하버드 대학교

Harvard University | |

| 라틴어: Universitas Harvardiana | |

이전 이름 | 하버드 칼리지 |

|---|---|

| 좌우명 | 베리타스 (라틴어)[1] |

영어로 된 모토 | "진실" |

| 유형 | 사적인 연구 대학 |

| 설립된 | 1636; 전 ([2] |

| 창시자 | 매사추세츠 일반 법원 |

| 인증 | 네체 |

학연 | |

| 기부금 | 507억 달러(2023) |

| 대통령 | 앨런 가버(중간) |

| 프로보스트 | 앨런 가버 |

학무원 | 약 2,400명의 교직원(및 10,400명 이상의 부속교직병원 학사임용)[5] |

| 학생들 | 21,613 (2022년 가을)[6] |

| 학부생 | 7,240 (2022년 가을)[6] |

| 대학원생 | 14,373 (2022년 가을)[6] |

| 위치 | , , 미국 42°22'28 ″N 71°07'01 ″W / 42.37444°N 71.11694°W |

| 캠퍼스 | 중형 도시[7], 209 에이커 (85 ha) |

| 신문 | 하버드 크림슨 |

| 색 | 크림슨, 화이트, 블랙[8] |

| 애칭 | 크림슨 |

스포츠 계열사 | |

| 마스코트 | 존 하버드 |

| 웹사이트 | harvard |

| |

하버드 대학교는 매사추세츠주 케임브리지에 있는 사립 아이비리그 연구 대학입니다. 1636년에 하버드 대학으로 설립되었고 첫 번째 후원자인 청교도 성직자 존 하버드의 이름을 따서 명명된 이 대학은 미국에서 가장 오래된 고등 교육 기관입니다. 그 영향력, 부, 순위는 이 대학을 세계에서 가장 일류 대학 중 하나로 만들었습니다.[9]

하버드의 설립은 매사추세츠 식민지 의회의 승인을 받은 것으로, 공식적으로 어떤 교단에도 소속된 적은 없지만, 초창기 하버드 대학은 주로 회중 성직자들을 양성했습니다. 그것의 교육과정과 학생 단체는 18세기 동안 점차적으로 세속화되었습니다. 19세기에 이르러 하버드는 보스턴 엘리트들 사이에서 가장 두드러진 학문적, 문화적 기관으로 부상했습니다.[10][11] 미국 남북전쟁 이후 찰스 윌리엄 엘리엇(Charles William Eliot) 대통령의 오랜 재임 기간(1869–1909) 아래, 이 대학은 여러 부속 전문학교를 개발하여 이 대학을 현대 연구 대학으로 변화시켰습니다. 1900년, 하버드는 미국 대학 협회를 공동 설립했습니다.[12] 제임스 B. Conant는 대공황과 제2차 세계대전을 겪으며 대학을 이끌었고, 전쟁 후 입학을 자유화했습니다.

이 대학은 10개의 학부와 하버드 래드클리프 연구소로 구성되어 있습니다. 예술과 과학 학부는 학부와 대학원의 다양한 학문 분야에 대한 연구를 제공하며, 다른 학부들은 전문 학위를 포함한 대학원 학위만을 제공합니다. 하버드에는 세 개의 주요 캠퍼스가 있습니다:[13] 하버드 야드를 중심으로 한 209 에이커(85 ha)의 캠브리지 캠퍼스; 보스턴 올스턴 인근의 찰스 강 바로 건너편에 인접한 캠퍼스; 보스턴의 롱우드 메디컬 지역에 있는 메디컬 캠퍼스.[14] 하버드의 기부금은 507억 달러로 평가되며, 세계에서 가장 부유한 학술 기관입니다.[3][4] 기부금 수입은 학부 대학이 재정적 필요에 관계없이 학생들을 입학시키고 대출 없이 재정적 지원을 제공할 수 있게 해줍니다. 미국 도서관 협회에 의하면, 하버드 대학교는 미국에서 네 번째로 큰 도서관을 가지고 있다고 합니다.

하버드 동문, 교수진 및 연구원들은 188명의 살아있는 억만장자, 8명의 미국 대통령, 수많은 국가 원수, 주목할 만한 회사의 설립자, 노벨상 수상자, 필즈 메달리스트, 의회 의원, 맥아더 펠로우, 로즈 장학생, 마샬 장학생, 튜링상 수상자, 퓰리처상 수상자, 그리고 Fullbright Scholars; 대부분의 지표에 따르면 하버드는 이 각 부문에서 세계 최고의 순위를 차지하고 있습니다.[Notes 1] 게다가, 학생들과 졸업생들은 10개의 아카데미 상과 110개의 올림픽 메달(46개의 금메달)을 수상했습니다.

역사

식민지 시대

하버드는 1636년에 매사추세츠 만 식민지의 거대하고 일반적인 법원의 투표로 독립 이전의 식민지 시대에 설립되었습니다. 첫 교장인 Nathaniel Eaton은 이듬해 취임했습니다. 1638년, 이 대학은 영국령 북미 최초의 인쇄기를 인수했습니다.[16][17]

1639년, 그것은 매사추세츠로 이민 간 후 곧 사망한 영국 성직자 존 하버드의 이름을 따서 하버드 대학으로 명명되었고, 그의 도서관은 약 320권에 달했습니다.[18] 하버드 법인을 설립하는 헌장은 1650년에 승인되었습니다.

1643년 출판된 이 대학의 목적은 다음과 같습니다. "우리의 현 목사들이 먼지 속에 누워있을 때 문맹인 사역을 교회에 맡기는 것을 두려워하며 학문을 발전시키고 그것을 후세에 영속시키기 위해."[19] 대학은 초기에 많은[20] 청교도 목사들을 양성했고, 식민지의 많은 지도자들이 캠브리지 대학에 다녔던 영국 대학 모델에 기반한 고전적인 커리큘럼을 제공했습니다. 하버드는 어떤 특정 교파에도 소속되어 있지 않습니다.[21]

라이즈 매더는 1681년부터 1701년까지 하버드 대학의 총장을 역임했습니다. 1708년 존 르베렛은 성직자가 아니었던 첫 번째 대통령이 되었습니다.[22]

19세기

19세기에는 회중의 목사들 사이에 이성과 자유의지에 대한 계몽주의 사상이 널리 퍼져서, 그 목사들과 그들의 회중은 더 전통적이고 칼뱅주의적인 정당들과 대립하게 되었습니다.[23]: 1–4 1803년 홀리스신학 교수 데이비드 타판이 세상을 떠나고 1년 뒤 조셉 윌러드 대통령이 세상을 떠나자 이들의 후임을 놓고 다툼이 벌어졌습니다. 헨리 웨어는 1805년 홀리스 의장으로 선출되었고, 자유주의자 새뮤얼 웨버는 2년 후 대통령으로 임명되어 하버드의 전통적인 사상에서 자유주의적인 아르미니안 사상으로의 전환을 예고했습니다.[23]: 4–5 [24]: 24

1869년부터 1909년까지 하버드 총장이었던 찰스 윌리엄 엘리엇은 기독교가 선호하는 위치를 교육과정에서 줄이면서도 학생들의 자기 지도에 개방했습니다. 엘리어트는 미국 고등교육의 세속화에 영향을 미친 인물이었지만, 세속주의보다는 윌리엄 엘러리 채닝, 랄프 월도 에머슨 등 당대의 초월주의적 유니테리언적 신념에 더 많은 동기를 부여받았습니다.[25]

1816년, 하버드는 프랑스어와 스페인어 연구에 새로운 프로그램을 시작했고, 조지 티크너는 이 언어 프로그램의 첫 교수였습니다.

20세기

하버드의 대학원들은 19세기 후반부터 소수의 여성들을 입학시키기 시작했습니다. 제2차 세계 대전 동안, 래드클리프 대학(1879년 설립 이래로, 여성을 위해 강의를 반복하기 위해 하버드 교수들에게 돈을 지불해온)의 학생들은 남성들과 함께 하버드 수업에 참석하기 시작했습니다.[27] 1945년, 여성들은 처음으로 의과대학에 입학했습니다.[28] 1971년부터 하버드 대학교는 래드클리프 여성들을 위한 학부 입학, 교육, 주거의 모든 측면을 통제해 왔으며, 1999년 래드클리프는 하버드 대학교에 공식적으로 합병되었습니다.[29]

20세기에 하버드의 기부금이 급증하고 저명한 지식인과 대학 부속 교수들이 등장하면서 하버드의 명성이 높아졌습니다. 대학의 급속한 등록 증가는 또한 새로운 대학원 학술 프로그램의 설립과 학부 대학의 확장의 산물이기도 했습니다. 래드클리프 대학은 하버드 대학의 여성 상대로 부상하여 미국에서 가장 중요한 여성 학교 중 하나가 되었습니다. 1900년에 하버드는 미국 대학 협회의 창립 멤버가 되었습니다.[12]

사회학자이자 저자인 제롬 카라벨(Jerome Karabel)에 따르면, 20세기 첫 수십 년 동안의 학생 단체는 주로 "오래된 주식, 높은 지위의 개신교인, 특히 성공회 신자, 회중교회 신자, 장로교 신자"였다고 합니다.[30] 하버드 대학의 유대인 학생 비율이 20%에 이른 지 1년 후인 1923년 A 총장. 로렌스 로웰(Lawrence Lowell)은 유대인 학생의 입학을 학부생의 15%로 제한하는 정책 변화를 지지했습니다. 하지만 로웰의 아이디어는 거절당했습니다. 로웰은 또한 대학 신입생 기숙사에서 강제로 인종 차별을 없애는 것을 거부했습니다. "우리는 유색인종에게 우리가 백인에게 하는 것과 같은 교육의 기회를 빚지고 있지만, 그와 백인을 서로에게 맞지 않거나, 아닐 수도 있는 사회적 관계로 강제하는 것은 그에게 빚지지 않습니다."[31][32][33][34]라고 썼습니다.

제임스 B 대통령. Conant는 1933년부터 1953년까지 대학을 이끌었습니다. Conant는 창의적인 학문을 활성화하여 국내와 세계의 신흥 연구 기관들 사이에서 하버드의 명성을 보장하기 위한 노력을 하였습니다. Conant는 고등교육을 부유한 사람들을 위한 자격이라기보다는 재능 있는 사람들을 위한 기회의 매개체로 여겼습니다. 이처럼 그는 재능 있는 청소년을 발굴하고 모집하며 지원하기 위한 프로그램을 고안했습니다. 1945년 코난트의 지도 아래 하버드 교수진이 발표한 영향력 있는 268쪽 분량의 보고서인 '자유사회의 일반교육(General Education in a Free Society)'은 커리큘럼 연구에서 가장 중요한 작업 중 하나로 남아 있습니다.[35]

1945년과 1960년 사이에, 대학을 더 다양한 학생들에게 개방하기 위해 입학 표준화가 이루어졌습니다; 예를 들어, 2차 세계 대전 이후, 퇴역 군인들이 입학을 고려할 수 있도록 특별 시험이 개발되었습니다.[36] 더 이상 선택된 뉴잉글랜드 예비 학교에서 그림을 그리지 않고, 학부 대학은 공립 학교의 노력하는 중산층 학생들에게 접근할 수 있게 되었습니다. 더 많은 유대인들과 가톨릭 신자들이 입학했지만, 여전히 흑인, 히스패닉, 또는 아시아인들은 일반 인구에서 이 집단들을 대표하는 사람들보다 적습니다.[37] 20세기 후반 내내 하버드는 점차 다양해졌습니다.[38]

21세기

하버드 래드클리프 연구소의 학장이었던 드류 길핀 파우스트는 2007년 7월 1일 하버드 최초의 여성 총장이 되었습니다.[39] 2018년 파우스트는 은퇴하고 골드만 삭스 이사회에 합류했습니다. 2018년 7월 1일, 로렌스 바코우는 하버드의 29대 총장으로 임명되었습니다.[40] 바코우는 2023년에 은퇴했습니다.

2023년 2월, 약 6,000명의 하버드 노동자들이 노조 조직을 시도했습니다.[41] 2023년 7월 1일, 하버드 정부 및 아프리카계 미국인 학과 교수이자 예술 및 과학 학부 학장인 Claudine Gay가 바코우의 뒤를 이어 제 30대 총장이 되었습니다. 2024년 1월, 프로보스트 앨런 가버는 게이가 사임한 후 게이의 뒤를 이어 임시 대통령이 되었습니다.[42]

캠퍼스

케임브리지

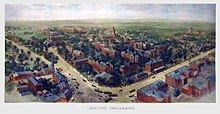

209 에이커(85 ha)에 달하는 하버드의 메인 캠퍼스는 보스턴 도심에서 북서쪽으로 약 3 마일(5 km) 떨어진 캠브리지의 하버드 야드("The Yard")를 중심으로 하며, 주변의 하버드 스퀘어 인근까지 뻗어 있습니다. 마당에는 유니버시티 홀과 메사추세츠 홀과 같은 행정 사무실, 와이드너, 푸시, 휴튼, 라몬트와 같은 도서관, 그리고 메모리얼 교회가 있습니다.

야드와 인접한 지역에는 세버 홀과 하버드 홀과 같은 단과대학을 포함한 예술 과학 학부의 주요 학술 건물이 포함됩니다.

신입생 기숙사는 마당에 있거나 그 근처에 있습니다. 상위 계층의 사람들은 12개의 거주 주택에 살고 있습니다. 9개의 주택은 찰스 강 근처 야드에서 남쪽으로, 나머지는 야드에서 북서쪽으로 반 마일 떨어진 래드클리프 쿼드랭글(이전에 래드클리프 대학 학생들이 거주했던 곳)에 있습니다. 각 집은 학부생, 교직원 및 거주 교사의 커뮤니티이며 자체 식당, 도서관 및 레크리에이션 시설이 있습니다.[43]

또한 케임브리지에는 래드클리프 야드에 있는 래드클리프 고등연구소뿐만 아니라 법학, 신학(신학), 공학 및 응용과학, 디자인(건축), 교육, 케네디(공공정책), 확장 학교가 있습니다.[44] 하버드는 케임브리지에 상업용 부동산도 보유하고 있습니다.[45][46]

올스턴

하버드 비즈니스 스쿨, 하버드 이노베이션 랩, 그리고 하버드 스타디움을 포함한 많은 운동 시설들이 358 에이커(145 ha)의 캠퍼스에 위치해 있습니다.[47] 캠브리지 캠퍼스에서 찰스 강 바로 건너편 보스턴 지역 올스턴에 위치해 있습니다. 존 W. 찰스 강 위의 보행자 다리인 위크스 브리지는 두 캠퍼스를 연결합니다.

이 대학은 캠브리지보다 더 많은 땅을 소유하고 있는 올스턴으로 적극적으로 확장하고 있습니다.[48] 계획에는 비즈니스 스쿨, 호텔 및 컨퍼런스 센터, 대학원생 주택, 하버드 스타디움 및 기타 운동 시설의 신축 및 개조가 포함됩니다.[49]

2021년 하버드 존 A. Paulson School of Engineering and Application Sciences는 Allston에 50만 평방 피트 이상의 새로운 과학 및 공학 복합 건물(SEC)로 확장되었습니다.[50] SEC는 성숙한 기업과의 협업뿐만 아니라 기술 및 생명과학 중심의 스타트업을 장려하기 위해 엔터프라이즈 리서치 캠퍼스, 비즈니스 스쿨 및 하버드 이노베이션 랩과 인접해 있습니다.[51]

롱우드

의학, 치과 의학, 공중 보건 학교는 캠브리지 캠퍼스에서 남쪽으로 약 3.3마일(5.3km) 떨어진 보스턴의 롱우드 의학 및 학술 지역에 있는 21에이커(8.5ha)의 캠퍼스에 위치해 있습니다.[14] 롱우드에는 베스 이스라엘 디콘세스 메디컬 센터, 보스턴 어린이 병원, 브리검 여성 병원, 다나-파버 암 연구소, 조슬린 당뇨병 센터, 와이스 생물학적으로 영감을 받은 공학 연구소 등 여러 하버드 부속 병원과 연구소도 있습니다. 추가적인 계열사들, 특히 매사추세츠 종합병원은 그레이터 보스턴 지역 전역에 위치하고 있습니다.

다른.

하버드는 워싱턴 D.C.에 있는 덤바튼 오크 연구 도서관과 컬렉션, 매사추세츠 주 페테르햄에 있는 하버드 포레스트, 매사추세츠 주 콩코드에 있는 에셋룩 우즈에 있는 콩코드 필드 스테이션,[52] 이탈리아 피렌체에 있는 빌라 이 타티 연구 센터,[53] 중국 상하이에 있는 하버드 상하이 센터,[54] 그리고 보스턴 자메이카 평원에 있는 아놀드 수목원.

조직 및 관리

거버넌스

| 학교 | 설립 |

| 하버드 칼리지 | 1636 |

| 약 | 1782 |

| 신성 | 1816 |

| 법 | 1817 |

| 공학 및 응용과학 | 1847 |

| 치과의학 | 1867 |

| 예술과 과학 | 1872 |

| 비지니스 | 1908 |

| 확장 | 1910 |

| 설계. | 1936 |

| 교육 | 1920 |

| 공중보건 | 1913 |

| 정부 | 1936 |

하버드는 감독 위원회와 하버드 대학교 총장 및 펠로우(Harvard Corporation이라고도 함)의 조합에 의해 관리되며, 하버드 대학교 총장을 임명합니다.[55] 교수, 강사, 강사 [56]등 2400여 명의 직원과 교수진 1만6000여 명이 근무하고 있습니다.[57]

예술과 과학 학부는 하버드 대학에서 가장 큰 학부이며 예술과 과학 대학원인 하버드 대학의 교육에 대한 주요 책임을 지고 있습니다. 공학 및 응용 과학의 폴슨 스쿨(SEAS), 하버드 서머 스쿨과 하버드 익스텐션 스쿨을 포함하는 지속 교육 부서. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study 뿐만 아니라 9개의 다른 대학원 및 전문 교수진이 있습니다.

매사추세츠 공과대학교와의 공동 프로그램으로는 하버드 대학교가 있습니다.보건 과학 기술 분야의 MIT 프로그램, the Broad Institute, the Observatory of Economic Complexity, 그리고 edX.

기부금

하버드는 2023년 기준으로 약 507억 달러의 가치를 지닌 세계에서 가장 큰 대학 기부금을 보유하고 있습니다.[3][4] 2007-2009년의 불황기 동안, 대규모 예산 삭감, 특히 Allston Science Complex의 건설을 일시적으로 중단시키는 심각한 손실을 입었습니다.[58] 그 후 기부금이 회복되었습니다.[59][60][61][62]

연간 약 20억 달러의 투자 수익이 펀드 운영에 분배됩니다.[63] 하버드의 학위 및 재정 지원 프로그램에 대한 자금 지원 능력은 기부금의 성과에 달려 있습니다. 2016 회계연도의 저조한 성과로 인해 예술 및 과학 학부가 지원하는 대학원생의 수가 4.4% 감소했습니다.[64] 기부금 수입은 학생들의 등록금, 수수료, 숙식비에서 22%만 나오기 때문에 매우 중요합니다.[65]

처분

1970년대부터 학생 주도의 여러 캠페인은 아파르트헤이트 남아프리카 공화국, 다르푸르 대학살 당시 수단, 담배, 화석 연료 및 개인 교도소 산업에 대한 투자를 포함하여 논란이 많은 소지품에서 하버드의 기부금을 처분하는 것을 지지했습니다.[66][67]

1980년대 후반, 남아프리카 공화국에서 탈퇴 운동이 일어나는 동안, 학생 운동가들은 하버드 야드에 상징적인 "판잣집"을 세웠고, 듀크 켄트 브라운 남아프리카 공화국 부영사의 연설을 막았습니다.[68][69] 이 대학은 압력에 대응하여 결국 남아프리카 공화국의 보유액을 2억 3천만 달러(4억 달러 중)나 줄였습니다.[68][70]

학술

교수학습

하버드는 50개의 학부 전공,[73] 134개의 대학원 학위 [74]및 32개의 전문 학위를 제공하는 거주성이 높은 대규모 연구 대학입니다[72].[75] 2018-2019 학년도 동안 하버드는 1,665개의 바칼로레아 학위, 1,013개의 대학원 학위 및 5,695개의 전문 학위를 수여했습니다.[75]

4년제 정규 학부 과정인 하버드 대학은 문과 과학에 중점을 두고 있습니다.[72][73] 보통 4년 동안 졸업하기 위해 학부생들은 보통 한 학기에 4개의 과정을 듣습니다.[76] 대부분의 전공에서 우등 학위는 고급 과정과 수석 논문이 필요합니다.[77] 일부 입문 과정은 수강 인원이 많지만, 중간 학급 규모는 12명입니다.[78]

조사.

하버드(Harvard)는 미국 대학 협회(Association of American Universities[79])의 창립 회원이며 카네기 분류에 따라 예술, 과학, 공학 및 의학 분야에 걸쳐 "매우 높은" 연구 활동(R1)과 포괄적인 박사 과정을 가진 탁월한 연구 대학입니다.[72]

의과대학이 연구 대상 의과대학 중 지속적으로 1위를 차지하고 있는 가운데,[80] 생물의학 연구는 대학에 특히 강점이 있는 분야입니다. 11,000명 이상의 교수진과 1,600명 이상의 대학원생들이 의대와 15개의 부속 병원 및 연구소에서 연구를 수행합니다.[81] 의과대학과 그 부속 기관들은 2019년 국립보건원으로부터 다른 대학들보다 두 배 이상 많은 16억 5천만 달러의 경쟁적인 연구 보조금을 유치했습니다.[82]

도서관 및 박물관

하버드 도서관 시스템은 하버드 야드(Harvard Yard)에 있는 와이드너 도서관(Widener Library)을 중심으로 하며, 약 2,040만 개의 물품을 보유하고 있는 거의 80개의 개별 도서관으로 구성되어 있습니다.[83][84][85] 미국 도서관 협회에 따르면, 이 도서관은 미국에서 소장하고 있는 도서관 중 네 번째로 큰 도서관이라고 합니다.[86][5]

Houghton Library, Arthur and Elizabeth Schulzinger Library in America's Women History, 그리고 Harvard University Archive는 주로 희귀하고 독특한 자료들로 구성되어 있습니다. 미국에서 가장 오래된 지도, 가제트, 아틀라스 컬렉션은 푸시 도서관에 보관되어 일반에 공개됩니다. 동아시아 이외의 지역에서 가장 큰 규모의 동아시아 언어 자료 모음은 하버드 옌칭 도서관에서 열리고 있습니다.

하버드 미술관은 3개의 박물관으로 구성되어 있습니다. 아서 M. 새클러 박물관은 아시아, 지중해, 이슬람 미술을, 부쉬-라이징거 박물관(구 게르만 박물관)은 중북부 유럽 미술을, 포그 박물관은 이탈리아 초기 르네상스, 영국 라파엘로 이전, 19세기 프랑스 미술을 강조하는 중세부터 현재까지의 서양 미술을 다루고 있습니다. 하버드 과학문화박물관은 하버드 자연사박물관으로 구성되어 있는데, 이 박물관은 하버드 광물 지질 박물관, 하버드 대학교 허바리아에서 블래쉬카 유리꽃 전시회, 비교 동물학 박물관, 하버드 역사 과학 도구 모음, 하버드 과학 센터, 중동에서 발굴된 유물을 전시한 하버드 고대 근동 박물관, 서반구의 문화 역사와 문명을 전문으로 하는 피바디 고고학 및 민족학 박물관에서 발견되었습니다. 다른 박물관으로는 르 코르뷔지에가 디자인하고 영화 아카이브를 소장하고 있는 시각예술을 위한 카펜터 센터; 워렌 해부학 박물관, 하버드 의과대학 의학사 센터, 허친스 아프리카 및 아프리카계 미국인 연구 센터의 에델버트 쿠퍼 갤러리에서 발견되었습니다.

평판과 순위

| 학벌순위 | |

|---|---|

| 국가의 | |

| ARWU[87] | 1 |

| 포브스[88] | 9 |

| THE / WSJ[89] | 6 |

| U.S. 뉴스 & 월드 리포트[90] | 3 |

| 워싱턴 월간지[91] | 1 |

| 세계적인 | |

| ARWU[92] | 1 |

| QS[93] | 4 |

| 그[94] | 4 |

| U.S. 뉴스 & 월드 리포트[95] | 1 |

| 전국 졸업생 순위[96] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 프로그램. | 랭킹 | ||

| 생물과학 | 4 | ||

| 비지니스 | 6 | ||

| 화학 | 2 | ||

| 임상심리학 | 10 | ||

| 컴퓨터 사이언스 | 16 | ||

| 지구과학 | 8 | ||

| 경제학 | 1 | ||

| 교육 | 1 | ||

| 공학 기술 | 22 | ||

| 영어 | 8 | ||

| 역사 | 4 | ||

| 법 | 3 | ||

| 수학 | 2 | ||

| 의학: 프라이머리 케어 | 10 | ||

| 약: 조사. | 1 | ||

| 물리학 | 3 | ||

| 정치학 | 1 | ||

| 심리학 | 3 | ||

| 공보 | 3 | ||

| 공중보건 | 2 | ||

| 사회학 | 1 | ||

| 글로벌 주제 순위[97] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 프로그램. | 랭킹 | ||

| 농업과학 | 22 | ||

| 예술과 인문학 | 2 | ||

| 생물학과 생화학 | 1 | ||

| 심장 및 심혈관 시스템 | 1 | ||

| 화학 | 15 | ||

| 임상의학 | 1 | ||

| 컴퓨터 사이언스 | 47 | ||

| 경제 & 비즈니스 | 1 | ||

| 전기전자공학 | 136 | ||

| 공학 기술 | 27 | ||

| 환경/생태 | 5 | ||

| 지구과학 | 7 | ||

| 면역학 | 1 | ||

| 머티리얼 사이언스 | 7 | ||

| 수학 | 12 | ||

| 미생물학 | 1 | ||

| 분자생물학과 유전학 | 1 | ||

| 신경과학과 행동 | 1 | ||

| 종양학 | 1 | ||

| 약리학과 독성학 | 1 | ||

| 물리학 | 4 | ||

| 식물과 동물과학 | 13 | ||

| 정신의학/심리학 | 1 | ||

| 사회과학과 공중보건 | 1 | ||

| 스페이스 사이언스 | 2 | ||

| 수술. | 1 | ||

QS와 Times Higher Education이 협력하여 Times Higher Education을 발행했을 때-2004년부터 2009년까지 QS 세계 대학 순위에서 하버드는 매년 1위를 차지했고 2011년에 발표된 이후로 계속해서 세계 평판 순위에서 1위를 차지했습니다.[98] 대학 성과 측정 센터(Center for Measurement University Performance)의 2023년 보고서에서 컬럼비아(Columbia), MIT(MIT), 스탠포드(Stanford)와 함께 미국 연구 대학의 1등급에 올랐습니다.[99] 하버드 대학교는 뉴잉글랜드 고등교육위원회의 인가를 받았습니다.[100]

특정 지표 순위 중 하버드는 학업성적에 의한 대학 순위(2019-2020)와 마인즈 파리에서 모두 1위를 차지했습니다.Tech: Fortune Global 500대 기업에서 CEO직을 맡고 있는 대학들의 동문 수를 측정한 세계 대학의 전문 순위(2011).[101] The Princeton Review가 실시한 연례 여론 조사에 따르면, 하버드는 학생들과 학부모들 모두에게 미국에서 가장 흔히 이름 지어진 꿈의 대학 2위 안에 지속적으로 들어있습니다.[102][103][104] 또한, 최근 몇 년 동안 공학 학교에 상당한 투자를 한 하버드는 2019년 타임즈 고등 교육에 의해 공학 및 기술 부문에서 전 세계 3위에 올랐습니다.[105]

국제 관계에 있어서 포린 폴리시 잡지는 하버드를 학부 수준에서 세계 최고, 대학원 수준에서 에드먼드 A에 이어 세계 2위로 평가하고 있습니다. 조지타운 대학교의 월시 외국인 서비스 대학원.[106]

| 학교 | 설립 | 등록 | U.S. 뉴스 & 월드 리포트 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 하버드 대학교 | 1636 | 31,345[107] | 3[108] |

| 약 | 1782 | 660 | 1[109] |

| 신성 | 1816 | 377 | 해당 없음 |

| 법 | 1817 | 1,990 | 4[110] |

| 치과의학 | 1867 | 280 | 해당 없음 |

| 예술과 과학 | 1872 | 4,824 | 해당 없음 |

| 비지니스 | 1908 | 2,011 | 5[111] |

| 확장 | 1910 | 3,428 | 해당 없음 |

| 설계. | 1914 | 878 | 해당 없음 |

| 교육 | 1920 | 876 | 2[112] |

| 공중보건 | 1922 | 1,412 | 3[111] |

| 정부 | 1936 | 1,100 | 6[113] |

| 공학 기술 | 2007 | 1,750 | 21[114] |

학생생활

| 인종과 민족[115] | 총 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 하얀색 | 36% | ||

| 아시아의 | 21% | ||

| 히스패닉계 | 12% | ||

| 외국 국적 | 11% | ||

| 블랙입니다. | 11% | ||

| 기타[Notes 2] | 9% | ||

| 경제적 다양성 | |||

| 저소득층[주3] | 18% | ||

| 부유한[주4] | 82% | ||

학생정부

학부 위원회는 대학생들을 대표합니다. 대학원 위원회는 12개의 모든 대학원 및 전문 학교의 학생들을 대표하며, 대부분은 자체 학생 정부를 가지고 있습니다.[116]

애슬레틱스

학부와 대학원 모두 교내 스포츠 프로그램을 운영하고 있습니다.

하버드 대학은 NCAA 디비전 I 아이비리그 컨퍼런스에 참가합니다. 이 학교에는 42개의 대학간 스포츠 팀이 있는데, 이는 미국의 다른 어떤 대학보다도 많은 수치입니다.[117] 2년마다 하버드와 예일의 육상팀이 모여 옥스포드와 캠브리지를 합친 세계에서 가장 오래된 지속적인 국제 아마추어 대회와 경쟁합니다.[118] 다른 아이비리그 대학들과 마찬가지로, 하버드도 체육 장학금을 제공하지 않습니다.[119] 학교 색깔은 진홍색입니다.

하버드와 예일의 운동 경쟁은 그들이 만나는 모든 스포츠에서 치열하며, 1875년으로 거슬러 올라가는 연례 축구 회의에서 매년 가을 절정에 이르렀습니다.[120]

하버드 대학교 가제트

하버드 가제트(Harvard Gazet)는 하버드 대학교의 공식 언론기관입니다. 예전에는 인쇄 출판물이었지만, 현재는 웹 사이트가 되었습니다. 대학의 연구, 교수, 교수 및 행사를 출판합니다. 1906년에 시작된 이 달력은 원래 뉴스와 이벤트의 주간 달력이었습니다. 1968년에는 주간지가 되었습니다.

가제트가 인쇄물이었을 때, "주간 독서가 가장 적합하다면, 가장 포괄적이고 권위 있는 매체는 하버드 대학 가제트"라는 하버드 뉴스를 따라가는 좋은 방법으로 여겨졌습니다.

2010년, 가제트는 "인쇄 우선에서 디지털 우선, 모바일 우선" 출판물로 전환했고, 발행 일정을 격주로 단축하는 한편, 이전에 보스턴 글로브, 마이애미 헤럴드 및 AP 통신에서 일했던 일부 기자들을 포함하여 동일한 수의 기자들을 유지했습니다.

주목할 만한 사람들

동문

하버드 대학교 동문들은 3세기 반 이상 동안 사회, 예술, 과학, 비즈니스, 국내외 문제에 창의적이고 중요한 기여를 해왔습니다.

하버드의 계열사([Notes 1]공식 집계)는 8명의 미국 대통령, 188명의 살아있는 억만장자, 49명의 노벨상 수상자, 7명의 필즈상 수상자, 9명의 튜링상 수상자, 369명의 로도스상 수상자, 252명의 마셜상 수상자, 13명의 미첼상 수상자를 포함합니다.[121][122][123][124] 하버드 학생들과 졸업생들은 10개의 아카데미상, 48개의 퓰리처상, 108개의 올림픽 메달(46개의 금메달 포함)을 수상했고, 그들은 전세계적으로 많은 주목할 만한 회사들을 설립했습니다.[125][126]

- 하버드 대학교의 저명한 동문은 다음과 같습니다.

- 수필가, 강사, 철학자, 시인 Ralph Waldo Emerson (AB, 1821)

- 자연주의자, 수필가, 시인, 철학자 헨리 데이비드 소로우 (AB, 1837)

- 철학자, 논리학자, 수학자 찰스 샌더스 피어스 (AB, 1862, SB 1863)

- 저자, 정치 운동가, 강사 헬렌 켈러 (AB, 1904, 래드클리프 칼리지)

- 시인이자 노벨 문학상 수상자 T. S. 엘리엇 (AB, 1909; AM, 1910)

- 음악가 겸 작곡가 레너드 번스타인 (AB, 1939)

- 수학자이자 국내 테러리스트 테드 카친스키(AB, 1962)

- 제7대 아일랜드 대통령과 유엔 인권 고등판무관 메리 로빈슨 (LLM, 1968)

- 미국 제45대 부통령이자 노벨 평화상 수상자인 앨 고어 (AB, 1969)

- 척 슈머 상원 원내대표 (AB, 1971; JD, 1975)

- 제11대 파키스탄 총리 베나지르 부토 (AB, 1973, 래드클리프 칼리지)

- 제14대 연방준비제도이사회 의장이자 노벨 경제학상 수상자 벤 버냉키(AB, 1975; AM, 1975)

- 제17대 미국 대법원장 존 로버츠(AB, 1976; JD, 1979)

- 제8대 유엔 사무총장 반기문(MPA, 1984)

- 미국 연방대법원 엘레나 케이건 대법관(JD, 1986)

- 전 미국 영부인 미셸 오바마 (JD, 1988)

교수진

- 현재 및 과거 하버드 대학교 교수진은 다음과 같습니다.

문학과 대중문화

하버드를 엘리트 성취의 중심지, 혹은 엘리트 특권의 중심지로 인식하면서 문학과 영화를 배경으로 자주 사용하게 되었습니다. "영화의 문법에서 하버드는 전통과 어느 정도의 충실함을 모두 의미하게 되었습니다"라고 영화 평론가 폴 셔먼은 말했습니다.[139]

문학.

- 윌리엄 포크너의 "소리와 분노" (1929)와 "압살롬, 압살롬!" (1936)은 둘 다 하버드 학생들의 삶을 묘사하고 있습니다.[non-primary source needed]

- 토마스 울프(Thomas Wolfe)의 "시간과 강"(Of Time and the River, 1935)은 소설화된 자서전으로 그의 다른 자아가 하버드에서 보낸 시간을 포함하고 있습니다.[non-primary source needed]

- 존 P. 마퀀드의 고 조지 애플리 (1937)는 20세기 초 하버드 남성들을 패러디했습니다;[non-primary source needed] 그것은 퓰리처상을 수상했습니다.

- John P. Marquand Jr.의 "두 번째로 행복한 날"(1953)은 2차 세계대전 세대의 하버드를 묘사합니다.[140][141][142][143][144]

영화

하버드는 부동산에서 촬영하는 것을 거의 허용하지 않기 때문에, 하버드를 배경으로 하는 대부분의 장면(특히 실내 촬영이지만, 공중 촬영이나 하버드 스퀘어와 같은 공공 지역의 촬영은 제외)은 사실 다른 곳에서 촬영됩니다.[145][146]

- 러브 스토리(1970)는 부유한 하버드 하키 선수(라이언 오닐)와 겸손한 수단의 뛰어난 래드클리프 학생(앨리 맥그로)의 로맨스에 관한 이야기입니다. 매년 신입생을 대상으로 상영됩니다.[147][148][149]

- 페이퍼 체이스 (1973)[150]

- 작은 친구들의 원 (1980)[145]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ a b 대학들은 노벨상이나 다른 학술상 계열사를 주장하기 위해 다양한 지표를 채택하고 있으며, 어떤 것은 관대한 반면, 어떤 것은 더 엄격합니다.

하버드 공식 집계(49세)2023년 3월 22일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 것은 수상 당시 소속된 학자들만 해당됩니다. 그러나 다른 대학들이 하는 것처럼 다양한 계층의 방문자와 교수들을 모두 포함한다면 (가장 관대한 기준) 이 수치는 전 세계적으로 가장 많은 160여 개의 노벨 계열사까지 될 수 있습니다.- "50 (US) Universities with the Most Nobel Prize Winners". www.bestmastersprograms.org. February 25, 2021. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Rachel Sugar (May 29, 2015). "Where MacArthur 'Geniuses' Went to College". businessinsider.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- "Top Producers". us.fulbrightonline.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "US Rhodes Scholars Over Time". www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- "Harvard, Stanford, Yale Graduate Most Members of Congress". Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- "The complete list of Fields Medal winners". areppim AG. 2014. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ 다른 사람들은 다인종 미국인들과 말하지 않기를 선호하는 사람들로 구성되어 있습니다.

- ^ 저소득층 학생을 위한 소득 기반 연방 펠 보조금을 받은 학생의 비율입니다.

- ^ 최소한 미국 중산층의 일부인 학생들의 비율입니다.

참고문헌

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (1968). The Founding of Harvard College. Harvard University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-674-31450-4. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ 1636년 10월 28일(OS), 9월 8일에 소집된 회의에서 "학교 또는 대학"에 대한 400파운드의 지출이 투표되어 10월 28일로 정회되었습니다. 어떤 자료들은 1636년 10월 28일 (OS) (1636년 11월 7일, NS)을 창립일로 간주합니다. 하버드의 1936년 100주년 기념식은 1836년 9월 8일에 200주년 기념식이 열렸음에도 불구하고 9월 18일을 창립일로 취급했습니다. 자료: 회의 날짜, p. 586 2015년 9월 6일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 "1636년 9월 8일 홀든 법원에서 8월 28일(1636년 10월)까지 휴정을 계속했습니다. 법원은 학교나 대학에 400파운드를 주기로 합의했고, 200파운드는 내년에 지급될 예정입니다." 100주년 기념일은 다음과 같습니다. "하버드는 매사추세츠 그레이트 앤드 제너럴 법원이 설립을 허가하기 위해 소집된 날에 출생한다고 주장합니다. 이것은 율리우스력으로 1637년 9월 8일이었습니다. 그레고리력을 10일 앞당기는 것을 허용하면서, 100주년 기념일은 기념의 세 번째이자 마지막 중요한 날인 9월 18일에 도착했습니다." "1636년 10월 28일... 그 '학교나 대학'에 대한 400파운드는 매사추세츠만 식민지의 대법정과 일반법정이 투표했습니다." 200주년 기념일: , "1836년 9월 8일 – 약 1,100명에서 1,300명의 동문들이 하버드의 200주년 기념행사에 몰려들고, 그곳에서 전문 합창단이 "페어 하버드"를 초연합니다. ... 1821년 클래스의 객원 연사인 조시아 퀸시 주니어는 만장일치로 '이 총동문회는 1936년 9월 8일 이 장소에서 만나기로 정회되어야 한다'는 동의안을 채택했습니다.'" 퀸시의 봉인된 패키지의 3세기 개봉: 뉴욕 타임즈, 1936년 9월 9일 24쪽 "1836년에 봉인된 패키지가 하버드에서 열렸습니다. "1936년 9월 8일: 하버드 100주년 기념식의 첫 번째 공식 행사로서, 하버드 동문회는 1836년 하버드 200주년 기념식에서 조시아 퀸시 대통령이 봉인한 '신비한' 포장지의 코난트 대통령의 개막식을 목격했습니다."

- ^ a b c "Harvard posts investment gain in fiscal 2023, endowment stands at $50.7 billion". Reuters.com. October 20, 2023. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c Financial Report Fiscal Year 2023 (PDF) (Report). Harvard University. October 19, 2023. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ a b "Harvard University Graphic Identity Standards Manual" (PDF). July 14, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Common Data Set 2022–2023" (PDF). Office of Institutional Research. Harvard University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "IPEDS – Harvard University". Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ "Color Scheme" (PDF). Harvard Athletics Brand Identity Guide. July 27, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ 예를 들면 다음과 같습니다.

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–481. ISBN 0-19-514457-0.

Harvard's professional schools... won world prestige of a sort rarely seen among social institutions. [...] Harvard's age, wealth, quality, and prestige may well shield it from any conceivable vicissitudes.

- Spaulding, Christina (1989). "Sexual Shakedown". In Trumpbour, John (ed.). How Harvard Rules: Reason in the Service of Empire. South End Press. pp. 326–336. ISBN 0-89608-284-9.

... [Harvard's] tremendous institutional power and prestige [...] Within the nation's (arguably) most prestigious institution of higher learning ...

- David Altaner (March 9, 2011). "Harvard, MIT Ranked Most Prestigious Universities, Study Reports". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Collier's Encyclopedia. Macmillan Educational Co. 1986.

Harvard University, one of the world's most prestigious institutions of higher learning, was founded in Massachusetts in 1636.

- Newport, Frank (August 26, 2003). "Harvard Number One University in Eyes of Public Stanford and Yale in second place". Gallup. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- Leonhardt, David (September 17, 2006). "Ending Early Admissions: Guess Who Wins?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

The most prestigious college in the world, of course, is Harvard, and the gap between it and every other university is often underestimated.

- Hoerr, John (1997). We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard. Temple University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781566395359.

- Wong, Alia (September 11, 2018). "At Private Colleges, Students Pay for Prestige". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

Americans tend to think of colleges as falling somewhere on a vast hierarchy based largely on their status and brand recognition. At the top are the Harvards and the Stanfords, with their celebrated faculty, groundbreaking research, and perfectly manicured quads.

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–481. ISBN 0-19-514457-0.

- ^ Story, Ronald (1975). "Harvard and the Boston Brahmins: A Study in Institutional and Class Development, 1800–1865". Journal of Social History. 8 (3): 94–121. doi:10.1353/jsh/8.3.94. S2CID 147208647.

- ^ Farrell, Betty G. (1993). Elite Families: Class and Power in Nineteenth-Century Boston. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1593-7.

- ^ a b "Member Institutions and years of Admission". aau.edu. Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ "Faculties and Allied Institutions" (PDF). harvard.edu. Office of the Provost, Harvard University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "Faculties and Allied Institutions" (PDF). Office of the Provost, Harvard University. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (1968). The Founding of Harvard College. Harvard University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-674-31450-4. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon (March 8, 2012). "The instrument behind New England's first literary flowering". harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Rowley and Ezekiel Rogers, The First North American Printing Press" (PDF). hull.ac.uk. Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Harvard, John. "John Harvard Facts, Information". encyclopedia.com. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

He bequeathed £780 (half his estate) and his library of 320 volumes to the new established college at Cambridge, Mass., which was named in his honor.

- ^ Wright, Louis B. (2002). The Cultural Life of the American Colonies (1st ed.). Dover Publications (published May 3, 2002). p. 116. ISBN 978-0-486-42223-7.

- ^ Grigg, John A.; Mancall, Peter C. (2008). British Colonial America: People and Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-59884-025-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Harvard Office of News and Public Affairs (July 26, 2007). "Harvard guide intro". Harvard University. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ John Lebret – History – 2010년 6월 12일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 사장실

- ^ a b Dorrien, Gary J. (January 1, 2001). The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion, 1805–1900. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22354-0. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Field, Peter S. (2003). Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-8843-2. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Shoemaker, Stephen P. (2006–2007). "The Theological Roots of Charles W. Eliot's Educational Reforms". Journal of Unitarian Universalist History. 31: 30–45.

- ^ "An Iconic College View: Harvard University, circa 1900. Richard Rummell (1848–1924)". An Iconic College View. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Schwager, Sally (2004). "Taking up the Challenge: The Origins of Radcliffe". In Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (ed.). Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 1-4039-6098-4.

- ^ First class of women admitted to Harvard Medical School, 1945 (Report). Countway Repository, Harvard University Library. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ Radcliffe Enters Historic Merger With Harvard (Report). Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Jerome Karabel (2006). The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-618-77355-8. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "공존의 의무: 하버드 대학교 신입생 주거지의 차별 철폐 역사"2022년 9월 28일, 하버드 크림슨 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에 보관, 2021년 11월 4일

- ^ Steinberg, Stephen (September 1, 1971). "How Jewish Quotas Began". Commentary. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (March 4, 1986). "Yale's Limit on Jewish Enrollment Lasted Until Early 1960's Book Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Lowell Tells Jews Limits at Colleges Might Help Them". The New York Times. June 17, 1922. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Kridel, Craig, ed. (2010). "General Education in a Free Society (Harvard Redbook)". Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies. Vol. 1. SAGE. pp. 400–402. ISBN 978-1-4129-5883-7.

- ^ "The Class of 1950 News The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ 말카 A. 연상. (1996) 2009년 9월 11일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 예비 학교와 입학 절차. 하버드 크림슨, 1996년 1월 24일

- ^ Powell, Alvin (October 1, 2018). "An update on Harvard's diversity, inclusion efforts". The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Harvard Board Names First Woman President". NBC News. Associated Press. February 11, 2007. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Harvard University names Lawrence Bacow its 29th president". Fox News. Associated Press. February 11, 2018. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Quinn, Ryan. "Harvard Postdocs, Other Non-Tenure-Track Trying to Unionize". www.insidehighered.com. Inside Higher Education. Archived from the original on December 8, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ "HARVARD PRESIDENT CLAUDINE GAY RESIGNS, SHORTEST TENURE IN UNIVERSITY HISTORY News The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "The Houses". Harvard College Dean of Students Office. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University". Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Institutional Ownership Map – Cambridge Massachusetts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Tartakoff, Joseph M. (January 7, 2005). "Harvard Purchases Doubletree Hotel Building – News – The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Logan, Tim (April 13, 2016). "Harvard continues its march into Allston, with science complex". BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Allston Planning and Development / Office of the Executive Vice President". harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Bayliss, Svea Herbst (January 21, 2007). "Harvard unveils big campus expansion". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ O'Rourke, Brigid (April 10, 2020). "SEAS moves opening of Science and Engineering Complex to spring semester '21". The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Our Campus". harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "Concord Field Station". mcz.harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Villa I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies". Itatti.it. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Shanghai Center". Harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; Shenton, Robert (2009). Harvard A to Z. Harvard University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-674-02089-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ 벌링턴 자유언론, 2009년 6월 24일 11B페이지, "275명을 감원하는 하버드" AP통신

- ^ Office of Institutional Research (2009). Harvard University Fact Book 2009–2010 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. ("교수")

- ^ Vidya B. Viswanathan and Peter F. Zhu (March 5, 2009). "Residents Protest Vacancies in Allston". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Healy, Beth (January 28, 2010). "Harvard endowment leads others down". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Hechinger, John (December 4, 2008). "Harvard Hit by Loss as Crisis Spreads to Colleges". The Wall Street Journal. p. A1.

- ^ Munk, Nina (August 2009). "Nina Munk on Hard Times at Harvard". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Andrew M. Rosenfield (March 4, 2009). "Understanding Endowments, Part I". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 19, 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "A Singular Mission". Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Admissions Cuts Concern Some Graduate Students". Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Financial Report" (PDF). harvard.edu. October 24, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Welton, Alli (November 20, 2012). "Harvard Students Vote 72 Percent Support for Fossil Fuel Divestment". The Nation. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Chaidez, Alexandra A. (October 22, 2019). "Harvard Prison Divestment Campaign Delivers Report to Mass. Hall". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b George, Michael C.; Kaufman, David W. (May 23, 2012). "Students Protest Investment in Apartheid South Africa". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Cadambi, Anjali (September 19, 2010). "Harvard University community campaigns for divestment from apartheid South Africa, 1977–1989". Global Nonviolent Action Database. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Robert Anthony Waters Jr. (March 20, 2009). Historical Dictionary of United States-Africa Relations. Scarecrow Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8108-6291-3. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Harvard College. "A Brief History of Harvard College". Harvard College. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Carnegie Classifications – Harvard University". iu.edu. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ a b "Liberal Arts & Sciences". harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Degree Programs" (PDF). Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Handbook. pp. 28–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ a b "Degrees Awarded". harvard.edu. Office of Institutional Research, Harvard University. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "The Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science Degrees". college.harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Academic Information: The Concentration Requirement". Handbook for Students. Harvard College. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ "How large are classes?". harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Member Institutions and Years of Admission". Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ "2023 Best Medical Schools: Research". usnews.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ "Research at Harvard Medical School". hms.harvard.edu. Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ "Which schools get the most research money?". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Harvard Library Annual Report FY 2013". Harvard University Library. 2013. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ "The Nation's Largest Libraries: A Listing By Volumes Held". American Library Association. May 2009. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ^ Harvard Media Relations. "Quick Facts". Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Library, A. L. A. "LibGuides: Library Statistics and Figures: The Nation's Largest Libraries: A Listing by Volumes Held". libguides.ala.org. Archived from the original on June 23, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2023". Forbes. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2022". The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "2022 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2024: Top global universities". Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ "2022-23 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "Harvard University's Graduate School Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "Harvard University – U.S. News Global University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings 2016". Times Higher Education. 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Lombardi, John V.; Abbey, Craig W.; Craig, Diane D.; Collis, Lynne N. (2021). "The Top American Research Universities: 2023 Annual Report" (PDF). mup.umass.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2023.

- ^ Massachusetts Institutions, New England Commission of Higher Education, archived from the original on August 17, 2021, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ "World Ranking". University Ranking by Academic Performance. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ "College Hopes & Worries Press Release". PR Newswire. 2016. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Princeton Review's 2012 "College Hopes & Worries Survey" Reports on 10,650 Students' & Parents' Top 10 "Dream Colleges" and Application Perspectives". PR Newswire. 2012. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "2019 College Hopes & Worries Press Release". 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ contact, Press (February 11, 2019). "Harvard is #3 in World University Engineering Rankings". Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "The Best International Relations Schools in the World". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "Harvard University Campus Information, Costs and Details". www.collegeraptor.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "US News National University Rankings". Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "2022 Best Graduate Schools". U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "US News Law School Rankings". Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "2022 Best Graduate Schools". U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "US News Best Education Programs". Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "2022 Best Graduate Schools". U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ "2022 Best Graduate Schools". U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "College Scorecard: Harvard University". United States Department of Education. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ a) 로스쿨 학생 정부 [1]2021년 6월 24일 웨이백 기계에 보관

b) 교육학교 총학생회 [2]2022년 7월 19일 웨이백 머신에 보관

c) Kennedy School Student Government [3] 2021년 6월 21일 Wayback Machine에 보관

d) 디자인 스쿨 학생 포럼 [4]Wayback Machine에서 2021년 6월 14일 보관

e) 하버드 의과대학 및 하버드 치과대학 학생회 [5] 2021년 6월 10일 웨이백 머신에 보관 - ^ "Harvard : Women's Rugby Becomes 42nd Varsity Sport at Harvard University". Gocrimson.com. August 9, 2012. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ "Yale and Harvard Defeat Oxford/Cambridge Team". Yale University Athletics. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ "The Harvard Guide: Financial Aid at Harvard". Harvard University. September 2, 2006. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Bracken, Chris (November 17, 2017). "A game unlike any other". yaledailynews.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Siliezar, Juan (November 23, 2020). "2020 Rhodes, Mitchell Scholars named". harvard.edu. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Communications, FAS (November 24, 2019). "Five Harvard students named Rhodes Scholars". The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Kathleen Elkins (May 18, 2018). "More billionaires went to Harvard than to Stanford, MIT and Yale combined". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize Winners". Harvard University. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Companies – Entrepreneurship – Harvard Business School". entrepreneurship.hbs.edu. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Barzilay, Karen N. "The Education of John Adams". Massachusetts Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "John Quincy Adams". The White House. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Hogan, Margaret A. (October 4, 2016). "John Quincy Adams: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "HLS's first alumnus elected as President—Rutherford B. Hayes". Harvard Law Today. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Theodore Roosevelt - Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (October 4, 2016). "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Selverstone, Marc J. (October 4, 2016). "John F. Kennedy: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Ellen Johnson Sirleaf - Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ L. Gregg II, Gary (October 4, 2016). "George W. Bush: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Press release: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020". nobelprize.org. Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ "Barack Obama: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. October 4, 2016. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Barack H. Obama - Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Sarah (September 24, 2010). "'Social Network' taps other campuses for Harvard role". Boston.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

'In the grammar of film, Harvard has come to mean both tradition, and a certain amount of stuffiness.... Someone from Missouri who has never lived in Boston ... can get this idea that it's all trust fund babies and ivy-covered walls.'

- ^ King, Michael (2002). Wrestling with the Angel. p. 371.

...praised as an iconic chronicle of his generation and his WASP-ish class.

- ^ Halberstam, Michael J. (February 18, 1953). "White Shoe and Weak Will". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015.

The book is written slickly, but without distinction.... The book will be quick, enjoyable reading for all Harvard men.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (December 23, 2009). "Second Reading". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015.

'...a balanced and impressive novel...' [is] a judgment with which I [agree].

- ^ Du Bois, William (February 1, 1953). "Out of a Jitter-and-Fritter World". The New York Times. p. BR5.

exhibits Mr. Phillips' talent at its finest

- ^ "John Phillips, The Second Happiest Day". Southwest Review. Vol. 38. p. 267.

So when the critics say the author of "The Second Happiest Day" is a new Fitzgerald, we think they may be right.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Nathaniel L. (September 21, 1999). "University, Hollywood Relationship Not Always a 'Love Story'". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on September 10, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Sarah Thomas (September 24, 2010). "'Social Network' taps other campuses for Harvard role". boston.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Never Having To Say You're Sorry for 25 Years..." Harvard Crimson. June 3, 1996. Archived from the original on July 17, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (August 20, 2010). "The Disease: Fatal. The Treatment: Mockery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Gewertz, Ken (February 8, 1996). "A Many-Splendored 'Love Story'. Movie filmed at Harvard 25 years ago helped to define a generation". Harvard University Gazette.

- ^ Walsh, Colleen (October 2, 2012). "The Paper Chase at 40". Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

서지학

- 아벨만, 월터 H., 에드 하버드-MIT 보건 과학 기술 부서: 첫 25년, 1970-1995 (2004). 346pp.

- 비처, 헨리 K. 그리고 앨트슐, 마크 D. 하버드 대학교 의학부: 첫 300년 (1977). 569pp.

- 벤팅크-스미스, 윌리엄, 에드. 하버드 책: 삼세기로부터의 선택 (1982년 2판). 499pp.

- 베델, 존 T; Hunt, Richard M; 그리고 Shenton, Robert. 하버드 A에서 Z까지 (2004). 396 pp. 발췌 및 텍스트 검색

- 베델, 존 T. 하버드에서 관측된 것: 20세기 대학의 역사, 하버드 대학교 출판부, 1998, ISBN 0-674-37733-8

- 번팅, 베인브리지. 하버드: 건축사 (1985) 350pp.

- 카펜터, 케네스 E. 하버드 대학 도서관의 첫 350년: 전시회에 대한 설명(1986). 216pp.

- 쿠노, 제임스 외. 하버드 미술관: 수집 100년 (1996). 364pp.

- 엘리엇, 클라크 A. 로시터, 마가렛 W. 에드스. 하버드 대학교의 과학: 역사적 관점 (1992). 380pp.

- 홀, 맥스 하버드 대학 출판부: 역사 (1986). 257pp.

- 헤이, 아이다. 즐거움의 땅에서의 과학: 아놀드 수목원의 역사 (1995). 349pp.

- 허, 존, 우린 프레스티지를 먹을 수 없어요. 하버드를 조직한 여성들, 템플 대학교 출판부, 1997, ISBN 1-56639-535-6

- 안녕, 도로시 엘리아. 기념해야 할 세기: 래드클리프 대학, 1879-1979 (1978). 152pp.

- 켈러, 모튼 그리고 필리스 켈러. 하버드 현대화: The Rise of America's University (2001), 주요 역사는 1933년부터 2002년까지 온라인판에 수록, 2012년 7월 2일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨

- 루이스, 해리 R. 영혼 없는 탁월함: 위대한 대학이 어떻게 교육을 잊었는가 (2006) ISBN 1-58648-393-5

- 모리슨, 새뮤얼 엘리엇. 하버드 3세기, 1636–1936 (1986) 512pp; 발췌 및 텍스트 검색

- 파월, 아서 G. 불확실한 직업: 하버드와 교육 당국을 찾아서(1980). 341pp.

- 리드, 로버트 첫 해: 하버드 경영대학원 내부의 친밀한 모습 (1994). 331pp.

- 로솝스키, 헨리. 더 유니버시티: 사용자 설명서(1991). 312pp.

- 로솝스키, 니차. 하버드와 래드클리프에서의 유대인 경험 (1986). 108pp.

- 셀리그먼, 조엘. 하이 시타델: 하버드 로스쿨의 영향(1978). 262pp.

- 솔러스, 베르너, 티트콤, 콜드웰, 언더우드, 토마스 A. 에드스. 하버드의 흑인: 하버드와 래드클리프에서의 아프리카계 미국인 경험에 대한 다큐멘터리 역사(1993). 548pp.

- 트럼프버, 존, 에드, 하바드 룰즈. 보스턴, 제국의 봉사에 있어서의 이유: 사우스엔드프레스, 1989, ISBN 0-89608-283-0

- 울리히, 로렐 대처, 에드., 야드와 게이츠: 하버드와 래드클리프 역사의 성별, 뉴욕: 팔그레이브 맥밀런, 2004. 337쪽.

- 윈저, 메리 P. 자연의 모양 읽기: 아가시즈 박물관의 비교 동물학 (1991). 324 pp.

- 라이트, 콘래드 에디크. 레볼루션 제너레이션: 하버드 맨과 독립의 결과 (2005). 298pp.

외부 링크

- 공식 홈페이지

- 미국 국립교육통계센터(National Center for Education Statistics)의 도구인 College Navigator의 하버드 대학교

![2nd President of the United States John Adams (AB, 1755; AM, 1758)[127]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/US_Navy_031029-N-6236G-001_A_painting_of_President_John_Adams_%281735-1826%29%2C_2nd_president_of_the_United_States%2C_by_Asher_B._Durand_%281767-1845%29-crop.jpg/95px-US_Navy_031029-N-6236G-001_A_painting_of_President_John_Adams_%281735-1826%29%2C_2nd_president_of_the_United_States%2C_by_Asher_B._Durand_%281767-1845%29-crop.jpg)

![6th President of the United States John Quincy Adams (AB, 1787; AM, 1790)[128][129]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/John_Quincy_Adams.jpg/98px-John_Quincy_Adams.jpg)

![19th President of the United States Rutherford B. Hayes (LLB, 1845)[130]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/President_Rutherford_Hayes_1870_-_1880_Restored.jpg/99px-President_Rutherford_Hayes_1870_-_1880_Restored.jpg)

![26th President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Theodore Roosevelt (AB, 1880)[131]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/President_Theodore_Roosevelt%2C_1904.jpg/91px-President_Theodore_Roosevelt%2C_1904.jpg)

![32nd President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt (AB, 1903)[132]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/FRoosevelt.png/96px-FRoosevelt.png)

![35th President of the United States John F. Kennedy (AB, 1940)[133]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/John_F._Kennedy%2C_White_House_color_photo_portrait.jpg/92px-John_F._Kennedy%2C_White_House_color_photo_portrait.jpg)

![24th President of Liberia and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (MPA, 1971)[134]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/Ellen_Johnson-Sirleaf%2C_April_2010.jpg/90px-Ellen_Johnson-Sirleaf%2C_April_2010.jpg)

![43rd President of the United States George W. Bush (MBA, 1975)[135]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/George-W-Bush.jpeg/91px-George-W-Bush.jpeg)

![Founder of Microsoft and philanthropist Bill Gates (College, 1977;[a 1] LLD hc, 2007)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Bill_Gates_June_2015.jpg/85px-Bill_Gates_June_2015.jpg)

![Biochemist and Nobel laureate in chemistry Jennifer Doudna (PhD, 1989)[136]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Professor_Jennifer_Doudna_ForMemRS.jpg/80px-Professor_Jennifer_Doudna_ForMemRS.jpg)

![44th President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Barack Obama (JD, 1991)[137][138]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/President_Barack_Obama.jpg/96px-President_Barack_Obama.jpg)

![Founder of Facebook Mark Zuckerberg (College, 2004;[a 1] LLD hc, 2017)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/Mark_Zuckerberg_F8_2019_Keynote_%2832830578717%29_%28cropped%29.jpg/96px-Mark_Zuckerberg_F8_2019_Keynote_%2832830578717%29_%28cropped%29.jpg)