영 드라이아스

Younger Dryas

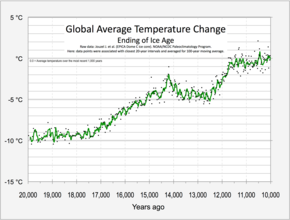

약 12,900년에서 11,700년 BP년 사이에 발생한 젊은 [2]드라이아스는 약 27,000년에서 20,000년 BP년까지 [3]지속된 마지막 빙하 최대 이후 점진적인 기후 온난화를 일시적으로 역전시킨 빙하 상태로 되돌아간 것입니다. 젊은 드라이아스는 기원전 2,580,000년에서 11,700년에 걸쳐 있었던 플라이스토세 시대의 마지막 단계였으며 현재의 따뜻한 홀로세 시대보다 앞서 있었습니다. 더 젊은 드라이아스는 지구의 기후를 온난화시키는 여러 방해물들 중에서 가장 심각하고 오래 지속되었으며, 그 이전에는 후기 빙하기 사이(Bölling–이라고도 함)가 있었습니다.Alerød interstadial), 14,670년부터 12,900년까지 지속된 상대적 온기의 간격.

그 변화는 비교적 갑작스러웠고, 수십 년에 걸쳐 일어났고, 그린란드의 온도가 4~10°C(7.2~18°F) 하락했고,[4] 온대 북반구의 대부분에서 빙하와 건조한 상태가 진전되었습니다. 그 원인에 대해 여러 이론이 제시되었고, 역사적으로 과학자들이 가장 지지하는 가설은 적도에서 북극으로 따뜻한 물을 운반하는 대서양 자오선 전복 순환이 북아메리카에서 대서양으로 신선한 차가운 물이 유입되면서 중단되었다는 것입니다.[5] 그러나 이 가설에는 몇 가지 문제가 존재하며, 그 중 하나는 녹은 물에 대한 명확한 지형학적 경로가 없다는 것입니다. 사실, 녹은 물 가설의 창시자 월리스 브로커(Wallace Broecker)는 2010년에 "영원한 드라이아스가 프로글래식 호수 아가시즈(Agassiz)에 저장된 물의 홍수로 인해 촉발된 일회성 이상 현상이라는 오랫동안 유지되어 온 시나리오는 경관의 정확한 시간과 장소에 명확한 지리적 서명이 없기 때문에 선호에서 떨어졌습니다."[6]라고 말했습니다. 최근에 화산 유발 요인이 제안되었으며,[7] 젊은 드라이아스가 시작되기 직전에 비정상적으로 높은 수준의 화산이 존재하는 것이 빙하 코어와[8] 동굴 퇴적물 모두에서 확인되었습니다.[9]

영 드라이아스는 전 세계적으로 똑같이 기후에 영향을 미치지 않았지만 전 세계 평균 기온은 급격하게 변했습니다. 예를 들어, 남반구와 북미 남동부와 같은 북반구의 일부 지역에서는 약간의 온난화가 발생했습니다.[10]

어린 드라이아스는 지표 속인 고산-툰드라 야생화 드라이아스 옥토페탈라의 이름을 따서 지어졌는데, 이는 잎이 스칸디나비아의 호수 퇴적물과 같이 후기 빙하, 종종 광산 생성이 풍부한 퇴적물에 풍부하기 때문입니다.

일반적인 설명 및 문맥

마지막 빙하기가 끝날 때 뚜렷한 한랭기가 존재한다는 것은 오래 전부터 알려져 왔습니다. 덴마크의 알레뢰드 점토 구덩이와 같이 스웨덴과 덴마크의 늪지와 호수에 대한 고생대학 및 석층학 연구가 젊은 드라이아스를 처음으로 인식하고 기술했습니다.[11][12][13][14]

The Young Dryas는 지난 16,000년 동안 일어난 일반적으로 갑작스러운 기후 변화로 인해 발생한 세 개의 경기장 중 가장 젊고 긴 경기장입니다.[15] 북유럽 기후 단계에 대한 블리트-세르난데르 분류에서 접두사 "Youngger"는 이 원래의 "Dryas" 기간이 더 따뜻한 단계인 Alerød 진동이 뒤따랐다는 것을 의미하며, 이는 다시 약 14,000년의 BP로 보정된 오래된 Dryas에 의해 선행되었습니다. 그것은 확실한 날짜가 아니며 추정치는 400년마다 다르지만 일반적으로 약 200년 동안 지속된 것으로 받아들여집니다. 북부 스코틀랜드의 빙하는 젊은 드라이아스기보다 더 두껍고 넓었습니다.[16] 올드 드라이아스는 또 다른 따뜻한 무대인 뵐링 진동이 뒤따랐고, 이 진동은 종종 가장 오래된 드라이아스로 알려진 세 번째이자 더 오래된 경기장과 분리되었습니다. 가장 오래된 드라이아스는 젊은 드라이아스보다 약 1,770년 전에 발생했으며 약 400년 동안 지속되었습니다. 그린란드의 GISP2 빙하 코어에 따르면, 가장 오래된 드라이아는 BP로 보정된 약 15,070년에서 14,670년 사이에 발생했습니다.[17]

아일랜드에서는 영 드라이아스가 나하나간 스타디알로도 알려져 있고, 영국에서는 로몬드 호수로 불렸습니다.[18][19] 그린란드 서밋 빙상 연대표에서 영 드라이아스는 그린란드 경기장 1(GS-1)에 해당합니다. 앞의 Alerød 웜 기간(Interstadial)은 Greenland Interstadial-1c~1a(GI-1c~GI-1a)의 세 가지 이벤트로 세분화됩니다.[20]

Young, Older, Older Dryas 외에도, Young Dryas와 갑작스러운 Young Dryas와 유사한 한 세기 동안의 추운 기후가 Bölling 진동과 Alerød 진동 사이스타디얼 모두에서 발생했습니다. 뵐링 진동 내에서 발생한 한랭 기간을 뵐링 내 한랭 기간이라고 하며, 알레뢰드 진동 내에서 발생한 한랭 기간을 알레뢰드 내 한랭 기간이라고 합니다. 두 추운 시기 모두 Old Dryas와 기간과 강도가 비슷하고 시작과 끝이 상당히 급작스럽습니다. 한랭기는 그린란드 빙하 코어, 유럽 라커스트린 퇴적물, 대서양 퇴적물, 베네수엘라 카리아코 분지의 고기후 기록에서 순서와 상대적인 크기로 인식되었습니다.[21][22]

오래된 젊은 드라이아스(Young Dryas)와 같은 사건의 예는 오래된 빙하기의 끝([a]종결이라고 함)에서 보고되었습니다. 호수와 해양 퇴적물에서 발견되는 온도에 민감한 지질인 긴 사슬 알케논은 과거 대륙 기후의 정량적 재구성을 위한 강력한 저온계로 잘 알려져 있습니다.[25][page needed] 오래된 빙하 터미네이션의 고해상도 고온도 재구성에 알케논 고온도계를 적용한 결과, 매우 유사한 젊은 드라이아스 유사 고기후 진동이 터미네이션 II 및 IV 동안 발생한 것으로 나타났습니다.[a] 그렇다면, 영 드라이아스는 종종 그렇게 여겨지는 것처럼 크기, 범위, 그리고 신속성 면에서 유일한 고기후 현상이 아닙니다.[25][26] 게다가, 고생물학자들과 제4기 지질학자들은 중국 후베이성 선농자 지역의 고고도 동굴의 석순에서 종결 III에 대한 중국 δO 기록에서 잘 표현된 영 드라이아스 사건을 발견했다고 보고했습니다. 빙하 코어, 심해 퇴적물, 스펠레오템, 대륙 고생물학 자료 및 황토의 다양한 고생물 기록은 지난 4개의 빙하기가 끝나는 동안 영 드라이아스 사건과 일치하는 유사한 갑작스러운 기후 사건을 보여줍니다(단스가드-외슈거 사건 참조). 그들은 젊은 드라이아스 사건이 빙하기 말에 발생하는 탈빙하의 본질적인 특징일 수 있다고 주장합니다.[27][28][29]

타이밍.

그린란드 빙심에서 나온 안정 동위원소 분석은 젊은 드라이아스의 시작과 끝에 대한 추정치를 제공합니다. 그린란드 빙상 프로젝트 2와 그린란드 빙상 프로젝트의 일환으로 그린란드 서밋 빙상을 분석한 결과, 영 드라이아스는 약 BP 12,800년 동안 얼음이 시작된 것으로 추정되었습니다. 석순에 대한 보다 최근의 연구는 12,870 ± 30년 BP의 시작일을 강력하게 시사하며,[30] 이는 보다 최근의 북그린란드 빙핵 프로젝트(NGRIP) 빙핵 데이터와 일치합니다.[30] 협의된 구체적인 빙핵 분석에 따르면, 영 드라이아스는 1,150년에서 1,300년 동안 지속된 것으로 추정됩니다.[11][12] GISP2 빙핵에서 산소 동위원소를 측정한 결과 영 드라이아스의 종말은 약 50년에 걸쳐 일어났음을 시사합니다.[31] 먼지 농도와 눈 축적과 같은 다른 대리 데이터는 30년 이하, 잠재적으로 20년 이하의 [32]속도로 지속되는 훨씬 더 빠른 전환을 시사합니다.[31] 그린란드는 불과 반세기 만에 약 7 °C (13 °F)의 온난화를 경험했습니다.[33] 그린란드의 총 온난화는 10 ± 4 °C (18 ± 7 °F)였습니다.[34]

젊은 드라이아스의 종말은 약 11,550년 전으로 거슬러 올라가며, 다양한 방법으로 "방사성 탄소 고원"인 10,000 BP (교정되지 않은 방사성 탄소 연도)에서 발생했으며, 대부분 일관된 결과를 가지고 있습니다.

몇년전에 장소 11500 ± 50 그린란드의[35] GRIP 아이스 코어 11530 + 40

− 60노르웨이[36] 서부 크라케네스 호수 11570 베네수엘라[37] 카리아코 분지 중심부 11570 독일 참나무와 소나무 덴드로[38] 연대학 11640 ± 280 GISP2 빙핵, 그린란드[39]

국제 층서 위원회는 그린란드 단계의 시작, 그리고 은연중에 영 드라이아스의 종말을 2000년 이전의 11,700년으로 설정했습니다.[40]

영 드라이아스의 시작은 북대서양 지역에 걸쳐 동시적인 것으로 간주되지만, 최근 연구에 따르면 영 드라이아스의 시작은 그 안에서도 시간 경과적일 수 있다고 결론지었습니다. Muschitiello와 Wohlfarth는 적층된 Varve 시퀀스를 조사한 후, Young Dryas의 시작을 정의하는 환경 변화가 위도에 따라 발생하는 시간이 매우 불규칙하다는 것을 발견했습니다. 변화에 따르면, 영 드라이아스는 일찍이 위도 56–54°N을 따라 12,900년에서 13,100년 전에 발생했습니다. 북쪽으로 더 나아가, 그들은 변화가 약 12,600년에서 12,750년 전에 일어났다는 것을 발견했습니다.[41]

일본 스이게쓰 호수의 다양한 퇴적물과 아시아의 다른 고환경 기록을 분석한 결과, 아시아와 북대서양 사이의 영 드라이아스의 시작과 끝에서 상당한 지연이 발생했다고 합니다. 예를 들어, 일본의 Suigets 호수의 퇴적물 코어에 대한 고환경 분석에 따르면 영 드라이아스의 온도는 북대서양 지역에서 약 12,900년의 BP 대신 12,300년에서 11,250년 사이에 2-4 °C의 온도 감소를 발견했습니다.

대조적으로, 50년 동안 유럽의 육상 거대 화석과 나무 고리에서 11,000년의 방사성 탄소 연대에서 10,700년–10,600년의 방사성 탄소 연대로 방사성 탄소 신호의 급격한 변화는 Suigets 호수의 갈변 퇴적물에서 동시에 발생했습니다. 그러나 이와 같은 방사성 탄소 신호의 변화는 수이게쓰 호수에서 영 드라이아스의 시작을 몇 백 년 전으로 앞당겼습니다. 중국인들의 자료를 해석한 결과, 영 드라이어스 동아시아는 북대서양 영 드라이어스보다 최소 200~300년 정도 늦게 냉각된 것으로 확인됐습니다. 데이터의 해석이 더 모호하고 모호하지만, 영 드라이아스의 종말과 홀로세 온난화의 시작은 일본과 동아시아의 다른 지역에서 비슷하게 지연되었을 가능성이 있습니다.[42]

마찬가지로 필리핀 팔라완의 푸에르토 프린세사 지하강 국립공원에 있는 동굴에서 자라는 석순을 분석한 결과 영 드라이아스의 발병도 지연된 것으로 나타났습니다. 석순에 기록된 대리 데이터에 따르면 영 드라이아스 가뭄 조건이 이 지역에서 완전한 범위에 도달하기 위해서는 550년 이상의 교정 기간이 필요했고, 종료된 후 영 드라이아스 이전 수준으로 복귀하기 위해서는 약 450년의 교정 기간이 필요했습니다.[43]

멕시코 만의 오르카 분지에서 플랑크톤 유공충 Globigerinoides ruber의 Mg/Ca 비율로 측정한 12,800에서 11,600 BP까지 지속된 약 2.4 ± 0.6°C의 해수면 온도 하락은 멕시코 만에서 영 드라이아스의 발생을 의미합니다.[44]

글로벌 효과

젊은 드라이아스는 전 세계적으로 거의 비슷한 수준이었습니다.[45] 그러나 전 세계 평균 표면 온도의 감소의 크기는 미미했습니다. 영 드라이아스는 빙하의 절정 상태로 전 세계적으로 재발하지 않았습니다.[46]

서유럽과 그린란드에서 영 드라이아스는 잘 정의된 동시성 서늘한 시기입니다.[47] 그러나 열대 북대서양에서의 냉각은 그보다 몇 백 년 앞서 왔을지도 모릅니다. 남아메리카는 덜 명확한 시작을 보여주지만 급격한 종료를 보여줍니다. 남극의 한랭 역전 현상은 영 드라이아보다 1천 년 전에 시작된 것으로 보이며, 명확하게 정의된 시작이나 끝이 없습니다. 피터 호이버스는 남극과 뉴질랜드 그리고 오세아니아의 일부 지역에 영 드라이아가 없는 것에 대해 공정한 확신이 있다고 주장했습니다.[48] 저위도 빙핵 기록은 일반적으로 그 기간 동안 독립적인 연대 측정이 부족하기 때문에 젊은 드라이아스에 대응하는 열대 기후인 탈석회 기후 역전(DCR)의 시기를 설정하기가 어렵습니다. 그 예로는 사자마 빙핵(볼리비아)이 있는데, 사자마 빙핵(DCR)의 시기는 GISP2 빙핵 기록(그린란드 중부)의 시기에 고정되어 있습니다. 그러나 DCR 동안 중부 안데스의 기후 변화는 중요했으며 훨씬 더 습하고 더 추운 조건으로 변화하는 것이 특징이었습니다.[49] 변화의 크기와 갑작스러운 변화는 저위도 기후가 YD/DCR 동안 수동적으로 반응하지 않았음을 시사합니다.

영 드라이아의 영향은 북미 전역에서 다양한 강도로 나타났습니다.[50] 북아메리카 서부에서는 유럽이나 북아메리카 북동부보다 그 영향이 덜 강했습니다.[51] 그러나 빙하가[52] 재진전했다는 증거는 태평양 북서쪽에서 영 드라이아스 냉각이 일어났음을 나타냅니다. 오리건 남부의 클라마스 산맥에 있는 오리건 동굴 국립 기념물과 보호 구역의 스펠레오템은 젊은 드라이아스와 동시에 기후 냉각의 증거를 제공합니다.[53]

기타 기능에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 스칸디나비아의 숲을 빙하 툰드라로 대체 (Dryas octopetala 식물의 서식지)

- 전 세계 산맥의 빙하나 눈 증가

- 북유럽의 용질유인력층 및 황토 퇴적물 형성

- 아시아 사막에서 발원한 대기 중 먼지가 많아짐

- 나투피안 사냥꾼들이 레반트에 영구적인 정착지를 수집했다는 증거의 감소, 더 이동적인 삶의[54] 방식으로의 복귀를 암시합니다.

- 남반구의 Huelmo-Mascardi Cold Reverse는 같은 시기에 끝났습니다.

- 클로비스 문화의 쇠퇴: 영건기 동안의 디어 울프, 카멜롭스, 그리고 다른 란촐라브레인 메가파우나뿐만 아니라 콜롬비아 매머드와 같은 많은 종들의 멸종의 확실한 원인은 밝혀지지 않았지만, 기후 변화와 인간 사냥 활동이 주요 원인으로 제시되었습니다.[55] 최근에, 이 거대 동물들은 1000년 전에 무너졌다는 것이 발견되었습니다.[56]

북아메리카

그린란드

추운 조건에도 불구하고, 그린란드 북부의 일부 지역 빙하를 제외하고,[57] 영 드라이아스 동안 그린란드 빙하는 후퇴했습니다.[58] 이는 대서양 자오선 전복 순환(AMOC)의 약화 때문일 가능성이 큽니다.[57]

동쪽

영 드라이아스는 갑작스러운 기후 변화에 대한 생물군의 반응과 인간이 그러한 급격한 변화에 어떻게 대처했는지에 대한 연구에 중요한 시기입니다.[59] 북대서양의 갑작스러운 냉각의 영향은 북미에서 강력한 지역적 효과를 가져 어떤 지역은 다른 지역보다 더 급격한 변화를 겪었습니다.[60] BP 13,300에서 13,000 cal년 사이의 영 드라이아스로의 전환에 수반되는 냉각 및 얼음의 전진이 뉴욕주 서부의 4개 지역에서 많은 방사성 탄소 연대와 함께 확인되었습니다. 진보는 위스콘신의 투 크릭 숲 침대와 비슷한 나이입니다.[61]

영 드라이어스 냉각의 영향은 영 드라이어스 크로노존의 시작과 끝에 현재의 미국의 나머지 지역보다 더 빠르게 뉴잉글랜드와 캐나다 해상의 일부 지역에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[62][63][64][65] 대리 지표들은 메인 주의 여름 기온 조건이 최대 7.5 °C 감소했음을 보여줍니다. 추운 겨울과 낮은 강수량과 함께 시원한 여름은 북방림이 북쪽으로 이동한 홀로세가 시작될 때까지 나무가 없는 툰드라를 낳았습니다.[66]

대서양을 향해 동쪽으로 향한 중앙 애팔래치아 산맥의 식생은 가문비나무(Picea spp.)와 타마락(Larix laricina) 북방림에 의해 지배되었고, 후에 영 드라이아스 시대 말에 온대, 더 넓은 잎의 나무 숲 상태로 빠르게 변했습니다.[67][68] 반대로 온타리오 호수 근처에서 나온 꽃가루와 거대화석의 증거는 홀로세 초기까지 시원하고 북방림이 지속되었음을 나타냅니다.[68] 애팔래치아 산맥의 서쪽, 오하이오 강 계곡과 남쪽에서 플로리다까지 급속한 기후 변화의 결과로 유사 식물 반응이 없는 것으로 보이지만 이 지역은 경목림이 우세한 등 대체로 서늘한 상태를 유지했습니다.[67] 영 드라이아스기에 미국 남동부는 약해진 AMOC로 인한 북대서양 환류의 카리브해 지역의 열기로 인해 플라이스토세[68][60][69] 동안 지역보다 따뜻하고 비가 많이 내렸습니다.[70]

중앙의

또한, 오대호 지역 남쪽에서 텍사스와 루이지애나까지 변화하는 효과의 기울기가 발생했습니다. 기후적 강제력은 북동쪽에서와 마찬가지로 미국 내륙의 북쪽으로 찬 공기를 이동시켰습니다.[71][72] 동부 해안 지대에서 볼 수 있는 것처럼 급격한 묘사는 없었지만, 중서부는 멕시코 만의 따뜻한 기후적 영향으로 인해 남쪽보다 북쪽 내륙에서 훨씬 더 추웠습니다.[60][73] 북쪽에서는 로랑라이드 빙상이 젊은 드라이아스기에 재진입하여 서수피리어호에서 남동쪽 퀘벡까지 모레인이 퇴적되었습니다.[74] 오대호의 남쪽 가장자리를 따라 가문비나무는 빠르게 감소한 반면 소나무는 증가했으며 초본 대초원 식생은 풍부하게 감소했지만 지역 서쪽에서 증가했습니다.[75][72]

로키 산맥

로키마운틴 지역의 효과는 다양했습니다.[76][77] 북부 로키스에서는 소나무와 전나무의 현저한 증가는 이전보다 따뜻한 상태와 군데군데 아고산 공원지대로의 이동을 시사합니다.[78][79][80][81] 그것은 제트기류가 북상하면서 여름 일사량이[78][82] 증가하고 오늘보다 더 높은 겨울 눈 뭉치가 결합되어 봄 시즌이 길어지고 습해졌기 때문으로 추정됩니다.[83] 특히 북부 산맥에서 약간의 빙하 재진전이 있었지만 [84][85]로키 산맥의 몇몇 지역은 영 드라이아스 동안 식생의 변화가 거의 또는 전혀 없음을 보여줍니다.[79] 증거는 또한 텍사스에 영향을 주었던 같은 걸프 지역의 상황 때문에 뉴멕시코의 강수량이 증가했음을 나타냅니다.[86]

서쪽

태평양 북서부 지역은 2~3℃의 냉각과 강수량 증가를 경험했습니다.[87][69][88][89][90][91] Cascade Range 뿐만 아니라 British Columbia에서도[92][93] 빙하 재진입이 기록되었습니다.[94] 소나무 꽃가루의 증가는 중앙 캐스케이드 지역의 겨울이 더 시원하다는 것을 나타냅니다.[95] 올림픽 반도의 중간 고도 지역에서는 화재가 감소했지만, 영 드라이아스 동안 숲이 지속되고 침식이 증가하여 시원하고 습한 상태임을 시사합니다.[96] 스펠레오템 기록에 따르면 오리건 남부의 강수량이 증가했으며,[90][97] 그 시기는 북부 대분지의 충적 호수의 크기가 증가한 시기와 일치합니다.[98] 시스키요우 산맥의 꽃가루 기록은 영 드라이아스의 시기가 늦다는 것을 암시하는데, 이는 따뜻한 태평양 조건이 그 범위에 더 큰 영향을 미친다는 것을 나타내지만,[99] 꽃가루 기록은 앞서 언급한 스펠레오테 기록보다 연대순으로 덜 제한적입니다. 남서쪽은 평균 2℃의 냉각과 함께 강수량이 증가한 것으로 보입니다.[100]

유럽

1916년부터 꽃가루 분석 기법의 시작과 그에 따른 정제, 그리고 꾸준히 증가하는 꽃가루 도표의 수, 병리학자들은 젊은 드라이아스가 종종 드라이아스 옥토페탈라를 포함하는 빙하 식물의 연속인 일반적으로 추운 기후의 식물로 대체되는 동안 유럽의 대부분 지역에서 뚜렷한 식생 변화 시기였다고 결론지었습니다.[101] 식생의 급격한 변화는 일반적으로 급격하게 북상하던 산림 식생에 불리한 (연간) 기온의 급격한 감소의 영향으로 해석됩니다. 이 냉각은 추위에 강하고 빛을 필요로 하는 식물과 관련 스텝 동물군의 확장을 선호했을 뿐만 아니라 스칸디나비아의 지역적인 빙하 발전과 지역적인 설선의 감소로 이어졌습니다.[11]

북반구 고위도 지역에서 영 드라이아스가 시작될 때 12,900년에서 11,500년 사이의 빙하 상태 변화는 상당히 갑작스러웠다고 주장되어 왔습니다.[32] 그것은 이전의 Old Dryas interstadial의 온난화와 극명한 대조를 이룹니다. 그 종말은 10년 정도의 기간에 걸쳐 발생한 것으로 추론되어 왔지만,[31] 그 발병은 더 빨랐을 수도 있습니다.[102] 그린란드 빙핵 GISP2의 열분획 질소 및 아르곤 동위원소 데이터에 따르면, 그린란드 빙핵 GISP2의 정상은 오늘날보다 젊은 드라이아스기에[32][103] 약 15 °C (27 °F) 더 추웠습니다.

영국의 연평균 기온은 영구 동토층이 있는 것에서 알 수 있듯이 -1 °C(-1.8 °F)를 [39]넘지 않았으며 딱정벌레 화석 증거에 따르면 연평균 기온은 -5 °C(23 °[103]F)까지 떨어졌으며 저지대에서는 빙하와 빙하가 형성되었습니다.[104] 계절성에 대한 해빙의 영향은 스코틀랜드의 예외적인 건조를 촉진했습니다.[105] 급격한 기후 변화의 시기적 크기, 정도, 속도 중 어느 것도 그 이후에 경험된 바가 없습니다.[32]

지금의 헤세에서는 영 드라이아스 초기에 다채널 땋은 평원이 개발되었습니다. 후대의 Young Dryas 동안, 이 땋은 평원은 Alerød 진동 동안의 일반적인 것과 유사한 직선적이고 구불구불한 강으로 이루어진 충적층으로 되돌아갔습니다.[106]

디나릭 알프스에서는 다양한 측면 및 말단 모레인이 젊은 드라이아스 및 관련 빙하의 부활 동안 형성된 것으로 날짜가 지정되었습니다.[107] 자블라니카 산맥의 증거는 건조함이 영 드라이아스의 추운 온도에도 불구하고 계속되는 빙하 후퇴를 촉진했음을 나타냅니다.[108]

중동

아나톨리아는 젊은 드라이아스기에 매우 건조했습니다.[109][110] 젊은 드라이아스의 종착점에 있는 Gobecli Tepe 주변에서는 지형역학적 활동의 강화는 발생하지 않았습니다.[111]

동아시아

중국 산시성에 있는 공하이 호수의 꽃가루 기록은 영 드라이아스의 시작과 동시에 건조함이 크게 증가했음을 보여주는데, 일부 학자들은 약화된 동아시아 여름 몬순의 결과로 믿고 있습니다.[112] 그러나 일부 연구는 영 드라이아스 동안 EASM이 오히려 강화되었다고 결론지었습니다.[113]

농업에 미치는 영향

젊은 드라이아스는 종종 신석기 혁명과 관련이 있으며 레반트에서 농업을 채택했습니다.[114][115] 춥고 건조한 영 드라이아스는 의심할 여지 없이 이 지역의 운반 능력을 떨어뜨렸고, 초기 나투피아 인구를 더 이동성 있는 생활 패턴으로 내몰았습니다. 추가적인 기후 악화는 곡물 재배를 가져온 것으로 생각됩니다. Natufian 시대의 변화하는 생계 패턴에서 Young Dryas의 역할에 대한 상대적인 합의가 존재하지만, 이 시기의 말기 농업 시작과의 연관성은 여전히 논의되고 있습니다.[116][117]

해수면

산호초의 수많은 깊은 코어 분석으로 구성된 확고한 지질학적 증거를 기반으로 빙하기 이후 해수면 상승 속도의 변화가 재구성되었습니다. 탈석회와 관련된 해수면 상승의 초기 부분에서, 멜트워터 펄스라고 불리는 해수면 상승의 세 가지 주요 기간이 발생했습니다. 그들은 흔히 말합니다.

- 19,000~19,500년 전에 보정된 펄스에 대한 용융수 펄스 1A0;

- 14,600~14,300년 전에 보정된 펄스에 대한 용융수 펄스 1A;

- 11,400~11,100년 전에 보정된 펄스에 대한 용융수 펄스 1B.

젊은 드라이아스는 약 290년 동안 13.5m 상승한 용융수 펄스 1A 이후에 발생했으며, 약 14,200년 전에 중심이 되었고, 용융수 펄스 1B 이전에는 약 160년 동안 7.5m 상승했으며, 약 11,000년 전에 중심이 되었습니다.[118][119][120] 마지막으로, Young Dryas는 모든 용융수 펄스 1A와 모든 용융수 펄스 1B를 모두 후기로 했을 뿐만 아니라, 그 직전과 직후의 기간에 비해 해수면 상승률이 크게 감소한 기간이었습니다.[118][121]

Young Dryas의 시작에 대해 단기적인 해수면 변화의 가능한 증거가 보고되었습니다. 첫째, 바드와 다른 사람들의 데이터 도표는 젊은 드라이아스의 시작 근처 해수면에서 6m 미만의 작은 낙하를 시사합니다. 바베이도스와 타히티의 데이터에서 볼 수 있는 해수면 상승 변화율에 상응하는 변화가 있을 수 있습니다. 이러한 변화가 "접근 방식의 전반적인 불확실성 내"에 있다는 점을 감안할 때, 큰 가속 없이 비교적 부드러운 해수면 상승이 그때 발생했다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[121] 마지막으로, 노르웨이 서부의 Lohe와 다른 사람들의 연구에 따르면, 수년 전 13,640개의 해수면 저위대가 보정되었고, 13,080개의 보정된 상태에서 시작된 이후의 Young Dryas 변환이 보고되었습니다.[122] 그들은 Alerød의 낮은 지대의 시기와 그에 따른 변형은 지각의 지역적 하중 증가의 결과이며, 지오이드 변화는 팽창하는 빙상에 의해 야기되었으며,[123] 이 빙상은 약 13,600년 전에 보정된 Alerød 초기에 성장하고 발전하기 시작했으며, 이는 Young Dryas가 시작되기 훨씬 전에 발생했습니다.[122]

해양순환

Young Dryas는 바다 밑바닥 물의 환기를 감소시켰습니다. 서부 아열대 북대서양의 코어는 그곳의 바닥수의 환기 나이가 약 1,000년으로, 약 1,500 BP 정도의 같은 장소에서 나온 후기 홀로세 바닥수의 두 배임을 보여줍니다.[124]

원인

영 드라이아는 역사적으로 따뜻한 열대 해역을 북쪽으로 순환하는 북대서양 "컨베이어"의 현저한 감소 또는 폐쇄로 인해 발생한 것으로 여겨져 왔는데, 이는 북아메리카의 탈백산과 아가시즈 호수의 담수가 갑자기 유입되었기 때문입니다. 그러한 사건에[125] 대한 지질학적 증거의 부족은 더 많은 탐사를 자극했지만, 정확한 담수의 원천에 대한 합의는 존재하지 않으며, 사실 최근 담수 펄스 가설이 의문시되고 있습니다.[6] 원래 담수 경로는 세인트 로렌스 수로로 여겨졌지만,[125] 이 경로에 대한 증거가 부족하여 연구자들은 매켄지 강을 따라 흐르는 경로,[126][127][128] 스칸디나비아에서 나오는 탈빙수,[129] 해빙의 융해,[130] 강우량 증가,[131] 또는 북대서양[132] 전체의 강설량 증가. 그러면 지구의 기후는 동파로 인해 북대서양에서 민물 "뚜껑"이 제거될 때까지 새로운 상태에 갇히게 될 것입니다. 그러나 시뮬레이션에 따르면 한 번의 홍수로 인해 새로운 상태가 1,000년 동안 잠겨 있을 가능성이 없다고 합니다. 홍수가 멈추면, AMOC는 복구될 것이고 영 드라이아스는 100년 이내에 멈출 것입니다. 따라서 1,000년 이상 약한 AMOC를 유지하기 위해서는 지속적인 담수 투입이 필요할 것입니다. 2018년 연구에 따르면 강설은 AMOC의 약화 상태를 장기화하는 지속적인 담수의 원천이 될 수 있다고 제안했습니다.[132] 영 드라이아스 동안 해수면 상승에 대한 증거 부족과 함께 담수의 기원에 대한 합의 부족은 영 드라이아스가 홍수로 인해 촉발되었다는 모든 가설에서 문제가 됩니다.[133][6][7]

영 드라이아스는 지난 12만 년 동안 25개 또는 26개의 주요 기후 에피소드(Dansgaard-Oeschger 사건, 또는 D-O 사건) 중 마지막에 불과하다는 것이 종종 언급됩니다. 이 에피소드들은 갑작스러운 시작과 끝으로 특징지어집니다(몇 십 년 또는 몇 세기의 시간 단위로 변화가 발생합니다).[134][135] 영 드라이아스는 가장 최근의 것이기 때문에 가장 잘 알려져 있고 가장 잘 알려져 있지만, 근본적으로 지난 12만 년 동안의 이전의 한랭기와 유사합니다.[136] 영 드라이아스가 녹은 물 펄스에 의해 발생했다고 생각되지 않는 이전의 한랭 단계와 구조가 매우 유사하다는 사실에 근거하여, 영 드라이아스의 원인을 이해하는 것은 "녹은 물 가설에[136] 의존하기보다는 D-O 사건을 설명하는 데 사용되는 메커니즘을 조사하는 데 도움이 될 것"이라고 주장되어 왔습니다.

또 다른 아이디어는 태양 플레어가 영 드라이아스와 거의 같은 시기에 일어난 거대 동물 멸종의 원인일 수 있지만, 그렇다고 모든 대륙에 걸쳐 멸종 시기의 명백한 변동성을 설명할 수는 없다는 것입니다.[137][138] 영 드라이아스 충돌 가설은 냉각이 붕괴하는 혜성이나 소행성의 충격 때문이라고 주장하지만, 대부분의[139] 전문가들은 이 아이디어를 거부하고 있습니다.[140]

멜트워터 트리거에 대해 점점 더 지지를 받고 있는 대안은 젊은 드라이아스가 화산 활동에 의해 촉발되었다는 것입니다. 현재 수많은 논문들이 화산 활동을 지난 2천[141] 년과 홀로세에 걸친 다양한 추운 사건들과 자신 있게 연결하고 있으며,[142] 특히 화산 폭발이 수 세기에서 수 천 년 동안 지속되는 기후 변화를 촉발하는 능력에 주목하고 있습니다.[143][144] 고위도 화산 폭발은 북대서양 해빙 성장을 증가시키고 AMOC를 늦출 수 있을 정도로 대기 순환을 충분히 이동시켜 결과적으로 긍정적인 냉각 피드백을 이끌어 영 드라이아스(Young Dryas)를 시작할 수 있었다고 제안되었습니다.[7] 이러한 관점은 현재 동굴 퇴적물과[9] 빙하 코어 모두에서 젊은 드라이아스의 시작과 일치하는 화산 활동에 대한 증거에 의해 뒷받침됩니다.[8] 특히 그린란드 빙핵에서 나온 유황 자료는 영 드라이아스 화산이 시작되기 직전의 분화군과 관련된 복사력이 "공통시대 화산활동이 가장 활발했던 시기를 능가한다"는 것을 보여줍니다. 화산의[8] 영향으로 인해 눈에 띄는 다단계 규모의 냉각을 경험했습니다." 특히 유황 데이터는 12,870년 전 북반구에서 매우 크고 고위도 지역에서 분화가 일어났음을 강력하게 시사하며,[8] 이는 석순에서 파생된 영 드라이아스 사건의 시작과 구별할 수 없는 날짜입니다.[30] 어떤 폭발이 이 유황 스파이크의 원인이었는지는 불분명하지만, 그 특징은 라허 화산 폭발을 근원으로 보는 것과 일치합니다. 이 폭발은 독일[145] 호수의 퇴적물을 바베이트로 계산하여 12,880 ± 40년 BP로, Ar/39Ar 연대 측정으로 12,900 ± 560년으로 추정되었으며,[146] 둘 다 12,870년 BP에서 황 스파이크의 불확실성과 일치하며, 라허 시 폭발을 젊은 드라이아스의 가능한 계기로 만들었습니다. 그러나 새로운 방사성 탄소 연대는 이전의 라허 시 폭발 연대에 도전하여 13,006년 BP로 거슬러 올라가지만,[147] 이 연대 자체는 설명되지 않고 이전보다 더 오래된 것처럼 보이는 방사성 탄소 '죽은' 마그마틱 이산화탄소의 영향을 받을 가능성이 있기 때문에 도전을 받았습니다.[148] Laacher See 분화 날짜를 둘러싼 모호성과 상관없이, 그것은 Young Dryas 사건[7][148] 직전 또는 사건 이전 ~100년 동안 군집했던 여러 폭발 중 하나로 상당한 냉각을 일으켰습니다.[8]

Young Dryas 사건의 화산 계기도 사건 초기에 해수면 변화가 거의 없었던 이유를 설명해 줍니다.[133] 또한 화산 활동과 D-O 사건을[149][150] 연계한 이전 연구와 영 드라이아스가 단순히 가장 최근의 D-O 사건이라는 관점과도 일치합니다.[136] 제안된 Young Dryas 트리거 중 화산 트리거는 트리거의 실제 발생을 반영하는 것으로 거의 보편적으로 받아들여지는 증거를 가진 유일한 것이라는 점에 주목할 필요가 있습니다. 융해물 펄스가 발생했다는 것, 또는 영 드라이아스 이전에 대담한 충격이 발생했다는 것에 대해서는 의견이 일치하지 않는 반면, 영 드라이아스 이전에 비정상적으로 강한 화산 활동이 있었다는 증거는 현재 매우 강력합니다.[7][8][9][148] 짧은 기간의 화산 활동이 1,300년의 냉각을 유발할 수 있는지, 배경 기후 조건이 화산에 대한 기후 반응에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 등이 미해결 문제입니다.

젊은 드라이아스의 종말

젊은 드라이아스의 종말은 이산화탄소 수치의 증가와 대서양 경락 뒤집기 순환의 변화로 인해 발생했습니다. 증거에 따르면 마지막 빙하 최대치와 홀로세 사이의 기온 상승은 대부분 가장 오래된 드라이아스와 젊은 드라이아스의 직후에 일어났으며, 가장 오래된 드라이아스와 젊은 드라이아스 기간과 뵐링-알레뢰드 온난화 기간 동안 지구 기온의 변화는 상대적으로 거의 없었습니다.[151]

참고 항목

- 8.2 킬로년 전 기후 현상 – 약 8,200년 전의 급속한 지구 냉각

- 전단지 진동 - 전단지 내 냉각 에피소드

- 하인리히 사건 – 거대한 빙산 무리들이 북대서양을 횡단합니다.

- 소빙하기 – 중세 온난기(16-19세기) 이후의 기후 냉각

- 중세 온난기 – 북대서양 지역의 온난한 기후가 950년부터 1250년까지 지속된 시기

- 신석회

- 빙하기 연대 – 지구의 주요 빙하기 연대표

- 환경사 연표

- 보퍼트 자이레 역전

각주

참고문헌

- ^ Zalloua & Matisoo-Smith 2017.

- ^ 라스무센 외 2006.

- ^ 클레멘트 & 피터슨 2008.

- ^ Buizert, C.; Gkinis, V.; Severinghaus, J.P.; He, F.; Lecavalier, B.S.; Kindler, P.; et al. (5 September 2014). "Greenland temperature response to climate forcing during the last deglaciation". Science. 345 (6201): 1177–1180. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1177B. doi:10.1126/science.1254961. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25190795. S2CID 206558186. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Meissner, K.J. (2007). "Younger Dryas: A data to model comparison to constrain the strength of the overturning circulation". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (21): L21705. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3421705M. doi:10.1029/2007GL031304.

- ^ a b c Broecker, Wallace S.; Denton, George H.; Edwards, R. Lawrence; Cheng, Hai; Alley, Richard B.; Putnam, Aaron E. (1 May 2010). "Putting the Younger Dryas cold event into context". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (9): 1078–1081. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.02.019. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ a b c d e Baldini, James U. L.; Brown, Richard J.; Mawdsley, Natasha (4 July 2018). "Evaluating the link between the sulfur-rich Laacher See volcanic eruption and the Younger Dryas climate anomaly". Climate of the Past. 14 (7): 969–990. doi:10.5194/cp-14-969-2018. ISSN 1814-9324.

- ^ a b c d e f Abbott, P.M.; Niemeier, U.; Timmreck, C.; Riede, F.; McConnell, J.R.; Severi, M.; Fischer, H.; Svensson, A.; Toohey, M.; Reinig, F.; Sigl, M. (December 2021). "Volcanic climate forcing preceding the inception of the Younger Dryas: Implications for tracing the Laacher See eruption". Quaternary Science Reviews. 274: 107260. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107260.

- ^ a b c Sun, N.; Brandon, A. D.; Forman, S. L.; Waters, M. R.; Befus, K. S. (31 July 2020). "Volcanic origin for Younger Dryas geochemical anomalies ca. 12,900 cal B.P." Science Advances. 6 (31): eaax8587. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax8587. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7399481. PMID 32789166.

- ^ Carlson, A.E. (2013). "The Younger Dryas Climate Event" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Quaternary Science. Vol. 3. Elsevier. pp. 126–134. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Björck, S. (2007) 젊은 드라이아스 진동, 세계적 증거. S. A. Elias에서, (Ed.): 4차 과학 백과사전, 3권, pp. 1987-1994. 옥스퍼드의 엘스비어 B.V.

- ^ a b Bjorck, S.; Kromer, B.; Johnsen, S.; Bennike, O.; Hammarlund, D.; Lemdahl, G.; Possnert, G.; Rasmussen, T.L.; Wohlfarth, B.; Hammer, C.U.; Spurk, M. (15 November 1996). "Synchronized terrestrial-atmospheric deglacial records around the North Atlantic". Science. 274 (5290): 1155–1160. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1155B. doi:10.1126/science.274.5290.1155. PMID 8895457. S2CID 45121979.

- ^ Andersson, Gunnar (1896). Svenska växtvärldens historia [Swedish history of the plant world] (in Swedish). Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt & Söner.

- ^ Hartz, N.; Milthers, V. (1901). "Det senglacie ler i Allerød tegelværksgrav" [The late glacial clay of the clay-pit at Alleröd]. Meddelelser Dansk Geologisk Foreningen (Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark) (in Danish). 2 (8): 31–60.

- ^ Mangerud, Jan; Andersen, Svend T.; Berglund, Björn E.; Donner, Joakim J. (16 January 2008). "Quaternary stratigraphy of Norden, a proposal for terminology and classification". Boreas. 3 (3): 109–126. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.1974.tb00669.x.

- ^ Pettit, Paul; White, Mark (2012). The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. p. 477. ISBN 978-0-415-67455-3.

- ^ Stuiver, Minze; Grootes, Pieter M.; Braziunas, Thomas F. (November 1995). "The GISP2 δ18

O Climate Record of the Past 16,500 Years and the Role of the Sun, Ocean, and Volcanoes". Quaternary Research. 44 (3): 341–354. Bibcode:1995QuRes..44..341S. doi:10.1006/qres.1995.1079. S2CID 128688449. - ^ Seppä, H.; Birks, H.H.; Birks, H.J.B. (2002). "Rapid climatic changes during the Greenland stadial 1 (Younger Dryas) to early Holocene transition on the Norwegian Barents Sea coast". Boreas. 31 (3): 215–225. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.2002.tb01068.x. S2CID 129434790.

- ^ Walker, M.J.C. (2004). "A Lateglacial pollen record from Hallsenna Moor, near Seascale, Cumbria, NW England, with evidence for arid conditions during the Loch Lomond (Younger Dryas) Stadial and early Holocene". Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society. 55 (1): 33–42. Bibcode:2004PYGS...55...33W. doi:10.1144/pygs.55.1.33.

- ^ Björck, Svante; Walker, Michael J.C.; Cwynar, Les C.; Johnsen, Sigfus; Knudsen, Karen-Luise; Lowe, J. John; Wohlfarth, Barbara (July 1998). "An event stratigraphy for the Last Termination in the North Atlantic region based on the Greenland ice-core record: a proposal by the INTIMATE group". Journal of Quaternary Science. 13 (4): 283–292. Bibcode:1998JQS....13..283B. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1417(199807/08)13:4<283::AID-JQS386>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ^ Yu, Z.; Eicher, U. (2001). "Three amphi-Atlantic century-scale cold events during the Bølling-Allerød warm period". Géographie Physique et Quaternaire. 55 (2): 171–179. doi:10.7202/008301ar.

- ^ Lisiecki, Lorraine E.; Raymo, Maureen E. (2005). "A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records". Paleoceanography. 20 (1): n/a. Bibcode:2005PalOc..20.1003L. doi:10.1029/2004PA001071. hdl:2027.42/149224. S2CID 12788441.

- ^ Schulz, K.G.; Zeebe, R.E. (2006). "Pleistocene glacial terminations triggered by synchronous changes in Southern and Northern Hemisphere insolation: The insolation canon hypothesis" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 249 (3–4): 326–336. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.249..326S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.07.004 – via U. Hawaii.

- ^ Lisiecki, Lorraine E.; Raymo, Maureen E. (2005). "A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 20 (1): n/a. Bibcode:2005PalOc..20.1003L. doi:10.1029/2004PA001071. hdl:2027.42/149224. S2CID 12788441.

- ^ a b Bradley, R. (2015). Paleoclimatology: Reconstructing climates of the Quaternary (3rd ed.). Kidlington, Oxford, UK: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-386913-5.

- ^ 에글린턴, G., A.B. 스튜어트, A. 로젤, M. 사른타인, U. 플라우만, 그리고 R. 타이드먼(1992) 빙하 종결 I, II, IV에 대한 100년 시간 척도의 세속적 해수면 온도 변화에 대한 분자 기록. 자연. 356:423–426.

- ^ a b Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Kong, X.; Liu, D.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L. (2006). "A possible Younger Dryas-type event during Asian monsoonal Termination 3". Science China Earth Sciences. 49 (9): 982–990. Bibcode:2006ScChD..49..982C. doi:10.1007/s11430-006-0982-4. S2CID 129007340.

- ^ Sima, A.; Paul, A.; Schulz, M. (2004). "The Younger Dryas — an intrinsic feature of late Pleistocene climate change at millennial timescales". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 222 (3–4): 741–750. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.222..741S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.03.026.

- ^ Xiaodong, D.; Liwei, Z.; Shuji, K. (2014). "A review on the Younger Dryas event". Advances in Earth Science. 29 (10): 1095–1109.

- ^ a b c Cheng, Hai; Zhang, Haiwei; Spötl, Christoph; Baker, Jonathan; Sinha, Ashish; Li, Hanying; Bartolomé, Miguel; Moreno, Ana; Kathayat, Gayatri; Zhao, Jingyao; Dong, Xiyu; Li, Youwei; Ning, Youfeng; Jia, Xue; Zong, Baoyun (22 September 2020). "Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (38): 23408–23417. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007869117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7519346. PMID 32900942.

- ^ a b c Alley, Richard B.; Meese, D.A.; Shuman, C.A.; Gow, A.J.; Taylor, K.C.; Grootes, P.M.; et al. (1993). "Abrupt increase in Greenland snow accumulation at the end of the Younger Dryas event". Nature. 362 (6420): 527–529. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..527A. doi:10.1038/362527a0. hdl:11603/24307. S2CID 4325976. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d Alley, Richard B. (2000). "The Younger Dryas cold interval as viewed from central Greenland". Quaternary Science Reviews. 19 (1): 213–226. Bibcode:2000QSRv...19..213A. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00062-1.

- ^ Dansgaard, W.; White, J.W.C.; Johnsen, S.J. (1989). "The abrupt termination of the Younger Dryas climate event". Nature. 339 (6225): 532–534. Bibcode:1989Natur.339..532D. doi:10.1038/339532a0. S2CID 4239314.

- ^ Kobashia, Takuro; Severinghaus, Jeffrey P.; Barnola, Jean-Marc (2008). "4 ± 1.5 °C abrupt warming 11,270 years ago identified from trapped air in Greenland ice". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 268 (3–4): 397–407. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.268..397K. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.01.032.

- ^ Taylor, K.C. (1997). "The Holocene-Younger Dryas transition recorded at Summit, Greenland" (PDF). Science. 278 (5339): 825–827. Bibcode:1997Sci...278..825T. doi:10.1126/science.278.5339.825.

- ^ Spurk, M. (1998). "Revisions and extension of the Hohenheim oak and pine chronologies: New evidence about the timing of the Younger Dryas/Preboreal transition". Radiocarbon. 40 (3): 1107–1116. Bibcode:1998Radcb..40.1107S. doi:10.1017/S0033822200019159.

- ^ Gulliksen, Steinar; Birks, H.H.; Possnert, G.; Mangerud, J. (1998). "A calendar age estimate of the Younger Dryas-Holocene boundary at Krakenes, western Norway". Holocene. 8 (3): 249–259. Bibcode:1998Holoc...8..249G. doi:10.1191/095968398672301347. S2CID 129916026.

- ^ Hughen, K.A.; Southon, J.R.; Lehman, S.J.; Overpeck, J.T. (2000). "Synchronous radiocarbon and climate shifts during the last deglaciation". Science. 290 (5498): 1951–1954. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1951H. doi:10.1126/science.290.5498.1951. PMID 11110659.

- ^ a b Sissons, J.B. (1979). "The Loch Lomond stadial in the British Isles". Nature. 280 (5719): 199–203. Bibcode:1979Natur.280..199S. doi:10.1038/280199a0. S2CID 4342230.

- ^ Walker, Mike; et al. (3 October 2008). "Formal definition and dating of the GSSP, etc" (PDF). Journal of Quaternary Science. 24 (1): 3–17. Bibcode:2009JQS....24....3W. doi:10.1002/jqs.1227. S2CID 40380068. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Muschitiello, F.; Wohlfarth, B. (2015). "Time-transgressive environmental shifts across Northern Europe at the onset of the Younger Dryas". Quaternary Science Reviews. 109: 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.11.015.

- ^ Nakagawa, T; Kitagawa, H.; Yasuda, Y.; Tarasov, P.E.; Nishida, K.; Gotanda, K.; Sawai, Y.; et al. (Yangtze River Civilization Program Members) (2003). "Asynchronous climate changes in the North Atlantic and Japan during the last termination". Science. 299 (5607): 688–691. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..688N. doi:10.1126/science.1078235. PMID 12560547. S2CID 350762.

- ^ Partin, J.W., T.M. Quinn, C.-C. 셴, 와이. 오쿠무라, M.B. 카르데나스, F.P. 시링간, J.L. 배너, K. 린, H.-M. 후, 그리고 F.W Taylor (2014) 열대 지방에서 발생한 급격한 기후 현상으로서 Young Dry의 점진적인 시작과 회복. 네이처 커뮤니케이션즈. 2014년 10월 10일 접수 2015년 7월 13일 접수 2015년 9월 2일 발행

- ^ Williams, Carlie; Flower, Benjamin P.; Hastings, David W.; Guilderson, Thomas P.; Quinn, Kelly A.; Goddard, Ethan A. (7 December 2010). "Deglacial abrupt climate change in the Atlantic Warm Pool: A Gulf of Mexico perspective". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 25 (4): 1–12. Bibcode:2010PalOc..25.4221W. doi:10.1029/2010PA001928. S2CID 58890724. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Benson, Larry; Burdett, James; Lund, Steve; Kashgarian, Michaele; Mensing, Scott (17 July 1997). "Nearly synchronous climate change in the Northern Hemisphere during the last glacial termination". Nature. 388 (6639): 263–265. doi:10.1038/40838. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Shakun, Jeremy D.; Carlson, Anders E. (1 July 2010). "A global perspective on Last Glacial Maximum to Holocene climate change". Quaternary Science Reviews. Special Theme: Arctic Palaeoclimate Synthesis (PP. 1674-1790). 29 (15): 1801–1816. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.03.016. ISSN 0277-3791. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". Grida.no. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "New clue to how last ice age ended". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010.

- ^ Thompson, L.G.; et al. (2000). "Ice-core palaeoclimate records in tropical South America since the Last Glacial Maximum". Journal of Quaternary Science. 15 (4): 377–394. Bibcode:2000JQS....15..377T. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.561.2609. doi:10.1002/1099-1417(200005)15:4<377::AID-JQS542>3.0.CO;2-L.

- ^ Elias, Scott A.; Mock, Cary J. (1 January 2013). Encyclopedia of Quaternary Science. Elsevier. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-444-53642-6. OCLC 846470730.

- ^ Denniston, R.F.; Gonzalez, L.A.; Asmerom, Y.; Polyak, V.; Reagan, M.K.; Saltzman, M.R. (25 December 2001). "A high-resolution speleothem record of climatic variability at the Allerød–Younger Dryas transition in Missouri, central United States". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 176 (1–4): 147–155. Bibcode:2001PPP...176..147D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.556.3998. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00334-0.

- ^ Friele, P.A.; Clague, J.J. (2002). "Younger Dryas readvance in Squamish river valley, southern Coast mountains, British Columbia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 21 (18–19): 1925–1933. Bibcode:2002QSRv...21.1925F. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(02)00081-1.

- ^ Vacco, David A.; Clark, Peter U.; Mix, Alan C.; Cheng, Hai; Edwards, R. Lawrence (1 September 2005). "A speleothem record of Younger Dryas cooling, Klamath Mountains, Oregon, USA". Quaternary Research. 64 (2): 249–256. Bibcode:2005QuRes..64..249V. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2005.06.008. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 1633393.

- ^ Hassett, Brenna (2017). Built on Bones: 15,000 years of urban life and death. London, UK: Bloomsbury Sigma. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-4729-2294-6.

- ^ Brakenridge, G. Robert. 2011. 중심부 붕괴 초신성과 더 젊은 드라이아스/말단 란초라브레인 멸종. Elsevier, 2018년 9월 23일 검색

- ^ Gill, J.L.; Williams, J.W.; Jackson, S.T.; Lininger, K.B.; Robinson, G.S. (19 November 2009). "Pleistocene megafaunal collapse, novel plant communities, and enhanced fire regimes in North America" (PDF). Science. 326 (5956): 1100–1103. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1100G. doi:10.1126/science.1179504. PMID 19965426. S2CID 206522597.

- ^ a b Rainsley, Eleanor; Menviel, Laurie; Fogwill, Christopher J.; Turney, Chris S. M.; Hughes, Anna L. C.; Rood, Dylan H. (9 August 2018). "Greenland ice mass loss during the Younger Dryas driven by Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation feedbacks". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 11307. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-29226-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6085367. PMID 30093676.

- ^ Larsen, Nicolaj K.; Funder, Svend; Linge, Henriette; Möller, Per; Schomacker, Anders; Fabel, Derek; Xu, Sheng; Kjær, Kurt H. (1 September 2016). "A Younger Dryas re-advance of local glaciers in north Greenland". Quaternary Science Reviews. Special Issue: PAST Gateways (Palaeo-Arctic Spatial and Temporal Gateways). 147: 47–58. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.10.036. ISSN 0277-3791. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Miller, D. Shane; Gingerich, Joseph A.M. (March 2013). "Regional variation in the terminal Pleistocene and early Holocene radiocarbon record of eastern North America". Quaternary Research. 79 (2): 175–188. Bibcode:2013QuRes..79..175M. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2012.12.003. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 129095089.

- ^ a b c Meltzer, David J.; Holliday, Vance T. (1 March 2010). "Would North American Paleoindians have noticed Younger Dryas age climate changes?". Journal of World Prehistory. 23 (1): 1–41. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9032-4. ISSN 0892-7537. S2CID 3086333.

- ^ Young, Richard A.; Gordon, Lee M.; Owen, Lewis A.; Huot, Sebastien; Zerfas, Timothy D. (17 November 2020). "Evidence for a late glacial advance near the beginning of the Younger Dryas in western New York State: An event postdating the record for local Laurentide ice sheet recession". Geosphere. 17 (1): 271–305. doi:10.1130/ges02257.1. ISSN 1553-040X. S2CID 228885304.

- ^ Peteet, D. (1 January 1995). "Global Younger Dryas?". Quaternary International. 28: 93–104. Bibcode:1995QuInt..28...93P. doi:10.1016/1040-6182(95)00049-o.

- ^ Shuman, Bryan; Bartlein, Patrick; Logar, Nathaniel; Newby, Paige; Webb, Thompson III (September 2002). "Parallel climate and vegetation responses to the early Holocene collapse of the Laurentide Ice Sheet". Quaternary Science Reviews. 21 (16–17): 1793–1805. Bibcode:2002QSRv...21.1793S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.580.8423. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(02)00025-2.

- ^ Dorale, J.A.; Wozniak, L.A.; Bettis, E.A.; Carpenter, S.J.; Mandel, R.D.; Hajic, E.R.; Lopinot, N.H.; Ray, J.H. (2010). "Isotopic evidence for Younger Dryas aridity in the North American midcontinent". Geology. 38 (6): 519–522. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..519D. doi:10.1130/g30781.1.

- ^ Williams, John W.; Post, David M.; Cwynar, Les C.; Lotter, André F.; Levesque, André J. (1 November 2002). "Rapid and widespread vegetation responses to past climate change in the North Atlantic region". Geology. 30 (11): 971–974. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..971W. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0971:rawvrt>2.0.co;2. hdl:1874/19644. ISSN 0091-7613. S2CID 130800017.

- ^ Dieffenbacher-Krall, Ann C.; Borns, Harold W.; Nurse, Andrea M.; Langley, Geneva E.C.; Birkel, Sean; Cwynar, Les C.; Doner, Lisa A.; Dorion, Christopher C.; Fastook, James (1 March 2016). "Younger Dryas paleoenvironments and ice dynamics in northern Maine: A multi-proxy, case history". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): 67–87. doi:10.1656/045.023.0105. ISSN 1092-6194. S2CID 87182583.

- ^ a b Liu, Yao; Andersen, Jennifer J.; Williams, John W.; Jackson, Stephen T. (March 2012). "Vegetation history in central Kentucky and Tennessee (USA) during the last glacial and deglacial periods". Quaternary Research. 79 (2): 189–198. Bibcode:2013QuRes..79..189L. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2012.12.005. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 55704048.

- ^ a b c Griggs, Carol; Peteet, Dorothy; Kromer, Bernd; Grote, Todd; Southon, John (1 April 2017). "A tree-ring chronology and paleoclimate record for the Younger Dryas–Early Holocene transition from northeastern North America". Journal of Quaternary Science. 32 (3): 341–346. Bibcode:2017JQS....32..341G. doi:10.1002/jqs.2940. ISSN 1099-1417. S2CID 133557318.

- ^ a b Elias, Scott A.; Mock, Cary J. (2013). Encyclopedia of quaternary science. Elsevier. pp. 126–132. ISBN 978-0-444-53642-6. OCLC 846470730.

- ^ Grimm, Eric C.; Watts, William A.; Jacobson, George L. Jr.; Hansen, Barbara C.S.; Almquist, Heather R.; Dieffenbacher-Krall, Ann C. (September 2006). "Evidence for warm wet Heinrich events in Florida". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (17–18): 2197–2211. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.2197G. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.04.008.

- ^ Yu, Zicheng; Eicher, Ulrich (1998). "Abrupt climate oscillations during the last deglaciation in central North America". Science. 282 (5397): 2235–2238. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.2235Y. doi:10.1126/science.282.5397.2235. JSTOR 2897126. PMID 9856941.

- ^ a b Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Shea, John J.; Lieberman, Daniel (2009). Transitions in prehistory: Essays in honor of Ofer Bar-Yosef. American School of Prehistoric Research. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-340-4. OCLC 276334680.

- ^ Nordt, Lee C.; Boutton, Thomas W.; Jacob, John S.; Mandel, Rolfe D. (1 September 2002). "C4 Plant productivity and climate – CO2 variations in south-central Texas during the late Quaternary". Quaternary Research. 58 (2): 182–188. Bibcode:2002QuRes..58..182N. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2344. S2CID 129027867.

- ^ Lowell, Thomas V.; Larson, Graham J.; Hughes, John D.; Denton, George H. (25 March 1999). "Age verification of the Lake Gribben forest bed and the Younger Dryas advance of the Laurentide ice sheet". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 36 (3): 383–393. Bibcode:1999CaJES..36..383L. doi:10.1139/e98-095. ISSN 0008-4077.

- ^ Williams, John W.; Shuman, Bryan N.; Webb, Thompson (1 December 2001). "Dissimilarity analyses of late-Quaternary vegetation and climate in eastern North America". Ecology. 82 (12): 3346–3362. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[3346:daolqv]2.0.co;2. ISSN 1939-9170.

- ^ Erin, Metin I. (2013). Hunter-gatherer behavior: Human response during the Younger Dryas. Left Coast Press. ISBN 978-1-59874-603-7. OCLC 907959421.

- ^ MacLeod, David Matthew; Osborn, Gerald; Spooner, Ian (1 April 2006). "A record of post-glacial moraine deposition and tephra stratigraphy from Otokomi Lake, Rose Basin, Glacier National Park, Montana". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 43 (4): 447–460. Bibcode:2006CaJES..43..447M. doi:10.1139/e06-001. ISSN 0008-4077. S2CID 55554570.

- ^ a b Mumma, Stephanie Ann; Whitlock, Cathy; Pierce, Kenneth (1 April 2012). "A 28,000 year history of vegetation and climate from Lower Red Rock Lake, Centennial Valley, southwestern Montana, USA". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 326: 30–41. Bibcode:2012PPP...326...30M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.01.036.

- ^ a b Brunelle, Andrea; Whitlock, Cathy (July 2003). "Postglacial fire, vegetation, and climate history in the Clearwater Range, northern Idaho, USA". Quaternary Research. 60 (3): 307–318. Bibcode:2003QuRes..60..307B. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2003.07.009. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 129531002.

- ^ "Precise cosmogenic 10Be measurements in western North America: Support for a global Younger Dryas cooling event". ResearchGate. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Reasoner, Mel A.; Osborn, Gerald; Rutter, N. W. (1 May 1994). "Age of the Crowfoot advance in the Canadian Rocky Mountains: A glacial event coeval with the Younger Dryas oscillation". Geology. 22 (5): 439–442. Bibcode:1994Geo....22..439R. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1994)022<0439:AOTCAI>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Reasoner, Mel A.; Jodry, Margret A. (1 January 2000). "Rapid response of alpine timberline vegetation to the Younger Dryas climate oscillation in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, USA". Geology. 28 (1): 51–54. Bibcode:2000Geo....28...51R. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<51:RROATV>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Briles, Christy E.; Whitlock, Cathy; Meltzer, David J. (January 2012). "Last glacial–interglacial environments in the southern Rocky Mountains, USA and implications for Younger Dryas-age human occupation". Quaternary Research. 77 (1): 96–103. Bibcode:2012QuRes..77...96B. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2011.10.002. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 9377272.

- ^ Davis, P. Thompson; Menounos, Brian; Osborn, Gerald (1 October 2009). "Holocene and latest Pleistocene alpine glacier fluctuations: a global perspective". Quaternary Science Reviews. 28 (21): 2021–2033. Bibcode:2009QSRv...28.2021D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.05.020.

- ^ Osborn, Gerald; Gerloff, Lisa (1 January 1997). "Latest pleistocene and early Holocene fluctuations of glaciers in the Canadian and northern American Rockies". Quaternary International. 38: 7–19. Bibcode:1997QuInt..38....7O. doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(96)00026-2.

- ^ Feng, Weimin; Hardt, Benjamin F.; Banner, Jay L.; Meyer, Kevin J.; James, Eric W.; Musgrove, MaryLynn; Edwards, R. Lawrence; Cheng, Hai; Min, Angela (1 September 2014). "Changing amounts and sources of moisture in the U.S. southwest since the Last Glacial Maximum in response to global climate change". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 401: 47–56. Bibcode:2014E&PSL.401...47F. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.046.

- ^ Barron, John A.; Heusser, Linda; Herbert, Timothy; Lyle, Mitch (1 March 2003). "High-resolution climatic evolution of coastal northern California during the past 16,000 years". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 18 (1): 1020. Bibcode:2003PalOc..18.1020B. doi:10.1029/2002pa000768. ISSN 1944-9186.

- ^ Kienast, Stephanie S.; McKay, Jennifer L. (15 April 2001). "Sea surface temperatures in the subarctic northeast Pacific reflect millennial-scale climate oscillations during the last 16 kyrs". Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (8): 1563–1566. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28.1563K. doi:10.1029/2000gl012543. ISSN 1944-8007.

- ^ Mathewes, Rolf W. (1 January 1993). "Evidence for Younger Dryas-age cooling on the North Pacific coast of America". Quaternary Science Reviews. 12 (5): 321–331. Bibcode:1993QSRv...12..321M. doi:10.1016/0277-3791(93)90040-s.

- ^ a b Vacco, David A.; Clark, Peter U.; Mix, Alan C.; Cheng, Hai; Edwards, R. Lawrence (September 2005). "A speleothem record of Younger Dryas cooling, Klamath Mountains, Oregon, USA". Quaternary Research. 64 (2): 249–256. Bibcode:2005QuRes..64..249V. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2005.06.008. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 1633393.

- ^ Chase, Marianne; Bleskie, Christina; Walker, Ian R.; Gavin, Daniel G.; Hu, Feng Sheng (January 2008). "Midge-inferred Holocene summer temperatures in southeastern British Columbia, Canada". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 257 (1–2): 244–259. Bibcode:2008PPP...257..244C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.10.020.

- ^ Friele, Pierre A.; Clague, John J. (1 October 2002). "Younger Dryas re‑advance in Squamish river valley, southern Coast mountains, British Columbia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 21 (18): 1925–1933. Bibcode:2002QSRv...21.1925F. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(02)00081-1.

- ^ Kovanen, Dori J. (1 June 2002). "Morphologic and stratigraphic evidence for Allerød and Younger Dryas age glacier fluctuations of the Cordilleran ice sheet, British Columbia, Canada, and northwest Washington, U.S.A". Boreas. 31 (2): 163–184. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.2002.tb01064.x. ISSN 1502-3885. S2CID 129896627.

- ^ Heine, Jan T. (1 December 1998). "Extent, timing, and climatic implications of glacier advances Mount Rainier, Washington, U.S.A., at the Pleistocene/Holocene transition". Quaternary Science Reviews. 17 (12): 1139–1148. Bibcode:1998QSRv...17.1139H. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(97)00077-2.

- ^ Grigg, Laurie D.; Whitlock, Cathy (May 1998). "Late-glacial vegetation and climate change in western Oregon". Quaternary Research. 49 (3): 287–298. Bibcode:1998QuRes..49..287G. doi:10.1006/qres.1998.1966. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 129306849.

- ^ Gavin, Daniel G.; Brubaker, Linda B.; Greenwald, D. Noah (November 2013). "Post-glacial climate and fire-mediated vegetation change on the western Olympic Peninsula, Washington, USA". Ecological Monographs. 83 (4): 471–489. doi:10.1890/12-1742.1. ISSN 0012-9615.

- ^ Grigg, Laurie D.; Whitlock, Cathy; Dean, Walter E. (July 2001). "Evidence for millennial-scale climate change during Marine Isotope Stages 2 and 3 at Little Lake, western Oregon, USA". Quaternary Research. 56 (1): 10–22. Bibcode:2001QuRes..56...10G. doi:10.1006/qres.2001.2246. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 5850258.

- ^ Hershler, Robert; Madsen, D.B.; Currey, D.R. (11 December 2002). "Great Basin aquatic systems history". Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences. 33 (33): 1–405. Bibcode:2002SCoES..33.....H. doi:10.5479/si.00810274.33.1. ISSN 0081-0274. S2CID 129249661.

- ^ Briles, Christy E.; Whitlock, Cathy; Bartlein, Patrick J. (July 2005). "Postglacial vegetation, fire, and climate history of the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon, USA". Quaternary Research. 64 (1): 44–56. Bibcode:2005QuRes..64...44B. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2005.03.001. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 17330671.

- ^ Cole, Kenneth L.; Arundel, Samantha T. (2005). "Carbon isotopes from fossil packrat pellets and elevational movements of Utah agave plants reveal the Younger Dryas cold period in Grand Canyon, Arizona". Geology. 33 (9): 713. Bibcode:2005Geo....33..713C. doi:10.1130/g21769.1. S2CID 55309102.

- ^ Mangerud, Jan (January 2021). "The discovery of the Younger Dryas, and comments on the current meaning and usage of the term". Boreas. 50 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/bor.12481. ISSN 0300-9483.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (2 December 2009). "Big freeze: Earth could plunge into sudden ice age". Live Science. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ a b Severinghaus, Jeffrey P.; et al. (1998). "Timing of abrupt climate change at the end of the Younger Dryas interval from thermally fractionated gases in polar ice". Nature. 391 (6663): 141–146. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..141S. doi:10.1038/34346. S2CID 4426618.

- ^ Atkinson, T.C.; Briffa, K.R.; Coope, G.R. (1987). "Seasonal temperatures in Britain during the past 22,000 years, reconstructed using beetle remains". Nature. 325 (6105): 587–592. Bibcode:1987Natur.325..587A. doi:10.1038/325587a0. S2CID 4306228.

- ^ Golledge, Nicholas; Hubbard, Alun; Bradwell, Tom (30 June 2009). "Influence of seasonality on glacier mass balance, and implications for palaeoclimate reconstructions". Climate Dynamics. 35 (5): 757–770. doi:10.1007/s00382-009-0616-6. ISSN 0930-7575. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Litt, Thomas; Schmincke, Hans-Ulrich; Kromer, Bernd (1 January 2003). "Environmental response to climatic and volcanic events in central Europe during the Weichselian Lateglacial". Quaternary Science Reviews. Environmental response to climate and human impact in central Eur ope during the last 15000 years - a German contribution to PAGES-PEPIII. 22 (1): 7–32. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(02)00180-4. ISSN 0277-3791. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Çiner, Attila; Stepišnik, Uroš; Sarıkaya, M. Akif; Žebre, Manja; Yıldırım, Cengiz (24 June 2019). "Last Glacial Maximum and Younger Dryas piedmont glaciations in Blidinje, the Dinaric Mountains (Bosnia and Herzegovina): insights from 36Cl cosmogenic dating". Mediterranean Geoscience Reviews. 1 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1007/s42990-019-0003-4. ISSN 2661-863X. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger, Zsófia; Kern, Zoltán; Temovski, Marjan; Madarász, Balázs; Milevski, Ivica; Braucher, Régis (15 February 2020). "Last deglaciation in the central Balkan Peninsula: Geochronological evidence from the Jablanica Mt. (North Macedonia)". Geomorphology. 351: 106985. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.106985. ISSN 0169-555X. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Dean, Jonathan R.; Jones, Matthew D.; Leng, Melanie J.; Noble, Stephen R.; Metcalfe, Sarah E.; Sloane, Hilary J.; Sahy, Diana; Eastwood, Warren J.; Roberts, C. Neil (15 September 2015). "Eastern Mediterranean hydroclimate over the late glacial and Holocene, reconstructed from the sediments of Nar lake, central Turkey, using stable isotopes and carbonate mineralogy". Quaternary Science Reviews. 124: 162–174. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.07.023. ISSN 0277-3791. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Fleitmann, D.; Cheng, H.; Badertscher, S.; Edwards, R. L.; Mudelsee, M.; Göktürk, O. M.; Fankhauser, A.; Pickering, R.; Raible, C. C.; Matter, A.; Kramers, J.; Tüysüz, O. (6 October 2009). "Timing and climatic impact of Greenland interstadials recorded in stalagmites from northern Turkey". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (19). doi:10.1029/2009GL040050. ISSN 0094-8276. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Nykamp, Moritz; Becker, Fabian; Braun, Ricarda; Pöllath, Nadja; Knitter, Daniel; Peters, Joris; Schütt, Brigitta (February 2021). "Sediment cascades and the entangled relationship between human impact and natural dynamics at the pre‐pottery Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe, Anatolia". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 46 (2): 430–442. doi:10.1002/esp.5035. ISSN 0197-9337. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Zhang, Zhiping; Liu, Jianbao; Chen, Shengqian; Chen, Jie; Zhang, Shanjia; Xia, Huan; Shen, Zhongwei; Wu, Duo; Chen, Fahu (27 June 2018). "Nonlagged Response of Vegetation to Climate Change During the Younger Dryas: Evidence from High-Resolution Multiproxy Records from an Alpine Lake in Northern China". Journal of Geophysical Research. 123 (14): 7065–7075. Bibcode:2018JGRD..123.7065Z. doi:10.1029/2018JD028752. S2CID 134259679.

- ^ Hong, Bing; Hong, Yetang; Uchida, Masao; Shibata, Yasuyuki; Cai, Cheng; Peng, Haijun; Zhu, Yongxuan; Wang, Yu; Yuan, Linggui (1 August 2014). "Abrupt variations of Indian and East Asian summer monsoons during the last deglacial stadial and interstadial". Quaternary Science Reviews. 97: 58–70. Bibcode:2014QSRv...97...58H. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.05.006. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Bar-Yosef, O.; Belfer-Cohen, A. (31 December 2002) [1998]. "Facing environmental crisis. Societal and cultural changes at the transition from the Younger Dryas to the Holocene in the Levant". In Cappers, R.T.J.; Bottema, S. (eds.). The Dawn of Farming in the Near East. Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence, and Environment. Vol. 6. Berlin, DE: Ex Oriente. pp. 55–66. ISBN 3-9804241-5-4, ISBN 978-398042415-8.

- ^ Mithen, Steven J. (2003). After the Ice: A global human history, 20,000–5000 BC (paperback ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 46–55.

- ^ Munro, N.D. (2003). "Small game, the younger dryas, and the transition to agriculture in the southern levant" (PDF). Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte. 12: 47–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2005.

- ^ Balter, Michael (2010). "Archaeology: The tangled roots of agriculture". Science. 327 (5964): 404–406. doi:10.1126/science.327.5964.404. PMID 20093449.

- ^ a b Blanchon, P. (2011a). "Meltwater pulses". In Hopley, D. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs: Structure, form and process. Springer-Verlag Earth Science. pp. 683–690. ISBN 978-90-481-2638-5.

- ^ Blanchon, P. (2011b). "Backstepping". In Hopley, D. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs: Structure, form and process. Springer-Verlag Earth Science Series. pp. 77–84. ISBN 978-90-481-2638-5.

- ^ Blanchon, P.; Shaw, J. (1995). "Reef drowning during the last deglaciation: Evidence for catastrophic sea-level rise and ice-sheet collapse". Geology. 23 (1): 4–8. Bibcode:1995Geo....23....4B. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0004:RDDTLD>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ a b Bard, E.; Hamelin, B.; Delanghe-Sabatier, D. (2010). "Deglacial meltwater Pulse 1B and Younger Dryas sea levels revisited with boreholes at Tahiti". Science. 327 (5970): 1235–1237. Bibcode:2010Sci...327.1235B. doi:10.1126/science.1180557. PMID 20075212. S2CID 29689776.

- ^ a b Lohne, Ø.S.; Bondevik, S.; Mangeruda, J.; Svendsena, J.I. (2007). "Sea-level fluctuations imply that the Younger Dryas ice-sheet expansion in western Norway commenced during the Allerød". Quaternary Science Reviews. 26 (17–18): 2128–2151. Bibcode:2007QSRv...26.2128L. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.04.008. hdl:1956/1179.

- ^ Lohne, Øystein S.; Bondevik, Stein; Mangerud, Jan; Schrader, Hans (July 2004). "Calendar year age estimates of Allerød–Younger Dryas sea-level oscillations at Os, western Norway". Journal of Quaternary Science. 19 (5): 443–464. doi:10.1002/jqs.846. ISSN 0267-8179. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Keigwin, L. D.; Schlegel, M. A. (22 June 2002). "Ocean ventilation and sedimentation since the glacial maximum at 3 km in the western North Atlantic". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 3 (6): 1034. Bibcode:2002GGG.....3.1034K. doi:10.1029/2001GC000283. S2CID 129340391.

- ^ a b Broecker, Wallace S. (2006). "Was the Younger Dryas triggered by a flood?". Science. 312 (5777): 1146–1148. doi:10.1126/science.1123253. PMID 16728622. S2CID 39544213.

- ^ Keigwin, L. D.; Klotsko, S.; Zhao, N.; Reilly, B.; Giosan, L.; Driscoll, N. W. (August 2018). "Deglacial floods in the Beaufort Sea preceded Younger Dryas cooling". Nature Geoscience. 11 (8): 599–604. doi:10.1038/s41561-018-0169-6. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ Murton, Julian B.; Bateman, Mark D.; Dallimore, Scott R.; Teller, James T.; Yang, Zhirong (2010). "Identification of Younger Dryas outburst flood path from Lake Agassiz to the Arctic Ocean". Nature. 464 (7289): 740–743. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..740M. doi:10.1038/nature08954. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20360738. S2CID 4425933.

- ^ Süfke, Finn; Gutjahr, Marcus; Keigwin, Lloyd D.; Reilly, Brendan; Giosan, Liviu; Lippold, Jörg (25 April 2022). "Arctic drainage of Laurentide Ice Sheet meltwater throughout the past 14,700 years". Communications Earth & Environment. 3 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00428-3. ISSN 2662-4435. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Muschitiello, Francesco; Pausata, Francesco S. R.; Watson, Jenny E.; Smittenberg, Rienk H.; Salih, Abubakr A. M.; Brooks, Stephen J.; Whitehouse, Nicola J.; Karlatou-Charalampopoulou, Artemis; Wohlfarth, Barbara (17 November 2015). "Fennoscandian freshwater control on Greenland hydroclimate shifts at the onset of the Younger Dryas". Nature Communications. 6 (1): 8939. doi:10.1038/ncomms9939. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4660357. PMID 26573386.

- ^ Condron, Alan; Joyce, Anthony J.; Bradley, Raymond S. (1 April 2020). "Arctic sea ice export as a driver of deglacial climate". Geology. 48 (4): 395–399. doi:10.1130/G47016.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Eisenman, I.; Bitz, C.M.; Tziperman, E. (2009). "Rain driven by receding ice sheets as a cause of past climate change". Paleoceanography. 24 (4): PA4209. Bibcode:2009PalOc..24.4209E. doi:10.1029/2009PA001778. S2CID 6896108.

- ^ a b Wang, L.; Jiang, W. Y.; Jiang, D. B.; Zou, Y. F.; Liu, Y. Y.; Zhang, E. L.; Hao, Q. Z.; Zhang, D. G.; Zhang, D. T.; Peng, Z. Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, X. D.; Lu, H. Y. (27 December 2018). "Prolonged Heavy Snowfall During the Younger Dryas". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 123 (24). doi:10.1029/2018JD029271. ISSN 2169-897X.

- ^ a b Abdul, N. A.; Mortlock, R. A.; Wright, J. D.; Fairbanks, R. G. (February 2016). "Younger Dryas sea level and meltwater pulse 1B recorded in Barbados reef crest coral Acropora palmata". Paleoceanography. 31 (2): 330–344. doi:10.1002/2015PA002847. ISSN 0883-8305.

- ^ Dansgaard, W; Clausen, H.B.; Gundestrup, N.; Hammer, C.U.; Johnsen, S.F.; Kristinsdottir, P.M.; Reeh, N. (1982). "A new Greenland deep ice core". Science. 218 (4579): 1273–1277. Bibcode:1982Sci...218.1273D. doi:10.1126/science.218.4579.1273. PMID 17770148. S2CID 35224174.

- ^ Lynch-Stieglitz, J (2017). "The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and abrupt climate change". Annual Review of Marine Science. 9: 83–104. Bibcode:2017ARMS....9...83L. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060415. PMID 27814029.

- ^ a b c Nye, Henry; Condron, Alan (30 June 2021). "Assessing the statistical uniqueness of the Younger Dryas: a robust multivariate analysis". Climate of the Past. 17 (3): 1409–1421. doi:10.5194/cp-17-1409-2021. ISSN 1814-9332.

- ^ la Violette, P.A. (2011). "Evidence for a Solar flare cause of the Pleistocene mass extinction". Radiocarbon. 53 (2): 303–323. Bibcode:2011Radcb..53..303L. doi:10.1017/S0033822200056575. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Staff Writers (6 June 2011). "Did a massive Solar proton event fry the Earth?". Space Daily. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Gramling C (26 June 2018). "Why won't this debate about an ancient cold snap die?". Science News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Boslough, Mark (March 2023). "Apocalypse!". Skeptic Magazine. 28 (1): 51–59.

- ^ Sigl, M.; Winstrup, M.; McConnell, J. R.; Welten, K. C.; Plunkett, G.; Ludlow, F.; Büntgen, U.; Caffee, M.; Chellman, N.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Fischer, H.; Kipfstuhl, S.; Kostick, C.; Maselli, O. J.; Mekhaldi, F. (July 2015). "Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years". Nature. 523 (7562): 543–549. doi:10.1038/nature14565. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Kobashi, Takuro; Menviel, Laurie; Jeltsch-Thömmes, Aurich; Vinther, Bo M.; Box, Jason E.; Muscheler, Raimund; Nakaegawa, Toshiyuki; Pfister, Patrik L.; Döring, Michael; Leuenberger, Markus; Wanner, Heinz; Ohmura, Atsumu (3 May 2017). "Volcanic influence on centennial to millennial Holocene Greenland temperature change". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 1441. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01451-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5431187. PMID 28469185.

- ^ Kobashi, Takuro; Menviel, Laurie; Jeltsch-Thömmes, Aurich; Vinther, Bo M.; Box, Jason E.; Muscheler, Raimund; Nakaegawa, Toshiyuki; Pfister, Patrik L.; Döring, Michael; Leuenberger, Markus; Wanner, Heinz; Ohmura, Atsumu (3 May 2017). "Volcanic influence on centennial to millennial Holocene Greenland temperature change". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 1441. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01451-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5431187. PMID 28469185.

- ^ Miller, Gifford H.; Geirsdóttir, Áslaug; Zhong, Yafang; Larsen, Darren J.; Otto-Bliesner, Bette L.; Holland, Marika M.; Bailey, David A.; Refsnider, Kurt A.; Lehman, Scott J.; Southon, John R.; Anderson, Chance; Björnsson, Helgi; Thordarson, Thorvaldur (January 2012). "Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks: Little Ice Age Triggererd by Volcanism". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (2): n/a. doi:10.1029/2011GL050168.

- ^ Brauer, Achim; Endres, Christoph; Günter, Christina; Litt, Thomas; Stebich, Martina; Negendank, Jörg F.W. (March 1999). "High resolution sediment and vegetation responses to Younger Dryas climate change in varved lake sediments from Meerfelder Maar, Germany". Quaternary Science Reviews. 18 (3): 321–329. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(98)00084-5.

- ^ van den Bogaard, Paul (June 1995). "40Ar/39Ar ages of sanidine phenocrysts from Laacher See Tephra (12,900 yr BP): Chronostratigraphic and petrological significance". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 133 (1–2): 163–174. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(95)00066-L.

- ^ Reinig, Frederick; Wacker, Lukas; Jöris, Olaf; Oppenheimer, Clive; Guidobaldi, Giulia; Nievergelt, Daniel; Adolphi, Florian; Cherubini, Paolo; Engels, Stefan; Esper, Jan; Land, Alexander; Lane, Christine; Pfanz, Hardy; Remmele, Sabine; Sigl, Michael (1 July 2021). "Precise date for the Laacher See eruption synchronizes the Younger Dryas". Nature. 595 (7865): 66–69. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03608-x. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b c Baldini, James U. L.; Brown, Richard J.; Wadsworth, Fabian B.; Paine, Alice R.; Campbell, Jack W.; Green, Charlotte E.; Mawdsley, Natasha; Baldini, Lisa M. (5 July 2023). "Possible magmatic CO2 influence on the Laacher See eruption date". Nature. 619 (7968): E1–E2. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05965-1. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Baldini, James U.L.; Brown, Richard J.; McElwaine, Jim N. (30 November 2015). "Was millennial scale climate change during the Last Glacial triggered by explosive volcanism?". Scientific Reports. 5 (1). doi:10.1038/srep17442. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ Lohmann, Johannes; Svensson, Anders (2 September 2022). "Ice core evidence for major volcanic eruptions at the onset of Dansgaard–Oeschger warming events". Climate of the Past. 18 (9): 2021–2043. doi:10.5194/cp-18-2021-2022. ISSN 1814-9332.

- ^ Shakun, Jeremy D.; Clark, Peter U.; He, Feng; Marcott, Shaun A.; Mix, Alan C.; Liu, Zhenyu; Oto-Bliesner, Bette; Schmittner, Andreas; Bard, Edouard (4 April 2012). "Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation". Nature. 484 (7392): 49–54. Bibcode:2012Natur.484...49S. doi:10.1038/nature10915. hdl:2027.42/147130. PMID 22481357. S2CID 2152480. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

인용 출처

- Zalloua, Pierre A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (2017). "Mapping Post-Glacial expansions: The Peopling of Southwest Asia". Scientific Reports. 7. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740338P. doi:10.1038/srep40338. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5216412. PMID 28059138.

- Rasmussen, S. O.; Andersen, K. K.; Svensson, A. M.; Steffensen, J. P.; Vinther, B. M.; Clausen, H. B.; Siggaard-Andersen, M.-L.; Johnsen, S. J.; Larsen, L. B.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Bigler, M. (2006). "A new Greenland ice core chronology for the last glacial termination" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (D6). Bibcode:2006JGRD..111.6102R. doi:10.1029/2005JD006079. ISSN 0148-0227.

- Clement, Amy C.; Peterson, Larry C. (2008). "Mechanisms of abrupt climate change of the last glacial period". Reviews of Geophysics. 46 (4): 1–39. Bibcode:2008RvGeo..46.4002C. doi:10.1029/2006RG000204. S2CID 7828663. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

외부 링크

- "Study confirms mechanism for current shutdowns, European cooling" (Press release). Oregon State University. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Broecker, W.S. (1999). "What If the Conveyor Were to Shut Down?". GSA Today. 9 (1): 1–7. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Calvin, W.H. (January 1998). "The great climate flip-flop". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 281. pp. 47–64. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Tarasov, L.; Peltier, W.R. (June 2005). "Arctic freshwater forcing of the Younger Dryas cold reversal" (PDF). Nature. 435 (7042): 662–665. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..662T. doi:10.1038/nature03617. PMID 15931219. S2CID 4375841. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2015.

- Acosta; et al. (2018). "Climate change and peopling of the Neotropics during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition". Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 70: 1–19. doi:10.18268/BSGM2018v70n1a1.

- "Cometary debris may have destroyed Paleolithic settlement 12,800 years ago". Science News (sci-news.com) (Press release). 2 July 2020.

- When the Earth suddenly stopped warming. PBS Eons (short ed. vid.). 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021 – via YouTube.