit with health-promoting anthocyanins by expression of select transcription factors". Nature Biotechnology. 26 (11): 1301–8. doi:10.1038/nbt.1506. PMID 18953354. S2CID 14895646.

- ^ a b Agati, Giovanni; Pinelli, Patrizia; Cortés Ebner, Solange; et al. (March 2005). "Nondestructive evaluation of anthocyanins in olive (Olea europaea) fruits by in situ chlorophyll fluorescence spectroscopy". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (5): 1354–63. doi:10.1021/jf048381d. PMID 15740006.

- ^ Stan Kailis & David Harris (28 February 2007). "The olive tree Olea europaea". Producing Table Olives. Landlinks Press. pp. 17–66. ISBN 978-0-643-09203-7.

- ^ Li, C. Y.; Kim, H. W.; Won, S. R.; et al. (2008). "Corn husk as a potential source of anthocyanins". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (23): 11413–6. doi:10.1021/jf802201c. PMID 19007127.

- ^ Vyas, P; Kalidindi, S; Chibrikova, L; et al. (2013). "Chemical analysis and effect of blueberry and lingonberry fruits and leaves against glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (32): 7769–76. doi:10.1021/jf401158a. PMID 23875756.

- ^ Bramley, R.G.V.; Le Moigne, M.; Evain, S.; et al. (February 2011). "On-the-go sensing of grape berry anthocyanins during commercial harvest: development and prospects" (PDF). Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 17 (3): 316–326. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2011.00158.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". United Kingdom: Food Standards Agency. 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ 오스트레일리아 뉴질랜드 식품 표준"Standard 1.2.4 – Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 27 October 2011. 코드

- ^ "Summary of Color Additives for Use in the United States in Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics, and Medical Devices". US Food and Drug Administration. May 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ "Summary of Color Additives for Use in the United States in Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics, and Medical Devices". US Food and Drug Administration. May 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Marathe, Sandesh J.; Shah, Nirali N.; Bajaj, Seema R.; Singhal, Rekha S. (1 April 2021). "Esterification of anthocyanins isolated from floral waste: Characterization of the esters and their application in various food systems". Food Bioscience. 40: 100852. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100852. ISSN 2212-4292. S2CID 233070680.

- ^ De Rosso, VV; Morán Vieyra, FE; Mercadante, AZ; et al. (October 2008). "Singlet oxygen quenching by anthocyanin's flavylium cations". Free Radical Research. 42 (10): 885–91. doi:10.1080/10715760802506349. PMID 18985487. S2CID 21174667.

- ^ Lotito SB; Frei B (2006). "Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon?". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41 (12): 1727–46. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033. PMID 17157175.

- ^ Williams RJ; Spencer JP; Rice-Evans C (April 2004). "Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules?". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 36 (7): 838–49. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. PMID 15019969.

- ^ a b c "연구들은 플라보노이드의 생물학에 대한 새로운 관점을 강요합니다." 데이비드 스타우트, 유렉 경고!오리건 주립대학교에서 발행한 뉴스 보도자료를 각색함.

- ^ Kong, JM; Chia, LS; Goh, NK; et al. (November 2003). "Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins". Phytochemistry. 64 (5): 923–33. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00438-2. PMID 14561507.

- ^ Andersen, Øyvind M.; Jordheim, Monica (2008). "Anthocyanins- food applications". 5th Pigments in Food congress- for quality and health. University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-10-4846-3.

- ^ Woodward, G; Kroon, P; Cassidy, A; et al. (June 2009). "Anthocyanin stability and recovery: implications for the analysis of clinical and experimental samples". J. Agric. Food Chem. 57 (12): 5271–8. doi:10.1021/jf900602b. PMID 19435353.

- ^ Fossen T; Cabrita L; Andersen OM (December 1998). "Colour and stability of pure anthocyanins influenced by pH including the alkaline region". Food Chemistry. 63 (4): 435–440. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00065-X. hdl:10198/3206.

- ^ Michaelis, Leonor; Schubert, M.P.; Smythe, C.V. (1 December 1936). "Potentiometric Study of the Flavins". J. Biol. Chem. 116 (2): 587–607. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)74634-6.

- ^ Jack Sullivan (1998). "Anthocyanin". Carnivorous Plant Newsletter. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ Nakajima, J; Tanaka, Y; Yamazaki, M; et al. (July 2001). "Reaction mechanism from leucoanthocyanidin to anthocyanidin 3-glucoside, a key reaction for coloring in anthocyanin biosynthesis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (28): 25797–803. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100744200. PMID 11316805.

- ^ Kovinich, N; Saleem, A; Arnason, JT; et al. (August 2010). "Functional characterization of a UDP-glucose:flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase from the seed coat of black soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.)". Phytochemistry. 71 (11–12): 1253–63. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.009. PMID 20621794.

- ^ Da Qiu Zhao; Chen Xia Han; Jin Tao Ge; et al. (15 November 2012). "Isolation of a UDP-glucose: Flavonoid 5-O-glucosyltransferase gene and expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.)". Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 15 (6). doi:10.2225/vol15-issue6-fulltext-7.

- ^ Yonekura-Sakakibara K; Fukushima A; Nakabayashi R; et al. (January 2012). "Two glycosyltransferases involved in anthocyanin modification delineated by transcriptome independent component analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana". Plant J. 69 (1): 154–67. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04779.x. PMC 3507004. PMID 21899608.

- ^ Li, Xiang; Gao, Ming-Jun; Pan, Hong-Yu; et al. (2010). "Purple canola: Arabidopsis PAP1 increases antioxidants and phenolics in Brassica napus leaves". J. Agric. Food Chem. 58 (3): 1639–1645. doi:10.1021/jf903527y. PMID 20073469.

- ^ Cherepy, Nerine J.; Smestad, Greg P.; Grätzel, Michael; Zhang, Jin Z. (1997). "Ultrafast Electron Injection: Implications for a Photoelectrochemical Cell Utilizing an Anthocyanin Dye-Sensitized TiO

2 Nanocrystalline Electrode" (PDF). The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 101 (45): 9342–51. doi:10.1021/jp972197w. - ^ Grätzel, Michael (October 2003). "Dye-sensitized solar cells". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. 4 (2): 145–53. doi:10.1016/S1389-5567(03)00026-1.

- ^ Wiltshire EJ; Collings DA (October 2009). "New dynamics in an old friend: dynamic tubular vacuoles radiate through the cortical cytoplasm of red onion epidermal cells". Plant & Cell Physiology. 50 (10): 1826–39. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcp124. PMID 19762337.

- ^ Kovinich, N; Saleem, A; Rintoul, TL; et al. (August 2012). "Coloring genetically modified soybean grains with anthocyanins by suppression of the proanthocyanidin genes ANR1 and ANR2". Transgenic Res. 21 (4): 757–71. doi:10.1007/s11248-011-9566-y. PMID 22083247. S2CID 15957685.

추가열람

- Andersen, O.M. (2006). Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-2021-7.

- Gould, K.; Davies, K.; Winefield, C., eds. (2008). Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-77334-6.