중세 온난기

Medieval Warm Period

중세 기후 최적기 또는 중세 기후 이상기로도 알려진 중세 온난기(MWP)는 950년부터 1250년까지 지속된 북대서양 지역의 따뜻한 기후였습니다.[2] 기후 대리 기록에 따르면 지역에 따라 최고 기온이 다른 시간대에 발생했으며, 이는 MWP가 전 세계적으로 균일한 이벤트가 아니었음을 나타냅니다.[3] 기온 이외의 기후 영향도 중요하다는 점을 강조하기 위해 MWP를 중세 기후 변칙이라고 부르는 이들도 있습니다.[4][5]

MWP는 북대서양과 다른 지역에서 지역적으로 더 추운 시기에 이어 때때로 소빙하기(Little Ice Age, LIA)라고 불립니다.

MWP의 가능한 원인으로는 태양 활동의 증가, 화산 활동의 감소, 해양 순환의 변화 등이 있습니다.[6] 모델링 증거에 따르면 자연 변동성은 MWP를 설명하기에 그 자체로 충분하지 않으며 외부의 강제력이 원인 중 하나여야 합니다.[7]

조사.

MWP는 일반적으로 유럽 중세 시대인 950년에서 1250년 사이에 발생한 것으로 생각됩니다.[2] 일부 연구자들은 MWP를 두 단계로 나눕니다: 서기 450년경에 시작하여 900년경에 끝난 MWP-I와 서기 1000년에서 1300년까지 지속된 MWP-II; MWP-I는 초기 중세 온난기라고 불리는 반면 MWP-II는 전통적인 중세 온난기라고 불립니다.[8] 1965년 최초의 고기후학자 중 한 명인 휴버트 램은 식물학, 역사 문서 연구 및 기상학의 데이터를 기반으로 1200년경과 1600년경 영국의 우세한 기온과 강우량을 나타내는 기록과 결합한 연구를 발표했습니다. 그는 "서기 1000년에서 1200년 사이에 몇 세기 동안 지속된 세계의 많은 지역의 현저하게 따뜻한 기후를 가리키는 증거들이 조사의 많은 분야에서 축적되어 왔고, 그 후 1500년에서 1700년 사이에 마지막 빙하기가 발생한 이래로 가장 추운 단계까지 온도 수준의 감소가 뒤따랐습니다"라고 제안했습니다.[9]

따뜻한 기온의 시대는 중세 온난기와 그 이후의 추운 시기인 소빙하기로 알려지게 되었습니다. 그러나 MWP가 세계적인 행사라는 견해에 다른 연구자들은 이의를 제기했습니다. 1990년 IPCC 제1차 평가 보고서는 "서기 1000년경의 중세 온난기(지구적이지 않았을 수도 있음)와 19세기 중후반에 끝난 소빙하기"에 대해 논의했습니다. 이 보고서는 "10세기 후반에서 13세기 초반(서기 950~1250년경)의 기온은 서유럽, 아이슬란드, 그린란드에서 유난히 따뜻했던 것으로 보인다"고 밝혔습니다.[10] 2001년의 IPCC 제3차 평가 보고서는 새로운 연구를 요약했습니다: "증거는 이 기간 동안 비정상적인 추위나 따뜻함의 전 세계적으로 동기화된 기간을 지원하지 않습니다. 그리고 '소빙하기'와 '중세 온난기'라는 전통적인 용어는 주로 지난 세기의 반구 또는 지구 평균 기온 변화의 북반구 동향을 설명하는 데 기록되어 있습니다."[11]

얼음 핵, 나무 고리, 호수 퇴적물에서 가져온 지구 온도 기록은 지구가 20세기 초와 중반보다 지구가 약간 더 차가웠을 수 있음을 보여주었습니다([12][13]0.03 °C).

지난 수세기 동안 지역별 기후 재구성을 개발한 고생대 기후학자들은 전통적으로 가장 추운 구간을 "LIA"라고 부르고 가장 따뜻한 구간을 "MWP"라고 부릅니다.[12][14] 다른 사람들은 협약을 따르고, "LIA" 또는 "MWP" 기간에 중요한 기후 이벤트가 발견되면, 그들은 그 기간에 그들의 이벤트를 연관시킵니다. 따라서 일부 "MWP" 사건은 엄격히 따뜻한 사건이 아닌 습한 사건 또는 추운 사건이며, 특히 북대서양의 기후 패턴과 반대되는 기후 패턴이 관찰되었습니다.

중세 온난기의 지구 기후

MWP의 성격과 범위는 세계적인 행사인지 지역적인 행사인지에 대한 오랜 논란으로 특징지어졌습니다.[15][16] 2019년 Pages-2k 컨소시엄은 확장된 프록시 데이터 세트를 [17]사용하여 중세 기후 변칙이 전 세계적으로 동기화된 이벤트가 아님을 확인했습니다. MWP 내에서 가장 따뜻한 51년 기간은 다른 지역에서 동시에 발생하지 않았습니다. 그들은 이해를 돕기 위해 산업화 이전 공통 시대의 기후 변동성에 대한 전 지구적 틀 대신 지역적 틀을 주장합니다.[18]

북대서양

로이드 디 1996년 Keigwin이 사르가소 해의 해양 퇴적물에서 얻은 방사성 탄소 연대 측정 상자 코어 데이터를 연구한 결과 해수면 온도는 약 400년 전, 리아(IA) 때, 그리고 1700년 전에는 약 1°C(1.8°F) 더 낮았고, MWP 때는 약 1°C 더 따뜻했습니다.[19]

Mann 등은 플로리다에서 뉴잉글랜드에 이르는 푸에르토리코, 걸프 연안, 대서양 연안의 퇴적물 샘플을 사용했습니다. (2009)는 MWP 동안 북대서양 열대성 저기압 활동의 정점을 발견했으며, 그 후 활동이 소강상태를 보였습니다.[20]

아이슬란드

아이슬란드는 항해와 농사를 짓기에 충분히 따뜻하다고 믿어졌던 시기인 약 865년에서 930년 사이에 처음 정착했습니다.[21][22] 패터슨 등은 해양 코어의 회수 및 동위원소 분석과 아이슬란드의 연체동물 성장 패턴 조사를 통해 안정적인 산소(δ O) 및 탄소(δ C) 동위원소 기록을 로마 온난기에서 MWP 및 LIA까지 10년 해상도로 재구성했습니다. 패터슨(Patterson) 등은 여름 기온이 높게 유지되었지만 아이슬란드의 초기 정착 이후 겨울 기온이 낮아졌다고 결론 내렸습니다.[23]

그린란드

2009년 Mann 등의 연구에서는 MWP 기간 동안 그린란드 남부와 북미 일부 지역에서 1961-1990년 수준을 초과하는 따뜻함을 발견했으며, 이 연구는 950년에서 1250년으로 정의하고 일부 지역에서는 1990-2010년 기간의 온도를 초과하는 따뜻함을 발견했습니다. 북반구의 대부분은 리아(IA) 기간 동안 상당한 냉각을 보였는데, 이 연구는 1400년에서 1700년으로 정의했지만, 래브라도(Labrador)와 미국의 고립된 지역은 1961-1990년 기간만큼 따뜻했던 것으로 나타났습니다.[2] MWP의 그린란드 겨울 산소 동위원소 데이터는 북대서양 진동(NAO)과 강한 상관관계를 보여줍니다.[24]

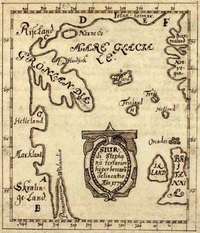

아메리카 대륙의 북유럽 식민지화는 따뜻한 시기와 관련이 있습니다.[25] 일반적인 이론은 북유럽 사람들이 빙하가 없는 바다를 이용하여 그린란드의 지역과 최북단의 다른 외부 땅을 식민지로 삼았다는 것입니다.[26] 하지만, 컬럼비아 대학의 한 연구는 그린란드가 더 따뜻한 날씨에 식민지화 된 것이 아니라, 사실 온난화 효과는 아주 잠깐 동안만 지속되었다고 시사합니다.[27] c. 서기 1000년, 바이킹족이 뉴펀들랜드로 여행하고 그곳에 단명한 전초기지를 세우기에 충분할 정도로 기후는 따뜻했습니다.[28]

985년쯤, 바이킹들은 그린란드의 남쪽 끝 근처에 동부와 서부 정착촌을 세웠습니다. 식민지 초기에, 그들은 소, 양, 염소를 길렀고, 그들의 식단의 약 4분의 1은 해산물을 사용했습니다. 1250년 무렵 기후가 점점 더 추워지고 폭풍우가 몰아친 후, 그들의 식단은 꾸준히 해양 쪽으로 이동했습니다. 1300년경, 바다표범 사냥은 그들의 먹이의 4분의 3 이상을 제공했습니다.

1350년까지 그들의 수출에 대한 수요가 줄었고 유럽과의 무역은 감소했습니다. 정착지의 마지막 문서는 1412년에 작성되었으며, 그 후 수십 년 동안 남아있는 유럽인들은 주로 스칸디나비아 국가의 농장 가용성 증가와 같은 경제적 요인에 의해 발생한 점진적인 철수로 보이는 것을 남겼습니다.[29]

유럽

MWP 기간 동안 남유럽의 상당한 빙하 후퇴를 경험했습니다. 몇몇 더 작은 빙하들이 완전한 빙하 제거를 경험했지만, 그 지역의 더 큰 빙하들은 살아남았고 이제 그 지역의 기후 역사에 대한 통찰력을 제공합니다.[30] 온난화로 인한 빙하 용해 외에도 퇴적 기록에 따르면 동유럽의 MWP와 일치하는 홍수가 증가한 기간이 있으며, 이는 긍정적인 단계의 NAO에서 강수가 증가했기 때문입니다.[31] 기후 변화의 다른 영향은 풍경의 변화와 같이 덜 명백할 수 있습니다. MWP 이전에 사르데냐 서부의 해안 지역은 로마인들에 의해 버려졌습니다. 해안 지역은 MWP 기간 동안 인구의 영향과 높은 지위 없이 석호로 실질적으로 확장될 수 있었습니다. 인류가 그 지역으로 돌아왔을 때, 그들은 기후 변화로 인해 변경된 땅을 만났고 항구를 다시 설립해야 했습니다.[32]

기타지역

북아메리카

체서피크 만(현재 미국 메릴랜드와 버지니아 주)에서 연구원들은 MWP(약 950–1250)와 소빙하기(약 1400–1700) 동안 큰 온도 이동(그 당시의 평균 온도에서 변화)을 발견했습니다. 아마도 북대서양 열염기 순환의 강도 변화와 관련이 있을 것입니다.[33] 허드슨 계곡 하류의 피어몬트 습지의 퇴적물은 800에서 1300 사이의 건조한 MWP를 보여줍니다.[34] 코네티컷 주의 해먹 강 습지에서는 해수면이 높아져 소금 습지가 현재보다 서쪽으로 15km 더 확장되었습니다.[35]

장기화된 가뭄은 현재 미국 서부의 많은 지역, 특히 캘리포니아 동부와 그레이트 베이슨 서부에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[12][36] 알래스카는 1–300, 850–1200, 그리고 1800년 이후로 비슷한 따뜻함을 경험했습니다.[37] 북미의 MWP에 대한 지식은 특히 미국 서부의 건조한 지역에서 특정 북미 원주민 거주지의 점유 기간을 측정하는 데 유용했습니다.[38][39] 건조는 MWP 기간 동안 미국 남동부에서 다음 리아보다 더 많이 발생했지만 통계적으로 유의하지 않을 수 있습니다.[40] MWP의 가뭄은 카호키아와 같은 미국 동부의 북미 원주민 거주지에도 영향을 미쳤을 수 있습니다.[41][42] 보다 최근의 고고학적 연구에 대한 검토는 특이한 문화적 변화의 징후에 대한 탐색이 넓어짐에 따라 (폭력 및 건강 문제와 같은) 초기 패턴 중 일부는 이전에 생각되었던 것보다 더 복잡하고 지역적으로 다양한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 정착 차질, 장거리 교역 악화, 인구 이동 등 다른 패턴도 더욱 확증되었습니다.[43]

아프리카

적도 동부 아프리카의 기후는 오늘날보다 건조하고 상대적으로 습한 기후를 번갈아 보여주고 있습니다. 기후는 MWP (1000–1270) 기간 동안 더 건조했습니다.[44] 아프리카 연안에서 MWP에서 LIA로 전환하는 동안 카나리아 제도 주민의 뼈를 동위원소로 분석한 결과 이 지역은 5°C의 대기 온도 감소를 경험한 것으로 나타났습니다. 이 기간 동안 주민들의 식단은 눈에 띄게 변하지 않았으며, 이는 그들이 기후 변화에 현저하게 탄력적임을 시사합니다.[45]

남극대륙

MWP가 남대서양에서 시작된 것은 MWP가 북대서양에서 시작된 것보다 약 150년 늦었습니다.[46] 남극 반도에 있는 동부 브랜스필드 분지의 퇴적물 핵은 리아 강과 MWP의 기후 현상을 모두 보존하고 있습니다. 저자들은 "후기 홀로세 기록은 리아(IA)와 중세 온난기(MWP)의 신빙하 현상을 분명히 확인한다"고 언급했습니다.[47] 남극 지역 중에는 이례적으로 추운 곳도 있었지만, 1000~1200년 사이에 이례적으로 따뜻한 곳도 있었습니다.[48]

태평양

열대 태평양의 산호는 비교적 시원하고 건조한 상태가 천년 초기에 지속되었을 수 있음을 시사하며, 이는 엘니뇨-남방 진동 패턴의 라니냐와 유사한 구성과 일치합니다.[49]

2013년 미국 3개 대학의 연구 결과가 사이언스지에 발표되었으며, 태평양의 수온은 MWP 기간 동안 LIA 기간보다 0.9도 더 따뜻했고, 연구 전 수십 년보다 0.65도 더 따뜻했습니다.[50]

남아메리카

MWP는 1500년 된 호수 바닥 퇴적물 코어와 [51]에콰도르 동부 코르디예라에서 발견되었습니다.[52]

얼음 코어를 기반으로 한 재구성은 MWP가 약 1050년에서 1300년 사이의 열대 남아메리카에서 구별될 수 있다는 것을 발견했고 15세기에 LIA에 의해 추적되었습니다. 최고 기온은 1600년의 연구 기간 동안 이 지역에서 전례가 없었던 20세기 후반 수준으로 상승하지 않았습니다.[53]

동아시아

Ge et al. 은 지난 2000년 동안 중국의 기온을 연구한 결과 16세기 이전에는 불확실성이 높았지만 지난 500년 동안에는 1620년대–1710년대와 1800년대–1860년대의 두 추운 시기와 20세기 온난화로 강조된 양호한 일관성을 발견했습니다. 그들은 또한 10세기부터 14세기까지의 일부 지역의 온난화가 지난 500년 내에 전례가 없었던 20세기의 지난 수십 년간의 온난화와 그 규모가 비슷할 수도 있다는 것을 발견했습니다.[54] 일반적으로 중국에서는 기온에 대한 다중 프록시 데이터를 사용하여 MWP와 일치하는 온난화 기간이 확인되었습니다. 하지만, 온난화는 중국 전역에서 일관성이 없었습니다. MWP에서 리아에 이르는 상당한 온도 변화는 중국 북동부와 중부 동부에서는 발견되었지만 중국 북서부와 티베트 고원에서는 발견되지 않았습니다.[55] MWP 기간 동안 동아시아 여름 몬순(EASM)은 지난 천[56] 년 동안 가장 강력했고 엘니뇨 남방 진동(ENSO)에 매우 민감했습니다.[57] 무우스 사막은 MWP에서 수분이 증가하는 것을 목격합니다.[58] 중국 남동부의 이탄지에서 나온 이탄 코어는 EASM과 ENSO의 변화가 MWP 기간 동안 이 지역의 강수량 증가에 책임이 있음을 시사합니다.[59] 그러나 중국 남부의 다른 지역은 MWP 기간 동안 건조하고 가습하지 않는 것으로 나타나 MWP의 영향이 공간적으로 매우 이질적임을 보여줍니다.[60] 모델링 증거에 따르면 MWP 기간 동안 EASM 강도는 초여름에는 낮았지만 늦여름에는 매우 높았습니다.[61]

러시아 극동 지역에서는 MWP 기간 동안 대륙 지역에 심각한 홍수가 발생한 반면 인근 섬에는 강수량이 적어 이탄지가 감소했습니다. 이 지역의 꽃가루 데이터는 활엽수가 증가하고 침엽수림이 감소하면서 따뜻한 기후 식생이 확장되고 있음을 나타냅니다.[62]

일본 중부 나카츠나 호수의 퇴적물을 조사한 Adhikari와 Kumon(2001)은 MWP에 해당하는 900에서 1200 사이의 따뜻한 기간과 3개의 시원한 단계에 해당하는 것을 발견했으며, 그 중 2개는 LIA와 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[63] 일본 동북부의 다른 연구에 따르면 750에서 1200 사이의 따뜻하고 습한 간격과 1에서 750 사이의 추운 간격과 건조한 간격이 두 번 있었습니다.[64]

남아시아

또한 MWP 기간 동안 인도 여름 몬순(ISM)은 대서양 다지각 진동(AMO)으로 온도가 변화하면서 강화되어 [65]인도에 더 많은 강수량을 가져왔습니다.[66] 히마찰 프라데시주 라홀의 식생 기록에 따르면 따뜻하고 습한 MWP는 1,158에서 647 BP로 확인됩니다.[67] MWP와 날짜가 일치하는 마디아 프라데시의 꽃가루는 몬순 강수량 증가에 대한 추가적인 직접적인 증거를 제공합니다.[68] 케랄라의 푸코드 호수에서 나온 멀티 프록시 기록도 MWP의 따뜻함을 반영합니다.[69]

중동

강한 몬순으로 인해 아라비아 해의 해수면 온도가 MWP 기간 동안 증가했습니다.[70] MWP 기간 동안 아라비아해는 생물학적 생산성이 높아졌습니다.[71] 오늘날 이미 극도로 건조했던 아라비아 반도는 MWP 기간 동안 더 건조했습니다. 이 과건조 기간이 종료된 기원전 660년경까지 장기간의 가뭄이 아라비아 기후의 주요 요인이었습니다.[72]

오세아니아

MWP와 LIA 모두에 대한 호주의 데이터가 극도로 부족합니다. 그러나 9세기와 10세기 동안 영구적으로 가득 찬 에어[73] 호수에 대한 파도로 만들어진 홑겹의 테라스의 증거는 라니냐와 같은 구성과 일치하지만, 데이터는 호수 수준이 매년 어떻게 변했는지 또는 호주의 다른 곳의 기후 조건이 어땠는지를 보여주기에 충분하지 않습니다.

1979년 와이카토 대학의 한 연구는 "뉴질랜드 동굴(40.67°S, 172.43°E)에서 발견된 석순을 통해 O/16O 프로파일에서 도출된 온도는 중세 온난기가 AD 1050년에서 1400년 사이에 발생했으며 현재의 온난기보다 0.75°C 더 따뜻했음을 시사한다"고 밝혔습니다.[74] 뉴질랜드의 더 많은 증거는 1100년의 나무 고리 기록에서 나온 것입니다.[75]

참고 항목

- 고전적인 마야 붕괴 – 중세 온난기와 동시에 발생하며 수십 년 동안 계속된 가뭄으로 특징지어집니다.

- 백악기 열 최대 – 약 9천만 년 전에 최고조에 달했던 기후 온난화 기간

- IPCC 보고서의 중세 온난기와 소빙하기에 관한 기술

- 역사 기후학

- 하키 스틱 그래프(지구 온도) – 기후 과학 그래프

- 홀로세 기후 최적 – 약 9,000~5,000년 전 지구 온난기

- 후기 골동품 소빙기 – 북반구 냉각기

- 고생대 기후학 – 고대 기후의 변화에 관한 연구

참고문헌

- ^ Hawkins, Ed (January 30, 2020). "2019 years". climate-lab-book.ac.uk. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. ("데이터는 현대 시대가 과거에 일어난 것과 매우 다르다는 것을 보여줍니다. 종종 인용되는 중세 온난기와 소빙하기는 실제 현상이지만 최근의 변화에 비하면 작습니다.")

- ^ a b c Mann, M. E.; Zhang, Z.; Rutherford, S.; et al. (2009). "Global Signatures and Dynamical Origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly" (PDF). Science. 326 (5957): 1256–60. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1256M. doi:10.1126/science.1177303. PMID 19965474. S2CID 18655276.

- ^ Solomon, Susan Snell; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). "6.6 The Last 2,000 Years". Climate change 2007: the physical science basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. ISBN 978-0-521-70596-7.Solomon, Susan Snell; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). "6.6 The Last 2,000 Years". Climate change 2007: the physical science basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. ISBN 978-0-521-70596-7.

{{cite book}}CS1 메인트: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) Box 6.4 Wayback Machine에서 보관된 2015-03-28 - ^ Bradley, Raymond S. (2003). "Climate of the Last Millennium" (PDF). Climate System Research Center.

- ^ Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy (1971). Times of Feast, Times of Famine: a History of Climate Since the Year 1000. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-52122-6.[페이지 필요]

- ^ "How does the Medieval Warm Period compare to current global temperatures?". SkepticalScience. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ Hunt, B. G. (11 May 2006). "The Medieval Warm Period, the Little Ice Age and simulated climatic variability". Climate Dynamics. 27 (7–8): 677–694. doi:10.1007/s00382-006-0153-5. ISSN 0930-7575. S2CID 128890550. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Cronin, T.M; Dwyer, G.S; Kamiya, T; Schwede, S; Willard, D.A (March 2003). "Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age and 20th century temperature variability from Chesapeake Bay". Global and Planetary Change. 36 (1–2): 17–29. doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(02)00161-3. hdl:10161/6578. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Lamb, H.H. (1965). "The early medieval warm epoch and its sequel". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 1: 13–37. Bibcode:1965PPP.....1...13L. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(65)90004-0.

- ^ IPCC 1차 평가 보고서 워킹 그룹 1 보고서, 7장, 경영 요약 p. 199, 과거 5,000,000년의 기후 p. 202.

- ^ Folland, C.K.; Karl, T.R.; Christy, J.R.; et al. (2001). "2.3.3 Was there a "Little Ice Age" and a "Medieval Warm Period"?"". In Houghton, J.T.; Ding, Y.; Griggs, D.J.; Noguer, M.; van der Linden; Dai; Maskell; Johnson (eds.). Working Group I: The Scientific Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Climate Change 2001. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 881. ISBN 978-0-521-80767-8.

- ^ a b c Bradley, R. S.; Hughes, MK; Diaz, HF (2003). "CLIMATE CHANGE: Climate in Medieval Time". Science. 302 (5644): 404–5. doi:10.1126/science.1090372. PMID 14563996. S2CID 130306134.

- ^ Crowley, Thomas J.; Lowery, Thomas S. (2000). "How Warm Was the Medieval Warm Period?". Ambio: A Journal of the Human Environment. 29: 51–54. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-29.1.51. S2CID 86527510.

- ^ Jones, P. D.; Mann, M. E. (2004). "Climate over past millennia". Reviews of Geophysics. 42 (2): 2002. Bibcode:2004RvGeo..42.2002J. doi:10.1029/2003RG000143.

- ^ Broecker, Wallace S. (23 February 2001). "Was the Medieval Warm Period Global?". Science. 291 (5508): 1497–1499. doi:10.1126/science.291.5508.1497. PMID 11234078. S2CID 17674208. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Malcolm K.; Diaz, Henry F. (March 1994). "Was there a 'medieval warm period', and if so, where and when?". Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 109–142. Bibcode:1994ClCh...26..109H. doi:10.1007/BF01092410. S2CID 128680153. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Emile-Geay, Julien; McKay, Nicholas P.; Kaufman, Darrell S.; von Gunten, Lucien; Wang, Jianghao; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Abram, Nerilie J.; Addison, Jason A.; Curran, Mark A.J.; Evans, Michael N.; Henley, Benjamin J. (2017-07-11). "A global multiproxy database for temperature reconstructions of the Common Era". Scientific Data. 4 (1): 170088. Bibcode:2017NatSD...470088E. doi:10.1038/sdata.2017.88. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 5505119. PMID 28696409.

- ^ Neukom, Raphael; Steiger, Nathan; Gómez-Navarro, Juan José; Wang, Jianghao; Werner, Johannes P. (2019). "No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era". Nature. 571 (7766): 550–554. Bibcode:2019Natur.571..550N. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1401-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31341300. S2CID 198494930.

- ^ Keigwin, L. D. (1996). "The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period in the Sargasso Sea". Science. 274 (5292): 1504–1508. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1504K. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1504. PMID 8929406. S2CID 27928974.

- ^ Mann, Michael E.; Woodruff, Jonathan D.; Donnelly, Jeffrey P.; Zhang, Zhihua (2009). "Atlantic hurricanes and climate over the past 1,500 years". Nature. 460 (7257): 880–3. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..880M. doi:10.1038/nature08219. hdl:1912/3165. PMID 19675650. S2CID 233167.

- ^ Gunnar Karlsson (2000). The history of Iceland. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3588-9. OCLC 42736334.

- ^ Lamb, H. H. (2011). Climate : present, past and future. Volume 2, Climatic history and the future. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-80430-8. OCLC 900419132.

- ^ a b Patterson, W. P.; Dietrich, K. A.; Holmden, C.; Andrews, J. T. (2010). "Two millennia of North Atlantic seasonality and implications for Norse colonies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (12): 5306–10. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5306P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902522107. PMC 2851789. PMID 20212157.

- ^ Vinther, B. M.; Jones, P. D.; Briffa, K. R.; Clausen, H. B.; Andersen, K. K.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Johnsen, S. J. (February 2010). "Climatic signals in multiple highly resolved stable isotope records from Greenland". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (3–4): 522–538. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29..522V. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.11.002.

- ^ D'Andrea, William J.; Huang, Yongsong; Fritz, Sherilyn C.; Anderson, N. John (31 May 2011). "Abrupt Holocene climate change as an important factor for human migration in West Greenland". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (24): 9765–9769. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.9765D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1101708108. PMC 3116382. PMID 21628586.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303655-5.[페이지 필요]

- ^ "Study Undercuts Idea That 'Medieval Warm Period' Was Global – The Earth Institute – Columbia University". earth.columbia.edu. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Ingstad, Anne Stine (2001). "The Excavation of a Norse Settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland". In Helge Ingstad; Anne Stine Ingstad (eds.). The Viking Discovery of America. New York: Checkmark. pp. 141–169. ISBN 978-0-8160-4716-1. OCLC 46683692.

- ^ Stockinger, Günther (10 January 2012). "Archaeologists Uncover Clues to Why Vikings Abandoned Greenland". Der Spiegel Online. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Moreno, Ana; Bartolomé, Miguel; López-Moreno, Juan Ignacio; Pey, Jorge; Corella, Juan Pablo; García-Orellana, Jordi; Sancho, Carlos; Leunda, María; Gil-Romera, Graciela; González-Sampériz, Penélope; Pérez-Mejías, Carlos (3 March 2021). "The case of a southern European glacier which survived Roman and medieval warm periods but is disappearing under recent warming". The Cryosphere. 15 (2): 1157–1172. Bibcode:2021TCry...15.1157M. doi:10.5194/tc-15-1157-2021. hdl:10810/51794. ISSN 1994-0416. S2CID 232275176.

- ^ Perșoiu, Ioana; Perșoiu, Aurel (2019). "Flood events in Transylvania during the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age". The Holocene. 29 (1): 85–96. Bibcode:2019Holoc..29...85P. doi:10.1177/0959683618804632. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 134035133.

- ^ Pascucci, V.; De Falco, G.; Del Vais, C.; Sanna, I.; Melis, R. T.; Andreucci, S. (1 January 2018). "Climate changes and human impact on the Mistras coastal barrier system (W Sardinia, Italy)". Marine Geology. 395: 271–284. Bibcode:2018MGeol.395..271P. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2017.11.002. ISSN 0025-3227.

- ^ "Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age and 20th Century Temperature Variability from Chesapeake Bay". USGS. Archived from the original on 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ "Marshes Tell Story Of Medieval Drought, Little Ice Age, And European Settlers Near New York City". Earth Observatory News. May 19, 2005. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Van de Plassche, Orson; Van der Borg, Klaas; De Jong, Arie F. M. (1 April 1998). "Sea level–climate correlation during the past 1400 yr". Geology. 26 (4): 319–322. Bibcode:1998Geo....26..319V. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1998)026<0319:SLCCDT>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Stine, Scott (1994). "Extreme and persistent drought in California and Patagonia during mediaeval time". Nature. 369 (6481): 546–549. Bibcode:1994Natur.369..546S. doi:10.1038/369546a0. S2CID 4315201.

- ^ Hu, F. S. (2001). "Pronounced climatic variations in Alaska during the last two millennia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (19): 10552–10556. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810552H. doi:10.1073/pnas.181333798. PMC 58503. PMID 11517320.

- ^ Dean, Jeffrey S. (1994). "The medieval warm period on the southern Colorado Plateau". Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 225–241. Bibcode:1994ClCh...26..225D. doi:10.1007/BF01092416. S2CID 189877071.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Los Osos Back Bay, Megalithic Portal, 편집자 A. 버넘.

- ^ Stahle, David W.; Cleaveland, Malcolm K. (March 1994). "Tree-ring reconstructed rainfall over the southeastern U.S.A. during the medieval warm period and little ice age". Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 199–212. doi:10.1007/BF01092414. ISSN 0165-0009. S2CID 189878139. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Benson, Larry V.; Pauketat, Timothy R.; Cook, Edward R. (2009). "Cahokia's Boom and Bust in the Context of Climate Change". American Antiquity. 74 (3): 467–483. doi:10.1017/S000273160004871X. ISSN 0002-7316. S2CID 160679096.

- ^ White, A. J.; Stevens, Lora R.; Lorenzi, Varenka; Munoz, Samuel E.; Schroeder, Sissel; Cao, Angelica; Bogdanovich, Taylor (19 March 2019). "Fecal stanols show simultaneous flooding and seasonal precipitation change correlate with Cahokia's population decline". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (12): 5461–5466. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.5461W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1809400116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6431169. PMID 30804191.

- ^ Jones, Terry L.; Schwitalla, Al (2008). "Archaeological perspectives on the effects of medieval drought in prehistoric California". Quaternary International. 188 (1): 41–58. Bibcode:2008QuInt.188...41J. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.07.007.

- ^ "Drought In West Linked To Warmer Temperatures". Earth Observatory News. 2004-10-07. Archived from the original on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Lécuyer, Christophe; Goedert, Jean; Klee, Johanne; Clauzel, Thibault; Richardin, Pascale; Fourel, François; Delgado-Darias, Teresa; Alberto-Barroso, Verónica; Velasco-Vázquez, Javier; Betancort, Juan Francisco; Amiot, Romain (2021-04-01). "Climatic change and diet of the pre-Hispanic population of Gran Canaria (Canary Archipelago, Spain) during the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age". Journal of Archaeological Science. 128: 105336. Bibcode:2021JArSc.128j5336L. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2021.105336. ISSN 0305-4403. S2CID 233597524. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Goosse, H.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Renssen, H.; Delmotte, M.; Fichefet, T.; Morgan, V.; Van Ommen, T.; Khim, B. K.; Stenni, B. (17 March 2004). "A late medieval warm period in the Southern Ocean as a delayed response to external forcing?". Geophysical Research Letters. 31 (6): 1–5. Bibcode:2004GeoRL..31.6203G. doi:10.1029/2003GL019140. S2CID 17322719.

- ^ Khim, B.; Yoon, Ho Il; Kang, Cheon Yun; Bahk, Jang Jun (2002). "Unstable Climate Oscillations during the Late Holocene in the Eastern Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula". Quaternary Research. 58 (3): 234. Bibcode:2002QuRes..58..234K. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2371. S2CID 129384061.

- ^ Lüning, Sebastian; Gałka, Mariusz; Vahrenholt, Fritz (15 October 2019). "The Medieval Climate Anomaly in Antarctica". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 532: 109251. Bibcode:2019PPP...53209251L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109251. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Cobb, Kim M.; Chris Charles; Hai Cheng; R. Lawrence Edwards (July 8, 2003). "The Medieval Cool Period And The Little Warm Age In The Central Tropical Pacific? Fossil Coral Climate Records Of The Last Millennium". The Climate of the Holocene (ICCI) 2003. Archived from the original on August 25, 2004. Retrieved 4 May 2006.

- ^ Rosenthal, Yair; Linsley, Braddock K.; Oppo, Delia W. (2013-11-01). "Pacific Ocean Heat Content During the Past 10,000 Years". Science. 342 (6158): 617–621. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..617R. doi:10.1126/science.1240837. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24179224. S2CID 140727975.

- ^ Fletcher, M-S.; Moreno, P.I. (16 July 2012). "Vegetation, climate and fire regime changes in the Andean region of southern Chile (38°S) covaried with centennial-scale climate anomalies in the tropical Pacific over the last 1500 years". Quaternary Science Reviews. 46: 46–56. Bibcode:2012QSRv...46...46F. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.04.016. hdl:10533/131338.

- ^ Ledru, M.-P.; Jomelli, V.; Samaniego, P.; Vuille, M.; Hidalgo, S.; Herrera, M.; Ceron, C. (2013). "The Medieval Climate Anomaly and the Little Ice Age in the eastern Ecuadorian Andes". Climate of the Past. 9 (1): 307–321. Bibcode:2013CliPa...9..307L. doi:10.5194/cp-9-307-2013.

- ^ Kellerhals, T.; Brütsch, S.; Sigl, M.; Knüsel, S.; Gäggeler, H. W.; Schwikowski, M. (2010). "Ammonium concentration in ice cores: A new proxy for regional temperature reconstruction?". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (D16): D16123. Bibcode:2010JGRD..11516123K. doi:10.1029/2009JD012603.

- ^ Ge, Q.-S.; Zheng, J.-Y.; Hao, Z.-X.; Shao, X.-M.; Wang, Wei-Chyung; Luterbacher, Juerg (2010). "Temperature variation through 2000 years in China: An uncertainty analysis of reconstruction and regional difference". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (3): 03703. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..37.3703G. doi:10.1029/2009GL041281. S2CID 129457163. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Hao, Zhixin; Wu, Maowei; Liu, Yang; Zhang, Xuezhen; Zheng, Jingyun (2020-01-01). "Multi-scale temperature variations and their regional differences in China during the Medieval Climate Anomaly". Journal of Geographical Sciences. 30 (1): 119–130. doi:10.1007/s11442-020-1718-7. ISSN 1861-9568. S2CID 209843427.

- ^ Zhou, XiuJi; Zhao, Ping; Liu, Ge; Zhou, TianJun (24 September 2011). "Characteristics of decadal-centennial-scale changes in East Asian summer monsoon circulation and precipitation during the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age and in the present day". Chinese Science Bulletin. 56 (28–29). doi:10.1007/s11434-011-4651-4. ISSN 1001-6538.

- ^ Zhang, Zhenqiu; Liang, Yijia; Wang, Yongjin; Duan, Fucai; Yang, Zhou; Shao, Qingfeng; Liu, Shushuang (15 December 2021). "Evidence of ENSO signals in a stalagmite-based Asian monsoon record during the medieval warm period". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 584: 110714. Bibcode:2021PPP...58410714Z. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110714. S2CID 239270259. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Liu, Xiaokang; Lu, Ruijie; Jia, Feifei; Chen, Lu; Li, Tengfei; Ma, Yuzhen; Wu, Yongqiu (5 March 2018). "Holocene water-level changes inferred from a section of fluvio-lacustrine sediments in the southeastern Mu Us Desert, China". Quaternary International. 469: 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.12.032. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Sun, Jia; Ma, Chunmei; Zhou, Bin; Jiang, Jiawei; Zhao, Cheng (2021). "Biogeochemical evidence for environmental and vegetation changes in peatlands from the middle Yangtze river catchment during the medieval warm period and little ice Age". The Holocene. 31 (10): 1571–1581. Bibcode:2021Holoc..31.1571S. doi:10.1177/09596836211025966. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 237010950.

- ^ Chu, Peter C.; Li, Hong-Chun; Fan, Chenwu; Chen, Yong-Heng (11 December 2012). "Speleothem evidence for temporal–spatial variation in the East Asian Summer Monsoon since the Medieval Warm Period". Journal of Quaternary Science. 27 (9): 901–910. doi:10.1002/jqs.2579. ISSN 0267-8179. S2CID 9727512. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Kamae, Youichi; Kawana, Toshi; Oshiro, Megumi; Ueda, Hiroaki (4 August 2017). "Seasonal modulation of the Asian summer monsoon between the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age: a multi model study". Progress in Earth and Planetary Science. 4 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s40645-017-0136-7. ISSN 2197-4284.

- ^ Razjigaeva, Nadezhda G.; Ganzey, Larisa A.; Bazarova, Valentina B.; Arslanov, Khikmatulla A.; Grebennikova, Tatiana A.; Mokhova, Ludmila M.; Belyanina, Nina I.; Lyaschevskaya, Marina S. (10 June 2019). "Landscape response to the Medieval Warm Period in the South Russian Far East". Quaternary International. The 3rd ASQUA Conference (Part II). 519: 215–231. Bibcode:2019QuInt.519..215R. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.12.006. ISSN 1040-6182. S2CID 134246491. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Adhikari, D. P.; Kumon, F. (2001). "Climatic changes during the past 1300 years as deduced from the sediments of Lake Nakatsuna, central Japan". Limnology. 2 (3): 157. doi:10.1007/s10201-001-8031-7. S2CID 20937188.

- ^ Yamada, Kazuyoshi; Kamite, Masaki; Saito-Kato, Megumi; Okuno, Mitsuru; Shinozuka, Yoshitsugu; Yasuda, Yoshinori (June 2010). "Late Holocene monsoonal-climate change inferred from Lakes Ni-no-Megata and San-no-Megata, northeastern Japan". Quaternary International. 220 (1–2): 122–132. Bibcode:2010QuInt.220..122Y. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.09.006. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Naidu, Pothuri Divakar; Ganeshram, Raja; Bollasina, Massimo A.; Panmei, Champoungam; Nürnberg, Dirk; Donges, Jonathan F. (2020-01-28). "Coherent response of the Indian Monsoon Rainfall to Atlantic Multi-decadal Variability over the last 2000 years". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1302. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.1302N. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-58265-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6987308. PMID 31992786.

- ^ Naidu, Pothuri Divakar; Ganeshram, Raja; Bollasina, Massimo A.; Panmei, Champoungam; Nürnberg, Dirk; Donges, Jonathan F. (28 January 2020). "Coherent response of the Indian Monsoon Rainfall to Atlantic Multi-decadal Variability over the last 2000 years". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1302. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.1302N. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-58265-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6987308. PMID 31992786.

- ^ Rawat, Suman; Gupta, Anil K.; Sangode, S. J.; Srivastava, Priyeshu; Nainwal, H.C. (15 April 2015). "Late Pleistocene–Holocene vegetation and Indian summer monsoon record from the Lahaul, Northwest Himalaya, India". Quaternary Science Reviews. 114: 167–181. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.01.032. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Quamar, M. F.; Chauhan, M. S. (19 March 2014). "Signals of Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age from southwestern Madhya Pradesh (India): A pollen-inferred Late-Holocene vegetation and climate change". Quaternary International. Holocene Palynology and Tropical Paleoecology. 325: 74–82. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.07.011. ISSN 1040-6182. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Veena, M.P.; Achyuthan, Hema; Eastoe, Christopher; Farooqui, Anjum (19 March 2014). "A multi-proxy reconstruction of monsoon variability in the late Holocene, South India". Quaternary International. 325: 63–73. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.026. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Gupta, Anil K.; Anderson, David M.; Overpeck, Jonathan T. (23 January 2003). "Abrupt changes in the Asian southwest monsoon during the Holocene and their links to the North Atlantic Ocean". Nature. 421 (6921): 354–357. doi:10.1038/nature01340. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4304234.

- ^ Agnihotri, Rajesh; Dutta, Koushik; Bhushan, Ravi; Somayajulu, B. L. K (15 May 2002). "Evidence for solar forcing on the Indian monsoon during the last millennium". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 198 (3): 521–527. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00530-7. ISSN 0012-821X. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Kalman, Akos; Katz, Timor; Hill, Paul; Goodman-Tchernov, Beverly (21 March 2020). "Droughts in the desert: Medieval Warm Period associated with coarse sediment layers in the Gulf of Aqaba-Eilat, Red Sea". Sedimentology. 67 (6): 3152–3166. doi:10.1111/sed.12737. S2CID 216335544. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Allen, Robert J. (1985). The Australasian Summer Monsoon, Teleconnections, and Flooding in the Lake Eyre Basin. Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, S.A. Branch. ISBN 978-0-909112-09-7.[페이지 필요]

- ^ Wilson, A. T.; Hendy, C. H.; Reynolds, C. P. (1979). "Short-term climate change and New Zealand temperatures during the last millennium". Nature. 279 (5711): 315. Bibcode:1979Natur.279..315W. doi:10.1038/279315a0. S2CID 4302802.

- ^ Cook, Edward R.; Palmer, Jonathan G.; d'Arrigo, Rosanne D. (2002). "Evidence for a 'Medieval Warm Period' in a 1,100 year tree-ring reconstruction of past austral summer temperatures in New Zealand". Geophysical Research Letters. 29 (14): 12. Bibcode:2002GeoRL..29.1667C. doi:10.1029/2001GL014580. S2CID 34033855.

추가읽기

- Fagan, Brian (2000). The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History, 1300–1850. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02272-4.

- Fagan, Brian (2009). The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781596913929.

- Lamb, Hubert (1995). Climate, History, and the Modern World: Second Edition. Routledge.

- Staff members at NOAA Paleoclimatology (19 May 2000). The "Medieval Warm Period". A Paleo Perspective...on Global Warming. NOAA Paleoclimatology.

{{cite book}}: 에서외부 링크author=

외부 링크

- HistoricalClimatology.com , 추가 링크, 리소스 및 관련 뉴스, 업데이트된 2016년

- 기후 역사 네트워크

- 미국 지구물리학연합의 소빙하기와 중세 온난기