달 레이저 거리 측정 실험

Lunar Laser Ranging experimentLLR(Lunar Laser Ranging)은 레이저 범위를 사용하여 지구와 달 사이의 거리를 측정하는 연습이다.이 거리는 빛의 속도로 이동하는 레이저 광 펄스의 왕복 시간으로부터 계산될 수 있으며, 달 표면이나 아폴로 계획(11, 14, 15)과 루노호드 1호와 2호 [1]임무 중 달에 설치된 5개의 역반사기 중 하나에 의해 지구로 반사된다.

달 표면에서 직접 빛이나 전파를 반사할 수 있지만(EME로 알려진 과정), 역반사기를 사용하여 훨씬 더 정확한 범위를 측정할 수 있다. 왜냐하면 반사 신호의 시간적 확산이 훨씬 작기 때문이다.

달 레이저 렌징에 대한 리뷰를 [2]이용할 수 있습니다.

레이저 거리 측정은 [3][4]LRO와 같은 달 궤도 위성에 설치된 역반사기로도 가능합니다.

역사

최초의 달 거리 측정 실험은 1962년 매사추세츠 공과대학의 루이스 스물린과 조르지오 피오코가 50J 0.5밀리초의 펄스 [5]길이를 가진 레이저를 사용하여 달 표면에서 반사되는 레이저 펄스를 관측하는 데 성공하면서 이루어졌다.같은 해 말 크림 천체물리 관측소의 소련 팀이 Q 교환 루비 [6]레이저를 사용해 비슷한 측정치를 얻었다.

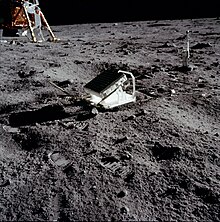

그 직후 프린스턴 대학 대학원생 제임스 팰러는 [7]측정의 정확성을 높이기 위해 달에 광학 반사체를 설치할 것을 제안했다.이것은 1969년 7월 21일 아폴로 11호의 승무원들이 역반사기 어레이를 설치한 후 이루어졌다.아폴로 14호와 아폴로 15호 임무에 의해 두 개의 역반사기 배열이 더 남겨졌다.역반사기에 대한 성공적인 달 레이저 거리 측정은 1969년 8월 1일 릭 [7]천문대의 3.1m 망원경에 의해 처음 보고되었다.애리조나주에 있는 공군 캠브리지 연구소의 달 거리 관측소, 프랑스의 픽 뒤 미디 천문대, 도쿄 천문대, 텍사스에 있는 맥도날드 천문대의 관측소들이 곧 뒤따랐다.

소련제 루노크호드 1호와 루노크호드 2호는 소형 어레이를 운반했다.반사 신호는 1974년까지 소련이 루노호트 1호에서 수신했지만 정확한 위치 정보를 가지고 있지 않은 서방 관측소에서는 수신되지 않았다.2010년 NASA의 달 정찰 궤도선은 이미지에서 루노크호드 1호 탐사선을 찾았고, 2010년 4월에는 캘리포니아 대학의 팀이 이 [8]탐사선을 조사했습니다.루노크호드 2호의 배열은 계속해서 [9]지구로 신호를 반환합니다.Lunokhod 어레이는 직사광선에서의 성능 저하로 인해 어려움을 겪고 있는데, 이는 아폴로 미션 [10]중 반사체 배치에 고려되는 요인입니다.

아폴로 15호 어레이는 이전의 두 아폴로 임무가 남긴 어레이의 3배 크기이다.그것의 크기 때문에 그것은 실험의 첫 25년 동안 실시된 표본 측정의 3/4의 목표가 되었다.이후 기술 향상에 따라 프랑스 니스에 있는 코트다쥐르 천문대와 뉴멕시코에 있는 아파치 포인트 천문대의 아파치 포인트 천문대 달 레이저 범위 측정 작업(APOLLO)과 같은 사이트에서 소형 어레이를 더 많이 사용하게 되었습니다.

2010년대에는 몇 가지 새로운 역반사기가 계획되었다.민간 MX-1E 착륙선이 설치하기로 한 MoonLIGHT 리플렉터는 기존 [11][12][13]시스템보다 측정 정확도를 최대 100배 높이도록 설계되었습니다.MX-1E는 2020년 [14]7월에 출시될 예정이었으나 2020년 2월 현재 MX-1E의 출시가 [15]취소되었다.

원칙

달까지의 거리는 거리 = (빛의 속도 × 반사에 의한 지연 시간) / 2. 빛의 속도가 정의된 상수이기 때문에 거리와 비행 시간 사이의 변환은 모호함 없이 이루어질 수 있다.

달 거리를 정확하게 계산하기 위해서는 왕복 시간 약 2.5초 외에 많은 요인을 고려해야 한다.이러한 요소들은 하늘에서 달의 위치, 지구와 달의 상대적 운동, 지구의 자전, 달의 진동, 극의 움직임, 날씨, 공기의 여러 부분에서 빛의 속도, 지구 대기를 통한 전파 지연, 지각 운동과 조수에 의한 관측소의 위치, 그리고 상대론적이다.이펙트[17][18]이 거리는 여러 가지 이유로 계속 변하지만, 지구의 [19]중심과 달의 중심 사이의 평균 385,000.6 km (239,228.3 mi)이다.달과 행성의 궤도는 물리적 [20]자유라고 불리는 달의 방향과 함께 숫자로 통합됩니다.

달 표면에서, 이 빔의 폭은 약 6.5 킬로미터이고[21][i] 과학자들은 빔을 조준하는 작업을 소총을 사용하여 3 킬로미터 떨어진 움직이는 다임을 명중시키는 것에 비유한다.반사광이 너무 약해서 사람의 눈으로 볼 수 없다.반사경을 겨냥한 10개의 광자 중21, 좋은 [22]조건에서도 오직 1개만이 지구로 보내진다.레이저가 단색성이 높기 때문에 레이저에서 발생한 것으로 식별할 수 있습니다.

2009년 현재, 달까지의 거리는 밀리미터의 [23]정밀도로 측정할 수 있다.이것은 비교적 정확한 거리 측정 중 하나이며, LA와 뉴욕 사이의 거리를 사람의 머리카락 폭 이내로 측정하는 것과 같은 정확도입니다.

역반사기 목록

천문대 목록

아래 표에는 지구에서 [19][24]활성 및 비활성 달 레이저 측거 스테이션 목록이 나와 있습니다.

| 전망대 | 프로젝트. | 동작 시간 범위 | 망원경 | 레이저 | 범위 정확도 | 레퍼런스 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 미국 텍사스주 맥도날드 천문대 | MLRS | 1969–1985 1985–2013 | 2.7 m | 694 nm, 7 J 532 nm, 200 ps, 150 mJ | [25] | |

| 크림 천체물리 관측소(CrAO), 소련 | 1974, 1982–1984 | 694 nm | 3.0~0.6m | [26] | ||

| 코트다쥐르 천문대(OCA), 프랑스 그라세 | 미오 | 1984–1986 1986–2010 2010 ~ 현재 (최종) | 694 nm 532 nm, 70 ps, 75 mJ 532/1064 nm | [19][27] | ||

| 미국 하와이 할레아칼라 천문대 | 루어 | 1984–1990 | 532 nm, 200 ps, 140 mJ | 2.0 cm | [19][28] | |

| 이탈리아 마테라 레이저 측거 천문대(MLRO) | 2003 ~ 현재 (표준) | 532 nm | ||||

| Apache Point Observatory (미국, 뉴멕시코) | 아폴로 | 2006–2020 | 532 nm, 100 ps, 115 mJ | 1.1mm | [19] | |

| 독일 베첼 측지천문대 | 무선 | 2018 ~ 현재 (최종) | 1064 nm, 10 ps, 75 mJ | [29] | ||

| 중국 쿤밍시 윈난천문대 | 2018 | 1.2 m | 532 nm, 10 ns, 3 J | 미터 레벨 | [30] |

데이터 분석

여러 파라미터의 수치값을 추출하기 위해 Lunar Laser Rangeing 데이터가 수집됩니다.범위 데이터 분석에는 역학, 지구물리학 및 달 지구물리학이 포함됩니다.모델링 문제에는 두 가지 측면, 즉 달 궤도와 달 방향의 정확한 계산과 관측소에서 역반사기로, 그리고 기지로 돌아가는 비행 시간에 대한 정확한 모델이 포함된다.최신 달 레이저 범위 데이터는 1cm 가중 RMS 잔차를 사용하여 적합할 수 있습니다.

- 이 프로그램은 물리적 진동이라고 불리는 달의 3축 방향을 통합합니다.

- 고체 지구의 조수와 질량의 중심에 대한 고체 지구의 계절적 움직임.

- 우주 정거장과 함께 움직이는 프레임에서 태양계 질량 중심에 대해 고정된 프레임으로 시간과 공간 좌표가 상대론적 변환.지구의 로렌츠 수축은 이 변환의 일부이다.

- 지구 대기의 지연.

- 태양, 지구, 달의 중력장으로 인한 상대론적 지연.

- 달의 방향과 고체 조류를 설명하는 역반사기의 위치.

- 달의 로렌츠 수축.

- 역반사 마운트의 열팽창 및 수축

지상파 모델의 경우 IERS 협약(2010)이 상세 정보의 [33]원천이다.

결과.

달 레이저 거리 측정 데이터는 파리 천문대 달 분석 센터,[34] 국제 레이저 거리 측정 서비스 아카이브 [35][36]및 활성 관측소에서 이용할 수 있습니다.이 장기 실험의 결과 [19]중 일부는 다음과 같습니다.

달의 성질

- 달까지의 거리는 밀리미터의 [23]정밀도로 측정할 수 있다.

- 달은 1년에 [21][37]3.8cm의 속도로 지구로부터 멀어지고 있다.이 비율은 비정상적으로 [38]높은 것으로 알려져 있습니다.

- 달의 유체핵은 코어/맨틀 경계 [39]소실의 영향에서 검출되었다.

- 달에는 하나 이상의 자극적인 [40]메커니즘이 필요한 무료 물리적 사서가 있다.

- 달의 조석 소산은 조석 [41]빈도에 따라 달라진다.

- 달은 아마도 달 [9]반지름의 약 20%의 액체 핵을 가지고 있을 것이다.달핵-망틀 경계 반경은 381±[42]12km로 결정된다.

- 달의 핵-망틀 경계의 극성 평탄화는 (2.2±0.6)×[42]10으로−4 결정된다.

- 달의 자유핵은 367±100yr로 [42]측정된다.

- 역반사기의 정확한 위치는 궤도를 도는 우주선이 [43]볼 수 있는 기준점이 된다.

중력 물리학

- 아인슈타인의 중력 이론(일반 상대성 이론)은 달의 궤도를 레이저 거리 [9][44]측정의 정확도 이내로 예측합니다.

- 게이지 자유도는 LLR [45]기술로 관측된 지구-달 시스템에서 상대론적 효과를 정확하게 해석하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다.

- 노르트베트 효과(달과 지구가 서로 다른 콤팩트 정도에 의해 태양을 향한 가상의 차등 가속도)의 가능성은 높은 [46][44][47]정밀도로 배제되어 강력한 등가 원리를 뒷받침하고 있다.

- 만유인력은 매우 안정적이다.실험은 뉴턴의 중력 상수 G의 변화를 연간 ([48]2±7)×10의−13 인수로 제한했다.

갤러리

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 캐롤 앨리(아폴로 달 레이저 측거팀의 첫 번째 주임)

- 라이다르

- 달 거리(천문)

- 위성 레이저 측거

- 우주 측지학

- 아폴로 달 착륙에 대한 제3자 증거

- 달의 인공 물체 목록

레퍼런스

- ^ 왕복 시간 동안 지구 관측자는 위도에 따라 약 1km 이동하게 됩니다.이것은 그러한 작은 반사경으로 가는 빔이 그러한 움직이는 표적에 명중할 수 없다는 주장이 거리 측정 실험의 '불확실'로 잘못 제시되었다.그러나 빔의 크기는 특히 반환된 빔의 경우 어떤 움직임보다 훨씬 큽니다.

- ^ Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G. (1999). "Determination of the lunar orbital and rotational parameters and of the ecliptic reference system orientation from LLR measurements and IERS data". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 343: 624–633. Bibcode:1999A&A...343..624C.

- ^ Müller, Jürgen; Murphy, Thomas W.; Schreiber, Ulrich; Shelus, Peter J.; Torre, Jean-Marie; Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H.; Bouquillon, Sebastien; Bourgoin, Adrien; Hofmann, Franz (2019). "Lunar Laser Ranging: a tool for general relativity, lunar geophysics and Earth science". Journal of Geodesy. 93 (11): 2195–2210. Bibcode:2019JGeod..93.2195M. doi:10.1007/s00190-019-01296-0. ISSN 1432-1394. S2CID 202641440.

- ^ Mazarico, Erwan; Sun, Xiaoli; Torre, Jean-Marie; Courde, Clément; Chabé, Julien; Aimar, Mourad; Mariey, Hervé; Maurice, Nicolas; Barker, Michael K.; Mao, Dandan; Cremons, Daniel R.; Bouquillon, Sébastien; Carlucci, Teddy; Viswanathan, Vishnu; Lemoine, Frank; Bourgoin, Adrien; Exertier, Pierre; Neumann, Gregory; Zuber, Maria; Smith, David (6 August 2020). "First two-way laser ranging to a lunar orbiter: infrared observations from the Grasse station to LRO's retro-reflector array". Earth, Planets and Space. 72 (1): 113. Bibcode:2020EP&S...72..113M. doi:10.1186/s40623-020-01243-w. ISSN 1880-5981.

- ^ Kornei, Katherine (15 August 2020). "How Do You Solve a Moon Mystery? Fire a Laser at It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Smullin, Louis D.; Fiocco, Giorgio (1962). "Optical Echoes from the Moon". Nature. 194 (4835): 1267. Bibcode:1962Natur.194.1267S. doi:10.1038/1941267a0. S2CID 4145783.

- ^ Bender, P. L.; et al. (1973). "The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment: Accurate ranges have given a large improvement in the lunar orbit and new selenophysical information" (PDF). Science. 182 (4109): 229–238. Bibcode:1973Sci...182..229B. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. PMID 17749298. S2CID 32027563.

- ^ a b Newman, Michael E. (26 September 2017). "To the Moon and Back … in 2.5 Seconds". NIST. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ McDonald, K. (26 April 2010). "UC San Diego Physicists Locate Long Lost Soviet Reflector on Moon". University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Williams, James G.; Dickey, Jean O. (2002). Lunar Geophysics, Geodesy, and Dynamics (PDF). 13th International Workshop on Laser Ranging. 7–11 October 2002. Washington, D. C.

- ^ "It's Not Just The Astronauts That Are Getting Older". Universe Today. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Currie, Douglas; Dell'Agnello, Simone; Delle Monache, Giovanni (April–May 2011). "A Lunar Laser Ranging Retroreflector Array for the 21st Century". Acta Astronautica. 68 (7–8): 667–680. Bibcode:2011AcAau..68..667C. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2010.09.001.

- ^ Tune, Lee (10 June 2015). "UMD, Italy & MoonEx Join to Put New Laser-Reflecting Arrays on Moon". UMD Right Now. University of Maryland.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (12 July 2017). "Moon Express unveils its roadmap for giant leaps to the lunar surface ... and back again". GeekWire. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Moon Express Lunar Scout (MX-1E), RocketLaunch.Live, retrieved 27 July 2019

- ^ "MX-1E 1, 2, 3". Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "Was Galileo Wrong? Science Mission Directorate".

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Seeber, Günter (2003). Satellite Geodesy (2nd ed.). de Gruyter. p. 439. ISBN 978-3-11-017549-3. OCLC 52258226.

- ^ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2020). "The JPL Lunar Laser range model 2020". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Murphy, T. W. (2013). "Lunar laser ranging: the millimeter challenge" (PDF). Reports on Progress in Physics. 76 (7): 2. arXiv:1309.6294. Bibcode:2013RPPh...76g6901M. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/76/7/076901. PMID 23764926. S2CID 15744316.

- ^ a b Park, Ryan S.; Folkner, William M.; Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2021). "The JPL Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides DE440 and DE441". The Astronomical Journal. 161 (3): 105. Bibcode:2021AJ....161..105P. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd414. ISSN 1538-3881. S2CID 233943954.

- ^ a b Espenek, F. (August 1994). "NASA - Accuracy of Eclipse Predictions". NASA/GSFC. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ Merkowitz, Stephen M. (2 November 2010). "Tests of Gravity Using Lunar Laser Ranging". Living Reviews in Relativity. 13 (1): 7. Bibcode:2010LRR....13....7M. doi:10.12942/lrr-2010-7. ISSN 1433-8351. PMC 5253913. PMID 28163616.

- ^ a b Battat, J. B. R.; Murphy, T. W.; Adelberger, E. G.; et al. (January 2009). "The Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation (APOLLO): Two Years of Millimeter-Precision Measurements of the Earth-Moon Range1". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 121 (875): 29–40. Bibcode:2009PASP..121...29B. doi:10.1086/596748. JSTOR 10.1086/596748.

- ^ Biskupek, Liliane; Müller, Jürgen; Torre, Jean-Marie (3 February 2021). "Benefit of New High-Precision LLR Data for the Determination of Relativistic Parameters". Universe. 7 (2): 34. arXiv:2012.12032. Bibcode:2021Univ....7...34B. doi:10.3390/universe7020034.

- ^ Bender, P. L.; Currie, D. G.; Dickey, R. H.; Eckhardt, D. H.; Faller, J. E.; Kaula, W. M.; Mulholland, J. D.; Plotkin, H. H.; Poultney, S. K.; et al. (1973). "The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment". Science. 182 (4109): 229–238. Bibcode:1973Sci...182..229B. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17749298. S2CID 32027563.

- ^ Yagudina (2018). "Processing and analysis of lunar laser ranging observations in Crimea in 1974-1984". Institute of Applied Astronomy of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Chabé, Julien; Courde, Clément; Torre, Jean-Marie; Bouquillon, Sébastien; Bourgoin, Adrien; Aimar, Mourad; Albanèse, Dominique; Chauvineau, Bertrand; Mariey, Hervé; Martinot-Lagarde, Grégoire; Maurice, Nicolas (2020). "Recent Progress in Lunar Laser Ranging at Grasse Laser Ranging Station". Earth and Space Science. 7 (3): e2019EA000785. Bibcode:2020E&SS....700785C. doi:10.1029/2019EA000785. ISSN 2333-5084. S2CID 212785296.

- ^ "Lure Observatory". Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii. 29 January 2002. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Eckl, Johann J.; Schreiber, K. Ulrich; Schüler, Torben (30 April 2019). Domokos, Peter; James, Ralph B; Prochazka, Ivan; Sobolewski, Roman; Gali, Adam (eds.). "Lunar laser ranging utilizing a highly efficient solid-state detector in the near-IR". Quantum Optics and Photon Counting 2019. International Society for Optics and Photonics. 11027: 1102708. Bibcode:2019SPIE11027E..08E. doi:10.1117/12.2521133. ISBN 9781510627208. S2CID 155720383.

- ^ Li Yuqiang, 李语强; Fu Honglin, 伏红林; Li Rongwang, 李荣旺; Tang Rufeng, 汤儒峰; Li Zhulian, 李祝莲; Zhai Dongsheng, 翟东升; Zhang Haitao, 张海涛; Pi Xiaoyu, 皮晓宇; Ye Xianji, 叶贤基; Xiong Yaoheng, 熊耀恒 (27 January 2019). "Research and Experiment of Lunar Laser Ranging in Yunnan Observatories". Chinese Journal of Lasers. 46 (1): 0104004. doi:10.3788/CJL201946.0104004. S2CID 239211201.

- ^ a b Pavlov, Dmitry A.; Williams, James G.; Suvorkin, Vladimir V. (2016). "Determining parameters of Moon's orbital and rotational motion from LLR observations using GRAIL and IERS-recommended models". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 126 (1): 61–88. arXiv:1606.08376. Bibcode:2016CeMDA.126...61P. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9712-1. ISSN 0923-2958. S2CID 119116627.

- ^ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2020). "The JPL Lunar Laser range model 2020". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "IERS - IERS Technical Notes - IERS Conventions (2010)". www.iers.org. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Lunar Laser Ranging Observations from 1969 to May 2013". SYRTE Paris Observatory. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ "International Laser Ranging Service".

- ^ "International Laser Ranging Service".

- ^ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2016). "Secular tidal changes in lunar orbit and Earth rotation". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 126 (1): 89–129. Bibcode:2016CeMDA.126...89W. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3. ISSN 0923-2958. S2CID 124256137.

- ^ Bills, B. G.; Ray, R. D. (1999). "Lunar Orbital Evolution: A Synthesis of Recent Results". Geophysical Research Letters. 26 (19): 3045–3048. Bibcode:1999GeoRL..26.3045B. doi:10.1029/1999GL008348.

- ^ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H.; Yoder, Charles F.; Ratcliff, J. Todd; Dickey, Jean O. (2001). "Lunar rotational dissipation in solid body and molten core". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 106 (E11): 27933–27968. Bibcode:2001JGR...10627933W. doi:10.1029/2000JE001396.

- ^ Rambaux, N.; Williams, J. G. (2011). "The Moon's physical librations and determination of their free modes" (PDF). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 109: 85–100. doi:10.1007/s10569-010-9314-2. S2CID 45209988.

- ^ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2016). "Secular tidal changes in lunar orbit and Earth rotation". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 126 (1): 89–129. Bibcode:2016CeMDA.126...89W. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3. ISSN 0923-2958. S2CID 124256137.

- ^ a b c Viswanathan, V.; Rambaux, N.; Fienga, A.; Laskar, J.; Gastineau, M. (9 July 2019). "Observational Constraint on the Radius and Oblateness of the Lunar Core‐Mantle Boundary". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (13): 7295–7303. arXiv:1903.07205. Bibcode:2019GeoRL..46.7295V. doi:10.1029/2019GL082677. S2CID 119508748.

- ^ Wagner, R. V.; Nelson, D. M.; Plescia, J. B.; Robinson, M. S.; Speyerer, E. J.; Mazarico, E. (2017). "Coordinates of anthropogenic features on the Moon". Icarus. 283: 92–103. Bibcode:2017Icar..283...92W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.011. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ a b Williams, J. G.; Newhall, X. X.; Dickey, J. O. (1996). "Relativity parameters determined from lunar laser ranging". Physical Review D. 53 (12): 6730–6739. Bibcode:1996PhRvD..53.6730W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.53.6730. PMID 10019959.

- ^ Kopeikin, S.; Xie, Y. (2010). "Celestial reference frames and the gauge freedom in the post-Newtonian mechanics of the Earth–Moon system". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 108 (3): 245–263. Bibcode:2010CeMDA.108..245K. doi:10.1007/s10569-010-9303-5. S2CID 122789819.

- ^ Adelberger, E. G.; Heckel, B. R.; Smith, G.; Su, Y.; Swanson, H. E. (1990). "Eötvös experiments, lunar ranging and the strong equivalence principle". Nature. 347 (6290): 261–263. Bibcode:1990Natur.347..261A. doi:10.1038/347261a0. S2CID 4286881.

- ^ Viswanathan, V; Fienga, A; Minazzoli, O; Bernus, L; Laskar, J; Gastineau, M (May 2018). "The new lunar ephemeris INPOP17a and its application to fundamental physics". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 476 (2): 1877–1888. arXiv:1710.09167. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty096.

- ^ Müller, J.; Biskupek, L. (2007). "Variations of the gravitational constant from lunar laser ranging data". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 24 (17): 4533. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/24/17/017. S2CID 120195732.

외부 링크

- 세르게이 코페이킨의 "달 레이저 측거 데이터의 신세대 이론과 모델"

- 아폴로 15호 실험 - 달과 행성 연구소의 레이저 측거 역반사기

- 텍사스 대학 오스틴 우주연구센터 '레이저 측거와 MLRS의 역사'

- 톰 머피의 "달 역반사"

- 프랑스 그라세의 Télémétrie Laser-Lune 스테이션

- 국제 레이저 측거 서비스로부터의 달 레이저 측거

- "UW 연구자는 달과 지구의 거리를 좁히는 프로젝트를 계획하고 있습니다." 빈스 스트리허즈, UW 투데이, 2002년 1월 14일

- 사이언스 @의 "Neil & Buzz가 달에 남긴 것"NASA, 2004년 7월 20일

- 1999년 7월 21일 CNN Robin Lloyd의 "Apollo 11 Experiment Still Returning Results" (아폴로 11 실험 아직도 결과가 반환됨)

- 2019년 8월 20일 유튜브 스미스소니언 국립항공우주박물관 '달에서 레이저 발사: 할 워커와 달 역반사기'