노르웨인

Norsemen| 다음 시리즈의 일부 |

| 노르웨인 |

|---|

|

| 위키프로젝트 노르웨이의 역사와 문화 |

노르웨이어족(또는 노르웨이어족)은 중세 초기의 북게르만 민족언어주의 집단으로, 그 기간 동안 구 노르웨이어를 구사하였다.[1][2][3][4]이 언어는 인도유럽어족의 북게르만어 분기에 속하며, 스칸디나비아의 현대 게르만어족의 전신이다.[4]8세기 후반에 스칸디나비아인들은 모든 방면에서 대규모 확장에 나서 바이킹 시대를 열었다.19세기 이후 영어 장학금에서는 노르웨이의 바다낚시 상인, 정착민, 전사들이 흔히 바이킹이라고 불려왔다.앵글로색슨 잉글랜드의 역사가들은 주로 영국의 북쪽과 북서쪽 섬을 침략해 점령한 노르웨이의 노르웨이어 바이킹(노르세멘)과 주로 영국 동부를 침략해 점령한 덴마크 바이킹(Dennish Vikings)을 구분한다.[a]

현대 후손인 덴마크인,[5] 아이슬란드인,[b] 패로 아일랜드인,[b] 노르웨이인, 스웨덴인에서 파생된 노르웨이의 정체성은 현재 노르웨인보다는 일반적으로 '스칸디나비아인'으로 통칭되고 있다.[6][7]

노르웨이어와 노스맨의 역사

노르웨인이라는 단어는 19세기 초 영어에서 처음으로 나타난다. 옥스퍼드 영어 사전 제3판에 제시된 가장 초기 증명은 월터 스콧의 1817년 '해롤드 더 던트리스'에서 비롯되었다.이 단어는 '노르웨이어'라는 의미와 함께 16세기 동안 네덜란드어로부터 영어로 차용된 '노르웨이어'라는 형용사를 사용하여 만들어졌으며, 스콧이 '고대 또는 중세의 스칸디나비아 또는 그 언어에 대한 또는 관련'이라는 의미를 갖게 되었다.[8]그러므로 현대적으로 바이킹이라는 단어를 사용하는 것과 마찬가지로, 노르웨인이라는 단어는 중세 용어에 특별한 근거가 없다.[9]

노르드만이라는 용어는 중세 시대에 만난 민족들이 노르드어를 쓰는 사람들에게 적용시킨 '노스만'이라는 뜻의 반향어를 말한다.[10]올드 프랑크어 단어 노르트만("Northmann")은 노르만누스로 라틴어화되어 라틴어 본문에 널리 사용되었다.그 후 라틴어 노마누스는 올드프랑스어를 노르망드로 입력하였다.이 말에서 노르만족과 노르망디의 이름이 나왔으며, 10세기에 노르망디인들이 정착하였다.[11][12]

같은 단어가 라틴어의 히스패닉 언어와 지역적 품종에서 n-뿐만 아니라 l-에서 시작하는 형태와 함께 l-로망니(현지의 로망스 언어에서 코감기를 반영하는 것임)로 입력되었다.[13]이 형태는 차례로 아랍어로 차용되었을지도 모른다: 아랍의 저명한 초기 출처인 알 마수드는 세비야에서 844명의 침입자를 루스뿐만 아니라 알-로드하나로 확인했다.[14]

올드 영어로 쓰여진 앵글로색슨 크로니클은 더블린의 이교도 노르웨이인 노르웨이어인(노르메인)과 다넬로의 기독교인 데인(데네)을 구분한다.942년, 요크의 노르스 왕에 대한 에드먼드 1세의 승리를 기록한다: "단일인들은 이전에 노르스만족의 지배하에 무력에 의해 오랫동안 이교도에게 사로잡혀 있었다."[15][16][17]

기타 이름

현대 장학금에서 바이킹은 특히 영국령 섬에서 노르웨이의 습격과 수도적 약탈과 관련하여 노르웨인을 공격하는 일반적인 용어지만, 당시에는 이런 의미로 사용되지 않았다.올드 노르웨이나 올드 영어에서 이 단어는 단순히 '해적'[18][19][20]을 의미했다.

노르웨이는 독일인들에 의해 아스코만니, 아스모만, 가엘족에 의해 로클라나흐(노르스), 앵글로색슨족에 의해 데네(댄스) 등으로도 알려져 있었다.[21]

게일어 용어인 핀갈(노르웨이어 바이킹 또는 노르웨이어), 더블갈(다니쉬 바이킹 또는 덴마크어), 갈 고이델(외국 게일어)은 게일어 문화에 동화된 아일랜드와 스코틀랜드의 노르웨이의 사람들을 위해 사용되었다.[22]더블라이너들은 그들을 오스만족, 즉 동족이라고 불렀고 옥스맨스타운이라는 이름은 그들의 거주지 중 하나에서 유래했다. 그들은 또한 Lochlannaigh 또는 Lake-feople이라고도 알려져 있다.

슬라브인, 아랍인, 비잔틴인들은 그들을 러스인 또는 로스인(Rohs)으로 알고 있었는데, 아마도 로스의 다양한 용법, 즉 "조정과 관계"에서 유래했거나, 동 슬라브인 땅을 방문한 대부분의 북부인들이 발원한 스웨덴 중부의 로슬라겐 지역에서 유래되었을 것이다.[23]

오늘날의 고고학자들과 역사가들은 동슬라브 땅에 있는 이러한 스칸디나비아 정착촌들이 러시아와 벨라루스 국가들의 이름을 형성했다고 믿는다.

슬라브족과 비잔틴족도 이들을 바랑어족(노르드:비잔틴 황제들의 스칸디나비아 경호원들은 바랑가르 근위대로 알려졌다.[24]

현대 스칸디나비아어에는 노르웨인(스웨디어: nordborna, 덴마크어: nordboerne, 노르웨이어: nordboerne, 또는 확정복수의 nordboane)이라는 단어는 북유럽 국가에 살고 있는 고대인과 현대인 모두에게 사용되며 북 게르만어 중 하나를 말한다.

현대 스칸디나비아어에서는 Northman(노르웨이어어:노르드만;[25] 스웨덴어: 노르만어:[26] 노르만어; 덴마크어: 노르드만어 )는 원래 노르딕 지역 전체의 사람들을 일컫는 용어였지만, 지금은 노르웨이 국적의 사람들을 가리키는 말로 자주 쓰인다.

지리

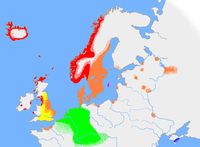

바이킹의 기원에 대한 영국의 개념은 부정확했다.영국을 약탈한 사람들은 오늘날 덴마크, 스캐니아, 스웨덴과 노르웨이의 서부 해안(최대 70도선)과 스웨덴 발트 해안을 따라 위도 60도 안팎까지, 맬라렌 호수까지 살았다.그들은 또한 스웨덴의 고틀란드 섬에서 왔다.노르만족과 남부 게르만족의 국경인 데네비르케족은 오늘날 덴마크-독일 국경에서 남쪽으로 약 50km(31mi) 떨어져 있다.최남단에 살고 있는 바이킹들은 타이네를 타고 뉴캐슬보다 더 북쪽에 살지 않았고, 북쪽에서보다 동쪽에서 영국으로 더 많이 여행했다.

스칸디나비아 반도의 북부는 (노르웨이 해안을 제외하고) 노르웨이에 의해 거의 인구가 밀집되지 않은 상태였는데, 이 생태계는 스웨덴 북부의 원주민인 사미족과 오늘날의 러시아에서는 노르웨이, 핀란드, 콜라 반도의 넓은 지역이 거주하고 있었기 때문이다.[citation needed]

노르웨이의 스칸디나비아인들은 현재 영국(잉글랜드, 스코틀랜드, 웨일스), 아일랜드, 아이슬란드, 러시아, 벨라루스, 프랑스, 시칠리아, 벨기에, 우크라이나, 핀란드, 에스토니아, 라트비아, 리투아니아, 독일, 폴란드, 그린란드, 캐나다,[28] 파로섬에 정치와 정착촌을 세웠다.

주목할 만한 노르웨이의 사람들

- Aud the Deep-Minded c.(9세기 CE), 선장 겸 아이슬란드의 초기 정착자

- 덴마크와 노르웨이의 왕 하랄드 블루투스(Deed 985/86 CE)는 블루투스 무선 기술의 대명사다.

- 볼리 볼라손(CE 1000년 출생)은 아이슬란드의 저명한 전사였으며 바랑가르드 근위대 소속이다.

- 프리디스 에익스도티르(CE 970년 출생), 빈랜드의 탐험가 및 초기 식민지 개척자

- 그린란드 최초의 정착지 창시자 노르웨이의 탐험가 에릭 더 레드(c.950 - 1003 CE)

- 라이프 에릭슨 (970년 - 1020년 CE),c. 아이슬란드 탐험가는 유럽 최초로 북아메리카 대륙에 발을 내디딘 것으로 생각되었다.

- 에스트리드 c.(11세기 CE), 스웨덴의 강력한 거물이자 모계인

- 하랄드 페어헤어(c.CE 850년 - 932년)는 노르웨이의 초대 왕이다.

- Helsingland Rune Medit 21을 담당하는 스웨덴의 Runemaster Gunnborga (11세기 CE)c.

- 힐드르 흐롤프스도티르(c.CE 9세기)는 트론하임의 바이킹 항아리인 아버지 롤프 네비아의 추방과 관련된 시로 유명한 노르웨이 스칼드.

- Olaf the White c.(820년 - 9세기 후반 CE), Viking sea-king, Dublin 왕, Aud the Deep-Minded의 남편

- 전설적인 바이킹 영웅이자 왕인 라그나 로드브록(c.CE 9세기)

- 노르드 식민지 그린란드의 유명한 시녀인 조르브예르그 리틸벨바(CE 10세기)c.

- Gunnlaugr ormstunga c.(983년 - 1008년 CE), 아이슬란드, 노르웨이, 아일랜드, 오크니, 스웨덴에서 널리 활동한 아이슬란드 스키드

- 강자 라우드(c.CE 10세기 후반), 노르웨이의 블롯 사제 및 바다낚시 용사

- 슈타윤 레프도티르(CE 10세기)는 기독교 선교사 장브란드르를 조롱하는 시구로 유명한 아이슬란드 스칼드.c.

- 전설적인 노르웨이의 해적선단 지도자 "붉은 여인"이라는 이름인 루슬라 c.(5-11세기 CE)

- 스타인보르 쉬마츠도티르(-1271 CE), 영향력 있는 아이슬란드 모계 및 스칼드

- 에길 스칼라그리움손(c.904년 - 995년), 아이슬란드 전쟁 시인, 마법사, 배서커, 농부, 에길 사가의 반영웅

- 노르웨이의 신화의 주요 근원을 이루는 아이슬란드 역사학자, 시인, 정치인, 알싱의 법률가, 스노리 스터루슨(1179년 - 1241년)

- 키가 큰 토르켈(c.CE 11세기 초), 반레전드적인 스캐니안 영주, 짐스비킹

- 브르발라 전투에서의 역할로 유명한 전설적인 방패녀 베보르(-750)

참고 항목

| 위키미디어 커먼즈에는 노르웨이의 역사와 문화와 관련된 미디어가 있다. |

메모들

- ^ For example: "Most of the earliest Viking settlers in Ireland were Norsemen, but c.850 a large Danish Host arrived" (Peter Hunter Blair, An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed., 2003, pp. 66-67); "In 875 Danes and Norsemen were competing" for control of Scotland (Peter Sawyer, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, 1997, p. 90); Frank 스텐톤은 '요크의 덴마크 왕국'과 '요크의 노르스 왕국'을 구분하며, 10세기 중엽에 "현대 작가들에게 종종 무시당하지만 이 시기의 전체 역사의 밑바탕이 되는 데네스와 노르스멘의 대립"을 가리킨다.(Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed., 1971, pp. 359, 765); Barbara Yorke comments that the Chronicle tends to use the term "Danish" for all Scandinavian forces, but the attackers on Portland in the late eighth century seem to have been "predominantly Norse adventurers, but some way from there normal raiding grounds in Britain" (Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995. p. 108); in 793: "The hit-and-run raid on Lindisfarne was probably the work of Norse rather than Danish warriors, straying from their accustomed haunts in the Faroes and Orkney down the North Sea coast of Britain in search of easy loot" (N. J. Higham, The Kingdom of Northumberland AD 350-1100, 1993, p. 173).

- ^ a b 편의상 "스칸디나비아인"은 오늘날 아이슬란드인과 패로섬 사람들이 스칸디나비아에 거주하지 않지만 "북 게르만족"의 동의어로 흔히 사용된다.그러므로 이 용어는 지리적 의미보다는 문화적 의미를 부여한 것이다.

참조

- ^ Fee, Christopher R. (2011). Mythology in the Middle Ages: Heroic Tales of Monsters, Magic, and Might: Heroic Tales of Monsters, Magic, and Might. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0313027253.

"Viking" is a term used to describe a certain class of marauding Scandinavian warrior from the 8th through the 11th century. However, when discussing the entire culture of the Northern Germanic peoples of the early Middle Ages, and especially in terms of the languages and literatures of these peoples, it would be more accurate to use the term "Norse." Therefore during the Middle Ages and beyond, it therefore might be useful to speak of "German" peoples in middle Europe and of "Norse" peoples in Scandinavia and the North Atlantic.

- ^ McTurk, Rory (2008). A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 7. ISBN 978-1405137386.

Old Norse' defines the culture of Norway and Iceland during the Middle Ages. It is a somewhat illogical concept as it is largely synonymous with 'Norse'... The term 'Norse' is often used as a translation of norroenn. As such it applies to all the Germanic peoples of Scandinavia and their colonies in the British Isles and the North Atlantic.

- ^ DeAngelo, Jeremy (2010). "The North and the Depiction of the "Finnar" in the Icelandic Sagas". Scandinavian Studies. 82 (3): 257–286. JSTOR 25769033.

The term "Norse" will be used as a catchall term for all North Germanic peoples in the sagas...

- ^ a b Leeming, David A. (2014). The Handy Mythology Answer Book. Visible Ink Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1578595211.

"Who were the Norse people? The term Norse is commonly applied to pre-Christian Northern Germanic peoples living in Scandinavia during the so-called Viking Age. Old Norse gradually developed into the North Germanic languages, including Icelandic, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish.

- ^ Kristinsson, Axel (2010). Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe Since the Bronze Age. ReykjavíkurAkademían. ISBN 978-9979992219.

The same can be said of Viking Age Scandinavians who did not have a common ethnonym but expressed their common identity through the geographical and linguistic terms... There is absolutely no doubt about a common Northern identity during the Viking Age and afterwards... it even survives today.

- ^ Kennedy, Arthur Garfield (1963). "The Indo-European Language Family". In Lee, Donald Woodward (ed.). English Language Reader: Introductory Essays and Exercises. Dodd, Mead.

[T]he pages of history have been filled with accounts of various Germanic peoples that made excursions in search of better homes; the Goths went into the Danube valley and thence into Italy and southern France ; and thence into Italy and southern France; the Franks seized what was later called France; the Vandals went down into Spain, and via Africa they "vandalized" Rome; the Angles, part of the Saxons, and the Jutes moved over into England; and the Burgundians and the Lombards worked south into France and Italy. Probably very early during these centuries of migration the three outstanding groups of the Germanic peoples—the North Germanic people of Scandinavia, the East Germanic branch, comprising the Goths chiefly, and the West Germanic group, comprising the remaining Germanic tribes—developed their notable group traits. Then, while the East Germanic tribes (that is, the Goths) passed gradually out of the pages of history and disappeared completely, the North Germanic, or Scandinavian, or Norse, peoples, as they are variously called, became a distinctive people, more and more unlike the West Germanic folk who inhabited Germany itself and, ultimately, Holland, and Belgium and England. While that great migration of nations which the Germans have named the Volkerwanderung was going on, the Scandinavian division of the Germanic peoples had kept their habitation well to the north of the others and had been splitting up into the four subdivisions now known as the Swedes, Norwegians, Danes, and Icelanders. Long after the West Germanic and East Germanic peoples had made history farther south in Europe, the North Germanic tribes of Scandinavia began a series of expeditions which, during the eighth and ninth centuries, in the so-called Viking Age especially, led them to settle Iceland, to overrun England and even annex it to Denmark temporarily, and, most important of all, to settle in northern France and merge with the French to such an extent that Northmen became Normans, and later these Normans became the conquerors of England.

- ^ Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198030737.

Ottar belonged to a group of peoples who were beginning to have a huge impact on European history. They are now called 'Scandinavians', though historically they were called 'Northmen'.

- ^ "Norseman, n.", "Norse, n. and adj." OED Online, Oxford University Press, 2018년 7월, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/128316,.2018년 9월 10일에 접속.

- ^ "바이킹, n." OED Online, 옥스퍼드 대학 출판부, 2018년 7월, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/223373[dead link].2018년 9월 10일에 접속.

- ^ "Northman, n." OED Online, 옥스퍼드 대학 출판부, 2018년 7월, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/128371.2018년 9월 10일에 접속.

- ^ Michael Lerche Nielsen, Review of Rune Palm, Viknarnas spr 750k, 750–1100, Historyisk Tidskrift 126.3 (2006) 584–86 (pdf 페이지 10–11) (스웨덴어)

- ^ Louis John Paetow, Berkeley의 학생, 교사, 도서관을 위한 중세 역사 연구의 가이드:1917년 캘리포니아 대학교, OCLC 185267056, 페이지 150, 레오폴드 델리슬, 리테라테라틴 등 히스토이어 뒤 모엔 ge, 파리: 레루, 1890, OCLC 490034651, 페이지 17을 인용했다.

- ^ 앤 크리스티스, 남부의 바이킹스(런던:Bloomsbury, 2015), 페이지 15-17.

- ^ 앤 크리스티스, 남부의 바이킹스(런던:Bloomsbury, 2015), 페이지 23-24.

- ^ Williams, Ann (2004). "Edmund I (920/21–946)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8501. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (구독 또는 영국 공공도서관 회원 필요)

- ^ Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1979). "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". English Historical Documents, Volume 1, c. 500-1042 (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-415-14366-0.

- ^ Bately, Janet, ed. (1986). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, A Collaborative Edition, 3, MS A. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-85991-103-0.

- ^ "Viking, n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Cleasby, Richard; Vigfusson, Gudbrand (1957). "víkingr". An Icelandic–English Dictionary (2nd edition by William A. Craigie ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bosworth, Joseph; Northcote Toller, T. (1898). "wícing". An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Richards, Julian D. (2005). Vikings : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0191517396. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Baldour, John Alexander; Mackenzie, William Mackay (1910). The Book of Arran. Arran society of Glasgow. p. 11.

- ^ 툰베르크, 칼 L.(2011년).세르클랜드 오치 데 켈 소재.괴테보르그스 우주선CLTS. 페이지 20-22.ISBN 978-91-981859-3-5.

- ^ 스베리르 야콥손, 바랑가: 신의 성화(Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)에서.ISBN 978-3-030-53797-5[pages needed]

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka Nynorskordboka".

- ^ "Norrman svenska.se".

- ^ "Nordmand — den Danske Ordbog".

- ^ Linden, Eugene (December 2004). "The Vikings: A Memorable Visit to America". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.