식물권

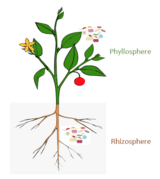

Phyllosphere식물권은 미생물의 서식지로 볼 때 식물의 지상 표면 총량을 가리키는 미생물학에서 사용되는 용어다.[1][2] 식물권은 콜로스피어(줄기), 필로플레인(레브), 안토스피어(꽃), 잉어스피어(과일)로 더욱 세분화될 수 있다. 지하 미생물 서식지(즉, 뿌리나 지하 줄기 표면을 둘러싸고 있는 얇은 토양의 부피)를 rhizoper와 laimoper라고 한다. 대부분의 식물들은 박테리아, 곰팡이, 고고학, 그리고 원생물을 포함한 미생물의 다양한 공동체를 가지고 있다. 어떤 것들은 식물에 유익하고, 다른 것들은 식물의 병원균의 역할을 하며 숙주식물을 손상시키거나 심지어 죽일 수도 있다.

식물권 마이크로바이옴

| 다음에 대한 시리즈 일부 |

| 마이크로바이옴 |

|---|

|

잎 표면 또는 식물권은 다양한 박테리아, 고고학, 곰팡이, 조류, 바이러스로 구성된 마이크로바이옴을 포함하고 있다.[3][4] 미생물 결장자는 열, 수분, 방사선의 일야성 및 계절적 변동을 겪는다. 또한 이러한 환경적 요소들은 식물 생리학(광합성, 호흡, 물 흡수 등)에 영향을 미치고 미생물 구성에도 간접적으로 영향을 미친다.[5] 비바람은 또한 식물권 마이크로바이옴에 일시적 변동을 일으킨다.[6]

식물권은 식물의 전체 공중(지상 위) 표면을 포함하며, 이와 같이 줄기의 표면, 꽃과 과일, 특히 잎 표면이 포함된다. 소성권 및 소내권과 비교해 볼 때, 식물권은 영양소가 부족하고 그 환경은 더 역동적이다.

이러한 많은 마이크로바이옴에서 식물과 관련 미생물 사이의 상호작용은 식물 건강, 기능 및 진화에 중추적인 역할을 할 수 있다.[7] 숙주 식물과 식물권 박테리아 사이의 상호작용은 숙주 식물 생리학의 다양한 측면을 촉진할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다.[8][2][9] 그러나 2020년 현재, 식물권 내 이러한 박테리아 연관성에 대한 지식은 비교적 겸손한 상태를 유지하고 있으며, 식물권 마이크로바이옴 역학에 대한 근본적인 지식을 발전시킬 필요가 있다.[10][11]

잎 표면에서 착생성 박테리아 집단으로 엄격히 정의할 수 있는 식물권 미생물 집단은 주변 환경에 존재하는 미생물 집단(즉, 확률적 결장)과 숙주 식물(즉, 생물 선택)에 의해 형성될 수 있다.[3][12][11] 그러나 잎 표면은 일반적으로 이산 미생물 서식지로 여겨지지만,[13][14] 식물권 마이크로바이옴 전체에 걸친 공동체 집회의 지배적 동인에 대해서는 의견이 일치되지 않는다. 예를 들어, 숙주별 박테리아 집단은 공동 발생 식물 종의 식물권에 보고되어 숙주 선택의 지배적인 역할을 시사하고 있다.[14][15][16][11]

반대로, 주변 환경의 마이크로바이옴은 또한 식물권 공동체 구성의 주요 결정요인으로 보고되었다.[13][17][18][19] 결과적으로, 식물권 공동체 집단을 추진하는 과정은 잘 이해되지는 않지만 식물 종 전반에 걸쳐 보편화 될 가능성은 낮다. 그러나 기존의 증거는 호스트 특정 연관성을 나타내는 식물권 마이크로바이옴이 주변 환경에서 주로 모집된 것보다 호스트와 상호작용할 가능성이 더 높다는 것을 나타낸다.[8][20][21][22][11]

전반적으로, 식물권 공동체에는 높은 종의 풍요로움이 남아 있다. 곰팡이 공동체는 온대지방의 식물권에서 변동성이 크고 열대지방에 비해 다양하다.[24] 식물의 잎 표면에는 평방 센티미터 당 최대 107개의 미생물이 존재할 수 있으며, 전지구적 규모의 식물권의 박테리아 개체수는 10개의26 세포로 추정된다.[25] 곰팡이 식물권의 인구 크기는 더 작을 것 같다.[26]

서로 다른 식물의 식물권 미생물은 높은 수준의 세금에서 다소 유사한 것으로 보이지만, 낮은 수준의 세금에서는 상당한 차이가 남아 있다. 이는 미생물이 식물권 환경에서 생존하기 위해 미세 조정된 대사 조정이 필요할 수 있음을 나타낸다.[24] 프로테오박테리아가 지배적인 대장균인 것으로 보이며, 박테로이데테스와 악티노박테리아도 필로스피어에서 우세하다.[27] 원시권과 토양 미생물군 사이에는 유사성이 있지만, 식물권 집단과 야외 공기에 떠다니는 미생물(에로플랑크톤) 사이에는 유사성이 거의 발견되지 않았다.[28][5]

숙주와 관련된 미생물 집단의 핵심 미생물 탐색은 숙주와 그 미생물 사이에 발생할 수 있는 상호작용을 이해하려고 노력하는 데 있어 유용한 첫 번째 단계다.[29][30] 지배적인 핵심 마이크로바이옴 개념은 생태적 틈새의 경계선을 가로지르는 타조의 지속성이 그것이 점유하는 틈새 내에서 그것의 기능적 중요성을 직접적으로 반영한다는 개념에 기초하여 구축된다. 따라서 그것은 지속적으로 연관되는 기능적으로 중요한 미생물을 식별하기 위한 프레임워크를 제공한다.e 숙주종과 함께.[29][31][32][11]

"핵심 마이크로바이옴"에 대한 다양한 정의가 과학 문헌 전반에 걸쳐 생겨났으며, 연구자들은 "핵심세사"를 구별하여 구별되는 숙주 마이크로하비타트 및 심지어 다른 종에 걸쳐 집요하게 구별하였다.[16][20] 로 지속적인 tissue-과 종의 호스트 microbiomes 내에 넓은 지리적 거리를 가로질러, 이 개념적인 framewor의 가장 생물학적으로 그리고 생태학적으로 적절한 응용 프로그램을 나타내는 미생물의 다른 숙주를 가로질러 기능적인 발산[16]과 microhabitats,[36]을 정의하는 핵심 TAXON의 복수 sensu stricto.k.[37][11] 광범위한 지리적 거리로 분리된 호스트 모집단에 걸친 조직 및 종별 고유 코어 마이크로바이옴은 루이엔이 정한 엄격한 정의를 사용하여 식물권에 대해 널리 보고되지 않았다.[2][11]

예: 마누카 식물권

흔히 마누카라고 알려진 꽃다루는 뉴질랜드 토착이다.[38] 마누카 꽃의 과즙에서 생산되는 마누카꿀은 과산화하지 않은 항균성으로 알려져 있다.[39][40] 이러한 비과산화 항균 성질은 주로 성숙한 꿀에서 메틸글리옥살(MGO)로 화학적 변환을 거치는 마누카 꽃의 과즙에 3탄소당 디히드록시아세톤(DHA)이 축적되는 것과 관련이 있다.[41][42][43] 단, 마누카 꽃의 과즙에서 DHA의 농도는 악명높은 것으로 악명이 높으며, 결과적으로 마누카 꿀의 항균 효능은 지역마다, 그리고 연도별로 차이가 있다.[44][45][46] 광범위한 연구 노력에도 불구하고, DHA 생산과 기후,[47] 에다피치 또는 [48]숙주 유전적 요인 사이에 신뢰할 수 있는 상관관계가 확인되지 않았다.[49][11]

미생물은 마누카 왕족권 및 종족권에서 연구되어 왔다.[50][51][52] 이전의 연구는 주로 곰팡이에 초점을 맞췄으며, 2016년 연구는 지문 기법을 사용하여 지리적으로 환경적으로 구별되는 세 마누카 개체군으로부터 내생식 박테리아 집단을 처음으로 조사했고 조직 고유의 핵심 내포미크로바이옴을 밝혀냈다.[53][11] 2020년 연구는 모든 표본에 걸쳐 지속되는 마누카 식물권에서 서식지에 특유하고 상대적으로 풍부한 코어 마이크로바이옴을 확인했다. 이와는 대조적으로 비핵심 식물권 미생물은 환경적, 공간적 요인에 의해 강하게 추진된 개별 숙주 나무와 모집단에 걸쳐 상당한 변동을 보였다. 그 결과는 마누카의 식물권에 지배적이고 유비쿼터스한 핵심 마이크로바이옴의 존재를 입증했다.[11]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ Last, F.T. (1955). "Seasonal incidence of Sporobolomyces on cereal leaves". Trans Br Mycol Soc. 38 (3): 221–239. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(55)80069-1.

- ^ a b c Cid, Fernanda P.; Maruyama, Fumito; Murase, Kazunori; Graether, Steffen P.; Larama, Giovanni; Bravo, Leon A.; Jorquera, Milko A. (2018). "Draft genome sequences of bacteria isolated from the Deschampsia antarctica phyllosphere". Extremophiles. 22 (3): 537–552. doi:10.1007/s00792-018-1015-x. PMID 29492666. S2CID 4320165.

- ^ a b Leveau, Johan HJ (2019). "A brief from the leaf: Latest research to inform our understanding of the phyllosphere microbiome". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 49: 41–49. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.002. PMID 31707206.

- ^ 루이엔, J. (1956) "생리권 내에 베이제린키아 종의 발생" 자연, 177(4501): 220–221.

- ^ a b 다스토게어, K.M., Tumpa, F.H., 술타나, A., Akter, M.A., Chakraborty, A.(2020) "식물 마이크로바이옴-은 공동체 구성과 다양성을 형성하는 요소들에 대한 설명"이다. 현재 식물 생물학: 100161. doi:10.1016/j.cpb.2020.100161.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다. - ^ Lindow, Steven E. (1996). "Role of Immigration and Other Processes in Determining Epiphytic Bacterial Populations". Aerial Plant Surface Microbiology. pp. 155–168. doi:10.1007/978-0-585-34164-4_10. ISBN 978-0-306-45382-3.

- ^ Friesen, Maren L.; Porter, Stephanie S.; Stark, Scott C.; von Wettberg, Eric J.; Sachs, Joel L.; Martinez-Romero, Esperanza (2011). "Microbially Mediated Plant Functional Traits". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 42: 23–46. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145039.

- ^ a b Vogel, Christine; Bodenhausen, Natacha; Gruissem, Wilhelm; Vorholt, Julia A. (2016). "The Arabidopsis leaf transcriptome reveals distinct but also overlapping responses to colonization by phyllosphere commensals and pathogen infection with impact on plant health" (PDF). New Phytologist. 212 (1): 192–207. doi:10.1111/nph.14036. hdl:20.500.11850/117578. PMID 27306148.

- ^ Kumaravel, Sowmya; Thankappan, Sugitha; Raghupathi, Sridar; Uthandi, Sivakumar (2018). "Draft Genome Sequence of Plant Growth-Promoting and Drought-Tolerant Bacillus altitudinis FD48, Isolated from Rice Phylloplane". Genome Announcements. 6 (9). doi:10.1128/genomeA.00019-18. PMC 5834328. PMID 29496824.

- ^ Laforest‐Lapointe, Isabelle; Whitaker, Briana K. (2019). "Decrypting the phyllosphere microbiota: Progress and challenges". American Journal of Botany. 106 (2): 171–173. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1229. PMID 30726571.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l 노블, Anya S.;노에, 스티비, 클리어 워터, 마이클 J., 대통령, 찰스 K.(2020년)."핵심 phyllosphere microbiome 수종의 먼 모집단에 대해 indigenous 뉴질랜드에 존재하".PLOS ONE.15세(8):e0237079.Bibcode:2020년PLoSO..1537079N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237079.PMC 7425925.PMID 32790769.재료는 창조적 공용 귀인 4.0국제 라이센스 하에 가능하다 이 원본에서 복사되었다.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다. - ^ Vorholt, Julia A. (2012). "Microbial life in the phyllosphere". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 10 (12): 828–840. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2910. hdl:20.500.11850/59727. PMID 23154261. S2CID 10447146.

- ^ a b Stone, Bram W. G.; Jackson, Colin R. (2016). "Biogeographic Patterns Between Bacterial Phyllosphere Communities of the Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) in a Small Forest". Microbial Ecology. 71 (4): 954–961. doi:10.1007/s00248-016-0738-4. PMID 26883131. S2CID 17292307.

- ^ a b Redford, Amanda J.; Bowers, Robert M.; Knight, Rob; Linhart, Yan; Fierer, Noah (2010). "The ecology of the phyllosphere: Geographic and phylogenetic variability in the distribution of bacteria on tree leaves". Environmental Microbiology. 12 (11): 2885–2893. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02258.x. PMC 3156554. PMID 20545741.

- ^ Vokou, Despoina; Vareli, Katerina; Zarali, Ekaterini; Karamanoli, Katerina; Constantinidou, Helen-Isis A.; Monokrousos, Nikolaos; Halley, John M.; Sainis, Ioannis (2012). "Exploring Biodiversity in the Bacterial Community of the Mediterranean Phyllosphere and its Relationship with Airborne Bacteria". Microbial Ecology. 64 (3): 714–724. doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0053-7. PMID 22544345. S2CID 17291303.

- ^ a b c Laforest-Lapointe, Isabelle; Messier, Christian; Kembel, Steven W. (2016). "Host species identity, site and time drive temperate tree phyllosphere bacterial community structure". Microbiome. 4 (1): 27. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0174-1. PMC 4912770. PMID 27316353.

- ^ Zarraonaindia, Iratxe; Owens, Sarah M.; Weisenhorn, Pamela; West, Kristin; Hampton-Marcell, Jarrad; Lax, Simon; Bokulich, Nicholas A.; Mills, David A.; Martin, Gilles; Taghavi, Safiyh; Van Der Lelie, Daniel; Gilbert, Jack A. (2015). "The Soil Microbiome Influences Grapevine-Associated Microbiota". mBio. 6 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.02527-14. PMC 4453523. PMID 25805735.

- ^ Finkel, Omri M.; Burch, Adrien Y.; Lindow, Steven E.; Post, Anton F.; Belkin, Shimshon (2011). "Geographical Location Determines the Population Structure in Phyllosphere Microbial Communities of a Salt-Excreting Desert Tree". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (21): 7647–7655. doi:10.1128/AEM.05565-11. PMC 3209174. PMID 21926212.

- ^ Finkel, Omri M.; Burch, Adrien Y.; Elad, Tal; Huse, Susan M.; Lindow, Steven E.; Post, Anton F.; Belkin, Shimshon (2012). "Distance-Decay Relationships Partially Determine Diversity Patterns of Phyllosphere Bacteria on Tamrix Trees across the Sonoran Desert". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 78 (17): 6187–6193. doi:10.1128/AEM.00888-12. PMC 3416633. PMID 22752165.

- ^ a b Kembel, S. W.; O'Connor, T. K.; Arnold, H. K.; Hubbell, S. P.; Wright, S. J.; Green, J. L. (2014). "Relationships between phyllosphere bacterial communities and plant functional traits in a neotropical forest". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (38): 13715–13720. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11113715K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216057111. PMC 4183302. PMID 25225376. S2CID 852584.

- ^ Innerebner, Gerd; Knief, Claudia; Vorholt, Julia A. (2011). "Protection of Arabidopsis thaliana against Leaf-Pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae by Sphingomonas Strains in a Controlled Model System". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (10): 3202–3210. doi:10.1128/AEM.00133-11. PMC 3126462. PMID 21421777.

- ^ Lajoie, Geneviève; Maglione, Rémi; Kembel, Steven W. (2020). "Adaptive matching between phyllosphere bacteria and their tree hosts in a neotropical forest". Microbiome. 8 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00844-7. PMC 7243311. PMID 32438916.

- ^ Compant, Stéphane; Cambon, Marine C.; Vacher, Corinne; Mitter, Birgit; Samad, Abdul; Sessitsch, Angela (2020). "The plant endosphere world – bacterial life within plants". Environmental Microbiology. 23 (4): 1812–1829. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15240. ISSN 1462-2912. PMID 32955144.

- ^ a b Finkel, Omri M.; Burch, Adrien Y.; Lindow, Steven E.; Post, Anton F.; Belkin, Shimshon (2011). "Geographical Location Determines the Population Structure in Phyllosphere Microbial Communities of a Salt-Excreting Desert Tree". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (21): 7647–7655. doi:10.1128/AEM.05565-11. PMC 3209174. PMID 21926212.

- ^ Vorholt, Julia A. (2012). "Microbial life in the phyllosphere". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 10 (12): 828–840. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2910. hdl:20.500.11850/59727. PMID 23154261. S2CID 10447146.

- ^ Lindow, Steven E.; Brandl, Maria T. (2003). "Microbiology of the Phyllosphere". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (4): 1875–1883. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.4.1875-1883.2003. PMC 154815. PMID 12676659. S2CID 2304379.

- ^ Bodenhausen, Natacha; Horton, Matthew W.; Bergelson, Joy (2013). "Bacterial Communities Associated with the Leaves and the Roots of Arabidopsis thaliana". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e56329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056329. PMC 3574144. PMID 23457551.

- ^ Vokou, Despoina; Vareli, Katerina; Zarali, Ekaterini; Karamanoli, Katerina; Constantinidou, Helen-Isis A.; Monokrousos, Nikolaos; Halley, John M.; Sainis, Ioannis (2012). "Exploring Biodiversity in the Bacterial Community of the Mediterranean Phyllosphere and its Relationship with Airborne Bacteria". Microbial Ecology. 64 (3): 714–724. doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0053-7. PMID 22544345. S2CID 17291303.

- ^ a b Shade, Ashley; Handelsman, Jo (2012). "Beyond the Venn diagram: The hunt for a core microbiome". Environmental Microbiology. 14 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02585.x. PMID 22004523.

- ^ Berg, Gabriele; Rybakova, Daria; Fischer, Doreen; Cernava, Tomislav; Vergès, Marie-Christine Champomier; Charles, Trevor; Chen, Xiaoyulong; Cocolin, Luca; Eversole, Kellye; Corral, Gema Herrero; Kazou, Maria; Kinkel, Linda; Lange, Lene; Lima, Nelson; Loy, Alexander; MacKlin, James A.; Maguin, Emmanuelle; Mauchline, Tim; McClure, Ryan; Mitter, Birgit; Ryan, Matthew; Sarand, Inga; Smidt, Hauke; Schelkle, Bettina; Roume, Hugo; Kiran, G. Seghal; Selvin, Joseph; Souza, Rafael Soares Correa de; Van Overbeek, Leo; et al. (2020). "Microbiome definition re-visited: Old concepts and new challenges". Microbiome. 8 (1): 103. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0. PMC 7329523. PMID 32605663.

- ^ Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Hamady, Micah; Yatsunenko, Tanya; Cantarel, Brandi L.; Duncan, Alexis; Ley, Ruth E.; Sogin, Mitchell L.; Jones, William J.; Roe, Bruce A.; Affourtit, Jason P.; Egholm, Michael; Henrissat, Bernard; Heath, Andrew C.; Knight, Rob; Gordon, Jeffrey I. (2009). "A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins". Nature. 457 (7228): 480–484. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..480T. doi:10.1038/nature07540. PMC 2677729. PMID 19043404.

- ^ Lundberg, Derek S.; Lebeis, Sarah L.; Paredes, Sur Herrera; Yourstone, Scott; Gehring, Jase; Malfatti, Stephanie; Tremblay, Julien; Engelbrektson, Anna; Kunin, Victor; Rio, Tijana Glavina del; Edgar, Robert C.; Eickhorst, Thilo; Ley, Ruth E.; Hugenholtz, Philip; Tringe, Susannah Green; Dangl, Jeffery L. (2012). "Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome". Nature. 488 (7409): 86–90. Bibcode:2012Natur.488...86L. doi:10.1038/nature11237. PMC 4074413. PMID 22859206.

- ^ 그, 성양(2020년) 식물과 그 미생물이 조화를 이루지 못할 때, 그 결과는 재앙이 될 수 있다. The Conversation, 2020년 8월 28일.

- ^ Hamonts, Kelly; Trivedi, Pankaj; Garg, Anshu; Janitz, Caroline; Grinyer, Jasmine; Holford, Paul; Botha, Frederik C.; Anderson, Ian C.; Singh, Brajesh K. (2018). "Field study reveals core plant microbiota and relative importance of their drivers". Environmental Microbiology. 20 (1): 124–140. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14031. PMID 29266641. S2CID 10650949.

- ^ Cernava, Tomislav; Erlacher, Armin; Soh, Jung; Sensen, Christoph W.; Grube, Martin; Berg, Gabriele (2019). "Enterobacteriaceae dominate the core microbiome and contribute to the resistome of arugula (Eruca sativa Mill.)". Microbiome. 7 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s40168-019-0624-7. PMC 6352427. PMID 30696492.

- ^ Leff, Jonathan W.; Del Tredici, Peter; Friedman, William E.; Fierer, Noah (2015). "Spatial structuring of bacterial communities within individual Ginkgo bilobatrees". Environmental Microbiology. 17 (7): 2352–2361. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12695. PMID 25367625.

- ^ Hernandez-Agreda, Alejandra; Gates, Ruth D.; Ainsworth, Tracy D. (2017). "Defining the Core Microbiome in Corals' Microbial Soup". Trends in Microbiology. 25 (2): 125–140. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.003. PMID 27919551.

- ^ Stephens, J. M. C.; Molan, P. C.; Clarkson, B. D. (2005). "A review of Leptospermum scoparium(Myrtaceae) in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 43 (2): 431–449. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2005.9512966. S2CID 53515334.

- ^ Cooper, R.A.; Molan, P.C.; Harding, K.G. (2002). "The sensitivity to honey of Gram-positive cocci of clinical significance isolated from wounds". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 93 (5): 857–863. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01761.x. PMID 12392533. S2CID 24517001.

- ^ Rabie, Erika; Serem, June Cheptoo; Oberholzer, Hester Magdalena; Gaspar, Anabella Regina Marques; Bester, Megan Jean (2016). "How methylglyoxal kills bacteria: An ultrastructural study". Ultrastructural Pathology. 40 (2): 107–111. doi:10.3109/01913123.2016.1154914. hdl:2263/52156. PMID 26986806. S2CID 13372064.

- ^ Adams, Christopher J.; Manley-Harris, Merilyn; Molan, Peter C. (2009). "The origin of methylglyoxal in New Zealand manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey". Carbohydrate Research. 344 (8): 1050–1053. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2009.03.020. PMID 19368902.

- ^ Atrott, Julia; Haberlau, Steffi; Henle, Thomas (2012). "Studies on the formation of methylglyoxal from dihydroxyacetone in Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey". Carbohydrate Research. 361: 7–11. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2012.07.025. PMID 22960208.

- ^ Mavric, Elvira; Wittmann, Silvia; Barth, Gerold; Henle, Thomas (2008). "Identification and quantification of methylglyoxal as the dominant antibacterial constituent of Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium)honeys from New Zealand". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 52 (4): 483–489. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700282. PMID 18210383.

- ^ 해밀턴, G, 밀너, J, 로버슨, A., Stephens, J. (2013) "고품질의 '마누카 인자' 꿀 생산을 위한 마누카 입증 평가" 뉴질랜드 애그로노미, 43: 139–144.

- ^ Williams, Simon; King, Jessica; Revell, Maria; Manley-Harris, Merilyn; Balks, Megan; Janusch, Franziska; Kiefer, Michael; Clearwater, Michael; Brooks, Peter; Dawson, Murray (2014). "Regional, Annual, and Individual Variations in the Dihydroxyacetone Content of the Nectar of Ma̅nuka (Leptospermum scoparium) in New Zealand". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (42): 10332–10340. doi:10.1021/jf5045958. PMID 25277074.

- ^ Stephens, J.M.C. (2006) "마누카(Leptospermum scoparium) 꿀의 UMF®의 다양한 수준을 책임지는 요인" 박사학위 논문 Waikato 대학.

- ^ Noe, Stevie; Manley-Harris, Merilyn; Clearwater, Michael J. (2019). "Floral nectar of wild mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) varies more among plants than among sites". New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 47 (4): 282–296. doi:10.1080/01140671.2019.1670681. S2CID 204143940.

- ^ Nickless, Elizabeth M.; Anderson, Christopher W. N.; Hamilton, Georgie; Stephens, Jonathan M.; Wargent, Jason (2017). "Soil influences on plant growth, floral density and nectar yield in three cultivars of mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium)". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 55 (2): 100–117. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2016.1247732. S2CID 88657399.

- ^ Clearwater, Michael J.; Revell, Maria; Noe, Stevie; Manley-Harris, Merilyn (2018). "Influence of genotype, floral stage, and water stress on floral nectar yield and composition of mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium)". Annals of Botany. 121 (3): 501–512. doi:10.1093/aob/mcx183. PMC 5838834. PMID 29300875.

- ^ Johnston, Peter R. (1998). "Leaf endophytes of manuka (Leptospermum scoparium)". Mycological Research. 102 (8): 1009–1016. doi:10.1017/S0953756297005765.

- ^ McKenzie, E. H. C.; Johnston, P. R.; Buchanan, P. K. (2006). "Checklist of fungi on teatree (Kunzeaand Leptospermumspecies) in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 44 (3): 293–335. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2006.9513025. S2CID 84538904.

- ^ Wicaksono, Wisnu Adi; Sansom, Catherine E.; Eirian Jones, E.; Perry, Nigel B.; Monk, Jana; Ridgway, Hayley J. (2018). "Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with Leptospermum scoparium (Mānuka): Effects on plant growth and essential oil content". Symbiosis. 75: 39–50. doi:10.1007/s13199-017-0506-3. S2CID 4819178.

- ^ Wicaksono, Wisnu Adi; Jones, E. Eirian; Monk, Jana; Ridgway, Hayley J. (2016). "The Bacterial Signature of Leptospermum scoparium (Mānuka) Reveals Core and Accessory Communities with Bioactive Properties". PLOS ONE. 11 (9): e0163717. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1163717W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163717. PMC 5038978. PMID 27676607.

- ^ Carvalho, Sofia D.; Castillo, José A. (2018). "Influence of Light on Plant–Phyllosphere Interaction". Frontiers in Plant Science. 9. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01482.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다.

자료는 이 출처에서 복사되었으며, Creative Commons Accountation 4.0 International License에 따라 이용할 수 있다.