노스캐롤라이나 대학교 채플힐

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | |

이전 이름 | 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 (1789-1963) |

|---|---|

| 좌우명 | 럭스 리버타스[1] (라틴어) |

영어로 된 모토 | "빛과 자유"[1] |

| 유형 | 일반의 연구 대학 |

| 설립된 | 1789년 12월 11일; 전 ([2] |

| 창시자 | 윌리엄 리처드슨 데이비 |

모기관 | 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 |

| 인증 | SACS |

학연 | |

| 기부금 | 51억 6천만 달러(2021년)[3] |

| 챈슬러 | 케빈 구스키에비치[4] |

학무원 | 8,623 (2021년 가을)[5] |

총인원 | 12,961 (2021년 가을)[5] |

| 학생들 | 31,705 (2022년 가을)[6] |

| 학부생 | 20,029 (2022년 가을)[6] |

| 대학원생 | 11,676 (2022년 가을)[6] |

| 위치 | , 노스캐롤라이나 주 , 미국 35°54'31 ″N 79°02'57 ″W / 35.90861°N 79.04917°W |

| 캠퍼스 | 소도시[8], 760 에이커 (310 ha)[7] |

| 신문 | 데일리 타르 힐 |

| 색 | 캐롤라이나 블루 앤 화이트[9] |

| 애칭 | |

스포츠 계열사 | |

| 마스코트 | 라메즈 |

| 웹사이트 | www |

| |

노스캐롤라이나 대학교 채플힐([11]UNC, UNC-Chapel Hill, 노스캐롤라이나, 채플힐 또는 간단히 캐롤라이나)은 노스캐롤라이나주 채플힐에 있는 공립 연구 대학입니다. 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 시스템의 주력입니다. 1789년에 전세를 얻은 후, 그 대학은 1795년에 처음으로 학생들을 등록하기 시작했고, 미국에서 가장 오래된 공립 대학 중 하나가 되었습니다.[12]

이 대학은 70개 이상의 학문 과정에서 학위를 제공하며 행정적으로 13개의 개별 전문 학교와 주요 단위인 예술 과학 대학으로 구분됩니다.[13] 이 대학은 "R1: 박사 대학 – 매우 높은 연구 활동"으로 분류되며, 미국 대학 협회(AAU)의 회원입니다.[14][15] 국립과학재단에 따르면, UNC는 2018년에 11억 4천만 달러를 연구 개발에 사용하여 국내 12위를 차지했습니다.[16]

캠퍼스는 760에이커(310ha)에 달하며, Morehead Planetarium과 Franklin Street에 위치한 많은 상점과 상점을 포함합니다. 학생들은 공식적으로 인정된 550개 이상의 학생 단체에 참여할 수 있습니다. UNC 채플힐은 1953년 6월 14일에 창설된 대서양 연안 회의의 헌장 회원 중 하나입니다. 그 대학의 운동팀들은 타르 힐로서 경쟁합니다.

UNC 교수진과 동문들은 9명의 노벨상 수상자, 26명의 퓰리처상 수상자,[17][18] 그리고 54명의 로도스 학자들을 포함합니다.[19][20] 이 밖에 저명한 동문으로는 미국 대통령,[21] 미국 부통령,[22] 미국 의회 의원 98명, 내각 의원 9명을 비롯해 포춘 500대 기업 CEO, 올림픽 선수, 프로 운동선수 등이 있습니다.

역사

노스캐롤라이나 대학교는 1789년 12월 11일 노스캐롤라이나 총회에 의해 전세를 얻어 1793년 10월 12일 채플힐에 대학의 초석이 놓였는데, 이는 주의 중심적인 위치 때문에 선택된 것입니다.[23][24] 이 대학은 미국에서 가장 오래된 공립 대학이라고 주장하는 세 개의 대학 중 하나이며, 18세기에 공공 기관으로서 학위를 수여하는 유일한 기관입니다.[25][26]

남북전쟁 당시 노스캐롤라이나 주지사 데이비드 라우리 스웨인(David Lowry Swain)은 제퍼슨 데이비스(Jefferson Davis) 남부연합 대통령을 설득하여 일부 학생들을 징집에서 제외시켰으며, 따라서 이 대학은 남부연합에서 겨우 개교한 몇 안 되는 대학 중 하나였습니다.[27] 그러나 채플힐은 전쟁 기간 동안 남부의 어떤 마을보다 더 많은 인구를 잃었고, 학생 수가 회복되지 않자 1870년 12월 1일부터 1875년 9월 6일까지 재건 기간 동안 문을 닫아야 했습니다.[28] 다시 문을 연 후, 등록은 더뎌졌고, 대학 행정가들은 교사들과 장관들의 아들들을 위한 무료 등록금과 출석을 감당할 수 없는 사람들을 위한 대출을 제공했습니다.[29]

남북 전쟁 이후, 그 대학은 명망 있는 학위를 가진 프로그램과 온보드 교수진을 현대화하기 시작했습니다.[30] 프란시스 베너블 UNC 총장이 1905년 "대학의 날" 기념식에서 새 체육관 건립, 새로운 화학 실험실 건립, 대학원 설립 등을 추진한 성과들입니다.[31]

프랭크 포터 그레이엄(Frank Porter Graham) 대학 총장의 초기 회의에도 불구하고 1931년 3월 27일 노스캐롤라이나 대학교를 노스캐롤라이나 대학교의 농업공학부 주립대학 및 여성대학과 함께 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 통합대학을 구성하는 법안이 통과되었습니다.[32] 1963년, 통합된 대학은 완전히 남녀공학으로 만들어졌지만, 대부분의 여성들은 여전히 첫 2년 동안 여성대학에 다녔고, 신입생들은 캠퍼스에서 생활해야 했고, 여성 거주관이 한 곳밖에 없었기 때문에 채플힐로 전학했습니다. 그 결과, 우먼 칼리지는 "그린스보로에 있는 노스캐롤라이나 대학교"로 이름이 바뀌었고, 노스캐롤라이나 대학교는 "채플 힐에 있는 노스캐롤라이나 대학교"가 되었습니다.[33][34][35] 1955년,[36] UNC는 공식적으로 학부 구분을 없앴습니다.

제2차 세계 대전 동안, UNC는 학생들에게 해군 위원회로 가는 길을 제공하는 V-12 해군 대학 훈련 프로그램에 참여한 전국적으로 131개의 대학 중 하나였습니다.[37]

1960년대 동안, 그 캠퍼스는 중대한 정치적 항의의 장소였습니다. 1964년 민권법이 통과되기 전 프랭클린 스트리트 식당에서 조용히 시작된 지역 인종 차별에 대한 시위는 대규모 시위와 소요로 이어졌습니다.[38] 시민 불안의 기후는 1963년 노스캐롤라이나 주의 주 캠퍼스에서 공산주의자들의 연설을 금지하는 의장 금지법을 촉발시켰습니다.[39] 교내 인종 차별에 대한 이러한 입장은 농성 운동으로 이어졌습니다. 노스 캐롤라이나에서 농성 운동은 공공 시설의 인종적 분리에 맞서 남부 전역의 대학들에 도전했던 새로운 시대를 시작했습니다. 이 법은 윌리엄 브랜틀리 에이콕 대학 총장과 윌리엄 프라이데이 대학 총장에 의해 즉각적인 비판을 받았지만, 1965년까지 노스캐롤라이나 총회에서 검토되지 않았습니다.[40] 특히 대학의 이사회가 마르크스주의자 허버트 압테커와 시민 자유 운동가 프랭크 윌킨슨에게 연설 초대를 허용하기로 한 폴 프레더릭 샤프 신임 총리의 결정을 기각했을 때, "자주" 방문을 허용하기 위한 작은 수정은 학생 단체를 진정시키는 데 실패했습니다. 그러나, 어쨌든 두 명의 연사가 채플힐에 왔습니다. 윌킨슨은 캠퍼스 밖에서 연설을 했고, 1,500명 이상의 학생들이 캠퍼스 가장자리에 있는 낮은 캠퍼스 벽을 가로질러 주지사 댄 K를 위해 데일리 타르 힐이 "댄 무어의 벽"이라고 명명한 애프테커의 연설을 보았습니다. 무어.[41] 폴 딕슨 학생회장이 이끄는 UNC-채플힐 학생들이 미국 연방법원에 소송을 제기했고, 1968년 2월 20일, 의장 금지법은 기각되었습니다.[42] 1969년, Lenoir Hall의 캠퍼스 푸드 노동자들은 그들의 고용에 영향을 미친 인종적인 불평등에 항의하며 파업을 벌였습니다. 대학과 채플힐 공동체의 학생 단체와 회원들의 지지를 얻고, 폭동 진압용 장비를 착용한 주 경찰들이 캠퍼스에 배치되고 주 방위군이 더럼에서 대기하도록 이끌었습니다.[43]

UNC-Chapel Hill은 1990년대 후반부터 빠르게 확장되어 2007년까지 총 학생 수가 28,000명 이상으로 15% 증가했습니다. 여기에는 "Carolina First" 기금 모금 캠페인에 의해 부분적으로 지원되는 새로운 시설의 건설과 10년 내에 20억 달러 이상으로 4배 증가한 기금이 수반됩니다.[44][45] 올리버 스미스 교수는 유전학에 대한 업적으로 2007년 노벨 의학상을 수상했습니다.[46] 또한 아지즈 산카르 교수는 DNA의 분자 복구 메커니즘을 이해한 공로로 2015년 노벨 화학상을 수상했습니다.[47]

2011년, 여러 조사 중 첫 번째 조사에서 운동 프로그램과 관련된 대학의 사기와 학업 부정이 발견되었습니다.[48] 2010년에 시작된 학사 부정과 대학의 미식 축구 프로그램에 대한 부적절한 혜택과 관련된 덜 중요한 스캔들 이후, 이 대학의 아프리카계 미국인 연구부에 의해 제공된 200개의 의문스러운 수업들이 밝혀졌습니다. 그 결과, 대학은 2015년에 인증기관으로부터 보호관찰을 받았습니다.[49][50] 2016년에 보호관찰 대상에서 제외되었습니다.[51]

같은 해 노스 캐롤라이나의 공립 대학들은 4억 1,400만 달러의 예산 삭감을 분담해야 했으며, 이 중 채플 힐 캠퍼스는 2011년에 1억 달러 이상의 손실을 입었습니다.[52] 이는 2007년 이후 2억 3,100만 달러의 대학 지출을 줄인 주정부 예산 삭감에 따른 것입니다. 브루스 카니(Bruce Carney) 프로보스트는 2009년 이후 130명 이상의 교직원이 UNC를 떠났으며,[53] 직원 유지 상태가 좋지 않았다고 말했습니다.[54] UNC-CH 이사회는 등록금을 15.6% 인상할 것을 권고했는데, 이는 역사적으로 큰 폭입니다.[53] 2011년의 예산 삭감은 대학에 큰 영향을 미쳤고 이 증가된 등록금 계획을 실행에[52] 옮겼고 UNC 학생들은 항의했습니다.[55] 2012년 2월 10일, UNC 이사회는 16개 모든 캠퍼스에 걸쳐 주 내 학부생들의 등록금과 수수료를 8.8% 인상하는 것을 승인했습니다.[56]

2018년 6월, 교육부는 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 채플힐이 4명의 학생과 행정가가 불만을 제기한 지 5년 만에 성폭행 신고를 처리하는 과정에서 타이틀 IX를 위반했다는 사실을 발견했습니다.[57][58] 이 대학은 대학 캠퍼스에서의 성폭행에 관한 2015년 다큐멘터리 헌팅 그라운드(The Hunting Ground)에도 등장했습니다.[59] 이 영화에 출연한 두 학생 애니 E. 클라크와 안드레아 피노는 생존자 옹호 단체인 엔드 레이프 온 캠퍼스를 설립하는 것을 도왔습니다.[60]

2018년 8월, 이 대학은 1913년 남부 연합의 딸들에 의해 캠퍼스에 세워졌던 남부 연합 기념물인 사일런트 샘(Silent Sam)이 무너지면서 전국적인 주목을 받게 되었습니다.[61] 이 동상은 1960년대부터 여러 곳에서 논란이 끊이지 않았으며, 비평가들은 이 기념비가 인종차별과 노예제도에 대한 기억을 불러일으킨다고 주장했습니다. 많은 비평가들은 1913년 6월 2일 동상 제막식에서 지역 사업가이자 유엔사 수탁자인 줄리안 카가 한 헌정 연설에서 지지된 명백한 인종차별적 견해와 헌정식에서 군중들이 만난 승인을 인용했습니다.[62] 2018~2019학년도 시작 직전 사일런트 샘이 시위자들에 의해 쓰러지고 파손되어 그 이후로 학교를 결석하게 되었습니다.[63] 2020년 7월, 줄리안 카의 이름을 딴 이 대학의 카 홀은 "학생 문제 빌딩"으로 이름이 바뀌었습니다.[64] 카는 백인 우월주의를 지지했고 쿠룩스 클랜도 지지했습니다.[64]

UNC-Chapel Hill은 2020년 8월 캠퍼스를 재개한 후 2020년 가을 학기 직접 수업을 시작한 지 일주일 만에 135명의 새로운 COVID-19 사례와 4개의 감염 클러스터를 보고했습니다. 8월 10일, 유엔사의 몇몇 구성 기관의 교직원들이 이사회를 상대로 항의서를 제출하면서 시스템이 가을을 맞아 온라인 전용 교육을 기본으로 해달라고 요청했습니다.[65] 8월 17일, UNC의 경영진은 이 대학이 8월 19일부터 모든 학부 수업을 온라인으로 옮길 것이라고 발표했고, 이는 다시 문을 연 후 학생들을 집으로 보내는 첫 번째 대학이 되었습니다.[66]

이 대학의 주목할 만한 지도자로는 26대 노스캐롤라이나 주지사 데이비드 라우리 스웨인 (1835–1868)과 툴레인 대학과 버지니아 대학의 총장이기도 한 에드윈 앤더슨 앨더먼 (1896–1900)이 있습니다.[67] 2019년 12월 13일, UNC 시스템 이사회는 만장일치로 케빈 구스키에비치를 제12대 총장으로 임명하기로 투표했습니다.[68]

가을 학기 둘째 주인 2023년 8월 28일 새벽, 박사과정 학생이 캠퍼스 중앙 근처 실험실 건물인 Caudill Labs에서 부교수인 Zijie Yan을 총으로 쏴 숨지게 했습니다.[69][70] 옌이 살해된 지 2주가 조금 넘은 2023년 9월 13일, 캠퍼스 근처에서 무장한 개인의 신고로 캠퍼스가 폐쇄되었습니다. 27살의 Mickel Deonte Harris는 9월 초에 폭행과 관련된 미결 영장으로 체포되었습니다; 그 영장에는 치명적인 무기로 폭행하고, 위협을 전달하고, 대중의 공포에 무장한 혐의가 포함되었습니다.[71]

캠퍼스

UNC-Chapel Hill의 캠퍼스는 약 125 에이커(51 ha)의 잔디와 30 에이커(12 ha) 이상의 관목 침대 및 기타 지상 덮개를 포함하여 약 760 에이커(310 ha)에 달합니다.[73] 1999년, UNC-Chapel Hill은 미국 조경가 협회 메달 수상자 16명 중 한 명이었고, T.A.에 의해 50개의 대학 또는 대학 "예술 작품" 중 한 명으로 확인되었습니다. 그의 책 '예술로서의 캠퍼스'에서 이득을 얻습니다.[74][75]

Old East 빌딩 (1793–1795년 [76]건설), South 빌딩 (1798–1814년 건설), Old West 빌딩 (1822–[77][78]1823년 건설)을 포함한 캠퍼스에서 가장 오래된 건물들은 북쪽으로 채플힐까지 이어지는 사각형 주위에 서 있습니다.[76] 이것은 대학 설립 운동을 하고 대학의 헌장을 요구하는 법안의 원 저자였던 Samuel Eusebius McCorkle의 이름을 따서 McCorkle Place라고 불립니다.[79][80]

두 번째 사각형인 폴크 플레이스(Polk Place)는 1920년대에 원래 캠퍼스의 남쪽에 지어졌으며 북쪽에는 사우스 빌딩(South Building)이 있으며 노스 캐롤라이나 출신이자 대학 동문인 제임스 K 총장의 이름을 따서 지어졌습니다. 폴크. 윌슨 도서관은 폴크 플레이스의 남쪽 끝에 있습니다.[81][82]

맥코클 플레이스와 폴크 플레이스는 모두 프랭크 포터 그레이엄 학생 연합, 데이비스, 하우스, 윌슨 도서관과 함께 21세기 캠퍼스의 북쪽에 있습니다. 대부분의 대학 강의실은 여러 개의 학부 거주관과 함께 이 지역에 위치해 있습니다.[83] 캠퍼스의 중간 부분은 페처 필드와 울렌 체육관과 함께 학생 레크리에이션 센터, 케넌 메모리얼 스타디움, 어윈 벨크 야외 트랙, 에디 스미스 필드 하우스, 보샤머 스타디움, 카마이클 오디토리움, 흑인 문화와 역사를 위한 소냐 헤인즈 스톤 센터, 정부 학교, 법학 대학원, 조지 와츠 힐 동문 센터, 램스 헤드 단지(식당, 주차장, 식료품점, 체육관) 및 다양한 거주지 홀.[83] 캠퍼스의 남쪽에는 남자 농구를 위한 딘 스미스 센터, 쿠리 나타토라토리움, 의과 대학, UNC 병원, 케넌-플래글러 비즈니스 스쿨, 그리고 최신 학생 거주지가 있습니다.[83]

캠퍼스 특징

맥코클 플레이스(McKorkle Place)에 위치한 데이비 포플러 나무(Davie Poplar Tree)는 이 대학의 설립자 윌리엄 리처드슨 데이비(William Richardson Davie)가 이 대학의 위치를 선택했다고 전해지는 유명한 전설이 있습니다. 다비 포플러의 전설에 따르면 나무가 서 있는 한 대학도 그렇게 될 것이라고 합니다.[85] 하지만, 이 이름은 이 대학이 설립된 지 거의 한 세기가 지난 후에야 비로소 이 나무와 연관이 지어졌습니다.[86] Davie Poplar Jr.라는 이름의 이 나무의 이식편은 원래의 나무가 번개에 맞은 후 1918년 근처에 도금되었습니다.[86] 두 번째 이식편인 Davie Poplar III는 1993년 대학의 200주년 기념 행사와 함께 심었습니다.[87][88]이 대학의 변증법 및 자선 단체의 학생 구성원들은 이 대학의 초대 총장인 조셉 콜드웰의 알려지지 않은 휴식 장소에 대한 존경심으로 맥코클 플레이스의 잔디 위를 걷지 못하게 되어 있습니다.[89]

이 대학의 상징은 베르사유 정원의 사랑의 신전을 기반으로 한 맥코클 플레이스의 남쪽 끝에 있는 작은 신고전주의 로툰다로, 학교에 물을 공급했던 원래의 우물과 같은 위치에 있습니다.[90] 그 우물은 맥코클 플레이스의 남쪽 끝, 북쪽 쿼드, 캠퍼스의 가장 오래된 두 건물인 올드 이스트와 올드 웨스트 사이에 있습니다.

역사적인 플레이메이커스 극장은 매코클 플레이스와 폴크 플레이스 사이의 카메론 애비뉴에 위치해 있습니다. 그것은 1844년에 Old East의 북쪽 정면을 개조했던 바로 그 건축가인 Alexander Jackson Davis가 디자인했습니다.[91] 1851년에 완공된 동쪽 건물은 처음에는 도서관과 무도회장 역할을 했습니다. 원래는 미국 독립 전쟁 당시 조지 워싱턴의 특별 보좌관이었고 대학의 초기 후원자였던 노스캐롤라이나 주지사 벤자민 스미스의 이름을 따서 스미스 홀이라고 지어졌습니다.[92] 1907년 이 도서관이 힐홀로 이전할 때 이 건물은 1924년 대학 연극단인 캐롤라이나 플레이메이커스에 의해 인수될 때까지 법과대학과 농화학과 사이에 이전되었습니다. 극장으로 개조되어 1925년에 Playmakers Theater로 개관했습니다. [93] 플레이메이커스 극장은 1973년에 국가 사적으로 지정되었습니다.[94]

윌슨 도서관 남쪽에 있는 모어헤드-패터슨 종탑은 모어헤드-카인 장학금의 후원자인 존 모틀리 모어헤드 3세에 의해 의뢰되었습니다.[95] 울타리와 주변 풍경은 윌리엄 C가 디자인했습니다. 코커, 식물학 교수이자 캠퍼스 수목원의 창작자. 전통적으로, 노인들은 5월 시작 며칠 전에 탑을 오를 수 있는 기회를 가집니다.[84]

환경과 지속가능성

이 대학은 모든 신축 건물이 LEED 실버 인증 요건을 충족한다는 목표를 가지고 있으며,[96] 이 대학의 노스 캐롤라이나 식물원의 알렌 교육 센터는 노스 캐롤라이나에서 최초로 LEED 플래티넘 인증을 받은 건물입니다.[97]

UNC-Chapel Hill의 열병합 발전 시설은 2008년 기준으로 캠퍼스에서 사용되는 전기와 증기의 4분의 1을 생산했습니다.[98] 2006년, 대학과 타운 오브 채플힐은 2050년까지 온실가스 배출량을 60% 줄이기로 공동으로 합의했고, 이는 미국 최초의 타운-가운 파트너십이 되었습니다.[99] 이러한 노력을 통해 대학은 지속 가능한 기부 연구소의 대학 지속 가능성 성적표 2010에서 "A-" 등급을 획득했습니다.[100]

이 대학은 2020년까지 석탄 화력 발전소를 폐쇄하겠다는 약속을 포기해 2019년 비판을 받았습니다.[101] 당초 이 대학은 2050년까지 탄소중립을 하겠다는 계획을 발표했지만 2021년에는 2040년으로 계획이 변경됐습니다.[102] 2019년 12월, 이 대학은 시에라 클럽과 생물 다양성 센터로부터 청정 공기법 위반 혐의로 고소를 당했습니다.[103]

학술

교육과정

2007년 현재 [update]UNC-Chapel Hill은 71개의 학사과정, 107개의 석사과정, 74개의 박사과정을 제공하고 있습니다.[104] 이 대학은 100개의 모든 노스캐롤라이나 주의 학생들을 입학시키고 있으며 주법에 따르면 각 신입생 학급에서 노스캐롤라이나 주 학생들의 비율이 82%[105]를 넘거나 충족해야 합니다. 학생회는 학부생 17,981명과 대학원생 및 전문가 학생 10,935명(2009년 가을 기준)으로 구성되어 있습니다.[106] 2010년[107] 현재 UNC-Chapel Hill의 학부생 인구 중 인종 및 소수민족이 30.8%를 차지하고 있으며, 유학생들의 지원은 2004년 702명에서 2009년 1,629명으로 5년 만에 두 배 이상 증가했습니다.[108] 2009년 1학년에 입학한 학생들 중 89%는 가중 4.0 척도로 4.0 이상의 평점을 받았다고 보고했습니다.[109] 2009년 UNC-Chapel Hill에서 가장 인기 있는 전공은 생물학, 경영학, 심리학, 미디어와 저널리즘 그리고 정치학이었습니다.[109] UNC-Chapel Hill은 또한 70개국에서 300개의 유학 프로그램을 제공합니다.[110]

2006년에 도입된 Making Connections 커리큘럼의 일부로 학부 수준에서 모든 학생들은 여러 가지 일반 교육 요구 사항을 충족해야 합니다.[111] 영어, 사회과학, 역사, 외국어, 수학, 자연과학 과정은 모든 학생들에게 요구되며, 그들은 폭넓은 교양 교육을 받을 수 있습니다.[112] 대학은 또한 신입생을 위한 다양한 1학년 세미나를 제공합니다.[113] 2학년 이후, 학생들은 예술 과학 대학에 진학하거나 의학, 간호학, 비즈니스, 교육, 약학, 정보 도서관 과학, 공중 보건, 또는 미디어와 저널리즘의 학교 내에서 학부 전문 학교 프로그램을 선택합니다.[114] 대학생들은 8학기 동안 공부할 수 있습니다.[115]

입학

학부

| 학부 입학통계 | |

|---|---|

| 인정률 | 16.8% ( |

| 수율 | 45.9% ( |

| 테스트 점수는 중간 50%* | |

| SAT 토탈 | 1350-1510 (FTF의 15% 중) |

| ACT 합성 | 29–33 (FTF의 60% 중) |

| |

U.S. News & World Report에 따르면 UNC-Chapel Hill의 입학 절차는 "가장 선택적"입니다.[118] UNC-Chapel Hill은 2025년 클래스(2021년 가을 등록)에 53,776건의 신청을 받아 10,347건(19.2%)을 접수했습니다. 합격자 중 4,689명이 등록하여 45.3%의 졸업률(합격자 중 대학 진학을 선택하는 비율)을 보였습니다. UNC-Chapel Hill의 신입생 유지율은 96.5%이며, 91.9%는 6년 이내에 졸업할 예정입니다.[116][119]

ACT 점수를 제출한 2021학년도 신입생 중 60%, 중간 50%의 종합 점수는 29점에서 33점 사이였습니다. SAT 점수를 제출한 신입생의 15%; 중간 50% 종합 점수는 1330-1500점이었습니다.[116] 2020-2021학년도에는 20명의 신입생이 국가유공자 장학생이었습니다.[120] 그 대학은 국내 지원자들을 위한 필요맹입니다.[121]

아너코드

이 대학은 "학생 사법 거버넌스의 도구"로 알려진 오랜 명예 코드를 가지고 있으며, 주로 학생이 운영하는 명예 시스템을 통해 학문적 혐의로 기소된 학생들의 문제를 해결하고 대학 공동체에 대한 범죄를 수행합니다.[122]

1974년 사법개혁위원회는 현재의 명예법과 그 집행 수단을 설명하는 학생 사법 통치 기구를 만들었습니다.[123] 이 기구와 사법개혁위원회의 창설은 "흑인 학생 운동에 의한 요구"(BSM)의 목록에 이어 "흑인 학생들은 현재 우리의 이익을 대변할 흑인 학생들 또는 정당하게 선출된 흑인 학생들에 의해 행해진 모든 범죄에 대한 완전한 관할권을 갖습니다. 사법재판소."[124] 대부분의 학업 및 행동 위반은 학생이 운영하는 단일 명예 제도에 의해 처리됩니다. 그 이전에 변증법과 자선단체는 남성협의회, 여성협의회, 학생협의회와 같은 다른 캠퍼스 단체들과 함께 학생들의 우려를 지지했습니다.[125]

도서관

UNC-Chapel Hill의 도서관 시스템은 캠퍼스 곳곳에 소장되어 있는 다수의 개별 도서관을 포함하고 있으며, 총 700만권 이상의 도서관을 보유하고 있습니다.[127] UNC-Chapel Hill의 NCC(North Carolina Collection)는 전국적으로 단일 주에 대한 가장 크고 포괄적인 보유 자산 모음입니다.[128] 문학적, 시각적, 인공적 자료들의 비할 데 없는 집합체는 노스캐롤라이나 역사와 문화의 4세기를 기록하고 있습니다.[129] 노스캐롤라이나 컬렉션은 남부 역사 컬렉션, 희귀 도서 컬렉션, 남부 민속 컬렉션과 함께 루이스 라운드 윌슨의 이름을 딴 윌슨 도서관에 소장되어 있습니다.[130] 이 대학은 소프트웨어, 음악, 문학, 예술, 역사, 과학, 정치 및 문화 연구를 포함한 자유롭게 이용할 수 있는 세계 최대의 정보 모음 중 하나인 ibiblio의 본거지입니다.[131][132]

피트 근처에 위치한 데이비스 도서관은 주요 도서관이자 노스 캐롤라이나에서 가장 큰 학술 시설이자 국유 건물입니다.[88] 노스캐롤라이나 자선가 월터 로얄 데이비스의 이름을 따서 1984년 2월 6일에 개장했습니다. 데이비스 도서관에서 대출된 첫 번째 책은 조지 오웰의 1984년 책입니다.[133] R.B. 하우스 학부 도서관은 피트 지역과 윌슨 도서관 사이에 위치해 있습니다. 그것은 로버트 B의 이름을 따서 지어졌습니다. 1945년부터 1957년까지 UNC의 수상이었던 하우스는 1968년에 문을 열었습니다.[134] 2001년 R.B. 하우스 학부 도서관은 건물의 가구, 장비 및 기반 시설을 현대화하는 990만 달러의 수리를 거쳤습니다.[135] 데이비스가 건설되기 전에는 윌슨 도서관이 그 대학의 주요 도서관이었지만, 현재 윌슨은 특별한 행사를 개최하고 특별한 소장품, 희귀 도서, 임시 전시품을 소장하고 있습니다.[136]

미국 남부의 기록

이 도서관은 "미국의 역사와 문화에 대한 남부의 관점을 제공하는 디지털화된 주요 자료"의 무료 공공 접근 웹사이트인 "다큐멘터리 더 아메리칸 사우스"를 감독합니다. 이 프로젝트는 1996년에 시작되었습니다.[137] 2009년 이 도서관은 다른 기관들과 협력하여 주 전체의 디지털 도서관인 노스캐롤라이나 디지털 헤리티지 센터를 출범시켰습니다.[138]

순위와 평판

| 학벌순위 | |

|---|---|

| 국가의 | |

| ARWU[139] | 20 |

| 포브스[140] | 28 |

| THE / WSJ[141] | 33 |

| U.S. 뉴스 & 월드 리포트[142] | 22 |

| 워싱턴 월간지[143] | 24 |

| 세계적인 | |

| ARWU[144] | 29 |

| QS[145] | 132= |

| 그[146] | 69 |

| U.S. 뉴스 & 월드 리포트[147] | 41 |

U.S. News & World Report는 2023년 UNC-Chapel Hill을 공립 대학 중 4위, 미국 국립 대학 중 22위로 선정했습니다.[148] 월스트리트 저널은 UNC-채플 힐을 미시간 대학교와 UCLA에 이어 3위를 차지했습니다.[149]

이 대학은 1985년 그의 책 "The Public Ivies: A Guide to Best Public Under College and Universitys to America's Best Public Universitys and Universities에서 Richard Moll에 의해 Public Ivies로 명명되었고, 이후 Howard와 Matthew Green에 의해 가이드가 되었습니다.[150][151]

이 대학은 국립 보건원의 보조금과 기금을 많이 받고 있습니다. 2020 회계연도에 이 대학은 연구를 위해 NIH 기금 5억 990만 달러를 받았습니다. 이 금액으로 채플힐은 NIH가 전국에서 10번째로 연구비를 지원받는 기관이 되었습니다.[152]

장학금

수십 년 동안 UNC-Chapel Hill은 Morehead-Cain Scholarship으로 알려진 학부생 장학금을 제공해 왔습니다. 수급자는 4년간 등록금 전액, 숙식비, 도서, 여름공부 자금 등을 지원받습니다. Morehead가 설립된 이래로, 이 프로그램의 29명의 동문들이 Rhodes Scholars로 이름을 올렸습니다.[153] 2001년부터 North Carolina는 UNC-Chapel Hill과 인근 Duke 대학교에서 수혜자들에게 전액 학생의 특권을 부여하는 공로 장학금 및 리더십 개발 프로그램인 Robertson Scholars Leadership Program을 공동 개최하고 있습니다.[154] 게다가, 이 대학은 캐롤라이나, 로빈슨 대령, 존스턴 및 포그 장학생 프로그램을 포함하여, 공로와 지도자의 자질에 따라 장학금을 제공합니다.[155]

2003년, 제임스 모서 수상은 캐롤라이나 협약을 발표했는데, 이 협약에서 UNC는 대학에 입학하는 저소득층 학생들에게 부채 없는 교육을 제공합니다. 이 프로그램은 공립 대학에서는 처음이었고, 프린스턴 대학에 이어 전국에서 두 번째로 전체적인 프로그램이었습니다. 그 이후로 약 80개의 다른 대학들이 그 뒤를 이었습니다.[156]

애슬레틱스

노스 캐롤라이나의 운동팀은 타르 힐로 알려져 있습니다. 1953-54 시즌부터 대서양 연안 컨퍼런스(ACC)에 참가하고 있으며, 전미 대학 체육 협회 디비전 I 레벨(Football Subdition; FBS)의 일원으로 참가하고 있습니다.[157] 남자 종목으로는 야구, 농구, 크로스컨트리, 펜싱, 축구, 골프, 라크로스, 축구, 수영&다이빙, 테니스, 육상, 레슬링이 있고 여자 종목으로는 농구, 크로스컨트리, 펜싱, 필드하키, 골프, 체조, 라크로스, 조정, 축구, 소프트볼, 수영, 다이빙, 테니스, 육상, 배구가 있습니다.

NCAA는 UNC-Chapel Hill을 "노스 캐롤라이나 대학"이라고 부릅니다.[10] 2011년 가을 현재, 이 대학은 6개의 다른 스포츠 종목에서 40개의 NCAA 팀 챔피언십을 우승했으며, 이는 역대 8번째입니다.[158] 여기에는 여자 축구 21개, 여자 필드 하키 6개, 남자 라크로스 4개, 남자 농구 6개, 여자 농구 1개, 남자 축구 2개의 NCAA 선수권 대회가 포함됩니다.[159] 남자 농구팀은 2017년 6번째 NCAA 농구선수권대회에서 우승했는데, 이는 로이 윌리엄스 감독이 감독으로 부임한 이후 세 번째입니다. UNC는 또한 1924년 선수권 대회에서 내셔널 챔피언 타이틀을 소급하여 부여받았지만, 일반적으로 공식 집계에는 포함되지 않습니다. 다른 최근의 성공은 남자 축구의 2011년 대학 컵과 2006년부터 2009년까지 야구팀의 4회 연속 대학 월드 시리즈 출전을 포함합니다.[160] 1994년, 이 대학의 운동 프로그램들은 NCAA 대회에서 누적 성적으로 수여되는 시어스 디렉터스 컵 "올 스포츠 전국 선수권 대회"에서 우승을 차지했습니다.[161] 노스캐롤라이나 출신의 올해의 합의된 대학 대표 선수로는 필드 하키의 레이첼 도슨, 남자 농구의 필 포드, 타일러 한스브로, 앤튼 제이미슨, 빈스 카터, 제임스 워치, 마이클 조던, 여자 축구의 미아 햄(2회), 섀넌 히긴스, 크리스틴 릴리, 티샤 벤츄리니 등이 있습니다.[162]

마스코트와 닉네임

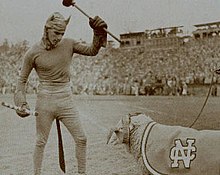

그 대학의 팀들은 타르와 피치 제작자로서 그 주의 18세기 중요성을 언급하면서 "타르 힐(Tar Hills)"이라는 별명으로 불립니다.[163] 그러나 이 별명의 문화적 관련성은 미국 남북전쟁과 미국혁명의 일화를 포함하는 복잡한 역사를 가지고 있습니다.[163] 마스코트는 Ramese라는 이름의 살아있는 Dorsetram으로, 팀 매니저가 버지니아 군사 연구소와의 연례 경기에 램을 가져갔던 1924년으로 거슬러 올라가는 전통이 있는데, 이는 전 축구 선수 Jack "The Battering Ram" Merrit의 플레이에서 영감을 받아 만들어졌습니다. 키커는 경기에서 승리한 필드골을 넣기 전 행운을 빌며 머리를 비볐고, 숫양은 그대로 있었습니다.[164] 게임에 등장하는 의인화된 숫양 마스코트도 있습니다.[165] 현대의 라메즈는 선원의 모자를 쓴 모습으로 그려져 있는데, 이것은 제2차 세계 대전 당시 이 대학에 부속된 미국 해군 비행 훈련 프로그램을 지칭하는 것입니다.[166]

캐롤라이나 웨이

농구 코치인 딘 스미스는 그의 선수들에게 "열심히 놀고, 똑똑하게 놀고, 함께 놀자"[167]라고 도전했던 "카롤리나 방식"에 대한 그의 아이디어로 널리 알려져 있습니다. "카롤리나 방식"은 코트에서 뿐만 아니라 교실에서의 탁월함에 대한 아이디어였습니다. 스캇 윌리엄스 전 선수는 스미스 코치의 저서 '캐롤라이나 웨이'에서 딘 스미스에 대해 "우승은 캐롤라이나에서 매우 중요했고, 우승에 대한 부담감이 컸지만, 코치는 우승보다 우리가 건전한 교육을 받고 좋은 시민으로 변하는 데 더 신경을 썼다"고 말했습니다.[168]

2014년 10월 22일에 발표된 웨인스타인 보고서는[169] 1993년부터 2011년까지 18년에 걸쳐 3,100명이 넘는 학생과 학생 운동선수들이 관련된 제도화된 학사 사기를 주장하며 "카롤리나 웨이" 이미지에 도전장을 던졌습니다.[170] 그 보고서는 딘 스미스 시대에 적어도 54명의 선수들이 "종이 수업"이라고 알려지게 된 것에 등록했다고 주장했습니다. 보고서는 의문의 수업이 스미스의 최종 우승 년도인 1993년 봄에 시작되었기 때문에 챔피언 경기가 끝난 후에야 그 성적이 입력되었을 것이라고 언급했습니다.[171] 웨인스타인 보고서의 주장에 대해 NCAA는 자체 조사를 시작했고 6월 5일, 2015년[172] NCAA는 "비윤리적인 행동과 협력하지 못한 두 가지 사례"와 "학생 운동선수들의 논문 과정에 대한 접근과 도움과 관련된 비윤리적인 행동과 추가적인 이익", 허용할 수 없는 학문을 제공한 강사/상담자의 비윤리적인 행동을 포함한 다섯 가지 주요 위반 사항으로 기관을 고발했습니다. 학생-athletes에 대한 지원; 그리고 모니터링의 실패와 제도적 통제의 결여." 2017년 10월, NCAA는 조사 결과를 발표하고 "이 사건의 유일한 위반은 부서 의장과 비서의 협조 실패"라고 결론 내렸습니다.[173]

라이벌리

노스 캐롤라이나와 첫 번째 상대인 버지니아 대학교 사이의 남부에서 가장 오래된 경쟁 관계는 20세기 전반의 3분의 1 동안 두드러졌습니다.[174] 2014년 10월 동부 명문 공립대학 두 곳의 축구계 119번째 만남이 있었습니다.[175]

가장 치열한 경쟁 중 하나는 더럼의 듀크 대학교입니다. 서로 겨우 8마일 떨어진 곳에 위치한 이 학교들은 정기적으로 육상과 학업 모두에서 경쟁합니다. 하지만 캐롤라이나와 듀크의 라이벌전은 농구에서 가장 치열합니다.[176] 남자 농구에서 총 11번의 전국 선수권 대회를 가진 두 팀은 지난 30년 동안 전국 선수권 대회에서 자주 경쟁해 왔습니다. 이 경쟁 관계는 윌 블라이스의 '이런 식으로 영원히 행복해질 수 없다'를 포함한 여러 책의 초점이 되었으며, HBO 다큐멘터리 '담배 길을 위한 전투'의 초점이 되었습니다. 듀크 대 캐롤라이나.[177]

캐롤라이나는 노스 캐롤라이나 주립 대학의 Tobacco Road 학교와 주 내 경쟁 관계를 유지하고 있습니다. 그러나 1970년대 중반부터 NC 주의 농구 프로그램이 심각하게 쇠퇴하고(그리고 듀크의 농구 프로그램이 부활한 것), 이는 4승 36패를 기록한 로이 윌리엄스의 재임 기간 동안 바닥에 도달한 이후, 타르 힐스에 대한 관심을 듀크로 옮겼습니다. Tar Hel 지지자들이 NC State를 라이벌로 인정한 지 수십 년이 지났음에도 불구하고 Wolfpack 신도들은 여전히 그 주에서 라이벌 관계를 가장 씁쓸하게 생각하고 있습니다. 두 학교를 합치면, 농구에서는 8개의 NCAA 선수권 대회와 27개의 ACC 선수권 대회가 열립니다. 각 학교 학생들은 농구와 축구 경기 전에 자주 장난을 주고받습니다.[178][179]

러싱 프랭클린

학생들은 이전에 스포츠 행사 전에 프랭클린 거리에서 "비트 듀크" 퍼레이드를 열었지만,[180] 오늘날 학생들과 스포츠 팬들은 캐롤라이나의 스포츠 팀 중 한 팀의 우승으로 술집과 거주지 홀에서 쏟아져 나오는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[181] 비록 다른 프랭클린 거리의 기념식들은 여자 농구팀과 여자 축구팀의 승리에서 비롯되었지만,[182][183] 대부분의 경우 프랭클린 거리의 "본파이어" 기념식은 남자 농구팀의 승리 때문입니다. 프랭클린 거리에서 처음으로 알려진 학생 축하 행사는 1957년 남자 농구팀이 캔자스 제이호크스를 상대로 전국 챔피언십 우승으로 완벽한 시즌을 마친 후에 이루어졌습니다.[184] 그때부터 학생들은 중요한 승리 후에 거리에 넘쳐났습니다.[184] 1981년 파이널 포에서 우승하고 1982년 NCAA 챔피언십에서 남자 농구팀이 우승한 후, 프랭클린 거리는 급히 거리를 달려온 팬들에 의해 파란색으로 칠해졌습니다.[184] 이 행사로 인해 지역 판매업체들은 캐롤라이나 블루 페인트를 전국 선수권 대회 근처의 타르 힐로 판매하는 것을 중단하게 되었습니다.

학교색

19세기 후반 UNC에서 대학 간 운동이 시작된 이래로, 학교의 색깔은 파란색과 흰색이었습니다.[185] 이 색깔들은 이 대학에서 가장 오래된 학생 단체인 변증법 (파란색)과 자선 (흰색) 협회에 의해 몇 년 전에 선택되었습니다. 학교는 클럽 중 하나에 참여를 요구했고, 전통적으로 디족은 노스캐롤라이나 서부 출신이었고, 파이족은 동부 출신이었습니다.[186]

사회 구성원들은 대학 행사에서 파란색 또는 흰색 리본을 착용하고 졸업식 때 졸업장에 파란색 또는 흰색 리본을 달았습니다.[186] 공식적인 행사에서 두 그룹은 동등하게 대표되었고, 결국 두 색상은 대학의 일부로서 두 그룹의 통합을 나타내기 위해 행렬 지도자들에 의해 사용되었습니다.[187] 1880년대에 축구가 인기 있는 대학 스포츠가 되었을 때, 캐롤라이나 축구팀은 디파이 협회의 밝은 파란색과 흰색을 학교 색상으로 채택했습니다.[188]

교가

졸업식, 소집식, 운동 경기 등 다양한 행사에서 흔히 연주되고 부르는 여러 노래 중 주목할 만한 것은 대학 싸움 노래인 "I'm a Tar Hel Born"과 "Here Comes Carolina"입니다.[189] 싸움 노래들은 종종 주요한 승리 후 뿐만 아니라 캠퍼스의 중심 근처에 있는 종탑에 의해 연주됩니다.[189] "I'm a Tar Heel Born"은 1920년대 후반 이 학교의 모교인 "Hark The Sound"의 태그로 시작되었습니다.[189]

학생생활

| 인종과 민족[190] | 총 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 하얀색 | 57% | ||

| 아시아의 | 12% | ||

| 히스패닉계 | 9% | ||

| 블랙입니다. | 8% | ||

| 기타[a] | 8% | ||

| 외국 국적 | 4% | ||

| 경제적 다양성 | |||

| 저소득층[b] | 22% | ||

| 부유한[c] | 78% | ||

조직 및 활동

UNC-Chapel Hill의 대부분의 학생 단체들은 공식적으로 인정을 받고 있으며 대학의 행정 단위인 캐롤라이나 연합의 도움을 받고 있습니다.[193] 자금은 학부 상원(UGS) 또는 대학원 및 전문 학생 정부 상원(GPSG 상원)의 재량에 따라 할당되는 학생 정부 학생 활동비에서 파생됩니다.[194]

가장 큰 학생 모금 행사인 UNC 댄스 마라톤은 수천 명의 학생, 교직원 및 지역 사회 구성원이 노스 캐롤라이나 어린이 병원을 위한 기금을 모금하는 데 참여합니다. 이 단체는 연중 모금과 봉사 활동을 펼치고 있으며, 1999년 설립 이후 2008년[update] 현재 140만 달러를 기부했습니다.[195]

학생들이 운영하는 신문 데일리 타르 힐(The Daily Tar Hel)은 2004-5년 미국 대학 출판부(Associated College Press)로부터 전국 페이스메이커 상(National Pacemaker Award)을 받았습니다.[196] 1977년 설립된 WXYC 89.3 FM은 UNC-Chapel Hill의 학생 라디오 방송국으로 365일 24시간 방송합니다. 프로그래밍은 학생 DJ에게 달려 있습니다. WXYC는 일반적으로 다양한 장르와 시대의 음악을 거의 재생하지 않습니다. 1994년 11월 7일, WXYC는 인터넷을 통해 신호를 방송하는 세계 최초의 라디오 방송국이 되었습니다.[197][198] 학생들이 운영하는 텔레비전 방송국인 STV는 캠퍼스 케이블과 채플힐 스펙트럼 시스템을 통해 방송됩니다.[199] 대학원생들이 편집한 캐롤라이나 계간지는 1948년 캐롤라이나 잡지의 후계자로 창간돼 [200]웬델 베리, 레이먼드 카버, 돈 델릴로, 애니 딜러드, 조이스 캐롤 오츠, 존 에드가 와이드먼 등 수많은 작가들의 작품을 출간했습니다. 계간지에 등장하는 작품들은 최고의 미국 단편 소설과 남부의[201] 새로운 이야기에 수록되어 있으며, 푸쉬카트와 O를 수상했습니다. 헨리 프라이즈.[202]

클레프 행거(Clef Hangers)는 1977년 배리 손더스(Barry Saunders)가 설립한 이 대학에서 가장 오래된 아카펠라 그룹입니다.[203][204] 이 그룹은 이후 2003년 브리즈 앨범에 수록된 '이지(Easy)'라는 곡으로 최고의 솔로 가수상을 포함하여 여러 개의 컨템포러리 아카펠라 레코딩 어워드(CARA)를 수상했습니다. 그들은 '타임아웃의 나의 사랑'(2008)[205]과 '트위스트'(2009)에서 'Ain't Nothing Wrong on Twist'(2009)으로 최우수 남자 대학 노래상을 두 개 더 수상했습니다.[206] 2002년에 졸업한 브렌던 제임스와 [207]2008년에 졸업한 아눕 데사이가 멤버로 포함되어 있습니다.[204]

학교에서 세 번째로 큰 학생 운영 단체인 레지던스 홀 협회는 레지던스 홀에 거주하는 학생들을 위한 대표적인 단체입니다. 그 활동은 주민들을 위한 사회, 교육 및 자선 프로그램, 우수한 주민들과 구성원들을 인정하고 주민들이 성공적인 지도자로 성장할 수 있도록 돕는 것을 포함합니다.[208] RHA는 전국 대학 및 대학 레지던스 홀 협회에 소속되어 있습니다.[209]

이 대학의 운동팀들은 이 대학의 마칭 밴드인 마칭 타르 힐스(The Marching Tar Hills)의 지원을 받고 있습니다. 275명으로 구성된 자원봉사 밴드는 모든 홈 축구 경기에 참여하고, 소규모의 응원 밴드는 모든 홈 농구 경기에서 경기를 합니다. 밴드의 각 멤버는 또한 26개의 다른 스포츠 경기에서 경기하는 5개의 펩 밴드 중 적어도 하나에서 경기해야 합니다.[211]

UNC-Chapel Hill에는 지역 극단인 Playmakers Repertory Company가 상주하며 캠퍼스 [212]내에서 정기적인 무용, 드라마, 음악 공연을 개최합니다.[213] 이 학교에는 결혼식과 드라마 제작에 사용되는 숲 극장으로 알려진 야외 석조 원형 극장이 있습니다.[214] 포레스트 극장은 캐롤라이나 연극 제작자들의 창시자이자 미국의 민속극의 아버지인 프레드릭 코흐 교수에게 바쳐졌습니다.[215]

캠퍼스의 많은 친목회와 여대생들은 국가 범그리스 회의, 국제친애협의회, 그리스 동맹협의회, 국가 범그리스 협의회에 속해 있습니다. 2010년 봄 현재, 18퍼센트의 학부생들이 친목회나 여대생 모임에 있었습니다(전체 17,160명 중 3131명).[216] 2010학년도 봄학기 동아리 및 여대생의 총 사회봉사시간은 51,819시간(1인당 평균 31시간)이었습니다. UNC-Chapel Hill은 또한 집은 없지만 학교에서 인정하는 전문적이고 봉사적인 친목회를 제공합니다. 캠퍼스의 명예 단체 중 일부는 다음과 같습니다: 황금 양털 훈장, 성배 훈장, 구 우물 훈장, 종탑 훈장, 프랭크 포터 그레이엄 아너 소사이어티.[217]

학생정부

UNC-Chapel Hill의 학생 정부는 학부생 정부와 대학원생 및 전문 학생 정부로 구분됩니다.[218] 학부생 정부는 학생회장을[219] 위원장으로 하는 집행부와 학부생 상원인 입법부로 구성됩니다.[220] 대학원 및 전문 학생 정부도 마찬가지로 행정부(자체 대통령이 있는)와 입법 상원으로 구성됩니다.[221] 학부생과 대학원생, 전문대학원생 모두에게 영향을 미치는 법안을 승인하고 학부생과 대학원생, 전문대학원생 정부에 자문하는 공동 거버넌스 협의회도 있습니다.[222] 명예제도 마찬가지로 학부생과 대학원생, 전문대학원생을 포함하는 두 개의 분과로 나누어져 있습니다.[223] 사법부의 다른 부분인 학생 대법원은 4명의 대법관과 대법원장으로 구성되며, 이들은 학생회장이 임명하고 학생회의 3분의 2 찬성으로 확정됩니다.[224]

식사

레누아르 다이닝 홀은 1939년에 뉴딜 공공사업청의 자금을 사용하여 완공되었으며, 1940년 1월 크리스마스 휴일에서 돌아온 학생들에게 서비스를 제공하기 위해 문을 열었습니다. 이 건물의 이름은 1790년 이 대학의 초대 이사회 의장이었던 윌리엄 레누아르 장군의 이름을 따서 지어졌습니다. 창립 이래로 Lenoir Dining Hall은 Carolina Dining Services의 주력이자 캠퍼스 내 다이닝의 중심지로 남아 있습니다. 1984년과 2011년 두 차례에 걸쳐 좌석을 개선하고 식사 시간을 단축하기 위해 새 단장을 했습니다.[225]

체이스 홀은 원래 사우스 캠퍼스의 식사 옵션을 제공하고 1919년부터 1930년까지 재직했던 전 유엔사 총재 해리 우드번 체이스를 기리기 위해 1965년에 지어졌습니다. 2005년, 이 건물은 학생 및 학술 서비스 건물의 자리를 마련하기 위해 철거되었고, 원래 위치의 북쪽에 람스 헤드 센터(공식적으로 체이스 다이닝 홀이라는 내부 식당)로 재건되었습니다. 학생들이 식당의 이름을 램스 헤드(Rams Head)로 잘못 지었기 때문에 대학은 2017년 3월 체이스 홀(Chase Hall)을 건물 이름으로 공식 복원했습니다. 체이스 다이닝 홀, 램스 헤드 마켓, "블루 존"이라고 불리는 회의실이 있습니다.[226] 체이스 다이닝 홀은 1,300명을 수용할 수 있으며, 하루에 1만 끼를 제공할 수 있습니다.[227] 사우스 캠퍼스에 거주하는 학생들에게 더 많은 음식 서비스 옵션을 지속적으로 제공하고 있으며, "심야"라고 불리는 9시부터 12시까지의 시간을 포함하여 연장된 시간을 특징으로 합니다.[228]

주택

캠퍼스 내에서 주거 및 주거 교육부는 13개의 커뮤니티로 분류된 32개의 레지던스 홀을 관리합니다. 이러한 커뮤니티는 대학에서 가장 오래된 건물인 Olde Campus Upper Quad Community부터 2002년에 완공된 Manning West와 같은 현대 커뮤니티까지 다양합니다.[229][230] 1학년 학생들은 대부분 사우스 캠퍼스에 위치한 8개의 "1학년 체험" 거주관 중 한 곳에 거주해야 합니다.[231] 이 대학은 레지던스 홀 외에도 람 빌리지, 오둠 빌리지, 베이티 힐 학생 가족 주택 등 3개 커뮤니티로 구성된 8개 아파트 단지를 추가로 관리하고 있습니다. 외국어와 물질 없는 생활에 중점을 둔 테마형 주택과 함께 특정 사회적, 성별 관련 또는 학문적 요구를 위해 형성된 "생활 학습 공동체"도 있습니다.[232] 인류학과의 후원을 받는 UNITAS가 그 예인데, 그곳에서 거주자들은 유사성보다는 문화적 또는 인종적 차이를 기준으로 룸메이트를 배정받습니다.[233] 세 개의 아파트 단지는 가족, 대학원생 및 일부 상류층을 위한 주택을 제공합니다.[234] 나머지 캠퍼스와 함께 모든 레지던스 홀, 아파트 및 주변 부지는 금연입니다.[235] 2008년[update] 현재 전체 학부생의 46%가 대학이 제공하는 주택에 살고 있습니다.[236]

동문

30만 명이 넘는 전직 학생들이 살고 있는 [237]노스 캐롤라이나는 미국에서 가장 크고 활동적인 동문 그룹 중 하나입니다. 많은 타르 힐은 지역, 국내 및 국제적인 명성을 얻었습니다. 정치권에서는 제임스 K가 포함되어 있습니다. 1845년부터 1849년까지 미국의 11대 대통령을 지낸 폴크와 윌리엄 R.[238] 미국의 13대 부통령 킹.[239] Tar Hills는 Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River, Andy Griffith Show의 스타 Andy Griffith와 같은 작품의 작가 Thomas Wolfe와 같은 인물들로 대중 문화에도 한 획을 그었습니다.[240] 스포츠 스타들은 UNC에 다닐 때 딘 스미스 밑에서 뛰었던 농구선수 마이클 조던과 올림픽 선수인 에이프릴[241] 하인리히와 비카스 고우다를 포함했습니다.[241] 비즈니스 분야에서는 Hulu의 전 CEO인 Jason Kilar와 [242]Howard R이 동문입니다. 패밀리 달러의 전 CEO이자 회장인 레빈.[243]

-

마이클 조던(왼쪽)

참고 항목

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ a b Thelin, John R. (2004). A History of American Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press. p. 448. ISBN 0-8018-7855-1. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Battle, Kemp P. (1907). History of the University of North Carolina: From its beginning until the death of President Swain, 1789–1868. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. p. 6. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ 2022년 2월 18일 기준.

- ^ "Office of the Chancellor". Office of the Chancellor – UNC Chapel Hill. February 6, 2019. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ a b "Analytic Reports OIRA". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. 2021. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Carolina by the Numbers". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill OIRA. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Quick Facts". UNC News Services. 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "College Navigator – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill". National Center for Education Statistics. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ "Color Palette". Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "North Carolina". NCAA Schools. NCAA.com: The Official Web Site of the NCAA. 2008. Archived from the original on December 28, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Wootson, Cleve R. Jr (January 8, 2002). "UNC Leaders Want Abbreviation Change". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ "220 Years of History – UNC System Office". Northcarolina.edu. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Schools". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Center for Postsecondary Education. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "AAU Member Universities" (PDF). www.aau.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "UNC Hussman alumni part of Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post work on U.S. Capitol assault". Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ "UNC PhD Jefferson Cowie wins 2023 Pulitzer Prize". May 2023. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ "Carolina's Rhodes Scholars". Carolina Alumni Review. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ "Alumnus Kimathi Muiruri becomes Carolina's 54th Rhodes Scholar". November 2, 2021. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ Bergeron, Paul H. "James K. Polk (1795–1849)". North Carolina History Project. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: William Rufus King, 13th Vice President (1853)". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992). Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. pp. 13, 16, 20. ISBN 0-8078-2023-7. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Assembly, North Carolina General. "Act Establishing the University of North Carolina, 1789: Electronic Edition". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ 스나이더, 윌리엄 D. (1992), 페이지 29, 35.

- ^ "C. Dixon Spangler Jr. named Overseers president for 2003–04". Harvard University Gazette. Cambridge, MA. May 29, 2003. Archived from the original on June 21, 2003. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), p. 67.

- ^ Battle, Kemp P. (1912). History of the University of North Carolina: From 1868–1912. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. pp. 39, 41, 88. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Holden, Charles (February 2018). "Manliness and the Culture of Self-Improvement: The University of North Carolina in the 1890s–1900s". History of Education Quarterly. 58 (1): 122–151. doi:10.1017/heq.2017.51. ISSN 0018-2680. S2CID 149411373. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, L.R. (1957). The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ "University Day: An Appropriate Celebration—Dr. Venable Reports the University in a Flourishing Condition—a thoughtful address by Col. Bingham". The Daily Tar Heel. October 19, 1905. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via DigitalNC.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 212–213.

- ^ "UNC Trustees in broad changes of all branches". The Daily Times-News. Burlington, NC. January 25, 1963. p. 1.

- ^ Frost, Susan H.; Hearn, James C.; Marine, Ginger M. (1997). "State Policy and the Public Research University: A Case Study of Manifest and Latent Tensions". The Journal of Higher Education. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press. 68 (4): 363–397. doi:10.2307/2960008. JSTOR 2960008.

- ^ "The History of UNCG". The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. 2005. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "North Carolina Collection-UNC Desegregation". Lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "The Beginning of NROTC at UNC Chapel Hill". Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2011. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), p. 269.

- ^ 스나이더, 윌리엄 D. (1992), 페이지 270.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 272–273.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 274–275.

- ^ Snider, William D. (1992), pp. 267–268.

- ^ "UNC Food Workers' Strike of 1969". Food and American Studies. UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "University Endowment". UNC Office of University Development. 2007. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "Historical Trends, 1978–2007". UNC Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. 2007. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, Kate (October 9, 2007). "UNC professor wins Nobel Prize". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2015 – Press Release". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "UNC Scandal". www.cbssports.com. June 4, 2014. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ New, Jake (June 12, 2015). "Accrediting Body Places UNC on Probation". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Jaleesa (June 11, 2015). "University of North Carolina placed on probation by accreditation agency". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Stancill, Jane (June 17, 2016). "UNC removed from probation by accrediting agency". Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Herald-Sun-UNC Taking Biggest Hit of System Cuts". The Herald-Sun-Trusted&Essential. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Trustees OK Major Tuition Increase at UNC-CH::WRAL.com". WRAL.com. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Will, Madeline (September 14, 2011). "UNC system faculty rates suffer due to decrease in funds". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Hartness, Erin (November 16, 2011). "UNC-CH Students Protest Tuition Increase Plan". WRAL.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Stancill, Jane (February 10, 2012). "Tuition increases at UNC schools approved amid protests". News Observer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "UNC Violated Title IX in Handling of Sexual-Misconduct Complaints". The Daily Beast. June 26, 2018. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Investigation: UNC violated Title IX in handling of sexual violence cases". ABC11 Raleigh-Durham. June 26, 2018. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ Rosenberg, Alyssa (March 13, 2015). "'The Hunting Ground' and the Challenge of Campus Rape". Washington Post.

- ^ Johnson, Rebecca (October 9, 2014). "Campus Sexual Assault: Annie E. Clark and Andrea Pino Are Fighting Back—And Shaping the National Debate". Vogue. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Silent Sam". Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Green, Hilary N. "Transcription: Julian Carr's Speech at the Dedication of Silent Sam". people.ua.edu. University of Alabama. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "U. of North Carolina under fire for $2.5M to Confederate group in 'Silent Sam' deal". NBC News. December 18, 2019. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Murphy, Kate (July 29, 2020). "These UNC dorms and academic buildings are no longer named after white supremacists". News & Observer. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ 올스턴 대 노스캐롤라이나 대학 시스템. 20번 CvS. 웨이크 군의 상급 법원입니다. 2020년 8월 20일. [1]2020년 8월 17일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨

- ^ Wong, Wilson. "UNC-Chapel Hill goes to remote learning after 135 COVID-19 cases within week of starting classes". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Previous Presidents and Chancellors". UNC Office of the Chancellor. 2008. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Kevin M. Guskiewicz begins term as 12th chancellor with investment in community UNC-Chapel Hill". December 13, 2019. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ Hudson, Susan (August 29, 2023). "Latest updates: Campus grieves after shooting at Caudill Labs". Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ "A Message from Chancellor Guskiewicz: The loss of our fellow Tar Heel". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Hammond, Colleen; Dean, Korie; Grubb, Tammy; Sánchez-Guerra, Aaron (September 13, 2023). "UNC rattled by 2nd campus lockdown in 16 days. Suspect who 'brandished' gun arrested". The News & Observer. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ "Morehead Planetarium and Science Center :: Morehead History: Part 2 – Construction". Moreheadplanetarium.org. May 10, 1949. Archived from the original on September 30, 2003. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Grounds Services". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Ellertson, Shari L. (2001). "Expenditures on O&M at America's Most Beautiful Campuses". Facilities Manager Magazine. Alexandria, VA: APPA. 17 (5). Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Gaines, Thomas A. (1991). The Campus as a Work of Art. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. p. 155. ISBN 0-275-93967-7.

- ^ a b "Old East". UNC–Chapel Hill University Library. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "South Building". UNC–Chapel Hill University Library. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Old West". UNC–Chapel Hill University Library. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "McCorkle Place". UNC-Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Powell, William S. (1991). "Samuel Eusebius McCorkle". Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Vol. 4. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1918-0.

- ^ "Biography of James Polk". whitehouse.gov. 2001. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2008 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Polk Place". The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Campus Map" (PDF). UNC Engineering Information Services. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ a b "Belltower Tour Stop". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on December 23, 2001. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ Loewer, H. Peter (2004). Jefferson's Garden. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 228. ISBN 0-8117-0076-3.

- ^ a b "McCorkle Place". UNC-Chapel Hill Graduate School. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Davie Poplar". A Self-Guided Tour of Campus. UNC Visitors' Center. 2001. Archived from the original on December 23, 2001. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Valle, Kirsten (October 12, 2004). "Reflections of a storied past". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 5, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Architectural Highlights of Carolina's Historic Campus". The Carolina Story. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Playmakers Theater Tour Stop". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 12, 2002. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "The Carolina Story—Carolina's Early Benefactors". Museum.unc.edu. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from UNC's Built Landscape". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ "UNC.edu". Archived from the original on October 3, 1999.

- ^ "UNC Sustainability: High Performance Buildings". UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Allen Education Center". North Caroline Botanic Garden. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "UNC Sustainability: Energy at UNC". UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "UNC Sustainability: Institutionalizing Sustainability". UNC-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Overall College Sustainability Leaders". The College Sustainability Report Card. Sustainable Endowments Institute. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Community frustrated with UNC's renewal of its coal plant over sustainable alternatives". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Pequeño, Sara (May 12, 2021). "UNC-Chapel Hill Stalls on Stopping Coal Use as the Climate Crisis Inches Closer to Catastrophe". INDY Week. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Pequeño, Sara (December 4, 2019). "UNC-Chapel Hill Just Got Slapped With Another Lawsuit, This Time About Its Coal Plant". INDY Week. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "Compendium of Key Facts". UNC News Services. 2007. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "Introduction to UNC: Campus and Student Profile". Teaching at Carolina. UNC Center for Teaching and Learning. 2001. Archived from the original on August 27, 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "Fall 2011 Headcount Enrollment – Office of Institutional Research and Assessment". Oira.unc.edu. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Fall 2011 Undergraduate Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity – Office of Institutional Research and Assessment". Oira.unc.edu. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Diversity at Carolina". Admissions.unc.edu. January 27, 2012. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ a b "Quick Facts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Study Abroad at UNC". Studyabroad.unc.edu. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Academic Advising Program". UNC Academic Advising Program. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Academic Policies". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "FYS @ UNC-CH: About FYS". Archived from the original on February 24, 2004. Retrieved February 24, 2004.

- ^ "When do I choose my major?". Studying FAQs. UNC Office of Undergraduate Admissions. 2005. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". UNC Academic Advising program. 2010. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c "UNC-Chapel Hill Common Data Set 2022–2023" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Common Data Set 2015–2016" (PDF). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ "University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "UNC Admissions". UNC Office of Undergraduate Admissions. UNC. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "National Merit Scholarship Corporation 2019-20 Annual Report" (PDF). National Merit Scholarship Corporation. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill -". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ "The Honor Code". Honor Court of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on May 18, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "A Question of Honor: Honor Code Timeline". The Daily Tar Heel. September 24, 2003. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ 1968년 12월 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 채플힐 레코드 #40400, 대학 기록 보관소, 윌슨 도서관, 노스캐롤라이나 대학교 채플힐의 흑인 학생 운동 요구

- ^ Coates, Albert; Hall Coates, Gladys (1985). The Story of Student Government in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill, NC: Professor Emeritus Fund. p. 332.

- ^ 2010년 8월 27일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 UNC 라이브러리 UNC Chapel Hill Libraries에 대하여. Lib.unc.edu . 2013년 8월 9일 회수.

- ^ "The Nation's Largest Libraries: A Listing By Volumes Held American Library Association". July 7, 2006. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ "The North Carolina Collection Research Library". UNC University Libraries. 2007. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "North Carolina Collection". Lib.unc.edu. July 3, 2012. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Louis Round Wilson Library: An Enduring Monument to Learning". Lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on February 4, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "ibiblio: Ten Years in the Making". ibiblio. 2002. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Carrigan, Robert; Milton, Ron; Morrow, Dan (2005). "Education and Academia: ibiblio" (PDF). Computerworld Honors Case Study. Computerworld Honors Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Happy Anniversary, Davis Library!". Lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on November 6, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Robert B. House (1892-1987) and House Library". The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "R.B. House Undergraduate Library-History and Mission". Lib.unc.edu. August 9, 2010. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Overview of the UNC Chapel Hill Library System". UNC University Libraries. 2007. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "About Documenting the American South". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hil. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ "About DigitalNC". Digitalnc.org. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2023". Forbes. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2022". The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "2022 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2024: Top global universities". Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ "2022-23 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "US News Best Universities 2022". Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Fleming (September 4, 2019). "The Top Public Schools in the WSJ/THE College Rankings". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Moll, Richard (1985). The Public Ivies: A Guide to America's Best Public Undergraduate Colleges and Universities. New York, NY: Viking. ISBN 0-670-58205-0.

- ^ Greene, Howard; Greene, Matthew W. (2000). The Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence. New York, NY: Cliff Street Books. ISBN 0-06-095362-4.

- ^ "NIH Awards". October 13, 2020. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Paul Shorkey '11 and Laurence Deschamps-Laporte '11 Named Rhodes Scholars". Morehead–Cain Foundation. 2010. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ^ "About Us". The Robertson Scholars Leadership Program. 2013. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Merit-Based Scholarships". UNC Office of Scholarships and Student Aid. 2008. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Marklein, Mary Beth (September 26, 2006). "Right to an education bound in a Covenant". USA Today. McLean, VA. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ "About the ACC". The Atlantic Coast Conference. 2004. Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Championships Administration Forms". NCAA. Archived from the original on March 16, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Schools with the Most NCAA Championships". National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2007. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Year By Year Standings". NCAA Men's College World Series. CWS Omaha, Inc. 2008. Archived from the original on March 22, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ "1993–94 Sears Directors' Cup Final Standings" (PDF). National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics. 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Carolina's National Athletes of the Year". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2008. Archived from the original on October 28, 2006. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Powell, William, S. (1982). "What's in a Name? Why We're All Called Tar Heels". UNC General Alumni Association. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ "The Ram as Mascot". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2006. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "UNC Mascot "Rameses" Killed". Raleigh, NC: WRAL. February 25, 1996. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "History of NROTC at the University of North Carolina". UNC Naval ROTC Alumni Association. 2008. Archived from the original on February 18, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "The Carolina Way: Leadership Lessons from a Life in Coaching". Barnes & Noble. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ "10 Leadership Lessons from Coach Dean Smith". Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ Saacks, Bradley. "Wainstein report reveals extent of academic scandal at UNC". Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "North Carolina and the erosion of the Carolina Way". ESPN.com. October 30, 2013. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Sara Ganim and Devon Sayers (October 22, 2014). "UNC athletics report finds 18 years of academic fraud - CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ "University of North Carolina slapped with 5 NCAA violations over academic scandal". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 28, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ a b "NCAA University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Infractions Decision" (PDF). NCAA. October 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Most-Played Rivalries". Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ U.S. News & World Report는 UC 버클리, UVA, UCLA, 미시간, 그리고 UNC-Chapel Hill을 2014년 기준으로 적어도 9년 연속 미국의 5대 공립 대학으로 선정했습니다.

- ^ Deitsch, Richard (June 23, 2008). "HBO probes Carolina-Duke rivalry". Media Circus. SI.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ "HBO.com". Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Kyle, Blakely (November 16, 2006). "Ram Roast deters Tar Heel blue tunnel". Technicianonline.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Tovar, Sergio (February 21, 2008). "Campus awakes to a red Old Well". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Greene, Caitlyn (September 24, 2008). "30 years at Sutton's". The Daily Tar Heel. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "The scene from Franklin Street (February 12, 2009)". Archived from the original on February 13, 2009.

- ^ "News and Observer: Bonfires mark Tar Heels' win (March 5, 2007)". Archived from the original on December 7, 2008.

- ^ "News and Observer: Radical changes for Chapel Hill celebrations". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c Magill, Samuel (March 17, 2008). "Basketball flavors Franklin Street celebrations". chapelhillnews.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ Sumner, Jim L. (1990). A History of Sports in North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: Division of Archives and History, NC Department of Cultural Resources. p. 35. ISBN 0-86526-241-1.

- ^ a b "Culture Corner: Di-Phi: The Oldest Organization" (PDF). March 2006. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Coates, Alfred; Coates, Gladys Hall (1985). The Story of Student Government in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill. ASIN B00070WQNC.

- ^ "School Colors". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2008. Archived from the original on May 12, 2006. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c "UNC School Songs". North Carolina Tar Heels Official Athletic Site. UNC Athletic Department. 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill". United States Department of Education. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on June 9, 2002. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Forest Theater Tour Stop". Unc.edu. Archived from the original on January 12, 2002. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "About the Carolina Union". Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Finance: At Its Core UNC's Senate – Legislative Branch – USG". Undergraduate Senate – Student Government. UNC Student Government. 2022. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ "Dance Marathon is Friday at UNC-Chapel Hill". The News & Observer. Raleigh, NC. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "Newspaper Pacemaker Winners". Associated Collegiate Press. 2005. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Grossman, Wendy (January 26, 1995). "Communications: Picture the scene". The Guardian. Manchester, United Kingdom. p. 4.

- ^ "WXYC announces the first 24-hour real-time world-wide Internet radio simulcast" (Press release). WXYC 89.3 FM. November 7, 1994. Archived from the original on December 20, 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "About STV". UNC Student Television. 2008. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "About the Carolina Quarterly". Carolina Quarterly. 2010. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ 2013년 9월 8일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 South The Rankings의 새로운 이야기. 순위가.wordpress.com (2010년 5월 1일). 2013년 8월 9일 회수.

- ^ PEN/O. 2012년 10월 24일 Wayback Machine에 보관된 Henry Prize Storys. Randomhouse.com . 2013년 8월 9일 회수.

- ^ "Founding Clef Hangers come home" 2013년 4월 14일 Wayback Machine, The Daily Tar Hheel, 2013년 4월 11일 보관. 2016년 4월 20일 회수.

- ^ a b "클랜스를 마주함 (2005)" 2016년 1월 29일, Wayback Machine, The Recorded Acappella Review Board, 2005년 9월 29일에 보관되었습니다. 2016년 4월 20일 회수.

- ^ CARA Winners 2008, 2016년 5월 8일 Wayback Machine, The Contemporary Acappella Society에 보관되었습니다. 2016년 4월 20일 회수.

- ^ CARA Winners 2009, 2016년 5월 8일 Wayback Machine, The Contemporary Acappella Society에 보관되었습니다. 2016년 4월 20일 회수.

- ^ Haller, Val (November 27, 2012). "If You Like Billy Joel, Try Brendan James". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Resience Hall Association". Heel Life. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "National Affiliation". UNC Residence Hall Association. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Flash Mob Rave: December 9 at the Undergraduate Library". Lib.unc.edu. December 16, 2008. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Athletic Bands". UNC Bands. 2008. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "About Playmakers". Playmakers Repertory Company. 2008. Archived from the original on March 30, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "About Carolina Performing Arts". Carolina Performing Arts. 2008. Archived from the original on June 21, 2006. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ^ "UNC.edu". Ncbg.unc.edu. Archived from the original on December 29, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ "The Carolina Story—Names Across the Landscape". Museum.unc.edu. Archived from the original on August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "OFSLCI". Greeks.unc.edu. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Student Honorary Societies". UNC. 2007. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ "Student Government". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Executive Branch". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "The Undergraduate Senate". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Graduate and Professional Student Government". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Joint Governance Council". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Honor system branches". UNC–Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Home". Student Supreme Court of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "Lenoir Dining Hall". Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ "Chase Dining Hall: A History". Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ "Facility Information". Archived from the original on April 26, 2003.

- ^ 사장님, 도나. "노스 캐롤라이나 대학의 램스 헤드 다이닝 센터." 모든 비즈니스. 2005년 12월 1일. 식품 서비스 장비 및 용품, 웹. 2009년 11월 10일. AllBusiness.com[dead link]

- ^ "North Campus Communities". Residence Halls. UNC Department of Housing and Residential Education. 2008. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Middle and South Campus Communities". Residence Halls. UNC Department of Housing and Residential Education. 2008. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "First Year Students". Residence Halls. UNC Department of Housing and Residential Education. 2017. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Learning Communities". UNC Department of Housing and Residential Education. 2008. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ "UNITAS". Living-Learning Communities. UNC Department of Housing and Residential Education. 2008. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Apartment Communities". UNC Department of Housing and Residential Education. 2008. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Smoking ban starts on New Year's Day". The News & Observer. Raleigh, NC. September 23, 2007. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "Housing and Campus Life". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. College Board. 2008. Archived from the original on February 6, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "UNC General Alumni Association:: About the GAA ". Alumni.unc.edu. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ "North Carolina History Project: James K. Polk (1795–1849)". Northcarolinahistory.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Art & History Home > William Rufus King, 13th Vice President (1853)". Senate.gov. May 29, 2012. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "Actor Andy Griffith dead at 86". CNN.com. December 11, 2012. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ a b "April Heinrichs Named Head Coach of the U.S. Women's National Team". U.S. Soccer. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "About". Hulu. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "Howard Levine – News, Articles, Biography, Photos". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

더보기

- Dulken, Danielle (August 22, 2019). "Places Dedicated to Enslavers and White Supremacists at UNC-Chapel Hill". Medium. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- 윌리스 P, 어느 쪽인가요? 결과론적 삶: 데이비드 로우리 스웨인, 19세기 노스캐롤라이나, 그리고 그들의 대학(2022) 요약