만화책의 황금시대

Golden Age of Comic Books| 만화책의 황금시대 | |

|---|---|

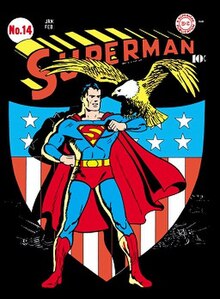

골든 에이지의 촉매제 슈퍼맨:슈퍼맨 #14(1942년 2월) 프레드 레이의 커버 아트 | |

| 시간 범위 | 1938 – 1956 |

| 관련 기간 | |

| 선행 | 플래티넘 에이지 오브 코믹스 |

| 이어서 | 은빛 만화 시대 |

만화책의 황금기는 1938년부터 1956년까지 미국 만화책의 시대를 묘사한다.이 시기 동안 현대 만화책이 처음 출판되었고 인기가 급격히 증가했다.슈퍼히어로의 원형이 만들어졌고 슈퍼맨, 배트맨, 샤잠, 캡틴 아메리카, 원더 우먼을 포함한 많은 유명한 캐릭터들이 소개되었다.

어원학

"골든 에이지"라는 용어를 처음 사용한 것은 리처드 A에 의해 기록되었다. 루포프는 1960년 [1]4월 팬진 코믹 아트 중 하나인 "Re-Birth"라는 기사에서 실렸다.

역사

골든 에이지의 시작을 알리는 것으로 많은 사람들에 의해 인용된 사건은 1938년 Detective[3] Comics(DC Comics의 전신)에 의해 출판된 액션 코믹스 #[2]1에 슈퍼맨이 데뷔한 것이다.슈퍼맨의 인기는 만화책들을 [4]출판의 주요 부분으로 만드는 데 도움을 주었고, 이것은 경쟁 회사들이 슈퍼맨의 [5][6]성공을 모방하기 위해 그들만의 슈퍼히어로들을 만들도록 만들었다.

제2차 세계 대전

1939년에서 1941년 사이에 탐정 코믹스와 자매회사인 올 아메리칸 퍼블리케이션즈는 배트맨과 로빈, 원더우먼, 플래시, 그린 랜턴, 닥터페이트, 아톰, 호크맨, 그린 애로우, [7]아쿠아맨과 같은 인기 슈퍼히어로들을 소개했다.1940년대 마블 코믹스의 전신인 타임리 코믹스는 휴먼 토치, 서브 매리너, 캡틴 [8]아메리카를 주인공으로 한 밀리언셀러 타이틀을 가지고 있었다.비록 DC와 타임리 캐릭터가 오늘날 잘 기억되고 있지만, 발행부수치에 따르면 그 시대의 가장 많이 팔린 슈퍼히어로 타이틀은 발행부당 약 140만 부가 팔린 포싯 코믹스의 캡틴 마블이었다.그 만화는 한때 인기를 [9]이용하기 위해 격주로 출판되었다.

1940년 [10]실드가 등장한 이후 제2차 세계대전 당시 빨간색, 흰색, 파란색 옷을 입은 애국 영웅들이 특히 인기를 끌었다.이 시기의 많은 영웅들은 추축국과 싸웠고 캡틴 아메리카 코믹스 [11]#1과 같은 표지에는 나치 지도자 아돌프 히틀러를 때리는 타이틀 캐릭터가 표시되었다.

만화책이 인기를 끌면서 출판사들은 다양한 장르로 확장되는 제목을 출시하기 시작했다.Dell Comics의 슈퍼히어로가 아닌 캐릭터들(특히 월트 디즈니 애니메이션 캐릭터 만화)은 [12]그 날의 슈퍼히어로 만화보다 더 많이 팔렸다.이 출판사는 미키 마우스, 도널드 덕, 로이 로저스, [13]타잔과 같은 허가된 영화와 문학 캐릭터들을 선보였다.도널드 덕의 작가이자 예술가인 칼 바크스가 두각을 [14]나타낸 것은 이 시대였다.게다가 MLJ가 펩 코믹스 #22에 아치 앤드류스를 소개하면서, 아치 앤드류 캐릭터가 [16]21세기까지 인쇄된 채로 10대 유머 [15]만화가 탄생했다.

동시에 캐나다에서는 필수품이 아닌 물품의 수입을 제한하는 전쟁 교환 보존법에[17] 따라 미국 만화책은 수입이 금지되었다.캐나다의 출판사들은 이러한 경쟁의 부족에 대해 비공식적으로 캐나다 화이트라고 불리는 그들만의 타이틀을 제작함으로써 대응했다.전쟁 중에는 이러한 칭호들이 번성했지만, 이후 무역 제한이 풀리면서 살아남지 못했다.

전후

교육용 만화책인 Dagwood Splits the Atom은 연재 만화 Blondie에 [18]나오는 캐릭터들을 사용했다.역사학자 마이클 A에 따르면.아문손의 매력적인 만화책 캐릭터들은 핵전쟁에 대한 어린 독자들의 두려움을 덜어주고 원자력에 [19]의해 제기되는 질문에 대한 불안을 잠재우는데 도움을 주었다.EC코믹스의 매드와 델의 포컬러 코믹스의 칼 바크스의 삼촌 스크루지를 포함한 장기간의 유머 만화가 등장한 것은 이 시기였다.[20][21]

1953년 [22]미국 상원 소년범죄소위원회가 소년범죄 문제를 조사하기 위해 만들어지면서 만화업계는 파행을 겪었다.이듬해 만화가 미성년자들의 불법 행위를 촉발했다는 프레드릭 베르담의 '순수의 유혹'이 출간되자 EC의 윌리엄 게인스 같은 만화책 출판사들이 공청회에서 [23]증언을 하도록 소환됐다.그 결과, 만화책 [24]출판사의 자체 검열을 제정하기 위해 코믹스 매거진 출판사 협회에 의해 만화 코드 기관이 만들어졌다.이 시기에 EC는 범죄와 공포의 제목을 취소하고 주로 [24]매드에 초점을 맞췄다.

슈퍼히어로로부터의 전환

1940년대 후반, 슈퍼히어로 만화의 인기는 시들해졌다.독자들의 관심을 유지하기 위해, 만화 출판사들은 전쟁, 서부, 공상과학, 로맨스, 범죄,[25] 공포와 같은 다른 장르로 다양화했다.많은 슈퍼히어로 타이틀들이 취소되거나 다른 [citation needed]장르로 전환되었다.

1946년 DC 코믹스의 슈퍼보이, 아쿠아맨, 그린 애로우는 모어 펀 코믹스에서 어드벤처 코믹스로 전환되어 모어 펀이 [26]유머에 집중할 수 있게 되었다.1948년 그린 랜턴, 조니 썬더, 미드나이트 박사가 출연한 올 아메리칸 코믹스는 올 아메리칸 [citation needed]웨스턴으로 대체되었다.이듬해 플래시 코믹스와 그린 랜턴이 [citation needed]취소되었다.1951년 미국정의협회를 다룬 올스타 코믹스는 올스타 웨스턴이 되었다.그 다음 해에 로빈이 출연한 스타 스팽글드 코믹스는 스타 스팽글드 워 [citation needed]스토리로 제목이 바뀌었다.원더우먼을 주인공으로 한 센세이션 [citation needed]코믹스는 1953년에 취소되었다.1950년대 내내 계속해서 출판된 유일한 슈퍼히어로 만화들은 액션 코믹스, 어드벤처 코믹스, 배트맨, 탐정 코믹스, 슈퍼보이, 슈퍼맨, 원더우먼, 월드 파인스트 [27]코믹스였다.

플라스틱 맨은 1950년까지 Quality Comics의 Police Comics에 등장했고, 그 후 추리소설로 초점이 바뀌었다. 그의 솔로 타이틀은 1955년 2월 52호까지 격월로 계속되었다.Timily Comics의 The Human Torch는 #35호 (1949년 [28]3월호)로 취소되었고, #93호 (1949년 8월호)는 공포 만화 마블 스토리가 되었다.[29]Sub-Mariner Comics는 #42(1949년 6월호), Captain America Comics는 #75(1950년 2월호)로 취소되었다.하비 코믹스의 블랙 캣은 1951년에 취소되었고 그 해 말에 공포 만화로 재기동되었다. 제목은 블랙 캣 미스테리, 블랙 캣 미스틱, 그리고 최종적으로 블랙 캣 웨스턴으로 바뀌었는데, 블랙 캣 [30]스토리가 포함되었다.Lev Gleason Publications의 데어데블은 1950년 [31]Little Wise Guys에 의해 타이틀에서 근소한 차이로 밀려났다.포싯 코믹스의 휘즈 코믹스, 마스터 코믹스, 캡틴 마블 어드벤처스는 1953년에 취소되었고 마블 패밀리는 이듬해 [32]취소되었다.만화책의 실버 에이지는 일반적으로 DC 코믹스의 새로운 플래시인 골든 에이지 이후 처음으로 성공한 새로운 슈퍼히어로가 쇼케이스 #4에 데뷔하면서 시작되었다고 알려져 있다.[33][34][35]

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Quattro, Ken (2004). "The New Ages: Rethinking Comic Book History". Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

... according to fanzine historian Bill Schelly, 'The first use of the words "golden age" pertaining to the comics of the 1940s was by Richard A. Lupoff in an article called'"Re-Birth' in Comic Art #1 (April 1960).

- ^ "The Golden Age of Comics". History Detectives: Special Investigations. PBS. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

The precise era of the Golden Age is disputed, though most agree that it was born with the launch of Superman in 1938.

- ^ "Action Comics #1". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Goulart, Ron (2000). Comic Book Culture: An Illustrated History (1st American ed.). Portland, Oregon: Collectors Press. p. 43. ISBN 9781888054385.

- ^ Eury, Michael (2006). The Krypton Companion: A Historical Exploration of Superman Comic Books of 1958-1986. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 1893905616.

since Superman inspired so many different super-heroes.

- ^ Hatfield, Charles (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature (1st ed.). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 10. ISBN 1578067197.

the various Superman-inspired "costume" comics

- ^ Various (January 19, 2005). The DC Comics Rarities Archives, Vol. 1. New York, New York: DC Comics. ISBN 1401200079.

- ^ Vernon Madison, Nathan (January 3, 2013). Anti-Foreign Imagery in American Pulps and Comic Books, 1920–1960. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0786470952.

- ^ Morse, Ben (July 2006). "Thunderstruck". Wizard (179).

- ^ Madrid, Mike (September 30, 2013). Divas, Dames & Daredevils: Lost Heroines of Golden Age Comics. Minneapolis, MN: Exterminating Angel Press. p. 29.

- ^ "Captain America Comics (1941) #1". Marvel Comics. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Benton, Mike (November 1989). The Comic Book in America: An Illustrated History. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing Company. p. 158. ISBN 0878336591.

- ^ Duncan, Randy; J. Smith, Matthew (January 29, 2013). Icons of the American Comic Book: From Captain America to Wonder Woman, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 193–201. ISBN 978-0313399237.

- ^ "Donald Duck "Lost in the Andes" The Comics Journal". Tcj.com. January 24, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Nadel, Dan (Jun 1, 2006). Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries, 1900–1969. New York: Abrams Books. p. 8. ISBN 0810958384.

- ^ Telling, Gillian (July 6, 2015). "Mark Waid discusses 'overwhelmingly positive' reaction to Archie Andrews' new look after 75 years of Archie". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ 전쟁교류보전법, 1940년 S.C. 1940-41, c. 2

- ^ "Dagwood splits the atom The Ephemerist". Sparehed.com. 14 May 2007. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Zeman, Scott C.; Amundson, Michael A. (2004). Atomic Culture: How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. p. 11. ISBN 9780870817632.

- ^ Gertler, Nat; Lieber, Steve (6 July 2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Creating a Graphic Novel. New York: Alpha Books. p. 178. ISBN 1592572332.

- ^ Farrell, Ken (1 May 2006). Warman's Disney Collectibles Field Guide: Values and Identification. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 327. ISBN 0896893227.

- ^ Binder, Arnold; Geis, Gilbert (1 January 2001). Juvenile Delinquency: Historical, Cultural & Legal Perspectives (Third ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Routledge. p. 220. ISBN 1583605037.

- ^ Kiste Nyberg, Amy (1 February 1998). Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code (Studies in Popular Culture). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 59. ISBN 087805975X.

- ^ a b Kiste Nyberg, Amy. "Comics Code History: The Seal of Approval". cbldf.org. Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Kovacs, George; Marshall, C. W. (2011). Classics and Comics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780199734191.

- ^ Daniel, Wallace; Gilbert, Laura (September 20, 2010). DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. New York: DK Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0756667429.

Following More Fun Comics change in focus the previous month, the displaced super-heroes Superboy, Green Arrow, Johnny Quick, Aquaman, and the Shining Knight were welcomed by Adventure Comics.

- ^ Schelly, William (2013). American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1950s. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490540.

- ^ "The Human Torch". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ "Marvel Mystery Comics". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Schoell, William (June 26, 2014). The Horror Comics: Fiends, Freaks and Fantastic Creatures, 1940–1980s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 82. ISBN 978-0786470273.

- ^ Plowright, Frank (September 22, 2003). The Slings & Arrows Comic Guide. Marietta, Georgia: Top Shelf Productions. p. 159. ISBN 0954458907.

- ^ Conroy, Mike (August 1, 2003). 500 Great Comic Book Action Heroes. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series. p. 208. ISBN 0764125818.

- ^ Shutt, Craig (2003). Baby Boomer Comics: The Wild, Wacky, Wonderful Comic Books of the 1960s!. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 20. ISBN 087349668X.

The Silver Age started with Showcase #4, the Flash's first appearance.

- ^ Sassiene, Paul (1994). The Comic Book: The One Essential Guide for Comic Book Fans Everywhere. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, a division of Book Sales. p. 69. ISBN 9781555219994.

DC's Showcase No. 4 was the comic that started the Silver Age

- ^ "DC Flashback: The Flash". Comic Book Resources. July 2, 2007. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

외부 링크

- 만화책 플러스 (공영영역 추정 골든 에이지 만화)

- 디지털 코믹 뮤지엄(공영 도메인 추정 골든 에이지 만화)

- 돈 마크스타인의 투노피디아

- 슈퍼히어로 국제 카탈로그

- 제스 네빈스의 골든 에이지 슈퍼히어로 백과사전

- 빌런 페이퍼 골든 에이지 만화 구독 서비스