암 바이오마커

Cancer biomarker암 바이오마커는 암의 존재를 나타내는 물질이나 과정을 말한다.바이오마커는 암의 존재에 대한 종양 또는 신체의 특이적 반응에 의해 분비되는 분자일 수 있다.유전자, 후생유전자,[2] 단백질체,[3] 글리코믹 [4]및 영상 바이오마커는 [1]암 진단, 예후 및 역학에서 사용될 수 있습니다.이상적으로는 이러한 바이오마커는 혈액이나 [5]혈청 같은 비침습적으로 채취된 바이오유체에서 측정될 수 있다.

바이오마커 연구를 임상 공간으로 변환하는 데 있어 수많은 과제가 존재하지만, AFP(간암), BCR-ABL(만성 골수성 백혈병), BRCA1/BRCA2(유방/비만성 암), BRAF V600e(대장암)를 포함한 많은 유전자 및 단백질 기반 바이오마커가 이미 환자 치료의 어느 시점에 사용되었다.이안암, CA19.9(전형암), CEA(대장암), EGFR(비소세포 폐암), HER-2(유방암), KIT(위장관 간질종양), PSA(전형암), S100(흑색종) 및 기타 많은 기타.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15]선택된 반응 모니터링(SRM)에 의해 검출된 돌연변이 단백질 자체는 현존하는 [16]종양에서만 나올 수 있기 때문에 암을 일으키는 가장 특정한 생물 지표로 보고되었다.검사를 [17]통해 조기에 발견하면 암의 약 40%를 치료할 수 있다.

암 바이오마커의 정의

조직과 출판물은 바이오마커의 정의에 따라 다릅니다.많은 의학 분야에서 바이오마커는 혈액이나 소변에서 식별 가능하거나 측정 가능한 단백질로 제한됩니다.하지만, 이 용어는 종종 정량화되거나 측정될 수 있는 분자, 생화학, 생리학적 또는 해부학적 특성을 포괄하는 데 사용됩니다.

특히 국립암연구소(NCI)는 바이오마커를 다음과 같이 정의한다. "혈액, 다른 체액 또는 조직에서 발견되는 생물학적 분자로 정상 또는 비정상적인 과정, 또는 질병 또는 질환의 징후이다.바이오마커는 신체가 질병이나 상태에 대한 치료에 얼마나 잘 반응하는지 보기 위해 사용될 수 있다.분자표지,[18] 시그니처 분자라고도 불립니다.

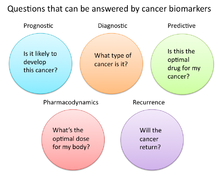

암 연구와 의학에서 바이오마커는 세 가지 [19]주요 방법으로 사용됩니다.

- 초기 암(진단)을 식별하는 경우와 같이 상태를 진단하는 데 도움이 됩니다.

- 치료가 없는 상태에서 환자의 건강 상태를 결정하는 경우와 같이 상태가 얼마나 공격적인지 예측한다(예측).

- 환자가 치료에 얼마나 잘 반응하는지 예측하기 위해(예측적)

암 연구와 의학에서 바이오마커의 역할

암의학에서의 바이오마커 사용

리스크 평가

암 바이오마커, 특히 유전자 돌연변이나 후생유전적 변화와 관련된 암 바이오마커는 개인이 특정 유형의 암에 걸리기 쉬운 시기를 결정하는 정량적 방법을 제공하는 경우가 많다.잠재적으로 예측 가능한 암 바이오마커의 주목할 만한 예로는 대장암, 식도암, 간암 및 췌장암에 대한 유전자 KRAS, p53, EGFR, erbB2, 유방암 및 난소암에 대한 유전자 BRCA1, BRCA2의 돌연변이, 종양억제 유전자 p16, CDKN2B, p14가 있다.뇌암의 경우 ARF, 자궁경부암의 경우 MYOD1, CDH1, CDH13의 과메틸화, 구강암의 [20]경우 p16, p14 및 RB1의 과메틸화.

진단.

암 바이오마커는 또한 특정 진단을 확립하는 데 유용할 수 있다.이것은 특히 종양이 1차적인지 전이적인지를 판단할 필요가 있는 경우에 해당된다.이러한 구별을 위해, 연구원들은 1차 종양 부위에 위치한 세포에서 발견된 염색체 변화를 2차 부위에서 발견된 것과 비교할 수 있다.변화가 일치하면 2차 종양이 전이성 종양으로 식별될 수 있는 반면, 변화가 다르면 2차 종양이 뚜렷한 1차 [21]종양으로 식별될 수 있다.예를 들어, 종양이 있는 사람들은 아포토시스를 [22]거친 종양 세포로 인해 높은 수준의 순환 종양 DNA를 가지고 있다.이 종양 마커는 혈액, 침, [17]소변에서 검출될 수 있습니다.차세대 염기서열분석 [23]연구에 의해 관찰된 종양의 고분자 이질성에 비추어 볼 때 조기 암 진단을 위한 효과적인 바이오마커를 식별할 수 있는 가능성은 최근 의문시되고 있다.

예후 및 치료 예측

암의학에서 바이오마커를 사용하는 또 다른 방법은 암 진단을 받은 후 발생하는 질병의 예후이다.여기서 바이오마커는 특정 치료에 반응할 가능성뿐만 아니라 확인된 암의 공격성을 결정하는 데 유용할 수 있다.부분적으로, 이것은 특정 바이오마커를 나타내는 종양이 그 바이오마커의 발현이나 존재와 관련된 치료에 반응할 수 있기 때문이다.그러한 예상 바이오 마커의 예로는 metallopeptidase 억제제 1(TIMP1), 마커를 여러 myeloma,[24] 높은 에스트로겐 수용체(응급실)및/또는 프로게스테론 수용체(PR)표현, 마커, 유방 암에 걸린 환자들에서 더 나은 전반적인 생존과 관련된 더 공격적인 형태와 관련[25][26]HER2/neu의 높아진 수준을 포함한다.유전자 ampliFication, 마커는 유방 암 여부를 나타내는 값이 trastuzumab 치료에;[27][28]은 원발암 유전자 c-KIT, 마커를 위장 세포막 종양(GIST)여부를 나타내는 값의 엑손 11에 있는 돌연변이 가능성이 높imatinib 치료에 대응할 것, 대응할 것[29][30] 돌연변이에 티로신 인산화 효소 도메인의 EGFR1, 마커를 나타내는 환자 아니 다예요.lunn-small-cellg canceroma(NSCLC)는 gefitinib 또는 erlotinib [31][32]치료에 반응할 가능성이 있습니다.

약역학 및 약역학

암 바이오마커는 또한 특정 사람의 [33]암에 대한 가장 효과적인 치료 방법을 결정하기 위해 사용될 수 있다.사람마다 유전자 구성이 다르기 때문에 어떤 사람들은 약물의 화학 구조를 다르게 바꾸거나 신진대사를 한다.어떤 경우에, 특정 약물의 신진대사가 감소하면 높은 수준의 약물이 체내에 축적되는 위험한 상태를 만들 수 있다.이와 같이, 특정 암 치료제에서의 약물 투여 결정은 그러한 바이오마커의 스크리닝으로부터 이익을 얻을 수 있다.예를 들어 티오푸린메틸전달효소([34]TPMPT)를 코드하는 유전자를 들 수 있다.TPMT 유전자에 돌연변이가 있는 사람들은 다량의 백혈병 약물인 메르캅토푸린을 대사할 수 없으며, 이것은 잠재적으로 그러한 환자들의 백혈구 수에서 치명적인 감소를 일으킨다.따라서 TPMT 돌연변이가 있는 환자에게는 안전을 [35]위해 낮은 용량의 메르캅토푸린을 투여하는 것이 좋습니다.

치료 반응 모니터링

암 바이오마커는 또한 시간이 지남에 따라 치료법이 얼마나 잘 작용하는지를 모니터링하는 데 유용함을 보여주었다.성공적인 바이오마커는 환자 치료 비용을 크게 절감할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있기 때문에 이 분야에 많은 연구가 진행되고 있습니다. 왜냐하면 종양 상태를 모니터링하기 위한 CT나 MRI와 같은 현재 이미지 기반 검사는 비용이 [36]매우 많이 들기 때문입니다.

주목할 만한 바이오마커는 악성 흑색종의 반응을 모니터링하는 단백질 바이오마커 S100-베타이다.이런 흑색종에서는 피부 색소를 만드는 세포인 멜라노사이트가 암세포 수에 따라 고농도로 S100-베타 단백질을 생산한다.따라서 치료에 대한 반응은 이러한 [37][38]개인의 혈액 중 S100-베타 수치 감소와 관련이 있다.

마찬가지로, 추가적인 실험실 연구는 아포토시스 중인 종양세포가 시토크롬 c, 뉴클레오솜, 절단된 시토케라틴-18 및 E-카드헤린과 같은 세포 성분을 방출할 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.연구 결과, 이러한 고분자와 다른 고분자가 암 치료 중에 순환되는 것을 발견할 수 있으며,[36] 치료를 모니터링하기 위한 임상 지표의 잠재적 원천을 제공한다.

반복

암 바이오마커는 암 재발을 예측하거나 모니터링하는 데에도 가치를 제공할 수 있다.Oncotype DX® 유방암 검사는 유방암 재발 가능성을 예측하는 데 사용되는 검사 중 하나입니다.이 테스트는 호르몬 치료로 치료될 초기 단계(I 또는 II 단계), 노드 음성, 에스트로겐 수용체 양성(ER+) 침습성 유방암을 가진 여성을 대상으로 합니다.종양형 DX는 종양 생검 중 채취한 세포에 있는 21개의 유전자 패널을 살펴봅니다.검사 결과는 10년 [39][40]후의 재발 가능성을 나타내는 재발 점수의 형태로 제시된다.

암 연구에 바이오마커 사용

약물 표적 개발

암 약물에 사용하는 것 외에도, 바이오마커는 종종 암 약물 발견 과정 전반에 걸쳐 사용됩니다.예를 들어, 1960년대에 연구자들은 만성 골수성 백혈병 환자의 대부분이 필라델피아 염색체라고 불리는 9번과 22번 염색체에 특정한 유전적 이상을 가지고 있다는 것을 발견했다.이 두 염색체가 결합하면 BCR-ABL로 알려진 암을 유발하는 유전자가 생성된다.이러한 환자들의 경우, 이 유전자는 백혈병의 모든 생리적 징후에서 주요 초기 지점 역할을 한다.수년간 BCR-ABL은 백혈병의 특정 아형을 계층화하기 위한 바이오마커로 사용되었다.하지만, 약물 개발자들은 결국 이 단백질을 효과적으로 억제하고 필라델피아 [41][42]염색체를 포함하는 세포의 생산을 현저하게 감소시키는 강력한 약물인 이마티닙을 개발할 수 있었다.

대리 엔드 포인트

바이오마커 적용의 또 다른 유망한 영역은 대리 끝점 영역이다.이 응용 프로그램에서 바이오마커는 암의 진행과 생존에 대한 약물의 효과를 대신하는 역할을 한다.이상적으로는 검증된 바이오마커를 사용하면 환자들이 새로운 약이 효과가 있는지 여부를 결정하기 위해 종양 생체검사와 장기 임상시험을 받아야 하는 것을 막을 수 있다.현행 의료기준에서 약물의 효능을 판단하는 지표는 약물이 사람의 암 진행을 감소시켰는지, 궁극적으로 생존을 연장시켰는지 여부를 확인하는 것이다.하지만, 만약 실패한 약들이 임상시험에 들어가기 전에 개발 파이프라인에서 제거될 수 있다면, 성공적인 바이오마커 대용품들은 상당한 시간, 노력, 그리고 돈을 절약할 수 있다.

대리 끝점 바이오마커의 이상적인 특성은 다음과 같다.[43][44]

- 바이오마커는 암을 유발하는 과정에 관여해야 합니다.

- 바이오마커의 변화는 질병의 변화와 관련이 있어야 한다.

- 바이오마커의 수준은 쉽고 안정적으로 측정할 수 있을 정도로 높아야 한다.

- 바이오마커의 수준이나 존재는 정상, 암 및 암 전 조직을 쉽게 구별할 수 있어야 한다.

- 암의 효과적인 치료는 바이오마커의 수준을 변화시켜야 한다

- 바이오마커의 수준은 암의 성공적인 치료와 관련이 없는 다른 요인에 반응하거나 자발적으로 변화해서는 안 된다.

특히 대리 마커로 주목받고 있는 두 가지 영역은 순환 종양 세포(CTC)[45][46]와 순환 miRNA이다.[47][48]이 두 마커 모두 혈액에 존재하는 종양 세포의 수와 관련이 있으며, 따라서 종양 진행 및 전이를 위한 대용품을 제공할 것으로 기대된다.그러나 이들의 채택에 있어 중요한 장벽은 혈액 내 CTC와 miRNA 수치를 농축, 식별 및 측정하기 어렵다는 것이다.임상 치료로 전환하기 [49][50][51]위해서는 새로운 기술과 연구가 필요할 수 있습니다.

암 바이오마커의 종류

분자암 바이오마커

| 종양형 | 바이오마커 |

|---|---|

| 유방. | ER/PR(에스트로겐 수용체/프로게스테론 수용체)[52][53] |

| HER-2/neu[52][53] | |

| 대장균 | EGFR[52][53] |

| KRAS[52][54] | |

| UGT1A1[52][54] | |

| 위. | HER-2/neu [52] |

| GIST | c킷[52][55] |

| 백혈병/림프종 | CD20[52][56] |

| CD30[52][57] | |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha[52][58] | |

| PDGFR[52][59] | |

| 필라델피아 염색체(BCR/ABL) | |

| PML/RAR-alpha[52][62] | |

| TPMT[52][63] | |

| UGT1A1 [52][64] | |

| 폐 | EML4[52][65][66] |

| EGFR[52][53] | |

| KRAS[52][53] | |

| 흑색종 | BRAF[52][66] |

| Pancreas | 류신, 이소류신과 valine[67]의 고상한 수치이다. |

| Ovaries | 난소암[68] |

바이오 마커의 또 다른 예는 바로

- 종양 억제기 암에서 졌다.

- 예:1기 유방 암, 제2유방 암 억제

- RNA

- 예:mRNA, microRNA[69]

- 체액이나 조직에서 발견되는 단백질.

- 예:Prostate-specific 항원, 난소암.

- 암 항원에 대한 항체

- DNA

특이성이 없는 암 바이오마커

모든 암 바이오마커가 암의 종류에 특유할 필요는 없다.순환계에서 발견되는 일부 바이오마커는 체내에 존재하는 세포의 비정상적인 성장을 결정하기 위해 사용될 수 있다.이러한 모든 종류의 바이오마커는 진단 혈액 검사를 통해 확인될 수 있으며, 이것이 정기적으로 건강 검사를 받아야 하는 주요 이유 중 하나이다.정기적으로 검사를 받는 것으로, 암과 같은 많은 건강상의 문제들이 조기에 발견되어 많은 사망자들을 예방할 수 있다.

호중구 대 림프구 비율은 많은 암의 비특이적 결정인자로 나타났다.이 비율은 악성 [71]종양이 있을 때 더 높은 것으로 나타나는 염증 반응에 관여하는 면역계의 두 가지 성분의 활성에 초점을 맞춘다.또한 염기성 섬유아세포증식인자(bFGF)는 세포의 증식에 관여하는 단백질이다.불행하게도, 종양이 있을 때 그것은 매우 활발하다는 것이 보여졌고, 이것은 악성 세포의 빠른 [72]번식을 도울 수 있다는 결론으로 이어졌다.연구에 따르면 항bFGF 항체는 여러 [72]기원의 종양을 치료하는데 사용될 수 있다.또한 인슐린 유사성장인자(IGF-R)는 세포 증식과 성장에 관여한다.어떤 결함으로 인한 [73]아포토시스, 프로그램된 세포사멸을 억제하는 데 관여할 수 있다.따라서 유방암, 전립선, 폐암, 대장암 등의 암 발생 [74]시 IGF-R 수치가 높아질 수 있다.

| 바이오마커 | 묘사 | 바이오센서 사용 |

|---|---|---|

| NLR(호중구 대 림프구비) | 암으로 인한[75] 염증을 동반하여 상승 | 아니요. |

| 기본섬유아세포증식인자(bFGF) | 이 수치는 종양이 있을 때 증가하여 종양세포의[76] 빠른 재생에 도움이 됩니다 | 전기화학[77] |

| 인슐린양성장인자(IGF-R) | 암세포의 높은 활성이 생식을 돕는다[78]. | 전기화학 임피던스 분광[citation needed] 센서 |

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Calzone KA (May 2012). "Genetic biomarkers of cancer risk". Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 28 (2): 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2012.03.007. PMID 22542320.

- ^ Herceg Z, Hainaut P (June 2007). "Genetic and epigenetic alterations as biomarkers for cancer detection, diagnosis and prognosis". Molecular Oncology. 1 (1): 26–41. doi:10.1016/j.molonc.2007.01.004. PMC 5543860. PMID 19383285.

- ^ Li D, Chan DW (April 2014). "Proteomic cancer biomarkers from discovery to approval: it's worth the effort". Expert Review of Proteomics. 11 (2): 135–136. doi:10.1586/14789450.2014.897614. PMC 4079106. PMID 24646122.

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola O, Toraño JS, Falcon-Perez JM, Williams C, Reichardt N, Boons GJ (2018). "Mass spectrometry for glycan biomarker discovery". TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 100: 7–14. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2017.12.015.

- ^ Mishra A, Verma M (March 2010). "Cancer biomarkers: are we ready for the prime time?". Cancers. 2 (1): 190–208. doi:10.3390/cancers2010190. PMC 3827599. PMID 24281040.

- ^ Rhea J, Molinaro RJ (March 2011). "Cancer Biomarkers: Surviving the journey from bench to bedside". Medical Laboratory Observer. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Behne T, Copur MS (1 January 2012). "Biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma". International Journal of Hepatology. 2012: 859076. doi:10.1155/2012/859076. PMC 3357951. PMID 22655201.

- ^ Musolino A, Bella MA, Bortesi B, Michiara M, Naldi N, Zanelli P, et al. (June 2007). "BRCA mutations, molecular markers, and clinical variables in early-onset breast cancer: a population-based study". Breast. 16 (3): 280–292. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2006.12.003. hdl:11381/1629553. PMID 17257844.

- ^ Dienstmann R, Tabernero J (March 2011). "BRAF as a target for cancer therapy". Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (3): 285–295. doi:10.2174/187152011795347469. PMID 21426297.

- ^ Lamparella N, Barochia A, Almokadem S (2013). "Impact of genetic markers on treatment of non-small cell lung cancer". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 779: 145–164. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6176-0_6. ISBN 978-1-4614-6175-3. PMID 23288638.

- ^ Orphanos G, Kountourakis P (2012). "Targeting the HER2 receptor in metastatic breast cancer". Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy. 5 (3): 127–137. doi:10.5144/1658-3876.2012.127. PMID 23095788.

- ^ Deprimo SE, Huang X, Blackstein ME, Garrett CR, Harmon CS, Schöffski P, et al. (September 2009). "Circulating levels of soluble KIT serve as a biomarker for clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients receiving sunitinib following imatinib failure". Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (18): 5869–5877. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2480. PMC 3500590. PMID 19737953.

- ^ Bantis A, Grammaticos P (Sep–Dec 2012). "Prostatic specific antigen and bone scan in the diagnosis and follow-up of prostate cancer. Can diagnostic significance of PSA be increased?". Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 15 (3): 241–246. PMID 23227460.

- ^ Kruijff S, Hoekstra HJ (April 2012). "The current status of S-100B as a biomarker in melanoma". European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 38 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.005. PMID 22240030.

- ^ Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN (November 2005). "Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 5 (11): 845–856. doi:10.1038/nrc1739. PMID 16239904. S2CID 25540232.

- ^ Wang Q, Chaerkady R, Wu J, Hwang HJ, Papadopoulos N, Kopelovich L, et al. (February 2011). "Mutant proteins as cancer-specific biomarkers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (6): 2444–2449. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.2444W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019203108. PMC 3038743. PMID 21248225.

- ^ a b c Li X, Ye M, Zhang W, Tan D, Jaffrezic-Renault N, Yang X, Guo Z (February 2019). "Liquid biopsy of circulating tumor DNA and biosensor applications". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 126: 596–607. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2018.11.037. PMID 30502682. S2CID 56479882.

- ^ "biomarker". NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02.

- ^ "Biomarkers in Cancer: An Introductory Guide for Advocates" (PDF). Research Advocacy Network. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Verma M, Manne U (October 2006). "Genetic and epigenetic biomarkers in cancer diagnosis and identifying high risk populations". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 60 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.04.002. PMID 16829121.

- ^ Leong PP, Rezai B, Koch WM, Reed A, Eisele D, Lee DJ, et al. (July 1998). "Distinguishing second primary tumors from lung metastases in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 90 (13): 972–977. doi:10.1093/jnci/90.13.972. PMID 9665144.

- ^ Lapin M, Oltedal S, Tjensvoll K, Buhl T, Smaaland R, Garresori H, et al. (November 2018). "Fragment size and level of cell-free DNA provide prognostic information in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer". Journal of Translational Medicine. 16 (1): 300. doi:10.1186/s12967-018-1677-2. PMC 6218961. PMID 30400802.

- ^ Dragani TA, Matarese V, Colombo F (April 2020). "Biomarkers for Early Cancer Diagnosis: Prospects for Success through the Lens of Tumor Genetics". BioEssays. 42 (4): e1900122. doi:10.1002/bies.201900122. PMID 32128843. S2CID 212406467.

- ^ Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA, Shrivastava V, Leitzel K, Christoulas D, Migkou M, et al. (March 2010). "High levels of serum TIMP-1 correlate with advanced disease and predict for poor survival in patients with multiple myeloma treated with novel agents". Leukemia Research. 34 (3): 399–402. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2009.08.035. PMID 19781774.

- ^ Kuukasjärvi T, Kononen J, Helin H, Holli K, Isola J (September 1996). "Loss of estrogen receptor in recurrent breast cancer is associated with poor response to endocrine therapy". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 14 (9): 2584–2589. doi:10.1200/jco.1996.14.9.2584. PMID 8823339.

- ^ Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, Norton L, Ravdin P, Taube S, et al. (November 2007). "American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 25 (33): 5287–5312. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2364. PMID 17954709.

- ^ Kröger N, Milde-Langosch K, Riethdorf S, Schmoor C, Schumacher M, Zander AR, Löning T (January 2006). "Prognostic and predictive effects of immunohistochemical factors in high-risk primary breast cancer patients". Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (1): 159–168. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1340. PMID 16397038.

- ^ Vrbic S, Pejcic I, Filipovic S, Kocic B, Vrbic M (Jan–Mar 2013). "Current and future anti-HER2 therapy in breast cancer". Journal of B.U.On. 18 (1): 4–16. PMID 23613383.

- ^ Yoo C, Ryu MH, Ryoo BY, Beck MY, Kang YK (October 2013). "Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of imatinib dose escalation to 800 mg/day in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors". Investigational New Drugs. 31 (5): 1367–1374. doi:10.1007/s10637-013-9961-8. PMID 23591629. S2CID 29477955.

- ^ Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, et al. (October 2006). "Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 368 (9544): 1329–1338. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. PMID 17046465. S2CID 25931515.

- ^ Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, Fehrenbacher L, Johnson BE, Sandler A, et al. (September 2005). "TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (25): 5892–5899. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. PMID 16043829.

- ^ Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. (May 2004). "Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (21): 2129–2139. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040938. PMID 15118073.

- ^ Sawyers CL (April 2008). "The cancer biomarker problem". Nature. 452 (7187): 548–552. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..548S. doi:10.1038/nature06913. PMID 18385728. S2CID 205213083.

- ^ Karas-Kuzelicki N, Mlinaric-Rascan I (August 2009). "Individualization of thiopurine therapy: thiopurine S-methyltransferase and beyond". Pharmacogenomics. 10 (8): 1309–1322. doi:10.2217/pgs.09.78. PMID 19663675.

- ^ Relling MV, Hancock ML, Rivera GK, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, Krynetski EY, et al. (December 1999). "Mercaptopurine therapy intolerance and heterozygosity at the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene locus". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 91 (23): 2001–2008. doi:10.1093/jnci/91.23.2001. PMID 10580024.

- ^ a b Schneider JE, Sidhu MK, Doucet C, Kiss N, Ohsfeldt RL, Chalfin D (November 2012). "Economics of cancer biomarkers". Personalized Medicine. 9 (8): 829–837. doi:10.2217/pme.12.87. PMID 29776231.

- ^ Henze G, Dummer R, Joller-Jemelka HI, Böni R, Burg G (1997). "Serum S100--a marker for disease monitoring in metastatic melanoma". Dermatology. 194 (3): 208–212. doi:10.1159/000246103. PMID 9187834.

- ^ Harpio R, Einarsson R (July 2004). "S100 proteins as cancer biomarkers with focus on S100B in malignant melanoma". Clinical Biochemistry. 37 (7): 512–518. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.012. PMID 15234232.

- ^ Lamond NW, Skedgel C, Younis T (April 2013). "Is the 21-gene recurrence score a cost-effective assay in endocrine-sensitive node-negative breast cancer?". Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 13 (2): 243–250. doi:10.1586/erp.13.4. PMID 23570435. S2CID 33661439.

- ^ Biroschak JR, Schwartz GF, Palazzo JP, Toll AD, Brill KL, Jaslow RJ, Lee SY (May 2013). "Impact of Oncotype DX on treatment decisions in ER-positive, node-negative breast cancer with histologic correlation". The Breast Journal. 19 (3): 269–275. doi:10.1111/tbj.12099. PMID 23614365. S2CID 30895945.

- ^ Moen MD, McKeage K, Plosker GL, Siddiqui MA (2007). "Imatinib: a review of its use in chronic myeloid leukaemia". Drugs. 67 (2): 299–320. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767020-00010. PMID 17284091.

- ^ Lemonick M, Park A (May 28, 2001). "New Hope for Cancer". Time. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Price C, McDonnell D (February 1991). "Effects of niobium filtration and constant potential on the sensitometric responses of dental radiographic films". Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology. 20 (1): 11–16. doi:10.1259/dmfr.20.1.1884846. PMID 1884846.

- ^ Cohen V, Khuri FR (2003). "Progress in lung cancer chemoprevention". Cancer Control. 10 (4): 315–324. doi:10.1177/107327480301000406. PMID 12915810.

- ^ Lu CY, Tsai HL, Uen YH, Hu HM, Chen CW, Cheng TL, et al. (March 2013). "Circulating tumor cells as a surrogate marker for determining clinical outcome to mFOLFOX chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 108 (4): 791–797. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.595. PMC 3590657. PMID 23422758.

- ^ Balic M, Williams A, Lin H, Datar R, Cote RJ (2013). "Circulating tumor cells: from bench to bedside". Annual Review of Medicine. 64: 31–44. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-050311-163404. PMC 3809995. PMID 23092385.

- ^ Madhavan D, Zucknick M, Wallwiener M, Cuk K, Modugno C, Scharpff M, et al. (November 2012). "Circulating miRNAs as surrogate markers for circulating tumor cells and prognostic markers in metastatic breast cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 18 (21): 5972–5982. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1407. PMID 22952344.

- ^ Redova M, Sana J, Slaby O (March 2013). "Circulating miRNAs as new blood-based biomarkers for solid cancers". Future Oncology. 9 (3): 387–402. doi:10.2217/fon.12.192. PMID 23469974.

- ^ Joosse SA, Pantel K (January 2013). "Biologic challenges in the detection of circulating tumor cells". Cancer Research. 73 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3422. PMID 23271724.

- ^ Hou HW, Warkiani ME, Khoo BL, Li ZR, Soo RA, Tan DS, et al. (2013). "Isolation and retrieval of circulating tumor cells using centrifugal forces". Scientific Reports. 3: 1259. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1259H. doi:10.1038/srep01259. PMC 3569917. PMID 23405273.

- ^ Dhondt B, De Bleser E, Claeys T, Buelens S, Lumen N, Vandesompele J, et al. (December 2019). "Discovery and validation of a serum microRNA signature to characterize oligo- and polymetastatic prostate cancer: not ready for prime time". World Journal of Urology. 37 (12): 2557–2564. doi:10.1007/s00345-018-2609-8. hdl:1854/LU-8586484. PMID 30578441. S2CID 58594673.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labels". U.S Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ a b c d e "Tumor Markers Fact Sheet" (PDF). American Cancer Society.

- ^ a b Heinz-Josef Lenz (2012-09-18). Biomarkers in Oncology: Prediction and Prognosis. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-4419-9754-8.

- ^ Gonzalez RS, Carlson G, Page AJ, Cohen C (July 2011). "Gastrointestinal stromal tumor markers in cutaneous melanomas: relationship to prognostic factors and outcome". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 136 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1309/AJCP9KHD7DCHWLMO. PMID 21685034.

- ^ Tam CS, Otero-Palacios J, Abruzzo LV, Jorgensen JL, Ferrajoli A, Wierda WG, et al. (April 2008). "Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia CD20 expression is dependent on the genetic subtype: a study of quantitative flow cytometry and fluorescent in-situ hybridization in 510 patients". British Journal of Haematology. 141 (1): 36–40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07012.x. PMID 18324964.

- ^ Zhang M, Yao Z, Patel H, Garmestani K, Zhang Z, Talanov VS, et al. (May 2007). "Effective therapy of murine models of human leukemia and lymphoma with radiolabeled anti-CD30 antibody, HeFi-1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (20): 8444–8448. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8444Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702496104. PMC 1895969. PMID 17488826.

- ^ Yamada Y, Sanchez-Aguilera A, Brandt EB, McBride M, Al-Moamen NJ, Finkelman FD, et al. (September 2008). "FIP1L1/PDGFRalpha synergizes with SCF to induce systemic mastocytosis in a murine model of chronic eosinophilic leukemia/hypereosinophilic syndrome". Blood. 112 (6): 2500–2507. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-11-126268. PMID 18539901.

- ^ Nimer SD (May 2008). "Myelodysplastic syndromes". Blood. 111 (10): 4841–4851. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-08-078139. PMID 18467609. S2CID 6802096.

- ^ Ottmann O, Dombret H, Martinelli G, Simonsson B, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. (October 2007). "Dasatinib induces rapid hematologic and cytogenetic responses in adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with resistance or intolerance to imatinib: interim results of a phase 2 study". Blood. 110 (7): 2309–2315. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-02-073528. PMID 17496201.

- ^ Boulos N, Mulder HL, Calabrese CR, Morrison JB, Rehg JE, Relling MV, et al. (March 2011). "Chemotherapeutic agents circumvent emergence of dasatinib-resistant BCR-ABL kinase mutations in a precise mouse model of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Blood. 117 (13): 3585–3595. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-08-301267. PMC 3072880. PMID 21263154.

- ^ O'Connell PA, Madureira PA, Berman JN, Liwski RS, Waisman DM (April 2011). "Regulation of S100A10 by the PML-RAR-α oncoprotein". Blood. 117 (15): 4095–4105. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-07-298851. PMID 21310922.

- ^ Duffy MJ, Crown J (November 2008). "A personalized approach to cancer treatment: how biomarkers can help". Clinical Chemistry. 54 (11): 1770–1779. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.110056. PMID 18801934.

- ^ Ribrag V, Koscielny S, Casasnovas O, Cazeneuve C, Brice P, Morschhauser F, et al. (April 2009). "Pharmacogenetic study in Hodgkin lymphomas reveals the impact of UGT1A1 polymorphisms on patient prognosis". Blood. 113 (14): 3307–3313. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-03-148874. PMID 18768784.

- ^ Li Y, Ye X, Liu J, Zha J, Pei L (January 2011). "Evaluation of EML4-ALK fusion proteins in non-small cell lung cancer using small molecule inhibitors". Neoplasia. 13 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1593/neo.101120. PMC 3022423. PMID 21245935.

- ^ a b Pao W, Girard N (February 2011). "New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer". The Lancet. Oncology. 12 (2): 175–180. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. PMID 21277552.

- ^ Hewes A (October 2, 2014). "Promising Method for Detecting Pancreatic Cancer Years Before Traditional Diagnosis". Singularity HUB. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ^ Gupta D, Lis CG (October 2009). "Role of CA125 in predicting ovarian cancer survival - a review of the epidemiological literature". Journal of Ovarian Research. 2 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1757-2215-2-13. PMC 2764643. PMID 19818123.

- ^ Bartels CL, Tsongalis GJ (April 2009). "MicroRNAs: novel biomarkers for human cancer". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (4): 623–631. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.112805. PMID 19246618.

- ^ Paulson KG, Lewis CW, Redman MW, Simonson WT, Lisberg A, Ritter D, et al. (April 2017). "Viral oncoprotein antibodies as a marker for recurrence of Merkel cell carcinoma: A prospective validation study". Cancer. 123 (8): 1464–1474. doi:10.1002/cncr.30475. PMC 5384867. PMID 27925665.

- ^ Proctor MJ, McMillan DC, Morrison DS, Fletcher CD, Horgan PG, Clarke SJ (August 2012). "A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 107 (4): 695–699. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.292. PMC 3419948. PMID 22828611.

- ^ a b Liu M, Xing LQ (August 2017). "Basic fibroblast growth factor as a potential biomarker for diagnosing malignant tumor metastasis in women". Oncology Letters. 14 (2): 1561–1567. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.6335. PMC 5529833. PMID 28789380.

- ^ Fürstenberger G, Senn HJ (May 2002). "Insulin-like growth factors and cancer". The Lancet. Oncology. 3 (5): 298–302. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00731-3. PMID 12067807.

- ^ Yu H, Rohan T (September 2000). "Role of the insulin-like growth factor family in cancer development and progression". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 92 (18): 1472–1489. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.18.1472. PMID 10995803.

- ^ Vano YA, Oudard S, By MA, Têtu P, Thibault C, Aboudagga H, et al. (2018-04-06). "Optimal cut-off for neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: Fact or Fantasy? A prospective cohort study in metastatic cancer patients". PLOS ONE. 13 (4): e0195042. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1395042V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195042. PMC 5889159. PMID 29624591.

- ^ Liu M, Xing LQ (August 2017). "Basic fibroblast growth factor as a potential biomarker for diagnosing malignant tumor metastasis in women". Oncology Letters. 14 (2): 1561–1567. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.6335. PMC 5529833. PMID 28789380.

- ^ Torrente-Rodríguez RM, Ruiz-Valdepeñas Montiel V, Campuzano S, Pedrero M, Farchado M, Vargas E, et al. (2017-04-04). "Electrochemical sensor for rapid determination of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 in raw cancer cell lysates". PLOS ONE. 12 (4): e0175056. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1275056T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175056. PMC 5380347. PMID 28376106.

- ^ Denduluri SK, Idowu O, Wang Z, Liao Z, Yan Z, Mohammed MK, et al. (March 2015). "Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling in tumorigenesis and the development of cancer drug resistance". Genes & Diseases. 2 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2014.10.004. PMC 4431759. PMID 25984556.