압가 레전드

Abgar Legend| 신약성서 아포크리파 |

|---|

|

| 사도파 아버지들 |

| 1 클레멘트 · 2 클레멘트 · 이그나티우스의 서간 · 폴리 카프 투 필리프 · 폴리카프의 순교 · 디다체 · 바나바스 · 디오그네투스 · 허마스의 목자 |

| 유대-기독교 복음서 |

| 에비오나이트 · 히브리인 · 나사레네스 |

| 유아 복음서 |

| 제임스 · 토마스. · 시리아어 · 사이비 매튜 · 목수 요셉의 역사 |

| Gnistic 복음서 |

| 유다 · 메리 · 필립 · 진실 · 시크릿 마크 · 사비오어 |

| 다른 복음서 |

| 토마스. · 마르시온 · 니코데무스 · 피터야. · 바나바스 |

| 묵시록. |

| 폴. · 피터야. · 사이비-메토디우스 · 토마스. · 스티븐 · 1 제임스 · 2 제임스 · 2 존 |

| 서간문 |

| 야고보의 아포크리폰 · 요한의 아포크리폰 · 아포톨로룸 · 사이비 티투스 · 피터 투 필립 · 폴과 세네카 |

| 연기한다 |

| 앤드루 · 바나바스 · 존 · 마마리 · 순교자들 · 폴. · 피터야. · 피터 앤드류 · 피터와 폴 · 베드로와 십이 · 필립 · 빌라도 · 타드데우스 · 토마스. · 티모시 · 크산티페, 폴리세나, 레베카 |

| Misc. |

| 디아테사론 · 아다이의 교리 · 필라테 사이클 · 바르톨로뮤의 질문 · 예수 그리스도의 부활 · 사도 바울의 기도 |

| "잃어버린" 책들 |

| 바르톨로뮤 · 마티아스 · 세린투스 · 바실리데스 · 마니 · 히브리인 · 라오디체인 |

| 나그 함마디 도서관 |

아브갈 전설은 나사렛의 예수와 오스로네의 아브갈 5세 우카마왕 사이에 주고받은 서신이라고 주장하는 일련의 편지들이다.[1][2][3][4] 이 문서는 4세기에 카이사리아의 에우세비우스가 에데사의 기록보관소에서 발견된 것으로 알려진 두 글자를 발표하면서 처음 모습을 드러냈다.[5][6] 그들은 예수의 생애 마지막 해 동안에 쓰여졌다고 주장한다.[7]

아브가 5세는 메소포타미아 상부의 시리아 도시 에데사에서 수도로 오스루엔의 왕이었다. 전설에 따르면 압가르 5세는 나병에 걸려 예수의 기적을 들은 적이 있다고 한다. 아브갈은 예수의 신성한 사명을 인정하면서 예수 그리스도에 자신의 병을 고쳐달라는 편지를 썼다. 이어 예수님을 박해로부터 안전한 피난처로 에데사로 피신하도록 초청했다. 전하는 대답에서 예수는 왕의 신앙에 박수를 보냈으나 거절했다. 그는 자신의 사명이 도시를 방문하지 못하게 한 것에 대해 유감을 표했다. 예수께서는 아브갈에게 복을 내려 주시고, 그가 하늘로 올라간 뒤에 제자들 가운데 한 사람이 에데사에 있는 왕과 신하의 모든 병을 고쳐 주겠다고 약속하셨다.[8]

이 편지들은 수세기 동안 많은 기독교 전통에서 심각하게 받아들여졌지만, 현대 기독교인들과 학자들에 의해 일반적으로 가성어로 분류된다.

압가르 전설의 전개

압가르 왕과 예수가 어떻게 대응했는가에 대한 이야기는 4세기에 카에사리아의 교회 역사학자 에우세비우스가 그의 교회 역사사(i.13과 III.1)에서 처음 재검증했고, 5세기 아다이의 시리아크 교리에 의해 시리아인 에프렘에 의해 정교하게 다시 팔렸다.[9]

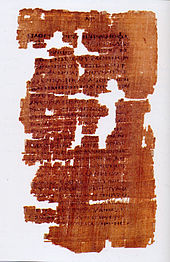

아브가 전설의 초기 버전은 에데사의 초기 기독교 문서인 아다이의 시리아크 독트린에 존재한다. 에피스툴라 압가리(Epistula Abgari)는 예수 그리스도와 에데사의 아브가 5세 사이에 주고받은 서신의 그리스어로 타드대우스 법전으로 알려져 있다.[10] 이 글자들은 4세기 초에 작곡되었을 것이다. 이 전설은 중세 시대에 시리아크에서 그리스어, 아르메니아어, 라틴어, 콥트어[11], 아랍어로 번역된 것으로 비교적 유명해졌다.[3][1][12]

기록 컨텍스트

에우세비우스는 에데사의 타드데우스에 대한 논의의 일환으로 그의 첫 번째 저서 '성전사'(Ca. 325 C.E.)에서 압가르 전설에 대한 가장 초기 알려진 이야기를 담고 있다. 에우세비우스는 타드데우스가 예수의 부활에 따라 사도 토마스의 요청으로 압가르에 갔다고 주장한다. 그는 또한 압가르와 예수의 서신을 제공한다고 주장하는데, 그가 시리아크에서 번역한 것이다.[13]

예수께 아브갈의 편지

교회 역사학자 에우세비우스는 에데사의 아브가와 예수가 주고받은 서신 사본을 에데산 문서 보관소에 보관하고 있다고 기록하고 있다.[14][15] 서신은 아브갈의 편지와 예수께서 명하신 대답으로 이루어져 있었다. 944년 8월 15일 성당. 콘스탄티노플에 있는 블라체네르의 메리는 편지와 만딜리온을 받았다. 그 후 두 유물 모두 파로스 성모 교회로 옮겨졌다.[16]

학자들은 아브갈이 통풍으로 고생했는지 나병이었는지, 서신이 양피지나 파피루스에 있었는지를 따지는 등 이 사건에서 기이한 성장이 일어났다.[17]

편지의 본문은 다음과 같았다.

에데사의 통치자 아브갈이 예루살렘 나라에 나타난 선한 내과의사 예수께 인사를 드린다. 나는 약이나 약초 없이 당신이 행한 것과 같은 당신의 치료법에 대한 보고를 들었다. 맹자를 보고 절름발이가 걷게 하고, 나병자를 정결하게 하고, 불순한 영혼과 악마를 내쫓고, 여전한 병으로 고통받는 자를 치료하고, 죽은 자를 기른다고 하기 때문이다. 그리고 너에 관한 이 모든 것을 들은 나는 두 가지 중 하나가 진실이어야 한다는 결론을 내렸다. 네가 하나님인지, 하늘에서 내려온 것인지, 아니면 이런 일을 하는 네가 하나님의 아들이라는 것이다. 그러므로 내가 너희에게 편지를 써서, 너희가 나에게 와서, 내가 앓는 모든 병을 고쳐 줄 수 있는지 물어 보라고 하였다. 나는 유대인들이 너희에게 중얼거리며 너희에게 해를 입힐 음모를 꾸미고 있다는 소식을 들었다. 하지만 나는 우리 둘 다에게 충분히 좋은 아주 작지만 고귀한 도시를 가지고 있다.[18]

예수께서 전령에게 아브갈로 돌아오라고 회답을 주셨다.

나를 보지 않고 성급하게 믿어 준 그대들은 복이 있나이다. 나를 본 자들이 나를 믿지 않을 것이며, 나를 보지 못한 자들이 나를 믿고 구원받을 것이라고 기록되어 있기 때문이다. 그러나 너희가 나에게 쓴 글과 관련하여, 내가 너희에게 가야 한다고 한 것과 관련하여, 내가 여기에서 보낸 모든 것을 내가 다 이루어야 한다. 내가 그것들을 다 이룬 다음에, 나를 보낸 그에게 다시 끌려가야 한다. 그러나 내가 사로잡힌 뒤에, 내가 나의 제자 가운데 한 사람을 너희에게 보내어, 그가 너희의 병을 고쳐 주시고, 너희와 너희에게 생명을 주시기를 빈다.[19]

에게리아는 에데사에서의 순례에 대한 자신의 설명에 그 편지를 썼다. 그녀는 머무르는 동안 그 편지를 읽었고, 에데사에 있는 복사본이 자기 집(프랑스일 가능성이 높은)의 복사본보다 더 꽉 찼다고 말했다.[20]

압가르 왕의 서신 왕위는 그것이 경지에 도달한 중요성 외에도 한동안 재판의 자리를 얻게 되었다. 시리아크 소송은 사순절 동안 압가르의 서신을 기념한다. 켈트족의 소송은 그것에 중요성을 부여한 것으로 보인다; 더블린 트리니티 칼리지 (E. 4, 2)에 보존된 자유 찬송가오룸은 아브갈에게 편지의 줄에 2개의 모음을 준다. 심지어 이 편지가 여러 가지 기도에 이어 일부 가톨릭 교회에서 작은 소송 사무소를 구성했을 가능성도 있다.[18]

이 사건은 여러 동양 교회의 자기 정의에 중요한 역할을 했다. 아브가는 동방 정교회에서 5월 11일과 10월 28일, 시리아 교회에서 8월 1일, 아르메니아 사도 교회 미사에서 매일 잔치를 벌이며 성인으로 집계된다.[citation needed]

비판장학금

많은 현대 학자들이 역사적 기록과는 별개로 아브가가 개종한 전통의 기원을 제시했다. S. K. 로스는 아브가의 이야기가 한 공동체의 기원을 신화나 신성한 조상으로 거슬러 올라가는 족보 신화의 장르에 있음을 암시한다.[21] F. C. 부르키트는 압가 8세 당시 에데사의 개종은 사도교 시대에 역행했다고 주장한다.[22] 윌리엄 아들러는 아브가 5세의 개종 이야기의 기원이 최근 기독교로 개종한 아브가 8세가 고용한 항쿼리학 연구원의 발명이 도시 역사에서 기독교를 안전하게 뿌리뽑기 위한 노력이었다고 제안한다.[23] 반면에 월터 바우어는 이 전설은 이단적 분열주의에 대항하여 집단의 응집력, 정통성, 사도세습을 강화하기 위해 출처 없이 쓰여졌다고 주장했다.[24] 그러나 서로 접촉하지 않은 것으로 알려진 몇몇 뚜렷한 출처가 기록물에서 그 편지들을 봤다고 주장했기 때문에 그의 주장은 의심스럽다.[25]

이 주제에 대한 장학금의 상당한 진전은 데스루모의 해설을 통한 번역 [27]M에 의해 이루어졌다[26]. 일러트의 전설에 대한 텍스트 증인들의 수집과 [28]브록,[29] 그리피스,[30] 미르코비치의 출처 이념에 대한 상세한 연구.[31] 현재 대다수의 학자들은 압가르의 개종과 관련한 문헌의 저자와 편집자의 목표가 시리아 에브라임의 정치적이고 교회적인 사상에 근거하여 교회와 국가 권력의 관계로서 에데사의 기독교화의 역사적 재건에 그다지 관심이 없었다고 주장한다.[32][33][31] 그러나 기록된 이야기들이 3세기 CE의 논란, 특히 바르다이산에 대한 대응으로 형성되었던 것 같지만,[34] 이야기의 기원은 아직 확실하지 않다.[32]

학자인 바트 D. 에르만은 3세기에 정통 기독교인들이 "반(反)마니차이안적 극성주의자"로 위조하고, 완전히 가짜인 것으로 한 드리버스 등의 증거를 인용하고 있다.[35]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ a b "Abgar legend Christian legend". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

Abgar legend, in early Christian times, a popular myth that Jesus had an exchange of letters with King Abgar V Ukkama of Osroene, whose capital was Edessa, a Mesopotamian city on the northern fringe of the Syrian plateau.

- ^ Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey; McKnight, Edgar V. (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

Abgar Legend, [ab'gahr] The Abgar legend concerns a supposed exchange of letters between King Abgar V of Edessa (9—46 c.e.) and Jesus, and the subsequent evangelization of Edessa by the apostle Thaddeus

- ^ a b Ross, Steven K. (2000-10-26). Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire, 114 - 242 C.E. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 9781134660636.

According to the legend a King Abgar (supposedly Abgar V Ukkama, Jesus' contemporary) wrote to Jesus in Jerusalem asking to be healed and inviting Jesus to visit Edessa. The text of that letter, and Jesus' reply, exist in many versions in almost all the languages of the Roman Empire, in keeping with the belief that the texts themselves had a sanctifying and protective power. The importance of this legend for the reputation of the city illustrates the central fact of the post-monarchical period: regardless of pre- Christian Edessa’s primary cultural orientation - whether it was to the East or to the West — the crucial factor in its later identity was its prominence as a center of Mesopotamian Christianity - the ‘First Christian Kingdom’ or the ‘Blessed City' - and it was this factor that preserved the name and status of Edessa through the Byzantine

- ^ Verheyden, Joseph (2015-08-13). The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Apocrypha. OUP Oxford. pp. 104–5. ISBN 9780191080173.

The Letters of Jesus and Abgar. In the canonical Gospels, Jesus is depicted writing nowhere except in the sand, in the story of the woman taken in adultery; and the status of that story, usually printed in modern bibles at John 7.53-8.11, is itself disputed. However, according to Eusebius and later authors, Jesus wrote to Abgar, King of Edessa, in response to a letter that Abgar had sent to him. Eusebius’s account is found in his Ecclesiastical History 1.13,2.1.6-8, where he presents both letters and explains how Edessa was converted to Christianity when Abgar was healed by the apostle Thaddaeus, whose journey to Edessa after Jesus’ resurrection fulfilled Jesus’ promise in his letter that he would send one of his disciples to Abgar. The legend also exists in other versions; in the Syriac Doctrina Addai (the Syriac equivalent for Thaddeus) the story is told without reference to any letter of Jesus to Abgar. Abgar’s letter to Jesus and Jesus’ letter to Abgar may be found in the standard editions and translations of Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, and also in standard collections of apocryphal texts in translation such as Schnecmelcher (Drijvers 1991) and Elliott (1999).

- ^ Lieu, Judith; North, John; Rajak, Tessa (2013-04-15). The Jews Among Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 9781135081881.

Eusebius tells us that he translated the correspondence from Syriac into Greek from a Syriac original from the royal archives at Edessa.

- ^ King, Daniel (2018-12-12). The Syriac World. Routledge. ISBN 9781317482116.

The existence of both local chronicles is probably due to the high reputation of the archives held at Edessa. These were made famous by the reference in Eusebius to his use of the archives to discover the Abgar Legend. Whether or not Eusebius's claims were true, they were credible and stimulated the deposition of further documents, which would constitute raw material for the writing of local history (Segal 1970: 20–1).

- ^ Petrosova, Anna (2005). The Armeniad: Visible Pages of History. Linguist Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 9785900227092.

Eusebius of Caesarea discovered two letters in the archive of Edessa, written during the last year of Jesus' life.

- ^ McGuckin, John Anthony (2010-12-15). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444392548.

- ^ Keith, Chris (2011-09-15). Jesus' Literacy: Scribal Culture and the Teacher from Galilee. A&C Black. p. 157. ISBN 9780567119728.

The Abgar Legend, in which Jesus sends a letter to King Abgar of Edessa, appears in Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History (ca. 325 C.E.) and is the center of the early fifth-century Syriac Doctrina Addai.

- ^ Stillwell, Richard (2017-03-14). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9781400886586.

Only one copy (in Greek) was found there of the legendary letter from Jesus to Abgar of Edessa.

- ^ Wilfong, Terry G.; SULLIVAN, KEVIN P. (2005). "The Reply of Jesus to King Abgar: A Coptic New Testament Apocryphon Reconsidered (P. Mich. Inv. 6213)". The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists. 42 (1/4): 107–123. ISSN 0003-1186. JSTOR 24519525.

- ^ Gottheil, R. J. H. (1891). "An Arabic Version of the Abgar-Legend". Hebraica. 7 (4): 268–277. doi:10.1086/369136. ISSN 0160-2810. JSTOR 527236.

- ^ Eusebius: 키르청게시히테(히스토리아 에르스테스 부흐, 13. 갑. Ein Bericht über den Herrscher der Edessener, Unifr.ch/bkv, 마지막 편집: 2008년 4월 4일.

- ^ Walsh, Michael J. (1986). The triumph of the meek: why early Christianity succeeded. Harper & Row. pp. 125. ISBN 9780060692544.

The story about this kingdom which Eusebius relates is as follows. King Abgar (who ruled from AD 13 to 50) was dying. Hearing of Jesus' miracles he sent for him. Jesus wrote back - this correspondence, Eusebius claims, can be found in the Edessan archives - to say that he could not come because he had been sent to the people of Israel, but he would send a disciple later. But Abgar was already blessed for having believed in him.

- ^ 그의 교회 역사에서, 나, 시이, CA AD 325.

- ^ Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie ecclésiastique de l'Empire byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines. p. 172.

- ^ Norris, Steven Donald (2016-01-11). Unraveling the Family History of Jesus: A History of the Extended Family of Jesus from 100 Bc Through Ad 100 and the Influence They Had on Him, on the Formation of Christianity, and on the History of Judea. WestBow Press. ISBN 9781512720495.

- ^ a b Leclercq, Henri (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Church History, Book I (Eusebius)".

- ^ Bernard, John. "The Pilgrimage of Egeria". University of Pennsylvania. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- ^ 로스, 로만 에데사 2001년 런던 루트리지 동부 프린지 지역의 정치와 문화, 페이지 135

- ^ 버킷, F.C., 초동 기독교, 존 머레이, 1904년 런던, 친구. i

- ^ Adler, William (2011). "Christians and the Public Archive". In Mason, E.F. (ed.). A Teacher for All Generations: Essays in Honor of James C. VanderKam. Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism. Brill. p. 937. ISBN 978-90-04-22408-7. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ 바우어 1971 1장

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: History of Armenia (Moses of Chorene)".

- ^ 캄플라니 2009, 페이지 253.

- ^ Histoire du Roy Abgar et de Jésus, Présentation et traduation du texte diriaque intégral de la Dutrataï par. A. 데스루모, 브레폴스, 1993년 파리.

- ^ M. 일러트(에드), 교조리나 아다이. 에데세나 / 디 아브갈레겐데를 상상해보라. Das Christusbild von Edessa (Fontes Christiani, 45), Brepols, Turhout 2007

- ^ S.P. 브록, 에우세비우스와 시리아크 기독교, H.W. 아트리지-G. 하타(eds), 에우세비우스, 기독교, 유대교, 브릴, 레이든-뉴욕-쾰른 1992, 페이지 212-234, S.브록에서 다시 출판, 에프렘에서 로마노스로. 후기 고대에서 Syriac과 그리스어의 상호작용(Variorum Collected Studies Series, CS644), Ashgate/Variorum, Aldershot-Brookfield-Singapore-Sydney 1999, n. II.

- ^ Griffith, Sidney H. (2003). "The Doctrina Addai as a Paradigm of Christian Thought in Edessa in the Fifth Century". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 6 (2): 269–292. doi:10.31826/hug-2010-060111. ISSN 1097-3702. S2CID 212688514. Archived from the original on 21 August 2003. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint : bot : 원본 URL 상태 미상(링크) - ^ a b 미르코비치 2004.

- ^ a b 캄플라니 2009.

- ^ 그리피스 2003, §3 및 §28.

- ^ Mirkovic 2004, 페이지 2-4.

- ^ 위조 및 위조, pp455-458

원천

| Wikisource는 이 기사와 관련된 원본 텍스트를 가지고 있다: |

- Bauer, Walter (1971). Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000. Retrieved 25 January 2017. (1934년 출판된 독일어 원본)

- Camplani, Alberto (2009). "Traditions of Christian foundation in Edessa: Between myth and history" (PDF). Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni (SMSR). 75 (1): 251–278. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Chapman, Henry Palmer (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Eisenman, Robert (1992), "The sociology of MMT and the conversions of King Agbarus and Queen Helen of Adiabene" (PDF), Paper presented at SBL conference, retrieved 21 March 2017

- Eisenman, Robert (1997). "Judas the brother of James and the conversion of King Agbar". James the Brother of Jesus.

- Holweck, F. G. (1924). A biographical dictionary of the saints. St. Louis, MO: B. Herder Book Co.

- Mirkovic, Alexander (2004). Prelude to Constantine: The Abgar tradition in early Christianity. Arbeiten zur Religion und Geschichte des Urchristentums. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- von Tischendorf, Constantin. "Acta Thaddei (Acts of Thaddeus)". Acta apostolorum apocr. p. 261ff.

- Wilson, Ian (1991). Holy faces, secret places.

외부 링크

- 안테-니세 아버지들, vol. 8: 열둘 중 하나인 성 사도 타드데우스의 행위

- 에우세비우스에서 에데사 왕 압가루스에게 예수 그리스도의 서간

- 에데사 왕 아브가루스 오우차마와 나사렛 예수의 교신(J.로버, 1842년)

- 에우세비우스의 관련 구절과 아다이의 교리를 포함한 아브가르 개조에 관한 고대 문서의 영문 번역은 에서 구할 수 있다.