웨스턴 헌터-채터러

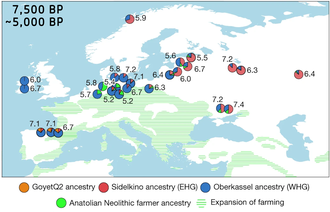

Western Hunter-Gatherer14ka에서 9ka 사이의 유럽의 수렵-채집인들의 유전적 조상으로, 서부 수렵-채집인들(WHG)의 주요 지역은 파란색입니다. 개별 번호는 보정된 샘플 날짜에 해당합니다.[1] |

고고학에서 서유럽 헌터-채터(WHG), 서유럽 헌터-채터, 서유럽 헌터-채터, 빌라브루나 클러스터 또는 오버카셀 클러스터(c.15,000~5,000 BP)라는 용어는 현대 유럽인들의 독특한 조상 구성 요소에 붙여진 이름입니다. 마지막 빙하의 빙하가 후퇴한 후 서쪽의 영국 섬에서 동쪽의 카르파티아 섬까지 서부, 남부 및 중부 유럽 전역에 흩어져 살았던 중석기 수렵-채집인들의 혈통을 나타냅니다.[2]

스칸디나비아 수렵 채집인(SHG)과 동부 수렵 채집인(EHG)과 함께 WHG는 초기 홀로세 유럽의 빙하기에 세 개의 주요 유전 그룹 중 하나를 구성했습니다.[3] WHG와 EHG 사이의 국경은 대략 다뉴브강 하류에서 드니퍼강의 서쪽 숲을 따라 서쪽 발트해를 향해 북쪽으로 뻗어 있었습니다.[2]

SHG는 결국 WHG와 EHG가 거의 동일하게 혼합되었습니다. 한때 유럽 전역의 주요 인구였던 WHG는 신석기 초기 동안 초기 유럽 농부들(EEF)의 연속적인 확장으로 인해 크게 대체되었지만 중기 신석기 동안 다시 부활했습니다. 후기 신석기 시대와 초기 청동기 시대에 폰틱-카스피 산맥의 웨스턴 스텝 헤르더(WSH)가 대규모 확장에 착수하여 WHG를 더욱 대체했습니다. 오늘날의 인구 중에서 WHG 조상은 발트해 동부의 인구 중에서 가장 흔합니다.[4]

조사.

WHG(Western Hunter-Geatherers)는 대부분의 현대 유럽인의 조상에 기여하는 뚜렷한 조상 요소로 인식됩니다.[5] 대부분의 유럽인들은 폰틱-카스피안 스텝에서 WHG, EEF 및 WSH를 혼합한 것으로 모델링할 수 있습니다.[6] WHG는 또한 초기 유럽 농부들(EEF)과 같은 다른 고대 집단들의 조상에 기여했지만, 그들은 대부분 아나톨리아 혈통이었습니다.[5] 신석기 시대가 확장되면서 EEF는 유럽 대부분의 지역에서 유전자 풀을 지배하게 되었지만 WHG 조상은 신석기 초기에서 중기 신석기까지 서유럽에서 다시 부활했습니다.[7]

유럽 대륙 진출(14,000BP)

WHG 자체는 약 14,000년 전, 뵐링-알뢰드 인터스타디얼 기간 동안 빙하기 이후 첫 번째 주요 온난화 시기에 형성된 것으로 추정됩니다. 그들은 빙하기 말에 유럽 내의 주요 인구 이동을 나타내며, 아마도 동남 유럽 또는 서아시아 난민에서 유럽 대륙으로 인구가 확대되었을 것입니다.[8] 그들의 조상들은 기원전 4만년경에 동부 유라시아인들과 갈라졌고, 고대 북유라시아인들(ANE)과는 24,000 BP(말타 소년의 나이로 추정되는 날짜) 이전에 갈라진 것으로 생각됩니다. 이후 야나 코뿔소 뿔 유적지의 발견으로 서-유라시아와 동-유라시아 계통이 갈라진 직후인 약 38kya로 더 거슬러 올라갔습니다.[5][9] 발리니 등 2022년에 따르면, 서유라시아 계통의 분산 및 분할 패턴은 38,000년 전보다 이전이 아니었으며, 즐라티 쿤, 페 ș테라 쿠 오아제 및 바초 키로와 같은 더 오래된 초기 상부 구석기 유럽 표본은 서양 수렵채집인과는 관련이 없지만 고대 동유라시아인 또는 이 둘의 기저에 더 가깝다고 주장합니다. WHG는 고대 및 현대 중동 인구에 대해 그라베티아와 같은 초기 구석기 시대 유럽인들과 비교했을 때 더 높은 친화력을 보였습니다. 유럽의 고대 중동 개체군에 대한 친화력은 마지막 빙하기 이후에 증가했으며, 이는 WHG(Villabruna 또는 Oberkassel) 조상의 확장과 관련이 있습니다. 이르면 15,000년 전 WHG와 중동 인구 사이의 양방향 유전자 흐름에 대한 증거도 있습니다. WHG 관련 유적은 주로 C-F3393(특히 C-V20/C1a2 계통군)의 빈도가 낮은 인간 Y-염색체 하플로그룹 I-M170에 속했으며, 이는 코스텐키-14 및 숭어와 같은 초기 구석기 유럽 유적에서 일반적으로 발견되었습니다. 부계 하플로그룹 C-V20은 여전히 현대 스페인에 사는 남성들에게서 발견될 수 있으며, 이는 서유럽에서 이 혈통이 오랫동안 존재했음을 증명합니다. 그들의 미토콘드리아 염색체는 주로 하플로그룹 U5에 속했습니다.[11][12]

2023년 3월 네이처에 발표된 유전자 연구에서 저자들은 WHGs의 조상이 에피그라베티아 문화와 관련된 개체군이라는 것을 발견했으며, 이는 14년경 마그달레니아 문화와 관련된 개체군을 크게 대체했습니다.(막달레니아인들의 조상은 서부 그라베티아, 솔루트레아, 오리냐 문화와 관련된 집단이었습니다.)[11][13] 이 연구에서 WHG 조상은 'Oberkassel 조상'으로 이름이 바뀌었는데, 알프스 북쪽에서 처음 발견된 14,000년 된 두 명의 사람들이 Oberkassel의 이름에서 유래했습니다. Villabruna 조상(V ě stonice 클러스터와 관련된 계통과 Kostenki-14 및 Goyet Q116-1 개체의 조상인 계통 사이의 혼합으로 모델링됨)과 마지막 빙하 최대치 이전에 유럽에서 발견된 개체와 관련된 Goyet-Q2 조상으로 모델링될 수 있는 사람. 이 연구에 따르면 Oberkassel 군집의 모든 개체는 c. 75% Villabruna와 25% Goyet-Q2 조상 또는 c. 90% Villabruna와 10% Fournol 조상으로 모델링할 수 있습니다. 유럽 남서부의 그라베티아 문화와 관련된 개인에서 발견되는 고예 Q116-1 조상의 자매 계통으로 설명된 새로 확인된 군집.[11] 이 연구는 Oberkassel 조상이 대부분 알프스의 서쪽 주변에서 샘플링된 WHG 개체가 유전적으로 균질한 서유럽과 중앙 유럽 및 영국으로 확장되기 전에 이미 형성되었음을 시사합니다. 이는 고예-Q2 혈통을 가진 지역 주민들과의 반복적인 혼합 사건과 관련된 것으로 보이는 비야브루나와 오버카셀 혈통이 이베리아에 도착한 것과는 대조적입니다. 이는 초기 유럽 수렵-채취자들 사이에서 이전에 관찰된 특정 Y-DNA 하플로그룹 C1 계통군의 생존과 이 기간 동안 남서 유럽에서 상대적으로 더 높은 유전적 연속성을 시사합니다.[11]

WHG가 "당뇨병과 알츠하이머병의 위험 대립유전자"를 지니고 있다는 징후가 있습니다.[14]

다른 모집단과의 상호작용

WHG는 또한 초기 아나톨리아 농부들과 고대 북서 아프리카인들과 같은 유럽의 국경에 있는 인구들과 [16]동방 사냥꾼-채집꾼들과 같은 다른 유럽 집단들에 조상을 기여한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[17] WHG와 EHG의 관계는 아직 결정되지 않았습니다.[17] EHG는 WHG 관련 계통에서 25%에서 최대 91%에 이르는 다양한 정도의 조상을 도출하도록 모델링되었으며 나머지는 구석기 시대 시베리아(ANE) 및 아마도 코카서스 수렵 채집인의 유전자 흐름과 연결되어 있습니다. 스칸디나비아 헌터-채집인 (SHG)으로 알려진 또 다른 혈통은 EHG와 WHG가 섞여 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[a][19][20]

중석기 쿤다 문화권과 발트 동부의 나르바 문화권 사람들은 WHG와 EHG가 섞여 [21]있어 WHG와 가장 가까운 친화력을 보였습니다. 우크라이나 중석기 시대와 신석기 시대의 샘플은 WHG와 EHG 사이에 밀접하게 모여 있는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 이는 4,000년의 기간 동안 드네프르 래피드의 유전적 연속성을 시사합니다. 우크라이나 샘플은 모계 하플로그룹 U에만 속했으며, 이는 모든 유럽 수렵-채집 샘플의 약 80%에서 발견됩니다.[22]

발트해 동부의 피트콤웨어 문화(CCC) 사람들은 EHG와 밀접한 관련이 있었습니다.[23] 대부분의 WHG와 달리 발트해 동부의 WHG는 신석기 시대 동안 유럽 농부들의 혼합물을 받지 못했습니다. 따라서 발트해 동부의 현대 개체군은 유럽의 다른 어떤 개체군보다 더 많은 양의 WHG 조상을 가지고 있습니다.[21]

SHG에는 남쪽에서 스칸디나비아로 이동했을 가능성이 있는 WHG 성분과 나중에 노르웨이 해안을 따라 북동쪽에서 스칸디나비아로 이동한 EHG 성분이 혼합되어 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 이 가설은 서부 스칸디나비아와 북부 스칸디나비아에서 온 SHG가 동부 스칸디나비아에서 온 개인보다 WHG 조상(ca 51%)이 더 적었다는 증거에 의해 뒷받침됩니다. 스칸디나비아에 들어온 WHG들은 아렌스부르크 문화에 속했던 것으로 추정됩니다. EHG와 WHG는 SHG보다 색소침착을 유발하는 SLC45A2와 SLC24A5, 밝은 눈 색을 유발하는 OCA/Herc2의 대립유전자 빈도가 낮았습니다.[24]

서유럽, 중유럽, 발칸 반도의 상부 구석기 시대와 중석기 시대의 11개 WHG의 DNA를 Y-DNA 하플로 그룹과 mtDNA 하플로 그룹에 대해 분석했습니다. 분석 결과 WHG는 한때 서부 대서양 연안에서 남부 시칠리아, 동남부 발칸반도에 이르기까지 6천 년 이상 널리 분포되어 있었습니다.[25] 이 연구에는 또한 선사시대 동유럽의 많은 개체들에 대한 분석도 포함되었습니다. 37개의 샘플이 중석기와 신석기 우크라이나(기원전 9500~6000년)에서 수집되었습니다. 이들은 신석기 시대에 이 개체군의 WHG 조상이 증가했지만 EHG와 SHG의 중간체로 결정되었습니다. 이 개인들로부터 추출된 Y-DNA 샘플은 R 일배체형(특히 R1b1의 하위 분류) 및 I 일배체형(특히 I2의 하위 분류)에 독점적으로 속했습니다. mtDNA는 거의 전적으로 U(특히 U5 및 U4의 하위 분류)에 속했습니다.[25] 발트 동부의 쿤다 문화와 나르바 문화에 대부분 속해 있던 즈베이지니키 매장지의 개체들이 대거 분석되었습니다. 이 사람들은 초기 단계에서는 대부분 WHG 혈통이었지만 시간이 지남에 따라 EHG 혈통이 우세해졌습니다. 이 부위의 Y-DNA는 거의 독점적으로 하플로그룹 R1b1a1a 및 I2a1의 일배체형에 속했습니다. mtDNA는 하플로그룹 U(특히 U2, U4 및 U5의 하위 분기군)에만 속했습니다.[25] 발칸 반도의 철문 중석기 시대의 세 곳에서 40명의 개체도 분석했습니다. 이 사람들은 85% WHG와 15% EHG 혈통으로 추정되었습니다. 이 사이트의 수컷은 독점적인 하플로그룹 R1b1a 및 I(대부분 I2a의 하위 분기군) 일배체형을 가지고 있었습니다. mtDNA는 대부분 U(특히 U5 및 U4의 하위 분기군)에 속했습니다.[25] 발칸 신석기 시대 사람들은 98%의 아나톨리아 혈통과 2%의 WHG 혈통을 가지고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 칼콜리스틱에 의해, 쿠쿠텐의 사람들-트리필리아 문화는 EHG와 WHG의 중간인 약 20%의 수렵-채집 조상을 가지고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 구상 암포라 문화의 사람들은 약 25%의 WHG 조상을 가지고 있는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 이는 중앙 유럽의 중기 신석기 시대 그룹보다 상당히 높습니다.[25]

신석기시대 농부에 의한 대체

2014년의 획기적인 연구는 현대 유럽 계통에 대한 세 가지 주요 구성 요소의 기여를 처음으로 확인했습니다: WHG, 북유럽인의 경우 최대 50% 비율), 고대 북유라시아인(ANE, 후기 인도-유럽 확장과 관련된 상부 구석기 시대 시베리아인, 최대 20% 비율), 그리고 마지막으로 초기 유럽 농부들(EEF, 주로 근동 출신의 농업인들)은 약 8,000 BP에서 유럽으로 이주하여 현재 발트해 지역의 약 30%에서 지중해의 약 90%에 이르는 비율로 존재합니다. 초기 유럽 농부(EEF) 구성 요소는 독일 슈투트가르트의 리니어 도자기 문화 무덤에 7,000년 전에 묻힌 여성의 게놈을 기반으로 확인되었습니다.[27]

이 2014년 연구는 유럽 전역에서 WHG와 EEF 사이의 유전적 혼합에 대한 증거를 발견했으며, 지중해 유럽(특히 사르데냐, 시칠리아, 몰타 및 아슈케나지 유대인)에서 EEF의 가장 큰 기여를 했고, 북유럽과 바스크 사람들 사이에서 WHG의 가장 큰 기여를 했습니다.[28]

2014년부터 추가 연구를 통해 EEF와 WHG 사이의 이종교배에 대한 그림이 개선되었습니다. 2017년 헝가리, 독일 및 스페인의 찰콜리스틱 및 신석기 시대의 180개 고대 DNA 데이터 세트를 분석한 결과, 이종교배 기간이 길다는 증거가 발견되었습니다. 혼합은 지역 수렵-채집 개체군에서 지역적으로 발생하여 세 지역(독일, 이베리아 및 헝가리)의 개체군이 신석기 시대의 모든 단계에서 유전적으로 구별될 수 있었고 시간이 지남에 따라 WHG 조상의 비율이 점차 증가했습니다. 이것은 초기 농부들의 확장 이후에, 농업 인구를 균질화할 수 있을 정도의 실질적인 장거리 이동이 더 이상 없었고, 농업과 수렵채집 인구가 수세기 동안 나란히 존재했다는 것을 시사합니다. 기원전 5~4천년에 걸쳐 점진적인 혼합을 진행합니다(최초 접촉 시 단일 혼합 이벤트가 아닌).[29] 혼합 비율은 지리적으로 다양했습니다. 신석기 후기에 헝가리의 농부들의 WHG 혈통은 약 10%, 독일은 약 25%, 이베리아는 50%[30]까지 높았습니다.

이탈리아의 그로타 콘티넨자 유적을 분석한 결과, 기원전 10,000년에서 기원전 7000년 사이에 묻힌 6구의 유해 중 3구는 I2a-P214에 속했고, 모계 하플로그룹 U5b1과 U5b3의 2배에 달했습니다.[31][32] 기원전 6000년경, 이탈리아의 WHG는 유전적으로 거의 완전히 EEF(두 개의 G2a2)와 한 개의 하플로그룹 R1b로 대체되었지만, 이후 천년에 WHG 조상은 약간 증가했습니다.[33]

영국 제도의 신석기 시대 사람들은 이베리아와 중부 유럽 초기 및 중기 신석기 인구에 가까웠고, 나머지는 유럽 대륙의 WHG에서 온 것으로 모델화되었습니다. 그들은 그 후 영국 제도의 WHG 인구 대부분과 많이 섞이지 않고 대체했습니다.[34]

WHG는 유럽 전역의 신석기 EEF 그룹에 20-30%의 조상을 기여한 것으로 추정됩니다. 지역 병원체에 대한 특정 적응은 중석기 WHG 혼합물을 통해 신석기 EEF 개체군에 도입되었을 수 있습니다.[35]

덴마크의 중석기 수렵채집가들에 대한 연구에 따르면 이들은 동시대 서양 수렵채집가들과 관련이 있으며, 마그레모스, 콩게모스, 에르테뵈를 문화와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 그들은 "아나톨리아에서 유래한 조상을 가진 신석기 농부들이 도착할 때까지 현재까지 약 10,500년에서 5,900년 사이의 유전적 동질성"을 보여주었습니다. 신석기 시대로의 전환은 "매우 갑작스러웠고 지역 수렵 채집인들의 유전적 기여가 제한적인 개체군 전환을 초래했습니다. 이어지는 신석기 시대의 인구는 펀넬 비커 문화와 관련이 있습니다.[36]

신체외관

데이비드 라이히(David Reich)에 따르면, DNA 분석 결과 웨스턴 헌터 개더는 일반적으로 피부가 검고, 머리가 검고, 눈이 푸른 것으로 나타났습니다.[39] 어두운 피부는 비교적 최근의 아프리카 밖 기원(모든 호모 사피엔스 개체군은 처음에 어두운 피부를 가지고 있음) 때문인 반면, 파란 눈은 홍채 색소 침착을 유발하는 OCA2 유전자의 변화의 결과입니다.[40]

고고학자 Graeme Warren은 그들의 피부색이 올리브색에서 검은색까지 다양하다고 말했고, 그들이 지역적인 다양한 눈과 머리카락 색을 가졌을 것이라고 추측했습니다.[41] 이것은 먼 친척인 EHG(Eastern Hunter-Colterers)와 현저하게 다릅니다. EHG는 밝은 피부, 갈색 눈 또는 푸른 눈을 가지고 있으며 어두운 머리 또는 밝은 머리를 가지고 있다고 제안되었습니다.[42]

불완전한 SNP를 가진 두 개의 WHG 골격인 라 브라냐와 체다 맨은 피부가 어둡거나 검거나 검은색이었을 것으로 예측되는 반면, 완전한 SNP를 가진 다른 두 개의 WHG 골격인 "스벤"과 로슈부르 맨은 각각 피부가 어둡거나 중간에서 어두운 중간에서 어두운 중간까지였을 것으로 예측됩니다.[43][24][b] 스페인 생물학자 카를레스 랄루에자-폭스는 라 브라냐-1 개체가 "정확한 그늘은 알 수 없지만" 피부가 검다고 말했습니다.[45]

2020년 연구에 따르면, 청동기 시대의 웨스턴 스텝 허더와 함께 8500년에서 5000년 전에 서부 아나톨리아에서 초기 유럽 농부들(EEFs)이 도착하면서 유럽 인구가 피부와 머리카락이 더 밝은 쪽으로 빠르게 진화했습니다.[40] 수렵-채취자와 농업주의자 인구 사이의 혼합은 분명히 가끔 있었지만 광범위하지는 않았습니다.[46]

일부 저자들은 피부 색소 재건에 대해 주의를 표명했습니다. Quillen et al. (2019)은 일반적으로 체다 맨에 대한 "어두운 또는 어두운 색에서 검은색" 예측에 대한 연구를 포함하여 "중석기 동안 유럽의 많은 부분에서 밝은 피부색이 드물었다"는 것을 보여주는 연구를 인정합니다. 그러나 "현대 개체군에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 유전자좌를 사용한 중석기 및 신석기 색소 표현형의 재구성은 아직 조사되지 않은 다른 유전자좌도 표현형에 영향을 미쳤을 가능성이 있으므로 어느 정도 주의를 기울여 해석해야 합니다."[47]

체다 맨 프로젝트를 수행한 인디애나 대학교 퍼듀 대학교 인디애나폴리스의 유전학자 수잔 월시(Susan Walsh)는 "우리는 단지 그의 피부색을 알지 못한다"고 말했습니다.[48] 독일 생화학자 요하네스 크라우제는 서유럽 수렵채집꾼들의 피부색이 오늘날의 중앙 아프리카 사람들의 피부색과 더 비슷했는지, 아니면 아랍 지역 사람들의 피부색과 더 비슷했는지 알 수 없다고 말했습니다. 그들이 이후의 유럽인 집단에서 가벼운 피부를 담당하는 알려진 돌연변이를 가지고 있지 않다는 것은 확실할 뿐입니다.[49]

메모들

- ^ EHG(Eastern Hunter Gatherers)는 그들의 조상의 3/4을 ANE에서 유래합니다... 스칸디나비아 수렵채집인(SHG)은 EHG와 WHG가 혼합된 것이고, WHG는 EHG와 스위스의 상부 구석기 시대 비숑이 혼합된 것입니다.[18]

- ^ 이러한 예측은 중간 피부를 분류하기 위해 0.26의 낮은 민감도를 가진 36개의 신중하게 선택된 SNP 패널을 기반으로 하는 다항 로지스틱 회귀 모델을 사용하여 얻어졌습니다(흰 피부와 검은 피부의 경우 각각 0.99 및 0.90과 비교). 사용된 모델의 정확도는 "향후 GWAS를 통해 확인된 추가 SNP 예측 변수"를 통해 더욱 향상될 수 있습니다.[44]

참고문헌

- ^ Posth, Cosimo; Yu, He; Ghalichi, Ayshin (March 2023). "Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers". Nature. 615 (7950): 117–126. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..117P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9977688. PMID 36859578. S2CID 257259969.

- ^ a b Anthony 2019b, p. 28.

- ^ Kashuba 2019: "이전의 aDNA 연구는 초기 빙하기 유럽에서 세 가지 유전자 그룹의 존재를 시사합니다. 서부 수렵채집인(WHG), 동부 수렵채집인(EHG), 스칸디나비아 수렵채집인(SHG) 4. SHG는 WHG와 EHG의 혼합물로 모델링되었습니다."

- ^ Davy, Tom; Ju, Dan; Mathieson, Iain; Skoglund, Pontus (April 2023). "Hunter-gatherer admixture facilitated natural selection in Neolithic European farmers". Current Biology. 33 (7): 1365–1371.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.049. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 10153476. PMID 36963383.

- ^ a b c 라자리디스 2014.

- ^ 2015년 수학.

- ^ Haak 2015.

- ^ Fu, Qiaomei (2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. 534 (7606): 200–205. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. PMC 4943878. PMID 27135931.

Beginning with the Villabruna Cluster at least ~14,000 years ago, all European individuals analyzed show an affinity to the Near East. This correlates in time to the Bølling-Allerød interstadial, the first significant warming period after the Ice Age. Archaeologically, it correlates with cultural transitions within the Epigravettian in Southern Europe and the Magdalenian-to-Azilian transition in Western Europe. Thus, the appearance of the Villabruna Cluster may reflect migrations or population shifts within Europe at the end of the Ice Age, an observation that is also consistent with the evidence of turnover of mitochondrial DNA sequences at this time. One scenario that could explain these patterns is a population expansion from southeastern European or west Asian refugia after the Ice Age, drawing together the genetic ancestry of Europe and the Near East. Sixth, within the Villabruna Cluster, some, but not all, individuals have affinity to East Asians. An important direction for future work is to generate similar ancient DNA data from southeastern Europe and the Near East to arrive at a more complete picture of the Upper Paleolithic population history of western Eurasia

- ^ Sikora, Martin; Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Sousa, Vitor C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vinner, Lasse; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Renaud, Gabriel; Yang, Melinda A.; Fu, Qiaomei; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Giampoudakis, Konstantinos; Nogués-Bravo, David (June 2019). "The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene". Nature. 570 (7760): 182–188. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..182S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z. hdl:1887/3198847. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31168093. S2CID 174809069.

- ^ Vallini et al. 2022 (4 July 2022). "Genetics and Material Culture Support Repeated Expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a Population Hub Out of Africa". Retrieved 16 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 메인트: 숫자 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ a b c d e Posth, C., Yu, H., Ghalichi, A. (2023). "Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers". Nature. 615 (2 March 2023): 117–126. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..117P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0. PMC 9977688. PMID 36859578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Scozzari, Rosaria; Massaia, Andrea; D’Atanasio, Eugenia; Myres, Natalie M.; Perego, Ugo A.; Trombetta, Beniamino; Cruciani, Fulvio (7 November 2012). "Molecular Dissection of the Basal Clades in the Human Y Chromosome Phylogenetic Tree". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e49170. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749170S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049170. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3492319. PMID 23145109.

Through this analysis we identified a chromosome from southern Europe as a new deep branch within haplogroup C (C-V20 or C7, Figure S1). Previously, only a few examples of C chromosomes (only defined by the marker RPS4Y711) had been found in southern Europe [32], [33]. To improve our knowledge regarding the distribution of haplogroup C in Europe, we surveyed 1965 European subjects for the mutation RPS4Y711 and identified one additional haplogroup C chromosome from southern Europe, which has also been classified as C7 (data not shown).

- ^ "Scientists Sequence Genomes of Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers from Different Eurasian Cultures". Sci.News. 2 March 2023.

- ^ Irving-Pease, Evan K.; Refoyo-Martínez, Alba; Barrie, William; Ingason, Andrés; Pearson, Alice; Fischer, Anders; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Halgren, Alma S.; Macleod, Ruairidh; Demeter, Fabrice; Henriksen, Rasmus A.; Vimala, Tharsika; McColl, Hugh; Vaughn, Andrew H.; Speidel, Leo (January 2024). "The selection landscape and genetic legacy of ancient Eurasians". Nature. 625 (7994): 312–320. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06705-1. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10781624.

... whereas risk alleles for diabetes and Alzheimer's disease are enriched for Western hunter-gatherer ancestry.

- ^ Charlton, Sophy; Brace, Selina (November 2022). "Dual ancestries and ecologies of the Late Glacial Palaeolithic in Britain". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 6 (11): 1658–1668. Bibcode:2022NatEE...6.1658C. doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01883-z. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 9630104. PMID 36280785.

- ^ Simões, Luciana G.; Günther, Torsten; Martínez-Sánchez, Rafael M.; Vera-Rodríguez, Juan Carlos; Iriarte, Eneko; Rodríguez-Varela, Ricardo; Bokbot, Youssef; Valdiosera, Cristina; Jakobsson, Mattias (7 June 2023). "Northwest African Neolithic initiated by migrants from Iberia and Levant". Nature. 618 (7965): 550–556. Bibcode:2023Natur.618..550S. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06166-6. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10266975. PMID 37286608.

- ^ a b Lazaridis, Iosif (1 December 2018). "The evolutionary history of human populations in Europe". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Genetics of Human Origins. 53: 21–27. arXiv:1805.01579. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2018.06.007. ISSN 0959-437X. PMID 29960127. S2CID 19158377.

- ^ 라자리디스 2016.

- ^ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei; Mittnik, Alissa; Bánffy, Eszter; Economou, Christos; Francken, Michael (June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Sikora, Martin; Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Sousa, Vitor C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vinner, Lasse; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Renaud, Gabriel; Yang, Melinda A.; Fu, Qiaomei; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Giampoudakis, Konstantinos; Nogués-Bravo, David (June 2019). "The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene". Nature. 570 (7760): 182–188. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..182S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z. hdl:1887/3198847. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31168093. S2CID 174809069.

- ^ a b 미트닉 2018.

- ^ 존스 2017.

- ^ Saag 2017.

- ^ a b 귄터 2018.

- ^ a b c d e 2018년 수학.

- ^ Sikora M, Carpenter ML, Moreno-Estrada A, Henn BM, Underhill PA, Sánchez-Quinto F, et al. (May 2014). "Population genomic analysis of ancient and modern genomes yields new insights into the genetic ancestry of the Tyrolean Iceman and the genetic structure of Europe". PLOS Genetics. 10 (5): e1004353. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004353. PMC 4014435. PMID 24809476.

- ^ Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Mittnik, Alissa (September 2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

Most present-day Europeans derive from at least three highly differentiated populations: west European hunter-gatherers, who contributed ancestry to all Europeans but not to Near Easterners; ancient north Eurasians related to Upper Palaeolithic Siberians, who contributed to both Europeans and Near Easterners; and early European farmers, who were mainly of Near Eastern origin but also harboured west European hunter-gatherer related ancestry.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. (2014), 보충 정보, p. 113.

- ^ Lipson et al., "평행 고유전체 단면은 초기 유럽 농부들의 복잡한 유전적 역사를 보여줍니다", Nature 551, 368–372 (2017년 11월 16일) doi:10.1038/nature 24476.

- ^ Lipson et al. (2017), Fig. 2.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, 표 2 샘플 정보, 4-6행

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 2, Fig. 1.

- ^ Brace, Selina; Diekmann, Yoan; Booth, Thomas J.; van Dorp, Lucy; Faltyskova, Zuzana; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Ferry, Matthew; Michel, Megan; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Stewardson, Kristin; Martiniano, Rui; Walsh, Susan; Kayser, Manfred; Charlton, Sophy; Hellenthal, Garrett; Armit, Ian; Schulting, Rick; Craig, Oliver E.; Sheridan, Alison; Parker Pearson, Mike; Stringer, Chris; Reich, David; Thomas, Mark G.; Barnes, Ian (2019). "Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (5): 765–771. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3..765B. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 6520225. PMID 30988490.

- ^ Davy, Tom; Ju, Dan; Mathieson, Iain; Skoglund, Pontus (April 2023). "Hunter-gatherer admixture facilitated natural selection in Neolithic European farmers". Current Biology. 33 (7): 1365–1371.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.049. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 10153476. PMID 36963383.

- ^ Allentoft, Morten E.; Sikora, Martin; Fischer, Anders; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Ingason, Andrés; Macleod, Ruairidh; Rosengren, Anders; Schulz Paulsson, Bettina; Jørkov, Marie Louise Schjellerup; Novosolov, Maria; Stenderup, Jesper; Price, T. Douglas; Fischer Mortensen, Morten; Nielsen, Anne Birgitte; Ulfeldt Hede, Mikkel (10 January 2024). "100 ancient genomes show repeated population turnovers in Neolithic Denmark". Nature. 625 (7994): 329–337. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06862-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10781617.

- ^ Conneller, Chantal (29 November 2021). The Mesolithic in Britain: Landscape and Society in Times of Change. Routledge. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-000-47515-9.

- ^ 자연사박물관 재건축 관련 상세내용:

- ^ Reich, David (2018). Who We Are and How We Hot Here : Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (First ed.). New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1101870334. "고대 DNA 데이터를 분석한 결과, 약 8천년 전 서유럽의 수렵채집인들은 파란 눈을 가졌지만 어두운 피부와 검은 머리를 가졌는데, 이는 오늘날 보기 드문 조합입니다."

- ^ a b c Hanel, Andrea; Carlberg, Carsten (September 2020). "Skin colour and vitamin D: An update". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (9): 867. doi:10.1111/exd.14142. ISSN 0906-6705. PMID 32621306. S2CID 220335539.

Homo sapiens arrrived in Europe from Near East some 42 000 years ago. Like in their African origin, these humans had dark skin but due to variations of their OCA2 gene (causing iris depigmentation) many of them had blue eyes" (...) "southern and central Europe, where they [light skin alleles] were introduced by farmers from western Anatolia expanding 8500 to 5000 years ago. This was the start of the Neolithic revolution in these regions, characterized by a more sedentary lifestyle and the domestication of certain animal and plant species. (...) "The rapid increase in population size due to the Neolithic revolution, such as the use of milk products as food source for adults and the rise of agriculture, as well as the massive spread of Yamnaya pastoralists likely caused the rapid selective sweep in European populations towards light skin and hair

- ^ Warren, Graeme (2021). Hunter-Gatherer Ireland: making connections in an island world. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1789256840. "예를 들어, WHG는 올리브에서 갈색, 검은색에 이르는 피부 색소를 가지고 있으며 파란색 또는 청록색 눈을 가지고 있습니다. 유럽의 일부 지역에서는 이것이 금발과도 관련이 있을 수 있습니다."

- ^ Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation S8 Text. Functional variation in ancient samples., doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703.s013

- ^ Brace, Selina; Diekmann, Yoan; Booth, Thomas J.; Faltyskova, Zuzana; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Ferry, Matthew; Michel, Megan; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Stewardson, Kristin; Walsh, Susan; Kayser, Manfred; Schulting, Rick; Craig, Oliver E.; Sheridan, Alison; Pearson, Mike Parker; Stringer, Chris; Reich, David; Thomas, Mark G.; Barnes, Ian (2019), "Population Replacement in Early Neolithic Britain", Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3 (5): 765–771, Bibcode:2019NatEE...3..765B, doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9, PMC 6520225, PMID 30988490 보충 자료. 22페이지: "두 개의 WHG(스페인 북부에서 온 체다 맨과 라 브라냐)는 피부가 어둡거나 검거나 검게 변한 것으로 예측되는 반면, 한 WHG(룩셈부르그에서 온 Loschbour44)는 중간 피부를 가지고 있는 것으로 예측되지만, 우리는 색소 침착 특성에서 잠재적인 시간적 및/또는 지리적 변화를 발견합니다. 다양한 피부 색소 수준이 WHG에서 적어도 약 8kBP만큼 공존했음을 시사합니다. 스벤은 유럽인들의 일반적으로 밝은 피부와 관련된 대립유전자들이 ANF에 의해 북서유럽으로 유입되었다는 현재의 가설에 따라 어두운 피부에서 중간 피부를 가졌을 것으로 예측되었습니다."

- ^ Walsh, Susan (2017). "Global skin colour prediction from DNA". Human Genetics. 136 (7): 847–863. doi:10.1007/s00439-017-1808-5. PMC 5487854. PMID 28500464.

- ^ "Dark Skin, Blue Eyes: Genes Paint 7,000-Year-Old European's Picture". NBC News. 26 January 2014.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (12 May 2022). "Ancient DNA maps 'dawn of farming'". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01322-w. PMID 35552521. S2CID 248765487.

Once established in Anatolia, Excoffier's team found, early farming populations moved west into Europe in a stepping-stone-like fashion, beginning around 8,000 years ago. They mixed occasionally — but not extensively — with local hunter-gatherers.

- ^ Quillen, Ellen (2019). "Shades of complexity: New perspectives on the evolution and genetic architecture of human skin". American Journal of Biological Anthropology. 168 (S67): 4–26. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23737. PMID 30408154. S2CID 53237190.

Their analyses suggest that the skin color of both individuals was likely dark, with that of Mesolithic Cheddar Man predicted to be "dark or dark to black". These findings suggest that lighter skin color was uncommon across much of Europe during the Mesolithic. This is not, however, in conflict with the date estimates of <20 kya above, which addresses the onset of selection and not time of fixation of favored alleles (Beleza et al., 2013; Beleza, Johnson, et al., 2013). While ancient genome studies predict generally darker skin color among Mesolithic Europeans, derived alleles at rs1426654 and rs16891982 were segregating in European populations during the Mesolithic (González-Fortes et al., 2017; Günther et al., 2018; Mittnik et al., 2018), suggesting that phenotypic variation due to these loci was likely present by this time. However, reconstructions of Mesolithic and Neolithic pigmentation phenotype using loci common in modern populations should be interpreted with some caution, as it is possible that other as yet unexamined loci may have also influenced phenotype.

- ^ "Ancient 'dark skinned' Cheddar man find may not be true". New Scientist. 21 February 2018.

- ^ Krause, Johannes (2021). A Short History of Humanity A New History of Old Europe. l: Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780593229446.

서지학

- Anthony, David W. (2019b). "Ancient DNA, Mating Networks, and the Anatolian Split". In Serangeli, Matilde; Olander, Thomas (eds.). Dispersals and Diversification: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Early Stages of Indo-European. BRILL. pp. 21–54. ISBN 978-9004416192.

- Antonio, Margaret L.; et al. (8 November 2019). "Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 366 (6466): 708–714. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..708A. doi:10.1126/science.aay6826. PMC 7093155. PMID 31699931.

- Günther, Thorsten (1 January 2018). "Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation". PLOS Biology. PLOS. 16 (1): e2003703. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703. PMC 5760011. PMID 29315301.

- Haak, Wolfgang (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Jones, Eppie R. (20 February 2017). "The Neolithic Transition in the Baltic Was Not Driven by Admixture with Early European Farmers". Current Biology. Cell Press. 27 (4): 576–582. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.060. PMC 5321670. PMID 28162894.

- Kashuba, Natalija (15 May 2019). "Ancient DNA from mastics solidifies connection between material culture and genetics of mesolithic hunter–gatherers in Scandinavia". Communications Biology. Nature Research. 2 (105): 185. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0399-1. PMC 6520363. PMID 31123709.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (17 September 2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. Nature Research. 513 (7518): 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. hdl:11336/30563. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (25 July 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. Nature Research. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Mathieson, Iain (23 November 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. Nature Research. 528 (7583): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Mathieson, Iain (21 February 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Mittnik, Alisa (30 January 2018). "The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 16 (1): 442. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..442M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02825-9. PMC 5789860. PMID 29382937.

- Saag, Lehti (24 July 2017). "Extensive Farming in Estonia Started through a Sex-Biased Migration from the Steppe". Current Biology. Cell Press. 27 (14): 2185–2193. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.022. PMID 28712569.

추가읽기

- Anthony, David (Spring–Summer 2019). "Archaeology, Genetics, and Language in the Steppes: A Comment on Bomhard". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 47 (1–2). Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (December 2018). "The evolutionary history of human populations in Europe". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Elsevier. 53: 21–27. arXiv:1805.01579. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2018.06.007. PMID 29960127. S2CID 19158377. Retrieved 15 July 2020.