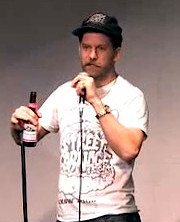

개빈 매키네스

Gavin McInnes개빈 매키네스 | |

|---|---|

2015년 개빈 매키네스 쇼(The Gavin McInnes Show 진행 | |

| 태어난 | 개빈 마일스 매키네스 1970년 7월 17일 |

| 국적. | 캐나디안의 |

| 교육 | 칼레톤 대학교 (BA) |

| 직업들 |

|

| 유명함 | |

| 움직임. | |

| 배우자. | 에밀리 젠드리삭 (m. 2005) |

| 아이들. | 3 |

| 웹사이트 | 검열.TV |

개빈 마일스 매키네스(, 1970년 7월 17일 ~ )는 캐나다의 작가, 팟캐스터, 극우 논객이자 프라우드 보이즈의 창립자입니다.[1][2]그는 'Gavin McInneson Censored'와 함께 'Get Off My Lawn'의 진행자입니다.그가 설립한 TV.[3]그는 1994년 24살의 나이에 Vice 잡지를 공동 창간했고 2001년 미국으로 이주했습니다.2016년 그는 미국 극우 단체인[4] 프라우드 보이즈를 설립했는데, 프라우드 보이즈는 그가 그룹을 떠난 후 캐나다와[5][6] 뉴질랜드에서 테러 단체로 지정되었습니다.[7]매키네스는 정적들에 대한 폭력을 조장하는 것으로 묘사되어 왔지만,[8][9][10][11][12] 정당방위 차원에서 정치적 폭력을 지지해왔을 뿐이며, "재정적 보수주의자이자 자유지상주의자"라고 밝히며 극우파나 파시즘 지지자가 아니라고 주장했습니다.[1]

영국 하트퍼드셔에서 스코틀랜드 부모에게서 태어난 맥키네스는 어린 시절 캐나다로 이민을 갔습니다.그는 몬트리올로 이주하기 전에 오타와에 있는 칼레톤 대학을 졸업하고 수로시 앨비, 셰인 스미스와 함께 바이스를 공동 설립했습니다.[13]그는 2001년에 부 미디어와 함께 뉴욕으로 이주했습니다.[14][15][16]바이스 재직 시절, 맥키네스는 뉴욕 힙스터 하위문화의 선두주자로 불렸습니다.[17]그는 캐나다와 영국 시민권을 모두 가지고 있으며 뉴욕 라치몬트에 살고 있습니다.[13]

2018년, McInnes는 Blaze Media에서 해고되었고,[18] 폭력적인 극단주의 단체와 혐오 발언을 조장하는 것과 관련된 사용 조건을 위반했다는 이유로 트위터, 페이스북, 인스타그램에서 금지되었습니다.[19][20]2020년 6월, 맥키네스의 계정은 유튜브의 혐오 발언에 관한 정책을 위반하여 유튜브에서 정지되었으며, "다른 사람이나 집단에 대한 폭력을 미화하고 선동하는" 내용을 게시했습니다.[21]

젊은 시절

개빈[23] 마일스[22] 매키네스는 1970년 7월 17일 영국 하트퍼드셔주 히친에서 스코틀랜드 부모 제임스 매키네스([24]James McInes)와 은퇴한 비즈니스 교사 로레인 매키네스(Loraine McInes)의 아들로 태어났습니다.[25]그의 가족은 매키네스가 네 살 때 캐나다로 이주하여 온타리오주 오타와에 정착했습니다.[citation needed][26]그는 오타와의 3월 초 중등학교에 다녔습니다.[27]10대 때, 맥키네스는 아날 치누크라고 불리는 오타와 펑크 밴드에서 연주했습니다.[28]그는 칼레톤 대학을 졸업했습니다.[25]

직업

바이스 미디어 (1994-2007)

McInnes는 1994년 Shane Smith, Suroush Alvi와 함께 Vice를 공동 설립했습니다.[15]이 잡지는 정부의 자금 지원을 받아 몬트리올의 소리로 창간되었습니다.창업자들의 의도는 일과 사회봉사를 제공하는 것이었습니다.[29]편집자들이 나중에 원래 출판사인 알릭스 로랑과의 약속을 해결하려고 했을 때, 그들은 그를 매수했고 1996년에 이름을 바이스로 바꿨습니다.[30]캐나다의 소프트웨어 백만장자인 Richard Szalwinski는 그 잡지를 인수했고 1990년대 후반에 뉴욕시로 그 사업을 이전했습니다.[31][32]

맥키네스의 재임 기간 동안 그는 WNBC에[33] 의해 힙스터덤의 "대부"로 묘사되었고, 애드버스터즈에 의해 "힙스터덤의 주요 건축가 중 한 명"으로 묘사되었습니다.[34]그는 때때로 "행복에 대한 VICE 가이드"[35]와 " 병아리를 줍는 VICE 가이드"를 포함한 바이스에 기고했으며 [36]두 권의 바이스 책을 공동 집필했습니다.섹스와 마약, 로큰롤에 대한 [37]바이스 가이드, 그리고 바이스 도스와 돈트: 10년간의 바이스 매거진의 스트리트 패션 비평.[38]

2002년 뉴욕 프레스지와의 인터뷰에서, 맥키네스는 대부분의 윌리엄스버그 힙스터들이 백인이어서 기쁘다고 말했습니다.[39][40]맥키네스는 나중에 가우커에게 보낸 편지에서 인터뷰가 "타임즈와 같은 베이비 붐 미디어"를 조롱하기 위한 장난으로 이루어졌다고 썼습니다.[41]흑인 독자의 편지쓰기 캠페인의 초점이 된 후, 부통령은 맥키네스의 발언에 대해 사과했습니다.[40]맥키네스는 2003년 뉴욕 타임즈의 바이스지에 관한 기사에 실렸습니다; 타임즈는 맥키네스의 정치적 견해를 "백인 우월주의에 가깝다"고 묘사했습니다.[40]

2006년, 그는 중국에서 배우이자 코미디언인 데이비드 크로스와 함께 여행을 위한 부 가이드에 출연했습니다.[42]그는 2008년에 "창의적 차이"로 인해 바이스를 떠났습니다.[14]2013년 뉴요커지와의 인터뷰에서 McInnes는 Vice와의 결별은 Vice의 콘텐츠에 대한 기업 광고의 영향력 증가에 관한 것이라며 "마케팅과 편집이 적이었던 것이 사업 계획이었다"고 말했습니다.[43]

After Vice (2008-2018)

2008년 바이스를 떠난 후, 맥키네스는 극우적인 정치관으로 점점 더 유명해졌습니다.[1]

2008년, McInnes는 StreetCarnage.com 이라는 웹사이트를 만들었습니다.그는 또한 자신이 크리에이티브 디렉터로 일했던 루스터라고 불리는 광고 대행사를 공동 설립했습니다.[44]

맥키네스는 캐나다 리얼리티 TV 쇼 케니 대 시즌 3에 출연했습니다. '누가 더 멋있을까' 편의 심사위원으로서 스패니.2010년, 매키네스는 어덜트 스윔에게 접근하여 짧은 기간 동안의 아쿠아 틴 헝거 포스 스핀오프 소울 퀘스트 오버드라이브에서 스코틀랜드의 의인화된 축구공 믹 역을 맡아줄 것을 요청 받았습니다.[45]2010년 파일럿 콘테스트에서 샤이엔 시나몬과 슈가 타운 캔디 퍼지의 환상적인 유니콘에게 패한 후, 소울 퀘스트 오버드라이브의 6개 에피소드가 주문되었고, 2011년 5월 25일 어덜트 스윔의 4AM DVR 시어터 블록에서 4개의 방송이 방영되었다가 빠르게 취소되었습니다.맥키네스는 다른 출연진(크리스텐 샬, 데이비드 크로스, H. 존 벤자민)들이 그처럼 "웃기지" 않았다고 농담 삼아 그 프로그램의 취소를 비난했습니다.[46]

McInnes는 2011년경부터 Taki's Magazine에 남부 빈곤법 센터(SPC)가 설명한 것처럼 인종 및 반 동성애 비방을 일상적으로 사용하는 칼럼을 썼습니다.[47]

2012년에, McInnes는 How to Piss in Public 이라는 책을 썼습니다.[48]2013년에는 가끔 스탠드업 코미디언으로 투어를 진행하는 다큐멘터리 '여행하는 창녀의 형제단'을 연출했습니다.[49]그 영화를 위해 그는 심각한 교통사고를 위장했습니다.또한 그 해, 맥키네스는 선댄스 넥스트 위크엔드에서 초연된 독립 영화 <하우 투 비 어 맨>에 출연했습니다.[50]그는 또한 소울 퀘스트 오버드라이브 (2010), 크리에이티브 컨트롤 (2015), 원 모어 타임 (2015)을 포함한 다른 영화들에서도 조연을 맡았습니다.

2014년 8월, 맥키네스는 "트랜스포비아는 완벽하게 자연스럽다"[51]라는 제목의 트랜스포비아에 대한 에세이를 온라인에 게재한 후, 루스터의 최고 크리에이티브 책임자로서 무기한 휴학을 요청받았습니다.이에 대해 루스터는 성명서를 내고 "우리는 그의 행동에 매우 실망했으며 우리가 가장 적절한 행동 방침을 결정하는 동안 그에게 휴가를 줄 것을 요청했습니다."[52]라고 말했습니다.

2015년 6월, 방송인 앤서니 쿠미아(Anthony Cumia)는 매키네스가 자신의 네트워크에서 쇼를 진행할 것이라고 발표하여 3월에 시작했던 프리 스피치 팟캐스트를 은퇴시켰습니다.개빈 매키네스 쇼는 6월 15일 컴파운드 미디어에서 초연되었습니다.매키네스는 캐나다의 극우 포털인 리벨 미디어의[53] 전 기고자이자 음모론자 미디어 플랫폼인 인포워즈의 알렉스 존스 쇼와 폭스 뉴스의 레드 아이, 그렉 구트펠드 쇼, 숀 해니티 쇼의 단골입니다.

2016년, 그는 SPLC에 의해 "일반 혐오" 단체로 분류된 네오 파시스트,[54][55][56] 남성 인권 및 남성 전용 단체인 프라우드 보이즈를 설립했습니다.[57]그는 이 단체가 "극단주의 단체가 아니며 백인 민족주의자들과 관계가 없다"고 주장하며 이 분류를 거부했습니다.[2]

맥키네스는 2017년 8월 리벨뉴스를 떠나 "멀티미디어 하워드 스턴-만남-터커 칼슨"이 될 것이라고 선언했습니다.[58]그는 나중에 Conservative Review에 의해 시작된 온라인 텔레비전 네트워크인 CRTV에 가입했습니다.2017년 9월 22일에 방송된 그의 새 쇼 "Get Off My Lawn"의 첫 번째 에피소드.[59][60]

2018년 사건

2018년 8월 10일, 맥키네스의 트위터 계정과 프라우드 보이즈의 계정은 폭력적인 극단주의 단체에 대한 그들의 규정 때문에 트위터에 의해 영구 정지되었습니다.이번 활동 중단은 2018년 8월 버지니아주 샬러츠빌에서 열린 유니트 더 라이트 집회와 프라우드 보이즈가 참여한 소규모 유니트 더 라이트 2 워싱턴 시위 1주년을 앞두고 있었습니다.[61][62][63]

2018년 10월 12일, 야마구치 오토야가 1960년 사회주의 정치인 아사누마 이네지로를 암살한 사건을 재현하는 행사에 참석했습니다.행사가 끝난 후, 프라우드 보이즈의 대표단이 한 좌익 시위자가 그들에게 플라스틱 병을 던진 후,[64] 행사장 밖에서 한 시위자를 구타하는 장면이 테이프에 잡혔습니다.[65]

2018년 11월 21일, FBI가 프라우드 보이즈를 백인 민족주의자들과 연관된 극단주의 단체로 분류했다는 소식이 전해진 직후, 맥키네스는 변호사들이 그에게 그만두는 것이 10월에 사건으로 기소된 9명의 멤버들에게 도움이 될 수도 있다고 조언했다고 말했으며, 그는 "이것은 100% 합법적인 행동이며, 100% 아부입니다.ut enviling sentence", 그리고 그것은 인용 표시로 "stepping다운 제스처"라고 말했습니다.2주 후, FBI 오리건 사무실의 특수 요원은 그룹 전체를 "극단주의자"로 분류하는 것은 그들의 의도가 아니라고 말했으며,[67] 단지 특정 조직원들로부터 발생할 수 있는 위협을 특징짓는 것일 뿐입니다.[68]

그 달 말, 맥키네스는 밀로 얀노풀로스와 토미 로빈슨(스티븐 야슬리-레논의 가명)과 함께 호주로 연설 투어를 떠날 계획이었지만, 호주 이민 당국으로부터 "그는 성격이 좋지 않은 것으로 판단되었다"는 통보를 받았고 입국 비자가 거부될 것입니다.맥키네스에게 비자를 발급하는 것은 81,000명의 서명을 모은 온라인 캠페인 "#BanGavin"에 의해 반대되었습니다.[69][70]

2018년 12월 3일, 맥키네스가 진행했던 《Conservative Review Television》(CRTV)은 블레이즈와 합병했습니다.글렌 벡의 '더 블레이즈'의 TV 자회사인 TV는 블레이즈 미디어가 될 것입니다.McInnes는 새 회사를 위해 그의 프로그램을 진행할 것으로 예상되었는데, 공동 사장은 McInnes를 "블레이즈 미디어 플랫폼의 다양한 목소리와 관점 중 하나인 코미디언이자 도발가"라고 불렀습니다.1주일도 지나지 않아 12월 8일, 맥키네스는 블레이즈 미디어와 더 이상 관련이 없다고 발표되었으며, 그 이유에 대한 자세한 내용은 언급되지 않았습니다.[71][72]

이틀 후인 12월 10일, 아마존, 페이팔, 트위터, 페이스북으로부터 이전에 금지되었던 맥키네스는 "저작권 침해에 대한 복수의 제3자 주장"으로 유튜브로부터 금지되었습니다.[73]매키네스는 자신의 해고와 금지에 대해 언급해 달라는 질문에 "거짓말과 선전"에 희생당했으며 "나를 제거하려는 공동의 노력이 있었다"고 말했습니다.맥키네스는 허핑턴포스트에 보낸 이메일에서 "아주 강력한 누군가가 오래 전에 제가 목소리를 내지 말아야겠다고 결정했습니다.난 마침내 플랫폼을 벗어났고 나를 방어할 수가 없어요.우리는 더 이상 자유로운 나라에 살고 있지 않습니다."[74]맥키네스는 ABC 뉴스 프로그램인 나이트라인의 인터뷰에서 이번 사태에 대한 개인적인 책임을 지적하며 이렇게 말했습니다."나는 이 일에 죄책감을 느끼지 않습니다.거기에 책임이 있습니다.맥키네스는 "그 배는 항해했다"며 사과하거나 자신의 과거 진술을 철회하지는 않았지만,[75][76] "폭력이 모든 것을 해결한다"고 말하지 말았어야 했습니다.

라치몬트 잔디 간판 논란

2018년 10월 프라우드 보이즈 싸움에 대한 대응으로, 맥키네스가 살고 있는 웨스트체스터 교외 지역인 라치몬트의 주민들은 커뮤니티 주변의 잔디 표지판에 그 슬로건을 표시하는 것과 관련된 "Hate Has No Home Here" 캠페인을 시작했습니다.한 주민은 "우리는 공동체로서 함께 서 있으며, 폭력과 증오는 여기서 용납되지 않는다"고 말했습니다.이 징후가 나타나기 시작한 지 며칠 후, 맥키네스의 아내는 이웃들에게 언론이 맥키네스를 잘못 보도했다는 이메일을 보냈습니다.[77]

인근 마마로넥에 사는 활동가이자 작가인 에이미 시스킨드는 페이스북에 반 증오 집회를 계획하고 있다고 글을 올렸습니다.한 지역 신문이 이에 대한 기사를 보도한 후, 맥키네스와 그의 가족은 초대도, 예고도 없이 시스킨드의 문 앞에 나타났고, 그녀는 경찰에 신고했습니다.[77]

12월 말, 잔디밭 표지판 캠페인이 아직도 진행 중인 가운데, 맥키네스는 이웃집에 내려놓은 편지를 썼습니다.그 책에서 그는 그들에게 그들의 팻말을 내려달라고 요청했고, 자신을 "친 동성애자, 친이스라엘, 맹렬하게 인종차별적인 자유지상주의자"라고 묘사하면서, 잠시 후 "반유대주의자가 되고 있다"는 등의 과거 발언과 달리, "내 세계관의 어떤 표현에도 "혐오, 인종차별, 동성애 혐오, 반유대주의, 불관용"은 없었다고 말했습니다.이스라엘로의 여행, 또는 트랜스젠더를 "젠더 흑인"으로 지칭하는 것.맥키네스는 프라우드 보이즈가 "몇 년 전 농담으로 시작한 술 클럽"이라고 말했습니다.2019년 1월 4일 팟캐스트에서 매키네스는 이웃들을 "엉덩이들"이라고 부르며 그들의 행동을 "카운티"라고 표현하며 "네 잔디에 그 표지판이 있다면 넌 바보야"[77]라고 말했습니다.

한 라치몬트 주민은 그에 대해 "개빈이 뭐라고 하든 상관없어요. 조사는 다 했는데...그는 폭력을 선동합니다.그는 분열적이고 인종차별적인 언어를 내뱉습니다.그리고 그는 추종자들을 부인한다고 말하려 할 수도 있지만, 문제의 일부입니다.그래서 제가 그의 편지를 읽었을 때, 저는, 네, 맞아요, 이건 말도 안 되는 것 같아요."[78]

편지가 발송된 지 며칠 후, Huff Post는 일부 이웃들이 맥키네스의 아내이자 진보 민주당원이라고 밝힌 에밀리가 그들을 괴롭히고 협박했다는 증거를 보고했다고 보도했습니다.그녀의 위협이 너무 심해서 몇몇 이웃들이 경찰에 알렸습니다.[77]

SPLC에 대한 소송

맥키네스는 2018년 11월 프라우드 보이즈와 공개적으로 관계를 끊고 회장직에서 물러났지만 2019년 2월 남부빈곤법률센터를 상대로 프라우드 보이즈를 "일반혐오" 단체로 지정한 것에 대해 소송을 제기했습니다.[2][66]명예훼손 소송은 앨라배마주 연방법원에 제기됐습니다.매키네스는 제출한 서류에서 혐오 단체 지정은 허위이며 모금 우려에 따른 동기 부여라며 이로 인해 경력에 타격을 입었다고 주장했습니다.그는 SPLC가 트위터, 페이팔, 메일침프, 아이튠즈 등에 의해 자신이나 자랑스러운 소년들의 평판이 나빠지는 데 기여했다고 주장했습니다.[79][80]

SPLC는 웹사이트를 통해 "맥인네스는 백인 민족주의, 특히 '알트 우파'라는 용어를 거부하는 이중적인 수사 게임을 하고 있으며, 이는 백인 민족주의의 일부 핵심 교리를 지지하는 것"이라며, 이 단체의 "일반 회원들과 지도자들은 백인 민족주의 밈을 정기적으로 발표하고 알려진 극단주의자들과 연대를 유지하고 있다"고 밝혔습니다.그들은 반이슬람적이고 여성혐오적인 수사로 알려져 있습니다.'프라우드 보이즈'는 샬러츠빌에서 열린 '우아일체' 집회와 같은 극단주의자 모임에 다른 혐오 단체들과 함께 등장했습니다."[57][80]이 소송에 대해 SPLC의 회장인 Richard Cohen은 "Gavin McInnes는 무슬림, 여성 및 트랜스젠더 공동체에 대해 선동적인 진술을 한 이력이 있습니다.그가 SPLC에 화가 났다는 사실은 우리가 증오와 극단주의를 폭로하는 일을 하고 있다는 것을 말해줍니다."[80]

검열.TV 및 기타 벤처 (2019년~현재)

검열.TV와 내 잔디밭에서 내려요 출시

2019년, McInnes는 "Censored"를 출시했습니다.온라인 동영상 플랫폼인 TV그 플랫폼의 이름은 원래 FreeSpeech입니다.TV, 그러나 저작권 목적으로 현재의 제목으로 변경되었습니다.이 플랫폼에는 맥키네스의 주요 쇼인 GOML(Get Off My Lawn)이 있습니다. GOML은 목요일을 제외하고 평일에 방송되는 사전 녹화된 일일 쇼로, 이 쇼는 Get Off My Lawn Live라는 대체 제목으로 생방송됩니다.[citation needed]

2021년 5월, 마일로 얀노풀로스는 텔레그램에 검열을 했다고 썼습니다.TV는 "모든 직원을 해고"하고 있으며 플랫폼에서 Yiannopoulous의 쇼를 지속적으로 제작하기에 충분한 자금이 부족했습니다.[81]맥키네스는 나중에 자신의 플랫폼에 몇 개의 새로운 쇼의 등장을 알리면서 이러한 주장을 일축했습니다.[82][third-party source needed]

2022년 8월 27일, 매키네스는 'Censored' 생방송 도중 자신을 체포한 것처럼 위장했습니다.TV. 녹화에서 맥키네스는 카메라 너머로 시선을 떼는 듯 보였고, "우리가 쇼를 촬영하는데, 다음에 이것을 할 수 있을까요?"라고 말하며 "당신을 들여보내지 않았습니다"라고 덧붙였습니다. 맥키네스는 그 후 촬영장을 떠났습니다.매키네스가 체포됐다는 추측이 우세했지만, 전 매키네스 동맹인 오웬 벤자민이 두 사람 사이에 문자 메시지를 보내며 매키네스를 따돌렸습니다."장난.말하지 말아요." 맥키네스가 벤자민에게 편지를 썼습니다.벤저민은 "장난이라고 폭로할 건가요?"라고 대답했습니다.왜냐하면 친구들이 블로그에 글을 쓰고 있기 때문입니다."라고 답했습니다. 맥키네스는 FBI가 그의 스튜디오를 급습했다고 "말한 적이 없다"고 덧붙였습니다.벤자민에 의해 쫓겨난 후, 맥키네스는 2022년 9월 6일에 대중에게 돌아왔습니다.[83][84]

2022년 12월, 매키네스는 카니예 웨스트와 백인 민족주의자 닉 푸엔테스를 인터뷰했습니다.인터뷰에서 매키네스는 서방세계를 자신의 반유대주의로부터 구하려 한다고 주장했고, 매키네스는 유대인이 아니라 "모든 인종의 자유주의 엘리트"라고 비난했고, 반면 서방세계는 유대인들이 아돌프 히틀러를 용서해야 한다고 말하며 반유대주의가 "대선 캠페인을 위해 멋진 것"이 될 것이라고 예측했습니다.[85][86][87]

프라우드 보이즈의 뉴욕 재판

맥키네스는 2018년 10월 메트로폴리탄 공화 클럽 회의 후 발생한 폭력에 가담했다는 이유로 2019년 8월 프라우드 보이즈 회원들에 대한 재판에서 피고인이 아니었지만, 검찰은 피고인들에 대한 신문에서 그의 이름과 말, 견해를 반복적으로 언급했고,피고인들과 다른 프라우드 보이즈가 증언한 후에 심문의 문을 열었습니다.마지막 변론에서 한 검사는 "개빈 매키네스는 악의 없는 풍자가가 아닙니다.그는 증오에 찬 사람입니다"라고 말하는 반면, 변호인은 맥키네스가 "악마되고 있다"고 말했습니다.[88]

뷰

맥키네스는 스스로를 "재정적 보수주의자이자 자유지상주의자"[1]이며, 그가 선호하는 용어인 뉴라이트의 일부라고 설명합니다.[89][non-primary source needed]뉴욕타임스는 맥키네스를 극우 도발자로 묘사했습니다.[90]그는 스스로를 "서양 쇼비니즘자"라고 일컬었고, 이 대의에 충성을 맹세하는 "프라우드 보이즈"라는 남성 단체를 시작했습니다.[91]

2018년 11월, 워싱턴 주 클라크 카운티의 내부 메모에 근거하여 FBI 브리핑에 근거하여, FBI는 프라우드 보이즈를 "백인 민족주의와 관련이 있는 극단주의 집단"으로 분류했다고 보고했습니다.[92]2주 후, FBI 오리건 사무실의 특수 요원은 FBI가 전체 그룹에 대해 그런 지정을 한 것이 보안관 사무실 측의 오해 때문이라고 부인했습니다.[67]SAIC의 렌 캐넌은 그들의 의도는 단지 그룹 전체를 분류하는 것이 아니라 그룹의 특정 멤버들로부터 발생할 수 있는 위협을 특징짓는 것이라고 말했습니다.[68]남부빈곤법률센터는 이들을 '일반적인 혐오집단'으로 분류하고 있습니다.[57]맥키네스는 자신의 단체가 백인 민족주의 단체가 아니라고 말했습니다.[92]

2003년, McInnes는 "저는 백인인 것을 좋아하고 그것은 매우 자랑스러워 해야 할 것이라고 생각합니다.저는 우리의 문화가 희석되는 것을 원하지 않습니다.우리는 이제 국경을 폐쇄하고 모든 사람들이 서구적이고 백인적이며 영어를 사용하는 삶의 방식에 동화되도록 해야 합니다."[93]

폭력.

2017년 2월 뉴욕대에서 열린 프라우드 보이즈와 안티파 시위자들 간의 충돌 후, 맥키네스는 "폭력은 기분이 좋지 않고, 정당화된 폭력은 기분이 좋지 않으며, 싸움은 모든 것을 해결합니다. ...난 폭력을 원해요.주먹으로 얼굴을 때리고 싶습니다."[76]그는 오로지 자기 방어를 위해 행동하는 것을 옹호해 왔다고 말합니다.[94][95]

인종과 민족

매키네스는 인종차별과[96] 백인 우월주의 수사를 조장했다는 비난을 받아왔습니다.[90]그는 수전 라이스와 제이다 핀켓 스미스에 대해 인종차별적 비방을 [97][98]일삼았고, 팔레스타인과 아시아인에 대해서도 더욱 광범위하게 비난했습니다.[99][100]2004년 9월, 그는 한 파티에서 시카고 리더의 기자에게 "그녀가 말하기 시작할 때까지 [아시아의 젊은 여성]을 엿먹고 싶었다"고 말했습니다.기자인 리즈 암스트롱은 "그는 계속해서 아시아인들의 눈은 표정 면에서 그렇게 잘 작동하지 않기 때문에 입으로 감정을 자극할 수밖에 없다고 생각했습니다."[101]라고 썼습니다.

맥키네스는 "흑인들이 서로에게 밀어붙이는 대량 순응"이 있다고 말했습니다.[102]그는 또한 2016년 '흑인의 목숨도 소중하다' 운동을 비판하는 책 '흑인의 거짓말도 소중하다'의 기고자로 이름을 올렸습니다.그는 흑인인 코리 부커 뉴저지주 상원의원이 "삼보와 비슷한 면이 있다"고 말했습니다.[103]

종교

유대교

2017년 3월, 매키네스를 포함한 리벨 미디어 진행자 그룹은 일주일 동안 이스라엘을 관광했습니다.여행 중에, 맥키네스는 홀로코스트 부인자들을 옹호하고, 베르사유 조약의 책임을 유대인들에게 돌리며, "반유대주의자가 되고 있다"고 말하는 비반란 동영상을 만들었습니다.[104][105][106][107][108]타임스오브이스라엘은 이 동영상에서 그가 "술에 취한 것 같다"고 말했습니다.[104][106]이스라엘 국영 뉴스는 이를 "거짓말"이며 "의도적으로 공격적"이라고 표현했습니다.[108]그는 나중에 자신의 발언이 맥락에서 벗어났다고 말했습니다.[109]맥키네스는 또한 "유대인에 대해 내가 싫어하는 10가지"라는 제목의 리벨의 코미디 비디오를 제작했으며, 후에 "이스라엘에 대해 내가 싫어하는 10가지"라는 제목이 붙여졌습니다.[107][105]백인 우월주의자들에 의해 그의 진술이 홍보된 후(리벨 미디어 투어의 다른 비디오들과 대조적으로), McInnes는 공개적으로 그들의 지지를 거절했습니다.[108]매키네스가 미국으로 돌아오자, 리벨 미디어는 매키네스의 영상을 제작했는데, 그는 "나는 수많은 나치 친구들을 가지고 있습니다.데이비드 듀크와 모든 나치들은 내가 흔들린다고 생각해요기분 상하게 하고 싶지는 않지만, 나치스, 당신 마음에 들지는 않아요.저는 유대인을 좋아합니다."[105][106] 리벨 미디어의 소유주인 에즈라 레반트는 유대계 캐나다인 맥키네스를 옹호했습니다.[108]2022년 12월에 있었던 '검열' 인터뷰에서.카니예 웨스트와 백인 민족주의자 닉 푸엔테스가 함께한 TV에서 그는 웨스트를 반유대주의로부터 구하려 한다고 주장하며 "내가 만나는 모든 사람은 깨끗한 슬레이트로 시작한다"[110][111][86]고 말했습니다.

이슬람교

맥키네스는 반이슬람주의자입니다.[97][112]그는 "이슬람교도들은 멍청하다"고 말했습니다.그들이 정말로 존경하는 유일한 것은 폭력과 강인함입니다."[113]그는 또한 이슬람과 파시즘을 동일시하며, "나치는 물건이 아닙니다.이슬람교는 중요한 것입니다."[114]2018년 4월, 맥키네스는 무슬림의 상당 부분을 정신 질환과 근친상간으로 분류하고, "무슬림들은 인육에 문제가 있습니다.그들은 첫째 사촌들과 결혼하는 경향이 있습니다.그리고 그것은 [미국에서] 주요한 문제입니다. 왜냐하면 여러분이 모든 이슬람교도들은 아니지만 불균형한 수만큼의 정신적인 손상을 입었을 때, 그리고 코란[sic]이라는 증오 책을 가지고 있을 때...결국 당신은 집단 살인에 대한 완벽한 요리법으로 끝납니다."[57][115]

성별

맥키네스는 자신을 "아치 벙커 성차별주의자"라고 표현했으며,[90] "95%의 여성들이 집에서 더 행복할 것"이라고 말했습니다.[76]그는 여경을 주제로 "[여성이] 가정에 좋은 것은 이해하지만, 왜 이렇게 많은 여경이 있는지 이해할 수 없습니다.그들은 힘이 세지 않아요, 초지방 경찰 같아요.말이 안 돼요."[116]

2003년 뉴욕타임즈의 바네사 그리고리아디스는 맥인즈의 말을 인용하여 "아니오는 곧 아니오"는 청교도주의라고 말했습니다.스타이넘 시대의 페미니즘이 여성들에게 많은 부당함을 주었다고 생각하지만 최악의 것 중 하나는 여성들이 지배받기를 원하지 않는다는 이 모든 인디노르트들을 설득시킨 것입니다."[93] 매키네스는 시카고 선타임스,[117] 인디펜던트 저널 리뷰,[118] 살롱,[119] 이제벨,[120] 할리우드 리포터,[121] 슬레이트 등 다양한 매체로부터 성차별 혐의를 받고 있습니다.[122]2013년 10월, 맥키네스는 패널 인터뷰에서 "여성들이 남성인 척하는 것을 그만두면 사람들이 더 행복해질 것"이라며 페미니즘이 "여성들을 덜 행복하게 만들었다"고 말했습니다.[123]그는 "우리는 출산과 가정적인 것을 너무 하찮게 여겨서 여자들은 남자 행세를 할 수밖에 없습니다.그들은 이런 강인함을 가장하고 있고, 비참합니다."[124]마이애미 대학교 법학부 교수 메리 앤 프랭크스와 열띤 논쟁이 이어졌습니다.[125]

백인 집단학살

매키네스는 낙태와[126] 이민을 하는 백인 여성들이 "서구의 백인 집단학살로 이어지고 있다"며 백인 집단학살 음모론을 옹호해 왔습니다.[127]2018년 남아프리카 공화국의 농장 공격과 토지 개혁 제안과 관련하여, 그는 남아프리카 공화국 흑인들이 "그들의 땅을 되찾기 위해 노력하는 것이 아니라, 그들은 그 땅을 가진 적이 없다"고 말했고, 대신 남아프리카 공화국 백인들에 대한 "인종 청소" 노력이 있었다고 말했습니다.[128]

필모그래피

영화

- 남자가 되는 법 (2013) – 마크 매카시 역

- 크리에이티브 컨트롤 (2015) – 스콧 역

- 원 모어 타임 (2015) – 음반 프로듀서 역

텔레비전

- 케니 대 스패니: "Who is Cooler" 에피소드 (2006) – 그 자신 (게스트 심사위원)

- 소울 퀘스트 오버드라이브 (2010, 2011) – 믹 역 (목소리)

- 부 가이드 투 트래블(2006) – 본인(호스트)

개인생활

McInnes는 그린카드로 미국에 거주하고 있습니다.[13]2005년, 그는 자신을 진보적 민주주의자라고 묘사한 북미 원주민 운동가 크리스틴 화이트라빗 젠드리삭의[25][129] 딸인 맨해튼에 기반을 둔 홍보 담당자이자 컨설턴트인 에밀리 젠드리삭과 결혼했습니다.[76]매키네스는 아내의 민족성과 아이들이 함께 있는 것에 대해 "나는 인도인들에 대한 나의 견해를 매우 분명히 밝혔습니다.난 그들이 좋다.사실 너무 좋아해서 세 개를 만들었어요."[130]그들은 뉴욕 라치몬트에 삽니다.[131]

참고문헌

- ^ a b c d Feuer, Alan (16 October 2018). "Proud Boys Founder: How He Went From Brooklyn Hipster to Far-Right Provocateur". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Jason (21 November 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes quits 'extremist' far-right group". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "About CENSORED.TV". Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Founder of Proud Boys hate group shows up at hospital rally to support Trump". The Independent. 4 October 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Aiello, Rachel (3 February 2021). "Canada adds Proud Boys to terror list". CTVNews. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Government of Canada lists 13 new groups as terrorist entities and completes review of seven others". Government of Canada. 3 February 2021. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Kriner, Matthew; Lewis, Jon (July–August 2021). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). "Pride & Prejudice: The Violent Evolution of the Proud Boys" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center. 14 (6): 26–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Noyes, Jenny (1 December 2018). "Far-right figure Gavin McInnes denied visa ahead of planned speaking tour". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (5 February 2019). "Gavin McInnes is latest far-right figure to sue anti-hate watchdog". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Why are the Proud Boys so violent? Ask Gavin McInnes". Hatewatch. Southern Poverty Law Center. 18 October 2018. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

McInnes has a well-documented and long-running record of blatantly promoting violence and making threats. "We will kill you. That's the Proud Boys in a nutshell. We will kill you," he said on his "Compound Media" show in mid-2016. His followers often repeat his calls for violence and seemed especially emboldened this past summer as they participated in a number of large-scale "free speech" rallies across the country.

- ^ Coaston, Jane (15 October 2018). "The Proud Boys, the bizarre far-right street fighters behind violence in New York, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

It's that violence that the Proud Boys have become best known for, with the group even boasting of a "tactical defensive arm" known as the Fraternal Order of Alt-Knights (or "FOAK") reportedly with McInnes's backing. McInnes made a video praising the use of violence this June, saying, "What's the matter with fighting? Fighting solves everything. The war on fighting is the same as the war on masculinity."

- ^ Aquilina, Kimberly M. (9 February 2017). "Gavin McInnes explains what a Proud Boy is and why porn and wanking are bad". www.metro.us. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

'People say if someone's fighting, go get a teacher. No, if someone's f-ing up your sister, put them in the hospital.'

- ^ a b c Houpt, Sam (2017). "Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes's path to the far-right frontier". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ a b Alex Pareene (23 January 2008). "Co-Founder Gavin McInnes Finally Leaves 'Vice'". Gawker. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ a b "The 'Vice' Boys Are All Grown Up And Working For Viacom". Gawker. 19 November 2007. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012.

- ^ Benson, Richard (28 October 2017). "How Terry Richardson created porn 'chic' and moulded the look of an era". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: the godfather of vice". www.macleans.ca. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (10 December 2018). "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Fired From Blaze Media, YouTube Account Disabled". Huffpost. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (10 August 2018). "Twitter Shuts Down Accounts of Vice Co-Founder Gavin McInnes, Proud Boys Ahead of 'Unite the Right' Rally". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

Twitter suspended the accounts of Vice Magazine co-founder Gavin McInnes and his far-right Proud Boys group Friday afternoon...The accounts were shut down for violating the company's policies prohibiting violent extremist groups, Twitter said in a statement to BuzzFeed News

- ^ Sacks, Brianna (30 October 2018). "Facebook Has Banned The Proud Boys And Gavin McInnes From Its Platforms". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

The company confirmed Tuesday that it has begun shutting down a variety of accounts associated with the Proud Boys and its founder, Gavin McInnes, on both Facebook and Instagram, citing its 'policies against hate organizations and figures.'

- ^ Rozsa, Matthew (2020년 7월 24일) "유튜브, 프라우드 보이즈 설립자 Gavin McInnes 계정 정지" 2020년 6월 25일 웨이백 머신 살롱에서 보관

- ^ "Vows: Emily Jendriasak and Gavin McInnes". Gawker. 28 September 2005. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (2013). "Zapped by Spaces Gun into a Shit Hole on Acid (1985)". The Death of Cool: From Teenage Rebellion to the Hangover of Adulthood. Simon and Schuster. p. 6. ISBN 9781451614183. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

In 1975, five years after a breathtakingly gorgeous baby Me was born

- ^ Solutions, Powder Blue Internet Business (3 February 2017). "11 arrested at protests over offensive comedian : News 2017 : Chortle : The UK Comedy Guide". Chortle. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

{{cite web}}:first1=일반 이름(도움말)이 있습니다. - ^ a b c "Emily Jendriasak and Gavin McInnes". Gawker.com. Gawker. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Gavin McInnes (2012). The Death of Cool. Simon and Schuster. p. 1. ISBN 9781451614183. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (2013). The Death of Cool: From Teenage Rebellion to the Hangover of Adulthood. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451614183. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes on Montreal junkies, Fox News and the death of cool". Nightlife.Ca. 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ [Wilkinson, Carl (2008년 3월 30일)."부팀".가디언지.런던.2009년 1월 30일 검색.]

- ^ Jeff Bercovici (3 January 2012). "Vice's Shane Smith on What's Wrong With Canada, Facebook and Occupy Wall Street". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Wiedeman, Reeves (10 June 2018). "Vice Media Was Built on a Bluff. What Happens When It Gets Called?". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Vice Media History". www.zippia.com. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Mawuse Ziegbe (21 April 2010). "Vice" Founder Gavin McInnes on Split From Glossy: "It's Like a Divorce". NBC New York. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Douglas Haddow (29 July 2008). "Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization". Adbusters. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "The VICE Guide To Happiness". Vice. December 2003. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "The VICE Guide to Picking Up Chicks". Vice. December 2005. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "The Vice Guide to Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll". Goodreads. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Vice Dos and Don'ts". Goodreads. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Vice Rising: Corporate Media Woos Magazine World's Punks". New York Press. 8 October 2002. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Edge of Hip: Vice, the Brand". The New York Times. 28 September 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Gavin McInnes. "Letter to Gawker from Gavin McInnes". Gawker.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Gavin McInnes (2 August 2007). "David Cross in China (part 1)". Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Widdicombe, Lizzie (8 April 2013). "The Bad-Boy Brand". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ Braiker, Brian (20 June 2011). "Creating Ads For People Who Hate Ads". Adweek. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Adult Swim – Soul Quest Overdrive". Rooster. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Soul Quest Overdrive: Watch the Whole Series Here". StreetCarnage.com. 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Martin, Nick R. (19 October 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes has been using the same anti-gay slur hurled in the NYC attack for at least 15 years". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Barker, Paul (2 April 2012). "Gavin McInnes: An In-depth Interview With "The Godfather of Hipsterdom"". Thought Catalog. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Grant, Drew (27 March 2012). "Gavin McInnes Wrecks Car, 'Loses' Best Friend in An Attempt to Win Back Dignity After Observer Punking (Video)". The Observer. London, England: Observer Media. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ von Zurmwall, Nate (11 August 2013). "Day 3: Gavin McInnes' Errant Life Tips in How To Be A Man; James Ponsoldt's Advice to Filmmakers". Sundance Film Festival. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (12 August 2014). "Transphobia is Perfectly Natural". Thought Catalog. The Thought & Expression Company. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2014. 경고 페이지 맨 아래에 있는 "계속" 링크를 클릭하면 원본 기사를 볼 수 있습니다.

- ^ Monllos, Kristina (15 August 2014). "Rooster CCO Gavin McInnes Asked to Take Leave of Absence Following transphobic Thought Catalog essay, boycott". Adweek. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Brean, Joseph; Hauen, Jack; Smith, Marie-Danielle (18 August 2017). "Rebel Media meltdown: Faith Goldy fired as politicians, contributors distance themselves". National Post. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ 웰, 켈리 (2019년 1월 29일) "자랑스러운 소년들이 로저 스톤의 개인 군대가 된 방법" 2019년 1월 29일 웨이백 머신 더 데일리 비스트에서 보관.

- ^ "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Wants Neighbors to Take Down Anti-Hate Yard Signs". lawandcrime.com. 5 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Mathias, Christopher (18 October 2018). "The Proud Boys, The GOP And 'The Fascist Creep'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Staff (ndg). "Proud Boys". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "The REAL reason I left The Rebel". therebel.media. 25 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ "Get Off My Lawn Debut Episode Part 1". Crtv.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Get Off My Lawn Debut Episode Part 2". Crtv.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Mac, Ryan; Montgomery, Blake. "Twitter Suspends Proud Boys And Founder Gavin McInnes Accounts Ahead Of Unite The Right Rally". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (10 August 2018). "Twitter Shuts Down Accounts of Vice Co-Founder Gavin McInnes, Proud Boys Ahead of 'Unite the Right' Rally". Variety. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Owen, Tess (13 August 2018). "Only about 2 dozen people showed up to the Unite the Right rally in D.C." Vice. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes 'Personally I think the guy was looking to get beat up for optics'". Spectator USA. 13 October 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Feuer, Alan; Winston, Ali (19 October 2018). "Founder of Proud Boys Says He's Arranging Surrender of Men in Brawl". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

The police said the violence started after one of the leftist protesters threw a plastic bottle at the Proud Boys, who had with them members of far-right groups, like the 211 Bootboys and Batalion 49.

- ^ a b Prengel, Kate (21 November 2018). "Gavin McInnes Says He Is Quitting the Proud Boys [Video]". Heavy.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ a b 번스타인, 맥신 (2018년 12월 4일) "오리건주 FBI 국장:국은 프라우드 보이즈를 극단주의 단체로 지정하지 않았습니다." 2018년 12월 6일 웨이백 머신 더 오레곤어에서 보관.

- ^ a b 반스, 루크 (2018년 12월 7일) "FBI, 프라우드 보이즈 '극단주의자' 레이블 유턴" 웨이백 머신 씽크 프로그레스에서 2018년 12월 8일 보관

- ^ Wilson, Jason (2018년 11월 30일) "Gavin McInnes: 극우 Prud Boys의 설립자가 호주 비자를 거부했습니다 – 보고서" Wayback Machine The Guardian에서 2018년 12월 21일 보관

- ^ Doran, Matthew (30 November 2018). "Far-right campaigner Gavin McInnes denied visa on character grounds". ABC News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ 보우덴, 존 (2018년 12월 8일) "블레이즈"TV, '프라우드 보이즈' 설립자와 관계 단절 2018년 12월 9일 웨이백 머신 더 힐에서 보관

- ^ 스텔로, 팀 (2018년 12월 9일) "자랑스러운 소년들의 설립자 개빈 매키네스가 블레이즈 미디어에 나갔습니다" 2018년 12월 10일 웨이백 머신 NBC 뉴스에서 보관.

- ^ 아나폴 에이버리 (2018년 12월 10일) "유튜브, 자랑스러운 소년 설립자 개빈 맥키네스 금지" 웨이백 머신 더 힐에서 2018년 12월 10일 보관

- ^ 밀러, 헤일리 (2018년 12월 10일) "자랑스러운 소년 설립자 개빈 맥인스가 블레이즈 미디어에서 해고, 유튜브 계정 비활성화" 2018년 12월 11일 웨이백 머신 허프포스트에서 보관

- ^ 레빈, 존(2018년 12월 12일) "가빈 맥키네스는 소셜 미디어 금지 후 과거 발언을 '유감스럽게 생각한다'고 말합니다: '나는 죄책감이 없다' 2018년 12월 13일 웨이백 머신 더 랩에 보관되었습니다.

- ^ a b c d 직원 (2018년 12월 12일) "프라우드 보이즈 설립자는 폭력 선동을 부인하고, 그룹의 행동에 책임을 느끼는지에 대해 응답합니다." 웨이백 머신 ABC 뉴스에서 2018년 12월 13일 보관

- ^ a b c d * Weill, Kelly (13 November 2018). "Gavin McInnes Whines His Fellow Rich Neighbors Don't Like Him". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Rom, Gabriel (29 October 2018). "Amy Siskind warns that far-right leader Gavin McInnes lives here". The Journal News. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- Campbell, Andy (4 January 2019). "Proud Boys Founder Gavin McInnes Can Get Back To Antifa After He Battles His Neighbors". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Doughtery, Owen (4 January 2019). "Proud Boys founder asked neighbors to take down anti-hate signs: report". The Hill. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Sommer, Will (4 January 2019). "Gavin McInnes Writes Letters to Neighbors to Take Down Anti-Hate Signs". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Campbell, Andy (8 January 2019). "Gavin McInnes' Wife Threatens Neighbors Over 'Hate Has No Home Here' Signs". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Andy (15 January 2019). "Gavin McInnes Is Losing The Battle To Win Over His Neighbors". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ AP 통신 (2019년 2월 4일) "프라우드 보이즈 설립자 개빈 맥인네스, 증오 단체 레이블로 남부 빈곤 법률 센터 문제 제기" 2019년 2월 4일 웨이백 머신 NBC 뉴스에서 보관

- ^ a b c 케네디, 메리트 (2019년 2월 5일) "프라우드 보이즈 설립자, 남부 빈곤 법률 센터에 대한 명예 훼손 소송 제기" 2019년 2월 6일 웨이백 머신 NPR에서 보관

- ^ Petrizzo, Zachary (13 May 2021). "Proud Boy founder Gavin McInnes' far-right media site apparently collapsing". Salon. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (8 June 2021). "S03E118 "10 Things I Don't Get, Part 2"". Censored.TV. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Griffing, Alex (6 September 2022). "Gavin McInnes Resurfaces on Vacation After Enraging Allies By Faking Arrest". Mediaite. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Sommer, Will (31 August 2022). "Gavin McInnes Allies Believe Proud Boys Founder Faked Arrest". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Young, Matt (6 December 2022). "Gavin McInnes Interviews Kanye in New Show to Talk Rapper 'Off the Ledge'". Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via The Daily Beast.

- ^ a b Baio, Ariana (6 December 2022). "Kanye West hits new low claiming Jewish people should 'forgive Hitler today'". indy100. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (5 December 2022). "The Ye Interview". New York. New York, United States. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via Censored.TV.

- ^ 모이니한, 콜린 (2019년 8월 14일) "극우의 자랑스러운 소년들의 설립자 '헤이트몽거'" 2019년 8월 15일 웨이백 머신 더 뉴욕 타임즈에 보관.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin, Alt Light is a gay term that sounds like a diet soda in bed w Alt Right. We're "The New Right.", archived from the original on 8 March 2021, retrieved 18 March 2018

- ^ a b c Feuer, Alan (16 October 2018). "Proud Boys Founder: How He Went From Brooklyn Hipster to Far-Right Provocateur". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ *Carter, Mike (1 May 2017). "Seattle police wary of May Day violence between pro- and anti-Trump groups". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Long, Colleen (3 February 2017). "11 arrests at NYU protest over speech by 'Proud Boys' leader". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Tasker, John Paul. "Head of Canada's Indigenous veterans group hopes Proud Boys don't lose their CAF jobs". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- McInnes, Gavin; Lewis, Jeffrey (14 April 2015). "Free Speech". Daily Motion. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jason. "FBI now classifies far-right Proud Boys as 'extremist group', documents say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ a b Grigoriadis, Vanessa (28 September 2003). "The Edge of Hip: Vice, the Brand". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (14 August 2019). "Far-Right Proud Boys' Founder Called 'Hatemonger'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (16 October 2018). "Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys: Defending themselves, or spoiling for a fight?". Salon. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ "Right-wing activist heading to Australia". The Queensland Times. 21 August 2018. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ a b Campbell, Jon (15 February 2017). "Gavin McInnes Wants You to Know He's Totally Not a White Supremacist". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Swenson, Kyle (10 July 2017). "The alt-right's Proud Boys love Fred Perry polo shirts. The feeling is not mutual". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Cross, Katharine (15 February 2017). "We need to talk about Chelsea Manning". The Verge. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "New 'Fight Club' Ready for Street Violence". Southern Poverty Law Center. 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Armstrong, Liz (16 September 2004). "Shithead". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "The Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers: 2 controversial groups involved in major protests". ABC News. 19 July 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin; Winston, Ali (23 December 2018). "Far-Right Proud Boys Reeling After Arrests and Scrutiny". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Ex-Vice founder: Israelis have 'whiny paranoid fear of Nazis'". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Marcotte, Amanda (16 March 2017). "Bad boy gone worse: Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes slides from right-wing provocateur to the neo-Nazi fringe". Salon. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Csillag, Ron (17 March 2017). "Rebel's Gavin McInnes gets flak from CIJA for offensive videos about Jews and Israel". Canadian Jewish News. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b Sparks, Riley (15 March 2017). "Rebel Media is defending contributor behind 'repulsive rant' that was praised by white supremacists". Canada's National Observer. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Rosenberg, David (21 March 2017). "'10 things I hate about Jews' satirical video stirs controversy". Israel National News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (12 March 2017). "What Gavin McInnes really thinks about the Holocaust". Rebel News, YouTube. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Young, Matt (6 December 2022). "Gavin McInnes Interviews Kanye in New Show to Talk Rapper 'Off the Ledge'". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ McInnes, Gavin (5 December 2022). "The Ye Interview". New York. New York, United States. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via Censored.TV.

- ^ "Controversial Proud Boys Embrace 'Western Values,' Reject Feminism And Political Correctness". Wisconsin Public Radio. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Inside Rebel Media". National Post. 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: 'Nazis Are Not A Thing. Islam Is A Thing'". Right Wing Watch. 18 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "37 Organizations and a Regional Organization Representing Over 50 Tribes Denounce Bigotry and Violence before Patriot Prayer and Proud Boys Rally in Portland on August 4". The Skanner. 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: Feminism kills women". Rebel Media. 8 May 2017. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021.

- ^ Sutton, Scott (15 May 2015). "Gavin McInnes might be the most sexist man on the planet". National. Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^ Bonk, Lawrence (20 May 2015). "Gavin McInnes Explains 'Sexist' Comments That Ruffled Feathers...By Totally Doubling Down on Them". Independent Journal Review. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (16 March 2017). "Bad boy gone worse: Is Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes flirting with a dangerous fringe?". Salon. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Davies, Madeleine (22 October 2013). "Vice Co-Founder Throws Epic Tantrum About Women Defying Gender Roles". Jezebel. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Vice Co-Founder Gavin McInnes on Trolling Feminists: I'm Not Andy Kaufman; This Isn't a Joke". The Hollywood Reporter. 18 May 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (31 October 2013). "Most Women Work Because They Have To". Slate. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Gavin McInnes: 'Feminism has Made Women Less Happy'". ABC News. 22 October 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Buxton, Ryan (21 October 2013). "Gavin McInnes Launches Expletive-Laden Tirade About Women In The Workplace (VIDEO)". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Ciara LaVelle (24 October 2013). "UM Law Professor Mary Anne Franks Issues Epic Feminist Beatdown on Vice Founder Gavin McInnes". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ "Neo-Nazis, white nationalists, and internet trolls: who's who in the far right". The Guardian. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ *"Do You Want Bigots, Gavin? Because This Is How You Get Bigots". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "How Hate Goes 'Mainstream': Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys". Rewire.News. 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Proud Boy lawyer demands alt-weeklies not call "western chauvinist fraternity" alt-right". Baltimore City Paper. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ""Proud Boys" Founder Wants to "Trigger the Entire State of Oregon" by Helping Patriot Prayer's Joey Gibson win the Oregon Person of the Year Poll". The Portland Mercury. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "With Trump's South Africa tweet, Tucker Carlson has turned a white nationalist narrative into White House policy". Media Matters. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Jean Latz Griffin (September 1993), "NATIVE AMERICANS FIGHT CULTURE THIEVES", CHICAGO TRIBUNE

- ^ Marcotte, Amanda (17 October 2018). "Gavin McInnes and the Proud Boys: "Alt-right without the racism"?". Salon. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Fitz-Gibbon, Jorge; Rom, Gabriel (19 November 2018). "Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes and Trump critic Amy Siskind come face-to-face". The Journal News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

추가열람

- Gollner, Adam Leith (July–August 2021). "Original sins". Vanity Fair. Vol. 730. pp. 82–89, 131–133.