루바익스

Roubaix루바익스 로바이스 | |

|---|---|

시청 | |

| 모토: 프로비타스 엣 인더스트리아 | |

| |

| 좌표:50°41′24″N 3°10′54″e/50.6901°N 3.18167°E좌표: 50°41′24″N 3°10′54″E / 50.6901°N 3.18167°E/ ° | |

| 나라 | 프랑스. |

| 지역 | 오트드프랑스 |

| 부서 | 노르 |

| 아르론디스먼트 | 릴 |

| 광동 | 루바익스-1과 루바익스-2 |

| 인터커뮤니티티 | 메트로폴 에우로페네 데 릴 |

| 정부 | |

| • 시장(2020–2026) | 기욤 델바[1] |

| 면적 1 | 13.23km2(5.11제곱 mi) |

| 인구 (1919년 1월)[2] | 98,828 |

| • 밀도 | 7,500/km2(19,000/sq mi) |

| 데모닉 | 루바이어스어(en) 루바이엔(ne) (fr) |

| 시간대 | UTC+01:00(CET) |

| • 여름(DST) | UTC+02:00(CEST) |

| INSEE/우편 번호 | 59512 /59100 |

| 표고 | 17–52m(56–520ft) (평균 35m 또는 115ft) |

| 웹사이트 | www.ville-roubaix.fr (프랑스어로) |

| 1 1km2(0.386평방미터 또는 247에이커) 이하의 호수, 연못, 빙하 및 하천 유역을 제외한 프랑스 토지 등록부 자료. | |

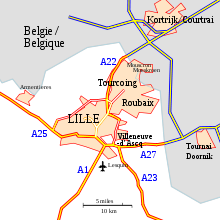

루바익스(프랑스어: [ʁubɛ] 또는 [ʁube];네덜란드어: 로바이스;웨스트 플랑드르: 로보아이스)는 벨기에 국경의 릴 메트로폴리탄 지역에 위치한 프랑스 북부의 도시다.19세기 들어 섬유산업에서 급성장한 노르드부의 역사적으로 단산업 공동체로[3], 영미 붐 타운과 거의 같은 특징을 가지고 있다.[4][5]이 이전의 신도시는 1970년대 중반에 주요 산업이 쇠퇴했기 때문에 도시 붕괴와 같은 탈산업화와 관련된 많은 어려움에 직면해 왔다.[6]투르코잉과 인접한 릴의 북동쪽에 위치한 루바익스는 두 칸톤의 셰프 리우로 프랑스 오트 드 프랑스 지역에서 3번째로 큰 도시로서 9만9천명에 가까운 주민이 거주하고 있다.[7]

루바익스는 인근 도시인 릴, 투르코잉, 빌레뉴브다스크, 86개의 다른 공동체와 함께 110만명 이상이 거주하는 4중심의 대도시 지역인 릴의 유럽 메트로폴리스에 구조물을 제공하고 있다.[8][9][10][11]루바익스는 벨기에의 무스크론, 코르트리히크, 투르나이 도시와 함께 형성된 광대한 교란 중심에 있으며, 이 도시는 2008년 1월 제1차 유럽 지역협력그룹인 릴레-코트리히크–을 탄생시켰다.총 인구 2백만 명 이상의 투르나이.[12]

지리

위치

루바익스는 벨기에 국경에서 가까운 릴의 동쪽과 투르코잉의 남쪽에 위치한 메트로폴 유로페엔 드 릴의 북동쪽 경사면의 중심 위치를 차지하고 있다.마을의 경계와 관련하여, 루바익스는 바로 인접한 환경을 구성하는 7개 도시가 포괄한다.이러한 자치단체는 다음과 같다.북쪽과 북서쪽으로 관광하고, 북동쪽으로 와트렐로스, 동쪽으로는 리스, 남동쪽으로 리스-레즈-란노이, 남쪽으로는 헴, 남서쪽과 서쪽으로는 크로익스를 관광한다.루바익스는 이들 자치구와 21개의 다른 공동체와 함께 리스와 셸트 강 사이의 옛 카스텔라니의 작은 지역인 페레인 땅에 속해 있다.[13]

까마귀가 날면 루바익스(Rubaix)와 다음 도시 사이의 거리는 약간 이상하다: 16km에서 투르나이(Tournai), 18km에서 코르트리히크(Kortrijk)까지, 84km에서 브뤼셀(Brussell)까지, 213km(132mi)[14]에서 파리(Paris)까지.

지질학

루바익스가 누워 있는 평원은 멜란투아-투르나이스 산맥의 고생대석까지[15] 남동쪽으로 향하는 동서향의 얕은 싱클린 축 위에 펼쳐져 있다.[16]이 지역은 주로 홀로세안 충적분비증으로 이루어져 있다.그것은 평탄하고 낮으며, 13.23 평방 킬로미터(5.11 평방 미터)에 걸쳐 35m(114피트 10인치)의 높이 강하밖에 되지 않는다.이 지역의 최저 고도는 다음과 같다.17m(55ft 9+1⁄2 in), 반면 최고 고도는 해발 52m(170ft 7 in)이다.[17]

수문학

에스피에르 하천 물이 공급한 트리콘 하천은 19세기 중반 산업화 과정이 이 지역을 변화시키기 시작하기 전에 루바익스의 농촌 풍경을 통해 흐르곤 했다.[18]그 세기부터, 뒤이은 산업은 믿을 만한 물자 공급에 대한 욕구가 증가하면서, 드들 강 상류와 하류에서 마르케와 에스피에르를 셸트 강 쪽으로 연결하는 내륙의 수로 건설로 이어져 루바와 릴을 직접 연결하게 되었다.[19][20]

1877년에 문을 연 [21]운하 드 루바익스는 북쪽 이웃에서 동쪽 이웃까지 도시를 가로지르며 도시의 경계를 따라 흐른다.Canal de Rubaix는 1세기가 넘는 사용 끝에 1985년에 폐쇄되었다.[22]유럽의 자금 지원 프로젝트인 블루 링크스 덕분에, 이 수로는 2011년부터 항행으로 다시 개통되었다.[23]

기후

19세기 동안 루바익스의 기상 상태가 좋지 않았다는 일부 미국인들의 진술에도 불구하고,[24][25] 이 도시의 지역은 특이한 기상 사건을 겪고 있는 것으로 알려져 있지 않다.이 마을의 지리적 위치와[26] 메테오-프랑스의 릴레스킨 기상 관측소의 결과에 비추어 볼 때,[27][28] 루빅스는 온화한 해양성 기후로, 여름은 온화한 기온을 경험하지만 겨울의 기온은 영하로 떨어질 수 있다.강수량은 드물게 강렬하다.

토포니미

현재 도시의 이름은 프랭크 라우사 "자유"와 바키 "브룩"[29][30][31]에서 유래했을 가능성이 크다.따라서 루바익스의 의미는 십중팔구 그 세 개의 역사적 중심지, 즉 에스피에르, 트리콘, 파브레우일의 둑에서 그 기원을 찾을 수 있다.[32]그 장소는 9세기 라틴어 형태로 처음으로 언급되었다: 빌라 러스바시.[30][31][33]그 후 1047년과 1106 루바이스, 1122 로스베이, 1166 러스바이스, 1156년, 1202 로바이스, 1223 루바이스 등의 이름이 사용됐다.[30][34]수세기 동안, 그 이름은 1540년 르우벤에서 출판된 메르카토르의 플란더스 지도에서 보여지듯이 루바익스로 발전했다.[35]

공식적이고 통상적인 이름인 루바익스와 유사하게, 일부 번역은 언급할 가치가 있다.첫째로, 이 도시는 플랑드르어를 사용하는 지역에 속해본 적은 없지만,[36] 거의 들어본 적이 없는 렌더링 로베케와[37][38] 로데비케는[39] 루바이에 대해 기록되어 있다.[40]게다가, 네덜란드 언어 연합은 이 도시의 적절한 네덜란드어 이름으로 로바이스(Robais)를 설립했다.[41]마지막으로, 1840년에 세워진 시청과 1842년에 세워진 노트르담 교회의 첫 번째 돌에 봉인된 헌신의 진술에 따르면, 로스바쿰을 19세기 이후 사용되어 온 루바익스의 확실한 라틴어 필사본으로 인용할 수 있다.[42]

역사

헤럴드리

| 루바익스의 팔은 불타올랐다. 엷은 색으로 된 당은 우두머리 노새 한 마리를 침식하고, 거기서 두 개의 보빈 사이에 5점짜리 별이나 수석, 그 중심에 양털 카드 한 장과 베이스에 있는 왕복선 한 장, 또는 모두 같은 것에 움푹 들어간 보두르 안쪽에 있다.

|

사람

Inhabitants of Roubaix are known in English as "Roubaisians" and in French as Roubaisiens (pronounced [ʁu.bɛ.zjɛ̃ ]) or in the feminine form Roubaisiennes (pronounced [ʁu.bɛ.zjɛn]), also natively called Roubaignos (pronounced [ʁu.bɛ.njo]) or in the feminine form Roubaignoses (pronounced [ʁu.bɛ.njoz]).[43][44][45]

인구통계학

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1962년부터 1999년까지: 이중 계수가 없는 인구 출처: L.E. Marissal (1716, 1789, 1801, 1805, 1817, 1830, 1842년),[46] Comte du Muy (1764년),[47] Ldh/EHESS/Cassini (2006년까지[17]), INSEEE (2007년부터[48]) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

주민 수의 진화는 1793년 이후 마을에서 실시된 인구 검열과 1844년 발간된 도시 평화 사무국 루이스 에드먼드 마리살 연구 연구를 통해 알려져 있다.[46]루바익스는 1716년 인구조사 인구가 4,715명으로 근대 초기 말까지 지방 시장 도시로 진화했다.[46]18세기 후반에 이르러 이 도시는 지역 섬유 제조 중심지로 부상하기 시작했고 인구가 증가하여 1800년에는 8,091명에 이르렀다.19세기 산업화 과정의 결과, 노동자의 필요성은 이민뿐 아니라 농촌 비행으로 공급되었다.벨기에의 정착은 당시 루바이의 삶의 특징이었다.[49][50]

루바익스는 19세기 전반기에 인구증가율 5배로 프랑스 최초로 인구증가율을 기록했지만,[51] 이번 세기의 남은 기간에는 인구가 두 배로 늘었다.이 마지막 틀 안에서 벨기에 이민은 1866년 30,465명, 1872년 42,103명의 벨기에 주민을 헤아릴 정도로 상당히 높은 인구 증가를 설명하는 주요 요인 중 하나로 보였다.[52]그럼에도 불구하고, 자연증가율은 그 시기 인구증가의 더 중요한 요소가 되었다.[53]

20세기 문턱에서 루바이족 인구는 12만4661명으로 최고조에 달했고, 그 이후 수십 년간 지속적으로 감소하였다.1914년 10월부터 1918년 10월까지 독일군이 점령한 루바익스는 제1차 세계대전 당시 서부전선의 전투구역에 속했다.[54]이 점령기에 걸쳐 루바이족들은 1911년과 1921년 검열 사이에 12만2723명에서 11만3265명으로 다소 인구가 감소하면서 강제 노동과 특이한[55] 인명 피해로 인한 빈곤과 추방을 겪었다.[56]

이 도시의 인구는 2019년 1월 기준으로 98,828명이다.[7]이로써 루빅스는 이 지역에서 릴과 아미엔스에 이어 세 번째로 큰 자치구로 남을 수 있게 됐다.

언어들

루바익스 지역은 역사 내내 플란더스 통치자의 지배하에 여러 번 시달렸음에도 불구하고 루바이어스 사람들은 수세기 동안 지역 피카르 변종을 일상 생활의 언어로 사용해 왔다.이 토속어는 현지에서 루브이노트로 알려져 있다.[57][58]20세기 초까지만 해도 이 패투아이는 우세했다.[59]따라서 지역문화에 대한 프랑스어 점진적 침투는 그 지역의 산업화와 도시화의 결과로 분석되어야 할 뿐만 아니라 공교육 정책 측면에서도 고려되어야 한다.[44][60]

종교

기독교

루바익스 시는 6개의 가톨릭 교구로 나뉘어져 있으며 릴 대교구의 동명 학장에 속한다.

유대교

프랑코-프러시아 전쟁과 독일 알자스-로레인의 합병의 여파로 많은 유대인들이 집을 떠나 이민을 떠났다.[61][62]유대인의 루바익스 도착은 그 쓰라린 역사의 시대에서 비롯되었다.[63][64]당시 새 이민자 공동체는 규모는 작지만 유대교 신앙과 소송 관행에 건물을 바쳤다.[64][65][66]새로 문을 연 회당은 좁은 뤼 데 샹젤(Changz)의 51번지 주택에 위치해 [64][66]60년 이상 운영됐다가 1939년 당시 나치 정권이 유럽을 점령하면서 현지 사정으로 폐쇄됐다.[66][67]유대교의 지역실습은 유대교 회당의 폐쇄, 점령, 경찰의 습격에도 불구하고 1990년대 초까지 지속된 전쟁 이후 겸손한 부활을 보였는데, 당시 유대교의 겸손한 유대인이 세페르 토라를 릴 유대 공동체의 보살핌에 넘겨주었다.[note 1][69][67]루바익스는 그 사건 이후 더 이상 유대인 예배당의 본거지였던 적이 없다.[70]123년 전 처음 지어진 이 주택은 2000년 도시재생사업이 발생한 이후 철거됐다.[64]2015년 9월 10일, 시장은 이 이전 건물의 종교적 목적을 기념하기 위해 루바이스 유대인들에 대한 헌화로, 샹젤 기념 현판을 공개했다.[67]

이슬람교

2013년 8월 현재 이 마을에는 건설 중인 이슬람 사원을 포함해 6개의 사원이 있다.시장실 추산에 따르면 인구의 약 20%에 해당하는 2만여 명이 무슬림이었다.[71]묘지의 네 지역은 이슬람교도들을 위해 지정되었다.[72]

불교

이 도시는 20세기 후반에 캄보디아, 라오스, 태국, 베트남 등 동남아시아 반도의 불교 국가들로부터 불교 공동체를 흡수했다.[73]이러한 배경 속에서 루바익스는 그 영토에 두 가지 불교 전통을 결합시켰고, 따라서 지역 사회 전반에 걸친 문화적 변화를 가져왔다.마하야나와 테라바다는 각각 1곳과 4곳의 예배 장소를 가지고 있다.[74]

도시주의

도시지리학

중세에는 성 마틴 교회와 옛 요새화된 성 사이에 펼쳐진 지역을 넘어 원시 중심부를 중심으로 북향 반원형으로 도시가 성장했다.이 남쪽 경계선의 존재는 18세기까지 남아 주로 도시의 서부와 북쪽에서 일어난 도시 확장을 의미했다.[75]산업화 증가, 육상 교통 개선, 지속적인 인구 증가, 그리고 결과적으로 주택과 제조 공장에 적합한 저비용 토지의 필요성, 그리고 이 모든 것들이 마침내 19세기에 도시를 중심에서 남쪽으로 확장하는 결과를 가져왔다.[76]

행정 및 정무

선거구 및 선거구

루바익스는 1988년부터 2012년까지 4개의 캔톤을 묶었다.이후 이 숫자는 루바익스 1, 루바익스 2와 함께 둘로 떨어졌다.2010년 프랑스 입법부의 마지막 선거구 조정 이후, 시는 현재 두 개의 선거구로 나뉘어져 있다.노드의 7번째 선거구는 루바익스-오우에스트의 옛 광장과 다음의 옛 캔톤에 의해 형성된 노드의 8번째 선거구다.루바ix-Centre, 루바ix-Nord 및 루바ix-Est.

관리 구역제

동부 지역 이웃들

- 브라유니테

- 쌓다

- 사인엘리자베스

- 사텔카리헴

- 트로이스 폰츠

서부 지역 이웃들

- 에펄레

- 프레즈노이마켈러리

- 트리콘

중앙 지구 인접 지역

- 안젤메 모테보수트

- 바비룩스

- 중앙빌

- 크루이

- 에스페랑스

- 네이션스 유니즈

- 바우반

북부 지역 주민들

- 알마게레

- 아르멘티에르

- 컬 드 포

- 엔트레폰트

- 포세스 아우슈 체네스

- 옴므레

- 후틴오란카르티니

남부 지역 주민들

- 체민 뉴프

- 에두아르 바얀트

- 오츠샹

- 정의

- 린네불레바르드

- 물랭

- 누보 루바익스

- 쁘띠-헤이스

- 포텐네리

시장님들

| 시장 | 임기시작 | 기간종료 | 파티[note 2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 앙리 카르타트 | 1892년 5월 | 1901년 12월 | POF |

| 에두아르 루셀 | 1901년 12월 | 1902년 1월 | UDR |

| 외젠 모테 | 1902년 1월 | 1912년 5월 | FR |

| 장바티스트 레바스[note 3] | 1912년 5월 | 1915년 3월 | SFIO |

| 앙리 테린[note 4] | 1915년 3월 | 1918년 10월 | SFIO |

| 장바티스트 레바스 | 1918년 10월 | 1940년 6월 | SFIO |

| 플뢰리스 반헤르페[note 5] | 1940년 6월 | 1941년 8월 | |

| 마르셀 기슬랭 | 1941년 8월 | 1941년 12월 | |

| 알퐁스 베르베르크트 | 1942년 1월 | 1942년 5월 | |

| 샤를 보두인 | 1942년 5월 | 1942년 7월 | |

| 빅토르 프로보[note 6] | 1942년 7월 | 1977년 3월 | SFIO, PS |

| 피에르 프루보스트 | 1977년 3월 | 1983년 3월 | PS |

| 안드레 부지런함 | 1983년 3월 | 1994년 5월 | UDF-CDS |

| 르네 반디렌던크 | 1994년 5월 | 2012년 3월 | UDF-CDS 이후 DVG 및 최종 PS |

| 피에르 두부아 | 2012년 3월 | 2014년 3월 | PS |

| 기욤 델바 | 2014년 4월 | – | UMP 이후 LR 및 DVD |

국제 관계

1969년부터[83][84] 영국 브래드포드

1969년부터[83][84] 영국 브래드포드 1969년부터[85][86] 독일 뮌청라드바흐

1969년부터[85][86] 독일 뮌청라드바흐 1969년부터[85][86] 벨기에의 베르비에르

1969년부터[85][86] 벨기에의 베르비에르 1973년부터[87] 북마케도니아 스코프제

1973년부터[87] 북마케도니아 스코프제 1981년부터[88] 이탈리아의 프라토

1981년부터[88] 이탈리아의 프라토 1993년부터[89] 폴란드 소노이에크

1993년부터[89] 폴란드 소노이에크 2000년[90] 이후 포르투갈 코빌량

2000년[90] 이후 포르투갈 코빌량 2003년부터[83] 알제리 부하라

2003년부터[83] 알제리 부하라

랜드마크

20세기 초에 세계적인 섬유 수도로 여겨졌던 이 유명한 도시에는 주목할 만한 건물, 오래된 벽돌 공장, 창고들이 많이 있다.[91]그리하여 이 도시는 19세기 산업혁명의 프랑스 역사와 문화에서 가장 많은 건축 작품 중 하나를 물려받았고 2000년 12월 13일 예술과 역사의 마을로 지정되었다.[92]문화부가 루바익스에게 이 꼬리표를 부여한 이후, 이 도시는 산업 및 사회 역사의 계승으로서 문화적 지위를 홍보함으로써 21세기에 접어들었다.[93]

루바익스의 여러 불경건물이 역사적 기념물로 등록되어 있다.

세속 건물

천골 건물

- 기념비적 역사 등록 천골 건축물

조각과 기념물

이 도시는 19세기 말부터 20세기 중반까지 프랑스 조각가들의 저명한 이름들이 기념비를 만들기 위해 그들의 기술을 쏟아부은 곳이다.긴 침체기였던 2010년 이후, 빔 델보예의 디스코볼로스가 공개되면서 장르의 변화를 도입했는데, 현대 미술의 조각상은 도시의 이웃을 환영하는 표시로 여겨졌다.[94]루바익스의 역사적 또는 예술적 관심으로 주목받을 만한 조각과 기념비가 아래에 언급되어 있다.

- 디스코볼로스:빔 델보예(스컬프토르), 브루노 뒤퐁(중재자), 폰딩 드 프랑스 및 루바익스(서포터즈) 시(서포터즈)로, 인근 주민들이 호므레트 인근 위원회[note 7] 위원들과 함께 명령하고 2010년[95] 6월 5일 취임했다.

- 잔 다르크 동상: 막심 레알 델 사르트 (sculptor, 1952년[96] 5월 27일 취임)

- 장바티스트 레바스 기념관:앨버트 드 재거(스컬프터)는 공모를 통해 자금을 지원받아 1949년[96][97] 10월 23일 취임했다.

- 루바익스 저항 순교자 기념비: 알버트 드 재거(스컬프터)는 1948년[98] 11월 11일 시의회가 지시하고 취임하는 '루바ix a ses resistance de la resistance'와 'Ils ontent brisé les chaînes de l'ression'[note 8]을 새겼다.

- 외젠 모테 기념관: 라울 베나드(스컬프터), 구스타브 푸벨(건축가), 공모를 통해 자금을 지원받아 1935년[96] 9월 22일 취임했다.

- 장 요제프 웨르츠 기념관:알렉상드르 데카토르(Sculptor)는 시의회의 명령으로 1931년[99] 10월 29일 취임했다.

- 루이보스투트 기념관: 맥심 레알 델 사르트(스컬프터) 시 의회의 명령으로 1925년[96][100] 10월 4일 취임

- 기념물 보조 모르츠 또는 제1차 세계 대전 루바ix 기념관: 알렉산드르 데카토르(스컬프토르), 장-프레데릭 비엘호르스키(건축가)가 1925년[101] 10월 18일 시의회가 명령하고 취임했다.[note 9]

- 메모리얼 투 쥘 게스트드:조지테 아구테 셈바트(Sculptor), 앨버트 뷔르(Albert Bührer)는 공모를 통해 자금을 조달하고 1925년[102][103] 4월 12일 취임했다.

- 아메데 프루보스트 기념관:히폴리테 르페브르(스컬프토르)는 시의회가 명령하고 1922년[96] 10월 29일 취임했다.

- 피에르 데스톰즈 기념관:코르네유 테우니센(sculptor)은 시 의회가[96][104] 명령하고 1922년 10월 29일에 취임하여 "호토룸, 음악애, 천칭, 스튜디오"를 새겼다.[note 10]

- 구스타브 나다우드 기념관:1896년[96][105] 10월 11일 취임한 알퐁세 아메데 코르도니에(스컬프토르), 구스타브 르블랑 바르베디엔(미술 설립자)

문화

박물관

루바익스는 21세기 초부터 프랑스의 두 주요 박물관인 라 피신(La Piscine[note 11])과 라 제조(La Manufacturing)의 본거지였으며,[note 12] 두 지역의 사회경제 역사를 모두 계승하고 있다.'뮤제 다르트 앤드리 앤드리 부지런'으로도 알려진 라 피신(La Piscine)은 프랑스 북부에서 가장 찬사를 받는 문화 명소 중 하나이다.[note 13]이 박물관은 2000년 19, 20세기 도시의 소장품을 수용하여 전시하기 위해 리모델링한 건물인 아트 데코 스타일의 옛 루바익스 수영장에 소장되어 있다.[note 14]2년간 보수공사와 증축공사를 거쳐 2018년 10월 일반에 다시 공개되면서 그 어느 때보다 큰 성공을 거두었다.[106]La Manufacturing은 프랑스 북부에 있는 기준 섬유 박물관이다.그것은 오래된 직조 공장에서 주최된다.

페인팅

19세기 중반부터 20세기 초까지 루바익스에서 명성을 떨친 화가들의 가장 권위 있는 이름은 장조셉 웨르츠와[99] 레미 코게다.[107]

제2차 세계대전 말기부터 1970년대 초까지 루바익스와 주변 지역의 젊은 예술가들의 캐주얼한 그룹이 결성되어 그루프 드 루바익스라는 이름을 갖게 되었다.[108][109][110]이 그룹과 공통적으로 연관된 두 명의 화가로는 아서 반 헤케와 외젠 르로이가 있다.[111][112][113]

패션

프랑스 북부 섬유산업의 위신을 회복하고 메아송 드 모드라는 꼬리표 아래 운영되고 있는 릴과 루바익스 도시들은 2007년부터 새로운 패션 디자이너들이 번창할 수 있는 공간을 만들어냈다.라 피신 박물관 옆에 있는 루바이스의 위치는 르 베스티아이어로 알려져 있다.[note 15]오래된 산업용 건물에 15개의 부티크와 패션 스튜디오가 있다.[114]

연극 및 공연 예술 센터

- 중앙 초레그래피크 국립 루바익스 - 오트 드 프랑스[note 16]

- 콜리제

- 조건 publique

- 테레 드 로이소 무슈 "레 차고"

- 테레 루이 리처드

- 테레 피에르 드 루바익스

시네마

루바익스 시는 다음 영화의 촬영지(대부분 또는 부분)였다.

- 2015년[115] Laurent Larivier가 감독한 I Am a Suntat(프랑스어: Je suis un sandat)

- 나의 골든 데이즈(프랑스어:2015년[116][117] 아르노 데스플친 감독이 연출한 트로이스 기념품 드 마 주네스(De ma jeunese)

- 2014년[118] 루이 줄리앙 쁘띠 감독 할인

- 2013년[119][120] 장마르크 루드니키 감독이 연출한 퀸즈 오브 더 링(프랑스어: 레스 라이네스 듀 링)

- 2013년[121][122] 압델라티프 케치체 감독이 연출한 블루 아이즈 더 웜 컬러(프랑스어: La Vie d'Adéle – Chapitres 1&2)

- 2008년[123] 아르노 데스플친 감독이 연출한 크리스마스 이야기(프랑스어: Un conté de Noel)

- The Banishment (Russian: Изгнание, Izgnanie), directed by Andrey Zvyagintsev in 2007[124][125]

- 2005년[123] 안네 폰테인이 감독한 In His Hands(프랑스어: Entre ses main)

- 2005년[126][127] 코스타가브라스 감독이 연출한 액스(프랑스어: 르 쿠페레트)

- 2000년[128] 크리스티안 빈센트 감독 세이브 미(프랑스어: Sauve-Moi)

- 플랫[129][130] 랜드 시티(프랑스어: Les Cités de la Plaine), 1999년 로버트 크레이머 감독

- 1998년[131][132] 에릭 존카 감독이 연출한 천사의 드림라이프(프랑스어: La Vie révée des Anges)

- 에니그마, 1982년[117] 장노트 슈워크 감독

- 1988년[117][123] 에티엔 차틸리에즈 감독이 연출한 Life Is a Long Quiet River(프랑스어: La vie est un long fleuve talkille)

- 허리케인 로지(이탈리아어:1979년[133] 마리오 모니첼리 감독이 연출한 프랑스어: 로제 라 부르라스케(Todale Rosy, Rosy: Rosy la Bourrasque)

- 1979년[134] 장루이 트린트하이트가 연출한 수영 강사(프랑스어: Le Maître-nageur)

- 1976년[117][123] 앙리 베르누일 감독이 연출한 '내 적의 몸'(프랑스어: Le Corp de mon ennemi)

- A Sunday in Hell(다니쉬: En For forrsdag i Helvede), 1976년 요르겐 레스 감독 덴마크 다큐멘터리

- 1970년[117][123] 코스타 가브라스 감독이 연출한 고백(프랑스어: 라베우)

- 이탈리아에서의 투쟁(이탈리아어:1970년[135] 지그아 베르토프 그룹 감독(Dziga Vertov Group)

고등교육

- EDHEC 경영대학원은 파리 메트로폴리탄 지역 밖에 위치한 몇 안 되는 그랑제콜 중 하나이다.그것은 유럽에서 가장 빠르게 성장하는 경영 대학 중 하나이다.

- ENSAIT는 섬유와 관련된 모든 학문을 모으는 고등 교육 및 연구 기관이다.

- ESATH는 디자인 교육 기관이다.

- 릴 2세·릴 3세[136] 대학 분산화

도서관

- 메디아테크 "라 그랑플라주"

- 일 세계 국가기록원

스포츠

루바익스는 오래된 스포츠 유산을[137] 가지고 있으며, 벨로드롬에서 세계 최고령 프로 도로 사이클 경주 중 하나인 파리-루바익스의 종주국이다.루바익스는 벨로드롬으로 유명하지만, 이 도시에는 사이클링 스포츠 시설보다 더 많은 것이 있다.

도심에 실내외 스포츠 편의시설을 건립하는 것은 지역 스포츠 클럽과 협회 발전 외에도 산업혁명 시대 경제 성장 시대와 연계해야 한다.[138]

2021년 10월 루바익스는 2021년 UCI 트랙 사이클 세계선수권대회를 개최했다.

이코노미

19세기 동안 루바익스는 섬유 산업과 양모 생산으로 국제적인 명성을 얻었다.1970년대와 1980년대에 국제 경쟁과 자동화는 산업 쇠퇴를 야기했고 많은 공장들이 문을 닫았다.그 순간부터 1980년대 초 프랑스의 도시 정책이 시행된 이후부터 이 도시 지역의 약 3/4에 대해 보건 및 복지 계획뿐만 아니라 특정 구역 지정이 정기적으로 배정되었다.[139]

루바익스의 높은 실업률은 탈산업화의 결과물이다.그 도시는 프랑스의 가장 가난한 도시들 중 하나이다.[93][140]연이은 지방 정부들은 신산업을 유치하여 탈산업화와 관련된 어려움을 해결하고, 마을의 문화적 자격증을[93] 최대한 활용하고, 다양한 캠퍼스에서 학생 입지를 강화하려고 노력해왔다.시는 전환 노력을 거치면서 온라인 유통과 정보기술(IT) 등 성공적인 경제 스토리를 활용할 수 있는 새로운 모델을 실험하고 있으며 수십 년의 쇠퇴를 반전시킬 수 있는 길을 걷고 있는 것으로 보인다.[141]

섬유공업

요즘 국내 섬유업체들은 첨단 섬유 제품 개발에 주력하고 있다.

상업 및 서비스

La Redoute, Damart[143][144], [142]3 Suisses와 같은 국제적인 명성의 우편 주문 회사들은 루바익스에 설립된 섬유 산업에서 비롯되었다.[145][146]아마존닷컴은 2016년부터 온라인 플래시 판매를 전문으로 하는 전자상거래 기업으로 현지에서 설립됐다.

정보 기술 및 e-비즈니스

- OVH는 1999년 루바익스에서 탄생해 글로벌 IT 인프라 기업이 되면서 도시와 주변 지역에 천여 개의 일자리를 창출했다.본사는 아직 루바익스에 있다.[147]

- 안카마게임즈는 2007년부터 루바익스에 본사를 설립했다.[148]

- 인큐베이터 유라테크놀로지의 도움을 받는 전자상거래 클러스터 블랑쉬마일은 2014년부터 루바익스의 옛 라 레두테 빌딩에 설립됐다.

사회 기반 시설

교통

부르고뉴에서 앤트워프까지 이어지는 유럽 노선 E17의 프랑스어 부분인 A22 오토아웃은 루빅스를 지나는 파리 다음으로 프랑스에서 가장 높은 밀도의 고속도로망 내에 있는 유일한 고속도로다.

가레 드 루바익스 철도역은 앤트워프, 릴, 오스틴드, 파리, 투르코잉과 연결된다.

이 도시는 릴 메트로에서도 운행된다.

환경적 관점

1970년대와 1980년대에 걸쳐 탈산업화는 릴의 아르론분산을 가로지르는 주요 도시경관에 극적으로 영향을 미쳤다.[149]브라운필드 땅의 넓은 지역이 루바ix 시를 표시하기 위해 왔다.지방정부와 국가정부의 지원으로 이들 지역을 획득하여 점차 복원하거나 재건한다.

루바익스는 프랑스에서[150] 가장 효율적인 바이오매스 지역 난방 공장을 가지고 있으며, 따라서 하우츠데프랑스의 지속가능성을 위한 가장 발전된 도시 중 하나이다.시는 2014년부터 순환경제와 제로폐기물 미래로의 이전을 목표로 여러 가지 관련 시책을 펼치고 있다.[151]

저명인사

과학자들

- 스타니슬라스 드헤인(1965–): 인지심리학자, 콜레지 드 프랑스 교수 및 저자

- 버나드 아마데이(1954–): 콜로라도 대학교 토목공학과 교수, 국경 없는 엔지니어(미국) 설립자

- 도미니크 뮬리에즈(1952–): 경구, 고고학자, 헬레니스트

- 마르그리트 뒤피어(1920~2015년): 민족학자

- 로버트 존크에르(1888–1974): 천문학자

- 조셉 윌롯(1875~1919) : 약사 및 제1차 세계대전의 저항운동가

정치인 및 전문가

- 카리마 델리(1979–): 정치가, 유럽의회 의원

- 플로렌스 몰리그헴(1970–): 정치인, 국회의원

- 올리비에 헨노(1962–): 정치인, 생안드레-레즈-릴레 시장 및 일반 의원

- Benoît Duksne(1957–2014): 기자, 텔레비전 기자 및 뉴스 캐스터

- 피에르 프리베티치(1956–): 정치인, 전 유럽의회 의원

- 마리 크리스틴 블랑딘(1952–): 노르드 부서를 대표하는 정치인, 프랑스 원로원 의원

- 장뤼크 브루닌(1951–): 성직자, 로마 가톨릭 르아브르 교구 주교

- 알렉스 튀르크(1950–): 정치가, 노르드 부서를 대표하는 프랑스 원로원 의원

- 베르나르 아르놀트(1949–): 비즈니스 거물, 투자자 및 미술품 수집가

- 브루노 마수레(1947–): 기자, 뉴스 앵커 및 텔레비전 진행자

- 오귀스트 마임렐 (1786–1871), 산업가 및 정치인

- 제라드 뮬리에즈(1931–): 사업가, 백화점의 아우찬 체인 설립자

- 로버트 부지런함(1924~2014): 기자, 테레 룩셈부르크의 창립 멤버

- 프랜시스 폴렛(1964년-): 총경리

- 안드레 부지런(1919–2002):변호사 겸 정치인, 제2차 세계대전 저항운동가, 국회 부의장, 루바익스 상원시장

- 마르셀 베르펠리 (1911년–1945년) : 나치즘에 대항하는 공산주의자, 제2차 세계 대전 저항 운동가, 포로수용소에서 죽었다.

- 피에르 허먼(1910~1990) : 정치인, 국회 부의장

- 피에르 폴림린 (1907–2000): 변호사와 정치인, 제4공화국의 마지막 총리

- 레이먼드 슈미틴(1904~1974) : 토폰리스트 겸 정치인, 국회 부의장

- 장바티스트 레바스(1898~1944): 정치가, 루바익스 시장, 제1차 세계 대전, 제2차 세계 저항 운동가 국회 부의장, 추방 구금 상태에서 사망

- 앙투안 코르도니에(1892~1918): 제1차 세계 대전 중 군용 비행사, 비행 에이스

- 줄스 뒤몬트(1888~1943): 공산주의 무장, XI 국제여단의 부대인 코뮌 드 파리 대대 지휘

- 장 프루보스트 (1885–1978): 사업가, 미디어 소유자 및 정치인

- 아그넬로 판 덴 보쉬(1883–1945):벨기에 시각장애인을 위한 국민작업의 창시자 겸 회장인 벨기에 가톨릭 프란치스코 신부(OFM)가 강제수용소에서 사망했다.

- 루이스 루슈어(1872~1931): 작가와 정치인, 국회 부의장

- 페르디난드 보넬(1865–1945):예수회 사제 및 스리랑카 선교사

- 테오도르 비엔(1864–1921): 섬유 제조업체 및 파리-루바익스 사이클 레이스 공동 설립자

- 외젠 모테(1860~1932): 정치가 및 사업가, 루바익스 시장, 국회 부의장

- 피에르 위보 (1858–1913): 목축업자, 은행가, 금광 소유주, 프랑스에서 미국으로 이민

- 줄스 민브데(1845–1922):파리 태생의 사회주의 언론인 겸 정치인, 루바익스 지역구 국회의원.

- 장 데스보브리(C. 1840-1847-?): 발명가 및 조류 탐지기

- Marie Léonie Vanhoutte(1888 – 1967):제1차 세계대전 당시 프랑스 저항군 전투기와 비밀 요원.

작가

- 마리 데스플친(1959–): 작가 겸 기자

- 피에르 피에라르(1920~2005):역사학자

- Michel Décaudin(1919–2004):로맨스 언어학자, 문학 교수, 작가

- 리처드 콥(1917–1996):영국의 사회사학자1940년대에 루바익스에서 살았다.

- 옥타브 반데커호브(1911–1987): 작가

- Maxence Van Der Meersch(1907–1951): 작가

- 모리스 네돈셀(1905~1976): 개인주의 철학자

- 야네트 델레탕타르디프(1902–1976): 시인

- 아메데 프루보스트(1877–1909): 시인

- 쥘 펠러(1859–1940):로맨스 언어학자 및 언어학자, 벨기에 학술가 및 월룬 전투원

아티스트

- 와나니 그라디 마리아디(1990–): 그라두르로 알려진 래퍼

- 카두르 하다디(1976–): 가수 겸 작가 HK

- 필리프 던트(1965–): 보리스로 알려진 가수, 작곡가

- 아르노 데스플친(1960–): 영화 감독

- 에두아르 드베르나이(1889–1952):오르가니스트, 작곡가

- Wladyslaw Znorko(1958–2013): 연극 작가 및 감독

- 필리프 바라퀘(1954–): 음악학자, 음악 치료사, 작곡가, 가수

- 에티엔 차틸리에즈(1952–): 영화 감독

- 로저 델모트(1925–): 클래식 트럼펫 연주자

- 필리프 르페브르(1949–): 파리 노트르담 대성당의 수석 오르간 연주자

- 샹탈 라데소(1948–): 배우 겸 코미디언

- 아그네스 길레못(1931-2005): 영화 편집자

- 피에르 얀센(1930~2015): 영화음악 작곡가

- 제니 클레브(1930–): 여배우

- 엘리자베스 이본 스캣처드(1928–): 이본느 푸르노로 알려진 영화배우

- 찰스 가덴(1925–2012): 조각가

- 조르주 델러루(1925~1992): 영화와 텔레비전에서 350점 이상을 작곡한 작곡가

- 아서 반 헤케(1924–2003): 화가

- 가브리엘 베베케(1921~2005): 가비 베를러로 알려진 작곡가 겸 가수

- 비비안 로망스(1912–1991): 여배우

- 알버트 드 재거(1908–1992): 조각가, 인쇄업자, 메달리스트 및 제련소

- 찰스 보다르트-티말(1897–1971): 작곡가 겸 샹송니에

- 쥘 그레시에(1897–1960): 지휘자

- 프랜시스 부스케(1890–1942):마르세유 태생의 작곡가

- 레온 마토트 (1886–1968): 영화배우 및 감독

- 사일라스 브루스(1867–1957): 화가

- 장 요제프 베르트스(1846–1927): 화가

- 레미 코게(1846–1927):루바이에 거주하던 벨기에 태생의 화가

- 구스타브 나다우드(1820–1893): 작곡가 겸 샹송니에

선수들

- 와심 아우아흐리아(2000–): 축구 선수

- 무사 나이하카테(1996–): 축구 선수

- 크리스토퍼 마푸비(1994–): 골키퍼

- 사우센 부디아프(1993–): 사브르 펜서

- 앤서니 노커트(1991–): 축구 선수

- 알리우 디아(1990–): 축구 선수

- 앙투안 루셀(1989–): 아이스하키 선수

- 피에릭 건터(1989–): 럭비 유니온 선수

- 이디르 오알리(1988–): 축구 선수

- Magic Mbandjock(1985–): 스프린터

- 세드 키터(1985–): 축구 선수

- 다우다 소우(1983–): 권투 선수

- 예로 디아(1982–): 축구 선수

- 이참 무이시(1982–):알제리의 축구 선수

- 데이비드 쿨리발리(1978–): 축구 선수

- Arnaud Tournant(1978–): 트랙 사이클 선수

- 크리스토프 랜드린(1977–): 축구 미드필더

- 자크 올리비에 파비오(1976–): 축구 선수

- 파티하 오알리(1974–): 경주용 보행기

- 미셸 브리스트로프(1971~1996) : 아이스하키 선수

- 피에르 드레오시(1959–): 전 축구 선수, 코치 및 축구 감독

- 알랭 본듀(1959–): 레이싱 사이클 선수

- 장 크리스티안 랭(1950–): 축구 감독 및 전 선수

- 자크 카르트(1947–): 운동선수

- 르네 리베어(1934–2006): 권투 선수

- 자크 폴렛(1922–1997): 레이싱 드라이버

- 자크 리나르트(1921–2004): 축구 선수

- 프루덴트 조예(1913–1980): 육상 선수

- 조르주 보쿠르(1912–2002): 축구 선수

- 레이먼드 더블리(1893–1988): 축구 선수

- 장 알라보인 (1888–1943): 사이클리스트

- Charles Cruppelandt(1886–1955):와트트렐로스 태생의 프로 도로 자전거 경주 선수

- Arthur Balbaert(1879–1938):벨기에의 스포츠 슈터

참고 항목

참고 및 참조

메모들

- ^ 유대인 루바익스의 인구는 정착 초기 160명에서[67] 1942년 68명으로 줄었다.[68]

- ^ 1940년부터 1944년까지 프랑스 주(州)의 독재정권 하에서 2000명이 넘는 주민을 대상으로 한 공동체의 시장은 민주적으로 선출되지 않았다.시장은 필립 페텐 마샬 정부가 1만 명 이상의 주민들로 구성된 공동체와 1만 명 미만의 주민과 2천 명 이상의 주민들로 구성된 공동체의 프리펫에 의해 지명했다.주민 2,000명도 안 되는 공동체의 시장은 시의회에서 선출되었다.존 인터다이트의 공동체의 시장들은 독일 당국과 합의하여 현관에 의해 지명되었다.그러므로 시장들은 이 기간 동안 정당에 소속되어 있지 않다.[77][78]

- ^ 장바티스트 레바스는 1915년 3월 7일 라스타트 요새에 수감되기 위해 독일 당국에 의해 체포되면서 그의 권한은 중단되었다.

- ^ 앙리 테린 제1부시장은 수감 기간 동안 장바티스트 레바스의 편을 들었다.

- ^ 플뢰리스 반헤르페 시의회 제1부시장(Fleuris Vanherpe)은 1940년 6월 장바티스트 레바스를 몰수당한 후 후임으로 임명되었고, 1940년 12월 18일 시장의 직무를 위임받았다.[79]1941년 8월 17일 그의 죽음은 그의 위임에 일찍 종지부를 찍었다.

- ^ 빅터 프로보는 1942년에 이 명령을 받아들였다.[80]그는 1944년에 저항 위원회에 의해 유지되었다가 1945년 4월에 선출되었다.[81][82]

- ^ 1901년 협회에 관한 법률에 따라 "Comité de Quartier de l'Hommelet"이라고 불리는 지역 협회

- ^ "루바익스는 저항군의 순교자들이 있다" "그들은 억압의 사슬을 끊었다"

- ^ "그의 자식들에게 루바이는 나라를 지키고 평화를 위해 죽었다."

- ^ "정원, 음악, 책의 친구"

- ^ "수영장"

- ^ "제조소"

- ^ 안드레 근면한 미술관

- ^ 박물관에서 열리는 소장품에는 알베르토 지아코메티, 오귀스트 로댕, 카밀 클라우델, 파블로 피카소의 조각품들이 포함되어 있다.

- ^ 망토실

- ^ 국립 안무 센터 루바익스 - 오츠 드 프랑스

참조

- ^ "Répertoire national des élus: les maires". data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises (in French). December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ "Populations légales 2019". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. December 29, 2021.

- ^ Pooley, Timothy (December 30, 1996). Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France. Applications in French Linguistics Series. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd. pp. 15–44. ISBN 978-1-853-59345-1. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ Lecigne, Constantin (1911). Amédée Prouvost (in French). Paris, F: Bernard Grasset. p. 71. OCLC 679906866. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

Roubaix donne l'impression d'une enclave américaine dans la France du Nord. C'est en même temps la ville de l'énergie frénétique et des fuites à travers le monde.

- ^ Strikwerda, Carl (1984). Sweets, John F. (ed.). "Regionalism and Internationalism: The Working-Class Movement in the Nord and the Belgian Connection, 1871–1914". Proceedings of the ... Annual Meeting of the Western Society for French History. 1983/1984. Lawrence (Kansas), USA: The University of Kansas: 222. hdl:2027/mdp.39015012965524. ISSN 0099-0329.

Contemporaries never tired of calling Roubaix an "American city," because of its raw, fast-growing character, or of referring to Roubaix and its sister cities of Lille and Tourcoing as the "French Manchester."

- ^ Clark, Peter (January 29, 2009). European Cities and Towns: 400–2000. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-199-56273-2. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

Roubaix was another new town, originally a craft village, whose many textile mills attracted a population of 100,000 and generated massive social and environmental problems.

- ^ a b Téléchargement du ficier d'enseemble des popular légales in 2019, INSEEE

- ^ Lecluyse, Frédérick (December 16, 2016). "MEL : on prend les mêmes ou presque et on recommence" [MEL: let's take the same ones, or almost, and start over]. La Voix du Nord (in French). Roubaix, F. 73 (349, ROUBAIX & SES ALENTOURS): 4. ISSN 1277-1422.

Bois-Grenier, Le Maisnil, Fromelles, Aubers et Radinghem-en-Weppes. Soit 6000 habitants supplémentaires pour une MEL qui compte désormais 90 communes…

- ^ Ezelin, Perrine (April 2, 2015). "European Metropole of Lille Local Action Plan" (PDF). Edinburgh, UK: CSI Europe URBACT. p. 3. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ URBACT (May 29, 2015). "Lille". Edinburgh, UK. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Neveu, Clarisse (December 15, 2016). "Métropole Européenne de Lille : les vice-présidents et conseillers métropolitains délégués élus" [European Metropolis of Lille : elected vice-presidents and metropolitan delegate-councilors]. MEL. Communiqué de presse (in French). Lille, F: Métropole Européenne de Lille. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

La fusion, effective au 1er janvier 2017, acte un élargissement historique du territoire de la Métropole Européenne de Lille, passant de 85 à 90 communes pour près d'1.2 million d'habitants.

- ^ Durand, Frédéric (May 12, 2015). "Theoretical framework of the cross border space production the case of the Eurometropolis Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai" (PDF). Luxembourg, L: EUBORDERSCAPES. p. 18. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Geographical Section of the Naval Intelligence Division, Naval Staff, Admiralty I.D. 1168. (February 1918). Hall, Frederick (ed.). A Manual of Belgium and the Adjoining Territories. Atlas. Oxford, UK: University Press, HMSO. p. 37. OCLC 10569037. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 작성자 매개변수 사용(링크) - ^ Jäger, Martin (January 12, 2011). "Entfernungen (Luftlinie & Strecke) einfach online berechnen, weltweit" [Calculate distance between two cities in the world (free, with map)] (in German). Ascio Technologies, Inc. Danmark – Filial af Ascio technologies, Inc. USA. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Dercourt, Jean; Paquet, Jacques (December 6, 2012) [First published 1985]. Geology: Principles and Methods. Oxford, UK: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 328. ISBN 978-9-400-94956-0. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Hack, Robert; Azzam, Rafig; Charlier, Robert (June 14, 2004). Engineering Geology for Infrastructure Planning in Europe: A European Perspective. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences. Vol. 104. Berlin, D: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 605–606. doi:10.1007/b93922. ISBN 978-3-540-21075-7. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ a b 데 카시니 보조 코뮌: 코뮌 데이터 시트 루바ix, EHSS(프랑스어)

- ^ The Sanitary Record and Journal of Sanitary and Municipal Engineering. Vol. 47. London, UK: Sanitary Publishing Company. 1911. p. 3. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ United States, Dept.'s Bureau of Foreign Commerce (1898). Commercial relations of the United States with foreign countries. Congressional Edition. Vol. 3695. Washington, US: Govt. Printing Office. p. 63. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

…and with the Deule by the Canal d'Espierre and that of Roubaix

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 작성자 매개변수 사용(링크) - ^ Nothomb, M. (1838). Canal de Bossuyt à Courtray & projets, annexes, enquêtes, etc … [Bossuit-Kortrijk Canal & projects, appendix, surveys, etc…] (in French). Brussels, B: H. Rémy, imprimeur du roi. p. 17. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

Le but primitif du canal était de fournir à la ville de Roubaix les eaux dont elle manquait, et de la mettre en communication avec le système de canaux du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais.

- ^ Lille Metropolitan Council (2008). Ruant, Olivia; Edwards-May, David (eds.). "A strategic route, an economic necessity". EU programme Blue Links: restoration and reopening of the Deûle-Escaut canal between France and Belgium: Roubaix Canal, Espierre Canal and Marque canalised river. Lille Métropole Communauté Urbaine. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ McKnight, Hugh (August 1, 2013) [1st pub. 1984]. Cruising French Waterways. London, UK: Adlard Coles Nautical. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-408-19796-7. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Marion Gadault, Teddy Grandsire, Patrice Gonzalez, Laure Join-Lambert, Dominique Leonardi, Véronique Malek, Carmen Momenceau, Nathalia Momenceau, Catherine Ruget (2015). Devisme, Philippe; Join-Lambert, Patrick (eds.). "From Marquette to la frontière Belge". Fluviacarte, cartes et guides pour la navigation intérieure. Lattes, F: Editions de l'Écluse. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : 복수이름 : 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Aime Cadot for the American Baptist Missionary Union (1899). "European Missions France – 1832". Eighty-fifth Annual Report. Baptist Missionary Magazine. Vol. 84–87. Boston (Massachusetts), USA: Missionary Rooms. p. 387. hdl:2027/wu.89082422338.

The evening of our visit at Roubaix the weather was dreadful – rain and cold wind.

- ^ American McAll Association (1893). Annual Meeting of the American McAll Association. Vol. 10–18. Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), USA. p. 66. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

In the winter, Mrs. Tyng visited us and told us more about Roubaix, but, owing to the extremely cold weather, her audience was small.

- ^ Lille Métropole Communauté Urbaine (October 8, 2004). "Présentation générale du territoire communautaire et environnement du 8 octobre 2004 (Titre I – présentation générale du site et caractéristiques géophysiques)" (PDF). PLU de Lille Métropole. RAPPORT DE PRESENTATION (in French). Lille, F: LMCU. pp. 17–18. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ Decker, Frédéric, ed. (2015). "Lille (Nord)". LaMétéo.org. Normales climatiques 1981–2010 (in French). Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ "Lille-Lesquin (59) – altitude 47m". ASSOCIATION INFOCLIMAT. Normes et records 1961–1990 (in French). 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ Guinet, Louis (1982). Les emprunts gallo-romans au germanique (du Ier à la fin du Ve siècle) [The Gallo-Romance borrowings from Germanic (from the 1st century to the end of the 5th century)]. Bibliothèque française et romane. Série A, Manuels et études linguistiques; 44 (in French). Paris, F: Klincksieck. pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Nègre, Ernest (1996) [1st pub. 1991]. Toponymie générale de la France, vol. 2 [General Toponymy of France, Vol II] (in French). Geneva, CH: Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-00133-5. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ a b van Overstraeten, Jozef (1969). De Nederlanden in Frankrijk [Low Countries in France]. Beknopte encyclopedie (in Dutch). Antwerp, B: Vlaamse Toeristenbond. pp. 465–466. OCLC 901682478. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

…881 of 887 villa Rusbaci ≺ Germ. rausa = riet + baki = beek…

- ^ Trénard, Louis; Diligent, André (1984). Hilaire, Yves-Marie (ed.). Histoire de Roubaix [History of Roubaix]. Collection Histoire des villes du Nord/Pas-de-Calais (in French). Vol. 6. Dunkerque, F: Éditions Des Beffrois : Westhoek-Editions. p. 10. ISBN 978-2-903-07743-3. OCLC 14127874. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Gastal, Pierre (2002). Sous le français, le gaulois: Histoire, vocabulaire, étymologie, toponymie [Gallic under the French: History, vocabulary, etymology, toponymy] (in French). Méolans-Revel, F: Éditions Le Sureau. ISBN 978-2-911-32807-7. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Gysseling, Maurits (1960). "Toponymisch Woordenboek van België, Nederland, Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk en West-Duitsland (vóór 1226) door Maurits Gysseling (1960)" [Toponymic dictionary of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Northern France and Western Germany (before 1226) by Maurits Gysseling (1960)] (in Dutch). Centrum voor Teksteditie en Bronnenstudie. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ van den Broecke, Marcel; van den Broecke-Günzburger, Deborah, eds. (2008). "Cartographica Neerlandica Topographical names for Ortelius Map No. 76". Cartographica Neerlandica. FLANDRIA "Gerardus Mercator Rupelmundanus Describebat" [Flanders, which Gerardus Mercator from Rupelmonde has depicted] "Cum priuilegio" [With privilege]. Bilthoven, NL: Marcel & Deborah van den Broecke. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Tilly, Louise; Tilly, Charles (June 1, 1981). Class Conflict and Collective Action. New Approaches to Social Science History. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks (California), USA: Sage Publications. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-803-91587-9. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

In some areas of France, Flemish was spoken by the natives; but since Roubaix lies just outside French Flanders, native Roubaisians spoke only French, hence the language disparity.

- ^ Schuermans, Lodewijk Willem (1865). Algemeen Vlaamsch idioticon, Met Tijd en Vlijt [General Flemish idioticon, with time and assiduity] (in Dutch). Leuven, B: Gebroeders Vanlinthout. p. 268. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Fortuné, Raymond (1899). Histoire du Hainaut français et du Cambresis [History of the French Hainaut and Cambresis] (in French). Paris, F: Editions Paul Lechevalier. p. 61. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Kolff, Gualtherus Johannes (October 28, 1914). "De Belgische Plaatsnamen" [Belgian place names]. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). G.J. Kolff & Co.: 6. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Schuermans, Lodewijk Willem; David, Jan Baptist; Du Bois, Pierre (1883). Bejvoegsel : aan het Algemeen Vlaamsch idioticon uitgegeven in 1865-1870 [General Flemish idioticon issued in 1865-1870] (in Dutch). Leuven, B: K. Fonteyn. p. 268. OCLC 23400838. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

ROBAAIS, zoo las ik ergens vertaald den naam der fransche stad Roubaix, 't welk beter Roobeek of Robeke zou zijn

- ^ "Buitenlandse Aardrijkskundige Namen" [Foreign Geographical Names] (in Dutch). taaladvies.net. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Leuridan, Théodore (1862). Histoire des seigneurs et de la seigneurie de Roubaix [History of the lords and lordships of Roubaix]. Histoire de Roubaix (in French). Vol. 3. Roubaix, F: Imprimerie J. Reboux. p. 24. OCLC 466447211. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ Ireland, Patrick Richard (January 1, 1994). The Policy Challenge of Ethnic Diversity: Immigrant Politics in France and Switzerland. Cambridge (Massachusetts), USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-68375-4. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

Even very large immigrant communities managed to integrate into the ranks of the Roubaignos (native Roubaisians) through their membership in the working class.

- ^ a b Landrecies, Jacques (March 2001). Boutet, Josiane (ed.). Cairn.info. "Une configuration inédite : la triangulaire français-flamand-picard à Roubaix au début du XXe siècle" [An original configuration: the French-Flemish-Picard linguistic triangle in Roubaix at the start of the 20th century]. Langage et Société (in French). Paris, F: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. 97 (3): 27–69. doi:10.3917/ls.097.0027. ISBN 978-2-735-10894-7. ISSN 0181-4095. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

{{cite journal}}:외부 링크 위치others= - ^ Bowen, Reginald (1937). La formation du féminin de l'adjectif et du participe passé dans les dialectes normands, picards et wallons d'après l'Atlas linguistique de la France [The Feminine formation of adjectives and past participles in Norman, Picard and Wallon dialects according to the Linguistic Atlas of France] (in French). Paris, F: Librairie Droz. OCLC 252979177.

- ^ a b c Marissal, Louis-Edmond (1844). Recherches pour servir à l'histoire de Roubaix de 1400 à nos jours (in French). Roubaix, F: Impr. de Beghin. pp. 108–109. OCLC 253762961. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

1716: 4 715; 1789: 8 559; 1801: 8 151; 1805: 8 703; 1817:8 724; 1830: 13 132; 1842: 24,892

- ^ de Félix, Louis-Nicolas-Victor (1764). Mémoires sur les frontières et places de la Flandre, du Haynault, du pays entre Sambre et Meuze, du Calaisis, de l'Artois, du cours de la Somme et des Trois-Évèchez jusques à l'Alsace (manuscript). Français 11409. p. 969.

- ^ 역사 속의 인구 감소 1968, INSEEE

- ^ Declercq, Elien; Vanden Borre, Saartje (2013). Cultural integration of Belgian migrants in northern France (1870–1914): a Study of Popular songs. French History. Vol. 27. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 91–108. doi:10.1093/fh/crs123. ISSN 1477-4542. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Guerin-Gonzales, Camille; Carl, Strikwerda (1998). The Politics of Immigrant Workers: Labor Activism and Migration in the World Economy Since 1830 (2 revised ed.). New York (New York), USA: Holmes & Meier. pp. 115–133. ISBN 978-0-841-91298-4. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

All Merrheim's years living in a French city that was over a third Belgian never made him question the ability of workers of different nationalities to unite.

- ^ de Planhol, Xavier; Clava, Paul (1994). An Historical Geography of France. Cambridge Studies in Historical Geography. Vol. 21. Cambridge (New York), USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-521-32208-9. ISSN 1747-3128. OCLC 27266536. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Ministère des affaires étrangères du royaume de Belgique (1873). Recueil consulaire, contenant les rapports commerciaux des agents belges à l'étranger. Vol. 19. Brussels, B: P. Weissenbruch, Imprimeur du Roi. p. 971. ISBN 9780521322089. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

D'après un recensement récent, la population de Roubaix s'élève aujourd'hui à 75,987 habitants, dont 42,103 belges. En 1866 le recensement accusait une population totale de 64,706 habitants, dont 30,465 belges.

- ^ Moch, Leslie Page (2003) [First published 1992]. Moving Europeans: Migration in Western Europe Since 1650. Interdisciplinary studies in history (Second ed.). Bloomington (Indiana), USA: Indiana University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-253-21595-6. OCLC 50774361. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Stone, David (June 1, 2015). The Kaiser's Army: The German Army in World War One. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-844-86235-1. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ Kramer, Alan (July 12, 2007). Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-192-80342-9. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

The death rate is high; in ordinary times two gravediggers were enough in Roubaix, and now there are six of them

- ^ Tilly, Charles (July 1983). Collective-action repertoires in five French provinces, 1789–1914 (PDF). CRSO Working Paper. Vol. 300. Ann Arbor (Michigan), USA: University of Michigan. p. 17. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

In fact, the population of Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing, a combat zone in World War I, fell slightly between 1901 and 1921.

- ^ Landrecies, Jacques; Petit, Aimé (April 1, 2003). "Picard d'hier et d'aujourd'hui" [Yesterday's and today's Picard]. Bien dire et bien aprandre – Bulletin du Centre d'études médiévales et dialectales de l'Université de Lille III (in French). Villeneuve d'Ascq, F: Centre de Gestion de l'Édition Scientifique (CEGES) (21): 11. ISBN 978-2-907-30105-3. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

…aborder le difficile problème de l'"accent", cette dernière marque qui subsiste quand le patois a disparu et qui, plus que tout, permet de distinguer l'Abbevillois de l'Artésien ou du "Roubaignot".

- ^ Pooley, Timothy (December 30, 1996). Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France. Applications in French Linguistics Series. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd. pp. 104–140. ISBN 978-1-853-59345-1. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Pooley, Timothy (October 9, 2002). "The depicardization of the vernaculars of the Lille conurbation". In Jones, Mari C.; Esch, Edith (eds.). Language Change: The Interplay of Internal, External, and Extra-linguistic Factors. Contributions to the sociology of language. Vol. 86. Berlin, D: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-110-17202-7. ISSN 1861-0676. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

Viez notes the enduring prevalence of Picard in Roubaix in the early twentieth century despite progressive francization favoured by urbanization and industrialization

- ^ Viez, Henri-Aimé (1978) [1st pub. 1910]. Le parler populaire patois de Roubaix : étude phonétique [Patois of Roubaix: a phonetic study of the popular dialect] (in French). Geneva, CH: Slatkine Reprints. p. 7. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

…du parler populaire de Roubaix, tel qu'il était couramment employé avant que l'instruction primaire ne fût devenue obligatoire.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam (May 9, 1994). "A Reporter at Large: The Ghost of the Glass House". The New Yorker. New York (New York), USA: F-R Publishing Corporation: 58. ISSN 0028-792X.

Many of them had German names. They had fled from Alsace-Lorraine as the Franco-Prussian War ended, in 1871.

- ^ Gilbert, Barbara C.; Fishel Deshmukh, Marion (September 30, 2005). Max Liebermann: from realism to impressionism. Los Angeles (California), USA: Skirball Cultural Center. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-970-42956-8. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

After Alsace-Lorraine territory is annexed by the German Empire, thousands of Alsatian Jews emigrate to France.

- ^ Reboux, Alfred, ed. (October 5, 1872). "Roubaix et le nord de la France" [Roubaix and northern France] (PDF). Journal de Roubaix (in French). Roubaix, F. 17 (3052): 2. Retrieved December 4, 2017 – via Bibliothèque numérique de Roubaix.

- ^ a b c d Viey, Frédéric; d'Almeida, Franck (June 2009). Histoire des communautés juives du Nord et de Picardie [History of the Jewish Communities of the North and Picardy Regions] (in French). Valenciennes, F: Synagogue de Valenciennes. pp. 24–25. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ Cahen, Isidore; Prague, Hippolyte (1894). Archives israélites – Recueil politique et religieux [Israelite Archive – Political and religious reports] (in French). Vol. Tome LV. Paris, F: Bureau des Archives Israelites. p. 23. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

M. Maurice Marx, fils du ministre-officiant de la Synagogue de Roubaix, a été nommé dans le courant de novembre au commandement de la canonnière l'Onyx. Ce jeune officier est un ancien élève de l'École polytechnique.

- ^ a b c Delmaire, Danielle (2001). Les communautés juives septentrionales, 1791–1939 : Naissance, croissance, épanouissement [Jewries in Northern France from 1791 to 1939: birth, growth, development] (in French). Vol. 2. State doctoral thesis – Charles de Gaulle University – Lille III – January 1998. Villeneuve d'Ascq, F: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion. pp. 714–719. ISBN 978-2-284-01645-8. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Renoul, Bruno (September 10, 2015). "Roubaix commémore l'époque où elle avait une synagogue" [Roubaix commemorates the time when it had a synagogue]. La Voix du Nord (in French). Roubaix, F. ISSN 0999-2189. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ Wigoder, Geoffrey; Spector, Shmuel (January 1, 2001). "K-Sered – Roubaix". The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust. Vol. 2. New York (New York), USA: New York University Press. p. 1098. ISBN 978-0-814-7935-65. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ Michman, Dan (May 1998). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans. Jerusalem: Daf-Noy Press. pp. 335–336. ISBN 978-9-653-08068-3.

A massive round-up, i.e., large-scale random arrests, of Jews in northern France was conducted on September 11, 1942, at the same time as the one in Antwerp […] On October 27, 1943, the Germans arrested two Jewish families in Croix and Roubaix.

- ^ Wieviorka, Michel; Bataille, Philippe (September 2007). The Lure of Anti-Semitism: Hatred of Jews in Present-Day France. Jewish Identities in a Changing World. Vol. 10. Translated by Couper Lobel, Kristin; Declerck, Anna. Leiden, NL: Brill Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 978-9-004-16337-9. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

Roubaix does not have a Jewish community and there is no Jewish place of worship, intra muros.

- ^ Johannsen Rubin, Alissa (August 5, 2013). "A French Town Bridges the Gap Between Muslims and Non-Muslims". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

In Roubaix, the mayor's office estimates that the Muslim population is as much as 20,000, or about 20 percent of the population.

- ^ Gilman, Julien (October 31, 2014). "Roubaix: la Ville veut vendre douze chapelles funéraires abandonnées" [The City of Roubaix is willing to sell twelve abandoned funeral chapels]. La Voix du Nord (in French). Roubaix, F. ISSN 0999-2189. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Liogier, Raphaël (March 29, 2004). Le bouddhisme mondialisé: Une perspective sociologique sur la globalisation du religieux [Globalised Buddhism: A sociological perspective on the globalisation of religions]. Référence géopolitique (in French). Paris, F: Ellipses Marketing. p. 268. ISBN 9782729814021. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Centre francophone d'étude et d'enseignement sur le bouddhisme (2006). "Annuaire des Centres bouddhistes : Nord - Pas-de-Calais" [Directory for Buddhist communities: Nord - Pas-de-Calais]. Institut d’Études Bouddhiques (in French). Paris, F: IEB. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Leuridan, Théodore (1863). Histoire des institutions communales et municipales de la ville de Roubaix. Histoire de Roubaix (in French). Vol. 4. Roubaix, F: Imprimerie J. Reboux. p. 92. OCLC 466447211. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ^ Tellier, Thibault (March 16, 2006). "Le développement urbain de Roubaix dans la première partie du XXe siècle". In David, Michel (ed.). Roubaix: cinquante ans de transformations urbaines et de mutations sociales [Fifty years of urban transformations and social mutations in Roubaix]. Histoire et civilisations (in French). Vol. 972. Villeneuve d'Ascq, F: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion. p. 43. ISBN 978-2-859-39926-9. ISSN 1284-5655. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

…c'est en fait le développement vers le sud qui semble le plus prometteur…

- ^ État français (December 12, 1940). "Loi du 16 novembre 1940 RELATIVE A LA REORGANISATION DES CORPS MUNICIPAUX" [Law of November 16, 1940 RELATED TO REORGANISATION OF MUNICIPAL BODIES]. Journal Officiel de la République Française (in French). Imprimerie nationale: 6074.

- ^ Pottrain, Martine (1993). Le Nord au cœur: historique de la Fédération du Nord du Parti socialiste, 1880–1993 [Nord at heart: history of the French socialist party federation of the Nord, 1880–1993] (in French). Lille, F: SARL de presse Nord-Demain. OCLC 34886141.

La loi de Vichy du 16 novembre 1940 réorganise l'administration communale : les maires et les conseillers municipaux sont désignés par le préfet, après accord des autorités allemandes.

- ^ Piat, Jean (1985). Victor Provo : 1903–1983 : Roubaix témoigne et accuse (in French). Dunkerque, F: Éditions Des Beffrois. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-903-07747-1. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

Toutefois, Jean Lebas restera suspendu et le poste de maire sera confié, le 18 décembre 1940, au plus ancien adjoint : Fleuris Vanherpe.

- ^ Jackson, Julian (April 26, 2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-62288-5. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

The pre-war mayor of Roubaix, Jean Lebas, who was involved in the Resistance from the beginning, had no qualms about encouraging his Socialist colleague Victor Provo to accept the post of mayor in 1942 on the grounds that the alternatives might be worse.

- ^ Thyssen Geert, Herman Frederik, Kusters Walter, Van Ruyskensvelde Sarah, Depaepe Marc (December 20, 2010). "From popular to unpopular education? The open-air school(s) of "Pont- Rouge", Roubaix (1921–1978)". History of Education & Children's Literature (PDF). Macerata, I: Edizioni Università di Macerata. p. 203. ISBN 978-88-6056-252-4. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

…he was replaced successively by Fleuris Vanherpe, Marcel Guislain, Alphonse Verbeurgt, Charles Baudoin and Victor Provo. The latter, who was appointed by the Vichy regime, would be reinstalled as mayor of Roubaix after the war and govern the city from 1944 until 1977.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 작성자 매개변수 사용(링크) - ^ Luquiens, Corinne, ed. (2011). "Base de données des députés français depuis 1789 – Victor PROVO" [Database on members of the French National Assembly since 1789 – Victor PROVO]. Base de données historique des anciens députés (in French). Paris, F: Assemblée nationale. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures". Commission nationale de la coopération décentralisée (in French). France Diplomatie. 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Piat, Jean (1985). Victor Provo : 1903–1983 : Roubaix témoigne et accuse (in French). Dunkerque, F: Éditions Des Beffrois. p. 124. ISBN 978-2-903-07747-1. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Catrice, Paul; Provo, Victor; Trénard, Louis; Teneul, Georges-François (1969). Roubaix au-delà des mers (in French). Roubaix, F: Société d'émulation de Roubaix. p. 26. OCLC 493340579. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Skopje – Twin towns & Sister cities". Official portal of City of Skopje. Grad Skopje – 2006 – 2013, skopje.gov.mk. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Passarelli, Pasquale (1999). Toscana. Comuni d'Italia (in Italian). Monteroduni (Isernia), I: Istituto enciclopedico italiano. p. 293. ISBN 978-8-887-98326-5. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Roubaix". Sosnowiec laczy. Urzad Miejski w Sosnowcu. June 9, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ^ "ROUBAIX (França)". Covilhã Município (in Portuguese). Câmara Municipal da Covilhã. October 20, 2000. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Vermeersch, Olivier (April 2013). "The Québec's deleguation attends CETI's official inauguration – La délégation Québécoise à l'inauguration officielle du CETI". La Revue du Textile – the Textile Journal. CTT Group. 130 No. 1 (HIGHTEX): 38. ISSN 0008-5170. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Tasca, Catherine (December 13, 2000). "Allocution de Catherine Tasca – Ville de Noisiel : Signature de la convention VILLE ET PAYS D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE" (in French). Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c Kapferer, Jean-Noël (January 3, 2008). The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term. The New Strategic Brand Management. London, UK: Kogan Page. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-749-45085-4.

- ^ Artconnexion (June 5, 2010). "Wim Delvoye / Discobolos". Artconnexion: contemporary art production and mediation consultants. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Société internationale des Nouveaux commanditaires (2010). Legierse, Thérèse (ed.). "Wim Delvoye – Discobolos". Les Nouveaux Commanditaires. Brussels, B. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mairie de Roubaix (2009). "Roubaix : Parc Barbieux et Grand Boulevard" (PDF). Roubaix, F: Mairie de Roubaix. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Médiathèque de Roubaix (1980). "Monument Jean Lebas". Bibliothèque numérique de Roubaix (in French). Roubaix, F: Mairie de Roubaix. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Piat, Jean (1985). Victor Provo : 1903–1983 : Roubaix témoigne et accuse (in French). Dunkerque, F: Éditions Des Beffrois. p. 50. ISBN 978-2-903-07747-1. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

Le 11 novembre 1948, le ciseau du grand prix de Rome, le Roubaisien Albert de Jaeger, grava leur souvenir dans la pierre d'un monument Aux Martyrs de la Résistance, érigé sur l'ancienne place Chevreul.

- ^ a b "L'hommage de Roubaix au peintre J.J. Weerts". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Paris, F: 1. November 30, 1931. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Ramspacher, Émile-Georges (1863). Le général Estienne: "père des chars". Portrait et aspect de l'histoire (in French). Vol. 2. Paris, F: Éditions Charles-Lavauzelle. p. 65. ISBN 978-2-702-50036-1. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ^ Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion (April 21, 2015). "Monument à Roubaix". Les monuments aux morts France et Belgique (in French). Laboratoire UMR CNRS IRHiS Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion Université de Lille. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Social Democratic Federation (1925). Social-democrat: Incorporating Justice. Vol. 42 to 44. London, UK: Executive Committee of the Social-Democratic Federation. p. 32. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

In Roubaix, which has a Socialist majority on the town council, a memorial will be unveiled on Easter Sunday, in honour of Jules Guesde, the great pioneer of Marxian Socialism in France.

- ^ "Monument à Jules Guesde – Roubaix". 2015 E-monumen (in French). E-monumen.net Base de données Géolocalisée du patrimoine monumental Français et Étranger. December 17, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ "Monument à Pierre Destombes – Roubaix". 2015 E-monumen (in French). E-monumen.net Base de données Géolocalisée du patrimoine monumental Français et Étranger. December 16, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ "Monument à Gustave Nadaud – Roubaix". 2015 E-monumen (in French). E-monumen.net Base de données Géolocalisée du patrimoine monumental Français et Étranger. December 21, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (October 21, 2018). "France's art deco jewel is reborn to make an even bigger splash". The Guardian.

- ^ Dunthorne, Hugh; Wintle, Michael (November 1, 2012). The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Britain and the Low Countries. National Cultivation of Culture. Vol. 5. Leyden, NL: Brill. pp. 204–208. ISBN 978-9-004233-79-9. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Ronet, Marc; Gaudichon, Bruno (2005). Marc Ronet (in French). Gent, B: Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon. p. 12. ISBN 9789053495933. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ Cordonnier, Aude; Ceysson, Bernard (2005). Collection du Lieu d'art et action contemporaine de Dunkerque [Collection of the Lieu d'art et action contemporaine of Dunkirk] (in French and English). Paris, F: Somogy Editions d'Art. pp. 194–330. ISBN 978-2-85056-871-8. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ Médiathèque de Roubaix (July 2, 2010). "Le groupe de Roubaix : Un choix dans les collections de La Piscine". La Piscine – Musée d'Art et d'Industrie André Diligent (in French). Roubaix, F: Ville de Roubaix. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Cordonnier, Aude; Jaubert, Bruno (November 11, 1998). Arthur van Hecke : œuvres 1946–1998 (in French). Dunkirk, F: Dunkerque : Musée des Beaux-Arts. ISBN 978-2-906363-11-3.

- ^ Delporte, Michel; Gaudichon, Bruno; Vandierendonck, René (December 20, 1997). Le Groupe de Roubaix : Le Nord Pas-de-Calais s'ouvre : l'art contemporain, 1946–1970. Cahier du patrimoine roubaisien (in French). Vol. 3. Roubaix, F: Musée d'art et d'industrie de Roubaix.

- ^ Verbeke, Dirk (1989). "De Franse Nederlanden: actualiteiten" [The French Netherlands: News]. Ons Erfdeel. Jaargang 32 (in Dutch). Raamsdonksveer, NL: Stichting Ons Erfdeel. Deel 2: 299. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

Leroy, Roulland en Van Hecke behoorden tot de 'Groep van Roubaix'.

- ^ "Présentation". Maisons de Mode. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ H.J. (November 13, 2014). Dupiereux, Thierry (ed.). "Louise Bourgoin et Jean-Hugues Anglade tournent à Lessines". L'info sur lavenir.net (in French). Liège, B: Éditions de l'Avenir. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Lelièvre, Adrien (August 25, 2014). "Roubaix, le "paradis perdu" du cinéaste Arnaud Desplechin". La Voix du Nord (in French). Roubaix, F. ISSN 0999-2189. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Le Bas, Christophe (May 12, 2015). "Roubaix – Tourcoing : ces 5 films qui font de nos villes leur décor idéal". La Voix du Nord (in French). Roubaix, F. ISSN 0999-2189. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Dulas, Régis, ed. (January 2015). ""Discount" vu par son équipe". e-clap.fr (in French). Hellemmes, F: E-clap, Amoureux de tous les cinemas. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Joos, Olivier (May 15, 2012). "Les Reines du ring en tournage à Roubaix, Le Portel…". cinemasdunord.blogspot.com (in French). Olivier JOOS on Blogger. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Rousseaux, Céline (June 24, 2013). ""Les reines du ring", film sur le catch tourné dans le Nord Pas-de-Calais, en avant-première ce lundi à Lomme". france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr (in French). Lille, F: France Télévisions. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Nisha, Joseph, ed. (2013). "'Blue Is the Warmest Colour' Coloured with Palme d'Or in 66th Festival De Cannes". All Lights Film Magazine. Dubai, UEA. Retrieved July 12, 2015.[영구적 데드링크]

- ^ Grenu, Leïla (April 18, 2013). Leclercq, Vincent (ed.). "Un film tourné et coproduit en Nord–Pas de Calais en compétition officielle du Festival de Cannes !" (PDF) (in French). Tourcoing, F: PICTANOVO. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Saint-Alban, Clotilde (ed.). "Le Nord-Pas-de-Calais et le cinéma" (in French). Prémesques, F: Ancêtres et Histoire. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Агаронян, Армине (July 2009). Андрей Звягинцев покорил Ереван [Andrey Zvyagintsev won Yerevan] (in Russian). Moscow, RU: Международная еврейская газета (МЕГ) – International Jewish Newspaper (IJN). Retrieved July 12, 2015.

…и кто-то посоветовал, городок Рубе на севере Франции. Это оказалось именно тем, что мы искали…

- ^ "Le bannissement (2007) Filming Locations". Seattle (Washington), USA: IMDb.com, Inc. February 6, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Le rendez-vous de Séraphine". amisdelapiscine.blogspot.fr (in French). Les Amis de la Piscine on Blogger. January 18, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Le couperet (2005) Movie". Singapore, SG: MoviePictures.ORG Movies Hollywood Free. 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Sardet, Yoann, ed. (2000). "Sauve-moi (Secrets de tournage) De l'écrit à l'image…" (in French). Paris, F: AlloCiné SA. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Jauffret, Magali (April 28, 1999). "Robert Kramer : " Je suis un homme aveuglé "" (in French). L'Humanité.fr. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Le Monde (November 13, 1999). "An American in Roubaix". www.windwalk.net. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Kaganski, S.; Bonn, F. (September 16, 1998). "Erick Zonca – Une nouvelle vie" (in French). Les Inrocks. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, Martin (January 15, 2008). The New Face of Political Cinema: Commitment in French Film since 1995. Oxford (New York), USA: Berghahn Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-857-45690-8. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ "Temporale Rosy (1980) Movie". Singapore, SG: MoviePictures.ORG Movies Hollywood Free. 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Deroy, Pascal, ed. (1994). "Le Maître-nageur" (in French). Wattignies, F: CinEmotions.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Godard part II: 1968–1974 – The Mao years". Rate Your Music. Seattle (Washington), USA: Sonemic, Inc. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Vandenbussche, Robert (2000). 1896–1996, Cent ans d'université Lilloise: actes du colloque organisé à Lille, les 6 et 7 décembre 1996 [1896–1996, one hundred years of the University of Lille: proceedings of the symposium held on November 6 and 7, 1996 at Lille]. Centre d'Histoire de l'Europe du Nord-Ouest (in French). Vol. 18. Villeneuve d'Ascq, F: Université Charles-de-Gaulle – Lille III / CRHEN-O. p. 225. ISBN 978-2-905-63734-5. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Jerome, Jerome Klapka; Pain, Barry, eds. (1899). To-day. Vol. 22. London, UK: W.A. Dunkerley. p. 215. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

The sport is very popular in the North of France, some fifty odd clubs existing in or near Roubaix, where a very large meeting was recently held.

- ^ Waret, Philippe; Popelier, Jean-Pierre (July 1, 2005). Sutton, Alan (ed.). Roubaix: ville de sport [Roubaix: a sporting city]. Mémoire du sport (in French). Saint-Avertin, F: Éditions Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-2-84910-155-1.

- ^ Brévan, Claude (June 2002). The URBAN Community Initiative (PDF). Sainte-Denis, F: Interministerial Delegation for Urban Affairs. p. 57. ISBN 2-11-093-339-9. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Hussey, Andrew (April 14, 2012). "France: a divided nation goes to the polls". The Guardian. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Agnew, Harriet (December 13, 2018). "Can France revive its industrial heartland?". Financial Times.

- ^ Smith, Michael Stephen (February 14, 2006). The Emergence of Modern Business Enterprise in France, 1800–1930. Harvard studies in business history. Vol. 49. Cambridge (Massachusetts), USA: Harvard University Press. p. 489. ISBN 978-0-674-01939-3. ISSN 0073-067X. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

One of these was Pinault-Printemps-Redoute, a major retailing firm created by the merger of the Printemps-Prisunic department store chain and La Redoute, a leading mail-order house founded by a family of Roubaix wool spinners in the 1920s.

- ^ Baren, Maurice (September 16, 1992). How it all began: the stories behind those famous names. Leeds, UK: Smith Settle. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-870-07192-5. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

In the French town of Roubaix in the 1950s, three brothers, members of the Despature family, had a weaving business manufacturing fine woollen cloths.

- ^ Derdak, Thomas (2009). Grant, Tina (ed.). International Directory of Company Histories. Gale virtual reference library. Vol. 98. Farmington Hills (Michigan), USA: St. James Press. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-1-558-62619-5.

- ^ Dubois, Guy (October 11, 2012). Le Nord Pas-de-Calais Pour les Nuls [Nord Pas-de-Calais for dummies]. Pour les Nuls Culture Générale (in French). Paris, F: Éditions First & First Interactive. p. 164. ISBN 978-2-754-03547-7.

- ^ Prouvost, Thierry (August 15, 2008). "Vision et génie international des "familles du Nord" et de Roubaix en particulier" (in French). Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

C'est en 1932, à Roubaix, que Xavier Toulemonde crée les Filatures des 3 Suisses, qui deviendront par la suite les 3 Suisses.

- ^ "OVH.com lays the first brick of its future North American data centre in Beauharnois". CNW A PR Newswire Company. CNW Group Ltd. January 26, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ Group, Ankama (2015). "From Textile Factory to Studio: The Story of Our Premises". Ankama Group. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

In January of 2007, the deal was done and Ankama moved into 75 Boulevard d'Armentières in Roubaix.

- ^ BRGM (April 2002). "Inventaire d'anciens sites industriels sur l'arrondissement de Lille" [Inventory of old industrial sites on the arrondissement of Lille] (PDF). InfoTerre. Lezennes, F: BRGM. pp. 27–28.

- ^ Hutchinson, Lucille (November 28, 2016). "Chauffage urbain au bois à Roubaix" [Wood biomass district heating systems of Roubaix] (in French). Loos-en-Gohelle, F: Centre Ressource du Développement Durable.

- ^ Chatel, Laura; Ferran, Rosa (January 20, 2018). "The story of Roubaix Case study 8" (PDF). Zero Waste Europe. p. 3.

참고 문헌 목록

외부 링크

| 위키미디어 커먼즈에는 루바익스와 관련된 미디어가 있다. |

| 무료 사전인 Wiktionary에서 Rubaix를 찾아 보십시오. |