카타르히니

Catarrhini| 카타린류 시간 범위: | |

|---|---|

| |

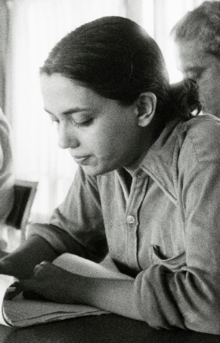

| 스텀프테일 마카크 | |

| |

| 스위스 세인트 갈렌, Gossau, Walter 동물원의 침팬지 (Pantroglodytes) | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 초르다타 |

| 클래스: | 포유류 |

| 순서: | 영장류 |

| 부분 순서: | Haplorhini |

| 중층수: | 시미포름류 |

| 파보더: | 카타르히니 1812년[1][2] 지오프로이 |

| 슈퍼패밀리 | |

|

| |

| 동의어 | |

카타르히니/k æ ɪ라 ɪ나 əˈ/, 카타르히니 원숭이, 구세계 인류 또는 구세계 원숭이는 Cercopithecoidea와 유인원(Hominoidea)으로 구성되어 있습니다. 1812년, 제프로이는 이 두 그룹을 하나로 묶고 "구세계 원숭이" ("Catarrhini")라는 이름을 설립했습니다.[4][3][5][2][6] 시미포름목에 속하는 자매는 파보르데 플라티르리니(신세계원숭이)입니다.[2] 과학적 증거에도 불구하고 유인원을 직접 원숭이로 지정하는 것에 대한 저항이 있어왔기 때문에 "구세계원숭이"는 세르코피테코이데아 또는 카타르히니아라는 뜻으로 받아들여질 수 있습니다.[4][7][8][9][10][6][11][12][13][14] 유인원이 원숭이라는 것은 18세기에 이미 Gorge-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon에 의해 실현되었습니다.[3] 린네는 1758년에 현재 우리가 타르시에와 신세계원숭이로 인식하는 단일 속 "Simia" (산스 호모)에 이 그룹을 배치했습니다.[15] 카타르히니는 모두 아프리카와 아시아가 원산지입니다. 이 파보더의 구성원들은 카타린이라고 불립니다.

카타르히니는 신세계 원숭이인 플라티르히니의 자매 그룹입니다.[16][17][18][19] 유인원인 Cercopithecoidea가 갈라지기 약 600만 년 전, 플라티르리니는 아마도 바다를 통해 아프로-아라비아 (구세계)에서 남아메리카로 이주함으로써 "원숭이" 내에서 출현했습니다.

묘사

신대륙 플라타린과 구대륙 카타린의 기술적인 구별은 코의 모양입니다. (고대 그리스어로 "flat", "rhin", "nose"에서 유래된) 플라티라인(platy-)은 옆으로 향한 콧구멍을 가지고 있습니다. (고대 그리스어 katà-, "아래", "코"에서 온) 카타린은 아래쪽을 향한 콧구멍을 가지고 있습니다. 또한 카타린은 전치미가 전혀 없고, 편평한 손톱과 발톱, 관 모양의 외음부(귀뼈), 12개가 아닌 8개의 전치부를 가지고 있어 2.1.2.32.1.2.3의 치관식을 가지며,[20] 위턱과 아래턱의 각 면에 2개의 앞니, 1개의 개, 2개의 전치부, 3개의 어금니를 나타냅니다.

대부분의 카타린 종은 상당한 성적 이형성을 보이며 쌍결합을 형성하지 않습니다. 전부는 아니지만 대부분의 종들은 사회적 집단을 이루어 삽니다.[citation needed] 플라타린류와 마찬가지로, 카타린류는 일반적으로 주행성이며,[20] 손을 잡고 발을 잡고 있다.

전통적인 명명법과 계통발생학적 명명법 모두에서 유인원은 전적으로 카타린 종입니다. 전통적인 용법에서, 유인원은 꼬리가 없고, 더 크고, 더 전형적으로 땅에 사는 종의 카타린을 설명합니다. "에이프"는 바바리 유인원과 같은 종의 일반적인 이름의 일부로 발견될 수 있습니다. 계통발생학적 용법에서 유인원이라는 용어는 호미노상과(Superfamily Hominoidea)에만 적용됩니다. 이 그룹은 두 개의 패밀리로 구성됩니다. 작은 유인원 또는 긴팔원숭이인 Hylobatidae와 오랑우탄, 고릴라, 침팬지, 인간을 포함한 큰 유인원 및 인간 이전의 오스트랄로피테신스 및 거대 오랑우탄 친척인 Gigantopithecus와 같은 관련 멸종된 속.

분류와 진화

슈라고 앤 루소에 따르면, 신세계 원숭이들은 약 3천 5백만년 전에 구세계 친척으로부터 갈라졌다고 합니다. 그들은 약 25 Mya(화석 증거에 의해 강력하게 뒷받침된다고 주장하는)의 세르코피테코이드와 호미노이드 사이의 주요 카타린 분할을 교정점으로 사용하고, 이로부터 약 15-19 Mya(인간 포함)의 유인원에서 분리된 긴팔원숭이도 계산합니다.[21]

Begen과 Harrison에 따르면, 카타르히니는 44-40 Mya 정도의 신세계 원숭이로부터 갈라졌고, 최초의 카타르히니는 아프리카와 아라비아에 출현했고, 18-17 Mya까지 유라시아(아라비아 밖)에 출현하지 않았습니다.[22]

카타르히니는 플라티르히니에서 분리된 후 언젠가 다른 모든 포유류 계통에 존재하는 알파-갈락토시다아제 효소를 잃었습니다. 알파-갈락토시다아제 유전자를 "끄는" 돌연변이를 가진 개인만이 이 병원체에 대한 항체를 생성하고 생존했을 것이기 때문에 알파-갈락토시다아제를 포함한 고대 병원체가 원인일 수 있다는 가설이 있습니다.[23][24]

원숭이와 원숭이의 구별은 전통적인 원숭이의 비유에 의해 복잡합니다: 유인원은 신세계 원숭이의 자매 그룹인 카타린에서 구세계 원숭이의 자매 그룹으로 출현했습니다. 따라서, 원숭이, 카타린류, 그리고 Parapithecidae와 같은 관련된 동시대 멸종된 그룹들도 원숭이입니다. 또한 "구세계원숭이"는 유인원과 이집트숲모기(Egyptopithecus)와 같은 멸종된 종을 포함한 모든 카타린을 포함하는 것으로 간주될 수 있습니다. 이 경우 유인원, 케르코피테코이데아(Cercopithecoidea), 이집트숲모기(Egyptopithecus)가 구세계원숭이 내에서 출현했습니다. 비록 영어에서 유인원과 원숭이 같은 용어들의 구어체 사용이 그들의 진정한 생물학적 관계에 대한 오해를 반영하지만, 일부 다른 언어에서는 그렇지 않습니다. 예를 들어, 러시아어에서는 유인원을 포함하여 꼬리가 있거나 없는 모든 유인원을 설명하기 위해 동일한 용어가 사용됩니다.[25]

- 영장류[1] 주문

- Strepsirrhini 아목: 여우원숭이, 로리스 등

- 하플로리니아목 : 원숭이를 포함한 타시어 + 원숭이

- 근일점 타르시이폼류

- 타르시아과 (학명: tarsiidae)

- 유인원류(Infraorder Simiformes) : 유인원류를 포함한 원숭이, 또는 그 이상의 영장류

- 파보르데 카타르히니

- 슈퍼패밀리 † 프로필리오피테코이데아

- †과 (Egyptopithecus)

- 슈퍼패밀리 † Pliopithecoidea

- †과 (Dionysopithecidae)

- †과 (Pliopithecidae)

- 슈퍼패밀리 † 덴드로피테코이데아

- †과 (Dendropithecidae)

- 슈퍼패밀리 †사아다니오이데아

- †사다니과

- 서코피테코이데아과 (Superfamily Cercopithecoidea)

- 호미노상과 (Superfamily Hominoidea) : 유인원

- 긴팔원숭이과 (Hylobatidae)

- 호미니과 (Hominiidae) : 유인원 (사람 포함)

- 슈퍼패밀리 † 프로필리오피테코이데아

- 파보르데 플라티르리니: 신세계원숭이

- 파보르데 카타르히니

- 근일점 타르시이폼류

클라도그램

아래는 프롤리오피테코이데아에서 출현한 왕관 카타르히니가 멸종된 종을 가진 클라도그램입니다.[26][27][28][29][30][31] 또한, 사아다니오이데아는 이곳의 크라운 카타르히니보다는 세르코피테코이데아의 자매입니다. 몇 백만 년 전(Mya)의 분기군이 새로운 분기군으로 분기되었는지 표시됩니다.

| 크라운시미안즈(37) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

플라티르리니는 올리고피테과(Oligopithecidae)에서 출현했을 수 있습니다.[32] 사아다니오이데아는 프롤리오피테코이데아 s.s.의 자매일 수도 있고, 마이크로피테쿠스는 타카 프롤리오피테키데스의 자매일 수도 있습니다.[33]

참고문헌

- ^ a b Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 111–184. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, M.É. (1812). "Tableau des Quadrumanes, ou des animaux composant le premier Ordre de la Classe des Mammifères". Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle. Paris. 19: 85–122. Archived from the original on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- ^ a b c d Martin, W.C. Linnaeus (1841). A General Introduction to The Natural History Mamminferous Animals, With a Particular View of the Physical History of Man, and the More Closely Allied Genera of the Order Quadrumana, or Monkeys. London: Wright and Co. printers. pp. 339, 340, 361.

- ^ a b Osman Hill, W.C. (1953). Primates Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy I—Strepsirhini. Edinburgh Univ Pubs Science & Maths, No 3. Edinburgh University Press. p. 53. OCLC 500576914.

- ^ Buffon, Georges Louis Leclerc comte de (1827). Oeuvres complètes de Buffon: avec les descriptions anatomiques de Daubenton, son collaborateur (in French). Verdière et Ladrange. p. 61. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ^ a b Bugge, J. (1974). "Chapter 4". Cells Tissues Organs. 87 (Suppl. 62): 32–43. doi:10.1159/000144209. ISSN 1422-6405.

- ^ "Thomas Geissmann's Gibbon Research Lab.: Die Gibbons (Hylobatidae): Eine Einführung". www.gibbons.de. Archived from the original on 2023-03-26. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ "Reconstruction of Ancient Chromosomes Offers Insight Into Mammalian Evolution". UC Davis. 2017-06-21. Archived from the original on 2023-05-26. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ Archibald, J. David (2014-07-15). Aristotle's Ladder, Darwin's Tree: The Evolution of Visual Metaphors for Biological Order. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231164122. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ Lacoste, Vincent; Lavergne, Anne; Ruiz-García, Manuel; Pouliquen, Jean-François; Donato, Damien; James, Samantha (2018-09-15). "DNA Polymerase Sequences of New World Monkey Cytomegaloviruses: Another Molecular Marker with Which To Infer Platyrrhini Systematics". Journal of Virology. 92 (18): e00980–18. doi:10.1128/JVI.00980-18. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 6146696. PMID 29976674.

- ^ James, Samantha; Donato, Damien; Pouliquen, Jean-François; Ruiz-García, Manuel; Lavergne, Anne; Lacoste, Vincent (2018-07-05). "DNA Polymerase Sequences of New World Monkey Cytomegaloviruses: Another Molecular Marker with Which To Infer Platyrrhini Systematics". Journal of Virology. 92 (18). doi:10.1128/JVI.00980-18. PMC 6146696. PMID 29976674.

- ^ Marc Luetjens, C.; Weinbauer, Gerhard F.; Wistuba, Joachim (2007-03-15). "Primate spermatogenesis: new insights into comparative testicular organisation, spermatogenic efficiency and endocrine control". Biological Reviews. 80 (3): 475–488. doi:10.1017/S1464793105006755. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 16094809. S2CID 21241457. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ^ Osorio, Daniel (2021-08-19). Simmons, Leigh (ed.). "What is primate color vision for? a comment on Caro et al". Behavioral Ecology. 32 (4): 571–572. doi:10.1093/beheco/arab050. ISSN 1045-2249. Archived from the original on 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ Nakamura, Tomonori; Fujiwara, Kohei; Saitou, Mitinori; Tsukiyama, Tomoyuki (2021-05-11). "Non-human primates as a model for human development". Stem Cell Reports. 16 (5): 1093–1103. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.03.021. ISSN 2213-6711. PMC 8185448. PMID 33979596.

- ^ Linné, Carl von; Salvius, Lars (1758). Caroli Linnaei...Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. 1. Holmiae: Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ Garbino, Guilherme Siniciato Terra; De Aquino, Carla Cristina (2018). "Evolutionary Significance of the Entepicondylar Foramen of the Humerus in New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini)". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25: 141–151. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9366-5. S2CID 3268953.

- ^ Fulwood, Ethan L.; Boyer, Doug M.; Kay, Richard F. (2016). "Stem members of Platyrrhini are distinct from catarrhines in at least one derived cranial feature". Journal of Human Evolution. 100: 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.08.001. PMID 27765146.

- ^ Dixson, Alan (2015). "Primate sexuality". The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality. pp. 861–1042. doi:10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs375. ISBN 9781118896877.

- ^ Takai, Masanaru; Maung-Maung; Sein, Chit; Soe, Aung Naing; Thaung-Htike; Zin-Maung-Maung-Thein (2017-01-01). "Chapter 9 Review of the investigation of primate fossils in Myanmar". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 48 (1): 185–206. doi:10.1144/M48.9. ISSN 0435-4052. S2CID 90910477.

- ^ a b "Catarrhini Infraorder". ChimpanZoo (The Jane Goodall Institute). Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Schrago, C. G.; Russo, C. A. (2003). "Timing the Origin of New World Monkeys". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 20 (10): 1620–1625. doi:10.1093/molbev/msg172. PMID 12832653.

- ^ Harrison, Terry (2013). "Catarrhine Origins". A Companion to Paleoanthropology. pp. 376–396. doi:10.1002/9781118332344.ch20. ISBN 9781118332344.

- ^ Koike, Chihiro; Uddin, Monica; Wildman, Derek E.; Gray, Edward A.; Trucco, Massimo; Starzl, Thomas E.; Goodman, Morris (9 January 2007). "Functionally important glycosyltransferase gain and loss during catarrhine primate emergence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (2): 559–564. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104..559K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610012104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1766424. PMID 17194757.

- ^ "Did An Ancient Pathogen Reshape Our Cells?". YouTube. Public Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Monkeys and apes". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12.

- ^ Seiffert, Erik R.; Boyer, Doug M.; Fleagle, John G.; Gunnell, Gregg F.; Heesy, Christopher P.; Perry, Jonathan M. G.; Sallam, Hesham M. (2018). "New adapiform primate fossils from the late Eocene of Egypt". Historical Biology. 30 (1–2): 204–226. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1306522. S2CID 89631627. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ Stevens, Nancy J.; Seiffert, Erik R.; o'Connor, Patrick M.; Roberts, Eric M.; Schmitz, Mark D.; Krause, Cornelia; Gorscak, Eric; Ngasala, Sifa; Hieronymus, Tobin L.; Temu, Joseph (2013). "Palaeontological evidence for an Oligocene divergence between Old World monkeys and apes" (PDF). Nature. 497 (7451): 611–614. Bibcode:2013Natur.497..611S. doi:10.1038/nature12161. PMID 23676680. S2CID 4395931. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-18. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ^ Rossie, James B.; Hill, Andrew (2018). "A new species of Simiolus from the middle Miocene of the Tugen Hills, Kenya". Journal of Human Evolution. 125: 50–58. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.09.002. PMID 30502897. S2CID 54625375.

- ^ Rasmussen, D. Tab; Friscia, Anthony R.; Gutierrez, Mercedes; Kappelman, John; Miller, Ellen R.; Muteti, Samuel; Reynoso, Dawn; Rossie, James B.; Spell, Terry L.; Tabor, Neil J.; Gierlowski-Kordesch, Elizabeth; Jacobs, Bonnie F.; Kyongo, Benson; Macharwas, Mathew; Muchemi, Francis (2019). "Primitive Old World monkey from the earliest Miocene of Kenya and the evolution of cercopithecoid bilophodonty". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (13): 6051–6056. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.6051R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1815423116. PMC 6442627. PMID 30858323.

- ^ Nengo, Isaiah; Tafforeau, Paul; Gilbert, Christopher C.; Fleagle, John G.; Miller, Ellen R.; Feibel, Craig; Fox, David L.; Feinberg, Josh; Pugh, Kelsey D.; Berruyer, Camille; Mana, Sara; Engle, Zachary; Spoor, Fred (2017). "New infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape evolution" (PDF). Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..169N. doi:10.1038/nature23456. PMID 28796200. S2CID 4397839. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-08-31. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Seiffert, Erik R. (2007). "Evolution and Extinction of Afro-Arabian Primates Near the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary". Folia Primatologica. 78 (5–6): 314–327. doi:10.1159/000105147. ISSN 0015-5713. PMID 17855785. S2CID 45717795. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- ^ Defler, Thomas (2019). "Platyrrhine Monkeys: The Fossil Evidence". History of Terrestrial Mammals in South America. Topics in Geobiology. Vol. 42. pp. 161–184. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98449-0_8. ISBN 978-3-319-98448-3. S2CID 91938226.

- ^ Wisniewski, Anna L.; Lloyd, Graeme T.; Slater, Graham J. (2022-05-25). "Extant species fail to estimate ancestral geographical ranges at older nodes in primate phylogeny". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 289 (1975): 20212535. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.2535. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 9115010. PMID 35582793.

더보기

- Sellers, Bill (2000-10-20). "Primate Evolution" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- Raaum, Ryan L.; Sterner, Kirstin N.; Noviello, Colleen M.; Stewart, Caro-Beth; Disotell, Todd R. (2005). "Catarrhine primate divergence dates estimated from complete mitochondrial genomes: Concordance with fossil and nuclear DNA evidence". Journal of Human Evolution. 48 (3): 237–257. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.11.007. PMID 15737392.

외부 링크

위키백과의 카타르히니 관련 자료

위키백과의 카타르히니 관련 자료