습식시장

Wet market| 습식시장 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

홍콩의 한 축축한 시장의 고기 노점. | |||||||||||

| 중국어 번체 | 傳統市場 | ||||||||||

| 중국어 간체 | 传统市场 | ||||||||||

| 하뉴피닌 | 츄앙퉁 shchngngng | ||||||||||

| 주핑 시 | 시운퉁시425 캉캉4 | ||||||||||

| 문자 그대로의 뜻 | 전통시장 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 대체 중국어 이름 | |||||||||||

| 중국어 번체 | 街市 | ||||||||||

| 중국어 간체 | 街市 | ||||||||||

| 주핑 시 | 가아이시15 | ||||||||||

| 문자 그대로의 뜻 | 거리 시장 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

습식시장(공설시장[4] 또는 전통시장이라고도[5] 함)은 신선한 고기, 생선, 농산물, 기타 소비지향적인 부패성 상품을 비슈퍼마켓 환경에서 판매하는 시장으로, 직물, 전자제품 등 내구재를 판매하는 「건조시장」과 구별된다.[6][10]여기에는 농민시장, 어시장, 야생동물 시장 등 매우 다양한 시장이 포함된다.[14]모든 습윤시장이 살아있는 동물을 파는 것은 아니지만,[17] 습윤시장이라는 용어는 때때로 판매상들이 홍콩에서 가금류로 행해지는 [21]것과 같이 고객이 구매하면 동물을 도살하는 살아있는 동물시장을 의미하기 위해 사용된다.[22]젖은 시장은 세계 여러 지역에서 흔하며,[26] 특히 중국, 동남아시아, 남아시아에서 많이 볼 수 있다.그들은 종종 가격, 음식의 신선함, 사회적 상호작용, 그리고 지역 문화의 요소들로 인해 도시 식량 안보에서 중요한 역할을 한다.[27]

대부분의 습윤시장은 야생동물이나 외래동물에서 거래되지 않지만 COVID-19, H5N1 조류독감, 중증급성호흡기증후군(SARS), 원숭이 수두 등 항우노틱 질병의 발생과 연관되어 있다.[32][36]몇몇 국가들은 젖은 시장에 야생동물을 보유하는 것을 금지했다.[33][37]모든 젖은 시장과 살아있는 동물이나 야생동물을 가진 사람들을 구분하지 못하는 언론 보도는 야생동물 밀수를 조장한다는 암시뿐만 아니라, COVID-19 대유행과 관련된 시노포비아를 부추겼다는 비난을 받아왔다.[40]

배경

용어.

"습지시장"이라는 용어는 1970년대 초 싱가포르에서 정부가 이러한 전통시장을 유명해진 슈퍼마켓과 구별하기 위해 사용하면서 널리 쓰이게 되었다.[41]이 용어는 동남아시아 전역에서 사용된 용어로 2016년 옥스퍼드 영어사전(OED)에 추가됐다.[42]OED가 이 용어를 가장 먼저 인용한 것은 1978년 The Straits Times of Singapore이다.[8]

'습지시장'의 '습지'는 식품이 상하지 않도록 하는 데 사용되는 얼음이 녹고,[41][43][44] 육류와 해산물 노점이 씻겨지며, 습지 시장에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 신선한 농산물이 뿌려져 끊임없이 젖은 바닥을 가리킨다.[16][20][43]

"공영시장"이라는 용어는 "습지시장"[1][2][3]과 동의어일 수 있지만 때로는 국유 및 지역사회 소유의 습지시장을 독점적으로 지칭할 수도 있다.[1][2][3]습식 시장은 과일과 야채와 같은 신선한 농산물을 주로 판매하는 수많은 경쟁상대로 구성된 시장을 지칭할 때 "신선한 식품 시장"과 "좋은 식품 시장"이라고도 불릴 수 있다.[9]'습지시장'이라는 용어는 동의어는 아니지만 소비자에게 직접 판매하는 살아있는 동물시장을 뜻하는 말로 자주 쓰인다.[18][19][25][45]

'습지시장'이란 야생동물과 야생생물을 판매하는 시장을 지칭할 수 있지만, 야생생물이 포함된 시장을 독점적으로 지칭하는 '야생시장'이라는 용어와 동의어는 아니다.[29][25][28][30][45]

종류들

신선농산물과 육류를 판매하는 시장을 명시하는 '습지시장'이라는 용어에는 다양한 시장이 포함된다.[1][11]습식 시장은 소유 구조(개인 소유, 국유 또는 지역사회 소유), 규모(도매 또는 소매), 생산물(과일, 야채, 도축육 또는 살아있는 동물)에 따라 분류할 수 있다.[1][11]그들은 육류 재고량이 길들여진 동물에서 발생하는지 또는 야생 동물에서 발생하는지 여부에 따라 추가 하위 분류될 수 있다.[1][11]

전통적 습식시장은 일반적으로 임시창고, 야외공기장소,[1][46][47][16] 부분적으로 개방된 상업단지에 수용되는 반면,[48][25] 현대 습식시장은 환기, 냉동, 냉동시설이 개선된 건물에 수용되는 경우가 많다.[1][49][50]

경제적 역할

습식시장은 물량이 적고 일관성이 강조되지 않아 슈퍼마켓에 비해 수입품에 대한 의존도가 낮다.[51]습식 시장은 2019년 식품 보안 연구에서 특히 중국 도시에서 "도시 식품 보안을 보장하기 위해 매우 중요하다"고 설명되어 왔다.[1]도시 식량 안보를 지원하기 위한 습식 시장의 역할은 음식 가격 책정 및 물리적 접근성을 포함한다.[1]

도시 연구, 식품 유통에 관한 연구, 싱가포르 국립 환경청의 학술 논문들은 습한 시장이 지속되는 주요 이유로 낮은 가격, 더 큰 신선도, 그리고 협상과 사회적 상호 작용의 촉진에 주목했다.[1][44][52][53]습한 시장의 지속성은 또한 "냉동 고기와 달리 갓 도축된 고기와 생선을 요구하는 다양한 전통"[44]에 기인한다.

농업 기반 경제가 있는 개발도상국에서는 주로 재래식 습식 시장이나 육류 판매대를 통해 신선육이 유통된다.[54]신선한 고기를 파는 습식 시장은 종종 도축 시설에 부착되거나 근처에 위치한다.[54]

야생동물 시장 및 구역

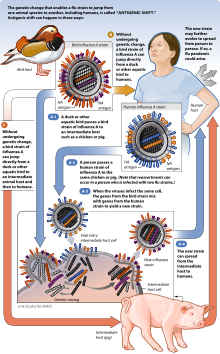

위생기준이 지켜지지 않으면 습식시장이 질병을 확산시킬 수 있다.살아있는 동물과 야생동물을 운반하는 사람들은 특히 조노스를 전송할 위험이 높다.개방성 때문에, 새롭게 도입된 동물들은 야생에서 결코 상호작용하지 않는 판매원, 도축업자, 고객 또는 다른 동물들과 직접 접촉할 수 있다.이것은 일부 동물들이 중간 숙주 역할을 할 수 있게 해줌으로써 질병이 인간에게 퍼지는 것을 도울 수 있다.[34]

COVID-19, H5N1 조류독감, 중증급성호흡기증후군(SARS), 원숭이 수두 등 항정신병 발생은 항정신병 전염 잠재력이 크게 높아지는 야생동물 시장으로 추적됐다.[34][55][56][35]중국의 야생동물 시장은 2002년 사스 발병과 관련이 있다; 시장 환경이 두 발병을 돌연변이로 만들고 그 후에 인간에게 퍼지게 한 조우노틱 기원의 코로나비루스에 최적의 조건을 제공했다고 생각된다.[57]그 COVID-19 유행병의 정확한 유래는 아직 2월 2021[58]하며는 원래 화난 시푸드 도매 시장 중국 우한에서 보도가 초기 사건의 2/3가 화난 해물을 찾아뵈게 됫었다 우한에서 직접 노출되어 때문에 연관되어 있어 확정될 것이다.[59][60][61][62]들은 비록, 2021년까지 세계 보건 기구 조사에 따르면 화난 엄마 결론을 내렸다.초기의 케이스가 존재하기 때문에 rket이 기원이 될 것 같지 않았다.[58]

비위생적인 위생 기준과 조노즈 및 유행병의 확산과의 연관성 때문에, 비평가들은 중국과 전 세계의 주요 건강 위험 요소로 공장 농장과 함께 살아있는 동물 시장을 분류해 왔다.[63][64][65][66]2020년 3월과 4월, 아시아,[67][68][69] 아프리카,[70][71][72] 그리고 전 세계의 야생동물 시장은 건강상의 위험에 노출되기 쉽다는 일부 보도가 있었다.[73]

질병관리 개입

Due to the suspicions that wet markets could have played a role in the emergence of COVID-19, a group of US lawmakers, NIAID director Anthony Fauci, UNEP biodiversity chief Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, and CBCGDF secretary general Zhou Jinfeng called in April 2020 for the global closure of wildlife markets due to the potential for zoonotic diseases and멸종 위기에 처한 [74][75][76][77]종에게 위험을 주다세계보건기구는 2021년 4월 미래 유행병을 막기 위해 식품시장에서 살아있는 동물의 판매를 전면 금지할 것을 요구했다.[78]

행성 건강 연구는 살아있는 동물 시장을 불법화하는 대신, 질병 통제 개입 조치가 젖은 시장에서 시행될 것을 요구해왔다.[79][80][81]세계보건기구(WHO)가 2020년 4월 습식시장 개방 요건으로 개발 중이라고 밝힌 '물·위생·위생(WASH) 조건의 표준화된 글로벌 모니터링' 제안 등이 여기에 포함된다.[79]다른 제안들에는 지역 사회, 문화, 재정적인 요인에 특화된 덜 동질적인 정책들뿐만 아니라 습한 시장에서 살아있는 동물 노점의 위생과 생물학적 유무를 감시하기 위한 새로운 제안된 신속한 평가 도구가 포함되어 있다.[81][82]

언론 보도

2020년 COVID-19 대유행의 첫 몇 달 동안, 중국 습윤 시장은 이 바이러스의 잠재적인 원천으로 언론에서 심한 비난을 받았다.[62]살아있는 동물 시장이나 야생 동물 시장만이 아니라 모든 습식 시장에 영구적인 전면 금지를 촉구하는 언론 보도는 야생 동물 시장에[11] 대한 감염 통제를 약화시키고 지역 공중 보건 위협으로부터 대중의 관심을 분산시킬 필요가 있다는 비판을 받아왔다.[39]일부 서구 언론은 위치 파악 없이 아시아 전역의 다른 시장에서의 노골적인 이미지를 사용하여 일반적인 습식 시장, 살아있는 동물 시장, 야생동물 시장을 구분하지 않고 습식 시장을 묘사했다.[83][11][25][84]이러한 묘사는 다른 언론인과 인류학자들로부터 선정적이고 과장된 동양주의자라는 비판을 받아왔으며, 시노포비아와 "중국인의 다른 점"을 부채질하고 있다.[11][25][38][39][84]

전 세계

2019년 관광 소셜 네트워크 데이터에 따르면 아시아에서 가장 집중도가 높은 시장이 전 세계에 있으며, 유럽, 북미 순으로 습윤 시장이 있다.[85]

아프리카

에티오피아

농업 가치 사슬에 대한 2013년 연구에 따르면, 에티오피아 전체 소득 집단의 약 90%가 젖은 시장에서 현지 정육점을 통해 쇠고기를 구입한다고 한다.[86][87]

케냐

케냐에서 가장 흔한 농업 공급망은 농부들이 그들의 농산물을 수집가들에게 파는 것을 포함한다. 수집가들은 그 농산물을 젖은 시장의 소매상들에게 판다.[88]나이로비와 키수무 주변 지역을 대상으로 한 2006년 조사 결과, 농가의 21%가 수집가에게, 17%는 도매상에게, 14%는 젖은 시장 상인들에게 직접 판매된 것으로 나타났다.[88]수집가들과 도매상들 둘 다 그들의 생산재고를 젖은 시장 상인들에게 주로 팔았다.[88]연구에 참여한 습식 시장의 고객들은 주로 최종 소비자였지만, 습식 시장의 적은 점유율은 식당에도 판매되었다.[88]

나이지리아

2011년 미국 농무청 보고서에 따르면 나이지리아의 전통적인 노천 습윤 시장의 고객 대부분은 저소득 및 중산층 소비자들이다.[89]

2008년부터 2009년까지 식품안전 연구진이 이바단 소재 보디자 시장의 습식시장 구간에서 소규모 도축업자들과 함께 적극적인 식품안전 실천과 피어투피어 교육을 추진하는 이니셔티브를 시작했다.[90][91]그 시책은 20퍼센트 더 많은 고기 샘플이 허용 가능한 품질로 이어졌다.[90][91]같은 정육점 집단에 대한 2019년 추적조사 결과, 정육점 상당수가 식품안전 관행을 기억하고 있지만, "정육점 중 유통된 재료가 고갈된 후에도 계속 구입해 교체한다고 보고한 사람은 한 명도 없었다"[90]는 결과가 나왔다.후속 연구 결과 2018년 미생물 위생상태가 2008~2009년 개입 이전보다 더 심각했던 것으로 나타났다.[90]

2014년에는 비위생적인 육류 취급 관행에 따라 보디자시장 습식시장 구간의 도축장 사용허가가 취소되기도 했다.[90][92]그 자리에 지방정부는 민관협력을 통해 아키니예레 아모순마을에 이바단 중앙아바투아르를 개원했다.[90][92]새 시설은 2014년 민관협력을 통해 육류 도축·가공을 위한 현대식 시설을 갖추고 있으며, 육류판매업자 1000명을 위한 노점 15ha, 행정건물, 진료소, 구내식당, 냉방실, 소각토 등으로 구성돼 서아프리카 최대 규모의 육류시설 중 하나이다.r.[90] 2018년 6월 지방 신문들은 보디자 시장 아바토르에서 치안팀이 지방 정부의 지시에 따라 이바단 아바토르 강제 이전을 강행하려다 5명이 사망했다고 보도했다.[90][93]

우간다

우간다에서 가장 흔한 농업 공급망은 농부들이 그들의 농산물을 도매상들에게 파는 것을 포함한다. 도매상들은 다시 젖은 시장의 소매상들에게 판다.[88]캄팔라와 음발레 주변 지역을 대상으로 한 2006년 조사 결과 농가의 51%는 도매상에게, 18%는 젖은 시장 상인에게 직접 판매된 것으로 나타났으며, 34%는 젖은 시장 상인에게 판매된 것으로 나타났다.[88]연구에 참여한 습식 시장의 고객들은 주로 최종 소비자였지만, 습식 시장의 적은 점유율은 식당에도 판매되었다.[88]

아메리카

브라질

브라질에서는 젖은 시장에 대한 규제가 시 차원에서 처리된다.[94][95][96]브라질 전역에는 규제가 매우 다양하며, 일부 자치단체에서는 습식 시장을 금지하는 구역 지정 규정이 있다.[94][95]

2003년의 한 연구는 습식 시장이 전체 식품 소매 시장 점유율이 75%[96]인 슈퍼마켓에 대한 식품 소매 시장에서 우위를 잃고 있다는 것을 발견했다.브라질의 전통적인 식품 소매점들에 비해 슈퍼마켓의 이익은 육류와 해산물 소매점에서 주로 나타났으며, 슈퍼마켓의 신선한 육류 및 해산물 시장 점유율은 대개 신선한 과일과 야채 시장 점유율보다 3배나 높았다.[96]

콜롬비아

2010년 미국 농무부 보고서에 따르면 콜롬비아의 각 작은 마을에는 일반적으로 지역 생산으로 공급되고 일주일에 적어도 한 번은 문을 여는 습윤 시장이 있다.[97]보고서는 '맘팝 매장'에 식자재를 공급하는 소매물시장과 도매물시장 모두에 대해 설명했다.[97]그것은 습식 시장의 수를 약 2,000개로 추정했지만 보고타에 있는 와 같은 대형 습식 시장이 존재함에도 불구하고 대도시에서는 그 수가 서서히 감소하고 있다고 지적했다.[97]

목장

그린란드에서는, 브레터로 알려진 지역 습윤 시장이 바다표범 고기, 고래 고기, 순록 고기, 북극곰 고기를 포함한 야생 동물들의 음식을 판다.[98]브레터는 살아있는 동물을 팔지 않지만, 브레터로 파는 대부분의 고기는 신선하고 최근에 도축된 것이다.[98]더 큰 도시들이 목적에 맞게 지어진 시설을 가지고 있는 반면, 작은 마을과 마을 정착촌의 사람들은 수돗물이나 전기 없이 야외 판매대에서 해산물을 판다.[99]그린란드 정부가 칼랄라라라크에서 건조 및 소금에 절인 고기 판매를 허용하기 시작한 2018년까지 그린란드 최대 신선식품 시장인 칼랄라라라크 시장의 누크에서는 신선육만 판매할 수 있었다.[98]

삼차증은 야생 북극곰 고기의 소비로 인해 그린란드에서 흔한 문제다.[98][100]2016년에는 현지 브레터로부터 북극곰 고기를 먹다가 트라이치넬라 회충에 감염돼 고기가 처음 검사를 통과했음에도 여러 명이 감염됐다.[98][100]2017년 현재 브뤼터 지역에서 판매되는 바다표범과 북극곰 고기에 대한 트리치넬라 검사는 의무사항이 아니다.[98]

멕시코

오악사카의 메르카도 마르가리타 마자 데 후아레스 등 멕시코 전통 노천시장 일부(tianguis)는 습시장(zona houmeda)과 건시장(zona seca)으로 분리되어 있다.[101]2002년 한 연구는 멕시코 소비자, 특히 중산층 소비자들이 전통적인 습윤 시장과는 반대로 쇠고기 구매를 위해 슈퍼마켓을 점점 더 선호하는 추세를 관찰했다.[102][103]2014년, 멕시코 쇠고기 소매에 대한 연구도 전통적인 풀서비스 습식 시장에서 슈퍼마켓의 셀프서비스 육류 진열장으로의 지속적인 전환에 주목했다.[103]

멕시코에서는 전통적 유통업체와 현대적 유통업체 간의 갈등이 시와 주 차원에서 처리되고 있다.[94]멕시코시티와 모렐리아 등 일부 지역 구역제 규정은 습식 시장이 소매업자들에게 추가 지원을 하지 않고 도시 지역에서 운영되는 것을 금지하고 있다.[94][95]

미국

2020년 4월, 더 힐은 미국에서 습식 시장이 여전히 운영되고 있으며, 동물 권리 운동가들이 살아 있는 동물 시장과 공장 농장을 폐쇄하라는 기존 요구 외에도 습식 시장의 폐쇄를 요구하고 있다고 보고했다.[104]

20세기에 냉장고가 보편화되기 전까지는 습식 시장은 뉴욕에서 흔했다.[45]1990년대부터 2020년까지 뉴욕시의 살아있는 동물 습식 시장의 수는 거의 두 배가 되었다.[45]2020년 현재 뉴욕에는 살아있는 동물을 비축해 놓고 고객을 위해 온디맨드 방식으로 도살하는 습식시장이 80곳이 넘는다.[45][104]그들은 대부분 문화적으로 중요하고 야생동물 시장이나 다른 종류의 이국적인 습식 시장에 비해 공공의 건강 위험이 낮은 외곽의 이민자 커뮤니티에 위치한 가금류 시장이다.[45]

아시아

중국

1990년대 이후 중국 전역의 대도시들은 전통적인 옥외 습식 시장을 현대적인 실내 시설로 옮겨왔다.[47][1]2018년 현재, 습식 시장은 1990년대 이후 슈퍼마켓 체인의 증가에도 불구하고 중국 도시 지역에서 가장 보편적인 식품 배출구로 남아있다.[105]2010년대에는 전통적인 습식시장이 할인점과의 경쟁에 직면하면서 전자결제 단말기를 갖춘 '스마트 마켓'이 등장하였다.[106]습식 시장도 알리바바의 헤마 점포와 같은 온라인 식료품점과의 경쟁에 직면하기 시작했다.[20]

야생동물의 거래는 중국, 특히 대도시에서는 흔하지 않으며,[20] 중국의 대부분의 습한 시장에는 수조에 든 물고기 외에 살아있는 동물이나 야생동물을 포함하지 않는다.[107]1980년대 초 중국 경제개혁 아래 소규모 야생동물 농사가 시작됐다.[108]1990년대 정부 지원으로 전국으로 확대되기 시작했으나 주로 동남권에 집중되었다.[108]2003년 중국 전역의 젖은 시장은 2002-2004년 사스 사태 이후 야생 생물을 보유하는 것이 금지되었는데, 이는 이러한 관행에 직결되었다.[33]중국의 불법 야생동물 거래는 식품이나 의약품보다는 모피로 주로 이루어졌지만 일부 규제가 허술한 중국 습식시장은 금지 조치 이후 야생동물 거래업계를 위한 배출구를 제공했다.[20][16][108]우한 화난수산물도매시장은 초기 사례집결로 인해 COVID-19의 발원지와 연계되어 2020년 추가 제한과 시행으로 이어졌다.[109][58][16][29][110]2020년 4월 중국 정부는 야생동물 거래에 대한 규제를 더욱 강화할 계획을 발표했다.[20][16][108]

홍콩

중앙 집중화된 대형 습윤시장은 중앙시장이 개방된 1842년 5월 16일 이후 홍콩에 존재해왔다.[111]젖은 시장에는 나이든 주민, 소득이 낮은 주민, 홍콩 주민의 약 10%를 섬기는 가사 도우미가 가장 많이 찾는다.[112]대부분의 이웃들은 적어도 하나의 습한 시장을 가지고 있다.[20]습한 시장은 관광객들이 "진짜 홍콩을 보기" 위한 목적지가 되었다.[113]

2000년 이전에는 홍콩의 많은 습윤 시장이 도시 위원회(홍콩 섬과 구룡 내) 또는 지역 위원회(신 영토 내)에 의해 관리되었다.2000년부터 홍콩의 젖은 시장은 식품환경위생국(FEHD)의 규제를 받고 있다.[114][115]도축장 규정에 따르면 살아있는 소, 돼지, 염소, 양 또는 사람 소비를 위한 양에 대한 도축은 허가된 도축장에서 이루어져야 한다.[116] 홍콩의 어느 젖은 시장도 야생 동물이나 외래 동물을 보유하고 있지 않다.[20]

2018년에 FEHD는 74개의 습식 시장을 운영하여 약 13,070개의 좌석을 수용하였다.[114]또 홍콩 주택청은 21개 시장을, 민간 개발사는 약 99개(2017년)를 운영했다.[117]

인도

인도의 육류, 가금류, 해산물 산업은 주로 젖은 시장에 의존하고 있다.[118][119]식음료 뉴스에 따르면 국내 소비자들은 인도 습식시장의 대다수가 낡고 비위생적인 시설을 사용함에도 불구하고 가공육과 냉동육보다 습식시장에서 갓 잘라낸 고기를 선호한다.[120]

델리에서는 음식 소매 제도가 전통적인 비공식 식품 소매업 부문(웨트 마켓, 푸시카트, 키라나 "mom-and-pop" 매장), 임대 보조 소매업 협동조합, 정부 소유의 식품 유통 채널, 민간 현대 슈퍼마켓 등으로 구성되어 있다.[121]델리 습식 시장은 일반적으로 매일 정해진 시간에 그들의 농산물을 팔기 위해 함께 모여 있는 다수의 소규모 소매상들로 구성되어 있다.[121]2010년 델리 식품 소매업 연구에서는 소비자에게 판매되는 과일과 야채의 총 수량의 68~75%가 습식 시장 소매업자에 의해 유통된 것으로 나타났다.[121]같은 조사에서 델리의 518개 습식 시장 소매상들을 대상으로 소비자들을 대상으로 조사한 결과, 이들의 거래에는 최종 가격과 최초 공시가격의 평균 차이 3%에 그치는 등 비교적 적은 수의 거래가 포함된 것으로 나타났다.[121]

인도네시아

파사르(파사르 말람, 파사르 파기 포함)라고 불리는 전통적인 습윤 시장은 도시와 시골 모두에서 인도네시아 전역에서 찾아볼 수 있다.습한 시장은 쇼페와 토코피디아와 같은 전자상거래 회사들뿐만 아니라 슈퍼마켓들로부터 점점 더 많은 경쟁에 직면해 있다.[49]2020년 현재, 인도네시아의 13,450개의 젖은 시장에 걸쳐 1,230만 명의 상인들이 있다.[5]

2016년 인도네시아 정부의 쇠고기 가격 안정 정책은 수입업자들이 슈퍼마켓이나 대형마트 대신 젖은 시장에서 더 싼 가격의 고기를 팔도록 했다.[122]그레이터 자카르타에서는 2018년 현재 인도 버팔로 고기가 주로 젖은 시장에서 판매되고 있으며, 슈퍼마켓과 하이퍼마켓에서 시장 침투가 제한되어 있다.[122]이와는 대조적으로 2018년 자카르타의 소비자들 중 7%만이 슈퍼마켓에서 호주산 쇠고기를 구입한다.[122]2018년 상품을 수입하는 인도네시아 습윤시장 판매상들은 인도네시아 루피아 가치 하락에 우려를 나타냈다.[49]

인도네시아 전역의 습윤 시장은 정부 계획에 따라 2010년대에 대대적인 개조를 거쳤다.[123]2018년 자카르타에서 냉동·냉동시설뿐 아니라 실험실을 갖춘 최초의 근대 습윤시장이 문을 열었다.[49]전통시장 상인협회(IKAPPI)에 따르면 2020년 6월까지 인도네시아의 COVID-19 대유행으로 인한 보건 프로토콜과 이동성 제약으로 습한 시장 상인들의 매출이 65% 감소했다고 한다.[5]2020년 중반, 몇몇 지방의 습윤 시장은 COVID-19 사례의 주요 군집을 몇 가지 차지했다.[124]에어랑가 대학교가 2020년 5월부터 6월까지 실시한 조사에서 동자바 습식 시장의 사람들은 동자바에 있는 다른 공공장소에 비해 가장 덜 상대적인 사회적 거리 설정과 마스크 착용 등 건강 규약을 따르는 것으로 나타났다.[124]

말레이시아

말레이시아 정부는 2020년 3월 코로나바이러스 유행에 대한 국가적 대응 차원에서 모든 습시장(파사르말람, 파사르파기 포함)의 운영을 잠정적으로 금지했다.[125]

필리핀

필리핀에서는 습식시장이 협동조합법(RA 7160), 농림어업현대화법(RA 8435) 등의 법률에 따라 협동조합이 관리하고 있다.[126]필리핀 정부는 쌀과 같은 중요 식품, 특히 팰랭크로 판매되는 일부 상품의 가격을 통제하고 있다.[127][128]

2017년 7월 다바오시에서 디지털 습윤시장 팰렝케 보이(Palenke Boy)가 전통 습윤시장과 경쟁하기 위해 출범했다.[129]2020년 3월 파시그 지방정부는 COVID-19 대유행 시 기본 물품에 대한 접근을 보장하기 위해 이동 습윤시장을 개설했다.[130]

싱가포르

싱가포르의 젖은 시장은 정부로부터 보조금을 받는다.[49]테카 시장, 티옹 바루 시장, 차이나타운 복합 시장은 계절 과일, 신선한 야채, 수입 쇠고기, 살아있는 해산물이 있는 대표적인 습식 시장이다.[131]

1990년대 초 싱가포르의 12개 도심 시장과 22개 습식 시장 센터에서 동물 도살이 금지되었다.[132]국립환경청은 2020년 코로나바이러스 대유행 대응으로 감독하는 83개 시장에 대해 2020년 초 '높은 위생 및 청결 수준' 권고안을 내놨다.[44]

스리랑카

가금류가 축산업을 선도하고 유일한 육류 수출산업에 해당하는 스리랑카에서 대부분의 닭구이기는 반자동식물로 기계적으로 가공된다.그러나, 가금류는 일반적으로 특정한 고객 집단과 인종 집단의 요구를 만족시키는 젖은 시장에서 여전히 도살되고 있다.[133]2017년 반자동가금처리장 102개소와 가금류 살처분 습식시장 25개소를 대상으로 조사한 결과 반자동가금처리시설에서 채취한 굽는 목 피부 검체의 27.4%가 캄필로박터 오염 양성반응을 보인 반면, 습식시장 가공시설에서 채취한 굽는 목 피부 검체의 48%는 카에 양성반응을 보인 것으로 나타났다.mpylobacter [133]오염

타이완

대만의 많은 습한 시장은 행상인과 노점상들이 비공식적인 물리적 구조로 조직되면서 생겨났다.[134]2020년까지, 젖은 시장은 수십 년 동안 대만 전역에서 감소해 왔고, 활성화 노력은 대부분 성공하지 못했다.[134]

1997년, 타이베이 시 정부의 보고서에 따르면 타이베이에는 61개의 주요 습윤 시장이 있으며 거의 1만 개의 등록된 판매상들이 있다고 한다.[135]이 보고서는 또한 도시의 젖은 시장 대부분이 심각한 수리를 필요로 하고 있으며 거의 3,500개의 노점들이 공석으로 놓여 있다고 지적했다.[135]타이베이 난먼 정부 소유의전통 습윤시장이다 일제강점기인 1907년 개장한 시장은.[50][135]시장건물은 2019년 10월 철거됐으며 시장은 2022년 교체 현대식 12층 건물이 완공될 때까지 임시 이전했다.[50]

대만 최대 습윤시장 중 하나인 타이중 진구오 시장은 2016년 철거되고 새로운 시설로 교체됐다.[134]새로운 시설들은 더 나은 위생, 장애 접근성, 그리고 냉장고를 제공했지만, 처음에 이 이전은 풀뿌리 운동으로 더 큰 수용으로 이어지기 전에 지역 상인들의 망설임에 직면했다.[134]

태국.

젖은 시장은 태국에서 신선식품에 대한 현지인들의 선호도,[136] 저렴한 가격과 가게 주인들과의 친숙함 때문에 식료품 쇼핑을 선호하는 지배적인 장소다.[49]

아랍에미리트

2018년 10월, 미트앤축산물 호주 보고서는 아랍에미리트의 식료품 소매 분야가 고도로 발달되어 있지만, 습식 시장은 여전히 전국적으로 두드러지고 있다고 밝혔다.[122]

베트남

정부 추산에 따르면 2017년에는 베트남 전역에 약 9,000개의 젖은 시장, 800개의 슈퍼마켓, 160개의 쇼핑몰, 130만 개의 소규모 가족 소유의 가게가 있었다.[137]

하노이시는 2017년 도시의 습식시장을 개조해 현대식 쇼핑몰로 탈바꿈시킬 계획이었다.[137]이 계획은 고급 쇼핑센터 지하로 이전된 다른 시장의 매출 수치가 크게 감소하자 젖은 시장 판매자들의 반발에 부딪혔다.[137]

2020년 베트남 응우옌 쉬앙푸크 총리는 베트남에서 야생동물 거래를 금지하자는 제안을 발표했다.[37]

유럽

프랑스.

1969년 만들어진 프랑스 룽지스 국제시장은 룽지프랑스 내외의 식품을 판매하면서 유럽 전역에서 가장 큰 신선식품 시장이다.[138]세계에서 가장 큰 도매 식품 시장,[139] 그리고 아마도 가장 큰 신선 식품 시장일지라도 [140]양과[141] 장어를 포함한 다양한 음식이 제공된다.[142]1972년까지 매일 6000톤의 과일과 채소가 시장에 출하되었다.[143]

이탈리아

북서부 도시 토리노에 있는 포르타 팔라초 시장은 유럽에서 가장 큰 거리 시장으로,[144] 약 100여 개의 신선식품 생산자들이 토리노의 역사적인 지역에서 계절의 절정에 그들의 상품을 판매하고 있다.[145]시장의 그것들과 함께 일하는 토리노 당국은 세계 각국의 요리를 특징으로 하는 다문화 공간이자 관광지로써 시장에 대한 대중의 인식을 재구성하려고 점점 더 시도하고 있다.[146]

아일랜드

아일랜드 더블린의 이베아 마켓은 옷을 파는 건식 시장과 생선, 과일, 야채 등을 파는 습식 시장으로 나뉘었던 실내 시장이었다.[147][148][149]그 시장은 1906년부터 운영되었고 1980년대까지 황폐화되었다.[148][149]1990년대에 문을 닫은 마지막 노점은 2018년 현재 부지를 새로운 식품 시장 단지로 재개발하려는 시도가 실패했음에도 불구하고 여전히 방치되어 있다.[148][149][147]

오세아니아

호주.

2020년 SBS는 호주에서 습식시장이 한때 흔했고 시간이 지나면서 점차 폐쇄돼 아바토르가 중앙집중화돼 도시에서 멀어졌다고 보도했다.[150]로 국제 사회의 요구를 반영한 젖은 시장 재래 시장을 금지하도록 Media매체 데일리 수성과 헤럴드 태양뿐만 아니라 농림부 장관 데이비드 Littleproud과 지도자는 노동당 앤서니 알바네제의, 그리고 호주에서는 시장은 시드니 수산 시장과 멜버른 시장과 같은, 다양한 신선한 육류, 해산물을 설명하였습니다.[151][152][153][154]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Zhong, Taiyang; Si, Zhenzhong; Crush, Jonathan; Scott, Steffanie; Huang, Xianjin (2019). "Achieving urban food security through a hybrid public-private food provisioning system: the case of Nanjing, China". Food Security. 11 (5): 1071–1086. doi:10.1007/s12571-019-00961-8. ISSN 1876-4517. S2CID 199492034.

- ^ a b c d Morales, Alfonso (2009). "Public Markets as Community Development Tools". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 28 (4): 426–440. doi:10.1177/0739456X08329471. ISSN 0739-456X. S2CID 154349026.

- ^ a b c d Morales, Alfonso (2011). "Marketplaces: Prospects for Social, Economic, and Political Development". Journal of Planning Literature. 26 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/0885412210388040. ISSN 0885-4122. S2CID 56278194.

- ^ [1][2][3]

- ^ a b c Atika, Sausan (15 June 2020). "Indonesian wet markets carry high risk of virus transmission". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Lin, Bing; Dietrich, Madeleine L; Senior, Rebecca A; Wilcove, David S (June 2021). "A better classification of wet markets is key to safeguarding human health and biodiversity". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (6): e386–e394. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00112-1. ISSN 2542-5196. PMID 34119013.

- ^ 도매시장 : 기획 및 디자인 매뉴얼(파오농업서비스 게시판) (90호)

- ^ a b "wet, adj". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

wet market n. South-East Asian a market for the sale of fresh meat, fish, and produce

- ^ a b Brown, Allison (2001). "Counting Farmers Markets". Geographical Review. 91 (4): 655–674. doi:10.2307/3594724. JSTOR 3594724.

- ^ [7][8][9]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lynteris, Christos; Fearnley, Lyle (2 March 2020). "Why shutting down Chinese 'wet markets' could be a terrible mistake". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Standaert, Michael (15 April 2020). "'Mixed with prejudice': calls for ban on 'wet' markets misguided, experts argue". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Dalton, Jane (2 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Indian street traders 'risking human health by slaughtering goats, lambs and chickens in squalid conditions'". The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ [1][11][12][13]

- ^ a b c "Why Wet Markets Are The Perfect Place To Spread Disease". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Standaert, Michael (15 April 2020). "'Mixed with prejudice': calls for ban on 'wet' markets misguided, experts argue". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ [1][15][11][16]

- ^ a b Woo, Patrick CY; Lau, Susanna KP; Yuen, Kwok-yung (2006). "Infectious diseases emerging from Chinese wet-markets: zoonotic origins of severe respiratory viral infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 19 (5): 401–407. doi:10.1097/01.qco.0000244043.08264.fc. ISSN 0951-7375. PMC 7141584. PMID 16940861.

- ^ a b Wan, X.F. (2012). "Lessons from Emergence of A/Goose/Guangdong/1996-Like H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses and Recent Influenza Surveillance Efforts in Southern China: Lessons from Gs/Gd/96-like H5N1 HPAIVs". Zoonoses and Public Health. 59: 32–42. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01497.x. PMC 4119829. PMID 22958248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Westcott, Ben; Wang, Serenitie (15 April 2020). "China's wet markets are not what some people think they are". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ [18][19][20]

- ^ "Study on the Way Forward of Live Poultry Trade in Hong Kong" (PDF). Food and Health Bureau. March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Rahman, Khaleda (28 March 2020). "PETA launches petition to shut down live animal markets that breed diseases like COVID-19". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Reardon, Thomas; Timmer, C. Peter; Minten, Bart (31 July 2012). "Supermarket revolution in Asia and emerging development strategies to include small farmers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12332–12337. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912332R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003160108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3412023. PMID 21135250.

- ^ a b c d e f Samuel, Sigal (15 April 2020). "The coronavirus likely came from China's wet markets. They're reopening anyway". Vox. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ [15][16][23][24][25]

- ^ [1][2][3]

- ^ a b Yu, Verna (16 April 2020). "What is a wet market?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

While “wet markets”, where water is sloshed on produce to keep it cool and fresh, may be considered unsanitary by western standards, most do not trade in exotic or wild animals and should not be confused with “wildlife markets” – now the focus of vociferous calls for global bans.

- ^ a b c d Maron, Dina Fine (15 April 2020). "'Wet markets' likely launched the coronavirus. Here's what you need to know". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Hui, Mary (16 April 2020). "Wet markets are not wildlife markets, so stop calling for their ban". Quanta Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b Suen, Thomas; Goh, Brenda (12 April 2020). "Wet markets in China's Wuhan struggle to survive coronavirus blow". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

That has prompted heavy scrutiny for wet markets, a key facet of China’s daily life, even though only a few sell wildlife. Some U.S. officials have called for them, and others across Asia, to be closed.

- ^ [28][29][30][31]

- ^ a b c Yu, Sun; Liu, Xinning (23 February 2020). "Coronavirus piles pressure on China's exotic animal trade". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b Karesh WB, Cook RA, Bennett EL, Newcomb J (July 2005). "Wildlife trade and global disease emergence". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1000–2. doi:10.3201/eid1107.050194. PMC 3371803. PMID 16022772.

- ^ [15][33][34][35]

- ^ a b Reed, John (19 March 2020). "The economic case for ending wildlife trade hits home in Vietnam". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b Palmer, James (27 January 2020). "Don't Blame Bat Soup for the Coronavirus". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Boyle, Louise (15 May 2020). "Wet markets are not the problem – focus on the billion-dollar international trade in wild animals, experts say". The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ [11][38][39]

- ^ a b Tan, Alvin (2013). Wet Markets (PDF). Community Heritage Series. Vol. II. Singapore: National Heritage Board. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "New Singapore English words". Oxford University Press. 2016. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b Burton, Dawn (2008). Cross-Cultural Marketing: Theory, Practice and Relevance. Routledge. p. 146. ISBN 9781134060177.

- ^ a b c d Chandran, Rina (7 February 2020). "Traditional markets blamed for virus outbreak are lifeline for Asia's poor". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f de Greef, Kimon (17 June 2020). "'People fear what they don't know': the battle over 'wet' markets, a vital part of culinary culture". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Shaheen, Therese (19 March 2020). "The Chinese Wild-Animal Industry and Wet Markets Must Go". National Review. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ a b Hu, Dong-wen; Liu, Chen-xing; Zhao, Hong-bo; Ren, Da-xi; Zheng, Xiao-dong; Chen, Wei (2019). "Systematic study of the quality and safety of chilled pork from wet markets, supermarkets, and online markets in China". Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 20 (1): 95–104. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1800273. ISSN 1673-1581. PMC 6331336. PMID 30614233.

- ^ Zhong, Shuru; Crang, Mike; Zeng, Guojun (2020). "Constructing freshness: the vitality of wet markets in urban China". Agriculture and Human Values. 37 (1): 175–185. doi:10.1007/s10460-019-09987-2. ISSN 0889-048X.

- ^ a b c d e f Roughneen, Simon (8 October 2018). "Southeast Asia's traditional markets hold their own". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Nanmen Market to close for renovation after 38 years". Focus Taiwan. 6 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Agricultural Trade Highlights. Foreign Agricultural Service. 1994. p. 12.

- ^ Bougoure, Ursula; Lee, Bernard (2009). Lindgreen, Adam (ed.). "Service quality in Hong Kong: wet markets vs supermarkets". British Food Journal. 111 (1): 70–79. doi:10.1108/00070700910924245. ISSN 0007-070X.

- ^ Mele, Christopher; Ng, Megan; Chim, May Bo (2015). "Urban markets as a 'corrective' to advanced urbanism: The social space of wet markets in contemporary Singapore". Urban Studies. 52 (1): 103–120. doi:10.1177/0042098014524613. ISSN 0042-0980. S2CID 154733767.

- ^ a b "Fresh Meat". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 25 November 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "New Coronavirus 'Won't Be the Last' Outbreak to Move from Animal to Human". Goats and Soda. NPR. 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Calls for global ban on wild animal markets amid coronavirus outbreak". The Guardian. London. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Borzée, Amaël; McNeely, Jeffrey; Magellan, Kit; Miller, Jennifer R.B.; Porter, Lindsay; Dutta, Trishna; Kadinjappalli, Krishnakumar P.; Sharma, Sandeep; Shahabuddin, Ghazala; Aprilinayati, Fikty; Ryan, Gerard E.; Hughes, Alice; Abd Mutalib, Aini Hasanah; Wahab, Ahmad Zafir Abdul; Bista, Damber; Chavanich, Suchana Apple; Chong, Ju Lian; Gale, George A.; Ghaffari, Hanyeh; Ghimirey, Yadav; Jayaraj, Vijaya Kumaran; Khatiwada, Ambika Prasad; Khatiwada, Monsoon; Krishna, Murali; Lwin, Ngwe; Paudel, Prakash Kumar; Sadykova, Chinara; Savini, Tommaso; Shrestha, Bharat Babu; Strine, Colin T.; Sutthacheep, Makamas; Wong, Ee Phin; Yeemin, Thamasak; Zahirudin, Natasha Zulaika; Zhang, Li (2020). "COVID-19 Highlights the Need for More Effective Wildlife Trade Legislation". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV. 35 (12): 1052–1055. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.10.001. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 7539804. PMID 33097287.

- ^ a b c Fujiyama, Emily Wang; Moritsugu, Ken (11 February 2021). "EXPLAINER: What the WHO coronavirus experts learned in Wuhan". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Hui, David S.; I Azhar, Esam; Madani, Tariq A.; Ntoumi, Francine; Kock, Richard; Dar, Osman; Ippolito, Giuseppe; Mchugh, Timothy D.; Memish, Ziad A.; Drosten, Christian; Zumla, Alimuddin; Petersen, Eskild (2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier BV. 91: 264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. ISSN 1201-9712. PMC 7128332. PMID 31953166.

- ^ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (24 January 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ^ Keevil, William; Lang, Trudie; Hunter, Paul; Solomon, Tom (24 January 2020). "Expert reaction to first clinical data from initial cases of new coronavirus in China". Science Media Centre. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b Spinney, Laura (28 March 2020). "Is factory farming to blame for coronavirus?". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Most of the attention so far has been focused on the interface between humans and the intermediate host, with fingers of blame being pointed at Chinese wet markets and eating habits,...

- ^ "China's Wet Markets, America's Factory Farming". National Review. 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Building a factory farmed future, one pandemic at a time". grain.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ info@sustainablefoodtrust.org, Sustainable Food Trust-. "Sustainable Food Trust". Sustainable Food Trust. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b Fickling, David (3 April 2020). "China Is Reopening Its Wet Markets. That's Good". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- ^ "China Could End the Global Trade in Wildlife". Sierra Club. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus expert calls for shut down of Asia's wildlife markets". Nine News Australia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Wild Animal Markets Spark Fear in Fight Against Coronavirus". Time. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Africa Risks Virus Outbreak From Wildlife Trade". WildAid. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "A sea change in China's attitude towards wildlife exploitation may just save the planet". Daily Maverick. 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Knights hoped China would also play a role to help “countries around the world. It’s no good simply banning the trade in China. The same risks are very much out there in Asia as well as Africa.”

- ^ "Crackdown on wet markets and illegal wildlife trade could prevent the next pandemic". Mongabay India. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

...what we do know is that wet markets such as Wuhan, and for that matter Agartala’s Golbazar or the thousands such that exist in Asia and Africa allow for easy transmission of viruses and other pathogens from animals to humans.

- ^ Mekelburg, Madlin. "Fact-check: Is Chinese culture to blame for the coronavirus?". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Forgey, Quint (3 April 2020). "'Shut down those things right away': Calls to close 'wet markets' ramp up pressure on China". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Fortier-Bensen, Tony (9 April 2020). "Sen. Lindsey Graham, among others, urge global ban of live wildlife markets and trade". ABC News. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Beech, Peter (18 April 2020). "What we've got wrong about China's 'wet markets' and their link to COVID-19". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Forrest, Adam (13 April 2021). "WHO calls for ban on sale of live animals in food markets to combat pandemics". The Independent. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b Nadimpalli, Maya L; Pickering, Amy J (2020). "A call for global monitoring of WASH in wet markets". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (10): e439–e440. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30204-7. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7541042. PMID 33038315.

- ^ Petrikova, Ivica; Cole, Jennifer; Farlow, Andrew (2020). "COVID-19, wet markets, and planetary health". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (6): e213–e214. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(20)30122-4. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7832206. PMID 32559435.

- ^ a b Barnett, Tony; Fournié, Guillaume (January 2021). "Zoonoses and wet markets: beyond technical interventions". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (1): e2–e3. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30294-1. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7789916. PMID 33421407.

- ^ Soon, Jan Mei; Abdul Wahab, Ikarastika Rahayu (1 September 2021). "On-site hygiene and biosecurity assessment: A new tool to assess live bird stalls in wet markets". Food Control. 127: 108108. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108108. ISSN 0956-7135.

- ^ "Wuhan Is Returning to Life. So Are Its Disputed Wet Markets". Bloomberg Australia-NZ. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b St. Cavendish, Christopher (11 March 2020). "No, China's fresh food markets did not cause coronavirus". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Kogan, Nicole E; Bolon, Isabelle; Ray, Nicolas; Alcoba, Gabriel; Fernandez-Marquez, Jose L; Müller, Martin M; Mohanty, Sharada P; Ruiz de Castañeda, Rafael (2019). "Wet Markets and Food Safety: TripAdvisor for Improved Global Digital Surveillance". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 5 (2): e11477. doi:10.2196/11477. ISSN 2369-2960. PMC 6462893. PMID 30932867.

- ^ Gómez, Miguel I.; Ricketts, Katie D. (2013). "Food value chain transformations in developing countries: Selected hypotheses on nutritional implications" (PDF). Food Policy. 42: 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.06.010.

- ^ "Improving diets in an era of food market transformation: Challenges and opportunities for engagement between the public and private sectors" (PDF). Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition policy brief. April 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weinberger, Katinka; Pasquini, Margaret; Kasambula, Phyllis; Abukutsa-Onyango, Mary (2011). "Supply Chains for Indigenous Vegetables in Urban and Peri-urban Areas of Uganda and Kenya: a Gendered Perspective". In Mithöfer, Dagmar; Waibel, Hermann (eds.). Vegetable Production and Marketing in Africa: Socio-economic Research. Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. pp. 169–181. ISBN 9781845936495.

- ^ "Strong Growth Persists in Nigeria's Wine Market" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 1 July 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

More wine and spirits are now sold to the consumers and re-sellers through the wholesalers located in the traditional open wet markets (mostly patronized by the low and middle income consumers).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grace, Delia; Dipeolu, Morenike; Alonso, Silvia (2019). "Improving food safety in the informal sector: nine years later". Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. 9 (1): 1579613. doi:10.1080/20008686.2019.1579613. ISSN 2000-8686. PMC 6419621. PMID 30891162.

- ^ a b Grace, Delia (October 2015). "Food Safety in Developing Countries:An Overview" (PDF). International Livestock Research Institute. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b Oluwole, Josiah (27 June 2018). "Oyo govt begins crackdown on illegal abattoirs in Ibadan". Premium Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "5 dead, station razed as police clash with butchers in Ibadan". Vanguard. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Making Retail Modernisation in Developing Countries Inclusive". Discussion Paper. 2/2016. German Development Institute. 2016.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널은 필요로 한다.journal=(도움말) - ^ a b c Reardon, Thomas; Gulati, Ashok (2008). "The Rise of Supermarkets and Their Development Implications". International Food Policy Research Institute Discussion Paper.

- ^ a b c Reardon, Thomas; Timmer, C. Peter; Barrett, Christopher B.; Berdegué, Julio (2003). "The Rise of Supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 85 (5): 1140–1146. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00520.x. ISSN 0002-9092.

- ^ a b c "Colombia Retail Food Sector" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 6 October 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Hofverberg, Elin (31 December 2020). "Greenland". Regulation of Wild Animal Wet Markets (PDF) (Report). Library of Congress. pp. 49–53. LL File No. 2020-019215. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Resources and industry". Government of Greenland. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Sådan undgår du at blive smittet med trikiner!". Naalakkersuisut (in Danish). 12 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Central de Abasto: bomba de tiempo y nido de delincuencia". El Imparcial (Oaxaca). 9 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Anderson, D.; Kerr, W.A.; Sanchez, G.; Ochoa, R. (2002). "Cattle/beef subsector's structure and competition under free trade". In Loyns, R.M.A.; Meilke, K.; Knutson, R.D.; Yunez-Naude, A. (eds.). Structural changes as a source of trade disputes under NAFTA. Proceedings of the Seventh Agricultural and Food Policy Systems Information Workshop. Winnipeg, Canada: Friesens. pp. 231–258.

- ^ a b Huerta-Leidenz, Nelson; Ruíz-Flores, Agustín; Maldonado-Siman, Ema; Valdéz, Alejandra; Belk, Keith E. (2014). "Survey of Mexican retail stores for US beef product". Meat Science. 96 (2): 729–736. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.10.008. PMID 24200564.

- ^ a b Srikanth, Anagha (21 April 2020). "America has dozens of live animal 'wet' markets — and Joaquin Phoenix is calling for them to be banned because of coronavirus". The Hill. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Zhong, Taiyang; Si, Zhenzhong; Crush, Jonathan; Xu, Zhiying; Huang, Xianjin; Scott, Steffanie; Tang, Shuangshuang; Zhang, Xiang (2018). "The Impact of Proximity to Wet Markets and Supermarkets on Household Dietary Diversity in Nanjing City, China". Sustainability. 10 (5): 1465. doi:10.3390/su10051465. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Jia, Shi (31 May 2018). "Regeneration and reinvention of Hangzhou's wet markets". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ [11][16][29][30][31][66]

- ^ a b c d Pladson, Kristie (25 March 2021). "Coronavirus: A death sentence for China's live animal markets". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "COVID-19: What we know so far about the 2019 novel coronavirus". Archived from the original on 5 February 2020.

- ^ Gorman, James (27 February 2020). "China's Ban on Wildlife Trade a Big Step, but Has Loopholes, Conservationists Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "The Friend Of China, and Hong Kong Gazette" (PDF). 12 May 1842. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "EmeraldInsight". EmeraldInsight.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Chong, Sei (18 March 2011). "A Guide to Hong Kong's Wet Markets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Chapter IV – Environmental Hygiene". Annual Report 2018. Food and Environmental Hygiene Department. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Report No. 51 of the Director of Audit — Chapter 6" (PDF). Audit Commission. November 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Cap. 132BU Slaughterhouses Regulation". Hong Kong e-Legislation. Department of Justice.

- ^ "Public markets" (PDF). Legislative Council Secretariat. 27 September 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Goyal, Malini (9 September 2018). "International food giant Cargill is changing the way it does business". The Economic Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

Even the meat market in India is largely a wet market -a market selling fresh meat, fish and other such produce — and has small, unorganised players.

- ^ Ghosal, Sutanuka (4 April 2018). "ICRA predicts decent growth for domestic poultry industry". The Economic Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Mane, B. G. (16 April 2012). "Status and prospects of Indian meat industry". Food & Beverage News. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Minten, Bart; Reardon, Thomas; Sutradhar, Rajib (2010). "Food Prices and Modern Retail: The Case of Delhi". World Development. 38 (12): 1775–1787. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.585.2560. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.04.002.

- ^ a b c d "Global Market Snapshot" (PDF). Meat & Livestock Australia. October 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Amindoni, Ayomi (30 April 2016). "Jokowi wants traditional markets to compete with shopping malls". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b Maulia, Erwida; Damayanti, Ismi (13 July 2020). "Jakarta raises alarm as COVID-19 cases keep rising in Indonesia". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Negri hawkers, food trucks to operate 7am-8pm from March 24". The Star. 22 March 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Pabico, Alecks P. (2002). "Death of the Palengke". Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Napallacan, Jhunnex (28 March 2008). "6 Cebu rice retailers suspended for violations". Breaking News / Regions. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Garcia, Bong (21 April 2007). "Food agency intensifies 'Palengke Watch'". Sun.Star Zamboanga. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Huang-Teves, Janette (7 September 2018). "Teves: Palengke Boy: The family's digital wet market buddy". Sun.Star. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Domingo, Katrina (26 March 2020). "Taking cue from Pasig, Valenzuela eyes own market-on-wheels amid quarantine". ABS-CBN Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Singapore wet markets: Reminder of bygone days". CNN. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ United States. Foreign Agricultural Service. Dairy, Livestock, and Poultry Division, United States. World Agricultural Outlook Board (1992). U.S. Trade and Prospects: Dairy, livestock, and poultry products. The Service. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint : 복수이름 : 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ a b Kottawatta, Kottawattage; Van Bergen, Marcel; Abeynayake, Preeni; Wagenaar, Jaap; Veldman, Kees; Kalupahana, Ruwani (2017). "Campylobacter in Broiler Chicken and Broiler Meat in Sri Lanka: Influence of Semi-Automated vs. Wet Market Processing on Campylobacter Contamination of Broiler Neck Skin Samples". Foods. 6 (12): 105. doi:10.3390/foods6120105. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 5742773. PMID 29186018.

- ^ a b c d Wei, Clarissa (4 December 2020). "How Taiwan's Largest Wet Market Was Torn Down and Came Back Stronger Than Ever". The News Lens. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Trappey, Charles V. (1 March 1997). "Are Wet Markets Drying Up?". Taiwan Today. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ de Mooij, Marieke (2003). Consumer Behavior and Culture: Consequences for Global Marketing and Advertising. Chronicle Books. p. 295. ISBN 9780761926689.

- ^ a b c Yen, Bao (12 June 2017). "A Hanoi wet market at the crossroads of modernity". VnExpress. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Aubry, Christine; Kebir, Leïla (August 2013). "Shortening food supply chains: A means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of Paris". Food Policy. 41: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.04.006.

- ^ Saskia, Seidel; Mareï, Nora; Blanquart, Corinne (2016). "Innovations in e-grocery and Logistics Solutions for Cities". Transportation Research Procedia. 12: 825–835. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2016.02.035.

- ^ Jlassi, Sarra; Tamayo, Simon; Gaudron, Arthur; de La Fortelle, Arnaud (July 2017). "Simulating impacts of regulatory policies on urban freight: application to the catering setting" (PDF). 2017 6th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Logistics and Transport (ICALT): 106–112. doi:10.1109/ICAdLT.2017.8547005. ISBN 978-1-5386-1623-9. S2CID 54438879.

- ^ Halos, Lénaïg; Thébault, Anne; Aubert, Dominique; Thomas, Myriam; Perret, Catherine; Geers, Régine; Alliot, Annie; Escotte-Binet, Sandie; Ajzenberg, Daniel; Dardé, Marie-Laure; Durand, Benoit; Boireau, Pascal; Villena, Isabelle (February 2010). "An innovative survey underlining the significant level of contamination by Toxoplasma gondii of ovine meat consumed in France". International Journal for Parasitology. 40 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.06.009. PMID 19631651.

- ^ Pasquier, Jérémy; Lafont, Anne-Gaëlle; Jeng, Shan-Ru; Morini, Marina; Dirks, Ron; van den Thillart, Guido; Tomkiewicz, Jonna; Tostivint, Hervé; Chang, Ching-Fong; Rousseau, Karine; Dufour, Sylvie (20 November 2012). "Multiple Kisspeptin Receptors in Early Osteichthyans Provide New Insights into the Evolution of This Receptor Family". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e48931. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748931P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048931. PMC 3502363. PMID 23185286.

- ^ Brayne, M. L. (1972). "Rungis: The New Paris Market". Geography. 57 (1): 47–51. ISSN 0016-7487. JSTOR 40567707.

- ^ Gilli, Monica; Ferrari, Sonia (4 March 2018). "Tourism in multi-ethnic districts: the case of Porta Palazzo market in Torino". Leisure Studies. 37 (2): 146–157. doi:10.1080/02614367.2017.1349828. S2CID 149121283.

- ^ Black, Rachel Eden (1 May 2005). "The Porta Palazzo farmers' market: local food, regulations and changing traditions". Anthropology of Food (4). doi:10.4000/aof.157.

- ^ Medina, F. Xavier (31 December 2013). "Porta Palazzo, Anthropology of an Italian Market". Anthropology of Food (S8). doi:10.4000/aof.7429.

- ^ a b "Dublin City Council to take possession of Iveagh Market". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 12 January 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Olivia (7 January 2015). "Work to begin on €90m redevelopment of Iveagh Markets". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Olivia (19 August 2017). "Call for Iveagh Markets to be returned to Dublin City Council". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Corsetti, Stephanie (9 April 2020). "What is a wet market and why are they allowed to continue amid the coronavirus crisis?". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Calls mount for investigation into 'dangerous' wet markets". Sky News Australia. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

What we’re talking about isn’t all wet markets, because the Sydney fish market is a wet market, what we’re talking about here is unregulated markets that engage in some exotic species that are dangerous

- ^ "Coronavirus: Australia wants wet market probe as China faces backlash". Herald Sun. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "How to prevent the next pandemic from wet markets". Daily Mercury. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

Australia also has wet markets - e.g. the Melbourne and Sydney Fish Market.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Australia urges G20 action on wildlife wet markets". BBC. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

Speaking to the ABC on Thursday, agriculture minister David Littleproud said he was not targeting all food markets. "A wet market, like the Sydney fish market, is perfectly safe," he said.

외부 링크

Wikimedia Commons의 Wet Market 관련 미디어

Wikimedia Commons의 Wet Market 관련 미디어