혜성핵

Comet nucleus이 문서는 갱신할 필요가 있습니다.(2020년 7월) |

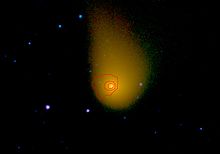

핵은 한때 더러운 눈덩이 또는 얼음 흙덩어리라고 불렸던 혜성의 단단한 중심부이다.혜성핵은 암석, 먼지, 그리고 얼어붙은 가스로 구성되어 있다.태양에 의해 가열될 때, 그 가스는 승화하여 혼수라고 알려진 핵을 둘러싼 대기를 생성한다.태양의 복사압과 태양풍에 의해 혼수상태에 가해진 힘은 태양으로부터 멀리 떨어진 거대한 꼬리를 형성하게 한다.전형적인 혜성의 핵은 0.04의 [1]알베도를 가지고 있다.이것은 석탄보다 검고 [2]먼지로 인해 발생할 수 있습니다.

로제타와 필레 우주선의 결과는 67P/추류모프-게라시멘코의 핵에는 자기장이 없다는 것을 보여주며,[3][4] 이는 미행성체의 초기 형성에 자력이 작용하지 않았음을 시사한다.또한, 로제타의 ALICE 분광기는 태양 복사에 의한 물 분자의 광이온화에서 생성된 전자(혜성 핵 위 1km 이내)가 혜성 핵에서 방출된 물과 이산화탄소 분자의 분해에 책임이 있다는 것을 알아냈다.2015년 [5][6]7월 30일 과학자들은 2014년 11월 67P/추류모프-게라시멘코 혜성에 착륙한 필레 우주선이 최소 16종의 유기화합물을 검출했으며,[7][8][9] 이 중 아세트아미드, 아세톤, 이소시아네이트메틸, 프로페오알데히드 등 4종이 혜성 최초로 검출됐다고 보고했다.

패러다임

혜성핵은 약 1km에서 때로는 수십km까지 망원경으로 분해할 수 없었다.현재의 거대 망원경조차도 핵이 지구 근처에 있을 때 혼수상태에 의해 가려지지 않는다고 가정할 때 목표물에 불과 몇 개의 픽셀을 줄 것이다.핵에 대한 이해와 혼수현상은 여러 증거에서 추론해야 했다.

'날아다니는 모래톱'

1800년대 후반에 처음 제안된 "날아다니는 모래톱" 모형은 혜성을 별개의 물체가 아닌 물체의 무리라고 가정한다.활동이란 휘발성 물질과 [10]인구 구성원 모두를 잃는 것이다.이 모델은 기원과 함께 Lytleton에 의해 세기 중반에 옹호되었습니다.태양이 성간 성운을 통과할 때 물질은 소용돌이 모양으로 뭉칠 것이다.일부는 사라지지만 일부는 태양중심 궤도에 남아있을 것이다.약한 포획은 길고, 편심하고, 기울어진 혜성 궤도를 설명했다.얼음 자체가 부족했다; 휘발성 물질은 [11][12][13][14]곡물에 흡착되어 저장되었다.

'더러운 눈덩이'

Lytleton 직후 Fred Whipple은 그의 "멋진 대기업" [15][16]모델을 발표했다.이것은 곧 "더러운 눈덩이"로 대중화 되었다.혜성의 궤도는 꽤 정확하게 결정되었지만, 혜성은 때때로 "예정외"로 며칠이나 회복되었다.초기 혜성은 "에테르"와 같은 "저항 매체" 또는 혜성 전면에 대한 유성체의 누적 작용에 의해 설명될 수 있습니다.[17]하지만 혜성은 일찍 또는 늦게 돌아올 수 있다.휘플은 비대칭 방출(현재는 "중력"이 아닌 다른 방출로 인한 약한 추력이 혜성 타이밍을 더 잘 설명해준다고 주장했다.이를 위해서는 이미터가 응집력을 가질 필요가 있었다. 즉, 일정 비율의 휘발성 물질이 있는 단일 고체 핵이다.Lytton은 1972년까지 [18]비행 모래톱 작품을 계속 출판했다.하늘을 나는 모래톱의 종말은 핼리 혜성이었다.베가2와 지오토의 이미지는 작은 [19][20]수의 제트기를 통해 방출되는 하나의 몸을 보여주었다.

"얼음 흙덩어리"

혜성의 핵이 얼어붙은 [21]눈덩이로 상상될 수 있었던 것은 오래 전이다.휘플은 이미 크러스트와 인테리어를 따로 가정하고 있었다.1986년 핼리가 나타나기 전에, 노출된 얼음 표면은 심지어 혼수 상태에서도 유한한 수명을 가질 것으로 보였다.핼리의 핵은 가스의 파괴/탈출 및 내화물 [22][23][24][25]보유로 인해 밝지 않고 어두운 것으로 예측되었다.먼지 맨틀링이라는 용어는 35년 [26]이상 동안 일반적으로 사용되어 왔습니다.

핼리 결과는 이마저도 초과했다. 혜성은 단순히 어두운 것이 아니라 태양계에서 가장 어두운 물체 중 하나이며, 게다가 이전의 먼지 추정치는 심각한 과소계수였다.미세한 입자와 큰 조약돌 둘 다 우주선 탐지기에는 나타났지만 지상 망원경에는 나타나지 않았다.휘발성 분율에는 물과 다른 가스뿐만 아니라 유기물도 포함되어 있었다.먼지-얼음 비율은 생각보다 훨씬 가까이 나타났다.매우 낮은 밀도(0.1~0.5g cm-3)가 [28]도출되었다.핵은 여전히 다수결 [19]얼음으로 추정되었고, 아마도 압도적으로 [20]그럴 것이다.

현대 이론

세 번의 랑데부 임무를 제외하고, 핼리가 그 한 예이다.그것의 좋지 않은 궤적 또한 한 때 극단적인 속도로 짧은 플라이바이를 야기했다.임무가 더 자주 수행될수록 더 발전된 기구를 사용하여 목표물의 표본이 넓어진다.우연히 Shoemaker-Levy 9와 Schwassmann-Wachmann 3의 결별과 같은 사건들이 우리의 이해를 도왔다.

밀도는 0.6gcm3까지 상당히 낮은 것으로 확인되었습니다.혜성들은 매우 [29]다공성이었고 마이크로스케일과[30] 매크로스케일에서는 [31]깨지기 쉬웠다.

내화물 대 얼음 비는 훨씬 더 [32]높으며, 적어도 3:1,[33] 아마도 ~5:1,[34][35][26] ~6:1 또는 그 [36][37][38]이상일 수 있습니다.

이것은 더러운 눈덩이 모델과는 완전히 반대되는 것이다.로제타 과학 팀은 얼음의 [36]일부분이 있는 광물과 유기물을 가리키는 "미네랄 유기물"이라는 용어를 만들었다.

혜성과 외부 소행성대의 활동적인 소행성은 두 가지 종류의 물체를 가르는 가는 선이 있을 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.

기원.

혜성 또는 혜성의 전구체는 행성이 [39]형성되기 수백만 년 전에 태양계 바깥에서 형성되었습니다.혜성이 어떻게 그리고 언제 형성되었는지는 태양계의 형성, 역학, 그리고 지질학에 뚜렷한 영향을 미치며 논의된다.3차원 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션에 따르면 혜성핵에서 관측된 주요 구조적 특징은 약한 [40][41]혜성의 쌍방향 저속 강착으로 설명될 수 있다.현재 선호되는 생성 메커니즘은 혜성이 행성이 성장한 [42][43][44]최초의 미행성 "구성 요소"의 잔재일 수 있다는 성운 가설이다.

천문학자들은 혜성이 오르트 구름, 산란된 [45]원반, 그리고 외곽의 [46][47][48]주 띠에서 기원한다고 생각한다.

크기

대부분의 혜성핵은 지름이 [49]약 16킬로미터(10마일)밖에 되지 않는 것으로 생각된다.토성 궤도 안으로 들어온 가장 큰 혜성은 95P/키론(200200km), C/2002 VQ94(100100km), 1729년 혜성(100100km), 헤일-밥(6060km), 29P(6060km), 109P/스위프트-터틀(2626km), 28P/NEU이다.

핼리 혜성의 감자 모양 핵(15 × 8 × 8 km)[49][50]에는 같은 양의 얼음과 먼지가 포함되어 있다.

2001년 9월, 딥 스페이스 1호가 근접 비행하는 동안, 보렐리 혜성의 핵을 관찰했고, 그것이 핼리 [49]혜성 핵의 약 절반 크기(8×4×4km)[51]라는 것을 발견했다.보렐리의 핵은 또한 감자 모양이었고 어두운 검은 표면을 [49]가지고 있었다.핼리 혜성처럼, 볼리 혜성은 지각의 구멍이 얼음을 햇빛에 노출시키는 작은 지역에서만 가스를 방출했다.

헤일-밥 혜성의 핵은 [52]지름이 60 ± 20 km로 추정되었다.헤일밥은 비정상적으로 큰 핵에서 먼지와 가스가 많이 뿜어져 나왔기 때문에 육안으로는 밝게 보였다.

P/2007 R5의 핵은 직경이 100~[53]200m에 불과할 것이다.

가장 큰 센타우루스(불안정, 행성횡단, 얼음 소행성)의 지름은 250km에서 300km로 추정된다.가장 큰 것 중 세 개는 10199 Chariklo (258 km), 2060 Chiron (230 km), 그리고 (523727) 2014 NW65 ( km220 km)이다.

알려진 혜성은 평균 0.6g/[54]cm의3 밀도를 가지고 있는 것으로 추정되어 왔다.아래는 크기, 밀도, 질량을 가진 혜성들의 목록입니다.

| 이름. | 치수 km | 밀도 g/cm3 | 덩어리 kg[55] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 핼리 혜성 | 15 × 8 × 8[49][50] | 0.6[56] | 3×1014 |

| 템펠 1 | 7.6×4.9[57] | 0.62[54] | 7.9×1013 |

| 19P/보렐리 | 8×4×4[51] | 0.3[54] | 2×1013 |

| 81P/와일드 | 5.5×4.0×3.3[58] | 0.6[54] | 2.3×1013 |

| 67P/추류모프-게라시멘코 | 67P 기사 참조 | 0.4[59] | (1.0±0.1)×1013[60] |

구성.

이 문서는 갱신할 필요가 있습니다.(2020년 7월) |

한때는 물얼음이 [61]핵의 주요 성분이라고 생각되었다.더러운 눈덩이 모형에서는 얼음이 [62]후퇴할 때 먼지가 분출된다.이를 바탕으로 핼리 혜성 핵의 약 80%는 물 얼음이며, 냉동 일산화탄소(CO)는 또 다른 15%를 차지한다.나머지 대부분은 냉동 이산화탄소, 메탄, [49]암모니아이다.과학자들은 다른 혜성들이 화학적으로 핼리 혜성과 비슷하다고 생각한다.핼리 혜성의 핵은 또한 극도로 어두운 검은색이다.과학자들은 혜성의 표면, 그리고 아마도 대부분의 다른 혜성들이 대부분의 얼음을 덮고 있는 먼지와 바위의 검은 껍질로 덮여 있다고 생각한다.이 혜성들은 이 지각의 구멍이 태양을 향해 회전할 때만 가스를 방출하여 내부의 얼음을 따뜻한 햇빛에 노출시킵니다.

이 가정은 핼리에서 시작하여 순진한 것으로 나타났다.활성은 휘발성 물질과 무거운 유기 [63][64]분율을 포함한 내화물에 대해 선택되므로 혼수 구성은 핵 구성을 나타내지 않습니다.우리의 이해는 대부분 [65]암석 쪽으로 발전했다; 최근의 추정치는 물이 아마도 전형적인 핵 [66][67][62]질량의 20-30%에 불과하다는 것을 보여준다.대신에, 혜성은 주로 유기 물질과 [68]광물입니다.

추류모프-게라시멘코 혜성의 수증기 구성은 로제타 임무에 의해 결정되었으며, 지구에서 발견된 수증기와는 상당히 다릅니다.혜성의 물에 있는 중수소와 수소의 비율은 지상수의 3배인 것으로 밝혀졌다.이것은 지구상의 물이 추류모프-게라시멘코와 같은 [69][70]혜성으로부터 온 것 같지 않게 만든다.

구조.

67P/추류모프-게라시멘코 혜성에서는 생성된 수증기 중 일부가 핵에서 빠져나올 수 있지만,[71] 80%는 표면 아래 층에서 응결된다.이러한 관찰은 표면 가까이에 노출되어 있는 얇은 얼음층이 혜성 활동과 진화의 결과일 수 있으며, 혜성의 [71][72]형성 역사 초기에 전지구적 계층화가 반드시 발생하는 것은 아니라는 것을 암시한다.

필레 착륙선이 67P/추류모프-게라시멘코 혜성에 대해 측정한 결과 먼지 층의 두께는 20cm(7.9인치)에 이를 수 있습니다.그 밑에는 단단한 얼음, 즉 얼음과 먼지의 혼합물이 있다.다공성은 [73]혜성의 중심을 향해 증가하는 것으로 보인다.대부분의 과학자들은 혜성의 핵 구조가 이전 [74]세대의 작은 얼음 행성들로 이루어진 가공된 잔해 더미라고 생각했지만, 로제타 임무는 혜성이 이질적인 [75][76][dubious ]물질들로 이루어진 "고무 더미"라는 생각을 불식시켰다.로제타 미션은 혜성이 이질적인 [77]물질로 이루어진 "고무 더미"일 수 있음을 시사했다.형성 중 및 직후 [78][79]충돌 환경에 대한 데이터는 확정적이지 않습니다.

분할

일부 혜성의 핵은 부서지기 쉬울 수 있으며, 혜성이 [49]갈라지는 것을 관찰함으로써 이 결론을 뒷받침한다.혜성 분열에는 1846년 3D/Biela, Shoemaker가 포함됩니다.1992년 [80]레비 9와 1995년부터 2006년까지 73P/슈바스만-바흐만.[81]그리스 역사학자 에포루스는 기원전 [82]372-373년 겨울까지 혜성이 갈라졌다고 보고했다.혜성은 열 스트레스, 내부 가스 압력 또는 충격으로 [83]인해 분열되는 것으로 의심됩니다.

혜성 42P/Neujmin과 53P/Van Biesbroeck는 모혜성의 조각으로 보인다.수치적 통합은 두 혜성이 1850년 1월에 목성에 다소 가까이 접근했고, 1850년 이전에는 두 궤도가 거의 [84]같았음을 보여준다.

알베도

혜성핵은 태양계에 존재하는 것으로 알려진 가장 어두운 물체 중 하나이다.지오토 탐사선은 핼리 혜성의 핵이 [85]자신 위로 떨어지는 빛의 약 4%를 반사한다는 것을 발견했고, 딥 스페이스 1은 보렐리 혜성의 표면이 자신 [85]위로 떨어지는 빛의 2.5-3.0%만을 반사한다는 것을 발견했습니다. 이에 비해, 신선한 아스팔트는 자신 위로 떨어지는 빛의 7%를 반사합니다.복잡한 유기 화합물은 어두운 표면 물질로 생각된다.태양열은 타르나 원유와 같이 매우 어두운 경향이 있는 무거운 긴 사슬 유기물을 남기고 휘발성 화합물을 쫓아냅니다.혜성 표면은 매우 어둡기 때문에 가스를 배출하는 데 필요한 열을 흡수할 수 있습니다.

지구에 가까운 소행성의 약 6 퍼센트는 더 이상 가스가 [86]배출되지 않는 혜성의 멸종된 핵으로 생각됩니다.알베도가 이렇게 낮은 두 개의 지구 근접 소행성에는 14827 히프노스와 3552 돈키호테가 [dubious ]있다.

발견과 탐색

혜성 핵에 비교적 가까운 첫 번째 임무는 우주 탐사선 [87]지오토였다.핵이 [87]596km 가까이에서 촬영된 것은 이번이 처음이었다.데이터는 제트, 저알베도 표면, 유기 화합물 [87][88]등을 처음으로 보여주는 폭로가 되었다.

비행 중 지오토는 [87]함슈타트와 일시적으로 통신이 두절된 1그램 파편을 포함해 입자에 의해 최소 12,000회 충돌했다.핼리는 7개의 제트기에서 초당[89] 3톤의 물질을 방출하여 장기간 [2]흔들리게 하는 것으로 계산되었습니다.그리그-스켈러럽 혜성의 핵은 핼리 이후 발견되었으며 지오토는 100~200km에 [87]근접했다.

로제타와 필레 우주선의 결과는 67P/추류모프-게라시멘코의 핵에는 자기장이 없다는 것을 보여주며,[3][4] 이는 미행성체의 초기 형성에 자력이 작용하지 않았음을 시사한다.또한, 로제타의 ALICE 분광기는 태양 복사에 의한 물 분자의 광이온화에서 생성된 전자(혜성 핵 위 1km 이내)가 혜성 핵에서 방출된 물과 이산화탄소 분자의 분해에 책임이 있다는 것을 알아냈다.혼수 [5][6]상태

| 템펠 1 딥 임팩트 | 템펠 1 스타더스트 | 보렐리 딥 스페이스 1 | 와일드 2 스타더스트 | 하틀리 2 딥 임팩트 | C-G 로제타 |

이미 방문한 혜성은 다음과 같습니다.

- 핼리 혜성

- 26P/Grigg-Skjellerup

- 템펠 1(충격기로도 타격)

- 19P/보렐리

- 81P/와일드

- 103P/하틀리

- C/2013 A1 (측천) - 화성 우주선과의 계획되지 않은 만남

- 67P/추류모프-게라시멘코(착륙도 완료)

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Robert Roy Britt (29 November 2001). "Comet Borrelly Puzzle: Darkest Object in the Solar System". Space.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ a b "ESA Science & Technology: Halley". ESA. 10 March 2006. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ a b Bauer, Markus (14 April 2015). "Rosetta and Philae Find Comet Not Magnetised". European Space Agency. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ a b Schiermeier, Quirin (14 April 2015). "Rosetta's comet has no magnetic field". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17327. S2CID 123964604.

- ^ a b Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne; Fohn, Joe; Bauer, Markus (2 June 2015). "NASA Instrument on Rosetta Makes Comet Atmosphere Discovery". NASA. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ a b Feldman, Paul D.; A'Hearn, Michael F.; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Feaga, Lori M.; Parker, Joel Wm.; et al. (2 June 2015). "Measurements of the near-nucleus coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko with the Alice far-ultraviolet spectrograph on Rosetta" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 583: A8. arXiv:1506.01203. Bibcode:2015A&A...583A...8F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525925. S2CID 119104807.

- ^ Jordans, Frank (30 July 2015). "Philae probe finds evidence that comets can be cosmic labs". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Science on the Surface of a Comet". European Space Agency. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Bibring, J.-P.; Taylor, M.G.G.T.; Alexander, C.; Auster, U.; Biele, J.; Finzi, A. Ercoli; Goesmann, F.; Klingehoefer, G.; Kofman, W.; Mottola, S.; Seidenstiker, K.J.; Spohn, T.; Wright, I. (31 July 2015). "Philae's First Days on the Comet – Introduction to Special Issue". Science. 349 (6247): 493. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..493B. doi:10.1126/science.aac5116. PMID 26228139.

- ^ Rickman, H (2017). "1.1.1 The Comet Nucleus". Origin and Evolution of Comets: 10 years after the Nice Model, and 1 year after Rosetta. World Scientific Publishing Co Singapore. ISBN 978-9813222571.

- ^ Lyttleton, RA (1948). "On the Origin of Comets". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 108 (6): 465–75. Bibcode:1948MNRAS.108..465L. doi:10.1093/mnras/108.6.465.

- ^ Lyttleton, R (1951). "On the Structure of Comets and the Formation of Tails". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 111 (3): 268–77. Bibcode:1951MNRAS.111..268L. doi:10.1093/mnras/111.3.268.

- ^ Lyttleton, R (1972). The Comets and Their Origin. Cambridge University Press New York. ISBN 9781107615618.

- ^ Bailey, M; Clube, S; Napier, W (1990). "8.3 Lyttleton's Accretion Theory". The Origin of Comets. Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-034859-9.

- ^ Whipple, F (1950). "A Comet Model. I: the Acceleration of Comet Encke". Astrophysical Journal. 111: 375–94. Bibcode:1950ApJ...111..375W. doi:10.1086/145272.

- ^ Whipple, F (1951). "A Comet Model. II: Physical Relations for Comets and Meteors". Astrophysical Journal. 113: 464–74. Bibcode:1951ApJ...113..464W. doi:10.1086/145416.

- ^ 백런드 1881

- ^ Delsemme, A (1 July 1972). "Present Understanding of Comets". Comets: Scientific Data and Missions: 174. Bibcode:1972csdm.conf..174D.

- ^ a b Wood, J (December 1986). Comet nucleus models: a review. ESA Workshop on the Comet Nucleus Sample Return Mission. pp. 123–31.

- ^ a b Kresak, L; Kresakova, M (1987). ESA SP-278: Symposium on the Diversity and Similarity of Comets. ESA. p. 739.

- ^ Rickman, H (2017). "2.2.3 Dust Production Rates". Origin and Evolution of Comets: 10 years after the Nice Model, and 1 year after Rosetta. World Scientific Publishing Co Singapore. ISBN 978-9813222571. 혜성 핵이 얼어붙은 눈덩이로 상상된 지 오래다.

- ^ Hartmann, W; Cruikshank, D; Degewij, J (1982). "Remote comets and related bodies: VJHK colorimetry and surface materials". Icarus. 52 (3): 377–08. Bibcode:1982Icar...52..377H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(82)90002-1.

- ^ Fanale, F; Salvail, J (1984). "An idealized short-period comet model". Icarus. 60: 476. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(84)90157-X.

- ^ Cruikshank, D; Hartmann, W; Tholen, D (1985). "Color, albedo, and nucleus size of Halley's comet". Nature. 315 (6015): 122. Bibcode:1985Natur.315..122C. doi:10.1038/315122a0. S2CID 4357619.

- ^ Greenberg, J (May 1986). "Predicting that comet Halley is dark". Nature. 321 (6068): 385. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..385G. doi:10.1038/321385a0. S2CID 46708189.

- ^ a b Rickman, H (2017). "4.2 Dust Mantling". Origin and Evolution of Comets: 10 years after the Nice Model, and 1 year after Rosetta. World Scientific Publishing Co Singapore. ISBN 978-9813222571. "먼지 맨틀링이라는 용어는 35년 이상 전부터 일반적으로 사용되고 있습니다."

- ^ Tholen, D; Cruikshank, D; Hammel, H; Hartmann, W; Lark, N; Piscitelli, J (1986). "A comparison of the continuum colours of P/Halley, other comets and asteroids". ESA SP-250 Vol. III. ESA. p. 503.

- ^ Whipple, F (October 1987). "The Cometary Nucleus - Current Concepts". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 187 (1): 852.

- ^ A'Hearn, M (2008). "Deep Impact and the Origin and Evolution of Cometary Nuclei". Space Science Reviews. 138 (1): 237. Bibcode:2008SSRv..138..237A. doi:10.1007/s11214-008-9350-3. S2CID 123621097.

- ^ Trigo-Rodriguez, J; Blum, J (February 2009). "Tensile strength as an indicator of the degree of primitiveness of undifferentiated bodies". Planet. Space Sci. 57 (2): 243–49. Bibcode:2009P&SS...57..243T. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2008.02.011.

- ^ Weissman, P; Asphaug, E; Lowry, S (2004). "Structure and Density of Cometary Nuclei". Comets II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 337.

- ^ Bischoff, D; Gundlach, B; Neuhaus, M; Blum, J (February 2019). "Experiment on cometary activity: ejection of dust aggregates from a sublimating water-ice surface". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 483 (1): 1202. arXiv:1811.09397. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.483.1202B. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty3182. S2CID 119278016.

- ^ Rotundi, A; Sierks H; Della Corte V; Fulle M; GutierrezP; et al. (23 January 2015). "Dust Measurements in the coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko inbound to the Sun". Science. 347 (6220): aaa3905. Bibcode:2015Sci...347a3905R. doi:10.1126/science.aaa3905. PMID 25613898. S2CID 206634190.

- ^ Fulle, M; Della Corte, V; Rotundi, A; Green, S; Accolla, M; Colangeli, L; Ferrari, M; Ivanovski, S; Sordini, R; Zakharov, V (2017). "The dust-to-ices ratio in comets and Kuiper belt objects". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 469: S45-49. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.469S..45F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx983.

- ^ Fulle, M; Marzari, F; Della Corte, V; Fornasier, S (April 2016). "Evolution of the dust size distribution of comet 67P/C-G from 2.2au to perihelion" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 821: 19. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/821/1/19. S2CID 125072014.

- ^ a b Fulle, M; Altobelli, N; Buratti, B; Choukroun, M; Fulchignoni, M; Grün, E; Taylor, M; et al. (November 2016). "Unexpected and significant findings in comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko: an interdisciplinary view". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 462: S2-8. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.462S...2F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1663.

- ^ Fulle, M; Blum, J; Green, S; Gundlach, B; Herique, A; Moreno, F; Mottola, S; Rotundi, A; Snodgrass, C (January 2019). "The refractory-to-ice mass ratio in comets" (PDF). Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 482 (3): 3326–40. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.482.3326F. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty2926.

- ^ Choukroun, M; Altwegg, K; Kührt, E; Biver, N; Bockelée-Morvan, D; et al. (2020). "Dust-to-Gas and Refractory-to-ice Mass Ratios of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from Rosetta Obs". Space Sci Rev. 216: 44. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00662-1. S2CID 216338717.

- ^ "How comets were assembled". University of Bern. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016 – via Phys.org.

- ^ Jutzi, M.; Asphaug, E. (June 2015). "The shape and structure of cometary nuclei as a result of low-velocity accretion". Science. 348 (6241): 1355–1358. Bibcode:2015Sci...348.1355J. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4747. PMID 26022415. S2CID 36638785.

- ^ Weidenschilling, S. J. (June 1997). "The Origin of Comets in the Solar Nebula: A Unified Model". Icarus. 127 (2): 290–306. Bibcode:1997Icar..127..290W. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5712.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (15 November 2014). "Comets: Facts About The 'Dirty Snowballs' of Space". Space.com. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Nuth, Joseph A.; Hill, Hugh G. M.; Kletetschka, Gunther (20 July 2000). "Determining the ages of comets from the fraction of crystalline dust". Nature. 406 (6793): 275–276. Bibcode:2000Natur.406..275N. doi:10.1038/35018516. PMID 10917522. S2CID 4430764.

- ^ "How Asteroids and Comets Formed". Science Clarified. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Levison, Harold F.; Donnes, Luke (2007). "Comet Populations and Cometary Dynamics". In McFadden, Lucy-Ann Adams; Weissman, Paul Robert; Johnson, Torrence V. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Solar System (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 575–588. ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3.

- ^ Dones, L; Brasser, R; Kaib, N; Rickman, H (2015). "Origi and Evolu of the Cometar Reserv". Space Science Reviews. 197: 191–69. doi:10.1007/s11214-015-0223-2. S2CID 123931232.

- ^ Meech, K (2017). "Setting the scene: what did we know before Rosetta?". 375. Section 6.

{{cite journal}}: 인용저널 필요 (도움말)특집호:로제타 이후의 혜성 과학 - ^ Hsieh, H; Novaković, B; Walsh, K; Schörghofer, N (2020). "Potential Themis-family Asteroid Contribution to the Jupiter-family Comet Population". The Astronomical Journal. 159 (4): 179. arXiv:2002.09008. Bibcode:2020AJ....159..179H. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab7899. PMC 7121251. PMID 32255816. S2CID 211252398.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yeomans, Donald K. (2005). "Comets (World Book Online Reference Center 125580)". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 April 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ a b "What Have We Learned About Halley's Comet?". Astronomical Society of the Pacific (No. 6 – Fall 1986). 1986. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ a b Weaver, H. A.; Stern, S.A.; Parker, J. Wm. (2003). "Hubble Space Telescope STIS Observations of Comet 19P/BORRELLY during the Deep Space 1 Encounter". The Astronomical Journal. 126 (1): 444–451. Bibcode:2003AJ....126..444W. doi:10.1086/375752. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ Fernández, Yanga R. (2002). "The Nucleus of Comet Hale-Bopp (C/1995 O1): Size and Activity". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 89 (1): 3–25. Bibcode:2002EM&P...89....3F. doi:10.1023/A:1021545031431. S2CID 189899565.

- ^ "SOHO's new catch: its first officially periodic comet". European Space Agency. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d D. T. Britt; G. J. Consol-magno SJ; W. J. Merline (2006). "Small Body Density and Porosity: New Data, New Insights" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVII. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ 핼리:15x8x8km*의 타원체 부피를 이용하여 0.6g/cm의3 돌무더기 밀도로 3.02E+14kg의 질량(m=d*v)을 산출한다.

템펠 1: 구면 지름 6.25km, 구면 부피 * 0.62g/cm의3 밀도는 7.9E+13kg의 질량을 산출합니다.

19P/보렐리 : 8x4x4km*의 타원체 부피를 이용하여 0.3g/cm의3 밀도로 2.0E+13kg의 질량을 산출한다.

81P/Wild : 5.5x4.0x3의 타원체의 부피를 사용한다.3km * 0.6g/cm의3 밀도는 2.28E+13kg의 질량을 산출한다. - ^ RZ Sagdeev; PE Elyasberg; VI Moroz. (1988). "Is the nucleus of Comet Halley a low density body?". Nature. 331 (6153): 240–242. Bibcode:1988Natur.331..240S. doi:10.1038/331240a0. S2CID 4335780.

- ^ "Comet 9P/Tempel 1". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ "Comet 81P/Wild 2". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ Baldwin, Emily (6 October 2014). "Measuring Comet 67P/C-G". European Space Agency. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ Baldwin, Emily (21 August 2014). "Determining the mass of comet 67P/C-G". European Space Agency. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Wood, J A (December 1986). "Comet nucleus models: a review.". ESA Proceedings of an ESA workshop on the Comet Nucleus Sample Return Mission. ESA. pp. 123–31.

water-ice as the predominant constituent

- ^ a b Bischoff, D; Gundlach, B; Neuhaus, M; Blum, J (February 2019). "Experiments on cometary activity: ejection of dust aggregates from a sublimating water-ice surface". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 483 (1): 1202–10. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty3182.

In the past, it was believed that comets are dirty snowballs and that the dust is ejected when the ice retreats." "...it has become evident that comets have a much higher dust-to-ice ratio than previously thought

- ^ Bockelée-Morvan, D; Biver, N (May 2017). "The composition of cometary ices". Phil. Trans. R. Astron. Soc. A-Mathematics Physics and Engineering Science. 375 (2097). doi:10.1098/rsta.2016.0252. PMID 28554972. S2CID 2207751.

Molecular abundances are measured in cometary atmospheres. The extent to which they are representative of the nucleus composition has been the subject of many theoretical studies.

- ^ O'D. Alexander, C; McKeegan, K; Altwegg, K (February 2019). "Water Reservoirs in Small Planetary Bodies: Meteorites, Asteroids, and Comets". Space Science Reviews. 214 (1): 36. doi:10.1007/s11214-018-0474-9. PMC 6398961. PMID 30842688.

While the coma is clearly heterogeneous in composition, no firm statement can be made about the compositional heterogeneity of the nucleus at any given time." "what can be measured in their comas remotely may not be representative of their bulk compositions.

- ^ A'Hearn, M (May 2017). "Comets: looking ahead". Phil. Trans. R. Astron. Soc. A-Mathematics Physics and Engineering Science. 375 (2097). doi:10.1098/rsta.2016.0261. PMC 5454229. PMID 28554980.

our understanding has been evolving more toward mostly rock

- ^ Jewitt, D; Chizmadia, L; Grimm, R; Prialnik, D (2007). "Water in the Small Bodies of the Solar System". Protostars and Planets V. University of Arizona Press. pp. 863–78.

Recent estimates... show that water is less important, perhaps carrying only 20-30% of the mass in typical nuclei (Sykes et al., 1986).

- ^ Fulle, M; Della Corte, V; Rotundi, A; Green, S; Accolla, M; Colangeli, L; Ferrari, M; Ivanovski, S; Sordini, R; Zakharov, V (2017). "The dust-to-ices ratio in comets and Kuiper belt objects". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 469: S45-49. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.469S..45F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx983.

- ^ Filacchione, G; Groussin, O; Herny, C; Kappel, D; Mottola, S; Oklay, N; Pommerol, A; Wright, I; Yoldi, Z; Ciarniello, M; Moroz, L; Raponi, A (2019). "Comet 67P/CG Nucleus Composition and Comparison to Other Comets" (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 215: Article number 19. doi:10.1007/s11214-019-0580-3. S2CID 127214832.

a predominance of organic materials and minerals.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (10 December 2014). "The mystery of where Earth's water came from deepens". Excite News. Associated Press. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Bauer, Markus (10 December 2014). "Rosetta Instrument Reignites Debate on Earth's Oceans". NASA. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b Filacchione, Gianrico; Capaccioni, Fabrizio; Taylor, Matt; Bauer, Markus (13 January 2016). "Exposed ice on Rosetta's comet confirmed as water" (Press release). European Space Agency. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Filacchione, G.; de Sanctis, M. C.; Capaccioni, F.; Raponi, A.; Tosi, F.; et al. (13 January 2016). "Exposed water ice on the nucleus of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko". Nature. 529 (7586): 368–372. Bibcode:2016Natur.529..368F. doi:10.1038/nature16190. PMID 26760209. S2CID 4446724.

- ^ Baldwin, Emily (18 November 2014). "Philae settles in dust-covered ice". European Space Agency. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Krishna Swamy, K. S. (May 1997). Physics of Comets. World Scientific Series in Astronomy and Astrophysics, Volume 2 (2nd ed.). World Scientific. p. 364. ISBN 981-02-2632-2.

- ^ Khan, Amina (31 July 2015). "After a bounce, Rosetta". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Rosetta's frequently asked questions". European Space Agency. 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Rickman, H; Marchi, S; AHearn, M; Barbieri, C; El-Maarry, M; Güttler, C; Ip, W (2015). "Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko: Constraints on its origin from OSIRIS observations". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 583: Article 44. arXiv:1505.07021. Bibcode:2015A&A...583A..44R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526093. S2CID 118394879.

- ^ Jutzi, M; Benz, W; Toliou, A; Morbidelli, A; Brasser, R (2017). "How primordial is the structure of comet 67P? Combined collisional and dynamical models suggest a late formation". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 597: A# 61. arXiv:1611.02604. Bibcode:2017A&A...597A..61J. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201628963. S2CID 119347364.

- ^ Keller, H; Kührt, E (2020). "Cometary Nuclei- From Giotto to Rosetta". Space Science Reviews. 216 (1): Article 14. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216...14K. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-0634-6. S2CID 213437916. 제6.3조 주요 개방점 잔류 "형성 중 및 직후 충돌 환경에 관한 데이터는 확정적이지 않다"

- ^ JPL Public Information Office. "Comet Shoemaker-Levy Background". JPL/NASA. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Whitney Clavin (10 May 2006). "Spitzer Telescope Sees Trail of Comet Crumbs". Spitzer Space Telescope at Caltech. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Donald K. Yeomans (1998). "Great Comets in History". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ H. Boehnhardt. "Split Comets" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Institute (Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie Heidelberg). Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ J. Pittichova; K.J. Meech; G.B. Valsecch; E.M. Pittich (1–6 September 2003). "Are Comets 42P/Neujmin 3 and 53P/Van Biesbroeck Parts of one Comet?". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 35 #4. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Comet May Be the Darkest Object Yet Seen". The New York Times. 14 December 2001. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ Whitman, Kathryn; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Jedicke, Robert (2006). "The Size-Frequency Distribution of Dormant Jupiter Family Comets". Icarus. 183 (1): 101–114. arXiv:astro-ph/0603106. Bibcode:2006Icar..183..101W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.02.016. S2CID 14026673.

- ^ a b c d e esa. "Giotto overview". European Space Agency.

- ^ 유기 화합물(일반적으로 유기물이라고 함)은 생명을 의미하지 않습니다. 그것은 단지 화학의 한 종류입니다. 유기 화학을 참조하십시오.

- ^ J. A. M. McDonnell; et al. (15 May 1986). "Dust density and mass distribution near comet Halley from Giotto observations". Nature. 321: 338–341. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..338M. doi:10.1038/321338a0. S2CID 122092751.

외부 링크

- 핼리 혜성의 핵(15×8×8km)

- 야생 2 혜성의 핵(5.5×4.0×3.3km)

- 국제 혜성 분기: 분할 혜성

- 67/P by Rosetta2 (ESA)