초대질량 블랙홀

Supermassive black hole

초대질량 블랙홀([a]SMBH 또는 SBH)은 질량이 태양의 수십만 배에서 수십억 배에 이르는 가장 큰 블랙홀 유형입니다.M☉블랙홀은 중력 붕괴를 겪은 천문학적인 물체의 한 종류로, 빛조차 빠져나갈 수 없는 우주의 구형 영역을 남깁니다.관측 증거는 거의 모든 큰 은하가 중심에 초대질량 블랙홀을 가지고 있다는 것을 보여줍니다.[5][6]예를 들어, 우리 은하의 중심에는 전파원 궁수자리 A*[7][8]에 해당하는 초대질량 블랙홀이 있습니다.초거대 블랙홀에 성간 가스를 부착하는 것은 활동은하핵(AGN)과 퀘이사에 동력을 공급하는 과정입니다.[9]

거대 타원 은하 메시에 87에 있는 블랙홀과 은하 중심에 있는 블랙홀 두 개의 초거대 블랙홀이 사건 지평선 망원경에 의해 직접 촬영되었습니다.[10]

묘사

초대질량 블랙홀은 고전적으로 질량이 태양질량 100,000 (105) 이상인 블랙홀로 정의됩니다.M☉ 일부는 몇 십억 개의 질량을 가지고 있습니다.M☉.☉초대질량[11] 블랙홀은 질량이 낮은 분류와 뚜렷하게 구별되는 물리적 특성을 가지고 있습니다.첫째, 사건 지평선 부근의 조석력은 초대질량 블랙홀에 비해 현저히 약합니다.블랙홀의 사건 지평선에 있는 물체에 가해지는 조석력은 블랙홀 질량의 제곱에 반비례합니다:[12] 사건 지평선에 있는 천만 명의 사람M☉ 블랙홀은 그들의 머리와 발 사이에 지구 표면의 사람과 같은 조석력을 경험합니다.항성질량 블랙홀과는 달리, 블랙홀의 사건 지평선 속으로 아주 깊이 들어가기 전까지는 상당한 조석력을 경험하지 못할 것입니다.[13]

사건 지평선 내 SMBH의 평균 밀도(블랙홀의 질량을 슈바르츠실트 반경 내 공간의 부피로 나눈 값으로 정의됨)가 물의 밀도보다 작을 수 있다는 것은 다소 직관적이지 않습니다.[14]이는 슈바르츠실트 반경( 이질량에 정비례하기 때문입니다.구형 물체의 부피(예: 회전하지 않는 블랙홀의 사건 지평선)는 반지름의 세제곱에 정비례하므로, 블랙홀의 밀도는 질량의 제곱에 반비례하므로, 질량이 큰 블랙홀은 평균 밀도가 더 낮습니다.[15]

약 10억개의 회전하지 않고 대전되지 않은 초대질량 블랙홀의 사건 지평선의 슈바르츠실트 반경M ☉ 이는 행성 우라누스의 공전 궤도의 장반경 축인 19 AU에 버금갑니다.[16][17]

일부 천문학자들은 50억개 이상의 블랙홀을 언급합니다.M☉ '초거대 블랙홀'(UMBHs 또는 UBHs)로 불리지만,[18] 이 용어는 널리 사용되지는 않습니다.가능한 예로는 TON 618, NGC 6166, ESO 444-46, NGC 4889의 중심에 있는 블랙홀을 들 수 있습니다.[19]

몇몇 연구에 따르면 블랙홀이 발광 가속기(강착원반을 특징으로 하는)일 때 도달할 수 있는 최대 자연질량은 일반적으로 약 500억 정도라고 합니다.M☉.☉하지만[20][21], 2020년의 한 연구는 질량이 1,000억 이상인 '놀라울 정도로 큰 블랙홀' (SLAB)이라고 불리는 더 큰 블랙홀을 제안했습니다.M☉ 비록 그러한 블랙홀이 진짜라는 증거는 현재 없지만, 사용된 모델에 근거하여 존재할 수 있습니다.[22][23]

연구이력

초대질량 블랙홀이 어떻게 발견되었는지에 대한 이야기는 1963년 라디오 소스 3C 273의 마르텐 슈미트에 의한 조사로부터 시작되었습니다.처음에 이것은 별로 생각되었지만, 스펙트럼은 혼란스러운 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.그것은 적색 이동된 수소 방출선으로 확인되었으며, 이는 물체가 지구로부터 멀어지고 있음을 나타냅니다.[24]허블의 법칙에 따르면 이 물체는 수십억 광년 떨어진 곳에 위치해 있으며, 따라서 수백 개의 은하에 해당하는 에너지를 방출하고 있을 것입니다.준성성체 또는 퀘이사라고 불리는 소스의 빛 변화율은 방출 영역의 직경이 1파섹 이하임을 시사합니다.1964년까지 4개의 그러한 출처가 확인되었습니다.[25]

1963년 프레드 호일과 W. A. 파울러는 퀘이사의 작은 크기와 높은 에너지 출력에 대한 설명으로 수소 연소 초거대 항성의 존재를 제안했습니다.이것들은 약 10에서5 109 정도의 질량을 가질 것입니다. 그러나 리처드 파인만은 특정 임계 질량 이상의 별들은 역학적으로 불안정하며 적어도 회전하지 않을 경우 블랙홀로 붕괴될 것이라고 언급했습니다.[26]그 후 파울러는 이 초대질량 별들이 일련의 붕괴와 폭발 진동을 겪을 것이라고 제안하여 에너지 출력 패턴을 설명했습니다.아펜젤러와 프리케(1972)는 이러한 행동의 모델을 만들었지만, 회전하지 않는 0.75×106 M☉ SMS는 "CNO 주기를 통해 수소를 연소시켜 블랙홀로 붕괴하는 것을 피할 수 없다"는 결론을 내리면서, 생성된 별은 여전히 붕괴를 겪을 것임을 발견했습니다.[27]

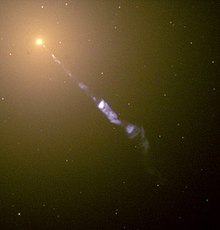

에드윈 E. 살페터와 야코프 젤도비치는 1964년에 거대한 소형 물체에 떨어지는 물질이 퀘이사의 특성을 설명할 수 있다는 제안을 했습니다.이 물체들의 출력과 일치하려면 10 정도의8 질량이 필요합니다.1969년, 도널드 린든-벨은 낙하하는 가스가 평평한 원반을 형성하여 슈바르츠실트 목구멍으로 나선형으로 들어간다고 언급했습니다.그는 근처 은하 중심부의 출력이 상대적으로 낮다는 것은 이것들이 오래되고 비활성화된 퀘이사라는 것을 암시한다고 지적했습니다.[28]한편 1967년 마틴 라일과 말콤 롱에어는 은하계에서 상대론적 속도로 입자가 방출되는 모델로 거의 모든 은하계 외 전파 방출원을 설명할 수 있다고 제안했는데, 이 모델은 입자가 빛의 속도에 가깝게 움직이고 있음을 의미합니다.[29]마틴 라일, 맬컴 롱에어, 피터 쇼이어는 1973년에 콤팩트한 중심핵이 이러한 상대론적 제트의 원천이 될 수 있다고 제안했습니다.[28]

아서 M 1970년 울프와 제프리 버비지는 타원은하의 핵 영역에 있는 별들의 큰 속도 분산은 보통의 별들이 설명할 수 있는 것보다 더 큰 핵의 큰 질량 집중에 의해서만 설명될 수 있다고 지적했습니다.그들은 그 행동이 최대 10개의10 거대한 블랙홀 또는 10개 미만의3 질량을 가진 많은 수의 작은 블랙홀에 의해 설명될 수 있다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[30] 거대한 어두운 물체에 대한 역학적 증거는 1978년에 활동 타원 은하 메시에 87의 중심에서 발견되었는데, 처음에는 5×109 M으로☉ 추정되었습니다.[31]1984년 안드로메다 은하와 1988년 솜브레로 은하를 포함한 다른 은하들에서도 유사한 행동이 발견되었습니다.[5]

1971년 도널드 린든-벨과 마틴 리스는 은하 중심부에 거대한 블랙홀이 있을 것이라는 가설을 세웠습니다.[32]궁수자리 A*는 1974년 2월 13일과 15일에 천문학자 브루스 발릭과 로버트 브라운이 국립전파천문대의 그린뱅크 간섭계를 이용하여 발견하고 이름을 붙였습니다.[33]그들은 싱크로트론 방사선을 방출하는 전파원을 발견했습니다; 그것은 중력 때문에 밀도가 높고 움직이지 않는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.따라서 이것은 초거대 블랙홀이 은하수 중심부에 존재한다는 것을 보여주는 첫 번째 증거였습니다.

1990년에 발사된 허블 우주 망원경은 은하핵의 더 정교한 관측을 수행하는 데 필요한 해상도를 제공했습니다.1994년 허블의 희미한 천체 분광기는 메시에 87을 관측하는 데 사용되었으며, 이온화된 기체가 핵의 중심 부분을 ±500 km/s의 속도로 돌고 있음을 발견했습니다.이 데이터는 0.25 ″ 범위 내에 (2.4±0.7)×10 M의 집중 질량을 나타냈고, 이는 초대질량 블랙홀의 강력한 증거를 제공했습니다.Messier 106을 관찰하기 위해 Very Long Baseline Array를 사용하여, Miyoshi et al. (1995)은 이 은하의 HO2 maser로부터의 방출이 반지름 0.13 파섹으로 제한된 3.6×107 M의☉ 집중 질량 주위를 도는 핵의 가스 디스크에서 나왔다는 것을 증명할 수 있었습니다.그들의 획기적인 연구는 이렇게 작은 반경 내에 있는 태양 질량 블랙홀 무리가 충돌을 겪지 않고는 오래 살아남지 못할 것이며, 이로 인해 초대질량 블랙홀이 유일하게 실행 가능한 후보가 될 것이라는 점에 주목했습니다.[35]초대질량 블랙홀의 최초 확인을 제공한 이 관찰에 수반된 것은 은하 MCG-6-30-15에서 매우 넓고 이온화된 철 Kα 방출선(6.4 keV)의 발견이었습니다[36].블랙홀에서 슈바르츠실트 반지름이 3에서 10개 밖에 되지 않아 빛이 중력에 의해 적색편이되었기 때문입니다.

2019년 4월 10일, 이벤트 지평선 망원경 공동 작업은 은하 메시에 87의 중심에 블랙홀의 첫 번째 지평선 이미지를 공개했습니다.[2]2020년 3월, 천문학자들은 추가적인 서브링이 광자 고리를 형성해야 한다고 제안했고, 첫 번째 블랙홀 이미지에서 이러한 특징을 더 잘 감지할 수 있는 방법을 제안했습니다.[37][38]

형성

초거대 블랙홀의 기원은 여전히 활발한 연구 분야로 남아 있습니다.천체 물리학자들은 블랙홀이 물질의 강착에 의해 그리고 다른 블랙홀들과 결합함으로써 성장할 수 있다는 것에 동의합니다.[39][40]초대질량 블랙홀의 형성 메커니즘과 초기 질량 또는 "씨앗"에 대한 몇 가지 가설이 있습니다.블랙홀 씨앗의 특정 형성 경로와 무관하게, 근처에 충분한 질량이 있다면, 이 블랙홀은 중간 질량 블랙홀이 될 수 있고, 강착 속도가 지속될 경우 SMBH가 될 수도 있습니다.[41]

J0313–1806과 [42]ULAS J1342+0928과 같은 멀고도 초기의 초대질량 블랙홀은 [43]빅뱅 직후에 설명하기가 어렵습니다.어떤 사람들은 그것들이 암흑 물질이 자기 상호작용과 직접적으로 붕괴하는 것에서 비롯된다고 가정합니다.[44][45][46]소수의 정보원들은 우주가 빅뱅이 아닌 빅뱅의 결과이며, 이러한 초거대 블랙홀들이 빅 바운스 이전에 형성되었다는 증거일 수 있다고 주장합니다.[47][48]

퍼스트스타즈

이 섹션을 업데이트해야 합니다.(2022년 11월) |

초기 조상의 씨앗은 수십개 혹은 수백개의 블랙홀일 수 있습니다.M☉ 거대한 별들의 폭발로 남겨진, 물질의 강착으로 인해 성장하는.또 다른 모델은 계의 음의 열용량이 중심부의 속도 분산을 상대론적 속도로 유도함에 따라 중심부 붕괴를 겪고 있는 밀집된 항성 성단을 포함합니다.[49][50]

최초의 별이 탄생하기 전에 거대한 가스 구름은 "준별"로 붕괴되어 약 20개의 블랙홀로 붕괴될 수 있습니다.M☉.☉이[41] 별들은 또한 중력에 의해 거대한 양의 가스를 끌어당기는 암흑 물질 후광에 의해 형성되었을지도 모릅니다, 그리고 나서 수만 개의 초거대 별들을 생성할 것입니다.M☉."☉준별[51][52]"은 중심핵에서 전자-양전자 쌍이 생성되기 때문에 방사상 섭동에 불안정해지고 초신성 폭발 없이 블랙홀로 바로 붕괴될 수 있습니다(이로 인해 질량의 대부분이 방출되어 블랙홀이 빠르게 성장하는 것을 막습니다).

좀 더 최근의 이론은 SMBH 씨앗들이 초기 우주에서 각각 약 100,000개의 질량을 가진 초대질량 별의 붕괴로부터 형성되었다고 제안합니다.M☉.[53]

직접붕괴 및 원시 블랙홀

금속이 없는 기체로 이루어진 크고 높은 적색편이 구름은 라이먼의 강력한 플럭스에 의해 조사될 [54]때-베르너 광자는 [55]냉각과 파편화를 피할 수 있어 자기중력에 의해 하나의 물체로 붕괴됩니다.[56][57]붕괴하는 물체의 중심핵은 물질 밀도가 약 10 g7/cm3 정도로 매우 큰 값에 도달하고 일반적인 상대론적 불안정성을 유발합니다.[58]따라서, 그 물체는 항성의 중간 단계나 준별의 중간 단계를 통과하지 않고 블랙홀로 바로 붕괴됩니다.이 물체들은 전형적으로 약 10만개의 질량을 가지고 있습니다.M☉ 직접 붕괴 블랙홀이라고 이름 붙여졌습니다.[59]2022년 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션에 따르면 최초의 초대질량 블랙홀은 이례적으로 강력한 차가운 가스 흐름에 의해 공급되는 원시 후광이라고 불리는 희귀한 난류성 가스 덩어리에서 발생할 수 있습니다.핵심적인 시뮬레이션 결과는 차가운 흐름이 난류성 헤일로의 별 형성을 억제하고, 마침내 헤일로의 중력이 난류를 극복하고 31,000개의 직접 붕괴된 블랙홀을 두 개 형성할 수 있었다는 것입니다.M☉ 그리고 4만명M☉.따라서 최초의 SMBH의 ☉탄생은 거의 20년 동안 생각되어 온 것과는 달리 표준적인 우주 구조 형성의 결과일 수 있습니다.[60][61]

마지막으로, 원시 블랙홀(PBH)은 빅뱅 후 첫 순간에 외부 압력으로부터 직접적으로 생성될 수 있었습니다.그러면 이 블랙홀들은 위의 어떤 모형들보다 더 많은 시간을 가지고 초질량 크기에 도달할 수 있는 충분한 시간을 가질 것입니다.첫 번째 별들의 죽음으로 인한 블랙홀의 형성은 광범위하게 연구되었고 관측을 통해 입증되었습니다.위에 나열된 블랙홀 형성의 다른 모델들은 이론적입니다.

초대질량 블랙홀의 형성에는 상대적으로 작은 각운동량을 가진 고밀도 물질이 필요합니다.일반적으로 강착 과정은 초기의 많은 각운동량을 바깥쪽으로 운반하는 것을 포함하며, 이것이 블랙홀 성장의 제한 요인으로 보입니다.이것은 강착원반 이론의 주요 구성요소입니다.가스 강착은 블랙홀이 성장하는 가장 효율적인 방법이자 가장 눈에 띄는 방법입니다.초대질량 블랙홀의 질량 증가의 대부분은 활동은하핵이나 퀘이사로 관측 가능한 급속한 가스 강착 에피소드를 통해 일어나는 것으로 생각됩니다.관측은 우주가 더 젊었을 때 퀘이사가 훨씬 더 자주 발생했다는 것을 보여주며, 초대질량 블랙홀이 형성되고 일찍 성장했다는 것을 나타냅니다.초대질량 블랙홀 형성 이론의 주요한 제약 요인은 수십 억 개의 초대질량 블랙홀을 나타내는 먼 발광 퀘이사의 관측입니다.M☉ 우주가 10억년이 채 되지 않았을 때 이미 형성되었습니다.이것은 초대질량 블랙홀이 우주 초기에 최초의 거대한 은하 내부에서 발생했다는 것을 암시합니다.[citation needed]

최대 질량 한계

초거대 블랙홀이 얼마나 크게 자랄 수 있는지에는 자연스러운 상한이 있습니다.퀘이사나 활동은하핵(AGN)에 있는 초대질량 블랙홀은 물리적으로 약 500억개의 이론적 상한선을 가지고 있는 것으로 보입니다.M☉ 일반적인 매개 변수의 경우, 이 이상의 것은 성장이 느려져서 크롤링(성장이 약 100억에서 시작되는 경향이 있음)M☉) 그리고 블랙홀을 둘러싸고 있는 불안정한 강착원반이 블랙홀 주위를 도는 별들로 합쳐지게 합니다.[20][65][66][67]한 연구는 SMBH 질량의 가장 안쪽에 있는 안정된 원형 궤도(ISCO)의 반지름이 이 한계를 초과하여 더 이상 원반 형성을 불가능하게 한다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[20]

약 2700억의 더 큰 상한선M 블랙홀의 스핀 매개변수에 대한 최대 한계가 a = 0.9982에서 매우 약간 낮지만, 극단적인 경우에 증가하는 SMBH에 대한 절대 최대 질량 한계로 표시되었습니다. 예를 들어, 무차원 스핀 매개변수가 a = 1인 최대 진행 스핀입니다.한계 바로 아래의 질량에서 필드 은하의 원반 광도는 에딩턴 한계 아래에 있을 가능성이 높고 M-시그마 관계의 근본적인 피드백을 유발할 만큼 충분히 강하지 않을 수 있으므로 한계에 가까운 SMBH는 이 이상으로 진화할 수 있습니다.[23]그러나 블랙홀이 성장하고 역행 강착의 스핀다운 효과가 ISCO와 그 레버 암으로 인해 점진적 강착에 의한 스핀업보다 크기 때문에 강착 디스크가 거의 영구적으로 진행되어야 하기 때문에 이 한계에 가까운 블랙홀은 오히려 훨씬 더 드물 것이라는 점에 주목했습니다.[20]이것은 결국 홀 스핀이 블랙홀의 숙주 은하 내의 잠재적 제어 가스 흐름의 고정된 방향과 영구적으로 상관되어야 하며, 따라서 스핀 축을 생성하고 따라서 은하와 유사하게 정렬되는 AGN 제트 방향을 생성하는 경향이 있습니다.그러나 현재 관측치에서는 이 상관 관계를 지원하지 않습니다.[20]이른바 '혼돈의 강착'은 아마도 이러한 방식으로 대규모 전위에 의해 제어되지 않으면 시간과 방향에서 본질적으로 무작위적인 다수의 소규모 사건을 수반해야 할 것입니다.[20]이는 역행 사건이 진행 사건보다 레버 암이 더 크고 거의 자주 발생하기 때문에 통계적으로 강착이 스핀다운으로 이어질 것입니다.[20]또한 대형 SMBH와 스핀을 줄이는 경향이 있는 다른 상호작용도 있습니다. 특히 통계적으로 스핀을 줄일 수 있는 다른 블랙홀과의 합병도 포함됩니다.[20]이러한 모든 고려 사항은 SMBH가 일반적으로 스핀 매개 변수의 적당한 값에서 임계 이론적 질량 한계를 초과하여, 드문 경우를 제외하고는 모두 5×10을10 초과한다는 것을 시사합니다.[20]

비록 퀘이사와 은하핵 내의 현대 UMBH가 강착원반을 통해 약 5~27×10배10 이상으로 성장할 수는 없지만, 우주의 현재 나이를 고려할 수 없습니다.우주의 이러한 괴물 블랙홀들 중 일부는 우주의 아주 먼 미래에 은하계의 초은하단이 붕괴되는 동안 아마도 10개의14 엄청나게 큰 질량까지 계속해서 성장할 것으로 예측됩니다.[69]

활동과 은하진화

많은 은하 중심에 있는 초대질량 블랙홀로부터의 중력은 세이퍼트 은하나 퀘이사와 같은 활동적인 물체에 동력을 공급하는 것으로 생각되며, 중심 블랙홀의 질량과 숙주 은하의 질량 사이의 관계는 은하의 종류에 따라 달라집니다.[70][71]초대질량 블랙홀의 크기와 은하 팽대부의 항성 속도 분산 σ \ 사이의 경험적 상관관계를 M-sigma 관계라고 합니다.

AGN은 현재 물질을 축적하고 있고 충분히 강한 광도를 보이는 거대한 블랙홀을 보유하고 있는 은하 중심부로 여겨지고 있습니다.예를 들어, 은하수의 핵 영역은 이 조건을 만족시키기에 충분한 광도가 부족합니다.AGN의 통일된 모델은 AGN 분류법의 관찰된 특성의 광범위한 범위를 적은 수의 물리적 매개변수를 사용하여 설명할 수 있다는 개념입니다.초기 모델의 경우, 이 값들은 강착원반의 시선에 대한 토러스의 각도와 광원의 광도로 구성되었습니다.AGN은 두 개의 주요 그룹으로 나눌 수 있는데, 대부분의 출력이 광학적으로 두꺼운 강착 디스크를 통해 전자기 복사 형태로 나타나는 복사 모드 AGN과 상대론적 제트가 디스크에 수직으로 나타나는 제트 모드입니다.[73]

SMBH의 합병 및 재동결

한 쌍의 SMBH 숙주 은하의 상호작용은 합병 사건을 야기할 수 있습니다.호스트된 SMBH 물체에 대한 동적 마찰은 물체가 병합된 질량의 중심으로 가라앉게 하고, 결국 킬로파섹 이하의 분리를 갖는 쌍을 형성합니다.이 쌍과 주변의 별 및 가스와의 상호작용은 SMBH를 10파섹 이하의 거리를 가진 중력 결합 쌍성계로 점차 결합시킬 것입니다.일단 두 쌍이 0.001 파섹만큼 가까이 끌어당기면 중력 복사로 인해 두 쌍이 합쳐지게 됩니다.이런 일이 일어날 때쯤이면, 생성된 은하는 합병 사건으로부터 오래 전에 완화되어 초기 별 폭발 활동과 AGN이 사라졌습니다.[74]

이 연합으로 인한 중력파는 결과적으로 SMBH에 최대 수천 km/s의 속도 상승을 줄 수 있으며, 은하 중심에서 멀어지게 하고 심지어 은하계에서 분출할 수도 있습니다.이 현상을 중력 반동이라고 합니다.[75]블랙홀을 방출하는 또 다른 가능한 방법은 고전적인 새총 시나리오인데, 새총 반동이라고도 합니다.이 시나리오에서는 먼저 두 은하의 결합을 통해 수명이 긴 쌍성 블랙홀이 형성됩니다.세 번째 SMBH는 두 번째 병합에서 도입되어 은하 중심부로 가라앉습니다.삼체 상호작용으로 인해 보통 가장 가벼운 SMBH 중 하나가 배출됩니다.선형 운동량 보존으로 인해 다른 두 SMBH는 이진법으로 반대 방향으로 추진됩니다.이 시나리오에서는 모든 SMBH를 꺼낼 수 있습니다.[76]분출된 블랙홀은 폭주 블랙홀이라고 불립니다.[77]

반동하는 블랙홀을 감지하는 방법에는 여러 가지가 있습니다.종종[78] 은하 중심으로부터의 퀘이사/AGN의 변위 또는 퀘이사/AGN의 분광 쌍성은 휘어진 블랙홀에 대한 증거로 간주됩니다.[79]

후보 반동 블랙홀로는 NGC 3718,[80] SDSS1133,[81] 3C 186,[82] E1821+643[83], SDSSJ0927+2943 등이 있습니다.[79]폭주 블랙홀 후보는 HE0450–2958,[78] CID-42[84] 및 RCP 28 주변의 물체들입니다.[85] 폭주하는 초거대 블랙홀은 깨어 있을 때 별의 형성을 유발할 수 있습니다.[77]왜소은하 RCP 28 근처의 선형 특징은 후보 폭주 블랙홀의 별 형성 현상으로 해석되었습니다.[85][86][87]

호킹 복사

호킹 방사선은 블랙홀에 의해 방출될 것으로 예측되는 흑체 방사선으로, 사건 지평선 근처의 양자 효과 때문입니다.이 방사선은 블랙홀의 질량과 에너지를 감소시켜 블랙홀이 줄어들고 궁극적으로 사라지게 만듭니다.만약 블랙홀이 호킹 복사를 통해 증발한다면, 질량이 1×10인11 회전하지 않고 대전되지 않은 엄청나게 큰 블랙홀은 약 2.1×10년100 안에 증발할 것입니다.[88][17]1×10으로14 먼 미래에 은하단의 초은하단이 붕괴될 것으로 예측되는 동안 형성된 블랙홀은 최대 2.1×10년의109 기간 동안 증발할 것입니다.[69][17]

증거

도플러 측정

블랙홀의 존재에 대한 가장 좋은 증거 중 일부는 가까운 궤도 물질의 빛이 후퇴할 때 적색편이되고 전진할 때 청색편이되는 도플러 효과에 의해 제공됩니다.블랙홀에 매우 가까운 물질의 경우 궤도 속도는 빛의 속도와 비교할 수 있어야 하므로 후퇴 물질은 진행 물질에 비해 매우 희미하게 보일 것이며, 이는 고유하게 대칭된 디스크와 고리를 가진 계가 매우 비대칭적인 시각적 외관을 얻을 것임을 의미합니다.이 효과는 은하수 중심에 있는 Sgr A*의 초대질량 블랙홀에 대한 그럴듯한 모델에[89] 기초하여 여기에 제시된 예와 같은 현대의 컴퓨터 생성 이미지에서 허용되었습니다.그러나, 현재 이용 가능한 망원경 기술에 의해 제공되는 해상도는 그러한 예측을 직접적으로 확인하기에는 여전히 부족합니다.

이미 많은 계에서 직접 관측된 것은 블랙홀로 추정되는 것에서 더 멀리 떨어진 궤도를 도는 물질의 낮은 비상대론적 속도입니다.주변 은하의 핵을 둘러싸고 있는 워터마스터들의 직접적인 도플러 측정은 매우 빠른 케플러 운동을 보여주었는데, 이는 오직 중심에 있는 물질의 농도가 높은 경우에만 가능합니다.현재, 그렇게 작은 공간에서 충분한 물질을 담을 수 있는 유일한 물체는 블랙홀, 또는 천체물리학적으로 짧은 시간 내에 블랙홀로 진화할 것들입니다.더 멀리 있는 활동은하의 경우 넓은 스펙트럼 선의 폭을 사용하여 사건 지평선 근처를 도는 가스를 탐사할 수 있습니다.잔향 매핑 기술은 이러한 선들의 가변성을 사용하여 질량과 아마도 활동은하에 동력을 공급하는 블랙홀의 스핀을 측정합니다.

은하수에서

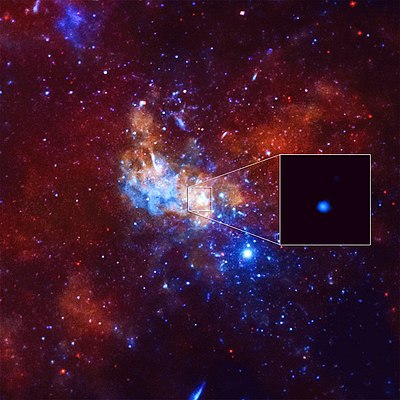

우리 은하의 중심에는 궁수자리 A*[91]라고 불리는 지역에서 태양계로부터 26,000광년 떨어진 초거대 블랙홀이 있다는 증거가 있습니다.

- 항성 S2는 중심 천체의 중심으로부터 15.2년의 주기와 17광시(1.8×1013 m 또는 120 AU)의 중심점(가장 가까운 거리)을 따라 공전합니다.[92]

- 항성 S2의 운동으로 볼 때, 천체의 질량은 400만으로 추정할 수 있습니다.M☉,☉또는[93] 약 7.96 × 10 kg36.

- 중심 천체의 반지름은 17광시 미만이어야 합니다. 그렇지 않으면 S2가 중심 천체와 충돌하기 때문입니다.항성 S14를[94] 관측한 결과 반지름은 천왕성 궤도 지름의 6.25 광시(光時)에 불과합니다.

- 블랙홀 외에 알려진 어떤 천체도 400만개를 포함할 수 없습니다.M☉ 이 넓은 [94]공간에

궁수자리 A* 근처의 밝은 플레어 활동에 대한 적외선 관측은 후보 SMBH 중력 반경의 6배에서 10배의 간격에서 45±15분의 주기를 가진 플라즈마의 궤도 운동을 보여줍니다.이 방출은 강한 자기장 안에 있는 강착원반 위의 편광된 "핫 스팟"의 원형 궤도와 일치합니다.복사 물질은 가장 안쪽의 안정된 원형 궤도 바로 바깥쪽에서 빛의 속도의 30%로 공전하고 있습니다.[95]

2015년 1월 5일, NASA는 궁수자리 A*로부터 평소보다 400배나 밝은 X선 플레어를 관측했다고 보고했습니다.천문학자들에 따르면, 이 특이한 사건은 블랙홀로 떨어지는 소행성의 부서짐이나 궁수자리 A*로 유입되는 가스 안에 자기장 선이 얽히면서 발생했을 수도 있다고 합니다.[96]

은하수 바깥쪽

초거대 블랙홀에 대한 명확한 동적 증거는 소수의 은하에만 존재합니다.[98] 은하수, 국부 그룹 은하 M31과 M32, 그리고 NGC 4395와 같은 국부 그룹을 벗어난 몇몇 은하들이 여기에 포함됩니다.이 은하들에서 항성이나 기체의 평균 제곱근(또는 rms) 속도는 1/1에 비례하여 증가합니다.r중심 부근에서 중심점 질량을 나타냅니다.현재까지 관측된 다른 모든 은하에서 rms 속도는 중심을 향해 평평하거나 심지어 떨어지는 것으로, 초대질량 블랙홀이 존재한다는 것을 확실하게 밝히는 것은 불가능합니다.[98]그럼에도 불구하고, 거의 모든 은하의 중심에는 초대질량 블랙홀이 있다는 것이 일반적으로 받아들여지고 있습니다.[99]이러한 가정의 이유는 M-시그마 관계, 안전한 탐지가 있는 10개 정도의 은하에 있는 구멍의 질량과 해당 은하의 볼록부에 있는 별들의 속도 분산 사이의 긴밀한(저산란) 관계 때문입니다.[100]이 상관관계는 비록 단지 소수의 은하에 기초하고 있지만, 많은 천문학자들에게 블랙홀의 형성과 은하 자체 사이의 강한 연관성을 암시합니다.[99]

2011년 3월 28일, 초거대 블랙홀이 중간 크기의 별을 찢는 것이 목격되었습니다.[101]그것이 그 날 갑자기 발생한 X선 복사 관측과 후속 광대역 관측에 대한 유일한 설명일 가능성이 있습니다.[102][103]그 근원은 이전에 비활성 은하핵이었고, 폭발에 대한 연구로부터 은하핵은 100만개 정도의 질량을 가진 SMBH로 추정되었습니다.M☉.이 ☉드문 사건은 SMBH에 의해 조수적으로 교란된 항성으로부터의 상대론적 유출(물질이 광속의 상당한 부분으로 제트에서 방출됨)로 추정됩니다. 물질 덩어리의 상당한 부분이 SMBH에 축적되었을 것으로 예상됩니다. 이후의 장기적인 관측으로 이 가정은 확인될 수 있을 것입니다.SMBH로의 질량 강착에 대한 예상 속도로 제트의 방출량이 감소할 경우 med.

개별학문

250만 광년 떨어진 안드로메다 은하는 1.4+0.65-0

.45×108 (1억 4천만 광년)을 포함하고 있습니다.M☉ 우리 은하보다 훨씬 [104]큰 중앙 블랙홀은하수 근처에서 가장 큰 초대질량 블랙홀은 메시에 87(즉, M87*)의 질량으로 4,892만 광년 거리에서 (6.5±0.7)×109(c.65억) 정도 됩니다.[105]코마 베레니케 별자리에서 3억3600만 광년 떨어진 곳에 있는 초거대 타원 은하 NGC 4889는 2.1+3.5-1

.3×1010(210억) 크기의 블랙홀을 포함하고 있습니다.M☉.[106]

퀘이사의 블랙홀 질량은 상당한 불확실성이 있는 간접적인 방법을 통해 추정될 수 있습니다.퀘이사 TON 618은 6.6 x 1010 (660억)으로 추정되는 매우 큰 블랙홀을 가진 물체의 예입니다.M☉.☉적색편이는[107] 2.219입니다.블랙홀 질량이 큰 다른 퀘이사의 예로는 초대광성 퀘이사 APM 08279+5255가 있으며, 질량은 1×1010(100억)으로 추정됩니다.M☉,☉질량이[108] (3.4±0.6)×10(340억)인10 퀘이사 SMSS J215728.21-360215.1M☉,☉또는 우리 은하의 은하 중심에 있는 블랙홀의 거의 만 배의 질량입니다.[109]

은하 4C +37.11과 같은 일부 은하는 중심에 두 개의 초거대 블랙홀이 있는 것으로 보이며, 쌍성계를 형성합니다.만약 그들이 충돌한다면, 이 사건은 강한 중력파를 만들어 낼 것입니다.[110]쌍성 초대질량 블랙홀은 은하 병합의 일반적인 결과로 여겨집니다.[111]35억 광년 떨어진 OJ 287에 있는 쌍성 쌍성은 질량이 183억 4,800만으로 추정되는 한 쌍의 가장 무거운 블랙홀을 포함하고 있습니다.M☉.☉2011년에는[112][113] 팽대부가 없는 왜소은하 헤니즈 2-10에서 초거대 블랙홀이 발견되기도 했습니다.블랙홀 형성에 대한 이 발견의 정확한 의미는 알려지지 않았지만, 블랙홀이 불룩해지기 전에 형성되었음을 나타낼 수 있습니다.[114]

2012년 천문학자들은 이례적으로 큰 질량이 약 170억개에 달한다고 보고했습니다.M ☉ 페르세우스자리에 있는 2억 2천만 광년 떨어져 있는 작고 렌티큘라 은하 NGC 1277의 블랙홀 때문입니다.블랙홀로 추정되는 이 렌즈형 은하의 팽대부 질량의 약 59%(은하 전체 항성 질량의 14%)를 가지고 있습니다.[115]또 다른 연구는 매우 다른 결론에 도달했습니다: 이 블랙홀은 20억에서 50억 사이로 추정되는, 특별히 과도한 질량은 아닙니다.M☉ 50억으로M☉ 가장 가능성이 높은 가치입니다.[116]2013년 2월 28일, 천문학자들은 NuSTAR 위성을 이용하여 초거대 블랙홀의 스핀을 처음으로 정확하게 측정했다고 NGC 1365에서 보고하면서 사건 지평선이 거의 빛의 속도로 회전하고 있다고 보고했습니다.[117][118]

2014년 9월, 여러 X선 망원경의 데이터에 따르면 매우 작고 밀도가 높은 초소형 왜소 은하 M60-UCD1은 중심에 2천만 개의 태양 질량 블랙홀을 보유하고 있으며, 이 블랙홀은 은하 전체 질량의 10% 이상을 차지하고 있습니다.은하의 질량이 은하의 5천분의 1 이하임에도 불구하고 블랙홀은 은하의 블랙홀보다 5배나 더 무겁기 때문에 이번 발견은 매우 놀라운 일입니다.

어떤 은하들은 중심에 초거대 블랙홀이 없습니다.초대질량 블랙홀이 없는 대부분의 은하들은 매우 작고 왜소한 은하이지만, 한 가지 발견은 여전히 수수께끼로 남아 있습니다.초거대 타원형 cD 은하 A2261-BCG는 이 은하가 알려진 가장 큰 은하 중 하나임에도 불구하고 최소 10개10 이상의 활성 초거대 블랙홀을 포함하고 있는 것으로 발견되지 않았습니다.그럼에도 불구하고, 몇몇 연구들은 A2261-BGC 내부의 가능한 중심 블랙홀에 대해 6.5+10.9-4

.1×1010 또는 (6–11)×10과9 같이 매우 큰 질량 값을 부여했습니다. 초거대 블랙홀은 강착하는 동안에만 보일 수 있기 때문에, 초거대 블랙홀은 항성 궤도에 미치는 영향을 제외하고는 거의 보이지 않을 수 있습니다.이것은 A2261-BGC 중 하나가 낮은 단계에 있거나 질량이 1010 미만인 중심 블랙홀을 가지고 있음을 의미합니다.[119]

2017년 12월 천문학자들은 이때까지 알려진 가장 먼 퀘이사 ULAS J1342+0928을 발견했다고 보고했는데, 이는 가장 먼 초거대 블랙홀을 포함하고 있으며 적색편이 z = 7.54로 이전에 알려진 가장 먼 퀘이사 ULAS J1120+0641의 적색편이 7을 넘어섰습니다.

(1:22; 애니메이션; 2020년 4월 28일)

출처: Chandra X-ray 천문대

2020년 2월, 천문학자들은 빅뱅 이후 우주에서 발견된 가장 강력한 사건인 오피우쿠스 초은하단 폭발의 발견을 보고했습니다.[123][124][125]그것은 거의 2억 7천만의 강착에 의해 야기된 은하 NeVe 1의 Ophiuchus 성단에서 발생했습니다.M☉ 중심의 초대질량 블랙홀에 의한 물질의.이 폭발은 약 1억 년 동안 지속되었으며 알려진 가장 강력한 감마선 폭발보다 570만 배나 더 많은 에너지를 방출했습니다.이 폭발은 충격파와 고에너지 입자의 분출물을 방출하여 은하수 지름의 10배인 약 150만 광년 폭의 공동을 형성했습니다.[126][123][127][128]

2021년 2월, 천문학자들은 유럽의 저주파 배열(LOFAR)에 의해 감지된 초저전파 파장을 기반으로 북반구의 4%를 차지하는 25,000개의 활성 초거대 블랙홀의 매우 높은 해상도 이미지를 처음으로 공개했습니다.[129]

참고 항목

- 소설 속 블랙홀 – 블랙홀이 등장하는 소설

- 은하 중심 GeV 과잉 – 은하 중심부의 설명되지 않은 감마선 복사

- 초소형 항성계 – 초거대 주위에 있는 별들의 군집 )

- 스핀 플립 – 다른 블랙홀과의 병합으로 인한 스핀축의 급격한 변화

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (April 10, 2019). "Black Hole Picture Revealed for the First Time – Astronomers at last have captured an image of the darkest entities in the cosmos – Comments". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ a b The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (April 10, 2019). "First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 875 (1): L1. arXiv:1906.11238. Bibcode:2019ApJ...875L...1E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab0ec7.

- ^ The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration; Akiyama, Kazunori; Alberdi, Antxon; Alef, Walter; Asada, Keiichi; Azulay, Rebecca; Baczko, Anne-Kathrin; Ball, David; Baloković, Mislav; Barrett, John; Bintley, Dan; Blackburn, Lindy; Boland, Wilfred; Bouman, Katherine L.; Bower, Geoffrey C. (April 10, 2019). "First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. V. Physical Origin of the Asymmetric Ring". The Astrophysical Journal. 875 (1): See especially Fig. 5. arXiv:1906.11242. Bibcode:2019ApJ...875L...5E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab0f43. hdl:10150/633753. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 145894922.

- ^ The Real Science of the EHT Black Hole, retrieved August 10, 2023t = 8분

- ^ a b Kormendy, John; Richstone, Douglas (1995), "Inward Bound—The Search For Supermassive Black Holes In Galactic Nuclei", Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 33: 581, Bibcode:1995ARA&A..33..581K, doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.33.090195.003053

- ^ Kormendy, John; Ho, Luis (2013). "Coevolution (Or Not) of Supermassive Black Holes and Host Galaxies". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 51 (1): 511–653. arXiv:1304.7762. Bibcode:2013ARA&A..51..511K. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101811. S2CID 118172025.

- ^ Ghez, A.; Klein, B.; Morris, M.; Becklin, E (1998). "High Proper-Motion Stars in the Vicinity of Sagittarius A*: Evidence for a Supermassive Black Hole at the Center of Our Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal. 509 (2): 678–686. arXiv:astro-ph/9807210. Bibcode:1998ApJ...509..678G. doi:10.1086/306528. S2CID 18243528.

- ^ Schödel, R.; et al. (2002). "A star in a 15.2-year orbit around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way". Nature. 419 (6908): 694–696. arXiv:astro-ph/0210426. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..694S. doi:10.1038/nature01121. PMID 12384690. S2CID 4302128.

- ^ Frank, Juhan; King, Andrew; Raine, Derek J. (January 2002). "Accretion Power in Astrophysics: Third Edition". Accretion Power in Astrophysics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Bibcode:2002apa..book.....F. ISBN 0521620538.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (May 12, 2022). "Has the Milky Way's Black Hole Come to Light? - The Event Horizon Telescope reaches again for a glimpse of the "unseeable."". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "Black Hole COSMOS". astronomy.swin.edu.au. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ Kutner, Marc L. (2003), Astronomy: A Physical Perspective, Cambridge University Press, p. 149, ISBN 978-0521529273

- ^ "Problem 138: The Intense Gravity of a Black Hole", Space Math @ NASA: Mathematics Problems about Black Holes, NASA, retrieved December 4, 2018

- ^ Celotti, A.; Miller, J.C.; Sciama, D.W. (1999). "Astrophysical evidence for the existence of black holes". Class. Quantum Grav. (Submitted manuscript). 16 (12A): A3–A21. arXiv:astro-ph/9912186. Bibcode:1999CQGra..16A...3C. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/16/12A/301. S2CID 17677758.

- ^ Ehsan, Baaquie Belal; Hans, Willeboordse Frederick (2015), Exploring The Invisible Universe: From Black Holes To Superstrings, World Scientific, p. 200, Bibcode:2015eiub.book.....B, ISBN 978-9814618694

- ^ "Uranus Fact Sheet". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Black Hole Calculator – Fabio Pacucci (Harvard University & SAO)". Fabio Pacucci. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ Natarajan, Priyamvada; Treister, Ezequiel (2009). "Is there an upper limit to black hole masses?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 393 (3): 838–845. arXiv:0808.2813. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.393..838N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13864.x. S2CID 6568320.

- ^ "Massive Black Holes Dwell in Most Galaxies, According to Hubble Census". HubbleSite.org. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j King, Andrew (2016). "How big can a black hole grow?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 456 (1): L109–L112. arXiv:1511.08502. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.456L.109K. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slv186. S2CID 40147275.

- ^ Inayoshi, Kohei; Haiman, Zoltán (September 12, 2016). "Is There a Maximum Mass for Black Holes in Galactic Nuclei?". The Astrophysical Journal. 828 (2): 110. arXiv:1601.02611. Bibcode:2016ApJ...828..110I. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/828/2/110. S2CID 118702101.

- ^ September 2020, Charles Q. Choi 18 (September 18, 2020). "'Stupendously large' black holes could grow to truly monstrous sizes". Space.com. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c Carr, Bernard; et al. (February 2021). "Constraints on Stupendously Large Black Holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 501 (2): 2029–2043. arXiv:2008.08077. Bibcode:2021MNRAS.501.2029C. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa3651.

- ^ Schmidt, Maarten (1965), Robinson, Ivor; Schild, Alfred; Schucking, E.L. (eds.), 3C 273: A Star-like Object with Large Red-Shift, Quasi-Stellar Sources and Gravitational Collapse: Proceedings of the 1st Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics, Quasi-Stellar Sources and Gravitational Collapse, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 455, Bibcode:1965qssg.conf..455S

- ^ Greenstein, Jesse L.; Schmidt, Maarten (July 1, 1964), "The Quasi-Stellar Radio Sources 3C 48 and 3C 273", Astrophysical Journal, 140: 1, Bibcode:1964ApJ...140....1G, doi:10.1086/147889, S2CID 123147304

- ^ Feynman, Richard (2018), Feynman Lectures on Gravitation, CRC Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0429982484

- ^ Appenzeller, I.; Fricke, K. (April 1972), "Hydrodynamic Model Calculations for Supermassive Stars I. The Collapse of a Nonrotating 0.75×106M☉ Star", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 18: 10, Bibcode:1972A&A....18...10A

- ^ a b Lang, Kenneth R. (2013), Astrophysical Formulae: Space, Time, Matter and Cosmology, Astronomy and Astrophysics Library (3 ed.), Springer, p. 217, ISBN 978-3662216392

- ^ Ryle, Martin, Sir; Longair, M. S. (1967), "A possible method for investigating the evolution of radio galaxies", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 136 (2): 123, Bibcode:1967MNRAS.136..123R, doi:10.1093/mnras/136.2.123

{{cite journal}}: CS1 유지 : 여러 이름 : 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ Wolfe, A. M.; Burbidge, G. R. (August 1970), "Black Holes in Elliptical Galaxies", Astrophysical Journal, 161: 419, Bibcode:1970ApJ...161..419W, doi:10.1086/150549

- ^ Sargent, W. L. W.; et al. (May 1, 1978), "Dynamical evidence for a central mass concentration in the galaxy M87", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 221: 731–744, Bibcode:1978ApJ...221..731S, doi:10.1086/156077

- ^ Schödel, R.; Genzel, R. (2006), Alfaro, Emilio Javier; Perez, Enrique; Franco, José (eds.), How does the Galaxy work?: A Galactic Tertulia with Don Cox and Ron Reynolds, Astrophysics and Space Science Library, vol. 315, Springer Science & Business Media, p. 201, ISBN 978-1402026201

- ^ Fulvio Melia (2007), The Galactic Supermassive Black Hole, Princeton University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-0-691-13129-0

- ^ Harms, Richard J.; et al. (November 1994), "HST FOS spectroscopy of M87: Evidence for a disk of ionized gas around a massive black hole", Astrophysical Journal, Part 2, 435 (1): L35–L38, Bibcode:1994ApJ...435L..35H, doi:10.1086/187588

- ^ Miyoshi, Makoto; et al. (January 1995), "Evidence for a black hole from high rotation velocities in a sub-parsec region of NGC4258", Nature, 373 (6510): 127–129, Bibcode:1995Natur.373..127M, doi:10.1038/373127a0, S2CID 4336316

- ^ Tanaka, Y.; Nandra, K.; Fabian, A. C. (1995), "Gravitationally redshifted emission implying an accretion disk and massive black hole in the active galaxy MCG-6-30-15", Nature, 375 (6533): 659–661, Bibcode:1995Natur.375..659T, doi:10.1038/375659a0, S2CID 4348405

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 28, 2020), "Infinite Visions Were Hiding in the First Black Hole Image's Rings", The New York Times, retrieved March 29, 2020

- ^ Johnson, Michael D.; et al. (March 18, 2020), "Universal interferometric signatures of a black hole's photon ring", Science Advances, 6 (12, eaaz1310): eaaz1310, arXiv:1907.04329, Bibcode:2020SciA....6.1310J, doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz1310, PMC 7080443, PMID 32206723

- ^ Kulier, Andrea; Ostriker, Jeremiah P.; Natarajan, Priyamvada; Lackner, Claire N.; Cen, Renyue (February 1, 2015). "Understanding Black Hole Mass Assembly via Accretion and Mergers at Late Times in Cosmological Simulations". The Astrophysical Journal. 799 (2): 178. arXiv:1307.3684. Bibcode:2015ApJ...799..178K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/799/2/178. S2CID 118497238.

- ^ Pacucci, Fabio; Loeb, Abraham (June 1, 2020). "Separating Accretion and Mergers in the Cosmic Growth of Black Holes with X-Ray and Gravitational-wave Observations". The Astrophysical Journal. 895 (2): 95. arXiv:2004.07246. Bibcode:2020ApJ...895...95P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab886e. S2CID 215786268.

- ^ a b Begelman, M. C.; et al. (June 2006). "Formation of supermassive black holes by direct collapse in pre-galactic haloed". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 370 (1): 289–298. arXiv:astro-ph/0602363. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.370..289B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10467.x. S2CID 14545390.

- ^ Harrison Tasoff (January 19, 2021). "Researchers discover the earliest supermassive black hole and quasar in the universe". phys.org.

The presence of such a massive black hole so early in the universe's history challenges theories of black hole formation. As lead author [Feige] Wang, now a NASA Hubble fellow at the University of Arizona, explains: 'Black holes created by the very first massive stars could not have grown this large in only a few hundred million years.'

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth; Bañados, Eduardo (December 6, 2017). "Found: Most Distant Black Hole". NASA. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

'This black hole grew far larger than we expected in only 690 million years after the Big Bang, which challenges our theories about how black holes form,' said study co-author Daniel Stern of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

- ^ Balberg, Shmuel; Shapiro, Stuart L. (2002). "Gravothermal Collapse of Self-Interacting Dark Matter Halos and the Origin of Massive Black Holes". Physical Review Letters. 88 (10): 101301. arXiv:astro-ph/0111176. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88j1301B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.101301. PMID 11909338. S2CID 20557031.

- ^ Pollack, Jason; Spergel, David N.; Steinhardt, Paul J. (2015). "Supermassive Black Holes from Ultra-Strongly Self-Interacting Dark Matter". The Astrophysical Journal. 804 (2): 131. arXiv:1501.00017. Bibcode:2015ApJ...804..131P. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/804/2/131. S2CID 15916893.

- ^ Feng, W.-X.; Yu, H.-B.; Zhong, Y.-M. (2021). "Seeding Supermassive Black Holes with Self-interacting Dark Matter: A Unified Scenario with Baryons". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 914 (2): L26. arXiv:2010.15132. Bibcode:2021ApJ...914L..26F. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac04b0. S2CID 225103030.

- ^ Seidel, Jamie (December 7, 2017). "Black hole at the dawn of time challenges our understanding of how the universe was formed". News Corp Australia. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

It had reached its size just 690 million years after the point beyond which there is nothing. The most dominant scientific theory of recent years describes that point as the Big Bang—a spontaneous eruption of reality as we know it out of a quantum singularity. But another idea has recently been gaining weight: that the universe goes through periodic expansions and contractions—resulting in a 'Big Bounce'. And the existence of early black holes has been predicted to be a key telltale as to whether or not the idea may be valid. This one is very big. To get to its size—800 million times more mass than our Sun—it must have swallowed a lot of stuff. ... As far as we understand it, the universe simply wasn't old enough at that time to generate such a monster.

- ^ "A Black Hole that is more ancient than the Universe" (in Greek). You Magazine (Greece). December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

This new theory that accepts that the Universe is going through periodic expansions and contractions is called 'Big Bounce'

- ^ Spitzer, L. (1987). Dynamical Evolution of Globular Clusters. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08309-4.

- ^ Boekholt, T. C. N.; Schleicher, D. R. G.; Fellhauer, M.; Klessen, R. S.; Reinoso, B.; Stutz, A. M.; Haemmerlé, L. (May 1, 2018). "Formation of massive seed black holes via collisions and accretion". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 476 (1): 366–380. arXiv:1801.05841. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.476..366B. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty208. S2CID 55411455.

- ^ Saplakoglu, Yasemin (September 29, 2017). "Zeroing In on How Supermassive Black Holes Formed". Scientific American. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Johnson-Goh, Mara (November 20, 2017). "Cooking up supermassive black holes in the early universe". Astronomy. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Pasachoff, Jay M. (2018). "Supermassive star". Access Science. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.669400.

- ^ Yue, Bin; Ferrara, Andrea; Salvaterra, Ruben; Xu, Yidong; Chen, Xuelei (May 1, 2014). "The brief era of direct collapse black hole formation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 440 (2): 1263–1273. arXiv:1402.5675. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.440.1263Y. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu351. S2CID 119275449.

- ^ Sugimura, Kazuyuki; Omukai, Kazuyuki; Inoue, Akio K. (November 1, 2014). "The critical radiation intensity for direct collapse black hole formation: dependence on the radiation spectral shape". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 445 (1): 544–553. arXiv:1407.4039. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.445..544S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1778. S2CID 119257740.

- ^ Bromm, Volker; Loeb, Abraham (October 1, 2003). "Formation of the First Supermassive Black Holes". The Astrophysical Journal. 596 (1): 34–46. arXiv:astro-ph/0212400. Bibcode:2003ApJ...596...34B. doi:10.1086/377529. S2CID 14419385.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan. "'Direct Collapse' Black Holes May Explain Our Universe's Mysterious Quasars". Forbes. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Montero, Pedro J.; Janka, Hans-Thomas; Müller, Ewald (April 1, 2012). "Relativistic Collapse and Explosion of Rotating Supermassive Stars with Thermonuclear Effects". The Astrophysical Journal. 749 (1): 37. arXiv:1108.3090. Bibcode:2012ApJ...749...37M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/749/1/37. S2CID 119098587.

- ^ Habouzit, Mélanie; Volonteri, Marta; Latif, Muhammad; Dubois, Yohan; Peirani, Sébastien (November 1, 2016). "On the number density of 'direct collapse' black hole seeds". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 463 (1): 529–540. arXiv:1601.00557. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.463..529H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1924. S2CID 118409029.

- ^ "Revealing the origin of the first supermassive black holes". Nature. July 6, 2022. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01560-y. PMID 35794378.

State-of-the-art computer simulations show that the first supermassive black holes were born in rare, turbulent reservoirs of gas in the primordial Universe without the need for finely tuned, exotic environments — contrary to what has been thought for almost two decades.

- ^ "Scientists discover how first quasars in universe formed". phys.org. Provided by University of Portsmouth. July 6, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ "Biggest Black Hole Blast Discovered". ESO Press Release. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ "Artist's illustration of galaxy with jets from a supermassive black hole". Hubble Space Telescope. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Stars Born in Winds from Supermassive Black Holes – ESO's VLT spots brand-new type of star formation". www.eso.org. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ Trosper, Jaime (May 5, 2014). "Is There a Limit to How Large Black Holes Can Become?". futurism.com. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Clery, Daniel (December 21, 2015). "Limit to how big black holes can grow is astonishing". sciencemag.org. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Black holes could grow as large as 50 billion suns before their food crumbles into stars, research shows". University of Leicester. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Kovács, Zoltán; Gergely, Lászlóá.; Biermann, Peter L. (2011). "Maximal spin and energy conversion efficiency in a symbiotic system of black hole, disc and jet". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 416 (2): 991–1009. arXiv:1007.4279. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.416..991K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19099.x. S2CID 119255235.

- ^ a b Frautschi, S (1982). "Entropy in an expanding universe". Science. 217 (4560): 593–599. Bibcode:1982Sci...217..593F. doi:10.1126/science.217.4560.593. PMID 17817517. S2CID 27717447.

p. 596: table 1 and section "black hole decay" and previous sentence on that page: "Since we have assumed a maximum scale of gravitational binding – for instance, superclusters of galaxies – black hole formation eventually comes to an end in our model, with masses of up to 1014 M☉ ... the timescale for black holes to radiate away all their energy ranges ... to 10106 years for black holes of up to 1014 M☉

- ^ Savorgnan, Giulia A.D.; Graham, Alister W.; Marconi, Alessandro; Sani, Eleonora (2016). "Supermassive Black Holes and Their Host Spheroids. II. The Red and Blue Sequence in the MBH-M*,sph Diagram". Astrophysical Journal. 817 (1): 21. arXiv:1511.07437. Bibcode:2016ApJ...817...21S. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/817/1/21. S2CID 55698824.

- ^ Sahu, Nandini; Graham, Alister W.; Davis, Benjamin L. (2019). "Black Hole Mass Scaling Relations for Early-type Galaxies. I. MBH-M*,sph and MBH-M*,gal". Astrophysical Journal. 876 (2): 155. arXiv:1903.04738. Bibcode:2019ApJ...876..155S. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab0f32. S2CID 209877088.

- ^ Gultekin K; et al. (2009). "The M—σ and M-L Relations in Galactic Bulges, and Determinations of Their Intrinsic Scatter". The Astrophysical Journal. 698 (1): 198–221. arXiv:0903.4897. Bibcode:2009ApJ...698..198G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/698/1/198. S2CID 18610229.

- ^ Netzer, Hagai (August 2015). "Revisiting the Unified Model of Active Galactic Nuclei". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 53: 365–408. arXiv:1505.00811. Bibcode:2015ARA&A..53..365N. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-082214-122302. S2CID 119181735.

- ^ Tremmel, M.; et al. (April 2018). "Dancing to CHANGA: a self-consistent prediction for close SMBH pair formation time-scales following galaxy mergers". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (4): 4967–4977. arXiv:1708.07126. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.4967T. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty139.

- ^ Komossa, S. (2012). "Recoiling Black Holes: Electromagnetic Signatures, Candidates, and Astrophysical Implications". Advances in Astronomy. 2012: 364973. arXiv:1202.1977. Bibcode:2012AdAst2012E..14K. doi:10.1155/2012/364973. 364973.

- ^ Saslaw, William C.; Valtonen, Mauri J.; Aarseth, Sverre J. (June 1, 1974). "The Gravitational Slingshot and the Structure of Extragalactic Radio Sources". The Astrophysical Journal. 190: 253–270. Bibcode:1974ApJ...190..253S. doi:10.1086/152870. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b de la Fuente Marcos, R.; de la Fuente Marcos, C. (April 2008). "The Invisible Hand: Star Formation Triggered by Runaway Black Holes". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 677 (1): L47. Bibcode:2008ApJ...677L..47D. doi:10.1086/587962. S2CID 250885688.

- ^ a b Magain, Pierre; Letawe, Géraldine; Courbin, Frédéric; Jablonka, Pascale; Jahnke, Knud; Meylan, Georges; Wisotzki, Lutz (September 1, 2005). "Discovery of a bright quasar without a massive host galaxy". Nature. 437 (7057): 381–384. arXiv:astro-ph/0509433. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..381M. doi:10.1038/nature04013. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16163349. S2CID 4303895.

- ^ a b Komossa, S.; Zhou, H.; Lu, H. (May 1, 2008). "A Recoiling Supermassive Black Hole in the Quasar SDSS J092712.65+294344.0?". The Astrophysical Journal. 678 (2): L81. arXiv:0804.4585. Bibcode:2008ApJ...678L..81K. doi:10.1086/588656. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 6860884.

- ^ Markakis, K.; Dierkes, J.; Eckart, A.; Nishiyama, S.; Britzen, S.; García-Marín, M.; Horrobin, M.; Muxlow, T.; Zensus, J. A. (August 1, 2015). "Subaru and e-Merlin observations of NGC 3718. Diaries of a supermassive black hole recoil?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 580: A11. arXiv:1504.03691. Bibcode:2015A&A...580A..11M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201425077. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 56022608.

- ^ Koss, Michael; Blecha, Laura; Mushotzky, Richard; Hung, Chao Ling; Veilleux, Sylvain; Trakhtenbrot, Benny; Schawinski, Kevin; Stern, Daniel; Smith, Nathan; Li, Yanxia; Man, Allison; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Mauerhan, Jon C.; Stanek, Kris; Sanders, David (November 1, 2014). "SDSS1133: an unusually persistent transient in a nearby dwarf galaxy". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 445 (1): 515–527. arXiv:1401.6798. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.445..515K. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1673. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Chiaberge, M.; Ely, J. C.; Meyer, E. T.; Georganopoulos, M.; Marinucci, A.; Bianchi, S.; Tremblay, G. R.; Hilbert, B.; Kotyla, J. P.; Capetti, A.; Baum, S. A.; Macchetto, F. D.; Miley, G.; O'Dea, C. P.; Perlman, E. S. (April 1, 2017). "The puzzling case of the radio-loud QSO 3C 186: a gravitational wave recoiling black hole in a young radio source?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 600: A57. arXiv:1611.05501. Bibcode:2017A&A...600A..57C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629522. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 27351189.

- ^ Jadhav, Yashashree; Robinson, Andrew; Almeyda, Triana; Curran, Rachel; Marconi, Alessandro (October 1, 2021). "The spatially offset quasar E1821+643: new evidence for gravitational recoil". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 507 (1): 484–495. arXiv:2107.14711. Bibcode:2021MNRAS.507..484J. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab2176. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Civano, F.; Elvis, M.; Lanzuisi, G.; Jahnke, K.; Zamorani, G.; Blecha, L.; Bongiorno, A.; Brusa, M.; Comastri, A.; Hao, H.; Leauthaud, A.; Loeb, A.; Mainieri, V.; Piconcelli, E.; Salvato, M. (July 1, 2010). "A Runaway Black Hole in COSMOS: Gravitational Wave or Slingshot Recoil?". The Astrophysical Journal. 717 (1): 209–222. arXiv:1003.0020. Bibcode:2010ApJ...717..209C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/717/1/209. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 20466072.

- ^ a b van Dokkum, Pieter; Pasha, Imad; Buzzo, Maria Luisa; LaMassa, Stephanie; Shen, Zili; Keim, Michael A.; Abraham, Roberto; Conroy, Charlie; Danieli, Shany; Mitra, Kaustav; Nagai, Daisuke; Natarajan, Priyamvada; Romanowsky, Aaron J.; Tremblay, Grant; Urry, C. Megan; van den Bosch, Frank C. (March 2023). "A candidate runaway supermassive black hole identified by shocks and star formation in its wake". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 946 (2): L50. arXiv:2302.04888. Bibcode:2023ApJ...946L..50V. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acba86. S2CID 256808376.

- ^ Japelj, Jure (February 22, 2023). "Have Scientists Found a Rogue Supermassive Black Hole?".

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (March 10, 2023). "A runaway black hole has been spotted fleeing a distant galaxy".

- ^ Page, Don N. (1976). "Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole". Physical Review D. 13 (2): 198–206. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..13..198P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198.특히 식 (27)을 Page, Don N. (1976). "Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole". Physical Review D. 13 (2): 198–206. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..13..198P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198.참조합니다.

- ^ a b Straub, O.; Vincent, F. H.; Abramowicz, M. A.; Gourgoulhon, E.; Paumard, T. (2012). "Modelling the black hole silhouette in Sgr A* with ion tori". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: A83. arXiv:1203.2618. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219209.

- ^ Eisenhauer, F.; et al. (2005). "SINFONI in the Galactic Center: Young Stars and Infrared Flares in the Central Light-Month". The Astrophysical Journal. 628 (1): 246–259. arXiv:astro-ph/0502129. Bibcode:2005ApJ...628..246E. doi:10.1086/430667. S2CID 122485461.

- ^ Henderson, Mark (December 9, 2008). "Astronomers confirm black hole at the heart of the Milky Way". The Times. London. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- ^ Schödel, R.; et al. (October 17, 2002). "A star in a 15.2-year orbit around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way". Nature. 419 (6908): 694–696. arXiv:astro-ph/0210426. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..694S. doi:10.1038/nature01121. PMID 12384690. S2CID 4302128.

- ^ Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration; et al. (2022). "First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 930 (2): L12. Bibcode:2022ApJ...930L..12E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6674. hdl:10261/278882. S2CID 248744791.

- ^ a b Ghez, A. M.; Salim, S.; Hornstein, S. D.; Tanner, A.; Lu, J. R.; Morris, M.; Becklin, E. E.; Duchêne, G. (May 2005). "Stellar Orbits around the Galactic Center Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal. 620 (2): 744–757. arXiv:astro-ph/0306130. Bibcode:2005ApJ...620..744G. doi:10.1086/427175. S2CID 8656531.

- ^ Gravity Collaboration; et al. (October 2018). "Detection of orbital motions near the last stable circular orbit of the massive black hole SgrA*". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 618: 15. arXiv:1810.12641. Bibcode:2018A&A...618L..10G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834294. S2CID 53613305. L10.

- ^ a b Chou, Felicia; Anderson, Janet; Watzke, Megan (January 5, 2015). "Release 15-001 – NASA's Chandra Detects Record-Breaking Outburst from Milky Way's Black Hole". NASA. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "Chandra :: Photo Album :: RX J1242-11 :: 18 Feb 04". chandra.harvard.edu.

- ^ a b Merritt, David (2013). Dynamics and Evolution of Galactic Nuclei. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780691158600.

- ^ a b King, Andrew (September 15, 2003). "Black Holes, Galaxy Formation, and the MBH-σ Relation". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 596 (1): L27–L29. arXiv:astro-ph/0308342. Bibcode:2003ApJ...596L..27K. doi:10.1086/379143. S2CID 9507887.

- ^ Ferrarese, Laura; Merritt, David (August 10, 2000). "A Fundamental Relation between Supermassive Black Holes and Their Host Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 539 (1): L9–12. arXiv:astro-ph/0006053. Bibcode:2000ApJ...539L...9F. doi:10.1086/312838. S2CID 6508110.

- ^ "Astronomers catch first glimpse of star being consumed by black hole". The Sydney Morning Herald. August 26, 2011.

- ^ Burrows, D. N.; Kennea, J. A.; Ghisellini, G.; Mangano, V.; et al. (August 2011). "Relativistic jet activity from the tidal disruption of a star by a massive black hole". Nature. 476 (7361): 421–424. arXiv:1104.4787. Bibcode:2011Natur.476..421B. doi:10.1038/nature10374. PMID 21866154. S2CID 4369797.

- ^ Zauderer, B. A.; Berger, E.; Soderberg, A. M.; Loeb, A.; et al. (August 2011). "Birth of a relativistic outflow in the unusual γ-ray transient Swift J164449.3+573451". Nature. 476 (7361): 425–428. arXiv:1106.3568. Bibcode:2011Natur.476..425Z. doi:10.1038/nature10366. PMID 21866155. S2CID 205226085.

- ^ Al-Baidhany, Ismaeel A.; Chiad, Sami S.; Jabbar, Wasmaa A.; Al-Kadumi, Ahmed K.; Habubi, Nadir F.; Mansour, Hazim L. (2020). "Determine the mass of supermassive black hole in the centre of M31 in different methods". International Conference of Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics Icnaam 2019. Vol. 2293. p. 050050. doi:10.1063/5.0027838. S2CID 230970967.

- ^ The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (April 10, 2019). "First M87 Event Horizon Telescope results. VI. The shadow and mass of the central black hole" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 875 (1): L6. arXiv:1906.11243. Bibcode:2019ApJ...875L...6E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab1141. S2CID 145969867.

- ^ Dullo, B.T. (November 22, 2019). "The Most Massive Galaxies with Large Depleted Cores: Structural Parameter Relations and Black Hole Masses". The Astrophysical Journal. 886 (2): 80. arXiv:1910.10240. Bibcode:2019ApJ...886...80D. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab4d4f. S2CID 204838306.

- ^ Shemmer, O.; Netzer, H.; Maiolino, R.; Oliva, E.; Croom, S.; Corbett, E.; di Fabrizio, L. (2004). "Near-Infrared Spectroscopy of High-Redshift Active Galactic Nuclei. I. A Metallicity-Accretion Rate Relationship". The Astrophysical Journal. 614 (2): 547–557. arXiv:astro-ph/0406559. Bibcode:2004ApJ...614..547S. doi:10.1086/423607. S2CID 119010341.

- ^ Saturni, F. G.; Trevese, D.; Vagnetti, F.; Perna, M.; Dadina, M. (2016). "A multi-epoch spectroscopic study of the BAL quasar APM 08279+5255. II. Emission- and absorption-line variability time lags". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 587: A43. arXiv:1512.03195. Bibcode:2016A&A...587A..43S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527152. S2CID 118548618.

- ^ Christopher A Onken; Fuyan Bian; Xiaohui Fan; Feige Wang; Christian Wolf; Jinyi Yang (August 2020), "thirty-four billion solar mass black hole in SMSS J2157–3602, the most luminous known quasar", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 496 (2): 2309, arXiv:2005.06868, Bibcode:2020MNRAS.496.2309O, doi:10.1093/mnras/staa1635

- ^ Major, Jason (October 3, 2012). "Watch what happens when two supermassive black holes collide". Universe today. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Merritt, D.; Milosavljevic, M. (2005). "Massive Black Hole Binary Evolution". Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Shiga, David (January 10, 2008). "Biggest black hole in the cosmos discovered". New Scientist.

- ^ Valtonen, M. J.; Ciprini, S.; Lehto, H. J. (2012). "On the masses of OJ287 black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 427 (1): 77–83. arXiv:1208.0906. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.427...77V. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21861.x. S2CID 118483466.

- ^ Kaufman, Rachel (January 10, 2011). "Huge Black Hole Found in Dwarf Galaxy". National Geographic. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ van den Bosch, Remco C. E.; Gebhardt, Karl; Gültekin, Kayhan; van de Ven, Glenn; van der Wel, Arjen; Walsh, Jonelle L. (2012). "An over-massive black hole in the compact lenticular galaxy NGC 1277". Nature. 491 (7426): 729–731. arXiv:1211.6429. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..729V. doi:10.1038/nature11592. PMID 23192149. S2CID 205231230.

- ^ Emsellem, Eric (2013). "Is the black hole in NGC 1277 really overmassive?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 433 (3): 1862–1870. arXiv:1305.3630. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.433.1862E. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt840. S2CID 54011632.

- ^ Reynolds, Christopher (2013). "Astrophysics: Black holes in a spin". Nature. 494 (7438): 432–433. Bibcode:2013Natur.494..432R. doi:10.1038/494432a. PMID 23446411. S2CID 205076505.

- ^ Prostak, Sergio (February 28, 2013). "Astronomers: Supermassive Black Hole in NGC 1365 Spins at Nearly Light-Speed". Sci-News.com. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Gültekin, Kayhan; Burke-Spolaor, Sarah; Lauer, Tod R.; w. Lazio, T. Joseph; Moustakas, Leonidas A.; Ogle, Patrick; Postman, Marc (2021). "Chandra Observations of Abell 2261 Brightest Cluster Galaxy, a Candidate Host to a Recoiling Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal. 906 (1): 48. arXiv:2010.13980. Bibcode:2021ApJ...906...48G. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/abc483. S2CID 225075966.

- ^ Bañados, Eduardo; et al. (December 6, 2017). "An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5". Nature. 553 (7689): 473–476. arXiv:1712.01860. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..473B. doi:10.1038/nature25180. PMID 29211709. S2CID 205263326.

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth; Bañados, Eduardo (December 6, 2017). "Found: Most Distant Black Hole". NASA. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (December 6, 2017). "Oldest Monster Black Hole Ever Found Is 800 Million Times More Massive Than the Sun". Space.com. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (March 6, 2020). "This Black Hole Blew a Hole in the Cosmos – The galaxy cluster Ophiuchus was doing just fine until WISEA J171227.81-232210.7 — a black hole several billion times as massive as our sun — burped on it". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "Biggest cosmic explosion ever detected left huge dent in space". The Guardian. February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "Astronomers detect biggest explosion in the history of the Universe". Science Daily. February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Giacintucci, S.; Markevitch, M.; Johnston-Hollitt, M.; Wik, D. R.; Wang, Q. H. S.; Clarke, T. E. (February 27, 2020). "Discovery of a giant radio fossil in the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 891 (1): 1. arXiv:2002.01291. Bibcode:2020ApJ...891....1G. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab6a9d. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 211020555.

- ^ "Biggest cosmic explosion ever detected left huge dent in space". The Guardian. February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "Astronomers detect biggest explosion in the history of the Universe". Science Daily. February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (February 22, 2021). "The White Dots in This Image Are Not Stars or Galaxies. They're Black Holes". ScienceAlert. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

추가열람

- Fulvio Melia (2003). The Edge of Infinity. Supermassive Black Holes in the Universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81405-8. OL 22546388M.

- Carr, Bernard; Kühnel, Florian (2022). "Primordial black holes as dark matter candidates". SciPost Physics Lecture Notes. arXiv:2110.02821. doi:10.21468/SciPostPhysLectNotes.48. S2CID 238407875.

- Chakraborty, Amlan; Chanda, Prolay K.; Pandey, Kanhaiya Lal; Das, Subinoy (2022). "Formation and Abundance of Late-forming Primordial Black Holes as Dark Matter". The Astrophysical Journal. 932 (2): 119. arXiv:2204.09628. Bibcode:2022ApJ...932..119C. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac6ddd. S2CID 248266315.

- Ferrarese, Laura & Merritt, David (2002). "Supermassive Black Holes". Physics World. 15 (1): 41–46. arXiv:astro-ph/0206222. Bibcode:2002astro.ph..6222F. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/15/6/43. S2CID 5266031.

- Krolik, Julian (1999). Active Galactic Nuclei. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01151-6. OL 361705M.

- Merritt, David (2013). Dynamics and Evolution of Galactic Nuclei. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12101-7.

- Dotan, Calanit; Rossi, Elena M.; Shaviv, Nir J. (2011). "A lower limit on the halo mass to form supermassive black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 417 (4): 3035–3046. arXiv:1107.3562. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.417.3035D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19461.x. S2CID 54854781.

- Argüelles, Carlos R.; Díaz, Manuel I.; Krut, Andreas; Yunis, Rafael (2021). "On the formation and stability of fermionic dark matter haloes in a cosmological framework". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 502 (3): 4227–4246. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa3986.

- Fiacconi, Davide; Rossi, Elena M. (2017). "Light or heavy supermassive black hole seeds: The role of internal rotation in the fate of supermassive stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 464 (2): 2259–2269. arXiv:1604.03936. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2505.

- Davelaar, Jordy; Bronzwaer, Thomas; Kok, Daniel; Younsi, Ziri; Mościbrodzka, Monika; Falcke, Heino (2018). "Observing supermassive black holes in virtual reality". Computational Astrophysics and Cosmology. 5 (1): 1. Bibcode:2018ComAC...5....1D. doi:10.1186/s40668-018-0023-7.

외부 링크

- 블랙홀: 중력의 끊임없는 끌어당김 우주망원경과학연구소의 블랙홀 물리학과 천문학에 관한 대화형 멀티미디어 웹사이트

- 초대질량 블랙홀의 모습

- 초거대 블랙홀의 NASA 이미지

- 은하수 중심부에 있는 블랙홀

- 은하 블랙홀 주위를 도는 별들의 ESO 비디오 클립

- 2002년 10월 21일 17광시 ESO 이내로 거대 은하 중심 접근하는 항성 궤도

- UCLA Galactic Center Group의 이미지, 애니메이션 및 새로운 결과물

- 초거대 블랙홀에 대한 워싱턴 포스트의 기사

- 영상(2:46) – 은하수 중심부 거대 블랙홀 주위를 도는 별 시뮬레이션

- 영상(2:13) – 시뮬레이션을 통해 초거대 블랙홀 발견 (NASA, 2018년 10월 2일)

- 슈퍼에서 울트라로: 블랙홀은 얼마나 커질 수 있을까요?

- September 2020, Paul Sutter 29 (September 29, 2020). "Black holes so big we don't know how they form could be hiding in the universe". Space.com. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "Testing general relativity with a supermassive black hole".

- "Wandering Black Holes Center for Astrophysics".

- "Supermassive stars might be born in the chaos around supermassive black holes". May 10, 2021.