잽이츠

Jats| 인구가 많은 지역 | |

|---|---|

| 남아시아 | ~3,300만명 (2009/10년)c. |

| 언어들 | |

| 힌두스타니어 (힌디-우르두어) • 하리안비어 • 펀자브어 (및 그 방언) • 란다어 • 라자스타니어 • 신디어 (및 그 방언) • 브라지어 • 카리볼리어 | |

| 종교 | |

| 힌두교 • 이슬람교 • 시크교 | |

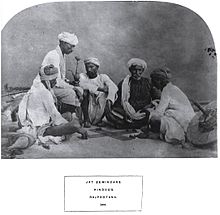

자트족 (푼자비:ਜੱਟ, 힌두어: जाट어, ͡ʒ어: ːʈ어: جاٽ어, 신디: ͡ʒəʈːᵊ)는 북인도와 파키스탄의 전통적인 농업 공동체입니다.원래 신드의 인더스 강 하류 계곡의 목축민이었던 자츠는 중세 후기에 펀자브 지역으로 북쪽으로 이주했고, 그 후 17세기와 18세기에 델리 준주, 북동부 라즈푸타나, 서부 갠지틱 평원으로 이주했습니다.[7][8][9]힌두교, 이슬람교, 시크교의 신앙들 중에서, 그것들은 현재 인도의 펀자브, 하리아나, 우타르프라데시, 라자스탄 주와 파키스탄의 신드와 펀자브 주에서 주로 발견됩니다.

자츠족은 17세기 말과 18세기 초에 무굴 제국에 대항하여 무기를 들었습니다.[10]힌두 자트족 지주인 고쿨라는 아우랑제브의 시대에 무굴 통치에 반대한 초기 반군 지도자 중 한 명이었습니다.[11]힌두 자트 왕국은 마하라자 수라즈 말 (1707–1763) 치하에서 절정에 이르렀습니다.[12]그 공동체는 시크교의 무술 칼사 판트의 발전에 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[13]20세기에 이르러 토지를 소유한 자츠는 펀자브,[14] 서부 우타르 프라데시,[15] 라자스탄,[16] 하리아나, 델리 등 북인도의 여러 지역에서 영향력 있는 집단이 되었습니다.[17]수년에 걸쳐, 몇몇 자츠는 도시의 일자리를 위해 농업을 포기했고, 더 높은 사회적 지위를 주장하기 위해 그들의 지배적인 경제적, 정치적 지위를 이용했습니다.[18]

역사

Jats는 초기 근대 인도 아대륙에서 공동체와 정체성 형성의 패러다임적인 예입니다.[7]"Jat"은 단순한 토지 소유의 소작농부터 부유하고 영향력 있는 자민다르에 이르기까지 다양한 공동체에[19][20] 적용되는 탄력적인 라벨입니다.[24][25][26][27][28]

무함마드 빈 카심이 신드를 정복한 8세기 무렵, 아랍 작가들은 신드를 정복한 땅의 건조한 지역, 습한 지역, 산악 지역의 자트의 응집을 묘사했습니다.[29]아랍의 통치자들은 신학적으로 평등주의적인 종교를 표방했지만, 신드의 힌두 통치의 오랜 기간 동안 자리잡았던 자츠의 입장과 그들에 대한 차별적인 관행을 유지했습니다.[30]11세기에서 16세기 사이에 신드의 재더들은 강 계곡을 따라 [31]펀자브로 이주했는데,[7] 펀자브 지역은 첫 천년에 거의 경작되지 않았을 것입니다.[32]많은 사람들이 최근 사키아 (물레방아)가 소개된 서부 펀자브와 같은 지역에서 경작을 시작했습니다.[7][33]무굴 시대 초기, 펀자브에서는 "자트"라는 용어가 "농부"와 느슨하게 동의어가 되었고,[34] 일부 자트족들은 토지를 소유하고 지역적인 영향력을 행사하게 되었습니다.[7]자츠족은 인더스 계곡의 목축주의에 기원을 두었고, 점차 농업주의 농부가 되었습니다.[35]1595년경, 자트 자민다르스는 펀자브 지역의 자민다르스의 32% 이상을 지배했습니다.[36]

역사학자 캐서린 애셔와 신시아 탈보트에 의하면,[37]

자츠족은 또한 식민지 이전 시대에 종교적 정체성이 어떻게 발전했는지에 대한 중요한 통찰력을 제공합니다.그들이 펀자브와 다른 북부 지역에 정착하기 전에, 목회자 자츠는 주류 종교에 거의 노출되지 않았습니다.그들이 농경사회에 더 통합된 후에야 자트족은 그들이 거주하는 사람들의 지배적인 종교를 채택했습니다.[37]

시간이 지나면서 자트족은 주로 서부 펀자브 지역의 이슬람교도, 동부 펀자브 지역의 시크교도, 델리 영토와 아그라 사이의 지역의 힌두교도가 되었고, 신앙에 의한 분열은 이러한 종교들의 지리적 강점을 반영했습니다.[37]18세기 초 무굴 통치가 쇠퇴하는 동안, 인도 아대륙의 배후지 거주자들은 무장하고 유목민들이었고, 정착한 마을 사람들과 농업인들과 점점 더 교류했습니다.18세기의 많은 새로운 통치자들은 그러한 무술적이고 유목적인 배경에서 왔습니다.이러한 상호작용이 인도의 사회조직에 미친 영향은 식민지 시대까지 잘 지속되었습니다.이 시기의 대부분 동안, Jats나 Ahirs와 같은 비엘리트 경작자들과 목축가들은 한쪽에서는 엘리트 토지 소유 계급들, 그리고 다른 쪽에서는 비엘리트 계급들과 불분명하게 섞인 사회적 스펙트럼의 일부였습니다.[38]무굴 통치의 전성기 동안 자츠는 권리를 인정했습니다.바바라 D에 의하면. 메트카프와 토마스 R. Metcarf:

신생 전사, 마라타, 자츠 등은 군사적, 통치적 이상을 가진 일관된 사회집단으로서 그 자체로 그들을 인정하고 그들에게 군사적, 통치적 경험을 제공한 무굴 맥락의 산물이었습니다.그들의 성공은 무굴 성공의 한 부분이었습니다.[39]

무굴 제국이 무너지면서 북인도에서는 농촌 반란이 잇따랐습니다.[40]비록 이것들이 때때로 "농부의 반란"으로 특징지어지기도 했지만, 무자파르 알람과 같은 다른 사람들은 작은 지역 지주들, 즉 제민다르들이 종종 이러한 반란을 주도했다고 지적했습니다.[40]시크교도와 자트교도의 반란은 서로 긴밀한 관계와 가족 관계를 맺고 있었고, 종종 무장을 한 소규모 지역 제민다르들에 의해 주도되었습니다.[41]

떠오르는 농민 전사들의 이 공동체들은 잘 설립된 인디언 카스트들이 아니라,[42] 고정된 신분 범주가 없고, 정착된 농업의 변두리에 있는 오래된 농민 카스트들, 잡종 군벌들, 유목민 집단들을 흡수할 수 있는 능력이 있는 꽤 새로운 것이었습니다.[41][43]무굴 제국은 권력의 정점에서도 권력을 이양하는 기능을 했으며, 시골의 대지주들에 대한 직접적인 통제권을 가진 적이 없었습니다.[41]이런 반란들로부터 가장 많은 것을 얻어서, 그들이 통제할 수 있는 땅을 늘린 사람들이 바로 이 제민다르들이었습니다.[41]그 승리자들은 심지어 바라트푸르의 자트족 통치자 바단 싱과 같은 작은 왕자들의 계급까지 얻었습니다.[41]

힌두자츠

1669년, 고쿨라의 지도하에 힌두 자트족이 마투라에서 무굴 황제 아우랑제브에게 반란을 일으켰습니다.[44]그 공동체는 1710년 이후 델리의 남쪽과 동쪽을 지배하게 되었습니다.[45]역사학자 크리스토퍼 베일리에 의하면

18세기 초 무굴의 기록에 따르면, 세기 말까지 제국의 통신선을 이용한 약탈자와 도적으로 특징지어지는 남성들은 결혼 동맹과 종교적 실천과 관련된 다양한 작은 국가들을 낳았습니다.[45]

자츠족은 각각 17세기와 18세기에 두 번의 대규모 이주를 통해 갠지틱 평원으로 이주했습니다.[45]그들은 예를 들어, 동부 갠지스 강 평원의 푸미하르들이 그랬던 것처럼, 일반적인 힌두 의미의 카스트가 아니었습니다. 오히려 그들은 농민 전사들의 우산 집단이었습니다.[45]크리스토퍼 베이리에 의하면:

이 사회는 브라만이 소수였고 남성 Jats가 하위 농업 및 기업가 계급 전체로 결혼한 사회였습니다.일종의 부족 민족주의는 브라만 힌두 국가의 맥락 안에서 표현된 카스트 차이에 대한 멋진 계산보다는 그들을 활기차게 만들었습니다.[45]

18세기 중반, 바라트푸르의 최근 세워진 자트 왕국의 통치자 라자 수라즈말은 디그 근처에 정원 궁전을 지을 수 있을 정도로 내구성에 대해 낙관적이었습니다.[46]역사학자 에릭 스톡스에 의하면

바라트푸르 라자의 세력이 승승장구할 때, 자츠의 전투적인 씨족들은 카르날/파니파트, 마투라, 아그라, 그리고 알리가르 지역을 잠식했는데, 대개 라즈푸트 집단의 희생이었습니다.그러나 그러한 정치적 우산은 상당한 이동이 효과를 발휘하기에는 너무 취약하고 수명이 짧았습니다.[47]

무슬림 자츠

아랍인들이 7세기에 신드와 현재 파키스탄의 다른 남부 지역에 들어 왔을 때, 그들이 발견한 주요 부족 집단은 자트족과 메드족이었습니다.이 자트들은 초기 아랍 문헌에서 종종 자트라고 불립니다.무슬림 정복기는 신드강 하류와 중부의 마을과 요새에 있는 자트족의 중요한 밀집 지역을 더욱 가리키고 있습니다.[48][49]오늘날, 무슬림 자트는 파키스탄과 인도에서 발견됩니다.[50]

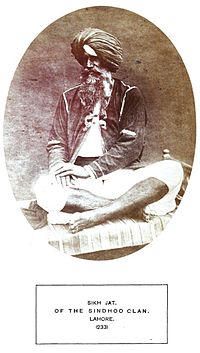

시크자츠

바바 부처와 같은 시크교 전통에 중요한 추종자들이 초기의 중요한 역사적 시크교 인물들 중 하나였고, 구루 앙가드 (1504–1552) 시대에 이미 상당한 수의 개종이 일어났지만,[51] 자츠의 첫 번째 대규모 개종은 구루 아르잔 (1563–1606) 시대에 일반적으로 시작되었습니다.[51][52]: 265 펀자브 동부의 시골 지역을 여행하는 동안, 그는 타른 타란 사히브, 카르타르푸르, 하르고빈드푸르와 같은 사회적, 경제적 중심지 역할을 했던 몇몇 중요한 마을들을 설립했고, 구루 그란트 사히브를 수용하기 위한 다르바르 사히브의 지역 사회 자금 지원 완공과 함께 시크교 활동의 집결지와 중심지 역할을 하였습니다.특히 이 지역의 자트족 농민들로 넘쳐났던, 자립적인 시크교 공동체의 시작을 알렸습니다.[51]그들은 18세기부터 무굴 제국에 대항하는 시크교도 저항의 선봉대를 형성했습니다.

결론적으로 구루 아르잔(구루 하르고빈 시대에 시작하여 이후에도 계속됨)의 순교 이후 시크교도의 증가된 군사화와 그것의 거대한 자트의 존재가 상호적으로 영향을 미쳤을 것이라고 가정되어 왔습니다.[53][full citation needed][54]

12개의 시크교도들 중 적어도 8개의 시크교도들은 자트 시크교도들이 이끌었고, [55]그들은 시크교도 수장들의 대다수를 형성했습니다.[56]

20세기 초 식민지 기간 동안 발행된 가제트의 인구조사에 따르면, 힌두교에서 시크교로 이어지는 자트 개종의 추가적인 물결이 지난 수십 년 동안 계속되었습니다.[57][58]시크교도 작가 쿠슈완트 싱은 펀자브의 자츠에 대해 쓰면서 그들의 태도가 결코 브라만어에 몰두하는 것을 허용하지 않는다고 말했습니다.[59][60]영국인들은 힌두교도들이 그들의 군대를 위해 더 많은 수의 시크교 신병을 확보하기 위해 시크교로 개종하도록 장려함으로써 시크교 인구의 증가에 중요한 역할을 했습니다.[61][62]

펀자브에서는 파티알라 주,[63] 파리드코트 주, 진드 주, 나바[64] 주가 시크자츠 주에 의해 통치되었습니다.

인구통계학

인류학자 선일 K에 의하면.2010년 남아시아에서 칸나, 자트의 인구는 약 3천만 명으로 추정됩니다.이 추정치는 지난 카스트 인구조사 통계와 그 지역의 인구증가에 근거한 것입니다.1931년에 마지막 카스트 인구조사가 실시되었는데, Jats는 인도와 파키스탄에 주로 집중되어 있는 8백만 명으로 추정되었습니다.[65]데릭 O.Lodrick은 2009년 남아시아의 Jat 인구가 3,300만 명(인도와 파키스탄의 경우 각각 약 1,200만 명과 2,100만 명 이상) 이상이 될 것으로 추정하고 있으며, 이와 관련하여 정확한 통계를 사용할 수 없다는 점에 주목하고 있습니다.그의 추정은 1980년대 후반 Jats의 인구 예측과 인도와 파키스탄의 인구 증가에 근거하고 있습니다.그는 또한 일부 추산에 따르면 2009년 남아시아의 총 인구는 약 4천 3백만 명에 달한다고 합니다.

인도 공화국

인도에서는 21세기에 여러 차례 추정한 결과, 자츠의 인구 점유율은 하리아나 주에서 20-25%, 펀자브 주에서 20-35%로 나타났습니다.[67][68][69]라자스탄, 델리, 우타르프라데시 주에서는 전체 인구의 약 9%, 5%, 1.2%를 차지합니다.[70][71][72]

20세기와 더 최근에는, 자츠가 하리아나와[73] 펀자브의 정치 계급으로서 지배적이었습니다.[74]제6대 인도 총리 차란 싱과[75] 제6대 인도 부총리 차우드리 데비 랄을 포함한 일부 자트족은 주목할 만한 정치 지도자가 되었습니다.[76]

경제적 이익의 공고화와 선거 과정에서의 참여는 독립 이후 상황의 두 가지 가시적 결과입니다.이 참여를 통해 그들은 북인도의 정치에 상당한 영향을 미칠 수 있었습니다.경제적인 차별화, 이주, 이동성은 Jat족 사이에서 분명히 눈에 띄었습니다.[77]

인도의 36개 주와 UT 중 7개 주, 즉 라자스탄, 히마찰 프라데시, 델리, 우타라칸드, 우타르 프라데시, 마디아 프라데시, 그리고 차티스가르에서 Jats는 OBC(Other Backward Class)로 분류됩니다.[78]그러나 바라트푸르 지역과 돌푸르 지역을 제외한 라자스탄의 자트족만이 OBC 보호 구역에 따라 중앙 정부 일자리를 예약할 수 있습니다.[79]2016년 하리아나의 자츠족은 이러한 적극적인 행동 이익을 얻기 위해 OBC로 분류할 것을 요구하는 대규모 시위를 조직했습니다.[78]

파키스탄

많은 자트 이슬람교도들이 파키스탄에 살고 있으며, 파키스탄 펀자브와 파키스탄의 일반적인 공공 생활에서 지배적인 역할을 하고 있습니다.파키스탄령 카슈미르, 신드, 특히 인더스 삼각주와 파키스탄 펀자브 남부의 세라이키어권 공동체, 발로치스탄의 카치 지역, 노스웨스트프런티어 주의 데라 이스마일 칸 지구에도 자트 공동체가 존재합니다.

파키스탄에서도, 자트족은 히나 랍바니 카르와 같은 주목할 만한 정치 지도자가 되었습니다.[80]

문화와 사회

군사의

많은 Jat 사람들은 Jat 연대, Sikh 연대, Rajputana Rifles 및 Grenadiers를 포함하여 인도 군대에서 복무합니다. 그들은 용맹과 용기로 많은 최고의 군사 상을 수상했습니다.자트족은 파키스탄군, 특히 펀자브 연대에서 복무합니다.[81]

자트족은 영국령 인도 제국의 관리들에 의해 "무전민족"으로 지정되었는데, 이는 그들이 영국령 인도군의 징집을 선호하는 집단 중 하나라는 것을 의미했습니다.[82][83]이것은 각 민족을 "군사적" 또는 "비군사적"으로 분류한 행정가들에 의해 만들어진 명칭이었습니다: "군사적 인종"은 일반적으로 전투를 위해 용감하고 잘 만들어졌다고 생각되는 반면,[84] 나머지는 영국인들이 그들의 좌식 생활 방식 때문에 전투에 적합하지 않다고 믿었던 사람들이었습니다.[85]그러나, 그 무술 경기들은 또한 정치적으로 종속적이고, 지적으로 열등하며, 대규모 군사 조직을 지휘할 주도권이나 지도력이 부족하다고 여겨졌습니다.영국인들은 통제하기 쉽기 때문에 교육에 접근성이 떨어지는 사람들로부터 무술 인도인들을 모집하는 정책을 가지고 있었습니다.[86][87]군사 역사에 관한 현대 역사학자 제프리 그린헌트(Jeffrey Greenhunt)에 따르면, "무술 경기 이론은 우아한 대칭을 가졌습니다.지적이고 교육을 받은 인도인들은 겁쟁이로 규정되었고, 용감한 사람들은 교육을 받지 못했고 후진적이었습니다."아미야 사만타에 따르면, 이 무술 종족은 용병 정신(자신에게 돈을 지불할 어떤 집단이나 국가를 위해 싸우는 군인)을 가진 사람들 중에서 선택되었다고 합니다. 왜냐하면 이 집단들은 민족주의가 특성으로 부족했기 때문입니다.[88]자츠족은 제1차 세계 대전과 제2차 세계 대전에 모두 영국 인도 육군의 일원으로 참전했습니다.[89]영국이 이전의 반시크 정책을 뒤집었던 1881년 이후의 시기에, 행정부는 힌두교도들이 군사적 목적으로 열등하다고 믿었기 때문에 군대에 징집되기 위해서는 시크교를 공언할 필요가 있었습니다.[90]

인도 육군은 2013년 150명의 대통령 경호원이 힌두 자트족, 자트 시크교도, 힌두 라지푸트족으로만 구성되어 있다고 인정했습니다.차별 주장을 반박하면서 이는 카스트나 종교에 따른 선택이라기보다는 '기능적'인 이유 때문이라고 밝혔습니다.[91]

종교적 신념

데릭 O.Lodrick은 Jats의 종교적인 분열을 다음과 같이 추정합니다: 힌두교 47%, 이슬람교 33%, 시크교 20%.[66]

잽이들은 죽은 조상들에게 기도하는데, 이것을 자테라라고 합니다.[92]

바르나유무

힌두교에서 자츠의 바르나적 지위에 대해서는 학계의 견해가 엇갈리고 있습니다.역사학자 사티쉬 찬드라(Satish Chandra)는 중세 시대 자츠의 바르나를 "양가적"이라고 묘사합니다.[93]역사학자 이르판 하비브(Irfan Habib)는 자츠족이 8세기 신드(Sindh)의 "목사적인 찬달라(Chandala) 같은 부족"이었다고 말합니다.그들의 11세기 슈드라 바르나의 지위는 17세기에 이르러 바이샤 바르나로 바뀌었고, 그들 중 일부는 무굴족에 대항한 17세기 반란 이후에 그것을 더 개선하고자 열망했습니다.그는 Al-Biruni와 Dabestan-e Mazaheb을 인용하여 각각 슈드라와 바시야 바르나의 주장을 지지합니다.[94]

라지푸트인들은 영국 라지의 말년 동안 크샤트리야 지위에 대한 자트의 주장을 받아들이기를 거부했고 이러한 의견 불일치는 두 공동체 사이에 종종 폭력적인 사건을 야기했습니다.[95]크샤트리야 지위 당시의 주장은 자트족 사회에서 인기를 끌었던 아리아 사마즈에 의해 제기되고 있었습니다.아리아 사마즈는 자트족이 아리아 혈통이 아니라 인도-스키티아 혈통이라는 식민지 믿음에 대항하기 위한 수단이라고 보았습니다.[96]

여성 영아살해와 여성의 사회적 지위

식민지 기간 동안, 힌두 자츠를 포함한 많은 공동체들이 북인도의 다른 지역에서 여성 영아살해를 실행하고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[97][98]

자트 사회에서는 남성에 비해 여성에게 차별적인 대우를 하는 것이 관찰되어 왔습니다.한 가정에서 남자 아이의 탄생을 축하하고 경사스럽게 여기는 반면, 여자 아이의 탄생에 대한 반응은 더 가라앉습니다.마을에서는 여성 구성원들이 좀 더 어린 나이에 결혼을 하게 되어 있고 남성 구성원들보다 종속적인 분야에서 일할 것으로 기대됩니다.비록 도시화에 따라 추세가 변하고 있지만, 사회에서 여성 아이들에 대한 교육에 대한 일반적인 편견이 있습니다.푸르다 제도는 자트 마을의 여성들에 의해 행해지고 있으며, 이는 그들의 전체적인 해방에 방해가 되고 있습니다.남성이 지배적인 자트 마을 의회는 여성이 열등하고 능력이 없으며 남성에 비해 지능이 떨어진다는 공통된 의견으로 여성 의원이 의회 의장을 맡는 것을 대부분 허용하지 않습니다.[99]

씨족제

자트족은 수많은 씨족으로 세분화되어 있으며, 그 중 일부는 로르족,[100] [101]아레인족, 라즈푸트족[102] 및 기타 집단과 겹칩니다.[103]힌두교와 시크자츠는 종족 외혼을 행합니다.

씨족 목록

대중문화에서

잽은 펀자브와 하리아니 문화의 일부이며 인도와 파키스탄 영화와 노래에서 종종 묘사됩니다.

주목할 만한 사람들

참고 항목

각주

- ^ "용어: ary트: 북인도의 주요한 비 엘리트 '농부' 카스트의 칭호."

- ^ "... 19세기 중반에 인도의 농업 지역에는 두 가지 대조적인 경향이 있었습니다.이전의 변방 지역들은 새로운 수익성이 있는 '농부' 농업의 지역으로 도약하여 서부 NWP의 자트와 코이마토레의 가우더와 같은 칭호로 알려진 비 엘리트 경작 집단들에게 불이익을 주었습니다."[5]

- ^ "19세기 후반, 이러한 생각은 식민지 관리들이 소위 토지 소외라는 법률 하에서 입법을 옹호함으로써 시크 자츠와 그들이 현재 군대 신병으로 선호하는 다른 비 엘리트 '농부'들을 보호하려고 노력하게 만들었습니다."[6]

- ^ "용어: ary트: 북인도의 주요한 비 엘리트 '농부' 카스트의 칭호."

- ^ "... 19세기 중반에 인도의 농업 지역에는 두 가지 대조적인 경향이 있었습니다.이전의 변방 지역은 새로운 수익성이 있는 토지 소유 농업의 지역으로 도약하여 서부 NWP의 자트와 코이마토레의 가우더와 같은 칭호로 알려진 비 엘리트 경작 집단에게 불이익을 주었습니다."[5]

- ^ "19세기 후반, 이러한 생각은 식민지 관리들이 소위 토지 소외라는 법률 하에서 입법을 옹호함으로써 시크 자츠와 그들이 현재 군대 신병으로 선호하는 다른 비 엘리트 '농부'들을 보호하려고 노력하게 만들었습니다."[6]

- ^ 수잔 베일리에 따르면, "... (북인도)에는 엘리트가 아닌 많은 경작자들이 있었습니다.펀자브와 서부 갠지틱 평원에서는 관례에 따라 라즈푸트족의 비엘리트족 상대를 자트족으로 규정했습니다.다른 곳에서 사용되는 많은 유사한 칭호들처럼, 이것은 카스트 이름이라기 보다는 시골 지역의 실질적인 사람에 대한 광범위한 명칭이었습니다.… 일부 지역에서 j이라고 불리는 것은 목회의 배경을 암시했지만, 그것은 더 일반적으로 비종속적인 사람들을 길러내는 것을 의미합니다."

참고문헌

- ^ Khanna, Sunil K. (2004). "Jat". In Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology: Health and Illness in the World's Cultures. Vol. 2. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 777. ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6.

Notwithstanding social, linguistic, and religious diversity, the Jats are one of the major landowning agriculturalist communities in South Asia.

- ^ Nesbitt, Eleanor (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

Jat: Sikhs' largest zat, a hereditary land-owning community

- ^ Gould, Harold A. (2006) [2005]. "Glossary". Sikhs, Swamis, Students and Spies: The India Lobby in the United States, 1900–1946. SAGE Publications. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-7619-3480-6.

Jat: name of large agricultural caste centered in the undivided Punjab and western Uttar Pradesh

- ^ a b Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ a b Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ a b Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ Khazanov, Anatoly M.; Wink, Andre (2012), Nomads in the Sedentary World, Routledge, p. 177, ISBN 978-1-136-12194-4, retrieved 15 August 2013 인용문: "호은창은 7세기 신티(신)의 수많은 유목민들에 대한 다음과 같은 설명을 했습니다. '강변에..[신드의] 평지의 습지 저지대를 따라 수천 리에 달하는 [아주 많은] 가족들이 있습니다.그들은 소를 보살피는 일에만 전념하며, 그들의 생계를 이룩한 것입니다.그들에게는 주인이 없고, 남자든 여자든 부유하지도 가난하지도 않습니다.'중국인 순례자들에 의해 이름이 알려지지 않은 채로 남아있는 동안, 신드강 하류의 이 같은 사람들은 아랍 지리학자들에 의해 '야츠' 또는 '폐기물의 야츠'라고 불렸습니다.자츠족은 '단신'으로서 당시 주요 목회-유목민 분파 중 하나였으며, 수많은 분파가 존재했습니다.

- ^ Wink, André (2004), Indo-Islamic society: 14th – 15th centuries, BRILL, pp. 92–93, ISBN 978-90-04-13561-1, retrieved 15 August 2013 인용문: "신드에서는 양과 버팔로의 번식과 방목이 남부 저지대 유목민들의 정규적인 직업이었고, 키르타르 산맥 바로 동쪽과 물탄과 만수라 사이의 지역에서는 염소와 낙타의 번식이 지배적인 활동이었습니다.자트족은 중세 초기에 이곳의 주요 목축민-유목민 분파 중 하나였으며, 이들 중 일부는 이라크까지 이주했지만, 일반적으로 정기적으로 아주 먼 거리를 이동하지는 않았습니다.많은 재트들이 북쪽으로, 판잡으로 이주했고, 11세기와 16세기 사이에, 한때 대부분 목축민이었던 재트족은 정착한 소작농으로 바뀌었습니다.몇몇 자트족은 판잡의 다섯 강 사이에 있는 인구가 적은 술집 나라에서 염소와 낙타의 목축을 바탕으로 일종의 트랜스휴먼을 채택하며 계속 살았습니다.재츠에게 일어난 일은 그들이 점점 더 확대되는 농업 영역에 의해 폐쇄되었다는 점에서 인도의 다른 대부분의 목축민 및 목축민 유목민들의 패러다임인 것 같습니다."

- ^ Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher; Cynthia Talbot (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7.

- ^ R.C. Majumdar, H.C. Raychaudhari, Kalikinkar Data:선진 인도사, 2006, p.490

- ^ The Gazetteer of India: History and culture. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, India. 1973. p. 348. OCLC 186583361.

- ^ Karine Schomer and W. H. McLeod, ed. (1987). The Sants: studies in a devotional tradition of India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 242. ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3.

- ^ Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas (1962). Caste in modern India: and other essays. Asia Pub. House. p. 90. OCLC 185987598.

- ^ Sheel Chand Nuna (1 January 1989). Spatial fragmentation of political behaviour in India: a geographical perspective on parliamentary elections. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-81-7022-285-9. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ Lloyd I. Rudolph; Susanne Hoeber Rudolph (1984). The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India. University of Chicago Press. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-226-73137-7. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ Carol R. Ember; Melvin Ember, eds. (2004). Encyclopedia of medical anthropology. Springer. p. 778. ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6.

- ^ Sunil K. Khanna (2009). Fetal/fatal knowledge: new reproductive technologies and family-building strategies in India. Cengage Learning. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-495-09525-5.

- ^ Oldenburg, Veena Talwar (2002). Dowry Murder: The Imperial Origins of a Cultural Crime. Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-19-515071-1.

The Jats, who are numerically dominant in central and eastern Punjab, can be Hindu, Sikh, or Muslim; they range from powerful landowners to poor subsistence farmers, and were recruited in large numbers to serve in the British army.

- ^ Alavi, Seema (2002). The eighteenth century in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-19-565640-7. OCLC 50783542.

The Jat power neat Agra and Mathura arose out of the rebellion of peasants under zamindar leadership, attaining the apex of power under Suraj Mal...it seems to have been an extensive replacement of Rajput by Jat zamindars...and the 'warlike Jats' (a peasant and zamindar caste).

- ^ Judge, Paramjit (2014). Mapping social exclusion in India: caste, religion and borderlands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-107-05609-1. OCLC 880877884.

- ^ Stokes, Eric (1978). The peasant and the Raj: studies in agrarian society and peasant rebellion in colonial India. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-521-29770-7. OCLC 889813954.

n the Ganges Canal Tract of the Muzaffarnagar district where the landowning castes – Tagas , Jats , Rajputs , Sayyids , Sheikhs , Gujars , Borahs

- ^ Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Khan, Zahoor Ali (1997). "ZAMINDARI CASTE CONFIGURATION IN THE PUNJAB, c.1595 — MAPPING THE DATA IN THE". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 58: 336. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44143925.

The number of parganas with Jat zamindaris (Map 2) is surprisingly large and well spread out, though there are none beyond the Jhelum. They appear to be in two blocks, divided by a sparse zone between the Sutlej and the Sarasvati basin. The two blocks, in fact, represent two different segments of the Jats, the western one (Panjab) known as Jat (with short vowel) and the other (Haryanvi) as Jaat (with long vowel).

- ^ Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2016). Migrations in Medieval and Early Colonial India. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-351-55825-9. OCLC 993781016.

Out of the 45 parganas of the sarkars of Delhi, 17 are reported to have Jat Zamindars. Out of these 17 parganas, the Jats are exclusively found in 11, whereas in other 6 they shared Zamindari rights with other communities.

- ^ Dhavan, Purnima (2011). When sparrows became hawks: the making of the Sikh warrior tradition, 1699-1799. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-975655-1. OCLC 695560144.

Muzaffar Alam's study of the akhbarat (news reports) and chronicles of the period demonstrates that Banda and his followers had wide support amongst the Jat zamindars of the Majha, Jalandhar Doab, and the Malwa area. Jat zamindars actively colluded with the rebels, and frustrated the Mughal faujdars or commanders of the area by supplying Banda and his men with grain, horses, arms, and provisions. This evidence suggests that understanding the rebellion as a competition between peasants and feudal lords is an oversimplification, since the groups affiliated with Banda as well as those affiliated with the state included both Zamindars and peasants.

- ^ Alam, Muzaffar (1978). "Sikh Uprisings Under Banda Bahadur 1708-1715". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 39: 509–522. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44139389.

Banda led predominantly the uprisings of the Jat zamindars.It is also to be noted that tha Jats were the dominant zamindar castes in some of the parganas where Banda had support. But Banda's spectacular success and the amazing increase in the strength of his army within a few months*6 does not cohere with the presence of a few Jat zamindaris…we can, however presume that the unidentified zamindars of our sources who rallied behind Banda were the small zamindars (mah'ks) and the Mughal assessees (malguzars). It is not without significance that they are almost invariably described as the zamindars of village (mauza and dehat). These zamindars were largely the Jats who had settled in the region for the last three or four centuries.

- ^ Syan, H.S. (2013). Sikh Militancy in the Seventeenth Century: Religious Violence in Mughal and Early Modern India. I.B. Tauris. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7556-2370-9. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

Guru Nanak's father- in-law, Mula Chonha, works as an administrator for the Jat landlord,Ajita Randawa. If we expand this train of thought and examine other Janamsakhi figures we can detect an interesting pattern…All of Nanak's immediate relatives were professional administrators for local or regional lords, including Jat masters. From this we can infer that Khatris did seem to occupy a position as a professional class and some Jats held the position of being landlords. There was clearly a professional services relationship between high-ranking Khatris and high-ranking Jats, and this seems indicative of the wider socio- economic relationship between Khatris and Jats in medieval Panjab.

- ^ Mayaram, Shail (2003), Against history, against state: counterperspectives from the margins, Columbia University Press, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-231-12730-1, retrieved 12 November 2011

- ^ Jackson, Peter (2003), The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge University Press, p. 15, ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3, retrieved 13 November 2011 인용: "...무슬림 정복자들이 카스트 제도에서 벗어나려는 사람들에게 제공한 해방도 당연하게 여겨질 수 없습니다.… 830년대 후반에 신드의 칼리팔 주지사는 … (이전의 힌두교 요구사항을 계속했다) … 자츠족은, 장래에 문밖에서 걸어 나갈 때, 개와 동행해야 한다고 합니다.이 개가 힌두교와 이슬람교도 모두에게 부정한 동물이라는 사실은 이슬람 정복자들이 낮은 계급의 부족에 대한 현상을 유지하는 것을 쉽게 만들었습니다.즉, 8~9세기 신정권은 힌두 주권 시대의 차별적 규제를 폐지한 것이 아니라 유지한 것입니다(15쪽)."

- ^ Grewal, J. S. (1998), The Sikhs of the Punjab, Cambridge University Press, p. 5, ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0, retrieved 12 November 2011 인용문: "... 펀자브에서 가장 많은 농업 부족은 자트족이었습니다.그들은 신드와 라자스탄에서 강 계곡을 따라 올라와서 구자르족과 라지푸트족을 몰아내고 경작지를 차지했습니다.(5페이지)"

- ^ Ludden, David E. (1999), An agrarian history of South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 117, ISBN 978-0-521-36424-9, retrieved 12 November 2011 인용문: "펀자브 강 상류 지역의 평지는 첫 천년에 농사를 많이 짓지 않은 것 같습니다.… 신드, 물탄 주변, 라자스탄에서 중세 초기의 건농업이 발달했습니다. 여기서부터 자트족 농부들은 2천년 상반기에 펀자브 강 상류 지역과 강가 서부 지역으로 이주한 것으로 보입니다.(117페이지)"

- ^ Ansari, Sarah F. D. (1992). Sufi saints and state power: the pirs of Sind, 1843–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0. Retrieved 30 October 2011. 인용문: "11세기와 16세기 사이에, Jats라고 알려진 유목민 목축가 집단들은 신드에서 북쪽으로 향해 일했고, 농민 농업가로서 판자브에 정착했고, 주로 페르시아 수레바퀴의 도입에 힘입어 판자브 서부의 많은 부분을 식량 작물의 풍부한 생산자로 변화시켰습니다.(27쪽)"

- ^ Mayaram, Shail (2003), Against history, against state: counterperspectives from the margins, Columbia University Press, p. 33, ISBN 978-0-231-12730-1, retrieved 12 November 2011

- ^ Khazanov, Anatoly M.; Wink, Andre (12 October 2012). Nomads in the Sedentary World. doi:10.4324/9780203037201. ISBN 9780203037201.

- ^ Khan, Iftikhar Ahmad (1982). "A Note on Medieval Jatt Immigration in the Punjab". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 43: 347, 349. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44141246.

- ^ a b c Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ Bayly, Susan (2001), Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age, Cambridge University Press, p. 41, ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6, retrieved 1 August 2011

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A concise history of modern India. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b Asher, Catherine; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Asher, Catherine; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A concise history of modern India. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Bayly, C. A. (1988). Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870. CUP Archive. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-31054-3. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Avari, Burjor (2013). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A History of Muslim Power and Presence in the Indian Subcontinent. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-41558-061-8.

- ^ a b c d e Bayly, C. A. (1988). Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870. CUP Archive. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-521-31054-3. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A concise history of modern India. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Stokes, Eric (1980). The Peasant and the Raj: Studies in Agrarian Society and Peasant Rebellion in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press Archive. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-521-29770-7. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind, The Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th-11th Centuries. Vol. 1. Boston: Brill. pp. 154–160. ISBN 9780391041738. OCLC 48837811.

- ^ "Zuṭṭ people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Singha, Bhagata (2001). Canadian Sikhs Through a Century, 1897-1997. Gyan Sagar Publications. p. 418. ISBN 9788176850759. 인용문: "무슬림 자트족의 대부분은 파키스탄에 있고 일부는 인도에도 있습니다."

- ^ a b c Mandair, Arvind-pal Singh (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed (illustrated ed.). London, U.K.: A&C Black. pp. 36–42. ISBN 9781441102317.: 42

- ^ Singh, Jagjit (1981). The Sikh Revolution: A Perspective View. New Delhi: Bahri Publications. ISBN 9788170340416.

- ^ McLeod, W. H. Who is a Sikh?: the problem of Sikh identity.

The Jats have long been distinguished by their martial traditions and by the custom of retaining their hair uncut. The influence of these traditions evidently operated prior to the formal inauguration of the Khalsa.

- ^ 싱 1981, 190쪽, 265쪽.

- ^ Dhavan, Purnima (3 November 2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699–1799. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-19-975655-1.

- ^ Dhavan, Purnima (2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699–1799 (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0199756551. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ 시크교도 사회의 변천 - Ethne K 저 92페이지마렌코 - 가제트는 또한 1911년에 자트 시크교도와 자트 힌두교도의 관계를 묘사합니다 ... 2019년은 자트 힌두교도가 시크교로 개종한 것에 기인합니다.

- ^ R. N. Singh (Ph. D.) 130페이지 - Jat Hindus가 1881년 16843년에서 1911년 2019년까지 감소한 것은 Jat Hindus가 시크교로 개종한 것에 기인함…

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2004). A History of the Sikhs: 1469–1838 (2, illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-19-567308-5. OCLC 438966317.

The Jat's spirit of freedom and equality refused to submit to Brahmanical Hinduism and in its turn drew the censure of the privileged Brahmins ... The upper caste Hindu's denigration of the Jat did not in the least lower the Jat in his own eyes nor elevate the Brahmin or the Kshatriya in the Jat's estimation. On the contrary, he assumed a somewhat condescending attitude towards the Brahmin, whom he considered little more than a soothsayer or a beggar, or the Kshatriya, who disdained earning an honest living and was proud of being a mercenary.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2000). Not a Nice Man to know: The Best of Khushwant Singh. Penguin Books. ISBN 9789351182788.

- ^ Heather Streets (2004). Martial Races : The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857-1914. Manchester University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0719069629.

Others were even more candid about the necessity-and feasibility -of 'creating' Sikhs for the army. One contributor to the Indian Army's Journal of the United Services Institute of India proposed a scheme that would change Hindus to Sikhs for the specific purpose of recruitment. To do this, the Sikh recruiting grounds would be extended and Hindu Jats encouraged to take the pahul (the conversion ritual to martial Sikhism)'. He went on to say that these latter might not be as good stuff as that procurable from the present Sikh centres but they would, if of good physique, compare favourably (as regards field service qualifications) with the weedy specimens sometimes enlisted'. In this officer's view, then, the army could 'encourage' Hindus to become Sikhs simply to increase their overall numbers.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (2015). Harsh V. Pant (ed.). Handbook of Indian Defence Policy. Taylor & Francis. p. 71. ISBN 978-1317380092.

The British policy of recruiting the Sikhs (due to the imperial belief that Sikhism is a martial religion) resulted in the spread of Sikhism among the Jats of undivided Punjab and conversion of the Singhs into the 'Lions of Punjab'.

- ^ Hughes, Julie E. (2013). Animal Kingdoms (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0674074781.

While the rulers of Patiala were Jat Sikhs and not Rajputs, the state was the closest princely territory to Bikaner's northwest.

- ^ Bates, Crispin (2013). Mutiny at the Margins: New Perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857: Volume I: Anticipations and Experiences in the Locality. India: SAGE Publishing. p. 176. ISBN 978-8132115892.

The passage to Delhi, however, lay through the cis–Sutlej states of Patiala, Jind, Nabha and Faridkot, a long chain of Jat Sikh states that had entered into a treaty of alliance with the British as far back as April 1809 to escape incorporation into the kingdom of their illustrious and much more powerful neighbour, 'the lion of Punjab' Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

- ^ Khanna, Sunil K. (2010). Fetal/Fatal Knowledge: New Reproductive Technologies and Family-Building Strategies in India. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 18. ISBN 978-0495095255. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b Lodrick, Deryck O. (2009). "JATS". In Gallagher, Timothy L.; Hobby, Jeneen (eds.). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life. Volume 3: Asia & Oceania (2nd ed.). Gale. pp. 418–419. ISBN 978-1414448916. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Meena, Sohan Lal (October–December 2006). Sharma, Sanjeev Kumar (ed.). "Dynamics of State Politics in India". The Indian Journal of Political Science. International Political Science Association. 67 (4): 712. ISSN 0019-5510. JSTOR 41856253. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Sidhu, Aman; Jaijee, Inderjit Singh (2011). Debt and Death in Rural India: The Punjab Story. SAGE Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-8132106531. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Jodhka, Surinder S. (2003). "Contemporary Punjab: A Brief Introduction". In Gill, Manmohan Singh (ed.). Punjab Society: Perspectives and Challenges. Concept Publishing Company. p. 12. ISBN 978-8180690389. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 69, 281. ISBN 978-1850656708. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Robin, Cyril (2009). "Bihar: The New Stronghold of OBC Politics". In Jaffrelot, Christophe; Kumar, Sanjay (eds.). Rise of the Plebeians?: The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-0415460927. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Kumar, Sanjay (2013). Changing Electoral Politics in Delhi: From Caste to Class. SAGE Publications. p. 43. ISBN 978-8132113744. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Shah, Ghanshyam (2004). Caste and Democratic Politics in India. ISBN 9788178240954.

- ^ "PremiumSale.com Premium Domains". indianmuslims.info. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012.

- ^ "The anti-reservation man". Rediff. 27 November 2003. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ Sukumar Muralidharan (April 2001). "The Jat patriarch". Frontline. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ KL 샤르마:재츠 - 북서인도와 북서인도의 사회경제적 삶과 정치성에 대한 그들의 역할과 기여, Vol.I, 2004년.Vir Singh 편집 14페이지

- ^ a b Saubhadra Chatterji (22 February 2016). "History repeats itself as yet another Central govt faces a Jat stir". Hindustan Times.

- ^ "Rajasthan was first state to extend OBC benefits to Jats in 1999". The Times of India. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar". First Post (India). Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Hina Rabbani Khar was born on 19 November 1977 in Multan, Punjab, Pakistan in a Muslim Jat family.

- ^ Ian Sumner (2001). The Indian Army 1914–1947. London: Osprey. pp. 104–105. ISBN 1-84176-196-6.

- ^ Pati, Budheswar (1996). India And The First World War. Atlantic Publishers. p. 62. ISBN 9788171565818.

- ^ Britten, Thomas A. (1997). American Indians in World War I: At Home and at War (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of New Mexico Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-8263-2090-2.

The Rajputs, Jats, Dogras, Pathans, Gorkhas, and Sikhs, for example, were considered martial races. Consequently, the British labored to ensure that members of the so-called martial castes dominated the ranks of infantry and cavalry and placed them in special "class regiments."

- ^ Rand, Gavin (March 2006). "Martial Races and Imperial Subjects: Violence and Governance in Colonial India 1857–1914". European Review of History. 13 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/13507480600586726. S2CID 144987021.

- ^ Streets, Heather (2004). Martial Races: The military, race and masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857–1914. Manchester University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7190-6962-8. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Omar Khalidi (2003). Khaki and the Ethnic Violence in India: Army, Police, and Paramilitary Forces During Communal Riots. Three Essays Collective. p. 5. ISBN 9788188789092.

Apart from their physique , the martial races were regarded as politically subservient or docile to authority

- ^ Philippa Levine (2003). Prostitution, Race, and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire. Psychology Press. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-0-415-94447-2.

The Saturday review had made much the same argument a few years earlier in relation to the armies raised by Indian rulers in princely states. They lacked competent leadership and were uneven in quality. Commander in chief Roberts, one of the most enthusiastic proponents of the martial race theory, though poorly of the native troops as a body. Many regarded such troops as childish and simple. The British, claims, David Omissi, believe martial Indians to be stupid. Certainly, the policy of recruiting among those without access to much education gave the British more semblance of control over their recruits.

- ^ Amiya K. Samanta (2000). Gorkhaland Movement: A Study in Ethnic Separatism. APH Publishing. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-81-7648-166-3.

Dr . Jeffrey Greenhunt has observed that " The Martial Race Theory had an elegant symmetry. Indians who were intelligent and educated were defined as cowards, while those defined as brave were uneducated and backward. Besides their mercenary spirit was primarily due to their lack of nationalism.

- ^ Ashley Jackson (2005). The British Empire and the Second World War. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 121–122. ISBN 1-85285-417-0.

- ^ Van Der Veer, Peter (1994). Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India. University of California Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-520-08256-4.

- ^ "Prez Bodyguards Only for Rajput, Jats and Sikhs: Army". Outlookindia.com. 2 October 2013.

- ^ Jhutti, Sundeep S. (2003). The Getes. Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 56397976.

The Jats of the Panjab worship their ancestors in a practice known as Jathera.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (1973). "Social Background to the Rise of the Maratha Movement during the 17th Century in India". Indian Economic and Social History Review. SAGE Publications. 10 (3): 214–215. doi:10.1177/001946467301000301. S2CID 144887395.

The Marathas formed the fighting class in Maharashtra and also engaged themselves in agriculture. Like the Jats in north India, their position in the varna system was ambivalent.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2002). Essays in Indian History: Towards a Marxist Perception. Anthem Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-1843310259. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

A historically singular case is that of the Jatts, a pastoral Chandala-like tribe in eighth-century Sind, who attained sudra status by the eleventh century (Alberuni), and had become peasants par excellence (of vaisya status) by the seventeenth century (Dabistani-i Mazahib). The shift to peasant agriculture was probably accompanied by a process of 'sanskritization', a process which continued, when, with the Jat rebellion of the seventeenth century a section of the Jats began to aspire to the position of zamindars and the status of Rajputs.

- ^ Stern, Robert W. (1988). The Cat and the Lion: Jaipur State in the British Raj. Leiden: BRILL. p. 287. ISBN 9789004082830.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2010). Religion, Caste & Politics in India. Primus Books. p. 431. ISBN 9789380607047.

- ^ Vishwanath, L. S. (2004). "Female Infanticide: The Colonial Experience". Economic and Political Weekly. 39 (22): 2313–2318. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4415098.

The 1921 census reports classifies castes into two categories, namely, castes. having a tradition' of female infanticide and castes without such a tradition (see table). This census provides figures from 1901 to 1921 to show that in Punjab, United Provinces and Rajputana castes such as Hindu rajputs, Hindu jats and gujars with 'a tradition' of female infanticide had a much lower number of females per thousand males compared to castes without such a tradition which included: Muslim rajputs, Muslim jats, chamar, kanet, arain, kumhar, kurmi, brahmin, dhobi, teli and lodha

- ^ VISHWANATH, L. S. (1994). "Towards a Conceptual Understanding of Female Infanticide and Neglect in Colonial India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 55: 606–613. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44143417.

By 1850, several castes, in North India, the Jats, Ahirs, Gujars and Khutris, and the Lewa Patidar Kanbis in Central Gujarat were found to practice female infanticide. The colonial authorities also found that both in rural North and West India, the castes which practised female infanticide were propertied (they owned substantial arable land), had the hypergamous marriage norm and paid large dowries.

- ^ Mann, Kamlesh (1988). "Status Portrait of Jat Woman". Indian Anthropologist. 18 (1): 51–67. ISSN 0970-0927. JSTOR 41919573.

- ^ Singh, Kumar Suresh (1992). People of India: Haryana. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 425. ISBN 978-81-7304-091-7.

Ror clans: Sangwan, Dhiya, Malik, Lather, etc, are also found among the Jats. From an economic point of view the Rors living in Karnal and Kurukshetra districts consider themselves better off than their counterparts in Jind and Sonepat districts.

- ^ Ahmed, Mukhtar (18 April 2016). The Arains: A Historical Perspective. Createspace. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-5327-8117-9.

Some clans of the Arains which is also shared by Rajputs and the Jats. Bhutto is another variant of Bhutta. Some important Arian clans overlap with the Rajputs, for instance: Sirohsa, Ganja, Shaun, Bhatti, Butto, Chachar, Indrai, Joiya...

- ^ Ahmed, Mukhtar (18 April 2016). The Arains: A Historical Perspective. Createspace. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-5327-8117-9.

Some clans of the Arains which is also shared by Rajputs and the Jats. Bhutto is another variant of Bhutta. Some important Arian clans overlap with the Rajputs, for instance: Sirohsa, Ganja, Shaun, Bhatti, Butto, Chachar, Indrai, Joiya...

- ^ Marshall, J. A. (1960). Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. p. 24.

- ^ Webster, John C. B. (22 December 2018). A Social History of Christianity: North-west India since 1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-909757-9.

추가열람

- Bayly, C. A. (1989). Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-0-521-38650-0. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Brass, Tom (1995). New farmers' movements in India. Taylor & Francis. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-0-7146-4134-8. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Byres, T. J. (1999). Rural labour relations in India. Taylor & Francis. pp. 217–. ISBN 978-0-7146-8046-0. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Chowdhry, Prem (2008). "Customs in a Peasant Economy: Women in Colonial Harayana". In Sarkar, Sumit; Sarkar, Tanika (eds.). Women and social reform in modern India: a reader. Indiana University Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-253-22049-3. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Gupta, Akhil (1998). Postcolonial developments: agriculture in the making of modern India. Duke University Press. pp. 361–. ISBN 978-0-8223-2213-9. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Gupta, Dipankar (1 January 1996). Political sociology in India: contemporary trends. Orient Blackswan. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-81-250-0665-7. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12786-8. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Jalal, Ayesha (1995). Democracy and authoritarianism in South Asia: a comparative and historical perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-0-521-47862-5. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Larson, Gerald James (1995). India's agony over religion. SUNY Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-7914-2412-4. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Lynch, Owen M. (1990). Divine passions: the social construction of emotion in India. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-06647-2. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Mazumder, Rajit K. (2003). The Indian army and the making of Punjab. Orient Blackswan. pp. 176–. ISBN 978-81-7824-059-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Misra, Maria (2008). Vishnu's crowded temple: India since the Great Rebellion. Yale University Press. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-0-300-13721-7. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Oldenburg, Veena Talwar (2002). Dowry murder: the imperial origins of a cultural crime. Oxford University Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-19-515071-1. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Pandian, Anand; Ali, Daud, eds. (1 September 2010). Ethical Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-253-22243-5. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 12, 26, 28. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Richards, John F. (26 January 1996). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Shweder, Richard A.; Minow, Martha; Markus, Hazel Rose (November 2004). Engaging cultural differences: the multicultural challenge in liberal democracies. Russell Sage Foundation. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-0-87154-795-8. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph (2007). "Caste Regions of the Northern Plain". In Singer, Milton; Cohn, Bernard S. (eds.). Structure and Change in Indian Society. Transaction Publishers. pp. 81–114. ISBN 978-0-202-36138-3. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Stern, Robert W. (2003). Changing India: bourgeois revolution on the subcontinent. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-521-00912-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Talbot, Ian (1996). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the partition of India. Psychology Press. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0427-9. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Tan, Tai Yong (2005). The garrison state: the military, government and society in colonial Punjab 1849–1947. SAGE. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-0-7619-3336-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Wadley, Susan Snow (2004). Raja Nal and the Goddess: the north Indian epic Dhola in performance. Indiana University Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-253-34478-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind: Early medieval India and the expansion of Islam, 7th-11th centuries. BRILL. pp. 163–. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8. Retrieved 15 October 2011.