기부효과

Endowment effect심리학과 행동경제학에서 기부효과(분할혐오라고도 하며 사회심리학에서[1] 단순한 소유효과와 관련됨)는 사람들이 소유하지 않은 동일한 대상을 획득하기보다는 소유하는 대상을 보유할 가능성이 더 높다는 발견이다.[2][3][4][5] 기부 이론은 "소유와 관련된 손실 회피가 관찰된 교환 비대칭성을 설명한다는 추정 이론의 적용"[6]으로 정의할 수 있다.

이것은 일반적으로 두 가지 방법으로 설명된다.[3] 가치평가 패러다임에서, 어떤 대상을 취득하기 위해 지불하려는 사람들의 최대 의지(WTP)는 일반적으로 그들이 소유할 때 같은 대상을 포기하기 위해 기꺼이 받아들이는 최소 금액(WTA)보다 낮다. (부착할 이유가 없거나, 항목이 단지 몇 분 전에 획득된 경우에도).[5] 교환 패러다임에서, 재화를 준 사람들은 그것을 비슷한 가치의 또 다른 재화와 바꾸기를 꺼린다. 예를 들어, 처음에 스위스 초콜릿 바를 준 참가자들은 일반적으로 커피 머그컵과 교환하기를 꺼려하는 반면, 커피 머그컵을 처음 준 참가자들은 일반적으로 초콜릿 바와 교환하기를 꺼렸다.[7]

기부금 효과를 이끌어내기 위해 더 논란이 되는 세 번째 패러다임은 주로 심리학, 마케팅 및 조직 행동의 실험에 사용되는 단순한 소유권 패러다임이다. 이 패러다임에서 무작위로 재화를 받기 위해 배정된 사람들("소유자")은 재화를 받기 위해 무작위로 배정되지 않은 사람들("통제")[1][3]보다 더 긍정적으로 평가한다. 이 패러다임과 처음 두 패러다임의 구별은 인센티브와 맞지 않는다는 것이다. 즉, 참여자가 진정으로 선을 좋아하거나 가치를 평가하는 정도를 밝히도록 명시적으로 인센티브를 주지 않는다.

기부 효과는 수용 또는 지불하려는 행동 모델 의지와 동일할 수 있다(WTAP). 이는 때때로 소비자 또는 개인이 다른 결과에 대해 얼마나 기꺼이 참거나 잃는지를 알아내기 위해 사용되는 공식이다. 그러나 이 모델은 최근 들어 잠재적으로 부정확하다는 비난을 받고 있다.[8][6]

Examples

One of the most famous examples of the endowment effect in the literature is from a study by Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch & Richard Thaler,[5] in which participants were given a mug and then offered the chance to sell it or trade it for an equally valued alternative (pens). They found that the amount participants required as compensation for the mug once their ownership of the mug had been established ("willingness to accept") was approximately twice as high as the amount they were willing to pay to acquire the mug ("willingness to pay").

Other examples of the endowment effect include work by Ziv Carmon and Dan Ariely,[9] who found that participants' hypothetical selling price (willingness to accept or WTA) for NCAA final four tournament tickets were 14 times higher than their hypothetical buying price (willingness to pay or WTP). Also, work by Hossain and List (Working Paper) discussed in the Economist in 2010,[10] showed that workers worked harder to maintain ownership of a provisional awarded bonus than they did for a bonus framed as a potential yet-to-be-awarded gain. In addition to these examples, the endowment effect has been observed using different goods[11] in a wide range of different populations, including children,[12] great apes,[13] and new world monkeys.[14]

Background

The endowment effect has been observed from ancient times:

For most things are differently valued by those who have them and by those who wish to get them: what belongs to us, and what we give away, always seems very precious to us.

— Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics book IX (F. H. Peters translation)

Psychologists first noted the difference between consumers' WTP and WTA as early as the 1960s.[15][16] The term endowment effect however was first explicitly coined by the economist Richard Thaler in reference to the under-weighting of opportunity costs as well as the inertia introduced into a consumer's choice processes when goods included in their endowment become more highly valued than goods that are not.[17] In the years that followed, extensive investigations into the endowment effect have been conducted producing a wealth of interesting empirical and theoretical findings.[11]

Theoretical explanations

Loss aversion

It was proposed by Kahneman and his colleagues that the endowment effect is, in part, due to the fact that once a person owns an item, forgoing it feels like a loss, and humans are loss-averse.[5] They go on to suggest that the endowment effect, when considered as a facet of loss-aversion, would thus violate the Coase theorem, and was described as inconsistent with standard economic theory which asserts that a person's willingness to pay (WTP) for a good should be equal to their willingness to accept (WTA) compensation to be deprived of the good, a hypothesis which underlies consumer theory and indifference curves. However, these claims have been disputed and other researchers claim that psychological inertia,[18] differences in reference prices relied on by buyers and sellers,[4] and ownership (attribution of the item to self) and not loss aversion are the key to this phenomenon.[19]

Psychological inertia

David Gal proposed a psychological inertia account of the endowment effect.[20][21] In this account, sellers require a higher price to part with an object than buyers are willing to pay because neither has a well-defined, precise valuation for the object and therefore there is a range of prices over which neither buyers nor sellers have much incentive to trade. For example, in the case of Kahneman et al.'s (1990) classic mug experiments (where sellers demanded about $7 to part with their mug whereas buyers were only willing to pay, on average, about $3 to acquire a mug) there was likely a range of prices for the mug ($4 to $6) that left the buyers and sellers without much incentive to either acquire or part with it. Buyers and sellers therefore maintained the status quo out of inertia. Conversely, a high price ($7 or more) yielded a meaningful incentive for an owner to part with the mug; likewise, a relatively low price ($3 or less) yielded a meaningful incentive for a buyer to acquire the mug.

Reference-dependent accounts

According to reference-dependent theories, consumers first evaluate the potential change in question as either being a gain or a loss. In line with prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman, 1979[22]), changes that are framed as losses are weighed more heavily than are the changes framed as gains. Thus an individual owning "A" amount of a good, asked how much he/she would be willing to pay to acquire "B", would be willing to pay a value (B-A) that is lower than the value that he/she would be willing to accept to sell (C-A) units; the value function for perceived gains is not as steep as the value function for perceived losses.

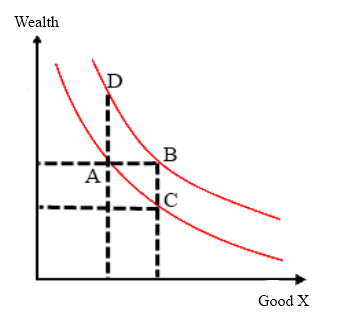

Figure 1 presents this explanation in graphical form. An individual at point A, asked how much he/she would be willing to accept (WTA) as compensation to sell X units and move to point C, would demand greater compensation for that loss than he/she would be willing to pay for an equivalent gain of X units to move him/her to point B. Thus the difference between (B-A) and (C-A) would account for the endowment effect. In other words, he/she expects more money while selling; but wants to pay less while buying the same amount of goods.

Neoclassical explanations

Hanemann (1991),[23] develops a neoclassical explanation for the endowment effect, accounting for the effect without invoking prospect theory.

Figure 2 presents this explanation in graphical form. In the figure, two indifference curves for a particular good X and wealth are given. Consider an individual who is given goods X such they move from point A (where they have X0 of good X) to point B (where they have the same wealth and X1 of good X). Their WTP represented by the vertical distance from B to C, because (after giving up that amount of wealth) the individual is indifferent about being at A or C. Now consider an individual who gives up goods such that they move from B to A. Their WTA represented by the (larger) vertical distance from A to D because (after receiving that much wealth) they are indifferent about either being at point B or D. Shogren et al. (1994)[24] has reported findings that lend support to Hanemann's hypothesis. However, Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1991)[7] find that the endowment effect continues even when wealth effects are fully controlled for.

When goods are indivisible, a coalitional game can be set up so that a utility function can be defined on all subsets of the goods. Hu (2020)[25] shows the endowment effect when the utility function is superadditive, i.e., the value of the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Hu (2020) also introduces a few unbiased solutions which mitigate endowment bias.

Connection-based, or "psychological ownership" theories

Connection-based theories propose that the attachment or association with the self-induced by owning a good is responsible for the endowment effect (for a review, see Morewedge & Giblin, 2015[3]). Work by Morewedge, Shu, Gilbert and Wilson (2009)[19] provides support for these theories, as does work by Maddux et al. (2010).[26] For example, research participants who were given one mug and asked how much they would pay for a second mug ("owner-buyers") were WTP as much as "owners-sellers," another group of participants who were given a mug and asked how much they were WTA to sell it (both groups valued the mug in question more than buyers who were not given a mug).[19] Others have argued that the short duration of ownership or highly prosaic items typically used in endowment effect type studies is not sufficient to produce such a connection, conducting research demonstrating support for those points (e.g. Liersch & Rottenstreich, Working Paper).

Two paths by which attachment or self-associations increase the value of a good have been proposed (Morewedge & Giblin, 2015).[3] An attachment theory suggests that ownership creates a non-transferable valenced association between the self and the good. The good is incorporated into the self-concept of the owner, becoming part of her identity and imbuing it with attributes related to her self-concept. Self-associations may take the form of an emotional attachment to the good. Once an attachment has formed, the potential loss of the good is perceived as a threat to the self.[1] A real-world example of this would be an individual refusing to part with a college T-shirt because it supports one's identity as an alumnus of that university. A second route by which ownership may increase value is through a self-referential memory effect (SRE) – the better encoding and recollection of stimuli associated with the self-concept.[27] People have a better memory for goods they own than goods they do not own. The self-referential memory effect for owned goods may act thus as an endogenous framing effect. During a transaction, attributes of a good may be more accessible to its owners than are other attributes of the transaction. Because most goods have more positive than negative features, this accessibility bias should result in owners more positively evaluating their goods than do non-owners.[3]

셀러에 대한 시장 수요에 대한 민감도 증대

판매자는 복수의 잠재적 구매자의 욕구에 따라 가격을 결정할 수 있지만, 구매자는 자신의 취향을 고려할 수 있다. 이것은 일반적으로 시장 가격이 자신의 독특한 가격 추정치보다 높기 때문에 매매 가격 간의 차이로 이어질 수 있다. 이 계좌에 따르면 기부효과는 시세에 비해 구매자에게 덜 부담되거나 판매자가 개인의 취향에 비해 과도하게 부담하는 것으로 볼 수 있다. 최근의 두 가지 연구 라인이 이 주장을 뒷받침한다. 위버와 프레드릭(2012년)은 참가자들에게 제품 소매가격을 제시한 뒤 이들 제품에 대한 구매 가격이나 판매 가격을 명시해 달라고 요청했다. 그 결과는 판매자들의 평가액이 구매자들의 평가보다 알려진 소매 가격에 더 가깝다는 것을 보여주었다. 두 번째 연구 라인은 복권 구매와 판매의 메타 분석이다.[28] 30개 이상의 경험적 연구를 검토한 결과, 판매 가격이 복권의 표준 가격인 예상 가치에 더 가깝다는 것을 보여주었다. 따라서 기부 효과는 표준 가격에 비해 구매자들의 낮은 가격 복권 경향과 일치했다. 이러한 구매자들의 경향이 낮은 가격을 나타내는 한 가지 가능한 이유는 그들의 위험 혐오 때문이다. 이와는 대조적으로, 판매자들은 시장이 잠재적인 위험 중립성을 가진 구매자를 포함할 만큼 충분히 이질적이라고 가정할 수 있으며, 따라서 위험 중립 기대치에 더 가깝게 가격을 조정할 수 있다.

편향된 정보처리 이론

기부금 효과에 대한 여러 인지 계정은 기부금 상태가 거래에 관한 정보의 검색, 주의, 기억 및 가중치를 변화시키는 방법에 의해 유도된다는 것을 암시한다. 재화의 취득(예: 다른 재화보다는 구매, 선택)에 의해 유발되는 프레임은 재화를 취득하지 않고 자신의 재화를 보유하려는 결정에 유리한 정보의 인지적 접근성을 높일 수 있다. 이와는 대조적으로, 재화의 처분에 의해 야기되는 프레임(예: 판매)은 재화를 거래하거나 돈으로 처분하기 보다는 유지하기로 한 결정에 유리한 정보의 인지적 접근성을 증가시킬 수 있다(검토의 경우, 모어웨지 & 기브린, 2015 참조).[3] 예를 들어,[29] 존슨과 동료(2007)는 머그잔 구매 예정자들이 머그잔 구입 이유를 상기하기 전에 돈을 보관해야 할 이유를 상기하는 경향이 있는 반면, 판매자들은 머그잔을 돈으로 팔 이유 이전에 보관해야 할 이유를 상기하는 경향이 있다는 것을 발견했다.

Evolutionary arguments

Huck, Kirchsteiger & Oechssler (2005)[30] have raised the hypothesis that natural selection may favor individuals whose preferences embody an endowment effect given that it may improve one's bargaining position in bilateral trades. Thus in a small tribal society with a few alternative sellers (i.e. where the buyer may not have the option of moving to an alternative seller), having a predisposition towards embodying the endowment effect may be evolutionarily beneficial. This may be linked with findings (Shogren, et al., 1994[24]) that suggest the endowment effect is less strong when the relatively artificial sense of scarcity induced in experimental settings is lessened. Countervailing evidence for an evolutionary account is provided by studies showing that the endowment effect is moderated by exposure to modern exchange markets (e.g., hunter gatherer tribes with market exposure are more likely to exhibit the endowment effect than tribes that do not),[31] and that the endowment effect is moderated by culture (Maddux et al., 2010[26]).

Criticisms

Some economists have questioned the effect's existence.[32][33] Hanemann (1991)[23] noted that economic theory only suggests that WTP and WTA should be equal for goods which are close substitutes, so observed differences in these measures for goods such as environmental resources and personal health can be explained without reference to an endowment effect. Shogren, et al. (1994)[24] noted that the experimental technique used by Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler (1990)[5] to demonstrate the endowment effect created a situation of artificial scarcity. They performed a more robust experiment with the same goods used by Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler (chocolate bars and mugs) and found little evidence of the endowment effect in substitutable goods, acknowledging the endowment effect as valid for goods without substitutes—non-renewable Earth resources being an example of these. Others have argued that the use of hypothetical questions and experiments involving small amounts of money tells us little about actual behavior (e.g. Hoffman and Spitzer, 1993, p. 69, n. 23[11]) with some research supporting these points (e.g., Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler, 1990,[5] Harless, 1989[34]) and others not (e.g. Knez, Smith and Williams, 1985[35]). More recently, Plott and Zeiler have challenged the endowment effect theory by arguing that observed disparities between WTA and WTP measures are not reflective of human preferences, but rather such disparities stem from faulty experimental designs.[8][36]

시사점

Herbert Hovenkamp([37]1991)는 기부금 효과의 존재가 특히 복지 경제학과 관련하여 법과 경제에 중요한 영향을 미친다고 주장해왔다. 그는 기부 효과가 있다는 것은 복지 분석의 신고전주의 도구를 무용지물로 만드는 무관심 곡선이 없다는 것을 의미한다고 주장하며, 이는 아무리 Hanemann, 1991년[23] 참조) 법원이 대신 WTA를 가치의 척도로 사용해야 한다고 결론지었다. 그러나 [38]Fischel(1995)은 WTA를 가치의 척도로 사용하는 것이 한 나라의 인프라 개발과 경제성장을 저해할 수 있다는 대척점을 제기한다. 기부금 효과는 무관심 곡선의 형태를 상당히[39] 변화시킨다. 마찬가지로, 기부금에 대한 전략적 재분배에 초점을 맞추고 있는 또 다른 연구도 기부금 보유를 변경할 경우 경제의 대리인 복지가 잠재적으로 증가할 수 있는 경우를 분석한다.

미국의 역모기지 기회에 대한 수요 부족(주택 소유자가 연금을 대가로 은행에 재산을 되파는 계약)에 대한 설명(헉, 키르치스티거&옥슬러, 2005년)도 가능한 설명으로 제시됐다.[30]

참고 항목

참조

- ^ a b c Beggan, J. (1992). "On the social nature of nonsocial perception: The mere ownership effect". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 62 (2): 229–237. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.62.2.229.

- ^ Roeckelein, J. E. (2006). Elsevier's Dictionary of Psychological Theories. Elsevier. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-08-046064-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morewedge, Carey K.; Giblin, Colleen E. (2015). "Explanations of the endowment effect: an integrative review". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 19 (6): 339–348. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.04.004. PMID 25939336. S2CID 4619648.

- ^ a b c Weaver, R.; Frederick, S. (2012). "A Reference Price Theory of the Endowment Effect". Journal of Marketing Research. 49 (5): 696–707. doi:10.1509/jmr.09.0103. S2CID 412119.

- ^ a b c d e f Kahneman, Daniel; Knetsch, Jack L.; Thaler, Richard H. (1990). "Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (6): 1325–1348. doi:10.1086/261737. JSTOR 2937761. S2CID 154889372.

- ^ a b Zeiler, Kathryn (2007-01-01). "Exchange Asymmetries Incorrectly Interpreted as Evidence of Endowment Effect Theory and Prospect Theory?". American Economic Review. 97 (4): 1449–1466. doi:10.1257/aer.97.4.1449. S2CID 16803164.

- ^ a b Kahneman, Daniel; Knetsch, Jack L.; Thaler, Richard H. (1991). "Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 5 (1): 193–206. doi:10.1257/jep.5.1.193.

- ^ a b Zeiler, Kathryn (2005-01-01). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations". American Economic Review. 95 (3): 530–545. doi:10.1257/0002828054201387.

- ^ Carmon, Ziv; Ariely, Dan (2000). "Focusing on the Forgone: How Value Can Appear So Different to Buyers and Sellers". Journal of Consumer Research. 27 (3): 360–370. doi:10.1086/317590.

- ^ "Carrots dressed as sticks". Economist. 394 (8665): 72. 14 January 2010. 시트:

- ^ a b c Hoffman, Elizabeth; Spitzer, Matthew L. (1993). "Willingness to Pay vs. Willingness to Accept: Legal and Economic Implications". Washington University Law Quarterly. 71: 59–114. ISSN 0043-0862.

- ^ Harbaugh, William T; Krause, Kate; Vesterlund, Lise (2001). "Are adults better behaved than children? Age, experience, and the endowment effect". Economics Letters. 70 (2): 175–181. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.233.812. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(00)00359-1.

- ^ Kanngiesser, Patricia; Santos, Laurie R.; Hood, Bruce M.; Call, Josep (2011). "The limits of endowment effects in great apes (Pan paniscus, Pan troglodytes, Gorilla gorilla, Pongo pygmaeus)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 125 (4): 436–445. doi:10.1037/a0024516. PMID 21767009.

- ^ Lakshminaryanan, V.; Chen, M. K.; Santos, L. R (2008). "Endowment effect in capuchin monkeys". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1511): 3837–3844. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0149. PMC 2581778. PMID 18840573.

- ^ Coombs, C.H.; Bezembinder, T.G.; Goode, F.M. (1967). "Testing expectation theories of decision making without measuring utility or subjective probability". Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 4 (1): 72–103. doi:10.1016/0022-2496(67)90042-9. hdl:2027.42/33365.

- ^ Slovic, Paul; Lichtenstein, Sarah (1968). "Relative importance of probabilities and payoffs in risk taking". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 78 (3, Pt.2): 1–18. doi:10.1037/h0026468.

- ^ Thaler, Richard (1980). "Toward a positive theory of consumer choice". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 1 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(80)90051-7.

- ^ Gal, David; Rucker, Derek D. (2018). "The Loss of Loss Aversion: Will It Loom Larger Than Its Gain?". Journal of Consumer Psychology. 28 (3): 497–516. doi:10.1002/jcpy.1047. ISSN 1532-7663. S2CID 148956334.

- ^ a b c Morewedge, Carey K.; Shu, Lisa L.; Gilbert, Daniel T.; Wilson, Timothy D. (2009). "Bad riddance or good rubbish? Ownership and not loss aversion causes the endowment effect". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 45 (4): 947–951. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.05.014.

- ^ Gal, David (July 2006). "A Psychological Law of Inertia and the Illusion of Loss Aversion" (PDF). Judgment and Decision Making. 1: 23–32.

- ^ Gal, David (2018-10-06). "Opinion Why Is Behavioral Economics So Popular?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- ^ Kahneman, Daniel; Tversky, Amos (1979). "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk". Econometrica. 47 (2): 263. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.1910. doi:10.2307/1914185. JSTOR 1914185.

- ^ a b c Hanemann, W. Michael (1991). "Willingness To Pay and Willingness To Accept: How Much Can They Differ? Reply". American Economic Review. 81 (3): 635–647. doi:10.1257/000282803321455449. JSTOR 2006525.

- ^ a b c Shogren, Jason F.; Shin, Seung Y.; Hayes, Dermot J.; Kliebenstein, James B. (1994). "Resolving Differences in Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept". American Economic Review. 84 (1): 255–270. JSTOR 2117981.

- ^ Hu, Xingwei (2020). "A theory of dichotomous valuation with applications to variable selection". Econometric Reviews. 39 (10): 1075–1099. arXiv:1808.00131. doi:10.1080/07474938.2020.1735750. S2CID 32184598.

- ^ a b Maddux, William W.; Yang, Haiyang; Falk, Carl; Adam, Hajo; Adair, Wendy; Endo, Yumi; Carmon, Ziv; Heine, Steve J. (2010). "For Whom Is Parting With Possessions More Painful?: Cultural Differences in the Endowment Effect". Psychological Science. 21 (12): 1910–1917. doi:10.1177/0956797610388818. PMID 21097722. S2CID 16860986.

- ^ Symons, Cynthia S.; Johnson, Blair T. (1997). "The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 121 (3): 371–394. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.371. PMID 9136641.

- ^ Yechiam, Eldad.; Ashby, Nathaniel JS; Pachur, Thorsten (2017). "Who's biased? A meta-analysis of buyer-seller differences in the pricing of risky prospects". Psychological Bulletin. 143 (5): 543–563. doi:10.1037/bul0000095. PMID 28263644. S2CID 33771796.

- ^ Johnson, Eric J.; Häubl, Gerald; Keinan, Anat (2007). "Aspects of endowment: A query theory of value construction". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 33 (3): 461–474. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.33.3.461. PMID 17470000. S2CID 9699491.

- ^ a b Huck, Steffen; Kirchsteiger, Georg; Oechssler, Jörg (2005). "Learning to like what you have – explaining the endowment effect" (PDF). The Economic Journal. 115 (505): 689–702. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2005.01015.x. hdl:10419/22833. S2CID 16245289.

- ^ Apicella, Coren L.; Azevedo, Eduardo M.; Christakis, Nicholas A.; Fowler, James H. (2014). "Evolutionary Origins of the Endowment Effect: Evidence from Hunter-Gatherers" (PDF). American Economic Review. 104 (6): 1793–1805. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1793.

- ^ Klass, Greg; Zeiler, Kathryn (2013-01-01). "Against Endowment Theory: Experimental Economics and Legal Scholarship". UCLA Law Review. 61 (1): 2.

- ^ Zeiler, Kathryn (2005-01-01). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations". American Economic Review. 95 (3): 530–545. doi:10.1257/0002828054201387.

- ^ Harless, David W. (1989). "More laboratory evidence on the disparity between willingness to pay and compensation demanded". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 11 (3): 359–379. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(89)90035-8.

- ^ Knez, Peter; Smith, Vernon L.; Williams, Arlington W. (1985). "Individual Rationality, Market Rationality, and Value Estimation". American Economic Review. 75 (2): 397–402. JSTOR 1805632.

- ^ Plott, Charles (2011-01-01). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations: Reply". American Economic Review. 101 (2): 1012–1028. doi:10.1257/aer.101.2.1012.

- ^ Hovenkamp, Herbert (1991). "Legal Policy and the Endowment Effect". The Journal of Legal Studies. 20 (2): 225–247. doi:10.1086/467886. S2CID 155051169.

- ^ Fischel, William A. (1995). "The offer/ask disparity and just compensation for takings: A constitutional choice perspective". International Review of Law and Economics. 15 (2): 187–203. doi:10.1016/0144-8188(94)00005-F.

- ^ "Behavioral Indifference Curves," Australasian Journal of Economics Education. 2015, 2: 1–11

외부 링크

- Plott, Charles R; Zeiler, Kathryn (2005). "The Willingness to Pay–Willingness to Accept Gap, the "Endowment Effect," Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations". American Economic Review. 95 (3): 530–545. doi:10.1257/0002828054201387. SSRN 615861.

- Plott, Charles R; Zeiler, Kathryn (2007). "Exchange Asymmetries Incorrectly Interpreted as Evidence of Endowment Effect Theory and Prospect Theory?" (PDF). American Economic Review. 97 (4): 1449–1466. doi:10.1257/aer.97.4.1449. S2CID 16803164. SSRN 940633.

- 라이트, 조쉬(2005) 기부효과의 소멸법, 그리고 (2009) 기부효과는 무엇이 문제인가?

- 2011년 12월 28일 Per Bylund, Endowment Effect의 "미스터리"

- 관찰된 교역에 대한 거부감은 무엇으로 설명할 것인가? 종합문학평론