미시시피 대학교

University of Mississippi | |

| 좌우명 | 프로사이언티아 에 사피엔시아 (라틴어) |

|---|---|

영어 모토 | "지식과 지혜를 위하여" |

| 유형 | 일반의 연구 대학 |

| 설립된 | 1844년 2월 24일; 전[note 1] |

| 기부금 | 8억 4천만 달러 (2023) |

| 예산. | 6억 7천만 달러 (2024) |

| 재상 | 글렌 보이스 |

| 프로보스트 | 노을이. 윌킨 |

| 학생들 | 24,710(2023년 가을) |

| 위치 | , |

| 캠퍼스 | 3,497에이커(14.15km2)의 외딴 마을[2] |

| 닉네임 | 반란군 |

스포츠 계열사 | |

| 웹사이트 | olemiss.edu |

| |

미시시피 대학교(University of Missippi, 이름은 Ole Miss)는 미시시피주 옥스퍼드에 인접해 있으며 잭슨에 의료 센터가 있는 공립 연구 대학입니다. 미시시피주에서 가장 오래된 공립 대학이며 입학생 기준으로 두 번째로 많습니다.[3]

미시시피 주의회는 1844년 2월 24일 이 대학에 전세를 주었고, 4년 후 첫 80명의 학생을 입학시켰습니다. 남북전쟁 중에 이 대학은 남부연합 병원으로 운영되었고 율리시스 S. 그랜트의 군대에 의한 파괴를 간신히 피했습니다. 1962년 민권운동을 하던 중 인종차별주의자들이 아프리카계 미국인 학생 제임스 메러디스의 입학을 막으려다 캠퍼스에서 인종 폭동이 일어났습니다. 그 이후로 대학은 이미지 개선을 위한 조치를 취했습니다. 이 대학은 작가 윌리엄 포크너(William Faulkner)와 밀접한 관련이 있으며, 그의 이전 옥스퍼드 홈인 로완 오크(Rowan Oak)를 소유 및 관리하고 있으며, 다른 캠퍼스 내 사이트인 바너드 천문대(Barnard Observatory)와 라이시움(Lysceum)과 함께 운영하고 있습니다.서클 역사 지구는 국가 사적지(National Register of Historic Places)에 등재되어 있습니다.

Ole Miss는 "R1: 박사과정 대학 – 매우 높은 연구 활동"으로 분류됩니다. 국가해양교부금 프로그램에 참여하는 33개 기관 중 하나이며, 국가우주교부금 대학 및 펠로우십 프로그램에도 참여하고 있습니다. 그 연구 노력에는 국립 물리 음향 센터, 국립 천연물 연구 센터, 미시시피 슈퍼 컴퓨팅 연구 센터가 포함됩니다. 이 대학은 미국에서 유일하게 연방 계약을 체결한 식품의약국(FDA) 승인 대마초 시설을 운영하고 있습니다. 또한 남부문화연구센터 등 학제 간 연구소도 운영하고 있습니다. 이 팀의 운동팀들은 전미 대학 체육 협회의 디비전 I 남동부 컨퍼런스에서 올레 미스 레블스로 경쟁합니다.

이 대학의 동문, 교수진 및 계열사에는 27명의 로도스 학자, 10명의 주지사, 5명의 미국 상원의원, 정부 수반 및 노벨상 수상자가 있습니다. 다른 동문들은 에미상, 그래미상, 퓰리처상과 같은 상을 받았습니다. 의료 센터는 최초의 인간 폐 이식 및 동물 대 인간 심장 이식을 수행했습니다.

역사

건국과 초기 역사

미시시피 주의회는 1844년 2월 24일 미시시피 대학교에 전세를 주었습니다.[4] 기획자들은 옥스퍼드에 있는 고립된 시골 지역을 학문을 육성할 "실반 망명지"로 선택했습니다.[5] 1845년 라파예트 카운티 주민들은 캠퍼스를 위해 옥스포드 서쪽의 땅을 기부했고, 이듬해 건축가 윌리엄 니콜스는 라이세움(Lycum)이라는 학술 건물, 두 개의 기숙사 및 교수진 거주지 건설을 감독했습니다.[4] 1848년 11월 6일, 고전적인 교육과정을 제공하는 이 대학은 80명의 학생들로 이루어진 첫 수업을 열었는데,[5][6] 그들 대부분은 백인이었고, 한 명을 제외하고는 모두 미시시피 출신인 엘리트 노예 소유자들의 자녀들이었습니다.[5][7] 23년 동안 이 대학은 미시시피주의 유일한 고등 교육[8] 공공 기관이었으며 110년 동안 이 대학의 유일한 종합 대학이었습니다.[9] 1854년에 미시시피 법대가 설립되어 미국에서 네 번째로 주에서 지원하는 로스쿨이 되었습니다.[10]

프레더릭 A.P. 바너드 초기 총장은 대학의 위상을 높이려고 노력했고, 그를 더 보수적인 이사회와 갈등하게 만들었습니다.[11] 바너드가 1858년 이사회에 제출한 100쪽짜리 보고서의 유일한 결과는 대학 총장의 직함이 "총장"으로 바뀐 것뿐이었습니다.[12] 버나드는 매사추세츠 출신으로 예일 대학교를 졸업했습니다. 그의 북부 배경과 유니언의 동정심은 그의 입장을 논쟁적으로 만들었습니다. 한 학생이 그의 노예를 폭행했고 주 의회는 그를 조사했습니다.[11] 1860년 미국 대통령 에이브러햄 링컨이 당선된 후 미시시피 주는 분리된 두 번째 주가 되었고, 이 대학의 수학 교수 루시우스 퀸투스 신시내투스 라마는 분리 조항의 초안을 작성했습니다.[13] 학생들은 "University Greys"라는 군사 회사로 조직되었고, 이 회사는 남부연합군 제11 미시시피 보병 연대인 A 중대가 되었습니다.[14] 남북전쟁이 발발한 지 한 달 만에 단 5명의 학생만이 이 대학에 남아 있었고, 1861년 말에 이 대학은 문을 닫았습니다. 마지막 조치로 이사회는 바너드에게 신학박사 학위를 수여했습니다.[14]

6개월 만에 캠퍼스는 남부연합 병원으로 바뀌었고, 리세움은 병원으로 사용되었고, 오늘날의 팔리 홀 부지에 있던 건물은 영안실로 운영되었습니다.[15] 1862년 11월 율리시스 S. 그랜트 장군의 연합군이 접근함에 따라 캠퍼스는 대피했습니다. 비록 칸산군이 의료 장비의 상당 부분을 파괴했지만, 홀로 남은 교수 한 명이 캠퍼스를 불태우는 것을 반대하며 그랜트를 설득했습니다.[16][note 2] 그랜트의 부대는 3주 후에 떠났고 캠퍼스는 남부연합 병원으로 돌아갔습니다. 전쟁이 진행되는 동안 700명이 넘는 군인들이 학교에 묻혔습니다.[18]

전후

미시시피 대학은 1865년 10월에 다시 문을 열었습니다.[18] 퇴역군인을 거부하지 않기 위해 대학은 등록금을 없애고 학생들이 캠퍼스 밖에서 살 수 있도록 함으로써 입학 기준을 낮추고 비용을 줄였습니다.[6] 학생회는 완전히 백인으로 남아 있었습니다: 1870년 수상은 자신과 전체 교수진이 "흑인" 학생들을 입학시키는 대신 사임할 것이라고 선언했습니다.[19] 1882년, 대학은 여성들을[20] 입학시키기 시작했지만, 그들은 캠퍼스에 살거나 로스쿨에 다니는 것이 허용되지 않았습니다.[6] 1885년 미시시피 대학교는 사라 맥기 아이솜을 고용하여 미국 남동부 최초로 여성 교수를 고용했습니다.[6][21] 거의 100년 후, 그녀를 기리기 위해 사라 이솜 여성 및 성별 연구 센터가 설립되었습니다.[6][21]

이 대학의 애칭인 "올레 미스"는 1897년에 처음 사용되었는데, 이 때 이 대학은 졸업장 제목에 대한 제안 공모전에서 우승을 차지했습니다.[22] 이 용어는 농장의 정부와 "젊은 아가씨"를 구별하기 위해 사용되는 가사 노예라는 칭호에서 비롯되었습니다.[23] 프린지 기원설에는 "올드 미시시피"의 작은 이름에서 [24][25][26]유래하거나 멤피스에서 뉴올리언스까지 운행하는 "올 미스" 열차의 이름에서 유래한 것이 포함됩니다.[22][27] 2년 안에 학생들과 동문들은 대학을 가리키기 위해 "올레 미스"를 사용했습니다.[28]

1900년에서 1930년 사이에 미시시피 주 의회는 대학을 미시시피 주립 대학과 이전, 폐쇄 또는 합병하는 것을 목표로 하는 법안을 제출했습니다. 그런 모든 입법은 실패했습니다.[29] 1930년대 동안 미시시피 주지사 시어도어 G. 빌보는 미시시피 대학에 정치적으로 적대적이었고, 행정가와 교수진을 해고하고 "빌보 숙청"에서 그들을 친구들로[30] 대체했습니다.[31] 빌보의 행동은 대학의 명성에 심각한 손상을 입혔고, 일시적으로 인가를 잃게 되었습니다. 이에 따라 1944년 미시시피주 헌법은 정치적 압력으로부터 미시시피주의 이사회를 보호하기 위해 개정되었습니다.[30] 제2차 세계 대전 동안 미시시피 대학교는 학생들에게 해군 위원회의 길을 제공하는 국가 V-12 해군 대학 훈련 프로그램에 참여한 131개 대학 중 하나였습니다.[32]

통합

1954년, 미국 대법원은 브라운 대 교육 위원회에서 공립학교에서의 인종 차별이 위헌이라고 판결했습니다.[33] 브라운 판결 이후 8년 만에 아프리카계 미국인 지원자들의 입학 시도는 모두 실패로 돌아갔습니다.[34][35] 1961년 존 F 대통령 취임 직후. 케네디, 제임스 메러디스(James Meredith)는 아프리카계 미국인 공군 퇴역 군인이자 잭슨 주립대학(Jackson State University) 학생으로 미시시피 대학에 지원했습니다.[36] 미시시피주 공무원들의 수개월간의 방해 끝에, 미국 대법원은 메러디스의 등록을 명령했고, 로버트 F 법무장관이 이끄는 법무부에 명령을 내렸습니다. 케네디는 메러디스를 대신해서 사건을 접수했습니다.[34][37] 로스 R 주지사는 세 번에 걸쳐. 바넷 또는 부지사 폴 B. 존슨 주니어는 메러디스의 캠퍼스 진입을 물리적으로 막았습니다.[38][39]

미국 제5순회항소법원은 바넷과 존슨 주니어를 모두 모욕죄로 기소하고, 메러디스 등록을 거부한 날마다 1만 달러를 넘는 벌금을 부과했습니다.[40] 1962년 9월 30일, 케네디 대통령은 127명의 미국 보안관과 316명의 대리 미국 국경순찰대 요원, 97명의 연방교도소 직원을 메러디스를 호위하기 위해 파견했습니다.[41] 해가 진 뒤 극우 성향의 에드윈 워커 전 소장과 외부 선동가들이 도착했고, 라이세움 이전의 분리주의 학생들의 모임은 폭력적인 폭도가 됐습니다.[42][43][44] 분리주의 폭도들은 화염병과 산병을 던지고 연방 보안관과 기자들을 향해 총을 발사했습니다.[45][46] 프랑스 언론인 폴 귀하드와 옥스퍼드 수리공 레이 군터 등 민간인 2명이 총격으로 숨졌습니다.[47][48] 결국 13,000명의 군인들이 옥스퍼드에 도착하여 폭동을 진압했습니다.[49] 연방 장교의 3분의 1인 166명이 부상을 입었고, 40명의 연방 군인과 주 방위군도 부상을 입었습니다.[48] 옥스퍼드에서 30,000명 이상의 인력이 배치되고 경고되었으며, 이는 미국 역사상 단 한 번의 소동으로 가장 많은 것입니다.[50]

메러디스는 10월 1일에 등록하고 수업에 참석했습니다.[51] 1968년까지 Ole Miss에는 약 100명의 아프리카계 미국인 학생이 [52]있었고 2019-2020 학년도에는 아프리카계 미국인이 학생의 12.5%를 차지했습니다.[53]

최근사

1972년, 올레 미스는 노벨 문학상을 수상한 작가 윌리엄 포크너의 전 집인 로완 오크를 구입했습니다.[55][56] 이 건물은 1962년 포크너가 사망했을 때 그대로 보존되어 있습니다. 포크너(Faulkner)는 1920년대 초에 이 대학의 우체국장이었고, 이 대학의 강력한 권력자인 나는 죽어가면서(As I Lay Dying, 1930)를 썼습니다. 그의 노벨상 메달은 대학 도서관에 전시되어 있습니다.[57] 이 대학은 1974년 포크너와 욕나파타와파 회의를 처음 개최했습니다. 1980년, 윌리 모리스는 거주지에 있는 대학의 첫 작가가 되었습니다.[6]

2002년, 올레 미스는 통합 40주년을 맞아 대학의 구술 역사, 심포지엄, 기념관, 캠퍼스에서 근무했던 연방 원수들의 재결합 등 1년 동안의 일련의 행사들과 함께 했습니다.[58][59] 통합 44주년인 2006년, 메러디스 동상이 캠퍼스에 헌정되었습니다.[60] 2년 후, 1962년 폭동이 일어난 장소는 국가 사적지로 지정되었습니다.[61] 이 대학은 또한 2012년에 통합 50주년을 기념하여 1년 동안 프로그램을 개최했습니다.[62] 이 대학은 2008년 최초의 대통령 토론회(미시시피에서 열린 최초의 대통령 토론회)를 존 매케인 상원의원과 버락 오바마 상원의원 사이에서 개최했습니다.[63][64]

올레 미스는 2003년 마스코트인 렙 대령을 남부연합 이미지를 이유로 은퇴시켰습니다.[65] 비록 스타워즈 캐릭터인 반란군 연합의 악바르 제독을 채택하려는 풀뿌리 운동이 상당한 지지를 얻었지만,[66][67] 포크너의 단편 소설 곰을 지칭하는 Rebell Black Bear는 2010년에 선정되었습니다.[68][69] 곰은 2017년에 다른 마스코트인 Tony the Landshark로 대체되었습니다.[69][70] 2022년부터 축구 코치 레인 키핀의 개 주스가 사실상의 마스코트가 되었습니다.[71][72] 2015년에는 남부연합 전투 엠블럼이 포함된 미시시피 주 국기를 철거했고,[73] 2020년에는 남부연합의 저명한 기념물을 이전했습니다.[74]

캠퍼스

옥스퍼드 캠퍼스

미시시피 대학교의 옥스퍼드 캠퍼스는 부분적으로는 옥스퍼드에 위치하고 부분적으로는 인구 조사 지정 장소인 미시시피 대학교에 위치합니다.[75] 메인 캠퍼스는 약 500피트(150m)의 고도에 위치해 있으며, 1평방 마일(260ha)의 땅에서 약 1,200에이커(1.9평방 마일; 490ha)로 확장되었습니다. 캠퍼스의 건물들은 대부분 조지아 건축 양식으로 설계되었습니다; 새로운 건물들 중 일부는 더 현대적인 건축을 가지고 있습니다.[76]

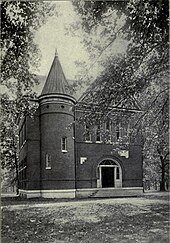

캠퍼스의 중심에는 타원형의 공용 건물을 중심으로 구성된 8개의 학술 건물로 구성된 "The Circle"이 있습니다. 이 건물들은 리세움 (1848), Y 빌딩 (1853), 그리고 신고전주의 부흥 양식으로 지어진 6개의 나중 건물들을 포함합니다.[61] 라이세움은 캠퍼스의 첫 번째 건물이었고 1903년에 두 개의 날개로 확장되었습니다. 이 대학에 따르면, 라이세움의 종은 미국에서 가장 오래된 학술 종이라고 합니다.[76] 서클 근처에는 로버트 버웰 풀턴(Robert Burwell Fulton) 1893년 총리가 마련한 10에이커(4.0ha)의 부지인 그로브(The Grove)가 있으며, 홈 경기 동안 최대 100,000개의 테일게이트를 수용합니다.[77][78] 1859년 버나드 수상 아래 건설된 버나드 천문대는 세계에서 가장 큰 망원경을 수용하도록 설계되었습니다. 하지만 남북전쟁의 발발로 망원경은 전달된 적이 없었고 대신 노스웨스턴 대학에 인수되었습니다.[76][79] 이 천문대는 1978년 국가 사적지(National Register of Historic Places)에 등재되었습니다.[80][81] 남북전쟁 이후에 지어진 첫 번째 주요 건물은 1889년 빅토리아 양식의 로마네스크 양식으로 지어진 벤트레스 홀(Ventress Hall)입니다.[76]

1929년부터 1930년까지 건축가 Frank P. Gates는 캠퍼스에서 18개의 건물을 디자인했는데, 대부분은 (구) University High School, Bar Hall, Bondurant Hall, Farley Hall (라마르 홀로도 알려져 있음), Faulkner Hall, Wesley Knight Field House를 포함합니다.[82][83] 1930년대 동안 캠퍼스의 많은 건물 프로젝트는 공공 사업국과 기타 연방 기관에서 주로 자금을 지원했습니다.[84] 이 시기에 지어진 주목할 만한 건물 중에는 이중 돔 케논 천문대(1939)가 있습니다.[85] 올레 미스 유니온(1976)과 라마 홀(1977)이라는 두 개의 거대한 현대식 건물은 대학의 전통적인 건축물과 분리되어 논란을 일으켰습니다.[86] 1998년 거트루드 C. 포드 재단은 거트루드 C를 설립하기 위해 2천만 달러를 기부했습니다. 포드 공연 예술 센터는 캠퍼스 내에서 공연 예술에만 전념하는 최초의 건물이었습니다.[87][88] 2020년 현재 대학은 202,000 평방 피트(18,800m2) 규모의 STEM 시설을 건설하고 있으며, 이는 캠퍼스 역사상 가장 큰 단일 건설 프로젝트입니다.[89] 이 대학은 옥스퍼드에 있는 역사적인 부동산뿐만 아니라 미국 미술, 고전 고미술, 남부 민속 예술의 컬렉션으로 구성된 미시시피 대학교 박물관을 소유하고 운영합니다.[90] 올레 미스는 또한 메인 캠퍼스 북쪽에 위치한 유니버시티-옥스퍼드 공항을 소유하고 있습니다.[76]

일본의 주말학교인 North Missippi Japan Supplementary School은 Ole Miss와 연계되어 운영되며, 교내에서 수업이 진행됩니다.[91][92] 2008년에 문을 열었고 여러 일본 기업과 대학이 공동으로 설립했습니다. 많은 아이들이 블루스프링스에 있는 토요타 시설의 직원인 부모를 가지고 있습니다.[93]

위성 캠퍼스

1903년, 미시시피 대학교 의과대학이 옥스퍼드 캠퍼스에 설립되었습니다. 단 2년의 의학 과정만 제공했습니다. 학생들은 학위를 마치기 위해 주 밖의 의대에 다녀야 했습니다.[95] 이런 형태의 의학교육은 1955년 미시시피주 잭슨의 164에이커(66ha) 부지에 미시시피대학교 의료센터(UMMC)가 설립되고 의과대학이 이전할 때까지 계속되었습니다.[96] 1956년에 간호학교가 설립되었고 그 이후로 다른 보건 관련 학교들이 추가되었습니다. 2021년[update] 현재, UMC는 의학 및 대학원 학위를 제공합니다.[95] 이 대학에는 의료 센터 외에도 분빌,[97] 드소토,[98] 그레나다,[99] 랭킨,[100] 투펠로에 위성 캠퍼스가 있습니다.[101]

행정 및 조직

| 학교 | 설립된 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 교양대학 | 1848 | [102] |

| 법학전문대학원 | 1854 | [10] |

| 공과대학 | 1900 | [103] |

| 교육대학 | 1903 | [104] |

| 의과대학 | 1903 | [95] |

| 약학대학 | 1908 | [105] |

| 경영대학원 | 1917 | [106] |

| 신문방송학과 | 1947 | [107] |

| 간호대학 | 1948 | [108] |

| 보건대학원 | 1971 | [109] |

| 치의학전문대학원 | 1975 | [110] |

| 패터슨 회계대학 | 1979 | [111] |

| 응용과학대학 | 2001 | [112] |

| 보건대학원대학교 | 2001 | [113] |

대학의 학과

미시시피 대학교는 15개의 학교로 구성되어 있습니다.[114] 가장 큰 학부는 교양대학입니다.[102] 대학원에는 법학전문대학원, 경영학대학원, 공과대학원, 의과대학원 등이 있습니다.[115]

행정부.

미시시피 대학의 최고 행정 책임자는 글렌 보이스가 2019년부터 맡고 있는 총장입니다.[116][117] 총장은 연구 및 대학 간 운동과 같은 분야를 관리하는 부총장의 지원을 받습니다. 프로보스트는 대학의 학사 업무를 감독하고,[118] 학장은 각 학교와 일반학 및 우등 대학을 감독합니다.[119] 교수회 상원은 행정부에 조언합니다.[120]

미시시피주 고등 교육 기관의 수탁 기관은 미시시피 대학교와 주의 다른 7개 공공 중등 교육 기관의 정책 및 재정 감독을 담당하는 헌법상의 관리 기관입니다. 이사회는 12명의 구성원들로 구성되어 있는데, 이들은 9년의 임기를 가지며 주의 3개 대법원 구역을 대표합니다. 이사회는 정책을 집행하는 고등교육청장을 임명합니다.[121]

재무

2021년[update] 4월 현재 미시시피 대학교의 기부금은 7억 7,500만 달러였습니다.[122] 2019 회계연도의 대학 예산은 5억 4천만 달러가 넘었습니다.[123] 운영 수익의 13% 미만이 미시시피 주의 재정 지원을 받고 있으며,[122] 대학은 민간 기부금에 크게 의존하고 있습니다. 포드 재단은 옥스퍼드 캠퍼스와 UMC에 거의 6천 5백만 달러를 기부했습니다.[124]

학술 및 프로그램

미시시피 대학교는 등록 수 기준으로 주에서 가장 큰 대학이며 주의 대표적인 대학으로 여겨집니다.[125][126][127][128] 2015년 학생-교수 비율은 19:1이었습니다. 학급 중 47.4%가 20명 미만의 학생을 보유하고 있습니다. 가장 인기 있는 과목은 마케팅, 교육 및 교육, 회계, 재무, 제약 과학 및 행정입니다.[129] 학사 학위를 받으려면 합격 학점과 누적 평점 2.0 이상의 학기 시간을 가져야 합니다.[130]

이 대학은 또한 박사 학위와 예술, 과학 및 미술 석사와 같은 대학원 학위를 제공합니다.[131] 이 대학은 중요한 공립학교의 교사들을 교육하는 무료 대학원 프로그램인 미시시피 교사단을 유지하고 있습니다.[132]

1905년에 처음으로 수여된 테일러 메달은 교수진에 의해 지명된 우수한 학생들에게 수여됩니다. 메달은 1871년에 졸업한 마커스 엘비스 테일러(Marcus Elvis Taylor)를 기리기 위해 명명되었으며, 각 학급의 1% 미만에게 수여됩니다.[26]

조사.

Ole Miss는 "R1: 박사과정 대학 – 매우 높은 연구 활동"으로 분류됩니다.[133][134] 국립과학재단에 따르면 2018년 이 대학은 연구 개발에 1억3700만 달러를 지출하여 국내 142위를 차지했습니다.[135] 전국 바다그랜트 프로그램에 참여하는 33개 단과대학 중 하나이며, 전국 우주그랜트 대학 및 펠로우십 프로그램에 참여하고 있습니다.[136] 1948년부터 이 대학은 오크리지 연합 대학의 회원이 되었습니다.[137]

1963년 제임스 하디(James Hardy)가 이끄는 미시시피 대학 메디컬 센터 외과 의사들은 세계 최초로 인간 폐 이식 수술을 했고, 1964년에는 세계 최초로 동물 대 인간 심장 이식 수술을 했습니다. 하디가 지난 9년 동안 영장류 연구로 이루어진 이식을 연구했기 때문에 침팬지의 심장이 이식에 사용되었습니다.[138][139]

1965년, 약학대학은 약학 연구에 사용하는 약용식물원을 설립했습니다.[140] 1968년부터 이 학교는 미국에서 유일하게 합법적인 마리화나 농장과 생산 시설을 운영해 왔습니다. 국립 약물 남용 연구소는 승인된 연구 연구에 사용하고 자비로운 조사 신약 프로그램에 참여한 생존 의료용 마리화나 환자 7명에게 배포하기 위해 대학의 대마초 생산에 계약합니다.[141] 이 시설은 의학 연구자들이 식품의약국 승인 테스트를 수행하는 데 사용할 수 있는 유일한 마리화나 공급원입니다.[142][143]

1986년 의회가 설립한 국립 물리 음향 센터(NCPA)는 캠퍼스 내에 위치하고 있습니다.[76][115][144] NCPA는 연구를 수행하는 것 외에도 미국 음향학회 기록물을 보관하고 있습니다.[144] 이 대학은 또한 223개의 연구 연못을 포함하고 장기적인 생태 연구를 지원하는 미시시피 대학 필드 스테이션을 운영하고 [145]있으며 미시시피 슈퍼컴퓨팅 연구 센터와 미시시피 법 연구소를 주최하고 있습니다.[115][146][147][148] 2012년, 이 대학은 "미시시피 대학 연구를 상업화하는 기업을 환영하는" 연구 공원인 인사이트 파크를 완공했습니다.[149][150]

특별 프로그램

저명한 학자들의 강의로 구성된 미시시피 대학의 우등 교육은 1953년에 시작되었습니다. 1974년에 이 프로그램이 University Scholars Program이 되었고, 1983년에 University Honors Program이 만들어졌고 Honors-core 과정이 제공되었습니다.[151] 1997년 넷스케이프 CEO 짐 바크스데일과 아내 샐리는 540만 달러를 기부하여 수석 논문인 캡스톤 프로젝트를 제공하는 Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College(SMBHC)[152]를 설립하고 장학금을 받았습니다.[151]

1977년, 이 대학은 인문 대학에 있는 국립 인문 기금의 자금으로 남부 문화 연구 센터를 설립했습니다. 이 센터는 남부 역사와 문화에 대한 학제 간 연구를 제공합니다.[153] 2000년에 이 대학은 동문이자 당시 미국 상원 다수당 지도자였던 트렌트 로트의 이름을 딴 트렌트 로트 리더십 연구소를 설립했습니다. 이 연구소는 MCI Inc., Lockheed Martin 및 기타 회사의 대규모 기업 기부금으로 자금을 지원받았습니다.[154] 이 연구소는 리더십 이니셔티브 외에도 공공 정책 리더십 학사 학위를 제공합니다.[155]

정보 및 보안 연구 센터(CISS)는 정보 분석에 관한 학술 프로그래밍을 제공하고 정부, 민간 및 학계 파트너와 함께 응용 연구 및 컨소시엄 구축에 참여합니다.[156] 2012년, 미국 국가 정보국 국장은 CISS를 학업 우수성 정보 커뮤니티 센터(CAE)로 지정하여 미국에서 29개 대학 프로그램 중 하나가 되었습니다.[157] 그 밖의 특별 프로그램으로는 2008년에 대학과 도요타가 공동으로 설립한 Haley Barbour Center for Manufacturing Excellence와 중국어 플래그십 프로그램(간체 중국어: 中文旗舰项目, 번체 중국어: 中文旗艦項目, 피닌어: Zhongwen Qijián Xiangm ù)이 있습니다. 1998년에 설립된 크로프트 국제학 연구소는 미시시피에서 유일한 국제학 학부 프로그램을 제공합니다.[160]

미시시피 대학교는 SEC Academic Consortium의 회원이며, 그 이후 SECU로 이름이 바뀌었습니다. 이 협력 이니셔티브는 동남권 회의의 회원 대학들 간의 연구, 장학금 및 성과를 촉진하기 위해 고안되었습니다.[161][162] 2013년 조지아 대학교와 UGA Bioenergy Systems Research Institute가 주관하고 주도한 조지아주 애틀랜타에서 열린 재생에너지에 관한 SEC Symposium에 대학이 참여했습니다.[163]

2021년 배우 모건 프리먼과 린다 키나 교수는 미시시피 대학에 100만 달러를 기부하여 법 집행 교육을 제공하고 법 집행과 지역 사회 간의 참여를 개선하고자 하는 증거 기반 치안 및 개혁 센터를 설립했습니다.[164][165]

순위 및 포상

| 학적 순위 | |

|---|---|

| 국가의 | |

| 포브스[166] | 231 |

| THE / WSJ[167] | 278 |

| U.S. 뉴스 & 월드 리포트[168] | 163 |

| 워싱턴 월간지[169] | 304 |

U.S. News & World Report의 2023년 순위에서 미시시피 대학은 국립 대학 중 공동 163위, 공립 대학 중 공동 88위를 차지했습니다.[170] Bloomberg Businessweek는 2023년 경영대학원의 전문 MBA 프로그램을 전국적으로 72위,[171] 온라인 MBA 프로그램을 상위 25위 안에 들었습니다.[172] Public Accounting Report에 따르면 2018년[update] 기준으로 Patterson School of Accountancy의 세 학위 프로그램은 모두 상위 10개 회계 프로그램에 속했습니다.[173]

2012년부터 고등 교육 연대기는 미시시피 대학교를 "일하기 좋은 훌륭한 대학" 중 하나로 선정했습니다. 크로니클의 "The Academic Workplace" 연례 보고서에 발표된 2018년 결과에서 이 대학은 조사 대상 253개 단과대에서 수상한 84개 기관 중 하나였습니다.[174] 2018년, 이 대학의 캠퍼스는 SEC에서 두 번째로 안전하고 미국에서 가장 안전한 캠퍼스 중 하나로 선정되었습니다.[175]

2019년 현재 대학에는 27명의 Rhodes Scholars가 있습니다.[176] 1998년부터 골드워터 장학생 10명, 트루먼 장학생 7명, 풀브라이트 장학생 18명, 마셜 장학생 1명, 우달 장학생 3명, 게이츠 케임브리지 장학생 2명, 미첼 장학생 1명, 보렌 장학생 19명, 보렌 펠로우 1명, 독일 총리 장학생 1명이 있습니다.[177]

사람

학생단체

2020-2021학년도 현재 학생회는 15,546명의 학부생과 3,122명의 대학원 과정으로 구성되어 있습니다.[178] 학부생의 약 57%가 여성이었습니다.[179][178] 2020년 말 현재, 소수민족은 신체의 24.3%를 구성하고 있습니다.[180] 학생들의 평균 가족 수입은 116,600달러이고, 절반이 넘는 학생들이 상위 20%로부터 옵니다. 뉴욕 타임즈에 따르면, 미시시피 대학은 선택적인 공립학교들 중 경제적인 상위 1퍼센트의 학생들의 비율이 7번째로 높습니다.[181] US 뉴스에 따르면 졸업생의 평균 초봉은 47,700달러입니다.[182]

비록 54 퍼센트의 학생들이 미시시피 출신이지만,[53] 학생들의 신체는 지리적으로 다양합니다. 2020년 말 현재 이 대학의 학부생은 미시시피주의 82개 카운티, 49개 주, 컬럼비아 특별구, 86개 국가를 대표합니다.[180] 학생들의 성공과 만족도를 나타내는 지표인 신입생 평균 유지율은 85.7%입니다.[180] 2020년에는 1,100명 이상의 전학생이 학생 단체에 포함되었습니다.[178]

교수진

2020-2021학년도 기준으로 UMC를 제외한 1,092명의 교수가 있으며, 이 중 424명이 재직 중입니다. 이때 남성 교수는 592명, 여성 교수는 500명이었습니다.[183]

고전 연구에 대한 초기의 강조와 함께, 조지 터커 스테인백, 윌슨 게인스 리차드슨, 윌리엄 헤일리 윌리스를 포함한 많은 유명한 고전가들이 미시시피 대학에서 교수직을 맡았습니다.[184][185] 고대 도시 올리누스를 발견한 것으로 알려진 고고학자 데이비드 무어 로빈슨도 이 대학에서 고전을 가르쳤습니다.[186][187] 전 미시시피 주지사 로니 머스그로브는 정치학 강사였고,[188] 카일 던컨은 미국 제5순회 항소법원에 임명되기 전에 조교수였습니다.[189][190] 랜던 갈랜드는 밴더빌트 대학교의 초대 총장이 되기 전 천문학과 철학을 가르쳤습니다.[191][192] '하자드 공작'에 대한 작업으로 가장 잘 알려진 배우 제임스 베스트는 거주 중인 예술가였습니다.[193] 로버트 Q. 국립보건원장 마스턴은 의과대학 학장을 역임했고,[194][195] 유진 W. 토양과학의 아버지로 여겨지는 힐가드는 올레 미스에서 화학을 가르쳤습니다.[196] 다른 주목할 만한 과학 교수진으로는 심리학자 데이비드 H. 발로우(David H. Barlow)와 물리학자 맥 A(Mack A)가 있습니다. 브리질.[197][198]

주목할 만한 동문

윌리엄 포크너 [200]외에도 미시시피 대학에 다녔던 주목할 만한 작가로는 플로렌스 마스,[201] 패트릭 D 등이 있습니다. 스미스,[202] 스타크 영,[203] 존 그리샴.[204] 주목할 만한 저널리스트 졸업생으로는 보스턴 글로브의 특파원 커티스 윌키와 방송 저널리스트 셰퍼드 스미스가 있습니다.[205][206] 영화계 동문으로는 에미상을 수상한 배우 제럴드 맥레이니와 헬프의 감독 테이트 테일러가 있습니다.[207][208] 이 대학에서 공부한 음악가로는 모스 앨리슨과 그래미상 수상자인 글렌 발라드가 있습니다.[209][210] 운동선수 졸업생에는 그랜드 슬램 테니스 12회 챔피언 마헤시 부파티,[211] NFL 쿼터백 아치 매닝과 일라이 매닝, 뉴욕 양키스 포수 제이크 깁스,[212] NFL 공격 라인맨이자 영화 블라인드 사이드의 주제인 마이클 오허가 포함됩니다.[213] 또한 3명의 미스 아메리카와 1명의 미스 USA가 동문에 포함되어 있습니다.[214][215][216]

미시시피 대학교의 동문은 미국 상원의원 5명과 주지사 10명입니다.[217] 다른 공무원 졸업생들에는 미시시피 대법원장 시드니 M. 스미스와 빌 월러 주니어,[218][219] 미국 해군 장관 레이 매버스,[220][221] 백악관 언론 비서 래리 스피크스,[222] 도미니카 총리 루스벨트 스케릿이 포함되어 있습니다.[223] 주목할 만한 학자로는 포모나 칼리지 총장 E가 있습니다. 윌슨 리옹,[224] 퓰리처상 수상 하버드 교수 토마스 K. 맥크로우와 머서 대학교 총장 제임스 브루턴 감브렐.[225][226] 주목할 만한 의사로는 아서 가이튼,[227] 미국 의학 협회장 에드워드 힐,[228] 토마스 F 등이 있습니다. Frist Sr., Hospital Corporation of America의 공동 설립자.[229] 동문인 윌리엄 파슨스는 나사의 스테니스 우주 센터장을 역임했고 이후 케네디 우주 센터장을 역임했습니다.[230]

육상

미시시피 대학교의 운동팀들은 전미 대학 체육 협회(NCAA), 남동부 컨퍼런스(SEC), 디비전 I에 올레 미스 레블스로 참가합니다.[115][231] 미시시피 대학교의 여자 대표팀 운동팀에는 농구, 크로스 컨트리, 골프, 소총, 축구, 소프트볼, 테니스, 육상, 배구가 있습니다. 남자 대표팀은 야구, 농구, 크로스 컨트리, 축구, 골프, 테니스, 육상입니다.[232]

1893년, 알렉산더 본듀란트 교수는 그 대학의 축구팀을 조직했습니다.[233] 대학 운동부들이 이름을 받기 시작하면서 1929년 대회 결과에서 "미시시피 홍수"라는 이름이 선정되었습니다. 하지만 1927년 미시시피 대홍수의 지속적인 피해로 인해 1936년 "반군"으로 이름이 바뀌었습니다.[234] 대학 축구의 첫 황금시간대 방송은 1969년 올레 미스 경기였습니다.[235] 팀은 6번의 SEC 챔피언십에서 우승했습니다.[236] 주요 라이벌로는 올 미스가 매그놀리아볼과 에그볼에서 각각 맞붙는 루이지애나 주립대와 미시시피 주립대가 있습니다.[237][238] 다른 경쟁사로는 Tulane과 Vanderbilt가 있습니다.[239][240] 쿼터백인 축구 동문 아치와 일라이 매닝은 각각의 등번호인 시속 18마일과 10마일로 제한된 속도로 교내에서 영예를 안았습니다.[241]

축구 외에서, 올레 미스 베이스볼은 7번의 SEC 챔피언십과 3번의 SEC 토너먼트에서 우승했습니다.[242] 그들은 대학 월드 시리즈에서 6번 출전했고,[243] 2022년 시리즈에서 우승했습니다.[244] 남자 테니스 팀은 SEC 종합 우승 5회, NCAA 싱글 챔피언 데빈 브리튼 1회를 차지했습니다.[245][246]

여자 농구팀이 SEC 종합 우승을 한 번 했습니다.[247] 주목할 만한 전직 선수로는 2007년 WNBA 드래프트에서 3순위로 지명된 미국 증권거래위원회(SEC) 기록을 보유한 [248]아르민티 프라이스와 1986년 올해의 미국 증권거래위원회(SEC) 여성 선수이자 1988년 올림픽 금메달리스트인 제니퍼 길롬 등이 있습니다.[249] 남자 농구는 SEC 토너먼트에서 두 번 우승했습니다.[250] 2021년, 올레 미스 여자 골프가 첫 NCAA 디비전 I 여자 골프 챔피언십에서 우승했습니다.[251]

학생생활

전통

준비됐나요?

아싸! 젠장 맞다!

핫티 토디, 세상에,

우리가 대체 누구죠? 이것 봐!

플림 플램, 빔밤

올레 미스 바이 빌어먹을!

— The Hotty Toddy chant[252]

캠퍼스에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 인사말은 "Hotty Toddy!"이며, 이는 구호에도 사용됩니다. 이 문구는 명시적인 의미가 없으며 그 기원을 알 수 없습니다.[252] 이 구호는 1926년에 처음 출판되었지만, "Hotty Toddy"는 "Heighty Tighty"라는 철자로 쓰여졌습니다. 이 초기 철자는 버지니아 공대의 연대 밴드인 The Heighty Tighty에서 유래되었다고 주장하게 만들었습니다.[252][253] 다른 제안된 기원은 속물을 의미하는 "호티 투티"[254][253]와 알코올 음료 핫 토디입니다.[254]

축구 경기 날, 10 에이커(4.0 헥타르)의 나무로 이루어진 그로브(Grove)는 정교한 테일게이트 전통을 가지고 있습니다.[78][255] 뉴욕 타임즈에 따르면, "아마도 의식화된 게임 전 즐거움에 대한 단어는 없을 것입니다... '꼬리 맞추기'는 분명히 정당한 것이 아닙니다." 이 전통은 1991년 자동차가 그로브에서 금지되었을 때 시작되었습니다.[78] 각 게임 전에 그로브 곳곳에 2,000개 이상의 빨간색과 파란색 쓰레기통이 놓여 있습니다. 이 행사는 "쓰레기통 금요일"이라고 알려져 있습니다. 각 통에는 테일게이트 지점이 표시되어 있습니다.[256] 그 장소들은 2,500개의 피난처가 있는 "텐트 도시"를 건설하는 꼬리 관리자들에 의해 주장됩니다.[78][255] 많은 텐트들은 사치스럽고 샹들리에와 훌륭한 중국이 특징이며 일반적으로 남부 요리의 식사를 제공합니다.[255] 인파를 수용하기 위해 이 대학은 "Hotty Toddy Poties"로 알려진 18륜차 플랫폼에 정교한 휴대용 욕실을 유지하고 있습니다.[78]

학생단체

미시시피 대학의 최초의 인가 학생 단체인 문학회, 헤르매안 협회와 파이 시그마 협회는 1849년에 설립되었습니다. 참석이 의무화된 주간 회의는 1853년까지 리세움에서, 그리고 나서 예배당에서 열렸습니다.[257] 대학에서 수사학을 강조하면서 매달 첫째 주 월요일에 학생들이 조직한 출판물이 인기를 끌었습니다. 학생들이 제퍼슨 데이비스(Jefferson Davis)와 윌리엄 L(William L)과 같은 방문 정치인들의 연설에 참석할 수 있도록 학업이 때때로 취소되었습니다. 샤키.[258]

1890년대에는 교내에서 과외 활동과 비지적 활동이 확산되었고, 웅변과 현재 자발적인 문학 사회에 대한 관심이 감소했습니다.[259] 20세기 전환기 학생 단체로는 코티온 클럽, 엘리트 스태그 클럽, 저먼 클럽 등이 있습니다.[260] 1890년대에 지역 YMCA는 M-Book에 조직 목록을 발표하기 시작했습니다.[260] 2021년 현재 핸드북은 여전히 학생들에게 제공되고 있습니다.[260][261]

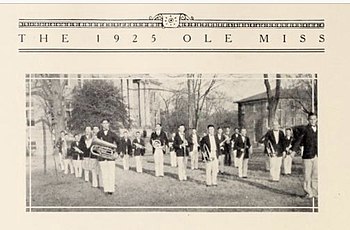

1917년에 설립된 ASB([262]Associated Student Body)는 대학의 학생 정부 기관입니다. 봄 학기에는 학생들이 ASB 상원의원으로 선출되고 가을에는 열린 의석 선거에서 남은 의석이 투표됩니다. 상원의원은 그리스 의회와 스포츠 클럽과 같은 등록된 학생 단체를 대표하거나 자신의 학교를 대표하기 위해 출마할 수 있습니다.[263] 미시시피 대학의 행진 밴드인 The Pride of the South는 콘서트와 운동 경기에서 공연합니다. 이 밴드는 1928년에 공식적으로 조직되었지만,[264] 그 이전에는 학생 감독이 이끄는 소규모 조직으로 존재했습니다.[265] 파이 베타 카파(Phi Beta Kappa) 챕터는 2001년에 설립되었습니다.[177]

어메니티

약 5,300명의 학생들이 13개의 레지던스 홀, 2개의 레지던스 대학, 2개의 아파트 단지에서 캠퍼스에 살고 있습니다.[266] 학생들은 1학년 동안 교내에서 생활해야 합니다.[115] 레지던스 홀 내에서 커뮤니티 보조원으로 지정된 학생들은 정보를 제공하고 문제를 해결합니다.[267] 20세기 초, 대학은 결혼한 학생들을 위해 오두막을 제공했습니다.[260] 1947년, Vet Village는 제2차 세계대전 참전용사 지원자들의 급증에 대비하기 위해 건설되었습니다.[268]

미시시피 대학은 학생, 교직원 및 직원들에게 무료로 제공하는 셔틀 시스템인 옥스포드 대학 교통편을 제공합니다.[269] 2020년 초, 스타쉽 테크놀로지스는 캠퍼스에 30대의 로봇으로 구성된 자동화된 음식 배달을 도입했습니다. 이 시스템은 SEC 학교 중 최초의 시스템이었습니다.[270][271]

캠퍼스 내 외식 서비스 케이터링 앳 UM 및 레벨 마켓은 미시시피 주에서 유일하게 인증된 친환경 레스토랑입니다.[272] 2019년에 이 대학은 체육관, 실내 등반 벽, 농구장 및 기타 서비스를 포함하는 98,000 평방 피트 (9,100 미터2)의 레크리에이션 센터를 열었습니다.[273]

그리스인의 생활

미시시피 대학의 그리스인 생활은 32개의 단체와 약 7,000명의 학생들로 구성되어 있습니다.[274] 미시시피 대학의 그리스 사회들은 1930년대에 연방 기금으로 건설된 패러티 로우와 소러티 로우를 따라 거주하고 있습니다.[275]

1848년 미시시피 대학에서 설립된 레인보우 박애회는 남부에서 처음으로 설립된 박애회였습니다.[276][277][note 3] 이 대학에서 설립된 다른 초기 친목회로는 델타 카파 엡실론(1850), 델타 카파(1853), 델타 Psi(1854), 엡실론 알파(1855)가 있습니다.[257] 1900년까지 미시시피 대학교 학생들의 대다수는 친목회나 여대생들이었습니다. 비회원 학생들은 교내에서 소외감을 느꼈고 회원과 비회원 간의 긴장이 고조되었습니다. University Magazine은 그리스 사회를 "어느 대학에서나 성장한 가장 악랄한 기관"이라고 비난했습니다.[278] 1902년, 교우회로부터 퇴짜를 맞은 가난한 학생 리 러셀이 이사회에 나타나 그리스 사회를 비판했습니다.[279][note 4] 이에 이사회는 비회원 학생들이 계속해서 따돌림을 당하면 그리스인들의 생활을 폐지하겠다고 위협했습니다. 1903년, 그리스계 회원들과 비회원 학생들이 "전투에서 만날" 준비를 하고 있다는 소문이 나타났습니다.[280] 이 문제를 해결하기 위해 여러 번의 주 입법 조사가 진행되었습니다.[281] 1912년부터 1926년까지 주 전체의 반(反)동족 입법으로 인해 이 대학의 모든 그리스인 생활이 중단되었습니다.[282][283]

당혹스러운 친목 행사에 대한 더 큰 단속의 일환으로, 제럴드 터너 수상은 1984년 전통적인 새우와 맥주 축제를 끝냈습니다.[284] 1988년, 흑인 친목회인 파이 베타 시그마는 방화범들이 그들의 집을 불태웠을 때, 백인 친목회 행에 있는 집으로 이사할 준비를 하고 있었습니다. 한 동문이 또 다른 집을 사는 것을 도왔고 두 달 후에 박애로우가 통합되었습니다.[285] 1989년 한 사건에서, 친목회 회원들은 역사적으로 흑인인 러스트 칼리지에서 인종차별적 비방이 그려진 벌거벗은 학생들을 떨어뜨렸습니다.[286] 2014년에는 3명의 친목회원이 메러디스 동상에 올가미와 남부연합 상징물을 올렸고,[287][288] 2019년에는 친목회원들이 에밋 틸 역사적 표지 앞에서 총을 들고 포즈를 취했습니다.[289]

미디어

미시시피 대학의 최초의 학생 출판물은 1856년에 설립되어 문학 협회에 의해 출판된 University Magazine입니다.[290] 미시시피 대학과 미시시피 주 사이의 경쟁은 미시시피 대학이 "품위가 부족하다"고 쓴 미시시피 주 출판물에 대한 1895년 University Magazine의 비난에서 비롯되었습니다.[291] 최초의 학생 신문인 University Record는 1898년에 발행을 시작했습니다; 그것과 잡지는 재정적으로 어려움을 겪었고 1902년에 중단되었습니다.[26]

1907년, YMCA와 학생 운동 단체는 대학의 신문을 Varsity Voice로 부활시켰습니다.[26] 1911년 이 신문은 학생들이 발행하는 또 다른 신문인 데일리 미시시피로 대체되었습니다.[26][292] 이 신문은 편집상 독립적이며 주에서 유일한 일간 대학 신문입니다. 이 논문은 또한 보충적인 내용과 함께 TheDMonline.com 로 온라인에 게재됩니다.

1980년에 설립된 뉴스워치는 학생들이 제작한 생방송 뉴스캐스트이며 라파예트 카운티의 유일한 지역 뉴스캐스트입니다.[293] 미시시피 대학교는 1989년에 방송을 시작한 WUMS 92.1 Rebel Radio를 소유 및 운영하고 있으며, 미국에서 몇 안 되는 대학 운영 상업 FM 라디오 방송국 중 하나입니다.[294]

참고자료 및 참고자료

메모들

인용문

- ^ https://adminfinance.olemiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/74/2023/11/Revenues-and-Expenditures.pdf

- ^ "IPEDS-University of Mississippi".

- ^ Journal, BLAKE ALSUP Daily. "MSU, USM see increased enrollment as state numbers decline". Daily Journal. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ a b 파울러(1941), 페이지 213.

- ^ a b c 코호다스(1997), 페이지 5.

- ^ a b c d e f "University of Mississippi". The Mississippi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Andrews, Becca (July 1, 2020). "The Racism of "Ole Miss" Is Hiding in Plain Sight". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "History". University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ "University of Mississippi Main Campus". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "History". School of Law. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 3, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ a b 코호다스(1997), 페이지 6-7.

- ^ 코호다스(1997), 페이지 7.

- ^ 코호다스(1997), 페이지 8.

- ^ a b 코호다스(1997), 페이지 9.

- ^ "Haunted History". October 31, 2014.

- ^ 코호다스(1997), p. 10.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 112쪽.

- ^ a b 코호다스(1997), 페이지 11.

- ^ Roland, Dunbar (December 11, 2023). "The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi, Volume 4". Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ 코호다스(1997), 페이지 18.

- ^ a b "History". Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, Elliott C. (July 27, 2021). "The Battle over Ole Miss: Why a flagship university has stood behind a nickname with a racist past". CNN. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 168-169쪽.

- ^ 카바니스(1949), 페이지 129.

- ^ 이글스(2009), 페이지 17.

- ^ a b c d e 싼싱(1999), 페이지 168.

- ^ Elmore, Albert Earl (October 24, 2014). "Scholar Finds Evidence 'Ole Miss' Train Key in Establishing University Nickname". Hotty Toddy. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 169.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 8장.

- ^ a b 배럿(1965), 페이지 23.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 240.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Administration in World War II". HyperWar Foundation. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Roberts & Klibanoff (2006), 61-62쪽.

- ^ a b 브라이언트(2006), 페이지 60.

- ^ 코호다스(1997), 114쪽.

- ^ 코호다스(1997), 페이지 112.

- ^ Roberts & Klibanoff(2006), 페이지 276.

- ^ 헤이만(1998), 페이지 282.

- ^ Roberts & Klibanoff(2006), 페이지 288.

- ^ "Ross Barnett, Segregationist, Dies; Governor of Mississippi in 1960's". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 7, 1987. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Marshals Mark 50th Anniversary of the Integration of 'Ole Miss'". U.S. Marshals Service. U.S. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 302쪽.

- ^ Roberts & Klibanoff (2006), 페이지 292.

- ^ 스킵스(2005), p. 102.

- ^ Roberts & Klibanoff(2006), 페이지 291-292.

- ^ 스킵스(2005), p. 105.

- ^ 위컴(2011), 102-112쪽.

- ^ a b "The States: Though the Heavens Fall". Time. October 12, 1962. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Roberts & Klibanoff(2006), 페이지 297.

- ^ 스킵스(2005), 페이지 120-121.

- ^ "1962: Mississippi race riots over first black student". BBC News. October 1, 1962. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 321.

- ^ a b "Fall 2019-2020 Enrollment". Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Polly M. Rettig and John D. McDermott (March 30, 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: William Faulkner Home, Rowan Oak". National Park Service. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: 저널 인용은 다음과 같습니다.journal=(도움말) - ^ "History". Rowan Oak. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Luesse, Valerie Fraser (September 25, 2020). "The Haunted History of William Faulkner's Rowan Oak". Southern Living. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Boyer, Allen (June 3, 1984). "William Faulkner's Mississippi". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Byrd, Shelia Hardwell (September 21, 2002). "Meredith ready to move on". Athens Banner-Herald. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ Halbfinger, David M. (September 27, 2002). "40 Years After Infamy, Ole Miss Looks to Reflect and Heal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "Ole Miss dedicates civil rights statue". Deseret News. Associated Press. October 2, 2006. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Ford, Gene; Salvatore, Susan Cianci (January 23, 2007). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Lyceum (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2009.

- ^ Robertson, Campbell (September 30, 2012). "University of Mississippi Commemorates Integration". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Dewan, Shaila (September 23, 2008). "Debate Host, Too, Has a Message of Change". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ "Debates give University of Mississippi a chance to highlight racial progress". The Guardian. September 22, 2008. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021 – via McClatchy newspapers.

- ^ Martin, Michael (February 25, 2010). "Ole Miss Retires Controversial Mascot". NPR. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Malinowski, Erik (September 8, 2010). "Ole Miss' Admiral Ackbar Campaign Fizzles". Wired. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Hartstein, Larry; Tagami, Ty (March 1, 2010). "Admiral Ackbar for Ole Miss mascot spurs backlash". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Stevens, Stuart (October 31, 2015). "Between Ole Miss and Me". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Ole Miss adopts Landshark as new official mascot for athletic events". ESPN. October 6, 2017. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Maddie. "Ole Miss unveils its Landshark mascot, a melding of Rebels history and Hollywood design". The Clarion Ledger. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Suss, Nick (August 12, 2022). "How Lane Kiffin's dog, Juice, has become the face of Ole Miss football". USA Today. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ King, Ben (October 5, 2022). "Lane Kiffin's Dog 'Juice' Agrees to NIL Deal With The Grove Collective". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ McLaughlin, Eliott C. (October 26, 2015). "Ole Miss removes state flag from campus". CNN. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Pettus, Emily Wagster (July 14, 2020). "Ole Miss moves Confederate statue from prominent campus spot". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "2020 census - census block map: University CDP, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

Univ of Mississippi (blue text)

"2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Oxford city, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 1 (PDF p. 2/5). Retrieved August 14, 2022.Univ of Mississippi

- ^ a b c d e f g "About the University of Mississippi". UM Catalog. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Seph (April 17, 2013). "The Grove at Ole Miss: Where Football Saturdays Create Lifelong Memories". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Gentry, James K. (October 31, 2014). "Tailgating Goes Above and Beyond at the University of Mississippi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 91쪽.

- ^ "Barnard Observatory". NPGallery Digital Asset Management System. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 315.

- ^ "Frank Gates Dies Here; Rites Today". The Clarion Ledger. January 3, 1975. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gates, Frank P., Co. (b.1895 - d.1975)". Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 252-253쪽.

- ^ "Kennon Observatory". Department of Physics and Astronomy. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 315-316.

- ^ "About". Gertrude C. Ford Center for the Performing Arts. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 350.

- ^ Hahn, Tina H. (February 8, 2020). "Record-setting construction project at Ole Miss: Business leaders commit to STEM education". The Clarion Ledger. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "History". The University of Mississippi Museum. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "2022년 2월 17일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 일본보충학교." OGE-US Japan Partnership, 미시시피 대학교 2015년 2월 25일 회수.

- ^ "周辺案内 2022년 2월 17일 Wayback Machine에서 보관." 미시시피 대학교의 North Mississippi Japan Supplementary School. 2015년 4월 1일 회수.

- ^ McArthur, Danny (October 24, 2021). "A wide perspective': Learning Japanese, American culture through language and education". Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Sandy and John Black Pavilion". Ole Miss Sports. University of Mississippi. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c "History". University of Mississippi Medical Center. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 162쪽, 265-266쪽.

- ^ "Why Ole Miss and UM-Booneville?". UM, Booneville. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Why Ole Miss and UM-DeSoto?". UM, DeSoto. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Why Ole Miss and UM-Tupelo?". UM, Grenada. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Why Ole Miss and UM-Rankin?". UM, Rankin. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Why Ole Miss and UM-Tupelo?". UM, Tupelo. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Mission & History of the College of Liberal Arts". College of Liberal Arts. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "History". Ole Miss Engineering. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "History". School of Education. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "Welcome from Dean David D. Allen". School of Pharmacy. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "History". Ole Miss Business. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "School of Journalism and New Media". Academic Catalog. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "School of Nursing". School of Nursing. University of Mississippi Medical Center. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "School of Health Related Professions". School of Health Related Professions. University of Mississippi Medical Center. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "School of Dentistry". School of Dentistry. University of Mississippi Medical Center. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Message from the Dean". Patterson School of Accountancy. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "School of Applied Sciences". Academic Catalog. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "School of Graduate Studies in the Health Sciences". School of Graduate Studies in the Health Sciences. University of Mississippi Medical Center. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "University of Mississippi Main Campus". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "University of Mississippi". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (April 2, 2015). "University of Mississippi Chief, Whose Ouster Led to Protests, Rejects Offer to Stay". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Fowler, Sarah (October 4, 2019). "Who is Glenn Boyce? 5 things to know about the new Ole Miss chancellor". The Clarion Ledger. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to the Office of the Provost". Office of the Provost. University of Mississippi. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Senior Leadership". University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Faculty Senate". Faculty Senate. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Mississippi State Institutions of Higher Learning. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ a b "UM Endowment Builds to Record $775 Million". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. April 1, 2021. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "Current Educational and General and Auxiliary Enterprises Funds Summary of Expenditures By Departments and Objects" (PDF). University of Mississippi. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Hahn, Tina H. (October 16, 2020). "University Expands Student Union's Name to Pay Tribute to Ford". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "University system enrollment continues to remain steady". November 2, 2021. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ "Record-Breaking Enrollment Set UM Apart in 2023". University of Mississippi News. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ "Tuition and Fees at Flagship Universities over Time". The College Board. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "About UM: University of Mississippi". University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "The University of Mississippi 2015–2016 Fact Book" (PDF). Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning. University of Mississippi. January 15, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ^ "Academic Regulations". Academic Catalog. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Graduate School". Academic Catalog. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". Mississippi Teacher Corps. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 10, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". Carnegie Classifications. Center for Postsecondary Education. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (February 4, 2016). "In new sorting of colleges, Dartmouth falls out of an exclusive group". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program". NASA. July 28, 2015. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ "Oak Ridge Associated Universities". Research, Scholarship, Innovation and Creativity. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "History of Lung Transplantation". Emory University. April 12, 2005. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ "Surgery: First Heart Transplant". Time. January 31, 1964. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- ^ "The University of Mississippi Insight Park, Medicinal Plant Garden". CDFL. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Ahlers, Mike; Meserve, Jeanne (May 18, 2009). "Government runs nation's only legal pot garden". CNN. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Halper, Evan (May 28, 2014). "Mississippi, home to federal government's official stash of marijuana". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Erickson, Britt E. (June 29, 2020). "Cannabis research stalled by federal inaction". Chemical and Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Welcome". National Center for Physics Acoustics. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "The University of Mississippi Field Station". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. Ecological Society of America. 81: 82. 2000. doi:10.1890/0012-9623(2000)081[0082:FOFS]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0012-9623.

- ^ "Mississippi Center for Supercomputing Research". University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "REU Site: Ole Miss Physical Chemistry Summer Research Program". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "Mississippi Law Research Institute". University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "Research facility opens". The Clarion-Ledger. April 15, 2012. p. 20. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved July 22, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Insight Park". Insight Park. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "History". Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 347.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 318.

- ^ Bruni, Frank (May 8, 1999). "Donors Flock to University Center Linked to Senate Majority Leader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ "About the Institute". Trent Lott Leadership Institute. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to the Center for Intelligence and Security Studies (CISS)". Center for Intelligence and Security Studies. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ "Home". Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ "History". Haley Barbour Center for Manufacturing Excellence. University of Mississippi. January 31, 2020. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ "Introduction". Chinese Language Flagship Program. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ "2021 Best Mississippi Colleges for International Relations". Niche. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "SECU". SEC. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "SECU: The Academic Initiative of the SEC". SEC Digital Network. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "SEC Symposium to address role of Southeast in renewable energy". University of Georgia. February 6, 2013. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ Vera, Amir; Alsup, Dave; Lynch, Jamiel. "Morgan Freeman and a University of Mississippi professor donate $1M to college's policing program". CNN. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Morgan Freeman, professor give $1M for police training center at University of Mississippi". The Clarion Ledger. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2023". Forbes. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "2024 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "2023 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "University of Mississippi Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- ^ "Best B-Schools in US". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. September 14, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Ole Miss Online MBA Program Ranks in U.S. News Top 25". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. January 9, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Accountancy Programs Maintain Top 10 Standing". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. October 1, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "UM Again Named Among 'Great Colleges to Work For'". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. July 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Robust Approach to Campus Safety Places UM in National Rankings". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. March 12, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Jake (November 25, 2019). "Hudson named University of Mississippi's 27th Rhodes Scholar". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "History". About UM. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c "2020-2021 Mini Fact Book" (PDF). University of Mississippi. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Ole Miss Demographics & Diversity Report". College Factual. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Stone, Lisa (November 3, 2020). "UM Releases Enrollment for Fall 2020". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "University of Mississippi". The New York Times. January 18, 2017. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "University of Mississippi". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ "Fall 2020-2021 Enrollment". Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "From the Beginning to 'The War'". Department of Classics. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Willis, William Hailey". Database of Classical Scholars. Rutgers School of Arts and Science. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "Robinson, David Moore". Database of Classical Scholars. Rutgers School of Arts and Science. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Videocast – "David Moore Robinson: The Archaeologist as Collector" / News / The American School of Classical Studies at Athens". Department of Classics. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "Musgroves Expand Legacy with Gift". The University of Mississippi Foundation. September 13, 2013. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ Severino, Callie Campbell (September 28, 2017). "Who is Kyle Duncan?". National Review. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Jake (March 6, 2020). "Now in Session: U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals hears cases at Ole Miss". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Garland, Landon C. (Landon Cabell), 1810-1895". Social Networks and Archival Context. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Office". Office of the Chancellor. Vanderbilt University. February 2, 2010. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ Whittington, Ryan (April 7, 2015). "WTVA: Former UM Artist-in-Residence Passes Away". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ McGuigan, James W. (2005). "Robert Quarles Marston, M.D. 1923–1999". Transactions of the American Clinical & Climatological Association. 116: lx–lxiii. PMC 1473135. PMID 16555601.

- ^ "Brief Chronology". Regional Medical Programs. US National Library of Medicine. March 12, 2019. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ 피트먼 주니어(1985), 페이지 26.

- ^ "David Barlow". Boston University. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Acoustics Scientist Mack Breazeale Dies at 79". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. September 18, 2009. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1949". The Nobel Prize. Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on June 2, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Harpaz, Beth J. (April 19, 2017). "Exploring Oxford, Mississippi, from Faulkner's Rowan Oak to the Ole Miss campus". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ 달러(2015), 페이지 28.

- ^ 로이드(1980), 페이지 414.

- ^ 로이드(1980), 페이지 485.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 31, 2017). "Plot Twist! John Grisham's New Thriller Is Positively Lawyerless". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (October 14, 2011). "Of Parties, Prose and Football". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Guizerix, Anna (October 11, 2019). "Ole Miss Alum Shepard Smith leaves Fox News". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Hector, Emily (September 20, 2017). "Ole Miss' Gerald McRaney and Jack Pendarvis Take Home Emmy Awards". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Dodes, Rachel (August 5, 2011). "An Unknown, With Leverage". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Chinen, Nate (November 15, 2016). "Mose Allison, a Fount of Jazz and Blues, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "Grammy Winner Glen Ballard Inducted into UM Hall of Fame". College of Liberal Arts. University of Mississippi. March 16, 2009. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "Mahesh Bhupathi". Ole Miss Sports. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Seph (May 21, 2013). "Exclusive: Ole Miss Football, Baseball Great Jake Gibbs Shares Memories". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (November 18, 2009). "Two Films, Two Routes From Poverty". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Watkins, Billy (December 9, 2014). "Mary Ann Mobley, Mississippi's first Miss America, has died". The Clarion Ledger. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ McGrath, Anne (September 10, 1986). "'More Nervous This Year': Miss America 1986". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Guizerix, Anna (November 10, 2020). "Ole Miss graduate Asya Branch crowned Miss USA 2020". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ "Notable Alumni: Law and Politics". Ole Miss Alumni Organization. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Rowland, Dunbar (1923). The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi, Volume 5. Department of Archives and History. pp. 87–89. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "UM Law Alum, Chief Justice Waller Retires after 21 Years on MS Supreme Court". University of Mississippi School of Law. March 4, 2019. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Boyer, Peter J. (February 28, 1988). "The Yuppies of Mississippi; How They Took Over the Statehouse". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael S. (July 17, 2016). "Navy Secretary Ray Mabus Knows a Thing or 30 About First Pitches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Well, Martin (January 10, 2014). "Larry Speakes, former Reagan deputy press secretary, dies at 74". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Honourable Roosevelt Skerrit – Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Dominica". Commonwealth of Dominica Consulate of Greece. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Arnold, Roxanne (March 5, 1989). "E.W. Lyon, 84; Ex-President of Pomona College". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (November 6, 2012). "Thomas K. McCraw, Historian Who Enlivened Economics, Dies at 72". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "Gambrell, James Bruton". Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Lavietes, Stuart (April 14, 2003). "Dr. Arthur Guyton, Author and Researcher, Dies at 83". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Alumni Spotlight: Dr. Ed Hill". Ole Miss Alumni Association. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Gilpin, Kenneth N. (January 8, 1998). "Dr. Thomas Frist Sr., HCA Founder, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "William W. (Bill) Parsons". NASA. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ "University of Mississippi". National Collegiate Athletic Association. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Sports". Ole Miss Sports. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 170.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 255쪽.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 331.

- ^ "NCAA Football Championship History". National Collegiate Athletic Association. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Landry, Kennedy (September 25, 2018). "Magnolia Bowl: The history of the LSU-Ole Miss rivalry". Reveille. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Rollins, Khadrice (November 23, 2017). "Why Is Ole Miss vs. Mississippi State Called the Egg Bowl?". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Tulane Football adds Oklahoma, Ole Miss to Future Schedules". Tulane Green Wave. Tulane University. May 21, 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Ashoff, Edward (September 4, 2014). "Ole Miss, Vandy share unheralded rivalry". ESPN. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (October 14, 2011). "Faulkner and Football in Oxford, Miss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ "Baseball SEC Champions". SEC. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Ole Miss baseball advances to College World Series finals". The Clarion Ledger. June 23, 2022. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ ESPN News Services (June 26, 2022). "Ole Miss Rebels sweep Oklahoma Sooners to win first Men's College World Series title". ESPN. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Men's Tennis Record Book" (PDF). ESPN. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Freshmen win singles titles". ESPN. Associated Press. May 25, 2009. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Women's Basketball SEC Champions". SEC. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ SEC Staff. "SEC Legend Spotlight: Armintie Price Herrington, Ole Miss". SEC. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Jennifer Gillom". Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Men's Basketball SEC Champions". SEC. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Nichols, Beth Ann (May 26, 2021). "Historymakers: Ole Miss women's golf claims school's first recognized NCAA Championship". Golfweek. USA Today. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Seph. "Hotty Toddy: Understanding the Ole Miss Cheer, Its History & Significance". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Wiggs, Hayden (October 29, 2020). "Ole Miss Traditions: What Makes Us Rebels". The Ole Miss. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Staff report (September 5, 2016). "What is Hotty Toddy? Ole Miss chant, cheer also popular Rebel greeting". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c Ward, Doug (August 30, 2010). "Rebel spell: timeless tailgating tradition". ESPN. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- ^ Guizerix, Anna (September 7, 2018). "Dixie Cups: Trash Can Friday is back again". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ a b 싼싱(1999), p. 63.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 65.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 165-166쪽.

- ^ a b c d 싼싱(1999), 페이지 166.

- ^ "M Book". Office of Conflict Resolution and Student Conduct. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 184쪽.

- ^ "Associated Student Body". Associated Student Body. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "About Us". Ole Miss Band—The Pride of the South. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Our History". Ole Miss Band—The Pride of the South. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "Residence Halls". Student Housing. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Student Positions". Student Housing. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 263.

- ^ "Shuttle System". Department of Parking & Transportation. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Jackson, Wilton (February 3, 2020). "Day or night, robots navigate campus sidewalks to deliver food to Ole Miss students". The Clarion Ledger. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Jake (January 22, 2020). "Ole Miss Dining introduces new food delivery robots". The Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Edwin (July 13, 2016). "UM Restaurants Going Green". Ole Miss News. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "South Campus Recreation Center—Now Open!". Campus Recreation. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Fraternity & Sorority Life". Fraternity & Sorority Life. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 253.

- ^ "History of Fraternities". Sigma Chi Fraternity. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Two Secret Societies United—Delta Tau Delta and the Rainbow Society Join Hands" (PDF). The New York Times. March 28, 1885. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ a b 싼싱(1999), 페이지 177.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 177-178쪽.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 178.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 178-179쪽.

- ^ Sansing, David G. "Lee Maurice Russell: Fortieth Governor of Mississippi: 1920-1924". Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 204.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 334-335쪽.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 335–336.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 페이지 336.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (February 18, 2014). "F.B.I. Joins Ole Miss Inquiry After Noose Is Left on Statue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (September 17, 2015). "Man Sentenced to Six Months for Role in Placing Noose on Ole Miss Statue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Farzan, Antonia Noori (July 26, 2019). "Ole Miss frat brothers brought guns to an Emmett Till memorial. They're not the first". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 163쪽, 168쪽.

- ^ 싼싱(1999), 167-168쪽.

- ^ a b "The Daily Mississippian". Student Media Center. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "NewsWatch". Student Media Center. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Rebel Radio". Student Media Center. University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

인용작

- Barrett, Russell H. (1965). Integration at Ole Miss. Chicago: Quadrangle Books. ASIN B0007DELMI.

- Bryant, Nick (Autumn 2006). "Black Man Who Was Crazy Enough to Apply to Ole Miss". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (53): 60–71. JSTOR 25073538.

- Cabaniss, J. A. (1949). The University of Mississippi; Its First Hundred Years. University & College Press Of Mississippi. ISBN 9780878050000.

- Cohodas, Nadine (1997). The Band Played Dixie. Free Press. ISBN 9780684827216.

- Dollar, Charles M. (Spring–Summer 2015). "Florence Latimer Mars: A Courageous Voice Against Racial Injustice in Neshoba County, Mississippi (1923-2006)" (PDF). The Journal of Mississippi History. LXXVII (1 & 2): 1–24. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- Fowler, Richard (December 1941). "The University of Mississippi". BIOS. Beta Beta Beta Biological Society. 12 (4): 213–215. JSTOR 4604602. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- Heymann, C. Davis (1998). RFK: A Candid Biography of Robert F. Kennedy. Dutton Adult. ISBN 9780525942177.

- Eagles, Charles (2009). The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807832738.

- Lloyd, James B. (1980). Lives of Mississippi Writers, 1817-1967. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi.

- Pittman, Walter E. Jr. (1985). "Eugene W. Hilgard and Scientific Education in Mississippi". Earth Sciences History. 4 (1): 26–32. Bibcode:1985ESHis...4...26P. doi:10.17704/eshi.4.1.b8653w6k36620834. JSTOR 24138437. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- Roberts, Gene; Klibanoff, Hank (2006). The Race Beat. Vintage Books. ISBN 9780679735656.

- Sansing, David (1999). The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578060917.

- Scheips, Paul J. (2005). The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1945–1992 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. ISBN 9780160723612. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- Wickham, Kathleen Woodruff (Summer 2011). "Murder in Mississippi: The Unsolved Case of Agence French-Presse's Paul Guihard". Journalism History. 37 (2): 102–112. doi:10.1080/00947679.2011.12062849. S2CID 140820029.

![Bryant Hall (1911)[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/Oxford_-_Bryant_Hall.jpg/241px-Oxford_-_Bryant_Hall.jpg)

![The Sandy and John Black Pavilion (2016)[94]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Picture_of_Ole_Miss_Basketball_Court.jpg/240px-Picture_of_Ole_Miss_Basketball_Court.jpg)